Abstract

Recently, the role of mitochondrial activity in high-energy demand organs and in the orchestration of whole-body metabolism has received renewed attention. In mitochondria, pyruvate oxidation, ensured by efficient mitochondrial pyruvate entry and matrix dehydrogenases activity, generates acetyl CoA that enters the TCA cycle. TCA cycle activity, in turn, provides reducing equivalents and electrons that feed the electron transport chain eventually producing ATP. Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake plays an essential role in the control of aerobic metabolism. Mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation stimulates aerobic metabolism by inducing the activity of three TCA cycle dehydrogenases. In detail, matrix Ca2+ indirectly modulates pyruvate dehydrogenase via pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase 1, and directly activates isocitrate and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenases. Here, we will discuss the contribution of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake to the metabolic homeostasis of organs involved in systemic metabolism, including liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue. We will also tackle the role of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in the heart, a high-energy consuming organ whose function strictly depends on appropriate Ca2+ signaling.

Keywords: mitochondria, aerobic metabolism, mitochondrial calcium uptake, mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU), systemic metabolism

Introduction

Intracellular Ca2+ plays a significant role as a second messenger controlling both ubiquitous and tissue-specific processes. The decoy of different triggers and the well-defined spatio-temporal patterns of the Ca2+ response to different stimuli warrant the specificity of the cellular response (Berridge, 2001).

The outward translocation of protons across the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM), determined by the activity of the electron transport chain (ETC), generates a mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψ) that is negative inside. Ca2+ influx into energized mitochondria depends on the electrochemical gradient (Deluca and Engstrom, 1961; Vasington and Murphy, 1962) and it is ensured by the activity of the Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter (MCU), a highly selective channel of the IMM (Kirichok et al., 2004; Baughman et al., 2011; De Stefani et al., 2011). Microdomains of high Ca2+ concentration in sites of close proximity between the ER/SR and the mitochondria, the so-called mitochondrial-associated membranes (MAMs), are generated upon Ca2+ release from the ER/SR (endoplasmic/sarcoplasmic reticulum) stores, ensuring rapid mitochondrial Ca2+ entry (Rizzuto et al., 1993, 1998).

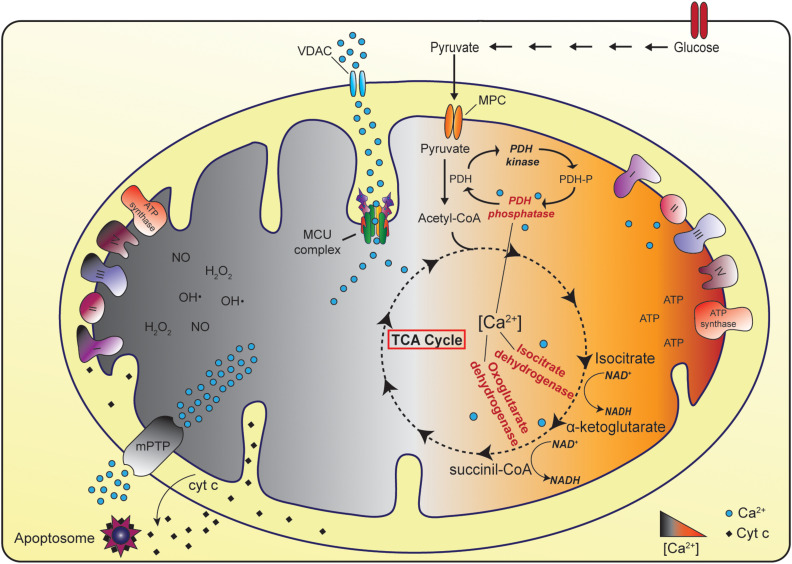

In physiological condition, mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ regulates the activity of TCA cycle dehydrogenases, thus triggering the generation of reducing equivalents that feed the ETC and eventually ATP production. On the contrary, in pathological settings, mitochondrial Ca2+ overload causes the opening of the Permeability Transition Pore (PTP) that results in the rapid collapse of the Δψ and in mitochondrial swelling, together with the release of cytochrome c and pro-apoptotic factors (Figure 1) (Briston et al., 2017; Giorgio et al., 2018).

FIGURE 1.

The physiopathological role of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. In physiological conditions, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake stimulates ATP production thanks to the positive regulation of three Ca2+-dependent TCA cycle enzymes (pyruvate dehydrogenase, isocitrate dehydrogenase, and oxoglutarate dehydrogenase). In the cytoplasm glycolytic reactions convert glucose to pyruvate. The Mitochondrial Pyruvate Carrier (MPC) determines the entry of pyruvate into mitochondria, where pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) oxidizes pyruvate to acetyl-CoA. Acetyl-CoA enters the TCA cycle leading to the generation of reducing equivalents that feed the electron transport chain and eventually ATP production. Conversely, in pathological settings, mitochondrial Ca2+ overload could cause the opening of the mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore (mPTP) eventually leading to cell death.

In this review, we will discuss the role of mitochondrial Ca2+ signaling in the control of cell metabolism, with particular emphasis on those organs involved in the regulation of systemic metabolism, including liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue. We will also review the role of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in the control of heart function, an organ in which this aspect has been widely investigated. We will particularly discuss studies based on the genetic modulation of MCU activity, both in cell lines and in animal models.

The Molecular Identity and Regulation of the MCU Complex

The Pore Forming Subunits

To date, three different mitochondrial membrane proteins have been characterized as components of the Ca2+ uniporter, i.e., MCU, MCUb, and essential MCU regulator (EMRE).

Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter

All eukaryotes, except for yeasts, display a well-conserved MCU gene (originally known as CCDC109a), which encodes a 40 kDa protein composed of two coiled-coil domains and two transmembrane domains, the latter separated by a short but highly conserved loop facing the intermembrane space (IMS). This loop is enriched in acidic residues, essential to confer Ca2+ selectivity. MCU was predicted to oligomerize in order to form a functional channel, and this hypothesis was supported by gel separation of native mitochondrial proteins, that highlighted an MCU-containing complex with an apparent molecular weight of 450 kDa (Baughman et al., 2011; De Stefani et al., 2011). Although MCU was predicted to form tetramers by a molecular dynamic approach (Raffaello et al., 2013), the first proposed structure of the Caenorhabditis elegans MCU by NMR and cryo-EM techniques envisaged a pentameric assembly (Oxenoid et al., 2016). However, more recently, cryo-EM and/or X-ray structures have been reported for fungal MCU, either alone (Baradaran et al., 2018; Fan et al., 2018; Nguyen et al., 2018; Yoo et al., 2018), or in the presence of EMRE (Wang et al., 2019). These studies demonstrated that fungal MCU complexes are characterized by tetrameric architectures. The tetrameric assembly is conserved also in zebrafish MCU that, by sharing more than 90% homology with human MCU, provides a strong evidence in favor of this architecture in higher eukaryotes (Baradaran et al., 2018).

Mitochondrial calcium uniporter silencing leads to abrogation of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, while its overexpression triggers both a significant increase of mitochondrial Ca2+ transients in intact cells, and an increase in the Ca2+ current in mitoplasts (De Stefani et al., 2011; Chaudhuri et al., 2013). Recombinant MCU is sufficient to form a Ca2+-selective channel in a planar lipid bilayer per se (De Stefani et al., 2011), with a similar current, although not identical, to the one recorded in patch-clamp experiments of isolated mitoplasts (Kirichok et al., 2004). The overall activity of the MCU complex is highly variable among tissues (Fieni et al., 2012). This feature likely integrates different factors: the volume occupied by mitochondria in a specific cell type (Fieni et al., 2012), the relative expression levels of MCU compared to other complex components and/or regulators, including MCUb (Raffaello et al., 2013) and MICU1 (Paillard et al., 2017) and, possibly, the extent of the contact sites between mitochondria and the ER/SR.

MCUb

MCUb gene (CCDC109b) is conserved in most vertebrates although it is absent in some organisms in which MCU is present (e.g., plants, Nematoda and Arthropoda). MCUb protein, with a molecular weight of 40 kDa, shares 50% sequence homology with MCU and it is similarly organized: it has two coiled-coil domains and two transmembrane domains separated by a loop. A crucial amino acid substitution (E256V) in the loop region neutralizing a negative charge is responsible for the drastic reduction in channel conductivity compared to the MCU (Raffaello et al., 2013). MCUb overexpression decreases mitochondrial Ca2+ transients upon agonist stimulation in cells and, when inserted into a planar lipid bilayer, no current is recorded. On the contrary, MCUb silencing triggers a significant increase in mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (Raffaello et al., 2013). This is due to the fact that MCUb forms hetero-oligomers with MCU, negatively affecting the Ca2+ permeation through the channel.

Regarding the physiological relevance of MCUb, it should be noted that MCU/MCUb ratio varies greatly among different tissues. For instance, it is higher in the skeletal muscle compared to the heart (Raffaello et al., 2013), in agreement with the different activity of the MCU in different tissues (Fieni et al., 2012).

