ABSTRACT

Background and Aim:

The current trend for determining the effectiveness of new treatment or services provided for diabetes mellitus (DM) patients is based on assessing the improvement in both glycemic control and the patient quality of life. Many scales have been developed to assess quality of life among DM patients, but unfortunately, no one can be considered as gold standard. Therefore, this study aimed to develop and validate a brief and specific scale to assess quality of life among Iraqi type 2 DM patients.

Methods:

An extensive literature review was done using Google-Scholar and PubMed to find out scales that utilized to assess quality of life among DM patients. Four relevant scales, three diabetes specific and one general, were selected. The selected scales were carefully evaluated to find out domains that are commonly used to assess quality of life and then the items within the selected domains were reviewed to choose relevant and comprehensive items for Iraqi type 2 DM patients. Ten items were selected to formulate the quality of life scale for Iraqi DM patients (QOLSID). The content validity of QOLSID was established via an expert panel. For concurrent validity QOLSID was compared to glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C). For psychometric evaluation, a cross sectional study for 103 type 2 DM patients was conducted at the National Diabetes Center, Iraq. Test-retest reliability was measured by re-administering QOLSID to 20 patients 2-4 weeks later.

Results:

The internal consistency of the QOLSID was 0.727. All items had a corrected total-item correlation above 0.2. There was a negative significant correlation between QOLSID score and the HbA1C level (-0.518, P = 0.000). A significant positive correlation was obtained after re-testing (0.967, P = 0.000).

Conclusion:

The QOLSID is a reliable and valid instrument that can be used for assessing quality of life among Iraqi type 2 DM patients.

KEYWORDS: Diabetic patients, Iraq, quality-of-life scale

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic metabolic disease that is highly prevalent worldwide.[1] It is characterized by hyperglycemia due to insulin deficiency and/or resistance.[2] Uncontrolled hyperglycemia is the major factor for DM morbidity and mortality through induction of macro- and microvascular complications. It can also negatively affect on patients’ physical and psychological well-being and thus lower patients’ quality of life (QOL).[3,4,5] Therefore, the current trend for determining the effectiveness of new treatment or services provided for DM patients is based on assessing the improvement in both glycemic control and the patient QOL.[6,7,8] Many scales have been developed to assess QOL among DM patients, but unfortunately none of them can be considered as gold standard. In addition, most of these scales contain a lot of questions,[9] rendering them time-consuming and may result in lower rates of patient response,[10] and thus considered not suitable for use in clinical practice. Furthermore all of these scales are not specific for Iraqi DM patients because they were developed and validated in countries at which DM patients have different attitudes, health beliefs, social, and ethnic structures. Therefore, this study aimed to develop and validate a brief, comprehensive, and specific scale to assess QOL among Iraqi type 2 DM patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Developing the scale items

An extensive literature review was performed using Google Scholar and PubMed to find out scales that utilized to assess QOL among DM patients elsewhere. The following sets of keywords were used: “Quality of life, diabetes, and questionnaire” and “assessment, quality of life, and diabetes.” Many scales were found but only scales that matched the following criteria were selected: (1) published in English, (2) freely available, and (3) validated for use among type 2 DM patients. Four QOL scales were chosen; these include three diabetic-specific scales: Diabetes Quality of Life Clinical Trial Questionnaire (DQLCTQ-R),[11] Diabetes Quality of Life Brief Clinical Inventory (DQOL-BCI),[12] and Quality of Life Instrument for Indian Diabetes Patients (QOLID),[13] and one general QOL scale, the World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF).[14,15] The domains for all of the aforementioned scales were carefully evaluated, and only four major domains were selected based on their presence in at least 75% of the examined scales. The chosen domains included general health, social, psychological, and satisfaction issues. Satisfaction domain was developed to be comprehensive on all DM self-management practices rather than satisfaction to treatment only because it is well known that self-management practices can either positively[16] or negatively[17,18] affect on DM patient QOL.

