Abstract

OBJECTIVE: We sought to assess the impact of Lidose-isotretinoin taken without food on patient quality of life (QoL) at baseline, monthly intervals, and end of study in patients with severe recalcitrant nodular acne. DESIGN: In this open-label, single-arm, multicenter study, 197 patients took twice-daily Lidose-isotretinoin without food for 20 weeks (120–150mg/kg cumulative dosage). Patient visits occurred at Weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20. At baseline and Weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20, patients underwent QoL and acne severity assessments and lesion counts. SETTING: Participants were enrolled from 21 sites across the United States. PARTICIPANTS: Eligible participants were 12 to 45 years of age, weighing 40 to 110kg, and with e;5 facial nodules and no prior exposure to systemic retinoids, including isotretinoin. Female participants were nonpregnant and nonlactating. MEASUREMENTS: An acne-specific QoL questionnaire (Acne-QoL) was used to assess QoL. Efficacy endpoints were lesion counts and Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) of acne severity. Safety assessments included reported adverse events. RESULTS: Lidose-isotretinoin taken without food significantly improved mean (standard deviation) overall Acne-QoL score from baseline (61.6 [28.7]) to end of treatment (101.8 [16.9]; P<0.0001). Improvements were shown in both male and female patients. Significant improvements in patient QoL (overall and by questionnaire domain), lesion counts, and IGA scores were observed as early as Week 4 and continued to improve throughout treatment. CONCLUSION: Twice-daily Lidose-isotretinoin taken without food for 20 weeks significantly improved patient QoL from Week 4.

Keywords: Acne, isotretinoin, Investigator Global Assessment, Lidose-isotretinoin, lesions, quality of life

Isotretinoin has been the standard of care for severe nodular acne since for 35 years.1,2 Patients with acne resistant to conventional therapies have been shown to achieve complete, or nearly complete clearance, and prolonged remission following a single course of isotretinoin.3 As a result, isotretinoin improves patients’ QoL.4

However, due to the highly lipophilic nature of traditional forms of isotretinoin, historically Accutane® (Roche Laboratories Inc., Nutley, New Jersey), it is recommended that oral traditional isotretinoin is administered with a high-fat/ high-calorie meal to optimize bioavailability and efficacy.5,6 The bioavailability of traditional isotretinoin taken in fasted conditions is nearly 60 percent lower than when traditional isotretinoin is taken under fed conditions.6 Nonadherence to isotretinoin food intake requirements, to any degree, could compromise long-term efficacy and might affect patient QoL.7

The patient QoL benefits associated with traditional isotretinoin therapy might be achievable without specific dietary requirements through treatment with Lidose-isotretinoin (Absorica®; Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc., Princeton, New Jersey). Lidose-isotretinoin has increased bioavailability compared with traditional isotretinoin because the formulation is presolubilized in a lipid matrix. A pharmacokinetic profile comparison study showed that the bioavailability of Lidoseisotretinoin was reduced by 33.2 percent when it was taken in the fasted versus the fed state, whereas the bioavailability of traditional isotretinoin was reduced by 60.4 percent under the same conditions.8

Previously, a Phase III study has shown Lidose-isotretinoin to be noninferior to traditional isotretinoin with respect to efficacy and safety when taken in a fed state.9 However, to date, the effect of Lidose-isotretinoin treatment on patient QoL has not been assessed.

In this study, we investigated the effect of fasted-state Lidose-isotretinoin on QoL in patients with severe recalcitrant nodular acne.

METHODS

This open-label, single-arm, multicenter, Phase IV study (NCT02457520) assessed the effect of Lidose-isotretinoin administered under fasted conditions over 20 weeks on QoL in patients with severe recalcitrant nodular acne. The efficacy and safety profiles of Lidoseisotretinoin were also evaluated. The study was conducted at 21 sites across the United States; screening began January 29, 2015, and the active treatment period (ATP) was completed in June 2016. The study was registered May 29, 2015.

The study protocol was adherent with Good Clinical Practice, the Declaration of Helsinki, and national and regional regulations. Before commencing the study, each patient, or the legal guardian if the patient was under the legal age of consent, provided written informed consent.

