Abstract

In health insurance, a reimbursement mechanism refers to a method of third-party repayment to offset the use of medical services and equipment. This systematic review aimed to identify challenges and adverse outcomes generated by the implementation of reimbursement mechanisms based on the diagnosis-related group (DRG) classification system. All articles published between 1983 and 2017 and indexed in various databases were reviewed. Of the 1,475 articles identified, 36 were relevant and were included in the analysis. Overall, the most frequent challenges were increased costs (especially for severe diseases and specialised services), a lack of adequate supervision and technical infrastructure and the complexity of the method. Adverse outcomes included reduced length of patient stay, early patient discharge, decreased admissions, increased re-admissions and reduced services. Moreover, DRG-based reimbursement mechanisms often resulted in the referral of patients to other institutions, thus transferring costs to other sectors.

Keywords: Health Insurance, Third-Party Payments, Reimbursement Mechanisms, Diagnosis-Related Groups, Quality of Health Care, Patient Outcome Assessment, Systematic Review

The diagnosis-related group (drg) classification system is a method of categorising patients for health insurance purposes in order to control costs and facilitate repayment by third party providers for the use of medical services and equipment.1 Using this system, patients are classified according to a range of variables, including primary and secondary diagnoses, age, gender, the presence of comorbidities/complications and treatment(s) provided. The intention behind this type of system is to classify patients into a limited number of groups in order to form clinically meaningful yet relatively homogeneous resource consumption patterns.2 A DRG-based reimbursement mechanism was first introduced in the USA in 1983 as a component of the Medicare programme, before being adopted by other countries around the world soon thereafter.3

Although the primary goals of DRG-based reimbursement mechanisms vary worldwide, most aim to increase transparency and efficiency, especially in European countries.4–6 Indeed, increasing transparency, providing effective care, controlling costs and improving the quality of care are some of the advantages reported for this method of reimbursement in hospital settings.7 However, this type of system is also subject to various challenges and adverse outcomes, for instance by unintentionally encouraging hospitals to preferentially admit more cost-effective patients.8 It has also been claimed that this type of payment system inspires a shift from traditional inpatient to outpatient care as a cost-saving measure.9

Researchers have previously evaluated the effects of implementing DRG-based repayment systems.10 However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, none have yet sought to systematically evaluate the challenges and potential negative effects of this type of system. Therefore, the objective of this article was to systematically review the challenges and adverse outcomes generated by the implementation of DRG-based reimbursement mechanisms.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines.11 A literature search was conducted to identify all English-language articles assessing the challenges and adverse outcomes of DRG-based reimbursement mechanisms published between January 1983 and February 2017 and indexed in the Scopus® (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), MEDLINE® (National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland, USA) or Embase® (Elsevier) databases.

Search terms related to challenges and DRG-based reimbursement mechanisms were combined using Boolean operators (i.e. “challenge”, “barrier”, “problem”, “difficulty”, “disadvantage” OR “weakness” AND “DRG”, “diagnosis-related groups”, “case-mix” OR “case mix”) in order to identify relevant articles in which these terms appeared in the publication title, keywords and/or abstract. Following the literature search, identified articles were reviewed and the abstracts assessed by two evaluators to determine if they were fit for inclusion in the analysis. In cases of inter-evaluator disagreement, the full text of the articles was assessed in order to come to a consensus. Articles were selected for further full-text review if they explored the challenges and adverse outcomes generated by the implementation of a DRG-based reimbursement mechanism.

All types of articles except reviews and letter to editors were included in the analysis. Articles focusing on other mechanisms of reimbursement, such as fee-for-service or global budget systems, were excluded. In addition, articles focusing on the measurement, calculation, development and structure of the mechanism and those solely examining positive or beneficial outcomes were also excluded. Subsequently, the studies were assessed to determine their quality based on criteria proposed by Kmet et al.12 Depending on the design of the study, two evaluators independently ranked the studies using different sets of criteria for qualitative and quantitative studies. Any disagreements were discussed until a consensus was reached. Implementation challenges were categorised as either leadership-related, managerial, organisational, technical or personnel-related according to a previously described template.13 Adverse outcomes were classified as per the model developed by Fourie et al.9