EMRE

EMRE is a 10 kDa protein located in the IMM composed of a transmembrane domain, a short N-terminal domain, and a highly conserved C-terminus enriched in acidic residues (Sancak et al., 2013). Although in a planar lipid bilayer MCU per se is sufficient to generate current, experiments performed in EMRE knockout cells demonstrate that this small protein is essential for MCU activity. In cells, EMRE was suggested to modulate the interaction between the pore region and the regulatory subunits of the channel (Sancak et al., 2013). However, in a planar lipid bilayer, MCU and its regulatory subunits MICU1 and MICU2 exhibit the capacity to interact with each other without the presence of EMRE (Patron et al., 2014). Nonetheless, the heterologous reconstitution of human MCU in yeast requires EMRE, indicating that EMRE is needed to assemble a functional channel in metazoan (Kovács-Bogdán et al., 2014). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that EMRE C-terminus faces the mitochondrial matrix and forms a Ca2+-dependent complex with MICU1 and MICU2. Thus, EMRE would act as a sensor for [Ca2+] on both sides of the IMM (Vais et al., 2016). However, a different EMRE topology across the IMM has been alternatively suggested, not compatible with the role of EMRE C-terminus as a matrix-Ca2+ sensor (Yamamoto et al., 2016). Recently, to determine the relevance of EMRE in vivo, an EMRE–/– mouse model was generated (Liu et al., 2020). Studies in these mice demonstrated that EMRE is indeed required for MCU activity, as EMRE–/– isolated mitochondria did not accumulate Ca2+. EMRE deletion results in almost complete embryonic lethality in inbred C57Bl6/N mice. However, EMRE–/– animals are viable in a mixed background, although they are smaller and born with less frequency. No differences were detected in terms of basal metabolic functions in the hybrid Bl6/N-CD1 EMRE–/– animals compared to controls. Indeed, neither the total body oxygen consumption nor the body carbon dioxide generation were affected by EMRE deletion. EMRE–/– mice showed normal skeletal muscle function in terms of muscle force and running capacity. In addition, knockout animals displayed regular cardiac function including no changes in IR (ischemia-reperfusion) injury. Thus, similarly to the MCU–/– mouse model generated in a mixed background (Pan et al., 2013; Murphy et al., 2014), adaptations occur to sustain mitochondrial activity in the absence of a functional MCU channel. Finally, Liu et al. (2016) showed that in the absence of MICU1 expression, deletion of one allele of EMRE reduced the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, suggesting that efforts to modulate the MCU complex could be beneficial for the diseases characterized by Ca2+ overload.

The Regulatory Subunits

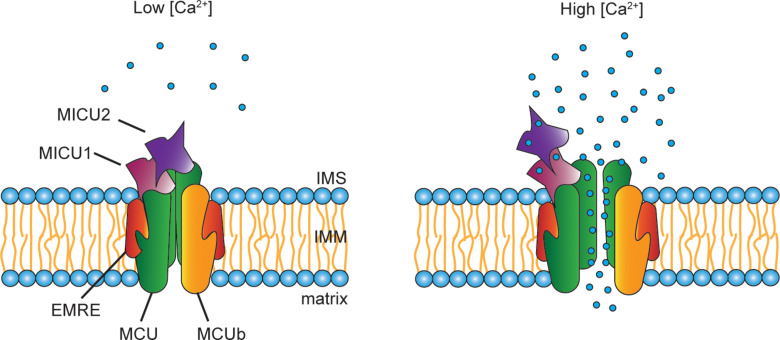

One critical aspect of the mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation is its sigmoidal response to cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels. In other words, at low cytosolic [Ca2+], mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake is negligible, while it exponentially increases when the cytosolic [Ca2+] exceeds a certain threshold (Figure 2). The different activity levels are the consequence of a fine-tuned modulation of channel opening, due to the presence of regulatory proteins located in the IMS, which interact with the pore-forming subunits. These regulators belong to the MICU family that comprises MICU1, MICU2 and MICU3, each of them characterized by different expression patterns and specific functions.

FIGURE 2.

Scheme of the MCU complex. The mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU) is composed of pore-forming subunits (i.e., MCU, MCUb, and EMRE) and regulatory subunits (i.e., MICU1, MICU2, and MICU3). MCU and the dominant-negative isoform MCUb are assembled into tetrameric complexes that span the IMM. EMRE is the essential MCU regulator, a 10 kDa protein located in the IMM whose absence causes the loss of the uniporter channel activity. A peculiar aspect of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake is its sigmoidal response to the extra-mitochondrial [Ca2+]. This property is due to the presence in the IMS of the MCU regulators, MICU1, MICU2, and, nearly exclusively in the nervous system, MICU3. At low cytosolic [Ca2+], little Ca2+ enters through the channel. Upon cell stimulation, the increase in cytosolic [Ca2+] is sensed by the EF-hands present on both MICU1 and MICU2. Consequently, conformational changes of the regulatory subunits take place, which allows the opening of the channel leading to Ca2+ entry inside the mitochondria.

MICU’s Family of MCU Regulators

MICU1 was the first component of the MCU complex to be identified, and it was described as a critical modulator of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (Perocchi et al., 2010). MICU1 plays a dual role in the control of MCU activity. On one hand, it keeps the channel closed when extra-mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration is below a certain threshold, thus avoiding continuous and sustained mitochondrial Ca2+ entry that eventually would cause Ca2+ overload. On the other hand, when extra-mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration exceeds a certain value, MICU1 acts as a cooperative activator of the MCU, warranting high Ca2+ conductivity (Mallilankaraman et al., 2012b; Csordás et al., 2013; Patron et al., 2014). Thus, MICU1 behaves as a gatekeeper of the MCU at low cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations and allows efficient mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake when cytosolic Ca2+ concentration increases (Csordás et al., 2013). Most of MICU1–/– mice die perinatally, and the ones that survive are affected by ataxia and muscle weakness (Antony et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016).

Later, two MICU1 paralog genes were described: MICU2 (formerly named EFHA1) and MICU3 (formerly named EFHA2), that similarly to MICU1 are located in the IMS (Hung et al., 2014; Lam et al., 2015). While the tissue expression pattern of MICU2 is similar to MICU1, MICU3 is expressed predominantly in the nervous system (Plovanich et al., 2013; Paillard et al., 2017). MICU2 forms an obligate heterodimer with MICU1, stabilized by a disulfide bond through two conserved cysteine residues. In many cell types, the stability of MICU2 depends on the presence of MICU1, as MICU1 knockdown causes a considerable reduction in MICU2 protein levels. This was reported in HeLa cells (Patron et al., 2014) and in patients’ fibroblasts carrying a loss-of-function homozygous deletion of MICU1 (Debattisti et al., 2019). However, in MICU1–/– MEFs as well as in MICU1–/– skeletal muscles, MICU2 protein levels were unaffected (Antony et al., 2016; Debattisti et al., 2019).

MICU1-MICU2 heterodimers regulate the activity of the MCU complex because of the presence of EF-hand domains. Ca2+ binding to these domains triggers conformational modifications resulting in channel opening. However, the entity of the Ca2+ affinity to the EF-hand domains is still an open issue. Measurements performed by isothermal titration calorimetry indicate that the Kd of the MICU1/Ca2+ interaction ranges from 4 to 40 μM (Wang et al., 2014; Vecellio Reane et al., 2016). However, measurements based on the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence registered a Kd of ∼300 nM (Kamer et al., 2017). Certainly, different methods in diverse experimental conditions could have yielded inhomogeneous results, indicating that this issue needs further clarification. As to the role of MICU2, electrophysiological studies performed in a planar lipid bilayer demonstrated that MICU2 inhibits MCU activity at low cytosolic [Ca2+], thus serving as the genuine gatekeeper of the channel (Patron et al., 2014).

Finally, the stoichiometry of the MCU regulators within the complex is still largely unknown. MICU1 multimers undergo molecular rearrangement during Ca2+ stimulation (Waldeck-Weiermair et al., 2015). In addition, Paillard et al. (2017) demonstrated that the MICU1/MCU ratio accounts for the different regulatory properties of the MCU complex in the different tissues. For instance, the high MICU1/MCU ratio present in the liver provides high cooperative activation of the channel and, simultaneously, increases the threshold of activation. Accordingly, small changes in cytosolic Ca2+ transients in hepatocytes are not sufficient to lead to mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation, which indeed requires sustained cytosolic Ca2+ increases. A different scenario occurs in the heart, in which the low MICU1/MCU ratio allows mitochondria to take up Ca2+ even at low cytosolic [Ca2+]. In this case, the beat-to-beat Ca2+ transients are decoded by the MCU with a low level of channel gating and a low grade of cooperativity, thus triggering an integrative Ca2+ accumulation (Paillard et al., 2017).

A lot of effort has been made to evaluate the molecular dynamics of the MICU1–MICU2 complex. In particular, Jia and coworkers resolved the human MICU2 structure to investigate the interactions between MICU1 and MICU2 in both the apo and Ca2+-bound form. Different residues are involved in the MICU1–MICU2 interaction depending on Ca2+ binding to EF-hands motifs. In the apo form, the critical amino acids for the complex formation are Glu242 in MICU1 and Arg352 in MICU2, while in the Ca2+-bound state Phe383 of MICU1 interacts with Glu196 in MICU2 (Wu et al., 2019). More recently, the cryo-electron microscopy structures of the human mitochondrial calcium uniporter holocomplex have been resolved in the apo and Ca2+-activated states. This study demonstrated that a single MICU1-MICU2 heterodimer is able to gate a channel formed by 4 MCU and 4 EMRE subunits. In agreement with previous reports, the structural analysis confirmed the existence of different conformations according to the [Ca2+]. In particular, this study demonstrates that, while at low [Ca2+] MICU1 covers the pore, in high [Ca2+] MICU1 moves away from the MCU surface to the edge of the MCU–EMRE tetramer, thus allowing pore opening (Fan et al., 2020).

