Abstract

Purpose

To combine Intravoxel Incoherent Motions (IVIM) imaging and diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI) which can aid in the quantification of different biological inspirations including cellularity, vascularity, and microstructural heterogeneity to preoperatively grade rectal cancer.

Methods

A total of 58 rectal patients were included into this prospective study. MRI was performed with a 3T scanner. Different combinations of IVIM-derived and DKI-derived parameters were performed to grade rectal cancer. Pearson correlation coefficients were applied to evaluate the correlations. Binary logistic regression models were established via integrating different DWI parameters for screening the most sensitive parameter. Receiver operating characteristic analysis was performed for evaluating the diagnostic performance.

Results

For individual DWI-derived parameters, all parameters except the pseudodiffusion coefficient displayed the capability of grading rectal cancer (p < 0.05). The better discrimination between high- and low-grade rectal cancer was achieved with the combination of different DWI-derived parameters. Similarly, ROC analysis suggested the combination of D (true diffusion coefficient), f (perfusion fraction), and Kapp (apparent kurtosis coefficient) yielded the best diagnostic performance (AUC = 0.953, p < 0.001). According to the result of binary logistic analysis, cellularity-related D was the most sensitive predictor (odds ratio: 9.350 ± 2.239) for grading rectal cancer.

Conclusion

The combination of IVIM and DKI holds great potential in accurately grading rectal cancer as IVIM and DKI can provide the quantification of different biological inspirations including cellularity, vascularity, and microstructural heterogeneity.

1. Introduction

It has been reported that there were around 0.7 million new cases of rectal cancer, accounting for approximately 40% of 1.8 million new colorectal cancer cases in 2018. Moreover, rectal cancer has posed a huge threat to human health because of high mortality rates (∼0.2 million deaths in 2018) [1]. Several factors including mesorectal fascia, stage, histopathologic grade, and vascular invasion are tightly correlated with the prognosis of rectal cancer [2, 3]. Currently, the widespread therapeutic option for rectal cancer, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, may inevitably lead to some serious side effects, especially when accurate evaluation of histopathological grade is not available [2, 4]. Therefore, noninvasive and accurate evaluation of the histopathologic grade of rectal cancer is of great clinical importance for directing subsequent clinical management.

Due to the clinical significance of providing different biological inspirations, Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging (DW-MRI) has shown tremendous clinical potential. During the past few decades, much effort has been made to propose novel DWI models such as intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) [5], diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI) [6], fractional order calculus (FROC) [7], and restriction spectrum imaging (RSI) [8] for characterizing tumor from different perspectives via different DWI-derived biological inspirations. Interestingly, although there are numerous DWI models, DWI-derived biological inspirations mainly contain cellularity, vascularity, and microstructural heterogeneity [9]. For instance, the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) sourced from conventional DWI provides the biological inspiration of cellular density which will increase with the progression of tumors. Differently, the DKI-derived apparent kurtosis coefficient (Kapp) indirectly represents the microstructural complexity in comparison to IVIM-derived f (perfusion fraction) that can quantify the vascularity [5]. Hence, combining these DWI-derived biological inspirations will pave the way for more comprehensively characterizing tumors from different perspectives. Numerous researchers have simultaneously combined multiple DWI models for achieving clinical objectives such as tumor diagnosis, staging, and grading [10–12]. However, innumerable attention has been paid to comparing the clinical effectiveness of different DWI-derived parameters, which aimed to explore the best DWI-derived parameter or DWI model for specific clinic purpose. The combination of different DWI models was hardly performed based on the DWI-derived biological inspiration. For example, Bai et al. compared the diagnostic value of different parameters calculated from monoexponential, biexponential, and stretched exponential DWI and DKI for grading glioma [13]. Li performed a comparative study of Gaussian and non-Gaussian DWI models for differential diagnosis of prostate cancer [14]. Moreover, excessive DWI models may weaken the clinical potential because of the long scanning time, low patient compliance, and difficult manipulation and postprocessing. Based on the aforementioned points, we hypothesized that (1) the combination of IVIM and DKI was sufficient to provide three main DWI-derived biological inspirations including cellularity, vascularity, and microstructural complexity. (2) Integrating these DWI-derived biological inspirations together will benefit the accurate grading of rectal cancer through more comprehensive tumor characterization. Thus, this research aimed to combine IVIM and DKI to grade rectal cancer via integrating different DWI-derived biological inspirations. Moreover, the correlations among the DWI-derived cellularity, vascularity, and microstructural complexity were also investigated. As far as we are aware, hardly has the integration of different DWI-derived biological inspirations been performed to grade rectal cancer.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

The approval from a local institute review board was obtained for this prospective research. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. A total number of 69 patients were recruited into this prospective research between December 2018 and August 2019. The inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria were established according to a previous research [2] and are listed as the follows:

Inclusion criteria:

Endoscopic biopsy-proven rectal cancer

More than one week of interval between biopsy and MRI

Exclusion criteria:

Poor quality of DKI or IVIM images caused by artifacts

Patients who underwent surgery before the MRI examination

Time interval between MR examination and surgery of more than 2 weeks

Preoperative neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy

Inaccessible clinical pathology results of histopathologic grade

2.2. MRI Protocols

All MRI measurements were performed with a 3T whole-body scanner (uMR 780, United Imaging Healthcare Co., Ltd.) with a twelve-channel coil. The MRI protocol mainly included a T2-weighted Fast Spin Echo sequence termed as FSE T2WI (echo time/repetition time, 103.1/4244.0 ms/ms; flip angle, 110°; FOV, 280 × 360 mm2; matrix, 336 × 432; slice thickness, 6 mm; intersection gap, 1.2 mm; and number of slices, 25), dynamic three-dimensional T1 weighted gradient echo (GRE) sequence (echo time/repetition time, 1.45/3.30 ms/ms; flip angle, 10°; FOV 280 × 500 mm2; and matrix, 336 × 480.), and oblique axial Single Shot- Echo Planar Imaging sequence termed as SS-EPI (echo time/repetition time, 86.2/4600.0 ms/ms; flip angle, 90°; FOV 180 × 240 mm2; matrix, 168 × 224; slice thickness, 4 mm; intersection gap, 1 mm; number of slices, 20; b values: 0, 10, 20, 30, 50, 80, 100, 150, 200, 400, 600, 800, 1500, and 2000 s/mm2; and scanning time: 4.7 min). It should be noted that both DKI and IVIM were based on the abovementioned SS-EPI sequence with different selections of b values for subsequent postprocessing.

2.3. Image Analysis

All the original data were processed with one in-house prototype software developed by MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, Mass).

2.3.1. IVIM

The quantitative pixelwise parameters derived from IVIM were obtained through the previously-reported fitting model [5]:

| (1) |

where S0 and Sb are, respectively, the signal intensity when a b value of 0 s/mm2 and other b values are applied. f is the perfusion volume fraction, D (unit: ×10−9 m2/s) is the true diffusion coefficient representing pure diffusion, and D∗ (unit: ×10−9 m2/s) is the pseudodiffusion coefficient representing perfusion related diffusion (incoherent microcirculation within the voxel). Moreover, the fitting of IVIM was based on the images of b values of 0, 10, 20, 30, 50, 80, 100, 150, 200, 400, 600, and 800 s/mm2.

2.3.2. DKI

The quantitative pixelwise parameters derived from the DKI were obtained through the previously-reported fitting model [6]:

| (2) |

where Sb and S0 are identical to those in IVIM. Dapp (unit: ×10−9 m2/s) and Kapp (unitless) are, respectively, the apparent diffusion coefficient and apparent kurtosis coefficient representing the degree to which molecular motion deviated from the Gaussian diffusion. Additionally, the fitting of DKI was based on the images of b values of 0, 800, 1500, and 2000 s/mm2.

Two radiologists (ZJ.G and CM.X), with 8 and 25 years' experience of gastrointestinal imaging were asked to draw the Volumes of Interest (VOIs) along the tumor border, which meant that all DWI-derived parameters were measured based on the whole-lesion method, and the entire tumor was maximally included into the VOI. The definitions of each VOI were based on the consensus of the abovementioned two radiologists. Before drawing VOIs, radiologists were blinded to the results of histopathological examination. For each slice within tumor, freehand regions were drawn along the border of the low signal of the tumor on the D map with T2WI images as the references. Necrosis, cyst, and haemorrhage were carefully excluded. In this way, the whole tumor was incorporated into the VOI. Then, the outlined regions were automatically copied to other parametric maps including f map, D∗ map for IVIM, and Dapp and Kapp map for DKI. Finally, the pixel-based average values for each parameter were acquired by means of the whole tumor averaging approach reported before [15].

2.4. Histopathological Evaluation

All pathological examinations were concluded by an experienced pathologist with more than 5 years' experience. Surgical specimens of rectal cancer were routinely prepared into 5 μm slices and, then, stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E). Histological grading was performed according to the WHO criteria [16]. Rectal cancer patients were classified as grade 1 (G1), grade 2 (G2), or grade 3 (G3) when gland-like structures of the tumor occupied greater than 95%, greater than 50% but less than or equal to 95%, or less than or equal to 50% of the volume, respectively.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Firstly, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was performed for analyzing normality. According to the result of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, independent Student's t-test was applied to see whether there existed significant differences between different groups (low grade (G1-2) and high grade (G3)). Moreover, one-way ANOVA and the Tukey post hoc test were performed for multiple comparison of quantitative diffusion parameters among the groups of G1, G2, and G3 rectal cancer. The Pearson correlation test was performed to assess the correlation coefficients abbreviated as r between the parameters. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed to establish the diagnostic model with the combination of different parameters including D (cellularity), f (vascularity), and Kapp (microstructural complexity) of IVIM and DKI which showed significant differences between low-grade and high-grade rectal cancer groups for subsequent ROC analysis. D∗ was excluded because it did not display a significant difference between the low-grade rectal cancer and high-grade rectal cancer. Although Dapp also displayed a significant difference between the low-grade and high-grade rectal cancer, it was excluded because of the following issues: (1) Dapp possesses the same biological insight of cellularity as D. (2) Eliminating the influence of perfusion, D is better at characterizing the true diffusion restriction resulted from cellularity [17]. As a result, the diagnostic model-based combinations of D and f (cellularity and vascularity), D and Kapp (cellularity and microstructural complexity), and f and Kapp (vascularity and microstructural complexity), as well as D and f and Kapp (cellularity and vascularity and microstructural complexity), were established via logistic regression. Besides introducing three variables (D, f, and Kapp), binary logistic regression analysis was also performed to evaluate which DWI-derived biological insight among cellularity, vascularity, and microstructure was the most sensitive for predicting high-grade rectal cancer by comparing the standardized regression coefficients (β) and the odds ratio (OR) of different parameters. The OR was calculated according to the following formula: OR=exp(|β|). In order to obtain the standardized regression coefficients of binary logistic regression analysis, D, f, and Kapp were, firstly, standardized as the Z score to eliminate the effect of dimension and quantity of data. It is worthwhile to be noted that, for obtaining more intuitive comparison, the odds ratio of f and D was defined as the ratio of the positive (high-grade rectal cancer in this research) probability after the variable decreased by one standard unit to the probability before the change, which was different from the standard definition. The definition of the odds ratio of Kapp was the same as the standard definition. The ROC (receiver operating characteristic curve) analysis was performed to evaluate the diagnostic performance of parameters showing significant differences between low-grade and high-grade rectal cancer groups together with their combinations by comparing the AUCs (area under curve). All parameters in this research were statistically analyzed with statistical tools including SPSS software (PASW Statistics 25.0 SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), Medcalc (MedCalc 9.0.2, Mariakerke, Belgium), R version 3.6.1 (R Core Development Team), and RStudio (RStudio Inc, Boston, MA, USA). It was regarded as having a statistical significance when the p value was less than 0.05.

