Abstract

Background

Cervical and uterine cancers are common in women. Diagnosis and treatment of these cancers can lead to significant issues with body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning. A comprehensive review can improve understanding of these three concepts, in turn enhancing identification and management.

Objectives

To 1) present the qualitative, descriptive, and correlational research literature surrounding body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning in women with uterine and cervical cancer; 2) identify gaps in the literature; and 3) explore the implications of the findings for future research.

Methods

A comprehensive search of the literature was undertaken by searching PubMed, CINAHL, and PsychInfo using predetermined subject headings, keywords, and exploded topics. After a comprehensive evaluation using specific criteria, 121 articles were reviewed.

Results

Qualitative studies provided information about women’s issues with body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning, while quantitative studies focused primarily on sexual functioning. The literature lacks correlational studies examining body image and sexuality. Significant issues regarding communication and quality of life were noted, and few studies were based on clear conceptual models.

Conclusion

The state of the science gleaned from this review reveals that while much is known about sexual functioning, little is known about body image and sexuality.

Implications for Practice

Further work is warranted to develop conceptual models and research on body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning as a foundation for interventions to improve quality of life.

Background

Gynecologic cancers, or cancers of women’s reproductive systems, account for over 100,000 in incidence and 32,000 in mortality annually and have a major impact on quality of life including body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning.1 These cancers include five major types based on specific disease site: uterine, cervical, ovarian, vaginal, and vulvar.2 Each type of gynecologic cancer has subtypes and unique features that affect women’s treatment, prognosis, and quality of life.

Uterine cancer is a broad term that encompasses any cancer of, or related to, the uterine body (corpus). Subtypes include endometrial cancer (cancer of the lining of the uterus) and uterine sarcomas (cancer of the uterine muscle, the myometrium).3 Uterine cancer is the fourth most common cancer of women, with over 61,000 women diagnosed annually and 12,000 dying from it.4,5 Although the incidence of uterine cancer is higher in white women, mortality is higher in African American women.4 Uterine cancer is typically diagnosed in postmenopausal women with an average age of about 604, but obese women who have exogenous estrogen production can develop endometrial cancer at an earlier age.6

Cervical cancer is cancer of the cervix uteri or the lower part of the uterus and is considered a separate disease site for a variety of reasons, including histopathology, natural history, and various treatments only applicable to this anatomic site. The cervix is composed of two different types of epithelial cells which can become malignant following exposure to the human papilloma virus infection: glandular cells, which are close to the uterus, and squamous cells, which are on the external cervix.7 Annually, almost 13,000 women are diagnosed with invasive cervical cancer in the United States, and over 4,000 die from it.8 Although the incidence of cervical cancer has decreased in the United States by 50% over the past forty years due to widespread use of cancer screening8, a significant proportion of women are still affected, and experience a variety of disease- and treatment-related issues.

Despite some unique elements when compared to other gynecologic cancers, the treatment of both early stage cervical and uterine cancers is similar, typically consisting of surgical procedures with or without postoperative radiation therapy.9,10 These treatment regimens therefore have significant and potentially similar impact on sexual health including body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning. For these reasons, cervical and uterine cancers are the focus of this review.

Treatment for uterine or cervical cancer can impact patients’ sex life and ability to have children 9.The issue of sexuality in women facing cancer, including the importance of providing information on sex, sexuality, and appearance, has been addressed by foundations such as the American Cancer Society.11 Many studies have been conducted to explore alterations in body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning experienced by women during or after treatment of cervical and uterine cancers (Table). In a detailed review, Abbott-Anderson and Kwekkeboom observed that women experienced sexual issues in three realms – physical, psychological, and social.12

Table:

Article Review Table

| Authors (Year) | Country of Origin | Design | Cancer Site | CI: SF | CI: S | CI: BI | DFW | Outcomes of Major Concepts | Instruments Used for CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abitbol + Davenport (1974) | US | Mixed Methods: Interview + Correlational | Cervical | SF | No | XRT only had ↓ SF than those who had SX only. Correlation between vaginal changes + SF | Specific questions asked by authors | ||

| Adelusi (1980) | Nigeria | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical | SF | No | SF worse after XRT than before, Stage 3 had worse SF, most no sexual activity, dyspareunia + irregular bleeding noted | Patient self-report of frequency of intercourse | ||

| Aerts et al (2015) | Belgium | Quantitative: Descriptive | Endometrial (to BG, HG) |

SF | No | 1 yr after SX EG had more dyspareunia than BG an HG. Prior to SX EG had worse SF, no difference noted in pre to post SX sexual activity | Short Sexual Functioning Scale; Specific Sexual Problems Questionnaire | ||

| Aerts et al (2014) | Belgium | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical (to BG, HG) | SF | No | Before SX CG had more dyspareunia. More CG had ↓ sexual arousal, ↑ dyspareunia than HG for 2 yrs post SX. | Short Sexual Functioning Scale; Specific Sexual Problems Questionnaire | ||

| Afiyanti + Milanti (2013) | Indonesia | Qualitative: Phenomenological | Cervical | SF | No | Women described physical changes related to SF + how reduced sexual desire + its impact on partner | - | ||

| Andersen et al (1986) | US | Mixed Methods: Interview + Descriptive | Cervical + Endometrial (to HG, BG) | SF | No | Differences between CA +HG on sexual activity Excitement different MANOVA- desire, excitement, orgasm + resolution different. Differences in DSM III criteria for SDys. | Sexual Activities Scale, patient self-report and evaluator ratings | ||

| Ashing-Giwa et al (2004) | US | Qualitative: Focus Group | Cervical | SF | S* | BI | No | Femininity + BI: AA + Cau women felt worn out, damaged Asian + Lat concerned about fertility + appearance. Asian libido + pain, Lat lack sexual desire. Cau difficulty sexual intimacy | - |

| Bae + Park (2016) | Korea | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical | SF | No | All women were high risk of SDys, ↓ age correlated with ↑ SF., SF different based on MS, ED, employment, primary caregiver. SF sig correlated Dep + QOL | FSFI | ||

| Bakker et al (2017) | Holland | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical | SF | S* | BI | No | 77% were sex active. Those not sex active r/t: ↑ sex distress, pain, worry, BI. Sex Active pts differed vaginal sex symp by tx. EBRT/IVB + RH/EBRT/IVB differ from RH. Uni: sex distress correlated w/ vaginal/sex symp, sex pain, worry, anxiety, dep, relationship satisfaction MV: sex distress correlated w/ sex pain, worry, vaginal/sex symp, BI. In controlling for BI and relationship dissatisfaction, vaginal/sex symp partially mediated by sex pain and worry | EORTC QLQ-CX24: sexual/vaginal functioning scale, sexual worry scale, and body image subscale |

| Bal et al (2013) | Turkey | Qualitative: Grounded Theory | Cervical, Endometrial + Ovarian | SF | S* | BI | No | BI: incomplete woman, abnormal appearance, Femininity: loss of womb, menopausal symp, not feeling like wife/mother, SF: ↓ desire, ↓ lubrication, pain + abstaining from intercourse, Reproduction: most not a sig issue | - |

| Barnaś et al (2012) | Poland | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical | SF* | BI | No | ↓ BI found b/w hospital + 3 mos post, no differences be/w hospital + 6 mos, or 3 to 6 mos, ↓ in BI + sexual worries in QOL scale but not statistically sig | EORTC QLQ CX24: Sexual Functioning, Sexual Activity, Sexual Enjoyment and Body Image Scales | |

| Becker et al (2011) | Germany | Quantitative: Descriptive | Endometrial | SF | No | No statistically sig differences in SF b/w those who had SX + those who had SX + VBT | - | ||

| Bergmark et al (1999) | Sweden | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical (to HG) | SF | S | No | ↓ interest same b/w groups, CG ↓ libido, ↓ lubrication, which created ↑ distress. CG more ↓ vaginal length, ↑ dyspareunia, ↑ vaginal bleeding. SX ↑ risk of ↓ lubrication, ↓ length, ↓ vaginal elasticity. VBT +/or EBRT r/t ↓ lubrication, ↓ genital swelling, ↓ length, ↓ elasticity. Distress noted with infertility, loss of womb r/t sexuality | 136 item questionarie on sexual function developed based on in depth interviews, and pilot studies | |

| Bergmark et al (2002) | Sweden | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical | SF | No | SX: overall SDys caused most distress, ↓ orgasm, ↓ orgasmic delight also caused distress; SX +VBT: distress r/t ↓ orgasm, ↓ intercourse, vaginal changes, SX + EBRT: distress r/t dyspareunia, SDys; XRT: distress r/t dyspareunia. irrespective of group: most distress r/t dyspareunia, ↓ orgasm | 136 item questionnaire on sexual function developed based on in depth interviews and pilot studies | ||

| Bergmark et al (2005) | Sweden | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical (to HG, abuse history of both groups) | SF | No | Sexual symptoms worse in abused, than non-abused women. Risk of SDys ↑ by 7.9 for abused non-cancer, 12.1 cancer, no abuse, + 30 cancer + abuse. Abused women had ↑ distress with alteration in fertility | 136 item questionnaire on sexual function developed based on in depth interviews, and pilot studies | ||

| Bertelsen (1983) | Denmark | Mixed Methods: interviews + pelvic exam Descriptive |