A few years ago, our laboratory characterized an alternative splice variant of MICU1, namely MICU1.1 (Vecellio Reane et al., 2016). MICU1.1 is expressed only in the skeletal muscle, at higher levels compared to MICU1, and in the brain. Compared to MICU1, MICU1.1 contains an additional exon encoding four amino acids (EFWQ). MICU1.1 binds Ca2+ more efficiently compared to MICU1, and the heterodimer MICU1.1-MICU2 activates the channel at lower [Ca2+] than the MICU1-MICU2 heterodimer. These features are particularly relevant in the skeletal muscle, where MICU1.1 guarantees sustained ATP production. However, how the EFWQ domain affects the Ca2+-binding affinity and the protein structure is still under investigation.

MICU3, as already mentioned above, is specifically expressed in the brain (Plovanich et al., 2013). MICU3 forms disulfide bond-mediated dimers with MICU1 but not with MICU2 and acts as an activator of MCU activity (Patron et al., 2019). Accordingly, MICU3 silencing in primary cortical neurons impairs Ca2+ signaling suggesting a role in the control neuronal function. Thus, neurons express both MICU1–MICU2 dimers, which guarantee low vicious Ca2+ cycling in resting conditions, and MICU1-MICU3 dimers, which decrease the threshold of MCU opening ensuring mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake even in the presence of fast and small cytosolic Ca2+ transients. Recently, it has been demonstrated that MICU3 is involved in the metabolic flexibility of nerve terminals. MICU3, by tuning the Ca2+ sensitivity of the MCU complex, allows presynaptic mitochondria to take up Ca2+ in response to small changes in cytosolic [Ca2+] and thus to sustain axonal ATP synthesis (Ashrafi et al., 2020).

Other Putative MCU Modulators

Other mitochondrial proteins have been identified as putative modulators of MCU channel activity. Briefly, MCUR1, previously known as CCDC90a, was described as a modulator of MCU, since its silencing decreases mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation and basal mitochondria matrix [Ca2+] in HEK293T cells (Mallilankaraman et al., 2012a). However, Soubridge et al. demonstrated that MCUR1 plays also a critical role in the assembly of complex V, and its silencing drastically decreases the mitochondrial membrane potential (Paupe et al., 2015). Thus, whether MCUR1 is a direct modulator of the MCU, or rather it unspecifically blunts the driving force for mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake is still debated. Finally, SLC25A23 is a member of the solute carrier family that transport Mg-ATP/Pi across the IMM (Hoffman et al., 2014). Mutations of SLC25A23 EF-hand domains decrease mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation, thus suggesting that it may play a role in the control of MCU activity.

Ca2+ Targets of the Aerobic Metabolism: the Regulation of Mitochondrial Dehydrogenases

Mitochondrial Ca2+ plays various roles impinging on energy metabolism. It contributes to the regulation of shuttle systems through the IMM, that ensure the transport of nucleotides, metabolites, and cofactors (for a review see Rossi et al., 2019). In addition, it has been recently proposed that, within the matrix, Ca2+ directly modulates the activity of the ATP synthase (Territo et al., 2000) and the ETC (Glancy et al., 2013).

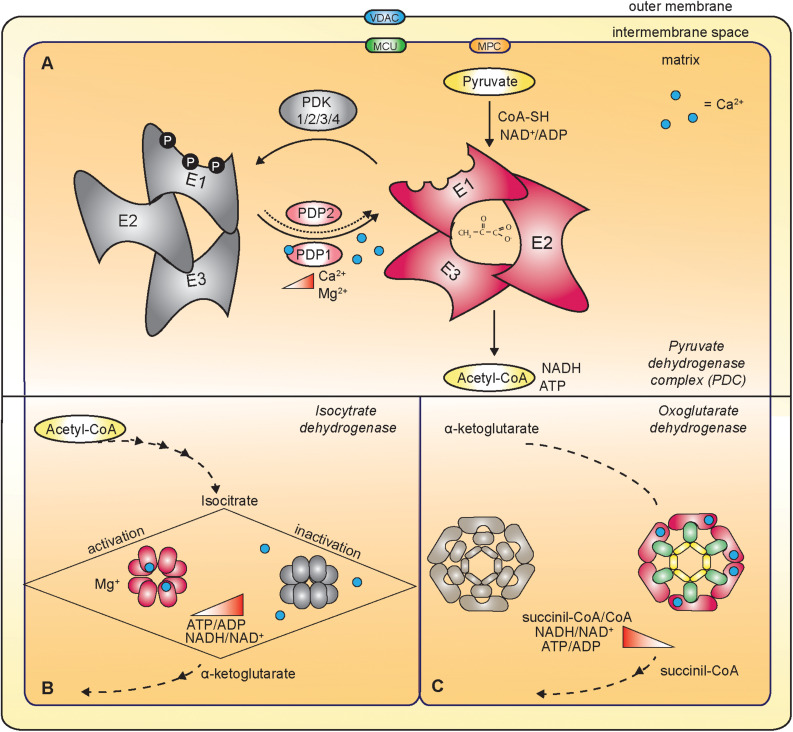

Most importantly, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake contributes to the regulation of energy production by impinging on the activity of mitochondrial dehydrogenases (Figure 3). In detail, FAD-linked glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase (GPDH) in the IMS, and pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) and oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (OGDH) in the matrix are directly or indirectly controlled by mitochondrial Ca2+ (Denton, 2009).

FIGURE 3.

Ca2+-dependent regulation of mitochondrial dehydrogenases. (A) The mitochondrial Ca2+ indirectly regulates the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) that oxidizes pyruvate to acetyl-CoA. PDC is composed of multiple copies of three components: pyruvate decarboxylase (E1), dihydrolipoate acetyltransferase (E2) and dihydrolipoate dehydrogenase (E3). In response to increased mitochondrial [Ca2+], the Ca2+-dependent isoform of pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase 1 (PDP1) dephosphorylates E1, thus triggering PDC activation. (B) Ca2+ directly activates the isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH). The ATP/ADP ratio negatively regulates the sensitivity of Ca2+ binding to IDH. (C) Oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (OGDH) is a multienzyme complex similar to the PDC. It is composed of dihydrolipoamide succinyl-transferase subunits (E2, green in the figure), oxoglutarate decarboxylase (E1, pink in the figure) and dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (E3, yellow in the figure). Ca2+-binding directly regulates the activity of the enzyme.

FAD-Linked Glycerol Phosphate Dehydrogenase (GPDH)

The glycerol phosphatase shuttle is composed of the mitochondrial FAD-linked glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase and the cytosolic NAD-dependent glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase. This shuttle transfers reducing equivalents from NADH in the cytosol to FADH2 in the mitochondrial matrix and eventually to the ETC. FAD-linked GPDH is a transmembrane protein of the IMM and possesses binding sites for glycerol phosphate and Ca2+ facing the IMS, thus sensing the cytoplasmic concentration of both these molecules (Cole et al., 1978; Garrib and McMurray, 1986). In particular, two EF-hand domains are responsible for the Ca2+-dependent activation of the enzyme (MacDonald and Brown, 1996).

Pyruvate Dehydrogenase (PDH)

The mammalian pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) has a molecular weight of about 8 MDa and contains multiple copies of three components that catalyze the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA. The pyruvate decarboxylase (E1) and the dihydrolipoate dehydrogenase (E3) are attached to a central core formed by the dihydrolipoate acetyltransferase (E2) (Hiromasa et al., 2004). The pyruvate decarboxylase is a tetramer composed of two different subunits (α2 and β2) catalyzing the irreversible step of the reaction. The PDC plays a critical role in the control of cellular metabolism and, accordingly, it is subjected to a fine regulation. Acetyl-CoA and NADH, the end-products of the oxidative reaction, inhibit PDC activity. PDC activity is also inhibited by the reversible phosphorylation of three sites on the E1 subunit (Denton, 2009) catalyzed by pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases (PDKs) and reverted by pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatases (PDPs). In particular, PDP1 and PDP2 are two isoforms belonging to the 2C/PPM family, with a molecular weight of ∼55 kDa and an Mg2+-dependent catalytic subunit (Teague et al., 1982; Karpova et al., 2003). The Ca2+-dependent activation of PDP1 results in the dephosphorylation of PDH, and eventually in the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl- CoA (Teague et al., 1982; Turkan et al., 2004). Notably, Ca2+ activates the PDP1, but not the PDP2, with a mechanism that is still under investigation. Although the PDP1 sequence contains a putative EF-hand motif (Lawson et al., 1993), the PDP1 crystal structure revealed that this domain is not involved in Ca2+ binding (Vassylyev and Symersky, 2007). Further studies, conducted using purified PDP1, showed that the Ca2+-binding site might be at the interface between the PDP1 and the E2 with a Kd close to 1 μM (Turkan et al., 2004).

