Abstract

Background

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends the use of spirometry and measuring the fraction of exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) as part of the diagnostic work-up for children with suspected asthma, and spirometry for asthma monitoring, across all care settings. However, the feasibility and acceptability of these tests within primary care are not known.

Aim

To investigate the feasibility, acceptability, training, and capacity requirements of performing spirometry and FeNO testing in children managed for asthma in UK primary care.

Design and setting

Prospective observational study involving 10 general practices in the East Midlands, UK, and 612 children between 2016 and 2017.

Method

Training and support to perform spirometry and FeNO in children aged 5 to 16 years were provided to participating practices. Children on the practice’s asthma registers, and those with suspected asthma, were invited for a routine asthma review. Time for general practice staff to achieve competencies in performing and/or interpreting both tests, time to perform the tests, number of children able to perform the tests, and feedback on acceptability were recorded.

Results

A total of 27 general practice staff were trained in a mean time of 10.3 (standard deviation 2.7) hours. Usable spirometry and FeNO results were obtained in 575 (94%) and 472 (77%) children respectively. Spirometry is achievable in the majority of children aged ≥5 years, and FeNO in children aged ≥7 years. All of the staff and 97% of families surveyed provided positive feedback for the tests.

Conclusion

After training, general practice staff obtained quality spirometry and FeNO data from most children tested. Testing was acceptable to staff and families. The majority of general practice staff reported that spirometry helped them to manage children’s asthma better.

Keywords: asthma, child health, general practice, implementation science, spirometry

INTRODUCTION

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends the use of spirometry and fraction of exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) testing to support asthma diagnosis, and annual spirometry to monitor asthma in children aged ≥5 years.1 This reflects concerns that diagnosing asthma based on clinical history alone results in both over- and under-diagnosis.2–4 Other guidelines also recommend spirometry for asthma diagnosis and monitoring.5–7

The NICE asthma guideline requires routine access to objective tests to support asthma diagnosis and monitoring in children across all care settings. This would represent a radical change in the way children’s asthma is managed in general practice, and has been met with criticism, partly fuelled by the lack of pragmatic studies using objective testing in children within the ‘real-world’ general practice setting.

A 2015 primary care study reported that measuring spirometry routinely in children did not improve asthma outcomes.8 This was primarily an adult study, which included a post-hoc subgroup analysis in the children, but without appropriate power calculations a priori. In addition, this trial did not report changes to the asthma management as a result of spirometry data. Objective tests will only improve outcomes if abnormal test results are acted on. In secondary care, there is some evidence that children monitored using FeNO-directed treatment algorithms have fewer asthma attacks,9 but there are no data relating to primary care.

The authors recently reported the results of spirometry and FeNO testing from a large prospective UK primary care observational study in children.10 They observed a high prevalence of abnormal lung function and FeNO levels, and concluded that a symptoms-based assessment of asthma alone is inadequate to identify children at high risk of poor outcomes.

However, any attempt to implement spirometry and FeNO testing for children in general practice must first seek to identify the feasibility of performing the tests as part of real-life primary care asthma management, and the acceptability of the tests for families and primary care clinical staff. This article reports the implementation findings, including feasibility, acceptability, training, and capacity requirements of performing spirometry and FeNO testing from the authors’ prospective UK primary care observational study in children.10

How this fits in

| Asthma guidelines recommend the use of spirometry and FeNO to support asthma diagnosis, and spirometry for monitoring, in adults and children aged ≥5 years. These tests are not routinely performed in children in general practice. In order to better understand the feasibility and acceptability of these tests to families and primary care staff, 612 children in 10 Leicestershire practices were studied and all children, families, and general practice staff surveyed. Training needs, time taken to complete the tests, success rate at first attempt, and test acceptability were investigated. Findings showed that spirometry and FeNO testing are feasible, and take a mean of <10 minutes to complete. Spirometry is achievable in the majority of children aged ≥5 years, and FeNO in children ≥7 years. Both tests were acceptable to families and healthcare staff. Importantly, the majority of staff in general practices stated that they found the tests helpful in managing children’s asthma better. |

METHOD

This was a prospective observational cross-sectional cohort study conducted in the East Midlands, UK, between 2016 and 2017.

