Abstract

Understanding ozone (O3) formation regime is a prerequisite in formulating an effective O3 pollution control strategy. Photochemical indicator is a simple and direct method in identifying O3 formation regimes. Most used indicators are derived from observations, whereas the role of atmospheric oxidation is not in consideration, which is the core driver of O3 formation. Thus, it may impact accuracy in signaling O3 formation regimes. In this study, an advanced three-dimensional numerical modeling system was used to investigate the relationship between atmospheric oxidation and O3 formation regimes during a long-lasting O3 exceedance event in September 2017 over the Pearl River Delta (PRD) of China. We discovered a clear relationship between atmospheric oxidative capacity and O3 formation regime. Over eastern PRD, O3 formation was mainly in a NOx-limited regime when HO2/OH ratio was higher than 11, while in a VOC-limited regime when the ratio was lower than 9.5. Over central and western PRD, an HO2/OH ratio higher than 5 and lower than 2 was indicative of NOx-limited and VOC-limited regime, respectively. Physical contribution, including horizontal transport and vertical transport, may pose uncertainties on the indication of O3 formation regime by HO2/OH ratio. In comparison with other commonly used photochemical indicators, HO2/OH ratio had the best performance in differentiating O3 formation regimes. This study highlighted the necessities in using an atmospheric oxidative capacity-based indicator to infer O3 formation regime, and underscored the importance of characterizing behaviors of radicals to gain insight in atmospheric processes leading to O3 pollution over a photochemically active region.

Keywords: Atmospheric oxidation, O3 formation regimes, WRF-CMAQ, Photochemically active region

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Tropospheric ozone (O3) pollution is of great concern due to its adverse effects on human health, vegetation growth, and climate change (Swackhamer, 1993; Ainsworth et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2016; Westervelt et al., 2019). In the troposphere, O3 is generated by a series of photochemical reactions between its precursors, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and nitrogen oxides (NOx, sum of nitric oxide (NO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2)), under conducive meteorological conditions such as high temperature, strong solar radiation, weak winds, and stable atmospheric boundary layer Logan (1989). Reduction of O3 should be achieved by emission controls on VOCs, NOx, or both.

However, due much to the complex chemical reactions leading to O3 formation, O3 responses nonlinearly to precursor changes under different O3 formation regimes Sillman (1999). For instance, when O3 forms in a VOC-limited regime, VOCs control decreases O3 level while NOx reduction would lead to O3 increase, so-called ‘NOx disbenefits’, due to the reduced titration in removing O3. Significant increases in O3 mixing ratio and atmospheric oxidation capacity in response to the sharp decrease of NOx emissions in the recent Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak over northern China provided a perfect illustration on NOx disbenefits under a VOC-limited regime (Huang et al., 2020; Le et al., 2020; Sicard et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). The maximum daily 8 h average (MDA8) O3 concentration had increased by 18% over the PRD due to the COVID-19 lockdown in China (Zhao et al., 2020).

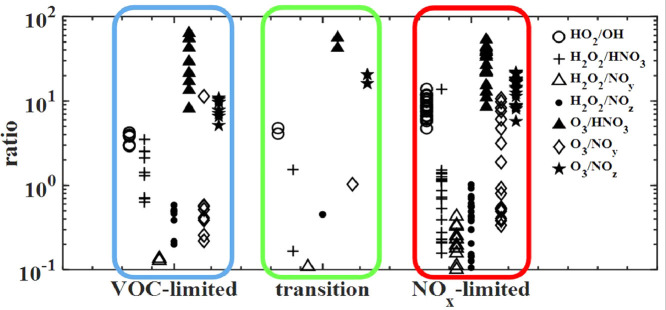

Extensive studies have been conducted to investigate O3-precursor nonlinearity using different methods, including photochemical indicators (e.g. Sillman et al., 1990; Sillman, 1995; Kleinman et al., 1997; Jaeglé et al., 1998), Observation-Based Model (OBM) (e.g., Cardelino and Chameides, 1995; Kumar and Russell, 1996; Cheng et al., 2010), and Emission-Based Model (EBM) (e.g., Ou et al., 2016; Sharma and Khare, 2017). Due much to its simplicity, the photochemical indicator approach has been widely applied to identify O3 formation regimes. A series of photochemical indicators were proposed and their values quantified to separate O3 formation regime into VOC-limited and NOx-limited, including but not limited to, VOCs/NOx ratio of 8 (Sillman, 1995; Sillman, 1999), H2O2/HNO3 of 0.07–0.3 and O3/NOy of 4–6 (Sillman and He, 2002), O3/HNO3 of 2, O3/NOz of 18–22 and H2O2/HNO3 of 2.5–3 Jiménez and Baldasano (2004), and H2O2/HNO3 of 0.2–2.4 (Liu et al., 2010). Note that a majority of these indicators were derived from routinely monitored pollutants due to the availability of monitoring data. Although simple and direct, they cannot delineate the complex photochemical process leading to O3 formation, posing adverse impact on the accuracy of indicating O3 formation regime. The role of atmospheric oxidation, the core driver of O3 formation, was largely neglected.

Atmospheric oxidation plays a critical role in O3 and secondary fine particles production. The hydroxyl radical (OH) and hydroperoxyl radical (HO2), called HOx, are commonly used to characterize atmospheric oxidation. A series of studies have been performed to investigate the relationship between atmospheric oxidation and O3 production (e.g. Monks, 2005; Mao et al., 2010; Ren et al., 2013). Previous studies have demonstrated that HO2 oxidizing NO to produce NO2 dominates O3 production in late spring and summer of 2003 at Waliguan of China (Xue et al., 2013), and higher O3 production was generally associated with greater OH production in the summer of 2006 at Houston (Mao et al., 2010). Although the impact of the atmospheric oxidation on O3 production have been extensively studied, the impacts of atmospheric oxidation on O3-precursor nonlinearity and O3 formation regimes, the essential indicators for O3 pollution control, remain a large knowledge gap.

