Abstract

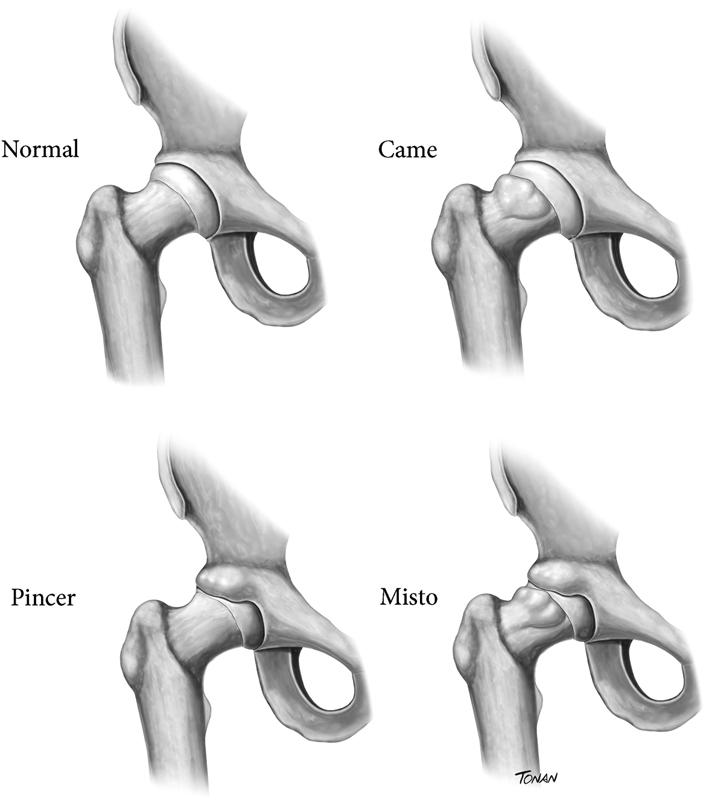

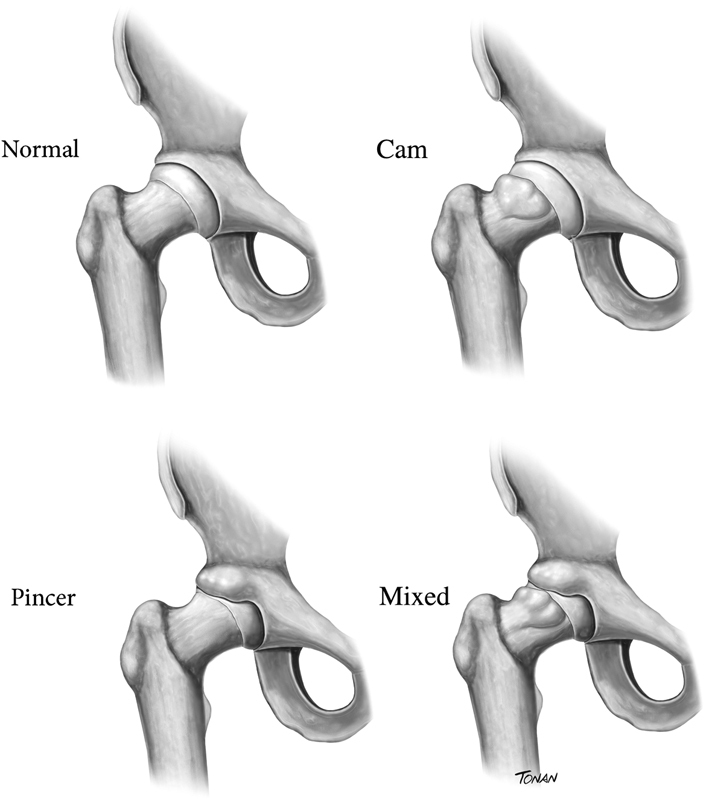

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is an important cause of hip pain, and the main etiology of hip osteoarthritis in the young population. Femoroacetabular impingement is characterized by subtle alterations in the anatomy of the acetabulum and proximal femur, which can lead to labrum tearing. The acetabular labrum is essential to the stability of the hip joint. Three types of FAI were described: cam (anespherical femoral head), pincer (acetabular overcoverage) and mixed (characteristics of both cam and pincer). The etiology of FAI is related to genetic and environmental characteristics. Knowledge of this condition is essential to adequately treat patients presenting with hip pain.