Sites

The study sought to include general practices of different sizes, serving populations of varying ethnic and socioeconomic profiles. The Primary Care Clinical Research Network identified potential practices based on these criteria. The 17 suggested general practices were contacted, and 10 agreed to participate.

Each practice identified clinical staff for training to perform and/or interpret spirometry and FeNO tests in children. These were staff who then went on to perform asthma reviews and/or lung function testing in children independently following training, such as practice nurses (PNs) and healthcare assistants (HCAs).

Training

In Leicestershire, adult spirometry training to general practices is provided by the Leicestershire Partnership Trust, the provider for community-based services within the region. Competency is deemed to be reached following 20 to 40 supervised procedures. They do not currently provide training for paediatric spirometry or FeNO testing.

The authors developed and delivered the two-part paediatric training package for this study modelled on the existing adult training package, with the addition of FeNO testing. Based on general practice feedback during initial meetings, and in line with the adult spirometry training available in Leicestershire, three levels of paediatric training were provided depending on the job role of prospective trainees:

perform spirometry and FeNO testing but not to interpret;

interpret spirometry and FeNO test results but not to perform;

perform and interpret spirometry and FeNO tests.

Part 1: 2-hour face-to-face teaching

This covered theoretical and practical aspects of spirometry and FeNO testing in children. It was delivered in small teaching groups, and included a short presentation, demonstrations, practice, and teaching material handouts. Topics covered included: indications for testing, set-up, calibration, test procedure, acceptability of spirometry traces, and test interpretation.

An update on the new NICE guidelines was included with an emphasis on the recommended changes to current practice, the diagnostic algorithm, and objective tests underpinning a diagnosis of asthma in children.

All trainees attended this teaching regardless of the level of training they required.

Part 2: practical training

This was delivered alongside the asthma review clinics. All trainees observed the trainer perform at least five spirometry and FeNO tests. Subsequently, trainees were directly supervised to either perform, interpret, or perform and interpret spirometry and FeNO tests depending on the level of training required. Supervision continued until assessed as competent by both the trainer and trainee themselves, based on predefined competencies lists. Different competencies lists were developed for each training level, and included: indications for testing, equipment set-up and maintenance, performing the tests themselves, and/or interpretation of data.

The training and competencies lists were developed in conjunction with senior academic and clinical respiratory physiologists within the research team, adapted from the existing Leicestershire training for adult spirometry.

A paediatric respiratory trainee doctor and a senior paediatric asthma nurse delivered all of the training. The duration of training required for each staff member to achieve competencies in spirometry and FeNO testing was recorded.

Procedures

Spirometry was performed using a portable spirometer. All manoeuvres were performed according to the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS) standards.11

FeNO was measured using NIOX Vero®. Children were asked to inhale ambient air through a nitrogen oxide scrubber to total lung capacity, and then exhale for 10 seconds.12

Patient participants

Children aged 5 to 16 years on the practice asthma register or children with suspected asthma were invited by letter for an asthma review at their general practice. Children with suspected asthma were defined as those not on the asthma register but who, in the previous 12 months, were prescribed: inhaled corticosteroids, or ≥2 short-acting β2 agonist (SABA) metered dose inhalers, or oral corticosteroids for acute wheeze/cough/breathlessness.

Spirometry and FeNO testing were attempted in all children. The time taken to perform each test, and proportion of successful tests,11 were recorded. Usable spirometry data were defined as recorded values from at least two acceptable manoeuvres as per ATS/ERS criteria.11

Feedback

The healthcare professional performing the review completed an outcome form for each child reviewed, consisting of the following questions:

Do you think your plan would have been different if spirometry and FeNO were not available?

Did you find the tests useful in helping with your diagnosis/management plan?

Feedback from parents was obtained using a modified friends and family test13 with the question, ‘How likely are you to recommend these breathing tests to friends and family if their children needed an asthma review at this practice?’ Response options ranged from extremely likely to extremely unlikely.

Children were asked: ‘Would you be happy to try these breathing tests again?’ Response options were: ‘yes’, ‘no’, or ‘don’t mind’.

Feedback was sought immediately following each asthma review.