In this study, we selected Pearl River Delta (PRD) of China as our research target area to investigate the interplay between atmospheric oxidation and O3-precursor nonlinearity. Located in southern China, PRD is one of the most photochemically active regions in the world due to its warm weather, strong solar radiation and intense VOCs and NOx emissions attributed to rapid urbanization and industrialization (Chan and Yao, 2008; Lu et al., 2019). PRD has been suffering from significant and worsening O3 pollution. The annual 90th percentile of MDA8 O3 concentration had increased by 2.1% per year since 2013 and reached 176 µg/m3 in 2019, exceeding the national tier-II standard of 160 µg/m3. Such a dramatic increase is largely driven by the high oxidative capacity over the region. OH and HO2 average concentration of 0.63 pptv and 63 pptv, respectively, were measured in the summer of 2006 (Hofzumahaus et al., 2009), which are the highest OH and HO2 levels ever recorded in the world. Such a high HOx radical concentration poses great challenges on O3 control, and may potentially impact O3 formation regime. Studies showed that PRD was generally in a VOC-limited regime, but with significant diurnal and inter-episode variations (Zhang et al., 2008; Shao et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2011; Li et al., 2013; Zou et al., 2015). In general, VOCs control is the most effective way to reduce peak O3 levels but a shift to NOx-limited regime with stringent NOx control is required for O3 attainment in the long term (Ou et al., 2016). Hence, the mechanism of atmospheric oxidation, especially the role of HOx radicals in shaping O3 formation regimes over the PRD, deserves detailed investigation.

In this study, we applied a two-way coupled Weather Research and Forecasting – Community Multi-scale Air Quality (WRF-CMAQ) modeling system to investigate the relationship between oxidative capacity and O3 formation regime in September 2017, a month with long-lasting O3 pollution episode over the PRD. Emission reduction scenario analysis was performed to identify the O3 formation regime on each day. We demonstrated that HO2/OH is a better indicator for O3 formation regime in the PRD, and process analysis (PA) can explain the underlying reasons of the relationship between HO2/OH ratio and O3 formation regime. We thereby recommended using the HO2/OH ratio for signaling O3 control strategies over the PRD and other photochemically active regions worldwide alike.

1. Methodology and data

1.1. Modeling system and configurations

The version 5.0.2 of WRF-CMAQ modeling system was used in this study. The modeling domains were configured using the Lambert projection, with a triple-nested grid centered at 28.5°N 114°E and two true latitudes for the projection at 15°N and 40°N as the basic projected coordinate. In order to avoid interference of meteorological boundary fields during model simulation, the WRF simulation domain (Table S1) was slightly larger than the CMAQ simulation domain (Table S2 and Fig. S1a). The outermost domain (D1) covers much of East Asia, Southeast Asia and the northwestern Pacific with a resolution of 27 km, the middle domain (D2) covers most of Guangdong province with a resolution of 9 km, and the innermost domain (D3) covers most of the PRD region with a resolution of 3 km. There are 46 vertical levels from surface to the 50-hPa level. The height of the lowest vertical layer is about 44 m above the ground level.

In WRF simulation, the Final Operational Global Analysis data (FNL) at an interval of 6 h with the horizontal resolution of 1° × 1° provided by the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) were used for initial and boundary conditions. The land use data was retrieved from Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) observation. The specific WRF parameterization scheme can be found in Table S3.

Anthropogenic emissions in Guangdong Province were generated based on the 2017 latest emission inventory and transformed by the SMOKE-PRD emission processor into hourly gridded model-ready emission data to be used in the WRF-CMAQ modeling system. This localized inventory included emissions from sources of power plants, fixed combustion, on-road mobile, shipping, industrial process, solvent-use, and biomass burning, for pollutants of sulfur dioxide (SO2), carbon monoxide (CO), NOx, anthropogenic VOCs (AVOCs), black carbon (BC), organic carbon (OC) and particulates (PM10 and PM2.5). Biogenic VOCs (BVOCs) emissions were calculated by the Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature (MEGAN) (Guenther et al., 2012). Multi-resolution Emission Inventory for China (MEIC) Model with a 1° × 1° resolution (http://www.meicmodel.org/) and Regional Emission inventory in Asia (REAS) with a 0.25° resolution were adopted for areas in D1 and D2 outside Guangdong (Zhang et al., 2009; Kurokawa et al., 2013).

In CMAQ simulation, CB-05 gas-phase chemical mechanism and AE5 aerosol mechanism were used. Also incorporated in the CMAQ model were JRPRC module for clear-sky photolysis rate calculation, initial condition (ICON) module for initial chemical conditions, boundary condition (BCON) module for dynamic boundary conditions of the modeling domain, and CCTM module for continuous atmospheric chemical simulation. The specific CMAQ information can be obtained from Ou et al. (2016). Simulation was conducted for the entire month of September 2017 with significant O3 pollution. The first three-day simulation was treated as spin-up time and the model outputs were not included in the analysis.

The hourly observations on atmospheric temperature, wind speed and O3 concentration at seven sites across the PRD, including Jiangmen, Foshan, Guangzhou, Zhuhai, Shenzhen, Zhongshan, and Huizhou, were used to evaluate model performance on replicating meteorological variables and ambient O3 level. Fig. S1b shows the geographical locations of the seven sites. Correlation coefficient (R) and mean bias (MB) between observed and simulated values were calculated, as shown in Tables S4 and S5.

1.2. Identification of O3 formation regime

As shown in Fig. S2, an emission reduction matrix, including 1 base case and 39 emission reduction scenarios with AVOCs and NOx emission reductions in various degrees (% change in gram), was designed to examine O3 changes in response of AVOCs and NOx reductions (Kinosian, 1982; Ou et al., 2016). Emission reductions were only conducted for D3, and only AVOCs were considered as BVOCs emissions are uncontrollable. O3 isopleth diagrams were plotted by interpolating O3 concentrations at different AVOCs and NOx reductions and were used to identify O3 formation regime on each day in September 2017.

In order to quantitatively identify O3 formation regime, we calculated T which is the ratio between O3 change in response to 10% reduction of NOx emission and that in response to 10% reduction of AVOCs emission. A T value less than 0.5 indicates AVOCs-limited O3 formation regime, 0.5 to 2 for a transitional regime, and higher than 2 for a NOx-limited regime (Sillman and West, 2009; Li et al., 2018).

1.3. Process analysis

We applied PA to estimate contributions to a particular species from different physical and chemical processes at each integration time step over each grid (Zhao et al., 2019). The WRF-CMAQ model calculates the time rates of change in chemical species concentrations (ci) by using the following mass continuity equation,

| (1) |

u, v, and w denote the components of wind speed in the three directions, respectively, and Ke is turbulent diffusivity. The seven terms on the right-hand side in Eq. (1) represent horizontal advection, vertical advection, vertical diffusion, cloud processes, chemical reactions (R), dry deposition (D), and source emission rate (E), respectively. PA was performed over D3 at 11:00–16:00 every day when O3 peaks occurred Liu and Roy (2015).

