Graphical abstract

Both anomers of regioisomeric oxadiazole 2′-deoxyribo-C-nucleoside analogues were synthesized in efficient manner and their cytotoxic activities in five different cell lines were evaluated.

Keywords: C-Nucleoside; Cyano-sugar; Hoffer’s Chloro-sugar; 1,2,4-Oxadiazole; Anomers; Antitumor

Abstract

Various tetrazole and oxadiazole C-nucleoside analogues were synthesized starting from pure α- or β-glycosyl-cyanide. The synthesis of glycosyl-cyanide as key precursor was optimized on gram-scale to furnish crystalline starting material for the assembly of C-nucleosides. Oxadizole C-nucleosides were synthesized via two independent routes. First, the glycosyl-cyanide was converted into an amidoxime which upon ring closure offered an alternative pathway for the assembly of 1,2,4-oxadizoles in an efficient manner. Second, both anomers of glycosyl-cyanide were transformed into tetrazole nucleosides followed by acylative rearrangement to furnish 1,3,4-oxadiazoles in high yields. These protocols offer an easy access to otherwise difficult to synthesize C-nucleosides in good yield and protecting group compatibility. These C-nucleosides were evaluated for their antitumor activity. This work paves a path for facile assembly of library of new chemical entities useful for drug discovery.

Introduction

Unlike natural and synthetic N-nucleosides, C-nucleosides1, 2 are stable to enzymatic and acid-catalyzed hydrolysis of the glycosidic bond. Therefore, C-nucleosides offer a distinct advantage over the N-nucleosides for design of biologically active molecules. C-Nucleosides3, 4, 5 have also attracted the interest of researchers looking for hydrogen-bond interactions alternative to those produced in the classical Watson–Crick model. Among well-known antitumor C-nucleosides, pyrazofurin,6 showdomycin9 and tiazofurin10 are five-membered heterocyclic structures showing excellent biological activity (Fig 1 ). Despite of their remarkable activity profile, lack of specificity and neurotoxicity prohibited the clinical progress of these nucleosides. More recently, remdesivir (GS-5734)7, 8 has shown promise for the treatment of COVID-19. Immucillins is yet another important class of C-nucleosides advancing into clinical trials as inhibitor of purine nucleoside phosphorylase. These observations have motivated us to revisit the study of C-nucleosides, with a particular interest of designing 2′-deoxyribose analogues of various five membered heterocycle and their antiviral and antitumor activity.

Fig. 1.

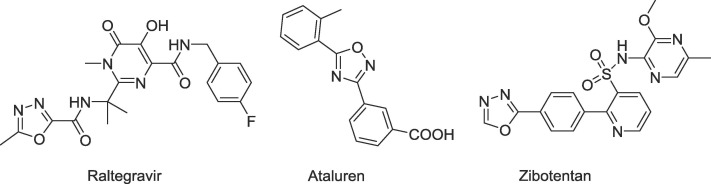

The presence of five-membered heterocyclic system is also a common feature in raltegravir,11 an antiviral drug for treatment of HIV. Interestingly, the oxadiazole ring system is also present in ataluren12 and zibotentan13 used for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) and prostate cancer, respectively (Fig 2 ). These facts and other reports on the promising biological activity of various regioisomeric oxadiazoles inspired us to synthesise and evaluate the biological activity of novel C-glycosides assembled from 2′-deoxyribose and oxadiazoles.

Fig. 2.