Cervical | SF | No | ↑ SDys in XRT than SX + XRT. Dyspareunia ↑ in XRT, No normal vaginal mucosa in XRT. ↑mucosa damage r/t ↑SDys. Fibrosis ↑ with XRT. ↓ sexual desire noted in all patients (XRT, SX, SX + XRT) | Specific Questions asked by authors | ||

| Berza et al (2013) | Lativa | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical | SF | No | SX pts had normal FSH. Most XRT had abnormal FSH. ↑ FSH correlated with XRT. XRT pts had sig change in SF after treatment | Sexual Quality of Life Questionnaire | ||

| Bilodeau + Bouchard (2011) | Canada | Qualitative: Phenomenology | Cervical | S | No | 3 Themes: 1) living in global change in one’s life 2) see conjugal relationship different 3) sexuality in a different way a) search of love b) living in sexual body traumatized by XRT | - | ||

| Bogani et al (2014) | Italy | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical | SF | No | ↓ SF scores in NS-LRH + LRH. In Uni Analysis: ↑ co-morbidities, ↑ stage, + LRH, ↓ SF. In MV Analysis: no factor associated to SF, but trends to LRH and ↑ co-morbidities | FSFI | ||

| Brotto et al (2013) | Canada | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical | SF | No | Sexual distress ↑ in both from baseline to 1 mos. RH distress ↑1 to 6 mos. RT group distress ↓. # of sexually active women ↓ sig 1 mo after surgery. | Female Sexual Distress Scale | ||

| Brown et al (1972) | US | Mixed Methods: interviews + descriptive | Cervical + Vulvar | SF* | S* | No | Pts seemed to retain basic feminine interests. Most human figure drawings lacked sexual features. 1 reported phantom sensations of intercourse. Most had no sexual interest. Some had autoerotic activity of ostomy or scar tissue for sex pleasure. | Human Figure Drawings, Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory | |

| Bukovic et al (2003) | Croatia | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical | SF | BI | No | Sex life ↓ in both SX+XRT. XRT pts had ↓ lubrication. Most feared dyspareunia. 1/3 of both had change in BI. Most wanted sexual counseling | Prepared by authors for this study | |

| Burns et al (2007) | England | Qualitative: Phenomenological | Cervical | S* | BI* | No | 3 Themes: 1) physical effects after treatment 2) impact of treatment + adverse effect on S (bowel + bladder impacted S, ↓ interest in sex, ↓ BI) 3) inadequate information about treatment + effects (↓ info on side effects + sexuality) | - | |

| Butler-Manuel (1999) | England | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical | SF | No | >½ thought sex life ↓ after treatment. A few did not engage in sex. 1/3 felt loss of fertility affected life. | Questionnaire developed by authors | ||

| Cain et al (1983) | US | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical + Uterine (to HG + depressed) | SF* | S* | No | Pts with stage 3 had ↓ sexual relationship than other groups. ½ cancer pts said sex relationship differed after treatment + abstained from sex. | Psychosocial Adjustment Scale (had a few questions on SF and S) | |

| Carta et al (2014) | Italy | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical + uterine (to HG) | SF (authors stated S) | No | Sex desire ↑ from 6 to 24 mos in CA. Arousal freq + satisfaction had no change over time. Lubrication ↑ in control, ↓ in CA over 2 yr period. Control reached orgasm more freq + faster. Pain ↑ in CA with no change over time, but ↓ in control. | FSFI | ||

| Carter et al (2012) | US | Quantitative: Correlational | Endometrial | SF* | S* | BI* | No | SF ↓ after SX bu recovered to pre-op by 6 mos. Fear of sex ↑ from pre-op to 6 mos. More laparoscopic said physical appearance was of ↑ importance than laparotomy. Laparoscopic ↑ satisfaction with appearance, + feeling like a woman. | Functional Assessment Cancer Therapy -General (FACT_G) (contains items on SF, S, BI) |

| Carter et al (2010) | US | Mixed Methods: Questionnaires, Open-Ended Questions Descriptive | Cervical | SF | S | No | RT were more concerned on fertility as why they chose RT over RH. All women scored in SDys range throughout 2 years after Sx. RT had concerns r/t conceive but they declined with time. At end of study 8 babies were born from RT group. | FACT-G and cervix subscale, FSFI | |

| Carter et al (2008) | US | Mixed Methods; Questionnaires, exploratory questions Descriptive | Cervical (RT patients) | SF | S* | No | Over 2/3 pts had vaginal scarring + stenosis, over half of these had to have a dilation procedure. Most women had fear of sex, 2/3 were not sexually active before surgery. Some had pain after surgery but it ↓ over 12 mos. Fear of sex ↓ w/ dyspareunia ↓. Women discussed both bleeding issues + sexuality issues, bleeding issues were listed in charts, sexuality was not. | FACT-G and cervix subscale, FSFI | |

| Carter et al (2010) | US | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical + Uterine | SF | S* | No | Many pts had distress related to fertility. About half were satisfied with sex life, but over 2/3 had SDys. Age 30–34, intact ovaries had ↑ SF. High school ed, non-Hispanic ↑ distress,↑ dep ↑ meno symp. Higher Ed, Hispanic, white race, ↑ ovarian function had ↓ meno symp | FSFI, Menopausal Symptom Checklist (contains SF, S items) | |

| Chan et al (2015) | US | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical + Ovarian (two groups those with FSS + those who did not) | SF | No | Retaining uterus not associated with sex satisfaction. No difference in sexual QOL based on different types of FSS | World Health Organization Quality of Life (BREF) and Satisfaction with Life Scale (both included items on SF) | ||

| Chen et al (2014) | China | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical (compared NS-LRH to LRH) | SF | No | NS-LRH pts had better sex desire, arousal, vaginal lubrication, orgasm + sex satisfaction. | FSFI | ||

| Chen et al (2015) | China | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical (LRH to LRH+PV, to HG) | SF | No | LRH+PV had longer vaginal length than LRH. Both groups had ↓ SF to HG. LRH+PV had ↑ satisfaction, lubrication, pain. Both sx groups were same in desire, orgasm, arousal. All pts felt they gained sex life at 1 yr post-op. | FSFI | ||

| Cleary et al (2011) | Ireland | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical, Ovarian, Endometrial, + Vulvar | S* | BI | Yes, developed by authors. 3 core aspects of S | Sexual Self-Concept: relatively positive, pts – responses on BI. Most women felt BI + sexual attractiveness changed after tx. Sexual Relationships: change noted after tx. SF: poor overall SF in pts after tx. 1/3 to 1/2 of women had a change in each area of S. Age r/t BI + Sexual Self-concept, EC had ↑ sexual esteem than CG. No associations between other variables tested. | Body Image Scale, Sexual Esteem Scale, Sexual Experiences Scale, Intimate Relationships Scale | |

| Clemmens et al (2008) | US | Qualitative: Semi-Structured Interviews |

Cervical | SF | No | SF issues fell into 3 of 4 themes discovered. The three applicable themes: Moving On, Renewed Appreciation, Ongoing Struggles | - | ||

| Corney et al (1993) | England | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical + Vulvar | SF | S* | No | Over 1/3 had ↓ sex relationship, 1/3 of married women↑ in marriage. Many women would like more information on SF issues. | Likert questions regarding SF and S developed by authors | |

| Corney et al (1992) | England | Mixed Methods: Descriptive + interviews | Cervical + Vulvar | SF* | BI | No | 1/3 felt ↓ in attractiveness post tx. Freq of intercourse ↓ in sexually active pts. ¾ had sex problem in 1st yr, 2/3 still had problem. About ½ had distress r/t to it. ½ felt ↓ sex relationship. Inability to bear children caused distress in some. | Questions developed by authors | |

| Correa et al (2016) | Brazil | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical (to HG) | SF | No | ↑ menopause r/t to tx, bleeding with intercourse in CG. ↓ SF in CG. Desire was lowest, + satisfaction highest SF domains. In LR, cancer interference with sex life, vaginal stenosis/shortening, ↑ urination, fecal incontinence, intestinal bleeding, tenesmus, lower lymphedema, were adverse tx effects on SF. | FSFI | ||

| Cull et al (1993) | England | Mixed Methods: Correlational + semi-structured interviews | Cervical | SF | S* | No | ¼ pts had worries regarding self-confidence, ↓ attractiveness, sex causing pain, ↓ sexually attractive. ½ ↓ in SF. XRT had worse SF. Sexual difficulties r/t physical symptom checklist, distress scores. Most women wanted more information about sexual issues r/t tx. | Sexual Relationship and Worries about Cervical Cancer (created and pilot tested by authors) | |

| Daga et al (2017) | India | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical | SF | No | SDys found in all pts. Avg score 11.84. All domains show SDys and were very low indicating severe issues | FSFI | ||

| Dahbi et al (2018) | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical (compared to HG, BG) | SF (authors stated S) | No | Vaginal length sig b/w groups. SF not sig different b/w groups. Sig difference in length w/o sex after treatment. | FSFI | |||

| Damast et al (2014) | US | Quantitative: Correlational | Endometrial (compared IVB after SX, to SX) | SF | No | 4/5 pts had SDys. A correlation b/w SDys + vaginal symp was found. On Multi IVB not associated with SDys. Mutli showed some associations, but after adjusting no sig correlation. | FSFI | ||

