Purpose of review

Our aim is to give an overview of the recent literature on psychological treatment for young adults and adults with anorexia nervosa and to discuss the implications of the findings for clinical practice.

Recent findings

Three systematic reviews and meta-analyses have recently been published on psychological treatments for anorexia nervosa. Treatment outcomes are still modest and mainly focus on weight outcome, although outcomes for eating disorder disease and quality of life have also been reported. Adhering to a treatment protocol might lead to faster and better results.

Summary

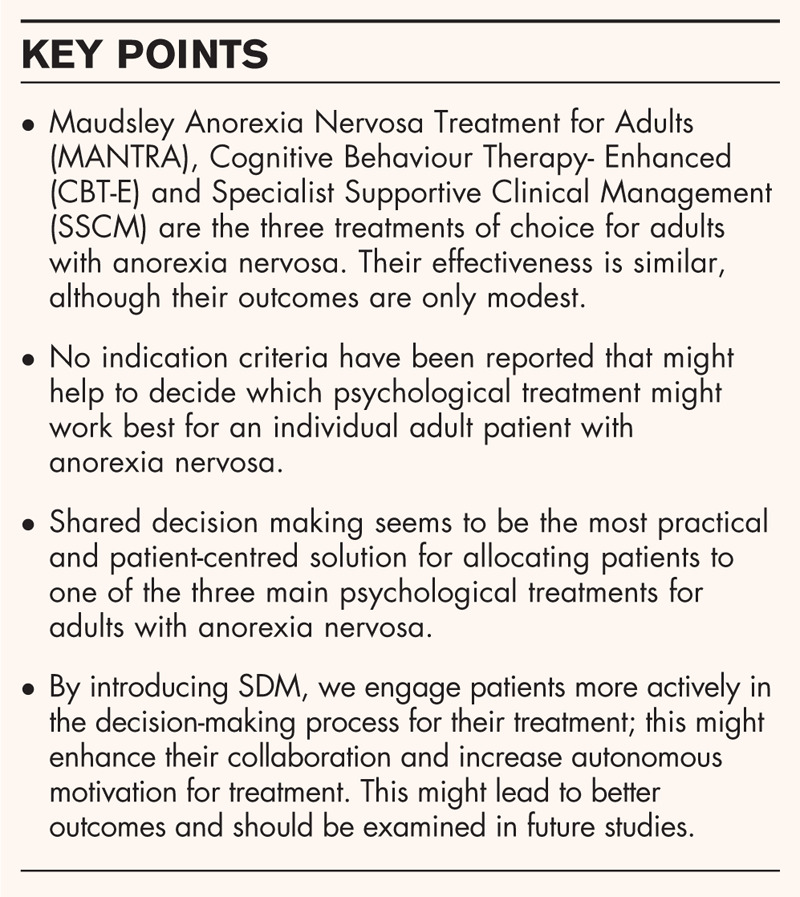

For children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa, the major guidelines recommend a family-based treatment. The treatments of choice for young adults and adults with anorexia nervosa are the Maudsley Anorexia Nervosa Treatment for Adults (MANTRA), Cognitive Behaviour Therapy-Enhanced (CBT-E) and Specialist Supportive Clinical Management (SSCM), but none of these treatments seem to be superior. In search of other ways to improve outcome, shared decision making may be a way to help patients become more involved in their treatment, enhance their motivation and consequently improve the outcome.

Keywords: anorexia nervosa, motivation, psychological treatment, shared decision-making

INTRODUCTION

Anorexia nervosa is a severe psychiatric disorder that affects primarily young women; it starts in adolescence and can continue well into adulthood. The lifetime prevalence of anorexia nervosa in women is up to 2–4% [1–3]. Anorexia nervosa is characterized by restricted food intake, fear of gaining weight and a disturbed body image, leading to a low BMI and a poor prognosis. Even with the best available treatments, recovery rates at 1–2 years posttreatment range from 13 to 50%, while 20–30% of anorexia nervosa patients develop a persistent and sometimes life-long form of the illness, often punctuated by a series of unsuccessful treatments [4▪,5–9]. Moreover, anorexia nervosa has a crude mortality rate of 5% per decade and a standardized mortality ratio of around 6 [1,10,11]. As most first-time patients are adolescents and prognosis is only moderate at best, it is very important to enhance the treatment options available.