All questions in the selected domains of the aforementioned scales were collected to generate a pool of questions. The generated pool consisted of 97 questions. Forty-seven questions were excluded either because of redundancy (38 questions) or because of irrelevance (9 questions) to Iraqi patients, such as questions asking about sexual behavior[19,20] or questions asking about enjoyment in life because such questions may lead to false negative results due to the uncomfortable living situation in Iraq, whereas other questions were irrelevant to elderly DM patients such as those asking about career and embarrassment.[21] Furthermore, a question asking about patients’ satisfaction in their knowledge was also considered irrelevant because it may result in false-positive results because most Iraqi DM patients did not receive sufficient education about their disease and treatment.[22] The remaining 50 questions were considered relevant; however, only 10 questions were chosen to make the drafted Quality of Life Scale for Iraqi DM patients (QOLSID) because all of the other remaining questions (40 questions) were directed to assess issues that already covered by the chosen questions (e.g., a question asks about satisfaction with ability to exercise can already cover questions asking about fatigue, energy level, and tiredness).

Translation

All of the drafted scale items were translated to Arabic language using the WHO forward and backward translation method. After the translation of these items, a slight modification was carried out on some items to ensure maximum suitability for the Iraqi patients. After writing the final version of the QOLSID, all Arabic items were translated to English by a forward–backward translation method also.

Content and face validity

For content validity, the drafted QOLSID in its two versions (Arabic and English) was sent to a group of experts in the area of DM management including two physicians, two DM educators, two pharmacists, and one public health specialist.

In this study, Lawshe’s[23] approach was chosen to determine content validity. All experts were asked to rate each question on 3-point scales: essential, useful but not essential, and not useful. The experts were asked to make comments about the need for additional items and on the language and wording issues.[24] Fortunately, all experts come into mutual agreement about essentiality of all scale items. Two experts made minor comments on the wording of two items in the Arabic version, which was then reworded according to their advice.

Face validity was performed by piloting the drafted scale—Arabic version (only) to a convenient sample of 10 DM patients at the same DM center. All patients were asked to read and fill in the questionnaire carefully and then asked to rate clarity and relevance of each question using dichotomous answer (yes or no). All scale items were rated as clear and relevant by the participants.

Concurrent validity

As QOL for type 2 DM patients is well correlated with glycemic control[25,26] and many other QOL scales were validated using HbA1c value,[11,27,28] the HbA1c value was chosen as a comparator to verify the concurrent validity of the QOLSID. HbA1c was measured using (i-chroma point of care apparatus, Boditech Med Incorporated, Republic of Korea).

Study design

A 4-month cross-sectional study was carried out starting from December 2017 at the National Diabetes Centre, Baghdad, Iraq. This study was ethically approved by the local Research Ethics Committee at Al-Rafidain University College and the National Diabetes Center, Baghdad, Iraq.

Sample size

The required sample size of this study was 100, because the QOLSID has 10 items, and there is an agreement that 10 participants per item can provide an adequate sample size for the validation of a newly developed scale.[29,30]

Patients’ selection

To get the required sample size of 100 DM patients, a convenient sample of 103 patients was recruited (response rate 97%). Iraqi adult patients who read and/or speak Arabic and are having type 2 DM for at least 6 months and being on the same antidiabetic medications for at least 3 months were included in this study. On the other hand, pregnant women and any patient with cognitive impairment and/or depression were excluded from participating in this stud.

The interview with each patient was done in a private room specially designed for educating patients about insulin therapy at the National Diabetes Centre In the interview, the aim of the study and study protocol were mentioned clearly. Only those who accept to provide their verbal informed consent were asked to fill in the QOLSID. The QOLSID was presented to the patients with limited educational level and to patients with visual problems via face-to-face interview. The participants need approximately 5–10 min to complete filling the QOLSID. To examine test-retest reliability, approximately one-fifth of the initial study sample was conveniently selected (n = 20).[31] Thus, a group of 20 diabetic patients were retested with the same questionnaire 2–4 weeks after the initial test.[32]

