Abstract

Emergency managers (EMs) and Emergency Social Services Directors (ESSDs) are essential service providers who fulfill critical roles in disaster risk reduction. Despite being positioned throughout all levels of government, and in the private sector, EMs and ESSDs fulfill roles which occur largely behind the scenes. The purpose of this phenomenological study was to explore the roles of EMs and ESSDs from different regions across Canada. Specifically, we wanted to understand their perceptions of barriers, vulnerabilities and capabilities within the context of their roles. EMs (n = 15) and ESSDs (n = 6) from six Canadian provinces participated in semi-structured telephone interviews. Through content analysis, five themes and one model were generated from the data: 1) Emergency management is not synonymous with first response, 2) Unrealistic expectations for a “side-of-desk” role, 3) Minding the gap between academia and practice with a ‘whole-society’ approach, 4) Personal preparedness tends to be weak, 5) Behind the scenes roles can have mental health implications. We present a model, based on these themes, which makes explicit the occupational risks that EMs and ESSDs may encounter in carrying out the skills, tasks, and roles of their jobs. Identification of occupational risks is a first step towards reducing vulnerabilities and supporting capability. This is particularly relevant in our current society as increased demands placed on these professionals coincides with the increasing frequency and severity of natural disasters due to climate change and the emergence of the world wide COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Disaster risk reduction, Emergency management, Burnout, Business continuity, Occupational risk, Disaster preparedness

1. Introduction

In 2015, The United Nations released The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, an international, action-oriented approach to achieving a reduction in disaster risks across economic, physical, social, cultural, and environmental domains [1]. Canada, along with 187 other countries, adopted the Sendai framework, and the federal government has since released the Emergency Management Strategy for Canada: Toward a resilient 2030 [2]. This complimentary strategy takes aim at Canadian specific priority areas including: 1) Enhance whole-of-society collaboration and governance to strengthen resilience, 2) Improve understanding of disaster risks in all sectors of society, 3) Increase focus on whole-of-society disaster prevention and mitigation activities, 4) Enhance disaster response capacity and coordination and foster the development of new capabilities, and 5) Strengthen recovery efforts by building back better to minimize the impacts of future disasters [2]. Recommendations for achieving these priorities, and strengthening disaster risk reduction (DRR), emphasize the need for investment in multi-hazard and multi-sectoral approaches, as well as increased resources and support for the public service workers who implement these approaches [1].

Emergency managers (EMs) and Emergency Social Services Directors (ESSDs) are essential service providers who fulfill critical roles in DRR. They carry out important tasks in positions throughout all levels of government and in the private sector, and their roles span all phases of the disaster management cycle: mitigation/prevention, preparedness, response and recovery [3,4]. Broadly, EMs are responsible for reducing community vulnerabilities to hazards and planning for, and coping with disasters [2,5]. Whereas, ESSDs put in place supports that meet the essential needs of communities affected by emergencies/disasters [6,7]. Despite the vital jobs of these professionals, emergency management departments are chronically underfunded and understaffed [8,9].

As more frequent and severe disasters occur due to climate change, the demands placed on EMs and ESSDs are growing. Climate change poses a serious threat to human health and sustainable development [10]. The National Capital Region of Canada (Ottawa, Gatineau and surrounding areas) alone has experienced 3 substantial natural disasters in two years (2017 and 2019) due to flooding and tornadoes. Many areas in Canada cope with the aftermath of severe flooding and extreme forest fires in the warmer months, and snow storms and blizzards in the cooler seasons. This experience is not unique to Canada. It is widely acknowledged that more frequent and severe disasters have become the new reality of the changing climate across the globe [11]. The United Nations have incorporated action against climate change within the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals, with an emphasis on improving human and institutional capacity to reduce its negative impacts [10]. How the capacity of EMs and ESSDs is currently being supported amidst the increasing pressures due to climate change is not well understood.

Increasing demands on EMs and ESSDs comes with an increased risk of occupational stress that can impact both mental and physical health. It is well known that individuals involved in disaster-related work are at a higher risk of experiencing negative psychosocial impacts due to: exposure to traumatic events, high work demands, working with disrupted communities, and separation from loved ones at times of uncertainty [12]. These occupational stressors are more commonly associated with the roles of first responders, such as fire fighters, police officers, and emergency medical services [12]. However, less is known about how these stressors impact EMs and ESSDs in their day-to-day roles and what vulnerabilities they experience.

Our research seeks to add to the growing body of literature exploring disaster and emergency management practices in Canada. This paper is part of a larger research program exploring the social construction of resilience in the context of disaster mitigation/prevention, preparedness, response and recovery. Here we present findings from a qualitative phenomenological study where we explored the role of EMs and ESSDs from different regions across Canada. Specifically, we wanted to understand their perceptions of barriers, vulnerabilities and capabilities within the context of their roles.