1.4. Indicator evaluation metrics

In this section, we developed a method to evaluate the performance of indicators in distinguishing O3 formation regime. By identifying the O3 formation regime and indicator values on each day of September 2017, we may calculate the value ranges of all indicators under the three O3 formation regimes in the entire month. The performance of indicators was evaluated by two factors, the percentage of overlap between the three regimes and the number of the days in the overlap. The percentage of overlap, P, for a specific indicator was quantified using the following equation:

| (2) |

where, O max and O min represent the maximum and minimum value of the overlap range, and T max and T min denote the maximum and minimum value of the indicator, respectively. The smaller the percentage of overlap and the number of days in the overlap are, the better the indicator in distinguishing O3 formation regimes.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. General characteristics of O3 episode in September 2017

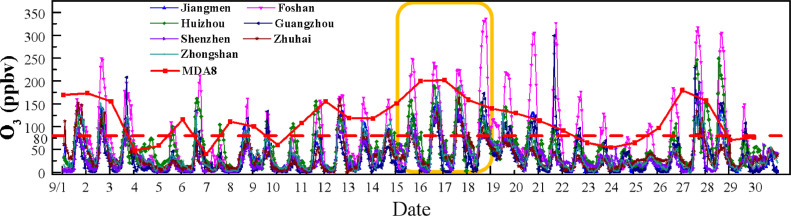

Fig. 1 depicts the hourly averaged O3 concentrations at the seven sites over the PRD during September 2017. There were 21 days with MDA8 O3 concentration over the national tier-II standard of 160 µg/m3 (∼80 ppbv), indicating a continuous and long-lasting O3 elevation event. The most significant O3 episode occurred during 15–19, with the MDA8 O3 exceeding 200 ppbv at some stations. The highest hourly O3 concentration of 336 ppbv was recorded at Foshan on 18. This O3 episode was associated with three synoptic patterns, i.e., approaching of a tropical cyclone on 15–16, eastward movement of a high pressure ridge on 17, and extension of Western Pacific Subtropical High (WPSH) on 18–19, as shown in the weather maps of Fig. S3 (Jian et al., 1998; Shen et al., 2015). On 15-16 when a tropical cyclone was located 500-800km to the PRD, PRD was controlled by the subsidence air in the outskirt of the tropical cyclone, leading to strong solar radiation, high temperature and a stabilized atmospheric structure. The background winds were weak and the dispersion capacity was largely hindered, favoring local pollutant accumulation and photochemical reaction. On 17 when PRD was located in front of a ridge, the coupling between upper-level convergence and low-level divergence led to vertical downward movement, which favored transport of O3 from upper level. On 18-19, PRD was gradually controlled by the westward extension of WPSH. Located between WPSH and a low pressure system over Gulf of Tonkin, PRD was prevailed by easterly wind due to pressure gradient, favoring horizontal O3 transport.

Fig. 1.

Time series of observed hourly O3 concentration (thin line) and averaged 8-h maximum O3 concentration (red thick line) in September 2017. The O3 episode during 15-19 is highlighted in a yellow box. (red dashed line: the national tier-II standard of 80 ppbv).

We conducted meteorology and O3 simulations for the entire September. In terms of meteorology, better model performance in temperature than wind speed simulation was discovered, as shown in Table S4. Relatively poorer simulation of wind speed was largely due to the kind of outdated land use information which cannot well capture land use changes in the rapid urbanization process in the past decade. A comparison between O3 observations and simulation is presented in Fig. S4, and the statistics is provided in Table S5. Overall, the model had a good performance in O3 simulation, with correlation coefficient (R) of 0.71 and mean bias (MB) of 4.7, which were well above the recommended values by US EPA (Emery et al., 2017). The model was able to capture diurnal variation of O3 at different sites, but underestimated O3 peak levels during O3 episode and overestimated O3 levels at night. The under-prediction of O3 peaks during daytime is mainly related to the uncertainties of emissions and over-predicted wind speed (Zhao et al., 2019). The nighttime over-predictions of surface O3 might be collectively caused by inaccuracies in nighttime NO3 chemistry Dimitroulopoulou and Marsh (1997) and meteorological inputs such as boundary layer height and vertical motion (Zhao et al., 2019), as well as uncertainties in emissions of O3 precursors.

2.2. Atmospheric oxidation during O3 episode

As explained in Section 1, HOx radicals play a critical role in atmospheric oxidation and O3 production. In this section, we investigated the relationship between HOx radicals and O3 budget.

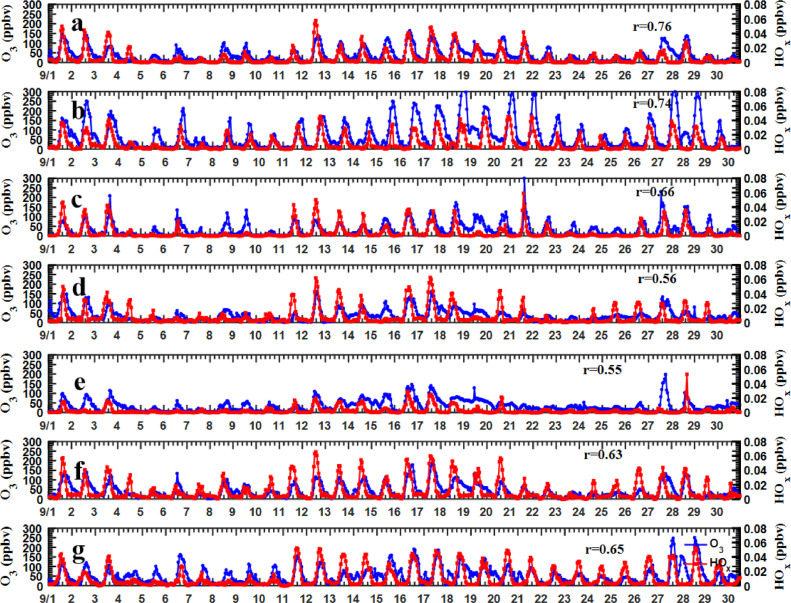

Fig. 2 compares simulated HOx with observed O3 concentrations during the entire month of September 2017. The simulated daily peak OH and HO2 values were in the range of 0.15-0.65 pptv and 21-65 pptv, respectively, during the entire month of September 2017. Due much to the fact that the OH and HO2 observational data is very scarce, we further compare the CMAQ-simulated concentrations of HOx radicals with a set of earlier studies (Hofzumahaus, et al., 2009; Mao et al., 2010; Ren et al., 2013), as shown in Fig. S5. A similar diurnal variation with same magnitude of HOx radicals was found. The results indicate that the model was comparable to those published. These values were higher than those in the other regions worldwide, such as 0.6 pptv for OH and 40 pptv for HO2 in Houston and 0.35 pptv for OH and 10 pptv for HO2 in New York City (Ren et al., 2013; Mao et al., 2010), and were comparable with those observed over the PRD in the summer of 2006 (Hofzumahaus et al., 2009). Diurnally, both OH and HO2 had maxima in the afternoon with peaking time around 14:00-16:00 and minima at night. Day-to-day co-variations between HOx and O3 concentrations can be also noticed. Correlation coefficients were higher than 0.55 at all sites.

