Abstract

Many animal phyla have no representatives within the catalog of whole metazoan genome sequences. This dataset fills in one gap in the genome knowledge of animal phyla with a draft genome of Bugula neritina (phylum Bryozoa). Interest in this species spans ecology and biomedical sciences because B. neritina is the natural source of bioactive compounds called bryostatins. Here we present a draft assembly of the B. neritina genome obtained from PacBio and Illumina HiSeq data, as well as genes and proteins predicted de novo and verified using transcriptome data, along with the functional annotation. These sequences will permit a better understanding of host-symbiont interactions at the genomic level, and also contribute additional phylogenomic markers to evaluate Lophophorate or Lophotrochozoa phylogenetic relationships. The effort also fits well with plans to ultimately sequence all orders of the Metazoa.

Subject terms: Evolution, Computational biology and bioinformatics

| Measurement(s) | DNA • genome • sequence_assembly • sequence feature annotation |

| Technology Type(s) | DNA sequencing • sequence assembly process • sequence annotation |

| Sample Characteristic - Organism | Bugula neritina |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data: 10.6084/m9.figshare.12988355

Background & Summary

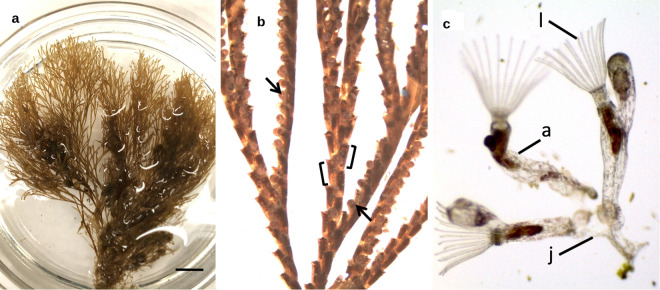

Colloquially referred to as “moss animals”, these nearly microscopic colonial animals with lattice-like connections compose the phylum Bryozoa (Fig. 1). The bryozoans can live in fresh and salt water, mostly in shallow depths less than 100 meters. As Protostomes, bryozoans have a deep evolutionary past1. Bryozoan or bryozoan-like fossils have been dated to at least 470 MYA and possibly 550 MYA in the Ediacaran2. The long evolution history may explain the extensive radiation to over 5000–6000 estimated, mostly marine, bryozoan species3, though other researchers count about 4500 ectoprocta species4,5.

Fig. 1.

(a) Whole colony of a preserved B. neritina. Scale bar represents 10 mm. (b) Light micrograph of a preserved fecund B. neritina colony, with feeding zooids (in square brackets) arranged bi-serially and ovicells (arrowed). (c) One live ancestrula (a), the first feeding zooid developed from a larva, and a juvenile B. neritina colony (j) with two fully developed autozooids with extended lophophores (l), at the base of which are the mouths of each feeding zooid.

Bryozoans were previously classified as the phylum Ectoprocta4. However, the phylogenetic placement of bryozoans remains uncertain6. Genome sequences could assist phylogenetic analyses, possibly by providing new markers for study7. To date, no complete ectoprocta or bryozoan nuclear genomes appear conceptually nor have been completed8.

In the 1960s, Bugula neritina was found to possess a group of macrolide polyketide lactones called the bryostatins, which are promising anti-neoplastic agents with several modes of action that are important in biomedical research9,10. Several studies have shown that bryostatins originate from a bryozoan bacterial symbiont “Candidatus Endobugula sertula”11–13. Sequencing and understanding the genome of this species as a representative of a little known phylum may reveal novel mechanisms for how useful natural products can be generated and the extent of host-microbe interactions. This effort adds to the growing catalogue of marine invertebrate genomes supported by the Global Invertebrate Genomics Alliance14.

To fill in a gap in the sequencing of animal genomes for understanding the tree of life, we sequenced and assembled the first nuclear Bryozoan genome - the draft genome of B. neritina - using PacBio and Illumina HiSeq data.

