Abstract

Reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) is a curative option for select relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) patients, however there is sparse data to support superiority of any particular conditioning regimen.

We analyzed 492 adult patients undergoing HLA-matched sibling or unrelated donor allo-HCT for HL between 2008–2016, utilizing RIC with either fludarabine/busulfan (Flu/Bu), fludarabine/melphalan (Flu/Mel140) or fludarabine/cyclophosphamide (Flu/Cy). Multivariable regression analysis was performed using a significance level of <0.01. There were no significant differences between regimens in risk for non-relapse mortality (NRM) (P=0.54), relapse/progression (P=0.02) or progression-free survival (PFS) (P=0.14). Flu/Cy conditioning was associated with decreased risk of mortality in the first 11months after allo-HCT (HR=0.28, 95%CI=0.10–0.73, p=0.009), but beyond 11months post allo-HCT it was associated with a significantly higher risk of mortality, (HR=2.46, 95%CI=0.1.32–4.61, P=0.005). 4-year adjusted overall survival (OS) was similar across regimens at 62% for Flu/Bu, 59% for Flu/Mel140 and 55% for Flu/Cy (P=0.64), respectively.

These data confirm the choice of RIC for allo-HCT in HL does not influence risk of relapse, NRM or PFS. Although no OS benefit was seen between Flu/Bu and Flu/Mel 140; Flu/Cy was associated with a significantly higher risk of mortality beyond 11months from allo-HCT (possibly due to late NRM events).

Keywords: reduced-intensity conditioning, allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant, classical Hodgkin lymphoma

Graphical Abstarct

INTRODUCTION

The majority of classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) patients have excellent prognosis with conventional frontline therapies. However patients with relapsed or refractory disease have less favorable outcomes. A substantial proportion of relapsed patients with chemosensitive disease are successfully salvaged with an autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), but up to 40–50% of patients will relapse after autografting and have very poor outcomes, with a 5-year overall survival (OS) of ~30%.(1–3) Allogeneic HCT (allo-HCT) is a potentially curative approach for these patients with 5-year OS ranging from 30–50%.(4–8) While allo-HCT with myeloablative conditioning (MAC) can provide durable disease control in patients with HL, these higher intensity approaches have been associated with higher rates of non-relapse mortality (NRM) in most,(9–11) but not all studies(12), and have never been shown to provide an OS benefit (12).

Reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens have extended the use of allo-HCT to patients who relapse after autologous HCT, older patients and those with significant comorbidities.(13–16) While a handful of retrospective studies have compared different RIC or non-myeloablative (NMA) conditioning platforms in lymphoma patients (17, 18), these analyses were not limited to the diagnosis of HL. Unlike non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL), where the median age of recipients at allo-HCT is usually in the late 50s(19, 20), the median age of HL patients at allo-HCT is typically in the mid 30s.(6, 12) It is possible that these much younger HL patients may be able to tolerate more dose-intense RIC regimens better than older NHL patients, and potentially may derive a survival benefit with such approaches. Using the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) database we evaluated the outcomes of the three most commonly used RIC/NMA regimens for HL.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data source

CIBMTR is a working group of more than 500 transplantation centers worldwide that contribute detailed data on HCT to a statistical center at the Medical College of Wisconsin. Participating centers are required to report all transplantations consecutively; patients are followed longitudinally, and compliance is monitored by on-site audits. Computerized checks for discrepancies, physicians’ review of submitted data, and on-site audits of participating centers ensure data quality. The CIBMTR collects data at two levels, transplant essential data (TED) in all patients and more comprehensive data (CRF) in a subset of patients selected by a weighted randomization scheme. Observational studies conducted by the CIBMTR are performed in compliance with all applicable federal regulations pertaining to the protection of human research participants. Protected Health Information used in the performance of such research is collected and maintained in CIBMTR’s capacity as a Public Health Authority under the HIPAA Privacy Rule. The Institutional Review Boards of the Medical College of Wisconsin and the National Marrow Donor Program approved this study.

Patients

Patients with HL aged ≥18 years undergoing their first NMA or RIC allo-HCT, between 2008 and 2016 and reported to CIBMTR were included in this analysis. Donors were limited to HLA-matched sibling (MSD) or 8/8 HLA-matched unrelated donors (MUD). Following 3 most commonly used RIC regimens were analyzed: fludarabine (median dose=150mg/m2)/i.v. busulfan (~6.4mg/kg) (Flu/Bu), fludarabine (median dose=125mg/m2)/melphalan 140mg/m2 (Flu/Mel140) or fludarabine (median dose=120mg/m2)/cyclophosphamide (median dose=1200mg/m2) (Flu/Cy). Patients receiving Flu/Cy/2Gray total body irradiation (n=15) were not included in this analysis. Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis was restricted to calcineurin inhibitor (CNI)-based approaches. Graft source was limited to peripheral blood. Allo-HCT recipients could have received in vivo T-cell depletion with antithymocyte globulin (ATG) or alemtuzumab. Patients receiving ex vivo graft manipulation were not included.

Definitions & Study Endpoints

The intensity of allo-HCT conditioning regimens was categorized as NMA/RIC using consensus criteria.(21) Disease response at the time of HCT was determined using the International Working Group criteria in use during the era of this analysis.(22) The primary endpoint was OS; death from any cause was considered an event and surviving patients were censored at last follow up. Secondary outcomes included NRM, progression/relapse, and PFS. NRM was defined as death without evidence of lymphoma progression/relapse; relapse was considered a competing risk. Progression/relapse was defined as progressive lymphoma after HCT or lymphoma recurrence after a complete remission (CR); NRM was considered a competing risk. For PFS, a patient was considered a treatment failure at time of progression/relapse or death from any cause. Patients alive without evidence of disease relapse or progression were censored at last follow-up. Acute GVHD and chronic GVHD were graded using established clinical criteria.(23, 24) Probabilities of PFS and OS were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier estimates. Neutrophil recovery was defined as the first of 3 successive days with ANC ≥500/μL after post-transplantation nadir. Platelet recovery was considered to have occurred on the first of three consecutive days with platelet count 20,000/μL or higher, in the absence of platelet transfusion for 7 consecutive days. For neutrophil and platelet recovery, death without the event was considered a competing risk.