3. Results

Between December 2018 and August 2019, a total of 69 patients were initially recruited into this prospective study. Three patients were excluded because of poor quality of MR images. Two patients were excluded because they underwent surgery before the MR examination. In addition, two patients were excluded because of the preoperative neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Four patients were excluded as the pathological results of histopathologic grade were inaccessible. Ultimately, 58 patients (59.3 ± 10.2 years, male:33, female: 25) were included for subsequent analysis. Of the 58 patients, 11 were classified as WHO G1, 29 were classified as WHO G2, and 18 patients were classified as WHO G3. The clinical data of 58 patients are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients characteristics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 59.3 ± 10.2, (min: 40, max: 79) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 33 |

| Female | 25 |

| Histopathological grade | 1–4 |

| WHO-G1 | 11 |

| WHO-G2 | 29 |

| WHO-G3 | 18 |

| Low grade (G1 and G2) | 40 |

| High grade (G3) | 18 |

| T stage | |

| T1 | 2 |

| T2 | 4 |

| T3 | 34 |

| T4 | 18 |

| N stage | |

| N0 | 12 |

| N1 | 28 |

| N2 | 18 |

| M stage | |

| M0 | 53 |

| M1 | 5 |

| Anatomic distribution | |

| Upper | 17 |

| Middle | 28 |

| Lower | 13 |

3.1. Correlations between the DWI-Derived Parameters and Histopathologic Grade

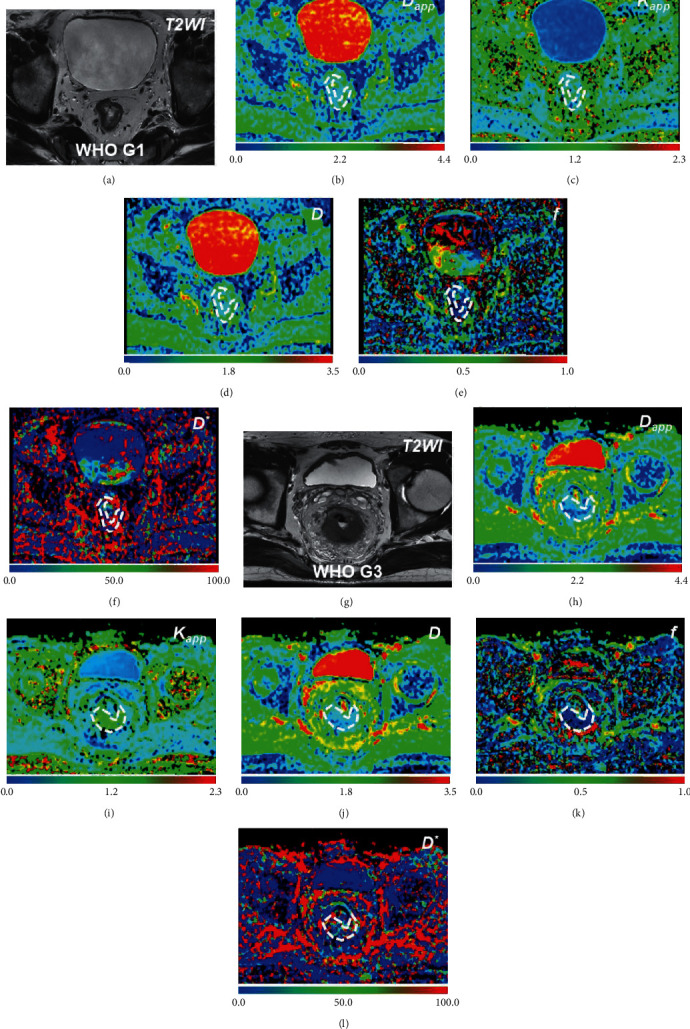

Representative MR images of a patient with WHO G1 rectal cancer and a patient with WHO G3 rectal cancer are displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

MR images of patients with surgically proven rectal cancer of WHO G1 (a–f) and WHO G3 (g–l). A patient of WHO G1 rectal cancer: (a) T2-weighted image, (b) Dapp image, (c) Kapp image, (d) D image, (e) f image, and (f) D∗ image. A patient of WHO G3 rectal cancer: (g) T2-weighted image, (h) Dapp image, (i) Kapp image, (j) D image, (k) f image, and (l) D∗ image. Note. The unit of D D∗ and Dapp: ×10−9 m2/s; Kapp and f are unitless.