Isocitrate Dehydrogenase (IDH)

This TCA cycle enzyme catalyzes the decarboxylation of isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate. IDH is an octamer of about 320 KDa and each unit of the octamer is composed of three different subunits (Nichols et al., 1993, 1995). The increase in ATP/ADP and NADH/NAD+ ratios inhibits the IDH enzyme, a feature that is shared with the other two Ca2+-dependent dehydrogenases, the pyruvate and the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenases. The sensitivity of Ca2+ binding to IDH is controlled by the ATP/ADP ratio. A decrease in the ATP/ADP ratio increases Ca2+ binding to IDH, which in turn leads to a decrease of the Km for isocitrate (Rutter and Denton, 1988, 1989).

Oxoglutarate Dehydrogenase (OGDH)

Oxoglutarate dehydrogenase catalyzes the TCA cycle reaction that converts α-ketoglutarate to succinyl-CoA. Its tetrameric structure shares some similarities with the PDC. It is characterized by a core composed of many subunits of dihydrolipoamide succinyl-transferase (E2), to which 2-oxoglutarate decarboxylase (E1) and dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (E3) subunits are attached. Increases in the succinyl-CoA/CoA and NADH/NAD+ ratios inhibit OGDH. In contrast to PDC, OGDH is not regulated by phosphorylation events. The Ca2+ binding to the OGDH leads to a decrease in the Km for α-ketoglutarate, similar to what happens for the IDH (Denton, 2009).

The Mitochondrial Ca2+ Uptake Regulates Liver Metabolism

Systemic metabolic adaptations to nutritional changes and to alterations in physical activity are necessary for energy homeostasis. In particular, several mechanisms and different organs are involved in the fine-tuned modulation of glucose metabolism. Among them, the liver plays a crucial role because of its capacity to store glucose during the fed state and to release it into circulation during fasting. Several signals control the balance between glycogen storage, glycogenolysis, and gluconeogenesis. Insulin is responsible for glycogen accumulation, whereas hyperglycemic hormones including glucagon and epinephrine are liable for gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis. Thanks to the seminal work of the Cabbold laboratory, single-cell Ca2+ dynamics of rat hepatocytes revealed the oscillatory pattern of cytosolic Ca2+ upon hormonal stimulation (Woods et al., 1986, 1987). Subsequently, the spatio-temporal pattern of Ca2+ transients was characterized, and the related regulation of Ca2+-sensitive proteins and mitochondrial enzymes were deciphered (Hajnóczky et al., 1995; Robb-Gaspers et al., 1998; for a review see Bartlett et al., 2014). In particular, Hajnóczky et al. (1995) demonstrated that the cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations translate into mitochondrial Ca2+ increases to stimulate aerobic metabolism. In detail, while slow increases of cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations are insufficient to activate mitochondrial metabolism, Ca2+ release from the ER upon InsP3 receptor opening triggers a rapid cytosolic Ca2+ oscillation and consequent mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. Thus, cytosolic [Ca2+] increases due to Ca2+ leak from stores are distinguished from those due to InsP3 receptors activation, the latter being the ones able to trigger a mitochondrial response. Each mitochondrial [Ca2+] spike triggered by specific cytosolic Ca2+ oscillation frequencies is accompanied by a maximal activation of the Ca2+-sensitive mitochondrial dehydrogenases.

To verify the role of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in liver metabolism, a hepatocyte-specific MCU–/– mouse model was developed (Tomar et al., 2019). MCU–/– hepatocytes displayed a depletion in mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ accompanied by a consequent impairment of the respiratory capacity. Interestingly, in MCU–/– hepatocytes lipid accumulation was observed. Mechanistically, AMPK inactivation was indicated as the trigger of this event. MCU deletion delays cytosolic Ca2+ clearance, and this increases Ca2+-dependent PP4 phosphatase activity. In turn, PP4 dephosphorylates AMPK. Remarkably, liver-specific AMPK deletion is sufficient to cause hepatic lipid accumulation. In addition, a gain-on-function knock-in MCU mouse model was produced (Tomar et al., 2019). In this model, hepatocytes displayed enhanced mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and respiratory capacity, AMPK was active, and liver triacylglycerol levels were decreased. Of note, MCU-overexpressing hepatocytes were resistant to lipid accumulation when placed in a high-glucose medium.

The regenerative capacity of the liver is of extreme pathophysiological importance and recent evidence demonstrates that Ca2+ dynamics takes part in this process. After partial hepatectomy, a cytosolic Ca2+ rise promotes the transition of regenerating hepatocytes through the proliferative state allowing liver growth. However, in MICU1–/– liver the cytosolic Ca2+ increase triggered by partial hepatectomy causes mitochondrial Ca2+ overload and eventually PTP opening. This generates an amplification of the pro-inflammatory phase and a block of the transition through the proliferative phase, leading to an impairment in liver recovery (Antony et al., 2016).

Mitochondria Ca2+ Signaling in the Control of Skeletal Muscle Function

Muscle physiology largely depends on two intracellular organelles: the SR for Ca2+ storage and release, and mitochondria for ATP synthesis (Franzini-Armstrong and Jorgensen, 1994). Skeletal muscle requires ATP to drive both actomyosin cross-bridge cycling and cytosolic Ca2+ buffering during contraction, the latter being ensured by ATP-dependent SERCA pump activity. Seminal work demonstrated that in rat myotubes mitochondria amplify 4–6 fold the cytosolic [Ca2+] increases triggered by various stimuli (Brini et al., 1997). This observation highlighted the pivotal role of mitochondria as essential players in the dynamic regulation of Ca2+ signaling in skeletal muscle, in accordance with the reported close apposition of ER and mitochondria that allows efficient Ca2+ uptake (Rizzuto et al., 1993, 1998). Electron microscopy studies demonstrated the presence of inter-organelle tethering proteins located at the juxtaposition between SR and mitochondria, that generate a physical coupling between these two organelles (Boncompagni et al., 2009) allowing rapid SR-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer. Early studies demonstrated an increase in NADH/NAD+ during the transition between resting and working muscle conditions, suggesting that an intracellular Ca2+ rise promotes mitochondrial metabolism in skeletal muscle (Sahlin, 1985; Duboc et al., 1988; Kunz, 2001). Recently, it was shown that inhibition of RyR1, thus a decrease in mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, triggers a reduction in the ATP-linked oxygen consumption, pointing out the control of aerobic metabolism by mitochondrial [Ca2+] (Díaz-Vegas et al., 2018). Importantly, glycolytic and oxidative muscles differ in terms of their mitochondria volume and metabolic properties. Specifically, slow-twitch fibers rely on oxidative phosphorylation, displaying a great fatigue resistance, while fast-twitch fibers manly rely on glycolysis as a source of ATP.

The importance of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in skeletal muscle physiology is demonstrated by the disease phenotype of patients carrying mutations in the MICU1 gene. Loss of function mutations cause myopathy, learning difficulties and extrapyramidal movement disorders (Logan et al., 2014). Other patients, carrying a homozygous deletion of the exon 1 of MICU1 show fatigue, lethargy, and weakness (Lewis-Smith et al., 2016). To clarify whether the muscle defects are due to impaired muscle MICU1 function or rather are secondary to neuronal disorders, a skeletal muscle MICU1–/– mouse model was developed (Debattisti et al., 2019). These mice are characterized by muscle weakness, fatigue, and increased susceptibility to damaging contractions, indicating that loss of MICU1 in the muscle is causative of the disease phenotype. In addition, pharmacological inhibition of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake by MICU1 targeting molecules impairs myotubes growth (Di Marco et al., 2020).

MCU deletion in MCU–/– mouse model causes a significant impairment in exercise capacity (Pan et al., 2013). In isolated mitochondria of the MCU–/– muscles resting matrix Ca2+ levels are reduced by 75% compared to WT mitochondria, and Ca2+-dependent PDH phosphorylation is increased. These data are in accordance with the role of mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation to regulate ATP production necessary to maintain healthy muscle functionality.

Further studies were performed by muscle-restricted modulation of MCU expression (Mammucari et al., 2015). In particular, MCU overexpression and downregulation trigger muscle hypertrophy and atrophy, respectively. The control of skeletal muscle mass by mitochondrial Ca2+ modulation is due to the activation of two major hypertrophic pathways of skeletal muscle, PGC-1α4 and IGF1-AKT/PKB. Surprisingly, these effects are independent of the control of aerobic metabolism, as demonstrated by various pieces of evidence. Firstly, PDH activity, although defective in MCU silenced muscles, was unaffected in MCU overexpressing muscles and, secondly, hypertrophy was comparable in both oxidative and glycolytic muscles (Mammucari et al., 2015).

A muscle-specific MCU knockout mouse (skMCU–/–), besides corroborating the role of MCU in maintaining muscle mass, helped to elucidate the contribution of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in muscle metabolism. Furthermore, this animal model was informative on how the MCU-dependent skeletal muscle oxidative metabolism systemically impinges on substrate availability (Gherardi et al., 2018). Metabolically, skMCU–/– mice were characterized by defective glucose oxidation, which was evident by increased blood lactate and by decreased oxygen consumption rate (OCR) of myofibers kept in a high-glucose medium. Skeletal muscle glucose uptake was increased as well as glycogen content, indicative of unaffected insulin sensitivity but inefficient glucose utilization.