Anorexia nervosa is a disorder that covers several domains: physical, neurobiological and psychological aspects all play an important part in its development or persistence. In search of a better understanding and treatment for anorexia nervosa, there have been several interesting developments recently, including more knowledge of its neurobiology, the identification of biomarkers, the translation of this knowledge to (psychological) treatment and the development of new therapeutic targets in children, young people and adults [12,13]. For children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa, all the major guidelines recommend family-based treatment (FBT) and this has been addressed in this journal by Hilbert et al. in 2017 [14] and by Lock in 2018 [15▪]. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) suggests that FBT may be more effective than treatment as usual (TAU) in the short term [16].

This review focuses on the psychological treatment of young adults and adults with anorexia nervosa and we address four main questions: (1) What do recent findings reveal about psychological treatment for anorexia nervosa? (2) What are their implications for clinical practice? (3) Are there any suggestions regarding indication criteria? and (4) Are there any other ways to improve treatment outcome?

Studies on adult patients with anorexia nervosa (including broadly defined anorexia nervosa or atypical anorexia nervosa) and given psychological treatments (aimed at relieving eating disorder disease, such as improving weight gain and quality of life) were identified through searches in Medline, PsychInfo and the Cochrane Library (CDSR).

Box 1.

no caption available

FINDINGS ON ANOREXIA NERVOSA TREATMENTS

In recent years, there have been several publications on randomized control trials (RCTs), systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the efficacy of psychological treatments for anorexia nervosa [17▪▪,18▪,19▪]. These studies focused on treatment interventions, patient characteristics and other factors that might affect outcome. Outcome is determined in two ways: the effect on eating disorder (e.g. weight) and on quality of life. Various types of interventions were studied: psychological treatment [17▪▪], psychotherapy [18▪] and specialist treatment [19▪].

Weight-related outcome

In a meta-analysis on the efficacy of psychological treatments for anorexia nervosa, van den Berg et al.[17▪▪] studied the effects of psychological treatment in general. They reported on patients with anorexia nervosa aged 12 years and older, and they compared psychological treatment (consisting of at least some face-to-face contacts) with a control condition like TAU (e.g. dietary advice, psychoeducational interventions and SSCM) or placebo conditions. Primary outcomes were weight-related: the pooled effect sizes indicated no significant difference in weight gain between the psychological treatment and control condition. In addition, no significant difference was found between treatment and control condition when controlling for sensitivity or quality of the study.

In 2018, Zeeck et al.[18▪] published a systematic review and network-analysis on psychotherapeutic treatment for anorexia nervosa for the revision of the German treatment guidelines for eating disorders. They studied the evidence for psychotherapeutic treatment in anorexia nervosa, compared the effectiveness of the different treatments and determined the extent of weight gain as a result of interventions at different service levels and in different age groups. Psychotherapy was defined as ‘a treatment that uses psychological methods in direct personal contact between a patient and a therapist with the aim of overcoming mental illness’. The 18 studies they included in their review all described at least one treatment that arm included a psychotherapeutic intervention. Network analysis showed there was no significant difference between the treatments in the extent of weight gain and effect sizes.

Murray et al.[19▪] reviewed 35 RCTs on the treatment of anorexia nervosa between 1980 and 2017. They included all specialist treatments (e.g. medication trials, cyclic enteral nutrition, family workshops). They concluded that specialist treatments showed better results than control conditions at improving weight-based symptoms, but none of the specialist treatments outperformed.

Taken together, psychological treatments seem to have a moderately positive effect on weight gain, but none of the treatments seems to be superior.

Eating disorder pathology

Eating disorder pathology is measured in different ways. Van den Berg et al.[17▪▪] included studies with structured interviews or a self-reported measure resulting in a global score or sub-scale scores. Murray et al.[19▪] included studies that reported on psychological symptoms. Neither study found any significant difference in outcome on eating disorder pathology between the treatment and control conditions, nor any effect of the moderators studied.

Quality of life

Van den Berg et al.[17▪▪] also included a meta-analysis of treatment condition on quality of life (measured by a patient-reported perceived QoL or social impairment due to their eating disorder pathology), again no significant effect was found. So far, all psychological therapies for anorexia nervosa lead to a moderate outcome for weight gain, eating disorder pathology and quality of life, with no significant differences found between the treatments. As the type of treatment does not appear to predict outcome, it is necessary to consider what other factors might do so.

