Abstract

Background

Coronaviruses mainly affect the respiratory system; however, there are reports of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV causing neurological manifestations. We aimed at discussing the various neurological manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection and to estimate the prevalence of each of them.

Methods

We searched the following electronic databases; PubMed, MEDLINE, Scopus, EMBASE, Google Scholar, EBSCO, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, WHO database, and ClinicalTrials.gov. Relevant MeSH terms for COVID-19 and neurological manifestations were used. Randomized controlled trials, non-randomized controlled trials, case-control studies, cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, case series, and case reports were included in the study. To estimate the overall proportion of each neurological manifestations, the study employed meta-analysis of proportions using a random-effects model.

Results

Pooled prevalence of each neurological manifestations are, smell disturbances (35.8%; 95% CI 21.4–50.2), taste disturbances (38.5%; 95%CI 24.0–53.0), myalgia (19.3%; 95% CI 15.1–23.6), headache (14.7%; 95% CI 10.4–18.9), dizziness (6.1%; 95% CI 3.1–9.2), and syncope (1.8%; 95% CI 0.9–4.6). Pooled prevalence of acute cerebrovascular disease was (2.3%; 95%CI 1.0–3.6), of which majority were ischaemic stroke (2.1%; 95% CI 0.9–3.3), followed by haemorrhagic stroke (0.4%; 95% CI 0.2–0.6), and cerebral venous thrombosis (0.3%; 95% CI 0.1–0.6).

Conclusions

Neurological symptoms are common in SARS-CoV-2 infection, and from the large number of cases reported from all over the world daily, the prevalence of neurological features might increase again. Identifying some neurological manifestations like smell and taste disturbances can be used to screen patients with COVID-19 so that early identification and isolation is possible.

Keywords: COVID-19 neurological manifestations, Acute cerebrovascular disease, SARS-CoV-2 infection, Meningoencephalitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, Smell and taste disturbances

Background

Coronaviruses are enveloped, positive-stranded RNA viruses that mainly cause respiratory and gastrointestinal tract infections [1]. They are divided into four genera: alpha, beta, delta, and gamma. Alphacoronavirus and betacoronavirus cause human infections [1]. Betacoronaviruses are further divided into 4 clades, a–d [2]. SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV are betacoronaviruses which caused outbreaks in 2002 and 2012 respectively [3]. The likely reservoirs of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV viruses were identified as bats [2]. SARS-CoV-2 is a coronavirus and is classified into the betacoronavirus 2b lineage; however, a distinct clade from the SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV [4, 5]. It has been postulated that reservoir of SARS-CoV-2 is also bats; however, more evidence is needed for proving the assumption [6]. The disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 is termed as COVID-19. COVID-19 outbreak started as a cluster of respiratory illnesses and the first case was reported from Wuhan, Hubei Province, China on 8th December [7, 8]. It was declared as a pandemic by WHO on March 11, 2020 [9].

The most common symptoms of COVID-19 are similar to other coronaviruses which include fever, fatigue, dry cough, anorexia, shortness of breath, myalgia, and headache [10–12]. Old age and co-morbidities are associated with higher mortality and morbidity as compared with younger patients and those without any co-morbidities [10, 12, 13].

The neuroinvasive and neurotropic potential of coronaviruses like SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV has been demonstrated in many previous studies [14, 15]. A similar mechanism is suggested for the SARS-CoV-2 also [16]. Neurological manifestations reported of SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and other coronaviruses include peripheral neuropathy [17], myopathies with elevated creatinine kinase [17], large vessel stroke [18], olfactory neuropathy/anosmia [19], meningoencephalitis [20, 21], post-infectious acute disseminated encephalomyelitis [22, 23], Bickerstaff’s encephalitis overlapping with Guillain-Barré syndrome [24], and Guillain-Barré syndrome [24]. This review is aimed at discussing various neurological manifestations in COVID-19, including the frequency of neurological symptoms, morbidity, mortality, laboratory parameters, and imaging findings associated with patients with neurological symptoms. In the meta-analysis, we estimated the proportion of COVID-19 patients developing neurological manifestations.

Methods

Selection criteria and search strategy

We searched the following electronic databases for articles published between 1st December 2019 to 25th June 2020; PubMed, MEDLINE, Scopus, EMBASE, Google Scholar, EBSCO, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, WHO database, and ClinicalTrials.gov. The MeSH terms and keywords used include: “COVID-19” OR “COVID 19” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR “2019 novel coronavirus” OR “2019 nCoV” AND “Neurological” OR “Brain” OR “CNS features” OR “central nervous system features” OR “peripheral nervous system features” OR “neuropathy” OR “skeletal muscle” OR “myositis” OR “neuromuscular junction” OR “headache” OR “anosmia” OR “olfactory” OR “ageusia” OR “cranial neuropathy” OR “seizures” OR “encephalitis” OR “meningitis” OR “stroke” OR “cerebrovascular disease” OR “cerebral hemorrhage” OR “intracerebral hemorrhage” OR “cerebral infarct” OR “cortical venous thrombosis” OR “deep cerebral venous thrombosis” OR “impaired consciousness” OR “confusion” OR “weakness” OR “Guillain-Barre’ syndrome” OR “Miller Fisher syndrome” OR “ataxia” OR “myopathy” OR “myelitis” OR “myelopathy” with an additional filter of “studies in human subjects”. The search was done between 31st March 2020 and 25th June 2020. To ensure literature saturation, we inspected the references of all studies included in this review. The protocol of this review was registered at PROSPERO (ID-CRD42020185593) prospectively in May 2020.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All published randomized controlled trials, non-randomized controlled trials, case-control studies, cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, case series, and case reports, if they had sufficient data on neurological features, laboratory parameters, imaging findings were included in this review. Only those studies were included in which subjects were diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection by real-time RT-PCR or high throughput sequencing analysis of swab specimens or serology or culture. We also included pre-prints and letters if they included data on neurological manifestations in COVID-19. Editorials, systematic reviews, meta-analysis, narrative reviews, conference abstracts, commentaries, animal studies, post-mortem studies, and where translation into English was not possible were excluded. The authors were contacted twice by email if any missing data in the articles.

Data extraction and study quality assessment

Databases selected were searched independently by two members (TF and AP) in the team, and, following duplicate removal, reviewed all the articles and selected articles based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Reporting was done according to the recommendations of the PRISMA statement [25]. Quality of the non-randomized studies was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale [26, 27] and the quality of one randomized controlled trial was assessed using the CONSORT criteria [28]. Any disagreements between two main reviewers were discussed with a third evaluator. Data about the author’s name, publication date, study setting and design, time and duration of the study, follow-up, the total number of patients evaluated, study population, age, gender, co-morbidities, neurological features, laboratory parameters, imaging findings, morbidity, and mortality were extracted.

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes assessed were neurological manifestations in COVID-19 patients and its prevalence. For the categorical variables, simple and relative frequency and proportions were used. For continuous variables, central tendency (mean or median) and dispersion measures (standard error, standard deviation) were used. To measure association, risk ratios, odds ratios, and hazard ratios were used and 95% confidence intervals calculated. We also assessed secondary outcomes like the association of neurological manifestations with age, co-morbidities, lab parameters including CSF study, imaging features, length of hospital stay, ICU admission, time from onset of typical COVID-19 symptoms to neurological manifestations, and morbidity/mortality.

Strategy for data synthesis, statistical analysis for meta-analysis

Data synthesis and illustration were done in tables and figures. For the categorical variables, simple and relative frequency and proportions were used. For continuous variables, measures of central tendency (mean or median) and dispersion (standard error, standard deviation) were calculated. The primary aim of our study was to synthesize the findings from multiple studies that investigated the issues related to neurological manifestations in COVID-19 and thus provide a quantitative summary, to better direct future work. The data are available in the form of proportions, defined as the number of cases of interest in a sample with a particular characteristic divided by the size of the sample. To achieve the objective of obtaining a more precise estimate of the overall proportion for a certain event (neurological manifestations) related to COVID-19, the study employed meta-analysis of proportions using a random-effects model and by the DerSimonian-Laird method [29, 30]. We performed data analysis using meta-packages in R (version 3.5.0). Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 value. I2 can take values from 0% to 100% and it is assumed that an I2 of 25%, 50%, and 75% indicate low, medium, and large heterogeneity respectively [31]. Forest plot was used to visualize the point estimates of study effects and their confidence intervals. Publication bias was evaluated using the funnel plot.

Results

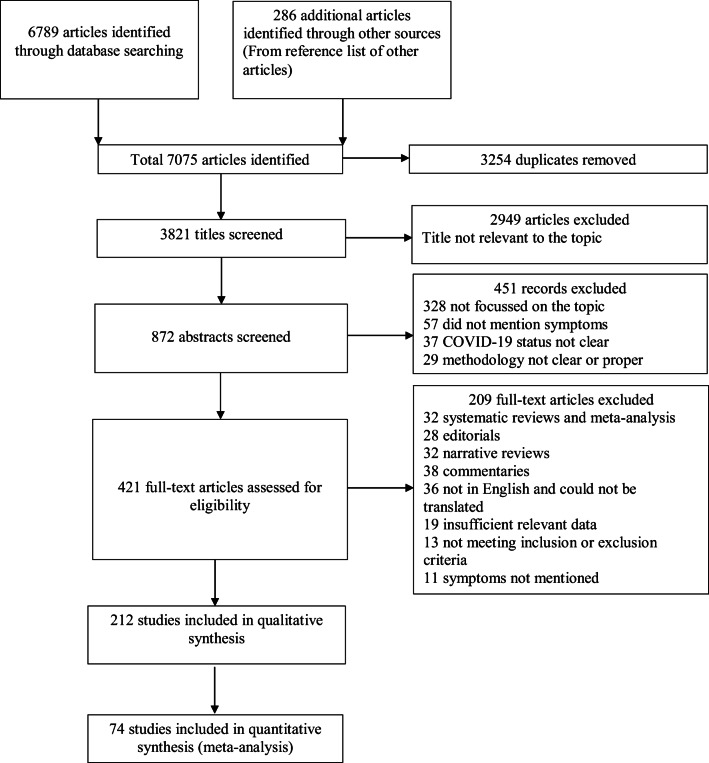

Among the 6789 articles identified, 212 studies were included in the systematic review and 74 studies in the meta-analysis (PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1)). Out of them, most were retrospective studies, 18 were cohort studies, 11 were prospective studies, nine were cross-sectional studies, one was a randomized controlled trial, one was a case-control study and the rest were all case series and case reports. Among these studies, we found only 19 studies, which investigated specifically neurological features in COVID-19 patients. Other studies, evaluated parameters in general. Table 1 shows a summary of all the observational studies included.