3.1.1. Individual DWI-Derived Parameters

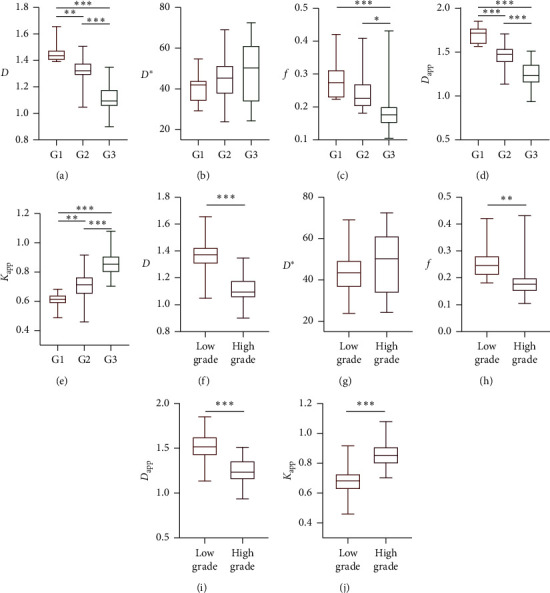

The results of directly grading rectal cancer patients by individual DWI parameters including D and Dapp (cellularity), D∗ and f (vascularity), and Kapp (microstructural complexity) are presented in Figure 2 via boxplots. All quantitative parameters except D∗ showed the capability of discriminating between rectal patients of different grades with significant difference (p < 0.05). As the histopathologic grade increased, D (G1: 1.465 ± 0.081, G2: 1.323 ± 0.105, G3: 1.105 ± 0.103, low grade (G1 and G2): 1.362 ± 0.117 and high grade (G3): 1.105 ± 0.103. Unit: ×10−9 m2/s), Dapp (G1: 1.699 ± 0.099, G2: 1.460 ± 0.127, G3: 1.250 ± 0.144 low grade: 1.526 ± 0.161 and high grade: 1.250 ± 0.144. Unit: ×10−9 m2/s), and f (G1: 0.292 ± 0.067, G2: 0.244 ± 0.052, G3: 0.192 ± 0.072, low grade: 0.257 ± 0.059 and high grade: 0.192 ± 0.072) decreased, but Kapp (G1: 0.604 ± 0.058, G2: 0.715 ± 0.091, G3: 0.862 ± 0.099, low grade: 0.684 ± 0.096 and high grade: 0.862 ± 0.099) increased. Detailed comparisons and significance levels are presented in Table 2. Interestingly, compared to others, f showed a weaker capability of grading rectal cancer as it not only displayed no significant difference between G1 and G2 (pG1 vs G2 = 0.079) but also smaller difference (pG2 vs G3 = 0.018, plow−vs. high grade = 0.002) between the subgroups compared to other parameters.

Figure 2.

Grading rectal cancer with individual DWI-derived inspiration-based parameters. (a) D value (unit: ×10−9 m2/s), (b) D∗ (unit: ×10−9 m2/s), (c) f value, (d) Dapp value (unit: ×10−9 m2/s), (e) Kapp value of WHO G1, WHO G2, and WHO G3 rectal cancer. (f) D value (unit: ×10−9 m2/s), (g) D∗ value (unit: ×10−9 m2/s), (h) f value, (i) Dapp value (unit: ×10−9 m2/s), (j) Kapp value of low-grade (WHO G1-2) and high-grade (WHO G3) rectal cancer. Note.∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001. f and Kapp is unitless.

Table 2.

Diffusion parameters among different histologic grades.

| D (×10−9 m2/s) | f | D ∗ (×10−9 m2/s) | D app (×10−9 m2/s) | K app | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All subjects (n = 58) | 1.282 ± 0.164 | 0.237 ± 0.070 | 45.458 ± 11.801 | 1.440 ± 0.201 | 0.739 ± 0.127 |

| WHO grade 1 (n = 11) | 1.465 ± 0.081 | 0.292 ± 0.067 | 40.329 ± 7.399 | 1.699 ± 0.099 | 0.604 ± 0.058 |

| WHO grade 2 (n = 29) | 1.323 ± 0.105 | 0.244 ± 0.052 | 45.622 ± 11.187 | 1.460 ± 0.127 | 0.715 ± 0.091 |

| WHO grade 3 (n = 18) | 1.105 ± 0.103 | 0.192 ± 0.072 | 48.329 ± 14.239 | 1.250 ± 0.144 | 0.862 ± 0.099 |

| Low grade (1 and 2) (n = 40) | 1.362 ± 0.117 | 0.257 ± 0.059 | 44.166 ± 10.470 | 1.526 ± 0.161 | 0.684 ± 0.096 |

| High grade (3) (n = 18) | 1.105 ± 0.103 | 0.192 ± 0.072 | 48.329 ± 14.239 | 1.250 ± 0.144 | 0.862 ± 0.099 |

| p value (grade 1 vs. grade 2) | 0.001 | 0.079 | 0.412 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| p value (grade 1 vs. grade 3) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.182 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| p value (grade 2 vs. grade 3) | <0.001 | 0.018 | 0.721 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| p value (low grade vs. high grade) | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.276 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

※ D: true diffusion coefficient, D∗: pseudodiffusion coefficient, Dapp: apparent diffusion coefficient derived from DKI, f: perfusion fraction, Kapp: apparent diffusion kurtosis coefficient.