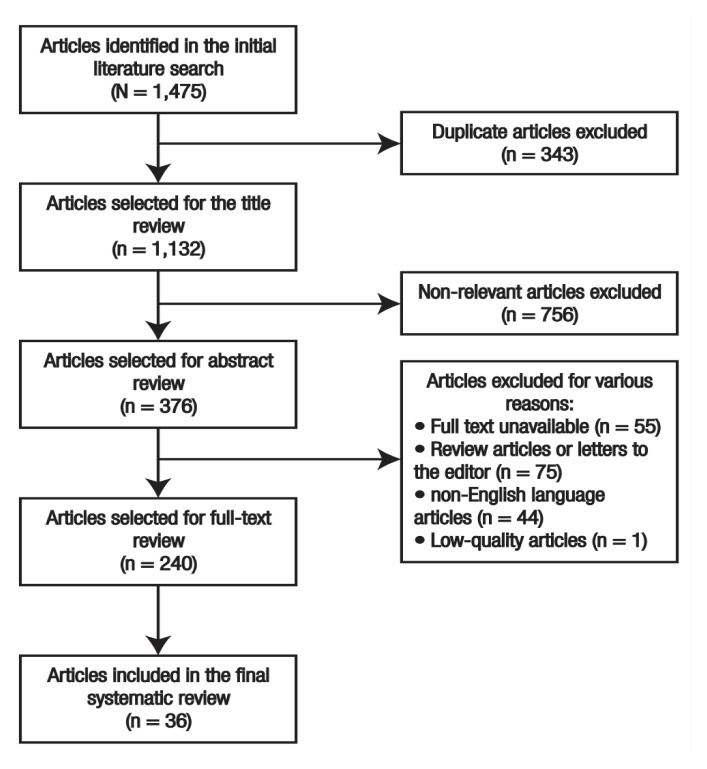

Overall, a total of 1,475 articles were identified during the literature search, of which 343 were duplicates. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, 892 non-relevant articles were also excluded. Subsequently, 240 articles underwent further full-text review; of these, 55 articles were excluded due to lack of access to the full text, 75 articles were review articles or letters to the editor and 44 were written in languages other than English. Furthermore, 29 articles were removed due to their lack of relevance and one qualitative article was excluded due to its low quality (i.e. a quality score of <50%). The final analysis therefore included 36 articles [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing the search strategy used to identify articles for inclusion in the systematic review.

A standardised data collection form was developed and completed by two researchers. The data collected included bibliographic information, the study setting, the country in which the study was performed and any challenges and adverse outcomes identified regarding the implementation of DRG-based reimbursement mechanisms. In cases of disagreement, a third researcher was contacted to provide the deciding vote. Data analysis was performed using an Excel spreadsheet, Version 2013 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, Washington, USA). The results were presented using descriptive statistics.

Results

A total of 36 articles assessing the challenges and adverse outcomes of DRG-based reimbursement mechanisms were included in the final analysis.14–49 Of these, the majority (n = 28; 77.8%) were published in 1990 or before.15–21,23,24,27–29,31,34,35,37–46,48,49 Most studies (n = 31; 86.1%) were set in the USA.15–24,28–46,48,49 Data collection strategies included observation (n = 2; 5.6%), in-person (n = 4; 11.1%) or telephone (n = 2; 5.6%) interviews, paper-based (n = 2; 5.6%) or electronic (n = 1; 2.8%) questionnaires, checklists (n = 1; 2.8%) and reviews of patient/hospital records (n = 26; 72.2%), annual reports (n = 8; 22.2%) and transcripts (n = 1; 2.8%).14–49

Almost two-thirds (n = 23; 63.9%) of the studies were set in hospitals, with the rest set in medical centres (n = 6; 16.7%), nursing homes (n = 2; 5.6%), trauma centres (n = 2; 5.6%), home health agencies (n = 2; 5.6%) or rehabilitation centres (n = 1; 2.8%).14–49 A total of 29 studies (80.6%) were quantitative in nature.14–17,19,21–24,26–28,31,32,34–40,42–49 In addition, there were three qualitative (8.3%) and four mixed-method (11.1%) studies.18,20,25,29,30,33,41 In terms of quality assessment, qualitative, quantitative and mixed-method studies received scores of >70%, >80% and >85%, respectively; however, quantitative studies were generally higher in quality compared to qualitative and mixed-method studies [Table 1].14–49

Table 1.

Quality analysis* of studies assessing the implementation of reimbursement mechanisms based on the diagnosis-related group classification system14–49

| Criteria | Score | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative studies | Qualitative studies | Mixed-method studies† | |||||||||||||||||||

| Multiple studies14,17,34–37,40,42–46 | Hensen et al.47 (2005) | Zhan et al.32 (2007) | Roeder et al.26 (2001) | Rogers et al.15 (1990) | Multiple studies16,31 | Patel48 (1988) | Horn et al.38 (1986) | Sanderson et al.27 (1989) | Multiple studies24,28,39 | Multiple studies19,23 | Hurley et al.21 (1990) | Wolfe and Detmer49 (1988) | Menke et al.22 (1998) | Bull41 (1988) | Notman et al.29 (1987) | Wisensale and Waldron33 (1991) | Sodzi-Tettey et al.25 (2012) | Goldberg and Estes18 (1990) | Lyles20 (1986) | Bray et al.30 (1994) | |

| Question/objective sufficiently described? | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Study design evident and appropriate? | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Context for the study clear? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Connection to a theoretical framework/wider body of knowledge? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Sampling strategy described, relevant and justified? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Data collection methods clearly described and systematic? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Data analysis clearly described and systematic? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Use of verification procedure(s) to establish credibility? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Reflexivity accounted for? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Method of subject/comparison group selection or source of information/input variables described and appropriate? | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Subject (and comparison group, if applicable) characteristics sufficiently described? | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| If interventional and random allocation was possible, was it described? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| If interventional and blinding of investigators was possible, was it reported? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| If interventional and blinding of subjects was possible, was it reported? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Outcome and (if applicable) exposure measure(s) well-defined and robust for measurement/misclassification bias? Means of assessment reported? | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Sample size appropriate? | N/A | N/A | 2 | 1 | 2 | N/A | 2 | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 2 | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A |

| Analytic methods described/justified and appropriate? | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Some estimate of variance is reported for the main results? | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Controlled for confounding? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| Results reported in sufficient detail? | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Conclusions supported by the results? | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Total score out of maximum | 18/18 | 16/18 | 18/20 | 16/20 | 20/22 | 16/18 | 18/20 | 19/20 | 15/18 | 19/20 | 18/20 | 20/22 | 21/22 | 19/22 | 16/20 | 14/18 | 14/20 | 37/40 | 33/42 | 34/40 | 33/38 |

N/A = not applicable.

