Abstract

Individuals with substance use disorders (SUDs), including those in long-term recovery, and their loved ones are facing rapid changes to treatment and support services due to COVID-19. To assess these changes, the Addiction Policy Forum fielded a survey to their associated patient and family networks between April 27 and May 13, 2020. Individuals who reported a history of use of multiple substances were more likely to report that COVID-19 has affected their treatment and service access, and were specifically more likely to report both use of telehealth services and difficulties accessing needed services. These findings suggest that individuals with a history of using multiple substances may be at greater risk for poor outcomes due to COVID-19, even in the face of expansion of telehealth service access.

Keywords: COVID-19, Addictive behaviors, Substance-related disorders, Telemedicine, Polysubstance use, Treatment access

1. Brief overview

Individuals with substance use disorders (SUDs), including those in long-term recovery, and their families are facing rapid changes to SUD treatment and recovery support services, including mutual aid groups, due to COVID-19. Ensuring access to treatment and recovery services is essential, given that stress, such as that brought on by the pandemic, can worsen SUD outcomes (Sinha, 2001). However, many SUD treatment settings have operated at reduced capacities, closing some units or ending group therapies (Roncero et al., 2020). Clinicians and regulators have responded by increasing availability of telehealth services, however, in an effort to continue providing SUD care despite challenges in face-to-face health care provision. As one example, practices for prescribing medications for opioid use disorder, in particular, have shifted to allow more unsupervised dosing (Alexander, Stoller, Haffajee, & Saloner, 2020), which can increase patient autonomy (Columb, Hussain, & O'Gara, 2020). However, not all SUDs are treated with medications that can be administered remotely, and not all services can be provided remotely and of services that can be, not all are recommended for all levels of SUD severity (Ornell et al., 2020). Some individuals with SUDs are likely to encounter difficulties in accessing quality care, a concern of not only those individuals, but one clinicians share as well (Bojdani et al., 2020). At particular risk for other psychiatric problems are people with polysubstance use concerns (Connor, Gullo, White, & Kelly, 2014); this group also tends to report higher utilization of more “intensive” services, such as inpatient and residential care (Bhalla et al., 2017). Given that polysubstance use may be an indicator of higher-risk substance-use behavior, we examined diminished access to treatment and recovery support services among individuals who reported using both single and multiple substances.

2. The current state of services

2.1. Data collection

The Addiction Policy Forum (APF) fielded an uncompensated survey via email to their national (U.S.) network of patients, families, and survivors, with promotion through APF's state chapters to increase recruitment (Hulsey, Mellis, & Kelly, 2020). A total of 1148 participants, including 1094 complete responses, responded between April 27, 2020, and May 13, 2020. The IntegReview IRB approved the study procedures.

We queries participants regarding the substances they or their family members used (alcohol, stimulants, opioids, nicotine, marijuana, sedatives, and other), and whether anything about their SUD recovery and treatment access had changed due to COVID-19. If participants said their access had changed, we then asked them to self-report specific changes: inabilities to access needed services, needle exchanges, and/or naloxone; access to telehealth, curbside pickup for medications, and take-home dosing. The full text of these items is available in the Appendix.

2.2. Data analysis

We sought to determine whether specific groups with substance use concerns were more likely to report that they had unmet service needs. We examined the relationship between endorsement of the statement “unable to access my needed services” (coding individuals who said treatment had not changed due to the pandemic as not endorsing this item) as a function of the number of substances respondents endorsed, using logistic regression. We controlled for gender and race as categorical variables, and age and education as ranks. We repeated regression analyses excluding those who did not report SUDs themselves, with no meaningful differences in interpretation.

2.3. Results

Demographics and substance use data are reported in Table 1 , stratified by reported single substance or polysubstance involvement. We observed no differences in age, race, ethnicity, gender, or education relative to single substance and polysubstance use. As anticipated, endorsing involvement with any one substance also meant individuals were more likely to endorse involvement with multiple substances. Polysubstance use was also associated with reported changes in treatment or recovery support service access due to COVID-19 (39% among people reporting polysubstance use versus 26% among those with single substance use). In particular, polysubstance-involved respondents were more likely to report inability to access naloxone (3.7% versus 0.9%) and needle exchange (3.1% versus 0.6%) services, engagement with telehealth services (21% versus 13%), and general inability to access needed services (16.6% versus 9.8%). All differences withstand a Bonferroni correction (0.05/19 = 0.0026), except for the reported inabilities to access naloxone and needle exchange services.