3.1.2. Combinations of Different DWI-Derived Parameters

The first row of Figure 3 shows that 2D data spaces were constructed by different combinations of DWI-derived parameters, i.e., D and f, D and Kapp, f and Kapp, and D and f and Kapp. The results in the first row of Figure 3 demonstrate that a clearer distinction between high- and low-grade rectal cancer patients was achieved via introducing second DWI-derived biological insight with regard to a single DWI-derived biological insight. Obviously, the high-grade patients were much better separated from low-grade patients in the 3D data space when cellularity (D), vascularity (f), and microstructural complexity (Kapp) were simultaneously integrated with small data overlap.

Figure 3.

Discriminating the high-grade rectal cancer from low-grade rectal cancer patients in 2D data spaces constructed by the combination of different DWI-derived biological inspirations (first row: D (cellularity) and f (vascularity), D (cellularity) and Kapp (microstructural complexity) and f (vascularity) and Kapp (microstructural complexity) and 3D space constructed by all DWI-derived inspirations (second row: D (cellularity) and f (vascularity) and Kapp (microstructural complexity)). Note. Each point in the figure represents a patient with rectal cancer.

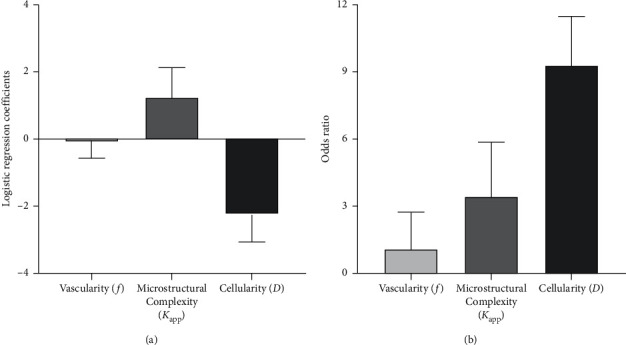

3.2. Screening the Most Sensitive DWI-Derived Biological Insight for Grading Rectal Cancer

A binary logistic regression model was established by introducing three variables: D, f, and Kapp. The standardized regression coefficients (β) of different DWI-derived biological inspirations are presented in Figure 4(a) (βcellularity = −2.235 ± 0.806, βvascularity = −0.081 ± 0.527, and βmicrostructural complexity = 1.238 ± 0.905). The odds ratios (OR) of different DWI-derived biological insight are presented in Figure 4(b) (ORcellularity = 9.350 ± 2.239, ORvascularity = 1.084 ± 1.694, and ORmicrostructural complexity = 3.440 ± 2.472). The OR of microstructural complexity was 3.440, indicating that when Kapp increased by one standard unit, the probability of high-grade rectal cancer was 3.440 times as high as before. The odds ratio of cellularity was 9.350, indicating when D decreased by one standard unit, the probability of high-grade rectal cancer was 9.350 times as high as before. It should be noted that the definition of ORcellularity and ORvascularity was different from the standard definition of OR. Detailed definitions can be found in the Section 2.

Figure 4.

Screening of the most sensitive DWI-derived biological insight from cellularity, vascularity, and microstructural complexity. (a) The standardized logistic regression coefficient of vascularity f, microstructural complexity (Kapp), and cellularity D. (b) Odds ratios of vascularity f, microstructural complexity (Kapp), and cellularity D. Notes: (1) the odds ratio of microstructural complexity (Kapp) is 3.440, indicating when Kapp increases by one unit, the probability of suffering from high-grade rectal cancer is as 3.440 times high as before. (2) The odds ratio of cellularity D was 9.350, indicating that when D decreased by one standard unit, the probability of suffering from high-grade rectal cancer was as 9.350 times high as before.

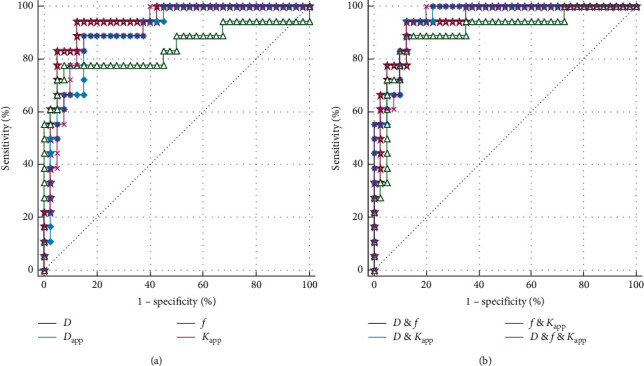

3.3. Diagnostic Performance Evaluation

Figure 5 demonstrates the diagnostic performance of different parameters and their combinations. The area under curve (AUC) and other indexes are listed in Table 3. Briefly, the following AUCs are listed in order from large to small: AUC D (cellularity) & f (vascularity) & Kapp (microstructural complexity) = 0.953, AUC D (cellularity) &Kapp (microstructural complexity) = 0.951, AUC D (cellularity) & f (vascularity) = 0.946, AUC D (cellularity) = 0.912, AUC Kapp (microstructural complexity) = 0.910, AUC f (vascularity) & Kapp (microstructural complexity) = 0.901, AUCDapp (cellularity) = 0.901, and AUC f (vascularity) = 0.843. All the abovementioned AUCs were significantly different from the AUC of 0.500 (p < 0.001).

Figure 5.