| Damast et al 2012). | US | Quantitative: Correlational | Endometrial (to HG) | SF | No | 4/5 had SDys. Highest to lowest domains: arousal, orgasm, desire, dryness, pain. EG ↓ than HG. Uni: SF associated with hysterectomy type, lubricant use. MV hysterectomy type + lubrication associated with SF. Laparotomy + no lubricant use associated with ↓ SF. | FSFI | ||

| Davidson et al (2003) | England | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical (XRT vs. SX+XRT) | SF | No | Prior to XRT: relationship b/w age + vaginal scale. SDys ↓ for SX prior to XRT. Post-XRT: some pts had no change after on vaginal/SDys. Those followed at all time points showed ↓ vaginal dys but not SDys. | Late Effects of Normal Tissue Subjective Objective Management Analytic (LENT SOMA) scales for vagina and sexual dysfunction | ||

| De Boer et al (2015) | Holland | Quantitative: Descriptive | Endometrial (EBRT vs. VBT) | SF | No | 1/5 reported sex activity, 3/10 had sex interest. More than 4/5 of EBRT found sex enjoyable compared to ½ VBT. Dryness, shortening, pain not different b/w groups. | EORTC QLQ – C30 | ||

| De Groot et al (2005) | Canada | Quantitative: Descriptive |

Cervical (+ male partner) | S* | No | Women had more intrusiveness in relationship + intimacy than partner. Sexuality was the second concern of the couples. The concerns were higher if tx was <12 mos | Cancer Concerns Questionnaire | ||

| De Groot et al (2007) | Canada | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical, Endometrial + Ovarian (single vs. partnered) | S | No | Partnered women were more concerned about S + partner relationships, than single women. | Cancer Concerns Questionnaire | ||

| Ditto et al (2009) | Italy | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical (NS hysterectomy vs. non-nerve sparing) | SF | No | No differences noted in sexual functioning between groups. | FACT- (cervix) CX | ||

| Donovan et al (2007) | US | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical + some CIN (to HG) | SF* | S* | BI* | Yes, tested a multi-dimensional model of sexual health in this study | Uni:: ↑ lack of sex interest ↑ SDys ↓ sex satisfaction in CG. Vaginal symp associated sex interest, SDys, sex satisfaction. Recent dx or ↓ ed associated with ↓ sex interest, HRT associated with ↑ interest. ↓ appearance ↓ partner relations associated ↓ sex interest. XRT r/t ↑ SDys. In final model XRT 7%, vaginal changes 26%, appearance 8%, self-schema 5% of variability is SDys. Time since Dx 14%, vaginal changes 28%, partner relations 7% of variability in sex satisfaction. | Sexual Function and Vaginal Changes Questionnaire, Dyadic Adjustment Scale, Body-Self Relations Questionnaire, Sexual Self-Schema Scale for Women |

| Fernandes + Kimura (2010) | Brazil | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical | SF | No | ½ pts were not or only a little interested in sex. About 1/3 did not or only a little felt sexually attractive, about 1/3 afraid to have sex, 1/5 felt vagina was to narrow. Sex activity, importance of sex activity were found as predictors of HRQOL. | FACT-CX | ||

| Filiberti et al (1991) | Italy | Qualitative: interviews | Gynecologic no specific diagnoses (to BG) | S | No | 2 themes: 1) how perceive illness + psychologic effects 2) sexual significance of hysterectomy. in CG 1/3 referred to loss of uterus as damage to S, 2/3 were not satisfied with S, 3 had painful sex life. These views were different than BG. | - | ||

| Flay + Matthews (1995) | New Zealand | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical (pre + post XRT) | SF | No | Freq intercourse, sex satisfaction returned to baseline after tx. 2/5 always/usually reached climax. 1/3 uninterested in sex. 1/3 overall dissatisfaction sex life. Moderate relationship satisfaction, Reasons for changes in SF: ½ bleeding, ¼ dyspareunia, ¼ pelvic pain, ¼ dryness. Over time vaginal shortening + dryness increased. | Short Sexual Functioning Scale, Specific Sexual Problems Questionnaire | ||

| Friedman et al (2011) | US | Quantitative: Descriptive | Endometrial | SF | No | Pts compliant with dilator usage were more worried about sex. 1/5 said they were a little unhappy with relationship after XRT. Those sexually active 2/3 rarely reached orgasm, 1/3 were only occasionally able to complete intercourse. ¼ vaginal shortening, ½ vaginal dryness, ¼ pain. | Sexual and Vaginal Changes Questionnaire | ||

| Froeding et al (2014) | Denmark | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical (RT, RH + healthy controls) | SF | No | RT, RH had low sex interest in 1st yr compared to HG. RH post-meno had ↓ desire than pre-meno. RT more concerned about pain + sex problems. Correlation b/w worry + vaginal symp, Both CG had dyspareunia + shortening, dissatisfied with sex life, | FSFI | ||

| Frumovitz et al 2005) | US | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical (Sx vs. XRT) | SF | No | XRT pts ↑ vaginal dryness + meno symp. No difference in sex desire in groups. XRT had ↓ arousal, lubrication, sex satisfaction. No difference in BG or HG. Married r/t ↑ SF. XRT r/t ↓ SF. | FSFI | ||

| Gao et al (2017) | China | Quantitative: Correlational | Endometrial | SF | S* | No | 69% pts had SDys, 56% did not resume intercourse post tx. Avg of those who resumed: 10 mos. Uni: age, XRT, consultation associated with SDys. MV: XRT, Age, time since sx, consultation associated w/ SDys | FSFI, FACT-G (some S questions) | |

| Gotay et al (2008) | US | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical | S* | BI* | No | Age r/t sex adjust, optimism/pessimism scale r/t femininity + BI. Social ties r/t to BI, Femininity + sex adjust. Fear of intimacy correlated to femininity, BI. Affection correlated w/ femininity + BI. Almost ½: disease impacted relationship. < ½ sex enjoyable | Medical Outcomes Short Form (SF-36) (some items on, S), Fear of Intimacy Scale, Sexual Adjustment Questionnaire | |

| Greenwald + McCorkle (2008) | US | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical (long term survivors) | SF | S | No | 4/5 sex active; 3/5 felt sex important, 4/5 desired sex, 9/10 enjoyed sex. Stage 1dx + Cau predicted S + SF outcomes. Stage 1 ↓ harm to relationship. Hysterectomy ↑ harm to relationship. ↑ interest in sex ↑ desire. BSO ↓ enjoyment. | Sexual Adjustment Scale, SF-36 | |

| Greimel et al (2009) | Austria | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical (long term survivors Sx + XRT, XRT, Sx + Chemo vs Sx) | SF | No | Sx+XRT had ↑ feelings of tight vagina. In sex active, no difference noted on pleasure in intercourse. Sx+XRT ↓ freq of intercourse, which was different than other groups. | EORTC-CX, Sexual Activity Questionnaire | ||

| Grion et al (2016) | Brazil | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical | SF | No | Main issues during intercourse: 1) bleeding 2) ↓ pleasure 3) dyspareunia 4) vaginal dryness. SDys was found in many pts. ↓ SF r/t Sx prior to XRT (this correlated w/ arousal + satisfaction) vaginal bleeding r/t orgasm, satisfaction. Sx r/t to ↑ pain + neg associated with pleasure, orgasm. Smoking pos associated with FSFI. | FSFI | ||

| Grumann et al (2001) | Australia | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical | SF | No | 3/20 CG had sex impairment to 3/5 BG at pre-op. 8 mos post op CG ↑ vaginal dryness than pre-op + BG. ↓ CG used HRT. Pre-op CG ↑ intercourse than BG, HG. SF in CG neither ↓ or ↑ from pre-op to 8 mos post op, but ↓ from pre-4 mos post + 4 to 8 mos post in all except petting, masturbation. | Derogatis Sexual Functioning Inventory | ||

| Guntupalli et al (2017) | US | Quantitative: Correlational | Uterine, Cervical, Ovarian | SF | S* | No | 39% sex active had SDys, 42% were <50. Of sex active pts ↓ SF, ↓pleasure, ↓sex (all types), ↓ freq. SDys associated w/ age, ovarian or cervical CA, chemo, in committed relationship. SDys post-tx did not ↑ marital dys | FSFI, Intimate Bond Measure Form | |

| Harding et al (2014) | Japan | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical (Sx vs HRT + HG) | SF | No | Median XRT SF 5.5, Sx 18.9, HG 22.1. XRT > SDys than HG. Pain only difference b/w Sx + XRT. Median scores on arousal, lubrication, orgasm, pain in XRT = 0 indicating pain prevented intercourse | FSFI | ||

| Hawighorst-Knapstein et al (2004) | Germany | Mixed Methods: interviews + descriptive | Cervical | SF* | BI | No | Adjuvant therapy pts had ↑ issues sex QOL. Sex issues ↓ Werthiems than PE pts. Sex issue ↑ problem post-op. 1 yr post-op sex problems ↑ + r/t to treatment. XRT ↑ sex issues. Pre to post-op all felt < attractive. Adjuvant < attractive. BI ↓ 2 or more ostomies | Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System instrument, Body image (Strauss and Appelt) | |