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included and neurological manifestations

| First author | Article type | Study setting | Type of study | Enrolment date | Follow-up duration | Total number of patients (N) | Study population | Age (years), mean ± SD or median(range) or median (IQR) | Sex (male) n (%) | Neurological features n (%) | Remarks (groups compared) | Outcome n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ling Mao [32] | Published | 3 centers of Union Hospital of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China | Retrospective, observational case series | January 16, 2020, to February 19, 2020 | NA | 214 | Consecutive hospitalized patients | 52.7 ± 15.5 | 87 (40.7) |

Any—78 (36.4) CNS—53 (24.8) Dizziness—36 (16.8) Headache—28 (13.1) Impaired consciousness—16 (7.5) Acute cerebrovascular disease—6 (2.8) Ataxia—1 (0.5) Seizure—1 (0.5) PNS—19 (8.9) Taste disturbances—12 (5.6) Smell disturbances—11 (5.1) Vision impairement—3 (1.4) Nerve pain-5 (2.3) Skeletal muscle injury—23 (10.7) |

Severe vs non-severe 5 ischaemic stroke, 1 hemorrhagic stroke |

NA |

| Yanan Li [33] | Published | Single centre, Union Hospital of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China | Retrospective, observational case series | 16 January 2020, to 29 February 2020 | NA | 221 | Consecutive hospitalized patients | 53·3 ± 15·9 | 131 (59.3) |

Acute cerebrovascular disease—13 (5·9) Ischaemic stroke—11 (84·6) Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis—1 (7·7) Cerebral haemorrhage—1 (7·7) |

Severe vs non-severe, with cerebrovascular disease vs without cerebrovascular disease | 4 ischaemic stroke and 1 hemorrhagic stroke patients expired |

| Lu Lu [34] | Published | Multicentre study from Hubei province, Sichuan province, Chongqing municipality, China | Retrospective study | January 18 to February 18, 2020 | NA | 304 | Consecutive discharged or died patients from multiple centers | 44 (33–59.25) | 182 (59.9) | Acute cerebrovascular disease–3 (1) | Mild, moderate vs severe, critical | NA |

| F.A. Klok [35] | Published | Multicentre, Netherlands | Prospective study | March 7th 2020, to April 222,020 | 14 days | 184 | Only ICU patients | NA | NA | Acute cerebrovascular disease—5 (2.8) (all ischaemic stroke) | All patients received thromboprophylaxis | 41(22%) died and 78 (43%) discharged alive |

| Corrado Lodigiani [36] | Published | Single centre, Humanitas Clinical and Research Hospital, Milan, Italy | Retrospective cohort study | 13 February−10 April 2020 | NA | 388 | Consecutive adult symptomatic patients admitted, 61 ICU patients | 66 (55–75) | 264 (68) | Acute ischaemic stroke—9 (2.5) | ICU vs general ward, survivors vs non-survivors, thromboprophylaxis in 100% ICU and 75% ward patients |

2 stroke patients died 4 patients discharged |

| Megan Fraissé [37] | Published | Single centre, France | Retrospective study | March 6 to April 22, 2020 | NA | 92 (1 lost to follow-up) | Only ICU patients | 61 (55–70) | 73 (79) |

Acute cerebrovascular disease—4 (4.3) Ischaemic—2 (2.2) Hemorrhagic—2 (2.2) |

All received thromboprophylaxis | NA |

| Siddhant Dogra [38] | Published | NYU Langone Health system, New York, USA | Retrospective cohort study | March 1st and April 27th, 2020 | NA | 3824 | All hospitalized patients | 62 (37–83) (among 33 patients) | 26/33 (78.8) | Acute hemorrhagic stroke—33 (0.9) (only in 755 neuroimaging done) |

37 had hemorrhage, but 4 excluded as hemorrhage secondary to trauma, bleeding in brain metastases, after tumor resection |

NA |

| Julie Helms [39] | Published | Strasbourg, France | Observational Prospective case series | March 3 and April 3, 2020 | NA | 58 | Consecutive hospitalized ICU patients | 63 | NA |

Agitation—40/58 (69) Corticospinal tract signs—39/58 (67) Dysexecutive syndrome—14/39 (36) MRI—leptomeningeal enhancement-8/13 (62) Perfusion abnormalities—11/11 (100) Cerebral ischaemic stroke—3/13 (23) |

NA | NA |

| Julie Helms [40] | Published | Two centers of a French tertiary hospital, France | Prospective cohort study | March 3rd and 31st 2020 | April 7th | 150 | All consecutive patients referred to ICU for ARDS | 63 (53–71) | 122 (81.3) | Cerebral ischaemic attack—2 (1.3) (population after matching—0) | Historical prospective cohort of “non-COVID-19 ARDS” patients vs COVID-19 ARDS |

Discharged—36 ICU admission—101 Died—13 |

| Sedat G Kandemirli [41] | Published | Multicentre (8 centers), Turkey | Retrospective study | March 1 to April 20,2020 | NA | 235 | Patients admitted to ICU | 63 (34–87) | 21 (78) |

Neurological symptoms—50 (21) Cortical signal abnormalities on FLAIR images—10/27 (37) Acute transverse sinus thrombosis—1 (0.4) Acute infarction in right middle cerebral artery territory—1 (0.4) |

Brain MRI done in 27/50 (54%) patients with neurological symptoms | NA |

| Silvia Garazzino [42] | Published |

Italian Society of Paediatric Infectious Diseases, Multicentre, Italy |

Retrospective study | 25 March 2020, to 10 April 2020 | At least 2 weeks | 168 | Pediatric patients under 18 years | 2.3 (0.3–9.6) | 94 (55.9) |

Non-febrile seizures—3 (1.8) Febrile seizures—2 (1.2) |

NA | Recovered—168 |

| Rajan Jain [43] | Published |

Multicentre(3 centers), New York |

Retrospective cohort | March 1, 2020, and April 13, 2020 | NA | 3218 | All patients admitted | NA | NA |

Imaging (3218) Acute cerebrovascular disease—35 (1.1) Ischaemic—26 Hemorrhagic—9 Hypoxic anoxic brain injury—2 Encephalitis—1 Clinical (454) Altered mental status or delirium (37.6%) Stroke (17.3%) Syncope (4%) Headache (3.8%) Dizziness (2.8%) Seizure (2.1%) Ataxia (1.4%) |

Neuro imaging done—454 (14.1%) Imaging Positive—38 (8.4) Stroke—35 (92.5) Ischaemic stroke—26 (68.5) Large vessel—17 (44.5) Lacunar—9 (24) Hemorrhagic stroke—9 (24) Hypoxic anoxic brain injury—2 (5) Encephalitis—1 (2.5) |

NA |

| Alberto Benussi [44] | Published |

ASST Spedali Civili Hospital, Lombardy, Italy |

Retrospective, cohort study | February 21, 2020, to April v5, 2020 | NA | 56 | All adult (≥ 18 years old) patients admitted for neurological disease and had a definite outcome | 77.0 (67.0–83.8) | 28 (50.0) |

Cerebrovascular disease—43 (76.8) TIA—5 (11.6) Ischaemic stroke—35 (81.4) Hemorrhagic stroke—3 (7.0) Epilepsy—4 (7.1) Delirium—15 (26.8) |

COVID-19 vs non-COVID-19 | Mortality—21 (37.5) |

| Weixi Xiong [45] | Published |

56 hospitals in Wuhan, Chongqing municipality, Sichuan province, China |

Retrospective cohort study | 18 January and 20 March 2020 | NA | 917 (1 asymptomatic patient excluded) (so total 918) | All consecutive symptomatic patients | 48.7 ± 17.1 | 504 (55) |

New-onset neurological events—39 (4.3) Disturbance of consciousness/delirium—21 (2.3) Syncope—3 (0.3) Traumatic brain injury—1 Acute Cerebrovascular accident—10 (early onset—2) Occipital neuralgia—1 Unexplained severe headache—2 Non-specific headache—8 Functional or? Tic/tremor—2 Muscle cramp—2 |

Critical vs non-critical neurological events |

Discharged—742 Hospitalized—145 Died—30 |

| Tyler Scullen [46] | Published | Single center, New Orleans, Louisiana | Retrospective cross-sectional analysis | April 22, 2020 | NA | 27 | Severe cases with neurological features | 59.8 (35–91) | 14 (52) |

Altered mental status—26 (96.3) Dysgeusia—1 (3.7) Generalized weakness—1 (3.7) Headache—2 (7.4) Focal Deficit—10 (37.0) Decerebrate posturing—1 (3.7) Facial droop—1 (3.7) Fixed pupils—1 (3.7) Gaze deviation—3 (11.1) Hemineglect—2 (7.4) Hemiparesis or hemiplegia—4 (14.9) Quadriplegia 1 (3.7) |

Imaging and EEG Encephalopathy—20 (74) Acute necrotizing encephalopathy—2 (7) Vasculopathy—5 (19) Subacute ischaemic stroke—4 (14.8) NCSE—1 (3.7) Large vessel occlusion—PCA P2B—1 (3.7) Focal stenosis ICA terminus—3 (11.1) |

NA |

| Abdelkader Mahammedi [47] | Published | Multicentre, Italy | Retrospective observational Study | Feb 29 to April 4 | NA | 725 | Consecutive hospitalized patients | NA | NA |

Acute neurological symptoms—108 (15) Altered mental status—64(8.8) Ischaemic stroke—33(total was 34, but 1 is hypoxic encephalopathy added here) Headache—13 (1.8) Myalgia—13 (1.8) Seizures—10 Dizziness—4(0.6) Neuralgia—3 Ataxia—2 (0.3) Hyposmia—2 (0.3) ICH-6 Hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy—1 Cerebral venous thrombosis—2 GBS—2 MFS—1 PRES—1 Acute encephalopathy—1 Non-specific encephalopathy—2 MS plaque exacerbation—2 |

119 patients had neurological symptoms; however, only 108 received neuroimaging evaluation | NA |

| Alireza Radmanesh [48] | Published | New York University Langone Medical Center, USA | Retrospective observational case series | March 1 and 31, 2020 | 2 weeks | 3661 | All patients diagnosed | NA | NA |

Acute/subacuteinfarct—13 Haemorrhage—7 (excluding previous) Altered mental status—102 (2.9%) Syncope/fall (79 patients Focal neurologic deficit—30 |

242 underwent imaging (CT or MRI) | NA |

| Carlos Manuel Romero-Sánchez [49] | Published | Two centers, Albacete, Spain | Retrospective observational | March 1st to April 1st, 2020 | NA | 841 | All patients admitted | 66.42 ± 14.96 | 473 (56.2) |