Moderating factors

In their meta-analysis, Van den Berg et al.[17▪▪] performed subgroup analyses on several moderators assessed at baseline: BMI, age at illness onset, duration of illness, current age, quality of the study, year of publication, therapy setting, number of treatment sessions given, availability of treatment manual and training of the therapist. They assessed the study quality using the Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias [20]. Studies were judged on risk of bias by computing scores for sequence generation, allocation concealment, incomplete data and selective outcome reporting. The results showed that patients in high-quality studies gained more weight than patients in low-quality studies and that high-quality studies resulted in a better quality of life outcome than lower quality studies. This suggests that adhering to a treatment protocol leads to a better patient outcome. A similar suggestion comes from a recent RCT by De Jong et al.[21▪] comparing CBT-E to TAU in patients with eating disorders. Only a small part of their group consisted of anorexia nervosa patients, so their conclusions cannot simply be generalized to anorexia nervosa, but the results were interesting. The RCT showed that CBT-E and TAU have comparable outcomes for eating disorder recovery and pathology, but that CBT-E reached these levels faster and had a more positive effect on patient self-esteem. So again, one of the implications from these findings is that following a protocol might lead to faster results.

In addition, studies that reported on therapist training showed a significant difference on quality of life outcome compared to studies that did not report training. Again, this suggests that training helps therapists to follow a protocol and not drift away from it. However, clinicians can be reluctant to apply protocol-based treatments in practice, so offering training to clinicians/therapists could help expand their knowledge about the various protocols and underlying evidence, thereby enhancing their motivation to use a protocol and increasing their confidence in it [22,23].

Comparison of MAUDSLEY ANOREXIA NERVOSA TREATMENT FOR ADULTS, COGNITIVE BEHAVIOUR THERAPY-ENHANCED and SPECIALIST SUPPORTIVE CLINICAL MANAGEMENT

Many treatment guidelines [14], such as the Clinical Practice Guidelines of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists [24] and the Dutch Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Eating Disorders [25], recommend MANTRA, CBT-E and SSCM as the treatments of choice for anorexia nervosa. Box 1 describes the Maudsley Anorexia Nervosa Treatment for Adults (MANTRA), Cognitive Behaviour Therapy-Enhanced (CBT-E) and Specialist Supportive Clinical Management (SSCM). The main reason why these protocols are recommended is that they have been studied in several RCTs [26,27,28]. CBT-E was developed as a treatment for different eating disorders and is based on a transdiagnostic model [29]; MANTRA is based on multiple domains and was specifically developed for anorexia nervosa [30]. Interestingly, SSCM was originally a protocol description of TAU in an RCT that compared CBT and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) with TAU [31]. The results surprisingly showed a better outcome for those in the SSCM group than in the IPT group. Thereafter, SSCM was used more often as a description of TAU (see The Maudsley Outpatient Study of Treatments for Anorexia Nervosa and Related Conditions (MOSAIC) study comparing MANTRA with SSCM [27]; and the SWAN study [26]). As the outcome proved to be comparable to the outcome of the experimental conditions, SSCM became one of the recommended treatments. The first RCT that compared all three treatments with protocols was the Strong Without Anorexia Nervosa (SWAN) study [26]. They included 120 patients from three Australian treatment centres, of whom 60% completed treatment and 52.5% completed follow-up assessment. All three therapies led to significant improvements in BMI and eating disorder symptoms. At 12-month follow-up, half of the patients had achieved a healthy weight, and one-third were in remission [26]. Van den Berg et al.[17▪▪] concluded that there is comparable evidence for all three treatments, but they also emphasized the difficulty of achieving a good outcome in the treatment of anorexia nervosa, hence the need for further studies.

It is important to mention here the treatment developments on ‘severe and enduring AN’ (SE-AN). The field of eating disorders lacks a standard definition of SE-AN [4▪], which makes it difficult to determine when a treatment should aim at cure or relief of eating disorder pathology or when SSCM-SE [32], prioritizing quality of life and harm reduction, should be advised.

