Abstract

Objective

To derive and validate a risk prediction algorithm to estimate hospital admission and mortality outcomes from coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19) in adults.

Design

Population based cohort study.

Setting and participants

QResearch database, comprising 1205 general practices in England with linkage to covid-19 test results, Hospital Episode Statistics, and death registry data. 6.08 million adults aged 19-100 years were included in the derivation dataset and 2.17 million in the validation dataset. The derivation and first validation cohort period was 24 January 2020 to 30 April 2020. The second temporal validation cohort covered the period 1 May 2020 to 30 June 2020.

Main outcome measures

The primary outcome was time to death from covid-19, defined as death due to confirmed or suspected covid-19 as per the death certification or death occurring in a person with confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in the period 24 January to 30 April 2020. The secondary outcome was time to hospital admission with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. Models were fitted in the derivation cohort to derive risk equations using a range of predictor variables. Performance, including measures of discrimination and calibration, was evaluated in each validation time period.

Results

4384 deaths from covid-19 occurred in the derivation cohort during follow-up and 1722 in the first validation cohort period and 621 in the second validation cohort period. The final risk algorithms included age, ethnicity, deprivation, body mass index, and a range of comorbidities. The algorithm had good calibration in the first validation cohort. For deaths from covid-19 in men, it explained 73.1% (95% confidence interval 71.9% to 74.3%) of the variation in time to death (R2); the D statistic was 3.37 (95% confidence interval 3.27 to 3.47), and Harrell’s C was 0.928 (0.919 to 0.938). Similar results were obtained for women, for both outcomes, and in both time periods. In the top 5% of patients with the highest predicted risks of death, the sensitivity for identifying deaths within 97 days was 75.7%. People in the top 20% of predicted risk of death accounted for 94% of all deaths from covid-19.

Conclusion

The QCOVID population based risk algorithm performed well, showing very high levels of discrimination for deaths and hospital admissions due to covid-19. The absolute risks presented, however, will change over time in line with the prevailing SARS-C0V-2 infection rate and the extent of social distancing measures in place, so they should be interpreted with caution. The model can be recalibrated for different time periods, however, and has the potential to be dynamically updated as the pandemic evolves.

Introduction

The first cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection were reported in the UK on 24 January 2020, with the first death from coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19) on 28 February 2020. As of 18 August 2020, more than 41 000 deaths from covid-19 had occurred in the UK and more than 773 000 deaths globally.1 In the initial absence of any vaccination or prophylactic or curative treatments, the UK government implemented social distancing and shielding measures to suppress the rate of infection and protect vulnerable people, thereby trying to minimise the risk of serious adverse outcomes.2 3

Emerging evidence throughout the course of the pandemic, initially from case series and then from cohorts of patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, has shown associations of age, sex, certain comorbidities, ethnicity, and obesity with adverse covid-19 outcomes such as hospital admission or death.4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 The knowledge base regarding risk factors for severe covid-19 is growing. As many countries are cautiously attempting to ease “lockdown” measures or reintroduce measures if rates are rising, an opportunity exists to develop more nuanced guidance based on predictive algorithms to inform risk management decisions.12 Better knowledge of individuals’ risks could also help to guide decisions on mitigating occupational exposure and in targeting of vaccines to those most at risk. Although some prediction models have been developed, a recent systematic review found that they all have a high risk of bias and that their reported performance is optimistic.13

The use of primary care datasets with linkage to registries such as death records, hospital admissions data, and covid-19 testing results represents a novel approach to clinical risk prediction modelling for covid-19. It provides accurately coded, individual level data for very large numbers of people representative of the national population. This approach draws on the rich phenotyping of individuals with demographic, medical, and pharmacological predictors to allow robust statistical modelling and evaluation. Such linked datasets have an established track record for the development and evaluation of established clinical risk models, including those for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and mortality.14 15 16 We aimed to develop and validate population based prediction models to estimate the risks of becoming infected with and subsequently dying from covid-19 and of becoming infected and subsequently admitted to hospital with covid-19. The model we have developed is designed to be applied across the adult population so that it can be used to enable risk stratification for public health purposes in the event of a “second wave” of the pandemic, to support shared management of risk and occupational exposure, and in early targeting of vaccines to people most at risk. An ongoing companion study will externally validate the models, using datasets across all four nations of the UK, and will be reported separately.

Methods

This study was commissioned by the Chief Medical Officer for England on behalf of the UK Government, who asked the New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group (NERVTAG) to establish whether a clinical risk prediction model for covid-19 could be developed in line with the emerging evidence. The protocol has been published.17 The study was conducted in adherence with TRIPOD18 and RECORD19 guidelines and with input from our patient advisory group.

Study design and data sources

We did a cohort study of primary care patients using the QResearch database (version 44). QResearch was established in 2002 and has been extensively used for the development of risk prediction algorithms across the National Health Service (NHS) and for epidemiological research. By April 2020, 1205 practices in England were contributing to QResearch, covering a population of 10.5 million patients. The database is linked at individual patient level, using a project specific pseudonymised NHS number, to hospital admissions data (including intensive care unit data), positive results from covid-19 real time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction tests held by Public Health England, cancer registrations (including detailed radiotherapy and systemic chemotherapy records), the national covid-19 shielded patient list in England, and mortality records held by NHS Digital.

We identified a cohort of people aged 19-100 years registered with participating general practices in England on 24 January 2020. We excluded patients (approximately 0.1%) who did not have a valid NHS number. Patients entered the cohort on 24 January 2020 (date of first confirmed case of covid-19 in the UK) and were followed up until they had the outcome of interest or the end of the first study period (30 April 2020), which was the date up to which linked data were available at the time of the derivation of the model, or the second time period (1 May 2020 until 30 June 2020) for the temporal cohort validation.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was time to death from covid-19 (either in hospital or outside hospital), defined as confirmed or suspected death from covid-19 as per the death certification or death occurring in an individual with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection at any time in the period 24 January to 30 April 2020. The secondary outcome was time to hospital admission with covid-19, defined as an ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision) code for either confirmed or suspected covid-19 or new hospital admission associated with a confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in the study period.

Predictor variables

We selected candidate predictor variables on the basis of the presence of existing clinical vulnerability group criteria (table 1), associations with outcomes in other respiratory diseases, or hypothesised to be linked to adverse outcomes on clinical/biological plausibility and likely to be available for implementation. They are summarised in box 1 and supplementary box A. We defined variables according to information recorded using Read Codes in general practices’ electronic health records at the start of the study period. The exception to this was information on chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and transplants, which was based on linked hospital records.

Table 1.

Original population level risk stratification method as exercised in UK*

| Clinical risk level | Advice | Criteria | Identification and inclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinically extremely vulnerable (high risk) | Shielding (stay at home and stringently avoid any personal/face-to-face contact) | High risk conditions as established by clinical expert group decisions based on available evidence at time. Dynamic group of approximately 2.2 million people in England | Method 1: core group of patients identified by NHS Digital and contacted centrally by NHS England |

| Method 2: additional patients in particular medical sub-specialties not identifiable centrally | |||

| Method 3: additional patients identified by secondary care specialists using clinical judgment | |||

| Method 4: additional patients identified in primary care using clinical judgment | |||

| Clinically vulnerable (medium risk) | Follow stringent social distancing measures | Vulnerable group of approximately 16 million people in England, based on eligibility for influenza vaccination due to age ≥70, pregnancy, or comorbidity | NA |

| Remainder of population (low risk) | Follow mandatory social distancing measures and “lockdown” measures, but no specific clinical advice | NA | NA |

NA=not applicable.

Shielding and stringent social distancing are both interventions designed to reduce risk of exposure to SARS-CoV-2, but classification of risk relates to risk of complicated or fatal disease if infected and not risk of becoming infected.

Box 1. Candidate predictor variables examined during model development*.

Demographic

Age in years (continuous)

Townsend deprivation score (continuous)—This is an area level continuous score based on the patient’s postcode.20 Originally developed by Townsend,20 it includes unemployment (as a percentage of those aged ≥16 who are economically active), non-car ownership (as a percentage of all households), non-home ownership (as a percentage of all households), and household overcrowding. These variables are measured for a given area of approximately 120 households, via the 2011 census, and combined to give a Townsend score for that area. A greater Townsend score implies a greater level of deprivation

Ethnicity in nine categories (White, Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Other Asian, Caribbean, Black African, Chinese, other ethnic group)

Domicile in three categories: homeless, care home residence (nursing or residential), other

Lifestyle

Smoking status in five categories (non-smoker, ex-smoker, 1-10 per day, 11-19 per day, ≥20 per day)

Body mass index in kg/m2 (continuous)

Crack cocaine and injected drug use

Conditions on current shielding patient list

Solid organ transplant recipient on long term immune suppression treatment

-

Cancers:

Active chemotherapy

Radical radiotherapy for lung cancer

Blood/bone marrow cancer at any treatment stage

Immunotherapy or continuing antibody treatment

Targeted cancer treatments that affect immune system (PARP inhibitor or PKI)

Bone marrow or stem cell transplant in previous 6 months or remain on immunosuppression

Immunosuppression sufficiently increasing infection risk

-

Severe respiratory disease:

Severe asthma (≥3 prescribed courses of steroids in preceding 12 months)

Severe COPD (≥3 prescribed courses of steroids in preceding 12 months)

Cystic fibrosis, interstitial lung disease, sarcoidosis, non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis, or pulmonary hypertension

-

Rare diseases or inborn errors of metabolism:

Severe combined immunodeficiency

Homozygous sickle cell disease

-

Pregnant with significant heart disease:

Acquired or congenital

Conditions moderately associated with increased risk of complications as per current NHS guidance

-

Chronic, non-severe respiratory disease:

Asthma

COPD (emphysema and chronic bronchitis)

Extrinsic allergic alveolitis

-

Chronic kidney disease (CKD):

CKD stage 3 or 4

End stage renal failure requiring dialysis

End stage renal failure ever undergoing a transplant

-

Cardiac disease:

Congestive cardiac failure

Valvular heart disease

-

Chronic liver disease:

Chronic infective hepatitis (hepatitis B or C)

Alcohol related liver disease

Primary biliary cirrhosis

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

Haemochromatosis

-

Chronic neurological conditions:

Epilepsy

Parkinson’s disease

Motor neurone disease

Cerebral palsy

Dementia (Alzheimer’s, vascular, frontotemporal)

Down’s syndrome

-

Diabetes mellitus:

Type 1

Type 2

-

Conditions or treatments that predispose to infection (eg, steroid treatment):

Rheumatoid arthritis

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Ankylosing spondylitis or other inflammatory arthropathy (eg, psoriatic arthritis)

Connective tissue disease (eg, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, scleroderma, Sjögren’s syndrome)

Polymyositis or dermatomyositis

Vasculitis (eg, giant cell arteritis, polyarteritis nodosa, Behçet’s syndrome)

Other medical conditions that investigators hypothesised to confer elevated risk

-

Cardiovascular disease:

Atrial fibrillation

Cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke, angina, transient ischaemic attack)

Peripheral vascular disease

Treated hypertension

Hyperthyroidism

Chronic pancreatitis

Cirrhosis (if not above; eg, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease)

-

Malabsorption:

Coeliac disease

Steatorrhoea

Blind loop syndrome

Peptic ulcer (gastric or duodenal)

Learning disability

Osteoporosis

Fragility fracture (hip, spine, shoulder, or wrist fracture)

-

Severe mental illness:

Bipolar affective disorder

Psychosis

Schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder

Severe depression

HIV infection

Hyposplenism

Sickle cell disease

Sphingolipidoses (eg, Tay-Sachs disease)

History of venous thromboembolism

Tuberculosis

Concurrent medications

Drugs affecting the immune response, including systemic chemotherapy based on hospital data

Drugs affecting the immune system prescribed in primary care (focus on BNF chapter 8.2)

Long acting β agonists

Long acting muscarinic antagonists

Inhaled corticosteroids

COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PARP=poly ADP ribose polymerase; PKI=protein kinase A inhibitor.