Statistical analysis

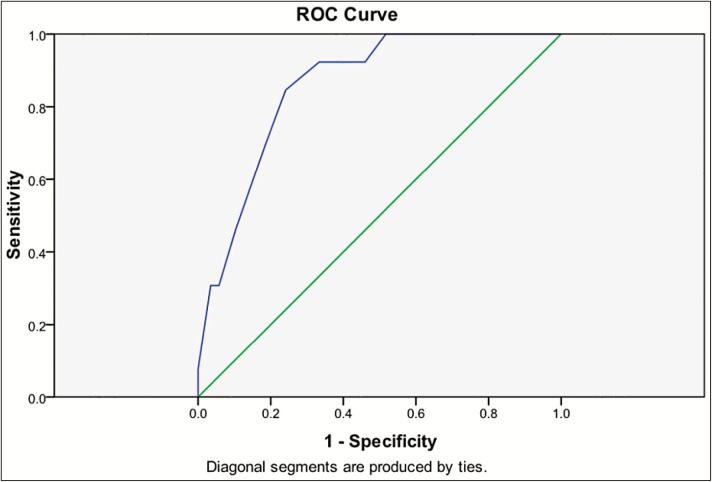

Data input and analysis were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 17, Chicago, Illinois. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation, whereas categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. The normality of distribution was tested by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Spearman’s ρ correlation test was used to know the correlation between the abnormally distributed continuous variables. A Cronbach α value was used to examine the internal consistency of the QOLSID. A Cronbach α value ≥0.7 was considered acceptable. A value higher than 0.2 for any corrected item-total correlation can be considered sufficient.[33] For test-retest reliability, Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to measure the score difference for each item, whereas Spearman’s correlation coefficient test was used to measure the correlation of the QOLSID total score before and after retesting. Moreover, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to measure the area under the ROC curve (AUC) and then to define the optimum cutoffs point that can classify patients according to the blood glucose target. Sensitivity and specificity were also measured at the optimal cutoff point. A P value of <0.05 was considered sufficient for reaching statistically significant differences.

RESULTS

Participants recruited in this study had an average age of 56.68 ± 9.35 with history of DM exceeding 11 years. Further details about participants’ demographic and clinical data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data of the participants

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Age years mean ± SD (range) | 56.68 ± 9.35 (36–74) |

| Gender | |

| Male, n (%) | 52 (52) |

| Female, n (%) | 48 (48) |

| Duration of DM years mean ± SD (range) | 11.56 ± 7.46 (0.25–31) |

| Treatment | |

| Tablet, n (%) | 44 (44) |

| Insulin, n (%) | 31 (31) |

| Mixed, n (%) | 25 (25) |

| Educational level | |

| Illiterate, n (%) | 5 (5) |

| Primary, n (%) | 11 (11) |

| Secondary, n (%) | 55 (55) |

| Diploma, n (%) | 6 (6) |

| College, n (%) | 18 (18) |

| Postgraduate, n (%) | 4 (4) |

| Comorbid disease, n (%) | 80 (80) |

| Patients with 1 comorbid condition, n (%) | 51 (51) |

| Patients with 2 or more comorbid conditions, n (%) | 29 (29) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 51 (51) |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 27 (27) |

| Ischemic heart diseases, n (%) | 12 (12) |

| Neuropathy, n (%) | 11 (11) |

| Thyroid disorders, n (%) | 4 (4) |

| Retinopathy, n (%) | 4 (4) |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 3 (3) |

| Osteoarthritis, n (%) | 2 (2) |

| Arrhythmia, n (%) | 2 (2) |

| Renal failure, n (%) | 1 (1) |

SD = standard deviation

Psychometric properties of the QOLSID

Reliability analysis

The Cronbach α of QOLSID was 0.727. This value will be increased to 0.740 if item 1 was excluded. The item-total correlations were more than 0.2 for all items of QOLSID [Table 2].

Table 2.

Reliability of QOLSID

| Item | Corrected item-total correlation | Cronbach α if item deleted |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.247 | 0.740 |

| 2 | 0.392 | 0.705 |

| 3 | 0.454 | 0.696 |

| 4 | 0.226 | 0.726 |

| 5 | 0.372 | 0.709 |

| 6 | 0.560 | 0.672 |

| 7 | 0.638 | 0.670 |

| 8 | 0.224 | 0.727 |

| 9 | 0.237 | 0.725 |

| 10 | 0.599 | 0.672 |

In Table 3, the correlation of the test-retest QOLSID total scores was 0.967 (P = 0.000). When the individual items in the QOLSID were analyzed, no any item was significantly different at test-retest (P > 0.05).