Box 1 The three main options for treating anorexia nervosa are MANTRA, CBT-E and SSCM

(1) MANTRA: The Maudsley Anorexia Nervosa Treatment for Adults [30] is an evidence-based cognitive-interpersonal treatment of AN. MANTRA incorporates recent findings from the fields of neuropsychological, social cognitive and personality trait research in AN. It includes both intra and interpersonal maintaining factors, and proposes strategies for addressing these. It was developed in cooperation with AN patients. It is modularized with a clear hierarchy of procedures and tailored to the needs of the individual following a workbook. Patient and therapist describe what perpetuating aspects maintain AN and how to intervene. Patients are given an active role in their treatment. Their personal workbook structures the treatment and describes the nine modules and homework assignments. The patient and the practitioner will meet once a week for 50 min in the first phase of treatment. Later on, sessions can be planned less frequently. In addition to paying attention to weight gain and working towards a normal eating pattern, attention is paid to motivation for change and the maintaining factors which are specifically important for the individual patient. These factors are described in ‘a vicious flower’, which can be used to discuss treatment goals. Issues that can be covered are:

-

(a)

A thinking style characterized by inflexibility, excessive attention to detail and fear of making mistakes;

-

(b)

Impairments in the social-emotional domain;

-

(c)

Positive beliefs about how AN helps the person to manage their life;

-

(d)

Unhelpful responses of others.

At the end of treatment, attention is paid to preventing relapses. The number of treatment sessions runs from 20 to 40, depending on severity of underweight.

(2) CBT-E Cognitive Behaviour Therapy- Enhanced [29] is based on a transdiagnostic model for eating disorders. The aim is to identify processes that are operating in the individual patient, thus creating a tailor-made treatment that fits the patient's psychopathology. It is emphasized that it is better to do a few essential aspects well in changing behaviour (by focusing on the most perpetuating behaviours), rather than tackling many things suboptimally. Second, it is based on the idea that people learn by doing (i.e. it is a behaviour therapy). Normalizing the eating pattern and regaining weight are key features from the start of treatment.

Maintaining factors described in the individual model and targeted in treatment can be

-

(a)

overvaluation of body and weight (in which other way may a person appreciate herself?)

-

(b)

overvaluation of control over eating behaviour

-

(c)

dietary restrain

-

(d)

dietary rules

-

(e)

being underweight

-

(f)

changes in eating pattern coherent with event or mood.

Patients are asked to keep a food diary.

In the first weeks, 50-min sessions are scheduled twice a week, thereafter once a week, and at the end of treatment once every two weeks. At the end of treatment, attention is paid to preventing relapses. The number of treatment sessions runs from 20 to 40, depending on severity of underweight.

(3) SSCM (Specialist supportive clinical management [36]) was originally developed by researchers as a control condition to test other psychotherapeutic treatments for AN [31]. They described what therapists should do in their treatment sessions, which turned out to be an effective method. SSCM combines aspects of clinical management and supportive psychotherapy within sessions emphasizing normalization of eating and restoration of weight, specialist psychoeducation and a focus on other symptoms, such as vomiting or overexercising. The remainder of the sessions focus on content dictated by the patient.

Sessions can be weekly or once every two weeks, depending on the patient's needs.

In this treatment, attention is paid to:

-

(a)

Psychoeducation on eating disorders and food

-

(b)

The history of the eating disorder

-

(c)

The causes of the eating disorder

-

(d)

Motivation for change and what might happen if the AN is not treated.

At the end of treatment attention is paid to preventing relapses. The number of treatment sessions runs from 20 to 40, depending on severity of underweight.

BARRIERS TO IMPLEMENTING PSYCHOLOGICAL TREATMENT IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

The recent literature on psychological treatment in anorexia nervosa has some implications for clinical practice, although important questions (as to which treatment is best for whom) remain unanswered. This is partly due to methodological issues that occur in RCTs, systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

One of the issues in interpreting outcome is the nature of the control-condition in many studies. Studies differ in the TAU condition adopted and this makes it difficult to compare outcomes. The meta-analysis of Murray et al.[19▪] showed that a certain treatment can be used as an active condition in one study and a control condition in another. For example, they included a study by Lock et al.[33] who compared a 6-month FBT (active condition) with a 12-month FBT (control condition), and a study by Robin et al.[34] who compared family therapy (active condition) with individual therapy (control condition). So, FBT is included as both an active and a control condition in the meta-analysis. This makes it very difficult to interpret the outcomes of the meta-analyses and might hinder clinicians, patients and families from distinguishing between treatments that have an evidence base and those that do not [35].

Another issue is the development of SSCM, created as a TAU manual. The SSCM protocol is based on a theoretical model of mechanisms of action in anorexia nervosa treatment. It has a set number of sessions, pays attention to eating disorder pathology, focuses on eating pattern and weight gain and includes psychoeducation material. These might be important components that make SSCM an effective treatment. It is a noble, but challenging task to find significant differences when comparing a new treatment protocol to such a control-condition.