2. Methods

Initial approval for this study was received in April 2017 and modified in March 2018 from the University of Ottawa research ethics committee (#H10-16-02). Data collection began in September of 2018 and was completed by April 2019; purposive and snowball sampling were used to recruit EMs and ESSDs from across Canada. Our sampling strategy was to recruit approximately 20 people. Participants were initially contacted by email and this information was obtained through publicly available websites. The inclusion criteria for participation was: 1) Hold an emergency management or emergency social services director-level title, which may or may not be held in conjunction with other titles; 2) The emergency management or emergency social services title could be held for any length of time; 3) Reside in Canada; 4) Work at any level of government (municipal, provincial, federal) or in the private sector; 5) Able to participate in an interview in either official language (French or English).

Data were collected in the form of 30-min semi-structured telephone interviews, conducted by the first two authors (SO and VB). Participants provided informed consent to complete the interview and had the option to consent to being audio-recorded and quoted. When participants chose not to be audio-recorded, notes were taken to document the interview. The semi-structured interview guide consisted of 14 open-ended questions developed in an iterative and collaborative process to facilitate a discussion of the role of EM or ESSD, and specifically inquire about their perceptions of capability and vulnerability within the context of these roles. Probes and prompts were used to clarify information provided by participants and the interview guide was modified as needed after interviews to improve clarity in question asked [13]. Data was generated until no new relevant insights emerged and saturation was achieved.

The interviews were transcribed verbatim by one team member and checked for accuracy by a different team member. The transcripts were analyzed using line-by-line in vivo coding which was initially performed independently, and then concurrently by the first two authors using NVivo10 software. The coding grid was developed inductively, codes were mutually agreed upon and grouped in an iterative process by all authors [14,15]. Inductive reasoning was used to develop themes from the coded transcripts [16]. The emergent themes presented below represent the subjective experiences of the participants.

3. Results

In this study we sought to answer the following questions: What are the roles of Emergency Managers (EMs) and Emergency Social Services Directors (ESSDs) in Canada? What are their perceptions of capabilities, vulnerabilities and barriers that exist within the context of these roles? The final narrative data set was generated with n = 15 EMs and n = 6 ESSDs, for a total of n = 21 participants. These participants held a variety of titles; some examples include: Emergency Manager, Emergency Social Services Director, Program Manager for the Emergency Management Office, Emergency Management Program Advisor, and Emergency Preparedness Coordinator. The participants were based throughout six Canadian provinces: n = 5 Western provinces, n = 13 Central provinces and n = 3 Atlantic provinces. The study sample consisted of 57% of participants working at the municipal level, 33% at the provincial level, 5% at the federal level and 5% in the private sector. Time spent in their current position as an EM or ESSD ranged from 8 months to 13 years, with 52% of participants having 5 or more years of experience. Using content analysis, five themes were identified and a model was created to highlight the reality of the day-to-day roles carried out by EMs and ESSDs:

Theme 1: Emergency management is not synonymous with first response

Theme 2: Unrealistic expectations for a “side-of-desk” role

Theme 3: Minding the gap between academia and practice with a ‘whole-society’ approach

Theme 4: Personal preparedness tends to be weak

Theme 5: Behind the scenes roles can have mental health implications

3.1. Theme 1: emergency management is not synonymous with first response

The day-to-day tasks that underpin EM roles were highlighted in three different ways by participants: 1) Tasks were categorized as administrative or operational; 2) Tasks were determined by the location and level of the position (federal, provincial or municipal government, or private sector); and 3) Roles are distinct from those of first responders. The most recent 10 years were described as a period of growth for the field of emergency management, particularly in terms of professional development.

The tasks of EMs can be understood as either administrative or operational. Table 1 consists of examples of administrative and operational tasks described by participants. Both administrative and operational tasks could be carried out in any of the four phases of disaster management (mitigation/prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery), with a greater emphasis on operational tasks during the response and recovery phases.

Table 1.

Administrative and operational tasks as described by EMs.

| Administrative Tasks | Operational Tasks |

|---|---|

|

|

The descriptions of tasks that make up the EM role varied by the location and level of the position within government or the private sector. At the federal level, surveillance-focused tasks were emphasized such as monitoring, collecting and sharing information. At the provincial level, providing guidance, direction and resources to the municipalities was highlighted. At the municipal level, action tasks were emphasized, and included the provision of services such as public education. In the private sector, providing guidance to government departments or other clients was the main focus.

Finally, EMs compared and contrasted their roles with those of first responders. They described how first responders have well-known roles and high public visibility, while EMs have lower profiles and receive less recognition in comparison. This is notably true when there is no obvious activation occurring in the community, and a greater period of time is spent completing administrative rather than operational tasks. The following quotations highlight some of the ways in which the profession of emergency management is different from first response.

“Police and fire are very much command and control, whereas emergency management is consult, facilitate and coordinate” (EM)

“First responders are used to getting in and getting out, they make sure life safety is good and then depart from the scene, and that is where emergency management really comes in” (EM)

Participants highlighted a clear distinction between EM and first responder roles but noted that many individuals who hold, or have held, first responder roles have the ability to transition into an EM position. This was seen as both a benefit, in the experience and knowledge that these individuals bring to the role, and a limiting factor, as “the training that first responders receive often does not translate to the emergency management role” (EM). Engagement in administrative tasks, such as prevention and planning activities, business continuity planning and stakeholder engagement were particular areas noted to require a different skillset when compared with operational duties.