Eligibility criteria. Eligible participants were patients with acne in good general health, who had ≥5 facial nodules, were aged 12 to 45 years, and weighed 40 to 110kg. Female patients were required to be nonpregnant and nonlactating. Participants were not eligible if they had any prior exposure to systemic retinoids, including isotretinoin. Other exclusion criteria included any skin disease or condition that might interfere with the evaluation or treatment of acne; history or presence of any clinically significant unstable medical condition that might pose a risk to the safety of the patient, as determined by investigator opinion; history of a major psychiatric condition; and history, or suspected history, of excessive alcohol or drug abuse.

Women of childbearing potential had to have monthly negative serum pregnancy test results. They were also required to use two forms of effective contraception simultaneously for at least one month before, during, and at least one month after Lidose-isotretinoin treatment, following iPLEDGE® requirements.10 Alternatively, they could commit to continuous abstinence from heterosexual intercourse.

Procedure. During the ATP, eligible patients received Lidose-isotretinoin capsules twice daily without food (>1 hour before the next meal or ≥2 hours after ingestion of food or beverages other than water) for 20 weeks. To attain a target cumulative dosage of 120 to 150mg/kg, patients received an initial dosage of 0.5mg/kg/ day for four weeks, followed by 1.0mg/kg/day for 16 weeks. Each dosage was divided into two daily doses.

Patient visits occurred throughout treatment at Weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20. At baseline and Weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20, patients underwent QoL and acne severity assessments and lesion counts. Adverse event (AE) and clinical laboratory assessments occurred at all visits. Any patient who discontinued was invited to receive an end-of-treatment (EOT) assessment identical to the assessment scheduled for Week 20.

Primary endpoint. The primary efficacy endpoint was the change in patient QoL from baseline to EOT. Over the course of the study, patients were required to complete the validated, acne-specific QoL questionnaire (Acne-QoL) to track progress.11 The questionnaire included 19 questions covering four domains: self-perception (5 questions), role-emotional (5 questions), role-social (4 questions), and acne symptoms (5 questions). Responses were graded from 0 (extreme effect) to 6 (no effect). Scores were assessed overall and by domain. The greatest possible overall score was 114, achieved by scoring a maximum score of 24 for the role-social domain and 30 for each of the other three domains.

Secondary endpoints. Secondary endpoints included efficacy and safety. Efficacy was assessed by Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) of disease activity and by inflammatory (papules, pustules, nodules), noninflammatory (open comedones, closed comedones), and nodular lesion counts. IGA scores graded overall lesion severity from 0 (clear) to 5 (very severe). Secondary endpoints were change from baseline to Weeks 4, 8, 12, and 16 in Acne-QoL score; change from baseline to EOT in lesion counts (inflammatory, noninflammatory, nodular, and total); change from baseline to EOT in IGA score; and frequency and severity of AEs. Post-hoc analyses assessed changes in QoL stratified by patient sex.

Statistical analysis. Power analysis revealed that a sample size of 200 patients would be appropriate to provide adequate estimates of probable events in the population. Estimates of the endpoints of interest were calculated with 95 percent two-sided confidence intervals whenever possible. The statistical analysis plan did not outline any statistical hypothesis tests, and summaries of efficacy variables were made using descriptive statistics. Changes from baseline were analyzed using paired t-tests (Acne-QoL scores and lesion counts) or a Wilcoxon signed-rank test (IGA scores). Post hoc analyses were performed without adjustment for multiplicity. Analysis of treatment success was calculated as the number of patients achieving ≥90-percent reduction in lesion counts from baseline to Week 20.

QoL and efficacy analyses were conducted in the per-protocol (PP) population, defined as all randomized patients who were ≥75 percent adherent with the dosing regimen and who had a Week 20 acne lesion count. The safety population, used for the safety analyses, comprised all patients enrolled.