What do these recent findings mean for clinical practice? How can we know which treatment is best to use for which patient? In the meta-analyses and reviews described above, none of the psychological treatments outperform on weight gain, eating disorder pathology or quality of life, although several guidelines suggest MANTRA, CBT-E and SSCM as the treatments of choice for anorexia nervosa. They are not recommended because of their individual effectiveness scores, but more because these treatments have standard protocols and have been studied in RCTs [26,27,28]. The reported outcomes suggest that working with trained therapists and with a protocol enhances treatment outcome [17▪▪,36].

MANTRA was developed with the intention of improving psychological treatment for anorexia nervosa using input from various domains, such as neurobiological, neuropsychological, interpersonal and cognitive behavioural domains, but its outcome is still modest. Thus, it is important to shift attention to other aspects that could influence treatment outcome. One interesting development is the ‘staging’ of anorexia nervosa: taking into account the duration of the illness and a patient's psychological well being, and hence differentiating between clinical subtypes of anorexia nervosa and personalizing care to improve treatment outcome [37].

Treatment includes encouraging weight gain and increasing food intake, but as fear of weight gain is an important characteristic of anorexia nervosa, many patients are ambivalent towards complying with any treatment. It is therefore essential to focus on enhancing motivation for treatment to improve outcome.

MOTIVATION FOR TREATMENT AND OUTCOME

In their systematic review, Denison-Day et al.[38] found that interventions targeting motivation were more effective than low-intensity treatment (such as self-help or psychoeducation). However, motivational interventions did not outperform established TAU (such as CBT) that do not exclusively or specifically focus on motivation.

Ryan and Deci's Self-Determination Theory [39] states that conditions supporting autonomy, competence and connection promote motivation for change and treatment engagement. Motivation is subdivided into two types: autonomous and controlled, with autonomous motivation referring to internal motivation to reach an objective, while controlled motivation is driven by external incentives. The experience of autonomy support is associated with increased motivation, which is associated with better outcome [40]. In a study on an additional short, online intervention focused on enhancing motivation to change and the development of a recovery identity in anorexia nervosa patients receiving MANTRA, Cardi et al.[41] found no effect on eating disorder symptoms, psychological well being or work and social adjustment. They did find a higher level of confidence in patient's in their ability to change and alliance with the therapist in the group after the additional intervention.

Following the Self-Determination Theory, Geller et al.[42] studied outcome in relation to the experience of collaborative care in 146 patients with eating disorders admitted to a large Canadian hospital. This was measured with the Session Rating Scale, moderated to ask about experienced collaboration. Experience of collaborative care proved to be associated with positive effects on eating disorder symptoms, psychological functioning, readiness for change, treatment satisfaction and the manner in which mandatory treatment components were delivered. However, the collaboration was measured posttreatment, which means that a positive treatment outcome might have influenced the experienced collaboration, instead of a positive collaboration experience leading to better treatment outcome. Further research is needed to study the relationship between experience of collaboration and treatment outcome.

As we do not have any indication criteria to decide which treatment to adopt for an individual patient, an important step could be to ask patients to choose one of the three treatments. This process is referred to as shared decision making (SDM); it could be done following a protocol and might support autonomous motivation. In the field of psychiatry, little is known about the role of SDM in clinical decision making. However, in somatic healthcare, there is much attention for SDM and research into its effectiveness [43].

SHARED DECISION-MAKING

In situations in which more than one treatment option is available, SDM is the preferred model for engaging patients in the process of deciding which treatment to choose and/or about follow-up [44]. In this process, the key features are to explain that a decision has to be made and to convey that the patient's opinion is crucial in the process, to inform the patient about the different options, to explore the patient's considerations and to support the process of decision-making.

However, little is known about the role of SDM in the treatment of anorexia nervosa or eating disorders more generally [45▪,46]. In 2019, Himmerich et al.[45▪] stated that the treatment of eating disorders could benefit from SDM, as it aims to improve care by encouraging the production and dissemination of information and increasing patient participation. The study offers accurate information on drug treatment in eating disorder by providing an overview of the evidence so far. However, it is important to consider a patient's illness-related impairments in making decisions: patients with an eating disorder may be impaired in the emotional and reward-based components of decision-making [47]. These play an important role, next to intellectual and rational decision-making, in food-related decisions. Medication supporting weight gain leads to intense fear, which will influence decisions on other medication use. Thus, it is important for the clinician to be aware of the patients’ considerations and the role of fears stemming from anorexia nervosa. For anorexia nervosa, SDM might add to better treatment outcomes, but there is no evidence so far to substantiate this.

