Abstract

The environment surrounding researchers has changed significantly in the face of COVID-19 restrictions. An online self-reported questionnaire was completed by 10,557 participants between June 15 and 19, 2020. The impact on work/research activities and harassments under COVID-19 conditions was higher among researchers (1963) compared to non-researchers (8572). We further examined the effect of COVID-19 restrictions on 300 researchers. Women were significantly more likely to report being harassed than males. The overall “decrease in research motivation” was higher in women. The restrictions on research activities because of COVID-19 restrictions caused future anxiety and a decrease in research motivation.

Keywords: COVID-19, Researcher, Motivation, Harassment, Disaster science

1. Introduction

The novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19)—which emerged in Wuhan, China, in November 2019—has grown into a global threat and was eventually declared a global pandemic [1]. It has seriously impacted the lives of many and caused numerous deaths. On April 7, 2020, the Japanese Head of the Novel Coronavirus Response Headquarters declared a state of emergency for seven regions including Tokyo [2]; by April 16, the state of emergency expanded across the country [3]. The Japanese government had asked for people to reduce their contact with one another by at least 70% and ideally 80% [2]; business operations and schools were also requested to be temporarily ceased [4]. Entertainment events and meetings were suspended or postponed; the 2020 Summer Olympic Games (scheduled to be held in Tokyo) were no exception [5]. During this period, staying at home and to avoiding unnecessary outings were advisable; several companies also adopted remote and working-from-home strategies. Several industries—such as accommodations, food and beverage services, travel, and amusement services—have suffered significant financial losses because of the suspension of “non-essential” services during the state of emergency to prevent the transmission of the disease [6,7].

For combating COVID-19, Japan implemented social distancing as one of the models; it comprised the “3 Cs” signifying awareness of the following: 1. Closed spaces with insufficient ventilation, 2. Crowded situations, and 3. Conversations held at a short distance [2,4]. In educational settings such as schools, face-to-face lectures are banned as part of the 3 Cs; as a result of these measures, online lectures and classes in Japan are expected to improve [8,9]. Although lockdown and self-restraint (as caused by COVID-19) have induced functional changes in the style of attending class (described above), it is feared that this may have a negative effect on the mental health of the students by restricting their activities both outside and on campus [[10], [11], [12]]. A survey of 66 Chinese college students found that the act of recognizing the threat posed by COVID-19 could lead to negative emotions as a result of poor sleep quality [10]. In a survey of 1000 Greek university students, many participants complained of anxiety and depression because of the COVID-19 quarantine [11]. Moreover, because of the COVID-19 quarantine, there was a 2.5- to 3.0-fold increase in depression, and an almost 8.0-fold increase in suicidal ideation, when compared to the prevalence in the general population [11]. These findings highlight the importance of supporting the mental health of students and to reconsider students' school life activities during the current measures against COVID-19, and to further prepare against the next wave.

The fight against COVID-19 has also affected research activities at universities and institutes, with many scientists having had to stop or limit their research during the pandemic [13]. Research using experimental equipment and reagents so-called wet-lab experimentation cannot be replicated in remote working conditions. Even if scientists can conduct experiments in a laboratory, the threat of the “3 Cs” occurring in the laboratory may increase the risk of novel coronavirus infection. Researchers around the world (including Japan) are always in competition because of the results-based system in which they operate [14] as such, delays in research (because of the restrictive countermeasures applied by governments in battling COVID-19) may lead to greater emotional strain on scientists, manifesting as anxiety and frustration. However, the truth on the matter remains unknown, as there is no survey report focusing on the issue. For a definitive picture, it is necessary to compare the situation before and after the COVID-19 pandemic, but COVID-19 continues to spread without any sign of an end. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to clarify the impact of COVID-19 measures on the research environment and motivation of Japanese scientists during the current pandemic.

2. Materials and methods

The questionnaire survey was outsourced to Cross Marketing Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). Survey targets were extracted from members registered in a monitor member database of Cross Marketing, and the questionnaire survey was conducted by accessing the survey web site of Cross Marketing. For this study, the questionnaire was completed by approximately 10,000 people; in total, we obtained responses from 300 researchers from the 10,000 initial respondents. The survey was conducted for five days – from Monday, June 15, to Friday, June 19, 2020. The questionnaires were filled out anonymously. Documents for obtaining the participants' consent are shown in the Supplementary document. The Ethics Committee of the International Research Institute of Disaster Science, Tohoku University, approved the research protocol of this survey (No. 2020–006). Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) was used to collect and manage the data obtained. Cross Finder 2 (Cross Marketing, Tokyo, Japan) was used for cross-tabulation. A chi-squared test via StatView ver. 5.0 (SAS Institute Inc., USA) was used for comparison between the groups.