Despite reduced muscle force and running capacity during exhaustion exercise, muscle performance was not dramatically impaired. This was due to an increase in fatty acids (FA) oxidation, which significantly contributed to basal OCR (Gherardi et al., 2018). A second skeletal muscle-specific MCU KO model was characterized on the one hand by reduced sprinting exercise performance, on the other hand by enhanced muscle performance under condition of fatigue, where the FA metabolism is predominant (Kwong et al., 2018). Because of the altered muscle glucose utilization, liver and adipose tissue responded with enhanced catabolism. Hepatic gluconeogenesis, lipolysis and thus circulating ketone bodies were increased. Furthermore, adipose tissue lipolysis was enhanced, resulting in a reduction of the body fat mass both in adulthood (Gherardi et al., 2018) and in aging (Kwong et al., 2018). The main trigger of this metabolic rewiring is the reduced pyruvate dehydrogenase activity, which is tightly controlled by mitochondrial Ca2+ as indicated by genetic experiments (Gherardi et al., 2018).

In accordance, a skeletal muscle-specific mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC) knockout mouse strikingly resembled the phenotype of skMCU–/– mouse. In skeletal muscle, MPC deletion decreased glucose oxidation despite increased glucose uptake and lactate production. This triggered enhanced FA oxidation and Cori cycling, with an overall increase in energy expenditure. Thus, skeletal-muscle restricted MPC deletion accelerated fat mass loss when mice were fed again with a chow diet after high-fat diet-induced obesity (Sharma et al., 2019). Altogether these studies support a model in which impaired mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and mitochondrial pyruvate entry inhibition lead to similar defects in glucose oxidation, which result in overlapping local and systemic metabolic adaptations. These data point to impaired pyruvate oxidation as the main contributor to the observed metabolic rewiring.

Cardiac Energetics Is Essential for Proper Heart Function

In the last decade the contribution of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake to the regulation of cardiac energetics has been deeply investigated. Pozzan and coworkers demonstrated that mitochondrial Ca2+ transients occur beat-to-beat, and participate in shaping the systolic Ca2+ peaks in neonatal cardiomyocytes. The presence of high [Ca2+] microdomains generated at the SR/mitochondria contacts allows mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake during systole resulting in a significant buffering of cytosolic Ca2+ peaks. Ca2+ is eventually released back to the cytoplasm during diastole because of the presence of the Na2+/Ca2+ exchanger and of the Ca2+/H+ antiporter. In addition, the genetic modulation of MCU, thus the alteration of mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation, directly affects the amplitude of the cytoplasmic Ca2+ oscillations in neonatal cardiomyocytes (Drago et al., 2012). However, whether this scenario occurs in adult cardiomyocytes and in the heart, in which it was proposed that mitochondrial Ca2+ entry does not rely on a cytosolic Ca2+ threshold, is still a matter of debate (Boyman et al., 2014).

In the last few years, many in vivo mouse models have been generated to investigate the role of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in the control of heart function. According to both constitutive and cardiac-specific MCU–/– mouse models, MCU is dispensable for mitochondria bioenergetics in the heart at baseline (Pan et al., 2013; Kwong et al., 2015). The heart function of the constitutive MCU knockout mouse is unaffected upon β-adrenergic stimulation, suggesting that long-term adaptations may occur (Holmström et al., 2015). However, in the inducible cardiac-specific MCU knockout mouse, during the fight or flight response an increase in the mitochondrial ATP production is required to support the elevated energy demand of the augmented heart rate (Kwong et al., 2015; Luongo et al., 2015). In addition, hearts expressing a dominant-negative MCU or overexpressing the MCUb treated with the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol show an impairment in the heart rate acceleration (Wu et al., 2015; Lambert et al., 2019). In the conditional MCUb heart-specific transgenic mouse model mitochondrial bioenergetics was impaired because of increased PDH phosphorylation levels leading to a decrease in the maximal respiration and in the reserve capacity. The impairment in the heart responsiveness was highlighted by the fact that these mice did not survive after IR injury. However, long-term induction of MCUb expression was accompanied by a rescue of the cardiac function and reduced infarct size, most likely because of compensatory mechanisms triggering PDH dephosphorylation and thus activation (Lambert et al., 2019). In addition, a change in the stoichiometry of the MCU complex was observed in the hearts of these mice. MCU, MICU1, and MICU2 levels were increased despite decreased association of MICU1 and MICU2 to the MCU complex (Lambert et al., 2019).

The inducible cardiac-specific MCU–/– mouse model was further investigated to assess ex vivo cardiac functions (Altamimi et al., 2019). Surprisingly, the isolated MCU–/– hearts showed enhanced cardiac function even at baseline, which persisted after isoproterenol stimulation. Thus, heart-specific mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake inhibition hampers the cardiac response to β-adrenergic stimulation in vivo (Kwong et al., 2015; Luongo et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2015), but not ex vivo (Altamimi et al., 2019). This suggests that the whole-body adrenergic response has a different impact on heart function compared to direct stimulation. A detailed analysis of energetic substrates preference demonstrated that the MCU-deleted hearts rely on increased FA oxidation in response to β-adrenergic stimulation. FA oxidation correlates with a decrease in malonyl-CoA levels, and with increased acetylation of the β-oxidation enzyme β-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (β-HAD) (Altamimi et al., 2019).

The main player of mitochondrial Ca2+ efflux, essential for the maintenance of mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis, is the mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCLX), which is encoded by the Slc8b1 gene (Palty et al., 2010). Recent work helped to elucidate the consequence of Ca2+ efflux impairment on heart function. The conditional cardiomyocyte-specific Slc8b1 deletion causes sudden death in most animals due to acute myocardial dysfunction and fulminant heart failure (Luongo et al., 2017). Slc8b1 knockout hearts display sarcomere disorganization, necrotic cell death and fibrosis, accompanied by left ventricle dilation and decreased function. Mechanistically, activation of the mPTP was responsible for the phenotype, as demonstrated by the fact that mating of these mice with cyclophilin D (CypD)-null mice rescues heart function and survival. On the contrary, cardiac-specific NCLX transgenic hearts were characterized by increased efflux capacity, decreased mPTP activation, and were protected against IR injury and ischemic heart failure.

Also, perturbations in the pyruvate dehydrogenase activity in the heart cause metabolic dysfunction and subsequently, cardiomyopathy. Patel and coworkers generated a heart and skeletal muscle-specific PDH knockout mouse (H/MS-PDCKO) (Sidhu et al., 2008). PDC activity is absent in both skeletal muscle and heart of these animals. All the H/MS-PDCKO mice died 7 days post-weaning on a chow diet, and the death was due to an impairment of the left ventricular systolic function, demonstrating that the consequent increase in the glycolysis rate was not sufficient to produce the ATP required for normal cardiac function. In contrast, when H/MS-PDCKO mice were weaned on a high-fat diet they survived for many months. However, even in this case, these mice developed left ventricular hypertrophy when they returned to a chow diet. These data suggest that PDC activity ensures metabolic flexibility in the hearts. Furthermore, Gopal et al. (2018) generated an inducible cardiac-specific PDH knockout model. In these mice, substrate utilization and cardiac function were monitored. The authors observed a metabolic rewiring which includes a reduction in the myocardial glucose oxidation and an increase in the FA oxidation. This metabolic switch did not alter the systolic function, however it impaired the diastolic function causing a cardiomyopathy-like phenotype similar to diabetes or obesity.

These data suggest that, like in skeletal muscle, decreased mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and impaired pyruvate oxidation increase β-oxidation in the heart. Recent work by Wescott et al. (2019) indicates that while mitochondrial [Ca2+] regulates the entry of pyruvate and glutamate into the TCA cycle, lipid oxidation is not controlled by mitochondrial [Ca2+]. Thus, in a context of mitochondrial Ca2+ impairment, fatty acids are readily oxidized to sustain energy demand.

Ca2+ Signaling Plays a Central Role in Adipose Tissue Homeostasis

The study of the role of Ca2+ homeostasis in adipose tissue biology represents a relatively new area of research. Different pieces of evidence suggest that Ca2+ dysregulation may affect adipocyte function. Accordingly, it has been demonstrated that intracellular Ca2+ concentration regulates adipocyte lipid metabolism, thus controlling adipogenesis. Shi et al. (2000) showed that cytosolic [Ca2+] plays a biphasic regulatory role in adipocyte differentiation: on the one hand, an increase in cytosolic [Ca2+] suppresses the early stages of murine adipogenesis; on the other hand, it promotes the late stages of adipose differentiation. Most importantly, elevated intracellular [Ca2+] in adipocyte appears to contribute to the insulin-resistance of elderly hypertensive obese patients. Strikingly, 1 month of therapy with nitrendipine, a Ca2+ channel blocker, reduced blood pressure, decreased plasma insulin upon glucose stimulation to control values, and restored normal adipocyte glucose uptake (Byyny et al., 1992).

Specifically in the brown adipose tissue (BAT), early work on isolated adipocytes demonstrated that norepinephrine stimulation mobilizes intracellular Ca2+ stores (Connoly et al., 1984), and this was later confirmed by subsequent studies (Lee et al., 1993; Leaver and Pappone, 2002; Nakagaki et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2017). However, the role of Ca2+ signaling in BAT thermogenesis remained largely unexplored until recently, when Kcnk3, a K+ channel present on the brown adipocyte plasma membrane, was identified as a negative regulator of thermogenesis (Chen et al., 2017). In detail, cytosolic Ca2+ levels upon adrenergic stimulation are increased in Kcnk3-deficient brown adipocytes, suggesting that Kcnk3 limits NE-induced cytosolic [Ca2+] influx, which results in decreased cAMP production, thus attenuating lipolysis and thermogenic respiration.