Fig. 2.

Time series of simulated HOx (red) and observed O3 (blue) concentrations at (a) Jiangmen, (b) Foshan, (c) Guangzhou, (d) Zhuhai, (e) Shenzhen, (f) Zhongshan, and (g) Huizhou during September 2017.

Similar spatial distributions of HOx and O3 concentrations was also revealed, as shown in Fig. S6 using the 15-19 episode as an example. A HOx and O3 concentration hotspot was noted over central PRD, which further indicated that HOx radicals play a critical role in O3 production. In addition, a clear relationship between large-scale circulation and accumulation and transport of O3 was noticed. On 15-16, typhoon Taili in the South China Sea brought about stabilized atmospheric structure, weak surface winds, strong solar radiation and high temperature over the PRD, which were conducive to the formation and accumulation of O3. Afterwards, a northward movement of O3 and HOx hotspot areas from central PRD were noticed, which corresponded to the eastward movement of a strengthened ridge on 17 and extension of WPSH on 18-19. Thus, the strengthened O3 and HOx episode over the PRD were mainly driven by the variation of large-scale circulation.

2.3. Impact of atmospheric oxidation on O3 formation regimes

In the previous section, we discovered a clear connection between atmospheric oxidation and O3 production over the PRD. The O3 production rate is essentially driven by the production rate of NO2 which is closely associated with two main reactions (HO2 + NO and RO2 + NO). When O3 formation is in the VOC-limited regime, higher amount of HOx favors transformation from NO to NO2, accelerating NOx cycle and leading to O3 formation. Abundant NO is ready to convert HO2 to OH, lowering HO2/OH ratio. In the NOx-limited regime, OH reacts with VOCs to produce organic peroxy radicals (RO2). RO2 oxidizes NO to produce NO2, and the photolysis of NO2 produces O atom and further reacts with O2 to form O3. Excessive HO2 radical is generated by the RO+O2 and OH+VOCs reactions, elevating HO2/OH ratio. Thus, we expect that the HO2/OH ratio have a close relationship with O3 formation regime, which is examined in this section.

By doing a set of sensitivity study described in Section 2.2, we developed O3 isopleth diagram to identify O3 formation regime at different sites over the PRD. The shapes of O3 isopleths varied greatly on the different days, indicating varied O3 formation regimes under the base condition. For example, at Zhuhai site during the 15-19 episode, O3 formation regime fluctuated between VOC-limited, and NOx-limited regimes, as illustrated in Fig. S7. This highlighted significant variation in O3 formation mechanisms over the PRD, even within a single O3 pollution event.

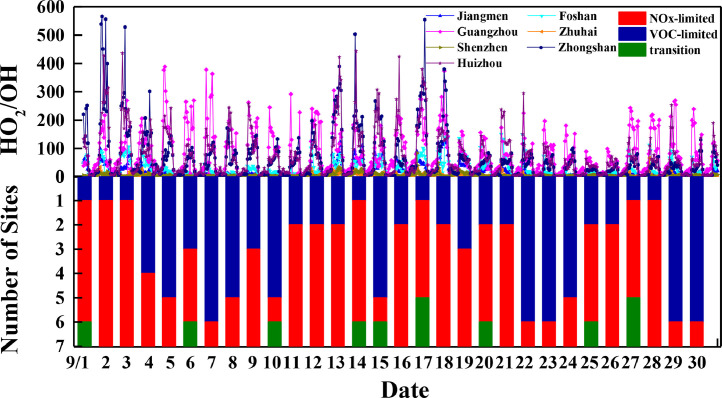

We further examined the co-variations of HO2/OH and O3 formation regime during the entire month of September. A clear correspondence was found, as shown in Fig. 3 . As expected, HO2/OH was higher when O3 formation regime shifted to NOx-limited and lower when O3 formation regime shifted to VOC-limited. However, there was a spatial heterogeneity of HO2/OH threshold ratios for O3 formation regime differentiation, as indicated in Table 1 . The cities were generally split into two clusters, with Huizhou, Zhongshan, Shenzhen and Zhuhai having HO2/OH threshold values around 9–12 and Guangzhou, Jiangmen and Foshan around 5–6. The mis-matching ratios of VOC- and NOx-limited regimes inferred from HO2/OH ratios and scenario analysis were less than 16%, indicating HO2/OH is a good indicator for O3 formation regime. The mis-matching ratios of transitional regime were a bit higher due much to the limited number of days falling within this regime.

Fig. 3.

Time series of HO2/OH ratio at each site (curve) and number of sites in three O3 formation regimes (bar) during September 2017. Bars in red, green and blue represent NOx-limited, transitional, and VOC-limited regime, respectively.

Table 1.

Distribution of HO2/OH values for different O3 formation regime and the percentages of mis-matches during the entire month

| Site | NOx-limited | Transitional | VOC-limited |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jiangmen | >5.5 (12%) | 5-5.5 (0%) | <5 (9%) |

| Foshan | >5.2 (5%) | 4.2-5.2 (50%) | <4.2 (0%) |

| Guangzhou | >2.5 (0%) | 2-2.5 (50%) | <2 (16%) |

| Zhuhai | >10 (14%) | 9.5-10 (25%) | <9.5 (8%) |

| Shenzhen | >10 (0%) | 9.7-10 (0%) | <9.7 (0%) |

| Zhongshan | >10.8 (8%) | 9.9-10.8 (0%) | <9.9 (0%) |

| Huizhou | >12 (0%) | 10-12 (0%) | <10 (0%) |

To better identify the underlying reason for the spatial heterogeneity of HO2/OH threshold ratios for O3 formation regime, we further investigated the spatial distribution of NOx and VOC emissions over the PRD, as shown in Fig. S8. We noticed that these three sites (ie. Jiangmen, Foshan, and Guangzhou) located at red hotspot area with the NOx emission intensity of 0.20, 0.32, and 0.25 mole/sec, respectively (Table S6). For the other four sites, relatively lower NOx emission intensity was found (0.08 mole/sec for Zhuhai, 0.10 mole/sec for Shenzhen, 0.11 mole/sec for Zhongshan, and 0.03 mole/sec Huizhou). Previous studies have demonstrated that the model always underestimated HO2 at high NO levels in most ground-based campaigns, which may cause a lower HO2/OH ratio over central and western PRD (Martinez et al., 2003; Ren et al., 2006). Ren et al., (2003) also noticed a similar under-predicted HO2 under high NO concentration with NCAR chemical ionization mass spectrometer (CIMS). Their results further proved that the uncertainties in the model at high NOx is responsible for the under-predicted HO2.