As per criteria adapted from Kmet et al.12 Each criterion was assessed based on compliance, with scores of zero indicating no, 1 indicating partial compliance and 2 indicating full compliance.

For mixed-method studies, the qualitative and quantitative components were assessed separately, as indicated by plus signs (+) for criteria spanning both categories.

Table 2 summarises the studies which identified challenges in the implementation of DRG-based reimbursement mechanisms.25–49 Overall, 15 studies (41.7%) reported managerial challenges.25,30,32,34–36,38–40,42–47 Of these, 12 (80%) indicated that DRG-based reimbursement mechanisms were not suitable for certain services due to the high cost involved and the likelihood of financial loss, including skin care, trauma, fibrocystic disease, heart surgery, rare diseases, urology disorders, mental disorders, intensive care and the care of elderly and paediatric patients.34–36,38–40,42–47 The remaining three studies (20%) reported delayed reimbursement of hospital fees, increased expenses in educational hospitals (especially at baseline and in rural areas), poor medical recordkeeping and a lack of coding rules and standards.25,30,32

Table 2.

Challenges in the implementation of reimbursement mechanisms based on the diagnosis-related group classification system25–49

| Author and year of study | Setting | Type of study | Type of challenges | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management process | Organisation environment | Technical systems | Personnel | |||

| Sodzi-Tettey et al.25 (2012) | Ghana | Mixed-method |

|

|

|

|

| Roeder et al.26 (2001) | Germany | Quantitative | N/A | N/A |

|

N/A |

| Sanderson et al.27 (1989) | UK | Quantitative | N/A | N/A |

|

N/A |

| Horn et al.28 (1985) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A |

|

N/A |

| Notman et al.29 (1987) | USA | Qualitative | N/A | N/A | N/A |

|

| Bray et al.30 (1994) | USA | Mixed-method |

|

N/A | N/A |

|

| Bredenberg and Lagoe31 (1987) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A |

|

N/A |

| Zhan et al.32 (2007) | USA | Quantitative |

|

N/A |

|

N/A |

| Wisensale and Waldron33 (1991) | USA | Qualitative | N/A |

|

N/A |

|

| Muñoz et al.34 (1989) | USA | Quantitative |

|

N/A | N/A |

|

| Muñoz et al.35 (1988) | USA | Quantitative |

|

N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Zwanziger et al.36 (1991) | USA | Quantitative |

|

N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Vollertsen et al.37 (1988) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A |

|

N/A |

| Horn et al.38 (1986) | USA | Quantitative |

|

N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Thomas et al.39 (1988) | USA | Quantitative |

|

N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Pasternak et al.40 (1986) | USA | Quantitative |

|

N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Bull41 (1988) | USA | Qualitative | N/A | N/A | N/A |

|

| Joy and Yurt42 (1990) | USA | Quantitative |

|

N/A |

|

N/A |

| Muñoz et al.43 (1988) | USA | Quantitative |

|

N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Munoz et al.44 (1989) | USA | Quantitative |

|

N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Munoz et al.45 (1989) | USA | Quantitative |

|

N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Muñoz et al.46 (1989) | USA | Quantitative |

|

N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Patel48 (1988) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A | N/A |

|

| Wolfe and Detmer49 (1988) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A | N/A |

|

N/A = not available; DRG = diagnosis-related group.

Two studies (5.6%) examined organisation environment challenges, including poor compliance with guidelines, the misfiling and potential loss of patients records and physicians being pressured to discharge patients prematurely.25,33 Technical challenges were reported by nine studies (25%), particularly data coding and misclassification issues and DRG creeping (i.e. upgrading or upcoding patients).25–28,31,32,37,42,47 Personnel-related challenges were also reported by eight studies (22%); of these, one of the most important was a lack of familiarity among physicians with the DRG classification system and misconceptions regarding the objectives of the mechanism.25,29,30,33,34,41,42,48,49 No leadership challenges were reported by any of the studies.

Studies assessing adverse outcomes resulting from the implementation of DRG-based reimbursement mechanisms are described in Table 3.14–24,32–49 Overall, 11 studies (30.6%) examined the rate of early discharge, all of which noted an increase following implementation of the mechanism.15,17–20,22,23,33,41,47,48 The motivation for this was due to awareness on the part of both physicians and hospital administrators of patients’ costs and the desire to reduce the length of hospital stay and increase efficiency. Five studies (13.9%) evaluated readmission rates; of these, four (80%) observed that the implementation of DRG-based reimbursement mechanisms resulted in increased readmission due to the low quality of services provided initially and premature discharge.14,19,22,23 In contrast, the remaining study revealed no change in the rate of re-admission.17

Table 3.