RESULTS

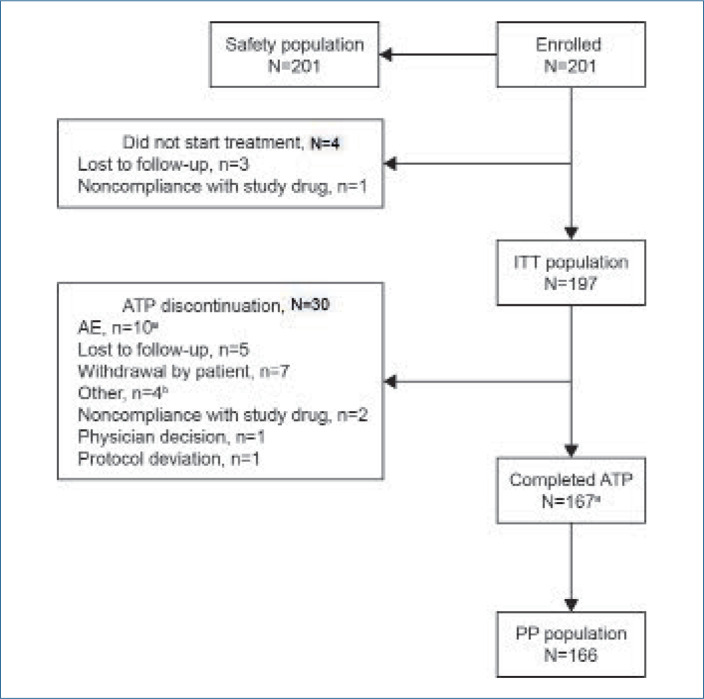

Demographics. In total, 232 patients were screened, 201 of whom were enrolled in the study and included in the safety population (Figure 1). Study medication was administered to 197 patients, 167 of whom completed the ATP. The PP population comprised 166 patients. Of the safety population, 125 patients (62.2%) were male, 167 (83.1%) were white, and 170 (84.6%) were non-Hispanic/Latino. The mean (standard deviation [SD]; range) age was 18.7 (6.4; 12–45) years and mean (SD; range) weight was 71.0 (14.6; 45–110) kg.

FIGURE 1.

Patient disposition. aOne patient discontinued treatment because of an AE (depression) on Day 112. The patient was observed until AE resolution on Day 191, but was not included in the PP population; bThree because of pharmacy access issues and one because of a move away from study site.

AE: adverse event; ATP: active treatment period; ITT: intention-to-treat; PP: per-protocol

Patient disposition. In total, 34 of the 201 enrolled patients (16.9%) did not start treatment or discontinued treatment before the end of the ATP; the most common reasons for this were AEs (10 patients), loss to follow-up (8 patients), and patient withdrawal (7 patients; Figure 1). One patient who completed the ATP discontinued treatment prematurely due to an AE (depression) at Day 112; this patient was observed until AE resolution on Day 191, and thus was counted as having completed the ATP but was not included in the PP population.

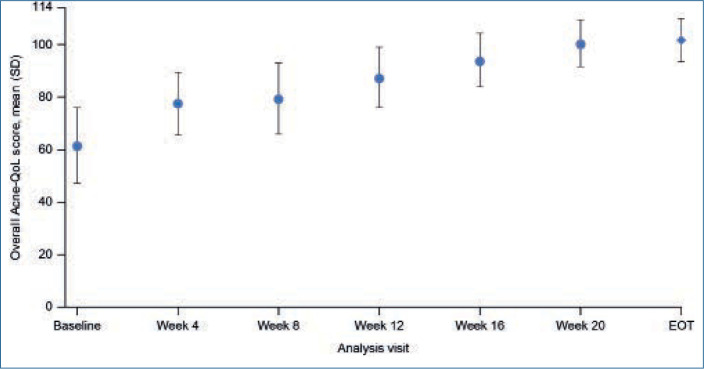

Acne-QoL Questionnaire results. Mean (SD) Acne-QoL overall score improved significantly from 61.6 (28.7) at baseline to 101.8 (16.9) at EOT (P<0.0001; Table 1). Significant improvements in mean overall Acne-QoL score were achieved as early as Week 4, and additional improvements continued over the course of treatment (P<0.0001 for all visits; Table 1, Figure 2).

TABLE 1.

