Abstract

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is a major complication of diabetes and the leading cause of end-stage renal failure. Epigenetics has been associated with metabolic memory in which prior periods of hyperglycemia enhance the future risk of developing DKD despite subsequent glycemic control. To understand the mechanistic role of such epigenetic memory in human DKD and to identify new therapeutic targets, we profiled gene expression, DNA methylation, and chromatin accessibility in kidney proximal tubule epithelial cells (PTECs) derived from subjects with and without type 2 diabetes (T2D). T2D-PTECs displayed persistent gene expression and epigenetic changes with and without transforming growth factor-β1 treatment, even after culturing in vitro under similar conditions as nondiabetic PTECs, signified by deregulation of fibrotic and transport-associated genes (TAGs). Motif analysis of differential DNA methylation and chromatin accessibility regions associated with genes differentially regulated in T2D revealed enrichment for SMAD3, HNF4A, and CTCF transcription factor binding sites. Furthermore, the downregulation of several TAGs in T2D (including CLDN10, CLDN14, CLDN16, SLC16A2, and SLC16A5) was associated with promoter hypermethylation, decreased chromatin accessibility, and reduced enrichment of HNF4A, histone H3-lysine-27-acetylation, and CTCF. Together, these integrative analyses reveal epigenetic memory underlying the deregulation of key target genes in T2D-PTECs that may contribute to sustained renal dysfunction in DKD.

Introduction

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is a major vascular complication of diabetes and the leading cause of end-stage renal failure (1). Despite strict glucose and blood pressure control, >25% of patients with diabetes develop DKD. The key features of DKD include kidney glomerular and tubular dysfunction associated with fibrosis as a result of increased deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins such as collagens (2,3). Many studies have emphasized the importance of early and intensive glycemic control for the prevention/delayed onset of diabetic complications, including DKD (4–6). These studies identified a memory of prior intensive or conventional glycemic control therapy, which affects the risk of developing future complications despite subsequent glucose normalization, referred to as metabolic memory or legacy effect. Studies have implicated epigenetic mechanisms in metabolic memory (7), but the molecular mechanisms for such epigenetic memory in renal cells/tissues from subjects with diabetes despite glucose normalization are not clear. A comprehensive study of the underlying epigenomic changes and related mechanisms leading to persistent gene expression may enable the development of new therapeutics to erase the memory and prevent DKD progression.

Epigenetic memory refers to dynamic, heritable epigenetic regulation of gene expression in response to previous stimuli (e.g., hyperglycemia in diabetes) (8,9). Epigenetic/transcriptional memory may also potentiate gene expression upon reexposure to the same stimulus. Although studies suggest that DNA methylation (DNAme), chromatin histone modifications, or chromatin states/accessibility play significant roles in regulating epigenetic memory (8), the integrative effects of these mechanisms in DKD need to be defined. Evidence from experimental models and epigenome-wide associations studies suggests associations between aberrant epigenetic changes, especially DNAme and histone modifications, in renal fibrosis, inflammation, and pathogenesis of DKD (9–17). A few systematic studies have used integrative analyses to characterize the functional consequences of the interplay between the genome and the epigenome and key kidney disease–related loci (18,19). However, the direct impact of epigenetic memory from prior hyperglycemic exposure on gene expression in renal cells of subjects with diabetes needs to be determined. Furthermore, one key consequence of hyperglycemia is the upregulation of transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), a master regulator of DKD-related fibrosis (3,20). TGF-β1 can induce epigenetic changes associated with the expression of fibrotic and inflammatory genes in renal glomerular and tubular cells (21–23), suggesting that TGF-β1 signaling may mediate and amplify hyperglycemic epigenetic memory in DKD.

In the current study, we focused on identifying persistent transcriptomic and epigenomic changes in primary human proximal tubular epithelial cells (PTECs) derived from the kidneys of donors with type 2 diabetes (T2D-PTECs) compared with donors without T2D (N-PTECs) to uncover potential new mechanisms and therapeutic targets for metabolic memory of DKD. We compared the transcriptome, DNA methylome, and chromatin accessibility of these N-PTECs and T2D-PTECs cultured under similar growth conditions with or without TGF-β1. We performed integrative analyses of these genomic data sets to identify T2D, as well as TGF-β1–dependent and –independent, changes. Our results provide strong evidence of epigenetic memory in the deregulated transcription of fibrotic and key transport-associated genes (TAGs) in T2D-PTECs and show that T2D-PTECs are more sensitive to TGF-β1. These data demonstrate novel mechanisms for chronic tubular dysfunction in DKD, even after glycemic control.

Research Design and Methods

Renal PTEC Culture

PTECs were from two donors each for N-PTECs (CC-2553; Lonza, Morristown, NJ) and T2D-PTECs (CC-2925; Lonza) (details in Supplementary Table 1). All PTECs (two independent replicates for each donor) were cultured in renal epithelial growth medium (REGM) (Lonza) for four passages before harvesting at ∼80% confluency for downstream experiments. TGF-β1 signaling was induced by adding TGF-β1 (10 ng/mL; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to the REGM at ∼70% cell confluency. To check for epigenetic memory of TGF-β1 actions, N- and T2D-PTECs were first treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/mL) for 24 h and 96 h. Cells were then washed with PBS and cultured in REGM without TGF-β1 for 96 h.

RNA Sequencing and Data Analysis and RT-PCR

RNA was harvested using an RNeasy Kit (74106; QIAGEN). Briefly, total RNA extracted from replicates of two independent cultures of each PTEC (8 samples total) was used to make RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) libraries (16 in total, with and without TGF-β1 treatment) using the Ribo Zero Gold (Illumina, San Diego, CA) protocol. Strand-specific, paired-end, 100-base pair sequencing for ∼50 million reads/sample was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 system and aligned to hg38 (GENCODE v25) using Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference (STAR) software (24). Analysis for differentially expressed gene (DEG) was performed using DESeq2 (25), with an adjusted P < 0.05 as the threshold significance level. A gene was considered expressed if its transcripts per million (TPM) was >1 in at least one donor PTEC. DESeq2 analysis was performed for the indicated comparison groups (Fig. 1A); with gene ontology (GO) analysis and pathway analysis performed using Bioconductor, significant enriched terms had P < 0.05 and Bonferroni correction with q-value <0.01. RNA-seq data were validated using quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) in triplicate with GAPDH as the control using an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system. Primers used are shown in Supplementary Table 2. To quantify expression, average threshold cycle (Ct) values from triplicates were normalized with average Ct values of GAPDH.

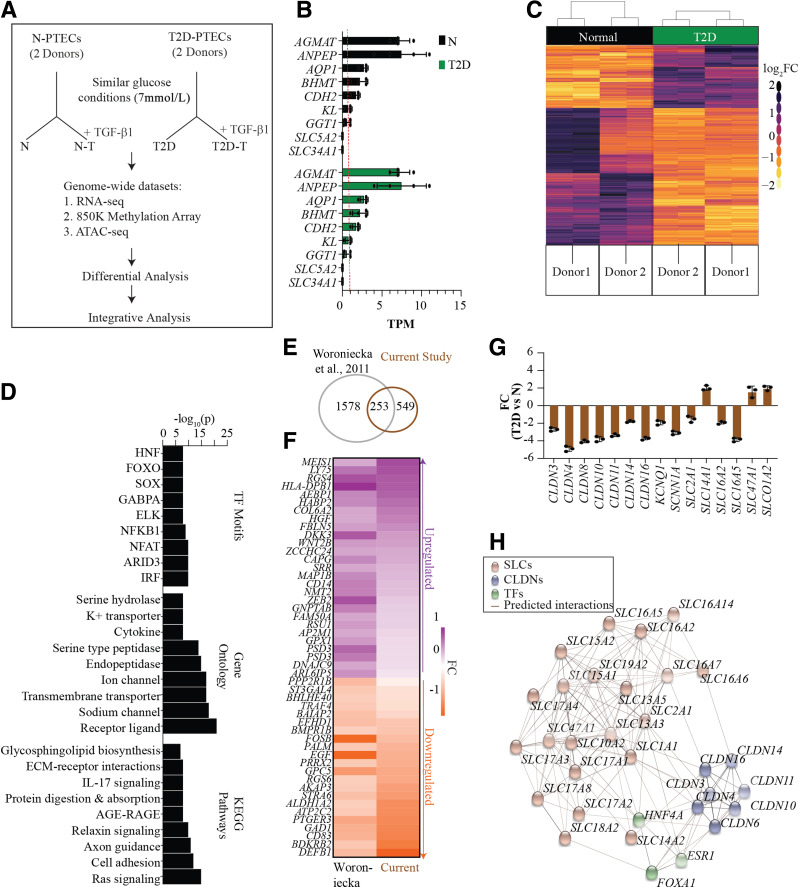

Figure 1.