Analysis

Training and testing times are presented as descriptive data. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) number of minutes required for training are presented for all staff. The proportion of successful tests in children were analysed by age group and are shown on a line graph.

Patient feedback is presented as descriptive data of the proportion of responses falling under each feedback category, from ‘strongly recommend’ to ‘strongly not recommend’.

Continuous variables were compared using unpaired t-tests for parametric data, and Kruskal–Wallis tests for non-parametric data. All statistical tests were performed at the α = 5% level. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 24.0) and GraphPad Prism (version 7.00).

RESULTS

Practices

The 10 participating practices (Table 1) served a population of almost 120 000 people. Of these, five practices were located in inner-city Leicester, two were in village locations, and three were in surrounding towns. The average practice size was larger when compared nationally. This was skewed by practice B, which is considerably larger than typical general practice surgeries. Excluding practice B, the average practice size was 7975 registered patients, which is in line with the national average. The mean proportion of patients recorded on the asthma register and the median deprivation index of participating practices were also similar to the national average. The cohort had a larger proportion of registered patients aged <18 years, and who were ethnically non-white. This is reflective of the local demographic of Leicestershire.15

Table 1.

Characteristics of participating practices, N = 10

| Characteristics | Site | Study meana | England meana (2017/2018) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | |||

| Registered patients, n | 10 288 | 48 196 | 10 273 | 3519 | 8043 | 6956 | 10 522 | 5229 | 4083 | 12 861 | 11 997 | 8035 |

| Aged <18 years, % | 20.1 | 21.8 | 22.7 | 18.5 | 17.7 | 17.6 | 29.0 | 32.4 | 28.0 | 26.2 | 23.4 | 20.5 |

| On asthma register, all ages, % | 6.2 | 5.4 | 8.3 | 3.5 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 6.8 | 3.6 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 5.8 | 5.9 |

| Deprivation indexb | 10 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 (median) | 5 (median) |

| Non-white ethnicity, % | 2.6 | 3.8 | 6.9 | 40.8 | 18.5 | 3.9 | 16.7 | 19.3 | 65.5 | 62.3 | 24.0 | 14.0 |

Unless otherwise stated.

Weighted score for practice. Based on the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 2017.14 1 = most deprived; 10 = least deprived.

Training

Training was delivered to 27 PNs and HCAs (see Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 for details). No staff had previously had training to perform spirometry or FeNO testing in children.

Staff members achieved competencies after observing and performing tests (spirometry and FeNO) in a median of 24 children (interquartile range [IQR] 20 to 27) aged >5 years (IQR 4 to 6) in clinics.

The mean time for staff to achieve competencies in both spirometry and FeNO testing was 10.3 hours (SD 2.7).

When subgrouped by training needs, those needing training to perform the tests took 9.5 (SD 1.8) hours, to interpret 11.7 (SD 3.4) hours, and to both perform and interpret 9.8 (SD 2.5) hours to train. There were no statistically significant differences between groups in terms of training times needed.

Patients

Electronic database searches identified 1548 eligible children; 1097 (71%) were on their GP’s asthma register, and 451 (29%) were not.

Additionally, out of 614 (40%) children who attended clinics 456 (74%) were on the asthma register.

Written informed consent was obtained from carers of 613 children; one parent declined participation. One other parent later withdrew their consent without giving a reason, leaving 612 children in total for inclusion in the study (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of recruited children, N = 612

| Characteristics | n (%)a |

|---|---|

| Male | 332 (54.2) |

|

| |

| Age, mean, years (SD) | 10.0 (3.3) |

|

| |

| On asthma register | 456 (74.5) |

|

| |

| Previous spirometry testing | 58 (9.5) |

|

| |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 480 (78.4) |

| Asian | 82 (13.4) |

| Black | 21 (3.4) |

| Mixed | 20 (3.3) |

| Other | 9 (1.5) |

Unless otherwise stated. SD = standard deviation.