To reduce the number of individuals obtaining an EM position without appropriate training, most, if not all, EM positions in Canada now require candidates to have an academic background in disaster and emergency management from a post-secondary institution. Participants noted that requiring an academic background to enter the field of emergency management is one of the distinct ways the profession has evolved in the last 10 years. They described having an academic background as an asset which allows for profession-specific training and awareness of relevant tools, such as frameworks and documents for use in the field.

“The biggest thing in regards to emergency management is the recognition that this really is a stand-alone career now because of the number of programs you see in post- secondary” (EM)

“I think part of the benefit of having people in our emergency management units that have the educational background in disaster management, as well and the research experience, is that they are able to bring to the table some of those documents that you might be referring to and say this area is doing it this way and we could apply it in our jurisdiction or did you know that there is a whole-of-community framework out there that we could be consulting.” (EM)

EMs fulfill dynamic roles – which continue to evolve – as an influx of individuals trained in post-secondary disaster and emergency management programs enters the field. Suggested by one participant, emergency management is a “broader umbrella term” (EM) that includes many programs where both administrative and operational tasks are required that extend into all four phases of disaster management. EMs engage in essential roles that are distinct from those of first responders when disasters and emergencies arise.

3.2. Theme 2: unrealistic expectations for a “side-of-desk” role

The essential roles of ESSDs are distinct yet complimentary to those of EMs. The tasks carried out by ESSDs can also be categorized as administrative or operational, and specific to the level of the position within government. ESSDs have concerns related to sustainability of service provision, particularly during long-term recovery periods. Compounding this concern are high public expectations for support, and an over-reliance of the public on the government to provide those supports.

The administrative tasks described by ESSDs were similar to those of EMs, but greater emphasis was placed on connecting with stakeholders, such as non-profit organizations, community partners and other governmental departments. ESSDs provide social programming, regardless of whether there is an activation in the community, and rely on their network of stakeholders for assistance with carrying out these operations. Examples of programs within the portfolio of ESSDs include, community housing, financial assistance, and disability supports. In the event of an activation, ESSDs not only continue to provide these programs, but they are also responsible for facilitating the provision of six emergency social services 1) food 2) clothing 3) shelter 4) registration 5) inquiry and 6) personal services. Importantly, “when an emergency arises, all the other tasks on our plate do not get alleviated” (ESSD), but rather the workload accumulates because people who may not have needed social services in the past now require assistance as the result of an emergency/disaster.

At the provincial and municipal levels, ESSDs reported being involved in stakeholder engagement. ESSDs at the provincial level described tasks such as writing, developing and communicating plans, figuring out logistics surrounding the provision of the six emergency social services, and monitoring the flow of resources. At the municipal level, ESSDs described more operational tasks, such arranging transportation for individuals/families.

Both EMs and ESSDs have sustained involvement in the response and recovery phases post-disaster, but ESSDs have unique concerns about meeting the needs of communities during these periods. Many of the participants we interviewed noted that they hold titles in addition to that of ESSD, and are therefore only able to allocate a small amount of their working hours to this particular role – hence the term ‘side-of-desk role’.

“I have a concern about the very ‘side of desk’ nature of our responsibilities. When an emergency arises, to be relying on a very small number of people who have only been able to dedicate a small amount of their time to this area is kind of an unrealistic expectation or the expectation does not match the resources put towards it” (ESSD)

“This is very much a ‘side-of-desk’ responsibility for me, there could be long stretches of time where I have very little active participation in this file. In a way that concerns me because I would think that the more often we keep our minds on issues, such as preparedness for emergencies, the more likely we are to be able to respond to them properly for if and when they do arrive” (ESSD)

Lack of professional hours allocated to the prevention/mitigation and planning phases, and lack of resources, training, and funding were all voiced concerns with respect to feeling capable of supporting citizens post-disaster. This lack of investment in human resources was of particular concern when discussing disasters that would require support for longer recovery periods. Compounding this concern is an observed over-reliance of the public on government to meet their needs post-disaster, as expressed by one participant:

“There has always been this culture that I have a problem and I need the government to help solve that problem. I think that people need to appreciate that the more they can do to prepare themselves in their own communities will help to ensure that people who really need support will get the resources that they need in a timely manner” (ESSD)

Public expectations on professionals such as ESSDs are high, and many of the participants expressed doubt about the capacity of government departments to respond adequately in the event of a large-scale disaster. One participant noted that in their jurisdiction they “rely on the fact that major disasters with long-terms consequences don't happen here” (ESSD), which represents a fallacy in the midst of a changing climate and widespread pandemic. Participants described how they work around scarce resources and high demands by focusing on assisting those affected to reach a ‘new normal’. This can be achieved by creating partnerships with stakeholders – such as NGOs – to share and coordinate resources.

3.3. Theme 3: minding the gap between academia and practice with a ‘whole-society’ approach

While community partnerships help to cover a gap in resources, another gap exists between community-based approaches described by academia and those occurring in practice. A ‘whole-society’ or ‘all-of-society’ approach, as described by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA, 2011), is one of the guiding frameworks for best practice in emergency management. While many participants had heard of this approach, the extent to which it was recognized as an important process and implemented in practice varied between participants. A gap between academia and practice was the most commonly cited barrier to implementation. Participants expressed a need for action items that describe how to go about this process.