| Hazewinkel et al (2012) | Holland | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical (XRT vs RH) | BI | No | XRT ↓ BI disturbance. ↑ BI disturbance MV associated w/ severe defecation. | Body Image Scale | ||

| Hofsjo et al (2017) | Sweden | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical to HG | SF | S* | No | CCA ↑ vaginal symp (↓ lubrication, ↓ genital swelling, ↓ vaginal length, ↓ elasticity) No difference on dyspareunia. Lubricants ↑ use in CA. HG ↑ sexual attractiveness. CA ↓ orgasms. Neg correlation w/ ↓ vaginal length, epithelial variables, and number of papillae. | Questionnaire developed by Bergmark et al in 1999 article (see above) | |

| Hollie (2012) | US | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical | SF | S* | Roy’s adaptation model; sexual adaptation model | ↓ sex drive most common in all pts. Vaginal dryness most in RH + XRT. Cognitive coping sig pos. correlated sex esteem, sex satisfaction. Neg association b/w health status and sex self-concept. In separate regressions, cognitive coping predicted 38% variance in sex esteem, and 43% in sex satisfaction | Multidimensional Sexual Self Concept Scale | |

| Holt et al (2015) | Denmark | Quantitative: Descriptive | Endometrial, Cervical, Ovarian | S | BI | No | 6.3% women’s goal setting was to improve BI or S. Sex issues goals common at time 1 in cervical. | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| Hsu et al (2009) | Taiwan | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical (Sx vs XRT) | SF* | No | Vaginal dryness and dyspariâ more common in Sx. Factor analysis on sexual (23.8%) pelvic neural (13.65) symptoms, which were higher in Sx. | EORTC QLQ-C30 | ||

| Hunter (2011) | US | Qualitative: Interviews | Cervical (pts and partners) | SF | S* | No | Variety of issues including vaginal changes, infertility, frustration with current or pasts relationship, sex/physical change. Pts thought changes would improve, but worsened. Not enough information or questioning on issues r/t to treatment by providers | - | |

| Jenkins (1988) | US | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical, Endometrial | SF | No | Pre-tx: most desired/engaged in intercourse 1 more times a wk. >4/5 found enjoyable. Post-tx: 6–12 mos intercourse ↓ 2 a mo; desire ↓ 1 a mo. All indicators of SF ↓ post-tx. >2/3 sex active had dyspareunia (r/t vaginal dryness, short vagina). 12/15 pts rated sex adjust poor/fair. 3/5 received no information on body/long term effects XRT | Questionnaire adapted from previous used questionnaires | ||

| Jensen et al (2004) | Denmark | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical (to HG) | SF | No | CG tx w/ RH had ↓ sex interest, lubrication 2 yrs post sx. Post-op – 3mos CG ↑ dyspareunia Post-op- 6 mos: ↑ severe orgasm issues 5 wks post-op: dissatisfaction w/ sex, ↓ appearance; sex active CG met HG at 6 mos. 1/3 had ↓ interest, lubrication, vagina size prior to cancer. 18 mos: ↓ sex interest to HG | Sexual Function Vaginal Changes Questionnaire | ||

| Jensen et al (2003) | Denmark | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical, Vaginal | SF | No | SDys lasted 2 yrs. ↓ sex interest, lubrication, statisfaction. To HG, CA ↑ dyspareunia 0–2 yrs post XRT. Vaginal problems r/t to intercourse lasted 2 yrs. ↑ vaginal irritation + discharge 1 yr post tx. 6–24 mos: ½ ↑ distress from ↓ lubrication. Pre-Post: post had ↓ sex interest, ↑ risk of dyspareunia, ↑ difficulty w/ orgasm, ↓ finish intercourse. 3/5 were sex active post tx, ↓ freq. HRT ↓ risk of loss of interest | Sexual Function Vaginal Changes Questionnaire | ||

| Jongpipan + Charoenkwan (2007) | Thailand | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical | SF | No | All pts sex active pre-op, 2/3 sex active 3 mos post-op. All but 2 at 6 mos. No differences in pre-op SF or 3 mos or 6 mos post op | Questionnaire developed by authors | ||

| Juraskova et al (2012) | Australia | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical, Endometrial | SF | No | ↓ SF, quality of sex life found over yr 1. Quantity of sex ↓ but then ↑ over baseline by 1 yr. Time since tx and age sig with SF. Time, XRT, quantity, quality of sex life predicted SF. SF sig predictor of QOL. | Derogatis Sexual Functioning Inventory | ||

| Juraskova et al (2013) | Australia | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical, Endometrial (to pre-invasive and BG) | SF | No | No sig difference in unadjusted group means b/w groups. Sex drive covaried with age, sex satisfaction covaried w/ global sexual satisfaction. ↑ CA had ↑ vaginal stenosis to BG. No difference in lubrication. Few CA had change in genital sensation | Derogatis Sexual Functioning Inventory | ||

| Juraskova et al (2003) | Australia | Qualitative: Phenomenological based on grounded theory | Cervical, Uterine | SF | S | Proposed model in discussion on sexual outcomes | Pts who had XRT had ↑ difficulties with sex activity and satisfaction. Dyspareunia + ↓ lubrication common in XRT. SX resumed Sex activity, only ½ XRT. 2 themes and subthemes: 1) patient-partner issues (femininity, reproductive organs, sexuality, intimacy issues, resuming sex activity) 2) patient-doctor issues (long term side effects of tx) | - | |

| Kirchheiner et al (2016) | International | Quantitative: Descriptive |

Cervical | SF | BI | No | Symp occurred right after treatment and remained ↑ meno symp, SF, vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, sex worries BI similar to reference range. Sex activity ↑ over time. | -C30 and CX-24 | |

| Korfage et al (2009) | Holland | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical | SF | BI | No | BI, sex worry worse in 2–5 yr survivors. After correcting age/stage: XRT worse SF sex worry, meno symp. Primary XRT worse than adjuvant XRT. Chemo+XRT ↓ BI, sex worry. | ||

| Kritcharoen et al (2005) | Thailand | Mixed Methods: Descriptive, Interviews | Cervical (and partners) | SF | No | After tx: less women decided about number of children, avoided intercourse. Partners avoided intercourse after treatment, but it was important part of marriage. Pts intercourse ↑anxiety, dyspareunia. ¼ no orgasms, 1/5 no sex fulfillment post-tx | EORTC QLQ CX-24 | ||

| Krumm + Lamberti (1993) | US | Mixed Methods: Descriptive, Interviews | Cervical | SF | S* | No | 1/5 did not resume sex activity, Median time was 20 days, range 1–730 to resume sex activity. ½ sex activity change r/t XRT. 1/5 sex lives indirect XRT r/t fatigue. Some offered and used dilators, 1/5 had providers discussed sex activity. Concerns about sex attractiveness, ↓ femininity. | Frequency and Likert questions asked by the authors | |

| Kullmer et al (1999) | Germany | Quantitative: Descriptive | Gyn + breast; (disease free to recurrence to HG) | BI | No | Both no disease + recurrence had ↓ BI to HG. No disease ↑ BI than recurrence | German Instrument: Frankfurter Korperkonzeptskalen | ||

| Kylstra et al (1999) | Holland | Quantitative: Descriptive | Gyn (to HG) | SF | No | In CA sex satisfaction, freq masturbation, nor sex fantasy change over time, 9 wks to resume intercourse. Only sig difference pre-tx CA to HG was sex activity. Only sig change over time was lubrication and premature orgasm (HG exceeded CA on premature orgasm at 12 mos) Pts wanted to discuss sex issues w/ provider | Questionnaire for Screening of Sexual Dysfunctions Short Form | ||

| Lalos et al (2009) | Sweden | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical | SF | No | Not all responded to dyspareunia question but sig ↑ pre-to post tx noted. Sig ↑ in HRT use pre-to post. 4/5 had active sex life at 1 yr, but ↓ desire. 1/10 had vaginal atrophy at 1 yr. | Questionnaire developed and validated by authors | ||

| Lalos + Lalos (1996) | Sweden | Mixed Methods: Descriptive, Interviews | Cervical, Endometrial (to HG) | SF | No | Vaginal dryness freq in CA groups after tx. 2/3 EG, 9.5/10 CG felt tx severely impacted sex life. Most common reasons: urine incontinence, ↓ lubrication, ↓ desire. | Questionnaire developed by authors | ||

| Lamb + Shelton (1994) | US | Qualitative Interviews | Endometrial | SF | BI | Adaptation model of BI, SF, sexual self-esteem + self-concept | 6 categories emerged: 1) intimate relationship before CA 2)effects of symptoms of diagnosis + CA (alterations in BI, SF remediated through tx, change in bleeding change in BI) 3) Ramification of tx (renewed threat to BI) 4) Partner Influence 5) sexual adaptation 6) enhancing adaptation | - | |

| Levin et al (2010) | US | Quantitative: Correlational | Endometrial, Ovarian, Cervical, Vulvar | SF | No | Sex morbidity sig predictor depression, body change stress, psych QOL. Sex Morbidity covaried with ↑ depressive symptoms, ↑ body change stress, ↓ psych QOL | FSFI, and items from Derogatis Sexual Functioning Index, and disease subscales from FACT | ||