We assembled a draft genome of 214 Mb with 3,547 contigs and N50 of 94 kb (see Table 1 for details). Overall, the B.neritina genome displayed a low to moderate repetitive DNA content - repeats comprise 25.9% of the draft genome (see Supplemental Table 1). We have predicted 25,318 protein-coding genes with functional annotation and assigned orthologs from the eggNOG database15.

Table 1.

Genome assembly statistics.

| # contigs (> = 1,000 bp) | 3547 |

| # contigs (> = 50,000 bp) | 1207 |

| Total length (> = 1,000 bp) | 214,69 Mb |

| Largest contig | 1,32 Mb |

| N50 | 94,086 bp |

| L50 | 595 |

| GC (%) | 35.26 |

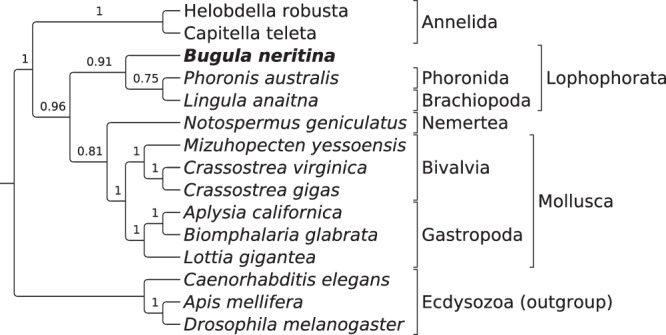

Lastly, we constructed a phylogenetic tree with the single-copy orthologs using BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs) phylogenomic approach16 (Fig. 2). We used available genomes from Sprialia (Lophotrochozoa), and three Ecdysozoa genomes as an outgroup. Only high-quality assemblies, with >80% assembled BUSCOs, were included in the study.

Fig. 2.

Coalescent species tree of Lophotrochozoa (Spiralia) inferred from 57 BUSCO ML phylogenies. Branch supports measured as local posterior probabilities.

Despite the strong support of the monophyletic origin of Spiralia, the exact phylogenetic relationships inside the group are still not fully determined. The reconstructed tree is generally in agreement with the phylogeny of Spiralia suggested recently by Marlétaz et al.17 based on transcriptomics analysis. Our analysis supports the monophyly of Lophophorata clade (brachiopods, phoronids and ectoprocts, including B.neritina). We cannot strongly support or reject the two other main clades from this work - Tetraneuralia (mollusks and entoprocts) and the clade combining annelids, nemerteans, and platyhelminthes - because of lack of assembled genomes and low posterior probabilities. Our data does not support the inclusion of annelids and nemerteans in a single monophyletic clade, but more data is needed for such a strong statement.

From an evolutionary standpoint, this first bryozoan genome fills a conspicuous gap in the metazoan tree of finished genomes, which currently shows a taxonomic bias due to sampling constraints and accessibility, as well as technology18. We also expect sequences that may be related to allorecognition19, and some sequences appeared in our analyses with weak similarities to previously identified allorecognition genes (Alr1). The B. neritina genome also fits into ambitious initiatives such as the Earth Biogenome Project, which aims to sequence the majority of eukaryotic taxa on the planet20, and so this genome fulfills the goals of both GIGA and EBP. Unexpected genetic markers and features in the B. neritina genome will likely be revealed after careful comparison with novel genomes from other phyla.

Methods

Sample collection and sequencing

Two adult colonies of B. neritina were collected by hand from floating docks in August 2015 from the public floating docks in Oyster, Virginia, U. S. A. (GPS coordinates 37.288 N, −75.923 W) and immediately preserved in RNAlater and stored at −20oC. Both samples were genotyped using the protocol described in Linneman et al.21, and found to be the “shallow” (S) genotype. Voucher samples of sequenced individuals have been deposited with the Ocean Genome Legacy with the Accession ID S00642 (https://www.northeastern.edu/ogl/cataloghttps://www.northeastern.edu/ogl/catalog).