Participants described a ‘whole-society’ approach as meaning that everyone in society is responsible and has a role to play in all phases of disaster management. However, engagement of citizens in this process is not necessarily reflected in practice. A ‘whole-of-government’ approach was cited as more common in practice, and refers to the process by which multiple sectors and levels of government collaborate, particularly in the response and recovery phases. Progression from ‘whole-of-government’ to ‘whole-society’ was noted to only go as far as engaging the private sector and NGOs such as The Canadian Red Cross and The Salvation Army.

“In practice we do already implement a ‘whole-of-government’ type approach, there is still more work we could do to make it more ‘whole-of-community’ whereby we are engaging the private sector more and the non- profit sector a little bit more … we have a network in the non-profit sector and I would say that is as far as the ‘whole-of-community’ approach has gone” (EM)

“If ‘whole-society’ also means consulting with the residents, that is something that I do not do at this point” (EM)

One participant described emergency management as being “from the ground up, individual to community” (EM), however many other participants noted that in reality engagement more commonly occurs at the level of government, private sector and NGOs – with interventions then trickling down to the individual level. This is more representative of a top-down approach whereby interventions are more likely to happen ‘to’ and not ‘with’ individuals in society. A potential consequence of this top-down approach is that the interventions provided may not necessarily match the needs of the individuals, families and communities affected. However, despite this current reality, some participants recognized the importance of engaging the community:

“There are some gaps on how to best assist community members when disasters occur, so we have started to work with community groups a lot more closely to find out what their needs are, what they need us to help them with in developing their own resilience and their own preparedness” (EM)

While some participants noted the importance of engaging citizens in the community to promote a ‘whole-society’ approach, not everyone saw it as a viable option. In addition to a general lack of time and resources to promote citizen engagement, some participants endorsed a lack of understanding of how to go about carrying out this type of approach.

“It is not an approach that I find our organization has really already embraced and I think part of the challenge is that there is no sort of model out there to tell you how to do a ‘whole-society’ or ‘whole-of-community’ approach” (EM)

“I think when we talk about things like ‘whole-community’ they are great to sort of talk about and the concepts are definitely out there, it's not a secret in any way, anyone can go learn about it, but I think what is missing is an approach that practitioners can actually take and implement” (EM)

A gap between academia and practice was identified as a reason for the disconnect between the concept of a ‘whole-society’ approach and the process for carrying it out in the field. One participant suggested that there still exists an underlying sentiment that “academia and theory are no good for practice” (EM). A continued influx of individuals entering the field of emergency management with degrees from post secondary institutions may alter this underlying sentiment by fostering awareness of frameworks and resources available for reference in practice. However, bridging the gap between academics and practitioners will require continued collaboration and acknowledgement that every jurisdiction has its own unique needs.

3.4. Theme 4: personal preparedness tends to be weak

Provision of public education related to preparedness for emergencies and disasters was a commonly cited task for both EMs and ESSDs; examples included, emergency preparedness week and the promotion of 72-h readiness kits. Although many participants highlighted the importance of personal preparedness, they also admitted they did not feel prepared themselves. This has profound implications for continuity of critical operations within EM and ESSD departments.

“I have been responsible for helping to deliver public education and awareness programs where I sort of go out and spread the word about the importance of being prepared for disasters, but I do not necessarily apply those things to myself” (EM)

Using 72-h kits as an example, emphasis is often placed on the importance of citizens having kits prepared for themselves and others who may depend on them during a disaster, however many participants disclosed that they do not have kits of their own. The underlying sentiment was one of amusement and lack of urgency, with many participants noting the irony of the lack of uptake. Exploring this issue further revealed that many participants do not feel well supported in terms of their own personal preparedness, which impacts their ability to support the preparedness of others.

“My focus right now is what I can do to make sure that my staff are personally prepared. That is where my head is at right now and I have not even taken it to the step of the general population or vulnerable population” (ESSD)

“I think there needs to be a little more consideration for – if we are going to respond during disasters, we have a world outside of disasters and our response role, that needs to be taken care of first” (EM)

Although preparedness is one of the most prominent phases of emergency management, with much time and funds invested in public campaigns, there is a lack of emphasis on preparedness at the level of EMs and ESSDs. This represents a barrier to their professional response capacity and their ability to support the public. Participants noted that a greater emphasis on personal preparedness is warranted, yet “everything gets trumped by emergencies” (EM). This quotation represented an underlying belief of some of the participants that their personal preparedness remains secondary to the requirements of their job. At the broader level, this has the potential to create vulnerabilities in the emergency management system, as it leaves professionals open to increased stress and burn out; it may further lead to gaps in the system if they are unable to continue working.

Investment and leadership provided by the provincial and federal governments are essential for improved personal preparedness among EMs and ESSDs. One ESSD noted the example of the Public Health Agency of Canada withdrawing their federal funding and leadership in 2010 which then led to the elimination of biannual conferences. The resulting intermittent telephone meetings have not allowed for the same type of discussions surrounding personal preparedness and best practices in the field, creating a knowledge-sharing gap.

