The novel coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), was initially discovered in November 2019 in Wuhan, China. The associated human disease, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), rapidly became a global pandemic.1 By March 2020, the USA began to experience its first wave of infections, with New York City at the epicentre. In the hardest hit areas, healthcare facilities were overwhelmed. Critically ill patients exceeded the capacity of ICUs, operating rooms were converted to makeshift ICUs, and temporary satellite hospitals were erected to divert care for non-critically ill patients.2

With the introduction of social distancing, contact tracing, mandatory masks, and similar public health measures, New York City and the surrounding area were ultimately able to ‘flatten the curve’.3 Months later, as other US cities and states began to relax their stay-at-home restrictions and people across the USA optimistically prepared to resume their former lives, cases began to increase again at an alarming rate, especially in southern and western states.4 Although there is debate among epidemiologists whether the recent increase in cases constitutes a ‘second wave’ or an ongoing first wave, the overriding consensus is that the COVID-19 pandemic is far from over.5 Thus, we have become accustomed to social distancing, mask regulations, and quarantine measures, the ‘new normal’. These measures will likely remain in place until the development and widespread administration of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Several companies including Moderna and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in the USA and University of Oxford and AstraZeneca in the UK have entered phase 3 trials for a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and plan on having results by early 2021.

With the growing number of infected people there is a simultaneous increase in the number of recovered patients with chronic needs, so-called ‘long-haulers’. People who have cleared their SARS-CoV-2 infections are not all symptom-free. Many report continued fatigue, joint and bone pain, palpitations, headaches, dizziness, and insomnia. There is also concern for irreversible pulmonary scarring and dysfunction, especially in patients with severe pulmonary disease.6 Given that the virus has only been known for a matter of months, long-term studies simply do not exist yet, and the outlook for these patients remains completely unknown. There are likely to be many chronic consequences of COVID-19 beyond the initial wave of acute infections that will be uncovered in the coming months and years.

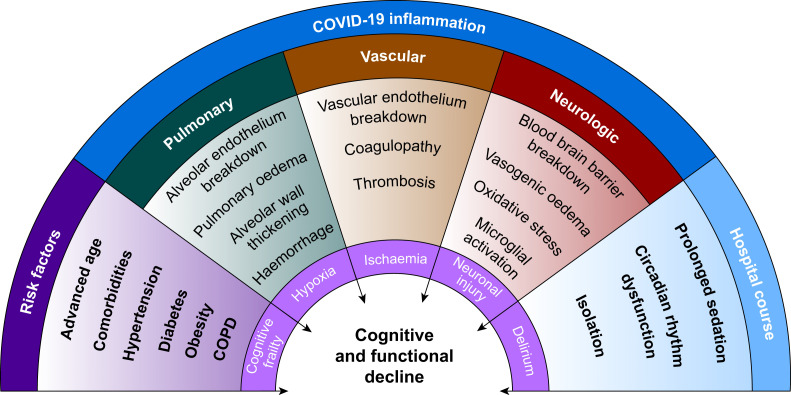

One long-term impact of COVID-19 that is becoming increasingly apparent is its effect on cognitive function, even in those with mild symptoms. One-third of COVID-19 patients report neurological symptoms, and there have been anecdotal accounts of ‘COVID-19 delirium’, manifesting as paranoid hallucinations, confusion, and agitation in more than 20% of hospitalised patients.7 , 8 A small study from the UK reported delirium in 42% of COVID-19 patients.9 One of the highest-risk groups for severe manifestations of COVID-19, patients more than 65 yr old, often have underlying mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and are already at increased risk of delirium as a result of underlying ‘neurocognitive frailty’.10 , 11 COVID-19-related inflammation also increases susceptibility to silent infarcts, blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability, thrombosis, and coagulopathy, all of which may further propagate neurological injury.12 Moreover, the clinical management of these patients, including patient isolation, lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) resulting in reduced staff contact, lack of family/visitors, and long-term ventilation/sedation, not only places them at high risk for delirium and subsequent cognitive deficits, but also likely under-diagnosis of delirium. Taken together, there is growing evidence that a patient's COVID-19 risk factors, pathology, and treatment course can independently and synergistically contribute to development of long-term cognitive and functional decline (Fig. 1 ). In addition to poor outcomes for patients, the severe agitation associated with delirium in many COVID-19 patients in the ICU creates difficulties for staff and compounds the stress of caring for these extremely sick patients.

Fig 1.

Wheel of factors contributing to long-term cognitive and functional decline in COVID-19 survivors. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

COVID-19 risk factors and underlying neurocognitive frailty

Risk factors for severe COVID-19 infection include advanced age,13 medical comorbidities, most commonly hypertension (40–60%), diabetes mellitus (20–40%), obesity (40–50%),14 and smoking.15 This population overlaps significantly with at-risk groups for MCI and cognitive decline, which include advanced age, traumatic brain injury, obesity, hypertension, current smoking, and diabetes mellitus.16 Together, such risk factors represent a baseline neurocognitive frailty that can increase susceptibility to cognitive complications during and after inflammatory states,17 similar to perioperative neurocognitive disorders associated with surgery and anaesthesia.11 Thus, the highest risk individuals for severe COVID-19 infection may also represent the most inherently susceptible population for cognitive decline in the setting of COVID-19 inflammation.