Transcriptome profiling of cultured N-PTECs and T2D-PTECs. A: Schematic of the experimental design showing PTEC samples and conditions used to study epigenetic memory. PTECs from two control donors without diabetes (N-PTECs) and donors with T2D (T2D-PTECs) were cultured under similar glucose conditions (7 mmol/L) and subsequently treated with or without TGF-β1 (10 ng/mL) for 24 h. Cells were processed for profiling as shown. B: Bar chart showing expression of kidney proximal tubule-specific genes in TPM. Each bar represents the average TPM for replicates, and the red line represents 1 TPM. Individual data points are shown as dots. Error bars = SD. C: Heat map of hierarchical clustering of normalized count data for DEGs in N and T2D; pseudocolor normalization ranges from light yellow (downregulation) to dark purple (upregulation) on a log2 fold change (log2FC) (T2D vs. N) scale. Donor 1 and donor 2 represent the two donors each for N and T2D. Two columns for each donor represent independent RNA-seq replicates. The heat map of scaled log2FC is based on normalized read counts from RNA-seq for N- and T2D-PTECs and generated using DESeq2 (see research design and methods). Each row represents scaled values for a gene across all the samples on a pseudoscale to highlight the variations across the samples. D: Bar plot representing the top nine enriched KEGG pathways, GO terms, and TF motifs for N vs. T2D DEGs. Bar = −log10(p). E: Venn diagram of number of DEGs common between the current study and a published DKD study by Woroniecka et al. (38). F: Pseudocolor heat map displaying expression of selected genes common to both the current study and by Woroniecka et al. The downregulated or upregulated genes are down- or upregulated in T2D compared with N in both these studies. G: RT-qPCR validation of candidate TAGs. Bar = average FC in T2D vs. N (n = 3); P < 0.05, ANOVA with Tukey post hoc testing. FC is calculated as 2−ΔΔCt, and individual data points are shown as dots. H: Interaction map displaying representative TAGs as predicted targets for HNF4A, ESR1, and FOXA1 TFs on the basis of the presence of respective TF binding sites in their promoters (±2 kb). AGE-RAGE, advanced glycosylation end product-receptor of advanced glycosylation end product.

DNAme Profiling and Data Analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from PTECs using a QIAamp DNA Micro Kit (QIAGEN) and 1 μg DNA used for Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip arrays (Illumina). Independent replicates from each PTEC were used (14 samples in total, without the addition of TGF-β1, and after 24, 72, or 96 h of TGF-β1 treatment). Raw data were analyzed using minfi and ChAMP packages (26,27). Briefly, data were preprocessed for background and control normalization followed by Subset-quantile Within Array Normalization. Differentially methylated CpG sites (DMP) and regions (DMR) were identified per ChAMP package. β-Values (% of DNAme) were calculated as methylated / (methylated + unmethylated). Changes in β-values (Δβ) were calculated as T2D:β − N:β. CpGs meeting any of these criteria were removed: detection P > 0.01, methylation <30% in at least one sample, general single nucleotide polymorphisms, and multihits. Enrichment analysis of genes within 50 kilobases (kb) of DMRs was performed. Locus-specific methylation was measured using EpiTect Methyl assays (59436; QIAGEN) for selected TAGs in triplicate. Primers were designed on the basis of genomic coordinates (hg38, GENCODE v25) for DMRs (primer sequences in Supplementary Table 2).

Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin Sequencing and Data Analysis

Assay for transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing (ATAC-seq) library preparation was performed as described (28) with 50,000 PTECs, one from each donor, with or without TGF-β1 treatment (Supplementary Table 3). DNA was purified using QIAGEN MinElute Reaction Cleanup Kit and amplified with NEBNext High-Fidelity 2X PCR Master Mix (NEB) followed by library purification using AMPure XP beads. One hundred-base pair paired-end libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 system. Reads were aligned to hg38 (GENCODE v25) using Bowtie 2 (29) and peaks called using MACS2 (30). Differential peak analysis was performed using DESeq2, with adjusted P < 0.05 as the threshold for significance levels. Each differential peak (d-ATAC) was associated with the closest transcription start site (TSS) (±50 kb). Motif analysis of d-ATACs was performed using Homer (31). GO analysis and pathway analysis were performed using Bioconductor with P < 0.05 and Bonferroni correction with q-value <0.01.

Integrative Analysis

We used regression analysis and bedtools to quantify correlations among DNAme, ATAC-seq, DEGs, and hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (HNF4A) motifs. Script used is accessible upon request at https://github.com/bansalanita/EM.

Immunofluorescence Assays

We used CellROX Orange Reagent (C10443; Invitrogen) for detecting oxidative stress (OS) and Col-F green fluorescence kit (6346; ImmunoChemistry Technologies, Bloomington, MN) for detecting collagens per the manufacturer’s protocols. Briefly, PTECs were cultured in triplicate in six-well plates (50,000 cells), washed twice, treated with CellROX or Col-F reagents, and measured using a plate reader.

5-Azacytidine Treatments

PTECs (∼70% confluence) were treated with 500 nmol/L 5-azacytidine (5-AZA) (A2385; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 72 h, followed by downstream experiments.

Global DNAme Assay and ELISA for HNF4A

Global methylation changes (%) after 5-AZA treatment were measured using MethylFlash Global DNA Methylation ELISA Easy Kit (P-1030, n = 3; Epigentek). HNF4A protein was measured using Human HNF-4-alpha ELISA Kit (ab210581, n = 3; Abcam).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assays

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed in triplicate using 5 million cells with antibodies for HNF4A (ab41898; Abcam), CCCTC binding factor (CTCF) (C15410210; Diagenode), RNA polymerase II (Pol II) (CTD4H8; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:1,000 dilution, and H3K27ac (ab4729, 1:2,000 dilution; Abcam) following ENCODE protocols (32). qPCRs were performed on 1 μL of ChIP-enriched DNAs and input DNA (control) using an ABI system (primer sequences are shown in Supplementary Table 2). Percent enrichment was calculated as 1) ΔCt = CtChIP − Ctinput and 2) % enrichment = 100 / 2ΔCt.

Statistics

Unless otherwise specified, we used R software for statistical analyses and ANOVA to calculate the level of significance with Tukey post hoc testing.

Data and Resource Availability

The data sets generated in this study are deposited into Gene Expression Omnibus (series GSE145747). They are also available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Results

Experimental Design

We used deidentified human PTECs from two control subjects without diabetes (N-PTECs) and two subjects with T2D (T2D-PTECs) from commercial sources (Supplementary Table 1). We cultured the cells in vitro under similar growth conditions with near-normal glucose (7 mmol/L) in the medium for four passages and treated them without or with TGF-β1 (T) (10 ng/mL) for 24 h. T2D-PTECs appeared larger and more elongated in culture than N-PTECs, and this (fibroblast-like) elongated phenotype was even more pronounced after TGF-β1 treatment in both N-T and T2D-T cells (Supplementary Fig. 1). We performed RNA-seq, DNAme, and ATAC-seq profiling on PTECs to identify transcriptomic and epigenomic signatures characterizing epigenetic memory of diabetic renal tubular dysfunction (Fig. 1A). For differential analyses, we compared 1) T2D versus N to compare untreated T2D-PTECs and N-PTECs, 2) N-T versus N, and 3) T2D-T versus T2D to evaluate the TGF-β1–induced changes in N- and T2D-PTECs. Furthermore, we cultured N- and T2D-PTECs from each donor with TGF-β1 (10 ng/mL) for up to 96 h followed by culture without TGF-β1 to examine potential epigenetic memory of TGF-β1 exposure. Validations were performed using RT-qPCRs, DNAme, and ChIP assays for candidate genes.