Recommendations put forward by participants to increase their own preparedness and therefore capacity, were related to raising awareness of the issue within the EM and ESSD professions. Participants also suggested that increased training opportunities, and increased supports provided by management (i.e. time and resources allocated to preparedness) would go a long way to improving personal preparedness.

3.5. Theme 5: behind the scenes roles can have mental health implications

In the eyes of the public, EMs and ESSDs carry out largely unknown roles. Lack of visibility and recognition have contributed to reduced awareness of the secondary stressors these professionals face when carrying out their day-to-day tasks. In contrast with the services provided by first responders, the contributions of EMs and ESSDs were thought to go unnoticed. As highlighted by participants in this study, first responders are out in the public so citizens are aware of the roles that they carry out, as well as the vulnerabilities they may experience. In contrast, EMs and ESSDs are not highly visible and therefore the roles they carry out and the vulnerabilities that they experience may not be well understood.

“A lot of the time there is just no recognition for what emergency managers do and there is a very poor understanding of the types of secondary stressors we encounter. In my day- to-day role, I am not in the reception center meeting with evacuees, however I am the provinces lead coordinator for social services so the stressors related to that I would put in the extreme category. I have suffered my own mental health issues because of that, but it is very hard to articulate why, because again, you do not have the soot on your face” (ESSD)

“Being a professional or a leader in emergency management doesn't mean that if a disaster strikes you are not going to be impacted, and if you are personally impacted, how does that affect your ability to actually carry out your role as a leader?” (EM)

The burden that comes with managing secondary stressors can have mental health implications for EMs and ESSDs, impacting them both personally and professionally. Common stressors included: meeting public and departmental expectations under resource and time constraints, lack of available and trained personnel to provide relief during peak times, and meeting the demands of the job while also ensuring family safety. Lack of upstream investment in the prevention/mitigation and planning phases puts EMs and ESSDs at risk of experiencing mental health impacts during the response and recovery phases when the demands of their jobs increase.

[In the event of a response], “you get into your position and then you are there for like 10 days and you totally lose track of time, and we find people unconscious in places like stairwells because they just work themselves to death” (ESSD)

“Whenever we are in a response, we are trying to do our best to help the community, but at the same time we forget to eat, we forget to take washroom breaks, we forget to get up from our desks … in an emergency the adrenaline is there and you cannot really focus on your self, you feel a need and duty to help others” (EM)

Due to the demands of their response occupations, EMs and ESSDs should be considered at ‘high-risk’ of experiencing mental illness. In an effort to reduce this risk, participants provided recommendations they believe would support their mental health. In the prevention/mitigation and planning phases it is imperative that multiple individuals be trained to perform the EM or ESSD roles, to enable the work-load to be distributed between multiple people during the response and recovery phases – and to allow for adequate breaks when sustained response is required. Increased opportunities for training in areas such as stress management were also suggested. During the response and recovery periods many participants suggested that having a disaster social services volunteer, counsellor or a therapist available to act as a support for staff would be an asset as “it is crucial to have someone there to look out for you while you are looking out for others” (EM). Some participants noted that these suggestions are already starting to be integrated into protocols in the workplace, while others expressed that they would like to see these suggestions implemented. Finally, bringing increased awareness to the importance of self-care was highlighted as important in order to promote increased coping capacity.

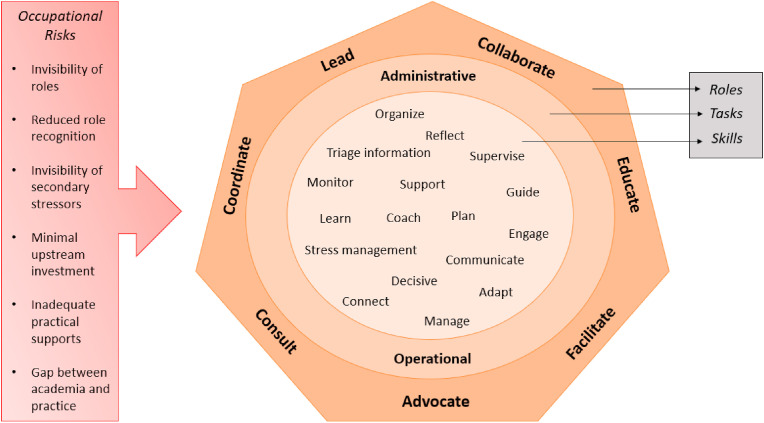

From the five themes identified we created a model to highlight the skills, tasks, and roles that make-up the EM and ESSD occupations, as described by participants. In this model we make explicit the occupational risks that these professionals may experience.

3.6. Model of occupational roles and risks in emergency management and emergency social services

Through the identification of themes from this study, it is apparent that EMs and ESSDs are at an increased risk of experiencing stressors and burnout due to the nature of their work. Supporting awareness and bringing visibility to the important skills, tasks and roles these professionals engage in, as well as the occupational risks they may encounter, is a first step towards reducing vulnerabilities and supporting capability. The following model was developed from the data to provide a visual representation of the roles, tasks, skills that EMs and ESSDs carry out, and occupational risks that they are exposed to. The skills are located at the center of the model as they are required to carry out greater tasks and roles, which are represented in the outer rings, respectively. The six occupational risks identified can impede the ability of EMs and ESSDs to carry out their roles, which are represented in the column with an arrow pointing towards the rings.