3. Results

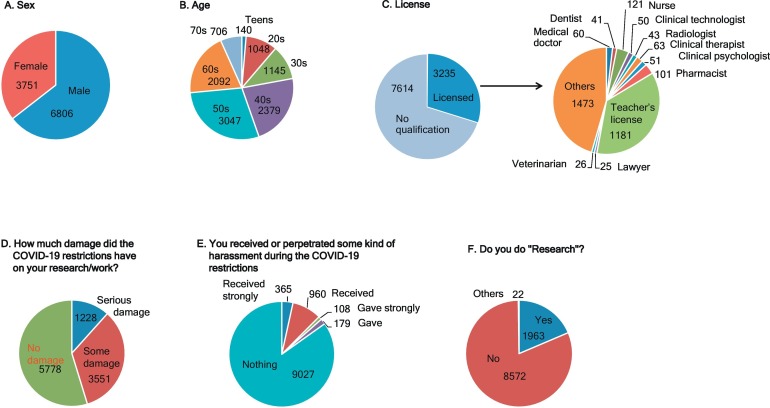

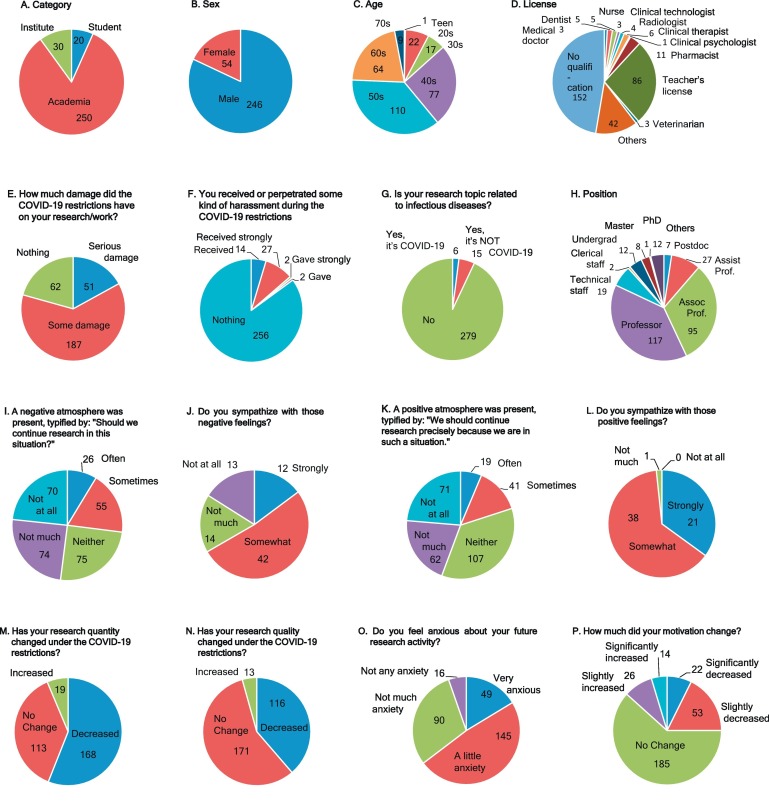

The questionnaire was collected from 10,557 participants. The questions, along with the number of responses from these participants, are summarized in Fig. 1 . The number of people who reported that their work has been negatively affected by measures in combating COVID-19 is 4479 (45.3%) (Fig. 1D). Further, 1325 (12.6%) of respondents felt (at the time of answering) that they had received harassment, while 287 (2.7%) felt that they had been responsible for harassing someone (Fig. 1E). Among the 10,557 respondents, 1963 people replied “Yes” to the question “Do you do ‘research’?”; 8572 replied with a “No,” while 22 answered “Other” (Fig. 1F). In this study, the person who answered “Yes” is defined as a researcher and is further compared to the person who answered “No,” the non-researcher group. Table 1 summarizes the factors with significant differences in this comparison. The number of females in the researcher group was relatively low when compared to the non-researcher group (Table 1). The number of researchers who had their research or working activities affected by COVID-19 countermeasures was higher than that of non-researchers (Table 1). Regarding harassment, the ratio of both those who received it and those who gave it was high among the researchers' group (Table 1). The study also conducted a further detailed survey of 300 of the 1963 researchers. The questions to participants and the number of responses are summarized in Fig. 2 . Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 show the comparisons between groups in which significant differences were recognized. Various comparisons were made with questions other than those provided in Tables 1 and Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, but no significant relationship was found in any of them.

Fig. 1.

Number of responses to each question of 10,557 people surveyed.

Numbers are all people.

Table 1.

Factors that differed between researchers and non-researchers across the 10,535 people surveyed.

| Questions | Category | Do you do “Research”? |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes |

No |

p value | |||||

| 1963 | (%) | 8572 | (%) | ||||

| Sex | Male | 1489 | (75.9) | 5303 | (61.9) | <0.0001 | |

| Female | 474 | (24.1) | 3269 | (38.1) | |||

| How much of an impact did the combating of COVID-19 have on your research environment? | Serious | 382 | (19.5) | 842 | (9.8) | <0.0001 | |

| Some | 1025 | (52.2) | 2519 | (29.4) | |||

| No | 556 | (28.8) | 5211 | (60.8) | |||

| Have you ever felt that you received or perpetrated some kind of harassment during the COVID-19 restrictions? | Strongly received | 139 | (7.1) | 204 | (2.4) | <0.0001 | |

| Received | 303 | (15.4) | 652 | (7.6) | |||

| Did not receive | 1521 | (77.5) | 7716 | (90.0) | |||

| Gave strongly | 27 | (1.4) | 81 | (0.9) | 0.0013 | ||

| Gave | 49 | (2.5) | 126 | (1.5) | |||

| Did not give | 1887 | (96.1) | 8365 | (97.6) | |||

P values were calculated by chi-square test.

Fig. 2.

Number of responses to each question of 300 researchers surveyed.

Numbers are all people.

Table 2.

Gender-related factors present in 300 researchers.

| Questions | Category | Male |

Female |

p value | Category (Large group) | Male |

Female |

p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 246 | (%) | 54 | % | 246 | (%) | 54 | % | |||||

| Have you ever felt that you received some kind of harassment? | Strongly felt | 17 | (6.9) | 10 | (18.5) | 0.0227 | Felt | 28 | (11.4) | 13 | (24.1) | 0.0139* |

| Felt | 11 | (4.5) | 3 | (5.6) | ||||||||

| Others | 218 | (88.6) | 41 | (75.9) | Others | 218 | (88.6) | 41 | (75.9) | |||

| How much did your motivation change? | Significantly decreased | 22 | (8.9) | 0 | (0.0) | <0.0001 | Decreased | 54 | (22.0) | 21 | (38.9) | 0.0296 |

| Slightly decreased | 32 | (13.0) | 21 | (38.9) | ||||||||

| No change | 159 | (64.6) | 26 | (48.1) | No change | 159 | (64.6) | 26 | (48.1) | |||

| Slightly increased | 21 | (8.5) | 5 | (9.3) | Increased | 33 | (13.4) | 7 | (13.0) | |||

| Significantly increased | 12 | (4.9) | 2 | (3.7) | ||||||||

P values were calculated by chi-square test. *Not significant.

Table 3.

Factors related to the effect of COVID-19 measures on the research environment in 300 researchers.

| Questions | Category | Serious |

Some |

No |

p value | Category (Large group) | Serious |

Some |

No |

p value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 51 | (%) | 187 | (%) | 62 | (%) | 51 | (%) | 187 | (%) | 62 | (%) | |||||

| Have you ever felt that you had received some kind of harassment? | Strongly | 3 | (5.9) | 22 | (11.8) | 2 | (3.2) | 0.0208 | ||||||||

| Moderately | 6 | (11.8) | 6 | (3.2) | 2 | (3.2) | ||||||||||

| Others | 42 | (82.4) | 159 | (85.0) | 58 | (93.5) | ||||||||||

| There was a negative atmosphere, typified by the question: “Should we continue research in this situation?” | Often | 8 | (15.7) | 15 | (8.0) | 3 | (4.8) | 0.0008 | Yes | 21 | (41.2) | 53 | (28.3) | 7 | (11.3) | 0.0018 |

| Sometimes | 13 | (25.5) | 38 | (20.3) | 4 | (6.5) | ||||||||||

| Neither | 14 | (27.5) | 47 | (25.1) | 14 | (22.6) | Neither | 14 | (27.5) | 47 | (25.1) | 14 | (22.6) | |||

| Not much | 10 | (19.6) | 50 | (26.7) | 14 | (22.6) | No | 16 | (31.4) | 87 | (46.5) | 41 | (66.1) | |||

| Not at all | 6 | (11.8) | 37 | (19.8) | 27 | (43.5) | ||||||||||

| There was a positive atmosphere, typified by the statement: “We should continue research precisely because we are in such a situation.” | Often | 5 | (9.8) | 6 | (3.2) | 8 | (12.9) | 0.0053 | Yes | 8 | (15.7) | 36 | (19.3) | 16 | (25.8) | 0.6184* |