Statistical Analysis

The Flu/Bu cohort was compared against the Flu/Cy and Flu/Mel140 cohorts. Cumulative incidences of hematopoietic recovery, GVHD, relapse, and NRM were calculated to accommodate for competing risks. Associations among patient-, disease, and transplantation-related variables and outcomes of interest were evaluated using Cox proportional hazards regression for chronic GVHD, relapse, NRM, PFS, and OS and logistic regression for acute GVHD. Forward stepwise selection was used to identify covariates that influenced outcomes. Covariates with a p<0.01 were considered significant to account for multiple testing. The proportional hazards assumption for Cox regression was tested by adding a time-dependent covariate for each risk factor and each outcome. Interactions between the main effect and significant covariates were examined. Center effect was tested using the score test for chronic GVHD, relapse, NRM, PFS, and OS and the generalized linear mixed model for acute GVHD.(25) Results are expressed as odds ratio (OR) for acute GVHD and hazard ratio (HR) for chronic GVHD, relapse, NRM, PFS, and OS. The variables considered in multivariate analysis are shown in Table 1S of supplemental appendix. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics:

Four hundred and ninety-two adult HL patients underwent a first allo-HCT using either a MSD or MUD between 2008–2016. The study population was divided in 3 cohorts for analysis: Flu/Bu (n=102), Flu/Mel140 (n=318) and Flu/Cy (n=72). Baseline patient-, disease-, and transplantation-related characteristics are shown in Table 1. The 3 groups were comparable with respect to patient age, gender, race, Karnofsky performance score (KPS), median time from diagnosis to allo-HCT, donor type and history of prior autologous HCT. The HCT-comorbidity index (HCT-CI) of ≥3 was more frequent in the Flu/Bu cohort compared to Flu/Mel140 and Flu/Cy; 55% vs 32% vs 31% respectively (p<0.001). ATG or alemtuzumab use with conditioning regimen was more frequent in Flu/Bu (36%) and Flu/Mel140 (27%) cohorts compared to Flu/Cy (7%; p<0.001). CNI and methotrexate-based GVHD prophylaxis was less frequent in the Flu/Cy cohort, while CNI and mycophenolate mofetil-based prophylaxis was less commonly used in the Flu/Mel140 group. The median follow up of survivors was 47 (range 3–101) months, 49 (range 3–121) months and 60 (range 3–97) months in the Flu/Bu, Flu/Mel140 and the Flu/Cy groups respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Flu/Bu | Flu/Mel140 | Flu/Cy | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 102 | 318 | 72 | |

| Median patient age, years(range) | 33 (19–69) | 33 (18–70) | 33 (19–61) | 0.18 |

| Male gender | 69 (68) | 182 (57) | 43 (60) | 0.18 |

| Patient race | 0.33 | |||

| Caucasian | 94 (92) | 272 (86) | 60 (83) | |

| Other | 8 (8) | 44 (14) | 12 (17) | |

| Missing | 0 | 2 (<1) | 0 | |

| Karnofsky performance score ≥ 90 | 70 (69) | 240 (75) | 52 (72) | 0.07 |

| Missing | 0 | 13 (4) | 3 (4) | |

| HCT-CI | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 25 (25) | 134 (42) | 35 (49) | |

| 1–2 | 21 (21) | 78 (25) | 11 (15) | |

| ≥ 3 | 56 (55) | 102 (32) | 22 (31) | |

| Missing | 0 | 4 (1) | 4 (6) | |

| Remission status at HCT | 0.23 | |||

| Complete remission | 40 (39) | 134 (42) | 18 (25) | |

| Partial remission | 42 (41) | 136 (43) | 36 (50) | |

| Resistant | 18 (18) | 39 (12) | 16 (22) | |

| Missing/Unknown | 2 (2) | 9 (3) | 2(3) | |

| Prior autologous HCT | 91 (89) | 271 (85) | 60 (83) | |

| Median time from diagnosis to transplant, months | 32 (4–201) | 33 (3–276) | 39 (13–250) | 0.17 |

| Donor type | 0.06 | |||

| Matched sibling donor | 48 (47) | 175 (55) | 47 (65) | |

| Matched unrelated donor | 54 (53) | 143 (45) | 25 (35) | |

| GVHD prophylaxis | <0.001 | |||

| CNI + MMF +- other(s) | 30 (29) | 34 (11) | 18 (25) | |

| CNI + MTX +- other(s) | 58 (57) | 202 (64) | 35 (49) | |

| CNI + other(s) | 14 (14) | 82 (26) | 19 (26) | |

| ATG/alemtuzumab use in conditioning | 37 (36)* | 87 (27)* | 5 (7)* | <0.001 |

| CMV status Donor/Recipient | 0.75 | |||

| +/− | 18 (18) | 40 (13) | 10 (14) | |

| Other | 82 (80) | 274 (86) | 62 (86) | |

| Missing | 2 (2) | 4 (1) | 0 | |

| Year of transplant | 0.03a | |||

| 2008–2011 | 36 (35) | 133 (42) | 40 (56) | |

| 2012–2016 | 66 (65) | 185 (58) | 32 (44) | |

| Median follow-up of survivors (range), months | 47 (3–101) | 49 (3–121) | 60 (3–97) |

Hypothesis testing:

Pearson chi-square test

Abbreviations:CNI=calcineurin inhibitor; CMV=Cytomegalovirus; Cy=cyclophosphamide; Flu=fludarabine; Bu=Busulfan; HCT-CI=hematopoietic cell transplant-comorbidity index; Mel=melphalan; MMF=mycophenolate mofetil; MTX=methotrexate

The median total dose and type of ATG in each conditioning cohort was as following: Flu/Bu (Horse ATG=60mg/kg; Rabbit ATG=6mg/kg); Flu/Mel140 (Horse ATG=45mg/kg; Rabbit ATG=5mg/kg) and Flu/Cy (Horse ATG=45mg/kg; Rabbit ATG=5mg/kg). Median total alemtuzumab dose with Flu/Mel140 was 40mg.

