Summary

Approaches to preventing or mitigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic have varied markedly between nations. We examined the approach up to August 2020 taken by two jurisdictions which had successfully eliminated COVID-19 by this time: Taiwan and New Zealand. Taiwan reported a lower COVID-19 incidence rate (20.7 cases per million) compared with NZ (278.0 per million). Extensive public health infrastructure established in Taiwan pre-COVID-19 enabled a fast coordinated response, particularly in the domains of early screening, effective methods for isolation/quarantine, digital technologies for identifying potential cases and mass mask use. This timely and vigorous response allowed Taiwan to avoid the national lockdown used by New Zealand. Many of Taiwan's pandemic control components could potentially be adopted by other jurisdictions.

Keywords: COVID-19, Public health, Epidemiology, Health policy, Infectious diseases, Global health

Introduction

Several disease outbreaks since 1900 have become global pandemics or threatened to become so. These events include the influenza pandemics of 1918 (H1N1), 1957 (H2N2), 1968 (H3N2) and 2009 (H1N1), the 1997 H5N1 influenza outbreak in Hong Kong, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV) in 2012, and Sudden Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV) in 2003. They have prompted many nations to develop protocols and infrastructure to manage and respond to such threats. During the current COVID-19 pandemic (caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus), nations have responded with varying public health interventions, such as border closures, quarantining and physical distancing.

The World Health Organization (WHO) was first alerted to a novel coronavirus outbreak by Chinese authorities on the 31 December 2019 [1]. In the following weeks, an increasing number of cases and deaths were reported outside China (the epicentre), prompting WHO to declare COVID-19 a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) on 30 January 2020 and a pandemic on 12 March 2020. By the end of August 2020, the SARS-CoV-2 virus had spread worldwide, with confirmed cases in 216 countries/areas/territories totalling over 25 million COVID-19 cases and over 844,000 deaths [2].

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been highly diverse for high-income jurisdictions. Amongst members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) mortality rates have varied substantially. For example, by the end of August 2020, Belgium had the highest mortality rate in the OECD and the United Kingdom, the highest mortality rate for an Anglophone nation, with 860.9 and 621.3 deaths per million population respectively [[2], [3]–4]. Comparatively, New Zealand has reported some of the lowest rate in the OECD, with 4.4 deaths per million population [5,6]. Low COVID-19 mortality rates up to August 2020 have also been observed amongst non-OECD jurisdictions closer to the epicentre of China, such as Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong, with 0.3, 4.7 and 11.9 deaths per million population respectively [2,[7], [8], [9], [10]–11].

As Taiwan currently has one of lowest mortality burdens amongst high-income jurisdictions and achieved elimination by April 2020 (no confirmed cases in the community) without a lockdown [12], we examined the response employed in this jurisdiction. We also examined a contrasting jurisdiction, New Zealand, which initially achieved elimination of community transmission of COVID-19 by May 2020 but had a particularly stringent lockdown [13], and a later lockdown after a subsequent outbreak in August 2020. Specifically, we aimed to identify public health interventions used in Taiwan which may be relevant to pandemic responses in other high-income countries during the current COVID-19 pandemic and in future pandemics.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

Relevant websites of Government Agencies were searched in Taiwan, including the Taiwan Centers for Disease Control [Taiwan CDC], the Ministry of Health and Welfare, the National Health Command centre [NHCC], and the Taiwan National Infectious Disease Statistics System [11,14,15]; and in New Zealand, including the Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora, and the Institute of Environmental Science and Research [ESR] [16,17]. PubMed, Google Scholar and preprint repositories (medRxiv and arXiv) were also searched for the period of 1 September 2019 to 1 September 2020. The search terms used were: ‘COVID-19′, ‘SARS-CoV-2 ‘, or ‘Coronavirus’; and ‘Taiwan’ or ‘New Zealand’ in the title and/or abstract of the article. We identified a total of 1030 articles in the databases, of which 998 were excluded as duplicates or not relevant, eg, clinical trials, modelling, genetic studies or case notes. We included a total of 32 articles which made reference to COVID-19 responses at a public health level and also described pre-COVID-19 public health preparations. In some instances, the authors drew on their direct involvement with the pandemic response in their respective countries.