*Based on data recorded in general practice record linked to hospital information on chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and transplants

QCOVID model development

We randomly allocated 75% of practices to the derivation dataset, which we used to develop the models. We evaluated the models’ performance in the remaining 25% of practices (the validation set). All models were fitted separately in men and women. The outcomes of interest are subject to competing risks. For the primary outcome of death from covid-19, the competing risk is death due to other causes. For the secondary outcome of hospital admission, the competing risk is death from any cause before admission. We fitted a sub-distribution hazard (Fine and Gray21) model for each outcome to account for competing risks. Individuals who did not have the outcome of interest were censored at the study end date, including those who had a competing event.

For all predictor variables, we used the most recently available value at the entry date (24 January 2020). We used second degree fractional polynomials to model non-linear relations for continuous variables (age, body mass index, and Townsend material deprivation score, an area level score based on postcode20). Initially, we fitted a complete case analysis by using a model within the derivation data to derive the fractional polynomial terms. For indicators of comorbidities and medication use, we assumed the absence of recorded information to mean absence of the factor in question. Data were missing in four variables: ethnicity, Townsend score, body mass index, and smoking status. We used multiple imputation with chained equations under the missing at random assumption to replace missing values for these variables. For computational efficiency, we used a combined imputation model for both outcomes. The imputation model was fitted in the derivation data and included predictor variables, the Nelson-Aalen estimators of the baseline cumulative sub-distribution hazard, and the outcome indicators (death from covid-19 and hospital admission with covid-19). We carried out five imputations. Each analysis model was fitted in each of the five imputed datasets. We used Rubin’s rules to combine the model parameter estimates and the baseline cumulative incidence estimates across the imputed datasets.

We initially sought to fit models using all predictor variables. Owing to sparse cells, some conditions were combined if clinically similar in nature (such as rare neurological disorders). We examined interactions between body mass index and ethnicity and interactions between predictor variables and age, focusing on predictor variables that apply across the age range (asthma, epilepsy, diabetes, severe mental illness). We explored the use of penalised models (LASSO) to screen variables for inclusion, but this retained all the predictor variables and most interaction terms.17 In line with the protocol, we subsequently removed a small number of variables with low numbers of events and adjusted (sub-distribution) hazard ratios close to 1 (as these will have minimal effect on predicted risks) or with uncertain clinical credibility, defined as counterintuitive results in light of the emerging literature. Lastly, we combined regression coefficients from the final models with estimates of the baseline cumulative incidence function evaluated at 97 days to derive risk equations for each outcome. We used all the available data in the database.

Model evaluation

We did all model evaluation using the validation data with two separate periods of follow-up. The first validation study period was the same as for the derivation cohort: 24 January to 30 April 2020. The second temporal validation covered the subsequent period of 1 May 2020 to 30 June 2020. This was carried out with the same validation cohort except for exclusion of patients who died during 24 January to 30 April 2020. In the validation cohort, we fitted an imputation model to replace missing values for ethnicity, body mass index, Townsend score, and smoking status. This excluded the outcome indicators and Nelson-Aalen terms, as the aim was to use covariate data to obtain a prediction as if the outcome had not been observed to reflect intended use.

We applied the final risk equations developed from the derivation dataset to men and women in the validation dataset and evaluated R2 values, Brier scores, and measures of discrimination and calibration for the two time periods.22 23 24 R2 values refer to the proportion of variation in survival time explained by the model. Brier scores measure predictive accuracy, where lower values indicate better accuracy.25 D statistics (a discrimination measure that quantifies the separation in survival between patients with different levels of predicted risks) and Harrell’s C statistics (a discrimination metric that quantifies the extent to which people with higher risk scores have earlier events) were evaluated at 97 days (the maximum follow-up period available at the time of the derivation of the model) and 60 days for the second temporal validation, with corresponding 95% confidence intervals.26 We assessed model calibration by comparing mean predicted risks with observed risks by twentieths of predicted risk for each of the validation cohorts. Observed risks were derived in each of the 20 groups by using non-parametric estimates of the cumulative incidences. Additionally, we did a recalibration for the mortality outcome, using the method proposed by Booth et al by updating the baseline survivor function based on the temporal validation cohort with the prognostic index as an offset term.27 We also applied the algorithms to the validation cohort for the first time period to define the centile thresholds based on absolute risk. We also defined centiles of relative risk (defined as the ratio of the individual’s predicted absolute risk to the predicted absolute risk for a person of the same age and sex with a white ethnicity, body mass index of 25, and mean deprivation score with no other risk factors).

We calculated the performance metrics in the whole validation cohort and in the following pre-specified subgroups: within age groups (19-39, 40-49, 50-59, 60-69, 70-79, ≥80 years), within nine ethnic groups, and within each of the 10 English regions (where numbers allowed). In response to open peer review of the published protocol,17 we evaluated performance by calculating Harrell’s C statistics in individual general practices and combining the results using a random effects meta-analysis.28

Patient and public involvement

Patients were involved in setting the research question and in developing plans for design and implementation of the study. Patients were asked to aid in interpreting and disseminating the results.

Results

Overall study population

Overall, 1205 practices in England met our inclusion criteria. Of these, 910 practices were randomly assigned to the derivation dataset and 295 to the validation cohort. The practices had 8 256 158 registered patients aged 19-100 years on 24 January 2020. We included 6 083 102 of these in the derivation cohort, and the validation dataset comprised 2 173 056 people.

Baseline characteristics

Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of patients in the derivation cohort. Of these patients, 3 035 409 (49.9%) were men and 990 799 (16.3%) were of black, Asian, or other minority ethnic (BAME) background.

Table 2.

Demographic and medical characteristics of derivation cohort and cohort members with outcomes. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristic | Derivation cohort—total (n=6 083 102) | Derivation cohort—covid-19 deaths (n=4384) | Derivation cohort—covid-19 admission (n=10 776) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 3 035 409 (49.90) | 2517 (57.41) | 5962 (55.33) |

| Mean (SD) age, years | 48.21 (18.57) | 80.27 (12.10) | 69.63 (17.91) |

| Age band: | |||

| 19-29 years | 1 139 120 (18.73) | 12 (0.27) | 282 (2.62) |

| 30-39 years | 1 190 905 (19.58) | 22 (0.50) | 523 (4.85) |

| 40-49 years | 1 021 643 (16.79) | 51 (1.16) | 828 (7.68) |

| 50-59 years | 1 013 599 (16.66) | 223 (5.09) | 1371 (12.72) |

| 60-69 years | 757 483 (12.45) | 460 (10.49) | 1677 (15.56) |

| 70-79 years | 586 164 (9.64) | 892 (20.35) | 2135 (19.81) |

| 80-89 years | 298 093 (4.90) | 1722 (39.28) | 2722 (25.26) |

| ≥90 years | 76 095 (1.25) | 1002 (22.86) | 1238 (11.49) |

| Geographical region: | |||

| East Midlands | 164 502 (2.70) | 52 (1.19) | 131 (1.22) |

| East of England | 186 673 (3.07) | 136 (3.10) | 317 (2.94) |

| London | 1 576 616 (25.92) | 1287 (29.36) | 3799 (35.25) |

| North East | 163 388 (2.69) | 87 (1.98) | 243 (2.26) |

| North West | 1 076 590 (17.70) | 942 (21.49) | 2055 (19.07) |

| South Central | 824 558 (13.55) | 563 (12.84) | 1293 (12.00) |

| South East | 685 960 (11.28) | 462 (10.54) | 960 (8.91) |

| South West | 581 014 (9.55) | 198 (4.52) | 501 (4.65) |

| West Midlands | 605 752 (9.96) | 533 (12.16) | 1197 (11.11) |

| Yorkshire and Humber | 218 049 (3.58) | 124 (2.83) | 280 (2.60) |

| Ethnicity: | |||

| White | 3 924 110 (64.51) | 2947 (67.22) | 6790 (63.01) |

| Indian | 175 909 (2.89) | 131 (2.99) | 423 (3.93) |

| Pakistani | 114 727 (1.89) | 69 (1.57) | 248 (2.30) |

| Bangladeshi | 87 491 (1.44) | 69 (1.57) | 173 (1.61) |

| Other Asian | 110 579 (1.82) | 57 (1.30) | 248 (2.30) |

| Caribbean | 69 166 (1.14) | 152 (3.47) | 392 (3.64) |

| Black African | 150 022 (2.47) | 122 (2.78) | 456 (4.23) |

| Chinese | 58 511 (0.96) | 18 (0.41) | 45 (0.42) |

| Other ethnic group | 224 394 (3.69) | 114 (2.60) | 436 (4.05) |

| Not recorded | 1 168 193 (19.20) | 705 (16.08) | 1565 (14.52) |

| Townsend deprivation fifth: | |||

| 1 (most affluent) | 1 238 575 (20.36) | 840 (19.16) | 1799 (16.69) |

| 2 | 1 222 681 (20.10) | 746 (17.02) | 1886 (17.50) |

| 3 | 1 187 082 (19.51) | 934 (21.30) | 2114 (19.62) |

| 4 | 1 176 829 (19.35) | 951 (21.69) | 2338 (21.70) |

| 5 (most deprived) | 1 23 1431 (20.24) | 905 (20.64) | 2612 (24.24) |

| Not recorded | 26 504 (0.44) | * | 27 (0.25) |

| Accommodation: | |||

| Neither homeless nor care home resident | 6 036 288 (99.23) | 3345 (76.30) | 9895 (91.82) |