Hematopoietic Recovery:

The day 30 cumulative incidence of neutrophil recovery for the Flu/Bu patients was 100% (95%CI=100–100) compared 97% (95%CI=95–99) for the Flu/Mel140 group and 99% (95%CI=95–100) for the Flu/Cy group (P=0.01). The day 100 cumulative incidence of platelet recovery in the same order was 100% (95%CI=100–100), 97% (95%CI=95–99) and 99% (95%CI=95–100) (P=0.01); Table 2), respectively.

Table 2.

Univariate and adjusted probabilities of outcomes of NMA/RIC patients receiving first allo-HCT for HL 2008–2016

| Flu/Bu (N = 102) |

Flu/Mel 140 (N = 318) |

Flu/Cy (N = 72) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | N Eval | Prob (95% CI) | N Eval | Prob (95% CI) | N Eval | Prob (95% CI) | p-value |

| Neutrophil recovery | 100 | 312 | 71 | ||||

| 30 days | 100 (100–100)% | 97 (95–99)% | 99 (95–100)% | 0.010 | |||

| Platelet recovery | 100 | 310 | 67 | ||||

| 100-day | 100 (100–100)% | 97 (95–99)% | 99 (95–100)% | 0.010 | |||

| Grade 2–4 acute GVHD | 100 | 301 | 66 | ||||

| 180 days | 46 (36–56)% | 34 (29–40)% | 26 (16–37)% | 0.02 | |||

| Grade 3–4 acute GVHD | 99 | 301 | 65 | ||||

| 180 days | 16 (10–24)% | 15 (11–19)% | 12 (6–21)% | 0.77 | |||

| Chronic GVHD | 99 | 302 | 68 | ||||

| 1-year | 50 (41–60)% | 49 (43–54)% | 43 (31–54)% | 0.56 | |||

| GRFS | 99 | 301 | 65 | ||||

| 2-year | 21 (14–30)% | 25 (20–30)% | 29 (18–41)% | 0.45 | |||

| Adjusted Non-relapse mortality | 102 | 317 | 72 | ||||

| 1-year | 10 (4–16)% | 10 (7–14)% | 3 (0–7)% | 0.02 | |||

| 4-year | 15 (7–23)% | 17 (13–22)% | 12 (3–21)% | 0.51 | |||

| Adjusted Relapse/Progression | 102 | 317 | 72 | ||||

| 1-year | 40 (30–49)% | 34 (29–39)% | 48 (38–59)% | 0.05 | |||

| 4-year | 57 (47–67)% | 47 (41–53)% | 65 (53–76)% | 0.01 | |||

| Adjusted Progression-free Survival | 102 | 317 | 72 | ||||

| 1-year | 50 (41–60)% | 56 (51–61)% | 48 (37–59)% | 0.36 | |||

| 4-year | 29 (20–38)% | 37 (31–43)% | 25 (14–35)% | 0.07 | |||

| Adjusted Overall survival | 102 | 318 | 72 | ||||

| 1-year | 78 (70–86)% | 84 (79–88)% | 93 (87–99)% | 0.005 | |||

| 4-year | 62 (52–73)% | 59 (53–65)% | 55 (42–67)% | 0.64 | |||

Abbreviations:Eval=evaluable; GVHD=graft-versus-host disease; GRFS=GVHD-free, relapse-free survival; N=number; Prob=probability.

Graft-vs-Host-Disease:

On univariate analysis, the day 180 cumulative incidence grade 2–4 acute GVHD was 46% (95%CI=36–56) with Flu/Bu, 34% (95%CI=29–40) with Flu/Mel140 and 26% (95%CI=16–37) with Flu/Cy (P=0.02; Table 2). Grade 3–4 acute GVHD in the same order was 16% (95%CI=10–24), 15% (95%CI=11–19), and 12% (95%CI=6–21) respectively (P=0.77). On multivariate analysis, the risk of grade 3–4 acute GVHD was not significantly different across the three conditioning cohorts (P=0.79; Table 3)

Table 3.

Main effect of multivariate analysis.

| N | HR | 95% CI Lower Limit | 95% CI Upper Limit | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 3–4 acute GVHD | |||||

| Conditioning regimen | |||||

| Flu/Bu | 99 | 1 | 0.79 | ||

| Flu/ Mel 140 | 301 | 0.89 | 0.48 | 1.66 | |

| Flu/Cy | 65 | 0.73 | 0.29 | 1.82 | |

| Chronic GVHD | |||||

| Conditioning regimen | |||||

| Flu/Bu | 100 | 1 | 0.12 | ||

| Flu/ Mel 140 | 305 | 0.88 | 0.65 | 1.18 | |

| Flu/Cy | 69 | 0.65 | 0.43 | 0.99 | |

| Chronic GVHD adjusted for significant covariate: ATG/alemtuzumab use in conditioning. | |||||