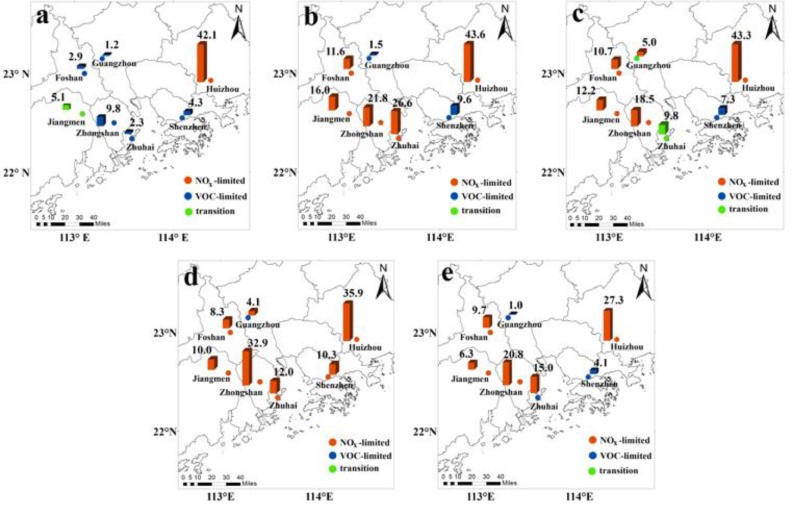

We further compared O3 formation regimes estimated by both HO2/OH ranges listed in Table 1 and scenario analysis during the 15–19 episode, as shown in Fig. 4 . Good consistency in O3 formation regimes were discovered. This highlighted the powerfulness of using HO2/OH to indicate O3 formation regime, even in the context of drastically changing O3 formation mechanisms as a result of a wide span of large-scale circulation patterns occurred during this episode. Only exceptions were revealed at Guangzhou on 17 and 18 and Zhuhai on 19 when HO2/OH and scenario analysis inferred different O3 formation regimes. HO2/OH indicator suggested NOx-limited regime for all three cases while scenario analysis estimated transitional on 17 at Guangzhou and VOC-limited on 18 at Guangzhou and 19 at Zhuhai. We will examine the underlying reason for such discrepancies in the following section.

Fig. 4.

Spatial distribution of O3 formation regime and HO2/OH ratio at 7 sites on (a) 15, (b) 16, (c) 17, (d) 18 and (e) 19 September. Bars in red, green and blue represent NOx-limited, transitional, and VOC-limited regime, respectively, based on the HO2/OH ranges listed in Table 1. Numbers above the bars are the corresponding HO2/OH ratios. Points in red, green and blue represent NOx-limited, transitional, and VOC-limited regime identified by sensitivity analysis, respectively.

2.4. Identification of underlying reasons of the relationship between O3 formation and atmospheric oxidation

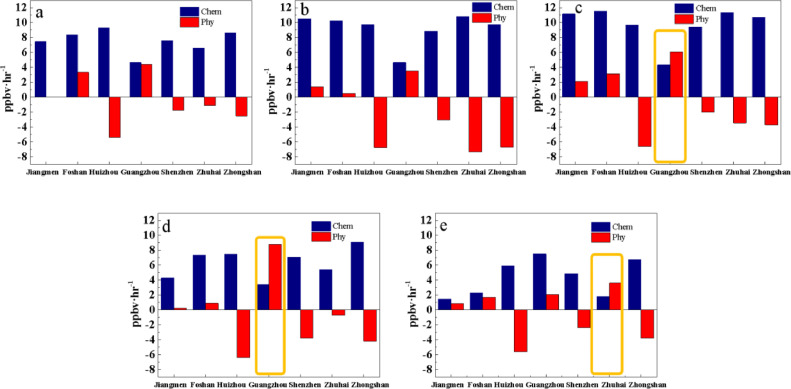

To better identify the underlying factors for the relationship between HO2/OH and O3 formation regime, we performed PA to retrieve physical and chemical contributions to O3 increase during the 15-19 episode, as listed in Table 2 . The PA results listed in Table 2 represent a domain average. Chemical processes contributed predominantly to O3 increase on all days, as a result of favorable meteorological conditions. Physical processes, including horizontal transport and vertical advection, posed substantially less or even negative contributions to O3 increase.

Table 2.

Contribution of physical and chemical processes to O3 increase during 15-19 September

| Date | Physical process (ppbv/hr) | Chemical process (ppbv/hr) | Net (ppbv/hr) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15 Sep | 1.0 | 5.9 | 6.9 |

| 16 Sep | -0.5 | 8.3 | 7.8 |

| 17 Sep | -1.5 | 8.7 | 7.2 |

| 18 Sep | -0.2 | 6.1 | 5.9 |

| 19 Sep | 0.7 | 4.2 | 4.9 |

We further investigated physical and chemical contributions to O3 changes at each site during this episode, as shown in Fig. 5 . The PA results presented in Fig. 5 represent a closest grid to each site. We noticed that overall, chemical reaction contributed predominantly to O3 changes. Exceptional cases with higher physical than chemical contributions, i.e. Guangzhou on 17 and 18 and Zhuhai on 19, are highlighted by yellow boxes. Interestingly, these three cases coincided exactly with those having discrepancies in O3 formation regimes inferred by HO2/OH and scenario analysis. This likely indicated a causal relationship between greater physical contribution and discrepancies in O3 formation regimes. Extending this analysis to the entire September, we found that about 95% (18 out of 19) of discrepancy cases were associated with larger physical than chemical contributions, which gave further weight to the causal relationship. As an indicator essentially delineating atmospheric oxidation capacity, HO2/OH is theoretically associated with O3 that is produced by chemical reactions. Substantial transport of O3 would change the O3-precursor nonlinearity, thereby negating the linkage between HO2/OH and O3 formation regime. As only 9% (19 out of 210) of cases with higher physical than chemical contributions in the entire month, we still believe HO2/OH is a good indicator in signaling O3 formation regime over the PRD. Our results also underscored the necessity in conducting more simulations to quantify the threshold of HO2/OH indicator at sites where physical process had greater contribution to O3 changes.