In particular, the oxadiazole ring14 is an essential part of the pharmacophore favouring ligand binding, act as a flat aromatic linker to place substituents in the proper orientation and finally mimics as bioisoster of esters, amides, carbamates, and hydroxamic esters. The 1,2,3-oxadiazole ring is unstable. 1,2,4-oxadiazole, 1,2,5-oxadiazole, and 1,3,4-oxadiazole are well known and appear in numerous marketed drugs. We have chosen 1,2,4-oxadiazole and 1,3,4-oxadiazole moiety for C-nucleoside synthesis. We envisioned the synthesis of a common building block by C—C bond formation at C1 and further integration of the heterocycle to assemble these C-nucleosides. We utilized the glycosyl cyanide as the key starting material which is obtained as mixture of α/β-cyanide anomers from 1-chloro carbohydrate by reaction with trimethyl silyl cyanide in the presence of a Lewis acid as catalyst. These two anomers of glycosyl cyanide were transformed into novel C-nucleosides. The main advantage of this strategy resides in availability of stereochemically pure glycosyl cyanide that is transformed into C-nucleosides without anomerization at the C1 position. The C-nucleosides of both anomers of 2′-deoxyriboside of tetrazoles and oxadiazoles synthesised are reported for the first time and the methodologies developed are general, which can be applied to construct other structurally diverse anomerically pure C-nucleosides.

Result and discussion

Herein, we describe a modular synthesis approach allowing rapid assembly of C-nucleoside library in an efficient manner. Synthesis of a common building block by C—C bond formation at C1 and further integration of the heterocycle was the key feature of our approach. We have divided our study in three parts: (i) synthesis and separation of glycosyl cyanine anomers on multigram scale, (ii) synthesis of 1,2,4-oxadiazole C-nucleoside via amidoxime intermediate and (iii) synthesis of 1,3,4-oxadozle via acylative rearrangement of tetrazole.

-

(i)

Synthesis and separation of glycosyl cyanide anomers on multigram scale:

The glycosyl cyanide is one of the most important type of C-glycosyl intermediate, which is usually obtained as mixture of cyanide anomers from commercially available Hoffer’s chloro sugar15 by reaction with trimethyl silyl cyanide in the presence of a Lewis acid as catalyst (Scheme 1 ). Synthesis of 2′-deoxy glycosyl cyanine anomers (1a and 1b) have been reported16 only on small-scale. Since 2′-deoxy glycosyl cyanine anomers (1a and 1b) are the key starting materials for our study, it was essential to optimize the yield and anomeric ratio with an ultimate objective of making it in hundred-gram quantity. Because chloro-sugar is devoid of neighbouring group participation, selective stereochemical outcome is challenging. Hence development of process which is robust and greener was undertaken. We screened various Lewis acids and solvents to improve yield and obtain better ratio of anomers in favour of β-selectivity. β-Anomer 1b is desirable to produce C-nucleoside having resemblance to the naturally abundant 2′-deoxy-nucleosides.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of glycosyl cyanide.

Upon screening of various Lewis acids, FeCl3 afforded best β:α = 5.7:1 ratio in 70% yield (entry 7 Table 1 ). Next solvent screening using nitromethane, toluene, 1,2-dichloroethane, tetrahydrofuran, acetonitrile, 1,2-dimethoxyethane, acetone and dimethyl formamide failed to improve the β:α ratio and yield compared to the reaction performed in dichloromethane. Considering desired β:α ratio, yield (93%) and scalability, SnCl4 was chosen as preferred Lewis acid for the present study. It is important to note that low temperature is essential for β-selectivity and high yield. Further optimization effort is underway in our laboratory to find a robust process with non-toxic Lewis acid.

Table 1.

Screening of Lewis acid for cyanation of Hoffer’s chloro sugar in DCM at −78 °C.

| Entry | Lewis Acid | Anomeric ratio (β/α) | Isolated Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SnCl4 | 3:1 | 93 |

| 2 | BF3.OEt2 | 2:1 | 70 |

| 3 | TMSOTf | 0.59:1 | 60 |

| 4 | CeCl3 | No Reaction (Starting material remain intact) | – |

| 5 | ZnCl2 | 2:1 | 55 |

| 6 | Mg (ClO4)2 | No Reaction (Insoluble in DCM) | – |

| 7 | FeCl3 | 5.7:1 | 70 |

The two anomers of glycosyl cyanides were easily separated by silica gel column chromatography and anomeric configuration was established by 1H NMR experiments. The SnCl4 protocol (entry 1 Table 1) was scaled-up to furnish 366 g of the pure β-anomer required for the transformation into various C-nucleosides containing five membered heterocycles. This route is the largest scale synthesis of glycosyl cyanide 1b reported to date in high yield.