The participants mentioned 17 skills required to carry out tasks and roles; they are located in the center ring in Fig. 1 . For example, one essential skill is the ability to be decisive, which is particularly important in the response and recovery phases, when other professionals are dependent upon receiving direction. The ability to be reflexive is another important skill, for instance, in the prevention/mitigation phase in order to acknowledge what worked well – and what could be improved – for future responses.

Fig. 1.

Model of occupational roles and risks in emergency management and emergency social services.

These skills give EMs and ESSDs the ability to carry out administrative and operational tasks as described in themes 1 and 2 respectively; tasks are highlighted in the center ring in Fig. 1. The skills and tasks carried out by EMs and ESSDs build into greater overarching roles. There were seven dynamic roles identified which are represented in the outer ring of Fig. 1 and include: lead, collaborate, educate, facilitate, advocate, consult and coordinate. For example, for EMs and ESSDs at the municipal level, educate and advocate were roles often emphasized to meet the needs of the citizens in their particular jurisdictions. In contrast – at the provincial level – coordination was a focus for managing an intersectoral approach to disaster management.

Finally, six main occupational risks were identified that impact the ability of EMs and ESSDs to carry out the skills, tasks and roles required in the context of these positions. These occupational risks are areas where EMs and ESSDs are vulnerable to experiencing an increased risk of mental health issues. Occupational risks identified included: lack of role awareness, recognition and secondary stressors, lack of upstream investment, lack of practical supports, and a gap between academia and practice. Importantly, occupational risks experienced are likely dependent upon the context of the situation and personal characteristics of the EM/ESSD. With increasing demands placed on EMs and ESSDs due the negative impacts of climate change and widespread pandemics, it is important that occupational stressors are identified to reduce vulnerability and support capability.

4. Discussion

Professions that specialize in disaster and emergency management emerged out of a need for full-time, technically trained individuals to facilitate response and recovery post-disaster [3]. In today's society, EMs and ESSDs engage in a range of roles and tasks that span all four phases of the disaster management cycle, prevention/mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery [3]. The purpose of this study was to explore the current roles of EMs and ESSDs in a Canadian context; we specifically wanted to learn about barriers, vulnerabilities and capabilities experienced by these professionals.

The evolution of emergency management as a profession in Canada, in the most recent decade, was highlighted by participants as an increasing number of individuals have entered into the field with relevant degrees from post-secondary institutions. The professionalization of emergency management has been well documented, particularly in the United States where education and certification programs have existed since the early 1990's [3,17,18]. Oyola-Yemaiel and Wilson [19] note that beyond certification programs, accreditation and hierarchical structure contributes to the professionalization process.

In Canada, disaster and emergency management educational opportunities are growing, with colleges offering diploma and certificate options, and universities offering both bachelor and graduate degrees in the field [20]. Each province and territory have their own emergency management organization and many have provincial/territorial professional associations to foster continued professional development, advocacy, mentorship and networking opportunities [21,22]. Although a national professional association no longer exists, Canada is engaged with the International Association of Emergency Managers, which offers a certification process, promotes profession specific principles and is bound by a code of ethics [18].

In terms of hierarchical structure, EMs and ESSDs are positioned throughout all levels of government and in the private sector, however the formalization of a rank/order (i.e. junior vs senior EM/ESSD, or assistant vs associate EM/ESSD) does not currently exist; this is similar to the United States. Oyola-Yemaiel and Wilson [19] argue that moving from a loose to a formal structure is the next step in the professionalization process. Whether or not this will manifest in the future remains to be seen, but the concept is reminiscent of the command and control style of the profession's origins, which it has moved away from to give way to more collaborative approaches to administration [4]. Waugh and Streib [4] argue that a lack of understanding of emergency management is one of the reasons why people think that a command and control style would strengthen emergency managements response to disasters, when in practice it interferes with a collaborative approach necessary to manage disaster operations.

The public has come to expect that emergency management professionals will carry out their roles effectively and efficiently to respond to their needs before, during, and after a disaster [23]. This requires skill in the ability to facilitate both vertical and horizontal coordination between numerous NGOs, government departments and private companies, as well as a plethora of skills including the ability to adapt, and make hard and fast decisions [23]. The skills, tasks, and roles expected of EMs and ESSDs are superimposed onto bureaucratic systems that remain relatively rigid in their planning, protocols and processes [8,23]. This can make completion difficult – and impacts interoperability – which is a critical function in disasters [24].

Interoperability describes how resources from multiple organizations both work together and talk to each other during a disaster; it is often used as a measure of capability between agencies [24]. However, capability between agencies will be difficult to achieve if those agencies themselves do not have their own capability and capacity. Respondents of this study reported that a lack of upstream investment – and a general lack of support and resources – impede their own capacity to meet the demands of the job.