Results

Summary of the COVID-19 status in Taiwan and New Zealand up to August 2020

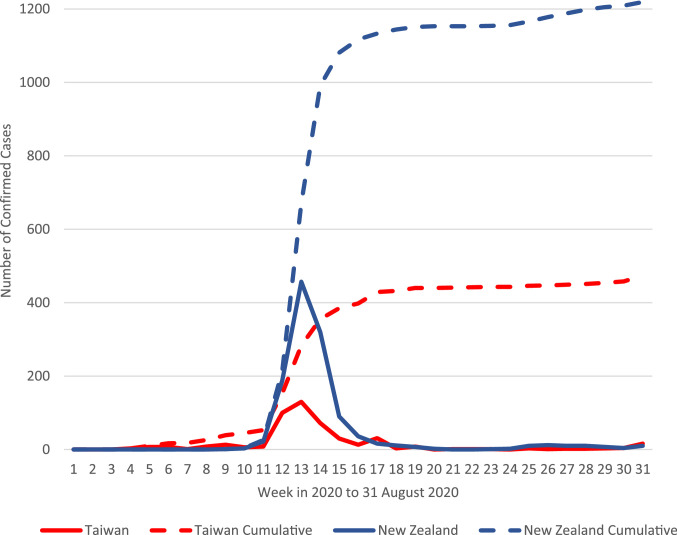

Taiwan announced its first confirmed case of COVID-19 on 21 January 2020, a 50+ year old woman returning to Taiwan from her teaching job in Wuhan [18,19]. New Zealand recorded its first case of COVID-19 on 28 February 2020, a woman in her 60 s who arrived on 26 February from Iran via Bali [20,21]. Both jurisdictions have now experienced the first wave of COVID-19 (Fig. 1), though New Zealand, after a period of elimination, has subsequently also experienced a localised outbreak in the Auckland region in August 2020.

Fig. 1.

Epidemic curve of weekly newly notified confirmed cases and cumulative total confirmed COVID-19 cases in Taiwan* and New Zealand** up to August 2020

*Taiwan confirmed cases based on date of notification as reported 31 August 2020 [14].

**New Zealand confirmed cases based on date notified as potential cases, as reported 31 August 2020 [21]. Further probable cases in New Zealand total n=351 (not included in total above) as of 31 August 2020. A probable case is defined as ‘one without a positive laboratory result, but which is treated like a confirmed case based on its exposure history and clinical symptoms’[5].

Table 1 details the main epidemiological features of COVID-19 in the two island jurisdictions.

Table 1.

Key epidemiological features of COVID-19 and jurisdiction-specific features in Taiwan and New Zealand.

| Taiwan* | New Zealand⁎⁎ | |

|---|---|---|

| General overview | ||

| Total population – 2020 estimate | 23 million [10] | 5 million [6] |

| Population density – 2020 and 2018 estimates | 652 people per km2[10] | 18.4 people per km2[22] |

| COVID-19 epidemiological characteristics up to 31 August 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total cases | 488 [11] | 1397⁎⁎[5] |

| Total confirmed cases per million population | 20.7 | 278.0 |

| Total deaths from COVID-19 | 7 [11] | 22 [5] |

| Total deaths from COVID-19 per million population | 0.3 | 4.4 |

| Case fatality risk (CFR) | 1.4% | 1.6% |

| Total tests performed for SARS-CoV-2 | 177,317 [12] | 766,626 [5] |

| Total tests per million population | 7520 | 152,562 |

| Test positive rate | 0.28% | 0.18% |

Only confirmed cases

Does not include probable cases [5]

As of August 2020, Taiwan had reported cases in 20 of its 22 administrative divisions, with the more geographically isolated eastern counties of Taitung and Hualien reporting no cases, whereas confirmed cases of COVID-19 were reported in all 20 District Health Board regions in New Zealand [5,14]. Taiwan had reported, up to 31 August 2020, a fairly even split of confirmed cases between sexes, with 51.2% recorded as male (250/488) [14], while New Zealand reported 47.0% (656/1397) confirmed cases amongst males up to 31 August 2020. [21] In both jurisdictions the highest proportion of confirmed cases was in the 20 to 29 years age group [14,21].

