Abstract

Health inequities and disparities among various racial/ethnic minority, sexual minority, and rural populations are the focus of increasing national efforts. Three health problems disproportionately affecting these populations—HIV/AIDS, substance abuse, and trauma—deserve particular attention because of their harmful effects on health across the lifespan. To address these problems, our training program, the UCLA HIV/AIDS, Substance Abuse, and Trauma Training Program (HA-STTP), mentors and trains early career behavioral health scientists to conduct research using scientifically sound, culturally collaborative, and population-centered approaches. HA-STTP has been highly successful in training a diverse, productive, nationwide group of Scholars. The Program provides two years of training and mentorship to 20 (five/year over four years) Scholars. It is unique in its attention to traumatic stress as a form of dysregulation, particularly as experienced by underserved populations. Furthermore, our training program embraces a uniquely comprehensive, culturally grounded understanding of traumatic stress and its implications for substance abuse and HIV. HA-STTP advances Scholars’ knowledge of the interconnections among substance abuse, HIV/AIDS, traumatic stress, and health disparities, particularly in underrepresented populations; provides intensive mentorship to support Scholars’ research interests and career trajectories; capitalizes on a multidisciplinary, multiracial/ethnic network of expert faculty; and evaluates the Program’s impact on Scholars’ knowledge and productivity. By fostering the growth of Scholars committed to conducting research with underrepresented populations that are disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS, substance abuse, and traumatic stress, this Program enhances nationwide efforts to diminish the prevalence of these problems and improve health and quality of life.

Introduction

With the increasing diversity in the United States (U.S.) population, there continues to be a growing awareness of health inequities and disparities among various racial/ethnic minority, sexual minority, and rural populations in the United States. These groups have been historically underserved in the healthcare system and have worse health, including higher levels of tuberculosis, diabetes, asthma, HIV/AIDS, hypertension, stroke, and premature death (die before age 75 years) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2013) than other groups. Three health problems—HIV/AIDS, substance abuse, and trauma—deserve particular attention because of their deleterious effects on the health trajectories of people across the lifespan from early adolescence through late adulthood.

HIV/AIDS continues to be a serious epidemic among racial/ethnic minority and sexual minority populations even though the number of infections is declining (CDC, 2017). HIV/AIDS disproportionately impacts African Americans and Hispanic Americans. In 2015, African Americans accounted for 45% of HIV diagnoses, though they comprise 12% of the U.S. population (CDC, 2017). Hispanic Americans represented 18% of the American population and 25% of new HIV diagnoses (CDC, 2017).

In addition to health problems, many underserved populations experience traumatic stress. Traumatic stress is a response to exposure to excessive challenges and demands, and adverse experiences that exceed a person’s ability to cope (Spies et al., 2012). Traumatic stress can affect growth, reproduction, and immune activity (Yaribeygi, Panahi, Sahraei, Johnston, & Sahebkar, 2017). It has been well documented that traumatic stress can disrupt neurobiological mechanisms that can affect health outcomes, especially among racial/ethnic minority populations who have limited access to health care (Sherin & Nemeroff, 2011; Tyrka, Price, Marsit, Walters, & Carpenter, 2012). Both substance abuse and HIV are strongly correlated with stress, especially traumatic stress (Spies et al. 2012). For example, traumatic stress has been long associated with a pattern of individuals using substances to cope with the emotional and physical dysregulation that occurs while stressed (Brady, Back, & Coffey, 2004; Coffey et al., 2002; Drapkin et al., 2011; Simpson, Stappenbeck, Varra, Moore, & Kaysen, 2012). Traumatic stress experiences, such as sexual abuse, may heighten risks for health problems and increase risks for high-risk sexual practices that are linked to HIV/AIDS transmission (Radcliffe, Biedas, Hawkins, & Doty, 2011). Substance abuse, HIV/AIDS, and traumatic stress can also co-occur in racial/ethnic minority populations and other underserved populations such as poor populations (Pellowski, Kalichman, Matthews, & Adler, 2013). For example, Soller and colleagues (2001) found that 56% of HIV/AIDS infected individuals with low income also had post traumatic symptoms.

One strategy to help develop more interventions and treatment for the confluence of traumatic stress, HIV/AIDS, and substance abuse among underserved populations is to increase the number of behavioral scientists who conduct research on interventions and treatment for disproportionately impacted populations. Mentoring and training on how to do this research using scientifically sound, culturally collaborative, and population-centered approaches is sorely needed. This article describes a training program funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) — the UCLA HIV/AIDS, Substance Abuse, and Trauma Training Program (HA-STTP) — that provides this type of mentoring and training for early career postdoctoral scholars whose focus is reducing substance abuse and transmission of HIV in underserved populations at high risk for traumatic stress and health disparities. Scholars who are accepted into HA-STTP hold funded fellowships or other academic or clinical positions but are seeking specific training in HIV/AIDS, substance abuse, traumatic stress, and health disparities. Our innovative training approach highlights conceptualizing, designing, conducting, and disseminating culturally humble and congruent research focused on the confluence of these synergistic issues. Culturally humble and congruent research is characterized by the integration of culturally specific knowledge in each component of the research (Hook, Davis, Owen, Worthington, & Utsey, 2013; Trevelon & Murray-Garcia, 1998; Wyatt, Williams, Gupta, & Malabranche, 2012). Such research is critical to the improvement of health and healthcare utilization among underserved populations, including racial/ethnic minority populations that are disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS.

Existing Health Disparities Training Programs

Mentoring and training programs for underrepresented faculty are scarce, as noted in a systematic review (Beech et al., 2013). Only a few training programs have a focus similar to ours on substance abuse, trauma, and/or HIV (e.g., Viets et al., 2009; Yager, Waitzkin, Parker, & Duran, 2007). For example, the Public Health Solution’s Behavioral Sciences Training in Drug Abuse Research (BST) training program prepares social scientists for careers in research on drug abuse and HIV/AIDS through intensive training (Falkin, 2015). Trainees participate in seminars, workshops and research on NIDA grants. Their program comprises 16 fellows (nine pre-doctoral trainees and seven postdoctoral trainees) from the various behavioral disciplines and includes both qualitative and quantitative researchers working in a mutually supportive milieu to conduct research, build their publication records, and write grant applications for outside funding. Fellows specialize in a wide range of topics. The BST program is a collaborative effort of Public Health Solutions (the grantee), National Development and Research Institutes, Inc. (the training site), NIDA’s Center for Drug Use and HIV Research (at New York University studies), and Columbia University.

