Fluoroquinolones (FQs) are often preferred as oral step-down therapy for bloodstream infections (BSIs) due to favorable pharmacokinetic parameters; however, they are also associated with serious adverse events. The objective of this study was to compare clinical outcomes for patients who received an oral FQ versus an oral beta-lactam (BL) as step-down therapy for uncomplicated streptococcal BSIs. This multicenter, retrospective cohort study analyzed adult patients who completed therapy with an oral FQ or BL with at least one blood culture positive for a Streptococcus species from 1 January 2014 to 30 June 2019.

KEYWORDS: Streptococcus, bloodstream infection, oral step-down

ABSTRACT

Fluoroquinolones (FQs) are often preferred as oral step-down therapy for bloodstream infections (BSIs) due to favorable pharmacokinetic parameters; however, they are also associated with serious adverse events. The objective of this study was to compare clinical outcomes for patients who received an oral FQ versus an oral beta-lactam (BL) as step-down therapy for uncomplicated streptococcal BSIs. This multicenter, retrospective cohort study analyzed adult patients who completed therapy with an oral FQ or BL with at least one blood culture positive for a Streptococcus species from 1 January 2014 to 30 June 2019. The primary outcome was clinical success, defined as the lack of all-cause mortality, recurrent BSI with the same organism, and infection-related readmission at 90 days. A multivariable logistic regression model for predictors of clinical failure was conducted. A total of 220 patients were included, with 87 (40%) receiving an FQ and 133 (60%) receiving a BL. Step-down therapy with an oral BL was noninferior to an oral FQ (93.2% versus 92.0%; mean difference, 1.2%; 90% confidence interval [CI], −5.2 to 7.8). No differences were seen in 90-day mortality, 90-day recurrent BSI, 90-day infection-related readmission, or 90-day incidence of Clostridioides difficile-associated diarrhea. Predictors of clinical failure included oral step-down transition before day 3 (odds ratio [OR] = 5.18; 95% CI, 1.21, 22.16) and low-dose oral step-down therapy (OR = 2.74; 95% CI, 0.95, 7.90). Our results suggest that oral step-down therapy for uncomplicated streptococcal BSI with a BL is noninferior to an FQ.

INTRODUCTION

Bacterial bloodstream infections (BSIs) are a substantial cause of morbidity and mortality, accounting for approximately 85,000 deaths per year in North America and 157,000 deaths per year in Europe (1). Streptococcus species are among the most common causes of community-onset BSIs worldwide (2). Historically, BSIs have been treated with intravenous (i.v.) antimicrobials because they rapidly achieve peak drug levels. However, continuing i.v. therapy for the entire duration of treatment is associated with many disadvantages, including a longer hospital length of stay (LOS), increased health care costs, and adverse events associated with i.v. catheter use such as secondary infection and thrombosis (3, 4).

There is a growing body of evidence to support the use of oral antibiotics as step-down therapy for Gram-positive BSIs, although most studies to date have focused on Staphylococcus aureus (5–8). Limited studies of streptococcal BSI have demonstrated favorable outcomes with oral step-down after patients have reached clinical stability (9, 10). Fluoroquinolones (FQs) are often favored as an oral agent for step-down BSI treatment due to their high bioavailability compared to alternatives such as beta-lactams (BLs) (3). However, FQs have been associated with many safety concerns, including increased risks of tendinitis, tendon rupture, and aortic dissection (3, 11). Studies comparing the efficacies of FQs and BLs for BSI oral step-down therapy have almost exclusively been conducted in the setting of Gram-negative BSI, with some studies finding no difference in clinical outcomes and others showing an increased rate of treatment failure with BLs (12–14). Quinn et al. examined oral step-down for nonstaphylococcal Gram-positive BSIs, comparing the efficacy of high-bioavailability agents, including FQs, to that of BLs (15). No difference was seen in the rates of clinical failure, although that study was underpowered to detect such a difference.

The purpose of this study was to compare clinical outcomes for patients who received an oral FQ versus an oral BL as step-down therapy for uncomplicated streptococcal BSI. We hypothesized that clinical success for patients receiving an oral BL would be noninferior to that for patients receiving an oral FQ.