Acne-QoL scores at baseline and EOT, and change in Acne-QoL scores at monthly intervals from baseline to EOT for overall Acne-QoL score and by domain (PP population)

| OVERALL | DOMAIN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SELF-PERCEPTION | ROLE-EMOTIONAL | ROLE-SOCIAL | ACNE SYMPTOMS | ||

| BASELINE | |||||

| N | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 |

| MEAN (SD) | 61.6 (28.7) | 15.8 (8.9) | 15.6 (8.6) | 15.5 (7.7) | 14.7 (5.8) |

| MEDIAN | 66.0 | 17.0 | 16.5 | 18.0 | 15.5 |

| MIN, MAX | 2, 111 | 0,30 | 0,30 | 0,24 | 1,28 |

| CHANGE FROM BASELINE TO WEEK 4 | |||||

| N | 149 | 149 | 149 | 149 | 149 |

| MEAN (SD) | 14.5 (19.6) | 3.6 (6.3) | 4.0 (6.5) | 2.1 (5.2) | 4.8 (5.0) |

| MEDIAN | 12.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 4.0 |

| MIN, MAX | −34, 80 | −16, 24 | −12, 29 | −16, 16 | −10, 20 |

| P-VALUEa | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| CHANGE FROM BASELINE TO WEEK 8 | |||||

| N | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 |

| MEAN (SD) | 17.8 (22.4) | 4.6 (7.1) | 4.5 (7.1) | 2.6 (5.3) | 6.1 (5.6) |

| MEDIAN | 13.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 6.0 |

| MIN, MAX | −40, 82 | −14, 24 | −15, 30 | −16, 16 | −6, 23 |

| P-VALUEa | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| CHANGE FROM BASELINE TO WEEK 12 | |||||

| N | 163 | 163 | 163 | 163 | 163 |

| MEAN (SD) | 26.3 (24.6) | 7.0 (7.9) | 6.9 (7.8) | 4.3 (6.0) | 8.2 (5.9) |

| MEDIAN | 23.0 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 8.0 |

| MIN, MAX | −30, 85 | −13, 26 | −14, 30 | −15, 21 | −7, 23 |

| P-VALUEa | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| CHANGE FROM BASELINE TO WEEK 16 | |||||

| N | 159 | 159 | 159 | 159 | 159 |

| MEAN (SD) | 32.7 (28.1) | 8.8 (8.8) | 8.7 (8.7) | 5.4 (7.1) | 9.7 (6.2) |

| MEDIAN | 29.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 4.0 | 9.0 |

| MIN, MAX | −62, 100 | −22, 30 | −16, 30 | −16, 24 | −8, 25 |

| P-VALUE | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| CHANGE FROM BASELINE TO WEEK 20 | |||||

| N | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 |

| MEAN (SD) | 39.1 (28.3) | 10.6 (8.9) | 10.5 (8.7) | 6.5 (7.1) | 11.6 (6.1) |

| MEDIAN | 34.5 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 5.0 | 11.0 |

| MIN, MAX | −30, 107 | −14, 30 | −11, 30 | −7, 24 | −5, 28 |

| P-VALUEa | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| EOT | |||||

| N | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 |

| MEAN (SD) | 101.8 (16.9) | 26.8 (5.3) | 26.4 (5.3) | 22.2 (3.9) | 26.5 (3.3) |

| MEDIAN | 108.0 | 29.0 | 28.0 | 24.0 | 27.0 |

| MIN, MAX | 14, 114 | 0, 30 | 0, 30 | 0, 24 | 13, 30 |

| CHANGE FROM BASELINE TO EOT | |||||

| N | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 |

| MEAN (SD) | 40.2 (27.9) | 10.9 (8.8) | 10.8 (8.6) | 6.7 (7.1) | 11.8 (6.0) |

| MEDIAN | 35.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 5.0 | 11.0 |

| MIN, MAX | −6, 30 | −6, 24 | −2, 28 | ||

| P-VALUEa | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

aDifferences between postbaseline and baseline values were analyzed using paired t-tests. Acne-QoL: acne-specific QoL questionnaire; EOT: end of treatment; Max: maximum; Min: minimum; PP: per-protocol; QoL, quality of life; SD: standard deviation

FIGURE 2.

Mean overall Acne-QoL score over time during the ATP (PP population). Error bars represent standard deviation. Acne-QoL: acne-specific QoL questionnaire; ATP: active treatment phase; EOT: end of treatment; PP: per-protocol; QoL: quality of life; SD: standard deviation

Overall Acne-QoL scores increased from baseline to EOT for most patients; seven (4.2%) patients in the PP population showed a decline in overall Acne-QoL from baseline to EOT. All seven patients had a reduction from baseline to EOT in role-emotional domain score and a reduction or no change in role-social domain score, five (3.0%) had a reduction in self-perception domain score, and only two (1.2%) had a reduction in acne symptoms domain score. None of these seven patients withdrew due to an AE.

