Abstract

Prior research on alcohol and the immune system has tended to focus on binge doses or chronic heavy drinking. The aim of this single-session preliminary study was to characterize immune response to moderate alcohol (0.60 g alcohol per kilogram body weight) in healthy, nonchronic drinkers. The sample (N = 11) averaged 26.6 years of age and was balanced in gender. Plasma samples were collected at baseline and 1, 2 and 3 hours postconsumption. Markers of microbial translocation [lipopolysaccharide (LPS)] and innate immune response [LPS-binding protein (LBP), soluble cluster of differentiation 14 (sCD14), and selected cytokines] were measured using immunoassays. Participants completed self-report questionnaires on subjective alcohol response and craving. Linear mixed models were used to assess changes in biomarkers and self-report measures. Breath alcohol concentration peaked at 0.069 ± 0.008% 1 hour postconsumption. LPS showed a significant linear decrease. LBP and sCD14 showed significant, nonlinear (U-shaped) trajectories wherein levels decreased at 1 hour then rebounded by 3 hours. Of nine cytokines tested, only MCP-1 and IL-8 were detectable in ≥50% of samples. IL-8 did not change significantly. MCP-1 showed a significant linear decrease and also accounted for significant variance in alcohol craving, with higher levels associated with stronger craving. Results offer novel evidence on acute immune response to moderate alcohol. Changes in LBP and sCD14, relative to LPS, may reflect their role in LPS clearance. Results also support further investigation into the role of MCP-1 in alcohol craving. Limitations include small sample size and lack of a placebo condition.

INTRODUCTION

Microbial translocation, i.e. the unphysiological movement of gut microbes into systemic circulation, is a source of chronic immune activation and inflammation in numerous diseases (Brenchley and Douek, 2012). Alcohol can promote microbial translocation by disrupting epithelial integrity and inducing gut dysbiosis (Bull-Otterson et al., 2013; Canesso et al., 2014; Leclercq et al., 2012; Mutlu et al., 2012; Yan et al., 2011). Chronic alcohol exposure disrupts microbiome composition and is associated with liver injury (Szabo and Bala, 2010). As prior research has tended to focus on effects of heavy and/or chronic alcohol exposure, this preliminary study examined acute effects of a moderate alcohol dose on markers of microbial translocation and innate immune activation in healthy moderate drinkers.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS, also termed endotoxin) is found in the outer cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria and is widely used as a marker of microbial translocation. Monocytes and macrophages express toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) for LPS recognition (Park and Lee, 2013). LPS binding protein (LBP) and soluble cluster of differentiation 14 (sCD14) are acute phase response proteins involved in detection of and response to LPS (Pugin et al., 1993). LBP binds to LPS, presenting it to membrane-bound CD14 or sCD14, which then transfers LPS to the MD2/TLR4 complex. In a concentration-dependent manner, sCD14 and LBP regulate immune response by modulating the frequency of interaction between LPS and MD2/TLR4 (Kitchens and Thompson, 2005). A dynamic equilibrium is established as LPS is transferred continuously between membrane-bound CD14 and sCD14. LBP and sCD14 facilitate transfer of LPS to plasma lipoproteins, which shuttle LPS to the liver for neutralization and excretion (Kitchens et al., 2001; Levels et al., 2005; Wurfel et al., 1995; Yao et al., 2016). If not diverted, LPS stimulation of TLR4 triggers downstream proliferation of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

LPS, LBP and sCD14 are important markers of alcohol’s systemic immune effects (Bala et al., 2014; Liangpunsakul et al., 2017). In previous studies, administering binge doses of alcohol (i.e. blood alcohol level ≥ 0.08 g/dl) to healthy individuals caused immediate elevations in LPS, sCD14 and LBP levels and enhanced immune response to LPS or Escherichia coli stimulation (Afshar et al., 2015; Bala et al., 2014; Stadlbauer et al., 2019). Notably, LPS levels and immune sensitivity decreased below baseline at several hours to 1 day after consumption, indicating a biphasic response pattern (Afshar et al., 2015; Bala et al., 2014). However, other studies have reported no significant change in LPS, LBP or sCD14 after a binge dose of alcohol, even though other immune parameters were affected (de Jong et al., 2015; Stadlbauer et al., 2019).

Despite mixed findings, previous research clearly demonstrates that binge doses of alcohol acutely modulate immune function. The acute immunomodulatory effects of moderate (sub-binge) doses are less studied yet important to understand, as most alcohol users do not regularly exceed binge thresholds (NIAAA, 2018). This preliminary study examined changes in markers of microbial translocation (LPS) and immune activation (LBP, sCD14 and selected cytokines) after moderate alcohol consumption (target blood alcohol = 0.07 g/dl) in healthy adults. Plasma samples were collected at prealcohol baseline and at 1, 2 and 3 hours after alcohol administration. Based on previous research, we predicted that LPS, LBP and sCD14 would increase within 1 hour and remain elevated.