The University of Vermont also has a post-doctoral training program integrated within the Vermont Center on Behavior and Health that focuses on the behavioral economics and behavioral pharmacology of addiction, with a special focus on vulnerable populations and health disparities (Vermont Center on Behavior and Health, 2018). Trainees are typically experimental and clinical psychologists who receive individual mentoring by NIH-supported scientists, seminars and courses in substance abuse and related fields of behavioral economics and behavioral pharmacology, and training in writing grant applications and career development. Trainees have opportunities to gain research experience with a wide range of NIH-supported behavioral, neurobiological, and pharmacological human laboratory and treatment outcome studies.

Significance and Innovation of the UCLA HA-STTP

The programs noted above reflect growing national attention to substance abuse and HIV/AIDS research (Liu et al., 2006; Myers et al., 2009) and training. Our training program embraces a uniquely comprehensive, culturally grounded understanding of traumatic stress and its implications for substance abuse and HIV. Far too often, investigators do not distinguish between trauma-related events that occur earlier and later in life and their effects on substance abuse, HIV-related risk behaviors, and mental health. Many studies also do not assess the severity and specificity of abuse and trauma experiences that might be associated with certain types of behaviors (substance abuse, sexual risk) and their consequences (Loeb, Gaines, Wyatt, Zhang, & Liu, 2011). We contend that research training and mentoring for postdoctoral trainees should include more sophisticated conceptual models and strategies for designing research that addresses the intersection of substance use, HIV, and traumatic stress in high-risk underserved communities. HA-STTP provides a two-year course of intensive mentorship and training to postdoctoral and early career Scholars who hold funded fellowships or other academic positions but need specific training in HIV/AIDS, substance abuse, traumatic stress, and health disparities. HA-STTP seeks to further Scholars’ understanding of these interrelated phenomena (Gonzalez-Guardo, McCabe, LeBlanc, De Santos, & Provencio-Vasquez, 2016; Meyer, Springer, & Altice, 2011; Tsuyuki et al., 2017), and their implications for health disparities, including disparities in healthcare access, utilization, and clinical outcomes. HA-STTP is also designed to expand the breadth of Scholars’ methodological skills.

HA-STTP is innovative in several ways. First, this Program focuses on the interactive constellation of substance abuse, HIV, traumatic stress, and related health disparities. This is one of few training programs that highlights the cluster of these problems that are common to underserved populations and yet overlooked in research and care. Second, the Program trains investigators to be culturally humble and competent and encourages research and interventions that are culturally congruent. This approach addresses a significant gap in existing substance abuse and HIV research and training (Wyatt et al., 2012). In the first iteration of our Program, we successfully developed and mentored a pool of emerging clinician researchers that are able both to discern the trauma-related contextual and socio-cultural significance of challenging behaviors such as substance abuse and sexual risk-taking, and to develop nuanced, culturally relevant interventions that address these behaviors.

Third, in order to address disparities among those trained to conduct research on historically underserved populations at greatest risk for HIV/AIDS, this Program adapts an approach that is culturally relevant and aware of the long-established disparities in health care and treatment among health professionals that has discouraged health utilization, even when services were offered. The Program specializes in research skills and career mentoring that are not usually offered in postdoctoral training (e.g., T32) or to emerging faculty in academic settings, but are critical to research with underserved populations at risk for HIV/AIDS. The adapted model for training (Manson, 2009) assesses personal aspirations and institutional factors that have largely been overlooked in past training (Wyatt, Williams, & Henderson, & Summer, 2009). Our Program highlights those issues and assists Scholars in developing skills that can ensure their continued success, despite potential institutional barriers that have contributed to disproportionately low numbers of racial/ethnic minority investigators who have achieved success in obtaining grant funding and attaining sustainable academic careers. We have developed short- and long-term training goals for each Scholar to acquire the needed skills, and we utilize a flexible model that recognizes unique life circumstances they may face. Our program is designed for Scholars who have full-time clinical research or postdoctoral positions but wish to receive additional specialized research training and mentoring in the Program’s core foci. The flexible training model used in our Program allows Scholars to satisfy the requirements of their full-time positions and obtain the additional training and mentoring provided by the Program at the same time. We learned from our Scholars that, for some, this flexibility was key to being able to remain in the program despite personal and professional challenges such as family emergencies and job-related relocation.

Fourth, our Program focuses on the importance of being both humble and knowledgeable about and considering the needs and health-related constraints of the communities where research will be conducted. The involvement of community partners is essential when determining culturally congruent approaches that attend to the realities of those who provide and those who receive services. The Program team’s collective experience in working with community partners serves as a model for the Scholars, who learn how to practice humility, establish relationships, address diversity within communities, and collaborate effectively within a culturally relevant framework.

Fifth, the Principal Investigators for the Program are UCLA faculty members who themselves are racial/ethnic minority investigators and therefore have the lived experience of conducting research with underserved populations in national and international settings; and other team members include UCLA faculty members who are not racial/ethnic minority investigators but have strong research agendas that focus on these populations. The team’s collective experience provides the Program with the conceptual frameworks, methods, and strategies that capture the real-life existence of underserved populations that are often not included in many HIV/AIDS studies. The faculty has also been successful in obtaining decades of extramural funding for their research, and they have track records of success mentoring junior clinician researchers and other emerging investigators. In addition to the core UCLA faculty, the Program has assembled a network of distinguished experts, many of whom are from racial/ethnic minority populations themselves and all of whom conduct research on underserved populations. These experts serve as mentors and attend the Institutes when invited, to provide didactic learning to Scholars on the topics identified as core components of the Program curriculum. Given that there continue to be disparities in the number of NIH-funded grants awarded to investigators of color, especially those who are African American (Feagin & Bennefield, 2014; Ginther et al., 2011) our Program Scholars have the opportunity to interface with experts who have received funding and who can assist them not only in their research but in their plans for careers that may have additional pressures of being underrepresented in the academic world. Our experts’ approaches are well-tested and highly successful because the content is unique, i.e., it is based on the experience and research of Scholars who have conducted research on underserved groups for decades.