RESULTS

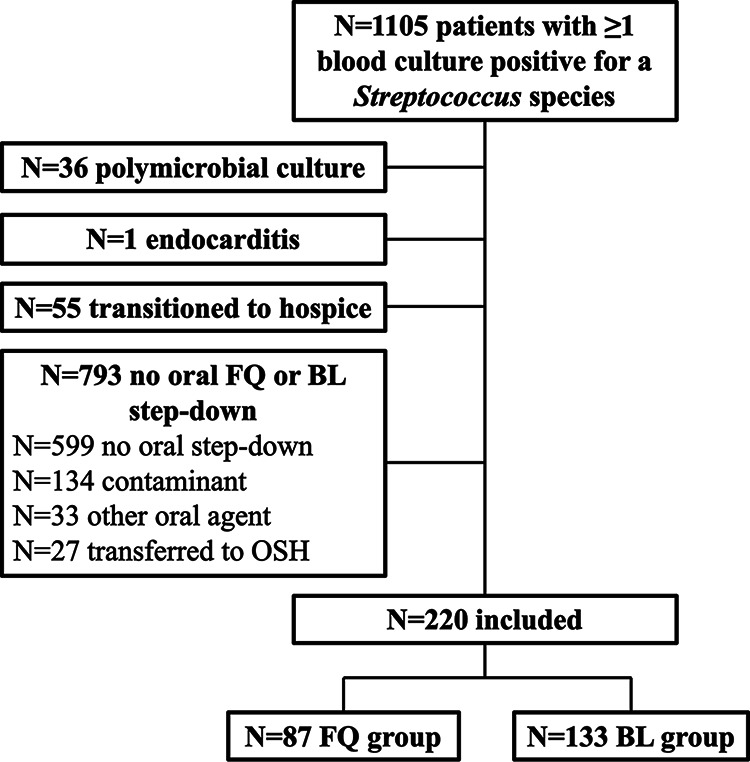

After screening 1,105 patients with streptococcal bacteremia, 220 patients (FQ = 87; BL = 133) were eligible for inclusion (Fig. 1). Over half of the patients were female (n = 120; 54.6%), with a mean age of 63.6 years. Patients in the FQ group were more likely to have a documented penicillin (17.2% versus 6.8%; P = 0.0148) or cephalosporin (6.9% versus 0%; P = 0.0034) allergy. Otherwise, both groups had similar baseline characteristics (Table 1).

FIG 1.

Development of the study cohort. BL, beta-lactam; FQ, fluoroquinolone; OSH, outside hospital.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study cohort (n = 220)

| Characteristica | Value for group |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FQ (n = 87) | BL (n = 133) | ||

| Median age (yr) (IQR) | 63 (18) | 66 (21) | 0.1613 |

| No. of female patients (%) | 52 (59.8) | 68 (51.1) | 0.2081 |

| Median Pitt bacteremia score (IQR) | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–2) | 0.1921 |

| Median Charlson comorbidity index (IQR) | 4 (2–6) | 5 (3–6) | 0.1386 |

| No. (%) of patients with ID consult | 71 (81.6) | 108 (81.2) | 0.9397 |

| No. (%) of patients with antibiotic allergy to: | |||

| Penicillin | 15 (17.2) | 9 (6.8) | 0.0148 |

| Cephalosporin | 6 (6.9) | 0 (0) | 0.0034 |

| Fluoroquinolone | 1 (1.1) | 3 (2.3) | 1 |

| No. (%) of patients with community-acquired infection | 84 (96.6) | 127 (95.5) | 1 |

| No. (%) of patients with source of infection | |||

| Skin and skin structure | 19 (21.8) | 60 (45.1) | 0.0004 |

| Respiratory | 54 (62.1) | 32 (24.1) | <0.001 |

| Other | 14 (16.1) | 41 (30.8) | 0.0103 |

| Urinary | 1 (1.1) | 2 (1.5) | |

| Intra-abdominal | 4 (4.6) | 8 (6.0) | |

| Oropharyngeal | 3 (3.4) | 10 (7.5) | |

| Surgical site | 0 (0) | 3 (2.3) | |

| Gynecological | 1 (1.1) | 4 (3.0) | |

| Unknown | 5 (5.7) | 13 (9.8) | |

| Sinusitis | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| No. (%) of patients with complicated infection | 7 (8.0) | 19 (14.3) | 0.1610 |