Public health interventions in Taiwan and New Zealand in response to COVID-19

Each jurisdiction used different approaches to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic (see Appendix 1 for detailed list of interventions). In Taiwan, several factors, including its proximity (130 km) to China (where the epicentre of Wuhan was); previous experience of the SARS pandemic in 2003; and its high population density triggered a coordinated national response in the early stages of the pandemic [23,24]. The Taiwan CDC in conjunction with the Central Epidemic Command centre (CECC) took the lead in managing the pandemic, as directed in the pre-COVID-19 pandemic plan for Taiwan. Established event-based systems alerted Taiwanese officials to the outbreak in China, prompting an immediate response, with screening of all airline passengers arriving from Wuhan. This screening was eventually extended to all passengers entering Taiwan from high risk areas/countries in late January, and eventually extended to all passengers regardless of their location of origin in early February [25]. In addition, by mid-March, entry to non-Taiwanese citizens or people with non-resident status was restricted. The existing legislation in the Taiwanese Infectious Disease Control Act 2007 enabled officials to access information that may aid in controlling/containing COVID-19 if necessary [26]. This legal framework enabled the travel history of individuals to be linked to their National Health Insurance (NHI) card so that hospitals could be aware and identify potential cases in real-time. Close contacts of confirmed cases or travellers returning from high-risk countries were required to be quarantined at home for 14 days. During this period, the person would be monitored through a combination of personal or government-dispatched phones and on occasion in-person checks [27]. A distinct feature of the Taiwan response was widespread use of face masks to reduce transmission from infected people (regardless of symptoms) as well as providing protection for wearers (mass masking). By February 2020, the start of the new semester for schools and high schools was delayed for two weeks, and by March there was a ban on large gatherings of 100 if indoors and 500 if outdoors. Notably, up to 31 August 2020, there were no stringent restrictions on movement and no local or national lockdown.

New Zealand's initial response followed its existing influenza pandemic plan revised in 2017, which was based on a mitigation strategy of ‘flattening the curve’ and delaying the epidemic peak to reduce the health impact of a pandemic [28]. Although entry restrictions and self-isolation/quarantine requirements were introduced for travellers from various COVID-19 hotspots from February onwards, cases in New Zealand were beginning to increase markedly by early March. The government signalled a new direction on 23 March when the Prime Minister announced a full lockdown of the country (at the highest Alert Level 4) which came into effect on 26 March, with exceptions for essential workers/businesses. This lockdown and partial lockdown at Alert Level 3 continued until 13 May. Most workplaces, schools and public meeting places were closed and travel stopped under Level 4 and highly restricted under Level 3. Implementation of the lockdown was supported by a national state of emergency, declared on 25 March, which, along with newly written law changes passed through Parliament, enabled special powers to address the pandemic situation.

Like Taiwan, New Zealand introduced border restriction to non-citizens/permanent residents from February onwards. New Zealand went down to its lowest Alert Level ‘1′ in June, with all arrivals (regardless of origin or symptomology) required to go into managed isolation/quarantine facilities for 14 days (mainly re-purposed hotels) and with a later introduced requirement for each individual to have two COVID-19 tests taken on days 3 and 12 of their time in quarantine [29].

Both jurisdictions have reported either potential outbreaks and/or clusters of cases of COVID-19. An outbreak occurred on a cruise ship that had previously visited Taiwan: the Diamond Princess (a well-publicised cruise-ship outbreak in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic) [30]. During this ship's visit to Taiwan, passengers were allowed to disembark on 31 January 2020 for a day trip. This day trip fell five days before the first case was confirmed on-board [26,31]. The Taiwan CDC, in response to news of Diamond Princess cases from Japan, published the locations that all the ship's passengers had visited, and issued instructions to those who might have been in contact with passengers to self-monitor and home-quarantine if judged necessary. Of the individuals in Taiwan who were deemed to be possible close contacts of the passengers, all tested negative to SARS-CoV-2 infection. A further cluster of infection in Taiwan in March 2020 occurred upon the Panshi fast combat support ship, with 36 confirmed cases. These infections resulted in extensive testing both on-board, and of potential contacts on land [11,32,33].

During New Zealand's first outbreak (from late February to May), there were 16 reported clusters of 10 or more cases of COVID-19 in New Zealand [34]. Of these clusters, many were outbreaks in aged-care facilities and from private social functions, with others linked to travel overseas, a secondary school and a cruise ship visit. After a period of successful elimination, a further outbreak occurred in Auckland City in August 2020. All the cases in this August outbreak were infected by the exact same strain of the virus, but New Zealand health officials have not yet identified the source of the this outbreak [35] (though a failure in a quarantine facility for incoming travellers seems most likely).