Finally, our Program Scholars learn how to mentor others by using the models presented and applying what they have learned in their careers and in their research. The Program considers graduating Scholars as colleagues, adding them to the network of mentors who can ensure the success of others to come. At several Institutes over the past five years, prior Scholars have attended to provide mock grant application reviews and to share their experiences of applying for and receiving NIH funding, and some Scholars have published together (Kipp et al., 2017). At the end of the first cycle of funding, most Scholars were able to attend the culminating Institute, which strengthened collaborations across cohorts and faculty.

Description of HA-STTP

Scholars who are accepted into this program hold funded fellowships or other academic or clinical positions but seek specific training in HIV/AIDS, substance abuse, traumatic stress, and health disparities. The program is designed to advance early career postdoctoral Scholars knowledge of the ways in which substance abuse, HIV/AIDS, traumatic stress, and health disparities are interconnected in underrepresented populations; provide focused, intensive mentorship to support Scholars’ research interests and career trajectories in the key areas addressed by this Program; capitalize on a local and national multidisciplinary, multiethnic network of expert faculty who are committed to fostering the intellectual and professional growth of the Scholars; and evaluate the impact of the Program on Scholars’ knowledge and productivity.

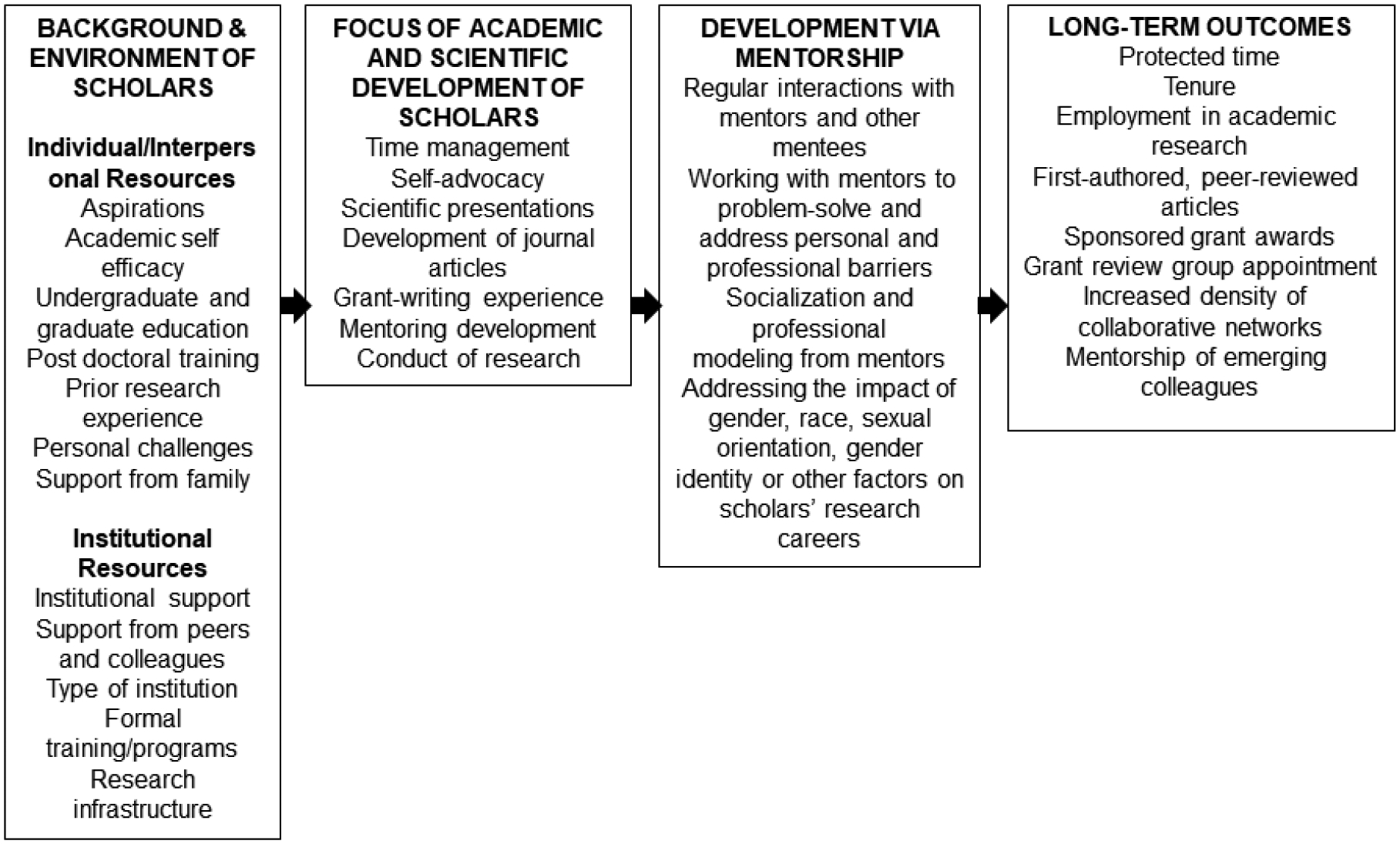

This training program represents an evolution of our multidisciplinary, multiethnic team’s National Institute of Mental Health American Recovery and Reinvestment Act – funded HIV/AIDS Translational Training Program, which was successful in providing two continuous years of training and mentorship to five postdoctoral scholars, several of whom have received or are now seeking NIDA funding. To guide the process of training and mentoring the scholars, we adapted Tinto’s model of academic persistence (1975) and Manson’s modifications (2009) to develop a conceptual model and process that focuses on the factors that contribute to achieving academic success for individuals who have attained professional or doctoral degrees, but do not have careers or specialized training in HIV research. A number of factors contribute to the development of a successful research career for the Program’s Scholars, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Adapted conceptual model of factors that influence the development of research scholars.