Test feasibility

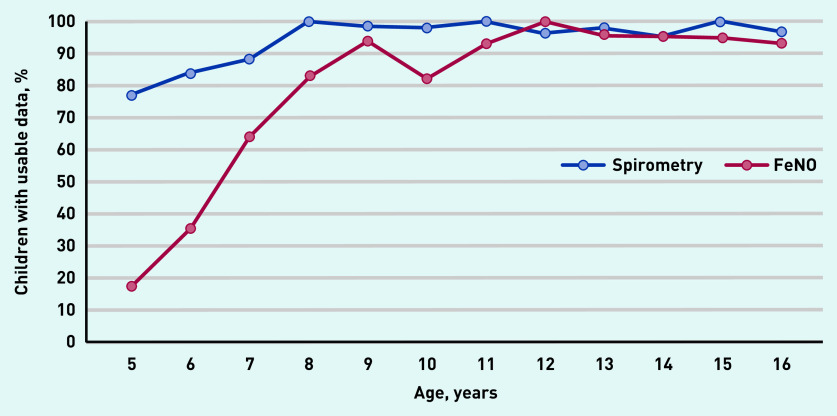

Usable spirometry was obtained from 575 (94%) children. A FeNO result was obtained from 472 (77%) children. Spirometry was achievable in almost 80% of children aged 5 years, increasing to 90% by age 7 years. FeNO testing was achievable in around 20% of children aged 5 years, increasing to >60% by age 7 years, and to >80% by age 8 years. The majority of children could manage both tests by age 7 years (Figure 1). The mean time to perform tests was 4.3 (SD 1.3) minutes for spirometry, 3.1 (SD 1.0) minutes for reversibility testing, and 2.4 (SD 1.0) minutes for FeNO testing. This did not include the time taken to administer SABA and the 15-minute wait for bronchodilator reversibility (BDR) testing.

Figure 1.

Proportion of children able to perform spirometry and FeNO testing by age, N = 612. FeNO = fraction of exhaled nitric oxide.

Feedback from families

Feedback forms were completed by 554 (91%) families. Of these, 97% of parents responded positively, saying they were either ‘extremely likely’ or ‘likely’ to recommend the tests to friends and family, 2% of responses were neutral (neither ‘likely’ nor ‘unlikely’), and 1% responded ‘don’t know’.

A total of 87% of children reported that they would be happy to do the tests again, 12% did not mind, and 1% would not like to do the tests again.

The researchers received 42 feedback forms containing free-text comments. Of these, 40 comments were positive towards spirometry and FeNO testing.

Examples of positive comments from families

‘A fantastic idea to hold these tests in a GP surgery.’

‘Great tests with positive feedback. Thank you!’

‘Help to give me a better understanding of my child’s asthma and how it changes.’

‘I am very happy to have breathing tests for my daughter, that is great chance to check if she have asthma or not.’

‘I think it is a wonderful idea to have these tests on a regular basis. Very reassuring for both parent and child that their breathing issues are being monitored.’

‘Tests were quick.’

‘This is really fun. Thank you.’ (child)

‘It only felt like playing a video game, didn’t see it being a test in any way!’ (child)

Negative comments were:

‘Takes long.’

‘I don’t like the sound.’

(child)

Feedback from clinical staff

Following training and implementation, 23 (85%) staff members responded to the online feedback questionnaire. Of those who responded, 100% felt that spirometry would help them to manage children’s asthma better; the figure was 91% for FeNO testing, (Supplementary Figure S1).

Free-text responses were available to the question: ‘Compared to before training, how has your attitude towards spirometry and FeNO testing for children changed and why?’

Overall, practice staff responded positively towards the use of spirometry and FeNO testing in their practice, specifically saying that these tests improved their confidence with asthma diagnosis and management in children:

‘Spirometry and FeNO are useful tools for both clinician and patient. History remains of utmost importance but having the results of tests assisted with confidence to change regimes and explaining to patient/parent.’

‘Feel it gives a clearer picture to know how to plan next steps towards better control.’

‘Spirometry enables us to see if asthma is controlled despite parents thinking children are asymptomatic.’

‘Has enhanced diagnosis, given confidence in diagnosis, made me aware of other causes i.e. rhinitis, insight and training can only improve care.’

‘Have much better understanding of how relates to treatment and whether treatment necessary.’

‘Able to explain better to parents and make better diagnosis.’