Keywords: hip, femoroacetabular impingement, acetabular labrum, sports medicine, hip arthroscopy

Introduction

Hip surgery has come a long way in the last 2 decades. Several new conditions affecting the hip joint have been described, as well as new treatment techniques. Among these conditions, femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) and acetabular labrum injury warrant highlight. Femoroacetabular impingement is a major cause of hip pain in young people, especially those practicing sports. In addition, FAI is the leading cause of hip osteoarthritis (OA) in the young population.

Femoroacetabular impingement and labrum injury diagnoses are increasingly common in orthopedics offices, and hip arthroscopy is among the fastest growing orthopedic procedures. As such, it is essential that orthopedists are familiar with this condition and understand its pathophysiology.

Background

In 1936, Smith-Petersen 1 was the first to describe a femoral and acetabular osteotomy for hip pain treatment. In this article, the author asks: “what is the origin of the patient's pain?”, and answers: “impingement between femoral neck and the anterior acetabular wall”. The surgical technique consisted of hip joint exposure through a Smith-Petersen approach. Part of the anterior acetabular wall was resected along with a portion of the femoral head-neck junction. Although this technique is similar to the one described decades later for FAI surgical treatment, it was used in hips with established arthrosis.

In 1968, Carlioz et al., 2 were the first to use the term cam to describe femoral deformity, in this particular case associated with an epiphysiolisthesis sequelae. In 1975, Stulberg et al. 3 described a pistol grip deformity, observed in 40% of hip OA patients.

Years later, in 1991, Klaue et al., 4 described the acetabular rim syndrome, in which hip dysplasia causes an acetabular labrum lesion that would be a precursor of OA. Reynolds et al., 5 in 1999, demonstrated the association between acetabular retroversion and hip pain, whereas Myers et al., 6 in the same year, reported five patients with pain after periacetabular osteotomy due to residual impingement.

All this knowledge accumulated over decades culminated in the pivotal 2003 article, in which Ganz et al., 7 established the concepts of modern FAI. The authors suggested that mild femoral and acetabular deformities associated with movement are responsible for the development of OA, proposed a FAI classification, and described its clinical and radiographic findings, as well as its treatment by surgical hip dislocation.

Pathophysiology

The acetabular labrum is a triangular fibrocartilaginous structure located around the acetabular rim. It is interrupted inferiorly by the transverse ligament. The labrum has been the focus of several recent articles demonstrating its role in joint stability. The labrum plays an important role at the suction seal, which is responsible for maintaining negative pressure within the joint. Crawford et al., 8 demonstrated that 43% less force is required to distract the hip after joint ventilation (by introducing a needle between the labrum and acetabulum) compared with the intact state. In addition, after performing a 3 mm acetabular lesion, 60% less force is required to create the same distraction. Finite element analyses and biomechanical studies in cadavers have shown that acetabular labrum resection increases the rate of cartilage consolidation. 9 10 Consolidation is defined as the cartilage layer compression when load is applied. These studies reinforce the idea of the acetabular labrum sealing function, which maintains a fluid film between the acetabulum and the femoral head, decreasing intra-articular solid-solid pressure.

The acetabular labrum has great tensile strength. Its tensile modulus, a measure of its stiffness and tensile strength to stretching, is six times greater compared to rubber. 11 This feature is also important for its function as a hip suction seal. On the other hand, the acetabular labrum has no important role in supporting the axial load of the hip. The labrum supports only 1 to 2% of normal joint load, rising to 4 to 11% in dysplastic hips. 11 12 13

Hip capsule-ligament structures are also essential for joint stability. Myers et al., 14 demonstrated that the iliofemoral ligament plays an important role in limiting the external rotation and anterior translation of the femur, and that the acetabular labrum has a secondary stabilizing function during such movements. Iliofemoral ligament section increased the external hip rotation (from 41.5° to 54.4°), while the acetabular labrum section did not increase rotation significantly (45.6°). Another important finding of this study was that ligament and labrum repair restored initial rotation. The authors suggested that a capsulotomy performed during hip arthroscopy should be repaired at the end of the procedure.