| Non-relapse mortality (NRM) | |||||

| Conditioning regimen | |||||

| Flu/Bu | 102 | 1 | 0.54 | ||

| Flu/ Mel 140 | 317 | 1.21 | 0.66 | 2.23 | |

| Flu/Cy | 72 | 0.83 | 0.34 | 2.05 | |

| NRM adjusted for significant covariates: patient age and donor type. | |||||

| Progression/relapse | |||||

| Conditioning regimen | |||||

| Flu/Bu | 102 | 1 | 0.02 | ||

| Flu/ Mel 140 | 318 | 0.73 | 0.53 | 1.00 | |

| Flu/Cy | 72 | 1.13 | 0.76 | 1.66 | |

| Progression/relapse adjusted for significant covariate: remission status at HCT. | |||||

| Progression free survival | |||||

| Conditioning regimen | |||||

| Flu/Bu | 102 | 1 | 0.14 | ||

| Flu/ Mel 140 | 318 | 0.82 | 0.62 | 1.08 | |

| Flu/Cy | 72 | 1.06 | 0.75 | 1.51 | |

| Progression free survival adjusted for significant covariate: remission status at HCT. | |||||

| Overall Survival | |||||

| Conditioning regimen ≤ 11*** months | |||||

| Flu/Bu | 102 | 1 | 0.03 | ||

| Flu/ Mel 140 | 318 | 0.80 | 0.49 | 1.32 | 0.39 |

| Flu/Cy | 72 | 0.28 | 0.10 | 0.73 | 0.009 |

| Conditioning regimen > 11 months*** | |||||

| Flu/Bu | 78 | 1 | 0.02 | ||

| Flu/ Mel 140 | 256 | 1.62 | 0.93 | 2.82 | 0.09 |

| Flu/Cy | 64 | 2.46 | 1.32 | 4.61 | 0.005 |

| Overall survival adjusted for significant covariate: remission status at HCT. | |||||

The 11-months was chosen as the cut-off OS based on the maximum likelihood value in the Cox model.

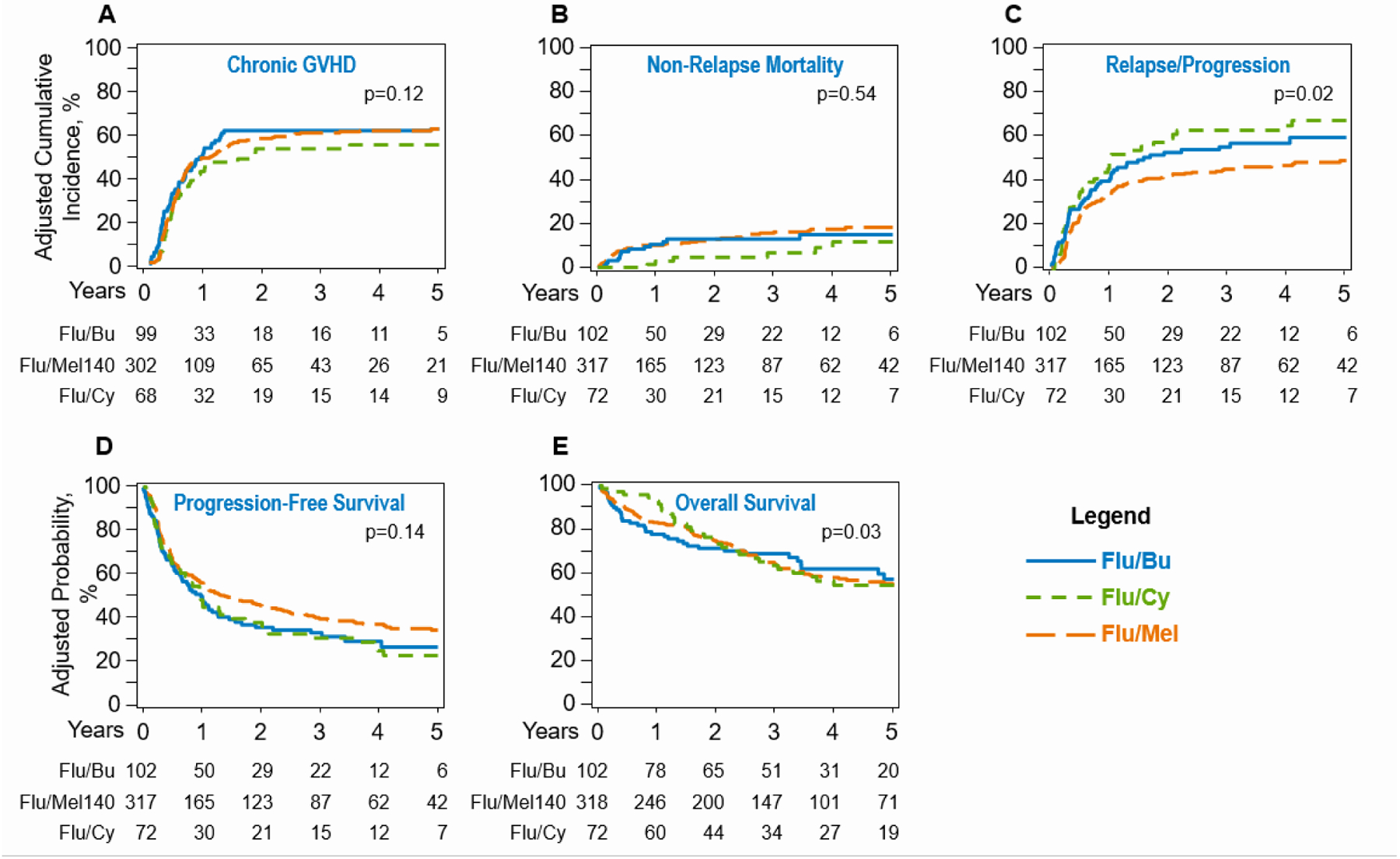

The 1-year cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD on univariate analysis was 50% (95%CI=41–60), 49% (95%CI=43–54), and 43 (95%CI=31–54) for Flu/Bu, Flu/Mel140 and Flu/Cy cohorts, respectively (P=0.56). On multivariate analysis, after adjusting for ATG/alemtuzumab use, the risk of chronic GVHD was not significantly different across the three conditioning cohorts (P=0.12; Table 3, Fig1a). GVHD-free, relapse-free survival is shown in Table 2.