| Care home or nursing home resident | 35 813 (0.59) | 1033 (23.56) | 854 (7.93) |

| Homeless | 11 001 (0.18) | * | 27 (0.25) |

| Body mass index: | |||

| <18.5 | 161 579 (2.66) | 203 (4.63) | 260 (2.41) |

| 18.5-24.99 | 2 033 809 (33.43) | 1345 (30.68) | 2708 (25.13) |

| 25-29.99 | 1 723 494 (28.33) | 1291 (29.45) | 3406 (31.61) |

| 30-34.99 | 800 857 (13.17) | 738 (16.83) | 2126 (19.73) |

| ≥35 | 453 323 (7.45) | 460 (10.49) | 1549 (14.37) |

| Not recorded | 910 040 (14.96) | 347 (7.92) | 727 (6.75) |

| Smoking status: | |||

| Non-smoker | 3 482 456 (57.25) | 2312 (52.74) | 6073 (56.36) |

| Ex-smoker | 1 291 953 (21.24) | 1735 (39.58) | 3716 (34.48) |

| Light smoker | 803 783 (13.21) | 199 (4.54) | 668 (6.20) |

| Moderate smoker | 153 680 (2.53) | 32 (0.73) | 97 (0.90) |

| Heavy smoker | 70 215 (1.15) | 18 (0.41) | 62 (0.58) |

| Not recorded | 281 015 (4.62) | 88 (2.01) | 160 (1.48) |

| Chronic kidney disease (CKD): | |||

| No CKD | 5 843 919 (96.07) | 2928 (66.79) | 8156 (75.69) |

| CKD3 | 2 14193 (3.52) | 1190 (27.14) | 2010 (18.65) |

| CKD4 | 12 654 (0.21) | 141 (3.22) | 252 (2.34) |

| CKD5 only | 7286 (0.12) | 96 (2.19) | 239 (2.22) |

| CKD5 with dialysis | 1676 (0.03) | 14 (0.32) | 46 (0.43) |

| CKD5 with transplant | 3374 (0.06) | 15 (0.34) | 73 (0.68) |

| Learning disability: | |||

| No learning disability | 5 972 982 (98.19) | 4110 (93.75) | 10251 (95.13) |

| Learning disability | 107107 (1.76) | 255 (5.82) | 498 (4.62) |

| Down’s syndrome | 3013 (0.05) | 19 (0.43) | 27 (0.25) |

| Chemotherapy: | |||

| No chemotherapy in previous 12 months | 6 059 236 (99.61) | 4267 (97.33) | 10482 (97.27) |

| Chemotherapy group A | 9307 (0.15) | 33 (0.75) | 71 (0.66) |

| Chemotherapy group B | 13 600 (0.22) | 75 (1.71) | 200 (1.86) |

| Chemotherapy group C | 959 (0.02) | * | 23 (0.21) |

| Cancer and immunosuppression: | |||

| Blood cancer | 28 089 (0.46) | 114 (2.60) | 238 (2.21) |

| Bone marrow or stem cell transplant in previous 6 months | 194 (0.00) | * | * |

| Respiratory cancer | 12 792 (0.21) | 61 (1.39) | 130 (1.21) |

| Radiotherapy in previous 6 months | 12 129 (0.20) | 56 (1.28) | 125 (1.16) |

| Solid organ transplant | 3209 (0.05) | 10 (0.23) | 33 (0.31) |

| GP prescribed immunosuppressant medication | 7990 (0.13) | 19 (0.43) | 53 (0.49) |

| Prescribed leukotriene or LABA | 13 0895 (2.15) | 399 (9.10) | 874 (8.11) |

| Prescribed regular prednisolone | 32 929 (0.54) | 176 (4.01) | 388 (3.60) |

| Sickle cell disease | 2125 (0.03) | * | 28 (0.26) |

| Other comorbidities: | |||

| Type 1 diabetes | 28 587 (0.47) | 36 (0.82) | 136 (1.26) |

| Type 2 diabetes | 394 562 (6.49) | 1417 (32.32) | 3017 (28.00) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 142 107 (2.34) | 580 (13.23) | 1155 (10.72) |

| Asthma | 825 422 (13.57) | 584 (13.32) | 1745 (16.19) |

| Rare pulmonary diseases | 33 433 (0.55) | 96 (2.19) | 240 (2.23) |

| Pulmonary hypertension or pulmonary fibrosis | 4940 (0.08) | 40 (0.91) | 83 (0.77) |

| Coronary heart disease | 215 069 (3.54) | 1038 (23.68) | 1779 (16.51) |

| Stroke | 129 699 (2.13) | 809 (18.45) | 1339 (12.43) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 147 528 (2.43) | 832 (18.98) | 1461 (13.56) |

| Congestive cardiac failure | 70 970 (1.17) | 575 (13.12) | 1005 (9.33) |

| Venous thromboembolism | 105 136 (1.73) | 381 (8.69) | 753 (6.99) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 44 476 (0.73) | 289 (6.59) | 467 (4.33) |

| Congenital heart disease | 31 576 (0.52) | 48 (1.09) | 100 (0.93) |

| Dementia | 58 873 (0.97) | 1311 (29.90) | 1235 (11.46) |

| Parkinson’s disease | 15 315 (0.25) | 137 (3.13) | 218 (2.02) |

| Epilepsy | 80 064 (1.32) | 159 (3.63) | 348 (3.23) |

| Rare neurological conditions | 18 603 (0.31) | 42 (0.96) | 120 (1.11) |

| Cerebral palsy | 6481 (0.11) | * | 27 (0.25) |

| Severe mental illness | 672 494 (11.06) | 745 (16.99) | 1841 (17.08) |

| Osteoporotic fracture | 238 276 (3.92) | 675 (15.40) | 1154 (10.71) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis or SLE | 60 847 (1.00) | 127 (2.90) | 309 (2.87) |

| Cirrhosis of liver | 11 865 (0.20) | 37 (0.84) | 106 (0.98) |

GP=general practitioner; LABA=long acting β agonist; SLE=systemic lupus erythematosus.

Value suppressed owing to small numbers (<15).

In the derivation cohort, 10 776 (0.18%) patients had a covid-19 related hospital admission and 4384 (0.07%) had a covid-19 related death during the 97 days’ follow-up, of which 4265 (97.3%) were recorded on the death certificate and 119 (2.71%) were based only on a positive test (and of these <15 were based on a test more than 28 days before death). Admissions and deaths due to covid-19 occurred across all regions, with the greatest numbers in London, which accounted for 3799 (35.3%) of admissions and 1287 (29.4%) of deaths. Of those who died, 2517 (57.4%) were male, 732 (16.7%) were BAME, 3616 (82.5%) were aged 70 and over, 1417 (32.3%) had type 2 diabetes, 1311 (29.9%) had dementia, and 1033 (23.6%) were identified as living in a care home.

The characteristics of the validation cohort were similar to those of the derivation cohort, as shown in supplementary tables A and B. In the first validation period (24 January to 30 April 2020), 1722 deaths and 3703 hospital admissions due to covid-19 occurred. In the second validation period (1 May to 30 June 2020), 621 deaths and 1002 admissions due to covid-19 occurred.