| Sometimes | 3 | (5.9) | 30 | (16.0) | 8 | (16.0) | ||||||||||

| Neither | 17 | (33.3) | 70 | (37.4) | 20 | (37.4) | Neither | 17 | (33.3) | 70 | (37.4) | 20 | (32.3) | |||

| Not much | 10 | (19.6) | 46 | (24.6) | 6 | (9.7) | No | 26 | (51.0) | 81 | (43.3) | 26 | (41.9) | |||

| Not at all | 16 | (31.4) | 35 | (18.7) | 20 | (32.3) | ||||||||||

| Do you feel anxious about the future of your research activity? | Very | 18 | (35.3) | 29 | (15.5) | 2 | (3.2) | <0.0001 | Yes | 43 | (84.3) | 131 | (70.1) | 20 | (32.3) | <0.0001 |

| A little | 25 | (49.0) | 102 | (54.5) | 18 | (29.0) | ||||||||||

| Not so much | 8 | (15.7) | 53 | (28.3) | 29 | (46.8) | No | 8 | (15.7) | 56 | (29.9) | 42 | (67.7) | |||

| Not any | 0 | (0.0) | 3 | (1.6) | 13 | (21.0) | ||||||||||

| How much has your motivation changed? | Significantly decreased | 13 | (25.5) | 9 | (4.8) | 0 | (0.0) | <0.0001 | Decreased | 20 | (39.2) | 50 | (26.7) | 5 | (8.1) | 0.0004 |

| Slightly decreased | 7 | (13.7) | 41 | (21.9) | 5 | (8.1) | ||||||||||

| No change | 22 | (43.1) | 119 | (63.6) | 44 | (71.0) | No change | 22 | (43.1) | 119 | (63.6) | 44 | (71.0) | |||

| Slightly increased | 4 | (7.8) | 14 | (7.5) | 8 | (12.9) | Increased | 9 | (17.6) | 18 | (9.6) | 13 | (21.0) | |||

| Significantly increased | 5 | (9.8) | 4 | (2.1) | 5 | (8.1) | ||||||||||

How much of an impact (or damage) did the combating of COVID-19 have on (or cause to) your research/work environment?

P values were calculated by chi-square test. *Not significant.

Table 4.

Factors associated with harassment facing COVID-19 measures in 300 researchers.

| Questions |

Category |

Strongly felt |

Felt |

No |

p value |

Category (Large group) |

Strongly felt |

Felt |

Others |

p value |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 |

(%) |

14 |

(%) |

259 |

(%) |

27 |

(%) |

14 |

(%) |

259 |

(%) |

|||||

| a. Factors related to “Receiving Harassment” | ||||||||||||||||

| There was a negative atmosphere | Often | 3 | (11.1) | 6 | (42.9) | 17 | (6.6) | <0.0001 | Yes | 13 | (48.1) | 8 | (57.1) | 60 | (23.2) | 0.0034 |

| Sometimes | 10 | (37.0) | 2 | (14.3) | 43 | (16.6) | ||||||||||

| Neither | 7 | (25.9) | 2 | (14.3) | 66 | (25.5) | Neither | 7 | (25.9) | 2 | (14.3) | 66 | (25.5) | |||

| Not much | 4 | (14.8) | 4 | (28.6) | 66 | (25.5) | No | 7 | (28.9) | 4 | (28.6) | 133 | (51.4) | |||

| Not at all | 3 | (11.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 67 | (25.9) | ||||||||||

| Do you feel anxious about the future of your research activity? | Very | 4 | (14.8) | 9 | (64.3) | 36 | (13.9) | <0.0001 | Yes | 24 | (88.9) | 12 | (85.7) | 158 | (61.0) | 0.0015 |

| A little | 20 | (74.1) | 3 | (21.4) | 122 | (47.1) | ||||||||||

| Not so much | 3 | (11.1) | 2 | (14.3) | 85 | (32.8) | No | 3 | (11.1) | 2 | (14.3) | 101 | (39.0) | |||

| Not any | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 16 | (6.2) | ||||||||||

| How much did your motivation change? | Significantly decreased | 3 | (11.1) | 4 | (28.6) | 15 | (5.8) | <0.0001 | Decreased | 11 | (40.7) | 6 | (42.9) | 58 | (22.4) | 0.0452 |

| Slightly decreased | 8 | (29.6) | 2 | (14.3) | 43 | (16.6) | ||||||||||

| No change | 15 | (55.6) | 8 | (57.1) | 162 | (62.5) | No change | 15 | (55.6) | 8 | (57.1) | 162 | (62.5) | |||

| Slightly increased | 1 | (3.7) | 0 | (0.0) | 25 | (9.7) | Increased | 1 | (3.7) | 0 | (0.0) | 39 | (15.1) | |||

| Significantly increased | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 14 | (5.4) | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Questions |

Category |

Strongly felt |

Felt |

No |

p value |

Category (Large group) |

Strongly felt |

Felt |

Others |

p value |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 |

(%) |

2 |

v(%) |

296 |

(%) |

27 |

(%) |

14 |

(%) |

259 |

(%) |

|||||

| b. Factors related to “Perpetrating Harassment” | ||||||||||||||||

| There was a negative atmosphere | Often | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 26 | (8.8) | 0.0208 | Yes | 2 | (100.0) | 2 | (100.0) | 77 | (26.0) | 0.0270 |

| Sometimes | 2 | (100.0) | 2 | (100.0) | 51 | (17.2) | ||||||||||

| Neither | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 75 | (25.3) | Neither | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 75 | (25.3) | |||

| Not much | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 74 | (25.0) | No | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 144 | (48.6) | |||

| Not at all | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 70 | (23.6) | ||||||||||

| How much did your motivation change | Significantly decreased | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 22 | (7.4) | <0.0001 | Decreased | 2 | (100.0) | 2 | (100.0) | 71 | (24.0) | 0.0452 |

| Slightly decreased | 2 | (100.0) | 2 | (100.0) | 49 | (16.6) | ||||||||||

| No change | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 185 | (62.5) | No change | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 185 | (62.5) | |||

| Slightly increased | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 26 | (8.8) | Increased | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 40 | (13.5) | |||

| Significantly increased | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 14 | (4.7) | ||||||||||

Have you ever felt that you were the victim, or perpetrator, of some kind of harassment in the face of a new coronavirus infection?

P values were calculated by chi-square test.

Table 5.