Recently, more studies have been published about the effect of SDM in the mental health area generally [48–53]. Despite the increasing adoption of the recovery model (which focuses on empowering patients and growing their autonomy) and patients wanting to be part of SDM, many patients with serious mental illnesses are still not being involved in important decisions concerning their treatment [48,54]. Evidence suggests that active participation in treatment decisions leads to a greater likelihood of treatment initiation, reduced symptoms, improved self-esteem, increased service satisfaction, improved patient knowledge, increased confidence in decisions, more active patient involvement, decreased rates of hospitalization (in people with schizophrenia) and improved treatment adherence [48,52].

Difficulties

Barriers to practicing SDM are related to patient factors, clinician factors and systemic factors [49]. Some patients may not feel comfortable in participating in the decision-making process [51]. It is important to note that discussing the patient's role in the SDM process and deferring to the clinician's decision is also a valid option, so the patient may still experience autonomy regarding their choice.

Clinicians who are trained in a specific treatment, or who prefer a specific theoretical orientation can be inclined to advise a treatment according to their own preferences, which results in bias [23]. This process is enhanced by overconfidence in one's own judgement and a lack of regular monitoring of outcomes [52].

In particular, in mental healthcare, there are only few decision aids to support the SDM process, so that more and better tools, such as folders, would be helpful [45▪]. In addition, the process of SDM might take longer than making decisions in a more paternalistic way [49], so this is a factor that has to be considered.

SDM in mental healthcare is a promising approach, but it is still in its infancy. Interest in its use is increasing in daily practice and in research, but firm evidence of its effectiveness is lacking. More research is needed on SDM in mental healthcare, particularly in the field of anorexia nervosa.

CONCLUSION

There are various treatment protocols available for young adults and adults with anorexia nervosa, with guidelines recommending MANTRA, CBT-E or SSCM as the three main treatments of choice. The literature shows that outcomes in RCTs are modest and the effectiveness of these three treatment protocols is similar. However, outcomes do suggest that giving treatment according to a protocol and good training of the therapist/clinician lead to faster and better outcomes. One benefit of offering treatment according to a protocol is that it provides opportunities for further research (on indication criteria) and a more valid comparison of the protocols.

As no criteria have been reported that could help to decide which treatment might work best for whom, it is currently a challenge to allocate patients to a specific treatment. In addition, patients are often ambivalent in their motivation for treatment. One way to overcome these obstacles is to use SDM to choose the treatment option. Patients with mental illnesses are not the only ones to suffer from their illness: the burden on loved ones can also be high. In facing their problems, patients can benefit from the support of friends and family members. Engaging family members, for instance through SDM, is therefore an important aspect in treatment. At the moment, each of the three protocols incorporates the aspect of motivation in their own way: the MANTRA workbook has a specific chapter with several exercises on motivation; CBT-E gives psychoeducation and motivates patients by encouraging early (behavioural) change and experience of the positive effects; and SSCM emphasizes the role of the therapeutic relationship and psychoeducation in enhancing motivation. By introducing SDM, we can engage patients (and their family) more actively in the decision-making process regarding treatment option, and collaboration might be enhanced, hence increasing the patient's autonomous motivation for treatment. This might lead to better outcomes and should be examined in future studies.

For now, SDM seems to be the most practical and patient-centred solution for allocating patients to one of the three recommended treatments.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Smink FR, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Epidemiology, course, and outcome of eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2013; 26:543–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keski-Rahkonen A, Mustelin L. Epidemiology of eating disorders in Europe: prevalence, incidence, comorbidity, course, consequences, and risk factors. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2016; 29:340–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galmiche M, Dechelotte P, Lambert G, Tavolacci MP. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr 2019; 109:1402–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4▪.Wonderlich SA, Bulik CM, Schmidt U, et al. Severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: update and observations about the current clinical reality. Int J Eat Disord 2020. 1–10. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This review article provides an overview of recent diagnostic issues and evidence-informed clinical strategies for treating severe and enduring anorexia nervosa.