High throughput DNA sequencing was first performed on an Illumina HiSeq Because scaffolds could not be fully closed, we then further sequenced eight 20 kb insert libraries on the Pacific Biosciences RS-II instrument using P6-C5 SMRT cells at the University of Florida ICBR. After preliminary quality filtering we obtained 8.8 G of raw reads, or x60 (given a preliminary genome size estimate of 135 Mb based on flow cytometry data). Genomic DNA extraction included a polysaccharide removal step. Pre-existing Illumina HiSeq data from symbiont genome-sequencing efforts (BioProject PRJNA322176) were also used for polishing.

Read quality check

We analysed reads using the SGA PreQC package22 (see Supplemental Data 1). Estimated genome size was 221 Mb, and the result showed a high level of heterozygosity (high frequency of variant branches in the k-de Bruijn graph). On 51-kmer plot we observed two-peak distribution, similar to the oyster dataset, also indicating high heterozygosity level. Based on GC%/k-mer coverage plots, we suspected the contamination by another organism, which was removed on the binning step (see Binning and validation subsection below).

Genome assembly

The genome was assembled from raw PacBio reads using Canu assembler v1.223. Draft CANU assembly was evaluated using QUAST 5.0.024. Final assembly was polished with Illumina reads in a single round using Pilon v. 1.2325.

Binning and validation

To avoid possible contamination (which is quite possible for marine invertebrate genomes), we binned obtained contigs with Metabat2 v.2.1226. We obtained seven bins, and assessed their taxonomic origin and completeness with CheckM27 and BUSCO (for possible bacterial and eukaryotic contamination, respectively). Also we extracted SSU rRNA and searched for homology in NCBI nr/nt database.

Two largest bins (134 Mb and 79 Mb) were attributed to B.neritina. Among other bins we observed two bacteria (80% and 24% completeness by CheckM), two small (<1 Mb) bins of unknown origin, and one uncultured labyrinthulid (15 Mb, 81.2% completeness by BUSCO). After keeping the B.neritina bins, the genome size was 214 Mb, close to the k-mer based estimation. Assembled genome was subjected to the contamination screen during the submission to the NCBI Assembly database, and no contamination was detected.

Repeat annotation and gene prediction

First, we analyzed de novo repetitive sequences using RepeatModeler v2.028. Using the obtained database, and Metazoan repeat database Repbase we identified and masked repeats in the draft genome using RepeatMasker v.4.0.6 (http://www.repeatmasker.org/http://www.repeatmasker.org/). Coding regions were predicted using AUGUSTUS v3.3.129 using previously published transcriptome of B.neritina30 as hints. The genes were annotated by eggNOG-mapper15.

Phylogenomic reconstruction

The phylogenomic tree was reconstructed using BUSCO Phylogenomics utility script31, with default parameters in the SUPERTREE mode. For the reconstruction we were using all available high-quality Spiralian genomes and three Ecdysozoans as an outgroup. “High quality” was defined as >80% of assembled BUSCOs from the database eukaryota_odb10. Following genomes were included in the final reconstruction: Helobdella robusta GCF_000326865.1, Capitella teleta GCA_000328365.1, Phoronis australis GCA_002633005.1, Lingula anatina GCF_001039355.2, Notospermus geniculatus GCA_002633025.1, Mizuhopecten yessoensis GCF_002113885.1, Crassostrea virginica GCF_002022765.2, C. gigas GCF_000297895.1, Aplysia californica GCF_000002075.1, Biomphalaria glabrata GCF_000457365.1, Lottia gigantea GCF_000327385.1, Caenorhabditis elegans GCF_000002985.6, Drosophila melanogaster GCF_000001215.4, Apis mellifera GCF_003254395.2.

57 BUSCOs were single copy in all 15 species. Each BUSCO group was aligned with MUSCLE32, trimmed with trimAl33, and ML phylogeny for each BUSCO was generated using IQ-TREE34. Coalescent species tree was inferred with Astral v.5.7.335.