Characterization of Persistent Gene Expression Signatures in T2D-PTECs

To first verify the integrity of cultured PTECs, we queried our RNA-seq data sets for the expression of known proximal tubule-specific genes (33,34). RNA-seq detected expression (TPM ≥1) of several candidate tubular-specific genes (e.g., AGMAT, ANPEP, AQP1, BHMT, and CDH2) in both N-PTECs and T2D-PTECs (Fig. 1B). We did not detect other tubule-specific genes SLC5A2 and SLC34A1 in either group, suggesting a potential impact of in vitro culture.

The hierarchical clustering of the RNA-seq data sets showed distinct DEG profiles for N-PTECs and T2D-PTECs (Fig. 1C). We identified 1,486 DEGs (adjusted P < 0.05), of which 801 showed a more than twofold change (Supplementary Fig. 2A and B). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs revealed enrichment for cell adhesion, Ras signaling, ECM-receptor interactions, and advanced glycation end products and receptor for advanced glycation end products signaling, all related to DKD (2,3,35) (Fig. 1D). GO for molecular functions showed enrichment for membrane and solute transport, ion channel, and peptidase activity (Fig. 1D), which are related to tubular functions. Analyses of promoter regions (5 kb ± TSS) identified binding sites for transcription factor (TF) families (e.g., HNF, forkhead box protein O [FOXO], nuclear factor-κB1 [NF-κB1], nuclear factor of activated T cells [NFAT]) (Fig. 1D), some of which have been implicated as potential targets for DKD (36,37). To assess the extent to which our cultured PTECs recapitulated gene expression signatures observed in vivo, we compared our data with published studies in tubuli isolated from patients with DKD (38). Approximately 32% of the DEGs (i.e., 253 genes identified in our study) overlapped with DKD-associated genes identified by Woroniecka et al. (38) (Fig. 1E and F), suggesting that our cultured T2D-PTECs maintain their tubular characteristics and express genes associated with DKD.

Considering that filtration and reabsorption are primary functions of proximal tubules, and GO analysis showed enrichment of TAGs, we further explored the deregulated TAGs. We found differential expression of 103 TAGs in T2D-PTECs, including solute carrier (SLC) and claudin (CLDN) genes (Fig. 1G and Supplementary Fig. 3A). Fifty-nine of these 103 TAGs are also differentially expressed in at least one of three published studies of tubular samples or whole kidney from subjects with DKD (38–40) (Supplementary Fig. 3B). Motif analysis predicted the enrichment of HNF4A, FOXA1, and estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) binding sites in the deregulated TAGs, especially SLCs and CLDNs (Fig. 1H). SLC transporters are membrane-bound proteins mediating the transport of molecules across cellular membranes, while CLDN proteins are critical components of tight junctions regulating paracellular transport (41–43). Hence, the sustained deregulation of SLC and CLDN genes in T2D cells cultured in near-normal glucose conditions could have profound effects on metabolic memory, kidney function, and clinical outcomes; however, there is only limited information on their roles in diabetes and DKD (44). Together, these RNA-seq data demonstrate that T2D-PTECs maintain a distinct cellular context and transcriptional memory of the prior diabetic environment relative to N-PTECs, which are preserved even after in vitro culture under nondiabetic conditions.

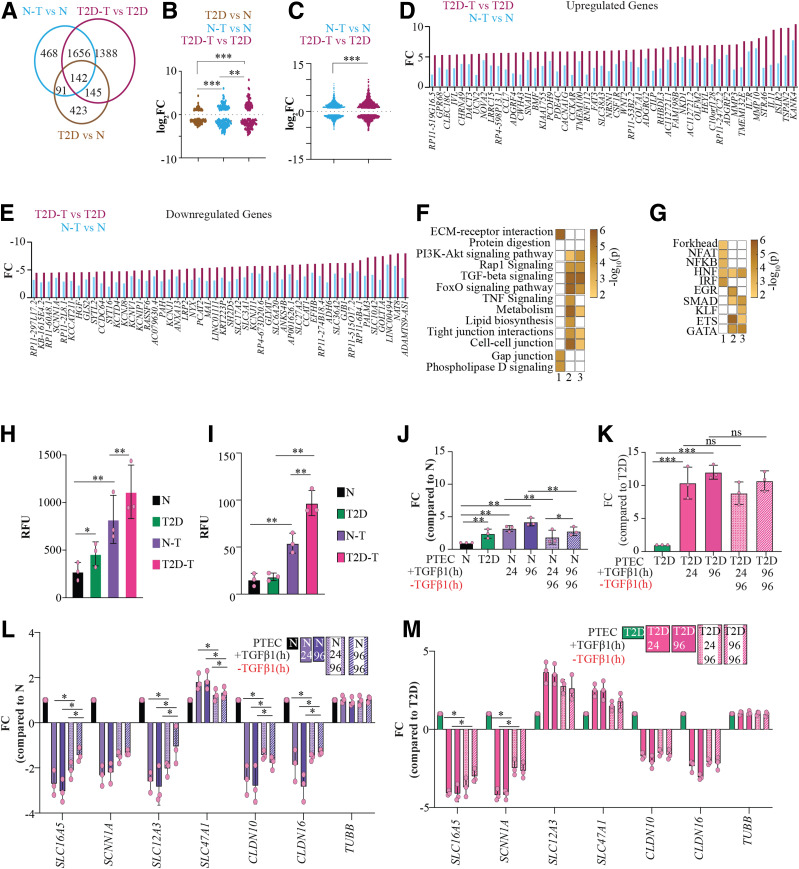

Differential Gene Expression Profile of T2D-PTECs in Response to TGF-β1 Exposure

We next examined whether T2D-PTECs display differential responses to TGF-β1 compared with N-PTECs. Treatment of N-PTECs with TGF-β1 resulted in >2,000 DEGs (N-T vs. N) but >3,000 DEGs in T2D-PTECs (T2D-T vs. T2D) (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. 4A). We identified 1,798 TGF-β1–dependent genes, including those common between N-T and T2D-T (Fig. 2A). We found 142 deregulated genes in T2D-PTECs versus N-PTECs and responsive to TGF-β1 in both N- and T2D-PTECs (i.e., common to all three groups) (Fig. 2A). These 142 could represent genes that are TGF-β1 dependent and constitutively deregulated under diabetic conditions. Notably, 1,533 DEGs exhibited variable expression only in T2D and T2D-T cells, implying that the diabetic environment influences TGF-β1 signaling.

Figure 2.

Transcriptome and phenotypic changes in PTECs after TGF-β1 treatment. A: Venn diagram showing overlapping DEGs observed in three groups: N-T vs. N, T2D-T vs. T2D, and T2D vs. N. B and C: Violin plot for distribution of the change in expression levels of 142 DEGs common to the three groups (B) and expression levels of DEGs common to N-T vs. N and T2D-T vs. T2D cells (C). D and E: Bar plots depicting differential response to TGF-β1 treatment in T2D and N for candidate upregulated (D) and downregulated (E) DEGs in N-T vs. N and T2D-T vs. T2D. F and G: Pseudocolor representation of KEGG pathways (F) and TF families (G) enriched for DEGs in Venn diagram shown in panel A. 1) T2D vs. N only, 2) T2D-T vs. T2D, 3) N-T vs. N. Color in each box for panels F and G represent −log10(p). H and I: Measurement of OS in PTECs using CellROX Orange assay (H) and collagen using Col-F fluorescent assay (I). Bar = average relative fluorescent units (RFUs) (n = 3). J–M: Measurement of change in Col6A2 (J and K), SLC16A5, SCNN1A, SLC12A3, SLC47A1, CLDN10, CLDN16, and TUBB (L and M) expression observed in N and T2D samples with TGF-β1 treatment and subsequent removal of TGF-β1 using RT-qPCR. Bars = average fold change (FC) (n = 3). Error bars = SD. Black, N; green, T2D; purple, N-T (24-h TGF-β1 treatment); dark purple, N-T (96-h TGF-β1 treatment); pink, T2D-T (24-h TGF-β1 treatment); dark pink, T2D-T (96-h TGF-β1 treatment). Shaded bars represent change in expression for indicated genes 96 h after removal of TGF-β1. Error bars = SD. Individual data points are shown as dots. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0005. ns, not significant.