-

(ii)

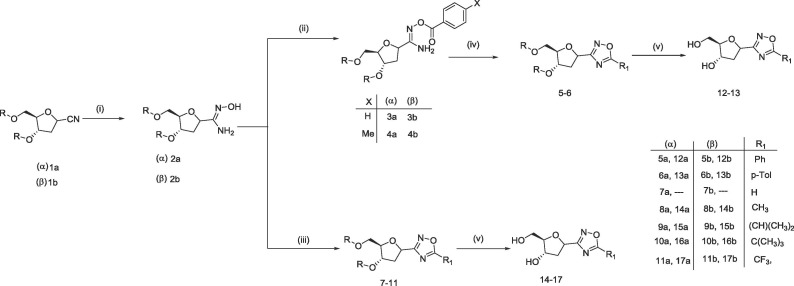

Synthesis of 1,2,4-oxadiazole C-nucleoside via amidoxime intermediate:

Nitrile functional group has served as an excellent handle to install several heterocyclic rings. Separately, both anomers of glycosyl cyanide (1a and 1b) were converted into amidoxime (2a and 2b) following Tiemann protocol17 using hydroxylamine hydrochloride under basic condition. Reaction was performed with NH2OH.HCl in presence of Hünigs base, instead of using NH2OH.HCl and Na2CO3 was reported by Adelfinskaya et al.18 Excellent yields were obtained for both anomers. These amidoxime derivatives were then converted into 1,2,4-oxadiazoles derivatives (5–6 and 7–11) following two distinct protocols (Scheme 2 ). First, sequential synthesis of O-acylated amidoximes using acetyl chloride followed by cyclization to 1,2,4-oxadiazole ring (5–6) using alkaline DMSO solution. Whereas the second protocol involve direct cyclization of amidoximes19 to 1,2,4-oxadiazoles20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 using orthoformate or acid anhydride in presence of BF3.Et2O as Lewis acid. The later protocol is shorter and offered higher yields compared to the first route. Deprotection of p-tolyl group was accomplished using NaOMe in methanol at room temperature in excellent yield except for 7a and 7b. Multiple product formation was observed on TLC for 7a and 7b. This phenomenon of multiple product formation can be attributed to the deprotonation28, 29 of acidic C5-H of 1,2,4-oxadiazole by NaOMe followed by ring opening and rearrangement.

-

(iii)

Synthesis of 1,3,4-oxadozle via acylative rearrangement of tetrazole:

Scheme 2.

(Reagents and Conditions): (i) NH2OH.HCl, DIEA, EtOH, reflux, 1 h (92–96%); (ii) Acyl chloride, 1,4-dioxane, RT, 16 h (73–97%); (iii) Trimethyl orthoformate, BF3.Et2O 110 °C, 3 h (or) Acid anhydride, BF3.Et2O, 110 °C (or) Trifluoroacetic anhydride, DCM, RT, 5 h (80–98%); (iv) KOH, DMSO, RT, 6 h (72–98%); (v) NaOMe, DCM: MeOH (3:2), RT, 16 h (48–97%).