| No. (%) of patients with organism susceptible to empirical therapy | 85 (97.7) | 133 (100) | 0.1553 |

| Median time to oral step-down (days) (IQR) | 5.3 (4.1–7.8) | 5.8 (4.2–8.2) | 0.2347 |

| No. (%) of patients with oral step-down at <3 days | 4 (4.6) | 8 (6.0) | 0.7676 |

| No. (%) of patients with dose | 0.0547 | ||

| Low | 15 (17.2) | 38 (28.6) | |

| High | 72 (82.8) | 95 (71.4) | |

| Median time to blood culture clearance (days) (IQR) | 1.40 (1.11–1.82) | 1.47 (1.10–1.84) | 0.3536 |

| Median total treatment duration (days) (IQR) | 14 (13–15) | 14 (12–16) | 0.9831 |

| No. (%) of patients with treatment duration of <10 days | 2 (2.3) | 4 (3.0) | 1 |

| No. (%) of patients with organism isolated | <0.001 | ||

| Viridans group Streptococcus | 12 (13.8) | 20 (15.0) | |

| S. pneumoniae | 49 (56.3) | 26 (19.5) | |

| S. pyogenes | 7 (8.0) | 31 (23.3) | |

| S. dysgalactiae | 5 (5.7) | 22 (16.5) | |

| S. anginosus group | 1 (1.1) | 11 (8.3) | |

| S. agalactiae | 13 (14.9) | 23 (17.3) | |

| No. (%) of patients with i.v. therapy with: | <0.001 | ||

| Ceftriaxone | 54 (62.1) | 78 (58.6) | |

| Cefazolin | 0 (0) | 11 (8.3) | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 4 (4.6) | 15 (11.3) | |

| Ampicillin-sulbactam | 0 (0) | 13 (9.8) | |

| Fluoroquinolone | 14 (6.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Other beta-lactamb | 6 (2.7) | 7 (3.2) | |

| Other non-beta-lactamc | 9 (4.1) | 9 (4.1) | |

ID, infectious disease.

Other beta-lactams included cefepime, ampicillin, ertapenem, meropenem, or penicillin G.

Other non-beta-lactams included vancomycin or linezolid.

The most common organism isolated was Streptococcus pneumoniae (34.1%), followed by Streptococcus pyogenes (17.3%) and Streptococcus agalactiae (16.4%). Most patients in the FQ group had a respiratory source of infection (62.1%), while skin and skin structure infections were the most common source in the BL group (45.1%). Levofloxacin (58.6%) was the most common step-down agent in the FQ group, with amoxicillin-clavulanate (45.9%) being the most common in the BL group (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Oral step-down regimens

| Regimena | No. of patients | No. of patients included in the high-dose group based on renal dosing adjustment |

|---|---|---|

| High dose | ||

| Amoxicillin at 875 mg Q12H | 2 | |

| Amoxicillin at 1,000 mg Q8H | 3 | |

| Amoxicillin at 1,000 mg Q12H | 1 | |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate at 875-125 mg Q12H | 49 | |

| Cefadroxil at 500 mg Q12H | 3 | |

| Cefadroxil at 1,000 mg Q12H | 1 | |

| Cefdinir at 300 mg Q12H | 14 | |

| Cefpodoxime at 200 mg Q12H | 1 | |

| Cefuroxime at 500 mg Q12H | 5 | |

| Cephalexin at 1,000 mg Q6H | 3 | |

| Cephalexin at 1,000 mg Q8H | 4 | |

| Levofloxacin at 750 mg Q24H | 28 | |

| Moxifloxacin at 400 mg Q24H | 36 | |

| Penicillin V at 500 mg Q6H | 3 | |

| Penicillin V at 500 mg Q8H | 2 | |

| Low dose | ||

| Amoxicillin at 500 mg Q8H | 7 | |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate at 500-125 mg Q24H | 2 | 2 |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate at 500-125 mg Q12H | 10 | 1 |

| Cefdinir at 300 mg Q24H | 1 | 1 |

| Cephalexin at 500 mg Q6H | 10 | |

| Cephalexin at 500 mg Q8H | 7 | |

| Cephalexin at 500 mg Q12H | 3 | 1 |

| Cephalexin at 1,000 mg Q12H | 1 | |

| Levofloxacin at 500 mg Q24H | 16 | |

| Levofloxacin at 500 mg Q48H | 2 | 2 |

| Levofloxacin at 750 mg Q48H | 5 | 5 |

| Penicillin V at 500 mg Q12H | 1 | |

QxH, every x hours.