Table 1.

Demographic and substance use variables.

| Single substance use (n = 377) | Poly substance use (n = 741) | p Test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | 0.309 | ||

| Female | 227 (65.4%) | 471 (65.9%) | |

| Male | 116 (33.4%) | 226 (31.6%) | |

| Other | 4 (1.2%) | 18 (2.5%) | |

| Age, n (%) | 0.169 | ||

| 18–25 | 16 (4.6%) | 30 (4.2%) | |

| 26–40 | 121 (34.7%) | 237 (33.1%) | |

| 41–60 | 142 (40.7%) | 337 (47.1%) | |

| 61–64 | 40 (11.5%) | 51 (7.1%) | |

| 65–74 | 26 (7.4%) | 54 (7.6%) | |

| 75 years or older | 4 (1.1%) | 6 (0.8%) | |

| Hispanic or Latinx, n (%) | 30 (8.6%) | 52 (7.3%) | 0.537 |

| Race, n (%) | 0.804 | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 4 (1.2%) | 14 (2.0%) | |

| Asian | 5 (1.4%) | 8 (1.1%) | |

| Black or African American | 18 (5.2%) | 28 (3.9%) | |

| Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.1%) | |

| Other | 15 (4.3%) | 34 (4.8%) | |

| White | 304 (87.6%) | 625 (88.0%) | |

| Education, n (%) | 0.548 | ||

| Less than high school | 5 (1.4%) | 6 (0.8%) | |

| High school graduate or GED | 45 (12.9%) | 80 (11.2%) | |

| Some college, no degree | 76 (21.7%) | 180 (25.2%) | |

| Associate degree | 36 (10.3%) | 81 (11.3%) | |

| Bachelor's degree | 91 (26.0%) | 194 (27.2%) | |

| Graduate/professional degree | 97 (27.7%) | 173 (24.2%) | |

| Family member impacted by substances, n (%) | 136 (36.4%) | 313 (42.2%) | 0.068 |

| In recovery, n (%) | 177 (47.3%) | 415 (56.0%) | 0.007 |

| Receiving treatment, n (%) | 30 (8.0%) | 53 (7.2%) | 0.688 |

| Currently using substances, n (%) | 53 (14.2%) | 70 (9.4%) | 0.023 |

| Alcohol, n (%) | 168 (44.6%) | 564 (76.1%) | <0.001 |

| Stimulants, n (%) | 37 (9.8%) | 439 (59.2%) | <0.001 |

| Opioids, n (%) | 100 (26.5%) | 427 (57.6%) | <0.001 |

| Marijuana, n (%) | 17 (4.5%) | 407 (54.9%) | <0.001 |

| Sedatives, n (%) | 1 (0.3%) | 239 (32.3%) | <0.001 |

| Nicotine, n (%) | 17 (4.5%) | 437 (59.0%) | <0.001 |

| Other substances, n (%) | 37 (9.8%) | 66 (8.9%) | 0.699 |

| Affected ability to receive services, n (%) | 91 (26.1%) | 277 (39.0%) | <0.001 |