Predictor variables

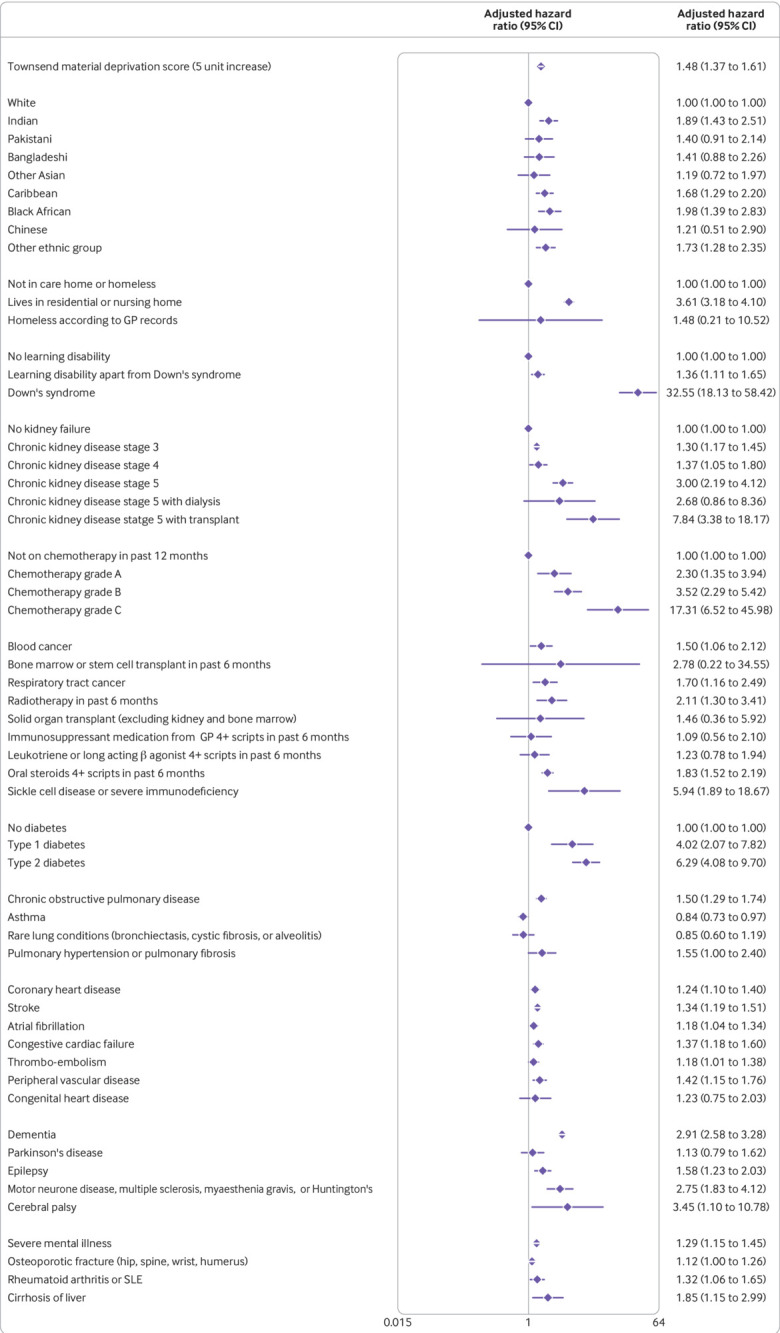

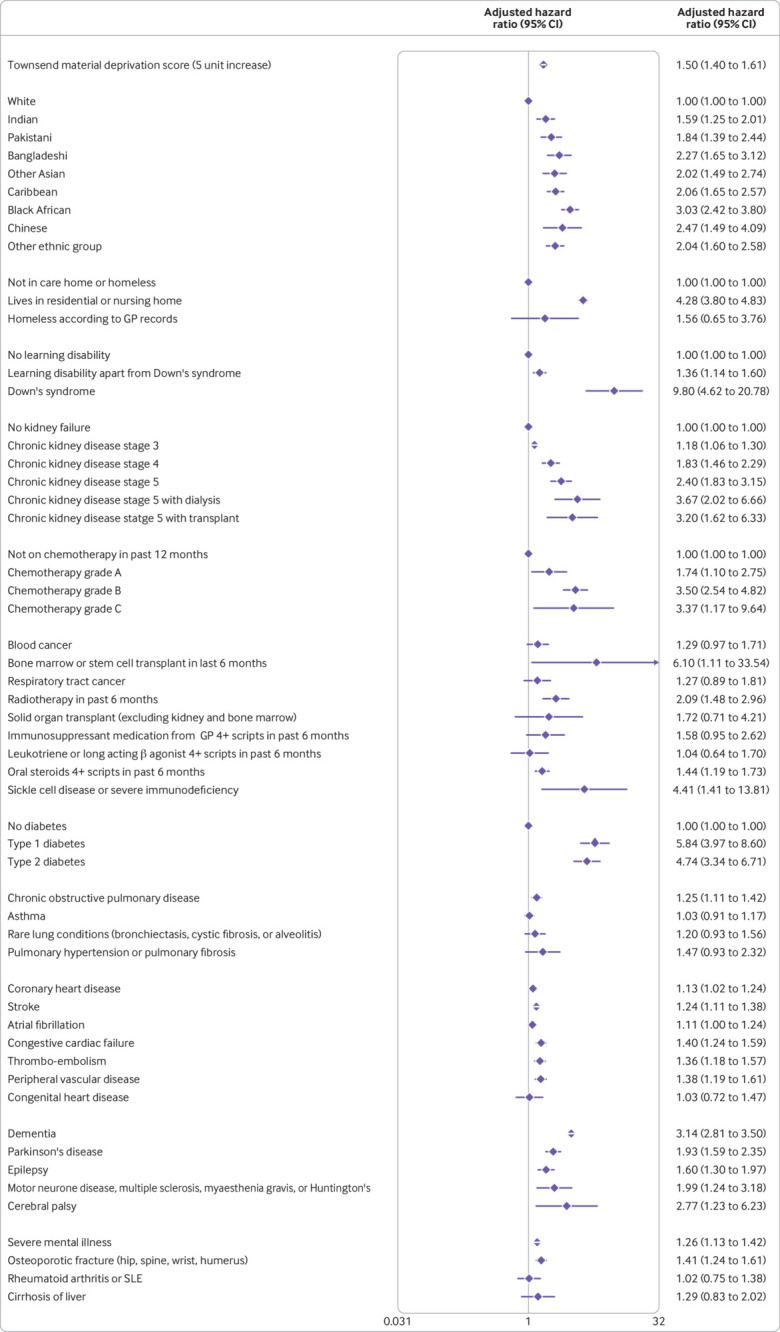

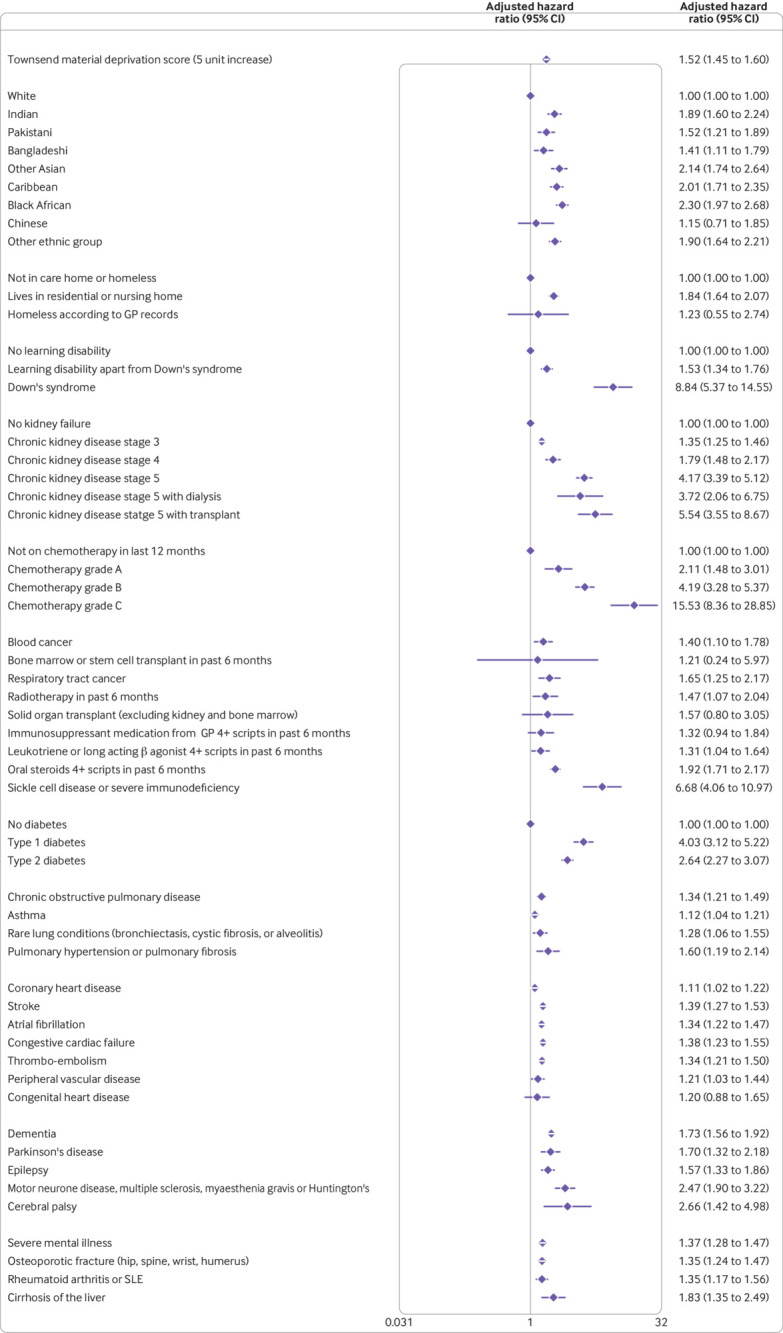

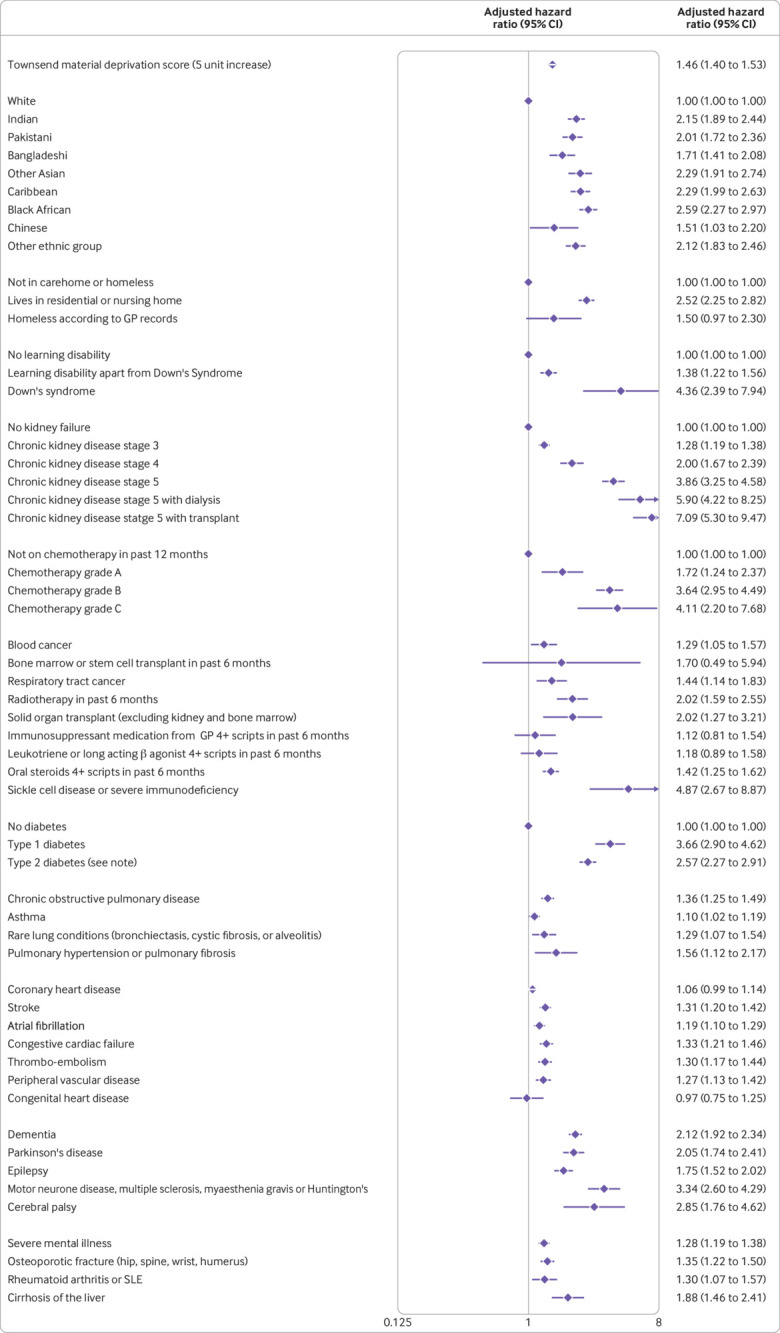

The variables included in the final models were fractional polynomial terms for age and body mass index, Townsend score (linear), ethnic group, domicile (residential care, homeless, neither), and a range of conditions and treatments as shown in figure 1, figure 2, figure 3, and figure 4. These conditions and treatments were cardiovascular conditions (atrial fibrillation, heart failure, stroke, peripheral vascular disease, coronary heart disease, congenital heart disease), diabetes (type 1 and type 2 and interaction terms for type 2 diabetes with age), respiratory conditions (asthma, rare respiratory conditions (cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis, or alveolitis), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary hypertension or pulmonary fibrosis), cancer (blood cancer, chemotherapy, lung or oral cancer, marrow transplant, radiotherapy), neurological conditions (cerebral palsy, Parkinson’s disease, rare neurological conditions (motor neurone disease, multiple sclerosis, myasthenia, Huntington’s chorea), epilepsy, dementia, learning disability, severe mental illness), other conditions (liver cirrhosis, osteoporotic fracture, rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus, sickle cell disease, venous thromboembolism, solid organ transplant, renal failure (CKD3, CKD4, CKD5, with or without dialysis or transplant)), and medications (≥4 prescriptions from general practitioner in previous six months for oral steroids, long acting β agonists or leukotrienes, immunosuppressants).