The majority of patients received i.v. therapy with ceftriaxone (60.0%), followed by piperacillin-tazobactam (8.6%). Blood culture clearance was documented via negative follow-up blood cultures in 83.2% of patients. The median time to blood culture clearance was 1.44 days (interquartile range [IQR], 1.11 to 1.84 days). Patients were transitioned to oral therapy after a median of 5.67 days (IQR, 4.10 to 8.07 days), and the median total treatment duration was 14 days (IQR, 13 to 16 days). Forty-four patients (20%) received at least one dose of their oral step-down antibiotic before hospital discharge.

The primary outcome of clinical success was achieved by 92.0% of patients in the FQ group compared to 93.2% of patients in the BL group, and oral step-down with a BL was found to be noninferior to an FQ (mean difference, 1.2%; 90% confidence interval [CI], −5.2 to 7.8; P < 0.0001). The most common reason for clinical failure was infection-related readmission (6.9% versus 6.8%; P = 0.9702). All-cause mortality (2.3% versus 0%; P = 0.1553), BSI recurrence (1.2% versus 1.5%; P = 1), development of Clostridioides difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD) (3.5% versus 3.0%; P = 1), and antibiotic-associated adverse events were also similar (Table 3). In a subgroup of 75 patients with S. pneumoniae BSI, clinical success was achieved by 93.9% of patients in the FQ group compared to 88.5% of patients in the BL group (P = 0.4118).

TABLE 3.

Clinical outcomes compared between fluoroquinolone and beta-lactam oral step-down therapies (n = 220)

| Characteristica | No. (%) of patients |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FQ group (n = 87) | BL group (n = 133) | ||

| Clinical success | 80 (92.0) | 124 (93.2) | 0.7209 |

| Reason for clinical failure | |||

| 90-day all-cause mortality | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 0.1553 |

| 90-day infection-related readmission | 6 (6.9) | 9 (6.8) | 0.9702 |

| 90-day recurrent BSI with the same organism | 1 (1.2) | 2 (1.5) | 1 |

| C. difficile-associated diarrhea | 3 (3.5) | 4 (3.0) | 1 |

| Antibiotic-associated adverse events | |||

| Diarrhea | 3 (3.4) | 5 (3.8) | |

| Rash | 2 (2.3) | 3 (2.3) | |

| QT interval prolongation | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Nausea/vomiting | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | |

BSI, bloodstream infection.

The characteristics listed in Table 1 that were significantly associated with the outcome (P < 0.05) in the bivariate analysis were penicillin allergy, cephalosporin allergy, organism, i.v. therapy, and source of infection. Oral step-down at <3 days, low-dose oral step-down therapy, and the total treatment duration were deemed clinically significant and were included in the regression analysis as well. Regression results identified 2 variables as predictors of clinical failure: oral step-down at <3 days (odds ratio [OR] = 5.18; 95% CI, 1.21, 22.16) and low-dose oral step-down therapy (OR = 2.74; 95% CI, 0.95, 7.90) as positive predictors of clinical failure (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Backward elimination multivariable logistic regression analysis for predicting clinical failure (n = 220)a

| Variable | β | SE | OR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral step-down at <3 days | 1.6451 | 0.7415 | 5.182 | 1.211–22.162 | 0.0265 |

| Low-dose oral step-down regimen | 1.0068 | 0.5411 | 2.737 | 0.948–7.903 | 0.948 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first adequately powered study to compare the clinical outcomes of patients who received FQ versus BL oral step-down therapy for uncomplicated streptococcal BSI. Our findings demonstrate that oral step-down with a BL is noninferior to an FQ, with clinical success rates of 93% and 92%, respectively.

Establishing the noninferiority of BLs as oral step-down therapy for uncomplicated streptococcal BSI allows for the expansion of oral step-down options for this indication. FQs have historically been favored as oral step-down agents for BSI due to their high bioavailability; however, FQs are associated with serious adverse effects (3, 11). Compared to oral BLs, FQs have a broad spectrum of activity, which places patients at a higher risk for CDAD (16). No difference in the incidence of CDAD was seen in our cohort, although the study was not powered to evaluate this outcome. Our findings are similar to those of Quinn et al., who evaluated oral step-down therapy for nonstaphylococcal Gram-positive BSIs, a majority of which were caused by streptococcal species (15). Those authors found no difference in clinical failure when comparing high- and low-bioavailability agents, although that study was underpowered to detect such a difference.

