Abstract

The clinical diagnosis of femoral acetabular impingement (FAI) continues to evolve as the understanding of normal and pathological hips progresses. Femoral acetabular impingement is currently defined as a syndrome in which the diagnosis consists of the combination of a previously-obtained comprehensive clinical history, followed by a consistent and standardized physical examination with specific orthopedic maneuvers. Additionally, radiographic and tomographic examinations are used for the morphological evaluation of the hip, and to ascertain the existence of sequelae of childhood hip diseases and the presence of osteoarthritis. The understanding of the femoral and acetabular morphologies and versions associated with images of labral and osteochondral lesions obtained through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contributes to the confirmation of this syndrome in symptomatic patients, and helps in the exclusion of differential diagnoses such as iliopsoas tendon snaps, subspine impingement, ischiofemoral impingement, and other hip joint pathologies.

Keywords: diagnosis, hip, radiography, femoroacetabular impingement

Introduction

Clinical Features

The clinical diagnosis of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) continues to evolve with the progression of the understanding of normal and pathological hips. Asymptomatic patients often have abnormal hip radiographic findings whose significance is determined by clinical history and physical examination. An organized and competent clinical examination will lead to an accurate diagnosis of FAI, considering its biomechanical aspects and differential diagnoses. A structured and thorough examination is critical in the investigation of symptomatic hips. 1

History

Clinical history is not only important to define the diagnosis of FAI, but also to choose the most appropriate therapeutic option for each patient. 2 A comprehensive history should be obtained prior to the physical examination of the hip.

Pain is the main reason that leads FAI patients to seek medical assistance. Reiman et al. (2014; 2015) 3 4 observed that pain in the anterior groin area that worsens with prolonged standing up, sitting down or walking may be indicative of joint changes (FAI or labrum injury) with sensitivity ranging from 96% to 100%. They also observed that acute pain associated with cracking and bump is related to osteochondral lesions, FAI and labral lesions, with 85% specificity and 100% sensitivity.

Pain related to specific positions, especially medial rotation or sports activities requiring rotation associated with pivoting or flexion, is also indicative of intra-articular conditions. 5

Other frequent complaints include reduced hip mobility, mechanical symptoms, bumpiness and locking; these last three complaints are related to chondrolabral transition injuries.

The main complaint is documented, including the date of onset and the presence or absence of trauma. Pain should be characterized according to location, intensity, and factors that worsen or relieve it.

The “C” sign, characteristic of patients with intra-articular issues, is often present: the patient places the hand in “C” above the greater trochanter, with the thumb posterior to the trochanter and the fingers at the inguinal region. 6

Lateral hip and buttock pain may also accompany previous symptoms, including exacerbating mechanical symptoms. 7

Referred knee pain is a frequent complaint in hip disease. Low back, sacroiliac and pubic pain may result from mechanical overload.

The use of scores for pain and hip function stratification is important, not only for research, but also to treat each patient. These scores provide a measure of pain and limitations caused by hip disease, guiding treatment and serving as a basis for the assessment of the evolution. 8 9 10 In addition, scores provide the surgeon with a source for self-assessment to improve surgical indications and outcomes.

Differential diagnoses include iliopsoas muscle tendon snapping, iliotibial tract protrusion, subspine impingement, and ischiofemoral impingement.

Physical Exam

Standardization increases the reliability of physical exams .11 The most efficient order for physical examination of the hip begins with the patient standing up, sitting down, and following from the supine to the lateral and ventral positions. 1

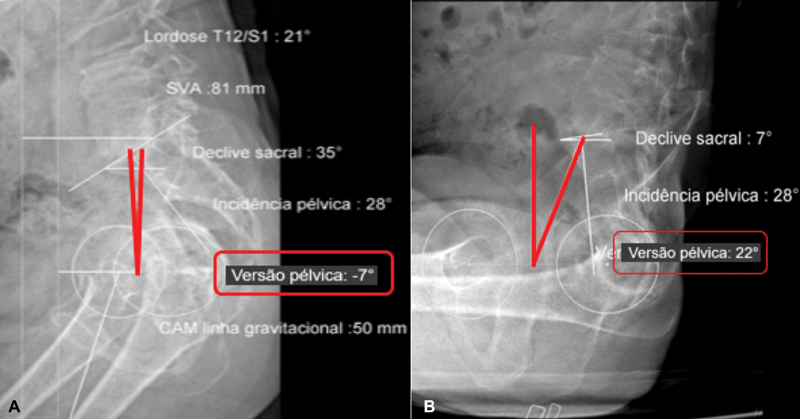

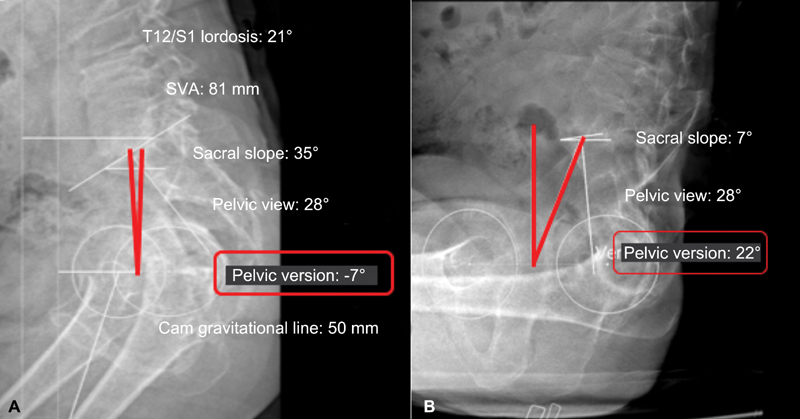

The evaluation with the patient standing up may demonstrate associated pelvic and lumbar changes. Increased sagittal pelvic tilt and lumbar lordosis may be concurrent with acetabular retroversion ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