Neurological manifestations—483 (57.4) Myalgias −145 (17.2) Headache—119 (14.1) Dizziness—51 (6.1) Syncope—5 (0.6) Anosmia—41 (4.9) Dysgeusia—52 (6.2) Disorders of consciousness—165 (19.6) Seizures—6 (0.7) Dysautonomia—21 (2.5) AIDP—1 HyperCKemia—73 (9.2) Rhabdomyolysis—9 (1.1) Myopathy- 26 (3.1) Ischaemic stroke—11 (1.3) Intracranial hemorrhage—3 (0.4) Movement disorders-6 (0.7) Encephalitis—1 (0.1) Optic neuritis—1 (0.1) Neuropsychiatric symptoms—167 (19.9) |

Non-severe vs severe | Mortality—197 (23.42) |

| Stephane Kremer [50] | Published | French Society of Neuroradiology, 16 hospitals, France | Retrospective cohort study | March 23th, 2020, to April 27th, 2020 | NA | 37 | Severe patients with abnormal MRI Only | 61 (8–78) | 30 (81) |

Headache—4 (11) Seizures—5 (14) Clinical signs of corticospinal tract involvement—4(11) Disturbances of consciousness—27 (73) Confusion—12 (32) Agitation-7(19) Pathological wakefulness in intensive care units-15(41) |

Non-hemorrhagic vs hemorrhagic forms CSF—1 patient’s CSF SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR positive |

Died—5 (14) |

| Pranusha Pinna [51] | Published | Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois, USA | Retrospective observational case series | March 1, 2020, to April 30, 2020 | NA | 50 | Only 50 patients admitted to neurology ward or referred to neurology is studied | NA | NA |

CNS Altered mental status—30 Seizures—13 Headache—12 Short-term memory loss—12 Acute cerebrovascular accident—19 Acute ischaemic stroke—10 Hypoxic ischaemic brain injury—7 ICH—4 Non-aneurysmal SAH—4 PRES—2 TIA—1 PNS Dysautonomia—6 Muscle injury with elevated CK—6 Hypogeusia/dysgeusia—5 Hyposmia—3 Extraocular muscle abnormalities—5 Isolated unilateral facial palsy—3 Paresthesias—1 Ataxia—1 |

Neurological manifestations—7.7% (total patients in the hospital were 650; however, not all evaluated for neurological symptoms, mentioned in the limitations of the study) | NA |

| Álvaro Beltrán-Corbellini [52] | Published | Multicentre (2 centres) Madrid, Spain | Pilot multicentre case-control study | 23rd to 25th March 2020 | NA | 79 | Consecutive patients hospitalized, > 18 years | 61.6 ± 17.4 | 48 (60.8) |

Smell and/or taste disorder—31 (39.2) Smell disorder—25 (31.65) (Most common-anosmia—14/31 (45.7) Taste disorder—28 (35.44) Most common—ageusia14/31 (45.2) |

Case—COVID-19 patients Control—40 historical group of 2019/2020 season influenza patients |

NA |

| Andrea Giacomelli [53] | Published | L. Sacco Hospital in Milan, Italy | Cross-sectional study, verbal in-terview | 19 March 2020 | NA | 59 | All hospitalized patients who were able to be interviewed | 60 (50–74) | 40 (67.8) |

Headache—2 (3.4) Olfactory and/or taste disorders—20 (33.9) Olfactory disorders—14 Taste disorder—17 |

NA | NA |

| Jerome R. Lechien [54] | Published | COVID-19 Task Force of YO-IFOS, Multicentre, Europe | Prospective survey observational case series | NA | NA | 417 | Adult > 18 years, mild to moderate cases (ICU cases excluded) hospitalized and home patients | 36.9 ± 11.4 | 154 (36.9) |

Olfactory dysfunction—357 (85.6) Anosmia—284 (79.6) Hyposmia—73 (20.4) Phantosmia—12.6% Parosmia—32.4% Gustatory disorders—342 (88.8) Reduced/discontinued—78.9% Distorted ability to taste flavors—21.1% |

||

| Giacomo Spinato [55] | Published | Treviso Regional Hospital, Italy | Cross sectional telephone survey | March 19 and March 22, 2020 | NA | 202 | Adults (≥ 18 years) consecutively assessed and mildly symptomatic (only home managed patients) | 56 (45–67) | 97 (48.0) |

Headache—86 (42.6) Muscle or joint pains—90 (44.6) Dizziness—28 (13.9) Altered sense of smell or taste130—(64.4%) |

NA | NA |

| Luigi Angelo Vaira [56] | Published | University Hospital of Sassari, Italy | Prospective case series observational | March 31 and April 6, 2020 | NA | 72 | Adults over 18 years of age (excluded assisted ventilation patients) | 49.2 ± 13.7 | 27 (37.5) |

Headache—30 (41.6) Olfactory and taste disorders—53 (73.6) Olfactory disorder—44 (61.1) Taste disorder—39 (54.2) |

Objective tests used | NA |

| Luigi Angelo Vaira [57] | Published | Multicentre, Italy | Prospective study | April 9th and 10th 2020 | NA | 33 | Health care staff, home quarantined, age > 18 years | 47.2 ± 10 | 11 (33.3) |

Olfactory and taste disorders—21 (63.6) Olfactory disorder—17 (51.5) Taste disorder—17(51.5) |

Validation of a self-administered olfactory and gustatory test done | NA |

| Luigi Angelo Vaira [58] | Published | Multicentre, Italy | Multicentre prospective cohort study | NA | NA | 345 | Both hospitalized and home quarantined patients, ≥ 18 years (excluded assisted ventilation patients) | 48.5 ± 12.8 | 146 (42.3) |

Olfactory and/or taste disorders- 256(74.2) Olfactory disorder-225 Taste disorder-234 |

Objective assessment done | NA |

| Yonghyun Lee [59] | Published | The Daegu Medical Association, South Korea | Prospective telephone interview | March 8, 2020 - March 31, 2020 | NA | 3191 | COVID-19 patients awaiting hospitalization or facility isolation | 44.0(25.0–58.0) | 1161(36.4) |

Anosmia and/or ageusia—488 (15.3) Anosmia—389 Ageusia—353 |

Presence vs absence of anosmia or ageusia | NA |

| Marlene M. Speth [60] | Published | Kantonsspital Aarau, Aarau, Switzerland | Prospective cross-sectional telephone questionnaire study | March 3, 2020, to April 17, 2020 | NA | 103 | All positive (ICU and deceased excluded) | NA | 50 (48.5) |

Olfactory dysfunction—63 (61.2) Decreased smell—14.6% Anosmia—46.6% Gustatory dysfunction—67 (65.0) Decreased taste-25.2% Ageusia—39.8% |

NA | NA |

| T. Klopfenstein [61] | Published | NFC (Nord Franche-Comté) Hospital, France | Retrospective observational | March 1st to March 17th, 2020 | March 24th, 2020 | 114 | All admitted adults | NA | NA |

Anosmia—54 (47) Dysgeusia—46/54 (85) Myalgia—40/54 (74) Headache—44/54 (82) |

NA | Death—2/54(4) |

| Dawei Wang [10] | Published | Single centre,Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University in Wuhan, China | Retrospective, case series | January 1 to January 28, 2020 | Till Feb. 3rd | 138 | Consecutive patients admitted | 56 (42–68) | 75 (54.3) |

Myalgia—48 (34.8) Dizziness—13 (9.4) Headache—9 (6.5) |

ICU vs non-ICU | NA |

| Wei-jie Guan [11] | Published | Multicentre, 30 provinces in China | Retrospective study | December 11, 2019, to January 31, 2020 | NA | 1099 | All patients with data available | 47.0 (35.0–58.0) | 637/1096 (58.1) |

Headache—150 (13.6) Myalgia or arthralgia—164 (14.9) Rhabdomyolysis—2 (0.2) |

All Severe vs non-severe |

Death—15 (1.4) Discharged—55 (5.0) Hospitalization—1029 (93.6) Recovery—9 (0.8) |

| Nanshan Chen [12] | Published | Jinyintan Hospital, Wuhan, China | Retrospective study | Jan 1 to Jan 20, 2020 | Till Jan 25,2020 | 99 | All hospitalized patients | 55·5 ± 13·1 | 67 (68) |

Muscle ache—11 (11) Headache—8 (8) Confusion—9 (9) |

NA |

Remained in .hospital—57 (58) Discharged—31 (31) Died—11 (11) |

| Chaolin Huang [62] | Published | Jin Yintan Hospital, Wuhan, China | Prospective cohort | Dec 16, 2019, to Jan 2, 2020 | NA | 41 | Hospitalized | 49·0 (41·0–58·0) | 30 (73) |

Myalgia or fatigue—18 (44) Headache—3/38 (8) |

ICU vs non-ICU |

Hospitalization—7 (17) Discharge—28 (68) Death—6 (15) |

| ChaominWu [63] | Published | Jinyintan Hospital Wuhan, China | Retrospective cohort | December 25, 2019- and January 26, 2020 | February 13, 2020 | 201 | All hospitalized patients | 51 (43–60) | 128 (63.7) | Fatigue or myalgia—65 (32.3) | ARDS vs non-ARDS |

Death—44 (21.9) Discharged—144(71.6) |

| Xiaobo Yang [64] | Published | Jin Yin-tan Hospital, Wuhan, China | Retrospective, observational study | Dec 24, 2019, to Jan 26, 2020 | Feb 9, 2020 | 52 | Only critically ill patient admitted in ICU | 59·7 (13·3) | 35 (67) |

Myalgia—6 (11·5) Headache—3 (6) |

Survivors vs non-survivors |

Died—32 (61·5) Discharged—8 Hospitalized—12 |

| Tao Chen [65] | Published | Tongji Hospital, Wuhan, China | Retrospective case series | 13 January- 12 February 2020 | 28 February 2020 | 274 | 113 died and 161 fully recovered and discharged patients | 62.0 (44.0–70.0) | 171 (62) |

Myalgia—60 (22) Headache—31 (11) Dizziness—21 (8) Hypoxic encephalopathy—24 (9) |

Deaths vs recovered | 113 died,161 fully recovered |

| Yingzhen Du [66] | Published | 2 centres, Hannan Hospital and Wuhan Union Hospital Wuhan, China | Retrospective, observational study | January 9 to February 15, 2020 | February 15, 2020 | 85 | Consecutive severe patients | 65.8 ± 14.2 | 62 (72.9) |

Myalgia—14 (16.5) Headache—4 (4.7) |

NA | Died—85 |

| Yongli Zheng [67] | Published | Chengdu Public Health Clinical Medical Center, Chengdu, China | Retrospective case series | January 16 to February 20, 2020 | February 23, 2020 | 99 |