In both Taiwan and New Zealand, reported potential and confirmed outbreaks/clusters prompted public health officials to put similar infection control procedures in place. Response measures included contact tracing, testing and isolation of cases and quarantine of close contacts. Furthermore, both jurisdictions provided social/financial support during the COVID-19 pandemic and have existing universal health coverage.

Taiwan's COVID-19 response: defining features and differences from New Zealand's response that could plausibly have contributed to different outcomes

The responses of Taiwan and New Zealand to the COVID-19 pandemic varied as a result of pre-COVID infrastructure and planning, and may also have been influenced by the different timing of first confirmed cases in the respective jurisdictions (as shown in Appendix 1). These circumstances resulted in differential timing of the mandated use of case-based (eg, contact tracing and quarantine) and population-based (eg, face mask use and physical distancing) interventions. A recent modelling analysis using the detailed empirical case data in Taiwan concluded that population-based interventions likely played a major role in Taiwan's initial elimination efforts, and case-based interventions alone were not sufficient to control the epidemic [36]. Major features of the differing COVID-19 responses consist of the following:

-

•

Probably the most fundamental difference between the situation of Taiwan and New Zealand was that in Taiwan responsiveness to pandemic diseases and similar threats is embedded in its national institutions. Taiwan established a dedicated CDC in 1990 to combat the threat of communicable diseases. By contrast, the equivalent organisation in New Zealand (the NZ Communicable Disease Centre, a business unit within the Department of Health) was closed in 1992 with its functions transferred to a newly formed Crown Research Institute (ESR) and then contracted back to what became the Ministry of Health. In addition, Taiwan established a National Health Command centre (NHCC) in 2004 following the SARS epidemic. This agency, working in association with the CDC, was dedicated to responding to emerging threats, such as pandemics, and given the power to coordinate work across government departments and draw on additional personnel in an emergency.

-

•

Taiwan's pandemic response was largely mapped out through extensive planning as a result of the SARS pandemic in 2003, and was developed in such a way that it could be adapted to new pathogens. By contrast, New Zealand was reliant on its existing Influenza Pandemic Plan as a framework for responding to COVID-19, which has rather different disease characteristics compared with pandemic influenza, (although the plan does have some relevance for controlling any new respiratory pathogen).

-

•

As in many Asian countries that had experience with SARS, Taiwan had an established culture of face mask use by the public. It also has a very proactive policy of supporting production and distribution of masks to all residents, securing the supply, and providing universal access to surgical masks during the COVID-19 pandemic from February 2020 onwards. There were also official requirements to wear masks in confined indoor environments (notably subways), even during periods when there was no community transmission [37]. By contrast, health officials in New Zealand did not promote mass masking as part of resurgence planning until August, despite science-based advocacy from a broad base of public health and clinical experts [38].

-

•

Taiwan's well-developed pandemic approach, with extensive contact tracing through both manual and digital approaches, and access to travel histories, meant that potential cases could be identified and isolated relatively quickly [39]. This ability to track individuals or identify high-risk contacts resulted in fewer locally acquired cases. In contrast, New Zealand's contact tracing methods varied by local authority level and until May 2020 did not involve a centralised digital approach (e.g., did not have national approaches to the use of mobile phone applications and telecommunications data) [40]. New Zealand's resulting lockdown period began in March and effectively lasted for seven weeks (at Alert Levels 4 and 3).

-

•

Taiwanese officials began border management measures (initially health screening air passengers) the day the World Health Organization was informed of the outbreak in Wuhan (31 December 2019) and more extensive border screening of all arrivals occurred in late January, which coincided with the first case in Taiwan. New Zealand's first case occurred in late February 2020, and initially coincided with the first restrictions on foreign nationals from China. Both jurisdictions imposed wider entry restrictions to non-citizens in March 2020. The earlier introduction of entry restrictions and health screening in Taiwan is likely to have influenced the relatively lower case numbers in Taiwan compared with New Zealand up to August 2020 (20.7 vs 278.0 confirmed COVID-19 cases per million population respectively).