Diagnostic performance evaluation. (a) Diagnosis of high-grade rectal cancer with single DWI-derived biological insight-based parameters including cellularity (D and Dapp) and vascularity f together with microstructural complexity (Kapp). (b) Diagnosis of high-grade rectal cancer with the combinations of different DWI inspirations including cellularity and vascularity (D and f, cellularity and microstructural complexity (D and Kapp), vascularity and microstructural complexity (f and Kapp), and cellularity and vascularity and microstructural complexity (D and f and Kapp).

Table 3.

ROC analysis results of different DWI inspirations and their combinations.

| Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | AUC | Youden Index | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | 94.4 | 87.5 | 0.912 | 0.819 |

| f | 77.8 | 92.5 | 0.843 | 0.703 |

| D app | 88.9 | 85.0 | 0.901 | 0.739 |

| K app | 88.9 | 85.0 | 0.910 | 0.739 |

| D and f | 94.4 | 87.5 | 0.946 | 0.819 |

| D and Kapp | 94.4 | 87.5 | 0.951 | 0.819 |

| f and Kapp | 88.9 | 87.5 | 0.901 | 0.764 |

| D and f and Kapp | 94.4 | 87.5 | 0.953 | 0.819 |

※ D: true diffusion coefficient, D∗: pseudodiffusion coefficient, Dapp: apparent diffusion coefficient derived from DKI, f: perfusion fraction, Kapp: apparent diffusion kurtosis coefficient.

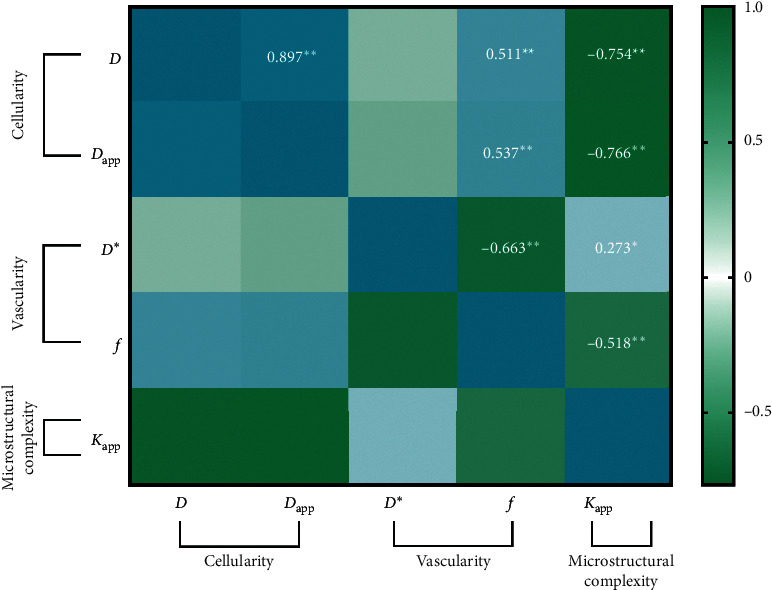

3.4. Exploring the Correlation between Different DWI-Derived Biological Inspirations

The binary correlations between different DWI-derived biological inspirations were evaluated via Pearson correlation coefficients abbreviated as r, which are presented in Figure 6. D or Dapp were significantly and positively correlated with f (rD & f = 0.511,p < 0.01;rDapp & f = 0.537,p < 0.01) but negatively correlated with Kapp (rD & Kapp = −0.754,p < 0.01; rDapp & Kapp = −0.766,p < 0.01). Besides, f was negatively correlated with Kapp (rf & Kapp = −0.518,p < 0.01). Interestingly, only f and Kapp showed significant correlations with D∗ (rD∗& f = −0.663,p < 0.01;rD∗& Kapp = 0.273, p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Heat map depicting the Pearson correlation between cellularity characterized by D and Dapp and vascularity characterized by D∗ and f, as well as microstructural complexity characterized by Kapp. Notes. The numbers represent the Pearson coefficient. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

In comparison to plenty of previous studies that simultaneously combined many DWI models but focused more on comparing the clinical effectiveness of different parameters that were calculated from various DWI models such as ADC, f, and D for tumor grading, staging, and so on, important highlights of this research are the followings: (1) combining DWI models according to their biological inspirations will benefit the accurate grading of rectal cancer via more comprehensive tumor characterization. (2) The combination of DKI and IVIM was enough to provide three main DWI-derived biological inspirations, which can avoid the disadvantages caused by excessive DWI models such as long scan time, difficult postprocessing and manipulation, and low patient compliance. (3) The results of the present research suggest that all three DWI-derived biological inspirations are tightly correlated with each other, which further proved the necessity of combining these DWI-derived inspirations together. (4) The results indicate that DWI-derived cellularity was the most sensitive for grading rectal cancer followed by microstructural complexity and vascularity.