It is well established that oxidative metabolism and, in general, mitochondrial bioenergetics are altered in metabolic syndrome, obesity and type 2 diabetes (Heinonen et al., 2019), and that normalizing mitochondrial function has the potential to restore insulin sensitivity. As an example, the treatment with rosiglitazone, a PPARγ agonist and a firmly established drug for type 2 diabetes (Lebovitz, 2019), triggers increased mitochondrial respiration and FA oxidation in ob/ob mice adipocytes (Wilson-Fritch et al., 2004) and induces the expression of mitochondrial structural proteins and cellular antioxidant enzymes (Rong et al., 2007). Nonetheless, while the contribution of mitochondrial metabolism to adipose tissue homeostasis is well known, the role of mitochondrial Ca2+ signaling is still largely unexplored. Recently, the link between MCU activity and the development of obesity and diabetes was investigated (Wright et al., 2017). In 3T3-L1 adipocytes, insulin resistance was accompanied by an increase of MCU and MICU1 expression and mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. Accordingly, the expression of MCU complex components was increased in the visceral adipose tissue (VAT) of obese patients, both pre-diabetic and diabetic, compared to lean individuals. Interestingly, upon bariatric surgery, the expression of MCU complex components in patients’ VAT returned to physiological levels, suggesting that mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation plays an active role in this pathology. Mcub overexpression, although insufficient to improve the defect in insulin-stimulated glucose uptake of insulin-resistant cells, restored ROS production to normal levels. In addition, Mcub overexpression reduced TNF-alpha and IL-6 expression, suggesting a possible role of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in obesity-associated inflammation (Wright et al., 2017). Recently, a BAT-specific MCU knockout mouse was characterized (Flicker et al., 2019). Despite the complete lack of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, no effects were observed in terms of cold tolerance and diet-induced obesity, suggesting that MCU is dispensable for BAT thermogenesis and metabolism. These last two studies reveal that MCU, in adipose tissue, plays different roles in pathology versus physiology. However, further work is needed to clarify the different role of mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation in metabolically different adipose tissue compartments, both in health and in disease states.

Further insights into the role of Ca2+ signaling in the regulation of adipose tissue metabolism comes from studies conducted in Drosophila melanogaster. In this animal model the fat body, which is considered the equivalent of the mammalian liver, adipose tissue, hematopoietic and immune systems, senses nutrient availability and controls the metabolic responses (Hotamisligil, 2006). Concerning the Ca2+ signaling, Stim, an ER membrane protein involved in store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE), was identified by RNAi screen among genes affecting adiposity in the fly (Baumbach et al., 2014). Stim downregulation in fat storage tissue decreases cytosolic Ca2+ levels and leads to an increase in the overall adiposity. This is due to the remote activation of the orexigenic short neuropeptide F in the brain (sNPF). Along with hyperphagia, the Stim-sNPF axis controls lipid metabolism, resulting in adipose tissue hypertrophy. Further evidence on the role of Ca2+ homeostasis in D. melanogaster lipid metabolism comes from studies on InsP3 receptor mutants, which are obese and display altered FA utilization (Subramanian et al., 2013). In addition, Huang and coworkers showed that dSeipin, which plays a central role in the lipid metabolism, interacts with dSERCA modulating the cytosolic [Ca2+] (Bi et al., 2014). Mutations in dSeipin cause a reduction in SERCA activity and a consequent decrease in ER Ca2+ levels, leading to an impairment in the fat storage. Moreover, in dSeipin mutants, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake is reduced, triggering a decrease in TCA cycle activity and accumulation of citrate, a key component of lipogenesis. The lipid storage defect in dSeipin mutant fat cells is rescued by the recovery of mitochondrial [Ca2+] or by the restoration of normal citrate levels (Ding et al., 2018).

Concluding Remarks

About 10 years after the identification of the genes encoding a fundamental MCU regulator (i.e., MICU1, Perocchi et al., 2010) and MCU itself (Baughman et al., 2011; De Stefani et al., 2011), a bulk of information on the channel function and the consequences of its dysfunction has been collected. Most of the studies are based on genetic manipulation of the MCU complex components in specific subcellular compartments or on the disease phenotype of patients carrying mutations in MCU-associated genes. Recently, studies conducted in metabolically active tissues have highlighted the importance of the MCU to warrant metabolic flexibility in the utilization of oxidable substrates. Lack of Ca2+ entry causes defective oxidative metabolism in liver, heart, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, and rewiring of substrate utilization that determines increased fatty acids oxidation in the heart and skeletal muscle, and lipid accumulation in the liver. Future work will further shed light on the importance of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and pyruvate oxidation on critical issues of metabolism, and on the cross-talk between different organs.

Author Contributions

GG and CM wrote the manuscript. HM prepared the figures. RR contributed to the critical insights. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. Research in our laboratory is supported by funding from the French Muscular Dystrophy Association (22493 to CM), the Italian Ministry of Research (Prin 2015W2N883_003 to CM), the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC) (IG18633 to RR), the University of Padua (STARS@UNIPD WiC grant 2017 to RR), the Italian Telethon Association (GGP16029 to RR), the Italian Ministry of Health (RF-2016-02363566 to RR), and the Cariparo Foundation (to RR).