Factors related to the research area.

| Questions | Category | Education |

Engineering |

Life Science |

Agriculture |

Humanities |

Other Science |

p value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | (%) | 53 | (%) | 50 | (%) | 24 | (%) | 102 | (%) | 41 | (%) | |||

| Have you ever felt that you had received some kind of harassment in the face of the COVID-19 restrictions? | Strongly | 4 | (13.3) | 3 | (5.7) | 5 | (10.0) | 3 | (12.5) | 9 | (8.8) | 3 | (7.3) | 0.0196 |

| Moderately | 1 | (3.3) | 0 | (0.0) | 8 | (16.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 4 | (3.9) | 1 | (2.4) | ||

| No | 25 | (83.3) | 50 | (94.3) | 37 | (74.0) | 21 | (87.5) | 89 | (87.3) | 37 | (90.2) | ||

Engineering: Architectural, Mechanical, Telecommunications, Materials, Biotechnology, Medical engineering, Information engineering; Life Science: Medical science, Dental science, Pharmacology; Agriculture: Agricultural science, Forestry, Veterinary science, Animal husbandry, Fisheries science; Humanities: Literature, Culture, History, Philosophy, Sociology, Economy, Management, Law, Psychology; Other sciences: Mathematical, Chemistry, Physical, Cosmic, Environmental science, Basic biology.

P values were calculated by chi-square test

Table 6.

Factors related to feeling the presence of a negative or positive atmosphere under COVID-19 restrictions in 300 researchers.

| Questions |

Category |

There was a negative atmosphere. |

Category |

There was a negative atmosphere. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Often |

Sometimes |

Neither |

Not much |

Not at all |

p value |

(Large group) | Often |

Sometimes |

Neither |

Not much |

Not at all |

p value |

||||||||||||||||||||

| 26 |

(%) |

55 |

(%) |

75 |

(%) |

74 |

(%) |

70 |

(%) |

26 |

(%) |

55 |

(%) |

75 |

(%) |

74 |

(%) |

70 |

(%) |

|||||||||||||

| a. Factors related to feeling negative atmosphere such as "Should we continue research in this situation?" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| There was a positive atmosphere | Often | 4 | −(15.4) | 2 | −(3.6) | 1 | −(1.3) | 4 | −(5.4) | 8 | −(11.4) | <0.0001 | Yes | 4 | −(15.4) | 5 | −(9.1) | 7 | −(9.3) | 22 | −(29.7) | 22 | −(31.4) | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Sometimes | 0 | (0) | 3 | −(5.5) | 6 | −(8) | 18 | −(24.3) | 14 | −(20) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Neither | 1 | −(3.8) | 14 | −(25.5) | 58 | −(77.3) | 18 | −(24.3) | 16 | −(22.9) | Neither | 1 | −(3.8) | 14 | −(25.5) | 58 | −(77.3) | 18 | −(24.3) | 16 | −(22.9) | |||||||||||

| Not much | 4 | −(15.4) | 23 | −(41.8) | 6 | −(8) | 25 | −(33.8) | 4 | −(5.7) | No | 21 | −(80.8) | 36 | −(65.5) | 10 | −(13.3) | 34 | −(45.9) | 32 | −(45.7) | |||||||||||

| Not at all | 17 | −(65.4) | 13 | −(23.6) | 4 | −(5.3) | 9 | −(12.2) | 28 | −(40) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| The change in the amount of research | Increased | 1 | −(3.8) | 0 | (0) | 3 | −(4) | 9 | −(12.2) | 6 | −(8.6) | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| No change | 4 | −(15.4) | 11 | −(20) | 32 | −(42.7) | 26 | −(35.1) | 40 | −(57.1) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Decreased | 21 | −(80.8) | 44 | −(80) | 40 | −(53.3) | 39 | −(52.7) | 24 | −(34.3) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| The quality of research | Increased | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 2 | −(2.7) | 5 | −(6.8) | 6 | −(8.6) | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| No change | 7 | −(26.9) | 25 | −(45.5) | 40 | −(53.3) | 52 | −(70.3) | 47 | −(67.1) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Decreased | 19 | −(73.1) | 30 | −(54.5) | 33 | −(44) | 17 | −(23) | 17 | −(24.3) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Do you feel anxious about future research activity? | Very | 8 | −(30.8) | 16 | −(29.1) | 12 | −(16) | 7 | −(9.5) | 6 | −(8.6) | <0.0001 | Yes | 24 | −(92.3) | 47 | −(85.5) | 50 | −(66.7) | 42 | −(56.8) | 31 | −(44.3 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| A little | 16 | −(61.5) | 31 | −(56.4) | 38 | −(50.7) | 35 | −(47.3) | 25 | −(35.7) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Not so much | 2 | −(7.7) | 8 | −(14.5) | 25 | −(33.3) | 31 | −(41.9) | 24 | −(34.3) | No | 2 | −(7.7) | 8 | −(14.5) | 25 | −(33.3) | 32 | −(43.2) | 39 | −(55.7) | |||||||||||

| Not any | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 1 | −(1.4) | 15 | −(21.4) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| How much did your motivation change | Significantly decreased | 7 | −(26.9) | 9 | −(16.4) | 5 | −(6.7) | 0 | (0) | 1 | −(1.4) | <0.0001 | Decreased | 13 | −(50) | 28 | −(50.9) | 20 | −(26.7) | 9 | −(12.2) | 5 | −(7.1) | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Slightly decreased | 6 | −(23.1) | 19 | −(34.5) | 15 | −(20) | 9 | −(12.2) | 4 | −(5.7) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| No change | 11 | −(42.3) | 25 | −(45.5) | 46 | −(61.3) | 54 | −(73) | 49 | −(70) | No change | 11 | −(42.3) | 25 | −(45.5) | 46 | −(61.3) | 54 | −(73) | 49 | −(70) | |||||||||||

| Slightly increased | 1 | −(3.8) | 0 | 0 | 7 | −(9.3) | 10 | −(13.5) | 8 | −(11.4) | Increased | 2 | −(7.7) | 2 | −(3.6) | 9 | −(12) | 11 | −(14.9) | 16 | −(22.9) | |||||||||||

| Significantly increased | 1 | −(3.8) | 2 | −(3.6) | 2 | −(2.7) | 1 | −(1.4) | 8 | −(11.4) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Questions |

Category |

There was a positive atmosphere. |

Category |

There was a positive atmosphere. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Often |