Adverse outcomes resulting from the implementation of reimbursement mechanisms based on the diagnosis-related group classification system14–24,32–49

| Author and year of study | Setting | Type of study | Outcome | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of care | Access to care | Efficiency of care | ||||||||

| Early discharge | Readmission rate | Length of stay | Service provision | Mortality rate | Admission rate | Efficiency | Transfer of costs | |||

| Busato and von Below14 (2010) | Switzerland | Quantitative | N/A | Increased | Decreased | N/A | Decreased | Decreased | N/A | No effect |

| Rogers et al.15 (1990) | USA | Quantitative | Increased | N/A | N/A | N/A | No effect | No effect | N/A | Increased |

| Vulgaropulos et al.16 (1990) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A | Increased | N/A | N/A | N/A | Inefficient | N/A |

| Evans et al.17 (1990) | USA | Quantitative | Increased | No effect | Decreased | No effect | N/A | N/A | N/A | Increased |

| Goldberg and Estes18 (1990) | USA | Mixedmethod | Increased | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Decreased | N/A | Increased |

| Tresch et al.19 (1988) | USA | Quantitative | Increased | Increased | Decreased | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Increased |

| Lyles20 (1986) | USA | Mixed-method | Increased | N/A | N/A | N/A | Increased | N/A | N/A | Increased |

| Hurley et al.21 (1990) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Increased |

| Menke et al.22 (1998) | USA | Quantitative | Increased | Increased | Decreased | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Increased |

| Gay and Kronenfeld23 (1990) | USA | Quantitative | Increased | Increased | Decreased | N/A | Decreased | Decreased | N/A | Increased |

| Morrisey et al.24 (1988) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A | Decreased | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Increased |

| Zhan et al.32 (2007) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Inefficient | N/A |

| Wisensale and Waldron33 (1991) | USA | Qualitative | Increased | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Decreased | N/A | N/A |

| Muñoz et al.34 (1989) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Decreased | Inefficient | N/A |

| Muñoz et al.35 (1988) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Decreased | Inefficient | Increased |

| Zwanziger et al.36 (1991) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Inefficient | N/A |

| Vollertsen et al.37 (1988) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A | Decreased | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Increased |

| Horn et al.38 (1986) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A | Decreased | N/A | N/A | Decreased | Inefficient | N/A |

| Thomas et al.39 (1988) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Inefficient | N/A |

| Pasternak et al.40 (1986) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Inefficient | N/A |

| Bull41 (1988) | USA | Qualitative | Increased | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Increased |

| Joy and Yurt42 (1990) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Inefficient | N/A |

| Muñoz et al.43 (1988) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Inefficient | N/A |

| Munoz et al.44 (1989) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Inefficient | N/A |

| Munoz et al.45 (1989) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Inefficient | N/A |

| Muñoz et al.46 (1989) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Inefficient | N/A |

| Hensen et al.47 (2005) | Germany | Quantitative | Increased | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Inefficient | N/A |

| Patel48 (1988) | USA | Quantitative | Increased | N/A | N/A | Decreased | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Wolfe and Detmer49 (1988) | USA | Quantitative | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Decreased | N/A | N/A |

N/A = not available.

Nine studies (25%) measured length of patient stay.14,16,17,19,22–24,37,38 The majority (n = 8; 88.9%) found that the duration of hospital stay was reduced following the implementation of DRG-based reimbursement mechanisms; reasons for this included preserving resources, reducing costs and improving efficiency.14,17,19,22–24,37,38 Only one indicated that the average length of stay increased.16 Two studies (5.6%) examined the number of services provided to patients; in the first, there was no change in the number of services provided to patients after implementation of the reimbursement mechanism, while the second found that access to certain services or technologies was restricted after implementation of the reimbursement mechanism since the system increased performance monitoring.17,23

Mortality rate was assessed as an outcome in four studies (11.1%).14,15,20,23 One study showed that the mortality rate increased following implementation of a DRG-based reimbursement mechanism.20 In contrast, two studies showed a reduction in mortality rate.14,23 However, none of these studies reported a significant link between this outcome and the reimbursement mechanism. No change in mortality rate was observed in the final study.15 Nine studies (25%) evaluated the number of admissions.14,15,18,23,33,34,38,42,49 Of these, all but one (n = 8; 88.9%) indicated that the admission rate was reduced following implementation of the DRG-based reimbursement mechanisms in order to preserve resources.14,15,23,33,34,38,42,49 Hospital efficiency was assessed as an outcome in 14 studies (38.9%), all of which observed an increase in inefficiency.16,32,34–36,38–40,42–49

A total of 13 studies (36%) examined the impact of the reimbursement methods on transferring costs by directing patients to other healthcare institutions or centres.14,15,17–24,35,37,41 Only one of these indicated that implementation of the reimbursement mechanism did not lead to the transfer of costs to other institutions.14 The other studies found that patient costs were often transferred to other institutions in order to help reduce costs, especially for patients requiring rehabilitation services and those ≥65 years old. In particular, patients were often transferred to nursing homes or nursing care centres (n = 6; 46.2%), outpatient departments (n = 3; 23.1%), non-therapeutic sections (n = 1; 7.7%) and home-based services (n = 1; 7.7%).15,17–24,35,37,41