Many of the respondents hold multiple job titles and describe a “side-of-desk” role where they are only able to devote a small number of working hours to disaster mitigation/prevention and preparedness. This is a chronic issue as many emergency management departments are understaffed and underfunded [8,9]. To combat this issue, many EMs and ESSDs have come to rely on their networks to meet the demands of the job. Networks are mutually beneficial as they lead to shared resources, information, personnel and expertise [25,26]. Respondents in this study noted that they rely heavily on their relationships with NGOs such as The Red Canadian Cross and Salvation Army, as well as with faith-based groups and community-level organizations. Networks can help EMs and ESSDs build back better by bringing individuals and communities to an acceptable new normal post-disaster. These findings are consistent with the calls for emergency management to take on a network governance style approach whereby collaborative practices, rather than hierarchical command and control tactics, are fostered in order to meet the demands of the job, despite economic and financial constraints [8,27]. However, maintaining networks is difficult, particularly when there is no activation ongoing. This speaks to the need for continued upstream investment to promote adequate preparedness.

The lack of upstream investment in disaster mitigation/prevention and preparedness is concerning, given the increased frequency and severity of disasters as a result of climate change [28]. The impact of climate change on emergency management professions is not fully understood, however there has been a shift from focusing on acute hazards to chronic conditions, leaving EMs and ESSDs to support longer recovery periods with minimal support and resources [29,30]. Increased demands, coupled with high public expectations, makes EMs and ESSDs a high-risk group for experiencing mental illness. However, the mental health of these professionals is often overlooked, with the focus remaining on the vulnerabilities of first responders and the greater community [31,32]. The EMs and ESSDs in this study made it clear that unrealistic expectations that come with their “side-of-desk” role, accompanied by invisibility of their roles, and lack of support for personal preparedness is leaving them vulnerable to burnout and stress. Of particular concern is what will happen if these individuals need to take leave as a result of occupational stressors – resulting in a gap in the system that relies on them to carry out an increasing work load. This concern is particularly relevant with the emergence of the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic where plans are changing every day; the impact will be an extensive recovery period.

This study explores the occupational roles and risks of EMs and ESSDs from six Canadian provinces. Gaining perspectives from different regions in Canada is a strength of this study because it incorporates the perceptions of professionals who have different climate-related concerns. However, perspectives from the territories could not be gathered due to ethics approval restrictions. This study also took place before the COVID-19 pandemic; therefore, it was not possible to understand how these findings might be understood in this context.

With the climate crisis, and changes to the landscape of emergency management, additional investment in support and resources are essential to enable EMs and ESSDs to support the greater community. Drabek [33] defined a successful EM as one who could interact effectively with government officials and with the broader disaster relief community. This definition has not been revised over several decades. Here we suggest an updated definition to reflect the current state of emergency management: An effective individual working in emergency management is one whose personal and professional capacity is well supported, such that it allows them to support individuals and communities throughout all phases of the disaster management cycle, to build back better after an adverse community event.

5. Conclusion

Throughout all phases of disaster management, EMs and ESSDs carry out essential roles and tasks to support individuals, citizens, and communities. The increasing demands and high expectations for these professionals are not conducive to the “side-of-desk” nature of these roles. This has implications for continuity of critical operations during an activation if EMs and ESSDs need to leave their work due to occupational stressors and burn out. This has particular relevance in our current society with the increasing frequency and severity of natural disasters due to climate change and the emergence of the world wide COVID-19 pandemic. Future studies should explore how the COVID-19 pandemic will impact the ability of EMs and ESSDs to carry out their roles. Studies should also look at interventions to support the mental health of EMs and ESSDs to promote capacity building in the midst of increasing demands due to climate change and increased frequency and severity of other types of disasters, including pandemics.

Funding

This work was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. The authors would like to acknowledge the participants who took part in the interviews and the co-investigators on the grant (Dr. Melissa Genereux, Dr. Marc D. David, Dr. Marie-Eve Carignan, Dr. Mathieu Roy, Dr. Daniel Lane, and Dr. Genevieve Petit). Many thanks to members of our EnRiCH Lab, Christina Pickering, who assisted with development of the interview guide, Fengzho Hu and Amanda Mac, who provided assistance with transcription, and colleagues who assisted with distributing our recruitment notice to EMs and ESSDs in Canada.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101925.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction [Undrr] Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015-2030. 2015. https://www.preventionweb.net/files/43291_sendaiframeworkfordrren.pdf Retrieved from.

- 2.Public Safety Canada Emergency management strategy for Canada: toward a resilient 2030. 2019. https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/mrgncy-mngmnt-strtgy/mrgncy-mngmnt-strtgy-en.pdf (ISBN 978-0-660-29248-9). Retrieved from Public Safety Canada, Government of Canada.

- 3.Waugh W.L. Routledge; 2015. Living with Hazards, Dealing with Disasters: an Introduction to Emergency Management: an Introduction to Emergency Management. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waugh W.L., Streib G. vol. 66. Public Administration Review; Washington: 2006. p. 131. (Collaboration and Leadership for Effective Emergency Management). (S1) http://dx.doi.org.proxy.bib.uottawa.ca/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00673.x. [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Association of Emergency Managers [IAEM]. (n.d.-a). Principles of emergency management summary. Retrieved from: https://www.iaem.org/portals/25/documents/Principles-of-Emergency-Management-Flyer.pdf.