Sometimes |

Neither |

Not much |

Not at all |

p value |

(Large group) | Often |

Sometimes |

Neither |

Not much |

Not at all |

p value |

||||||||||||||||||||

| 19 |

(%) |

41 |

(%) |

107 |

(%) |

62 |

(%) |

71 |

(%) |

19 |

(%) |

41 |

(%) |

107 |

(%) |

62 |

(%) |

71 |

(%) |

|||||||||||||

| b. Factors related to feeling positive atmosphere such as "We should continue research precisely because we are in such a situation." | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| What was the change in the amount of research? | Increased | 8 | −(42.1) | 8 | −(19.5) | 2 | −(1.9) | 0 | (0) | 1 | −(1.4) | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| No change | 6 | −(31.6) | 20 | −(48.8) | 43 | −(40.2) | 19 | −(30.6) | 25 | −(35.2) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Decreased | 5 | −(31.6) | 13 | −(24.4) | 62 | −(35.5) | 43 | −(45.2) | 45 | −(47.9) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| What was the quality of research? | Increased | 4 | −(21.1) | 6 | −(14.6) | 2 | −(1.9) | 0 | (0) | 1 | −(1.4) | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| No change | 9 | −(47.4) | 25 | −(61) | 67 | −(62.6) | 34 | −(54.8) | 36 | −(50.7) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Decreased | 6 | −(31.6) | 10 | −(24.4) | 38 | −(35.5) | 28 | −(45.2) | 34 | −(47.9) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Do you feel anxious about your future research activity? | Very | 3 | −(15.8) | 2 | −(4.9) | 15 | −(14) | 8 | −(12.9) | 21 | −(29.6) | <0.0001 | Yes | 10 | −(52.6) | 22 | −(53.7) | 76 | −(71) | 37 | −(59.7) | 49 | −(69) | 0.1625* | ||||||||

| A little | 7 | −(36.8) | 20 | −(48.8) | 61 | −(57) | 29 | −(46.8) | 28 | −(39.4) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Not so much | 3 | −(15.8) | 19 | −(46.3) | 30 | −(28) | 23 | −(37.1) | 15 | −(21.1) | No | 9 | −(47.4) | 19 | −(46.3) | 31 | −(29) | 25 | −(40.3) | 22 | −(31) | |||||||||||

| Not any | 6 | −(31.6) | 0 | (0) | 1 | −(0.9 | 2 | −(3.2) | 7 | −(9.9) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| How much did your motivation change? | Significantly decreased | 1 | −(5.3) | 0 | (0) | 6 | −(5.6) | 4 | −(6.5) | 11 | −(15.5) | <0.0001 | Decreased | 3 | −(15.8) | 4 | −(9.8) | 26 | −(24.3) | 19 | −(30.6) | 23 | −(32.4) | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Slightly decreased | 2 | −(10.5) | 4 | −(9.8) | 20 | −(18.7) | 15 | −(24.2) | 12 | −(16.9) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| No change | 6 | −(31.6) | 25 | −(61) | 75 | −(70.1) | 36 | −(58.1) | 43 | −(60.6) | No change | 6 | −(31.6) | 25 | −(61) | 75 | −(70.1) | 36 | −(58.1) | 43 | −(60.6) | |||||||||||

| Slightly increased | 1 | −(5.3) | 11 | −(26.8) | 6 | −(5.6) | 6 | −(9.7) | 2 | −(2.8) | Increased | 10 | −(52.6) | 12 | −(29.3) | 6 | −(5.6) | 7 | −(11.3) | 5 | −(7) | |||||||||||

| Significantly increased | 9 | −(47.4) | 1 | −(2.4) | 0 | (0) | 1 | −(1.6) | 3 | −(4.2) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

P values were calculated by chi-square test.

Table 7.

Factors related to research amount or quality under COVID-19 measures in 300 researchers.

| Questions |

Category |

The quantity of research |

p value |

Category (Large group) |

The quantity of research |

p value |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased |

No change |

Decreased |

Increased |

No change |

Decreased |

|||||||||||||||

| 19 |

(%) |

113 |

(%) |

168 |

(%) |

19 |

(%) |

113 |

(%) |

168 |

(%) |

|||||||||

| a. Factors related to research amount | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Do you feel anxious about your future research activity? | Very | 3 | (15.8) | 6 | (5.3) | 40 | (23.8) | <0.0001 | Yes | 12 | (63.2) | 53 | (46.9) | 129 | (76.8) | <0.0001 | ||||

| A little | 9 | (47.4) | 47 | (41.6) | 89 | (53.0) | ||||||||||||||

| Not little | 4 | (21.1) | 47 | (41.6) | 39 | (23.2) | No | 7 | (36.8) | 60 | (53.1) | 39 | (23.2) | |||||||

| Not any | 3 | (15.8) | 13 | (11.5) | 0 | (0.0) | ||||||||||||||

| How much did your motivation change? | Significantly decreased | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.9) | 21 | (12.5) | <0.0001 | Decreased | 0 | (0.0) | 12 | (10.6) | 63 | (37.5) | <0.0001 | ||||

| Slightly decreased | 0 | (0.0) | 11 | (9.7) | 42 | (25.0) | ||||||||||||||

| No change | 7 | (36.8) | 90 | (79.6) | 88 | (52.4) | No change | 7 | (36.8) | 90 | (79.6) | 88 | (52.4) | |||||||

| Slightly increased | 6 | (31.6) | 9 | (8.0) | 11 | (6.5) | Increased | 12 | (63.2) | 11 | (9.7) | 17 | (10.1) | |||||||

| Significantly increased | 6 | (31.6) | 2 | (1.8) | 6 | (3.6) | ||||||||||||||

| The quality of research | Increased | 9 | (47.4) | 2 | (1.8) | 2 | (1.2) | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||

| No change | 7 | (36.8) | 99 | (87.6) | 65 | (38.7) | ||||||||||||||

| Decreased | 3 | (15.8) | 12 | (10.6) | 101 | (60.1) | ||||||||||||||

| Questionnaires |

Category |

The quality of research |

p value |

Category (Large group) |

The quality of research |

p value |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased |

No change |

Decreased |

Increased |

No change |

Decreased |

|||||||||||||||

| 13 |

(%) |

171 |

(%) |

116 |

(%) |

13 |

(%) |

171 |

(%) |

116 |

(%) |

|||||||||

| b. Factors related to research quality. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Do you feel anxious about your future research activity? | Very | 1 | (7.7) | 11 | (6.4) | 37 | (31.9) | <0.0001 | Yes | 6 | (46.2) | 93 | (54.4) | 95 | (81.9) | <0.0001 | ||||

| A little | 5 | (38.5) | 82 | (48.0) | 58 | (50.0) | ||||||||||||||

| Not little | 5 | (38.5) | 64 | (37.4) | 21 | (18.1) | No | 7 | (53.8) | 78 | (45.6) | 21 | (18.1) | |||||||

| Not any | 2 | (15.4) | 14 | (8.2) | 0 | (0.0) | ||||||||||||||

| How much did your motivation change | Significantly decreased | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 22 | (19.0) | <0.0001 | Decreased | 0 | (0.0) | 20 | (11.7) | 55 | (47.4) | <0.0001 | ||||

| Slightly decreased | 0 | (0.0) | 20 | (11.7) | 33 | (28.4) | ||||||||||||||

| No change | 5 | (38.5) | 129 | (75.4) | 51 | (44.0) | No change | 5 | (38.5) | 129 | (75.4) | 51 | (44.0) | |||||||

| Slightly increased | 5 | (38.5) | 15 | (8.8) | 6 | (5.2) | Increased | 8 | (61.5) | 22 | (12.9) | 10 | (8.6) | |||||||

| Significantly increased | 3 | (23.1) | 7 | (4.1) | 4 | (3.4) | ||||||||||||||

“Has your research activity, in regard to the quantity and quality thereof, changed under the measures for the combating of COVID-19”.