In addition to LPS and its acute phase reactants, we quantified selected cytokines (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17A, MCP-1, TNF-α) following previous reports that these signaling proteins are induced by alcohol, are correlated with alcohol-related inflammation, and under some circumstances may play a role in promoting alcohol consumption (Bjorkhaug et al., 2020; Blednov et al., 2005; Gyongyosi et al., 2019; He and Crews, 2008; Hritz et al., 2008; Laso et al., 1998; Leclercq et al., 2014; Pascual et al., 2017; Tilg et al., 2016; Tung et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2020). Many of these cytokines have been implicated in alcohol craving and/or alcohol-seeking behavior, including IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, MCP-1 and TNF-α (Leclercq et al., 2012; Leclercq et al., 2014; Marshall et al., 2017). It is theorized that systemic inflammation, via inflammatory cytokine pathways, may promote neuroinflammation and associated behavioral dysregulation, including problematic alcohol use (Leclercq et al., 2017). Concentrations of cytokines were expected to reflect transient immune inhibition by the end of the observation period (Afshar et al., 2015; Barr et al., 2016). Given research linking immune signaling to alcohol consumption and craving (Blednov et al., 2012; Leclercq et al., 2012; Milivojevic et al., 2017), we also tested associations between biomarkers and alcohol craving.

METHOD

Participants

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from the Providence, RI, USA, community via flyers and digital bulletin boards. Potential participants were prescreened by phone, and eligible individuals attended an in-person screening. The sample was a subset of participants from Monnig et al. (2019), which reported data from a different part of the protocol.

Screening

At screening, data were collected on participants’ vital functions, medical history, psychiatric symptoms, and demographics. Breath alcohol concentration (BrAC) of zero was established prior to study procedures. Urine was tested for drug metabolites (RediTest Alere iCup®) and pregnancy hormones for females. Substance use in the previous 90 days was assessed using the Timeline Followback Interview (Sobell, 1992). The Institutional Review Board of Brown University approved all study procedures, and participants gave written informed consent.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria were: (a) 21–45 years of age; (b) able to speak and read English at eighth grade level or higher; (c) self-reported alcohol use ≥0.60 g/kg at least once in the past year, to reduce risk of adverse response to alcohol; (d) self-reported alcohol use at least once per month for the past 6 months; (e) body mass index of 18.5–30 kg/m2; (f) right-handed, due to requirements of an MRI study component reported elsewhere (Monnig et al., 2019). Exclusion criteria were: (a) lifetime history of heavy drinking (i.e. monthly or more frequent heavy drinking episodes for a period of 6 months or more); (b) more than three heavy drinking episodes (≥4 drinks for women, ≥5 drinks for men) in the past 90 days (Dawson, 2011); (c) currently seeking or ever having sought treatment or attended a mutual help group (e.g. Alcoholics Anonymous) for alcohol/drug use, with the exception of smoking cessation; (d) chronic disease requiring use of medication; (e) antibiotic use or probiotic use in the past 6 months; (f) daily or near-daily use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; (g) chronic gastrointestinal disorder; (h) positive urine toxicology for amphetamine, methamphetamine, cocaine, opioids, or benzodiazepines or self-reported use of any of these drugs in past 30 days; (i) positive screening for past 12-month drug use disorder per Drug Abuse Screening Test score > 2 (Skinner, 1982); (j) current major psychiatric disorder or clinically significant suicidality; (k) history of fainting, weakness, infection or psychological distress resulting from standard blood draw; (l) safety contraindication for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan (e.g. metal implant, claustrophobia); (m) inability to abstain from tobacco use for 11 hours (i.e. before and during study sessions); (n) inability to abstain from cannabis use for 48 hours prior to sessions; (o) for females, currently pregnant, nursing or not using effective birth control if applicable. Some eligibility criteria (e.g. MRI compatibility) pertain to study elements reported previously (Monnig et al., 2019).

Alcohol administration

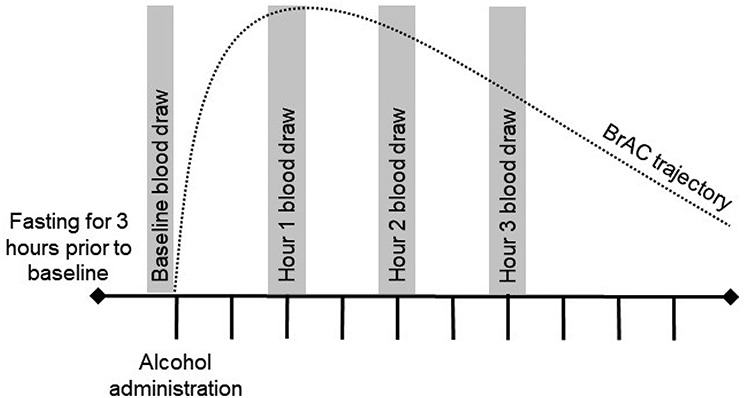

This study used a single session, within-subjects design in which all participants received a moderate dose of alcohol. An overview of procedures is shown in Fig. 1. Blood samples (see below) were collected prior to alcohol and at 1, 2 and 3 hours after the start of drinking. The first blood sample was collected between 11:15 a.m. and 12:45 p.m., and alcohol administration commenced between 11:30 a.m. and 1 p.m. Participants were told to abstain from alcohol for 48 hours prior to the session and to fast (except for water as needed) for 3 hours prior to beverage administration. A moderate dose of alcohol (0.60 g alcohol per kilogram of body weight, reduced by 13% for females) was administered for a target peak blood alcohol level of 0.07 g/dl. Alcohol was given as vodka mixed with unsweetened lime seltzer in a total volume of 500 ml. This beverage was served in two doses spaced 5 minutes apart. Participants were asked to consume each dose within 1 minute. This procedure has been shown to increase blood alcohol at a rate of 0.001 g/dl/min (Fillmore and Vogel-Sprott, 1998). An evidential-grade digital handheld breath analyzer (Alco-Sensor® IV), tested monthly using gas standards to ensure accuracy, was used to assess BrAC at half-hour intervals. BrAC readings from the Alco-Sensor® IV correlate with blood alcohol level at r = 0.94 (Zuba, 2008). Participants were allowed water as needed throughout the session and were given a meal at the end of blood sample collection. Transportation home was provided once data collection was completed and BrAC was <0.020%.