For individual parameters, individual DWI-derived biological insight-based parameters except D∗ all had the capability of distinguishing the high-grade from low-grade rectal cancer. The biological basis is as follows: (1) The rapid proliferation of cancer cells leads to an increase in nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio and to a decrease in extracellular space, which ultimately results in an increase in the degree of diffusion restriction reflected by a decrease of diffusion coefficient (Dapp and D) [18]. (2) Differently, as the histopathologic grade increases, the extent to which the diffuse water molecules deviate from the Gaussian distribution increases, which can be quantified by the increase in the kurtosis coefficient (Kapp) [19]. (3) f decreased as histopathological grade increased was because of the following reasons: the vascular systems will be severely destroyed together with the macromanifestations such as intratumoral bleeding as tumor proliferates, which resulted in the decrease of f representing the perfusion fraction [20]. Based on the aforementioned points, (1) cellularity-, vascularity-, and microstructural complexity-related parameters had the capability for grading rectal cancer. (2) There were significant negative correlations between cellularity-related parameters (D and Dapp) and microstructural complexity-related parameter (Kapp), as well as vascularity-related parameters (f) and microstructural complexity-related parameter (Kapp). Moreover, cellularity-related parameters (D and Dapp) significantly and positively correlated with the vascularity-related parameter (f). Interestingly, IVIM-derived D∗ displayed a negative correlation with f but a positive correlation with Kapp, which can be explained by the following points: (1) according to IVIM theory, D∗ is influenced by the several factors that can be expressed as the following equation: D∗=(l × v)/6, where l represents the capillary length and v represents the average velocity of blood in the capillary. (2) As mentioned above, the poor structure of lumenized vessels dominates in high-grade rectal cancer. However, in order to meet the rapidly growing need of oxygen and nutrients for the tumor cells, the average velocity of blood in the capillary will increase compensatively. Therefore, D∗ was significantly positively correlated with Kapp but negatively with f. Correlations among DWI-derived cellularity, vascularity, and microstructural complexity further proved the necessity of integrating these inspirations together to achieve a more comprehensive tumor characterization. In addition, the vascularity-related f showed the weaker diagnostic power compared to cellularity- and microstructural complexity-related parameters. These results can be explained as follows: (1) D∗ is very vulnerable to the effects of a low signal to noise ratio. (2) The vascularity variation is not as sensitive as cellularity and microstructural complexity during carcinogenesis. (3) Several studies proposed that f is not accurate for diagnosing tumor. [17] When different DWI-derived parameters were combined, a better separation of high-grade from low-grade rectal cancer was achieved with less overlap between groups. The causes for abovementioned results were speculated as that more DWI parameters meant a more comprehensive characterization of the tumor, which ultimately led to a better separation in 3D data space via combining different DWI-derived biological inspirations. The ROC analysis results indicated that, among all the parameters and their combinations, the best diagnostic (AUC = 0.953) performance was achieved when all three DWI-derived biological inspirations were simultaneously integrated. Moreover, in general, the diagnostic performance of the combination of two DWI-derived inspiration-based parameters was better than that of single DWI-derived insight-based parameter. As mentioned above, the more the DWI-derived inspirations, the more comprehensive the characterization of rectal cancer, which ultimately resulted in the better diagnostic performance for grading rectal cancer.

The binary logistic regression analysis results demonstrated that cellularity quantified by IVIM-derived D was the most sensitive for predicting high-grade rectal cancer, followed by microstructural complexity quantified by DKI-derived Kapp and vascularity quantified by IVIM-derived f. The abovementioned results are consistent with the ROC analysis results. The reasons may be the following: (1) Among cellularity, vascularity, and microstructural complexity, the cellularity variation is the most pronounced. Similar to the results of our study, Fujima demonstrated that D (25th percentile) served as the most powerful indicator for predicting the treatment outcome of nasal or sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma patients. [21] It was reported by Shirato et al. that the D value obtained from IVIM showed a higher value in discriminating distant metastasis compared to the parameters derived from DKI [22]. (2) Some previous studies proposed that f, representing the vascularity, is not accurate enough, always leading to mixed results [17, 20, 23]. Interestingly, other researchers have drawn different conclusions. Different from our study, Wang et al. concluded that Kapp is the most valuable diagnostic marker for grading glioma in comparison to the other parameters [13]. Similarly, Zhu's research concluded that Kapp is much more effective in grading and evaluating the proliferation of diffuse astrocytic tumors [12]. We believe the major causes for the abovementioned inconsistency are the following: (1) there are huge physiological, pathological, and biological differences among various cancer types, specific pathologic processes, and so on which researchers focused on in their projects. (2) The selection of b values is significant for accurate fitting of the diffusion model, which further determines the calculation of parameters. (3) Data analysis can also contribute to the variance of conclusion. For instance, data analysis of hybrid IVIM-DKI is quite different from separate analysis of DKI and IVIM [22]. (4) Other potential factors include the number and distribution of patients.

There were several limitations in the present study. First, the sample size of patients was not large enough, and the number of patients was unbalanced in different histological grades. Particularly, the number of patients with WHO G1 rectal cancer is not enough. Second, the diagnosis was only applied, referring to the WHO criteria in the present study. However, other grading standards such as the poorly differentiated clusters called PDCs-based grading were not referred to further evaluate the diagnostic performance. Third, merely, the logistic regression was introduced to explore the integration of different DWI inspirations. Other complex statistical models should be introduced in the following work. Fourth, too large tumor may make it difficult to determine the tumor boundary and ultimately affect the accurate calculation of DWI-derived parameters.

In conclusion, this research indicates that greater diagnostic performance for grading rectal cancer can be obtained through integrating the DWI-derived cellularity, vascularity, and microstructural complexity quantified by parameters that were sourced from DKI and IVIM. Furthermore, because there were tight correlations among all DWI-derived biological inspirations, the integration of different biological inspirations of DWI holds great potential in achieving a more comprehensive tumor characterization, which will be meaningful for many other clinical applications including cancer treatment evaluation, tumor detection, and tumor recurrence prediction.

Contributor Information

Hui Li, Email: lihuisysuu@outlook.com.