Consecutively hospitalized All ages |

49.40 ± 18.45 | 51(52) | Muscle ache and headache—12 (12) | Critically ill vs non-critically ill | NA |

| Alfonso J. Rodriguez-Morales [68] | Published | Chile | Cross sectional | March 3, 2020, to March 23, 2020 | NA | 922 | First notified cases of COVID-19 | NA | NA |

Headache—597 (64.8) Myalgia—32 (3.5) |

NA | NA |

| Feng Wang [69] | Published | Tongji Hospital Wuhan, China | Retrospective study | January 29, 2020, to February 10, 2020 | February 22, 2020 | 28 | Diabetic, hospitalized patients | 68.6 ± 9.0 | 21(75) | Headache—3 (10.7) | ICU vs non-ICU |

Died—12 Discharged—12 Hospitalized—4 |

| Suxin Wan [70] | Published |

Chongqing University Three Gorges Hospital, Chongqing, China |

Retrospective case series | 23 January - 8 February 2020 |

8 February 2020 |

135 | Hospitalized patients | 47 (36–55) | 72 (53.3) |

Myalgia or fatigue—44 (32.5) Headache—24 (17.7) |

Mild vs severe |

Hospitalization—120 (88.9) Discharge—15 (42.9) Death—1 (0.7) |

| Zhongliang Wang [71] | Published | Union hospital, Wuhan, China | Retrospective case series | January 16 to January 29, 2020 | February 4, 2020 | 69 | Hospitalized patients | 42.0(35.0–62.0) | 32(46) |

Myalgia-21 (30) Headache-10 (14) Dizziness—5 (7) |

Spo2 < 90 vs Spo2_ > 90 |

Hospitalization—44(65.7) Discharge—18 (26.9) Death—5 (7.5) |

| Dan Sun [72] | Published | Wuhan Children’s Hospital, Wuhan, China | Case series | January 24 to February 24 | February 24, 2020 | 8 | Pediatric ICU (severe and critically ill only) | 2 months to 15 years | 6 |

Myalgia or fatigue—1 Headache—1 |

NA |

Hospitalized—3 Discharged—5 |

| Sijia Tian [73] | Published | Multicentre, 57 hospitals, Beijing, China | Retrospective study | Jan 20 to Feb 10, 2020 | Feb 10, 2020 | 262 | Hospitalized, all age groups | 47.5 (1–94) | 127 (48.5) | Headache—17 (6.5) | Severe vs common (mild, asymptomtic, non-pneumonia) |

Discharge—45 (17.2) Hospitalization—214 (81.7) Death—3 (0.9) |

| Fei Zhou [74] | Published | 2 centers, Jinyintan Hospital and Wuhan Pulmonary Hospital, Wuhan, China | Retrospective cohort | Dec 29, 2019, to Jan 31, 2020 | NA | 191 | All adult ≥ 18 hospitalized and either dead or discharged patients | 56·0 (46·0–67·0) | 119 (62) | Myalgia—29 (15) | Non-survivor vs survivor |

Discharged—137 Died—54 |

| Na Du [75] | Published | First Affiliated Hospital of Jilin University, Jilin, China | Case series | 23 January 2020, to 11 February 2020 | NA | 12 | Consecutive hospitalized patients | 45.25(23–79) | 7(54.3) | Headache—3 (20) | NA | NA |

| Kui Liu [76] | Published | 9 tertiary hospitals, Hubei province, China | Retrospective study | December 30, 2019, to January 24, 2020 | NA | 137 | Hospitalized patients | 57 (20–83) | 61 (44.5) |

Myalgia or fatigue—44(32.1) Headache—13(9.5) |

NA |

Discharged-—44 (32.1) Hospitalized—77 (56.2) Death—16 (11.7) |

| Alma Tostmann [77] | Published | Netherlands | Online anonymous questionnaire | 10 March to 29 March 2020 | NA | 90 | Only health care workers | NA | 19 (21.1) |

Anosmia—37/79 (46.8) Muscle ache—57/90 (63.3) Headache—64/90 (71.1) |

Symptomatic health care workers positive vs negative | NA |

| Yongli Yan [78] | Published | Tongji Hospital, Wuhan, China | Retrospective, observational | January 10, 2020, to February 24, 2020 | NA | 193 | Adults over 18 years, hospitalized, severe (all hospitalized admitted there included) | 64 (49–73) | 114 (59.1) | Headache—21 (10.9) | 48 diabetic vs 148 non-diabetic, survivors vs non-survivors | Mortality—108 (56.0) |

| Xiao-Wei Xu [79] | Published | Multicentre, Zhejiang province, China | Retrospective case series | 10 January 2020, to 26 January 2020 | NA | 62 | Adult hospitalized patients | 41 (32–52) | 35 (56) |

Myalgia or fatigue—32 (52) Headache—21 (34) |

Symptom onset > 10 days vs < 10 days |

Hospital admission—61 (98) Discharge—1 (2) Death—0 |

| Jiang-shan Lian [80] | Published | Health Commission of Zhejiang Province Multicentre, Zhejiang province, China | Retrospective study | Jan 17 to Feb 7, 2020 | Feb. 12, 2020 | 788 | All confirmed cases | NA | 407(51.65) |

Muscle ache—91(11.54) Headache—75(9.52) |

With Wuhan exposure vs without |

Discharged—322 (40.86) Death—0 |

| Nitesh Gupta [81] | Published | Safdarjung Hospital, India | Retrospective observational case series | Feb 1st to 19th march 2020 | 19th March 2020 | 21 | First 21 hospitalized patients in the centre | 40.3 (16–73) | 14 (66.7) | Headache—3 (13.6) | NA | Discharged—15 |

| Xiaoli Zhang [82] | Published | Health Commission of Zhejiang Multicentre, Zhejiang, China | Retrospective study | January 17 to February 8 | NA | 645 | All hospitalized patients | NA | 328(50.85) |

Muscle ache-71(11.01) Headache-67(10.39) |

Normal imaging vs abnormal imaging | NA |

| Jie Li [83] | Published | Dazhou Central Hospital, Dazhou, China | Retrospective case series | 22 January 2020, to 10 February 2020 | 11 February 2020 | 17 | All hospitalized patients |

45.1 ± 12.8 45 (22–65) |

9 (52.9) |

Myalgia—4 (23.5) Dizziness—2 (11.8) |

Discharged vs non-discharged |

Discharged—5 Hospitalized—12 |

| Ivan Fan-Ngai Hung [84] | Published | Multicentre, Hong Kong, China | Prospective, open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial | Feb 10 to March 20, 2020 | NA | 127 | Adult at least 18 years, admitted | NA | 68 (53.54) |

Myalgia—18 (14.17) Headache—6 (4.72) Anosmia—5 (3.93) |

Combination triple antiviral drug vs control group(lopinavir–ritonavir) | Death-0 |

| Huan Wu [85] | Published | Wuhan Children’s Hospital, Wuhan, China | Retrospective case series | January 25 to April 18, 2020 | April 18, 2020 | 148 | Pediatric mild and moderate cases only | 84 (18–123)months | 60 (40.5) | Headache—5 (3.4) | NA |

Discharged—148 (100) Died—0 |

| Michael G Argenziano [86] | Published | NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, USA | Retrospective review | 1 March to 5 April 2020 | 30 April | 1000 | First 1000 consecutive patients presented to centre | 63.0 (50.0–75.0) | 596 (59.6) |

Myalgia—268 (26.8) Headache—101 (10.1) Syncope—48 (4.8) |

Emergency vs ward vs ICU |

Discharged—699 Died—211 Hospitalized—90 |

| Simone Bastrup Israelsen [87] | Published | Hvidovre Hospital, Denmark | Retrospective case series | 10 March to 23 April 2020 | NA | 175 | Consecutive patients, adult ≥ 18, hospitalized | 71 (55–81) | 85 (48.6) |

Myalgia—46 (26.3) Headache—32 (18.3) Altered sense of taste—5 (2.9) |

General Ward vs ICU |

On April 20th Hospitalized—23 (13.1) Discharged—109 (62.3) Died—43 (24.6) |

| Matthew J Cummings [88] | Published |

NewYork-Presbyterian hospitals affiliated with Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, USA |

Prospective observational cohort | March 2 to April 1, 2020 | April 28, 2020 | 257 | Only critically ill adults aged ≥ 18 years | 62 (51–72) | 171 (67) |

Myalgia- 67 (26) Headache—10 (4) |

NA |

Discharged alive—58 (23) Died −101 (39) Hospitalized—98 (38) |

| Marjolein F. Q. Kluytmans-van den Bergh [89] | Published | 2 teaching Hospitals, Netherlands | Cross sectional | March 12, 2020, and March 16, 2020 (interview dates) | March 16, 2020 | 86 | Only health care workers infected | 49 (22–66) | 15 (17) |

Severe myalgia- 54 (63) Headache—49 (57) Altered or lost sense of taste- 6 (7) |

Interview within 7 d of the onset of Symptoms vs >7d |

Recovered—19 (22) Hospital admission—2 (2) |

| Błażej Nowak [90] | Published | Central Clinical Hospital, Warsaw, Poland | Retrospective study | March 16, 2020, to April 7, 2020 | April 7, 2020 | 169 | Consecutive patients hospitalized | 63.7 ± 19.6 | 87 (51.5) |

Headache—1 Anosmia and ageusia—3 (1.7) |

Survivors vs non-survivors |

Hospitalized—80(45.7) Discharged home or to isolation areas—46 (26.3) Died—46 (26.3) |

| Xiaoquan Lai [91] | Published | Tongji Hospital Wuhan | Retrospective case series | January 1 to February 9, 2020 | NA | 110 | Only health care workers | 36.5 (30.0–47.0) | 31 (28.2) |

Myalgia or fatigue—66 (60.0) Muscle ache- 50 (45.5) Headache—33 (30.0) Dizziness—24 (21.8) |

Hcw with COVID-19 vs without | Died—1 (0.9) |

| X. Wang [92] | Published | Dongxihu Fangcang Hospital, Wuhan, China | Retrospective study | 7 February to 12 February 2020 | 22 February | 1012 | Only non-critically ill (however, all patient admitted in that hospital included) | 50 (39–58) | 524 (51.8) |

Headache—152 (15.0) Myalgia—170 (16.8) |

With and without aggravation during follow up |

Died—0 Discharge—93 (9.2) Hospitalized or transferred to another hospital—919 (90.8) |

| Zhe Liu [93] | Published | Multicentre Xi’an, Shaanxi province, China | Retrospective study | January 16 to February 13, 2020 | NA | 72 | All hospitalized | 46.2 ± 15.9 | 39 (54.2) |