Fig. 1.

Study overview, overview of study procedures; tick marks represent half-hour intervals; BrAC, breath alcohol concentration.

Measurement of alcohol craving and subjective effects

Participants completed a visual analog scale to rate alcohol craving (Amlung et al., 2015) at 1, 2 and 3 hours after alcohol administration. Participants responded to the question, ‘How strong is your desire for another drink right now?’ by placing a mark through a line with the anchors not at all (0 mm) and very much (100 mm). The rating (0–100 mm) was used as the measure of craving.

Participants completed the Brief Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale (B-BAES) (Rueger and King, 2013) prior to alcohol administration (baseline) and 30, 60, 90, 120, 150 and 180 minutes afterward. This scale measures the acute stimulating and sedating effects of alcohol. Participants rated the extent to which six words described their feelings at the moment (stimulation subscale: energized, excited, up; sedation subscale: sedated, slow thoughts, sluggish). Ratings ranged from 0 = not at all to 10 = extremely. The brief measure (Rueger and King, 2013) is a shortened form of the 14-item Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale (Martin et al., 1993).

Biomarker collection and analysis

Blood samples were collected into BD Vacutainer EDTA tubes at prealcohol baseline and at 1, 2 and 3 hours after alcohol administration. Samples for one participant were not taken following the baseline draw due to technical issues with the venipuncture equipment. Samples were processed to plasma and stored in endotoxin-free cryovials at −80°C until assayed in a single batch. LPS was quantified using an enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Lifespan Biosciences). LBP, sCD14, interleukin 1 alpha (IL-1α), interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin 6 (IL-6), interleukin 8 (IL-8), interleukin 1 (IL-10), interleukin 12 p70 (IL-12 p70), interleukin 17A (IL-17A), monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) were quantified using multiplex assays (R&D Systems) on the Luminex platform. After finding that most cytokines were below the lower limit of detection on the multiplex assay, additional high-sensitivity ELISAs (Thermo Fisher Scientific Invitrogen) were performed for IL-8 and TNF-α. All assays were performed in duplicate, and results with coefficient of variation >20% were excluded from analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were not performed on cytokines with ≥50% undetectable concentrations. Linear mixed models in SPSS v.24 were used to assess change in detectable biomarkers (with exception of MCP-1, see below) as a function of time from baseline through the 3 hourly postalcohol measurements. Similarly, linear mixed models were used to test change in subjective measures (sedation, stimulation and craving) as a function of time. Eleven participants were included in LPS and MCP-1 analyses, and 10 participants were included in sCD14, LBP and IL-8 analyses. LPS, LBP and sCD14 were log-transformed prior to analyses to reduce non-normality related to positive skew. Linear mixed models accounted for correlation among repeated measures within participants. Models were specified with participant as the subject variable and hour (i.e. baseline, 1, 2, and 3 hour) as the repeated measure. Maximum likelihood was used as the estimation method, as it is able to handle missing data points without excluding cases listwise or imputing data (Baraldi and Enders, 2010). Because visual inspection of plots for LBP and sCD14 data clearly showed nonlinear change (i.e. U-shaped curves), we tested models that included a quadratic effect of time for these outcomes. Change in MCP-1 was tested in a Tobit (i.e. censored) regression framework, as 41% of sample values were below the limit of detection. The regression analysis on MCP-1 was performed in Mplus v.7 using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors. For models that showed a significant effect of time, follow-up pairwise tests were performed to determine which time points differed.

Hierarchical linear regression models were used to test whether biomarkers significantly increased prediction of craving scores beyond BrAC and the B-BAES stimulation subscale. BrAC and subjective stimulation were included as predictors in the first step to account for physiological intoxication and reinforcing properties of alcohol, respectively. All predictors were measured at peak BrAC, which occurred at 1 hour. Craving at Hour 3 was used as the dependent variable so that the predictors temporally preceded the outcome. Moreover, craving during descending BrAC is theoretically relevant to the development of problem drinking. The F-test for the R2 change when the biomarker was added in the second step, referred to as the F-change, indicated whether the addition of the biomarker significantly improved prediction of craving at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1A. Participants were young adults [age (mean ± standard deviation) = 26.6 ± 3.0 years; six female, five male] who reported moderate alcohol intake of 3.3 ± 1.9 average drinks per week. Baseline biomarker concentrations are presented in Table 1B. Concentrations of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12 p70, IL-17A and TNF-α were below lower limits of detection in >97% of samples and were not analyzed further.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics and baseline biomarker values