Chuanmiao Xie, Email: xchuanm@sysucc.org.cn.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are incorporated within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Zhijun Geng and Yunfei Zhang contributed equally.

References

- 1.Bray F., Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Siegel R. L., Torre L. A., Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu L., Pan Z., Ma Q., et al. Diffusion kurtosis imaging study of rectal adenocarcinoma associated with histopathologic prognostic factors: preliminary findings. Radiology. 2017;284(1):66–76. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016160094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zdenko B., Goran K., Vladimir S., Zeljko B., Rudika G., Tomislav I. Prognostic factors of local recurrence and survival after curative rectal cancer surgery: a single institution experience. Collegium Antropologicum. 2012;36(4):1355–1361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canda A. E., Terzi C., Gorken I. B., Oztop I., Sokmen S., Fuzun M. Effects of preoperative chemoradiotherapy on anal sphincter functions and quality of life in rectal cancer patients. International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 2010;25(2):197–204. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0807-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le Bihan D., Breton E., Lallemand D., Grenier P., Cabanis E., Laval-Jeantet M. MR imaging of intravoxel incoherent motions: application to diffusion and perfusion in neurologic disorders. Radiology. 1986;161(2):401–407. doi: 10.1148/radiology.161.2.3763909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu H., Jensen J. H., Ramani A., Helpern J. A. Three-dimensional characterization of non-Gaussian water diffusion in humans using diffusion kurtosis imaging. NMR in Biomedicine. 2006;19(2):236–247. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sui Y., Wang H., Liu G., et al. Differentiation of low- and high-grade pediatric brain tumors with highb-value diffusion-weighted MR imaging and a fractional order calculus model. Radiology. 2015;277(2):489–496. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015142156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White N. S., Leergaard T. B., D’Arceuil H., Bjaalie J. G., Dale A. M. Probing tissue microstructure with restriction spectrum imaging: histological and theoretical validation. Human Brain Mapping. 2013;34(2):327–346. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang L., Zhou X. J. Diffusion MRI of cancer: from low to high b-values. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2019;49(1):23–40. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jing Y., Yeung D. K. W., Mok G. S. P., et al. Non-Gaussian analysis of diffusion weighted imaging in head and neck at 3T: a pilot study in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Plos One. 2014;9(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087024.e87024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chakhoyan A., Woodworth D. C., Harris R. J., et al. Mono-exponential, diffusion kurtosis and stretched exponential diffusion MR imaging response to chemoradiation in newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 2018;139(3):651–659. doi: 10.1007/s11060-018-2910-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J., Chen X., Chen D., Wang Z., Li S., Zhu W. Grading and proliferation assessment of diffuse astrocytic tumors with monoexponential, biexponential, and stretched-exponential diffusion-weighted imaging and diffusion kurtosis imaging. European Journal of Radiology. 2018;109:188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bai Y., Lin Y., Tian J., et al. Grading of gliomas by using monoexponential, biexponential, and stretched exponential diffusion-weighted MR imaging and diffusion kurtosis MR imaging. Radiology. 2016;278(2):496–504. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015142173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li C., Chen M., Wan B., et al. A comparative study of Gaussian and non-Gaussian diffusion models for differential diagnosis of prostate cancer with in-bore transrectal MR-guided biopsy as a pathological reference. Acta Radiologica. 2018;59(11):1395–1402. doi: 10.1177/0284185118760961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun K., Chen X., Chai W., et al. Breast cancer: diffusion kurtosis MR imaging-diagnostic accuracy and correlation with clinical-pathologic factors. Radiology. 2015;277(1):46–55. doi: 10.1148/radiol.15141625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bosman F. T. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woo S., Lee J. M., Yoon J. H., Joo I., Han J. K., Choi B. I. Intravoxel incoherent motion diffusion-weighted MR imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma: correlation with enhancement degree and histologic grade. Radiology. 2013;270(3):758–767. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Surov A., Meyer H. J., Höhn A.-K., et al. Correlations between intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) parameters and histological findings in rectal cancer: preliminary results. Oncotarget. 2017;8(13):21974–21983. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui Y., Yang X., Du X., Zhuo Z., Xin L., Cheng X. Whole-tumour diffusion kurtosis MR imaging histogram analysis of rectal adenocarcinoma: correlation with clinical pathologic prognostic factors. European Radiology. 2018;28(4):1485–1494. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5094-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shan Q., Chen J., Zhang T., et al. Evaluating histologic differentiation of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma using intravoxel incoherent motion and AFP levels alone and in combination. Abdominal Radiology. 2017;42(8):2079–2088. doi: 10.1007/s00261-017-1107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujima N., Yoshida D., Sakashita T., et al. Prediction of the treatment outcome using intravoxel incoherent motion and diffusional kurtosis imaging in nasal or sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma patients. European Radiology. 2016;27(3):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4440-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujima N., Sakashita T., Homma A., Yoshida D., Kudo K., Shirato H. Utility of a hybrid IVIM-DKI model to predict the development of distant metastasis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients. Magnetic Resonance in Medical Sciences. 2018;17(1):21–27. doi: 10.2463/mrms.mp.2016-0136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei Y., Gao F., Zheng D., et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the setting of HBV-related cirrhosis: differentiation with hepatocellular carcinoma by using Intravoxel incoherent motion diffusion-weighted MR imaging. Oncotarget. 2018;9(8):7975–7983. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are incorporated within the article.