In 1994, Kobe et al.30 synthesised 5-β-d-ribofuranosyl-1H-tetrazole from allononitrile using NaN3 and AlCl3 in excellent yield. Our attempt to utilize same protocol starting with glycosyl cyanide 1a or 1b resulted in low yield of tetrazole derivative along with other unidentified products. Therefore, tetrazole derivatives31, 32, 33 (18a and 18b) were successfully synthesized in good yield from both anomers of glycosyl cyanide (1a and 1b) using azide click reaction with copper and cupric sulphate in DMF at 120 °C. Unprotected tetrazole nucleosides (19a and 19b) were obtained by cleaving tolyl protecting group using sodium methoxide in methanol at room temperature (Scheme 3 ). The conversion of tetrazole to 1,3,4-oxadiazole derivatives34, 35, 36, 37, 38 was achieved either by reacting tetrazole derivatives with carboxylic acid anhydride in presence of hydroquinone under reflux or by reacting with carboxylic acid chloride in pyridine.39, 40, 41, 42 The Deprotection of p-tolyl group was executed using NaOMe in methanol at room temperature in excellent yield. However, the deprotection protocol suffers from a drawback for C5-unsubstituted and C5-substitution with electron withdrawing groups. In both cases, multiple product formation was observed due to the ring opening of the oxadiazole ring. This decomposition can be explained by the nucleophilic addition of NaOMe to C5-carbon and ring opening.43

Scheme 3.

(Reagents and Conditions): (i) NaN3, Cu, CuSO4, DMF, 120 °C, 16 h (87–90%); (ii) (R2CO)2O, hydroquinone, reflux, 1 h (or) R2COCl, Pyridine, 90 °C, 2 h (78–97%); (iii) NaOMe, DCM:MeOH (3:2), RT, 16 h (46–97%).

The postulated mechanism44 of this conversion is illustrated in Scheme 4 . 5-Substituted tetrazole undergoes N2-acylation upon treatment with acylation reagent due to steric bulk of 5-substitution. This unstable intermediate (INT-1) then ring opens via nitrogen extrusion and formation of N-acyl nitrilimine as putative intermediates (INT-2 and INT-3). These intermediates are then cyclized to form 1,3,4-oxadiazoles (20–25) in good yield. Structural elucidation of the new compounds described in this study was based on NMR and mass spectral data.

Scheme 4.

Plausible reaction mechanism for 2-substituted 1,3,4-oxadiazole ring formation from 18a or 18b.

Biological activity

We tested a set of 12 C-nucleosides both α-and β-anomers for their in-vitro cytotoxicity activity in five tumor cell lines,45 namely HeLa, MDA-MB-231 (breast cancer), PANC-1 (pancreatic cancer), PC3 (prostate cancer) and SK-OV-3 (ovarian cancer) using the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethyl thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay. Doxorubicin was used as a positive control to validate the MTT assay.46 Majority of the compounds failed to exhibit significant cytotoxicity against five cell lines tested at 10 μmol concentration. The results are summarized in the graph shown below. Compounds 15b and 28a exhibited modest (9–11%) inhibition of breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231. Whereas in case of SK-OV-3, we observed 10–14% inhibition exerted by five C-nucleosides (19b, 17b, 12b, 14b & 14a) (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Inhibition profile for 12 C-nucleosides against 5 cell lines. Doxorubicin was used as a control which exhibited >90% inhibition at 2 μM.

Summary

Various regio-isomeric five-membered oxadiazoles based 2′-deoxy-C-nucleosides were synthesized for the first time in good yield and high purity. All C-nucleosides were assembled from pure α- or β-anomer of glycosyl cyanide. The synthesis of glycosyl cyanide as key starting material was established on large-scale and in excellent yield. The easy accessibility of glycosyl cyanide further allows its utility in design of therapeutic oligonucleotides.47 The synthetic methodologies developed in this study are general and offer future scope to generate other nucleoside analogues for SAR study. Biological evaluation was carried out for synthesised compounds and shows reasonable cytotoxicity in five different tumor cell lines. Studies on antiviral activity of these compounds is in progress and it will be published elsewhere.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

SS acknowledge the help and support of Director, NIT Raipur for allowing him to register and pursue his PhD. SS also thanks Mr. Madika Chandrakanth for his help in preparation of manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data (experimental data and product characterization) to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.127612.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Experimental data and product characterization is available as SI material.