To delineate the transcriptional outcome of TGF-β1 signaling in the diabetes environment, we compared the fold change in DEGs common to three groups: T2D versus N, N-T versus N, and T2D-T versus T2D (Fig. 2B and C). The 142 overlapping DEGs common to all three comparisons showed the least variation in T2D versus N and the highest variation in T2D-T versus T2D (Fig. 2B). Similarly, when comparing the 1,798 TGF-β1–responsive DEGs common between N-T and T2D-T, T2D-T versus T2D showed significantly higher TGF-β1–induced response (Fig. 2C–E). These data demonstrate that the T2D cells are more sensitive to TGF-β1, which may be due to epigenetic memory of the diabetic environment.

DEGs unique to T2D versus N (potentially TGF-β1 independent) showed the highest enrichment for ECM-receptor interactions, while genes common to TGF-β1 response in both PTECs showed enrichment for phosphoinositide-3-kinase-Akt (PI3K-Akt), TGF-β, Ras-proximate-1 (Rap1), and FOXO signaling, tight junction, and cell-cell junctions (Fig. 2F). Motif analyses of promoters of DEGs unique to T2D versus N showed enrichment of binding sites for NF-κB, HNF, interferon regulatory factor (IRF), and forkhead factors, whereas TGF-β1–responsive DEGs in T2D-T and N-T revealed enrichment for HNF, mothers against decapentaplegic homolog (SMAD), GATA binding proteins (GATA), and E26 transformation-specific (ETS) binding sites (Fig. 2G).

Interestingly, we observed deregulation of 320 TAGs in T2D-T and 246 TAGs in N-T. Nineteen TAGs showed differential expression exclusively in N-T (Supplementary Fig. 4B and C). Forty TAGs showed TGF-β1–independent deregulation in T2D. Because only 19 TAGs were unique to N-T versus N, while the remaining TAGs were altered in T2D-PTECs, it suggests that numerous TAGs are uniquely deregulated by T2D-related memory (Supplementary Fig. 4B and C).

We next evaluated whether the observed transcriptional memory in T2D in the cultured PTECs was also associated with a memory of phenotypic traits for DKD, such as OS and fibrosis. Fluorescent staining revealed higher OS in T2D and T2D-T compared with N and N-T PTECs, respectively (Fig. 2H). Fluorescent staining for collagens showed that TGF-β1 increases the expression of collagens in both N-T and T2D-T cells. Additionally, the magnitude of Col-F change was significantly higher in T2D-T versus N-T, suggesting that T2D cells are also more sensitive TGF-β1–mediated cellular phenotypes related to DKD (Fig. 2I).

To evaluate this further, we next examined whether the expression of TGF-β1–inducible collagen/TAGs shows persistent expression between N- and T2D-PTECs, even after the removal of TGF-β1. COL6A2 was upregulated in T2D versus N and was also increased by TGF-β1 in both N-T and T2D-T PTECs, with higher induction in T2D-T (Fig. 2J and K). Interestingly, while COL6A2 levels were reduced significantly in N-T after removing TGF-β1 from culture media for 96 h (Fig. 2J), it remained elevated in T2D-T cells (Fig. 2K). Expression of candidate TAGs SCL16A5, SCNN1A, SLC12A3, SLC47A1, CLDN10, and CLDN16 also exhibited similar behavior, depicting reversal in N-T cells but not in T2D-T cells after removing TGF-β1 for 96 h (Fig. 2L and M). These data show that relative to N-T, T2D-T cells exhibit a more exaggerated response to TGF-β1, as well as a memory of TGF-β1 exposure, on genes and phenotypes associated with DKD.

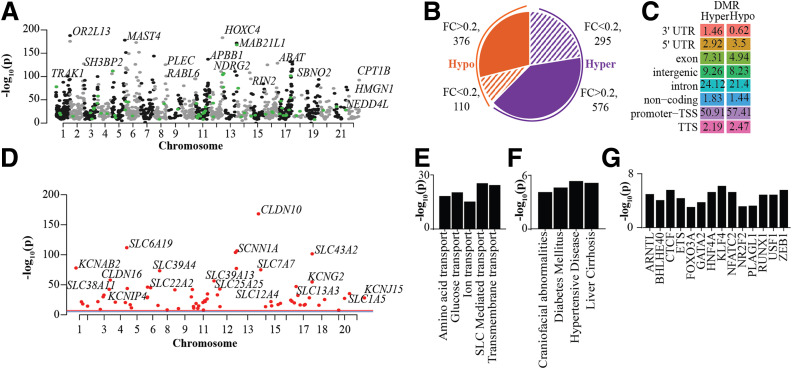

Identification of Differential Methylation Signatures in T2D-PTECs

Next, to determine the role of epigenetics in the observed transcriptional memory, we profiled DNAme signatures in PTECs using EPIC arrays. We identified 6,772 hypermethylated and 4,383 hypomethylated probes (DMPs, false discovery rate <0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 5A and B) in T2D versus N-PTECs. More than 40% of DMPs were located within gene bodies, with no differences in the distribution of DMPs relative to CpG islands (Supplementary Fig. 5C). Further analysis identified 376 hypomethylated and 526 hypermethylated DMRs, showing at least 20% variation (Δβ) in T2D versus N (Fig. 3A and B), and another 405 DMRs showed Δβ <20%. Genomic annotation revealed an abundance of T2D hypermethylated DMRs in the 3′ un translated region (UTR) and intronic regions and more enrichment of hypo-DMRs in the promoters and 5′UTR (Fig. 3C). Notably, >200 TAGs had a DMR within 20 kb of TSS (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

DNAme profiles of PTECs showing differential patterns in N- and T2D-PTECs. A: Manhattan plot of DMRs in T2D-PTECs compared with N-PTECs. Top DMR-associated genes are highlighted. Each dot depicts a DMR; black and gray dots are for DMRs in even and odd chromosomes, and green dots highlight DMRs associated with TAGs. B: Pie chart showing number of DMRs on the basis of fold change (FC) (T2D vs. N) and that have an adjusted P < 0.05. Orange indicates hypomethylated DMRs and purple, hypermethylated DMRs. Shaded areas show DMRs with <20% FC, whereas solid colors represent DMRs with >20% FC. C: Percent genomic distribution of hyper- and hypomethylated DMRs. D: Manhattan plot highlighting candidate TAGs with a DMR within 20 kb of their TSS. E–G: Enriched GO pathways (E), disease ontology terms (F), and TF motifs (G) for genes within 50 kb of DMRs. Bar = −log10(p). TTS, transcription termination site.