Free-text responses were also available to the question: ‘Now that you have had your training, do you think it will be possible to continue to provide these tests at your surgery regularly and what is needed in order to do so?’

Although practice staff reported that they would be keen to continue providing these tests, the main limitation reported was lack of available funding and equipment:

‘As long as we have plenty of equipment, there shouldn’t be a problem running an asthma clinic for children.’

‘Only the funding/equipment is needed. I believe it would benefit the practice and its patients.’

‘To continue in our practice we would need equipment and time, I believe the possibilities of providing these tests are with our GP partners and in discussion.’

‘I feel that this certainly would be a fantastic opportunity if this was possible. The equipment and funding for this would be the main issue.’

‘Yes it I think it would be possible, spirometry is already in use for adults so we have that capacity, we would need to purchase a FeNO monitor.’

‘Staff training, enough competent staff to carry out and interpret the test results and the time to do this in.’

‘I’d hope so. We’d need to create a clinic for this. Staff shortage at the moment may prohibit this at the moment.’

The practice nurse performing the review was asked to reflect on the objective test result’s impact on their clinical decision making for each child reviewed. General practice staff reportedly changed their management plan after seeing the objective test results in 130 out of 542 (24%) reviews. Moreover, they reported that spirometry and FeNO testing supported their decision making in 470 out of 508 (93%) children (data not shown).

Following their asthma review, six patients were referred to secondary care. Of these, three had obstructed spirometry despite high-dose inhaled corticosteroids, one had restricted spirometry, and two had normal spirometry but poor symptom control (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Summary

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study in the UK with the primary aim of exploring the feasibility and acceptability of implementing spirometry and FeNO testing in general practice for children’s asthma care.

The present findings have demonstrated that, after training, general practice staff obtain quality spirometry and FeNO data from most children aged 5 to 16 years in <10 minutes. The study found the tests were acceptable to staff and families. However, in order for the tests to be sustainable outside the research setting, increased funding for additional staff, clinic capacity, a more efficient training model, and funding for equipment are needed in primary care.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the study was the patient demographic of participating practices, which was representative of the local population. Another strength was that none of the participating practices were performing spirometry or FeNO testing in children before implementation. Therefore, training data were representative and applicable to other general practices with no prior experience of these tests in children. All asthma reviews were performed during normal general practice clinics, and were set up to reflect usual appointment time slots. Likewise, the majority of the cohort had never undergone spirometry or FeNO testing before. This strengthens the validity of the presented feasibility and acceptability data.

A limitation of the study was that all participating practices were from the same geographical region within the UK. It is possible that only the most motivated practices expressed an interest to participate. Likewise, as attendance for reviews was voluntary, the self-selecting cohort of families were likely to represent those with heightened concerns regarding their asthma. Therefore, the feedback questionnaires may be favourably biased towards acceptability.

A further limitation was that the authors also did not formally record the clinical management plans before and after the test results were available to general practice staff. Therefore, the reported impact the tests had on clinical decision making only represents a subjective reflection of whether general practice staff felt the tests altered or supported their management plans; this may be prone to recall bias. Though the authors attempted to conduct a pragmatic study within primary care, the intensity of supervision they were able to offer to practice staff during training is unlikely to be replicable without substantial increases in funding. Therefore, the success rate of spirometry and FeNO testing achieved during the present study may be better than that obtained outside a research setting.

Comparison with existing literature

The authors found no published data on training times needed to reach competency in performing spirometry or FeNO in children. In the UK, training and accreditation in spirometry are formalised by the Association for Respiratory Technology and Physiology (ARTP). By 2021 all individuals performing or interpreting adult spirometry in the UK must have undergone spirometry certification by the ARTP and be recorded on the national register.16 This is not an expected requirement for paediatric spirometry; however, formalised paediatric training is available and currently consists of 2 days of face-to-face training.

The training time required by the participants in the present study was not dissimilar to the amount of training currently offered by the ARTP. More efficient ways to deliver training needs to be explored (including online training) in order to reduce training costs and to reach a much larger target audience if these tests are to be rolled out nationwide.