References

- 1.Štambaský Jan, Hocek Michal, Kočovský Pavel. C-nucleosides: synthetic strategies and biological applications. Chem Rev. 2009;109:6729–6764. doi: 10.1021/cr9002165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Clercq Erik. C-nucleosides to be revisited. J Med Chem. 2016;59(6):2301–2311. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qinpei Wu, Simons Claire. Synthetic methodologies for C-nucleosides. Synthesis. 2004;10:1533–1553. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-829106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Temburnikar Kartik, Seley-Radtke Katherine L. Recent advances in synthetic approaches for medicinal chemistry of C-nucleosides. Beilstein JOC. 2018;14:772–785. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.14.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marzag Hamid, Zerhouni Marwa, Tachallait Hamza. Modular synthesis of new C-aryl-nucleosides and their anti-CML activity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2018;28:1931–1936. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gutowski G.E., Sweeney M.J., DeLong D.C., Hamill R.L., Gerzon K., Dyke R.W. Biochemistry and biological effects of the pyrazofurins (pyrazomycins): initial clinical trial. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1975;255:544–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1975.tb29257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho A., Zhang L., Xu J. Discovery of the first C-nucleoside HCV polymerase inhibitor (GS-6620) with demonstrated antiviral response in HCV infected patients. J Med Chem. 2014;57:1812–1825. doi: 10.1021/jm400201a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Susan Amiriana E., Levy Julie K. Current knowledge about the antivirals remdesivir (GS-5734) and GS441524 as therapeutic options for coronaviruses. One Health. 2020;9 doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Showdomycin A.N., Nucleoside Antibiotic S., Roy-Burman P.-B., Visser D.W. Cancer Res. 1968;28:1605–1610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Dwyer Peter J., Dale Shoemaker D., Jayaram Hiremagalur N. Tiazofurin: A new antitumor agent. Invest New Drugs. 1984;2:79–84. doi: 10.1007/BF00173791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raltegravir C.JD., Keam S.J. Drugs. 2009;69(8):1059–1075. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200969080-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roy B., Friesen W.J., Tomizawa Y. Ataluren stimulates ribosomal selection of near-cognate tRNAs to promote nonsense suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(44):12508–12513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605336113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller K., Moul J.W., Gleave M. Phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled study of once-daily oral zibotentan (ZD4054) in patients with non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2013;16:187–192. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2013.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Llinàs Antonio, Wellner Eric, Plowright Alleyn T. Oxadiazoles in medicinal chemistry. J Med Chem. 2012;55:1817–1830. doi: 10.1021/jm2013248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bokor Eva, Szennyes Eszter, Csupasz Tibor. C-(2-Deoxy-D-arabino-hex-1-enopyranosyl)-oxadiazoles: synthesis of possible isomers and their evaluation as glycogen phosphorylase inhibitors. Carbohydr Res. 2015;412:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffer M. α-Thymidin. Chem Ber. 1960;93:2777–2781. doi: 10.1002/cber.19600931204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith Thomas H., Kent Mark A., Muthini Sylvester, Boone Steven J., Nelson Paul S. Oligonucleotide labelling methods. 4. Direct labelling reagents with a novel, non-nucleoside, chirally defined 2-deoxy-β-D-ribosyl backbone. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1996;15(10):1581–1594. doi: 10.1080/07328319608002458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tiemann T. Effect of hydroxylamine on nitriles. Chem Ber. 1884;17:126–129. doi: 10.1002/cber.18840170230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adelfinskaya Olga, Weidong Wu, Jo Davisson V., Bergstrom Donald E. Synthesis and structural analysis of oxadiazole carboxamide deoxyribonucleoside analogs. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucl Acids. 