- 6.Alberta Government . 2016. Provincial emergency social services framework. Retrieved from: http://www.aema.alberta.ca/documents/PESS-Framework-Final-Document-01182016.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Justice Institute of British Columbia [JIBC] Emergency social services emergency management division core function. https://bowenisland.civicweb.net/document/104934/Emergency%20Social%20Service%20Director.pdf?handle=679801C739BE4FB99555D9ACA4884E9D (n.d.)Retrieved from.

- 8.Howes M., Tangney P., Reis K., Grant-Smith D., Heazle M., Bosomworth K., Burton P. Towards networked governance: improving interagency communication and collaboration for disaster risk management and climate change adaptation in Australia. J. Environ. Plann. Manag. 2015;58(5):757–776. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2014.891974. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canadian Red Cross Integrating emergency management and high-risk populations: survey report and action recommendations. 2007. https://www.redcross.ca/crc/documents/3-1-4-2_dm_high_risk_populations.pdf Retrieved from.

- 10.United Nations Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. 2015. https://www.unfpa.org/resources/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development Retrieved from.

- 11.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC] Climate change 2014 synthesis report. 2014. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/05/SYR_AR5_FINAL_full_wcover.pdf Retrieved from.

- 12.Benedek D.M., Fullerton C., Ursano R.J. First responders: mental health consequences of natural and human-made disasters for public health and public safety workers. Annu. Rev. Publ. Health. 2007;28:55–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braun V., Clarke V., Hayfield N., Terry G. In: Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Liamputtong P., editor. Springer Singapore; 2019. Thematic analysis; pp. 843–860. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terry G., Hayfield N., Clarke V., Braun V. In: The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology. Willig C., Rogers W.S., editors. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2017. Thematic analysis; pp. 17–36. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waugh W.L., Sadiq A.-A. Professional education for emergency managers. J. Homel. Secur. Emerg. Manag. 2011;8(2) doi: 10.2202/1547-7355.1891. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.International Association of Emergency Managers [IAEM]. (n.d.-b). IAEM Canada council leadership. IAEM. Retrieved from: https://www.iaem.org/council/canada/leadership.

- 19.Oyola-Yemaiel A., Wilson J. Three essential strategies for emergency management professionalization in the U. S. Int. J. Mass Emergencies Disasters. 2005;8 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canadian Risk and Hazards Network [CRHNet] Education Canadian academic programs in disaster and emergency management. Canada risk and hazards network. https://www.crhnet.ca/resources/education (n.d)Retrieved from.

- 21.Government of Canada Emergency management organizations. Government of Canada get prepared. 2015. https://www.getprepared.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/mrgnc-mgmt-rgnztns-en.aspx Jan 15. Retrieved from.

- 22.Ontario Association of Emergency Managers [OAEM] About the OAEM. OAEM Home of the Ontario emergency management community. https://oaem.ca/about-us/ (n. d)Retrieved from.

- 23.Kapucu N., Arslan T., Demiroz F. Collaborative emergency management and national emergency management network. Disaster Prevention and Management; Bradford. 2010;19(4):452–468. doi: 10.1108/09653561011070376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rauner M.S., Niessner H., Odd S., Pope A., Neville K., O'Riordan S., Sasse L., Tomic K. An advanced decision support system for European disaster management: the feature of the skills taxonomy. Cent. Eur. J. Oper. Res.: CEJOR; Heidelberg. 2018;26(2):485–530. http://dx.doi.org.proxy.bib.uottawa.ca/10.1007/s10100-018-0528-9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kapucu N., Garayev V. Designing, managing, and sustaining functionally collaborative emergency management networks. Am. Rev. Publ. Adm. 2013;43(3):312–330. doi: 10.1177/0275074012444719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kapucu N., Hu Q. Understanding multiplexity of collaborative emergency management networks. Am. Rev. Publ. Adm. 2016;46(4):399–417. doi: 10.1177/0275074014555645. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bosomworth K., Owen C., Curnin S. Addressing challenges for future strategic-level emergency management: reframing, networking, and capacity-building. Disasters. 2017;41(2):306–323. doi: 10.1111/disa.12196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Sullivan T.L., Kuziemsky C.E., Toal-Sullivan D., Corneil W. Unraveling the complexities of disaster management: a framework for critical social infrastructure to promote population health and resilience. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013;93:238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Labadie J.R. Emergency managers confront climate change. Sustainability. 2011;3(8):1250–1264. doi: 10.3390/su3081250. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCreight R., Harrop W. Uncovering the real recovery challenge: what emergency management must do. J. Homel. Secur. Emerg. Manag. 2019;16(3) doi: 10.1515/jhsem-2019-0024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldmann E., Galea S. Mental health consequences of disasters. Annu. Rev. Publ. Health. 2014;35(1):169–183. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haugen P.T., McCrillis A.M., Smid G.E., Nijdam M.J. Mental health stigma and barriers to mental health care for first responders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2017;94:218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drabek T.E. University of Colorado Institute of Behavioral Science; Boulder: 1987. The Professional Emergency Manager, Monograph 44. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.