- 5.Brockmeyer T, Friederich HC, Schmidt U. Advances in the treatment of anorexia nervosa: a review of established and emerging interventions. Psychol Med 2018; 48:1228–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fichter MM, Quadflieg N, Crosby RD, Koch S. Long-term outcome of anorexia nervosa: results from a large clinical longitudinal study. Int J Eat Disord 2017; 50:1018–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dobrescu SR, Dinkler L, Gillberg C, et al. Anorexia nervosa: 30-year outcome. BJPsych 2019; 216:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eddy KT, Tabri N, Thomas JJ, et al. Recovery from anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa at 22-year follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry 2017; 78:184–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Dempfle A, Egberts KM, et al. Outcome of childhood anorexia nervosa: the results of a five- to ten-year follow-up study. Int J Eat Disord 2018; 51:295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arcelus J, Mitchell AJ, Wales J, Nielsen S. Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders: a meta-analysis of 36 studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011; 68:724–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fichter MM, Quadflieg N. Mortality in eating disorders: results of a large prospective clinical longitudinal study. Int J Eat Disord 2016; 49:391–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bang L, Treasure J, Rø Ø, Joos A. Advancing our understanding of the neurobiology of anorexia nervosa: translation into treatment. J Eat Disord 2017; 5:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinglass JE, Dalck M, Foerde K. The promise of neurobiological research in anorexia nervosa. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2019; 32:491–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hilbert A, Hoek HW, Schmidt R. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for eating disorders: international comparison. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2017; 30:423–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15▪.Lock J. Family therapy for eating disorders in youth: current confusions, advances, and new directions. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2018; 31:431–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; An important article on developments in family therapy for eating disorders: the primary advised therapy for youth with eating disorders.

- 16.Fisher CA, Skocic S, Rutherford KA, Hetrick SE. Family therapy approaches for anorexia nervosa. CDSR 2019; 5: Art. No.: CD004780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17▪▪.van den Berg E, Houtzager L, Vos de J, et al. Meta-analysis on the efficacy of psychological treatments for anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2019; 27:331–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A recent and thorough meta-analysis, which covers the field of psychological treatment for anorexia nervosa. The meta-analysis includes weight related outcome, eating disorder symptoms, quality of life and a broad range of moderators.

- 18▪.Zeeck A, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Friederich HC, et al. Psychotherapeutic treatment for anorexia nervosa: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry 2018; 9:158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A systematic review and interesting network meta-analysis of psychotherapeutic treatment for anorexia nervosa.

- 19▪.Murray SB, Quintana DS, Loeb KL, et al. Treatment outcomes for anorexia nervosa: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychol Med 2019; 49:535–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; An interesting article because it includes 35 RCTs on anorexia nervosa, although the diversity of the RCTs makes it a difficult study to interpret.

- 20.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011; 343:889–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21▪.de Jong M, Spinhoven P, Korrelboom K, et al. Effectiveness of enhanced cognitive behavior therapy for eating disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Eat Disord 2020; 53:447–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This recent large RCT showed that CBT-E and TAU have comparable outcomes for eating disorder recovery and disease, but that CBT-E reached these levels faster and had a more positive effect on patient self-esteem.