| Participant characteristics (N = 11) | Mean ± standard deviation or count |

|---|---|

| A. Participant characteristics | |

| Age (years) | 26.6 ± 3.0 |

| Sex | 6 Female |

| 5 Male | |

| Race | 1 African American/Black |

| 1 Asian | |

| 9 White | |

| Average drinks per week | 3.3 ± 1.9 |

| Percent drinking days | 27.4 ± 19.2 |

| Average drinks per drinking day | 1.9 ± 0.5 |

| Smoker | 0 |

| B. Baseline biomarker values | |

| Baseline biomarker values | Median (interquartile range) |

| IL-8 (pg/ml) | 0.51 (0.41–1.03) |

| LBP (ng/ml) | 8311 (5208–17705) |

| LPS (pg/ml) | 12 (8–22) |

| MCP-1 (pg/ml) | 74 (63–115) |

| sCD14 (ng/ml) | 1626 (1210–3417) |

Notes: Percentages of samples outside the acceptable coefficient of variation range were as follows: 8% for IL-8, 12% for LBP, 5% for LPS, 0% for MCP-1 and 12% for sCD14. The majority of samples (>97%) had concentrations of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12 p70, IL-17A and TNF-α that were below the lower limit of detection.

BrAC

BrAC was verified to be 0.000% at baseline. At 1 hour, BrAC peaked at 0.069 ± 0.008%. BrAC subsequently decreased to 0.059 ± 0.009% at 2 hours and 0.046 ± 0.009% at 3 hours. In sum, BrAC followed the expected trajectory and showed minor interindividual variability.

Change in biomarkers

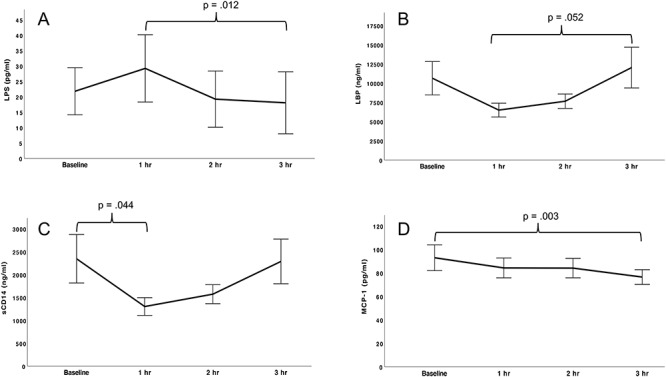

Parameter estimates for linear mixed models testing changes in biomarkers are shown in Table 2. The linear effect of time on LPS levels was significant, F(1,29.206) = 5.307, P = 0.029. LPS showed a small initial increase followed by a decrease during the 3-hour test period (Fig. 2A). Pairwise tests showed that LPS values differed significantly at Hour 1 versus Hour 3 (P = 0.012). For LBP, there was a significant linear effect of hour, F(1,26.609) = 7.806, P = 0.010, and a significant quadratic effect of hour, F(1,26.609) = 10.632, P = 0.003. The linear effect of hour was negative, whereas the quadratic effect of hour was positive. The combination of a negative linear effect with positive quadratic effect is consistent with the U-shaped curve observed in the LBP data (Fig. 2B). On pairwise tests, LBP values differed between Hour 1 and Hour 3 at the trend level (P = 0.052). Similarly, for sCD14, there was a significant negative linear effect of hour, F(1,26.482) = 6.277, P = 0.019; and a significant positive quadratic effect of hour, F(1,26.482) = 7.202, P = 0.012. The U-shaped trajectory of the observed sCD14 values is consistent with these effects (Fig. 2C). Pairwise tests for sCD14 indicated a significant difference between baseline and Hour 1 (P = 0.044).

Table 2.

Results of biomarker analyses

| Model term | Estimate | 95% Confidence interval | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-8 | Intercept | 0.87 | 0.34, 1.40 | 0.003 |

| Hour | 0.07 | −.08, 0.22 | 0.354 | |

| LBP | Intercept | 3.95 | 3.80, 4.10 | <0.001 |

| Hour | −0.26 | −.45, −0.07 | 0.010 | |

| Hour2 | 0.10 | 0.04, 0.16 | 0.003 | |

| LPS | Intercept | 1.21 | 0.97, 1.45 | <0.001 |

| Hour | −0.08 | −0.16, −0.01 | 0.029 | |

| MCP-1 | Intercept | 82.77 | 44.03, 121.52 | <0.001 |

| Hour | −8.29 | −16.14, −0.44 | 0.007 | |

| sCD14 | Intercept | 3.28 | 3.14, 3.42 | <0.001 |

| Hour | −0.25 | −0.45, −0.04 | 0.019 | |

| Hour2 | 0.09 | 0.02, 0.15 | 0.012 |

Notes: Values for LPS, LBP and sCD14 have been log-transformed. Raw data are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Change in biomarkers following a moderate dose of alcohol; LPS, LBP, sCD14 and MCP-1 changed significantly during the 3-hour period following alcohol administration; all participants (N = 11) were included in LPS and MCP-1 analyses, and 10 participants were included in sCD14 and LBP analyses; brackets indicate time points that differed significantly (P < 0.05) or at the trend level (P = 0.05), (A) LPS showed a significant linear decrease (P = 0.029); on pairwise tests, LPS was significantly lower at Hour 3 relative to Hour 1 (P = 0.012), (B) LBP showed a significant negative linear effect (P = 0.010) and positive quadratic effect (P = 0.003), consistent with a U-shaped curve; pairwise tests indicated that LBP showed a trend toward a higher concentration at Hour 3 compared to Hour 1 (P = 0.05), (C) sCD14 showed a significant negative linear effect (P = 0.019) and positive quadratic effect (P = 0.012), consistent with a U-shaped curve; on pairwise tests, sCD14 decreased significantly from baseline to Hour 1 (P = 0.044), (D) MCP-1 showed a significant linear decrease (P = 0.007), MCP-1 at Hour 3 was significantly lower than at baseline (P = 0.003).