Classification

Femoroacetabular impingement is divided in three types: cam, pincer and mixed ( Figure 1 ). 7 15 Pincer-type FAI is caused by an acetabular cavity change. The normal acetabulum is anteverted and it covers the femoral head within a narrow normality range. Both the lack of coverage associated with dysplasia and the excess coverage observed in pincer-type FAI cause joint pain and degeneration. Pincer-type FAI presents an acetabular overlay relative to the femoral head. This over-coverage may be focal in acetabular retroversion or global in cases of increased center-edge angle. Pincer labrum injury results from the labrum being crushed between the femoral neck and the acetabular rim. As such, the labrum in pincer-type FAI is degenerated and it can present intrasubstantial cysts. Pincer-type FAI may also be accompanied by a contre-coup injury. In this case, the femoral head is posteriorly levered by the prominent anterior acetabular wall, damaging the posterior acetabular cartilage.

Fig. 1.

Femoroacetabular impingement types.

Cam-type FAI is caused by a femoral abnormality. For the hip to move without conflict, the femoral head must be a perfect sphere. Cam-type deformity occurs at the transition between the femoral head and neck, resulting in local loss of sphericity. The acetabular labrum damage caused by this deformity is located at the transition between the acetabular cartilage and the labrum. As the aspheric femoral head enters the acetabular cavity, the acetabular cartilage is avulsed from the labrum due to a shear force between the head and the cartilage. As such, carpet-like acetabular cartilage injury (initially healthy-looking cartilage but detached from the subchondral bone) are common in cam-type FAI. In early lesions, the labrum tissue remains healthy.

The third FAI type is referred to as mixed since it presents an association of pincer and cam changes. Mixed FAI is the most common type, with an incidence of up to 77%. 16 However, even in mixed-type FAI, the patient usually presents more predominant characteristics of cam- or pincer-type morphologies.

Seldes et al., 17 described a histological classification for acetabular labrum injury. Type 1 consists in acetabular cartilage labrum detachment at the transition between fibrocartilaginous labrum and acetabular hyaline cartilage. In contrast, type 2 presents one or more cleavage plans within the acetabular substance. Type 2 is related to endochondral labrum ossification. A later article modified the Seldes classification and included a type 3 lesion, with mixed features, associating labrum detachment and labrum substance cleavage plans. 18

Etiology

The development of FAI is influenced by genetic and environmental features. Pollard et al., 19 studied siblings of FAI patients. Siblings of cam- or pincer-type FAI patients presented a 2.8 and 2.0 times higher relative risk of having the same deformity, respectively. In the sibling group, the presence of grade 2 hip OA according to the Kellgren and Lawrence classification was significantly higher compared with the control group (11 versus. 0). The authors concluded that there is a genetic influence on FAI development. Sekimoto et al., 20 studied the association between genetic polymorphism and acetabular over-coverage and demonstrated that genetic variations are significantly associated with acetabular coverage.

Cam-type deformity development is related to a lateral extension of the growth physis. 21 Intense participation in sports activities during late adolescence, near epiphyseal closure, may be related to cam-type FAI development secondary to a mechanical stress on the femoral head growth plate. Murray et al., 22 in 1971, suggested an association between sports activity in adolescence and hip OA in adulthood. The authors questioned whether idiopathic hip OA had an undefined etiology or resulted from minor changes at the hip joint. An interesting study evaluated the presence of cam deformity in adolescent basketball players compared to non-athlete controls. 23 The average alpha angle was 47.4° in control subjects and 60.5° in athletes. The differences were even more pronounced in femurs with growth plates already closed. The authors interpreted this result as a suggestion that cam-type FAI development occurs during epiphyseal closure. A similar survey evaluated adolescent pre-professional soccer players. 24 A total of 63 athletes (average age, 14.43 years old) were followed for at least 2 years. A significant increase in alpha angle was observed. Growth plate extension was also associated with the alpha angle. The authors also concluded that cam-type deformity develops during skeletal maturation and stabilizes after epiphyseal closure. A recent literature review concluded that adolescent male athletes involved in ice hockey, basketball and soccer, training at least three times a week, have a higher risk of developing FAI. 25

Epidemiology

The Warwick consensus suggests the term FAI syndrome. 26 The diagnosis of this syndrome is based on clinical symptoms, changes at the physical examination, and imaging findings. This consideration is important because several epidemiological studies evaluate the presence of FAI in asymptomatic controls. The prevalence of FAI-like changes in controls is important, but it is worth noting that these volunteers do not have FAI syndrome because they do not present hip symptomatology.