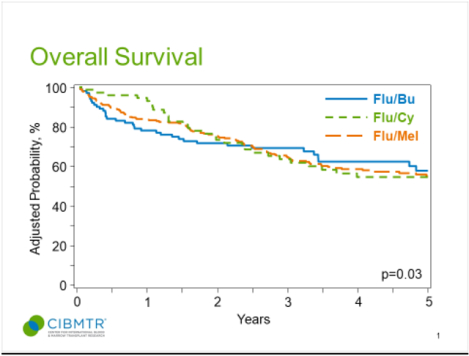

Fig 1.

(A) Cumulative incidence of chronic graft-versus-host-disease (overall, P= 0.12). (B) Cumulative incidence of non-relapse mortality (overall, P = 0.54). (C) Cumulative incidence of relapse and/or progression in recipients of Flu/Bu, Flu/Cy and Flu/Mel140 transplantations (overall, P= 0.02). (D) Kaplan-Meier estimate of progression-free survival (PFS) (overall, P = 0.14). (E) Kaplan-Meier estimate of overall survival (OS) (overall, P = 0.03).

Non-relapse Mortality and Relapse:

The adjusted cumulative incidence of NRM at 1-year in the Flu/Bu, Flu/Mel140 and Flu/Cy cohorts was 10% (95%CI=4–16) vs. 10% (95%CI=7–14) vs. 3% (95%CI= 0–7), respectively (P=0.02) (Table 2). On multivariable analysis, after adjusting for patient age and donor type, no significant difference was seen between the three groups in terms of NRM risk (P=0.54; Table 3, Fig 1b, for details of multivariate analysis refer to Table 2S).

The adjusted probability of relapse/progression at 4-years for the Flu/Bu, Flu/Mel140 and Flu/Cy cohorts was 57% (95%CI=47–67), 47% (95%CI=41–53) and 65% (95%CI=53–76), respectively (p=0.01; Table 2). On multivariate analysis after adjusting for remission status at the time of HCT, relative to Flu/Bu conditioning the risk of relapse following Flu/Mel140 conditioning (HR=0.73; 95%CI=0.53–1.00; P=0.05), or Flu/Cy conditioning (HR=1.13; 95%CI=0.76–1.66; P=0.55) was not significantly different (Table 3, Fig 1c). Additional factors predictive of relapse/progression risk included disease status and are shown in Table 2S.

Progression-free Survival:

The adjusted probability of PFS at 4-years for the Flu/Bu, Flu/Mel140 and Flu/Cy cohorts was 29% (95%CI=20–38), 37% (95%CI=31–43) and 25% (95%CI=14–35), respectively (p=0.07; Table 2). On multivariate analysis after adjusting for remission status at the time of HCT, relative to Flu/Bu conditioning the risk of therapy failure (inverse of PFS) following Flu/Mel140 conditioning (HR=0.82; 95%CI=0.62–1.08; P=0.16), or Flu/Cy conditioning (HR=1.06; 95%CI=0.76–1.66; P=0.74) was not significantly different (Table 3, Fig 1d). Patients in partial remission at allo-HCT (HR=1.93; P<0.001) and those with resistant disease (HR=2.90; P<0.001) also had higher risk of therapy-failure (Table 2S).

Overall Survival:

The adjusted probability of OS at 4-years for the Flu/Bu, Flu/Mel140 and Flu/Cy cohorts was 62% (95%CI=52–73), 59% (95%CI=53–65) and 55% (95%CI=42–67), respectively (p=0.64; Table 2). On multivariate analysis, the proportional hazards assumption for Cox regression model for OS was violated. Thus, a piecewise proportional hazards model was built, where the best cutoff of 11months (post allo-HCT) was selected based on the maximum likelihood method. Relative to Flu/Bu, the Flu/Cy conditioning was associated with a decreased risk of mortality in the first 11months after allo-HCT (HR=0.28, 95%CI=0.10–0.73, p=0.009), but beyond 11months post allo-HCT, Flu/Cy was associated with a significantly higher risk of mortality, (HR=2.46, 95%CI=0.1.32–4.61, p=0.005; TABLE 3, Fig 1e). No difference in mortality risk was seen between Flu/Bu and Flu/Mel140 cohorts. Patients in partial remission at allo-HCT (HR=1.73; P=0.001) and those with resistant disease (HR=2.08; P<0.001) also had higher risk of mortality (Table 2S).

No center effect was seen for any outcomes. The p-values for relapse, NRM, PFS, and OS are 0.89, 0.19, 0.47 and 0.78, respectively.

Causes of Death:

Relapse was the leading cause of death for all groups, accounting for 19 (51%) of Flu/Bu, 50 (39%) of Flu/Mel140 and 18 (53%) of Flu/Cy cohort deaths. Infections accounted for 3%, 13% and 12% of deaths in Flu/Bu, Flu/Mel140 and Flu/Cy cohorts. GVHD was the main cause of death in 5% of Flu/Bu, 8% of Flu/Mel140 and 3% of the Flu/Cy group. Detailed information about causes of death is shown in Table 3S.