As noted above, the only cytokines detected in >50% of samples were IL-8 (detected in 100% of samples) and MCP-1 (detected in 59% of samples). IL-8 did not change significantly during the session. For MCP-1, the Tobit regression analysis showed a significant negative linear effect of hour (Fig. 2D). Pairwise tests found a significant difference for MCP-1 values at baseline versus Hour 3 (P = 0.003).

Subjective response to alcohol

Linear mixed models were used to examine changes in self-reported measures of alcohol response (stimulation, sedation and craving) during the session. Significant change was observed in stimulation [F(6,66) = 10.328, P < 0.001], but not sedation [F(6,66) = 1.017, P = 0.422] or craving [F(2,22) = 0.345, P = 0.712]. Compared to baseline, stimulation scores were significantly increased at 30 minutes (P < 0.001) and 1 hour (P = 0.031) and were significantly decreased at 180 minutes (P = 0.011) after alcohol consumption.

Association of biomarkers with alcohol craving

Hierarchical regression models (see Table 3) used BrAC, subjective stimulation, and biomarkers measured at peak intoxication (1 hour postconsumption) to predict alcohol craving 3 hours postconsumption. The overall model and R2-change were significant for MCP-1, indicating that addition of MCP-1 to BrAC and B-BAES stimulation score significantly increased variance accounted for in craving. Higher MCP-1 at peak intoxication predicted stronger alcohol craving at 3 hours postconsumption. Overall models and R2-change statistics were not significant for LPS, LBP, sCD14 orIL-8.

Table 3.

Regression models predicting alcohol craving from BrAC, subjective stimulation and biomarkers

| Overall model F-test | Overall model P-value | Adjusted R2 for overall model | β for biomarker | R 2-change | F-change | F-change P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-8 | 0.122 | 0.943 | −0.491 | −0.232 | 0.042 | 0.228 | 0.653 |

| LBP | 3.728 | 0.095 | 0.506 | 0.433 | 0.153 | 2.484 | 0.176 |

| LPS | 1.851 | 0.239 | 0.211 | 0.124 | 0.014 | 0.166 | 0.698 |

| MCP-1 | 12.547 | 0.005 | 0.794 | 0.738 | 0.396 | 17.291 | 0.006 |

| sCD14 | 3.201 | 0.121 | 0.452 | 0.442 | 0.120 | 1.753 | 0.243 |

Notes: The F-change is the significance test of the R2-change resulting from the addition of the biomarker in the second step of the hierarchical linear regression. A significant F-change statistic indicates that the addition of the biomarker significantly increased variance accounted for in craving score.

DISCUSSION

A moderate alcohol dose was associated with the following changes from prealcohol baseline in healthy adults: (a) a decrease in LPS, manifested as an initial increase at Hour 1 followed by a significant decrease at Hour 3; (b) quadratic (U-shaped) changes in LBP and sCD14 levels, characterized by decreases from baseline at Hours 1 and 2 followed by steep increases at Hour 3; and (c) a decrease in pro-inflammatory cytokine MCP-1. These preliminary findings are a novel contribution to the literature on acute effects of alcohol on the immune system. Based on previous studies, we expected to observe increases in LPS, sCD14 and LBP following alcohol administration. These hypotheses were informed by studies that used similar paradigms but higher alcohol doses (Afshar et al., 2015; Bala et al., 2014; de Jong et al., 2015; Stadlbauer et al., 2019). One possible explanation for our results is that acute effects of moderate alcohol on the immune system are qualitatively different from those of binge alcohol. Of course, findings must be considered preliminary given the small sample size and lack of placebo control condition.