A systematic review evaluating the prevalence of FAI-like deformities in volunteers included 26 studies and more than 2,000 people (57.2% men and 42.8% women). 27 The average alpha angle was 54.1°, and cam deformity prevalence was 37%; however, there was a large variation between studies (prevalence range, 7 to 100%). A major difference was also noted when athletes and non-athletes were compared. While 54.8% of athletes had cam deformity, only 23.1% of non-athletes presented it. The prevalence of pincer-type deformity was 67%. Seven studies evaluated the presence of acetabular labrum lesion on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), revealing a prevalence of 68.1%.

The incidence of FAI and symptomatic labrum injury in athletes is not known. Hip injuries are estimated to account for 5 to 6% of sports injuries. 28 29 In North American college sports, a rate of 53.06 injuries per 100,000 athlete-exposures has been reported .30 However, these studies included muscle injuries among hip injury epidemiology, with no joint injury distinction. A study of football injuries from 1997 to 2006 found a 3.1% incidence of hip-related injuries. 31 Only 5% of these injuries resulted from joint issues. Another study with first-division college football athletes evaluated the incidence of surgical procedures over a 10-year period (from 2004 to 2014). 32 There were 254 surgical procedures, of which 15 surgeries (5.9%) were arthroscopic acetabular labrum repairs. It is noteworthy that the last decade saw a great increase in FAI knowledge and the spread of such understanding among sports physicians. Therefore, this incidence is likely to be higher now.

Femoroacetabular Impingement and Hip Osteoarthrosis

Hip OA affects 3% of the population > 30 years old in the United States, where more than 200,000 hip arthroplasties procedures are performed each year. 33 Understanding the relationship of FAI with hip OA is one of the most important aspects in counseling patients and defining treatment strategies.

Agricola et al., 34 conducted a prospective study, known as the CHECK study, in which > 1,000 patients were followed for 5 years. A pelvic radiograph for alpha angle measurement and a physical examination were performed. The presence of a moderate cam-type deformity (alpha angle > 60°) resulted in an odds ratio (OR) for OA development of 3.67, while the presence of a severe cam-type deformity (alpha angle > 83°) resulted in an OR for OA development of 9.66. The combination of severe cam-type deformity with decreased internal rotation (< 20°) had a positive predictive value of 52.6% for the development of severe hip OA at the end of the follow-up period. Another study with 1,003 female patients compared hip radiographs taken with a 20-year interval. 35 Cam-type deformity (defined as alpha angle > 65°) was associated with the development of radiographic OA. For each degree increase in alpha angle, there was a 5% increase in the risk of radiographic OA development and a 4% increase in the risk of performing total hip arthroplasty.

The relationship of pincer-type FAI to OA development is less clear. Another study from the CHECK group found no relationship between center-edge angle > 40° and OA development. 36 Gosvig et al., 37 found a 2.4 times greater risk of developing OA in patients with center-edge angle > 45°. Remember that the increased center-edge angle reflects a global acetabular over-coverage. Specific studies on acetabular retroversion (focal overlay) suggest a possible correlation with hip OA. Kim et al., 38 found a correlation between decreased joint space and acetabular retroversion in a study with computed tomography (CT) of patients examined for non-orthopedic reasons. Giori et al., 39 conducted a case-control study comparing radiographs of OA patients submitted to total hip replacement and asymptomatic controls. Acetabular retroversion was observed in 20% of patients and in 5% of control subjects. The authors concluded that there is a relationship between acetabular retroversion and hip OA.

Studying the relationship between FAI and hip OA is a growing field that requires further research. In the clinical practice, we note that some patients with FAI have a rapid evolution to OA, while others have a very slow evolution. Understanding which patients are at higher risk for progression and which patients are less susceptible will be a major advance to improve FAI treatment.