It is notable that patients with S. pneumoniae BSI were more likely to receive an FQ than a BL in our cohort. Providers may not have felt as comfortable using a BL for these patients given that S. pneumoniae is more likely to be BL resistant or intermediate than other streptococcal species (17). We found no difference in the rates of clinical success among a subgroup of patients with S. pneumoniae BSI when comparing FQ to BL oral step-down. However, this subgroup analysis may not have been adequately powered to detect such a difference.

Oral step-down transition prior to day 3 was a significant predictor of clinical failure in our multivariable logistic regression model. Clinical stability should also be evaluated when determining when to transition to oral therapy. One small study of patients with Streptococcus pneumoniae BSI from a respiratory source demonstrated favorable outcomes among patients who were switched to oral therapy after they showed symptomatic improvement, were afebrile for at least 8 h, had a normalizing white blood cell count, and were able to tolerate oral medications (9). Although we are not able to clearly define the minimum duration of i.v. therapy prior to oral step-down, transitioning to oral therapy may be a reasonable approach after clinical stability is achieved with at least 3 days of i.v. therapy.

The use of a low-dose oral step-down regimen was predictive of clinical failure in our automated multivariable logistic regression model but did not retain statistical significance in our final logistic regression model containing only significant predictors identified in the automated model. We distinguished high- versus low-dose oral step-down regimens based on recommended dosing for severe infections, although it is unclear if this distinction is clinically meaningful for streptococcal isolates, which generally have low MICs (17). A meta-analysis comparing oral step-down options for Gram-negative BSI found a higher rate of BSI recurrence among patients transitioned to BLs, which the authors concluded may have been due to suboptimal BL dosing (14). One study included in this meta-analysis found a higher rate of clinical failure when lower-bioavailability agents were used (12). We observed clinical failures with both low-dose BLs and FQs, suggesting that the dosing regimen selected may be a more important consideration than the bioavailability of the agent. A high-dose BL regimen may provide a probability of pharmacokinetic target attainment similar to that with an FQ for streptococcal BSI given that streptococcal species have lower MICs than Enterobacterales (17). High-dose BL regimens may require up to four doses per day, and it is unknown how such frequent dosing might impact patient adherence.

The median total treatment duration was 14 days in both the FQ and BL groups. Previous studies support the use of shorter treatment durations for Gram-negative BSIs (18, 19). However, we were unable to assess the applicability of a shortened treatment duration strategy to streptococcal BSI.

Our study has several important limitations, including its retrospective design. Severity-of-illness scores (Charlson comorbidity index and Pitt bacteremia score) were evaluated in order to account for potential selection bias, and no differences were seen between the two groups. We were unable to assess adherence to oral step-down therapy after hospital discharge, and we cannot capture cases of clinical failure among patients who sought care outside our health system. We chose to compare FQ and BL oral step-down therapies because these are the two most common antibiotic classes used for oral step-down of BSI within our health system. Other antibiotics such as sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, clindamycin, or linezolid may also have utility as oral step-down therapy for streptococcal BSI. Our study did not compare outcomes between patients whose regimens included oral step-down therapy and those who completed treatment with intravenous therapy, and we are therefore unable to comment on which patients should or should not receive oral step-down therapy for streptococcal BSI. Rates of clinical success may have been overestimated in our cohort because patients with a good prognosis may have been more likely to be considered for oral step-down therapy.

Although a randomized, prospective study is needed to confirm these findings, oral step-down therapy with either an FQ or a BL may be reasonable for patients with uncomplicated streptococcal BSI. We recommend utilizing a high-dose oral step-down regimen with a total treatment duration of at least 14 days.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

This was a retrospective study of inpatients ≥18 years of age with at least one blood culture positive for a Streptococcus species from 1 January 2014 to 30 June 2019 at seven Advocate Aurora Health hospitals located in the Chicago, IL, area. Patients were included if they were treated for a streptococcal BSI and completed treatment with an oral FQ or an oral BL. Patients were excluded if they had a polymicrobial BSI, had a BSI complicated by endocarditis or central nervous system infection, or transitioned to hospice care before completing treatment for their BSI. Manual chart review was performed to confirm subject eligibility and gather baseline characteristics, treatment information, and clinical outcomes. The organization’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewed the study, determined it to be exempt from IRB oversite, and waived informed consent.