(A) Pelvic version with the patient standing up and (B) sitting down. Pelvic version ranged 29° (from -7° to 22°). 1. T12/S1 lordosis: 21°, 2. SVA: 81 mm, 3. Sacral slope: 35°, 4. Pelvic view: 28°, 5. Pelvic version: -7°, 6. Cam gravitational line: 50 mm, 7. Sacral slope: 7°, 8. Pelvic view: 28°, 9. Pelvic version: 22°

Using computed tomography (CT), Ross et al. (2014) 12 showed that the anterior pelvic tilt resulted in an internal rotation decrease from 5.9° to 8.5° (under 90° of hip flexion and 15° of hip adduction) and 5.8° of acetabular retroversion; posterior pelvic inclination, however, increased the internal rotation from 5.1° (under 90° of hip flexion and 15° of hip adduction) to 7.4°.

Ligament laxity tests are important to identify patients with associated instability .13 The gait is carefully examined: patients with anterior hip pain tend to maintain a posterior pelvic tilt when walking, leaving the hip more extended, resulting in increased forces in the anterior hip. 14 15

Imaging studies also revealed that low pelvic views (defined as the angle between a line perpendicular to the central point of the sacral plateau and a line from this point to the axial center of the femoral heads) 16 ( Fig. 1 ), that is, a greater pelvic anterior inclination, may be associated with mixed-type FAI, 17 pelvic rotation, stance phase, upper limb movement and foot progression angle (FPA), which is usually about 7° in the lateral direction. 18 Proximal femoral retroversion and medial rotation limitation are frequently seen in FAI patients, and may lead to an excessive FPA in lateral rotation. In contrast, patients with excessive femoral anteversion usually present medially rotating FPA. However, the FPA analysis should be based on inspection of the entire limb, particularly of the patellar position, as this angle is influenced by the rotational profile of the hip, femur, tibia and talus, 19 and is associated with muscle and capsular effects. Patients with increased femoral anteversion and normal APP are often found as a result of compensatory lateral tibial torsion. 20 The stand-up examination is completed with the one-leg support test (Trendelenburg test) to assess abductor function.

The examination in the sitting position begins with the assessment of the neurological and vascular functions of the lower limbs. Medial and lateral rotations are measured in both hips. Patients with FAI typically present medial rotation restriction and normal lateral rotation. 21 The association of decreased medial rotation with increased lateral rotation indicates a proximal femoral retroversion or a decreased physiological anteversion. In contrast, increased medial rotation with decreased lateral rotation indicates increased femoral anteversion. Importantly, hip rotations are not exclusively influenced by femoral version. Factors such as ligamentous hyper-slackness and hip dysplasia, for instance, may influence hip rotations. Hip-rotation measurements can also be performed in dorsal and ventral recumbency. However, ligament function, pelvic position and measurement methodology can cause differences of up to 10° in the hip-rotation values assessed in different positions (sitting down or dorsal and ventral recumbency). 22 23 24

The examination in dorsal recumbency begins with palpation of the pubic region and search for hidden hernias, 25 which have been associated with FAI due to abdominal-muscle overload resulting from lack of hip mobility. 26 The evaluation proceeds with the hip flexion contracture test (Thomas test) and an evaluation of the adduction and abduction. This position includes most tests for femoroacetabular congruence that may be positive in FAI, instability or intra-articular disease. 1 Ganz et al. (2003) 27 described an impingement test performing flexion, adduction and medial rotation. McCarthy et al. (2003) 28 reported the dynamic evaluation of FAI and its relationship with the acetabular labrum.

Flexion, adduction and internal rotation (FADIR) and flexion, abduction, external rotation (FABER) maneuvers revealed that FAI patients have lower internal rotation and adduction during the FADIR, and lower abduction and external rotation during the FABERE, in addition to greater pelvic movement, in comparison to a control group. 29