Fig. 5.

Physical and chemical contributions to O3 changes on (a) 15, (b) 16, (c) 17, (d) 18, and (e) 19 September at the seven sites across the Pearl River Delta retrieved by process analysis. Cases with discrepancies in O3 formation regimes inferred by HO2/OH and scenario analysis are highlighted in yellow boxes.

Physical processes, including horizontal transport and vertical advection, contribute to O3 changes and impact O3 formation regime at a particular area. To better identify the proportion of the contribution of horizontal transport and vertical transport varies under different synoptic circulation types, we further calculated contributions of horizontal transport and vertical transport in the mis-matching cases. On 17 at Guangzhou, the contributions of horizontal and vertical transport to surface O3 were -12 and 18.1 ppbv/hr, respectively. Significant contribution from vertical transport was caused by subsidence of air from the upper-layer. Conversely, horizontal transport played a positive role to O3 with average contributions of 19 ppbv/hr on 18 at Guangzhou and 13 ppbv/hr on 19 at Zhuhai, while vertical transport was negative. Contribution of horizontal transport indicated that a large amount of O3 from the upwind area were transported to Guangzhou and Zhuhai through easterly winds. Our analysis revealed that horizontal and vertical transport contributed differently in the mis-matching cases under different large-scale circulation types, which indicated that the large-scale circulation played an important role in shaping O3 formation regime over the PRD.

Since a few uncertainties remain in HO2/OH indicator, a long-period simulation together with more observations are needed to quantify the threshold of HO2/OH indicator in different sites. Besides, the results also indicate the great importance of promoting measurement of atmospheric radicals to gain insight in atmospheric processes leading to O3 pollution.

2.5. Comparison between HO2/OH and other indicators in indicating O3 formation regime

In this section, we compared the performance of a series of photochemical indicators with a same criterion at each site, including HO2/OH, H2O2/HNO3, H2O2/NOy, H2O2/NOz, O3/HNO3, O3/NOy and O3/NOz, in indicating O3 formation regimes. First, we developed O3 isopleth diagram to identify O3 formation regime at different sites over the PRD as described in Section 2.2. Second, we investigate the distribution of the ratio of each indicator under the three O3 formation regimes. And finally, as described in Section 2.4, the percentage of overlap and the number of the days in the overlap were used to evaluate the performance, as listed in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Percentage of overlap and number of the days in the overlap for all indicators at the seven sites across the Pearl River Delta

| Site | HO2/OH | H2O2/HNO3 | H2O2/NOy | H2O2/NOz | O3/HNO3 | O3/NOy | O3/NOz |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jiangmen | 2.7% (5) | 49.9% (28) | 36.3% (23) | 48.9% (25) | 66.9% (29) | 98.6% (28) | 37.5% (21) |

| Foshan | 0.3% (2) | 24.5% (29) | 30.3% (19) | 55.0% (25) | 46.6% (28) | 100% (30) | 87.6% (26) |

| Guangzhou | 56.3% (13) | 100% (30) | 88.6% (26) | 100% (30) | 99.2% (29) | 97.1% (29) | 49.1% (24) |

| Zhuhai | 34.8% (20) | 100% (30) | 100% (30) | 65.6% (29) | 38.2% (28) | 89.3% (27) | 47.7% (26) |

| Shenzhen | 0% (0) | 93.7% (23) | 60.9% (12) | 94.9% (25) | 85.5% (18) | 60.5% (8) | 86.4% (20) |

| Zhongshan | 10.4% (5) | 15.9% (23) | 64.3% (25) | 52.4% (25) | 4.0% (15) | 100% (30) | 10.5% (15) |

| Huizhou | 0% (0) | 65.7% (28) | 24.5% (11) | 7.5% (11) | 43.0% (29) | 99.3% (29) | 6.7% (6) |

It is noted that at Jiangmen, Foshan, Zhuhai, Shenzhen and Huizhou, HO2/OH showed the best performance with the lowest percentage of overlap and the number of the days in the overlap. In particular, there was no overlap at Shenzhen and Huizhou, meaning HO2/OH can indicate O3 formation regimes with 100% accuracy. At Guangzhou and Zhongshan, although the percentage of overlap of HO2/OH was the second lowest (56.3% for HO2/OH vs. 49.1% for O3/NOz at Guangzhou and 10.4% for HO2/OH vs. 4.0% for O3/HNO3 at Zhongshan), the number of days was the lowest and much smaller than the second lowest value (13 for HO2/OH vs. 24 for O3/NOz at Guangzhou and 5 for HO2/OH vs. 15 for O3/HNO3 and O3/NOz at Zhongshan).

Therefore, we believe HO2/OH is the best indicator to distinguish O3 formation regimes over the PRD. This also highlights the fact that atmospheric oxidation is the core driver of O3 formation regimes in a photochemically active region. Using HO2/OH to identify O3 formation regimes circumvents the time-consuming sensitivity analysis by numerical models which very often involves tens of scenarios, thereby providing a simple and direct way for fast identification of O3 formation regimes which is essential to formulate contingency control strategies to mitigate O3 pollution during episode.

3. Conclusions

PRD has been suffering from significant and worsening O3 pollution which is largely driven by the high oxidative capacity over the region. A set of studies have been performed to investigate the impact of the atmospheric oxidation on O3 production, but the impacts of atmospheric oxidation on O3-precursor nonlinearity and O3 formation regimes, the essential indicators for O3 pollution control, still remain a large knowledge gap. In this study, a comprehensive air quality model (WRF-CMAQ) was used to investigate the relationship between atmospheric oxidation and O3 formation regimes during the entire month of September 2017 with 21 days with MDA8 O3 concentration over the national tier-II standard.