The multisystemic role of COVID-19 inflammation in cognitive decline

Pulmonary: hypoxaemia

Pulmonary dysfunction in COVID-19 is propagated by SARS-CoV-2 infection of ciliated bronchial epithelial cells and type-II pneumocytes. The virus gains entry into these cells by binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, triggering viral endocytosis. Subsequently, the viral surface spike (S) glycoprotein is cleaved by the transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) causing release of viral contents and propagation of the infection.18

The lung damage and resulting hypoxaemia caused by COVID-19 likely contribute indirectly to neuronal injury and subsequent cognitive decline. Cognitive impairment is frequently seen in patients with chronic hypoxaemia, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and obstructive sleep apnoea.19 , 20 Similarly, patients with COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) can exhibit severe hypoxaemia despite relatively well-preserved lung mechanics.21 This ‘silent hypoxaemia’ has been described in COVID-19 patients as ‘oxygen levels incompatible with life without dyspnoea’.22 In critically ill patients with COVID-19, the resulting hypoxaemia has largely necessitated tracheal intubation and prolonged mechanical ventilation to address the ensuing chronic hypoxaemic state.

Vascular: coagulopathy and thrombosis

SARS-CoV-2 has also been found to invade endothelial cells, leading to vascular inflammation and a high rate of superimposed arteriovenous thrombotic complications.23 SARS-CoV-2 can also cause a systemic vasculitis and cytokine storm that can damage a range of organ systems, with renal, hepatic, dermatological, and cardiac manifestations. Cardiac complications are among the most severe in COVID-19 infection, ranging from fulminant myocarditis to heart failure and cardiac arrest.24

The hypercoagulable and hyperinflammatory states seen in severe COVID-19 may contribute to delirium and future cognitive decline, as inflammation and coagulopathy are independently associated with an increased risk of delirium and poor outcomes in critically-ill patients.12 Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 infection can cause susceptibility to silent infarcts and thromboses via microemboli.

Neurological: BBB breakdown, microglial activation, and direct neuronal injury

Neuroinflammation can cause cognitive dysfunction by compromising the BBB.10 In both animals and humans, inflammatory insults can cause upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and inflammatory mediators in the serum and CNS.11 Peripheral pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6, and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) compromise BBB permeability via cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) upregulation and matrix metalloprotease (MMP) activation. Once the BBB is disrupted, cytokines can enter the CNS and cause microglial activation and oxidative stress, leading to synergistic cognitive impairment. The resulting neuroinflammation can contribute to delirium in the short term and severe long-term cognitive deficits.25

Iatrogenic factors and hospital delirium

In addition to the baseline cognitive susceptibility of high-risk patients and the neurological effects of COVID-19 inflammation, patients affected with COVID-19 often have hospital courses that can further contribute to cognitive decline. Acute mental status changes, such as delirium, are common in hospitalised COVID-19 patients. Delirium itself is associated with subsequent cognitive decline,26 and is a common occurrence in ICU patients, as observed in ARDS.27

Despite the known iatrogenic contributors to cognitive decline in COVID-19 patients, many COVID-19 patients were denied typical precautions and interventions for cognitive health because of the transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 and the increased load of critically ill patients in the first wave. Our experience in a New York City hospital reflects this course: patients were intubated early in their disease progression, often with limited family contact. These mechanically ventilated patients experienced prolonged periods of ‘iatrogenic hypoxaemia’, as it is common to maintain Pao 2 values as low as 55 mm Hg (7.3 kPa) or Sao 2 concentrations as low as 88% in ARDS management.28 Ventilated patients were commonly agitated and required prolonged sedation with multiple agents to prevent self or staff harm. Although arousal and auditory functions, such as a patient hearing their name spoken by a familiar voice, are some of the most effective measures for emergence from disorders of consciousness,29 simple measures such as this are difficult to implement because of pandemic precautions.

Both short- and medium-term neurological deficits are already being observed in both critically ill and non-critically ill COVID-19 survivors, although long-term studies are yet to be completed. In fact, the fourth most common presenting symptom of COVID-19 is confusion or altered consciousness, suggesting both direct and indirect early neurological consequences. These data raise serious concerns regarding subsequent development of cognitive and functional decline in these patients, as cognitive decline is largely an insidious process after a heralding neurological or neurocognitive insult. Moreover, cognitive decline does not occur in isolation; rather it manifests in reduced quality of life and impaired ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental ADLs (IADLs). Cognitive decline is often undiagnosed until it is more advanced and accompanied by moderate to severe functional deficits.