Fig 1.

Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) of death from covid-19 in women in derivation cohort, adjusted for variables shown, deprivation, and fractional polynomial terms for body mass index (BMI) and age. Model includes fractional polynomial terms for age (3 3) and BMI (0.5 0.5 ln(bmi)) and interaction terms between age terms and type 2 diabetes. Hazard ratio for type 2 diabetes reported at mean age. GP=general practitioner; SLE=systemic lupus erythematosus. (QResearch database version 44; study period 24 January 2020 to 30 April 2020)

Fig 2.

Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) of death from covid-19 in men in derivation cohort, adjusted for variables shown, deprivation, and fractional polynomial terms for body mass index (BMI) and age. Model includes fractional polynomial terms for age (1 3) and BMI (−0.5 −0.5 ln(age)) and interaction terms between age terms and type 2 diabetes. Hazard ratio for type 2 diabetes reported at mean age. GP=general practitioner; SLE=systemic lupus erythematosus. (QResearch database version 44; study period 24 January 2020 to 30 April 2020)

Fig 3.

Adjusted hazard ratio (95%CI) of hospital admission for covid-19 in women in derivation cohort, adjusted for variables shown, deprivation, fractional polynomial terms for body mass index (BMI) and age. Model includes fractional polynomial terms for age (0.5, 2) and BMI (−2 0) and interaction terms between age terms and type 2 diabetes. Hazard ratio for type 2 diabetes reported at mean age. GP=general practitioner; SLE=systemic lupus erythematosus. (QResearch database version 44; study period 24 January 2020 to 30 April 2020)

Fig 4.

Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) of hospital admission for covid-19 in men in derivation cohort, adjusted for variables shown, deprivation, and fractional polynomial terms for body mass index (BMI) and age. Model includes fractional polynomial terms for age (−2 2) and BMI (−0.5 0) and interaction terms between age terms and type 2 diabetes. Hazard ratio for type 2 diabetes reported at mean age. GP=general practitioner; SLE=systemic lupus erythematosus. (QResearch database version 44; study period 24 January 2020 to 30 April 2020)

Figure 1 and figure 2 show the adjusted hazard ratios in the final models for covid-19 related death in the derivation cohort in women and men. Figure 3 and figure 4 show the adjusted hazard ratios for the final models for covid-19 related hospital admission in the derivation cohort.

Supplementary figures A and B show graphs of the adjusted hazard ratios for body mass index, age, and the interaction between age and type 2 diabetes for deaths and hospital admissions due to covid-19 (which showed higher risks associated with younger ages). Supplementary figures C and D show fully adjusted hazard ratios for variables for the full model, including variables that were not retained in the final model (for example, adjusted hazard ratios close to one or those which lacked clinical credibility). Other variables with too few events for inclusion were HIV, sphingolipidoises, short bowel syndrome, polymyositis, dermatomyositis, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, biliary cirrhosis, hepatitis B and C, haemochromatosis, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, chronic pancreatitis, drug misuse, asplenia, cholangitis, scleroderma, Sjogren’s syndrome, and pregnancy. Supplementary figures E and F show fully adjusted hazard ratios for a combined outcome of either covid-19 related death or hospital admission. This gave very similar absolute risks to the hospital admission outcome.

Model evaluation

Discrimination

Table 3 shows the performance of the risk equations in the validation cohort for women and men over 97 days for the main study period and for the temporal validation cohort evaluated from 1 May 2020 to 30 June 2020. Overall, the values for the R2, D, and C statistics were similar in women and men. Values for the mortality outcome tended to be higher than those for the hospital admission outcome. For example, in the first validation period, the equation explained 74% of the variation in time to death from covid-19 in women; the D statistic was 3.46, and Harrell’s C statistic was 0.933. The corresponding values in men were 73.1%, 3.37, and 0.928. The results for the second validation period were similar except for covid-19 related admissions in women, for which the explained variation and discrimination were lower than for the first period (explained variation 45.4%, D statistic 1.87, and Harrell’s C statistic 0.776).

Table 3.

Performance of risk models to predict risk of death and hospital admission due to covid-19 in validation cohort in first validation period (24 January to 30 April 2020) and second temporal validation (1 May to 30 June 2020). Values are estimates (95% CIs) unless stated otherwise

| Covid-19 death | Covid-19 admission | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | ||

| Period 1 | |||||

| R2 statistic (%) | 74.0 (72.7 to 75.3) | 73.1 (71.9 to 74.3) | 57.1 (55.5 to 58.8) | 58.1 (56.7 to 59.5) | |

| D statistic | 3.46 (3.34 to 3.57) | 3.37 (3.27 to 3.47) | 2.36 (2.28 to 2.44) | 2.41 (2.34 to 2.48) | |

| Harrell’s C | 0.933 (0.923 to 0.944) | 0.928 (0.919 to 0.938) | 0.847 (0.836 to 0.857) | 0.860 (0.852 to 0.868) | |

| Brier score | 0.0007 | 0.0009 | 0.0015 | 0.0019 | |

| Period 2 | |||||

| R2 statistic (%) | 75.4 (73.5 to 77.4) | 73.6 (71.6 to 75.6) | 45.4 (41.7 to 49.1) | 55.4 (52.2 to 58.5) | |

| D statistic | 3.59 (3.4 to 3.77) | 3.42 (3.24 to 3.59) | 1.87 (1.73 to 2) | 2.28 (2.14 to 2.42) | |

| Harrell’s C | 0.952 (0.938 to 0.965) | 0.933 (0.918 to 0.949) | 0.776 (0.753 to 0.800) | 0.833 (0.812 to 0.853) | |

| Brier score | 0.0002 | 0.0003 | 0.0004 | 0.0004 | |

Supplementary tables C-F show the corresponding results by region, age band, and fifth of deprivation and within each ethnic group in men and women in both validation periods. Performance was generally similar to the overall results except for age, for which the values were lower within individual age bands.

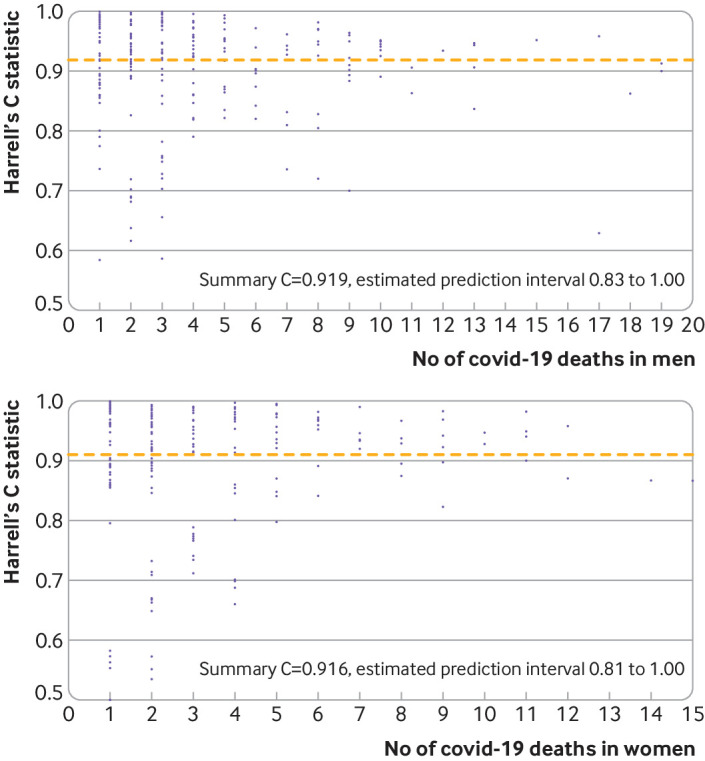

Figure 5 shows funnel plots of Harrell’s C statistic for each general practice in the validation cohort versus the number of deaths in each practice in men and women in the first validation period. The summary (average) C statistic for women was 0.916 (95% confidence interval 0.908 to 0.924) from a random effects meta-analysis. The corresponding summary C statistic for men was 0.919 (0.912 to 0.926).

Fig 5.