Here a moderate alcohol dose (peak blood alcohol of 0.069 g/dl) was associated with an initial increase in blood LPS (1 hour postconsumption), followed by a significant decrease at 3 hours postconsumption. Following a higher dose of alcohol, Bala et al. (2014) observed an immediate increase in LPS, followed by a return to baseline levels at 4 hours and a significant decrease below baseline at 24 hours. In our view, it is unlikely that the decrease we observed in LPS represents a decrease in microbial translocation or an improvement in gut barrier function. Rather, a possible explanation is the bioactivity of sCD14 and LBP in LPS clearance. LBP and sCD14 were depleted 1–2 hours postconsumption and then rebounded approximately to baseline levels at 3 hours postconsumption. sCD14 may decrease in plasma as it binds LPS to divert it from TLR4, ferrying LPS to plasma lipoproteins that function to clear LPS from circulation (Yao et al., 2016). The role of LBP in the LPS response is complex, as it can both potentiate and dampen the LPS response. Like sCD14, LBP can transfer LPS to lipoproteins, may form large LPS–LBP complexes with reduced TLR4 signaling capacity, and can even divert LPS from membrane-bound CD14 (Kitchens and Thompson, 2005). In the plasma, low concentrations of LBP are associated with cell activation, whereas higher concentrations have inhibitory functions. LPS clearance also can occur via internalization of activated LPS-MD2 complexes (Plociennikowska et al., 2015). Such internalization can occur via endocytosis, micropinocytosis or phagocytosis, largely depending on cell type (Plociennikowska et al., 2015). The rebound in sCD14 and LBP observed between 1 and 3 hours postconsumption, during which LPS continued to decrease, could be interpreted as increased bioavailability of these molecules to enact acute LPS clearance. Following TLR4 stimulation, immune cells ‘shed’ CD14 as sCD14. This appears to occur via two main mechanisms: (a) proteolytic cleavage from membrane of cells such as neutrophils (Haziot et al., 1993) and monocytes (Bazil and Strominger, 1991); (b) via a protease-independent mechanism, such that CD14 can be directly secreted from the cell (Bufler et al., 1995). LBP may increase due to induction as a downstream result of TLR4 stimulation (Wan et al., 1995).

We also observed a significant decrease in MCP-1 after alcohol consumption. MCP-1 magnifies monocyte migration following TLR4 stimulation (Liu et al., 2013) and is a marker of microglial activation and neuroinflammation (Zhang et al., 2018). Consistent with our findings, a preclinical study found that acute alcohol, at a slightly higher dose than administered here, inhibited production of MCP-1, a chemokine induced by activation of the NF-κB pathway (Goebeler et al., 2001; Szabo et al., 1999). In addition, an investigation of serum cytokine levels in healthy men after a higher alcohol dose reported that MCP-1 decreased significantly at 2 hours postconsumption (Neupane et al., 2016). For cytokines other than MCP-1 and IL-8, levels were below the lower limit of detection in the majority of samples. This outcome is consistent with previous research with nonstimulated samples from healthy adults (Neupane et al., 2016) and therefore is unlikely to be due to limitations of the assays we used.

Subjective alcohol stimulation, BrAC, and MCP-1 together accounted for a high proportion of variance (adjusted R2 = 0.794) in alcohol craving. MCP-1, but not other biomarkers, accounted for significant variance in alcohol craving in this sample of moderate drinkers with no history of heavy drinking. This finding extends previous research linking pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, to alcohol craving in individuals with alcohol use disorder or problem drinking (Leclercq et al., 2012; Milivojevic et al., 2017). Chronic heavy drinking is associated with elevated MCP-1 levels in plasma (Orio et al., 2018), cerebrospinal fluid (Umhau et al., 2014) and postmortem brain tissue (He and Crews, 2008). In mice, deletion of coding genes for MCP-1 (also named CCL2) and its receptor (CCR2) reduced preference and intake of ethanol (Blednov et al., 2005). Our dual findings for MCP-1–that it decreased under acute alcohol in moderate drinkers and positively predicted subsequent alcohol craving—underscore the complexity of psychoneuroimmune response to alcohol. Due to the absence of past or current problem drinking in our sample, the association of MCP-1 levels with craving requires further investigation in clinical samples.

Limitations and strengths

This study is limited by lack of a no-alcohol control condition with which to compare the effects of moderate acute alcohol. Conducting all lab sessions at the same time of day and within a narrow timeframe (4 hours) limited the influence of diurnal variability, but we cannot rule out a possible influence of diurnal fluctuations in biomarkers and/or immune response to LPS (Comas et al., 2017). The sample size of 11 is small, albeit consistent with recommendations for pilot studies (Moore et al., 2011). Results are preliminary pending replication in a larger sample. Furthermore, this study did not assess microbiota or gut barrier function and was limited to changes in LPS as a proxy for microbial translocation. This assumption is based on observations of elevated plasma LPS in individuals with disrupted gut barrier function (Brenchley et al., 2006; Leclercq et al., 2012). Given that the present study administered moderate alcohol to healthy nonchronic drinkers, dysbiosis is unlikely to be the primary mechanism of observed changes. Future research also should investigate other biomarkers of inflammation such as C-reactive protein, which may be involved in the shift toward an immune-inhibitory state under acute alcohol (Gacouin et al., 2014). Finally, the limited window of biomarker assessment leaves uncertainty as to longer term perturbations in immune activity. Strengths include detailed assessment of health status and alcohol use to obtain a homogeneous sample of healthy, moderate drinkers. In addition, our administration procedures achieved the target BrAC with low variability. In conclusion, this preliminary study adds to emerging understanding of immune perturbations related to alcohol use and links immune markers to alcohol craving in a nonclinical sample.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Jaclynn Kurpewski, BS, MLS ASCP of The Miriam Hospital Immunology Research. Laboratory and Andrew Henderson, PhD, and Matthew Au of Boston University Medical Center. Analytical Instrumentation Core for technical assistance with immunoassays. This research was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [grant number K23AA024704 to M.M.]; the National Institute of Nursing Research [grant number K23NR014951 to P.C.]; and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences through the Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE) grants to the Center for Addiction and Disease Risk Exacerbation [grant number P20GM130414 to P.M.] and the Center for Central Nervous System Function [grant number P20GM103645 to J.S.]