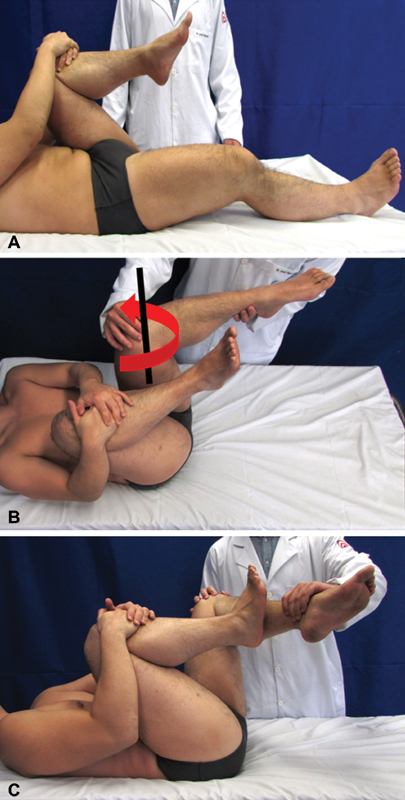

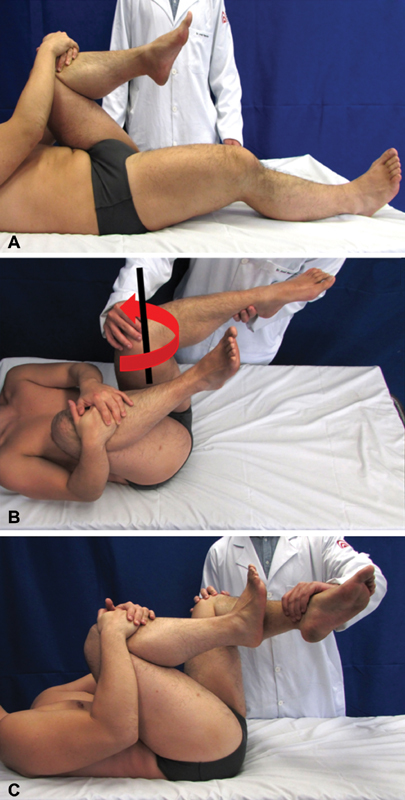

Martin suggested a more active evaluation, using the dynamic internal rotation impingement (DIRI) test and the dynamic external rotation impingement (DIRE) test. 1 In DIRI, the patient in dorsal recumbency is instructed to hold the contralateral hip at flexion greater than 90°, thus establishing a pelvic zero set-point and eliminating lumbar lordosis ( Fig. 2A ). The examined hip is then flexed at 90° degrees or more and passed passively along a wide adduction and internal (medial) rotation arc ( Fig. 2B ). The degree of flexion required for impingement depends on the femoral version and the type and location of the anterior impingement. The test is positive if it evokes pain. The DIRI test may also be positive in cases of posterior instability. The DIRE test is performed with the patient positioned in the same manner as in the DIRI, but the hip is dynamically carried in wide abduction and external rotation arc ( Fig. 2C ). The DIRE detects superior and posterior impingements, but it can be positive in cases of anteroinferior instability with round-ligament rupture and/or laxity. 30 The test is positive when it evokes pain or a sense of instability. Another test performed in supine position to assess femoroacetabular congruence is the posterior impingement test. With the patient on the edge or end of the stretcher, the hip is passively extended, abducted and rotated externally. This test evaluates the congruence between the posterior acetabular wall and the femoral neck, and it is positive in cases of posterior impingement or anterior instability. Important complementary tests in supine position during symptomatic-hip investigation include passive rotation (log roll), the dial test 31 , the active hip flexion test against resistance with the knee extended (Stinchfield) and the the FABERE test (or Patrick test).

Fig. 2.

(A) Positioning with hip flexion to achieve straightening of the lumbar lordosis. (B) DIRI maneuver, in which the examined hip is flexed (in this case the left hip), followed by internal rotation and adduction. (C) DIRE maneuver: in this case, with the lumbar spine already straightened, left hip abduction and concomitant internal rotation are performed to evaluate injuries or impingement at the upper and posterior regions.

The lateral recumbency position can also be used to assess femoroacetabular congruence through maneuvers associating flexion, adduction and internal rotation or extension, abduction and external rotation. The evaluation of peritrochanteric structures is performed in lateral recumbency on the opposite side, including palpation, abductor musculature strength tests and contracture tests. 1 These tests are important since abnormalities in the peritrochanteric structures can coexist with FAI and influence recovery after the surgical treatment.

The examination is concluded with the patient in ventral recumbency, with the femoral anteversion test (Craig test) and the rectus femoris muscle contracture test (Ely test). 1

Cheatham et al. 32 published the main features and updates regarding FAI and labral injury and the sensitivity and specificity of the main physical examination maneuvers for FAI diagnosis.

The hip joint is supplied posteriorly by articular branches of the nerve to the quadratus femoris muscle, superior gluteus nerve branches, and/or a direct branch of the sciatic nerve. 33 Thus, intra-articular conditions may cause posterior pain. Similarly, pathologies in the deep gluteal space or lumbar spine may cause symptoms that are difficult to differentiate from intra-articular conditions. Therefore, in patients with posterior pain, the clinical examination should include the deep gluteal space, and an intra-articular anesthetic injection as a test should be considered in the diagnostic approach. 34

Imaging

Proper imaging analysis is critical for diagnosis, and it should consider history and physical examination findings. Defining diagnosis and treatment through poor quality tests will increase the chances of failure. Thus, the quality of the test should be evaluated before its interpretation, especially considering the patient's position during its performance. The standardization of the imaging analysis increases its accuracy and reduces the time to perform it. 35 Another important component in imaging evaluation is to consider the whole picture, meaning that the findings should be understood in association. For instance, a small cam-like deformity associated with femoral retroversion may be more severe than a larger cam-like deformity with normal femoral anteversion. It is important to remember the concept of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (Warwick), in which radiological interpretation is part of a context of signs, symptoms and imaging analyses. The diagnosis of femoroacetabular impingement must not rely solely on imaging. 36