Background and Environment factors include Individual/Interpersonal Resources such as aspirations to attain an academic career and to conduct research, academic self-efficacy, prior education and research experience, postdoctoral training, personal challenges, and support from family are core elements for success in the Program. Institutional Resources influence Background and Environment factors, and include institutional support as well as support from peers and colleagues, type of institution, formal training/programs, and the research infrastructure available at the Scholars’ home institutions. Candidates for the Program are screened and selected based upon their academic preparation, their career aspirations and goals, how they have handled obstacles and challenges to achieving their career goals, and their motivation and discipline. Background and Environment factors inform our focus on the Academic and Scientific Development of scholars, including time management, self-advocacy, scientific presentations, development of journal articles, grant-writing experience, mentoring development, and conduct of research. The Program team works to ensure that Program Scholars make progress toward meeting these professional needs, with personalized mentoring, training workshops, and close research supervision. Scholar Development via Mentorship includes regular interactions with mentors and scholars’ peers, working with mentors consistently to problem-solve and address personal and professional barriers, and socialization and professional modeling from mentors. Program Scholars will also learn to identify and address when gender, race, sexual orientation, gender identity or other factors impact their research careers. Long-term outcomes include maintaining protected time to ensure their productivity, achieving academic advancement including tenure, employment in academic research, first-authored publications, sponsored grant awards, grant review group appointments (e.g., NIH study sections) increased density of collaborative networks, and mentorship of emerging colleagues.

Program Curriculum

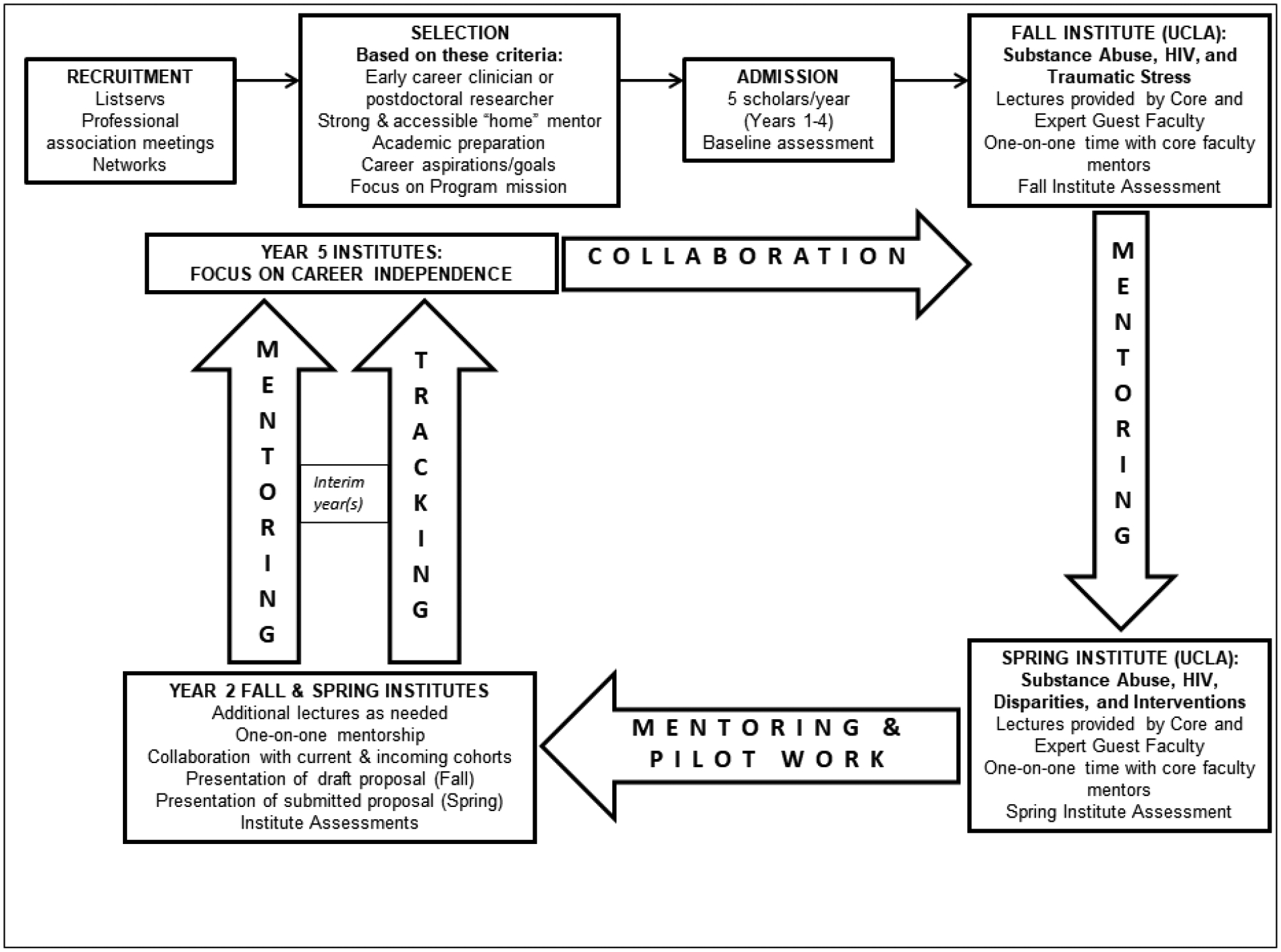

As can be seen in Figure 2, HA-STTP entails: (1) Completion of a baseline needs assessment: After acceptance, Scholars complete a needs assessment before the formal program and Institutes begin. Their goals and areas of research help the Steering Committee (SC), consisting of UCLA core faculty, to guide the didactic, skill-based information that are offered during the Institutes; (2) The Institutes: An intense, academic program with seminars and didactic instruction, which last one week, two times per year (i.e., Fall and Spring Institutes); (3) Individual Mentorship: All Scholars will receive mentorship from at least one SC member assigned to them based on common research areas or training needs and from an accessible “Home” mentor, who may or may not be geographically proximal, but engages in ongoing dialogue about research interests and challenges. (4) Ongoing research mentoring with short- and long-term assessments for five years via emails, conference calls, and remote team communication (e.g., Skype and Zoom) to guide and monitor progress on publications, the preparation and submission of a federal grant application, and completing their pilot study. (5) Expanding the established multi-disciplinary network of Scholars and faculty who are committed to ongoing collaboration around the Program’s mission.

Figure 2.

Program overview.

Scholars attend two week-long Institutes per year for two years and receive continual, personalized career mentoring, training, and research supervision. Each cohort of Scholars is followed for the duration of the training grant, and all cohorts come together in the final year (Year 5) to share their experiences and successes. Scholars develop the necessary skills to pursue a productive program of research in areas related to substance use, HIV/AIDS, traumatic stress, and health disparities. They are supported in the development of competitive grant applications, including receiving a modest amount of funds to prepare preliminary studies data. Each Scholar is expected to submit a grant proposal and to conduct a pilot study within the two-year tenure of the Program.