| Lindau et al (2007) | US | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical, Vaginal (to national average) | SF | No | Satisfaction w/ sex correlated with global health and QOL. CA physical symp interfered with sex. ↑ dyspareunia, ↓ lubrication was ↑ CA. 2/3 unattractive r/t urine infections incontinence. CA more likely to exhibit complex sex morbidity (3 or more domains) | Questionnaire designed using 1992 National Health and Social Life Survey and questions from the FSFI | ||

| Lloyd et al (2014) | England | Qualitative: Phenomenological | Cervical | S* | No | Sx linked to pos (retained fertility) and neg (isolation, delayed reaction) physical symp, menstrual changes, post-coital bleeding. Sx: impacts on sex intimacy, 1/6 short vagina. Pre to post: BI, femininity same (hidden procedure), ability to conceive (body in working order)Fertility and births were discussed | - | ||

| Matthews et al (1999) | US | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical, Vaginal | SF | No | 1/3 short vagina, ¼ vaginal stenosis, < ¼ pelvic adhesions, ½ dyspareunia at some poiont, > ½ insufficient lubrication + fear intercourse at some point. 1/3–1/2 reported current SF problems. Pts with SF issues found less likely to use coping strategies. | 5 items written by authors | ||

| McCorkle et al (2006) | US | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical | SF* | S* | QOL framework | Severe pain + change in marital status predictors of depressive symp. | Likert Scale 1–10 for Sexual symptoms; items related to marital status and changes from authors | |

| Mikkelsen et al (2017) | Denmark | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical | SF | BI | No | <45 sig ↑ meno symp, ↓ BI, ↑ sex activity, ↑ sex worries. MV: differences pronounced, sex worries sig. Meno symp ↓ w/ time since dx. MV: correlation ↑ BMI and ↓ BI. ↑ age had ↓ meno symp, ↓ sex worry, ↑ sex/vaginal function. 66% had severe problems (1 or more sex, incontinence or BI) | EORTC QLQ-C30 and CX-24 module | |

| Noronha et al (2013) | Brazil | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical | SF | No | ↓ dyspareunia rate in RH than XRT or Chemo +XRT. No difference in pleasant feelings w/ intercourse, orgasm, excitement, passion or satisfaction. No difference in pre-to post Tx SF Vagina length shorter in XRT and Chemo+XRT | Personal Experiences Questionnaire | ||

| Nout et al (2009) | Holland | Quantitative: Descriptive | Endometrial | SF | No | Sex activity lowest at baseline, only 15% sex active. ↑ interest and activity in 1st 6 mos post but plateaued. | EORTC QLQ-C30 and ovarian and prostate modules to help with SF questions | ||

| Onujiogu et al (2011) | US | Quantitative: Correlational | Endometrial | SF | No | 9/10 had SDys. Pain was worst scale. FACT-En correlated with SF. ↑grade, XRT, no sex partner, relationship status, heart disease mental health diabetes, current dilator use associated with SF score. After MV: grade relationship status, mental health, and blood sugar correlated with SF. | FSFI | ||

| Park et al (2007) | Korea | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical | SF | BI | No | CG ↑ symp; ↓ BI, ↓ SF, ↓ vaginal function, ↑ sex worry, ↑ anxiety on sex performance. XRT: ↑ dyspareunia Sx+XRT: ↑ risk for “sexuality items”. Chemo associated with ↑ dyspareunia, ↑ anxiety on sex performance, ↓ lubrication in MV. | EORTC QLQ-C30 and CX-24 module, additional sexual function items posed from another survey | |

| Pieterse et al (2013) | Holland | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical (NS-LRH to LRH) | SF | No | Sig ↓ at 12–24 mos for all in sex activity, narrow/short vagina, dyspareunia, lubrication, no content with sex life. Sex activity ↑ after 12 + 24 mos. Interest, freq of sex, orgasm, no different. XRT ↑ short vagina. 24 mos XRT ↓ sex activity than Sx. Sex activity at 2 mos r/t age, + pre-treatment levels | Dutch Gynaecologic Leiden Questionnaire | ||

| Pieterse et al (2006) | Holland | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical (Sx to Sx+ XRT to HG) | SF | No | At 24 mos ↑pts had little/no lubrication, Baseline-24 mos: pts had ↑ pain, short+ dry vagina, no sensation around labia, dissatisfaction with sex relationship. Sex activity ↑2 yrs post-sx. ↑% post-meno ↓ sex active, ↓ interest sex. 2 yrs post tx: ↑pts had narrow/short vagina. CG had ↑pain, ↓ sex prior to tx through 2 yrs. To HG, CG at 3 mos ↑ dissatisfaction w/ sex, ↑ dry vagina, ↓ sensation. XRT had ↓ sex activity. | Dutch Gynaecologic Leiden Questionnaire | ||

| Plotti et al (2012) | Italy | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical (modified RH to classic RH) | SF | BI* | No | SF + BI worse for classic than modified. No differences for meno symp, sex worry. Classic worse sex activity and enjoyment. | EORTC QLQ-CX24 | |

| Plotti et al (2011) | Italy | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical (Sx+ Chemo to HG, BG) | SF* | BI* | No | CG had ↓ BI, SF, Vaginal function than BG + HG. Sex enjoyment + meno symp ↓ CG + BG, than HG. | EORTC QLQ-CX24 | |

| Quick et al (2012) | US | Quantitative: Descriptive | Endometrial (Sx to Sx+IVB) | SF | No | No sig differences in sex activity, dry vagina, size of vagina, or pain with intercourse. ½ Sx+IVB to 1/3 Sx ↓ interest in sex. | EORTC QLQ-C30 and CX 24 | ||

| Rodrigues et al (2012) | Portugal | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical, Uterine, Rectal (to HG) | SF (authors stated S) | No | Sig difference in vaginal discharge b/w HG and CA. SF sig ↓ in CA in total and all domains except satisfaction. XRT only ↓ SF total and all domains to other tx. Pts >40 ↑arousal, lubrication and total SF. Associations noted n/w dep +desire, dep + lubrication, dep + orgasm, dep + pain. | FSFI | ||

| Rowlands et al (2014) | Australia | Quantitative: Correlational | Endometrial | SF | No | Pts ↑ sex wellbeing 3–5yrs post diagnosis, were likely older, high school ed, ↓ sx of dep at diagnosis, no history of gyn illness, stage1, Sx w/o XRT, ↓ symp anxiety or dep, ↓ BI issues. MV: pts older, ↓ ed levels, ↓ symp dep at diagnosis, no gyn conditions, Sx w/o XRT had ↑ sex wellbeing. Association b/w mental health at diagnosis was sig after adjust for psychosocial and SF. | Sexual Function Vaginal Changes Questionnaire | ||

| Saewong + Choobun (2005) | Thailand | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical | SF* | No | Sex activity parameters ↓ except deep dyspareunia. Most pts had ability to reach orgasm. Most pts: dyspareunia ↑ (most superficial pain), freq of intercourse and enjoyment ↓. Stage associated w/ ↓ freq sex. | Frequency counts and visual scales for ratings of sexual function | ||

| Schover et al (1989) | US | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical | SF | No | Sex desire + Sex activity stayed at initial levels at 6 mos but ↓ sig 1 yr.1 yr: XRT ↓ desire than RH. Orgasm different b/w groups. No difference on lubrication or excitement. Arousal problems ↑ 1 yr. Difference in ↑ pain of XRT to RH at 1 yr. All pts with severe dyspareunia, post-coital bleeding, pain on penetration were XRT. RH ↑ normal vagina exams than XRT. | Sex History Form | ||

| Schultz et al (1991) | Holland | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical (to BG, HG) | SF | No | Prior to tx CG differed from HG on arousal, orgasm, sex dissatisfaction. Sex response ↓ in CG w/ neg genital sensations in arousal and orgasm. At 1 yr: vagina sensitivity ↑ in CG, sig different from HG. Yr 2 ↑ CG on neg genital sensation during arousal and vaginal sensitivity partially recovered. | Intimate Body Contact Scale, General Satisfaction with Sexual Interaction Scale | ||

| Segal et al (2017) | US | Quantitative: Correlational | Uterine | SF | No | Of sex active pts 34% dyspareunia, 19% emotional reactions during sex. 8% restriction of sex r/t leakage of urine/stool. Age, BMI, + XRT independent predictors of SF after controlling for meno. | Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual questionnaire | ||

| Seibaek + Petersen (2007) | Denmark | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical | BI* | No | Post tx 48% body slightly changed, 14% considerably changed. | SF-36 | ||

| Serati et al (2009) | Italy | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical (LP to LS to HG) | SF | No | SF scale results similar for LP + LS, but worse than HG. LP had better SF in arousal, lubrication and orgasm than LS. | FSFI | ||

| Song et al (2012) | Korea | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical (CC, RH, RT) | SF | No | CC had no SDys, RH and RT did. SF ↓ in RT and RH to CC. All domains ↓ for RH, RT to CC. RH had ↓ pain than RT. CC ↓ SF issue prior to tx than RH, RT. | FSFI | ||

| Sung et al (2017) | Korea | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical to HG | SF | BI | No | Long term CCA survivors had ↑ SDys, vaginal Dys, + ↓ BI. ↑ sex worry to control. Sex enjoyment and sex activity similar to HG | EORTC QLQ-C30 and CX 24 | |