Radiography

Radiography is fundamental for the diagnosis and treatment of FAI patients. It is a simple, inexpensive, fast and widely available method. Radiographs allow a morphological evaluation of the hip and determine the existence of sequelae of childhood hip disease and osteoarthritis. The literature indicates different radiographic series for the initial evaluation of painful hips in young adults. 35 37 38 Nepple et al. 39 evaluated the accuracy of different radiographic views in detecting cam-like deformities by comparing them with CT. These authors demonstrated that the Dunn view with 45° of flexion was the most sensitive (71% to 80%), while the Lauenstein view (lateral frog leg) was the most specific (91% to 100%) method. Excluding the lateral cross-table incidence did not change sensitivity. Additionally, there was a significant correlation between the area assessed at different radiographic views and CT: anteroposterior (AP) radiography/12:00 (upper view), Dunn/1:00 (anterolateral view), Lauenstein/3:00 (anterior view), and cross-table/3:00 (anterior view). 39

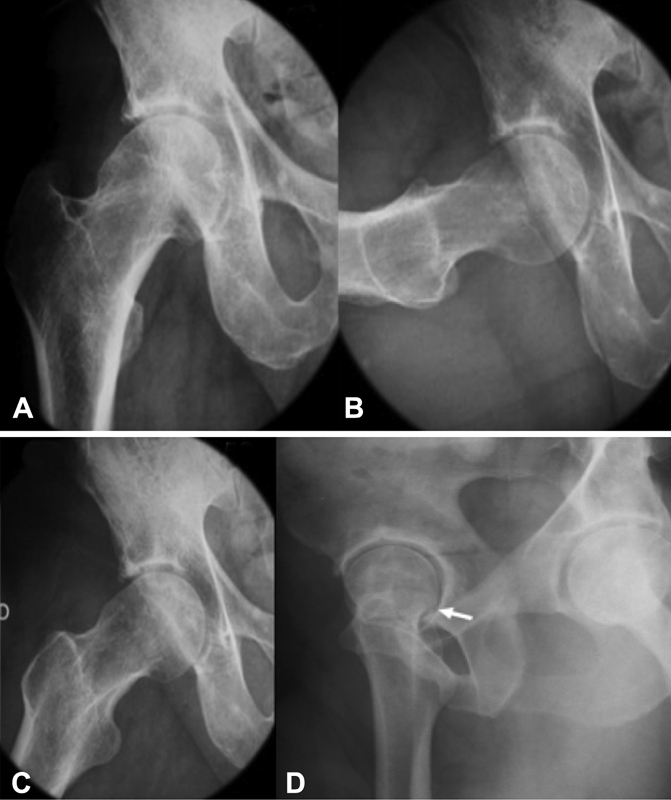

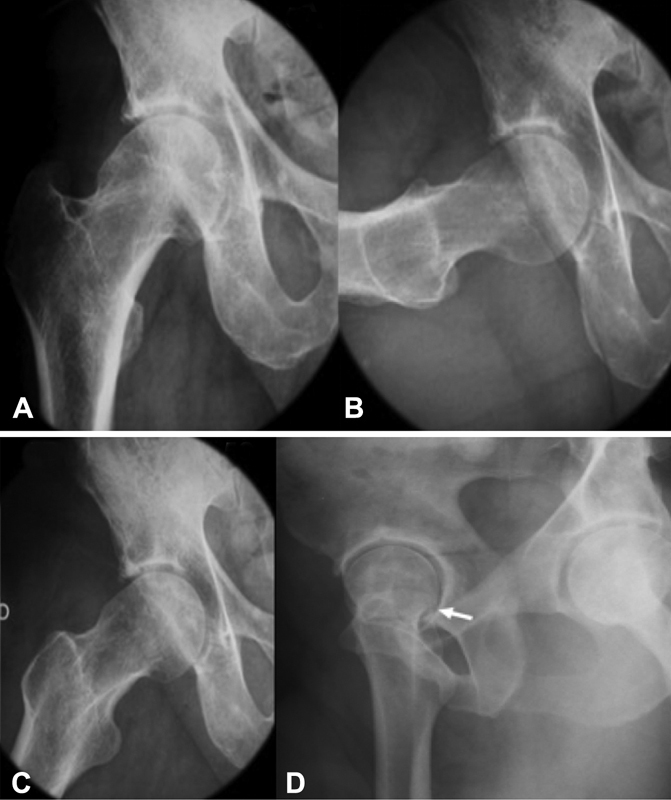

The performance of 5 radiographic views is suggested for the initial evaluation of FAI: 1) AP pelvic radiograph; 2) Dunn with 45° of hip flexion and 20° of abduction in neutral rotation; 3) Lauenstein with 30° to 40° of hip flexion and 45° of abduction (the sole of the foot in contact with the contralateral knee); 4) lateral Ducroquet with 90° of flexion and 45° of abduction; and 5) false lateral Lequesne 35 ( Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Radiographic hip views in FAI research. (A) Anteroposterior view. (B) Ducroquet view. (C) Dunn view for the visualization of cam-type deformity. Note the rectification and prominence of the neck-head transition region. (D) X-ray image in Lequesne position.