The educational curriculum also provides a thematic approach to training the Scholars in the conduct of culturally humble and congruent research among underserved populations. The curriculum is designed to: 1) address issues of health disparities (e.g., misdiagnosis, late or no access to treatment, greater risk for HIV/AIDS due to substance use practices, sexual practices, etc.); 2) prepare Scholars for emerging perspectives on health disparities research that encompass sound and appropriate methodologies for the more rapid development, implementation, and dissemination of intervention research (Abrams, 2006); and 3) help Scholars initiate a program of research (e.g., publications, etc.) including qualitative and mixed methods studies and randomized clinical trials. In addition to the core information, Scholars will receive reviews of their grant applications and pilot work, as well as individualized tutorials with mentors on study design and the preparation of grant applications, including resubmissions.

Each year, discussions with Scholars and their mentors address and lay the foundation for the use of a one-time $10,000 grant for pilot research that will produce preliminary findings for the Scholars’ eventual grant proposals. The total amount spent on all 20 scholars in five years is $534,698, which averages to $26,735 per scholar. This includes the grant for their pilot research, equipment, supplies, software and software renewal, travel and lodging to conferences and institutes, and conference fees.

As noted above, HA-STTP is unique in that it conducts needs assessment of mentees and explores the life experiences and demographics of the mentees that influence him/her and his/her research. Second, it incorporates traumatic stress, particularly as experienced by underserved populations. Underserved populations, particularly racial/ethnic minority populations, are disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS and typically experience a high degree of traumatic stress, defined here as reactions to challenges, demands, threats, or changes that exceed coping resources. It is well-established that substance abuse and HIV/AIDS are highly correlated, and that substance abuse and traumatic stress are highly correlated (Brief et al., 2004). The training Program seeks to further Scholars’ understanding of the interrelationships among these phenomena, and their implications for health disparities, including disparities in healthcare access, utilization, and clinical outcomes. Third, our innovative approach highlights conceptualizing, designing, conducting, and disseminating culturally humble and congruent research focused on the confluence of these synergistic issues. Culturally humble and congruent research is characterized by the integration of culturally specific knowledge into each component of the research (Mio et al., 1999 Wyatt et al., 2011). Such research is critical to the improvement of health and healthcare utilization among underserved populations, including racial/ethnic minority populations that are disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS.

Program Evaluation

The evaluation of HA-STTP is multi-tiered. First, each Scholar completes an evaluation assessment immediately following each Institute. This approach ensures that we will be able to correctly ascertain the Scholars’ needs, identify and address obstacles and challenges that are interfering with the Scholar’s progress in achieving their goals, and identify changes in the program experiences that are needed to ensure that the Scholars achieves her/his goals. The second tier is systematic assessments. Members of the SC compile and review all of the Scholars’ evaluations of HA-STTP twice each year (after each Institute) and three outside evaluators who are familiar with training programs conduct an annual review of the Program. These evaluations allow for timely adjustment and prevent any negative situations from escalating (e.g., need for specific seminar content, need for additional resources or to re-allocate resources, etc.). The third tier is microsystem assessments. The SC and Home Mentors evaluate the Scholars (i.e., the extent to which they consult regularly with their mentors, make progress in completing and submitting their pilot grant applications, as well as access and utilize program resources, etc.); and Scholars and Mentors evaluate each other and HA-STTP, including didactic seminars and guest speakers (evaluations will after each Institute). The final tier is individual assessments. The Scholars document their progress toward developing a program of research, publishing and presenting their research findings, obtaining extramural research funding, and developing collaborations with other investigators conducting studies in HIV/AIDS, substance abuse, mental health, and associated health disparities. The extent to which Scholars are able to identify challenges and/or barriers to their success and develop the skills and resilience necessary to build productive academic/research careers is also assessed. This measure is designed to be consistent with the conceptual model; information is collected by interviews and from the Scholars’ CVs. The short-term assessment is administered by the Primary Mentor at the end of Year 1 and Year 2 to assess growth and change over time, and the long-term assessment is administered five years after entry into the Program.

Successes and Lessons Learned

Our recruitment strategies were successful each year in both attracting a substantial applicant pool, as well as attracting an applicant pool with strong representation of individuals from racial/ethnic minority groups (72% of Scholars and Affiliates). We had such strong applicants that we made the decision to accept both Scholars and Affiliates each year, with the latter group being comprised of individuals in the Los Angeles area who would not require travel funds. Affiliates were offered attendance at one year of Institutes and mentoring; they did not receive pilot funds. We will continue to try to accept Affiliates if the applicant pool warrants it (i.e., many meritorious local applicants) and our requested funding permits it (i.e., no additional costs for Affiliates).

Our Scholars and Affiliates came to the Program with backgrounds in medicine, psychology, medical and psychological anthropology, and public health. All 18 HA-STTP Scholars have academic appointments at the Assistant or Associate level. Ten Scholars attended all four Institutes (a key Program outcome); two attended three of four Institutes; and our current cohort of Scholars as well as three Scholars from prior cohorts attended Institutes in the Fall of 2017 and Spring of 2018 in order to complete their two-year tenure. In addition, three Scholars returned for a fifth Institute to provide peer mentoring and mock reviews. All Scholars were invited to the final Institute in Spring 2018. The Institutes have been highly rated, with Scholars consistently indicating high satisfaction (an average of 4.5 on a scale from 1-extremely unsatisfied to 5-extremely satisfied) with the lectures, mentoring opportunities, and Institute logistics.