- 22.Waller G. Evidence-based treatment and therapist drift. Behav Res Ther 2009; 47:119–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lilienfeld SO, Ritschel LA, Lynn SJ, et al. Why many clinical psychologists are resistant to evidence-based practice: root causes and constructive remedies. Clin Psychol Rev 2013; 33:883–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haye P, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2014; 48:977–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dutch Foundation for Quality Development in Mental Healthcare Practice guideline for the treatment of eating disorders (Zorgstandaard Eetstoornissen). Utrecht, The Netherlands: Netwerk Kwaliteitsontwikkeling GGz; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Byrne S, Wade T, Hay P, et al. A randomised controlled trial of three psychological treatments for anorexia nervosa. Psychol Med 2017; 47:2823–2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt U, Magill N, Renwick, et al. The Maudsley outpatient study of treatments for anorexia nervosa and related conditions (MOSAIC): comparison of the Maudsley model of anorexia nervosa treatment for adults (MANTRA) with specialist supportive clinical management (SSCM) in outpatients with broadly defined anorexia nervosa: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2015; 83:796–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zipfel S, Wild B, Groß G, et al. Focal psychodynamic therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, and optimised treatment as usual in outpatients with anorexia nervosa (ANTOP study): randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014; 383:127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: The Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt U, Wade TD, Treasure J. The Maudsley Model of Anorexia Nervosa Treatment for Adults (MANTRA): development, key features and preliminary evidence. J Cogn Psychother 2014; 28:48–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McIntosh VVW, Jordan J, Carter FA, et al. Three psychotherapies for anorexia nervosa: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:741–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Touyz S, Le Grange D, Lacey H, Hay P. Managing severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: a clinician's guide. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lock J, Agras WS, Bryson S, Kraemer HC. A comparison of short and long-term family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa. J Am Acad Child Psy 2005; 44:632–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robin AL, Siegel PT, Moye AW, et al. A controlled comparison of family versus individual therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. J Am Acad Child 1999; 38:1482–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lock J, Kraemer HC, Jo B, Couturier J. When meta-analyses get it wrong: response to ‘treatment outcomes for anorexia nervosa: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials’. Psychol Med 2019; 49:697–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McIntosh V, Jordan J, Luty SE, et al. Specialist supportive clinical management for anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 2006; 39:625–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ambwani S, Cardi V, Albano G, et al. A multicenter audit of outpatient case of adult anorexia nervosa: symptom trajectory, service use, and evidence in support of ‘early stage’ versus ‘severe and enduring’ classification. Int J Eat Disord 2020; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Denison-Day J, Appleton KM, Newell C, et al. Improving motivation to change amongst individuals with eating disorders: a systematic review. Int J Eat Disord 2018; 51:1033–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well being. Am Psychol 2000; 55:68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steiger H, Sansfacon J, Thaler L, et al. Autonomy support and autonomous motivation in the outpatient treatment of adults with an eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 2017; 50:1058–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cardi V, Albano G, Ambwani S, et al. A randomised clinical trial to evaluate the acceptability and efficacy of an early phase, online, guided augmentation of outpatient care for adults with anorexia nervosa. Psychol Med 2019. 1–12. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geller J, Maiolino N, Samson L, Srikameswaran S. Is experiencing care as collaborative associated with enhanced outcomes in inpatient eating disorders treatment? Eating Disord 2019; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin GA, Fagerlin A. Shared decision making: state of the science. Circ Cardiovasc Qual 2014; 7:328–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH, Haes de JCJM. Shared decision making: concepts, evidence, and practice. Pat Educ Couns 2015; 98:1172–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45▪.Himmerich H, Bentley J, Lichtblau N, et al. Facets of shared decision-making on drug treatment for adults with an eating disorder. Int Rev Psychiatry 2019; 31:332–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; An important article that reflects on SDM and drug treatment for eating disorders.

- 46.Strand M, Bulik CM, Hausswolff-Juhlin von Y, Gustafsson SA. Self-admission to inpatient treatment for patients with anorexia nervosa: the patient's perspective. Int J Eat Disord 2017; 50:398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Elzakkers IFFM, Danner UN, Hoek HW, Elburg van AA. Mental capacity to consent to treatment in anorexia nervosa: explorative study. BJPsych Open 2016; 2:147–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alguera-Lara V, Dowsey MM, Ride J, et al. Shared decision making in mental health: the importance for current clinical practice. Australas Psychiatry 2017; 25:578–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang C, Plummer V, Lam L, Cross W. Perceptions of shared decision-making in severe mental illness: an integrative review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2020; 27:103–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luciano M, Sampogna G, Del Vecchio V, et al. When does shared decision making is adopted in psychiatric clinical practice? Results from a European multicentric study. Eur Arch Psy Clin Neurosci 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morán-Sánchez I, Gómez-Vallés P, Bernal-López MA, Pérez-Cárceles MD. 2019 Shared decision-making in outpatients with mental disorders: patients’ preferences and associated factors. J Eval Clin Pract 2019; 25:1200–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trusty WT, Penix EA, Dimmick AA, Swift JK. Shared decision-making in mental and behavioural health interventions. J Eval Clin Pract 2019; 25:1210–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thomsen CT, Benros ME, Maltesen T, et al. Patient-controlled hospital admission for patients with severe mental disorders: a nationwide prospective multicentre study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2018; 137:355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rodenburg-Vandenbussche S, Carlier I, Vliet van I, et al. Patients’ and clinicians’ perspectives on shared decision-making regarding treatment decisions for depression, anxiety disorders, and obsessive-compulsive disorder in specialized psychiatric care. J Eval Clin Pract 2019; 26:645–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]