A detailed investigation of the mechanism of atmospheric oxidation, especially the role of HOx radicals in shaping O3 formation regimes is required over the PRD. We discovered a clear relationship between oxidative capacity and O3 formation regime over the PRD. The O3 formation is dominated by NOx-limited regime when the HO2/OH ratio is approximately higher than 11 and lower than 9.5 when dominated by VOC-limited over eastern PRD. Over central and western PRD, an HO2/OH ratio higher than 5 and lower than 2 was indicative of NOx-limited and VOC-limited regime, respectively.

PA results denote that the HO2/OH indicator exhibits a good performance on O3 formation judgment when the chemical reaction contributed predominantly to O3 changes. Physical contribution, including horizontal transport and vertical transport, may pose uncertainties on the indication of O3 formation regime by HO2/OH ratio. Substantial transport of O3 would change the O3-precursor nonlinearity, thereby negating the relationship between HO2/OH and O3 formation regime. As only 9% of cases with higher physical than chemical contributions in the entire month, we believe HO2/OH is a good indicator in signaling O3 formation regime over the PRD. In comparison with other commonly used photochemical indicators, the HO2/OH indicator showed a lower range of the percentage of overlap and the limited number of the days in the overlap at each site. Thus, HO2/OH ratio had the best performance in differentiating NOx-, transition, and VOC-limited regimes.

Due much to the fact that the observational data of HO2 and OH is very scarce, we would currently recommend using the model simulation to obtain the HO2/OH ratio. Although there are some uncertainties in simulation results, it is a simple and direct way for fast identification of O3 formation regimes.

This study has an important implication on understanding the relationship between atmospheric oxidation and O3 formation regimes during O3 episodes. Using HO2/OH to identify O3 formation regimes circumvents the time-consuming sensitivity analysis by numerical models, thereby providing a simple and direct way for fast identification of O3 formation regimes which is essential to formulate contingency control strategies to mitigate O3 pollution during episode. The results also underscored the importance of characterizing behaviors of radicals to gain insight in atmospheric processes leading to O3 and other secondary pollution over a photochemically active region.

Acknowledgement

This work is sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 91644221, 41575009).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jes.2020.09.038.

Appendix B. Supplementary materials

References

- Ainsworth E.A., Yendrek C.R., Sitch S., Collins W.J., Emberson L.D. The effects of tropospheric ozone on net primary productivity and implications for climate change. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 2012;63:637–661. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardelino C.A., Chameides W.L. An observation-based model for analyzing ozone precursor relationships in the urban atmosphere. J. Air. Waste. Manag. Assoc. 1995;45:161–180. doi: 10.1080/10473289.1995.10467356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan C.K., Yao X. Air pollution in mega cities in China. Atmos. Environ. 2008;42:1–42. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H., Guo H., Wang X., Saunders S.M., Lam S.H.M., Jiang F., et al. Erratum to: on the relationship between ozone and its precursors in the pearl river delta: application of an observation-based model (OBM) Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2010;17:1491–1492. doi: 10.1007/s11356-010-0347-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitroulopoulou C., Marsh A.R.W. Modelling studies of NO3 nighttime chemistry and its effects on subsequent ozone formation. Atmo. Environ. 1997;31:3041–3057. [Google Scholar]

- Emery C., Liu Z., Russell A.G., Odman M.T., Yarwood G., Kumar N. Recommendations on statistics and benchmarks to assess photochemical model performance. J. Air. Waste. Manage. 2017;67:582–598. doi: 10.1080/10962247.2016.1265027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther A., Jiang J., Heald C., Sakulyanontvittaya Duhl.T., Emmons L., Wang J. The model of emissions of gases and aerosols from nature version 2.1 (MEGAN2.1): an extended and updated framework for modeling biogenic emissions. Geosci. Model Dev. 2012;6:1471–1492. doi: 10.5194/gmd-5-1471-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hofzumahaus A., Rohrer F., Lu K., Bohn B., Brauers T., Chang C.C., et al. Amplified trace gas removal in the troposphere. Science. 2009;324:1702–1704. doi: 10.1126/science.1164566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Ding A., Gao J., Zheng B., Zhou D., Qi X., et al. Enhanced secondary pollution offset reduction of primary emissions during COVID-19 lockdown in China. Natl. Sci. Rev. nwaa. 2020;137 doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwaa137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeglé L., Jacob D.J., Brune W.H., Tan D., Faloona I.C., Weinheimer A.J., et al. Sources of HOx and production of ozone in the upper troposphere over the United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1998;25:1709–1712. [Google Scholar]

- Jian Z., Rao S.T., Daggupaty S.M. Meteorological Processes and Ozone Exceedances in the Northeastern United States during the 12-16 July 1995 Episode. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1998;37:776–789. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez P., Baldasano J.M. Ozone response to precursor controls in very complex terrains: use of photochemical indicators to assess O3-NOx-VOC sensitivity in the northeastern Iberian Peninsula. J. Geophys. Res. 2004;109 doi: 10.1029/2004JD004985. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kinosian R.J. Ozone-precursor relationships from EKMA diagrams. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1982;16:880–883. doi: 10.1021/es00106a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman L.I., Daum P.H., Lee J.H., Lee Y.N., Nunnermacker L.J., Springston S.R., et al. Dependence of ozone production on NO and hydrocarbons in the troposphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1997;24:2299–2302. doi: 10.1029/97GL02279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N., Russell A.G. Comparing prognostic and diagnostic meteorological fields and their impacts on photochemical air quality modeling. Atmos. Environ. 1996;30:1989–2010. doi: 10.1016/1352-2310(95)00179-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa J., Ohara T., Morikawa T., Hanayama S., Greet J.M., Fukui T., et al. Emissions of air pollutants and greenhouse gases over Asian regions during 2000-2008: regional emission inventory in Asia (REAS) version 2. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013;13:10049–10123. doi: 10.5194/acpd-13-10049-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Le T., Wang Y., Liu L., Yang J., Yung Y.L., Li G., et al. Unexpected air pollution with marked emission reductions during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abb7431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Zhang L., Wang T., Wang Z., Fu X., Zhang Q. "New" reactive nitrogen chemistry reshapes the relationship of ozone to its precursors. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018;52:2810–2818. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b05771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Lau A.K.H., Fung J.C.H., Zheng J., Liu S. Importance of NOx control for peak ozone reduction in the pearl river delta region. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013;118:9428–9443. doi: 10.1002/jgrd.50659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Zhang Y., Xing J., Zhang Q., Wang K., Streets D.G., et al. Understanding of regional air pollution over China using CMAQ, part II. Process analysis and sensitivity of ozone and particulate matter to precursor emissions. Atmos. Environ. 2010;44:3719–3727. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.03.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Roy S.S. Spatial patterns of seasonal level diurnal variations of ozone and respirable suspended particulates in Hong Kong. Prof. Geogr. 2015;67:17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Logan J.A. Ozone in rural areas of the United States. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1989;94:8511–8532. [Google Scholar]