Moreover, although there is clear published guidance on how to interpret spirometry and FeNO data to diagnose asthma,1 the application of these tests for asthma monitoring is less guideline driven. Competencies for performing and interpreting spirometry and FeNO are essentially the same for asthma diagnosis and monitoring, but how clinicians utilise test results to adjust management is far more nuanced and individualised to the patient. Clearer guidance is needed to facilitate treatment decisions based on spirometry and FeNO testing for primary care practitioners.

A previous study has demonstrated that quality spirometry can be achieved in children as young as 5 years of age;17 however, this study was performed within a controlled hospital research setting, and is not reflective of the busy general practice environment. In the study presented here, the authors demonstrated that spirometry data could be obtained from 94% of children aged between 5 to 16 years during real general practice asthma clinics. Despite the majority of children having never performed spirometry and FeNO tests, both tests were achievable in a mean time of <10 minutes. Additional time was required to administer a SABA, with repeat spirometry 15 minutes later, to test for BDR. This applies to between 24% and 30% of children attending for an asthma review10 and can be an additional burden on time. However, knowledge of airway obstruction and the presence of significant BDR in children is important and should prompt an adherence check, and an increase in medication if adherence is good as the child is likely undertreated. Under-recognised severity of asthma was an important factor for poor asthma outcomes in the 2014 National Review of Asthma Deaths report.18

By using the 15 minutes’ wait time for BDR to test the next child in clinic, it was found to be possible to perform all three tests by allocating 20-minute appointments to each child for testing alone.

Exhaled nitric oxide testing was unsuccessful in the majority of the present cohort aged <7 years, with only 17% of those aged 5 years producing a result. This reflects the need for a slower controlled exhalation in FeNO testing, which can be difficult for young children to perform. By the age of 8 years, the success rate of FeNO testing increased to >80%. The present finding is consistent with a small UK study that also reported feasibility of FeNO testing in general practice in adults and children aged ≥8 years.19

The NIOX Vero also offers a 6-second exhalation mode (for the present study the researchers used the 10-second mode), which may be easier for younger children to achieve. At the time of designing the study, the manufacturers advised that the 6-second mode was not yet validated. Two studies have since been published reporting that FeNO measurements obtained using either the 6- or 10-second mode are consistent in children ≤10 years of age.20,21 Reducing the exhalation time required to acquire a FeNO result should improve feasibility further in young children.

Spirometry and FeNO testing were acceptable to the majority of families in the present study. No studies were found reporting on the acceptability of paediatric spirometry in general practice. However, a previous small UK study, which included 22 adults and 15 children, found that FeNO in primary care was acceptable to patients and staff.19

Implications for practice

Both UK and international asthma guidelines recommend the use of objective tests, including spirometry and FeNO testing, for asthma diagnosis and monitoring in children and adults.1,5,6

The authors recently reported that abnormal spirometry and FeNO are common in children attending routine asthma reviews in primary care and that they relate poorly to patient/caregiver-reported symptoms. Moreover, in their previous study the authors observed a reduction in the number of asthma attacks and improved current asthma control test scores in the 6 months following an asthma review that included spirometry and FeNO testing.10 This supports the view that asthma management based on symptoms alone is inadequate.22,23

Usable spirometry and FeNO measurements can be achieved in most children in <10 minutes attending for a routine review in primary care. Importantly, families and primary care staff find the tests acceptable and helpful for asthma management. Based on these results, the authors believe that spirometry and FeNO should be offered to children aged ≥5 years with confirmed or suspected asthma attending primary care for routine asthma reviews. Additional funding and support will be needed for staff training, equipment, and additional clinic capacity if these tests are to be provided at the individual practice level. It may be possible to reduce costs and improve efficiency by concentrating expertise within local primary care hubs;1 where children can be referred to by their GPs for spirometry and FeNO testing

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff, children, and families at all participating general practices for their support of this study.

Funding

This study was funded from grants provided by the Midlands Asthma and Allergy Research Association (MAARA) and Circassia Pharmaceuticals to Erol A Gaillard (reference number: RM63G0782). The project fellow, David Lo, was funded by Health Education East Midlands. Yaling Yang was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Centre during the study.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the NHS research ethics committee (reference number: 16/EM/0162).