| Tangjitgamol et al (2007) | Thailand | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical | SF | No | Many resumed sex activity. Mean time 4–4.5 mos. Pre to Post SF: ½ ↓ in freq, desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm. Satisfaction maintained in ½. Dyspareunia ↑ 1/3. During questionnaires: women asked about other issues including improving SF, sexuality. | Questionnaire developed by authors | ||

| Tian (2013) | China | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical | SF | No | Majority not satisfied with sex life. Women not wanting sex life stated: vaginal bleeding, short vagina, stenosis, dryness, dyspareunia. After adjusting for age, survival time. Sexual wellbeing explained 61.8% variations in QOL. Libido had ↑ effect on QOL than sex satisfaction. Libido and sex satisfaction effect woman’s social family wellbeing. Sexual satisfaction affects emotional functioning wellbeing. Risk factors not wanting sex life: vaginal symp, dissatisfaction with BI, age. | Two questions from authors and items from EORTC QLQ CX24 | ||

| Tsai et al (2011) | Taiwan | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical | SF | No | Age, ed, job, religion, menstrual status correlated w/ SDys. Stage 2, counseling r/t ↑ SDys. MV: age, ed, stage, sex counseling associated w/ SDys. AOR of SDys ↑16% w/ 1 yr in age. SDys ↑ w/ ↓ ed, stage 2 or ↑. | Chinese version of FSFI | ||

| Vaisy (2014) | Iran | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical (to HG) | SF* | No | 36.7% CG to 23.4% HG had sex intercourse more than 3 times a week. | Persian Version of Sexual Function Scale | ||

| Van de Wiel et al (1988) | Holland | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical (to HG) | SF | S* | No | All had sex contact with partners at 6 mos post-tx. Tx ↑ discontent with sex life. Self-esteem as sex partner different b/w CG + HG. CG ↓ view of themselves as sex partner. | Intimate Body Contact Scale | |

| Vermeer et al (2015) | Holland | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical | SF* | S* | Theory of planned behavior | ½ needed information or help for sexual concerns. Help seeking sig neg correlations w/ age and relationship duration. Pos correlations to help seeking: importance SF, social support, professional psychosexual support Women w partner who had SDys less likely to seek up. | Female Sexual Distress Scale, Likert items on intimacy and partner relations | |

| Vermeer et al (2016) | Holland | Qualitative: Interviews | Cervical | SF | S | No | Themes: 1) experiences with respect to SDys (subthemes: sexuality, SF + distress, relationship functioning) 2) experiences with information and care provision 3) healthcare needs and attitudes towards modes of intervention delivery (subtheme: needs, barriers, attitudes) | - | |

| Vistad et al (2008) | Norway | Quantitative: Descriptive | Cervical | SF | No | 58% vaginal dryness, 42% pain with intercourse. Compared to controls: CG ↓ sex active. | LENT SOMA Scales, Sexual Activity Questionnaire | ||

| Wenzel et al (2005) | US | Quantitative: Correlational | Cervical (to HG) | SF | S* | No | Important predictors of distress included reproductive concerns. ¼ CG were not sexually active. CG ↑sex discomfort, hot flashes, vaginal dryness pain. Reproductive concerns associated w/ ↓ QOL. | Gynecologic Problems Checklist, Likert items on reproductive concerns | |

| Zeng et al (2011) | China | Qualitative: Open ended questions | Cervical | SF* | S* | BI* | QOL model by Ferrell | Subthemes of 2nd theme included: physical changes (including loss of hair, premature menopause), social wellbeing (social isolation, change in role) spiritual wellbeing (appreciating relationships with others), disruptions to sex life (reduced freq, vaginal dryness, dyspareunia) | - |

Abbreviations:

examined only facets of the concept; ↓, decreased; ↑, increased; +, and; AA, African American; Avg, average; b/w, between; BG, benign group; BI, Body Image; CA, cancer group; Cau, Caucasian; CG; Cervical Cancer Group; CI, Concept(s) of Interest; Dep, Depression; DFW, Described Framework; Dys, dysfunction; Ed, education; EG, Endometrial Cancer Group; EORTC QLQ, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire; Freq, frequency; FSS, fertility sparing surgery; HG, healthy group; HRQOL, health related quality of life; Lat, Latina; LP, laparotomy; LRH, laparoscopic radical hysterectomy; LRH+PV, laparoscopic radical hysterectomy and peritoneal vaginoplasty; LS, laparoscopy; Meno Symp, menopausal symptoms; Mos, months; MS, marital status; MV, multivariate; Neg, negative; NS-LRH, nerve sparing laparoscopic radical hysterectomy; pts, patients; Pos, positive; QOL, quality of life; r/t, related to; RH, radical hysterectomy; RT, radical trachelectomy; S, Sexuality; SDys, Sexual Dysfunction; SF, sexual functioning; SX, surgery; Symp, symptoms; Uni, univariate; VBT, vaginal brachytherapy; w/, with; XRT, Radiation Therapy; yr(s), year(s).

According to these authors, physical issues included changes in orgasms, urinary and bowel incontinence, menopausal symptoms, and decreased sexual activity. Common psychological issues included poor body image, decreased sense of femininity, anxiety about sexual interactions, and pain. Consequently, related social issues may emerge, for example, the ability to maintain a sexual relationship, communication difficulties, and adverse effects on future intimate relationships.12 These authors specifically concluded that women with gynecologic cancer have significant issues related to body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning as a result of their disease and/or its treatment.

While these issues are of great importance to women and are addressed by relevant health care-related organizations, oncology nurses also must recognize the importance of body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning in women with cervical and uterine malignancies, even with the lack of evidenced-based practice guidelines. Nurses value holistic care, including the fact that recognition and management of issues during diagnosis, treatment, and beyond is important. Better knowledge and understanding of the issues of body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning can help prepare clinicians and researchers for recognizing the importance of these issues, engaging women in discussion, and working collaboratively to improve outcomes.

The purpose of this integrative review was to explore the extent to which the nursing and interdisciplinary scientific literature described the concepts of body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning in women with gynecologic cancer with a focus on cervical and uterine cancer. The major objectives of the review were to: 1) present the nursing and interdisciplinary qualitative, descriptive, and correlational research literature surrounding body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning in women with uterine and cervical cancer; 2) identify the gaps in the literature; and 3) explore the implications of findings for future research.

Definition of Concepts

In order to guide the search for articles that included body image, sexuality, and sexual function, the first author identified explicit definitions of these concepts including their various facets. Body image was defined through a concept development approach conducted by the first author and colleagues as a multifaceted concept comprised of an emotional and behavioral response to one’s perceived appearance, sexuality, and femininity (Authors, unpublished data, 2019). In this definition, the way in which a woman views her body may depend on stigma, reproduction, or sociocultural identities, but not on the perceptions of others. Sexuality was defined using Wilmoth and Spinelli’s perspective that sexuality included not only a woman’s ability to engage in sexual intercourse, but also the facets of femininity, reproductive ability, appearance, and sexual functioning capacity.13 These authors noted that sexuality was part of a woman’s personality and included emotional, intellectual, and sociocultural components13, thus women with gynecologic cancer describe sexuality as encompassing how they feel about themselves, how they present themselves to others, and their intimate partner relations, reproduction, and femininity.14,15 Sexual functioning was defined as encompassing the ability to engage in sexual activity, intercourse, or stimulation, as well as the facets of desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and whether or not intercourse caused pain or discomfort.16 The definitions used for the purposes of this manuscript are expansive and inclusive to capture all relevant information on the concepts.

Methods

This review was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).17 The first author conducted a systematic search of the literature in three databases: PubMed, CINAHL, and PsychInfo. In each database, she searched MESH or subject headings and the terms keyword 1 (body image), keyword 2 (sexuality), and keyword 3 (sexual functioning and sexual dysfunction) in conjunction with keyword 4 (uterine cancer, uterus cancer, and/or a uterine neoplasm), and keyword 5 (cervical cancer, cervical neoplasm, and/or uterine cervical cancer). In addition, she searched Medline using the key words of body representation and body schema since these terms are related to body image. In databases in which it was possible, keywords, MESH, or subject headings were exploded. When title and abstract searches were available, they were used for all articles that included one of the keywords, MESH headings, or terms under the MESH headings. Articles were included in the review if they were written in the English language; included invasive cervical and/or uterine cancer; mentioned body image, sexuality, or sexual functioning; and reported qualitative, quantitative descriptive, or correlational research. Articles that reported instrumentation and experimental research were excluded as the science in these areas is emergent with few existing publications to date. Mixed methods studies containing any combination of qualitative, quantitative, or other methods were also included. Additionally, articles describing gynecologic cancer without further identifying sub-types of cervical or uterine cancer were included in the review if they were initially found in the search, as they were likely to be related to the population of women with uterine and cervical cancer. Articles were excluded if they were not written in English; did not mention invasive cervical or uterine cancer or any other type of cancer; reported the perceptions of individuals other than patients (e.g., family members, health care providers); or were reports of instrument or experimental studies. Non-research articles were excluded as well. Because this review sought to identify all published studies on these concepts, no year restrictions were set.