Errors in performing AP pelvic radiography are frequent and may compromise the diagnosis. Anteroposterior radiography of the pelvis is performed with the patient in dorsal recumbency, with the lower limbs at 15° medial rotation. 37 The distance between the film and the x-ray tube should be 120 cm, and its cross-over mark should be centered midway between the upper edge of the pubic symphysis and a line connecting both anterosuperior iliac spines. 37 Acetabular morphology on AP pelvic radiographs is influenced by pelvic rotation and inclination, which may vary considerably according to the patient's position during the examination. 40

The hemipelves should be symmetrical on the radiograph, with the coccyx aligned with the pubic symphysis, iliac wings and obturated foramina, in addition to symmetrical teardrop images. Siebenrock et al. 41 suggested that the ideal radiographic distance between the pubic symphysis and the middle of the sacrococcygeal junction is between 2.5 cm and 4 cm in women, and between 4 cm and 5.5 cm in men. However, identifying the sacrococcygeal joint can be difficult. Therefore, Clohisy et al. 37 suggested that the distance between the upper edge of the pubic symphysis and the end of the coccyx should be between 1 cm and 3 cm. Variations in the degree of hip rotation may also impair the assessment of the morphology of the proximal femur, 42 emphasizing the importance of standardized radiographs.

A recent study revealed that there was no difference between a pelvic AP radiograph and a hip-centered posteroanterior fluoroscopy regarding the center-edge (CE) angle, the vertical-center-anterior (VCA) angle, the Sharp angle, and the acetabular index; in fluoroscopy, however, the anterior coverage was smaller, the crossover sign was 30% smaller, and the retroversion was underestimated. 43

Radiographic interpretation must be performed in an organized manner. All aspects of acetabular and femoral-bone morphology should be analyzed together, identifying structural changes related to FAI and instability. Direct search for impingement signals with no sequential analysis will lead to diagnostic and treatment errors. Table 1 describes the parameters that must be evaluated at different radiographic views.

Table 1. Standardized interpretation of radiographs in the evaluation of natural hips. The analyzed parameters are shown according to the radiographic view.

| Pelvic anteroposterior radiograph |

| 1. Test quality: proper pelvic inclination and rotation |

| 2. Lateral center-edge angle |

| 3. Angle of inclination of the acetabular roof |

| 4. Extrusion of the femoral head |

| 5. Lateralization of the femoral head |

| 6. Femoral neck-shaft angle |

| 7. Medial and lateral joint space at the acetabular roof |

| 8. Orientation of the acetabular walls |

| 9. Orientation of the ischial spines |

| 10. Sphericity of the femoral head |

| 11. Positive findings: cysts, osteophytes, implants, stress fracture, periosteal reaction, medullary bone alterations, proximity of the trochanter to the ischium/acetabulum, prominent anterosuperior iliac spine |

| Dunn 45° and lateral frog views |

| 1. Shape of the acetabulum shape |

| 2. Sphericity of the femoral head |

| 3. Alpha angle |

| 4. Positive findings |

| False Lateral Lequesne View |

| 1. Shape of the acetabulum |

| 2. Sphericity of the femoral head |

| 3. Variation from posterior to anterior of the thickness of the joint cartilage |

| 4. Center-anterior border angle |

| 5. Positive findings, especially anterosuperior or posteroinferior arthrosis |

The most common FAI-related acetabular radiographic findings include acetabular overlay, acetabular retroversion, and prominent anteroinferior iliac spine. In 1962, Ruelle and Dubois 44 used the term deep thigh in reference to the radiographic finding of acetabular-fundus medialization in relation to the ilioischial line. Until recently, this signal had been interpreted as indicative of acetabular overcoverage. 27 However, Anderson et al. 45 and Nepple et al. 46 concluded that the radiographic finding of deep thigh (acetabular-fundus migration beyond the ilioischial line) was not associated with femoral-head overcoverage, that is, it was not associated with larger center-edge angles or smaller acetabular indices. In addition, dysplastic hips with excessive anteversion can be misinterpreted as an overcovered acetabulum when considering Ruelle and Duboi's classic deep thigh definition. 44 47 Therefore, acetabular coverage of the femoral head should be assessed based on the lateral center-edge angle described by Wiberg, 48 in which values above 39° indicate excessive acetabular coverage. Tönnis and Heinecke 49 defined values between 39° and 44° in hips with acetabular protrusion, and values above 44° in hips with acetabular protrusion.

In standardized pelvic radiographs of normal hips, the anterior acetabular wall should cover the femoral head less than the posterior wall, and the anterior and posterior wall edges usually meet superiorly and laterally, indicating acetabular anteversion. When the contours of the anterior and posterior walls meet more distally, the radiograph shows the crossover sign. This cranial retroversion predisposes to pincer-impingement development. 50 The extent of the projection of the sciatic spine medially to the ilioischial line is correlated to the height of the radiographic cross-over sign. 51 The posterior wall sign occurs when the posterior wall is located medially to the center of the femoral head, and indicates a more pronounced retroversion, called true retroversion. Pelvic tilt and rotation are determinant to the acetabular version seen on the radiographs and, therefore, a proper pelvic radiograph with correct patient positioning is essential to avoid false diagnoses. 40 Although the cross-over sign is widely associated with acetabular retroversion in the literature, Zaltz et al. 52 reported that it has a low positive predictive value (PPV) for acetabular retroversion when comparing adequate pelvic radiographs with CT images. Among 38 patients with radiographic cross-over sign, only 19 had focal or global (PPV: 50%) acetabular retroversion on CT. The anteroinferior iliac spine (EIAI) was responsible for the radiographic appearance of the cross-over sign in all 19 patients with anteverted acetabulum. In the same study, the authors classified the shape of the EIAI into three types based on three-dimensional CT. 39 In addition, other studies have reported that the shape of the EIAI is a contributing factor to the impingement between the femur and the pelvis. 53 54