Muscle soreness—7 (9.7) Headache—4 (5.6) |

Uncomplicated vs mild vs severe |

Discharged—32 Died—0 Hospitalized—40 |

| Qiong Huang [94] | Published | Multicentre, Hunan, China | Retrospective case series | January 17 to February 10, 2020 | NA | 54 | All hospitalized patients | 41 (31–51) | 28 (51.9) |

Muscle soreness—9 (16.7) Headache—3 (5.6) Dizziness—3 (5.6) |

Common vs severe | Discharged—54 |

| Kyung Soo Hong [95] | Published | Yeungnam University Medical Center in Daegu, South Korea | Retrospective study | Up to March 29, 2020 | March 29, 2020 | 98 | Consecutive hospitalized patients | 55.4 ± 17.1 | 38 (38.8) | Myalgia—37 (37.8) | ICU vs non-ICU |

Remains in hospital—57 (58.2) Discharged—30 (30.6) Died—5 (5.1) Transferred—6 (6.1) |

| Rui Huang [96] | Published | Multicentre Jiangsu province, China | Retrospective study | January 22, 2020, to February 10, 2020 | February 10, 2020 | 202 | All hospitalised | 44.0 (33.0–54.0) | 116 (57.4) |

Muscle ache—21 (10.4) Headache—12 (5.9) |

Severe vs non-severe |

Remained in hospital—165 (81.7) Hospital discharge—37 (18.3) Death—0 (0) |

| Mengyao Ji [97] | Published | Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University Wuhan, China | Retrospective study | 2nd January to 28 January 2020 | 8 February 2020 | 101 | Random selection of confirmed patients | 51.0 (37.0–61.0) | 48 (48) |

Myalgia—16 (16) Vertigo—4 (4) Headache—6 (6) |

Medica staff vs non-medical |

Death-11 (11) Hospitalization—53 (52) Cured—37 (37) |

| Dawei Wang [98] | Published | Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University in Wuhan and Xishui Hospital, Hubei Province, China | Retrospective study | Up to February 10, 2020 | NA | 107 |

All the discharged (alive at home and dead) patients with confirmed COVID-19(88 patients overlap with Wang D[10]) |

51.0 (36.0–65.0) | 57 (53.3) |

Myalgia—33 (30.8) Headache—7 (6.5) Dizziness—7 (6.5) |

Survivors vs non-survivors |

Died—19 Survived—88 |

| Saurabh Aggarwal [99] | Published | Unity Point Clinic, USA | Retrospective study | March 1 to April 4, 2020 | NA | 16 | All admitted patients | 67 (38–95) | 12 (75) |

Lightheadedness—3 (19) Headache—4 (25) Anosmia—3 (19) Dysgeusia—3 (19) |

ICU, shock, death vs no |

Died—3 (19) Discharged—11 Admitted—2 |

| Xin-Ying Zhao [100] | Published | Jingzhou Central Hospital Jingzhou, China | Retrospective study | January 16, 2020, to February 10, 2020 | February 10, 2020 | 91 | All hospitalized patients | 46.00 | 49 (53.8) |

Myalgia—15 (16.5) Dizziness—3 (3.3) Disturbance of consciousness—3 (3.3) |

Severe vs mild |

Remained in hospital—75 (82.4) Discharged—14 (15.4) Died—2 (2.2) |

| Yifan Meng [101] | Published | Tongji Hospital, Wuhan, China | Retrospective study | January 16th to February 4th, 2020 | March 24th, 2020 | 168 | All consecutive admitted(all were severe or critically ill patients) | 56.7 ± 15.1 | 86 |

Myalgia—48 (28.6) Headache—22(13.1) Dizziness—7(4.2) |

Male vs female |

Died—17(8.9) Discharge—136 Hospital—15 |

| Qingchun Yao [102] | Published |

Dabieshan Medical Center, Huanggang city, Hubei Province, China |

Retrospective cohort | January 30, 2020 -February 11, 2020 | March 3 | 108 (1 pregnant patient excluded as information incomplete) | Consecutive adult patients admitted | 52 (37–58) | 43 (39.8) |

Myalgia or fatigue—28 (25.9) Headache—1 (0.9) |

Non-severe vs severe alive vs severe dead |

Died—12 Discharged—96 |

| Li Zhu [103] | Published | Multicentre, Jiangsu province, China. | Retrospective case series | January 24, 2020, to February 22, 2020 | February 25, 2020 | 10 | 1–18 years, children | NA | 5 (50.0) | Headache—2 (20.0) | NA |

Discharged—5 (50.0) Hospitalized—5 (50.0) |

| Eu Suk Kim [104] | Published | Korea National Committee for Clinical Management of COVID-19, South Korea | Nationwide multicentre retrospective study | January 19th, 2020, to February 17th, 2020 | February 17th, 2020 | 28 | First 28 patients in Republic of Korea, hospitalized | 42.6 ± 13.4 | 15 (53.6) |

Myalgia—7 (25.0) Headache—7 (25.0) |

NA |

Discharged—10 Hospitalized—18 |

| Pavan K. Bhatraju [105] | Published | Multicentre(9), Seattle, USA | Retrospective study | February 24 to March 9, 2020 | March 23, 2020 | 24 | Only critically ill ICU patients | 64 ± 18 (23–97) | 15 (63) | Headache—2 (8) | NA |

Died—12 (50) Discharged—5 (21) Hospitalized—7 (30) |

| Haiyan Qiu [106] | Published | Multicentre (3), Zhejiang, China | Retrospective cohort | Jan 17 to March 1, 2020 | Feb 28, 2020 | 36 | All pediatric 0–16 years | 8·3 ± 3·5 | 23 (64) | Headache- 3 (8) | Mild vs moderate | All cured |

| Guang Chen [107] | Published | Tongji Hospital, Wuhan, China | Retrospective study | Late December 2019 to January 27, 2020 | February 2, 2020 | 21 (available data of symptoms in 20 only) | All hospitalized patients | 56.0 (50.0–65.0) | 17 (81.0) |

Myalgia—8/20 (40.0%) Headache—2/20 (10.0%) |

Severe vs moderate |

Died—4 Recovered—2 |

| Wenjie Yang [108] | Published | Multicentre(3 centers),Wenzhou city, Zhejiang, China | Retrospective cohort | January 17th to February 10th, 2020 | Feb 15th, 2020 | 149 | Consecutive hospitalized patients | 45.11 ± 13.35 | 81 |

Muscle pain—5(3.36%) Headache—13(8.72%) |

NA |

Remained in hospital—76 (51.01) Discharged—73 (48.99) Died—0 (0.0) |

| Yu-Huan Xu [109] | Published | Single centre, Beijing, China | Retrospective study |

January to February 2020 |

NA | 50 | All hospitalized patients | 43.9 ± 16.8 | 29 (58) |

Headache—5 (10) Muscle ache—8 (16) |

Mild vs moderate vs severe vs critically severe | NA |

| Xi Xu [110] | Published | Guangzhou Eighth People’s Hospital, Guangzhou, China | Retrospective study | January 23, 2020, and February 4, 2020 | NA | 90 | All hospitalized patients | 50 (18–86) | 39 (43) |

Myalgia—25 (28) Headache—4 (4) |

NA | NA |

| Jerome R. Lechien [111] | Published | Multicentre, Europe | Observational, cross-sectional study | March 22 to April 10, 2020 | NA | 1420 | Mild to moderate(but all reported) | 39.17 ± 12.09 | 458 (32.3) |

Headache—998 (70.3) Loss of smell—997 (70.2) Reduction of smell—201 (14.2) Myalgia—887 (62.5) Taste dysfunction—770 (54.2) |

Based on age | NA |

| Sherry L. Burrer [112] | Published |

CDC COVID-19 Response Team, United states, USA |

Retrospective study | February 12 to April 9, 2020 | NA |

9282 (symptom data for 4707) (age data for 8945) (sex data for 9067) |

Cases reported to CDC, only health care personal | 42 (32–54) | 2464(27) |

Muscle ache—3122(66) Headache—3048(65) Loss of smell or taste—750(16) |

NA |

Data of 8945 Not hospitalized—6760 (90%) Hospitalized—723 (8–10%) ICU admission—184 (2–5%) Died—27 (0.3–0.6%) |

| Ruth Levinson [113] | Published | Tel Aviv Medical Center, Israel | Retrospective with questionnaire via mobile and email | March 10 to 23, 2020 | 25th of March | 42 (total 45 admitted, only 42 completed questionnaire) | Hospitalized adults and adolescents (age ≥ 15 years), and mild symptoms (all admitted were mild) | 34 (15–82) | 23 |

Myalgia or arthralgia—24 (57) Headache—20 (48) Anosmia—14 (33) Dysgeusia—15 (36) Dizziness—9 (21) |

NA | NA |

| Xu Zhu [114] | Preprint | Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, China | Retrospective study | January 20 to February 15, 2020 | February 20, 2020 | 114 | Only elderly(> 70) patients | 76 (72–82) | 67 (58.8) | Myalgia—4 (3.5) | Severe vs non-severe |

Alive—87 (76.3) Dead—27(23.7) |

| Dan Wang [115] | Preprint | Zhongshan Hospital, Wuhan, China | Cross-sectional study | January 15, 2020-February 28, 2020 | NA | 143 | All consecutive admitted patients | 58(39–67) | 73(51.0) |

Myalgia—49(34.3) Headache—7(4.9) |

Mild/moderate vs severe/critical | NA |

| Chuming Chen [116] | Preprint | Shenzhen Third People’s Hospital, Guangdong, China | Prospective study | Jan 16, 2020, to Feb 19, 2020 | NA | 31 | Only pediatric, < 18 years, hospitalized patients | 7.33 ± 4.35 | 13 (41.9) | Headache—1 (3.2) | NA | Died—0 |

| Pingzheng Mo [117] | Published | Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, China | Retrospective study | January 1st to February 5th | NA | 155 | All Consecutive admitted patients | 54 (42–66) | 86 (55.5) |

Myalgia or arthralgia—50 (61.0) Headache-8 (9.8) Dizziness-2 (2.4) |

General vs refractory | NA |

| Gu-qin Zhang [118] | Published | Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, China | Retrospective case series | January 2, 2020, to February 10, 2020 | Feb 15, 2020 | 221 | All hospitalized patients | 55.0 (39.0–66.5) | 108(48.9) | Headache—17(7.7) | Severe vs non-severe |

Hospitalization—168 (76.0) Discharge—42 (19.0) Death—12 (5.4) |

| Jennifer Tomlins [119] | Published | North Bristol NHS Trust, UK | Retrospective study | March 10th to March 30th, 2020 | April 6th | 95 | All sequential hospitalized patients | 75 (59–82) | 60 (63) |

Myalgia—13 (14) Confusion—20 (21) Seizure—1 (1.1) Headache—9 (9.5) Anosmia—3 (3.2) |