Significant mean (SD) improvements were also observed from baseline to EOT for all four Acne-QoL domains: self-perception 10.9 (8.8; P<0.0001); role-emotional 10.8 (8.6; P<0.0001); role-social 6.7 (7.1; P<0.0001); and acne symptoms 11.8 (6.0; P<0.0001; Table 1). Improvements were observed at Week 4 for each domain and were maintained throughout Lidose-isotretinoin treatment.

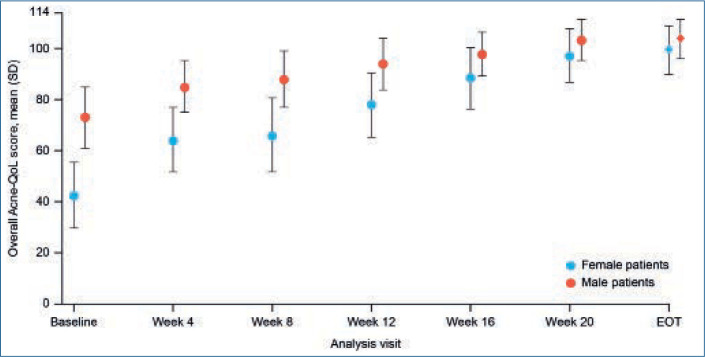

When stratified by sex, both male and female patients showed a steady increase in mean overall Acne-QoL score over the course of treatment, with statistically significant improvements from baseline observed from Week 4 onward (Figure 3). Mean (SD) Acne-QoL overall score was significantly lower for female patients compared with male patients at baseline (42.5 [26.1] vs. 73.0 [23.8]; P<0.0001); however, by EOT, there was no significant difference in mean (SD) Acne-QoL overall score between sexes (female patients: 99.2 [18.7]; male patients: 103.4 [15.6]; P=0.1225). Likewise, all individual Acne-QoL domain scores were significantly lower for female patients than for male patients at baseline; however, significant improvements were observed in all domains for both sexes from Week 4 onward. By EOT, there were no significant differences in scores between female and male patients for any of the Acne-QoL domains.

FIGURE 3.

Mean overall Acne-QoL score over time by sex during the ATP (PP population). Error bars represent standard deviation. Acne-QoL: acne-specific QoL questionnaire; ATP: active treatment phase; EOT: end of treatment; PP: per-protocol; QoL: quality of life; SD: standard deviation

Secondary efficacy endpoints. Total lesion counts decreased significantly from baseline to EOT, with a mean (SD) change from baseline of –70.5 (46.3) lesions (P<0.0001; Table 2). Mean (SD) lesion count changes from baseline to EOT were also significant for inflammatory lesions (–32.2 [16.2]; P<0.0001), noninflammatory lesions (–38.3 [42.0]; P<0.0001), and nodular lesions (–6.8 [3.5]; P<0.0001). IGA scores were also significantly reduced from baseline to EOT (mean [SD] change from baseline: –3.2 [1.1]; P<0.0001; Table 2). Improvements in lesion counts and IGA score were observed from Week 4 and maintained to EOT.

TABLE 2.

Mean change from baseline in lesion counts and IGA score at each visit (PP population)

| LESION COUNT | IGA SCORE | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INFLAMMATORY | NONINFLAMMATORY | NODULAR | TOTAL | |||||||

| OBSERVED VALUE | CHANGE FROM BASELINE | OBSERVED VALUE | CHANGE FROM BASELINE | OBSERVED VALUE | CHANGE FROM BASELINE | OBSERVED VALUE | CHANGE FROM BASELINE | OBSERVED VALUE | CHANGE FROM BASELINE | |

| BASELINE | ||||||||||

| N | 166 | - | 166 | - | 166 | - | 166 | - | 166 | - |

| MEAN (SD) | 35.0 (16.7) | - | 42.0 (43.3) | - | 7.0 (3.5) | - | 77.0 (47.9) | - | 4.2 (0.5) | - |

| MEDIAN | 33.0 | - | 27.5 | - | 6.0 | - | 63.5 | - | 4.0 | - |

| MIN, MAX | 8, 108 | - | 0, 250 | - | 5, 38 | - | 20, 297 | - | 3, 5 | - |

| WEEK 4 | ||||||||||

| N | 149 | 149 | 149 | 149 | 149 | 149 | 149 | 149 | 149 | 149 |

| MEAN (SD) | 22.4 (16.4) | −13.2 (15.4) | 35.7 (39.7) | −6.6 (22.7) | 3.9 (4.6) | −3.1 (2.8) | 58.2 (46.4) | −19.8 (28.2) | 3.5 (0.9) | −0.6 (0.8) |