Thirteen Scholars (72%) submitted grant proposals during their two-year HA-STTP tenure, which was one of our key Program outcomes. In total, HA-STTP Scholars and Affiliates produced 38 publications that acknowledged the Program funding, in journals such as BMC Public Health, Substance Use & Misuse, Journal of Behavioral Health & Health Services Research, International Journal of Drug Policy, PLoS One, Drug and Alcohol Review, Child Abuse & Neglect, BMJ Open, AIDS & Behavior, Annals of Epidemiology, Social Science & Medicine, American Journal on Addictions, Lancet, and Archives of Sexual Behavior. Twenty-nine (76%) of these publications were first-authored by HA-STTP Scholars and Affiliates; HA-STTP mentors served as co-authors on several of these papers. Their papers address a wide range of topics directly relevant to HA-STTP goals, including substance abuse and HIV in marginalized populations (e.g., Cheney, Booth, Borders, & Curran, 2016; Gideonse, 2015a; Gideonse, 2016; MacCarthy et al., 2015; Rivera-Díaz et al., 2015), substance abuse and HIV care (e.g., Kipp et al., 2017; MacCarthy et al., 2015), health disparities and vulnerable populations (e.g., MacCarthy, Reisner, Nunn, Perez-Brumer, & Operario, 2015), culturally congruent interventions (e.g., Dickerson et al., 2017), HIV risk behaviors (e.g., Brinkley-Rubinstein et al., 2016; Gideonse, 2015b; Irvin et al., 2015; Ritchwood, DeCoster, Metzger, Bolland, & Danielson, 2016), culture and trauma (e.g., Jeremiah, Quinn, & Alexis, 2017), social determinants and substance abuse (e.g., Linton et al., 2016; Linton, Haley, Hunter-Jones, Ross, & Cooper, 2017), psychiatric comorbidities (e.g., Moghaddam, Campos, Myo, Reid, & Fong, 2015; Moghaddam, Yoon, Dickerson, Kim, & Westermeyer, 2015), barriers to HIV care (e.g., Varas-Diaz et al., 2017), HIV, trauma, and substance abuse in international settings (e.g., Gouse et al., 2016; Watt et al., 2016a; Watt et al., 2016b; Watt, Guidera, Hobkirk, Skinner, & Meade, 2017; Watt, Kimani, Skinner, & Meade, 2017; Watt, Myers, Towe, & Meade, 2015), addiction research training (e.g., Estreet, 2017; Estreet, Archibald, Tirmazi, Goodman, & Cudjoe, 2017), and innovative translational methods (e.g., Cheney et al., 2016; Irvin et al., 2016; Pearson et al., 2017; Smiley et al., 2017).

We learned from early evaluations that Scholars wanted more individual time with their SC mentors while at UCLA. Subsequently, we adjusted the Institute agendas to include at least one hour of one-on-one, in-person mentoring time at each Institute; this adjustment was met with much appreciation. We also learned that Scholars wanted to learn more about the SC mentors’ career paths, obstacles, successes, lessons learned; thus, we began sharing our respective stories at a dinner during the Spring Institute each year. This helped to foster more personal connections amongst the Scholars and mentors, a hallmark of successful mentoring (Straus, Johnson, Marquez, & Feldman, 2016). As one Scholar noted in an evaluation, “I so appreciated the mentors providing us with the stories of their pathways into a funded research career. It really helped me to appreciate that paths are not always linear, and that perseverance and passion are the foundation of success.” The grant application-writing presentation at each Spring Institute was a highlight, with Scholars consistently noting the value of having an NIH Program Officer share knowledge and perspective on appropriate NIH grant mechanisms, cutting-edge topics, and successful approaches to research career development. Our inaugural cohort expressed interest in more guidance about preparing career development awards (e.g., K01s); thus at subsequent Institutes we had SC members, expert guest faculty, and HA-STTP Scholars discuss their experiences of applying for and receiving these awards.

Conclusion

Clearly, there is a great public health need for more behavioral health scientists who can conduct research to address the health needs of people of color, and an even greater public health need for a more diverse pool of behavioral health scientists who can conduct this research. HA-STTP is one effort that is attempting to address this gap. The Program contributes to national efforts to reduce the numbers of racial/ethnic minority populations who are affected by HIV/AIDS, substance abuse and traumatic stress, and improve health and quality of life by fostering the growth of Scholars who are committed to conducting research with these underrepresented populations.

Public Policy Relevance.

Health inequities and disparities among various racial/ethnic minority, sexual minority, and rural populations are the focus of increasing national efforts. Three health problems disproportionately affecting these populations—HIV/AIDS, substance abuse, and trauma—deserve particular attention because of their harmful effects on health across the lifespan. To address these problems, our training program mentors early career behavioral health scientists to conduct research using scientifically sound, culturally collaborative, and population-centered approaches.

Acknowledgments

The work described in this manuscript is supported by an award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R25 DA035692).

Contributor Information

Norweeta G. Milburn, University of California, Los Angeles

Alison B. Hamilton, University of California, Los Angeles

Susana Lopez, University of California, Los Angeles

Gail E. Wyatt, University of California, Los Angeles

References

- Abrams DB (2006). Applying transdisciplinary research strategies to understanding and eliminating health disparities. Health Education & Behavior, 33(4), 515–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech BM, Calles-Escandon J, Hairston KG, Langdon MSE, Latham-Sadler BA, & Bell RA (2013). Mentoring programs for underrepresented minority faculty in academic medical centers: a systematic review of the literature. Academic medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 88(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady K, Back S, & Coffey S (2004). Substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(5), 206–209. [Google Scholar]

- Brief DJ, Bollinger AR, Vielhauer MJ, Berger-Greenstein JA, Morgan EE, Brady SM, Buondonno LM, & Keane TM (2004). Understanding the interface of HIV, trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance use and its implications for health outcomes. AIDS Care, 16(Suppl1), S97–S120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Parker S, Gjelsvik A, Mena L, Chan P, Harvey J, … Nunn A (2016). Condom use and incarceration among STI clinic attendees in the Deep South. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3590-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2016; vol. 28 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published November 2017. Accessed May 26, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control Fact Sheet 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics/overview/cdc-hiv-us-ataglance.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2018.

- Cheney AM, Abraham TH, Sullivan S, Russell S, Swaim D, Waliski A, & Hunt J (2016). Using community advisory boards to build partnerships and develop peer-led services for rural student veterans. Progress in Community Health Partnership: Research, Education, and Action, 10(3), 355–364. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2016.0042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheney A, Booth B, Borders T, & Curran G (2016). The role of social capital in African Americans’ attempts to reduce and quit cocaine use. Substance Use and Misuse, 51(6), 777–787. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2016.1155606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey SF, Saladin ME, Drobes DJ, Brady KT, Dansky BS, & Kilpatrick DG (2002). Trauma and substance cue reactivity in individuals with comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and cocaine or alcohol dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 65(2), 115–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson D, Moore LA, Rieckmann T, Croy CD, Venner K, Moghaddam J, Gueco R, & Novins DK (2017). Correlates of motivational interviewing use among substance use treatment programs serving American Indians/Alaska Natives. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, 45(1), 1–15. doi: 10.1007/s11414-016-9549-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drapkin ML, Yusko D, Yasinski C, Oslin D, Hembree EA, & Foa EA (2011). Baseline functioning among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 41(2), 186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estreet AT (2017). Integrating substance use disorder education at an urban Historically Black College and University: Development of a Social Work Addiction Training Curriculum. Urban Social Work, 1(1), 65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Estreet A, Archibald P, Tirmazi M, Goodman S, & Cudjoe T (2017). Exploring social work student education: The effect of a harm reduction curriculum on student knowledge and attitudes regarding opioid use disorders. Substance Abuse, 38(4), 369–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkin GP (2015). Behavioral Sciences Training in Drug Abuse Research. National Institute of Health. Public Health Solutions. Retrieved from http://grantome.com/grant/NIH/T32DA007233-31#panel-abstract [Google Scholar]