Data Records

Assembled sequences along with gene annotation, have been deposited at NCBI Assembly database as ASM1079987v236. PacBio raw reads have been deposited to NCBI SRA database as SRR1114688637. Illumina raw reads have been deposited to NCBI SRA database as SRP08129238 as part of the earlier project to characterize the genome of the uncultured bryostatin-producing endosymbiont “Candidatus Endobugula sertula”. The B. neritina draft genome (PRJNA498596) will also be included in the umbrella Global Invertebrate Genomics Alliance (GIGA) whole genome dataset, BioProject PRJNA649812, for aquatic non-vertebrate metazoa.

Technical Validation

We evaluated the completeness of the genome assembly using Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) v2.016. This method relies on a defined set of ultra-conserved eukaryotic protein families for building a highly reliable set of gene annotations. The results showed that 86.3% (220 out of 255 BUSCOs) of the Eukaryota dataset were identified as complete in the B. neritina assembly (see Table 2). Together, the results indicated that our dataset represented a genome assembly with a high level of coverage. We also evaluated the quality of the assembly in terms of gene content using the Core Eukaryotic Genes Mapping Approach (CEGMA) pipeline39. We used a set of 248 core ultra-conserved genes, and in our analyses 96.19% of these genes were detected. The gene space completeness statistics showed that the assembly can be used for annotation and subsequent analysis.

Table 2.

BUSCO assessment of the B.neritina genome assembly.

| Total BUSCO groups searched | 255 |

|---|---|

| Missing BUSCOs (M) | 26 |

| Fragmented BUSCOs (F) | 9 |

| Complete and duplicated BUSCOs (D) | 14 |

| Complete and single-copy BUSCOs (S) | 206 |

| Complete BUSCOs (C) | 220 |

C:86.3%[S:80.8%, D:5.5%], F:3.5%, M:10.2%, n:255.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

A.K. and P.K. were supported by Russian Foundation for Basic Research Grants 17-00-00144 as part of 17-00-00148. A.K. was financially supported by the Government of the Russian Federation through the ITMO Fellowship and Professorship Program. MR’s contribution was supported by St. Petersburg State University, Russia (grant ID PURE 51555639). This genome will be considered as one of the target species of the Global Invertebrate Genomics Alliance (GIGA).

Author contributions

J.K. and G.L.-F. collected most of the samples. J.K. initiated the project. A.K. assembled genome. M.R. and A.K. performed most of the genome analyses and statistics. A.R. contributed analyses and manuscript writing. J.V.L. wrote the bulk of the early drafts, and carried out some gene analyses. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Code availability

The execution of this work was not involved using any custom code.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Mikhail Rayko, Aleksey Komissarov.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41597-020-00684-y.

References

- 1.Giribet, G. & Edgecombe, G. D. The invertebrate tree of life (Princeton University Press, 2020).

- 2.Zhuravlev AY, Wood R, Penny A. Ediacaran skeletal metazoan interpreted as a lophophorate. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2015;282:20151860. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bock, P. Bryozoa. world register of marine species (2014).

- 4.Brusca, R. C., Brusca, G. J. et al. Invertebrates. QL 362. B78 2003 (Basingstoke, 2003).

- 5.Appeltans W, et al. The magnitude of global marine species diversity. Current biology. 2012;22:2189–2202. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood, T. S. & Lore, M. The higher phylogeny of phylactolaemate bryozoans inferred from 18s ribosomal dna sequences. Bryozoan Studies 2004: Proceedings of the 13th International Bryozoology Association. Taylor & Francis Group, London 361–367 (2005).