Table 3.

QOLSID test-retest reliability

| Item | Z score | P value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | −1.604 | 0.109 |

| 2 | −0.138 | 0.890 |

| 3 | −1.000 | 0.317 |

| 4 | −1.414 | 0.157 |

| 5 | −1.265 | 0.206 |

| 6 | −0.447 | 0.655 |

| 7 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| 8 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| 9 | −0.378 | 0.705 |

| 10 | −0.577 | 0.564 |

Concurrent validity

There was a significant but negative correlation between QOLSID score and HbA1c (Spearman’s ρ = −0.518, P = 0.000); this negative correlation was significant among all type 2 DM patients except those using a combination of oral and injectable antidiabetic agents [Table 4]. In addition, all QOLSID domains were positively correlated with total QOLSID score but negatively correlated with HbA1c values [Table 5].

Table 4.

Correlation of QOLSID score with HbA1c

| Parameter | Correlation coefficient | P value |

|---|---|---|

| All participants (n = 100) | −0.518 | 0.000 |

| Diabetic patients treated by oral antidiabetics (n = 44) | −0.562 | 0.000 |

| Diabetic patients treated by insulin (n = 31) | −0.363 | 0.045 |

| Diabetic patients treated by combination of insulin and oral antidiabetics (n = 25) | −0.364 | 0.074 |

Table 5.

Correlation of QOLSID domain score with HbA1c and total QOLSID score

| Domain | QOLSID total score | HbA1c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ coefficient | P value | ρ coefficient | P value | |

| Satisfaction | 0.914 | 0.000 | −0.474 | 0.000 |

| Health | 0.811 | 0.000 | −0.577 | 0.000 |

| Psychological | 0.723 | 0.000 | −0.214 | 0.033 |

| Social | 0.232 | 0.020 | −0.205 | 0.041 |

Known-group validity

There was a significant difference in QOLSID score between DM patients with comorbid disease and those without comorbid diseases. Additionally significant difference in QOLSID score was observed between participants with different glycemic control, gender, and duration of DM [Table 6].

Table 6.

Known-group validity of QOLSID

| Parameter | Variable | QOLSID score | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c | Poor control (n = 87) | 28.31 ± 5.36 | 0.000 |

| Good control (n = 13) | 34.54 ± 2.60 | ||

| Duration of DM | >10 years (n = 46) | 27.89 ± 5.40 | 0.026 |

| ≤10 years (n = 54) | 30.09 ± 5.40 | ||

| Gender | Female (n = 48) | 27.67 ± 5.94 | 0.017 |

| Male (n = 52) | 30.52 ± 4.75 | ||

| Comorbid disease | Presence of comorbid disease (n = 80) | 28.49 ± 5.70 | 0.032 |

| Absence of comorbid disease (n = 20) | 31.65 ± 3.70 |

QOLSID cutoff point

ROC analysis showed that area under the curve is 0.858 (95% confidence interval = 0.771–0.946; P = 0.000) and the optimal cut-point score of QOLSID to identify optimum glycemic control is ≥ 32.5 points; this score has 84.6% sensitivity and 75.9% specificity to predict patient with good glycemic control ([Table 7] and [Figure 1]).

Table 7.

Sensitivity and specificity of QOLSID

| Positive if greater than or equal to | Sensitivity | 1 (Specificity) |

|---|---|---|

| 12.0000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| 15.0000 | 1.000 | 0.989 |

| 20.5000 | 1.000 | 0.874 |

| 24.5000 | 1.000 | 0.782 |

| 26.5000 | 1.000 | 0.644 |

| 27.5000 | 1.000 | 0.586 |

| 29.5000 | 0.923 | 0.460 |

| 31.5000 | 0.923 | 0.333 |

| 32.5000 | 0.846 | 0.241 |

| 33.5000 | 0.692 | 0.184 |

| 35.5000 | 0.308 | 0.057 |

| 38.0000 | 0.077 | 0.000 |

Figure 1.