NA | Died—21 (21) Discharged—44(43) Hospitalized—30 (29) |

| Zonghao Zhao [120] | Preprint | First Affiliated Hospital of USTC Hefei, China | Retrospective study | Jan 21 to Feb 16, 2020 | NA | 75 | All positive cases | 47 (34–55) | 42 (56) |

Muscle soreness—9 (12.00) Headache —5 (6.67) |

NA | NA |

| Ying Huang [121] | Preprint | Fifth Hospital of Wuhan, Wuhan, China | Retrospective study |

Jan 21 - Feb 10, 2020 |

Feb 14, 2020 | 36 | Non survivors only | 69.22 (9.64) | 25 (69.44) |

Myalgia—1 (2.78) Disturbance of consciousness—8 (22.22) |

NA | Died—36 |

| Carol H. Yan [122] | Published | University of California San Diego Health, La Jolla, California, USA | Cross-sectional internet- and email-based platform | March 3, 2020, and March 29, 2020 | NA | 59 | All positive COVID-19 who completed survey(most are mild cases) | NA | 29 (49.2) |

Headache—39 (66.1) Myalgia/arthralgia—37 (62.7) Ageusia—42 (71.2) Anosmia- 40 (67.8) |

With subjective olfaction score COVID-19 vs non-COVID-19 |

NA |

| Yan Deng [123] | Published | 2 centers, Wuhan, China | Retrospective study | January 1, 2020, to February 21, 2020 | NA | 225 | Only dead and recovered patients admitted | NA | 124 |

Myalgia or fatigue—57 Headache—13 (11.5) |

Death group vs recovered group |

Died—109 Recovered—116 |

| Jiaojiao Chu [124] | Published | Tongji Hospital, Wuhan, China | Retrospective study | 7 January to 11 February 2020 | NA | 38 | Only medical staff(54 tested, but only 38positve for nucliec acid tests) | 39 (26–66) | 24 (63.2) | Muscle ache—2 (5.3) | Common vs severe, positive RT-PCR vs negative | NA |

| Håkon Ihle-Hansen [125] | Published | Bærum Hospital, Norway | Observational qualitative study | 9–31 March 2020 | 31 March 2020 | 42 (1 pt. from 43 not included as asymptomatic and tested due to exposure) | All consecutive admitted | 72.5 (30–95) | 28 (67) | New-onset confusion—8 (19) | Severe vs critical | NA |

| Parag Goyal [126] | Published | 2 centres, New York, USA | Retrospective case series | March 3 to March 27, 2020 | April 10th | 393 | First consecutive patients hospitalized, adults ≥ 18 years | 62.2 (48.6–73.7) | 238 (60.6) | Myalgia—107 (27.2) | Invasive mechanical ventilation vs no invasive mechanical ventilation |

Died—40 (10.2) Discharged—260 (66.2) Outcome data incomplete—93 (23.7) |

| Jianlei Cao [127] | Published | Wuhan University Zhongnan Hospital, Wuhan, China | Retrospective cohort | 3 January to 1 February 2020 | 15 February 2020 | 102 | All patients admitted | 54 (37–67) | 53 | Muscle ache—35(34.3) | Non survivors vs survivors |

Discharge—85 (83.3) Died—17(16.7) |

| De Chang [128] | Published | Multicentre (3 centers), Beijing, China | Case series | January 16, 2020, to January 29, 2020 | February 4, 2020 | 13 | All hospitalized patients | 34 (34–48) | 10 (77) |

Myalgia—3 (23.1) Headache—3 (23.1) |

NA | All recovered (12 still quarantined) |

| Huijun Chen [129] | Published | Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, China | Retrospective case series | Jan 20 to Jan 31, 2020 | Feb 4, 2020 | 9 | Only pregnant patients | 26–40 years | NA | Myalgia—3 (33%) | NA |

All nine live birth Died—0 |

| Lang Wang [130] | Published | Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, China | Retrospective study | Jan 1 to Feb 6, 2020 | March 5 | 339 | Consecutive cases over 60 years old | 69 (65–76) | 166(49) |

Myalgia—16 (4.7) Dizziness—13 (3.8) Headache—12 (3.5) |

Survival vs dead |

Discharged—91(26.8) Hospitalized—183(54.0) Died—65(19.2) |

| Gianfranco Spiteri [131] | Published | WHO European Region(except UK), Europe | Cross-sectional study | 24 January to 21 February 2020 | 21 February 2020 | 31 (total 38, but for symptoms data available for 31 only) | First cases in the WHO European region except UK | 42(2–81) | 25 |

Headache—6 Myalgia—1 (3.22) |

Infected in Europe vs china | Died—1 |

| Yingxia Liu [132] | Published | Shenzhen Third People’s Hospital, China | Case series | Jan 11 to Jan 20, 2020 | NA | 12 | Patients admitted | 10–72 years | 8 | Myalgia—4(33.3) | NA | NA |

| Tianmin Xu [133] | Published | Third Hospital of Changzhou, Changzhou city, Jiangsu province, China | Retrospective cohort | Jan 23 to February 18,2020 | February 27, 2020 | 51 | Patients admitted | NA | 25 | Myalgia—8(15.7) | Imported vs secondary vs tertiary (1 patient diagnosed with anal swab) | NA |

| Michael Chung [134] | Published | Multicentre (3 centers), 3 provinces, China | Retrospective case series | January 18, 2020, to January 27, 2020 | NA | 21 | Admitted patients who underwent chest CT | 51 ± 14 | 13 (62) |

Headache—3 (14) Muscle soreness—3 (14) |

NA | NA |

| Heshui Shi [135] | Published | Wuhan Jinyintan hospital or Union Hospital of Tongji Medical College, China | Retrospective study | Dec 20, 2019, to Jan 23, 2020 | Feb 8th, 2020 | 81 | Admitted and had CT chest done | 49·5 ± 11·0 | 42 (52) |

Headache—5 (6) Dizziness—2 (2) |

NA | NA |

| Luhuan Yang [136] | Published | Yichang Central People’s Hospital, Yichang, Hubei Province, China | Retrospective study | Jan 30 to Feb 8, 2020 | Feb 26, 2020 | 200 | All admitted patients | 55 ± 17.1 | 98 (49.0) |

Myalgia or malaise—44 (22.0) Headache 27—(13.5) |

ICU vs non-ICU |

Hospitalization—143 (71.5) Discharge—42 (21) Death—15 (7.5) |

| Wei Zhao [137] | Published | Multicentre (4 centers),Hunan, China | Retrospective study | NA | NA | 101 | Consecutive laboratory confirmed COVID-19 who underwent CT | 44.44(17–75) | 56 (55.4) | Myalgia or fatigue—17 (16.8) | Emergency vs non-emergency group | NA |

| Ya-nan Han [138] | Published | Xian eighth hospital Shaanxi, China | Retrospective study | 31st January-16th February 2020 | NA | 32 | All admitted patients | NA | 16 | Myalgia or fatigue-13(all adults) |

Only 30/32 (93.8%) lab confirmed (2 included based on clinical and epidemiological evidence) Paediatrics vs adults |

Discharged—32 |

| Yang Wang [139] | Published | Tongji Hospital, China | Cohort | January 25, 2020, to February 25, 2020 | 28 days follow-up | 344 | Severely and critically ill (ICU) | 64 (52–72) | 179 (52.0) | Rhabdomyolysis—9 (2.6) | Survivors vs non-survivors |

Died—133 (38.7) Discharged—185 (87.7) Hospitalized—26 |

Neurological manifestations

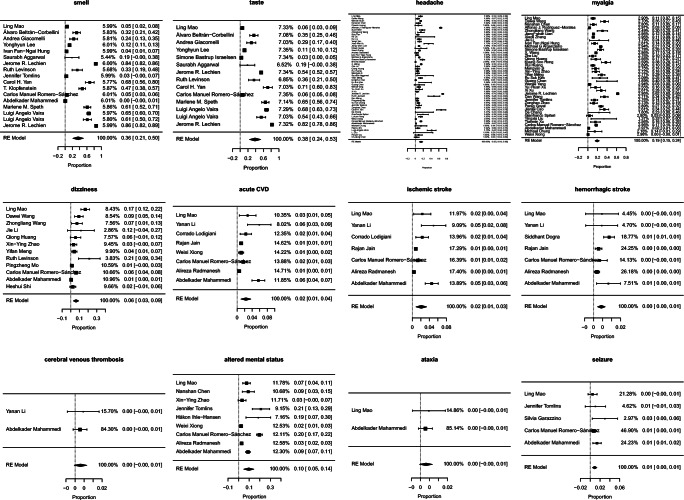

Neurological manifestations have been reported in patients with COVID-19 from all over the world. A multicentre, retrospective study by Mao et al. [32] was the first study to evaluate the neurological manifestations in COVID-19 and found that neurological manifestations were present in 36.4% of total 214 patients, out of which most common was CNS manifestations(24.8%) followed by peripheral nervous system manifestations(8.9%). Other large retrospective observational studies reported the incidence of neurological manifestations as 4.3% [45], 15% [47], and 57.4% [49]. The most common neurological manifestations reported in COVID-19 were smell disturbances, taste disturbances, headache, myalgia, and disturbances in consciousness/altered mental status. The prevalence of all the neurological manifestations assessed is given in Table 2. A summary estimate of pooled prevalence and heterogeneity of each neurological manifestation are given in Table 3. Forest plot and funnel plot is given in Figs. 2 and 3 respectively.

Table 2.

Prevalence of neurological manifestations reported from systematic assessment

| Studies (N) | Sample size (N) | Cases (n) | Prevalence (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smell disturbances | 17 | 7919 | 2488 | 31.4% (30.4–32.4) |

| Taste disturbances | 14 | 7033 | 1979 | 28.1% (27.1–29.2) |

| Headache | 54 | 13,623 | 2751 | 20.2% (19.5–20.9) |

| Myalgia | 38 | 11,169 | 2288 | 20.5% (19.7–21.2) |

| Disturbances in consciousness/altered mental status | 9 | 6687 | 408 | 6.1% (5.5–6.7) |

| Syncope | 3 | 1000 | 56 | 5.6% (4.3–7.2) |

| Dizziness | 12 | 2595 | 137 | 5.3% (4.5–6.2) |

| Acute cerebrovascular disease | 8 | 10,186 | 148 | 1.4% (1.2–1.7) |

| Ischaemic stroke | 7 | 9268 | 108 | 1.2% (1.0–1.4) |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 7 | 12,704 | 60 | 0.5% (0.4–0.6) |

| Cerebral venous thrombosis | 2 | 946 | 3 | 0.3% (0.1–0.9) |

| Seizures | 5 | 2043 | 23 | 1.1% (0.7–1.7) |

| Ataxia | 2 | 939 | 3 | 0.3% (0.1–0.9) |

Table 3.