P values were calculated by chi-square test.

Table 2 displays the factors which are significantly different depending on the respondent's gender. A high proportion of female respondents felt that they had been harassed, with a higher proportion of female researchers expressing that they “Strongly felt” that they had been harassed, in comparison to male respondents (Table 2). Although many women reported that their motivation was (at the time of questioning) “Slightly decreased,” male researchers reported a higher rate of feeling that their motivation was “Significantly decreased” (Table 2).

Table 3 summarizes the factors in which significant differences were observed in response to the following question: “How much of an impact (or damage) did the combating of COVID-19 have on (or cause to) your research/work environment?” In the group who had their research environment impacted by COVID-19 measures, a high percentage of respondents reported having been harassed and that there was a presence of a negative atmosphere within their laboratories (Table 3). Conversely, in the groups that were seriously affected by COVID-19 measures, the proportion of those who felt a positive atmosphere in their laboratories is low (Table 3). The group affected by COVID-19 measures reported high rates of anxiety over their future research activities and a decrease in motivation to conduct research (Table 3).

Table 4 summarizes the factors to which significant differences are observed in response to the following question: “Have you ever felt that you were the victim, or perpetrator, of some kind of harassment in the face of a new coronavirus infection?” Among the groups that felt harassed in the face of COVID-19 measures, a high proportion reported feeling a negative atmosphere, anxiety, and decreased motivation for their research (Table 4a). There were only four researchers who felt they perpetrated harassment in the face of COVID-19 measures. All these researchers felt a negative atmosphere in the laboratory. In contrast, regarding their motivation for research, none of them were “Significantly decreased,” and all were “Slightly decreased” (Table 4b). The factor associated with the research area is shown in Table 5. The proportion of researchers who felt that they had received harassment was higher than the other areas in the life sciences-related faculty (Table 5).

Table 6 summarizes the factors with significant observed differences to the following questions: “Was there a negative atmosphere, exemplified by questions such as ‘Should we continue research in this situation?’” (Table 6a) and “There was a positive atmosphere, exemplified by statements such as ‘We should continue research precisely because we are in such a situation’” (Table 6b). The Negative Feeling Group and the Positive Feeling Group exhibited an opposite relationship (Table 6a). The Negative Feeling Group felt that, under COVID-19 measures, their research activities were reduced, along with the quality thereof (Table 6a). The Negative Feeling Group further reported a high rate of anxiety concerning their future research activities, as well as a decrease in motivation to conduct research (Table 6a). The Positive Feeling Group, however, was more likely to choose to increase the quantity and quality of the research they conducted, as well as reporting an increase in their motivation (Table 6b). The group that often-felt the presence of a positive atmosphere also has a higher ratio of respondents who did not feel any anxiety concerning their future research activity particularly when compared to other groups, including the group that sometimes-felt the presence of a positive atmosphere (Table 6b).

Table 7 summarizes the factors with observable and significant differences to the following question: “Has your research activity, in regard to the quantity (Table 7a) quality (Table 7b) thereof, changed under the measures for the combating of COVID-19?” Under the COVID-19 measures, the group who felt a decrease in research amount or quality had a higher rate of anxiety concerning their future research activities (Table 7a,b). The group who felt a decrease in their research amount or quality also had a high rate of decreased research motivation, while the group who felt an increase in the research amount and quality had a high ratio of increased motivation (Table 7a,b). There is a positive relationship between changes in research amount and quality (Table 7a).

In the free description regarding the harassment present under COVID-19 conditions, some academic harassment was pointed out. Among the 300 researchers, 169 were free to comment; of these, 122 were considered to be meaningful. There were cases in which respondents were blamed for their unfamiliarity with teleworking or remote lectures (10 cases, 8.2%). There were also some cases in which employees were forced to work on-site, even if remote work was possible; some were forced to work or conduct research in a situation strictly warned against by the “3 Cs” of social distancing (7 cases, 5.7%). Some researchers found that the restrictions on research and travel (for attending academic conferences) were harassment, even though these restrictions were known to be measures against the spread of infection (7 cases, 5.7%). Conversely, many researchers who did not feel they were being harassed cite that contact with the harassers has been reduced or eliminated because of being able to work from home (13 cases, 10.7%). Some respondents were comfortable with remote work, employment at their discretion, and the lack of direct supervision under the measures for combating COVID-19 (6 cases, 4.9%). In the free description concerning anxiety about their future research, among the 300 researchers, 183 were free to comment; of them, 179 were considered to be meaningful. Many researchers expressed concern over how long their research activities may be restricted (23 cases, 12.8%). These researchers were worried about reducing their own research activities, the reduction in research funds (including both competitive grants and school public funds) (30 cases, 16.8%), and increased difficulty in securing posts (17 cases, 9.5%). Researchers conducting field work and face-to-face research were also worried that they would not be able to conduct their research (11 cases, 6.1%). In terms of research which makes use of library materials and on-campus databases, activity was significantly affected by working from home due to the campus lockdown (12 cases, 6.7%). Researchers further expressed their concern that communication among researchers would be reduced due to the restrictions in business trips abroad and participation in academic conferences (32 cases, 17.9%). Some researchers in charge of classes were apprehensive about their own research time being lost because of the time spent dealing with the new remote and on-demand lecture styles (15 cases, 8.4%). The status of participants and research fields are also biased, and the number of participants was small for subgroup analysis. Therefore, it was difficult to statistically evaluate the respondents' comments in this survey.

4. Discussion

In this study, we focused on the impact of the influence of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic on researchers. We obtained important information to understand the current situation of researchers in Japan under COVID-19 measures. However, to clarify their effects, the situation of three phases (i.e. before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic) must be compared. In addition, future studies should investigate the “quality,” “quantity,” and “harassment” of research more concretely and quantitatively.

This study reveals that researchers are more likely to be involved in harassment (either as recipients or perpetrators) than other populations during the period of restrictions in combating COVID-19 (Table 1). Some researchers reported being forced to work in the lab, despite government-led encouragement to work from home to avoid the risk of infection. In contrast, in the comments to the free description, it was noted that because of the nature of remote work, some researchers had less contact with harassers and had a relatively more comfortable time.