Funnel plots of discrimination using Harrell’s C statistic for each general practice in validation cohort versus number of deaths in each practice in men (top panel) and women (bottom panel) in first validation period

Calibration

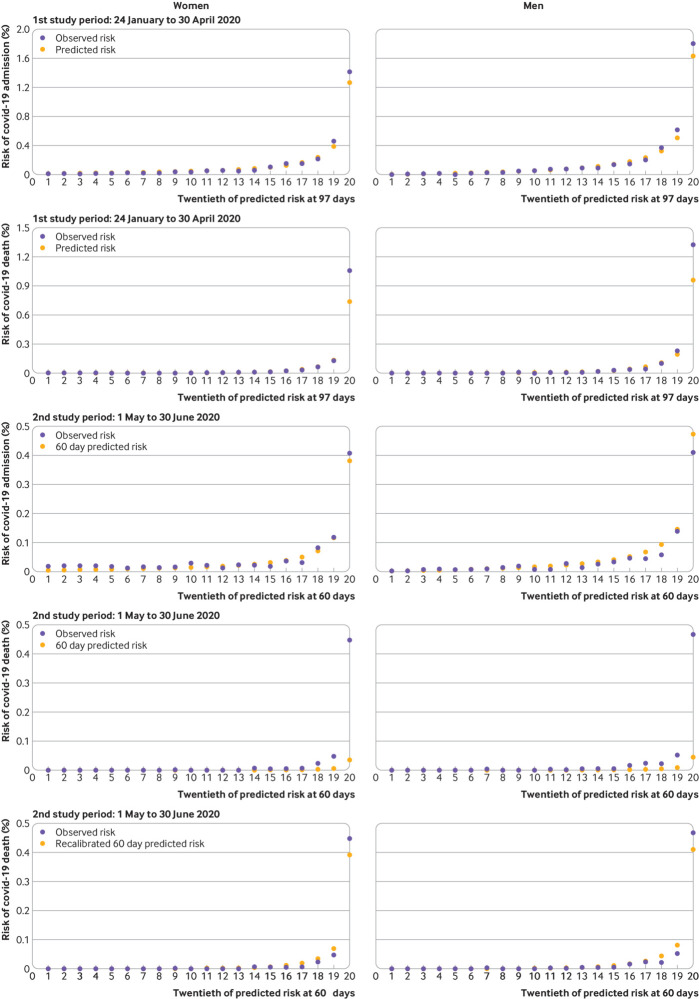

Figure 6 (top two rows) shows the calibration plots for the covid-19 related hospital admission equation and for the covid-19 related death equation in the first validation period. These show that both sets of equations were well calibrated in the first time period except for a small degree of under-prediction in the highest risk category for mortality. In the second validation period, calibration was good for the hospital admission outcome but not for the mortality outcome at the high levels of risk (fig 6, third and fourth rows). The calibration was improved with recalibration, with observed risks more closely matching the predicted risks (fig 6, bottom row).

Fig 6.

Predicted and observed risk of covid-19 related hospital admission and death in validation cohort in first study period (24 January to 30 April 2020) and in second study period (1 May to 30 June 2020), and recalibrated predicted and observed risk of covid-19 related death in validation cohort in second study period (1 May to 30 June 2020)

Risk stratification

Table 4 shows the sensitivity values for the mortality equation over 97 days evaluated at different thresholds based on the centiles of the predicted absolute risk in the validation cohort. For example, it shows that 75.73% of deaths occurred in people in the top 5% for predicted absolute risk of death from covid-19 (predicted absolute risks above 0.237%). People in the top 20% for predicted absolute risk of death accounted for 94% of deaths, and the top 25% accounted for 95.99% of deaths. Supplementary table G shows a similar table based on centiles of relative risk. This example shows that 50.93% of deaths occurred in people in the top 5% for predicted relative risk of covid-19 related death (predicted relative risk above 5.3). People in the top 20% for predicted relative risk of death accounted for 77.53% of deaths, and the top 25% accounted for 81.59% of deaths. As an example, table 5 shows characteristics of the 5% of patients with the highest predicted absolute risk of death for all individuals aged 19-100 years.

Table 4.

Sensitivity for covid-19 related death over 97 days in validation cohort (24 January to 30 April 2020) comprising 2 173 056 patients with 1722 covid-19 related deaths at different absolute risk thresholds*

| Top centile | Total patients in each centile | Absolute risk centile cut-off (%) | Total deaths in each absolute risk centile | Cumulative % deaths based on absolute risk (sensitivity†) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21730 | 0.9093 | 708 | 41.11 |

| 2 | 21731 | 0.5182 | 263 | 56.39 |

| 3 | 21730 | 0.3703 | 136 | 64.29 |

| 4 | 21731 | 0.2892 | 105 | 70.38 |

| 5 | 21730 | 0.2369 | 92 | 75.73 |

| 6 | 21731 | 0.1990 | 58 | 79.09 |

| 7 | 21730 | 0.1702 | 35 | 81.13 |

| 8 | 21731 | 0.1473 | 46 | 83.80 |

| 9 | 21731 | 0.1288 | 26 | 85.31 |

| 10 | 21730 | 0.1135 | 24 | 86.70 |

| 11 | 21731 | 0.1004 | 18 | 87.75 |

| 12 | 21730 | 0.0895 | 19 | 88.85 |

| 13 | 21731 | 0.0800 | 19 | 89.95 |

| 14 | 21730 | 0.0719 | 18 | 91.00 |

| 15 | 21731 | 0.0647 | 7 | 91.41 |

| 16 | 21730 | 0.0584 | 5 | 91.70 |

| 17 | 21731 | 0.0528 | 14 | 92.51 |

| 18 | 21731 | 0.0477 | 12 | 93.21 |

| 19 | 21730 | 0.0432 | 9 | 93.73 |

| 20 | 21731 | 0.0393 | 5 | 94.02 |

| 21 | 21730 | 0.0357 | 6 | 94.37 |

| 22 | 21731 | 0.0325 | 9 | 94.89 |

| 23 | 21730 | 0.0296 | 6 | 95.24 |

| 24 | 21731 | 0.0270 | 4 | 95.47 |

| 25 | 21731 | 0.0246 | 9 | 95.99 |

Centile value giving cut-off of predicted risk over 97 days for defining each group of absolute risk.

Percentage of total deaths over 97 days that occurred within group of patients above predicted risk threshold.

Table 5.

Summary characteristics for top 5% of patients with highest predicted absolute risks of covid-19 death. Table shows results for all members of validation cohort

| Characteristic | Total population (n=2 173 056) | Total (column %) in top 5% predicted risk (n=108 652) | Top 5% predicted risk (row %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 1 075 788 | 63 755 (58.68) | 5.93 |

| Age band: | |||

| 19-29 years | 424 125 | * | * |

| 30-39 years | 417 590 | * | * |

| 40-49 years | 358 695 | 97 (0.09) | 0.03 |

| 50-59 years | 358 820 | 1028 (0.95) | 0.29 |

| 60-69 years | 270 340 | 6428 (5.92) | 2.38 |

| 70-79 years | 209 557 | 25 542 (23.51) | 12.19 |

| ≥80 years | 133 929 | 75 547 (69.53) | 56.41 |

| Ethnicity: | |||

| White | 1 780 507 | 90 958 (83.71) | 5.11 |

| Indian | 64 184 | 3034 (2.79) | 4.73 |

| Pakistani | 40 718 | 1863 (1.71) | 4.58 |

| Bangladeshi | 28 050 | 1247 (1.15) | 4.45 |

| Other Asian | 42 607 | 1489 (1.37) | 3.49 |

| Caribbean | 28 741 | 3702 (3.41) | 12.88 |

| Black African | 58 115 | 2884 (2.65) | 4.96 |

| Chinese | 29 972 | 603 (0.55) | 2.01 |

| Other ethnic group | 100 162 | 2872 (2.64) | 2.87 |

| Townsend deprivation fifth: | |||

| 1 (most affluent) | 446 359 | 20 010 (18.42) | 4.48 |

| 2 | 428 735 | 20 524 (18.89) | 4.79 |

| 3 | 439 846 | 23 758 (21.87) | 5.40 |

| 4 | 436 574 | 23 644 (21.76) | 5.42 |

| 5 (most deprived) | 409 917 | 20 437 (18.81) | 4.99 |

| Townsend not recorded | 11 625 | 279 (0.26) | 2.40 |

| Accommodation: | |||

| Neither homeless or care home resident | 2 155 199 | 97 210 (89.47) | 4.51 |

| Care home or nursing home resident | 14 057 | 11 269 (10.37) | 80.17 |

| Homeless | 3800 | 173 (0.16) | 4.55 |

| Body mass index: | |||

| <18.5 | 59 376 | 4188 (3.85) | 7.05 |

| 18.5-24.99 | 711 186 | 33 122 (30.48) | 4.66 |

| 25-29.99 | 596 942 | 34 044 (31.33) | 5.70 |

| 30-34.99 | 278 830 | 18 762 (17.27) | 6.73 |

| ≥35 | 160 345 | 13 086 (12.04) | 8.16 |

| Not recorded | 366 377 | 5450 (5.02) | 1.49 |

| Chronic kidney disease (CKD) | |||

| No CKD | 2 087 614 | 68 710 (63.24) | 3.29 |

| CKD3 | 76 600 | 34 418 (31.68) | 44.93 |

| CKD4 | 4648 | 3194 (2.94) | 68.72 |

| CKD5 only | 2527 | 1722 (1.58) | 68.14 |

| CKD5 with dialysis | 585 | 274 (0.25) | 46.84 |

| CKD5 with transplant | 1082 | 334 (0.31) | 30.87 |

| Learning disability: | |||

| No learning disability | 2 137 759 | 103 919 (95.64) | 4.86 |

| Learning disability | 34 257 | 4473 (4.12) | 13.06 |

| Down’s syndrome | 1040 | 260 (0.24) | 25.00 |

| Chemotherapy: | |||

| No chemotherapy in previous 12 months | 2 164 341 | 105 131 (96.76) | 4.86 |

| Chemotherapy group A | 3343 | 1100 (1.01) | 32.90 |

| Chemotherapy group B | 5032 | 2223 (2.05) | 44.18 |

| Chemotherapy group C | 340 | 198 (0.18) | 58.24 |

| Cancer and immunosuppression: | |||

| Blood cancer | 10 359 | 3084 (2.84) | 29.77 |

| Bone marrow or stem cell transplant in previous 6 months | 73 | 56 (0.05) | 76.71 |

| Respiratory cancer | 4549 | 1722 (1.58) | 37.85 |

| Radiotherapy in previous 6 months | 4346 | 1709 (1.57) | 39.32 |

| Solid organ transplant | 1147 | 283 (0.26) | 24.67 |

| GP prescribed immunosuppressant medication | 2814 | 455 (0.42) | 16.17 |

| Prescribed leukotriene or LABA | 45 905 | 9591 (8.83) | 20.89 |

| Prescribed regular prednisolone | 11 617 | 4518 (4.16) | 38.89 |

| Sickle cell disease | 717 | 117 (0.11) | 16.32 |

| Other comorbidities: | |||

| Type 1 diabetes | 10 337 | 861 (0.79) | 8.33 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 137 092 | 40 674 (37.44) | 29.67 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 51 026 | 16 708 (15.38) | 32.74 |

| Asthma | 299 632 | 14 860 (13.68) | 4.96 |

| Rare pulmonary diseases | 11 748 | 2868 (2.64) | 24.41 |

| Pulmonary hypertension or pulmonary fibrosis | 1891 | 1061 (0.98) | 56.11 |

| Coronary heart disease | 77 035 | 29 476 (27.13) | 38.26 |

| Stroke | 47 513 | 20 384 (18.76) | 42.90 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 52 764 | 23 579 (21.70) | 44.69 |

| Congestive cardiac failure | 25 255 | 14 897 (13.71) | 58.99 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 38 962 | 10114 (9.31) | 25.96 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 16 463 | 8005 (7.37) | 48.62 |

| Congenital heart disease | 11 344 | 1288 (1.19) | 11.35 |

| Dementia | 21 984 | 19 829 (18.25) | 90.20 |

| Parkinson’s disease | 5736 | 2847 (2.62) | 49.63 |

| Epilepsy | 29 031 | 3503 (3.22) | 12.07 |

| Rare neurological conditions | 6804 | 1092 (1.01) | 16.05 |

| Cerebral palsy | 2433 | 233 (0.21) | 9.58 |

| Severe mental illness | 246 668 | 17 428 (16.04) | 7.07 |

| Osteoporotic fracture | 87 595 | 15 933 (14.66) | 18.19 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis or SLE | 21 391 | 3251 (2.99) | 15.20 |

| Cirrhosis of liver | 4442 | 1054 (0.97) | 23.73 |

GP=general practitioner; LABA=long acting β agonist; SLE=systemic lupus erythematosus.