ROC curve for QOLSID score

DISCUSSION

This study showed that QOLSID has good internal consistency, reliability, validity (concurrent and known-group validity), sensitivity, and specificity.

The Cronbach α coefficient of QOLSID was more than 0.7, which match the recommended value for acceptance of any newly designed scale.[34] All the items showed acceptable corrected item-total correlations. In this regard, Cronbach α value can be increased slightly if one item (item 1) was excluded from the scale; however, this item was found to be highly related to QOL among Iraqi diabetic patients.[35] Meanwhile, the reported improvement in the Cronbach α by exclusion of this item was found to be minimal and nonsignificant.[36,37] Accordingly, this item was kept in the QOLSID.

All QOLSID items were not statistically different at test-retest. In addition, an excellent correlation was obtained between the test-retest QOLSID total scores. This indicates stable reliability of the designed scale.

This study also demonstrated a good and significant negative correlation between HbA1c values and the total QOLSID scores. In contrast to this finding, many studies denied the correlation between QOL and HbA1c among type 2 DM patients. However, most of these studies measured QOL through the use of diabetes-nonspecific QOL measures,[38,39] whereas a finding consistent with the current finding, QOL is well correlated with HbA1c, was found in studies that assessed QOL using diabetes-specific scales.[25,40]

In addition, all domains of the designed QOLSID had a significant inverse correlation with HbA1c. Similarly, other studies found a good correlation between overall health,[41] psychological domains, and HbA1c.[42] Meanwhile, no study showed a direct correlation between HbA1c and satisfaction domain. Other studies found a statistically significant different score in satisfaction to treatment between patients with different glycemic control (poor vs. good).[11,27]

Furthermore, this study showed a statistically significant difference in the QOLSID score between diabetic patients with different glycemic control; a similar finding was obtained with QOLID.[13] On the other hand, this study confirms known-group validity of QOLSID through the presence of a statistically significant difference in the QOLSID score according to gender, presence of comorbid diseases, and duration of DM. Similar finding of discriminant validity for other QOL scales was found concerning gender,[43,44] comorbidity,[13] and duration of DM.[45]

ROC analysis for the designed QOLSID showed that AUC was greater than 0.7, which can be considered within the accepted range;[46] this finding was in tune with many other studies that developed tools specific for diabetic patients.[47,48] Furthermore, a cutoff value of 32.5, which was obtained by the ROC analysis showed that that QOLSID had an acceptable sensitivity and specificity; however, the sensitivity of QOLSID was higher than its specificity. A similar finding was obtained in another QOL scale.[49]

The major limitation of this study was the small number of recruited diabetic patients. In addition, QOLSID was only validated for Iraqi type 2 DM patients, so further studies to confirm QOLSID validity among Arab type 2 DM patients are highly recommended.