2005;24:1919–1945. doi: 10.1080/15257770500269267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flipo Marion, Desroses Matthieu, Lecat-Guillet Nathalie. Ethionamide boosters. 2. Combining bioisosteric replacement and structure-based drug design to solve pharmacokinetic issues in a series of potent 1,2,4-oxadiazole EthR inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2012;55(1):68–83. doi: 10.1021/jm200825u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maftei Catalin V., Fodor Elena, Jones Peter G. Synthesis and characterization of novel bioactive 1,2,4-oxadiazole natural product analogs bearing the N-phenylmaleimide and N-phenylsuccinimide moieties. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2013;9:2202–2215. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.9.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Arshad Mohammad, Khan Taqi Ahmed, Khan Meraj Alam. 1,2,4-oxadiazole nucleus with versatile biological applications. Int J Pharma Sci Res. 2014;5(7):303–316. [Google Scholar]; (b) Pratap Ram, Yarovenko V.N. Synthesis and antiviral activity of 3-(β-D-ribofuranosyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazole -5-carboxamide. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2000;19(5–6):845–849. doi: 10.1080/15257770008033026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kivrak Arif, Zora Metin. A novel synthesis of 1,2,4-oxadiazoles and isoxazoles. Tetrahedron. 2014;70:817–831. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2013.12.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (d) Pace Andrea, Pierro Paola. The new era of 1,2,4-oxadiazoles. Org Biomol Chem. 2009;7:4337–4348. doi: 10.1039/B908937C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sauer Andre C., Wolf Lucas, Quoos Natalia. A straightforward and high-yielding synthesis of 1,2,4-oxadiazoles from chiral N-protected α-amino acids and amidoximes in acetone-water: an eco-friendly approach. J Chem. 2019;9 doi: 10.1155/2019/8589325. Article ID 8589325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benltifa Mahmoud, Vidal Sébastien, Fenet Bernard. In search of glycogen phosphorylase inhibitors: 5-substituted 3-C-glucopyranosyl-1,2,4-oxadiazoles from β-D-glucopyranosyl cyanides upon cyclization of O-acylamidoxime intermediates. Eur J Org Chem. 2006:4242–4256. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200600073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zakeri Masoumeh, Heravi Majid M., Abouzari-Loft Ebrahim. A new one-pot synthesis of 1,2,4-oxadiazoles from aryl nitriles, hydroxylamine and crotonoyl chloride. J Chem Sci. 2013;125(4):731–735. doi: 10.1007/s12039-013-0426-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.John Kallikat Augustine, Akabote Vani, Hegde Shrivats Ganapati, Alagarsamy Padma. PTSA-ZnCl2: an efficient catalyst for the synthesis of 1,2,4-oxadiazoles from amidoximes and organic nitriles. J Org Chem. 2009;74:5640–5643. doi: 10.1021/jo900818h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donnier-Maréchal Marion, Goyard David, Folliard Vincent. 3-glucosylated 5-amino-1,2,4-oxadiazoles: synthesis and evaluation as glycogen phosphorylase inhibitors. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2015;11:499–503. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.11.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tóth Marietta, Kun Sándor, Bokor Éva. Synthesis and structure–activity relationships of C-glycosylated oxadiazoles as inhibitors of glycogen phosphorylase. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:4773–4785. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piccionello Antonio Palumbo, Pace Andrea, Buscemi Silvestre. Rearrangements of 1,2,4-oxadiazole: “one ring to rule them all”. Chem Heterocycl Compd. 2017;53(9):936–947. doi: 10.1007/s10593-017-2154-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pace Andrea, Buscemi Silvestre, Piccionello Antonio Palumbo, Pibiri Ivana. Recent advances in the chemistry of 1,2,4-oxadiazoles. Adv Heterocycl Chem. 2015;116:85–136. doi: 10.1016/bs.aihch.2015.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobe J., Prhavc M., Hohnjec M., Townsend L.B. Preparation and utility of 5-β-D-ribofuranosyl-1H-tetrazole as a key synthon for C-nucleoside synthesis. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1994;13(10):2209–2244. doi: 10.1080/15257779408013218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ulhas Bhatt, Five‐membered heterocycles with four heteroatoms: tetrazoles, Modern Heterocyclic Chemistry, pp.1401-1430, Chapter-15, DOI: 10.1002/chin.201201256.