KEGG analysis of DMR-associated genes (within 50 kb of DMRs) showed enrichment for genes associated with membrane transport, such as glucose, amino acid, and ion transport and SLC-mediated transport (Fig. 3E), and disease ontology analysis identified diabetes, hypertensive disease, and liver cirrhosis as top terms (Fig. 3F). Furthermore, TF motif analysis of DMRs identified enrichment of binding sites for CTCF, HNF4A, ETS, FOXO3A, and so forth (Fig. 3G). We also identified 241 DMRs in T2D-T (96-h TGF-β1 treatment) versus T2D. However, we did not find any DMRs in N-T versus N (96-h TGF-β1) or either T2D- or N-PTECs after 24 h of TGF-β1 treatment (Supplementary Fig. 5D). Relatively small numbers of DMRs with TGF-β1 treatment only in T2D-T and only after 96 h suggest that methylation changes are less dynamic. Altogether, DNAme studies revealed persistent DNAme changes in the T2D-PTECs cultured in vitro and suggest a previously unknown role of diabetes-associated DNAme and epigenetic memory in the regulation of TAGs.

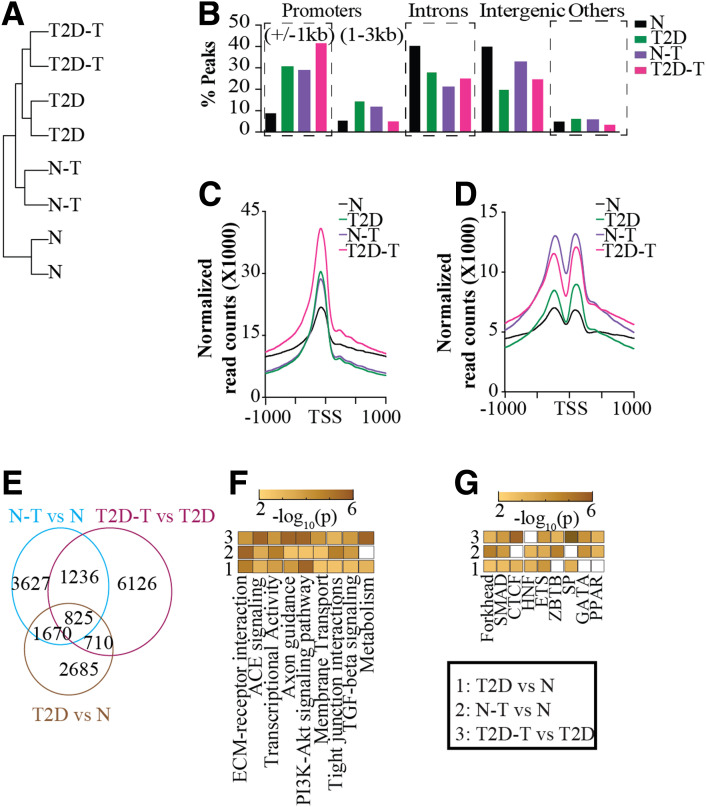

The Landscape of Chromatin Accessibility in PTECs and the Effect of TGF-β1

We next performed ATAC-seq to examine chromatin accessibility as another index of epigenetic memory. ATAC-seq yielded >30 million nucleosome-free reads in PTECs and displayed expected ATAC-seq fragment length profiles (Supplementary Fig. 6), with replicates showing ∼100,000 overlapping peaks in N, T2D, N-T, and T2D-T (Supplementary Table 3). Hierarchical clustering indicated the involvement of TGF-β1 signaling in modifying chromatin accessibility because we observed closer correlations among N-T, T2D, and T2D-T relative to N cells (Fig. 4A). Genomic annotation of the peaks showed differential enrichment in various genomic regions, with N cells having the lowest and T2D-T cells having the highest number of peaks annotated to promoters (±1 kb of TSS), with opposite trends for intronic and distal intergenic regions (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

ATAC-seq profiles of PTECs show more chromatin accessibility in T2D and after TGF-β1 treatment. A: Dendrogram showing hierarchical clustering of d-ATACs of various PTECs, two replicates each, one from each donor for both N and T2D. B: Bar plots showing genomic distribution of ATAC peaks in PTECs. C and D: Profile plots showing ATAC-seq peaks in PTECs, centered on TSS for nucleosome-free reads (C) and mononucleosome reads (D). E: Venn diagram showing overlapping and unique d-ATACs in PTECs. F and G: Pseudocolor representation of top enriched pathways (F) and TF motifs (G) for genes associated with d-ATACs (within 50 kb) in 1) T2D vs. N, 2) N-T vs. N, and 3) T2D-T vs. T2D. Color in each box of panels F and G represents −log10(p).

To assess variations in chromatin accessibility around DEGs, we created a master list combining all DEGs for all three groups together (T2D versus N, T2D-T versus T2D, and N-T versus N) and plotted peak densities around TSS. We observed (Fig. 4C) significantly more nucleosome-free reads around TSS of the DEGs master list in T2D- versus N-PTECs. The number of nucleosome-free reads around DEGs increased further in both T2D-T and N-T, with T2D-T showing the highest. Similar trends were observed for mononucleosome reads (Fig. 4D). Differential analysis for nucleosome-free reads identified 5,890 (T2D vs. N), 7,358 (N-T vs. N), and 8,897 (T2D-T vs. T2D) differential peaks. Of note, 825 differential peaks were present in all groups, while the majority were unique to each group (Fig. 4E). Differential ATAC-seq analysis showed that T2D cells have more changes than N, and the effects of TGF-β1 are more pronounced in T2D.

Furthermore, GO analysis again identified top enrichment terms as transcriptional activators, membrane transport, and ECM proteins (Fig. 4F), as was also seen in the RNA-seq and DMR analyses. Motif analysis also showed enrichment of binding sites for HNF4A, SMAD3, ETS1, and GATA2 TFs (Fig. 4G). Interestingly, we identified d-ATACs associated with ∼400 TAGs in T2D. Together, ATAC-seq yielded novel insights into the role of TGF-β1 and diabetes-induced alterations in chromatin accessibility in regulating the expression of associated genes like TAGs in PTECs and provided more evidence of epigenetic memory.

Integrative Genomic Analyses of DEGs, DMRs, and d-ATAC in T2D Versus N

We observed an inverse correlation (r2 = −0.42, P < 0.05) between key hyper-DMRs and corresponding DEGs (Fig. 5A) in T2D versus N. Of note, several TAGs were hypermethylated and downregulated in T2D-PTECs (Fig. 5B). We identified >1,000 DEGs having d-ATACs within 50 kb of TSS and a positive correlation (r2 = 0.62, P < 0.05) implying altered chromatin accessibility in the regulation of DEGs (Fig. 5C). Moreover, 513 d-ATACs in T2D were within 1 kb of a DMR; of these, 179 hypo-DMRs overlapped with more accessible sites, and 234 hyper-DMRs overlapped with less open sites in T2D (Fig. 5D). Association of DMRs with d-ATACs implies that hypermethylation is associated with closed/inaccessible chromatin.

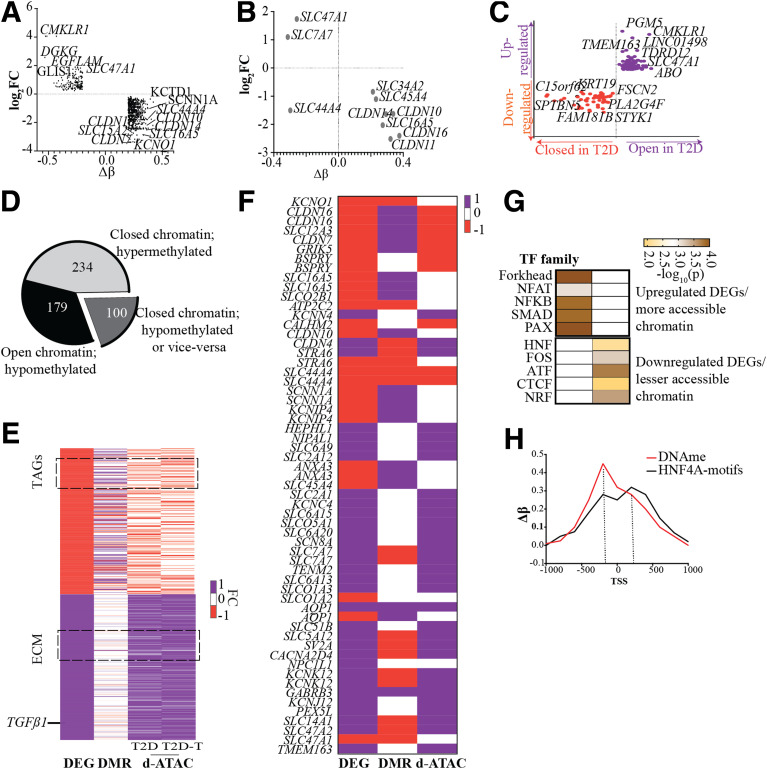

Figure 5.