Outcomes.

The primary endpoint was clinical success, defined as the absence of all-cause mortality, BSI recurrence with the same organism, and infection-related readmission at 90 days from the date of collection of the first positive blood culture. Secondary endpoints included individual components of the primary endpoint, the incidence of 90-day CDAD, and antibiotic-associated adverse effects at 30 days from hospital discharge. A 90-day follow-up period was chosen based on a consensus statement (20).

Definitions.

Infection-related readmission was defined as readmission due to the lack of clinical improvement as determined by the treating provider, a relapse of the same infection, or an adverse event associated with antibiotic treatment. A positive C. difficile PCR test and provider documentation of diarrhea served as confirmation of CDAD. Complicated infection was defined as bone or joint infection, the formation of an abscess, necrotizing fasciitis, or a pleural effusion that required drainage. The total duration of therapy was calculated by using the day of the first negative follow-up blood culture as day 1 and including planned days of therapy postdischarge, if applicable. If no follow-up blood culture was ordered, the first day of therapy was considered day 1. Oral step-down regimens were classified as either low or high dose based on recommended dosing for severe infections.

Statistical analysis.

A sample size of 100 was calculated to evaluate noninferiority of the two oral step-down groups regarding clinical success using an α value of 0.05, a β value of 0.2 (80% power), an estimated clinical success rate of 90% for both groups, and a noninferiority margin of 15%. The estimated rate of clinical success and the noninferiority margin were based on previous studies of oral step-down therapy for Gram-negative and nonstaphylococcal Gram-positive BSI (10, 12, 13, 15). SAS statistical software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used to conduct all analyses.