- 32.Yakambram B., Srinivasulu K., Uday kumar N., Jaya-Shree A., Bandichhor Rakeshwar. Comproportionation based Cu(I) catalyzed [3+2] cycloaddition of nitriles and sodium azide. Chem Biol Interface. 2015;5(1):51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 33.(a) Qian W., Kumchok C.M., Markella K., Svitlana V.S., Dömling A. 1,3,4-Oxadiazoles by Ugi-tetrazole and Huisgen reaction. Org Lett. 2019;21:7320–7323. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Reichart B., Kappe C.O. High-temperature continuous flow synthesis of 1,3,4-oxadiazoles via N-acylation of 5-substituted tetrazoles. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:952–955. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.12.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arshad M. 1, 3, 4-oxadiazole nucleus with versatile pharmacological applications: a review. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2014;5(4):1124–1137. doi: 10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.5(4).1124-37. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pitasse-Santos Paulo, Sueth-Santiago Vitor, Lima Marco E.F. 1,2,4- and 1,3,4-oxadiazoles as scaffolds in the development of antiparasitic agents. J Braz Chem Soc. 2018;29(3):435–456. doi: 10.21577/0103-5053.20170208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pastuch-Gawołek Gabriela, Gillner Danuta, Król Ewelina, Walczak Krzysztof, Wandzik Ilona. Selected nucleos(t)ide-based prescribed drugs and their multi-target activity. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;865 doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.172747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pratap Ram, Yarovenko V.N. Synthesis and antiviral activity of 3-(β-D-ribofuranosyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazole-5-carboxamide. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucl Acids. 2000;19(5–6):845–849. doi: 10.1080/15257770008033026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nie Peng, Groaz Elisabetta, Daelemans Dirk, Herdewijn Piet. Xylo-C-nucleosides with a pyrrolo[2,1-f][1,2,4]triazin-4-amine heterocyclic base: synthesis and antiproliferative properties. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2019;29(12):1450–1453. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benedikt Reichart C., Kappe Oliver. High-temperature continuous flow synthesis of 1,3,4-oxadiazoles via N-acylation of 5-substituted tetrazoles. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:952–955. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.12.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huisgen R., Sauer J., Sturm H.J. Acylierung 5-substitutierter tetrazole zu 1.3.4-oxdiazolen. Angew Chem. 1958;70:272–273. doi: 10.1002/ange.19580700918. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sauer J., Huisgen R., Sturm H.J. Zur acylierung von 5-aryl-tetrazolen; ein duplikationsverfahren zur darstellung von polyarylen. Tetrahedron. 1960;11:241–251. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)93173-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roh Jaroslav, Vávrová Katerina, Hrabálek Alexandr. Synthesis and functionalization of 5-substituted tetrazoles. Eur J Org Chem. 2012:6101–6118. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201200469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guo-ping Lu, Lin Ya-mei. A base-induced ring-opening process of 2-substituted-1,3,4-oxadiazoles for the generation of nitriles at room temperature. J Chem Res. 2014;38:371–374. doi: 10.3184/174751914X14007780679741. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mansoori Yagoub, Sarvari Raana. New polynuclear nonfused bis(1,3,4-oxadiazole) systems. J Mex Chem Soc. 2014;58(2):205–210. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glomb Teresa, Szymankiewicz Karolina, Światek Piotr. Anti-cancer activity of derivatives of 1,3,4-oxadiazole. Molecules. 2018;23:3361. doi: 10.3390/molecules23123361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Al-Qubaisi Mothanna, Rozita Rosli, Yeap Swee-Keong, Omar Abdul-Rahman, Ali Abdul-Manaf, Alithee Noorjahan B. Selective cytotoxicity of goniothalamin against hepatoblastoma HepG2 Cells. Molecules. 2011;16:2944–2959. doi: 10.3390/molecules16042944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carnero Alejandro, Ṕerez-Rentero Sonia, Alagia Adele. The impact of an extended nucleobase-20 - deoxyribose linker in the biophysical and biological properties of oligonucleotides. RSC Adv. 2017;7:9579–9586. doi: 10.1039/c6ra26852h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental data and product characterization is available as SI material.