Discussion

Prospective reimbursement mechanisms, particularly those based on the DRG classification system, are usually implemented by healthcare policymakers in order to improve efficiency, ensure the optimal allocation of resources and control costs.50,51 Such mechanisms are also viewed favourably by insurance agencies as they allow for the distribution of financial risk between customers and service providers.52 However, the current review indicated that the implementation of these systems can be subject to various challenges, the most important of which was increased costs, especially for patients with severe diseases and those requiring specialised services.34–36,38–40,42–47 Other challenges included the failure to follow necessary guidelines, inadequate supervision, poor knowledge of the system among healthcare personnel (especially physicians and nurses), lack of technical infrastructure and the complexity of the method in question.25–27,29,32

Several studies noted that DRG-based reimbursement mechanisms failed to appropriately calculate disease severity and the cost of certain services.28,42,47 According to Leister and Stausberg, neglecting to consider disease risk and appropriate diagnostic classifications based on disease severity can cause hospitals to lose valuable resources when delivering care to high-risk patients and those with severe illnesses.53 In such cases, hospitals utilising these systems may choose not to admit such patients or to discharge them earlier in order to increase efficiency and cut costs. As such, DRG classification systems should be set up based on the number, type and severity of disease in each case and allow users to modify the assigned group based on these factors; this would ensure the more equitable calculation of fees and improve accessibility to healthcare and the quality of services rendered.28,34,35

Roeder et al. deemed the establishment of standard DRG units and different types of DRGs to be especially challenging.26 Another systematic review similarly highlighted this to be a major hindrance to the implementation of DRG-based reimbursement mechanisms in mainland China.54 Variations in the lifestyles and types of patients attending hospitals in different geographical regions can often result in differences in treatment patterns, medical costs, demand for services and the overall burden of disease. These represent major barriers to the data collection necessary to establish appropriate classification groups that reflect the actual economic and clinical situation.54 However, only one of the studies included in the current review referred to this problem.36

Other studies highlighted various organisational and technical challenges related to DRG-based reimbursement mechanisms, including inadequate filing systems, poor recordkeeping, the misclassification of diseases, irregularities in the coding of procedures and diagnoses and an overall lack of coding rules and standards.25–27,32 Indeed, some studies showed that classification problems led to the possibility of DRG creeping, which refers to a tendency to upgrade or upcode patients to allow for the hospital to receive higher reimbursements.32,37 In a study of 239 hospitals under the Medicare programme, Hsia et al. identified the rate of DRG coding errors to be 20.8%, of which 61.7% significantly favoured the hospital.55 In order to avoid this problem, coding standards and rules should be established and enforced in every hospital to ensure the correct codes are utilised.

Several studies in the current systematic review identified misconceptions among physicians and nurses regarding the DRG-based system, compounded by a lack of familiarity with the system.25,29 In some cases, healthcare personnel were uninterested in controlling costs.30 However, Wild et al. noted that sharing profits with physicians and encouraging them to help balance the budget would intensify conflict between physicians; moreover, they might feel torn between their commitments to providing the best care to the patient and controlling costs.7

One of the studies included in the current review noted that the DRG-based reimbursement mechanism increased costs, particularly in the year of implementation and in rural healthcare settings and educational hospitals.30 This finding may be due to several reasons, including a larger number of patients with severe illness presenting to educational hospitals, the lack of involvement of the physicians in improving the hospital’s financial performance, poor financial management and primary productivity control processes.30 On the other hand, DRG-based reimbursement mechanisms were deemed unsuitable in certain circumstances by other studies due to the lack of appropriate moderators, resulting in financial loss for the institution.38–40

Although most DRG-based reimbursement systems are introduced as cost-controlling measures, this can lead to undesirable outcomes that can affect the quality of the health services provided.4,56,57 This type of system results in a clear incentive for healthcare providers to preferentially admit patients with lower costs or restrict the provision of expensive services, leading to an unfair access to healthcare.58 In particular, vulnerable patient groups such as the elderly, children, immigrants and those suffering from chronic illness, heart failure or multiple illnesses may be disproportionately affected.34,48,49 Hospitals should therefore commit to providing an equal level of care to all patients by monitoring the performance of physicians. Additionally, providing standard protocols and guidelines for clinical decision-making may also be helpful to ensure a set level of quality of care while still controlling costs.

In the current review, DRG-based reimbursement systems also led to other alarming outcomes, such as reducing essential services and admissions, encouraging early discharge, reducing length of stay, increasing re-admission and transferring costs to other sectors by directing patients to other healthcare institutions.14–24,32–49 Other researchers have similarly shown that the implementation of this type of system often results in a reduction in length of stay in order to cut costs and improve hospital efficiency.54,59–61 In a two-year study conducted in the UK, Farrar et al. found that the length of stay among patients with pelvic fractures increased following implementation of a DRG-based reimbursement mechanism.62 Likewise, the implementation of such mechanisms have resulted in increased rates of early discharge and subsequent emergency visits.54,63–65 However, others noted no significant differences in readmission, mortality and admission rates following implementation of the system.60,66,67

It is as yet unfeasible to conclude that DRG-based reimbursement mechanisms are directly linked to substantial changes in quality of care for various reasons. First, none of the studies included in the present review could unequivocally attribute care outcomes to the implementation of the system, particularly since long-term effects can only be determined over years or even decades. Therefore, continuous quality monitoring is crucial at all hospitals. Second, while certain measurable clinical indicators like mortality and infection rates are important indicators of quality of care, other indirect factors also play a large role, including determinants of nursing care, interaction time between patients and physicians and the level of training received by healthcare professionals. Third, observed changes in the quality of care may not be explicitly related to the reimbursement mechanism in question, but to other factors, such as competition between hospitals or increased transparency.