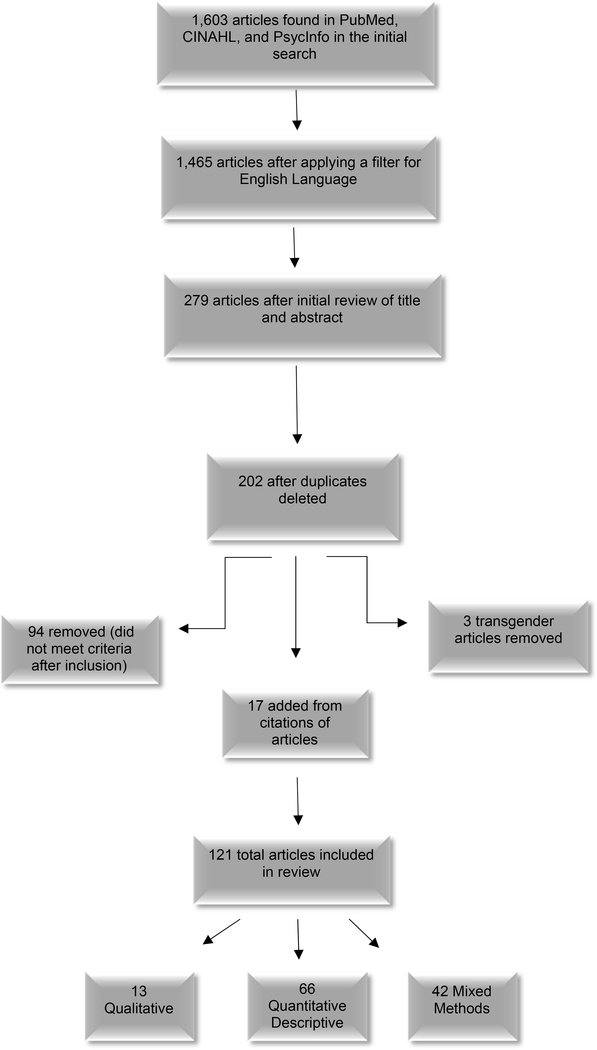

The flow diagram in the Figure depicts the search process, review of articles for inclusion and exclusion conducted by two independent reviewers (who discussed and reached agreement on any discrepancies), and the final yield for intensive examination. In brief, the initial search yielded 1,603 articles when reviewing titles and abstracts for fit with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. This number was reduced to 1,465 after the English language filter was applied, and further reduced to 279 following a careful review of titles and abstracts. After removal of duplications, 202 remained, but this number was further reduced when articles on transgendered individuals’ experiences with body image, sexuality, or sexual functioning in relation to cervical or uterine cancer were removed because while important, their issues are likely to be different and need to be reviewed in depth later. Once full copies of the remaining articles were examined, 94 more were eliminated because they did not meet the criteria. Finally, the authors added an additional 17 articles identified in the reference lists of other articles. Thus, the final sample for this integrative review was 121 articles.

Figure:

Article Search Process Diagram

These articles were entered into a table to enable extraction and categorization of study characteristics into categories that included full citation, country of origin, study design, sample, setting, use of theoretical framework, primary outcomes, and additional comments. These categories also provided the structure for a condensed, but comprehensive table that enabled completion of the review (see Table).

Quality Appraisal of Literature

The condensed table was created to evaluate and synthesize the extracted information to achieve the specific objectives of the review. The data in this table include authors and year of study, country of origin, design, cancer population, framework, and outcomes related to body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning. Although the authors identified information on other related concepts (e.g., anxiety, depression) they were beyond the scope of the review and thus not included.

The authors used PRISMA to ensure a quality appraisal of the articles included in this review, specifically the standardized checklist that helps ensure rigorous assessment of all articles. PRISMA requires reviewers to assess the risk of bias of individual studies either at study or outcome level, along with describing the summary measures used to examine bias and rigor within the studies. The authors also assessed rigor and the risk of bias by type of study. In qualitative studies, they examined documentation of trustworthiness in the report, along with credibility, transferability, dependability, confirmability. In quantitative studies, they assessed methodological rigor, bias and confounding, reliability and validity of instrumentation, and objectivity in each article. Additionally, per the PRISMA checklist, the authors assessed how the risk of bias affects the cumulative evidence. Use of the PRISMA checklist indicated that most of the studies included in this review were quite rigorous. A few studies displayed issues with methodologic rigor, or issues with reliability and/or validity of instruments used to collect data. A more detailed discussion of methodological and theoretical issues can be found in the Synthesis of Results section below.

Synthesis of Results

The results are organized below into qualitative and quantitative sections for two major reasons. First, since literature and knowledge related to these concepts are emerging, and the science remains under-developed, a knowledge-building organizational scheme is appropriate. Second, of the 121 studies reviewed, 72 focused on sexual functioning, eight on sexuality, and three on body image, but 38 studies focused on more than one of the concepts, including six that incorporated facets of all three concepts of interest. Given that nearly one-third of the studies focused on more than one of the concepts, it is impossible to organize this section by concept without extensive redundancy in presentation of studies and/or relevant discussion.

The Table shows analysis of the individual articles (n=121) which included qualitative (n=13), quantitative descriptive (n=66), and correlational or predictive studies, including mixed methods (n=42). Of these studies, only eight described conceptual frameworks used to guide the study design and interpretation of data. Although as noted above, some researchers examined more than one of the three concepts of interest (i.e., body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning), none addressed all three concepts or the multiple facets of each concept simultaneously. Sample sizes ranged from 10–30 women in the qualitative studies, and 11–898 in the quantitative studies (not accounting for attrition in longitudinal studies). The majority of studies were conducted in the United States Western Europe, and Eastern Asia.

Qualitative studies

Authors of these articles primarily described women’s experiences with body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning during treatment for uterine and cervical cancer. Although researchers mostly studied one concept of interest, including body image, sexuality, or sexual functioning or their facets, or quality of life, they collected and described a multitude of information from participants.

Body image issues were discussed by the majority of women who noted that it had changed as a result of their treatment.18–21 Some women referred to their experiences from the perspective of living in a sexual body traumatized by radiation.19 Treatment-related body image concerns were found to be different among various racial and/or ethnic groups. African American and White women described feelings of being worn out and damaged, whereas Latina women focused on changes in their appearance when treated for various stages of cervical cancer.22 In contrast, women with early stage cervical cancer did not report significant body image concerns, because their treatment did not produce external side effects and therefore these women considered them “hidden”.23

Sexuality was discussed frequently by women in these studies. With respect to relationships with their partners, women indicated frustration related to communication or intimacy with current partners, fear of new relationships, difficulty with relationships, and concerns that their spouses may have found another partner.19,20,24,25 Women’s discussions of sexuality also included facets such as role changes, feeling alone, awareness of a “body clock”, and infertility as a result of treatment.20–23,25–27 Finally, women also noted the removal of the uterus as an issue related to sexuality and the impact of urinary and bladder leakage and incontinence on sexuality.18,19,28

Sexual functioning difficulties were common throughout these studies. Multiple authors noted that sexual activity was an important part of women’s lives but that it was negatively impacted by treatment and when resumed, was often associated with anxiety.18–21,28 Juraskova and colleagues found that the subpopulation of women receiving combination radiation and chemotherapy had difficulty with sexual activity and satisfaction, citing lack of lubrication and dyspareunia as the most significant concerns arising from their treatment.29 Other changes commonly reported included premature menopause, vaginal changes, reduced frequency of sex, decreased desire, and dyspareunia.20–27,30

An additional significant concern raised by women in many of these studies was lack of communication with healthcare providers about body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning. They focused on attitudes toward their sexual healthcare needs and whether they were educated by healthcare providers about these needs. In general, women did not feel that they received adequate information, including about long-term side effects. They also identified barriers to seeking help, and reported that healthcare providers rarely asked about sexual problems or, if they did inquire, did not usually provide beneficial advice.20,25,29

Quantitative descriptive and correlational studies

Cervical and uterine cancer patients reported body image issues including feeling less attractive and having an altered essence of femininity or sexual identify.31–33 Compared to healthy women, cancer survivors in general reported worse body image34, which was a significantly distressing issue35 that women wanted to improve.36 Both patients with recurrence and those without evidence of disease reported a negative body image37,38, but those with recurrence had worse scores.37 Body image changes and feeling less attractive were noted in those who underwent a pelvic exenteration or a Wertheim’s procedure for cancer treatment.39–41 Finally, two variables—younger age42 and issues with urination and defecation43—appeared to be related to worse body image.