Agradecimentos

Os autores gostariam de agradecer Rodrigo Tonan pela ilustração médica deste artigo.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rodrigo Tonan for the medical illustration of the present paper.

Conflito de Interesses Os autores declaram não haver conflito de interesses.

Considerações Finais

O IFA é uma síndrome caracterizada por dor no quadril associada a alterações sutis na anatomia da articulação coxo-femoral. O IFA é uma causa importante de lesão do lábio acetabular, que é uma estrutura essencial na biomecânica do quadril. O conhecimento desta doença é de suma importância para o ortopedista que trata pacientes com dor no quadril.

Final Remarks

Femoroacetabular impingement is a syndrome characterized by hip pain associated with subtle changes in hip joint anatomy. Femoroacetabular impingement is a major cause of damage to the acetabular labrum, an essential structure in hip biomechanics. Knowledge of this disease is of paramount importance to orthopedists treating patients with hip pain.

Referências

- 1.Smith-Petersen M N. Treatment of malum coxae senilis, old slipped upper femoral epiphysis, intrapelvic protrusion of the acetabulum, and coxa plana by means of acetabuloplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1936;18:869–880. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0670-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlioz H, Pous J G, Rey J C. [Upper femoral epiphysiolysis] Rev Chir Orthop Repar Appar Mot. 1968;54(05):387–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stulberg S D, Cordell L D, Harris W H, Ramsey P L, MacEwan G D.Unrecognized childhood hip disease: a major cause of idiopathic osteoarthritis of the hipIn: The Hip. Proceedings of The Third Meeting of the Hip Society.St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby; 1975