| MEDIAN | 18.0 | −13.0 | 23.0 | −4.0 | 3.0 | −4.0 | 43.0 | −18.0 | 4.0 | −1.0 |

| MIN, MAX | 0, 116 | −89, 27 | 0, 250 | −126, 113 | 0, 41 | −9, 7 | 3, 291 | −128, 109 | 1, 5 | −3, 1 |

| P-VALUEa | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| WEEK 8 | ||||||||||

| N | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 |

| MEAN (SD) | 15.8 (14.0) | −19.4 (15.1) | 21.4 (24.1) | −21.0 (32.1) | 2.6 (3.0) | −4.5 (3.6) | 37.2 (32.4) | −40.4 (34.1) | 3.1 (1.0) | −1.1 (0.9) |

| MEDIAN | 13.0 | −17.5 | 14.0 | −13.0 | 2.0 | −5.0 | 29.0 | −34.5 | 3.0 | −1.0 |

| MIN, MAX | 1, 108 | −82, 19 | 0, 133 | −160, 51 | 0, 18 | −35, 6 | 1, 193 | −175, 29 | 1, 5 | −3, 1 |

| P-VALUEa | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| WEEK 12 | ||||||||||

| N | 163 | 163 | 163 | 163 | 163 | 163 | 163 | 163 | 163 | 163 |

| MEAN (SD) | 10.1 (10.1) | −24.5 (15.7) | 13.3 (17.1) | −29.2 (41.8) | 1.4 (2.5) | −5.4 (2.7) | 23.4 (23.2) | −53.7 (46.1) | 2.4 (1.2) | −1.8 (1.2) |

| MEDIAN | 7.0 | −22.0 | 8.0 | −19.0 | 0.0 | −5.0 | 16.0 | −45.0 | 2.0 | −2.0 |

| MIN, MAX | 0, 68 | −95, 22 | 0, 107 | −242, 90 | 0, 13 | −17, 8 | 0, 125 | −243, 68 | 0, 5 | −4, 1 |

| P-VALUEa | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| WEEK 16 | ||||||||||

| N | 159 | 159 | 159 | 159 | 159 | 159 | 159 | 159 | 159 | 159 |

| MEAN (SD) | 6.7 (7.7) | −28.8 (16.9) | 8.4 (13.9) | −34.0 (43.7) | 1.0 (2.3) | −5.9 (3.8) | 15.1 (18.5) | −62.7 (48.8) | 1.9 (1.2) | −2.3 (1.2) |

| MEDIAN | 4.0 | −27.0 | 4.0 | −23.0 | 0.0 | −5.0 | 7.0 | −51.0 | 2.0 | −3.0 |

| MIN, MAX | 0, 45 | −105, 12 | 0, 85 | −250, 68 | 0, 15 | −38, 10 | 0, 100 | −262, 41 | 0, 5 | −4, 1 |

| P-VALUE | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| WEEK 20 | ||||||||||

| N | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 |

| MEAN (SD) | 3.1 (4.3) | −31.9 (16.5) | 4.5 (9.6) | −37.5 (42.6) | 0.3 (0.9) | −6.7 (3.5) | 7.6 (11.9) | −69.4 (47.2) | 1.1 (1.1) | −3.1 (1.1) |

| MEDIAN | 1.0 | −31.0 | 1.0 | −25.5 | 0.0 | −6.0 | 3.0 | −56.0 | 1.0 | −3.0 |

| MIN, MAX | 0, 26 | −107, −7 | 0, 65 | −250, 48 | 0, 6 | −38, −1 | 0, 72 | −272, 15 | 0, 4 | −5, 0 |

| P-VALUEa | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| EOT | ||||||||||