- 7.Helmkampf M, Bruchhaus I, Hausdorf B. Phylogenomic analyses of lophophorates (brachiopods, phoronids and bryozoans) confirm the lophotrochozoa concept. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2008;275:1927–1933. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopez JV, Kamel B, Medina M, Collins T, Baums IB. Multiple facets of marine invertebrate conservation genomics. Annual review of animal biosciences. 2019;7:473–497. doi: 10.1146/annurev-animal-020518-115034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mackay HJ, Twelves CJ. Targeting the protein kinase c family: are we there yet? Nature Reviews Cancer. 2007;7:554–562. doi: 10.1038/nrc2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trindade-Silva AE, Lim-Fong GE, Sharp KH, Haygood MG. Bryostatins: biological context and biotechnological prospects. Current opinion in biotechnology. 2010;21:834–842. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharp KH, Davidson SK, Haygood MG. Localization of “candidatus endobugula sertula”and the bryostatins throughout the life cycle of the bryozoan bugula neritina. The ISME Journal. 2007;1:693–702. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller IJ, Vanee N, Fong SS, Lim-Fong GE, Kwan JC. Lack of overt genome reduction in the bryostatin-producing bryozoan symbiont “candidatus endobugula sertula”. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2016;82:6573–6583. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01800-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puglisi, M. P. & Becerro, M. A. Chemical ecology: the ecological impacts of marine natural products (CRC Press, 2018).

- 14.of Scientists GC. The global invertebrate genomics alliance (giga): developing community resources to study diverse invertebrate genomes. Journal of Heredity. 2014;105:1–18. doi: 10.1093/jhered/est084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huerta-Cepas J, et al. Fast genome-wide functional annotation through orthology assignment by eggnog-mapper. Molecular biology and evolution. 2017;34:2115–2122. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. Busco: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marlétaz F, Peijnenburg KT, Goto T, Satoh N, Rokhsar DS. A new spiralian phylogeny places the enigmatic arrow worms among gnathiferans. Current Biology. 2019;29:312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunn CW, Ryan JF. The evolution of animal genomes. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 2015;35:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicotra ML. Invertebrate allorecognition. Current Biology. 2019;29:R463–R467. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewin HA, et al. Earth biogenome project: Sequencing life for the future of life. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2018;115:4325–4333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720115115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linneman J, Paulus D, Lim-Fong G, Lopanik NB. Latitudinal variation of a defensive symbiosis in the bugula neritina (bryozoa) sibling species complex. PloS one. 2014;9:e108783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simpson JT. Exploring genome characteristics and sequence quality without a reference. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1228–1235. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koren S, et al. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome research. 2017;27:722–736. doi: 10.1101/gr.215087.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G. Quast: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1072–1075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walker BJ, et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PloS one. 2014;9:e112963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang DD, et al. Metabat 2: an adaptive binning algorithm for robust and efficient genome reconstruction from metagenome assemblies. PeerJ. 2019;7:e7359. doi: 10.7717/peerj.7359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parks DH, Imelfort M, Skennerton CT, Hugenholtz P, Tyson GW. Checkm: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome research. 2015;25:1043–1055. doi: 10.1101/gr.186072.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smit, A. F. & Hubley, R. Repeatmodeler open-1.0. Available fomhttp://www.repeatmasker.org (2008).

- 29.Hoff KJ, Stanke M. Predicting genes in single genomes with augustus. Current protocols in bioinformatics. 2019;65:e57. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong YH, et al. Transcriptome analysis elucidates key developmental components of bryozoan lophophore development. Scientific reports. 2014;4:6534. doi: 10.1038/srep06534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGowan, J. Busco phylogenomics utility script. https://github.com/jamiemcg/BUSCO_phylogenomics (2019).

- 32.Edgar RC. Muscle: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC bioinformatics. 2004;5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Capella-Gutiérrez S, Silla-Martnez JM, Gabaldón T. trimal: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen L-T, Schmidt HA, Von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. Iq-tree: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Molecular biology and evolution. 2015;32:268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang C, Rabiee M, Sayyari E, Mirarab S. Astral-iii: polynomial time species tree reconstruction from partially resolved gene trees. BMC bioinformatics. 2018;19:153. doi: 10.1186/s12859-018-2129-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.2020. NCBI Assembly. GCA_010799875.2

- 37.2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR11146886

- 38.2016. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP081292

- 39.Parra G, Bradnam K, Korf I. Cegma: a pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1061–1067. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- 2020. NCBI Assembly. GCA_010799875.2

- 2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR11146886

- 2016. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP081292

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The execution of this work was not involved using any custom code.