CONCLUSION

The study demonstrates that the developed QOLSID has good internal consistency and reliability. QOLSID has a significant correlation with HbA1c. Therefore, it seems to be a reliable and valid instrument that can be used for assessing QOL among Iraqi type 2 DM patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ogurtsova K, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Huang Y, Linnenkamp U, Guariguata L, Cho NH, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates for the prevalence of diabetes for 2015 and 2040. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;128:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karalliedde J, Gnudi L. Diabetes mellitus, a complex and heterogeneous disease, and the role of insulin resistance as a determinant of diabetic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:206–13. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verma K, Dadarwal M. Diabetes and quality of life: a theoretical perspective. J Soc Health Diabetes. 2017;5:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanstone M, Rewegan A, Brundisini F, Dejean D, Giacomini M. Patient perspectives on quality of life with uncontrolled type 1 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2015;15:1–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gebremedhin T, Workicho A, Angaw DA. Health-related quality of life and its associated factors among adult patients with type II diabetes attending Mizan Tepi University Teaching Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2019;7:e000577. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2018-000577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishii H, Niiya T, Ono Y, Inaba N, Jinnouchi H, Watada H. Improvement of quality of life through glycemic control by liraglutide, a GLP-1 analog, in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: the PAGE1 study. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2017;9:3. doi: 10.1186/s13098-016-0202-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aso Y, Suzuki K, Chiba Y, Sato M, Fujita N, Takada Y, et al. Effect of insulin degludec versus insulin glargine on glycemic control and daily fasting blood glucose variability in insulin-naïve Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes: I’D GOT trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;130:237–43. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mostafa NM, Ahmed GH, Anwar W. Effect of educational nursing program on quality of life for patients with type II diabetes mellitus at Assiut University Hospital. J Nurs Edu Prac. 2018;8:61–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trikkalinou A, Papazafiropoulou AK, Melidonis A. Type 2 diabetes and quality of life. World J Diabetes. 2017;8:120–9. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v8.i4.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rolstad S, Adler J, Rydén A. Response burden and questionnaire length: is shorter better? A review and meta-analysis. Value Health. 2011;14:1101–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen W, Kotsanos JG, Huster WJ, Mathias SD, Andrejasich CM, Patrick DL. Development and validation of the Diabetes Quality of Life Clinical Trial Questionnaire. Med Care. 1999;37:AS45–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199904001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burroughs TE, Desikan R, Waterman BM, Gilin D, McGill J. Development and validation of the diabetes quality of life brief clinical inventory. Diabetes Spectrum. 2004;17:41–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagpal J, Kumar A, Kakar S, Bhartia A. The development of Quality of Life Instrument for Indian Diabetes patients (QOLID): a validation and reliability study in middle and higher income groups. J Assoc Physicians India. 2010;58:295–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. WHOQOL-BREF: introduction, administration, scoring and generic version of the assessment—field trial version. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1996. [Last accessed on 2017 Oct]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/76.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gholami A, Azini M, Borji A, Shirazi F, Sharafi Z, Zarei E. Quality. of life in patients with type 2 diabetes: application of WHOQOL-BREF scale. Shiraz E-Med J. 2013;14:162–71. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chew BH, Shariff-Ghazali S, Fernandez A. Psychological aspects of diabetes care: effecting behavioral change in patients. World J Diabetes. 2014;5:796–808. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v5.i6.796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lloyd C, Smith J, Weinger K. Stress and diabetes: a review of the links. Diabetes Spectrum. 2005;18:121–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khatatneh OA. Stress and quality of life among diabetic patients: a correlational study. Nat J Multidiscip Res Develop. 2018;3:30–3. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tourangeau R, Yan T. Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:859–83. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hammoud MM, White CB, Fetters MD. Opening cultural doors: providing culturally sensitive healthcare to Arab American and American Muslim patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1307–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu NF, Brown AS, Folias, Younge MF, Guzman SJ, Close KL, et al. Stigma in people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. Clin Diabetes. 2017;35:27–34. doi: 10.2337/cd16-0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mikhael EM, Hassali MA, Hussain SA, Shawky N. Self-management knowledge and practice of type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Baghdad, Iraq: a qualitative study. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2019;12:1–17. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S183776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers Psychol. 1975;28:563–75. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polit DF, Beck CT. The content validity index: are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29:489–97. doi: 10.1002/nur.20147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khanna A, Bush AL, Swint JM, Peskin MF, Street RL, Jr, Naik AD. Hemoglobin A1c improvements and better diabetes-specific quality of life among participants completing diabetes self-management programs: a nested cohort study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:48. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Somappa HK, Venkatesha M, Prasad R. Quality of life assessment among type 2 diabetic patients in rural tertiary centre. Int J Med Sci Pub Health. 2014;3:415–17. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin CY, Lee TY, Sun ZJ, Yang YC, Wu JS, Ou HT. Development of diabetes-specific quality of life module to be in conjunction with the World Health Organization Quality of Life scale brief version (WHOQOL-BREF) Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15:167. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0744-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bujang MA, Ismail M, Hatta NKBM, Othman SH, Baharum N, Lazim SSM. Validation of the Malay version of Diabetes Quality of Life (DQOL) questionnaire for adult population with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Malays J Med Sci. 2017;24:86–96. doi: 10.21315/mjms2017.24.4.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rattray J, Jones MC. Essential elements of questionnaire design and development. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:234–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson JR, Sharples S. Evaluation of human work. 4th ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chew BH, Mukhtar F, Sherina MS, Paimin F, Hassan NH, Jamaludin NK. The reliability and validity of the Malay version 17-item diabetes distress scale. Malays Fam Physician. 2015;10:22–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li TC, Lin CC, Liu CS, Li CI, Lee YD. Validation of the Chinese version of the diabetes impact measurement scales amongst people suffering from diabetes. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:1613–9. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-0024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. 4th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsang S, Royse CF, Terkawi AS. Guidelines. for developing, translating, and validating a questionnaire in perioperative and pain medicine. Saudi J Anaesth. 2017;11:S80–9. doi: 10.4103/sja.SJA_203_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Al-Byati AI, Wtwt MA. Quality of life and diet satisfaction in type II diabetes. Food Sci Qual Manag. 2014;24:18–35. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mortazavi F, Mousavi SA, Chaman R, Khosravi A. Validation of the breastfeeding experience scale in a sample of Iranian mothers. Int J Pediatr. 2014;2014:608657. doi: 10.1155/2014/608657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bijsmans ES, Jepson RE, Syme HM, Elliott J, Niessen SJ. Psychometric validation of a general health quality of life tool for cats used to compare healthy cats and cats with chronic kidney disease. J Vet Intern Med. 2016;30:183–91. doi: 10.1111/jvim.13656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lau CY, Qureshi AK, Scott SG. Association between glycaemic control and quality of life in diabetes mellitus. J Postgrad Med. 2004;50:189–93. discussion 194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zareipour MA, Ghojogh MG, Mahdi-akhgar M, Alinejad M, Akbari S. The. quality of life in relationship with glycemic control in people with type 2 diabetes. J Com Health Res. 2017;6:141–9. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prajapati VB, Blake R, Acharya LD, Seshadri S. Assessment. of quality of life in type II diabetic patients using the modified diabetes quality of life (MDQoL)-17 questionnaire. Braz J Pharm Sci. 2017;53:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al-Taie N, Maftei D, Kautzky-Willer A, Krebs M, Stingl H. Assessing the quality of life among patients with diabetes in Austria and the correlation between glycemic control and the quality of life. Prim Care Diabetes. 2020;14:133–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2019.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jahanlou AS, Karami NA. WHO quality of life-BREF 26 questionnaire: reliability and validity of the Persian version and compare it with Iranian diabetics quality of life questionnaire in diabetic patients. Prim Care Diabetes. 2011;5:103–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sreedevi A, Cherkil S, Kuttikattu DS, Kamalamma L, Oldenburg B. Validation of WHOQOL-BREF in Malayalam and determinants of quality of life among people with type 2 diabetes in Kerala, India. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2016;28:62–9S. doi: 10.1177/1010539515605888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hajian-Tilaki K, Heidari B, Hajian-Tilaki A. Are gender differences in health-related quality of life attributable to sociodemographic characteristics and chronic disease conditions in elderly people. Int J Prev Med. 2017;8:95. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_197_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sparring V, Nyström L, Wahlström R, Jonsson PM, Ostman J, Burström K. Diabetes duration and health-related quality of life in individuals with onset of diabetes in the age group 15-34 years—a Swedish population-based study using EQ-5D. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:377. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bekkar M, Djemaa HK, Alitouche TA. Evaluation measures for models assessment over imbalanced data sets. J Info Eng App. 2013;3:27–38. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arnould B, Bosch V, Benmedjahed K, Gueron B, Consoli SM, Martinez L, et al. PDB37 scoring and psychometric validation of a scale for diabetic patient profiling based on patient attitude towards insulin. Value Health. 2006;9:A235–6. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou Q, Peng M, Zhou L, Bai J, Tong A, Liu M, et al. Development and validation of a brief diabetic foot ulceration risk checklist among diabetic patients: a multicenter longitudinal study in China. Sci Rep. 2018;8:962. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19268-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silva PA, Soares SM, Santos JF, Silva LB. Cut-off point for WHOQOL-bref as a measure of quality of life of older adults. Rev Saude Publica. 2014;48:390–7. doi: 10.1590/S0034-8910.2014048004912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]