Abstract

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an autoantibody-mediated skin blistering disease. Previous studies revealed that intravenous immunoglobulin is therapeutic in animal models of BP by saturating the IgG protective receptor FcRn, thereby accelerating degradation of pathogenic IgG. Sasaoka et al. demonstrate that the inhibitory effects of IVIG on BP are also associated with negative modulation of cytokine production by keratinocytes.

Bullous pemphigoid

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is the most common autoimmune blistering disease and is most prevalent in the elderly. BP is characterized by an inflammatory cell infiltrate, autoantibodies against the hemidesmosomal proteins BP180 and BP230 of basal keratinocytes and subepidermal blistering (Hammers and Stanley, 2016). BP180 is a transmembrane protein, while BP230 is an intracellular protein. Direct immunofluorescence staining reveals linear deposition of IgG and/or complement components (C3 and/or C5) at the dermal-epidermal junction. Various inflammatory mediators including cytokines/chemokines and proteolytic enzymes are present in lesional skin, blister fluids and/or blood of BP patients.

As a transmembrane protein, BP180 is easily accessible to autoantibodies and it has been demonstrated to be pathogenically relevant in animal models of BP. Passive transfer of rabbit anti-mouse BP180 IgG or anti-BP180 IgG autoantibodies from BP patients into wild-type mice or BP180 humanized mice (respectively), induces skin disease which recapitulates the key features of human BP. In these in vivo animal models, pathogenic anti-BP180 IgG binding to BP180 on basal keratinocytes triggers complement activation, mast cell degranulation, and infiltration and activation of neutrophils. Proteinases released by infiltrating neutrophils cleave BP180 and other hemidesmosome-associated proteins, causing subepidermal blistering (Liu et al., 1993, Liu et al., 2000). Anti-BP180 IgG also causes BP180 depletion in hemidesmosomes, resulting in blister formation without complement activation. In addition, BP autoantibodies stimulate cultured keratinocytes to secrete IL-6 and IL-8.

Intravenous immunoglobulin

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) comprises the pooled fraction of serum IgG from thousands of healthy blood donors. IVIG consists mainly of IgG1 and IgG2. Although IgG is the dominant fraction, IVIG also contains other Ig isotypes such as IgA or IgM. IVIG has been used to treat many inflammatory and autoimmune diseases including autoimmune blistering diseases such as pemphigus, bullous pemphigoid and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.

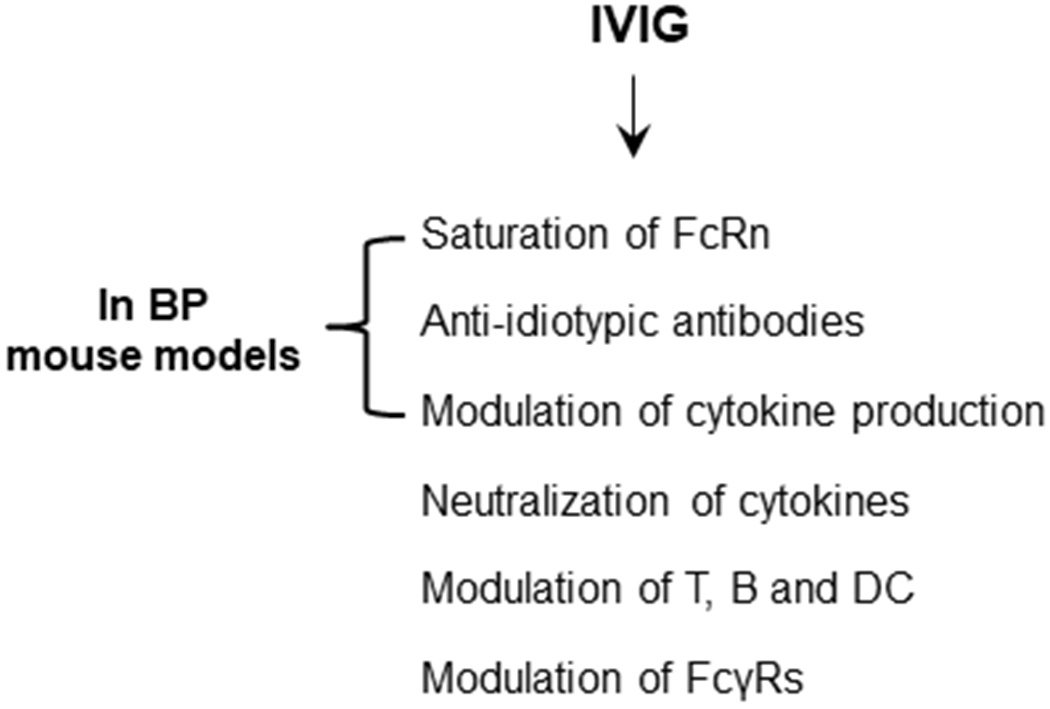

Numerous mechanisms have been proposed to explain the immunomodulatory effects of IVIG. For more comprehensive and in depth information on IVIG, please refer to these excellent reviews (Gelfand, 2012, Schwab and Nimmerjahn, 2013). Herein, we briefly summarize various modes of action of IVIG in IgG–mediated autoimmune diseases (Figure 1). These proposed modes of action include 1) saturation of the IgG protective neonatal FcR receptor (FcRn), 2) neutralization of autoantibodies by anti-idiotypic antibodies, 3) neutralization of cytokines or modulation of cytokine production, 4) attenuation of complement-mediated tissue damage, 5) modulation of functions of Fc receptors, and 6) modulation of effector functions of T, B and dendritic cells (Gelfand, 2012, Schwab and Nimmerjahn, 2013).