DISCUSSION

Allogeneic HCT is a frequently considered treatment option in heavily pretreated HL patients, including those relapsing after a prior autologous HCT. Previous data comparing MAC versus RIC allo-HCT for HL, have not shown a superiority of MAC approaches over the lower intensity options.(9, 10, 12) In this manuscript we report the outcomes of patients undergoing RIC HCT specifically for HL, a patient population that is demonstrably younger at the time of allo-HCT compared to other lymphoma patients and in which the merits of various RIC platforms are not known. The main findings of our study are as follows: (1) the most commonly used RIC regimen in allo-HCT for HL is Flu/Mel140 which was compared to Flu/Bu and Flu/Cy, the next most frequently used regimens; (2) the choice of conditioning regimen did not confer any benefit in terms of the risk of relapse, decrease in NRM or improvement in PFS; and (3) Flu/Cy was associated with a significantly higher risk of mortality in patients beyond 11 months from allo-HCT.

Sureda et al., (13) compared RIC to MAC in HL for the lymphoma working party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) and showed a significantly decreased incidence of NRM and improved OS in the RIC group. Of note, the in the most recent EBMT study on difference in NRM rates between MAC and RIC approaches was seen.(12) While prior EBMT and CIBMTR registry studies have reported outcomes of HL patients undergoing RIC allo-HCT, none of these studies compared different RIC regimens.(26, 27) The EBMT analysis reported 3-year OS was 29% and PFS of 25%, which is considerably lower than our current analysis, though the study included patients at an earlier time period (1995 and 2005). The CIBMTR study (27) showed a 2-year PFS of 20%, OS of 37%, and NRM of 33%. The outcomes in our current analysis across the 3 regimens studied at 4 years surpass those previously reported with PFS of 25–37%, OS of 55–62% and NRM of 12–17% respectively, but with similar relapse rate of 47–65% at 4 years. NRM of allo-HCT in young HL patients has dramatically improved but this fact is often under appreciated. The NRM rates our study are comparable to the NRM rates reported by other contemporaneous studies. (11). The recent CIBMTR analysis of alternative donor allo-HCT for HL noted a NRM for T cell–replete related donor haploidentical HCT of 11% (95% CI, 6 to 17) compared with 6% (95% CI, 4 to 8) in the MSD/CNI group.(6) Alvarez et al.(28), prospectively evaluated 40 patients who underwent RIC allo-HCT utilizing Flu/Mel140 and demonstrated a 2-year OS of 52% and PFS of 34% with 1-year NRM of 25%. Peggs et al. (29) prospectively treated 49 patients with relapsed HL with Flu/Mel140 and reported 4-year OS and PFS of 55% and 39%. Of note, in our study there was a non-significant trend towards a lower relapse rate with the Flu/Mel140 relative to Flu/Bu (HR=0.73, 95%CI=0.53–1.00; Table 3).

The Flu/Cy arm in our study on multivariate analysis, was associated with decreased risk of mortality, compared to Flu/Bu in first 11 months after allo-HCT (OR 0.28, 95%CI 0.10–0.73, p=0.009), but beyond 11 months post allo-HCT it was associated with a significantly higher risk of mortality, (OR 2.46, 95%CI 0.1.32–4.61, p=0.005). To further investigate the reason for increased mortality in Flu/Cy patients beyond 11months, we evaluated NRM, relapse/progression, and PFS for the group before and after 11month cutoff. Comparing ≤11months vs. >11months the direction and magnitude of HR changes for NRM (HR=0.27 vs. 2.87), relapse/progression (HR=1.1 vs. 1.3) and PFS (HR=0.91 vs. 1.5) in Flu/Cy cohort suggest late NRM (as opposed to late relapses) as the main driver of increased late mortality risk. However, deciphering the exact reasons driving this higher late NRM and overall mortality using cause of death data reported to registry is limited, as previously published.(30)

The rate of acute and chronic GVHD was similar across arms after adjustment for ATG/alemtuzumab use in conditioning and GVHD prophylaxis. We did not see any increase in the rates of acute GVHD with the Flu/Mel cohort as has been reported by Kekre et al., when comparing Flu/Mel and Flu/Bu RIC regimens in patients with lymphoma. Their cohort included HL, as well as indolent and aggressive NHL and the patients had a higher median age at the time of allo-HCT.(18)

In contrast to NHL patients who tend to be much older at the time of allo-HCT (median age in 50s-60s), HL patients are typically younger (6); this holds true in this analysis with the median age of our cohort being 33 years old. These younger patients theoretically may tolerate more intense RIC approaches (e.g. Flu/Mel140) better. For example a recent study showed higher NRM and inferior OS with Flu/Mel140 (arguably a more intense RIC) compared to Flu/Bu in an older predominantly NHL population.(18) In the current analysis, likely owing to the much younger median age of HL patients, no significant difference in the NRM risk was seen between more intense RIC approach (Flu/Mel140) and less intense approaches (Flu/Bu, Flu/Cy).

Recent data suggest that patients with both pre allo-HCT and post allo-HCT exposure to checkpoint inhibitors (CPI) may have an increased risk of acute GVHD.(31–33) In the CIBMTR registry, detailed information about pre-transplant chemotherapy treatments is available only for patients reported at the CRF level (as described in the methods sections under the “Data Source” subheading). Only 24 subjects in the current report were reported at the CRF level, which precludes our ability to see if prior CPI exposure would interact with specific RIC platforms. Similar to other registry-based studies there are limitations inherent to this analysis. Our analysis cannot adjust for unknown factors that would have prompted a center to choose one RIC regimen over another. The nature of data captured in the CIBMTR registry does not allow us to adequately assess the number or type pf pre-transplant salvage regimens, including CPI exposure. However, as opposed to GVHD prophylaxis approaches (e.g. post-transplant cyclophosphamide) (6, 34), no data are available to suggest superiority of one RIC platform over another in CPI exposed HL patients. We advise caution in extrapolating the results of the current analysis to HL patients undergoing haploidentical allo-HCT.(6, 7, 35, 36)

Our analysis shows that the choice of RIC conditioning regimen does not impact the risk of NRM, relapse, PFS or risk of GVHD in HL patients undergoing allo-HCT, with one potential exception. Flu/Cy appears to be associated with a higher delayed risk of late NRM and worse OS. Relapse remains the most common form of therapy failure after allo-HCT in HL. Continued efforts are essential to develop better strategies for disease control for this patient population in both pre- and post- HCT settings.(37)

Supplementary Material

Key Points:

In classical HL patients, three common RIC regimens (Flu/Bu vs. Flu/Mel140 vs. Flu/Cy) had no difference in NRM, relapse and PFS.