| N | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 |

| MEAN (SD) | 2.8 (4.0) | −32.2 (16.2) | 3.7 (7.6) | −38.3 (42.0) | 0.2 (0.8) | −6.8 (3.5) | 6.5 (9.8) | −70.5 (46.3) | 1.0 (1.0) | −3.2 (1.1) |

| MEDIAN | 1.0 | −31.0 | 0.5 | −26.0 | 0.0 | −6.0 | 3.0 | −58.0 | 1.0 | −3.0 |

| MIN, MAX | 0, 26 | −107, −8 | 0, 50 | −250, 0 | 0, 6 | −38, −2 | 0, 58 | −272, −19 | 0, 4 | −5, 0 |

| P-VALUEa | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

aDifferences between postbaseline and baseline values were analyzed using paired t-tests. EOT, end of treatment; IGA, Investigator Global Assessment; Max, maximum; Min, minimum; PP, per-protocol; SD, standard deviation.

The number of patients achieving ≥90-percent reduction in total lesion counts from baseline to EOT was 110 (66.3%). In total, ≥90 percent reductions in nodular, inflammatory, and noninflammatory lesion counts were achieved by 144 (86.7%), 114 (68.7%), and 110 (66.3%) patients, respectively.

Adverse events. In total, 291 AEs were reported in 123 (61.2%) patients; of these, 171 (58.8%) were determined to be treatment related. Most AEs were mild or moderate in severity. The most common treatment-related AEs reported were dry lips (11.4%), dry skin (10.9%), cheilitis (9.0%), and xerosis (4.0%). 12 (6.0%) patients reported psychiatric AEs; seven (3.5%) reported depression.

Fourteen (7.0%) patients discontinued during the ATP due to AEs: nine patients experienced psychiatric AEs (8 depression, 1 anger, 1 anxiety, and 1 intentional self-injury), three experienced abnormal laboratory test results (1 abnormal liver test results, 1 dyslipidemia, 1 transaminitis), one experienced a severe migraine, and one withdrew due to diabetes.

DISCUSSION

This study explored the effects of 20 weeks of treatment with Lidose-isotretinoin in the unfed state on QoL in patients with severe recalcitrant nodular acne, examining QoL at baseline, each month on treatment, and end of study. Here, we show that Lidose-isotretinoin significantly improved QoL both overall and by domain from baseline to EOT. The improvements in QoL observed with Lidose-isotretinoin are in line with those observed with traditional isotretinoin measured with varying QoL metrics.4,12–15

Previous studies have compared QoL at beginning and end of study. One study analyzed QoL following a larger dosage of traditional isotretinoin therapy (cumulative dosage 290mg/ kg) for a longer treatment period (5–6 months) using the same Acne-QoL questionnaire.12 The analysis in that study showed that isotretinoin significantly improves QoL from baseline to EOT for self-perception (P=0.0124), role-social (P=0.0066), and acne symptoms (P=0.0265) domains, but not for the role-emotional domain (P=0.0502). No analyses were conducted for overall Acne-QoL score, and monthly assessments were not performed.

The effect of Lidose-isotretinoin on patient QoL also correlates with that of other acne therapies. McGrath et al16 demonstrated that, when measured by the World Health Organization generic health-related QoL questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF), both isotretinoin and antibiotic treatments can improve patient QoL from baseline in physical and social QoL domains (P<0.001), but not in psychological or environmental domains.

Unlike other studies that compare QoL only at baseline and EOT, we assessed QoL every four weeks throughout Lidose-isotretinoin therapy. As such, we have shown that significant improvements in QoL can be achieved with Lidose-isotretinoin as early as Week 4 and that confirmed improvement is seen as clinical assessment of acne improves.

As shown in studies investigating traditional isotretinoin, female patients in our study reported worse QoL at baseline than their male counterparts.13 However, by EOT, similar significant improvements in QoL were observed for both sexes, indicating that as acne improves with Lidose-isotretinoin treatment, the disparity in QoL scores between female and male patients is reduced.