References

- Altamimi T. R., Karwi Q. G., Uddin G. M., Fukushima A., Kwong J. Q., Molkentin J. D., et al. (2019). Cardiac-specific deficiency of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter augments fatty acid oxidation and functional reserve. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 127 223–231. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antony A. N., Paillard M., Moffat C., Juskeviciute E., Correnti J., Bolon B., et al. (2016). MICU1 regulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake dictates survival and tissue regeneration. Nat. Commun. 7:10955. 10.1038/ncomms10955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi G., de Juan-Sanz J., Farrell R. J., Ryan T. A. (2020). Molecular tuning of the axonal mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter ensures metabolic flexibility of neurotransmission. Neuron 105 678.e5–687.e5. 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baradaran R., Wang C., Siliciano A. F., Long S. B. (2018). Cryo-EM structures of fungal and metazoan mitochondrial calcium uniporters. Nature 559 580–584. 10.1038/s41586-018-0331-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett P. J., Gaspers L. D., Pierobon N., Thomas A. P. (2014). Calcium-dependent regulation of glucose homeostasis in the liver. Cell Calc. 55 306–316. 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman J. M., Perocchi F., Girgis H. S., Plovanich M., Belcher-Timme C. A., Sancak Y., et al. (2011). Integrative genomics identifies MCU as an essential component of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature 476 341–345. 10.1038/nature10234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumbach J., Hummel P., Bickmeyer I., Kowalczyk K. M., Frank M., Knorr K., et al. (2014). A drosophila in vivo screen identifies store-operated calcium entry as a key regulator of adiposity. Cell Metab. 19 331–343. 10.1016/J.CMET.2013.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M. J. (2001). The versatility and complexity of calcium signalling. Novartis Found. Symp. 239 52–64; discussion 6, 150–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi J., Wang W., Liu Z., Huang X., Jiang Q., Liu G., et al. (2014). Seipin promotes adipose tissue fat storage through the ER Ca2+-ATPase SERCA. Cell Metab. 19 861–871. 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boncompagni S., Rossi A. E., Micaroni M., Beznoussenko G. V., Polishchuk R. S., Dirksen R. T., et al. (2009). Mitochondria are linked to calcium stores in striated muscle by developmentally regulated tethering structures. Mol. Biol. Cell 20 1058–1067. 10.1091/mbc.e08-07-0783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyman L., Chikando A. C., Williams G. S. B., Khairallah R. J., Kettlewell S., Ward C. W., et al. (2014). Calcium movement in cardiac mitochondria. Biophys. J. 107 1289–1301. 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.07.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brini M., De Giorgi F., Murgia M., Marsault R., Massimino M. L., Cantini M., et al. (1997). Subcellular analysis of Ca2+ homeostasis in primary cultures of skeletal muscle myotubes. Mol. Biol. Cell 8 129–143. 10.1091/mbc.8.1.129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briston T., Roberts M., Lewis S., Powney B., Staddon J. M., Szabadkai G., et al. (2017). Mitochondrial permeability transition pore: sensitivity to opening and mechanistic dependence on substrate availability. Sci. Rep. 7:10492. 10.1038/s41598-017-10673-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byyny R. L., Verde M., Lo, Lloyd S., Mitchell W., Draznin B. (1992). Cytosolic calcium and insulin resistance in elderly patients with essential hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 5 459–464. 10.1093/ajh/5.7.459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri D., Sancak Y., Mootha V. K., Clapham D. E. (2013). MCU encodes the pore conducting mitochondrial calcium currents. eLife 2:e00704. 10.7554/eLife.00704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Zeng X., Huang X., Serag S., Woolf C. J., Spiegelman B. M. (2017). Crosstalk between KCNK3-mediated ion current and adrenergic signaling regulates adipose thermogenesis and obesity. Cell 171 836.e13–848.e13. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole E. S., Lepp C. A., Holohan P. D., Fondy T. P. (1978). Isolation and characterization of flavin-linked glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from rabbit skeletal muscle mitochondria and comparison with the enzyme from rabbit brain. J. Biol. Chem. 253 7952–7959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connoly E., Nanberg E., Nedrgaard J. (1984). Na+-dependent, alpha-adrenergic mobilization of intracellular (mitochondrial) Ca2+ in brown adipocytes. Eur. J. Biochem. 141 187–193. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08173.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csordás G., Golenár T., Seifert E. L., Kamer K. J., Sancak Y., Perocchi F., et al. (2013). MICU1 controls both the threshold and cooperative activation of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter. Cell Metab. 17 976–987. 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Stefani D., Raffaello A., Teardo E., Szabò I., Rizzuto R. (2011). A forty-kilodalton protein of the inner membrane is the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature 476 336–340. 10.1038/nature10230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debattisti V., Horn A., Singh R., Seifert E. L., Hogarth M. W., Mazala D. A., et al. (2019). Dysregulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and sarcolemma repair underlie muscle weakness and wasting in patients and mice lacking MICU1. Cell Rep. 29 1274.e–1286.e. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.09.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deluca H. F., Engstrom G. W. (1961). Calcium uptake by rat kidney mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 47 1744–1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton R. M. (2009). Regulation of mitochondrial dehydrogenases by calcium ions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1787 1309–1316. 10.1016/J.BBABIO.2009.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marco G., Vallese F., Jourde B., Bergsdorf C., Sturlese M., De Mario A., et al. (2020). A high-throughput screening identifies MICU1 targeting compounds. Cell Rep. 30 2321.e6–2331.e6. 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.01.081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Vegas A. R., Cordova A., Valladares D., Llanos P., Hidalgo C., Gherardi G., et al. (2018). Mitochondrial calcium increase induced by RyR1 and IP3R channel activation after membrane depolarization regulates skeletal muscle metabolism. Front. Physiol. 9:791. 10.3389/fphys.2018.00791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L., Yang X., Tian H., Liang J., Zhang F., Wang G., et al. (2018). Seipin regulates lipid homeostasis by ensuring calcium-dependent mitochondrial metabolism. Embo J. 37:e97572. 10.15252/embj.201797572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drago I., De Stefani D., Rizzuto R., Pozzan T. (2012). Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake contributes to buffering cytoplasmic Ca2+ peaks in cardiomyocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 12986–12991. 10.1073/pnas.1210718109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duboc D., Muffat-Joly M., Renault G., Degeorges M., Toussaint M., Pocidalo J. J. (1988). In situ NADH laser fluorimetry of rat fast- and slow-twitch muscles during tetanus. J. Appl. Physiol. 64 2692–2695. 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.6.2692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan C., Fan M., Orlando B. J., Fastman N. M., Zhang J., Xu Y., et al. (2018). X-ray and cryo-EM structures of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature 559 575–579. 10.1038/s41586-018-0330-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan M., Zhang J., Tsai C.-W., Orlando B. J., Rodriguez M., Xu Y., et al. (2020). Structure and mechanism of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter holocomplex. Nature 582 129–133. 10.1038/s41586-020-2309-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fieni F., Lee S. B., Jan Y. N., Kirichok Y. (2012). Activity of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter varies greatly between tissues. Nat. Commun. 3:1317. 10.1038/ncomms2325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicker D., Sancak Y., Mick E., Goldberger O., Mootha V. K. (2019). Exploring the in vivo role of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter in brown fat bioenergetics. Cell Rep. 27 1364.e5–1375.e5. 10.1016/J.CELREP.2019.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzini-Armstrong C., Jorgensen A. O. (1994). Structure and development of E-C coupling units in skeletal muscle. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 56 509–534. 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.002453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrib A., McMurray W. C. (1986). Purification and characterization of glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (flavin-linked) from rat liver mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 261 8042–8048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gherardi G., Nogara L., Ciciliot S., Fadini G. P., Blaauw B., Braghetta P., et al. (2018). Loss of mitochondrial calcium uniporter rewires skeletal muscle metabolism and substrate preference. Cell Death Differ. 26 362–381. 10.1038/s41418-018-0191-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgio V., Guo L., Bassot C., Petronilli V., Bernardi P. (2018). Calcium and regulation of the mitochondrial permeability transition. Cell Calc. 70 56–63. 10.1016/j.ceca.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glancy B., Willis W. T., Chess D. J., Balaban R. S. (2013). Effect of calcium on the oxidative phosphorylation cascade in skeletal muscle mitochondria. Biochemistry 52 2793–2809. 10.1021/bi3015983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal K., Almutairi M., Al Batran R., Eaton F., Gandhi M., Ussher J. R. (2018). Cardiac-specific deletion of pyruvate dehydrogenase impairs glucose oxidation rates and induces diastolic dysfunction. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 5:17. 10.3389/fcvm.2018.00017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajnóczky G., Robb-Gaspers L. D., Seitz M. B., Thomas A. P. (1995). Decoding of cytosolic calcium oscillations in the mitochondria. Cell 82 415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen S., Jokinen R., Rissanen A., Pietiläinen K. H. (2019). White adipose tissue mitochondrial metabolism in health and in obesity. Obes. Rev. 21:e12958. 10.1111/obr.12958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiromasa Y., Fujisawa T., Aso Y., Roche T. E. (2004). Organization of the cores of the mammalian pyruvate dehydrogenase complex formed by E 2 and E 2 Plus the E 3-binding protein and their capacities to bind the E 1 and E 3 components. J. Biol. Chem. 279 6921–6933. 10.1074/jbc.M308172200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman N. E., Chandramoorthy H. C., Shanmughapriya S., Zhang X. Q., Vallem S., Doonan P. J., et al. (2014). SLC25A23 augments mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, interacts with MCU, and induces oxidative stress-mediated cell death. Mol. Biol. Cell 25 936–947. 10.1091/mbc.E13-08-0502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmström K. M., Pan X., Liu J. C., Menazza S., Liu J., Nguyen T. T., et al. (2015). Assessment of cardiac function in mice lacking the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 85 178–182. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil G. S. (2006). Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 444 860–867. 10.1038/nature05485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung V., Zou P., Rhee H.-W., Udeshi N. D., Cracan V., Svinkina T., et al. (2014). Proteomic mapping of the human mitochondrial intermembrane space in live cells via ratiometric APEX Tagging. Mol. Cell 55 332–341. 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamer K. J., Grabarek Z., Mootha V. K. (2017). High-affinity cooperative Ca 2+ binding by MICU 1– MICU 2 serves as an on–off switch for the uniporter. Embo Rep. 18 1397–1411. 10.15252/embr.201643748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpova T., Danchuk S., Kolobova E., Popov K. M. (2003). Characterization of the isozymes of pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase: implications for the regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteomics 1652 126–135. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2003.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirichok Y., Krapivinsky G., Clapham D. E. (2004). The mitochondrial calcium uniporter is a highly selective ion channel. Nature 427 360–364. 10.1038/nature02246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovács-Bogdán E., Sancak Y., Kamer K. J., Plovanich M., Jambhekar A., Huber R. J., et al. (2014). Reconstitution of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111 8985–8990. 10.1073/pnas.1400514111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz W. S. (2001). Control of oxidative phosphorylation in skeletal muscle. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1504 12–19. 10.1016/S0005-2728(00)00235-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong J. Q., Huo J., Bround M. J., Boyer J. G., Schwanekamp J. A., Ghazal N., et al. (2018). The mitochondrial calcium uniporter underlies metabolic fuel preference in skeletal muscle. JCI Insight 3:e121689. 