| Unable to access needed services, n (%) | 34 (9.8%) | 117 (16.6%) | 0.004 |

| Able to get more take-home doses, n (%) | 9 (2.6%) | 26 (3.7%) | 0.45 |

| Able to get curbside medication, n (%) | 11 (3.2%) | 37 (5.2%) | 0.171 |

| Receiving telehealth services, n (%) | 46 (13.2%) | 153 (21.7%) | 0.001 |

| Unable to access syringe exchanges, n (%) | 2 (0.6%) | 22 (3.1%) | 0.017 |

| Unable to access usual naloxone, n (%) | 3 (0.9%) | 26 (3.7%) | 0.015 |

| An overdose occurred, n (%) | 11 (2.9%) | 36 (4.9%) | 0.177 |

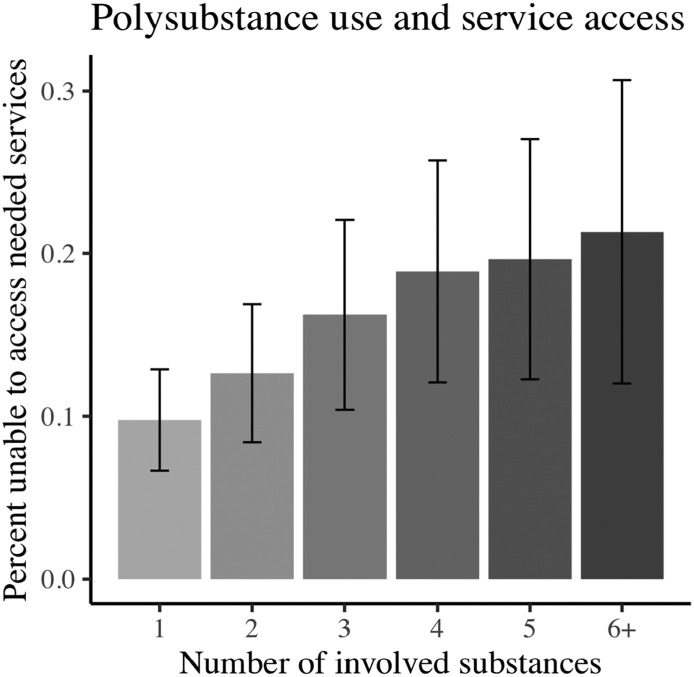

We used logistic regression to determine whether the number of substances with which someone was involved, a proxy for severity of polysubstance use, statistically predicted endorsement of difficulty accessing services. The number of substances with which someone was involved was significantly and positively associated with probability of difficulties accessing treatment (Β = 0.18, std. error = 0.052, z = 3.41, p = 0.00065), controlling for age, gender, race, and education (Fig. 1 ). We also observed that individuals (n = 22) who reported genders other than male or female (including nonbinary, other, and preferring not to disclose) were more likely to report that they were unable to access their needed services (Β = 0.97, std. error = 0.489, z = 1.99, p = 0.047).

Fig. 1.

Polysubstance use and self-reported ability to access needed services.

The x axis depicts the number of substances participants endorsed using (including alcohol, nicotine, opioids, marijuana, sedatives, stimulants, and others). The y axis depicts the percent of this group reporting that they were “unable to access needed services” for treatment and recovery support, specifically due to changes in service because of COVID-19. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Given that some treatment access may be particularly relevant for opioids, we repeated logistic regressions in post-hoc analyses, replacing the number of involved substances with a binary indicator of involvement versus no involvement with opioids. Opioid involvement was associated with increased likelihood of being unable to access needed services (Β = 0.51, p = 0.007). To explore other substances (without correction), we observed similar patterns for sedatives (Β = 0.46, p = 0.02), stimulants (Β = 0.36, p = 0.046), and nicotine (Β = 0.37, p = 0.036), but not alcohol (Β = 0.05, p = 0.75) or marijuana (Β = 0.26, p = 0.15).

Among the 377 single substance-involved individuals, nearly half (178) reported involvement with only alcohol, and next most common was opioids (100 respondents). Repeating the logistic regression with binary indicators of alcohol only (Β = −0.6, p = 0.03) and opioids only (Β = −0.62, p = 0.08) indicated that both single substance-use indicators are negatively associated with difficulties accessing treatment, further supporting single substance use being associated with fewer difficulties in treatment access.

Limitations include the cross-sectional design and that we collected data using self-report and online, which may restrict the representativeness of the sample. Respondents studied here included both individuals with SUDs (n = 748) and family members (n = 377), and different biases may exist in each group. Future studies should examine similarities and differences between respondents with SUDs and family members of individuals with SUDs. Despite the limitations, the results provide important insight into a clinically relevant situation during the COVID-19 pandemic and related rapid changes to treatment provision.