Laboratories in academia are characterized by “strong hierarchies” [15,16] and “small, globally-interconnected specialized communities,” which may lead to various types of harassment [16]. Since the occupations of other populations have not been clarified in this study, it is necessary to further examine these occupational areas. Furthermore, across the 300 researchers surveyed, the ratio of those who received harassment was higher among the field of life science research (26.0%) than other academic fields (9.7–16.6%) (Table 5). It was further reported in a previous study that medical-related science departments were less recognize that “Harassment in organization” and “pressuring to fabricate, falsify, or plagiarize research outputs” were academic harassment than other departments surveyed in Japanese private university [16]. This finding is suggested to be a result of the differences in the organizational structure wherein faculty members of humanities departments in Japan tend to conduct research and education independently; in the medical science lab, several staff members are engaged in both research and medical care [17]. It has been suggested that the concept of pandemics may move to an interdisciplinary science with an integrated approach of life sciences, information technology, artificial intelligence, meteorology, ecology and so on [18]. Further studies are awaited about the differences of each research field.

Various types of harassment, typified by sexual harassment, are well-recognized to affect more women than men [[19], [20], [21], [22]]. It has been previously reported (via a survey of Japanese private university staff) that women have a higher prevalence of experiencing all forms of harassment—sexual, gender-related, and academic—than men [18]. There is a causal relationship between the existence of academic harassment and impaired academic motivation [23]. It has been pointed out that decreased academic motivation can potentially lead to poor academic performance and the reason for drop-out [23]. Several studies have raised concerns about the occurrence of discrimination against women during COVID-19 countermeasures [[24], [25], [26]]. However, for women's harassment, it was necessary to compare during COVID-19 with peacetime. In this survey, women (24.1%) are observed to be more likely to be harassed and less motivated during the COVID-19 restrictions than men (11.4%) (Table 2). The free descriptive answer texts in this survey did not, at least, include a direct description of sexual harassment. Further verification, including detailed deciphering of free descriptions, is necessary to determine whether this finding was unique to the situation faced by researchers under COVID-19 countermeasures.

In this survey, 41 out of 300 (13.7%) researchers responded that they were harassed, but only four (1.3%) felt they had perpetrated harassment (Table 4). It is considered, thus, that this finding is because of the low levels of awareness had by perpetrators of harassment on their actions [27]. In contrast, it is very interesting that these four perpetrators also all felt the presence of a negative atmosphere in the lab environment, as well as reporting that their motivation had decreased (Table 4). It is necessary to devise a wet-lab that avoids the “3C”-s by strict online schedule management and enhance online communication between researchers. It is important to hold online lab meetings on a regular basis, and it is the responsibility of the principal investigator and lab manager to listen not only to the research progress of junior researchers or students but also to their mental state. Regarding harassment countermeasures, it is necessary to conduct continuous investigations and activities by the harassment countermeasures committee and the consultation desk even during the COVID-19 pandemic [24]. We believe that the problems and anxieties that researchers always have may have surfaced through measures against COVID-19. However, although we have received testimony from several researchers about this, it remains a speculation. Therefore, harassment may be the result of stress experiences under the COVID-19 measures, but the psychology behind the behavior cannot be clarified in this study because of the small number of cases.

In this study, we divided laboratory situations into two distinct atmospheres: “negative atmosphere: Should we continue to conduct research in this situation?” and “positive atmosphere: We should continue to conduct research precisely because we are in such a situation.” The researchers whose research progress was affected by COVID-19 recognized a negative atmosphere within their labs and were worried about their own future research activity (Table 3). It is suggested that those feelings described above might have led to a decrease in research motivation. The rate of the decreased motivation of those who had an effect (was lower than that of those who had no effect on research activities (Serious impact, 39.2%; Some impact, 26.7%; Nothing, 8.1%) (Table 3). The lab's negative atmosphere was associated with negative factors such as reduced research volume and quality, anxiety, and reduced motivation (Table 6a). The lab's positive atmosphere resulted in the opposite of that identified in negative atmospheres (Table 6b). It is considered important to maintain a positive atmosphere in a lab setting, even in the face of a disaster. Among the group that experienced a positive atmosphere, only 1.7% (1/60) of respondents did not sympathize with the atmosphere (Fig. 2L). Conversely, in the group that felt a negative atmosphere, 33.3% (27/81) did not sympathize with the negative atmosphere (Fig. 2J), suggesting that it is necessary to understand the feelings of each staff member in a disaster situation. It was also pointed out that communication with researchers from inside and outside the country via the society of academics was reduced. Utilizing online communication methods during normal times will further help prevent researchers from being isolated during a disaster.

Changes in the quantity and quality of the research conducted during the COVID-19 restrictions were positively associated with changes in motivation and anxiety (Table 7). The quality and amount of research are considered to be important indicators for researchers to be evaluated. However, it is necessary to investigate the contents more concretely to formulate future measures. In addition, although “very anxious” is thought to lead to “Significantly decreased motivation,” the relationship between them could not be clarified in this study. Many Japanese researchers are funded by the government – such as KAKENHI (The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology or Japan Society for the Promotion of Science) [28]. In addition, public disclosure of research results such as “scholarly papers,” “presentations at conferences,” and “writing of books” is adopted as an evaluation item for academic staff at most universities or institutes [29]. Researchers are worried that research results will be required as usual, despite the delays in their research (because of work restrictions faced while society combats COVID-19). Some researchers are further worried that these issues may affect the acquisition, and maintenance, of academic positions in the future as such, it is hoped that the policy for researchers working through the COVID-19 crisis will be promptly decided upon. In addition, it has been reported that Japanese university teachers are exhausted from adapting to the new style of taking classes class [30]. In this survey, researchers displayed fear concerning the time that would be needed to be spent on preparing for the new on-demand or remote lecture patterns. It is known that researchers who are obliged to both teach and conduct research have lower levels of well-being related to demands and control than those who are obliged to do either one or the other [16]. One of the researchers' concerns was that library materials and databases were no longer available because of campus lockdowns. As such, it is expected that the development of online facilities at Japanese universities will be promoted multilaterally in response to taking social measures against COVID-19 [8,9].

One study reported that many students cannot imagine an academic career because research at the university level is highly competitive, keeping a balance with family life appears difficult, and wages are low [31]. A survey of over 6000 graduate students revealed that they were anxious [32]. While most of the respondents were satisfied with pursuing a Ph.D., more than one-third needed help with anxiety and depression caused by their Ph.D. research [32]. Therefore, students and young scientists are considered to already be worried about their research activity regardless of the presence of a disaster (such as COVID-19). These feelings of anxiety may be heightened and resurface by greater instability within the research environment in the face of disasters. Nature Research surveyed the activities of research leaders or mentors in 2019.1 The demand for support measures for “securing research time” and “reducing clerical work” was remarkable. Due to the huge amounts of miscellaneous affairs and clerical work, research and paper writing time which should be the center of original work activities is being cut off. In this survey, which had a relatively high ratio of professors (39.0%) and associate professors (31.7%) (Fig. 2H), it was not possible to clarify the characteristics of each position. It will be necessary to clarify the differences between positions for example: “professors and students,” and “senior and junior researchers” to prepare for the lab procedure for conducting research in the event of a disaster.