In addition to describing improvements to patient QoL, our results support and further illustrate the efficacy and safety profile of Lidose-isotretinoin in the unfed state. Previously, a Phase III noninferiority study demonstrated that Lidose-isotretinoin was noninferior compared with traditional isotretinoin for the reduction in total and nodular lesion counts and the reduction in nodular lesion counts by ≥90 percent from baseline to Week 20 in patients with severe recalcitrant acne treated in a fed state.9 While Lidose-isotretinoin was not directly compared with traditional isotretinoin in our study, we showed that fasted-state Lidoseisotretinoin can substantially reduce lesion counts (including by ≥90% in a large number of patients) and improve acne severity as measured by IGA score, with improvements in lesion counts and IGA scores observed as early as Week 4. The safety profile observed with fasted-state Lidoseisotretinoin was also similar to that shown in the fed state in the Phase III noninferiority study.9

Limitations. The limitations of this study include a lack of placebo control to assess the extent of QoL improvements attributable to Lidose-isotretinoin. It would also be beneficial to directly compare Lidose-isotretinoin with traditional isotretinoin to evaluate whether the QoL improvements achieved with Lidoseisotretinoin are noninferior to those attained with traditional isotretinoin.

CONCLUSION

Twice-daily administration of Lidoseisotretinoin in the unfed state for 20 weeks to achieve a total cumulative dosage of 120 to 150mg/kg significantly improves patient QoL— irrespective of sex—and has a significant effect on acne severity. These changes are apparent from as early as Week 4. Lidose-isotretinoin has a comparable safety profile to traditional isotretinoin.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the participants in this study. Editorial support was provided by Tamsin Brown, MSc, JK Associates, Inc., part of the Fishawack Group of Companies, and funded by Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc. Statistical support was provided by Janice Li, Edetek Life Science, and Novella Clinical, and funded by Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.

REFERENCES

- Ingram J, Grindlay D, Williams H. Management of acne vulgaris: an evidence-based update. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35(4):351–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AAD site. Dermatologist evaluates latest isotretinoin developments for treatment of severe acne. 2014. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/dermatologist-evaluates-latest-isotretinoin-developments-for-treatment-of-severe-acne Accessed 11 Aug 2020.

- Merritt B, Burkhart C, Morrell D. Use of isotretinoin for acne vulgaris. Pediatr Ann. 2009;38(6):311–320. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20090512-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marron S, Tomas-Aragones L, Boira S. Anxiety, depression, quality of life and patient satisfactions in acne patients treated with oral isotretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:701–706. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ACCUTANE® (isotretinoin) capsules. Prescribing information. Roche Laboratories Inc. 2008.

- Colburn W, Gibson D, Wiens R, Hannigan J. Food increases the bioavailability of isotretinoin. J Clin Pharmacol. 1983;23(11–12):534–539. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1983.tb01800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Rosso J. Face to face with oral isotretinoin: a closer look at the spectrum of therapeutic outcomes and why some patients need repeated courses. J Clin Aesther Dermatol. 2012;5(11):17–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster G, Leyden J, Gross J. Comparative pharmacokinetic profiles of a novel isotretinoin formulation (isotretinoin-Lidose) and the innovator isotretinoin formulation: a randomized, 4-treatment, crossover study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(5):762–767. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster G, Leyden J, Gross J. Results of a Phase III, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, non-inferiority study evaluating the safety and efficacy of isotretinoin-Lidose in patients with severe recalcitrant nodular acne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13(6):665–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ABSORICA® (isotretinoin) capsules. Prescribing information. Ranbaxy Laboratories Inc. 2015.

- Fehnel S, McLeod L, Brandman J et al. Responsiveness of the acne-specific quality of life questionnaire (Acne-QoL) to treatment for acne vulgaris in placebo-controlled clinical trials. Qual Life Res. 2002;11(8):809–816. doi: 10.1023/a:1020880005846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyrulnik A, Viola K, Gewirman A, Cohen S. High-dose isotretinoin in acne vulgaris: improved treatment outcomes and quality of life. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1123–1130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg M, Lindberg M. Possible gender differences in the quality of life and choice of therapy in acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:969–972. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakour Y, Noormohammadpour P, Ameri H et al. The effect of isotretinoin (Roaccutane) therapy on depression and quality of life on patients with severe acne. Iran J Psychiatry. 2014;9(4):237–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesilova Y, Bez Y, Ari M, Turan E. Effects of isotretinoin on social anxiety and quality of life in patients with acne vulgaris: a prospective trial. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2012;20(2):80–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath E, Lovell C, Gillison F et al. A prospective title of the effects of isotretinoin on quality of life and depressive symptoms. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:1323–1329. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]