The proximal femur may have the following FAI-related radiographic findings: pistol-grip deformity, increased alpha angle, reduced femoral head/neck offset, and cystic imaging in the impingement zone at the femoral head-neck transition. Pistol-grip deformity is recognized on AP pelvic radiographs, and it is believed to be secondary to a subclinical proximal femoral slippage. 55 However, it is argued that the major deformity in subclinical epiphyseal slippage is in the sagittal plane, and that it would not be usually evident in AP views. 56 57 In addition, the term pistol-grip represents a qualitative definition of cam-type deformity, and it does not enable a comparison of deformity, and is not an objective diagnostic criterion. 57 As such, Nötzli et al. 57 reported alpha-angle measurements in oblique axial MRI images, enabling a quantitative evaluation based on the anterior transition between the femoral neck and head, the most frequent location of cam-like deformities. The use of the alpha angle to evaluate the morphology of the femoral head-neck transition was then extrapolated to CT and different radiographic views. Nötzli et al. 57 found an average alpha angle of 42° (range: 33° to 48°) in asymptomatic individuals, compared to an average value of 74° (range: 55° to 95°) in cam-type FAI patients. Thus, alpha angles lower than 55° have been considered normal. A more recent study described a low specificity, of 56%, for symptomatic cam-type deformity when using an alpha angle of 55° as the normal limit. 58 The authors suggested raising the alpha angle limit from 55° to 60°, increasing the specificity to 74%. 58 Although validated only at the cross-table view, 57 the alpha angle is often measured in other radiographic views. The reduced anterior femoral head/neck offset can also be used to detect cam-type deformities. An offset to the ratio of the diameter of the femoral head of less than 0.17 is indicative of cam-type FAI. 59 A cystic formation in the impingement area of the femoral head-neck transition can be observed in some patients. Importantly, FAI morphology should not be based solely on femoral head-neck transition analysis. Acetabular morphology, other femoral morphology features, and femoral and acetabular versions influence the occurrence or not of FAI-related symptoms. In addition, the coexistence of instability and other abnormalities is not uncommon. This fact reinforces the importance of an appropriate physical examination for FAI diagnosis.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Computed Tomography Imaging

Diagnosis and treatment of patients with femoroacetabular impingement usually require additional imaging techniques other than radiography. The CT and especially nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) help exclude differential diagnoses that may cause FAI-like symptoms, including femoral-head osteonecrosis, transient osteoporosis, synovial and inflammatory diseases, stress fractures, infectious diseases and tumors. The CT and NMR also provide a better understanding of femoral and acetabular morphology, highlighting the study of the proximal femur and acetabulum version.

Moreover, the chondrolabral damage caused by FAI can be better estimated by CT and especially NMR with intra-articular contrast media. The injection of an intra-articular contrast medium (gadolinium) and specific sequences increase the accuracy of NMR for chondrolabral lesions, and assist in ruling out synovial diseases. The sequences are usually performed in three planes: coronal, sagittal, and oblique axial (at the femoral-neck plane). Labral characterization is important on NMR, since the lesions may include changes in size (hypo/hyperplasia), substance, and peripheral avulsions. The CT and NMR are also important to define the best surgical approach.

In a metanalysis from 2011, Smith et al. 60 observed the accuracy of NMR compared to magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) in the evaluation of labral lesions, demonstrating the advantages of MRA; however, this study included several causes besides FAI.

More recently, in 2017, another systematic literature review 61 and meta-analysis comparing MRA and MRI with intravascular injection of contrast media in the assessment of labral and chondral injuries exclusively in FAI cases showed a greater accuracy of MRA compared to other methods in the detection of lesions.

Further studies are required on specific NMR protocols with intravascular injection of contrast media (delayed gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of cartilage, dGEMRIC) to evaluate cartilage viability and 3-Tesla protocols. 5

As such, the three-dimensional reconstruction feature available on CT scans may facilitate the understanding of FAI morphology and the determination of the surgical strategy.

Final Considerations

A detailed history, along with a thorough physical examination and standardized evaluation of imaging scans, are essential for the proper FAI diagnosis. It is crucial that orthopedists treating young patients with hip pain are familiar with the FAI research flowchart. This will allow them to determine the appropriate treatment for each patient.

Footnotes

Conflito de Interesses Os autores declaram não haver conflito de interesses.