10.1172/jci.insight.121689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong J. Q., Lu X., Correll R. N., Schwanekamp J. A., Vagnozzi R. J., Sargent M. A., et al. (2015). The mitochondrial calcium uniporter selectively matches metabolic output to acute contractile stress in the heart. Cell Rep. 12 15–22. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam S. S., Martell J. D., Kamer K. J., Deerinck T. J., Ellisman M. H., Mootha V. K., et al. (2015). Directed evolution of APEX2 for electron microscopy and proximity labeling. Nat. Methods 12 51–54. 10.1038/nmeth.3179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert J. P., Luongo T. S., Tomar D., Jadiya P., Gao E., Zhang X., et al. (2019). MCUB regulates the molecular composition of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter channel to limit mitochondrial calcium overload during stress. Circulation 140 1720–1733. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson J. E., Niu X.-D., Browning K. S., Trong H., Le, Yan J., et al. (1993). Molecular cloning and expression of the catalytic subunit of bovine pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase and sequence similarity with protein phosphatase 2C. Biochemistry 32 8987–8993. 10.1021/bi00086a002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaver E. V., Pappone P. A. (2002). β-Adrenergic potentiation of endoplasmic reticulum Ca 2+ release in brown fat cells. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 282 C1016–C1024. 10.1152/ajpcell.00204.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebovitz H. E. (2019). Thiazolidinediones: the forgotten diabetes medications. Curr. Diab. Rep. 19:151. 10.1007/s11892-019-1270-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. C., Nuccitelli R., Pappone P. A. (1993). Adrenergically activated Ca2+ increases in brown fat cells: effects of Ca2+, K+, and K channel block. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 264 C217–C228. 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.1.C217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Smith D., Kamer K. J., Griffin H., Childs A.-M., Pysden K., Titov D., et al. (2016). Homozygous deletion in MICU1 presenting with fatigue and lethargy in childhood. Neurol. Genet. 2:e59. 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. C., Liu J., Holmström K. M., Menazza S., Parks R. J., Fergusson M. M., et al. (2016). MICU1 serves as a molecular gatekeeper to prevent in vivo mitochondrial calcium overload. Cell Rep. 16 1561–1573. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. C., Syder N. C., Ghorashi N. S., Willingham T. B., Parks R. J., Sun J., et al. (2020). EMRE is essential for mitochondrial calcium uniporter activity in a mouse model. JCI Insight 5:e134063. 10.1172/jci.insight.134063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan C. V., Szabadkai G., Sharpe J. A., Parry D. A., Torelli S., Childs A.-M., et al. (2014). Loss-of-function mutations in MICU1 cause a brain and muscle disorder linked to primary alterations in mitochondrial calcium signaling. Nat. Genet. 46 188–193. 10.1038/ng.2851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luongo T. S., Lambert J. P., Gross P., Nwokedi M., Lombardi A. A., Shanmughapriya S., et al. (2017). The mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger is essential for Ca2+ homeostasis and viability. Nature 545 93–97. 10.1038/nature22082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luongo T. S., Lambert J. P., Yuan A., Zhang X., Gross P., Song J., et al. (2015). The mitochondrial calcium uniporter matches energetic supply with cardiac workload during stress and modulates permeability transition. Cell Rep. 12 23–34. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald M. J., Brown L. J. (1996). Calcium activation of mitochondrial glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase restudied. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 326 79–84. 10.1006/abbi.1996.0049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallilankaraman K., Cárdenas C., Doonan P. J., Chandramoorthy H. C., Irrinki K. M., Golenár T., et al. (2012a). MCUR1 is an essential component of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake that regulates cellular metabolism. Nat. Cell Biol. 14 1336–1343. 10.1038/ncb2622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallilankaraman K., Doonan P., Cárdenas C., Chandramoorthy H. C., Müller M., Miller R., et al. (2012b). MICU1 is an essential gatekeeper for MCU-mediated mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake that regulates cell survival. Cell 151 630–644. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammucari C., Gherardi G., Zamparo I., Raffaello A., Boncompagni S., Chemello F., et al. (2015). The mitochondrial calcium uniporter controls skeletal muscle trophism in vivo. Cell Rep. 10 1269–1279. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.01.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E., Pan X., Nguyen T., Liu J., Holmström K. M., Finkel T. (2014). Unresolved questions from the analysis of mice lacking MCU expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 449 384–385. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.04.144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagaki I., Sasaki S., Yahata T., Takasaki H., Hori S. (2005). Cytoplasmic and mitochondrial Ca2+ levels in brown adipocytes. Acta Physiol. Scand. 183 89–97. 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2004.01367.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen N. X., Armache J.-P., Lee C., Yang Y., Zeng W., Mootha V. K., et al. (2018). Cryo-EM structure of a fungal mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature 559 570–574. 10.1038/s41586-018-0333-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols B. J., Hall L., Perry A. C., Denton R. M. (1993). Molecular cloning and deduced amino acid sequences of the gamma-subunits of rat and monkey NAD(+)-isocitrate dehydrogenases. Biochem. J. 295(Pt 2), 347–350. 10.1042/bj2950347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols B. J., Perry A. C., Hall L., Denton R. M. (1995). Molecular cloning and deduced amino acid sequences of the alpha- and beta- subunits of mammalian NAD(+)-isocitrate dehydrogenase. Biochem. J. 310(Pt 3), 917–922. 10.1042/bj3100917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxenoid K., Dong Y., Cao C., Cui T., Sancak Y., Markhard A. L., et al. (2016). Architecture of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature 533 269–273. 10.1038/nature17656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paillard M., Csordás G., Szanda G., Golenár T., Debattisti V., Bartok A., et al. (2017). Tissue-specific mitochondrial decoding of cytoplasmic Ca 2+ signals is controlled by the stoichiometry of MICU1/2 and MCU. Cell Rep. 18 2291–2300. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.02.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palty R., Silverman W. F., Hershfinkel M., Caporale T., Sensi S. L., Parnis J., et al. (2010). NCLX is an essential component of mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchange. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 436–441. 10.1073/pnas.0908099107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan X., Liu J., Nguyen T., Liu C., Sun J., Teng Y., et al. (2013). The physiological role of mitochondrial calcium revealed by mice lacking the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nat. Cell Biol. 15 1464–1472. 10.1038/ncb2868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patron M., Checchetto V., Raffaello A., Teardo E., Vecellio Reane D., Mantoan M., et al. (2014). MICU1 and MICU2 finely tune the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter by exerting opposite effects on MCU activity. Mol. Cell 53 726–737. 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patron M., Granatiero V., Espino J., Rizzuto R., De Stefani D. (2019). MICU3 is a tissue-specific enhancer of mitochondrial calcium uptake. Cell Death Differ. 26 179–195. 10.1038/s41418-018-0113-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paupe V., Prudent J., Dassa E. P., Rendon O. Z., Shoubridge E. A. (2015). CCDC90A (MCUR1) is a cytochrome c oxidase assembly factor and not a regulator of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Cell Metab. 21 109–116. 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perocchi F., Gohil V. M., Girgis H. S., Bao X. R., McCombs J. E., Palmer A. E., et al. (2010). MICU1 encodes a mitochondrial EF hand protein required for Ca2+ uptake. Nature 467 291–296. 10.1038/nature09358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plovanich M., Bogorad R. L., Sancak Y., Kamer K. J., Strittmatter L., Li A. A., et al. (2013). MICU2, a paralog of MICU1, resides within the mitochondrial uniporter complex to regulate calcium handling. PLoS One 8:e55785. 10.1371/journal.pone.0055785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaello A., De Stefani D., Sabbadin D., Teardo E., Merli G., Picard A., et al. (2013). The mitochondrial calcium uniporter is a multimer that can include a dominant-negative pore-forming subunit. Embo J. 32 2362–2376. 10.1038/emboj.2013.157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto R., Brini M., Murgia M., Pozzan T. (1993). Microdomains with high Ca2+ close to IP3-sensitive channels that are sensed by neighboring mitochondria. Science 262 744–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto R., Pinton P., Carrington W., Fay F. S., Fogarty K. E., Lifshitz L. M., et al. (1998). Close contacts with the endoplasmic reticulum as determinants of mitochondrial Ca2+ responses. Science 280 1763–1766. 10.1126/science.280.5370.1763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb-Gaspers L. D., Burnett P., Rutter G. A., Denton R. M., Rizzuto R., Thomas A. P. (1998). Integrating cytosolic calcium signals into mitochondrial metabolic responses. Embo J. 17 4987–5000. 10.1093/emboj/17.17.4987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong J. X., Qiu Y., Hansen M. K., Zhu L., Zhang V., Xie M., et al. (2007). Adipose mitochondrial biogenesis is suppressed in db/db and high-fat diet-fed mice and improved by rosiglitazone. Diabetes 56 1751–1760. 10.2337/db06-1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi A., Pizzo P., Filadi R. (2019). Calcium, mitochondria and cell metabolism: a functional triangle in bioenergetics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 1866 1068–1078. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2018.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter G. A., Denton R. M. (1988). Regulation of NAD+-linked isocitrate dehydrogenase and 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase by Ca2+ ions within toluene-permeabilized rat heart mitochondria. Interactions with regulation by adenine nucleotides and NADH/NAD+ ratios. Biochem. J. 252 181–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter G. A., Denton R. M. (1989). The binding of Ca2+ ions to pig heart NAD+-isocitrate dehydrogenase and the 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex. Biochem. J. 263 453–462. 10.1042/bj2630453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahlin K. (1985). NADH in human skeletal muscle during short-term intense exercise. Pflugers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 403 193–196. 10.1007/BF00584099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancak Y., Markhard A. L., Kitami T., Kovács-Bogdán E., Kamer K. J., Udeshi N. D., et al. (2013). EMRE is an essential component of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter complex. Science 342 1379–1382. 10.1126/science.1242993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A., Oonthonpan L., Sheldon R. D., Rauckhorst A. J., Zhu Z., Tompkins S. C., et al. (2019). Impaired skeletal muscle mitochondrial pyruvate uptake rewires glucose metabolism to drive whole-body leanness. eLife 8:e45873. 10.7554/eLife.45873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Halvorsen Y.-D., Ellis P. N., Wilkison W. O., Zemel M. B. (2000). Role of intracellular calcium in human adipocyte differentiation. Physiol. Genomics 3 75–82. 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2000.3.2.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidhu S., Gangasani A., Korotchkina L. G., Suzuki G., Fallavollita J. A., Canty J. M., et al. (2008). Tissue-specific pyruvate dehydrogenase complex deficiency causes cardiac hypertrophy and sudden death of weaned male mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 295 H946–H952. 10.1152/ajpheart.00363.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian M., Metya S. K., Sadaf S., Kumar S., Schwudke D., Hasan G. (2013). Altered lipid homeostasis in Drosophila InsP3 receptor mutants leads to obesity and hyperphagia. Dis. Model. Mech. 6 734–744. 10.1242/dmm.010017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teague W. M., Pettit F. H., Wu T. L., Silberman S. R., Reed L. J. (1982). Purification and properties of pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase from bovine heart and kidney. Biochemistry 21 5585–5592. 10.1021/bi00265a031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Territo P. R., Mootha V. K., French S. A., Balaban R. S. (2000). Ca 2+ activation of heart mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation: role of the F 0/F 1 -ATPase. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 278 C423–C435. 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.2.C423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]