RIC allogeneic HCT with Flu/Cy was associated with higher late overall mortality risk, relative to Flu/Bu.

Acknowledgement:

The CIBMTR is supported primarily by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U24CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); a Grant/Cooperative Agreement 4U10HL069294 from NHLBI and NCI; a contract HHSH250201200016C with Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA/DHHS); two Grants N00014-17-1-2388 and N00014-16-1-2020 from the Office of Naval Research; and grants from *Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; *Amgen, Inc.; *Amneal Biosciences; *Angiocrine Bioscience, Inc.; Anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; Astellas Pharma US; Atara Biotherapeutics, Inc.; Be the Match Foundation; *bluebird bio, Inc.; *Bristol Myers Squibb Oncology; *Celgene Corporation; Cerus Corporation; *Chimerix, Inc.; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Gamida Cell Ltd.; Gilead Sciences, Inc.; HistoGenetics, Inc.; Immucor; *Incyte Corporation; Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC; *Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Juno Therapeutics; Karyopharm Therapeutics, Inc.; Kite Pharma, Inc.; Medac, GmbH; MedImmune; The Medical College of Wisconsin; *Merck & Co, Inc.; *Mesoblast; MesoScale Diagnostics, Inc.; Millennium, the Takeda Oncology Co.; *Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; National Marrow Donor Program; *Neovii Biotech NA, Inc.; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd. - Japan; PCORI; *Pfizer, Inc; *Pharmacyclics, LLC; PIRCHE AG; *Sanofi Genzyme; *Seattle Genetics; Shire; Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; St. Baldrick’s Foundation; *Sunesis Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Swedish Orphan Biovitrum, Inc.; Takeda Oncology; Telomere Diagnostics, Inc.; and University of Minnesota. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