Discussion

With the extensive infrastructure it had established before COVID-19, it appears Taiwan was in a better position than New Zealand to respond effectively to the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite Taiwan's closer proximity to the source of the pandemic, and its high population density, it experienced a substantially lower case rate of 20.7 per million compared with New Zealand's 278.0 per million. Rapid and systematic implementation of control measures, in particular effective border management (exclusion, screening, quarantine/isolation), contact tracing, systematic quarantine/isolation of potential and confirmed cases, cluster control, active promotion of mass masking, and meaningful public health communication, are likely to have been instrumental in limiting pandemic spread. Furthermore, the effectiveness of Taiwan's public health response has meant that to date no lockdown has been implemented, placing Taiwan in a stronger economic position both during and post-COVID-19 compared with New Zealand, which had seven weeks of national lockdown (at Alert Levels 4 and 3). In comparison to Taiwan, New Zealand appeared to take a less vigorous response to this pandemic during its early stages, only introducing border management measures in a stepwise manner.

New Zealand's pandemic plan was entirely orientated to just pandemic influenza and so this limited its applicability to other pandemic diseases, such as COVID-19. It also had no established infrastructure for addressing a pandemic like COVID-19 until at least early March 2020. New Zealand's plan did include an initial “Stamp It Out” phase, but was largely orientated towards mitigation. However, early evidence from China indicated that a mitigation strategy for addressing COVID-19 may not have been optimal given the high transmissibility and the relatively high infection fatality ratio of SARS-CoV-2 infection (which probably would have resulted in thousands of deaths and overwhelmed the health system in a country such as New Zealand) [41]. There was also good evidence from China indicating that the COVID-19 pandemic could be contained with a sufficiently vigorous response [42]. These considerations, along with a need to protect Māori and Pacific populations (who already suffer high health inequalities from both endemic [43] and pandemic infectious diseases [44]), and the need to scale up testing and contact tracing, led to New Zealand's decision to implement border controls and physical distancing measures at high intensity (‘Lockdown’) to extinguish community transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

An assessment of contact tracing in Taiwan describes how the initial high transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 at, or just before, the onset of symptoms decreases with time, in contrast to the pattern of the SARS-CoV-1 outbreak in 2003 with initial transmissibility of cases remaining low until five days after onset of symptoms [45]. The authors suggest that relying on identifying symptomatic cases and contact tracing may not be sufficient as methods for containing COVID-19. A subsequent modelling analysis in Taiwan based on empirical data provided further evidence that case-based interventions (contact tracing and quarantine) alone would not be sufficient to contain the COVID-19 epidemic [36]. This issue may explain why the more aggressive approaches adopted by Taiwan and New Zealand have enabled them to initially eliminate SARS-CoV-2 in the community and avoid the high case numbers now occurring in countries that initially relied on a mitigation approach, such as the United Kingdom, the United States of America, and Sweden. New Zealand's initial period of elimination with no community transmission was sustained for 102 days from May 2020 [13]. It ended with an outbreak in August 2020, which emphasises the need for ongoing surveillance and resurgence planning in nations which have achieved periods of elimination.

Taiwan's management of and response to COVID-19 is not without concerns. For example, allowing Diamond Princess passengers into Taiwan drew criticism, as did the limitation of Taiwanese public communications during the pandemic being predominantly provided in Mandarin Chinese and sign language [31]. Although the Taiwan CDC website and some health education videos provide translation in several languages, just some of them include the languages of the 16 recognised indigenous Taiwanese Austronesian-speaking tribes, which may have limited access to important public health messages [31,46,47]. Daily press conferences in New Zealand have been delivered in English and included a New Zealand sign language interpreter. Translations of COVID-19 related materials on the main New Zealand COVID-19 related site (https://covid19.govt.nz) were also made available in Te Reo Māori (alongside other Te Reo Māori broadcasts), New Zealand Sign Language, and 26+ other languages.

So what can countries (in particular high-income countries) learn directly from the COVID-19 experience in Taiwan and New Zealand? There are many areas that need to be developed to inform the response to the current COVID-19 pandemic and to prepare for the next pandemic, which could be even more severe [48]. Our recommendations are as follows:

-

1

Establish or strengthen a dedicated national public health agency to manage both prevention and control of pandemics and other public health threats. Such an agency could take the form of a centre for disease control and prevention or a more broadly focused national public health agency, and would require the authority to coordinate other ministries/departments (such as Taiwan's CECC).

-

2

Formulate a generic pandemic plan that allows for responses to different disease agents with diverse characteristics.