This research was subject to several limitations. First, the full text of some articles was not available due to the date of publication; furthermore, several more recent articles available on this topic were published in languages other than English. Second, the majority of the included studies were from high-income countries; therefore, developing countries were not adequately represented, a fact which may limit the generalisability of the results. Third, the number of search terms and databases may not have been sufficiently comprehensive to retrieve all relevant articles on this topic. Finally, most studies retrieved during the literature search reported both positive and adverse outcomes of DRG-based reimbursement mechanisms, with few focusing on administrative challenges. Future research is recommended to evaluate administrative challenges generated by the implementation of DRG-based reimbursement mechanisms, especially with regards to leadership.

Conclusion

Reimbursement mechanisms based on the DRG classification system are gradually replacing fee-for-service systems in many countries. However, the implementation of such mechanisms can face certain challenges, such as a lack of familiarity with the system among physicians, poor medical recordkeeping and issues with data coding. Recommended solutions include revising DRG classifications based on disease complexity, severity and complications and the number and type of illnesses, establishing new DRGs for patients with severe diseases, establishing moderators for vulnerable patient groups and incorporating an increased budget for particularly unusual or complex cases. Moreover, hospitals should implement extensive training at different levels, ensure effective communication with physicians and develop standard protocols for clinical decision-making.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The preliminary version of this research was submitted as part of a PhD thesis in the field of healthcare management at the Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran, in 2017.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

This research was funded with the aid of a grant from the Kerman University of Medical Sciences (grant #96000524).