- Lu H., Lyu X., Cheng H., Ling Z., Guo H. Overview on the spatial-temporal characteristics of ozone formation regime in China. Environ. Sci. Proc. Impacts. 2019 doi: 10.1039/C9EM00098D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J., Ren X., Chen S., Brune W.H., Chen Z., Martinez M., et al. Atmospheric oxidation capacity in the summer of Houston 2006: comparison with summer measurements in other metropolitan studies. Atmos. Environ. 2010;44:4107–4115. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez M., Harder H., Kovacs T.A., Simpas J.B., Bassis J., Lesher R., et al. OH and HO2 concentrations, sources, and loss rates during the Southern Oxidants Study in Nashville, Tennessee, summer 1999. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2003;108:17. [Google Scholar]

- Monks P.S. Gas-phase radical chemistry in the troposphere. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005;34:376–395. doi: 10.1039/b307982c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou J., Yuan Z., Zheng J., Huang Z., Shao M., Li Z., et al. Ambient ozone control in a photochemically active region: short-term despiking or long-term attainment? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b00345. 6b-345b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X.R., Brune W.H., Mao J.Q., Mitchell M.J., Lesher R.L., Simpas J.B., et al. Behavior of OH and HO2 in the winter atmosphere in New York City. Atmos. Environ. 2006;40:S252–S263. [Google Scholar]

- Ren X.R., Edwards G.D., Cantrell C.A., Lesher R.L., Metcalf A.R., Shirley T., et al. Intercomparison of peroxy radical measurements at a rural site using laser-induced fluorescence and peroxy radical chemical ionization mass spectrometer (PerCIMS) techniques. J. Geophy. Res. Atmos. 2003;108:9. [Google Scholar]

- Ren X., van Duin D., Cazorla M., Chen S., Mao J., Zhang L., et al. Atmospheric oxidation chemistry and ozone production: results from SHARP 2009 in Houston, Texas. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013;118:5770–5780. doi: 10.1002/jgrd.50342. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shao M., Zhang Y., Zeng L., Tang X., Zhang J., Zhong L., et al. Ground-level ozone in the pearl river delta and the roles of VOC and NOx in its production. J. Environ. Manage. 2009;90:512–518. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S., Khare M. Photo-chemical transport modelling of tropospheric ozone: a review. Atmos. Environ. 2017;159:34–54. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2017.03.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L., Mickley L., Tai A. Influence of synoptic patterns on surface ozone variability over the eastern United States from 1980 to 2012. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015;15 doi: 10.5194/acp-15-10925-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sicard P., De Marco.A., Agathokleous E., Feng Z., Xu X., Paoletti E., et al. Amplified ozone pollution in cities during the COVID-19 lockdown. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020;735 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillman S. The use of NOy, H2O2 and HNO3 as indicators for O3-NOx-VOC sensitivity in urban locations. J. Geophys. Res. 1995;100:175–188. [Google Scholar]

- Sillman S. The relation between ozone, NOx and hydrocarbons in urban and polluted rural environments. Atmos. Environ. 1999;33:1821–1845. [Google Scholar]

- Sillman S., He D. Some theoretical results concerning O3‐NOx‐VOC chemistry and NOx‐VOC indicators. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2002;107:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sillman S., Logan J.A., Wofsy S.C. The sensitivity of ozone to nitrogen oxides and hydrocarbons in regional ozone episodes. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1990;95:1837–1851. [Google Scholar]

- Sillman S., West J.J. Reactive nitrogen in Mexico City and its relation to ozone-precursor sensitivity: results from photochemical models. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2009;9:3477–3489. [Google Scholar]

- Swackhamer D.L. Rethinking the ozone problem in urban and regional air pollutionnational research council. national academy press (1991) J. Aerosol. Sci. 1993;24:977–978. [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Chen K., Zhu S., Wang P., Zhang H. Severe air pollution events not avoided by reduced anthropogenic activities during COVID-19 outbreak. Resour. Conserv. Recy. 2020;158 doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zhang Y., Hu Y., Zhou W., Zeng L., Hu M., et al. Decoupled direct sensitivity analysis of regional ozone pollution over the Pearl River Delta during the PRIDE-PRD2004 campaign. Atmos. Environ. 2011;45:4941–4949. [Google Scholar]

- Westervelt D.M., Ma C.T., He M.Z., Fiore A.M., Kinney P.L., Kioumourtzoglou M., et al. Mid-21st century ozone air quality and health burden in China under emissions scenarios and climate change. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019;14:74030. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ab260b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xue L.K., Wang T., Guo H., Blake D.R., Tang J., Zhang X.C., et al. Sources and photochemistry of volatile organic compounds in the remote atmosphere of western China: results from the Mt. Waliguan observatory. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013;13:8551–8567. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Cooper O.R., Gaudel A., Thompson A.M., Nédélec P., Ogino S., et al. Tropospheric ozone change from 1980 to 2010 dominated by equatorward redistribution of emissions. Nat. Geosci. 2016;9:875–879. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.H., Hu M., Zhong L.J., Wiedensohler A., Liu S.C., Andreae M.O., et al. Regional integrated experiments on air quality over pearl river delta 2004 (PRIDE-PRD2004): overview. Atmos. Environ. 2008;42:6157–6173. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Streets D.G., Carmichael G.R., He K.B., Huo H., Kannari A., et al. Asian emissions in 2006 for the NASA INTEX-B mission, Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2009;9:5131–5153. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao K., Bao Y., Huang J., Wu Y., Moshary F., Arend M., et al. A high-resolution modeling study of a heat wave-driven ozone exceedance event in New York City and surrounding regions. Atmos. Environ. 2019;199:368–379. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.10.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.B., Zhang K., Xu X.T., Shen H.Z., Zhu X., Zhang Y.X., et al. Substantial changes in nitrogen dioxide and ozone after excluding meteorological impacts during the COVID-19 outbreak in Mainland China. Environ. Sci. Tech. Let. 2020;7(6):402–408. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y., Deng X.J., Zhu D., Gong D.C., Wang H. Characteristics of 1 year of observational data of VOCs, NOx and O3 at a suburban site in Guangzhou. China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015;15:6625–6636. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.