-

3Provide further investment in resources and infrastructure that will allow a government to quickly respond to future disease threats. Taiwan strengthened its public health response through developing real-time surveillance methods pre-COVID-19 and already had a national alert system in place, unlike New Zealand. Specific recommendations include:

-

○Enhance national and regional disease and outbreak surveillance systems including sentinel surveillance and more specialised systems, such as wastewater testing [49].

-

○Develop effective border management policies and associated infrastructure that can be implemented quickly, such as the 31 December 2020 Taiwanese reaction to the outbreak notification with immediate air passenger health screening.

-

○Establish more robust quarantining rules and more secure facilities for incoming travellers. Previously in New Zealand, quarantining rules granted exemptions to customs and airline crew, although these have now been updated with more stringent guidelines [50].

-

○Further develop both conventional and digital solutions to contact tracing, and isolation/quarantine monitoring. Unlike Taiwan, New Zealand did not have these solutions substantially in place [40]. Indeed, a digital solution to contact tracing was only released in New Zealand in May 2020 and had limited functionality with initially poor uptake by the public.

-

○Develop an effective means of face mask distribution and promotion in case a border control failure occurs. The Taiwanese digital solution (such as the name-based mask distribution system, and distribution and sales controls implemented by the Taiwan CECC) avoided hoarding and enabled distribution to those most at need. This approach could also be applied and extended to medicine distribution for a future pandemic (eg, for antivirals).

-

○

-

4

Review workforce needs to support effective pandemic management and public health development more generally and enhance training programmes accordingly. One outcome could be establishment of a Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP) in countries such as New Zealand, which do not currently have one.

-

5Develop systems for evaluating and auditing pandemic responses, and exercising emerging infectious disease response capabilities.

-

○The Taiwan/New Zealand comparison indicates that it would be valuable to conduct an official enquiry into New Zealand's response to help shape the necessary changes to its laws, public health infrastructure, and institutions.

-

○Pandemic response systems can be tested by running regular exercises and simulations. However, such exercises will be ineffective unless recommendations arising from these initiatives are communicated and adopted [51].

-

○

-

6

Establish cultural, societal and legal acceptability for these pandemic response measures. There are legitimate concerns regarding the use of big data analytics, particularly with the use of digital methods in public health responses [52,53], and perhaps less cultural acceptability in some countries for regular face mask use as a public courtesy by people with any respiratory symptoms. Other populations may also be less inclined than Taiwan's citizens to accept the imposition of stringent interventions that limit personal rights and liberties. One way to explore these privacy concerns would be to run citizen juries, citizen panels, indigenous consultation, and surveys to clarify at what levels of pandemic severity populations would be willing to accept and comply with potential intrusions in privacy, such as using digital technology to aid contact tracing. Public health law needs to be updated to enable outbreak and pandemic control measures while balancing the needs to protect personal rights and liberties.

Conclusions

Taiwan's successful response to COVID-19 up to August 2020 has resulted in relatively low cases and mortality. This positive outcome reflected pre-COVID-19 preparation for disease outbreaks with a dedicated national public health agency and infrastructure including integrated manual and digital solutions to support the coordination of key functions. This pro-active response to COVID-19 in Taiwan is in contrast to the more reactive pandemic response in New Zealand. While some aspects of the Taiwan approach might not be acceptable in other jurisdictions, the potential social and economic benefits of avoiding a lockdown might alleviate some objections. Therefore, the Taiwanese model warrants further examination for transferable elements that could improve current responses to COVID-19, and prepare health systems and populations for a timely and effective global response to the inevitable next pandemic.

Authors Contribution:

Dr Jennifer Summers Literature search, figures, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing. Professor Hsien-Ho Lin Literature search, data interpretation, writing. Dr Hao-Yuan Cheng Literature search, data interpretation, writing. Dr Lucy Telfar-Barnard Literature search, data interpretation, writing. Dr Amanda Kvalsvig Literature search, data interpretation, writing. Professor Nick Wilson Literature search, data interpretation, writing. Professor Michael Baker Literature search, data interpretation, writing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements/Funding

We acknowledge funding support from the Health Research Council of New Zealand (20/1066), which did not have any role in paper design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation or writing of this paper. The corresponding author, Dr Jennifer Summers has had full access to all data, which is publicly available, and has final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Short List of Websites:

Editor note: The Lancet Group takes a neutral position with respect to territorial claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2020.100044.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Pneumonia of unknown cause - China. Disease Outbreak News (DONs) 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://www.who.int/csr/don/05-january-2020-pneumonia-of-unkown-cause-china/en/.