- 4.Klaue K, Durnin C W, Ganz R. The acetabular rim syndrome. A clinical presentation of dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(03):423–429. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B3.1670443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reynolds D, Lucas J, Klaue K. Retroversion of the acetabulum. A cause of hip pain. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81(02):281–288. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.81b2.8291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myers S R, Eijer H, Ganz R. Anterior femoroacetabular impingement after periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;(363):93–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganz R, Parvizi J, Beck M, Leunig M, Nötzli H, Siebenrock K A. Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(417):112–120. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000096804.78689.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crawford M J, Dy C J, Alexander J W. The 2007 Frank Stinchfield Award. The biomechanics of the hip labrum and the stability of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;465(465):16–22. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31815b181f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferguson S J, Bryant J T, Ganz R, Ito K. The acetabular labrum seal: a poroelastic finite element model. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2000;15(06):463–468. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(99)00099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferguson S J, Bryant J T, Ganz R, Ito K. An in vitro investigation of the acetabular labral seal in hip joint mechanics. J Biomech. 2003;36(02):171–178. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00365-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bsat S, Frei H, Beaulé P E. The acetabular labrum: a review of its function. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B(06):730–735. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.98B6.37099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Konrath G A, Hamel A J, Olson S A, Bay B, Sharkey N A. The role of the acetabular labrum and the transverse acetabular ligament in load transmission in the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(12):1781–1788. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199812000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henak C R, Ellis B J, Harris M D, Anderson A E, Peters C L, Weiss J A. Role of the acetabular labrum in load support across the hip joint. J Biomech. 2011;44(12):2201–2206. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myers C A, Register B C, Lertwanich P.Role of the acetabular labrum and the iliofemoral ligament in hip stability: an in vitro biplane fluoroscopy study Am J Sports Med 201139(Suppl):85S–91S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavigne M, Parvizi J, Beck M, Siebenrock K A, Ganz R, Leunig M. Anterior femoroacetabular impingement: part I. Techniques of joint preserving surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(418):61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Philippon M J, Briggs K K, Yen Y M, Kuppersmith D A. Outcomes following hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement with associated chondrolabral dysfunction: minimum two-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(01):16–23. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B1.21329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seldes R M, Tan V, Hunt J, Katz M, Winiarsky R, Fitzgerald R H., Jr Anatomy, histologic features, and vascularity of the adult acetabular labrum. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(382):232–240. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200101000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ejnisman L, Domb B G, Souza F, Junqueira C, Vicente J RN, Croci A T. Are femoroacetabular impingement tomographic angles associated with the histological assessment of labral tears? A cadaveric study. PLoS One. 2018;13(06):e0199352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollard T C, Villar R N, Norton M R. Genetic influences in the aetiology of femoroacetabular impingement: a sibling study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(02):209–216. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B2.22850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sekimoto T, Kurogi S, Funamoto T. Possible association of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the 3′ untranslated region of HOXB9 with acetabular overcoverage. Bone Joint Res. 2015;4(04):50–55. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.44.2000349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siebenrock K A, Wahab K H, Werlen S, Kalhor M, Leunig M, Ganz R. Abnormal extension of the femoral head epiphysis as a cause of cam impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(418):54–60. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200401000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray R O, Duncan C. Athletic activity in adolescence as an etiological factor in degenerative hip disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1971;53(03):406–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siebenrock K A, Ferner F, Noble P C, Santore R F, Werlen S, Mamisch T C. The cam-type deformity of the proximal femur arises in childhood in response to vigorous sporting activity. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(11):3229–3240. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1945-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agricola R, Heijboer M P, Ginai A Z. A cam deformity is gradually acquired during skeletal maturation in adolescent and young male soccer players: a prospective study with minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(04):798–806. doi: 10.1177/0363546514524364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Silva V, Swain M, Broderick C, McKay D. Does high level youth sports participation increase the risk of femoroacetabular impingement? A review of the current literature. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2016;14(01):16. doi: 10.1186/s12969-016-0077-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffin D R, Dickenson E J, O'Donnell J. The Warwick Agreement on femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAI syndrome): an international consensus statement. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(19):1169–1176. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frank J M, Harris J D, Erickson B J. Prevalence of Femoroacetabular Impingement Imaging Findings in Asymptomatic Volunteers: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(06):1199–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keogh M J, Batt M E. A review of femoroacetabular impingement in athletes. Sports Med. 2008;38(10):863–878. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200838100-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prather H, Colorado B, Hunt D. Managing hip pain in the athlete. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2014;25(04):789–812. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kerbel Y E, Smith C M, Prodromo J P, Nzeogu M I, Mulcahey M K. Epidemiology of Hip and Groin Injuries in Collegiate Athletes in the United States. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(05):2.325967118771676E15. doi: 10.1177/2325967118771676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feeley B T, Powell J W, Muller M S, Barnes R P, Warren R F, Kelly B T. Hip injuries and labral tears in the national football league. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(11):2187–2195. doi: 10.1177/0363546508319898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mehran N, Photopoulos C D, Narvy S J, Romano R, Gamradt S C, Tibone J E. Epidemiology of Operative Procedures in an NCAA Division I Football Team Over 10 Seasons. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4(07):2.32596711665753E15. doi: 10.1177/2325967116657530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nho S J, Kymes S M, Callaghan J J, Felson D T. The burden of hip osteoarthritis in the United States: epidemiologic and economic considerations. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21 01:S1–S6. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-21-07-S1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agricola R, Heijboer M P, Bierma-Zeinstra S M, Verhaar J A, Weinans H, Waarsing J H. Cam impingement causes osteoarthritis of the hip: a nationwide prospective cohort study (CHECK) Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(06):918–923. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas G E, Palmer A J, Batra R N. Subclinical deformities of the hip are significant predictors of radiographic osteoarthritis and joint replacement in women. A 20 year longitudinal cohort study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(10):1504–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agricola R, Heijboer M P, Roze R H. Pincer deformity does not lead to osteoarthritis of the hip whereas acetabular dysplasia does: acetabular coverage and development of osteoarthritis in a nationwide prospective cohort study (CHECK) Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21(10):1514–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gosvig K K, Jacobsen S, Sonne-Holm S, Palm H, Troelsen A. Prevalence of malformations of the hip joint and their relationship to sex, groin pain, and risk of osteoarthritis: a population-based survey. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(05):1162–1169. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim W Y, Hutchinson C E, Andrew J G, Allen P D. The relationship between acetabular retroversion and osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(06):727–729. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B6.17430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giori N J, Trousdale R T. Acetabular retroversion is associated with osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(417):263–269. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000093014.90435.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]