- Feagin J, & Bennefield Z (2014). Systemic racism and U.S. health care. Social Science and Medicine, 103, 7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Guarda RM, McCabe BE, Leblanc N, De Santis JP, Provencio-Vasquez E (2016). The contribution of stress, cultural factors, and sexual identity on the substance abuse, violence, HIV, and depression syndemic among Hispanic men. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22(4):563–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gideonse T (2015a). Pride, shame, and the trouble with trying to be normal. Ethos, 43(4), 332–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gideonse T (2015b). Survival tactics and strategies of methamphetamine-using HIV-positive men who have sex with men in San Diego. PLoS One, 10(9), E0139239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gideonse T (2016). Framing Samuel See: The discursive detritus of the moral panic over the “double epidemic” of methamphetamines and HIV among gay men. The International Journal of Drug Policy, 28, 98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginther D, Schaffer W, Schnell J, Masimore B, Liu F, Haak L, & Kington R (2011). Race, ethnicity, and NIH research awards. Science (Washington), 333(6045), 1015–1019. doi: 10.1126/science.1196783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouse H, Joska J, Lion R, Watt M, Burnhams W, Carrico A, & Meade C (2016). HIV testing and sero‐prevalence among methamphetamine users seeking substance abuse treatment in Cape Town. Drug and Alcohol Review, 35(5), 580–583. doi: 10.1111/dar.12371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook JN, Davis DE, Owen J, Worthington EL Jr, & Utsey SO (2013). Cultural humility: Measuring openness to culturally diverse clients. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(3), 353–366. doi: 10.1037/a0032595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvin R, McAdams-Mahmoud A, Hickman D, Wilson J, Fenwick W, Chen I, Irvin N, Falade-Nwulia O, Sulkowski M, Chaisson R, Thomas DL, Mehta SH (2016). Building a Community - Academic Partnership to Enhance Hepatitis C Virus Screening. Journal of Community Medicine Health Education 6(3). pii: 431. Epub 2016 May 30. doi: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000431J [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvin R, Vallabhaneni S, Scott H, Williams JK, Wilton L, Li X, Buchbinder S; HPTN 061. (2015). Examining levels of risk behaviors among black men who have sex with Men (MSM) and the association with HIV acquisition. PLoS One, 10(2):e0118281. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeremiah R, Quinn C, & Alexis J (2017). Exposing the culture of silence: Inhibiting factors in the prevention, treatment, and mitigation of sexual abuse in the Eastern Caribbean. Child Abuse and Neglect, 66, 53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipp A, Rebeiro M, Shepherd P, Brinkley-Rubinstein F, Turner B, Bebawy E, … Hulgan M (2017). Daily marijuana use is associated with missed clinic appointments among HIV-infected persons engaged in HIV care. AIDS and Behavior, 21(7), 1996–2004. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1716-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton SL, Cooper HL, Kelley ME, Karnes CC, Ross Z, Wolfe ME, … Paz-Bailey G (2016). Associations of place characteristics with HIV and HCV risk behaviors among racial/ethnic groups of people who inject drugs in the United States. Annals of Epidemiology, 26(9), 619–630.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton S, Haley D, Hunter-Jones J, Ross Z, & Cooper H (2017). Social causation and neighborhood selection underlie associations of neighborhood factors with illicit drug-using social networks and illicit drug use among adults relocated from public housing. Social Science and Medicine, 185, 81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Longshore D, Williams JK, Rivkin I, Loeb T, Warda US, … & Wyatt G (2006). Substance abuse and medication adherence among HIV-positive women with histories of child sexual abuse. AIDS and Behavior, 10(3), 279–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb TB, Gaines T, Wyatt GE, Zhang M, & Liu H (2011). Associations between child sexual abuse and negative sexual experiences and revictimization among women: Does measuring severity matter? Child Abuse and Neglect, 35(11), 946–955. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCarthy S, Mena L, Chan PA, Rose J, Simmons D, Riggins R, … Nunn A (2015). Sexual network profiles and risk factors for STIs among African-American sexual minorities in Mississippi: A cross-sectional analysis. LGBT Health, 2(3), 276–281. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCarthy S, Hoffmann M, Ferguson L, Nunn A, Irvin R, Bangsberg D, Gruskin S, Dourado I (2015). The HIV care cascade: Models, measures and moving forward. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 18(1), 19395. doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.1.19395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCarthy S, Reisner SL, Nunn A, Perez-Brumer A, & Operario D (2015). The time is now: Attention increases to transgender health in the United States but scientific knowledge gaps remain. LGBT Health, 2(4), 287–291. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson SM (2009). Personal journeys, professional paths: Persistence in navigating the crossroads of a research career. American Journal of Public Health, 99(S1): S20–S25. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.133603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JP, Springer SA, Altice FL (2011). Substance abuse, violence, and HIV in women: A literature review of the syndemic. Journal of Women’s Health, 20(7):991–1006. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mio JS (Ed.). (1999). Key Words in Multicultural Interventions: A Dictionary. Greenwood Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam J, Campos F, Myo M, Reid D, & Fong C (2015). A longitudinal examination of depression among gambling inpatients. Journal of Gambling Studies, 31(4), 1245–1255. doi: 10.1007/s10899-014-9518-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam JF, Yoon G, Dickerson DL, Kim SW, & Westermeyer J (2015). Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in five groups with different severities of gambling: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The American journal on addictions, 24(4), 292–298. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers HF, Sumner LA, Ullman JB, Loeb TB, Carmona JV, & Wyatt GE (2009). Trauma and psychosocial predictors of substance abuse in women impacted by HIV/AIDS. The journal of behavioral health services & research, 36(2), 233–246. doi: 10.1007/s11414-008-9134-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson J, Elmasry H, Das B, Smiley S, Rubin L, Deatley T, … Abrams D (2017). Comparison of ecological momentary assessment versus direct measurement of E-cigarette use with a Bluetooth-enabled E-cigarette: A pilot study. JMIR Research Protocols, 6(5), E84. doi: 10.2196/resprot.6501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellowski JA, Kalichman SC, Matthews KA , & Adler N (2013). A pandemic of the poor: Social disadvantage and the U.S. HIV epidemic. American Psychologist, 68(4), 197–209. doi: 10.1037/a0032694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radcliffe J, Beidas R, Hawkins L, & Doty N (2011). Trauma and sexual risk among sexual minority African American HIV-positive young adults. Traumatology, 17(2), 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchwood T, DeCoster J, Metzger I, Bolland J, & Danielson C (2016). Does it really matter which drug you choose? An examination of the influence of type of drug on type of risky sexual behavior. Addictive Behaviors, 60, 97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera DM, Varas DN, Coriano OD, Padilla M, Reyes EM, & Serrano N (2015). Ellos de la calle, nosotras de la casa: El discurso patriarcal y las experiencias de mujeres que viven con el VIH/SIDA en Puerto Rico 1/They belong to the street, we belong to the house: Patriarcal discourse and experiences of women living with HIV/AIDS in Puerto Rico. Cuadernos De Trabajo Social, 28(1), 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sherin JE, & Nemeroff CB (2011). Post-traumatic stress disorder: The neurobiological impact of psychological trauma. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 13(3), 263–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson T, Stappenbeck C, Varra A, Moore S, & Kaysen D (2012). Symptoms of posttraumatic stress predict craving among alcohol treatment seekers: Results of a daily monitoring study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 26(4), 724–733. doi: 10.1037/a0027169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smiley S, Elmasry H, Webb Hooper M, Niaura R, Hamilton A, & Milburn N (2017). Feasibility of ecological momentary assessment of daily sexting and substance use among young adult African American gay and bisexual men: A pilot study. JMIR Research Protocols, 6(2), E9. doi: 10.2196/resprot.6520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soller M, Kharrazi N, Prentiss D, Cummings S, Balmas G, Koopman C, & Israelski D (2011). Utilization of psychiatric services among low-income HIV-infected patients with psychiatric comorbidity. AIDS Care, 23(11), 1351–1359. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.565024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spies G, Afifi TO, Archibald SL, Fennema-Notestine C, Sareen J, & Seedat S (2012). Mental health outcomes in HIV and childhood maltreatment: A systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 1(1), 1–30. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus SE, Johnson MO, Marquez C, & Feldman MD (2013). Characteristics of successful and failed mentoring relationships: a qualitative study across two academic health centers. Academic medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 88(1), 82–89. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31827647a0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tervalon M, & Murray-Garcia J (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 9(2):117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinto V (1975). Dropout from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research, 45(1): 89–125. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuyuki K, Pitpitan EV, Levi-Minzi MA, Urada LA, Kurtz SP, Stockman JK, & Surratt HL (2017). Substance use disorders, violence, mental health, and HIV: differentiating a syndemic factor by gender and sexuality. AIDS and Behavior, 21(8), 2270–2282. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1841-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrka A, Price L, Marsit C, Walters O, Carpenter L, & Uddin M (2012). Childhood adversity and epigenetic modulation of the leukocyte glucocorticoid receptor: Preliminary findings in healthy adults (GR Epigenetic Modulation and Childhood Adversity). PLoS ONE, 7(1), E30148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varas-Díaz N, Rivera M, Rivera-Segarra E, Neilands TB, Ortiz N, Pedrogo Y, … Albizu-García CE (2017). Beyond negative attitudes: Examining HIV/AIDS stigma behaviors in clinical encounters. AIDS Care, 29(11), 1437–1441. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1322679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermont Center on Behavior and Health (2018). http://www.med.uvm.edu/behaviorandhealth/researchtraining. Accessed May 26, 2018.