References

- Afshar M, Richards S, Mann D et al. (2015) Acute immunomodulatory effects of binge alcohol ingestion. Alcohol 49:57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlung M, McCarty KN, Morris DH et al. (2015) Increased behavioral economic demand and craving for alcohol following a laboratory alcohol challenge. Addiction 110:1421–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bala S, Marcos M, Gattu A et al. (2014) Acute binge drinking increases serum endotoxin and bacterial DNA levels in healthy individuals. PLoS One 9:e96864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraldi AN, Enders CK (2010) An introduction to modern missing data analyses. J Sch Psychol 48:5–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr T, Helms C, Grant K et al. (2016) Opposing effects of alcohol on the immune system. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 65:242–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazil V, Strominger JL (1991) Shedding as a mechanism of down-modulation of CD14 on stimulated human monocytes. J Immunol 147:1567–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkhaug ST, Neupane SP, Bramness JG et al. (2020) Plasma cytokine levels in patients with chronic alcohol overconsumption: Relations to gut microbiota markers and clinical correlates. Alcohol 85:35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blednov YA, Bergeson SE, Walker D et al. (2005) Perturbation of chemokine networks by gene deletion alters the reinforcing actions of ethanol. Behav Brain Res 165:110–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blednov YA, Ponomarev I, Geil C et al. (2012) Neuroimmune regulation of alcohol consumption: Behavioral validation of genes obtained from genomic studies. Addict Biol 17:108–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenchley JM, Douek DC (2012) Microbial translocation across the GI tract. Annu Rev Immunol 30:149–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW et al. (2006) Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat Med 12:1365–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bufler P, Stiegler G, Schuchmann M et al. (1995) Soluble lipopolysaccharide receptor (CD14) is released via two different mechanisms from human monocytes and CD14 transfectants. Eur J Immunol 25:604–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull-Otterson L, Feng W, Kirpich I et al. (2013) Metagenomic analyses of alcohol induced pathogenic alterations in the intestinal microbiome and the effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG treatment. PLoS One 8:e53028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canesso M, NL Lacerda N, Ferreira C et al. (2014) Comparing the effects of acute alcohol consumption in germ-free and conventional mice: The role of the gut microbiota. BMC Microbiol 14:240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comas M, Gordon CJ, Oliver BG et al. (2017) A circadian based inflammatory response – Implications for respiratory disease and treatment. Sleep Science and Practice 1:18. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA. (2011) Defining risk drinking. Alcohol Res Health 34:144–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jong WJ, Cleveringa AM, Greijdanus B et al. (2015) The effect of acute alcohol intoxication on gut wall integrity in healthy male volunteers; a randomized controlled trial. Alcohol 49:65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT, Vogel-Sprott M (1998) Behavioral impairment under alcohol: Cognitive and pharmacokinetic factors. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 22:1476–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gacouin A, Roussel M, Le Priol J et al. (2014) Acute alcohol exposure has an independent impact on C-reactive protein levels, neutrophil CD64 expression, and subsets of circulating white blood cells differentiated by flow cytometry in nontrauma patients. Shock 42:192–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebeler M, Gillitzer R, Kilian K et al. (2001) Multiple signaling pathways regulate NF-kappaB-dependent transcription of the monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 gene in primary endothelial cells. Blood 97:46–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyongyosi B, Cho Y, Lowe P et al. (2019) Alcohol-induced IL-17A production in Paneth cells amplifies endoplasmic reticulum stress, apoptosis, and inflammasome-IL-18 activation in the proximal small intestine in mice. Mucosal Immunol 12:930–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haziot A, Tsuberi BZ, Goyert SM (1993) Neutrophil CD14: Biochemical properties and role in the secretion of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in response to lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol 150:5556–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Crews FT (2008) Increased MCP-1 and microglia in various regions of the human alcoholic brain. Exp Neurol 210:349–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hritz I, Mandrekar P, Velayudham A et al. (2008) The critical role of toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 in alcoholic liver disease is independent of the common TLR adapter MyD88. Hepatology 48:1224–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchens RL, Thompson PA (2005) Modulatory effects of sCD14 and LBP on LPS-host cell interactions. J Endotoxin Res 11:225–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchens RL, Thompson PA, Viriyakosol S et al. (2001) Plasma CD14 decreases monocyte responses to LPS by transferring cell-bound LPS to plasma lipoproteins. J Clin Invest 108:485–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laso FJ, Iglesias MC, Lopez A et al. (1998) Increased interleukin-12 serum levels in chronic alcoholism. J Hepatol 28:771–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq S, Cani PD, Neyrinck AM et al. (2012) Role of intestinal permeability and inflammation in the biological and behavioral control of alcohol-dependent subjects. Brain Behav Immun 26:911–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq S, Timary P, Delzenne NM et al. (2017) The link between inflammation, bugs, the intestine and the brain in alcohol dependence. Transl Psychiatry 7:e1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq S, Matamoros S, Cani PD et al. (2014) Intestinal permeability, gut-bacterial dysbiosis, and behavioral markers of alcohol-dependence severity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:E4485–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levels JH, Marquart JA, Abraham PR et al. (2005) Lipopolysaccharide is transferred from high-density to low-density lipoproteins by lipopolysaccharide-binding protein and phospholipid transfer protein. Infect Immun 73:2321–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liangpunsakul S, Toh E, Ross RA et al. (2017) Quantity of alcohol drinking positively correlates with serum levels of endotoxin and markers of monocyte activation. Sci Rep 7:4462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Jiang Y, Li Y et al. (2013) TLR4 signaling augments monocyte chemotaxis by regulating G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 translocation. J Immunol 191:857–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall SA, McKnight KH, Blose AK et al. (2017) Modulation of binge-like ethanol consumption by IL-10 signaling in the Basolateral Amygdala. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 12:249–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Earleywine M, Musty RE et al. (1993) Development and validation of the biphasic alcohol effects scale. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 17:140–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milivojevic V, Ansell E, Simpson C et al. (2017) Peripheral immune system adaptations and motivation for alcohol in non-dependent problem drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 41:585–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnig MA, Woods AJ, Walsh E et al. (2019) Cerebral metabolites on the descending limb of acute alcohol: A preliminary 1H MRS study. Alcohol Alcohol 54:487–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CG, Carter RE, Nietert PJ et al. (2011) Recommendations for planning pilot studies in clinical and translational research. Clin Transl Sci 4:332–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutlu EA, Gillevet PM, Rangwala H et al. (2012) Colonic microbiome is altered in alcoholism. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 302:G966–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupane SP, Skulberg A, Skulberg KR et al. (2016) Cytokine changes following acute ethanol intoxication in healthy men: A crossover study. Mediators Inflamm 2016:3758590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIAAA (2018) Alcohol Facts and Statistics. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Orio L, Anton M, Rodriguez-Rojo IC et al. (2018) Young alcohol binge drinkers have elevated blood endotoxin, peripheral inflammation and low cortisol levels: Neuropsychological correlations in women. Addict Biol 23:1130–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park BS, Lee JO (2013) Recognition of lipopolysaccharide pattern by TLR4 complexes. Exp Mol Med 45:e66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual M, Montesinos J, Marcos M et al. (2017) Gender differences in the inflammatory cytokine and chemokine profiles induced by binge ethanol drinking in adolescence. Addict Biol 22:1829–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plociennikowska A, Hromada-Judycka A, Borzecka K et al. (2015) Co-operation of TLR4 and raft proteins in LPS-induced pro-inflammatory signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci 72:557–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugin J, Schurer-Maly CC, Leturcq D et al. (1993) Lipopolysaccharide activation of human endothelial and epithelial cells is mediated by lipopolysaccharide-binding protein and soluble CD14. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:2744–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueger SY, King AC (2013) Validation of the brief biphasic alcohol effects scale (B-BAES). Alcohol Clin Exp Res 37:470–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA. (1982) The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav 7:363–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LCS, B M (1992) Timeline Followback: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption In Allen JLRZ. (ed). Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biological Methods, pp. 41–72. Totowa: NJ: Humana Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stadlbauer V, Horvath A, Komarova I et al. (2019) A single alcohol binge impacts on neutrophil function without changes in gut barrier function and gut microbiome composition in healthy volunteers. PLoS One 14:e0211703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo G, Bala S (2010) Alcoholic liver disease and the gut-liver axis. World J Gastroenterol 16:1321–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo G, Chavan S, Mandrekar P et al. (1999) Acute alcohol consumption attenuates interleukin-8 (IL-8) and monocyte chemoattractant peptide-1 (MCP-1) induction in response to ex vivo stimulation. J Clin Immunol 19:67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilg H, Moschen AR, Szabo G (2016) Interleukin-1 and inflammasomes in alcoholic liver disease/acute alcoholic hepatitis and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 64:955–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung KH, Huang YS, Yang KC et al. (2010) Serum interleukin-12 levels in alcoholic liver disease. J Chin Med Assoc 73:67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umhau JC, Schwandt M, Solomon MG et al. (2014) Cerebrospinal fluid monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in alcoholics: Support for a neuroinflammatory model of chronic alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38:1301–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y, Freeswick PD, Khemlani LS et al. (1995) Role of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), interleukin-1, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor, and dexamethasone in regulation of LPS-binding protein expression in normal hepatocytes and hepatocytes from LPS-treated rats. Infect Immun 63:2435–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurfel MM, Hailman E, Wright SD (1995) Soluble CD14 acts as a shuttle in the neutralization of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) by LPS-binding protein and reconstituted high density lipoprotein. J Exp Med 181:1743–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Ma HY, Liu X et al. (2020) Blockade of IL-17 signaling reverses alcohol-induced liver injury and excessive alcohol drinking in mice. JCI Insight 5:e131277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan AW, Fouts DE, Brandl J et al. (2011) Enteric dysbiosis associated with a mouse model of alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 53:96–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z, Mates JM, Cheplowitz AM et al. (2016) Blood-borne lipopolysaccharide is rapidly eliminated by liver sinusoidal endothelial cells via high-density lipoprotein. J Immunol 197:2390–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Wang H, Xu et al. (2018) Role of MCP-1 and CCR2 in ethanol-induced neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in the developing brain. J Neuroinflammation 15:197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuba D. (2008) Accuracy and reliability of breath alcohol testing by handheld electrochemical analysers. Forensic Sci Int 178:e29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]