*Corporate Members

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

Mehdi Hamadani reports Research Support/Funding: Spectrum Pharmaceuticals; Astellas Pharma. Consultancy: MedImmune LLC; Janssen R &D; Incyte Corporation; ADC Therapeutics; Celgene Corporation; Pharmacyclics. Speaker’s Bureau: Sanofi Genzyme.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mariotti J, Devillier R, Bramanti S, Sarina B, Furst S, Granata A, et al. T Cell-Replete Haploidentical Transplantation with Post-Transplantation Cyclophosphamide for Hodgkin Lymphoma Relapsed after Autologous Transplantation: Reduced Incidence of Relapse and of Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease Compared with HLA-Identical Related Donors. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2018;24(3):627–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sureda A, Arranz R, Iriondo A, Carreras E, Lahuerta JJ, Garcia-Conde J, et al. Autologous stem-cell transplantation for Hodgkin’s disease: results and prognostic factors in 494 patients from the Grupo Espanol de Linfomas/Transplante Autologo de Medula Osea Spanish Cooperative Group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2001;19(5):1395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Satwani P, Ahn KW, Carreras J, Abdel-Azim H, Cairo MS, Cashen A, et al. A prognostic model predicting autologous transplantation outcomes in children, adolescents and young adults with Hodgkin lymphoma. Bone marrow transplantation. 2015;50(11):1416–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomson KJ, Peggs KS, Smith P, Cavet J, Hunter A, Parker A, et al. Superiority of reduced-intensity allogeneic transplantation over conventional treatment for relapse of Hodgkin’s lymphoma following autologous stem cell transplantation. Bone marrow transplantation. 2008;41(9):765–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corradini P, Sarina B, Farina L. Allogeneic transplantation for Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2011;152(3):261–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmed S, Kanakry JA, Ahn KW, Litovich C, Abdel-Azim H, Aljurf M, et al. Lower Graft-versus-Host Disease and Relapse Risk in Post-Transplant Cyclophosphamide-Based Haploidentical versus Matched Sibling Donor Reduced-Intensity Conditioning Transplant for Hodgkin Lymphoma. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2019;25(9):1859–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanate AS, Mussetti A, Kharfan-Dabaja MA, Ahn KW, DiGilio A, Beitinjaneh A, et al. Reduced-intensity transplantation for lymphomas using haploidentical related donors vs HLA-matched unrelated donors. Blood. 2016;127(7):938–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Badar TEN, Szabo A, Borson S, Vaughn J, George G, et al. . Trends in post-relapse survial in classical Hodgkin lymphoma patients after experiencing therapy failure following autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation. . Blood Adv (in press). 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gajewski JL, Phillips GL, Sobocinski KA, Armitage JO, Gale RP, Champlin RE, et al. Bone marrow transplants from HLA-identical siblings in advanced Hodgkin’s disease. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1996;14(2):572–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milpied N, Fielding AK, Pearce RM, Ernst P, Goldstone AH. Allogeneic bone marrow transplant is not better than autologous transplant for patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s disease. European Group for Blood and Bone Marrow Transplantation. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1996;14(4):1291–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez C, Gayoso J, Canals C, Finel H, Peggs K, Dominietto A, et al. Post-Transplantation Cyclophosphamide-Based Haploidentical Transplantation as Alternative to Matched Sibling or Unrelated Donor Transplantation for Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Registry Study of the Lymphoma Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(30):3425–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Genadieva-Stavrik S, Boumendil A, Dreger P, Peggs K, Briones J, Corradini P, et al. Myeloablative versus reduced intensity allogeneic stem cell transplantation for relapsed/refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma in recent years: a retrospective analysis of the Lymphoma Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(12):2251–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sureda A, Robinson S, Canals C, Carella AM, Boogaerts MA, Caballero D, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning compared with conventional allogeneic stem-cell transplantation in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma: an analysis from the Lymphoma Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(3):455–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah NN, Ahn KW, Litovich C, Fenske TS, Ahmed S, Battiwalla M, et al. Outcomes of Medicare-age eligible NHL patients receiving RIC allogeneic transplantation: a CIBMTR analysis. Blood Adv. 2018;2(8):933–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kharfan-Dabaja MA, El-Jurdi N, Ayala E, Kanate AS, Savani BN, Hamadani M. Is myeloablative dose intensity necessary in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for lymphomas? Bone marrow transplantation. 2017;52(11):1487–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fenske TS, Hamadani M, Cohen JB, Costa LJ, Kahl BS, Evens AM, et al. Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation as Curative Therapy for Patients with Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: Increasingly Successful Application to Older Patients. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2016;22(9):1543–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong S, Le-Rademacher J, Artz A, McCarthy PL, Logan BR, Pasquini MC. Comparison of non-myeloablative conditioning regimens for lymphoproliferative disorders. Bone marrow transplantation. 2015;50(3):367–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kekre N, Marquez-Malaver FJ, Cabrero M, Pinana J, Esquirol A, Soiffer RJ, et al. Fludarabine/Busulfan versus Fludarabine/Melphalan Conditioning in Patients Undergoing Reduced-Intensity Conditioning Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Lymphoma. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2016;22(10):1808–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epperla N, Ahn KW, Ahmed S, Jagasia M, DiGilio A, Devine SM, et al. Rituximab-containing reduced-intensity conditioning improves progression-free survival following allogeneic transplantation in B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10(1):117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kyriakou C, Boumendil A, Finel H, Nn Norbert S, Andersen NS, Blaise D, et al. The Impact of Advanced Patient Age on Mortality after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Retrospective Study by the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Lymphoma Working Party. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2019;25(1):86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bacigalupo A, Ballen K, Rizzo D, Giralt S, Lazarus H, Ho V, et al. Defining the intensity of conditioning regimens: working definitions. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2009;15(12):1628–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, Gascoyne RD, Specht L, Horning SJ, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(5):579–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, Klingemann HG, Beatty P, Hows J, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone marrow transplantation. 1995;15(6):825–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shulman HM, Sullivan KM, Weiden PL, McDonald GB, Striker GE, Sale GE, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host syndrome in man. A long-term clinicopathologic study of 20 Seattle patients. Am J Med. 1980;69(2):204–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Commenges D, Andersen PK. Score test of homogeneity for survival data. Lifetime Data Anal. 1995;1(2):145–56; discussion 57–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson SP, Sureda A, Canals C, Russell N, Caballero D, Bacigalupo A, et al. Reduced intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation for Hodgkin’s lymphoma: identification of prognostic factors predicting outcome. Haematologica. 2009;94(2):230–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devetten MP, Hari PN, Carreras J, Logan BR, van Besien K, Bredeson CN, et al. Unrelated donor reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2009;15(1):109–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alvarez I, Sureda A, Caballero MD, Urbano-Ispizua A, Ribera JM, Canales M, et al. Nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation is an effective therapy for refractory or relapsed hodgkin lymphoma: results of a spanish prospective cooperative protocol. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2006;12(2):172–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peggs KS, Hunter A, Chopra R, Parker A, Mahendra P, Milligan D, et al. Clinical evidence of a graft-versus-Hodgkin’s-lymphoma effect after reduced-intensity allogeneic transplantation. Lancet. 2005;365(9475):1934–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hahn T, Sucheston-Campbell LE, Preus L, Zhu X, Hansen JA, Martin PJ, et al. Establishment of Definitions and Review Process for Consistent Adjudication of Cause-specific Mortality after Allogeneic Unrelated-donor Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2015;21(9):1679–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merryman RW, Armand P, Wright KT, Rodig SJ. Checkpoint blockade in Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2017;1(26):2643–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haverkos BM, Abbott D, Hamadani M, Armand P, Flowers ME, Merryman R, et al. PD-1 blockade for relapsed lymphoma post-allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant: high response rate but frequent GVHD. Blood. 2017;130(2):221–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merryman RW, Kim HT, Zinzani PL, Carlo-Stella C, Ansell SM, Perales MA, et al. Safety and efficacy of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant after PD-1 blockade in relapsed/refractory lymphoma. Blood. 2017;129(10):1380–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Jong CN, Meijer E, Bakunina K, Nur E, van Marwijk Kooij M, de Groot MR, et al. Post-Transplantation Cyclophosphamide after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: Results of the Prospective Randomized HOVON-96 Trial in Recipients of Matched Related and Unrelated Donors. Blood. 2019;134(Supplement_1):1.31273001 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghosh N, Karmali R, Rocha V, Ahn KW, DiGilio A, Hari PN, et al. Reduced-Intensity Transplantation for Lymphomas Using Haploidentical Related Donors Versus HLA-Matched Sibling Donors: A Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research Analysis. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34(26):3141–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dreger P, Sureda A, Ahn KW, Eapen M, Litovich C, Finel H, et al. PTCy-based haploidentical vs matched related or unrelated donor reduced-intensity conditioning transplant for DLBCL. Blood Adv. 2019;3(3):360–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanate AS, Kumar A, Dreger P, Dreyling M, Le Gouill S, Corradini P, et al. Maintenance Therapies for Hodgkin and Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas After Autologous Transplantation: A Consensus Project of ASBMT, CIBMTR, and the Lymphoma Working Party of EBMT. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(5):715–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.