Meta-analysis, summary estimate of pooled prevalence and heterogeneity of each neurological manifestations

| Number of studies (N) | Summary estimate (%) | 95% CI | I2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smell disturbances | 17 | 35.8 | (21.4, 50.2) | 99.87 |

| Taste disturbances | 14 | 38.5 | (24.0, 53.0) | 99.65 |

| Headache | 54 | 14.7 | (10.4, 18.9) | 99.09 |

| Myalgia | 38 | 19.3 | (15.1, 23.6) | 98.98 |

| Disturbances in consciousness/altered mental status | 9 | 9.6 | (4.9, 14.3) | 98.26 |

| Dizziness | 12 | 6.1 | (3.1, 9.2) | 93.44 |

| Acute cerebrovascular disease | 8 | 2.3 | (1.0, 3.6) | 96.61 |

| Ischaemic stroke | 7 | 2.1 | (0.9, 3.3) | 96.67 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 7 | 0.4 | (0.2, 0.6) | 62.36 |

| Cerebral venous thrombosis | 2 | 0.3 | (0.1, 0.6) | 0.00 |

| Syncope | 3 | 1.8 | (0.9, 4.6) | 98.48 |

| Ataxia | 2 | 0.3 | (0.1, 0.7) | 0.00 |

| Seizure | 5 | 0.9 | (0.5, 1.3) | 9.03 |

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of each neurological manifestations

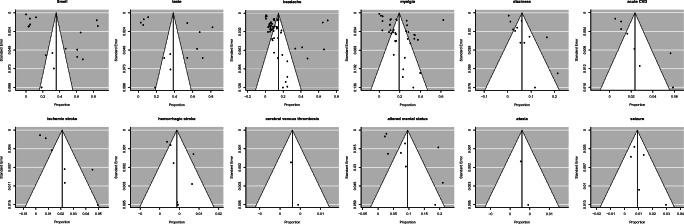

Fig. 3.

Funnel plot for assessing publication bias of each neurological manifestations studied

Smell and taste disturbances

The overall incidence of smell disturbances in the studies ranged from 4.9–85.6% [49, 54] and the most common type of smell disturbance was anosmia. Other smell disturbances noticed were hyposmia, phantosmia, and parosmia [54]. Similarly, the incidence of taste disturbances reported was 0.3–88.8% [47, 54] and the most commonly reported were dysgeusia and ageusia. In the meta-analysis, we found 17 and 14 studies, which assessed the prevalence of smell and taste disturbances respectively and disturbances of smell (35.8%; 95%CI 21.4–50.2) and taste (38.5%; 95%CI 24.0–53.0) sensation were the most common neurological manifestation followed by non-specific neurological manifestations.

A case-control study of 79 COVID-19 patients and 40 historical controls of influenza patients from Spain [52] revealed that new-onset smell and taste disorders were significantly higher in the COVID-19 group. Patients in COVID-19 were significantly younger. Another study reported olfactory and taste disturbances occur more frequently in females than males [53]. Lechien et al. [54], Gilani S et al. [140], and Rachel Kaye et al. [141] reported that anosmia can be the initial and early manifestations of COVID-19. Population surveys on new-onset olfactory dysfunction from Iran [142] and UK [143] have reported an increase in olfactory dysfunction during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Non-specific symptoms

The most common non-specific neurological symptoms reported in SARS-CoV-2 infection were myalgia, headache syncope, and dizziness. The overall pooled prevalence estimate of the proportion of cases are given in Table 3. Incidence of myalgia reported in various studies ranged from 1.8–62.5% [47, 111], headache from 0.6–70.3% [90, 111], and dizziness from 0.6–21% [47, 113]. In children, myalgia and dizziness were less common and rarely reported. In health care workers, the incidence of myalgia, headache, and dizziness was higher compared with the general population. Syncope was reported in three studies with incidence of 0.3% [45], 0.6% [49], and 4.8% [86]. Few studies showed an increase in creatine kinase, LDH, and myoglobin in COVID-19 patients [12, 62, 66].

Acute cerebrovascular disease

Acute cerebrovascular disease (CVD) was reported in 0.5–5.9% [33, 48] of COVID-19 patients. Out of them, the most common type was acute ischaemic stroke and severe COVID-19 patients were more at risk of developing the acute CVD [33]. From these studies, the incidence of acute CVD in severe/ICU patients reported were 0.8–9.8% [33, 41]. The incidence of ischaemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, and cerebral venous thrombosis reported from various studies ranged from 0.4–4.9% [33, 48], 0.2–0.9% [38, 48], and 0.3–0.5% [33, 47] respectively. A study by Mao et al. [32] reported that two patients presented with hemiplegia without any typical COVID-19 symptoms. The median time to onset of cerebrovascular disease was 9 days. Another study by Li Y et.al [33] showed that acute CVD was more likely to be present with severe COVID-19; however, they were older, and had cardiovascular risk factors. These findings were similar to the above study by Mao et al. [32]. In both these studies, the laboratory parameters in patients with CNS symptoms were different from the other COVID-19 patients, with a higher white cell and neutrophil counts, reduced lymphocyte and platelet counts, elevated CRP and D-dimer levels [32, 33].

We found two studies that specifically studied the thrombotic complications in COVID-19 patients and found acute ischaemic stroke in COVID-19 patients receiving thromboprophylaxis [35, 36]. A retrospective observational case series in COVID-19 patients from Italy [144] reported six cases of stroke, four were ischaemic and two were hemorrhagic. Five of them had pre-existing vascular risk factors. Three patients with ischaemic stroke and one patient with hemorrhagic stroke showed hypercoagulable blood parameters [144]. Two studies reported six cases of stroke in young(< 50 years) COVID-19 patients, out of which three patients did not have any risk factors [145, 146]. Also there are multiple case reports and case series of ischaemic stroke including large artery [147], aneurysmal [148, 149] and non-aneurysmal SAH [51], deep cerebral venous thrombosis [150–157], hemorrhagic stroke [38, 158, 159] and CNS vasculitis [160] from all over the world in COVID-19 patients [38, 51, 147–173].

Meningoencephalitis, encephalopathy, disturbances in consciousness

Several cases of meningoencephalitis and encephalopathy were reported in COVID-19 patients [39, 43, 49, 174–183]. The incidence of encephalitis reported in two retrospective studies was 0.03% [43] and 0.1% [49]. Only in four of the 15 reported cases of encephalitis, CSF RT-PCR test was positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA, and surprisingly two cases among them had negative nasopharyngeal swab [50, 174–176]. Two reports showed elevated levels of cytokines like IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, β2-microglobulin, IP-10, MCP-1 in CSF [177, 181]. Interestingly, fluid from the surgical evacuation of subdural hematoma was positive for SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR in a COVID-19 patient [184]. Isolated meningoencephalitis without any respiratory involvement has also been reported [175, 185]. Another case of rhombencephalitis as a rare complication of COVID-19 patient has been reported [186]. Few retrospective studies [32, 47, 49] reported seizures with the incidence ranging from 0.5–1.4% [32, 47]. Cases of all types of seizures like febrile seizures [42], focal seizures [180, 187–189], generalized tonic-clonic seizures [183, 190–192], myoclonic status epilepticus [193], status epilepticus [188, 194] and non-convulsive status epilepticus [46] were reported in COVID-19 patients.

Generally, the SARS-CoV-2 virus causes mild disease in children. However, a study from Italy showed a total five patients with seizures, and out of them, two had febrile seizures (three children had a known history of epilepsy, one child had a history of febrile seizures, one child had a first episode of febrile seizures) [42]. Also, a case of a 6-week-old infant with SARS-CoV-2 in addition to rhinovirus, presenting with brief 10–15-s episodes of upward gaze and bilateral leg stiffening was reported with normal EEG and MRI brain [195]. Another case of an 11-year-old child with COVID-19 viral encephalitis has been reported, with CSF showing viral encephalitis picture [194].

PRES syndrome has also been reported in studies [47, 51]. Transient cortical blindness like presentation of PRES syndrome with MRI brain at admission revealing bilateral T2/FLAIR hyperintensities, especially left occipital, frontal cortical white matter and splenium of the corpus callosum and diffusion restriction in DWI revealing vasogenic edema has been reported [196]. Repeat MRI after 2 weeks showed a complete resolution of findings. Cases of acute necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalopathy [191, 197], hypoxic brain injury with encephalopathy [43, 47, 51, 65], delayed post-hypoxic leukoencephalopathy [198], mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion(MERS) [199], ADEM in elderly females [200, 201], MS plaque exacerbation [47] and CIS [176] were reported in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients.

Incidence of disturbances of consciousness/delirium ranged from 3.3–19.6% [49, 100] in retrospective studies. S.R. Beach, et al. [202] reported four cases of elderly COVID-19 patients, who presented to the hospital with altered mental status without any respiratory complaints, and only one among them developed respiratory complaints during the hospital stay. Similar cases have been reported in elderly patients from Saudi Arabia [203], Norway [204] and China [205]. An observational case series from France [39] in 58 COVID-19 patients with ARDS admitted in ICU reported agitation in 40(69%) patients, confusion in 26 of 40 patients, diffuse corticospinal tract signs in 39 patients (67%) and out of the 45 patients discharged, 15(33%) had a dysexecutive syndrome. MRI Brain showed enhancement of leptomeningeal spaces in eight patients, bilateral frontotemporal hypoperfusion in 11 patients who underwent perfusion imaging, two asymptomatic patients with small acute ischaemic stroke and one patient with subacute ischaemic stroke.

Guillain-Barré syndrome

There are multiple reports of GBS in patients with confirmed COVID-19. GBS has also been reported to be a presenting feature in one case report by Zhao H et al. [206] where the patient, later on, developed fever and other symptoms of COVID-19. All the variants of GBS like AIDP, AMAN, AMSAN has been reported in COVID-19 patients [47, 206–219] including both para [206–212, 220–223] and post-infectious pattern [210, 211, 214–219, 224–226]. Toscano et al. [227] reported a series of five patients of COVID-19 with GBS, with the interval between the onset of fever, cough and symptoms of GBS ranging from 5 to 10 days. Cases of MFS were also reported [47, 226, 228, 229]. One case of MFS was associated with a positive serum GD1b-IgG antibody [228]. Other rare variants reported were GBS/MF overlap syndrome [219], AMSAN variants with severe autonomic neuropathy [219], facial diplegia [222, 227] and post-infectious pattern of the demyelinating type of GBS with brainstem and cervical leptomeningeal enhancement [225]. Cranial neuropathies with abnormal perineural or cranial nerve findings [230], multiple cranial neuropathies [211, 219], peripheral motor neuropathy [231] and ataxia [32, 43, 51] are all reported as presentations of COVID-19.