Descriptive statistics were analyzed for all continuous and categorical data. Categorical data were reported as frequencies and percentages, and continuous data were assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and reported as means ± standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). A bivariate analysis was conducted to assess the relationship between the oral step-down groups and all other variables collected. Corresponding odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were also calculated. Pearson chi-square or Fisher’s exact test P values were assessed to determine whether the associations for categorical variables were statistically significant, while t test and Mann-Whitney U test P values were calculated to compare means for continuous variables. A two-sided P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests. Multivariable logistic regression was conducted to assess predictors of clinical failure while controlling for potential confounders and/or effect modifiers. Backward elimination model selection was performed in SAS with a significance level to stay (SLS) set to an α value 0.10. Eight variables were initially included, five of which were selected based on statistical significance (P < 0.05) in the bivariate analysis and three of which were selected based on clinical significance. Automated backward elimination produced a final model with three identified predictors. A manual model-building process with the three identified predictors was then conducted to evaluate estimates and verify the importance of these predictors in the model. It was decided to eliminate one predictor due to the small number of clinical failures. The removal of one predictor that had little clinical value was decided in order to have a more stable, parsimonious model with a minimal number of variables and the best model fit that would reliably predict clinical failure.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Anne Rivelli for her contributions to this work.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goto M, Al-Hasan MN. 2013. Overall burden of bloodstream infection and nosocomial bloodstream infection in North America and Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect 19:501–509. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laupland KB, Church DL. 2014. Population-based epidemiology and microbiology of community-onset bloodstream infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 27:647–664. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00002-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hale AJ, Snyder GM, Ahern JW, Eliopoulos G, Ricotta DN, Alston WK. 2018. When are oral antibiotics a safe and effective choice for bacterial bloodstream infections? An evidence-based narrative review. J Hosp Med 13:328–335. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li HK, Agweyu A, English M, Bejon P. 2015. An unsupported preference for intravenous antibiotics. PLoS Med 12:e1001825. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shorr AF, Kunkel MJ, Kollef M. 2005. Linezolid versus vancomycin for Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia: pooled analysis of randomized studies. J Antimicrob Chemother 56:923–929. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willekens R, Puig-Asensio M, Ruiz-Camps I, Larrosa MN, González-López JJ, Rodríguez-Pardo D, Fernández-Hidalgo N, Pigrau C, Almirante B. 2019. Early oral switch to linezolid for low-risk patients with Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections: a propensity-matched cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 69:381–387. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Itoh N, Hadano Y, Saito S, Myokai M, Nakamura Y, Kurai H. 2018. Intravenous to oral switch therapy in cancer patients with catheter-related bloodstream infection due to methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus: a single-center retrospective observational study. PLoS One 13:e0207413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jorgensen SCJ, Abdalhamid ML, Bhatia S, Shamim M-D, Rybak M. 2019. Sequential intravenous-to-oral outpatient antibiotic therapy for MRSA bacteraemia: one step closer. J Antimicrob Chemother 74:489–498. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramirez JA, Bordon J. 2001. Early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics in hospitalized patients with bacteremic community-acquired Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia. Arch Intern Med 161:848–850. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.6.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang A, Bor C, Chen J, Gandawidjaja M, Minejima E. 2018. Evaluation of the clinical efficacy and safety of oral antibiotic therapy for Streptococcus spp. bloodstream infections. Open Forum Infect Dis 5:S297–S298. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy210.838. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.FDA. 2018. FDA warns about increased risk of ruptures or tears in the aorta blood vessel with fluoroquinolone antibiotics in certain patients. FDA drug safety communications FDA, White Oak, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kutob LF, Justo JA, Bookstaver PB, Kohn J, Albrecht H, Al-Hasan MN. 2016. Effectiveness of oral antibiotics for definitive therapy of Gram-negative bloodstream infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents 48:498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mercuro NJ, Stogsdill P, Wungwattana M. 2018. Retrospective analysis comparing oral stepdown therapy for enterobacteriaceae bloodstream infections: fluoroquinolones versus β-lactams. Int J Antimicrob Agents 51:687–692. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Punjabi C, Tien V, Meng L, Deresinski S, Holubar M. 2019. Oral fluoroquinolone or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole vs. β-lactams as step-down therapy for Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis 6:ofz364. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quinn NJ, Sebaaly JC, Patel BA, Weinrib DA, Anderson WE, Roshdy DG. 2019. Effectiveness of oral antibiotics for definitive therapy of non-staphylococcal Gram-positive bacterial bloodstream infections. Ther Adv Infect Dis 6:2049936119863013. doi: 10.1177/2049936119863013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pepin J, Saheb N, Coulombe M-A, Alary M-E, Corriveau M-P, Authier S, Leblanc M, Rivard G, Bettez M, Primeau V, Nguyen M, Jacob C-E, Lanthier L. 2005. Emergence of fluoroquinolones as the predominant risk factor for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: a cohort study during an epidemic in Quebec. Clin Infect Dis 41:1254–1260. doi: 10.1086/496986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2020. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 30th ed Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chotiprasitsakul D, Han JH, Cosgrove SE, Harris AD, Lautenbach E, Conley AT, Tolomeo P, Wise J, Tamma PD, Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group. 2018. Comparing the outcomes of adults with Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia receiving short-course versus prolonged-course antibiotic therapy in a multicenter, propensity score-matched cohort. Clin Infect Dis 66:172–177. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yahav D, Franceschini E, Koppel F, Turjeman A, Babich T, Bitterman R, Neuberger A, Ghanem-Zoubi N, Santoro A, Eliakim-Raz N, Pertzov B, Steinmetz T, Stern A, Dickstein Y, Maroun E, Zayyad H, Bishara J, Alon D, Edel Y, Goldberg E, Venturelli C, Mussini C, Leibovici L, Paul M, Bacteremia Duration Study Group. 2019. Seven versus 14 days of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated Gram-negative bacteremia: a noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 69:1091–1098. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris PNA, McNamara JF, Lye DC, Davis JS, Bernard L, Cheng AC, Doi Y, Fowler VG, Kaye KS, Leibovici L, Lipman J, Llewelyn MJ, Munoz-Price S, Paul M, Peleg AY, Rodríguez-Baño J, Rogers BA, Seifert H, Thamlikitkul V, Thwaites G, Tong SYC, Turnidge J, Utili R, Webb SAR, Paterson DL. 2017. Proposed primary endpoints for use in clinical trials that compare treatment options for bloodstream infection in adults: a consensus definition. Clin Microbiol Infect 23:533–541. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]