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

Erol A Gaillard has carried out consultancy work for Boehringer Ingelheim in November 2016 and Anaxsys in July 2018 with money paid to the institution (University of Leicester); received an investigator-led research grant from Circassia and Gilead; conducted a research collaboration with MedImmune; and received travel grants from Vertex. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management NG80. 2020 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80 (accessed 6 Oct 2020). [PubMed]

- 2.Looijmans-van den Akker I, van Luijn K, Verheij T. Overdiagnosis of asthma in children in primary care: a retrospective analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2016 doi: 10.3399/bjgp16X683965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang CL, Simons E, Foty RG, et al. Misdiagnosis of asthma in schoolchildren. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52(3):293–302. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brozek GM, Farnik M, Lawson J, Zejda JE. Underdiagnosis of childhood asthma: a comparison of survey estimates to clinical evaluation. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2013;26(6):900–909. doi: 10.2478/s13382-013-0162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) Expert panel report 3: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. NAEPP; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Global Initiative for Asthma Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2019 https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/GINA-2019-main-report-June-2019-wms.pdf (accessed 6 Oct 2020).

- 7.British Thoracic Society, Scottish Intercollegiate Network BTS/SIGN guideline on the management of asthma. 2019 https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/guidelines/asthma (accessed 6 Oct 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abramson MJ, Schattner RL, Holton C, et al. Spirometry and regular follow-up do not improve quality of life in children or adolescents with asthma: cluster randomized controlled trials. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2015;50(10):947–954. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petsky HL, Kew KM, Chang AB. Exhaled nitric oxide levels to guide treatment for children with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11(11):CD011439. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011439.pub2.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lo DK, Beardsmore CS, Roland D, et al. Lung function and asthma control in school-age children managed in UK primary care: a cohort study. Thorax. 2020;75(2):101–107. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2019-213068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(2):319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Thoracic Society. European Respiratory Society ATS/ERS recommendations for standardized procedures for the online and offline measurement of exhaled lower respiratory nitric oxide and nasal nitric oxide, 2005. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(8):912–930. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-710ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NHS England The friends and family test. 2014 https://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/AboutNHSservices/Documents/FFTGuide_Final_1807_FINAL.pdf (accessed 6 Oct 2020).

- 14.Public Health England National general practice profiles; indicator definitions and supporting information. 2017 https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/general-practice/data#page/6/gid/2000005/pat/152/par/E38000001/ati/7/are/B83620/iid/91872/age/1/sex/4 (accessed 6 Oct 2020).

- 15.Leicester City Council Setting the context: Leicester’s demographic profile. Leicester children’s Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA) 2015 https://www.leicester.gov.uk/media/183446/cyp-jsna-chapter-one-setting-the-context.pdf (accessed 6 Oct 2020).

- 16.Association for Respiratory Technology and Physiology Spirometry FAQs. http://www.artp.org.uk/en/spirometry/spiro-faqs.cfm (accessed 6 Oct 2020).

- 17.Eigen H, Bieler H, Grant D, et al. Spirometric pulmonary function in healthy preschool children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(3 Pt 1):619–623. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.3.2002054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy ML, Andrews R, Buckingham R, et al. Why asthma still kills: the National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD) 2014 https://www.asthma.org.uk/globalassets/campaigns/nrad-full-report.pdf (accessed 6 Oct 2020).

- 19.Gruffydd-Jones K, Ward S, Stonham C, et al. The use of exhaled nitric oxide monitoring in primary care asthma clinics: a pilot study. Prim Care Respir J. 2007;16(6):349–356. doi: 10.3132/pcrj.2007.00076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rickard K, Jain N, MacDonald-Berko M. Measurement of FeNO with a portable, electrochemical analyzer using a 6-second exhalation time in 7–10-year-old children with asthma: comparison to a 10-second exhalation. J Asthma. 2019;56(12):1282–1287. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2018.1541350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rickard K, MacDonald-Berko M, Anolik R, et al. Measurement of exhaled nitric oxide in young children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;122(3):343–345. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levy ML, Fleming L. Asthma reviews in children: what have we learned? Thorax. 2020;75(2):98–99. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2019-214143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pavord ID, Beasley R, Agusti A, et al. After asthma: redefining airways diseases. Lancet. 2018;391(10118):350–400. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30879-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]