Integrative analysis of RNA-seq, DNAme profile, and ATAC-seq data sets. A: Scatter plot showing correlation between DEGs (log2 fold change [FC]) and DMRs (Δβ) for T2D- vs. N-PTECs. Top genes associated (within 50 kb) with DEGs and DMRs are highlighted. B: Scatter plot showing correlation between candidate TAGs and associated DMRs within 50 kb. C: Quadrant plot showing correlation between DEGs and d-ATAC peaks in T2D- vs. N-PTECs. Top genes associated within 50 kb of d-ATAC are highlighted. D: Pie chart showing variation in ATAC-seq peaks (more closed or open chromatin) within hyper- or hypo-DMRs. E: Pseudocolor heat map showing T2D-associated key DEGs and corresponding DMRs and d-ATAC peaks. F: Pseudocolor heat map showing T2D-associated differential TAGs, DMRs, and d- ATAC. E and F: Heat maps are scaled from −1 to 1, where −1 indicates downregulation of gene expression, hypomethylation, and decreased ATAC peaks and 1 represents upregulation of gene expression, hypermethylation, and increased ATAC peaks. Orange indicates downregulation and purple, upregulation in panels C, E, and F. G: Enriched TF families for overlapping DMR and d-ATAC associated with DEGs. Color in each box represents −log10(p). H: Line plot of in silico analysis showing DNAme and HNF4A (TF binding site) motifs around DEGs in T2D vs. N.

Accordingly, >1,800 DEGs in T2D versus N, including 59 TAGs (CLDNs, SLCs), collagen, and TGFβ1 (all related to kidney function), showed association with DMRs and nearby d-ATACs, depicting negative correlations between DEGs and hyper-DNAme and positive correlations between DEGs and d-ATACs (Fig. 5E and F). Notably, Fig. 5F depicts positive correlations between DEGs and d-ATACs and a negative correlation with hypermethylation for the 59 differential TAGs. In addition, our data show differential regulation of 36 mitochondrial function–associated genes along with associated d-ATAC peaks and DMP/DMRs within 50 kb of their TSS (Supplementary Fig. 7). This is in line with the observed variation in OS in TGF-β1–treated T2D-PTECs, and the known role of mitochondrial dysfunction in DKD. Motif analysis of downregulated DEGs associated with DMRs and closed d-ATACs revealed associations with TF binding sites, such as HNF4A and CTCF, whereas upregulated DEGs and open d-ATACs displayed enrichment for SMAD3, PAX7, and forkhead box binding sites (Fig. 5G).

Reports have shown the potential role of HNF4A in the regulation of TAGs, especially SLCs and CLDNs (45,46). Binding sites for TFs like HNF4A in downregulated genes may become inaccessible in diabetes either because of hypermethylation or inaccessible chromatin. Our in silico analyses of overlapping d-ATACs and DMRs in T2D also revealed HNF4A motifs around DMRs (Fig. 5H). For example, SLC16A5, a downregulated TAG in T2D, showed hypermethylation and reduced chromatin accessibility in its promoter region (Supplementary Fig. 8A–C). Accessibility to HNF4A binding sites may be reduced in diabetes because of persistent epigenetic changes (DNAme and closed chromatin), leading to the downregulation of its target genes (e.g., SLC16A5). Conversely, SLC7A7, an upregulated TAG in T2D, showed persistent hypomethylation and enhanced chromatin accessibility in its promoter regions overlapping forkhead TFs (Supplementary Fig. 8A–C).

HNF4A as a Potential Regulator of Candidate TAGs

By motif analysis, we found enrichment of HNF4A binding sites in all three data sets (DEG, DMR, and d-ATAC), and evidence has shown that HNF4 regulates many TAGs (46) (Fig. 1H). Thus, we evaluated connections between epigenetic modulations and HNF4A in the deregulation of TAGs in T2D cells, using the demethylating agent 5-AZA for candidate TAGs CLDN10, CLDN14, CLDN16, SLC16A2, and SLC16A5. 5-AZA treatment (500 nmol/L for 72 h) led to an ∼50% reduction in global DNAme in both N- and T2D-PTECs (Fig. 6A) without affecting cell survival (Supplementary Fig. 9A). The HNF4A gene was hypomethylated in the gene body (Supplementary Fig. 9B) but showed no significant change in expression in T2D versus N (Supplementary Fig. 9C), although it was downregulated by TGF-β1 in N-T and T2D-T (Supplementary Fig. 9C). We did not observe any changes in HNF4A protein expression in T2D- versus N-PTECs, although slight decreases were observed in N-T and T2D-T (Supplementary Fig. 9D). 5-AZA treatment did not alter HNF4A protein expression in N- and T2D-PTECs (Supplementary Fig. 9D), implying that HNF4A binding, and not its expression, may regulate expression of TAGs. Locus-specific methylation PCR assays verified a significant reduction in T2D-induced promoter DNAme for CLDN10 and SLC16A5 after 5-AZA treatment (Fig. 6B). CLDN10 and SLC16A5 are representative TAGSs depicting hypermethylation (Supplementary Fig. 9E).

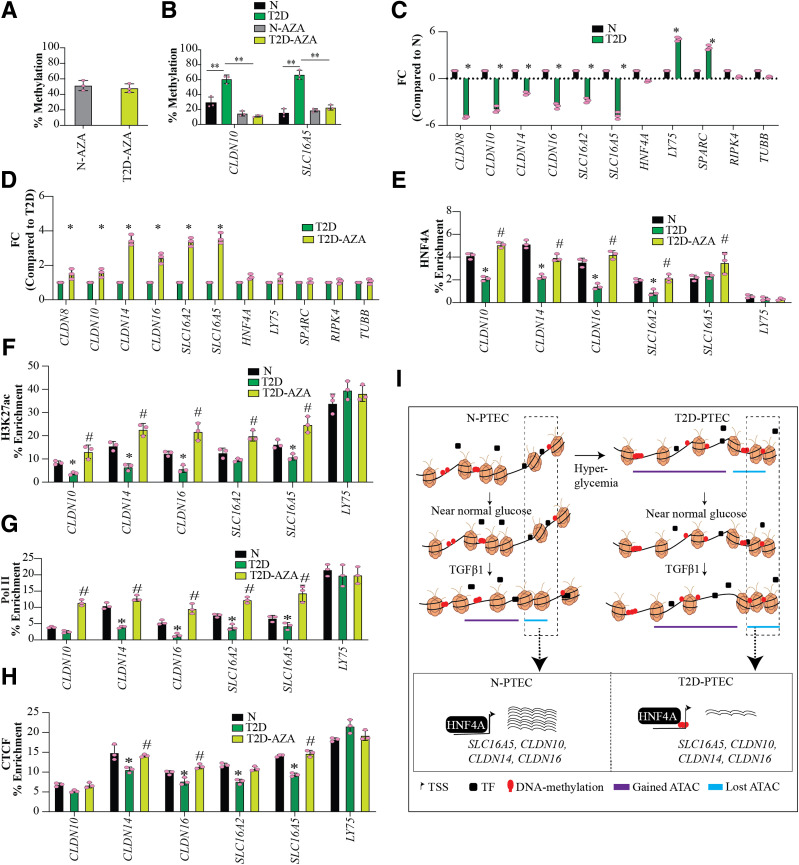

Figure 6.