References

- 1.Witter S, Ensor T, Jowett M, Thompson R. Health Economics for Developing Countries: A practical guide. London, UK: MacMillan Education; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fetter RB. Diagnosis related groups: Understanding hospital performance. Interfaces (Providence) 1991;21:6–26. doi: 10.1287/inte.21.1.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiley M. From the origins of DRGs to their implementation in Europe. In: Busse R, Geissler A, Quentin W, Wiley M, editors. Diagnosis-Related Groups in Europe: Moving towards transparency, efficiency and quality in hospitals. Berkshire, UK: Open University Press; 2011. pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Or Z, Häkkinen U. DRGs and quality: For better or worse? In: Busse R, Geissler A, Quentin W, Wiley M, editors. Diagnosis-Related Groups in Europe: Moving towards transparency, efficiency and quality in hospitals. Berkshire, UK: Open University Press; 2011. pp. 141–55. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quentin W, Scheller-Kreinsen D, Blümel M, Geissler A, Busse R. Hospital payment based on diagnosis-related groups differs in Europe and holds lessons for the United States. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:713–23. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan SS, Serdén L, Geissler A, Van Ineveld M, Redekop K, Heurgren M, et al. DRGs and cost accounting: Which is driving which? In: Busse R, Geissler A, Quentin W, Wiley M, editors. Diagnosis-Related Groups in Europe: Moving towards transparency, efficiency and quality in hospitals. Berkshire, UK: Open University Press; 2011. pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wild V, Carina F, Frouzakis R, Clarinval C, Fässler M, Elger B, et al. Assessing the impact of DRGs on patient care and professional practice in Switzerland (IDoC): A potential model for monitoring and evaluating healthcare reform. Swiss Med Wkly. 2015;145:w14034. doi: 10.4414/smw.2015.14034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langenbrunner JC, Cashin CS, O’Dougherty S. Designing and implementing health care provider payment systems: How-to manuals. Washington DC, USA: World Bank; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fourie C, Biller-Andorno N, Wild V. Systematically evaluating the impact of diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) on health care delivery: A matrix of ethical implications. Health Policy. 2014;115:157–64. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koné I, Maria Zimmermann B, Nordström K, Simone Elger B, Wangmo T. A scoping review of empirical evidence on the impacts of the DRG introduction in Germany and Switzerland. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2019;34:56–70. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kmet LM, Lee RC, Cook LS. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Edmonton, Canada: Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beaumaster S. Ph.D Thesis. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University; Blacksburg, Virginia, USA: 1999. Information technology implementation issues: An analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Busato A, von Below G. The implementation of DRG-based hospital reimbursement in Switzerland: A population-based perspective. Health Res Policy Syst. 2010;8:31. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-8-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogers WH, Draper D, Kahn KL, Keeler EB, Rubenstein LV, Kosecoff J, et al. Quality of care before and after implementation of the DRG-based prospective payment system: A summary of effects. JAMA. 1990;264:1989–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03450150089037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vulgaropulos SP, Lyle CB, Sessions JT. Potential economic impact of applying DRG-based prospective payment categories to inflammatory bowel disease patients. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:577–81. doi: 10.1007/BF01540404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans RL, Halar EM, Hendricks RD, Lawrence KV, Kirk C, Bishop DS. Effects of prospective payment financing on rehabilitation outcome. Int J Rehabil Res. 1990;13:27–35. doi: 10.1097/00004356-199003000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldberg SC, Estes CL. Medicare DRGs and post-hospital care for the elderly: Does out of the hospital mean out of luck? J Appl Gerontol. 1990;9:20–35. doi: 10.1177/073346489000900103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tresch DD, Duthie EH, Jr, Newton M, Bodin B. Coping with diagnosis related groups: The changing role of the nursing home. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:1393–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1988.00380060157028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyles YM. Impact of Medicare diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) on nursing homes in the Portland, Oregon Metropolitan Area. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34:573–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1986.tb05762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurley J, Linz D, Swint E. Assessing the effects of the Medicare prospective payment system on the demand for VA inpatient services: An examination of transfers and discharges of problem patients. Health Serv Res. 1990;25:239–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Menke TJ, Ashton CM, Petersen NJ, Wolinsky FD. Impact of an all-inclusive diagnosis-related group payment system on inpatient utilization. Med Care. 1998;36:1126–37. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199808000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gay EG, Kronenfeld JJ. Regulation, retrenchment--The DRG experience: Problems from changing reimbursement practice. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31:1103–18. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90232-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrisey MA, Sloan FA, Valvona J. Medicare prospective payment and posthospital transfers to subacute care. Med Care. 1988;26:685–98. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sodzi-Tettey S, Aikins M, Awoonor-Williams JK, Agyepong IA. Challenges in provider payment under the Ghana National Health Insurance Scheme: A case study of claims management in two districts. Ghana Med J. 2012;46:189–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roeder N, Rochell B, Juhra C, Mueller M. Empirical comparison of DRG variants using cardiovascular surgery data: Initial results of a project at 18 German hospitals. Aust Health Rev. 2001;24:57–80. doi: 10.1071/ah010057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanderson HF, Storey A, Morris D, McNay RA, Robson MP, Loeb J. Evaluation of diagnosis-related groups in the National Health Service. Community Med. 1989;11:269–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horn SD, Bulkley G, Sharkey PD, Chambers AF, Horn RA, Schramm CJ. Interhospital differences in severity of illness. Problems for prospective payment based on diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) N Engl J Med. 1985;313:20–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198507043130105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Notman M, Howe KR, Rittenberg W, Bridgham R, Holmes MM, Rovner DR. Social policy and professional self-interest: Physician responses to DRGs. Soc Sci Med. 1987;25:1259–67. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bray N, Carter C, Dobson A, Watt JM, Shortell S. An examination of winners and losers under Medicare’s prospective payment system. Health Care Manage Rev. 1994;19:44–55. doi: 10.1097/00004010-199424000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bredenberg PA, Lagoe RJ. Mastectomies for malignancy: A DRG-based hospital utilization analysis. J Surg Oncol. 1987;35:19–23. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930350105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhan C, Elixhauser A, Friedman B, Houchens R, Chiang YP. Modifying DRG-PPS to include only diagnoses present on admission: Financial implications and challenges. Med Care. 2007;45:288–91. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000256969.34461.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wisensale SK, Waldron RJ. Applying the family impact statement to DRGs: Implications for future policymaking. Lifestyles. 1991;12:89–102. doi: 10.1007/BF00987299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muñoz E, Luber J, Birnbaum E, Mulloy K, Cohen JR, Wise L. Hospital costs and resource characteristics for cardiothoracic surgical hospital deaths. Ann Thorac Surg. 1989;47:735–40. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(89)90129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muñoz E, Angus G, Calabro S, Mulloy K, Wise L. DRGs, costs, and outcome for plastic surgical patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;82:116–24. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198882010-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zwanziger J, Davis L, Bamezai A, Hosek SD. Using DRGs to pay for inpatient substance abuse services: An assessment of the CHAMPUS reimbursement system. Med Care. 1991;29:565–77. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199106000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vollertsen RS, Nobrega FT, Michet CJ, Jr, Hanson TJ, Naessens JM. Economic outcome under Medicare prospective payment at a tertiary-care institution: The effects of demographic, clinical, and logistic factors on duration of hospital stay and part A charges for medical back problems (DRG 243) Mayo Clin Proc. 1988;63:583–91. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)64888-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horn SD, Horn RA, Sharkey PD, Beall RJ, Hoff JS, Rosenstein BJ. Misclassification problems in diagnosis-related groups: Cystic fibrosis as an example. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:484–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198602203140805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas F, Clemmer TP, Larsen KG, Menlove RL, Orme JF, Jr, Christison EA. The economic impact of DRG payment policies on air-evacuated trauma patients. J Trauma. 1988;28:446–52. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198804000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pasternak LR, Dean JM, Gioia FR, Rogers MC. Lack of validity of diagnosis-related group payment systems in an intensive care population. J Pediatr. 1986;108:784–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)81069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bull MJ. Influence of diagnosis-related groups on discharge planning, professional practice, and patient care. J Prof Nurs. 1988;4:415–21. doi: 10.1016/s8755-7223(88)80092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joy SA, Yurt RW. An all-payor prospective payment system (PPS) based on diagnosis-related-groups (DRG): Financial impact on reimbursement for trauma care and approaches to minimizing loss. J Trauma. 1990;30:866–73. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199007000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muñoz E, Rosner F, Chalfin D, Goldstein J, Margolis IB, Wise L. Financial risk and hospital cost for elderly patients: Age- and non-age-stratified medical diagnosis related groups. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:909–12. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1988.00380040149021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Munoz E, Barrios E, Johnson H, Goldstein J, Mulloy K, Chalfin D, et al. Pediatric patients, race, and DRG prospective hospital payment. Am J Dis Child. 1989;143:612–16. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1989.02150170114035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Munoz E, Lory M, Josephson J, Goldstein J, Brewster J, Wise L. Pediatric patients, DRG hospital payment, and comorbidities. J Pediatr. 1989;115:545–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(89)80278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muñoz E, Wilkins S, Mallet E, Goldstein J, Sterman H, Wise L. Financial risk and hospital cost for elderly patients in non-age stratified urology DRGs. Urology. 1989;33:445–8. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(89)90048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hensen P, Fürstenberg T, Luger TA, Steinhoff M, Roeder N. Case mix measures and diagnosis-related groups: Opportunities and threats for inpatient dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:582–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patel K. Physicians and DRGs: Hospital management alternatives. Eval Health Prof. 1988;11:487–505. doi: 10.1177/016327878801100405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolfe BL, Detmer DE. Diagnosis related groups (DRGs): Efficiency and/or quality producing? Some evidence from surgical patients. Health Serv Manag Res. 1988;1:19–28. doi: 10.1177/095148488800100103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Turner-Stokes L, Sutch S, Dredge R, Eagar K. International casemix and funding models: Lessons for rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. 2012;26:195–208. doi: 10.1177/0269215511417468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tan SS, Chiarello P, Quentin W. Knee replacement and diagnosis-related groups (DRGs): Patient classification and hospital reimbursement in 11 European countries. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:2548–56. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2374-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lüthi HJ, Widmer PK. DRG system design: A financial risk perspective. Oper Res Health Care. 2017;13–14:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.orhc.2017.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leister JE, Stausberg J. Comparison of cost accounting methods from different DRG systems and their effect on health care quality. Health Policy. 2005;74:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao F. Ph.D Thesis. University of Hong Kong; Pokfulam, Hong Kong.: 2013. Systematic review of the impacts of diagnosis related groups and the challenges of the implementation in Mainland China. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hsia DC, Krushat WM, Fagan AB, Tebbutt JA, Kusserow RP. Accuracy of diagnostic coding for Medicare patients under the prospective-payment system. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:352–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198802113180604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Street A, O’Reilly J, Ward P, Mason A. DRG-based hospital payment and efficiency: Theory, evidence, and challenges. In: Busse R, Geissler A, Quentin W, Wiley M, editors. Diagnosis-Related Groups in Europe: Moving towards transparency, efficiency and quality in hospitals. Berkshire, UK: Open University Press; 2011. pp. 119–40. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cots F, Chiarello P, Salvador X, Castells X, Quentin W. DRG-based hospital payment: Intended and unintended consequences. In: Busse R, Geissler A, Quentin W, Wiley M, editors. Diagnosis-Related Groups in Europe: Moving towards transparency, efficiency and quality in hospitals. Berkshire, UK: Open University Press; 2011. pp. 101–18. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mason A, Street A, Verzulli R. Private sector treatment centres are treating less complex patients than the NHS. J R Soc Med. 2010;103:322–31. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2010.100044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schwartz MH, Tartter PI. Decreased length of stay for patients with colorectal cancer: Implications of DRG use. J Healthc Qual. 1998;20:22–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.1998.tb00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cheng SH, Chen CC, Tsai SL. The impacts of DRG-based payments on health care provider behaviors under a universal coverage system: A population-based study. Health Policy. 2012;107:202–8. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Louis DZ, Yuen EJ, Braga M, Cicchetti A, Rabinowitz C, Laine C, et al. Impact of a DRG-based hospital financing system on quality and outcomes of care in Italy. Health Serv Res. 1999;34:405–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Farrar S, Yi D, Sutton M, Chalkley M, Sussex J, Scott A. Has payment by results affected the way that English hospitals provide care? Difference-in-differences analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b3047. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Castro J, Hector E. Diagnostic related groups (DRGS): Resourceful tools for financial crisis times? Rev Cienc Salud. 2011;9:73–82. [Google Scholar]

- 64.McCall N, Korb J, Petersons A, Moore S. Reforming Medicare payment: Early effects of the 1997 Balanced Budget Act on postacute care. Milbank Q. 2003;81:277–303. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.t01-1-00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gillen R, Tennen H, McKee T. The impact of the inpatient rehabilitation facility prospective payment system on stroke program outcomes. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86:356–63. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31804a7e2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kahn KL, Keeler EB, Sherwood MJ, Rogers WH, Draper D, Bentow SS, et al. Comparing outcomes of care before and after implementation of the DRG-based prospective payment system. JAMA. 1990;264:1984–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03450150084036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lave JR, Frank RG, Taube C, Goldman H, Rupp A. The early effects of Medicare’s prospective payment system on psychiatry. Inquiry. 1988;25:354–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]