Other neurological manifestations

The incidence of rhabdomyolysis has been reported between 0.2–2.6% in different studies [11, 49, 139]. A report illustrates a 38 year-old COVID-19 patient presenting with fever, dyspnea, and severe myalgia, with high creatine kinase (>42,670 U/L) and LDH (4301 U/La) and was diagnosed as viral myositis [232]. Another two cases of adult COVID-19 patients with lower extremity pain and weakness with rhabdomyolysis with high creatine kinase and LDH were reported [233, 234]. First case developed rhabdomyolysis on the 9th day of admission [233] and 2nd case presented to the hospital with rhabdomyolysis [234]. An isolated case of post-infectious myelitis has been reported from Germany in a COVID-19 patient [235].

Three cases of generalized brainstem type of myoclonus were reported from Spain, with normal CSF study in one patient (others not done) and normal imaging findings. However, nasopharyngeal RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 was positive in only one patient. In all these patients, EEG was showing mild diffuse slowing without any epileptic activity [236]. Paresthesias [51] and cutaneous hyperaesthesia [237] were reported as a presentation in COVID-19 patients. A case of COVID-19 patient with oropharyngeal dysphagia followed by aspiration pneumonia, taste impairment, impaired pharyngolaryngeal sensation, and nasopharyngeal contractile dysfunction with absent gag reflex was reported from Japan [238]. Visual symptoms were also reported in a few studies. Mao L et al. [32] reported visual impairment in 1.4% of the COVID-19 patients. Cases of optic neuritis [49], isolated central retinal artery occlusion [239], non-arteritic type of posterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (PION) [240] as a COVID-19 manifestation were also reported. The summary of all the neurological manifestations reported in COVID-19 is given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of all the neurological manifestations of COVID-19

| Non-specific | CNS manifestations | Peripheral nervous system manifestations |

|---|---|---|

|

Myalgia Headache Dizziness Vertigo Lightheadedness |

Disturbances in consciousness Agitation Pathological wakefulness Encephalitis Encephalopathy Acute necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalopathy Post-hypoxic encephalopathy/hypoxic ischaemic brain injury Mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion (MERS) Rhombencephalitis/myelitis Seizure (focal, GTCS, NCSE, status epilepticus, febrile seizures) Acute cerebrovascular disease Ischaemic stroke/TIA Hemorrhagic stroke SAH (aneurysmal and non-aneurysmal) Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis Ataxia Dysexecutive syndrome Corticospinal tract signs Syncope Short term memory loss Movement disorders Neuropsychiatric symptoms PRES syndrome MS plaque exacerbation Clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) ADEM Post-infectious myelitis Generalized brainstem type of myoclonus CNS vasculitis |

Taste disturbances (ageusia, reduced taste, distorted taste) Smell disturbances (anosmia, phantosmia, parosmia) Vision impairment Nerve pain/neuralgia Skeletal muscle injury Rhabdomyolysis Myositis Occipital neuralgia Dysautonomia Extraocular muscle abnormalities Isolated unilateral facial palsy GBS (AIDP/AMAN/AMSAN) DP (facial diplegia) variant of GBS Miller Fisher syndrome Cranial neuropathy Oropharyngeal dysphagia Optic neuritis Posterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (non-arteritic) (PION) Central retinal artery occlusion Cutaneous hyperaesthesia Parasthesias |

Heterogeneity

The heterogeneity was high in most of the neurological manifestations studied except for hemorrhagic stroke (medium), cerebral venous thrombosis (low), seizure (low), and ataxia (low). The funnel plots were symmetric in hemorrhagic stroke, ataxia, seizures, cerebral venous thrombosis and myalgia, which is pointing towards no bias in the selection of publications that are included in the study. However, the funnel plots were asymmetric in other neurological manifestations studied, which pointed towards the heterogeneity in the studies undertaken or bias in the selection of publications included in the study.

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we assessed the neurological manifestations, risk factors, mortality, laboratory parameters, and imaging findings in those patients with neurological features. Involving 30,159 patients, our meta-analysis is the first and most comprehensive study about the neurological manifestations of COVID-19.

The most common neurological manifestations reported were smell and taste disturbances. Another interesting finding is the geographical variations in the frequency of smell and taste disturbances. High incidence of smell and taste disturbances were noted in studies from most of the European countries [54] while studies from Asian countries showed a lower incidence [32]. However, most of the studies which reported a higher incidence of smell and taste disturbances evaluated mainly olfactory and taste symptoms only and studied mild to moderate cases and excluded severe/ICU patients compared with studies with lower incidence. This bias might have caused under-reporting of smell and taste disturbances in severe/ICU patients or could also be because of decreased awareness of investigator about these symptoms at the beginning of the pandemic. Supporting our assumption, a study from Spain which evaluated 841 COVID-19 patients with neurological manifestations reported only 4.9% of cases of smell disturbances and 6.2% cases of taste disturbances [49]. Other possibilities for these variations are, the difference in affinity of SARS-CoV-2 to tissues between populations, a different strain of mutated virus circulating in Europe compared with Asian countries. However, more studies are required to confirm these assumptions. Interestingly a study by Wan Y et al. [241] predicted that binding affinity between 2019-nCoV and human ACE2 may be enhanced by a single N501T mutation. Also, ACE2 receptors are highly expressed by sustentacular cells of the olfactory epithelium. Olfactory and taste disorders were more common in younger patients [52, 140] most occurs in the early stages as initial manifestations of the disease and even as the only manifestation of COVID-19. Hence, olfactory and gustatory disorders can be the initial and early manifestations of COVID-19 and early identification of these symptoms might lead to early diagnosis and disease containment.

Non-specific neurological manifestations could be just systemic features of a viral infection. Similar to olfactory disturbances, the incidence of myalgia, headache, and dizziness also shows geographical variations with the highest incidence reported from Europe, the USA, and Chile. The incidence of non-specific symptoms was lower in children. We noticed that non-specific symptoms were higher among the studies conducted in health care workers. This may be due to increased knowledge and awareness of the symptoms and disease.

The most common type of acute CVD reported was an ischaemic stroke. Hemorrhagic stroke, deep cerebral venous thrombosis, SAH (both non-aneurysmal and aneurysmal), and TIA were also reported; however, with much lesser prevalence. Severe infection or ICU requirement, older age, cardiovascular risk factors, prior co-morbidities, and hypercoagulable lab parameters were found to be a risk factor for developing acute CVD [32, 33]. The apparent association of COVID-19 and stroke is likely due to the sharing of similar risk factors. The severity of COVID-19 has been proved to be directly related to the presence of co-morbidities like hypertension and DM. An earlier meta-analysis by Yang J et al. [242] comprising [46, 243] COVID-19 patients reported the prevalence of risk factors, hypertension in 21.1%, DM in 9.7%, and cardiovascular diseases in 8.4%. Also, hypercoagulable blood parameters as shown by Li Y et.al [33], can lead to ischaemic stroke and cerebral venous thrombosis. Nervous system involvement in SARS-CoV-2 infection can be due to direct invasion of neural tissues, inflammatory response, or immune dysregulation. The SARS-CoV-2 virus uses the ACE2 and TMPRSS2 for entry to the host cell and it is one of the main determinants of infectivity [241, 244]. Susceptibility to infection correlated with ACE2 expression in previous studies [245].

Very few retrospective studies showed meningoencephalitis as a presentation of COVID-19; however, there are multiple case reports from all over the world. The probable mechanism can again be direct invasion via the hematogenous route or retrograde pathway via peripheral nerve terminals. Two studies even showed higher levels of inflammatory cytokines in the CSF analysis of these patients [177, 181]. SARS-CoV-2 could trigger a seizure in predisposing patients through neurotropic mechanisms as explained earlier [188]. However, more evaluation is required in this field to find a temporal factor. All types of seizures were reported like febrile seizures, focal seizures, generalized tonic-clonic seizures, status epilepticus and myoclonic status epilepticus, NCSE and also brainstem type of myoclonus. Demyelinating disorders like ADEM, exacerbation of MS plaque, and the clinically isolated syndrome were all reported in COVID-19 patients.

Cases of GBS and its variants were also reported in COVID-19. Both post-infectious and pre-infectious pattern of GBS were reported. The most common type of GBS reported was AIDP. Other variants like AMAN, AMSAN, Miller Fisher syndrome, and facial diplegic variant were also reported. Patients presenting as GBS without any other typical symptoms of COVID-19 were also reported. Possible pathogenesis of GBS in COVID-19 includes immune dysregulation secondary to systemic hyper inflammation and cytokines produced as described by McGonagle et al. [246] and Quin et al. [247]. Hence, it is important to suspect and test for COVID-19 in those patients presenting with GBS and MFS. However, more studies are required to conclude that these cases were not just coincidental and COVID-19 itself is a trigger for GBS and MFS. GBS was also reported in other recent important viral infections like MERS-CoV [248] and Zika virus [243].

Change in laboratory parameters was also reported in COVID-19 patients with neurological manifestations like higher white cell and neutrophil counts, reduced lymphocyte and platelet counts, elevated CRP and D-dimer levels, and higher levels of creatine kinase, LDH, and myoglobin [12, 32, 33, 62].

High heterogeneity in our study could be because of differences in the selection of patients and ethnicity, the severity of the disease, co-morbidities, only a few studies evaluated neurological symptoms specifically, variation in the number of patients in different studies, or due to publication bias and differences in the methodology among the studies.

Comparison with previous systematic reviews

Earlier meta-analyses addressing general clinical features in COVID-19 were published. One such study showed myalgia in (28.5%; 95%CI 21.2–36.2), headache (14.0%; 95%CI 9.9–18.6), and dizziness (7.6%; 95%CI 0.0–23.5) [249]. Our results also found similar results for myalgia, headache, and dizziness, i.e. (19.3%; 95%CI 15.1–23.6), (14.7%; 95%CI 10.4–18.9), and (6.1%; 95%CI 3.1–9.2) respectively. Another similar meta-analysis also showed myalgia in (21.9%; 95%CI 17.7–26.4) and headache in (11.3%; 95%CI 8.9–14.0) [250]. One more study reported the prevalence of headache as (8.0%; 95%CI 5.7–10.2) [251]. However, no meta-analyses are published on the specific neurological manifestations till now.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of our study is that we did a comprehensive search in all the electronic databases. Study limitations include high heterogeneity in the estimation of the prevalence of some neurological manifestations, the inclusion of studies with very small sample size, and lack of meta-regression analysis. We excluded studies in languages other than English where translation was not possible. Most of the included studies were of moderate quality. More good- quality prospective cohort studies are required to establish that the neurological manifestations reported in the studies were not just coincidental.

Conclusions