HNF4A, a potential regulator of candidate SLCs and CLDNs. A: Bar plot showing percent reduction in global DNAme as measured using ELISA after 5-AZA treatment (500 nmol/L for 72 h) in N and T2D. B: Percent methylation measured in the promoters of CLDN10 and SLC16A5 in N, T2D, N-AZA, and T2D-AZA using QIAGEN EpiTect Methyl II PCR Assay. C and D: Fold change (FC) in expression of candidate TAGs (SLC, CLDN), HNF4A, and control genes as measured by RT-qPCR (n = 3). Bar = average FC compared with N (C) and T2D (D). E–H: ChIP-qPCR assays showing enrichment of HNF4A (E), H3K27ac (F), Pol II (G), and CTCF (H) in PTECs at gene promoters and overlapping DMRs. Error bars = SD. Individual data points are shown as dots. Bar = average FC (n = 3). Significance was calculated using ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005 for T2D vs. N; #P < 0.05 for T2D-AZA vs. T2D. I: Proposed schematic model for epigenetic memory in the persistent deregulation of candidate TAGs in T2D and the role of HNF4A TF. Hyperglycemia associated with diabetic conditions induces persistent epigenetic changes (i.e., epigenetic memory) in PTECs, which is represented by changes in DNAme or chromatin states (obtained by ATAC-seq). Our study shows that these epigenetic changes persist even when diabetic PTECs are cultured under normal glucose conditions in vitro. In addition, the persistent epigenetic changes render the diabetic PTECs more sensitive to secondary DKD-related stimuli like TGF-β1. Our data suggest that epigenetic changes associated with diabetes reduce the binding/enrichment of HNF4A upstream of key TAGs along with increased DNAme and reduced chromatin accessibility, hence reducing their transcription/expression in T2D. The purple line depicts the open or more accessible chromatin regions with DNA hypomethylation and greater chromatin accessibility in the promoters. The blue line depicts the closed regions with DNA hypermethylation and lower chromatin accessibility in the promoters.

The expression of candidate T2D-downregulated TAGs (Fig. 6C) increased after 5-AZA treatment (Fig. 6D), while control genes (hypomethylated [LY75, SPARC] or no DMR [HNF4A, RIPK4, TUBB] in T2D-PTECs) showed no changes. Next, ChIP-qPCRs for HNF4A at promoters of candidate SLCs and CLDNs (TAGs) showed decreased HNF4A binding in T2D versus N, which was reversed after 5-AZA treatment (Fig. 6E). Furthermore, ChIP-qPCR also showed a reversal of T2D-associated chromatin modulations, with increased enrichment for H3K27ac (a mark of active promoters, enhancers, and open chromatin) (Fig. 6F), Pol II (Fig. 6G), and CTCF (Fig. 6H) in the promoters of selected TAGs after 5-AZA treatment. The observed reversal in HNF4A binding and chromatin modifiers after 5-AZA treatment supports our hypothesis that in T2D, HNF4A binding upstream of TAGs like CLDN16, CLDN10, CLDN14, SLC16A2, and SLC16A5 is disrupted as a result of persistent epigenetic changes, including DNAme and chromatin accessibility.

Discussion

In this study, we used human T2D-PTECs and N-PTECs cultured in vitro under similar conditions to discern mechanisms underlying epigenetic memory of diabetes-induced renal tubular dysfunction. Using a multiomics approach, we identified the sustained deregulation of known and novel genes in T2D cells and related epigenetic changes. We found persistent gene expression and epigenetic (DNAme, chromatin accessibility) changes in T2D-PTECs versus N-PTECs, even when cultured long term in vitro under similar nondiabetic conditions. We also found that T2D-PTECs are more sensitive to diabetes/DKD-related secondary stimulus (TGF-β1), depicted by enhanced TGF-β1–regulated gene expression and epigenetic profiles in T2D-PTECs. These persistently deregulated signatures in T2D-PTECs might be associated with long-term renal dysfunction and chronic DKD, even after glycemic control.

Notably, our data revealed a previously unrecognized epigenetic memory and persistent deregulation of several TAGs in T2D. Although the role of the kidney and, particularly, proximal tubules in transport and absorption of nutrients (e.g., glucose, amino acids, cations) and filtration of wastes (e.g., creatinine, ammonia) are well known, little is known about the epigenetic regulation of various TAGs (47). Many SLCs are therapeutic targets for T2D, with SLC5A1 and SLC5A2 and the sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors among the best studied (48). Further investigation of other TAGs identified here could provide a rationale for evaluating their therapeutic potential for DKD and metabolic memory in the future.

We found persistent deregulation (transcriptional and epigenetic) of several key TAGs, such as CLDN16, CLDN10, CLDN14, SLC16A2, and SLC16A5, in T2D-PTECs and their association with TFs, such as HNF4A and CTCF. Additionally, our data suggest that the diabetic state induces hypermethylation and closed chromatin at candidate TAGs, leading to disrupted HNF4A binding and their consequent downregulation. Altered binding of TFs like HNF4A as a result of long-lasting epigenetic changes during T2D could contribute to misregulation of key HNF4 target genes, chronic renal dysfunction, and DKD progression, even after glucose normalization. Our new data show that the deregulation of TAGs in T2D-PTECs may occur, at least in part, through epigenetic mechanisms. In particular, downregulation in T2D of CLDN16, a gene almost exclusively expressed in the kidney cortex on the basis of Genotype-Tissue Expression (49), may serve as a biomarker of DKD progression.

Our study also underscores a potential role for nuclear TFs like HNF4A and CTCF as crucial players in epigenetic memory. Although reports have shown interactions between HNF4A and DNAme (12,50), the functional role of HNF4A in epigenetic memory of DKD has not been investigated. Here, we propose a schematic model (Fig. 6I) that links epigenetic memory (persistent DNAme and chromatin changes) to enduring, long-lasting basal and inducible gene expression signatures in T2D-PTECs, even after glucose reduction.

We are aware of limitations, which include potential artifacts of the in vitro culture of PTECs. We also needed a glucose concentration of 7 mmol/L to maintain PTECs in culture, which is slightly above nondiabetic fasting glucose (∼5.5 mmol/L), although close to postprandial levels. Another limitation is our small sample size because of the limited availability of primary PTECs, especially from donors with T2D. However, the recapitulation of about one-third of DEGs (Fig. 1E) and DMRs (data not shown) from other studies with DKD tissues (12,14,17,38) provides assurance that despite the limitations, genomic changes and novel DEGs identified here can provide vital insights into epigenetic memory in DKD. Since donors of T2D-PTECs in our study have no known overt renal disease, it is possible that our observed changes are primarily driven by diabetes. However, correlation analysis with published DKD transcriptome studies using tubular or whole-kidney tissues showed that DEGs in our T2D-PTECs depict significant correlation (r2 = 0.33, P = 0.0005) (39) with DKD but not with hypertensive kidney disease unrelated to diabetes (r2 = 0.18, P = 0.21) (39) and with early DKD (r2 = 0.28, P = 0.0031) but not late DKD (r2 = 0.09, P = 0.1) (51). These data, along with our multiomics data showing that the T2D-PTECs retain DKD-like behavior with increased OS, and altered expression, chromatin accessibility, and DNAme at genes related to tubular function, even after culture under nondiabetic conditions, suggest that the T2D-PTECs have phenotypes reminiscent of early DKD.

In conclusion, our integrative study shows the existence of epigenetic memory in PTECs from subjects with T2D in regulating key genes, including previously unexplored TAGs, that might be associated with DKD. Exploration of mechanisms underlying sustained aberrant binding of TFs like HNF4-regulating genes in tubular cells could yield a deeper understanding of epigenetic memory and identify novel therapeutics for DKD.

Article Information

Acknowledgments. The authors thank Linda Lanting (Beckman Research Institute of City of Hope) for help with the cell culture and Jinhui Wang (Integrative Genomics Core, Beckman Research Institute) for support with sequencing.

Funding. This work was supported National Institutes of Health grants R01-DK-081705, R01-DK-058191, and R01-HL-106089 (to R.N.) and R00-HL-122368 and R01-HL-145170 (to Z.C.) as well as by the Ella Fitzgerald Foundation (to Z.C.). The research reported here included work performed in the Integrative Genomics Core supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P30-CA-033572.