Referências

- 1.Martin H, Palmer I, Hatem M. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014. Patient History and Exam. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clohisy J C, Keeney J A, Schoenecker P L. Preliminary assessment and treatment guidelines for hip disorders in young adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;441(441):168–179. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000193511.91643.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reiman M P, Mather R C, III, Hash T W, II, Cook C E. Examination of acetabular labral tear: a continued diagnostic challenge. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(04):311–319. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reiman M P, Goode A P, Cook C E, Hölmich P, Thorborg K. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for the diagnosis of hip femoroacetabular impingement/labral tear: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(12):811. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saied A M, Redant C, El-Batouty M. Accuracy of magnetic resonance studies in the detection of chondral and labral lesions in femoroacetabular impingement: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(01):18–83. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1443-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrd J. New York: Springer US; 2005. Physical Examination. Operative Hip Arthroscopy. 2nd ed; pp. 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byrd J W. Evaluation of the hip: history and physical examination. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2007;2(04):231–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guimarães R P, Alves D P, Silva G B. Tradução e adaptação transcultural do instrumento de avaliação do quadril “Harris Hip Score.”. Acta Ortop Bras. 2010;18(03):142–147. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellamy N, Buchanan W W, Goldsmith C H, Campbell J, Stitt L W. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(12):1833–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byrd J W, Jones K S. Prospective analysis of hip arthroscopy with 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(06):578–587. doi: 10.1053/jars.2000.7683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cibere J, Thorne A, Bellamy N. Reliability of the hip examination in osteoarthritis: effect of standardization. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(03):373–381. doi: 10.1002/art.23310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross J R, Nepple J J, Philippon M J, Kelly B T, Larson C M, Bedi A. Effect of changes in pelvic tilt on range of motion to impingement and radiographic parameters of acetabular morphologic characteristics. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(10):2402–2409. doi: 10.1177/0363546514541229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beighton P, Horan F. Orthopaedic aspects of the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1969;51(03):444–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis C L, Sahrmann S A, Moran D W. Effect of hip angle on anterior hip joint force during gait. Gait Posture. 2010;32(04):603–607. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis C L, Sahrmann S A. Effect of posture on hip angles and moments during gait. Man Ther. 2015;20(01):176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Legaye J, Duval-Beaupère G, Hecquet J, Marty C. Pelvic incidence: a fundamental pelvic parameter for three-dimensional regulation of spinal sagittal curves. Eur Spine J. 1998;7(02):99–103. doi: 10.1007/s005860050038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saltychev M, Pernaa K, Seppänen M, Mäkelä K, Laimi K. Pelvic incidence and hip disorders. Acta Orthop. 2018;89(01):66–70. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2017.1377017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perry J. Thorofare, NJ: Slack Incorporated; 1992. Gait Analysis Normal and Pathological Function. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Staheli L T, Corbett M, Wyss C, King H. Lower-extremity rotational problems in children. Normal values to guide management. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67(01):39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delgado E D, Schoenecker P L, Rich M M, Capelli A M. Treatment of severe torsional malalignment syndrome. J Pediatr Orthop. 1996;16(04):484–488. doi: 10.1097/00004694-199607000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly B T, Bedi A, Robertson C M, Dela Torre K, Giveans M R, Larson C M. Alterations in internal rotation and alpha angles are associated with arthroscopic cam decompression in the hip. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(05):1107–1112. doi: 10.1177/0363546512437731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar S, Sharma R, Gulati D, Dhammi I K, Aggarwal A N. Normal range of motion of hip and ankle in Indian population. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2011;45(06):421–424. doi: 10.3944/AOTT.2011.2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prather H, Harris-Hayes M, Hunt D M, Steger-May K, Mathew V, Clohisy J C. Reliability and agreement of hip range of motion and provocative physical examination tests in asymptomatic volunteers. PM R. 2010;2(10):888–895. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simoneau G G, Hoenig K J, Lepley J E, Papanek P E. Influence of hip position and gender on active hip internal and external rotation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;28(03):158–164. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1998.28.3.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyers W C, Foley D P, Garrett W E, Lohnes J H, Mandlebaum B R; PAIN (Performing Athletes with Abdominal or Inguinal Neuromuscular Pain Study Group).Management of severe lower abdominal or inguinal pain in high-performance athletes Am J Sports Med 200028012–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hammoud S, Bedi A, Magennis E, Meyers W C, Kelly B T. High incidence of athletic pubalgia symptoms in professional athletes with symptomatic femoroacetabular impingement. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(10):1388–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ganz R, Parvizi J, Beck M, Leunig M, Nötzli H, Siebenrock K A. Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(417):112–120. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000096804.78689.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCarthy J, Busconi B, Owens B. New York, NY: Springer US; 2003. Assessment of the painful hip. Early Hip Disorders; pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kapron A L, Aoki S K, Peters C L, Anderson A E. In-vivo hip arthrokinematics during supine clinical exams: Application to the study of femoroacetabular impingement. J Biomech. 2015;48(11):2879–2886. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin R L, Palmer I, Martin H D. Ligamentum teres: a functional description and potential clinical relevance. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(06):1209–1214. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1663-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Philippon M J, Zehms C T, Briggs K K, Manchester D J, Kuppersmith D A. Hip Instability in the Athlete. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2007;15:189–194. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheatham S W, Enseki K R, Kolber M J. The clinical presentation of individuals with femoral acetabular impingement and labral tears: A narrative review of the evidence. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2016;20(02):346–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Birnbaum K, Prescher A, Hessler S, Heller K D. The sensory innervation of the hip joint--an anatomical study. Surg Radiol Anat. 1997;19(06):371–375. doi: 10.1007/BF01628504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Byrd J W, Jones K S. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical assessment, magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance arthrography, and intra-articular injection in hip arthroscopy patients. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(07):1668–1674. doi: 10.1177/0363546504266480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polesello G C, Nakao T S, de Queiroz M C. Proposal for standardization of radiographic studies on the hip and pelvis. Rev Bras Ortop. 2015;46(06):634–642. doi: 10.1016/S2255-4971(15)30318-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Griffin D R, Dickenson E J, O'Donnell J. The Warwick Agreement on femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAI syndrome): an international consensus statement. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(19):1169–1176. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clohisy J C, Carlisle J C, Beaulé P E. A systematic approach to the plain radiographic evaluation of the young adult hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90 04:47–66. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reis A C, Rabelo N D, Pereira R P. Radiological examination of the hip - clinical indications, methods, and interpretation: a clinical commentary. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014;9(02):256–267. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nepple J J, Martel J M, Kim Y J, Zaltz I, Clohisy J C; ANCHOR Study Group.Do plain radiographs correlate with CT for imaging of cam-type femoroacetabular impingement? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012470123313–3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tannast M, Zheng G, Anderegg C. Tilt and rotation correction of acetabular version on pelvic radiographs. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;438(438):182–190. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000167669.26068.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siebenrock K A, Kalbermatten D F, Ganz R. Effect of pelvic tilt on acetabular retroversion: a study of pelves from cadavers. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(407):241–248. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200302000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Monazzam S, Bomar J D, Agashe M, Hosalkar H S. Does femoral rotation influence anteroposterior alpha angle, lateral center-edge angle, and medial proximal femoral angle? A pilot study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(05):1639–1645. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2708-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Büchler L, Schwab J M, Whitlock P W, Beck M, Tannast M. Intraoperative evaluation of acetabular morphology in hip arthroscopy comparing standard radiography versus fluoroscopy: a cadaver study. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(06):1030–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ruelle M, Dubois J L. [The protrusive malformation and its arthrosic complication. I. Radiological and clinical symptoms. Etiopathogenesis] Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic. 1962;29:476–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anderson L A, Kapron A L, Aoki S K, Peters C L. Coxa profunda: is the deep acetabulum overcovered? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(12):3375–3382. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2509-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nepple J J, Lehmann C L, Ross J R, Schoenecker P L, Clohisy J C. Coxa profunda is not a useful radiographic parameter for diagnosing pincer-type femoroacetabular impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(05):417–423. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.01664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tannast M, Leunig M; Session Participants.Report of breakout session: Coxa profunda/protrusio management Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012470123459–3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wiberg G. The anatomy and roentgenographic appearance of a normal hip joint. Acta Chir Scand. 1939;83 05:7–38. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tönnis D, Heinecke A. Acetabular and femoral anteversion: relationship with osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81(12):1747–1770. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199912000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reynolds D, Lucas J, Klaue K. Retroversion of the acetabulum. A cause of hip pain. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81(02):281–288. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.81b2.8291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kalberer F, Sierra R J, Madan S S, Ganz R, Leunig M. Ischial spine projection into the pelvis : a new sign for acetabular retroversion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(03):677–683. doi: 10.1007/s11999-007-0058-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zaltz I, Kelly B T, Hetsroni I, Bedi A. The crossover sign overestimates acetabular retroversion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(08):2463–2470. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2689-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hetsroni I, Larson C M, Dela Torre K, Zbeda R M, Magennis E, Kelly B T. Anterior inferior iliac spine deformity as an extra-articular source for hip impingement: a series of 10 patients treated with arthroscopic decompression. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(11):1644–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.05.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Larson C M, Kelly B T, Stone R M. Making a case for anterior inferior iliac spine/subspine hip impingement: three representative case reports and proposed concept. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(12):1732–1737. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stulberg S D, Cordell L D, Harris W H, Ramsey P L, MacEwen G D. St Louis: 1975. Unrecognized childhood hip disease: a major cause of idiopathic osteoarthritis of the hip; pp. 212–128. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goodman D A, Feighan J E, Smith A D, Latimer B, Buly R L, Cooperman D R. Subclinical slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Relationship to osteoarthrosis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(10):1489–1497. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199710000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nötzli H P, Wyss T F, Stoecklin C H, Schmid M R, Treiber K, Hodler J. The contour of the femoral head-neck junction as a predictor for the risk of anterior impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84(04):556–560. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b4.12014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sutter R, Dietrich T J, Zingg P O, Pfirrmann C W. How useful is the alpha angle for discriminating between symptomatic patients with cam-type femoroacetabular impingement and asymptomatic volunteers? Radiology. 2012;264(02):514–521. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12112479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eijer H, Myers S R, Ganz R. Anterior femoroacetabular impingement after femoral neck fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2001;15(07):475–481. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200109000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith T O, Hilton G, Toms A P, Donell S T, Hing C B. The diagnostic accuracy of acetabular labral tears using magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance arthrography: a meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2011;21(04):863–874. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-1956-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reiman MP, Thorborg K, Goode AP, Cook CE, Weir A, Hölmich P. Diagnostic Accuracy of Imaging Modalities and Injection Techniques for the Diagnosis of Femoroacetabular Impingement/Labral Tear: A Systematic Review With Meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(11):2665–2677 [DOI] [PubMed]