Values suppressed owing to small numbers <15.

Supplementary figures G and H show two clinical examples from the web calculator (https://qcovid.org/BMJ/), showing the absolute and relative risk of catching and dying from covid-19 and the risk of hospital admission due to covid-19. It also shows a ranking of mortality risk based on centiles across the validation cohort. Supplementary figure G shows a 55 year old black African man with type 2 diabetes, a body mass index of 27.7, and no other risk factors. His absolute risk of catching and dying from covid-19 over the 90 day period is 0.1095% (or 1 in 913). His relative risk compared with a white man aged 55 years and a body mass index of 25 is 10.84. The graph shows that he is in the top 10% of the population at highest risk. Supplementary figure H shows a 30 year old white woman with Down’s syndrome with a body mass index of 40. Her absolute risk of catching and dying from covid-19 is 0.024% (or 1 in 4184). Her relative risk compared with a white woman aged 30 years with a body mass index of 25 and no other risk factors is 59.75, and the rank is 75. Her absolute risk of admission to hospital with covid-19 over 90 days is 1 in 272.

Discussion

We have developed and evaluated a novel clinical risk prediction model (QCOVID) to estimate risks of hospital admission and mortality due to covid-19. We have used national linked datasets from general practice and national SARS-CoV-2 testing, death registry, and hospital episode data for a sample of more than 8 million adults representative of the population of England. The risk models have excellent discrimination (Harrell’s C statistics >0.9 for the primary outcome). Although the calibration for the hospital admission outcome was good in both time periods, some under-prediction existed for the mortality outcome in the second validation cohort, which improved after recalibration. The recalibration method could be used to transport the risk models to other settings or time periods with different absolute risks of covid-19. QCOVID represents a new approach for risk stratification in the population. It could also be deployed in several health and care applications, either during the current phase of the pandemic or in subsequent “waves” of infection (with recalibration as needed). These could include supporting targeted recruitment for clinical trials, prioritisation for vaccination, and discussions between patients and clinicians on workplace or health risk mitigation—for example, through weight reduction as obesity may be an important modifiable risk factor for serious complications of covid-19 if a causal association is established.10 Although QCOVID has been specifically designed to inform UK health policy and interventions to manage covid-19 related risks, it also has international potential, subject to local validation. One of the variables in our model (the Townsend measure of deprivation) may need to be replaced with locally available equivalent measures, or some recalibration may be needed. Previous risk prediction models based on QResearch have been validated internationally and found to have good performance outside of the UK.29 30

Comparison with other studies

Although similarities exist between our study and the recently reported analysis of risk factors from another English general practice database using a different clinical computer system, our project had a different aim—namely, to develop and evaluate a risk prediction model. We used a more comprehensive outcome (including deaths in patients with positive tests for SARS-CoV-2), a much wider range of predictors, and a more granular assessment of ethnicity and body mass index. Our C statistic for mortality (>0.92) is substantially higher than the previous study’s reported value of 0.77.31 Other prediction models have been reported, although these focus on other outcomes of covid-19, including risk of admission to intensive care or death following a positive test, or clinical decision tools that integrate biochemical and imaging parameters to aid diagnostis.13 However, most such studies are at high risk of bias, as they have been developed in highly selected cohorts, have limited transparency, are likely to have optimistic reported performance, or did not use covid-19 specific data.13 This study represents a substantial improvement on previously developed risk algorithms in terms of the size and representativeness of the study population, the richness of data linkages enabling accurate ascertainment of cases (including both in-hospital and out of hospital deaths) across the health network, and the breadth of candidate predictor variables considered. Importantly, it analyses risks at the population level, rather than risks in people with confirmed or suspected infection, and may have relevance for shielding or other policies that seek to mitigate risk of viral exposure.

Complexities of modelling

Several complexities of modelling adverse risks from covid-19 in the general population warrant discussion. We used a general population approach which, although not able to incorporate all determinants of being infected, offers an overall estimate of risk of adverse outcomes from covid-19 that could be used in discussions between clinicians and patients about adjustment of lifestyle or occupational and behavioural factors that could limit viral exposure. Our model predicts risks of “catching covid-19 and then having a severe outcome,” on the basis of data collected during the first peak of the pandemic. The endpoint in this study examines a risk trajectory that comprises two elements: becoming infected, which is predominantly a function of behavioural/environmental factors including occupation, local infection rate, and numbers of social interactions; and risk of hospital admission and death due to the infection, which is arguably primarily driven by “vulnerability” (that is, biological/physiological factors including age, sex, body mass index, comorbidities, and medications). Although producing a prediction model for risk of “death if infected” is feasible in principle, this approach is not yet possible owing to the approach to testing in the UK and the context of an as yet incompletely quantified degree of asymptomatic background transmission. Limited covid-19 testing data are available, but the difficulty is that no systematic community testing was done in the UK during the study period, so only patients unwell enough to attend hospital were tested. This means that a risk score developed in those who tested positive would overestimate risks of severe outcomes. As more widespread testing is done and those data become available, we will be able to update the model to take background infection rates into account and also model regional differences. Although the absolute risk levels will of course change over time, depending on the incidence of the disease, our analysis over two validation time periods indicates that the relative risk measures and discrimination are likely to remain stable.

Secondly, the model estimates the absolute risk for a non-infected individual in the general population of becoming infected and then dying (or needing to be admitted to hospital) from the virus over a 97 day period. Although many more than 40 000 people have died from covid-19 in the UK to date, when the denominator is a population of multi-millions, the absolute risk for most people may be low. Therefore, when conveying this type of risk score to an individual, due emphasis is needed on the different meanings of absolute and relative risk.

Thirdly, the absolute risk of catching covid-19 depends not only on the incidence of the infection but also on the number of people one gets close to. For this reason, non-pharmacological interventions such as social distancing and shielding were introduced in the UK during the study period. We have included some measures of multi-occupancy, as we have factored care homes into the analysis. The data generated during the study period will therefore be affected by the uptake of interventions such as social distancing and shielding, intended to mitigate the risks of SARS-CoV-2 infection. This could result in underestimation of some model coefficients and hence underestimation of absolute risk in people who were shielded. Also, as this is a prediction model derived from an observational study, the associations estimated for individual predictor variables should not be interpreted as causal effects.

However, ethical questions must be considered regarding how the tools may be used. We have presented two ways of stratifying risk based on either absolute or relative risk measures with associated centile values, but the choice of whether to have a threshold (given that risk is a continuous measure), and if so what threshold, will depend on the purpose for which the risk assessment tool is to be used, the available resources, and the ethical framework for decision making. We have analysed this within the “four ethical principles” framework that is widely used in medical decision making. The four principles are autonomy, beneficence, justice, and non-maleficence.32 The new risk equations, when implemented in clinical software, are designed to provide more accurate information for patients and clinicians on which to base decisions, thereby promoting shared decision making and patient autonomy. They are intended to result in clinical benefit by identifying where changes in management are likely to benefit patients, thereby promoting the principle of beneficence. Justice can be achieved by ensuring that the use of the risk equations results in fair and equitable access to health services that is commensurate with patients’ level of risk. Lastly, the risk assessment must not be used in a way that causes harm either to the individual patient or to others (for example, by introducing or withdrawing treatments where this is not in the patient’s best interest), thereby supporting the non-maleficence principle. How this applies in clinical practice will naturally depend on many factors, especially the patient’s wishes, the evidence base for any interventions, the clinician’s experience, national priorities, and the available resources. The risk assessment equations therefore supplement clinical decision making and do not replace it. With these caveats, the predicted risk estimates can be used to identify people at higher risk, to inform shared decision making between healthcare professionals and service users, or for population level stratification.

Strengths and limitations of study

Our study has some major strengths, but some important limitations, which include the specific factors related to covid-19 along with others that are similar to those for a range of other widely used clinical risk prediction algorithms developed using the QResearch database.14 15 16 Key strengths include the use of a very large validated data source that has been used to develop other risk prediction tools; the wealth of candidate risk predictors; the prospective recording of outcomes and their ascertainment using multiple national level database linkage; lack of selection, recall and respondent biases; and robust statistical analysis. We have used non-linear terms for body mass index and age. We examined interaction terms, which show increased risks at younger ages for adults with type 2 diabetes. We also established a new linkage to the systemic anti-cancer therapy (SACT) database for chemotherapy prescribed and administered in secondary care (which may not be recorded well in general practice software) to circumvent possible missing data for this important variable.

Specific limitations include the occurrence of shielding during the study period and that the study was conducted during the first phase of the UK epidemic. We have accounted for many risk factors for covid-19 mortality, but risks may be conferred by some rare medical conditions or other factors such as occupation that have not yet been observed or are poorly recorded in general practice or hospital data. In particular, the model does not include two important predictors—namely, prevailing infection rate and personal social distancing measures. A lack of comprehensive testing has led to some missing data on covid-19 admissions and/or deaths, which means that development of a valid model for predicting death in people infected with SARS-CoV-2 is not yet possible. We acknowledge that absolute risks are changing during the course of the pandemic, so these should be interpreted with caution. However, we would expect predictors of risk, relative risk measures, and discrimination to be more stable over time, which is consistent with the results from our temporal validation. Although this tool was modelled on the best available data from the first wave of the pandemic, it will be updated as further testing and outcome data accrue, immunity levels change, and (potentially) a vaccine becomes available. Nevertheless, having a risk score available at this stage of the pandemic may be useful to identify people at high risk before a vaccine or treatment is available.