Figure 1. Proposed modes of action of IVIG in BP.

The mechanisms of IVIG as a therapeutic include the saturation of the IgG protective neonatal FcR receptor (FcRn); the neutralization of autoantibodies by anti-idiotypic antibodies;the neutralization cytokines or modulation of cytokine production; the attenuation of complement-mediated tissue damage; the modulation of functions and expression of the IgG receptors FcγRs; and the modulation of effector functions of T, B and dendritic cells. In mouse models of BP, IVIG are protective through the saturation of FcRn and anti-idiotypic antibodies to reduce circulating pathogenic IgG levels and by modulation of IL-6 and IL-10 production.

Intravenous immunoglobulin in bullous pemphigoid

The mainstream therapy for autoimmune skin diseases including bullous pemphigoid is high-dose systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressive drugs. However, long-term treatment with these drugs causes many side effects and even death, and some BP patients are unresponsive to these treatments. Many case reports and a recent randomized double-blind trial of IVIG for BP proved IVIG to be a safe and effective therapy for this disease (Amagai et al., 2017).

Li et al were the first to investigate the modes of action of IVIG in autoimmune cutaneous blistering disease using animal models of pemphigus and pemphigoid (Li et al., 2005) . Neonatal wild-type mice that are injected intraperitoneally with IgG autoantibodies from patients with pemphigus or rabbit anti-mouse BP180 IgG develop pemphigus- and BP-like skin blisters, respectively. However, mice lacking the IgG protective receptor FcRn become resistant to experimental pemphigus and pemphigoid associated with a substantial reduction in levels of pathogenic IgG antibodies in circulation. IVIG treatment of pathogenic IgG-injected wild-type mice mimics the FcRn-deficient mice injected with pathogenic IgG. IVIG treatment of FcRn-deficient mice does not cause further reduction of pathogenic IgG. These findings suggest that IVIG saturates FcRn, resulting in accelerated clearance of pathogenic IgG that prevents a sufficient level of pathogenic IgG from reaching its tissue targets to trigger skin blistering. Kamaguchi et al. also demonstrated that IVIG contains anti-idiotypic antibodies against BP IgG that prevent BP IgG-induced BP180 depletion in cultured keratinocytes and BP IgG-induced dermal-epidermal separation in the human skin cryosection model (Kamaguchi et al., 2017) . It remains to be determined if BP IgG-specific anti-idiotypic antibodies are inhibitory in vivo.

To further investigate the mechanisms of IVIG therapeutic activities in BP, the authors of this article (Sasaoka et al., 2018) used two BP mouse models, passive transfer of anti-BP180 IgG into neonatal BP180 humanized mice and adoptive transfer of human BP180-immunized spleen cells into adult immunodeficient BP180 humanized mice. In the former animal model, the authors pretreated neonatal mice with IVIG (400 mg/kg/day and 2000 mg/kg/day doses) followed by injection of polyclonal or monoclonal mouse anti-human BP80 IgG. IVIG at 2000 mg/kg/day dose significantly reduced circulating mouse anti-human BP180 IgG levels and disease severity. Similarly, IVIG at 2000 mg/kg/day dose also protected neonatal BP180 humanized mice from developing BP disease induced by BP IgG associated with significantly reduced circulating anti-BP180 IgG autoantibodies and reduced C3 deposition at the basement membrane zone. Although not directly tested, the reduction of pathogenic IgG in these models is likely through FcRn saturation by IVIG. These results confirm the findings by Li et al. and extend these findings to the IgG passive transfer models induced by mouse IgG against BP180 and BP IgG autoantibodies.

Neonatal mouse passive transfer is a quick and simple approach for testing proof-of-principle in a preventive setting, but is technically difficult to evaluate the efficacy of a drug (here IVIG) in a therapeutic setting. Therefore, the authors of this article employed their spleen cell adoptive transfer model of BP. In this model, wild-type mice are immunized by grafting human BP180 transgenic mouse skin. Immunized spleen cells are subsequently intravenously transferred into adult immunodeficient BP180 humanized mice. The recipient mice develop clinically significant skin lesions on day 14, and the disease scores peak 35 days post the adoptive transfer (Ujiie et al., 2010). The spleen cell adoptive transfer model was used to test the efficacy of IVIG in three treatment regimens; intravenous administration of IVIG from day 1 to day 21 daily, from day1 to day 5 daily, and from day 6 to day 10 daily post spleen cell adoptive transfer. Similar to results obtained in the IgG passive transfer models, all three IVIG treatments significantly reduced disease scores more than saline control mice at all time points examined from day 14 to day 35.