3. Implications: what these changes mean for the field

Individuals with high-risk profiles—those who use multiple substances—are more likely to report diminished access to their needed services despite increased access to and/or utilization of telehealth services. This suggests that COVID-19 may especially impact polysubstance users, in terms of treatment disruptions and recovery support. We also observed that despite these changes, they are still reporting unmet service needs. This finding may suggest that these individuals have greater needs for the types of services that have been restricted during the pandemic (including face-to-face care and group therapies). Some focused efforts at addressing treatment needs during COVID-19 have specifically targeted service provision for individuals with moderate to severe SUDs, particularly in the context of buprenorphine for opioid use disorder (e.g., Harris et al., 2020; Samuels et al., 2020). However, the current findings suggest that more may be needed, including research to investigate the efficacies and impacts of specific approaches (e.g., telemedicine).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Individual contributions from each author to this manuscript according to relevant CRediT roles include the following: Alexandra Mellis contributed to conceptualization of study and analyses in this manuscript, formal analyses, methodology, and the original draft and revision of the manuscript. Marc Potenza contributed to conceptualization of study and analyses in this manuscript, methodology, and the review and editing of the initial and revised manuscript. Jessica Hulsey contributed to conceptualization of the survey and study and analyses in this manuscript, data curation, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, and the review and editing of the initial and revised manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

Supplementary file to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108180.

Appendix A. Supplementary file

Survey question text.

References

- Alexander, G. C., Stoller, K. B., Haffajee, R. L., & Saloner, B. (2020). An epidemic in the midst of a pandemic: Opioid use disorder and COVID-19. Annals of Internal Medicine, M20-1141. Advance online publication. doi: 10.7326/M20-1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bhalla Ish P., Stefanovics Elina A., Rosenheck Robert A. Clinical epidemiology of single versus multiple substance use disorders. Medical Care. 2017;55(9):S24–S32. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bojdani, E., Rajagopalan, A., Chen, A., Gearin, P., Olcott, W., Shankar, V., Cloutier, A., Solomon, H., Naqvi, N. Z., Batty, N., Festin, F., Tahera, D., Chang, G., & DeLisi, L. E. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic: Impact on psychiatric care in the United States. Psychiatry Research, 289, 113069. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Columb, D., Hussain, R., & O'Gara, C. (2020). Addiction psychiatry and COVID-19: Impact on patients and service provision. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 1–5. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2020.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Connor J.P., Gullo M.J., White A., Kelly A.B. Polysubstance use: Diagnostic challenges, patterns of use and health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2014;27(4):269–275. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M., Johnson, S., Mackin, S., Saitz, R., Walley, A. Y., & Taylor, J. L. (2020). Low barrier Tele-buprenorphine in the time of COVID-19: A case report. Journal of Addiction Medicine. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hulsey, J., Mellis A., & Kelly, B. (2020) COVID-19 pandemic impact on patients, Families and Individuals in Recovery from Substance Use Disorder. https: //54817af5-b764-42ff-a7e2-97d6e4449c1a.usrfiles.com/ugd/54817a_7ff82ba57ba14491b888d9d2e068782f.pdf Accessed August 11, 2020.

- Ornell, F., Moura, H. F., Scherer, J. N., Pechansky, F., Kessler, F., & von Diemen, L. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on substance use: Implications for prevention and treatment. Psychiatry Research, 289, 113096. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Roncero, C., García-Ullán, L., de la Iglesia-Larrad, J. I., Martín, C., Andrés, P., Ojeda, A., González-Parra, D., Pérez, J., Fombellida, C., Álvarez-Navares, A., Benito, J. A., Dutil, V., Lorenzo, C., & Montejo, Á. L. (2020). The response of the mental health network of the Salamanca area to the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of the telemedicine. Psychiatry Research, 291, 113252. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Samuels, E. A., Clark, S. A., Wunsch, C., Keeler, L., Reddy, N., Vanjani, R., & Wightman, R. S. (2020). Innovation during COVID-19: Improving addiction treatment access. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000685. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sinha R. How does stress increase risk of drug abuse and relapse? Psychopharmacology. 2001;158(4):343–359. doi: 10.1007/s002130100917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Survey question text.