Changes in facets of sexuality were reported by multiple researchers, for example, sexual self-concept, femininity, intimacy, self-consciousness about one’s appearance, femininity, reproduction, feeling as if something was missing from the body, sexual attractiveness, and communication with partners regarding sexual matters.36,42,44–59 Hollie noted a negative association between health status perception and cognitive coping and sexual self-concept, in that focused cognitive coping predicted 38% of the variance in sexual esteem, and cognitive coping predicted 43% of the variance in sexual satisfaction.60 In a different study, however, age influenced sexual-self-concept in both positive and negative directions.42

Most researchers who conducted these studies examined sexual functioning including some reference to its facets of sexual activity, lubrication, sensation, desire, arousal, and orgasm. A common finding was that although women had resumed sexual activity after treatment, the treatment had a noticeable negative impact on their sexual lives.33,34,36,37,51,52,55–57,63–96,94 Many researchers compared cervical or uterine cancer survivors’ sexual functioning to that of control subjects, finding that cancer patients had worse sexual functioning with up to 90% having difficulties32,61,64,83,95–100, specifically those who had more extensive treatments including hysterectomy, trachelectomy, chemotherapy, and/or radiation, rather than conization procedures.32,63,68,76,101–104 Some researchers found a high risk of sexual dysfunction and substantial difficulties in sexual functioning in up to 90% of women compared to control groups if present across a variety of treatment modalities.34,65,70,71,75,85,86,105–109 Dyspareunia was significantly problematic for 10–85% of women in various populations, with higher rates in those who received radiation.32,39–41,47,61,64,74,75,78,79,83,87,89,95,101,102,110–116 Improved sexual functioning was found in women who underwent a peritoneal vaginoplasty or nerve-sparing surgery.69,117 Notably, sexual activity and sexual functioning decreased over time, especially in the first year after treatment.74,79,102

Factors that negatively and significantly (p <.05) correlated with sexual functioning included severity of vaginal alteration65,70,118,119, non-nerve sparing hysterectomy108,120, radiation75,86,119,121,122, classic hysterectomy71,109, increased cancer stage86,123, and diabetes.71,86 Other significant negative (p <0.05) correlates of sexual functioning included depression, worse quality of life107,124, a high number of co-morbidities, increased stage of disease108, increased urination, fecal incontinence, intestinal bleeding, tenesmus, lower limb lymphedema70, worse relationships with partners, worse perceived appearance119,125,126, worse self-schema119, lack of a sexual partner, and mental illness.86 The combination of cervical cancer and sexual abuse was found to have a significant correlation with sexual functioning, increasing the risk of sexual dysfunction by 30%.52

The major factors that were positively and significantly (p <.05) correlated with sexual functioning included lubricant use71, increased physical health75, use of counseling123, increased time since surgery71,127, and involvement in a marital relationship.75 Some studies revealed that certain variables were correlated either positively or negatively with sexual functioning depending on the study, specifically age71,107,121,123,125–129, job status, educational level, religion, and marital/relationship status.86,123,130 Sexual functioning varied both negatively and positively among studies with marital status, education, employment, and the primary caregiver.107 These disparate findings may have various explanations, but further research is needed to better understand these relationships.

Numerous authors reporting quantitative findings noted lack of knowledge about late effects of treatment and illness and communication with providers about sexual functioning, or sexuality and body image.72,87,96,97,112,116,131–133 Both patients and caregivers expressed significant concerns regarding lack of explanation about side effects immediately after treatment and into long term survivorship. Patients also expressed concerns about the lack of communication with healthcare providers, and a need for improving communication strategies.

Only two quantitative studies focused on integration of body image, sexuality, or sexual functioning.134,135 Bakker and colleagues did not propose a relationship among these concepts, but examined relationships among sexual distress and related biopsychosocial variables, which included facets of both sexuality and body image.134 Similarly, Carter and colleagues examined responses from a clinical trial that focused on sexual functioning, and described facets of the concepts of body image and sexuality in the context of quality of life.135 While these studies began addressing the gaps identified in the literature, the lack of focus on integrating body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning remains an issue for both researchers and clinicians.

Within the quantitative studies a wide array of instruments were used to study the concepts. Specific questions designed by authors85,115, Likert rating scales49,130, to validated and reliable instruments were utilized amongst the various studies. Most commonly validated instruments like the Body Image Scale, the Sexual Function Vaginal Changes Questionnaire, and the Female Sexual Function Index were utilized by authors; however, in other articles only a few questions from validated instruments (i.e. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ), Functional Assessment of Cancer Treatment General) were used to examine the concepts.121,126,135 Additionally, some authors used translated validated instruments.37,87,97,123

Theoretical and methodological concerns

An important aspect of the authors’ evaluation of the literature was whether the studies had any significant theoretical or methodological concerns. As expected, researchers rarely used conceptual models to guide their studies. Juraskova and colleagues discussed the development of a model based on their results and proposed its use for future quantitative research.29 In addition, Zeng et al. used a quality of life model to guide their qualitative interviews21, and Lamb and Shelton used a model of body image, sexual functioning, and sexual esteem for the same purpose.27 The lack of conceptual frameworks raises concerns about lack of theoretical grounding in studies of body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning. Some researchers used frameworks that did not address the concepts studied, or that did not connect specifically to their research concepts.60,136 A significant number of researchers misused the terms sexual functioning and sexuality, appearing to consider them interchangeable when in fact they have distinct conceptual definitions.50,61,64,95,137,138 Even though sexuality does encompass some facets of sexual functioning, sexual functioning does not include facets of sexuality. The misuse of these terms and their conceptual meanings spans the time period of this literature review.

In the qualitative literature, most researchers used appropriate qualitative approaches and rigorous methods to examine the concepts of sexuality and sexual functioning. However, in the quantitative studies that were reviewed, a variety of methodological concerns were noted, including retrospective designs using chart reviews, small sample sizes, substantially different comparison group sizes, lower retention rates in longitudinal designs, misuse of instruments (e.g., using validated sexual functioning instruments to measure sexuality), and skewed data. These methodologic concerns varied over both descriptive and correlational research and thus can inform and strengthen the design of future studies.52,54,58,61,64,67,95,111,139–141 Most of these findings, other than the mismeasurement of concepts, do not undermine new research, but rather can serve to enhance the conceptual foundation and methodological rigor of future research. Researchers who wish to conduct studies on body image, sexuality, sexual functioning can use the theoretical and methodological concerns as well as the substantive findings identified in this review to help inform their research questions, conceptual approaches, and methods.

Discussion

Although many of qualitative studies were unique in their examination of the concepts, some general conclusions can be drawn from the results. First, the studies addressing sexual functioning alone were conducted solely in the cervical cancer population. In contrast, insights on sexual functioning in the uterine cancer population resulted from studies that focused on body image or sexuality in addition to sexual functioning. Second, both Hunter and Vermeer and colleagues noted that patients did not feel as though they received needed or desired information on sexual health.20,25 Third, other researchers18,30 found that long term survivors had bowel problems, bladder issues, and difficulties with sexual functioning. Fourth, disturbances in body image were found by multiple researchers.18,19,22,26,27 Finally, all of the researchers who conducted qualitative analyses uncovered meaningful issues with sexual functioning (see Table). While much has been learned through reviewing this body of research, some information is missing and could be gained in further qualitative research. For example, more knowledge is needed about patients’ perspectives on communication with their clinicians about body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning, along with information on how patients manage these issues.

While there were numerous quantitative studies with a variety of individual findings, some general conclusions can also be drawn. Overall, a majority of studies focused on sexual functioning using validated instruments to measure this concept. Fewer studies focused on body image or sexuality, or their various facets. For these concepts, some studies used validated questionnaires, where others used a few questions developed by authors or from other questionnaires. Additionally, few studies examined multiple concepts or facets of multiple concepts20,34,50,51,53,55,56,58,59,64,81,92,35,94,99,100,121,125,130,133,136,36,38–42,49, and only two examined all three concepts.134,135 To begin addressing these issues, body image, sexuality and sexual functioning need to be studied together in future quantitative research studies.

In both the qualitative and quantitative literature, women noted significant changes in the concepts from cancer and its treatment, which could affect their sexual quality of life. While most researchers did not address sexual-related quality of life, they did discuss the impact of body image, sexuality, and/or sexual functioning on women’s quality of life. A few of the studies that used the EORTC QLQ and subsequent submodules (i.e., the cervix subscale) had significant findings on the impact on quality of life. Hsu and colleagues found that the sexual and pelvic neural symptoms accounted for a significant percentage on factor analysis, which indicated higher symptoms in those areas, subsequently affecting quality of life.93 While Mikkelsen and colleagues noted that certain subsets of women (i.e. younger age) had increased symptoms and therefore more impact on their quality of life.125 Additionally, Tian demonstrated that sexual wellbeing accounted for over 61% of the variation in women’s quality of life in their study.126

Conclusions and Implications

The qualitative and quantitative descriptive studies that were reviewed represented a wide array of countries (although predominantly North American and European) and provided an overview of the severity and intensity of issues related to body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning. Although the qualitative literature provided a wealth of information on all three concepts, the quantitative literature was more focused on sexual functioning.

While the majority of articles were North American and Western Europe, information varied on differences among women in various countries or of different races and ethnic backgrounds with respect to body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning. Most women from various countries expressed similar experiences with sexual functioning, including painful or difficult intercourse and related dryness. However, significant differences were noted in body image and sexuality. Women in more developed countries discussed issues with body image even though the procedures were focused on internal organs, and issues with femininity19,30,42,78,134, whereas those in less developed countries focused more on intimacy and role concerns within the family.26,48 Additionally, one qualitative study focused on changes in the concepts by race and ethnicity within the United States, and found significant differences in views on body image and sexuality after diagnosis and treatment.22

Another noteworthy finding was that while a multitude of issues with body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning were reported by women, few studies examined information provided on these issues, or communication with providers about these issues. Among the few studies that did examine information or communication, results demonstrated disparities in type and quantity of information provided, and the extent and topics of communication with providers on these issues.20,49,142 Other researchers noted that patients wanted to have these conversations with their providers, but did not bring them up. 82