- 2.World Health Organization. WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://covid19.who.int/.

- 3.STATBEL: Belgium in figures. Structure of the population. 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://statbel.fgov.be/en/themes/population/structure-population.

- 4.Office for National Statistics. Population estimates. 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates.

- 5.Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora. COVID-19: current cases. COVID-19 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-current-situation/covid-19-current-cases.

- 6.Stats NZ - Tatauranga Aotearoa. Estimated Population of NZ. 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://www.stats.govt.nz/indicators/population-of-nz.

- 7.The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region: Census and statistics department. Population. 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/hkstat/sub/so20.jsp.

- 8.The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region - Census and statistics department. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) in Hong Kong. 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://www.coronavirus.gov.hk/eng/index.html.

- 9.Department of Statistics Singapore. Population and population structure. 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://www.singstat.gov.sg/find-data/search-by-theme/population/population-and-population-structure/latest-data.

- 10.National Statistics - Republic of China (Taiwan). Statistics from statistical bureau. 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://eng.stat.gov.tw/point.asp?index=9.

- 11.Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En.

- 12.Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. COVID-19 (2019-nCoV). 2020 [cited 2020 5 September]; Available from: https://sites.google.com/cdc.gov.tw/2019-ncov/taiwan.

- 13.Baker MG, Wilson N, Anglemyer A. Successful elimination of Covid-19 transmission in New Zealand. N Engl J Med. 2020:e56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2025203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. Taiwan national infectious disease statistics system. 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://nidss.cdc.gov.tw/en/NIDSS_DiseaseMap.aspx?dc=1&dt=5&disease=19CoV.

- 15.Ministry of Health and Welfare. Crucial policies for combating COVID-19. 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://covid19.mohw.gov.tw/EN/mp-206.html.

- 16.Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora. New Zealand government 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/.

- 17.Institute of Environmental Science and Research [ESR]. Crown research institute - New Zealand 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://www.esr.cri.nz/.

- 18.Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. Taiwan timely identifies first imported case of 2019 novel coronavirus infection returning from Wuhan, China through onboard quarantine; Central Epidemic Command Center (CECC) raises travel notice level for Wuhan, China to Level 3: Warning. 2020 21 January 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En/Bulletin/Detail/pVg_jRVvtHhp94C6GShRkQ?typeid=158.

- 19.Chang CM, Tan TW, Ho TC, Chen CC, Su TH, Lin CY. COVID-19: Taiwan's epidemiological characteristics and public and hospital responses. PeerJ. 2020;8 doi: 10.7717/peerj.9360. e9360-e9360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora. Single case of COVID-19 confirmed in New Zealand. Media Release 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/news-media/media-releases/single-case-covid-19-confirmed-new-zealand.

- 21.Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora. Covid-cases-1sep20_1.xlsx. COVID-19 - current cases details 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-current-situation/covid-19-current-cases/covid-19-current-cases-details-confirmed.

- 22.The World Bank. Population density (people per sq. km of land area) - New Zealand. 2019 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.POP.DNST?locations=NZ.

- 23.Hsieh V.C.-R. Putting resiliency of a health system to the test: COVID-19 in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2020;119(4):884–885. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin C, Braund WE, Auerbach J. Policy decisions and use of information technology to fight 2019 novel coronavirus disease, Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis J. 2020;26(7) doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. Travelers entering Taiwan to be required to complete health declaration form starting February 11. 2020 [cited 2020 4 September]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En/Bulletin/Detail/nn4-vFhmIl-4GqA_GDhtmQ?typeid=158.

- 26.Chen CM, Jyan HW, Chien SC. Containing COVID-19 among 627,386 persons in contact with the diamond princess cruise ship passengers who disembarked in Taiwan: big data analytics. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e19540. doi: 10.2196/19540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsay SF, Kao CC, Wang HH, Lin CC. Nursing's response to COVID-19: lessons learned from SARS in Taiwan. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;108 doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103587. 103587-103587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora . 2nd edn. Wellington; New Zealand: 2017. New Zealand influenza pandemic plan: a framework for action. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora. COVID-19: border controls: guidance to support implementation of the COVID-19 public health response (Air Border) order 2020. 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-current-situation/covid-19-border-controls-facilities.