- Viets VL, Baca C, Verney SP, Venner K, Parker T, & Wallerstein N (2009). Reducing health disparities through a culturally centered mentorship program for minority faculty: The Southwest Addictions Research Group (SARG) experience. Academic medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 84(8), 1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt M, Dennis H, Choi A, Ciya C, Joska K, Robertson W, & Sikkema N (2017). Impact of sexual trauma on HIV care engagement: Perspectives of female patients with trauma histories in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS and Behavior, 21(11), 3209–3218. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1617-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt M, Eaton H, Dennis L, Choi A, Kalichman A, Skinner C, & Sikkema K (2016). Alcohol use during pregnancy in a South African community: Reconciling knowledge, norms, and personal experience. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20(1), 48–55. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1800-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt M, Guidera K, Hobkirk A, Skinner D, & Meade C (2017). Intimate partner violence among men and women who use methamphetamine: A mixed methods study in South Africa. Drug and Alcohol Review, 36(1), 97–106. doi: 10.1111/dar.12420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt M, Kimani H, Skinner S, & Meade M (2016). “Nothing Is Free”: A qualitative study of sex trading among methamphetamine users in Cape Town, South Africa. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(4), 923–933. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0418-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt M, Myers B, Towe S, & Meade C (2015). The mental health experiences and needs of methamphetamine users in Cape Town: A mixed methods study. South African Medical Journal = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif Vir Geneeskunde, 105(8), 685–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt GE, Williams JK, Gupta A, & Malebranche D (2012). Are cultural values and beliefs included in US based HIV interventions? Preventive Medicine, 55(5), 362–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt GE, Williams JK, Henderson T, & Sumner L (2009). On the outside looking in: Promoting HIV/AIDS research initiated by African American investigators. American Journal of Public Health, 99, S48–S53. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.131094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager J, Waitzkin H, Parker T, & Duran B (2007). Educating, training, and mentoring minority faculty and other trainees in mental health services research. Academic Psychiatry, 31(2), 146–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaribeygi H, Panahi Y, Sahraei H, Johnston T, & Sahebkar A (2017). The impact of stress on body function: A review. EXCLI Journal, 16, 1057–1072. doi: 10.17179/excli2017-480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]