Enhancing communication between researchers through webinars and online conferences, as well as casual participation will sustain researchers' motivation [33,34]. In gene expression research, open databases can be used to verify the data obtained previously and identify new research targets. When researchers are unable to do research, they will be able to spend time working online with lab members to plan future projects [34]. From this pandemic experience, it is necessary to build sustainable research, that is, a new normal research environment.

5. Conclusion

The impact of disasters (and the response to them) on researchers' motivation has not been clarified. Researchers, especially young ones, are always experiencing instability in their careers. They are exposed to a variety of unique concerns that are different from non-researchers, such as obtaining research funding, pressure on the demand for research results, and securing a position. There is concern that the anxiety caused by these excessively competitive environments will erupt because of the suppression of activities by COVID-19. Therefore, it is important to have an online community in peacetime to keep researchers from being isolated. Moreover, the government should understand the psychology of researchers when research activities are hindered, and respond through measures against COVID-19. In addition, lab leaders such as professors and principal investigators will need to plan lab operations in case of disaster. To clarify the psychology of researchers concerning disasters, further comparative studies between disasters and normal situations are required.

Acknowledgment

We appreciate Ms. Chieri Ohishi and Ms. Satsuki Nagata (Cross Marketing, Tokyo, Japan) for their kind support.

This work was supported by the Core Research Cluster of Disaster Sciencs in Tohoku University (Designated National University).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100128.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basic Policies for Novel Coronavirus Disease Control . Cabinet public relations office. Cabinet Secretariat (Japan); 2020. Revised on April 7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw R., Kim Y.K., Hua J. Governance, technology and citizen behavior in pandemic: lessons from COVID-19 in East Asia. Prog Disaster Sci. 2020;6:100090. doi: 10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basic Policies for Novel Coronavirus Disease Control . Cabinet public relations office. Cabinet Secretariat (Japan); 2020. Revised on April 16. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallego V., Nishiura H., Sah R., Rodriguez-Morales A.J. The COVID-19 outbreak and implications for the Tokyo 2020 summer Olympic games. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;34:101604. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Secretariat of the Policy Board, Bank of Japan . April, 2020. Outlook for economic activity and prices. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumagai S., Gokan T., Tsubota K., Isono I., Hayakawa K., et al. April 28, 2020. Impact of the 2019 novel coronavirus on global economy: analysis using mobility data from mobile phones. IDE Policy Brief No11. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiitaka L.G. Coronavirus crisis offers chance to update Japanese schools. Jpn Times April. 2020;20 [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Donoghue J.J. In era of COVID-19, a shift to digital forms of teaching in Japan: teachers are having to re-imagine their roles entirely amid school closures. Jpn Times April. 2020;21 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y., Zhang H., Ma X., Di Q. Mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemics and the mitigation effects of exercise: a longitudinal study of college students in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(10) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaparounaki C.K., Patsali M.E., Mousa D.V., Papadopoulou E.V.K., Papadopoulou K.K.K., et al. University students' mental health amidst the COVID-19 quarantine in Greece. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113111. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan H. A glimpse of university students' family life amidst the COVID-19 virus. J Loss Trauma. 2020:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ivancevic A. Finding motivation in the lighter side of science. Nature. 2020;581(7806):108. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01151-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institution for Academic Degrees and University Evaluation Quality assurance of higher education in Japan. 2012. https://www.niad.ac.jp/n_shuppan/evaluation/publication_quality_assurance.pdf

- 15.Furger M. Harassment among doctoral students. Horizons - Swiss Res Mag. 2018 06/09/ [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bullying and Harassment in Research and Innovation Environments . October 2019. An evidence review. UK Research and Innovation. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagasawa T., Nomura K., Takenoshita S., Hiraike H., Tsuchiya A., et al. Scale development on perception of academic harassment among medical university faculties. Jpn J Hyg. 2019;74(0) doi: 10.1265/jjh.18033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fakhruddin B., Blanchard K., Ragupathy D. Are we there yet? The transition from response to recovery for the COVID-19 pandemic. Prog Disaster Sci. 2020;7:100102. doi: 10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huerta M., Cortina L.M., Pang J.S., Torges C.M., Magley V.J. Sex and power in the academy: modeling sexual harassment in the lives of college women. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2006;32(5):616–628. doi: 10.1177/0146167205284281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takeuchi M., Nomura K., Horie S., Okinaga H., Perumalswami C.R., et al. Direct and indirect harassment experiences and burnout among academic faculty in Japan. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2018;245(1):37–44. doi: 10.1620/tjem.245.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sivertsen B., Nielsen M.B., Madsen I.E.H., Knapstad M., Lønning K.J., et al. Sexual harassment and assault among university students in Norway: a cross-sectional prevalence study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(6) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pina A., Gannon T.A., Saunders B. An overview of the literature on sexual harassment: perpetrator, theory, and treatment issues. Aggress Violent Behav. 2009;14(2):126–138. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young-Jones A., Fursa S., Byrket J.S., Sly J.S. Bullying affects more than feelings: the long-term implications of victimization on academic motivation in higher education. Soc Psychol Educ. 2015;18(1):185–200. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holland K.J., Cortina L.M., Magley V.J., Baker A.L., Benya F.F. Don't let COVID-19 disrupt campus climate surveys of sexual harassment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020 Sep;18:202018098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2018098117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malisch J.L., Harris B.N., Sherrer S.M., Lewis K.A., Shepherd S.L., McCarthy P.C., et al. Opinion: in the wake of COVID-19, academia needs new solutions to ensure gender equity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020 Jul 7;117(27):15378–15381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010636117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Viglione G. Are women publishing less during the pandemic? Here's what the data say. Nature. 2020 May;581(7809):365–366. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Witze A. Sexual harassment is pervasive in US physics programmes. Nature. 2019 doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-01303-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mizunuma Y., Tsuji K. 2019 8th international congress on advanced applied informatics (IIAI-AAI), Toyama, Japan. 2019. An investigation on the researchers who received japanese grant-in-aid for scientific research (KAKENHI) with a focus on their roles and research achievements; pp. 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimada T., Okui M., Hayashi T. Research on Academic Degrees and University Evaluation; 2009. Progresses and problems of faculty evaluation system in Japanese Universities. No.10:61–78 (Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shift to online classes leaves Japan's university teachers exhausted . May 25, 2020. The Japan Times. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woolston C. PhDs: the tortuous truth. Nature. 2019;575(7782):403–406. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-03459-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woolston C. Graduate survey: Uncertain futures. Nature. 2015;526(7574):597–600. doi: 10.1038/nj7574-597a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bottanelli F., Cadot B., Campelo F., Curran S., Davidson P.M., Dey G., et al. Science during lockdown - from virtual seminars to sustainable online communities. J Cell Sci. 2020 Aug 14;133(15) doi: 10.1242/jcs.249607. [jcs249607] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scientists in a time of COVID-19. Nat Plants. 2020;6:589. doi: 10.1038/s41477-020-0714-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material