- 30.Mallapaty S. What the cruise-ship outbreaks reveal about COVID-19. Nature. 2020;580(18) doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00885-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang CJ, Ng CY, Brook RH. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: big data analytics, new technology, and proactive testing. JAMA. 2020;323(14):1341–1342. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. All 189 contacts at the same company as Thai migrant worker test negative for COVID-19. 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En/Bulletin/Detail/hxfI2-iPAw0D5a2BDDW8lw?typeid=158.

- 33.Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. Cumulative total of 447 COVID-19 cases confirmed in Taiwan; 438 patients released from isolation. 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En/Bulletin/Detail/nm7NOwh-PQVCb68kHUSAMQ?typeid=158.

- 34.Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora. COVID-19: Significant clusters. COVID-19 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-current-situation/covid-19-current-cases/covid-19-significant-clusters.

- 35.Potter C. New Zealand reports 80 COVID-19 cases from domestic transmission, breaking streak. 2020 [cited 2020 22 September 2020]; Available from: https://www.outbreakobservatory.org/outbreakthursday-1/8/20/2020/new-zealand-reports-78-covid-19-cases-from-domestic-transmission-breaking-streak.

- 36.Ng T.-C.V., Cheng H.-Y., Chang H.-H. Effects of case- and population-based COVID-19 interventions in Taiwan. medRxiv. 2020 2020.08.17.20176255. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. People must wear masks in eight public venues; local governments and competent authority may announce and impose penalties for violators if necessary. 2020 [cited 2020 4 September]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En/Bulletin/Detail/OGU5TvITYEKel0PH5Akg7g?typeid=158.

- 38.Kvalsvig A, Wilson N, Chan L. Mass masking: an alternative to a second lockdown in Aotearoa. N Z Med J. 2020;133:8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin C, Mullen J, Braund WE, Pikuei T, Auerbach J. Reopening safely - Lessons from Taiwan's COVID-19 response. J Glob Health. 2020;10(December) doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.020318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verrall A. University of OtagoWellington; New Zealand: 2020. Rapid audit of contact tracing for COVID-19 in New Zealand. Editor. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson N, Telfar Barnard L, Kvalsvig A, Baker M. Wellington; New Zealand: 2020. Potential health impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic for New Zealand if eradication fails: report to the NZ ministry of health. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aylward B, Liang W. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2020. Report of the WHO-China joint mission on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) EditorWorld Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baker MG, Telfar Barnard L, Kvalsvig A. Increasing incidence of serious infectious diseases and inequalities in New Zealand: a national epidemiological study. Lancet. 2012;379(9821):1112–1119. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61780-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson N, Telfar Barnard L, Summers JA, Shanks GD, Baker MG. Differential mortality rates by ethnicity in 3 influenza pandemics over a century, New Zealand. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18(1):71–77. doi: 10.3201/eid1801.110035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheng H, Jian S, Liu D. Contact tracing assessment of COVID-19 transmission dynamics in Taiwan and risk at different exposure periods before and after symptom onset. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ministry of Foreign Affairs - Republic of China (Taiwan). About Taiwan - people. 2018 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://www.taiwan.gov.tw/content_2.php.

- 47.Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. COVID-19 coronavirus disease - communication resources. 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En/Category/List/8u47bJl1Rv1jwpfy5ne33Q.

- 48.Boyd M., Baker M.G., Wilson N. Border closure for island nations? Analysis of pandemic and bioweapon-related threats suggests some scenarios warrant drastic action. Aust N Zeal J Public Health. 2020;44(2):89–91. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baker M, Kvalsvig A, Verrall A. New Zealand's COVID-19 elimination strategy. Med J Aust. 2020 doi: 10.5694/mja2.50735. Preprint, 19 May 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora. Advice to airline crew on precautions to reduce risk of COVID-19 infection. 2020 [cited 2020 1 September]; Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-information-specific-audiences/covid-19-resources-air-crew-and-border-sector.

- 51.Day M. Covid-19: Concern about social care's ability to cope with pandemics was raised two years ago. BMJ. 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1879. (m1879) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee T.-L. Legal preparedness as part of COVID-19 response: the first 100 days in Taiwan. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park S., Choi G.J., Ko H. Information technology–based tracing strategy in response to COVID-19 in South Korea—privacy controversies. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2129–2130. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.