We have reported a validation in each of two time periods using practices from QResearch, but these practices were completely separate from those used to develop the model. We have used this approach previously to develop and validate other widely used prediction models. When these have been further externally validated on completely different clinical databases, by ourselves and others, the results have been very similar.33 34 35 Work is already under way to evaluate the models in external datasets across all four nations of the UK and to integrate the algorithms within NHS clinical software systems.

Policy implication and conclusions

This study presents robust risk prediction models that could be used to stratify risk in populations for public health purposes in the event of a “second wave” of the pandemic and support shared management of risk. We anticipate that the algorithms will be updated regularly as understanding of covid-19 increases, as more data become available, as behaviour in the population changes, or in response to new policy interventions. It is important for patients/carers and clinicians that a common, appropriately developed, evidence based model exists that is consistently implemented and is supported by the academic, clinical, and patient communities. This will then help to ensure consistent policy and clear national communication between policy makers, professionals, employers, and the public.

What is already known on this topic

Public policy measures and clinical risk assessment relevant to covid-19 can be aided by rigorously developed and validated risk prediction models

Published risk prediction models for covid-19 are subject to a high risk of bias with optimistic reported performance, raising concern that these models may be unreliable when applied in practice

What this study adds

Novel clinical risk prediction models (QCOVID) have been developed and evaluated to identify risks of short term severe outcomes due to covid-19

The risk models have excellent discrimination and are well calibrated; they will be regularly updated as the absolute risks change over time

QCOVID has the potential to support public health policy by enabling shared decision making between clinicians and patients, targeted recruitment for clinical trials, and prioritisation for vaccination

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of EMIS practices who contribute to QResearch and EMIS Health and the Universities of Nottingham and Oxford for expertise in establishing, developing, or supporting the QResearch database. This project involves data derived from patient level information collected by the NHS, as part of the care and support of cancer patients. The data are collated, maintained, and quality assured by the National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service, which is part of Public Health England (PHE). Access to the data was facilitated by the PHE Office for Data Release. The Hospital Episode Statistics data used in this analysis are reused by permission from NHS Digital, which retains the copyright in that data. We thank the Office for National Statistics (ONS) for providing the mortality data. NHS Digital, PHE, and the ONS bear no responsibility for the analysis or interpretation of the data. We express our gratitude to Anne Rigg, Nisha Shaunak, Tom Charlton, Ana Montes, Claire Harrison, Susan Robinson, David Wrench, Matthew Streetly, Omer BenGal, Doraid Alrifai, and Rajjinder Nijjar for aiding the authors (notably PJ and JHC) with the classification of agents on the SACT dataset linkage used in this study and to David Coggon for general comments on the study protocol and interpretation.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Web appendix: Supplementary materials

Contributors: JHC, CC, AKC, RK, KDO, PH, and NM led study conceptualisation. All authors contributed to the development of the research question and study design, with development of advanced statistical aspects led by JHC, CC, RK, KDO, and AKC. JHC, AKC, CC, JB, and PJ were involved in data specification, curation, and collection. JHC and AKC developed, checked, or updated clinical code groups. JHC did the statistical analyses, which were checked by CC. JHC developed the software for the web calculator. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results. AKC and JHC wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. JHC is the guarantor.

Funding: This study is funded by a grant from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) following a commission by the Chief Medical Officer for England, whose office contributed to the development of the study question, facilitated access to relevant national datasets, and contributed to interpretation of data and drafting of the report.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: JHC has received grants from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford, John Fell Oxford University Press Research Fund, Cancer Research UK (grant number C5255/A18085) through the Cancer Research UK Oxford Centre, and the Oxford Wellcome Institutional Strategic Support Fund (204826/Z/16/Z) during the conduct of the study, is an unpaid director of QResearch, a not-for-profit organisation which is a partnership between the University of Oxford and EMIS Health who supply the QResearch database used for this work, and is a founder and shareholder of ClinRisk Ltd and was its medical director until 31 May 2019; ClinRisk produces open and closed source software to implement clinical risk algorithms (outside this work) into clinical computer systems; CC reports receiving personal fees from ClinRisk, outside this work; AH is a member of the New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group; PJ was employed by NHS England during the conduct of the study and has received grants from Epizyme and Janssen and personal fees from Takeda, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Novartis, Celgene, Boehringer Ingelheim, Kite Therapeutics, Genmab, and Incyte, all outside the submitted work; AKC has previously received personal fees from Huma Therapeutics, outside of the scope of the submitted work; RL has received grants from Health Data Research UK outside the submitted work; AS has received grants from the Medical Research Council (MRC) and Health Data Research UK during the conduct of the study; CS has received grants from the DHSC National Institute of Health Research UK, MRC UK, and the Health Protection Unit in Emerging and Zoonotic Infections (University of Liverpool) during the conduct of the study and is a minority owner in Integrum Scientific LLC (Greensboro, NC, USA) outside of the submitted work; KK has received grants from NIHR, is the national lead for ethnicity and diversity for the National Institute for Health Applied Research Collaborations, is director of the University of Leicester Centre for Black Minority Ethnic Health, was a steering group member of the Risk reduction Framework for NHS staff (chair) and for Adult care Staff, is a member of Independent SAGE, and is supported by the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration East Midlands (ARC EM) and the NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre (BRC); RHK was supported by a UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship (MR/S017968/1); KDO was supported by a grant from the Alan Turing Institute Health Programme (EP/T001569/1); no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the NHS, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Ethical approval: The QResearch ethics approval is with East Midlands-Derby Research Ethics Committee (reference 18/EM/0400).

Data sharing: To guarantee the confidentiality of personal and health information, only the authors have had access to the data during the study in accordance with the relevant licence agreements. Access to the QResearch data is according to the information on the QResearch website (www.qresearch.org).

The lead author affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: Patient representatives from the QResearch Advisory Board have advised on dissemination of studies using QResearch data, including the use of lay summaries describing the research and its findings.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center Global map. 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

- 2. Cowling BJ, Ali ST, Ng TWY, et al. Impact assessment of non-pharmaceutical interventions against coronavirus disease 2019 and influenza in Hong Kong: an observational study. Lancet Public Health 2020;5:e279-88. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30090-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Davies NG, Kucharski AJ, Eggo RM, Gimma A, Edmunds WJ, Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases COVID-19 working group Effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 cases, deaths, and demand for hospital services in the UK: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health 2020;5:e375-85. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30133-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:1054-62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA 2020;323:1891-2. 10.1001/jama.2020.6548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ 2020;368:m1091. 10.1136/bmj.m1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weiss P, Murdoch DR. Clinical course and mortality risk of severe COVID-19. Lancet 2020;395:1014-5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30633-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wadhera RK, Wadhera P, Gaba P, et al. Variation in COVID-19 Hospitalizations and Deaths Across New York City Boroughs. JAMA 2020;323:2192-5. 10.1001/jama.2020.7197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Le Brocq S, Clare K, Bryant M, Roberts K, Tahrani AA, writing group form Obesity UK. Obesity Empowerment Network. UK Association for the Study of Obesity Obesity and COVID-19: a call for action from people living with obesity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2020;8:652-4. 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30236-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sattar N, McInnes IB, McMurray JJV. Obesity Is a Risk Factor for Severe COVID-19 Infection: Multiple Potential Mechanisms. Circulation 2020;142:4-6. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Singh AK, Gillies CL, Singh R, et al. Prevalence of co-morbidities and their association with mortality in patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab 2020;10.1111/dom.14124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith GD, Spiegelhalter D. Shielding from covid-19 should be stratified by risk. BMJ 2020;369:m2063. 10.1136/bmj.m2063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wynants L, Van Calster B, Collins GS, et al. Prediction models for diagnosis and prognosis of covid-19 infection: systematic review and critical appraisal. BMJ 2020;369:m1328. 10.1136/bmj.m1328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Brindle P. Development and validation of QRISK3 risk prediction algorithms to estimate future risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2017;357:j2099. 10.1136/bmj.j2099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Development and validation of QDiabetes-2018 risk prediction algorithm to estimate future risk of type 2 diabetes: cohort study. BMJ 2017;359:j5019. 10.1136/bmj.j5019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Development and validation of QMortality risk prediction algorithm to estimate short term risk of death and assess frailty: cohort study. BMJ 2017;358:j4208. 10.1136/bmj.j4208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hippisley-Cox J, Clift AK, Coupland CAC, et al. Protocol for the development and evaluation of a tool for predicting risk of short-term adverse outcomes due to COVID-19 in the general UK population. medRxiv 2020:2020.06.28.20141986-2020.06.28. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KGM. Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:55-63. 10.7326/M14-0697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. RECORD Working Committee The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001885. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Townsend P, Davidson N. The Black report. Penguin, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999;94:496-509 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Royston P. Explained variation for survival models. Stata J 2006;6:1-14 10.1177/1536867X0600600105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Royston P, Sauerbrei W. A new measure of prognostic separation in survival data. Stat Med 2004;23:723-48. 10.1002/sim.1621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med 1996;15:361-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Steyerberg EW, Vickers AJ, Cook NR, et al. Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology 2010;21:128-38. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c30fb2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Newson RB. Comparing the predictive powers of survival models using Harrell’s C or Somers’ D. Stata J 2010;10:339-58 10.1177/1536867X1001000303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Booth S, Riley RD, Ensor J, Lambert PC, Rutherford MJ. Temporal recalibration for improving prognostic model development and risk predictions in settings where survival is improving over time. Int J Epidemiol 2020;dyaa030. 10.1093/ije/dyaa030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Riley RD, Ensor J, Snell KIE, et al. External validation of clinical prediction models using big datasets from e-health records or IPD meta-analysis: opportunities and challenges. BMJ 2016;353:i3140. 10.1136/bmj.i3140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pike MM, Decker PA, Larson NB, et al. Improvement in Cardiovascular Risk Prediction with Electronic Health Records. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 2016;9:214-22. 10.1007/s12265-016-9687-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kengne AP, Beulens JW, Peelen LM, et al. Non-invasive risk scores for prediction of type 2 diabetes (EPIC-InterAct): a validation of existing models. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2:19-29. 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70103-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 2020;584:430-6. 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gillon R. Medical ethics: four principles plus attention to scope. BMJ 1994;309:184-8. 10.1136/bmj.309.6948.184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Collins GS, Altman DG. An independent external validation and evaluation of QRISK cardiovascular risk prediction: a prospective open cohort study. BMJ 2009;339:b2584. 10.1136/bmj.b2584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]