IVIG modulates production of cytokines/chemokines (Gelfand, 2012). IVIG down-regulates proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-6 and up-regulates the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. To determine if IVIG has the same activity in experimental BP, the authors first examined plasma cytokine/chemokine levels in both IgG passive transfer and spleen cell adoptive transfer models. IVIG treatment significantly reduced IL-6 levels in both IgG passive transfer and spleen cell adoptive transfer models of BP, and significantly increased IL-10 in the spleen cell adoptive transfer model. The authors then demonstrated that IVIG also significantly reduced the release of IL-6 by BP IgG-stimulated HaCaT cells, an immortalized human keratinocyte cell line. These in vitro and in vivo data suggest that IVIG can also act on keratinocytes and other local and/or immune cells to regulate production of IL-6 and IL-10 in BP. These findings are clinically relevant since IL-6 and IL-10 levels are associated with disease activity in BP (D’Auria et al., 1999, Inaoki and Takehara, 1998).

The work by Sasaoka et al. shows that, besides the increase of pathogenic IgG clearance by saturation of FcRn and the neutralization of pathogenic IgG by anti-idiotypic antibodies, IVIG may directly modulate keratinocyte and immune cell production of critical cytokines/chemokines in BP. Several important questions remain to be answered. For example, is FcRn required for IVIG activity in the spleen cell adoptive transfer model of BP? Does IVIG negatively regulate auto-reactive B cells as another mechanism underlying the reduced level of pathogenic anti-BP180 IgG in the spleen cell adoptive transfer model of BP? IVIG is an effective therapy for BP through multiple mechanisms. A better understanding of the modes of action of IVIG should improve the efficacy of IVIG, either as a mono-therapy or as a component of combined therapy.

One sentence highlight.

IVIG reduces disease severity in animal models of BP by directly modulating production of IL-6 and IL-10, in addition to reducing pathogenic antibody levels by increasing pathogenic IgG clearance by saturating FcRn as well as neutralizing pathogenic IgG by anti-idiotypic antibodies.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Amagai M, Ikeda S, Hashimoto T, Mizuashi M, Fujisawa A, Ihn H, et al. A randomized double-blind trial of intravenous immunoglobulin for bullous pemphigoid. J Dermatol Sci 2017;85(2):77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Auria L, Mussi A, Bonifati C, Mastroianni A, Giacalone B, Ameglio F. Increased serum IL-6, TNF-alpha and IL-10 levels in patients with bullous pemphigoid: relationships with disease activity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 1999;12(1):11–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand EW. Intravenous immune globulin in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. N Engl J Med 2012;367(21):2015–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammers CM, Stanley JR. Mechanisms of Disease: Pemphigus and Bullous Pemphigoid. Annu Rev Pathol 2016;11:175–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaoki M, Takehara K. Increased serum levels of interleukin (IL)-5, IL-6 and IL-8 in bullous pemphigoid. J Dermatol Sci 1998;16(2):152–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamaguchi M, Iwata H, Mori Y, Toyonaga E, Ujiie H, Kitagawa Y, et al. Anti-idiotypic Antibodies against BP-IgG Prevent Type XVII Collagen Depletion. Front Immunol 2017;8:1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Zhao M, Hilario-Vargas J, Prisayanh P, Warren S, Diaz LA, et al. Complete FcRn dependence for intravenous Ig therapy in autoimmune skin blistering diseases. J Clin Invest 2005;115(12):3440–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Diaz LA, Troy JL, Taylor AF, Emery DJ, Fairley JA, et al. A passive transfer model of the organ-specific autoimmune disease, bullous pemphigoid, using antibodies generated against the hemidesmosomal antigen, BP180. J Clin Invest 1993;92(5):2480–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Zhou X, Shapiro SD, Shipley JM, Twining SS, Diaz LA, et al. The serpin alpha1-proteinase inhibitor is a critical substrate for gelatinase B/MMP-9 in vivo. Cell 2000;102(5):647–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaoka T, Ujiie H, Nishie W, Iwata H, Ishikawa M, Higashino H, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin reduces pathogenic autoantibodies, serum IL-6 levels and disease severity in experimental bullous pemphigoid models. J Invest Dermatol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab I, Nimmerjahn F. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy: how does IgG modulate the immune system? Nat Rev Immunol 2013;13(3):176–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ujiie H, Shibaki A, Nishie W, Sawamura D, Wang G, Tateishi Y, et al. A novel active mouse model for bullous pemphigoid targeting humanized pathogenic antigen. J Immunol 2010;184(4):2166–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]