Duality of Interest. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. A.B. performed the research. A.B., S.B., and R.N. analyzed the data and wrote and edited the manuscript. A.B., and R.N. designed the research. S.D., A.L., and Z.C. critically evaluated the data and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and discussed the manuscript. A.B. and R.N. are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

This article contains supplementary material online at https://doi.org/10.2337/figshare.12749288.

References

- 1.Alicic RZ, Rooney MT, Tuttle KR. Diabetic kidney disease: challenges, progress, and possibilities. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;12:2032–2045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forbes JM, Cooper ME. Mechanisms of diabetic complications. Physiol Rev 2013;93:137–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanwar YS, Sun L, Xie P, Liu FY, Chen S. A glimpse of various pathogenetic mechanisms of diabetic nephropathy. Annu Rev Pathol 2011;6:395–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nathan DM; DCCT/EDIC Research Group . The diabetes control and complications trial/epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications study at 30 years: overview. Diabetes Care 2014;37:9–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1577–1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chalmers J, Cooper ME. UKPDS and the legacy effect. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1618–1620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kato M, Natarajan R. Epigenetics and epigenomics in diabetic kidney disease and metabolic memory. Nat Rev Nephrol 2019;15:327–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Urso A, Brickner JH. Epigenetic transcriptional memory. Curr Genet 2017;63:435–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper ME, El-Osta A. Epigenetics: mechanisms and implications for diabetic complications. Circ Res 2010;107:1403–1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bechtel W, McGoohan S, Zeisberg EM, et al. Methylation determines fibroblast activation and fibrogenesis in the kidney. Nat Med 2010;16:544–550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wing MR, Devaney JM, Joffe MM, et al.; Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study . DNA methylation profile associated with rapid decline in kidney function: findings from the CRIC study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014;29:864–872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marumo T, Yagi S, Kawarazaki W, et al. Diabetes induces aberrant DNA methylation in the proximal tubules of the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;26:2388–2397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Z, Miao F, Paterson AD, et al.; DCCT/EDIC Research Group . Epigenomic profiling reveals an association between persistence of DNA methylation and metabolic memory in the DCCT/EDIC type 1 diabetes cohort. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016;113:E3002–E3011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu AY, Tin A, Schlosser P, et al. Epigenome-wide association studies identify DNA methylation associated with kidney function. Nat Commun 2017;8:1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keating ST, van Diepen JA, Riksen NP, El-Osta A. Epigenetics in diabetic nephropathy, immunity and metabolism. Diabetologia 2018;61:6–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gluck C, Qiu C, Han SY, et al. Kidney cytosine methylation changes improve renal function decline estimation in patients with diabetic kidney disease. Nat Commun 2019;10:2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park J, Guan Y, Sheng X, et al. Functional methylome analysis of human diabetic kidney disease. JCI Insight 2019;4:e128886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rowland J, Akbarov A, Eales J, et al. Uncovering genetic mechanisms of kidney aging through transcriptomics, genomics, and epigenomics. Kidney Int 2019;95:624–635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sieber KB, Batorsky A, Siebenthall K, et al. Integrated functional genomic analysis enables annotation of kidney genome-wide association study loci. J Am Soc Nephrol 2019;30:421–441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schnaper HW, Jandeska S, Runyan CE, et al. TGF-beta signal transduction in chronic kidney disease. Front Biosci 2009;14:2448–2465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sasaki K, Doi S, Nakashima A, et al. Inhibition of SET domain-containing lysine methyltransferase 7/9 ameliorates renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;27:203–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun G, Reddy MA, Yuan H, Lanting L, Kato M, Natarajan R. Epigenetic histone methylation modulates fibrotic gene expression. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;21:2069–2080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuan H, Reddy MA, Sun G, et al. Involvement of p300/CBP and epigenetic histone acetylation in TGF-β1-mediated gene transcription in mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2013;304:F601–F613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013;29:15–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014;15:550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aryee MJ, Jaffe AE, Corrada-Bravo H, et al. Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive Bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics 2014;30:1363–1369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tian Y, Morris TJ, Webster AP, et al. ChAMP: updated methylation analysis pipeline for Illumina BeadChips. Bioinformatics 2017;33:3982–3984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buenrostro JD, Giresi PG, Zaba LC, Chang HY, Greenleaf WJ. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat Methods 2013;10:1213–1218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langmead B, Wilks C, Antonescu V, Charles R. Scaling read aligners to hundreds of threads on general-purpose processors. Bioinformatics 2019;35:421–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol 2008;9:R137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell 2010;38:576–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landt SG, Marinov GK, Kundaje A, et al. ChIP-seq guidelines and practices of the ENCODE and modENCODE consortia. Genome Res 2012;22:1813–1831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015;347:1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van der Hauwaert C, Savary G, Gnemmi V, et al. Isolation and characterization of a primary proximal tubular epithelial cell model from human kidney by CD10/CD13 double labeling. PLoS One 2013;8:e66750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reddy MA, Natarajan R. Recent developments in epigenetics of acute and chronic kidney diseases. Kidney Int 2015;88:250–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suryavanshi SV, Kulkarni YA. NF-κβ: a potential target in the management of vascular complications of diabetes. Front Pharmacol 2017;8:798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barzegar-Fallah A, Alimoradi H, Razmi A, Dehpour AR, Asgari M, Shafiei M. Inhibition of calcineurin/NFAT pathway plays an essential role in renoprotective effect of tropisetron in early stage of diabetic nephropathy. Eur J Pharmacol 2015;767:152–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woroniecka KI, Park AS, Mohtat D, Thomas DB, Pullman JM, Susztak K. Transcriptome analysis of human diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes 2011;60:2354–2369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beckerman P, Qiu C, Park J, et al. Human kidney tubule-specific gene expression based dissection of chronic kidney disease traits. EBioMedicine 2017;24:267–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson PC, Wu H, Kirita Y, et al. The single-cell transcriptomic landscape of early human diabetic nephropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:19619–19625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muto S Physiological roles of claudins in kidney tubule paracellular transport. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2017;312:F9–F24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu AS Claudins and the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;26:11–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Sun K, Meng Z, Chen L. The SLC transporter in nutrient and metabolic sensing, regulation, and drug development. J Mol Cell Biol 2019;11:1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu C, Zhu L, Chan T, et al. The altered renal and hepatic expression of solute carrier transporters (SLCs) in type 1 diabetic mice. PLoS One 2015;10:e0120760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prestin K, Wolf S, Feldtmann R, et al. Transcriptional regulation of urate transportosome member SLC2A9 by nuclear receptor HNF4α. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2014;307:F1041–F1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farkas AE, Hilgarth RS, Capaldo CT, et al. HNF4α regulates claudin-7 protein expression during intestinal epithelial differentiation. Am J Pathol 2015;185:2206–2218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu H, Lai CF, Chang-Panesso M, Humphreys BD. Proximal tubule translational profiling during kidney fibrosis reveals proinflammatory and long noncoding RNA expression patterns with sexual dimorphism. J Am Soc Nephrol 2020;31:23–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin L, Yee SW, Kim RB, Giacomini KM. SLC transporters as therapeutic targets: emerging opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2015;14:543–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carithers LJ, Ardlie K, Barcus M, et al.; GTEx Consortium . A novel approach to high-quality postmortem tissue procurement: the GTEx project. Biopreserv Biobank 2015;13:311–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morgado-Pascual JL, Marchant V, Rodrigues-Diez R, et al. Epigenetic modification mechanisms involved in inflammation and fibrosis in renal pathology. Mediators Inflamm 2018;2018:2931049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fan Y, Yi Z, D’Agati VD, et al. Comparison of kidney transcriptomic profiles of early and advanced diabetic nephropathy reveals potential new mechanisms for disease progression. Diabetes 2019;68:2301–2314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]