It may benefit our cumulative research efforts to consider the long-term effects of COVID-19 in alignment with anaesthesia and surgery, which are known precipitants of inflammation-related cognitive and functional decline. Given the overlapping inflammatory response to injury for both, this may allow us to pre-empt poor cognitive and functional outcomes for COVID-19 patients, and work to implement preventive interventions or treatments that may alleviate long-term consequences of COVID-19. Drawing on the vast body of literature addressing perioperative neurocognitive disorders, which have a similar inflammatory component, may facilitate advances in strategies for both, and other neurological injuries, in a relatively short timeframe.

In summary, COVID-19 risk factors, pathology, hospital course, and patient factors comprise multiple neurological insults that likely predispose patients to long-term cognitive dysfunction and functional decline. It is critical that we assess and monitor COVID-19 survivors for cognitive impairment, poor psychosocial outcomes, and functional decline. Research addressing the neurological sequelae of COVID-19, anaesthesia, and surgery, and other inflammatory disorders are imperative to reduce or prevent these poor outcomes for COVID-19 survivors, as well as for other inflammatory disease-related neurological insults.

Authors' contributions

Wrote the first draft of the manuscript and prepared the figure: HAB

Co-wrote the manuscript, provided accounts of clinical care for COVID-19 survivors, and assisted in figure preparation: SAS

Conceived the idea and edited the manuscript: LAE

Funding

HAB is supported by a Medical Scientist Training Program grant (T32 GM007739) from the US National Institute of General Medical Sciences to the Weill Cornell/Rockefeller/Sloan-Kettering Tri-Institutional MD-PhD Program. SAS is supported by a Medical Research Training Grant (MRTG-02-15-2019-Safavynia) from the Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research.

Declarations of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the paid and volunteer healthcare workers who came to New York-Presbyterian Hospital and provided excellent clinical care for patients affected with COVID-19 during the pandemic.

References

- 1.Peng P.W.H., Ho P.L., Hota S.S. Outbreak of a new coronavirus: what anaesthetists should know. Br J Anaesth. 2020;124:497–501. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jotwani R., Cheung C.A., Hoyler M.M., et al. Trial under fire: one New York City anaesthesiology residency programme's redesign for the COVID-19 surge. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:e386–e388. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.06.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris J.E. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.; 2020. The coronavirus epidemic curve is already flattening in New York city. NBER Working Papers 26917. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanne J.H. Covid-19 cases increase steeply in US south and west. BMJ. 2020;369:m2616. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hazem Y., Natarajan S., Berikaa E. Hasty reduction of COVID-19 lockdown measures leads to the second wave of infection. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.23.20111526. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spagnolo P., Balestro E., Aliberti S., et al. Pulmonary fibrosis secondary to COVID-19: a call to arms? Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:750–752. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30222-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mao L., Jin H., Wang M., et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:683–690. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helms J., Kremer S., Merdji H., et al. Neurologic features in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2268–2270. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2008597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mcloughlin B.C., Miles A., Webb T.E., et al. Functional and cognitive outcomes after COVID-19 delirium. Eur Geriatr Med. 2020;11:857–862. doi: 10.1007/s41999-020-00353-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Safavynia S.A., Arora S., Pryor K.O., García P.S. An update on postoperative delirium: clinical features, neuropathogenesis, and perioperative management. Curr Anesthesiol Rep. 2018;8:252–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Safavynia S.A., Goldstein P.A. The role of neuroinflammation in postoperative cognitive dysfunction: moving from hypothesis to treatment. Front Psychiatry. 2019;9:752. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Girard T.D., Ware L.B., Bernard G.R., et al. Associations of markers of inflammation and coagulation with delirium during critical illness. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:1965–1973. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2678-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garg S., Kim L., Whitaker M., et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019—COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Weekly Rep. 2020;69:458–464. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cummings M.J., Baldwin M.R., Abrams D., et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1763–1770. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddy R.K., Charles W.N., Sklavounos A., Dutt A., Seed P.T., Khajuria A. The effect of smoking on COVID-19 severity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol Adv. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.26389. Access published on August 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baumgart M., Snyder H.M., Carrillo M.C., et al. Summary of the evidence on modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia: a population-based perspective. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:718–726. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robertson D.A., Savva G.M., Kenny R.A.J. Frailty and cognitive impairment—a review of the evidence and causal mechanisms. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12:840–851. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thakur N., Blanc P.D., Julian L.J., et al. COPD and cognitive impairment: the role of hypoxemia and oxygen therapy. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2010;5:263–269. doi: 10.2147/copd.s10684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yerlikaya D., Emek-Savaş D.D., Kurşun B.B., Öztura İ., Yener G.G. Electrophysiological and neuropsychological outcomes of severe obstructive sleep apnea: effects of hypoxemia on cognitive performance. Cogn Neurodyn. 2018;12:471–480. doi: 10.1007/s11571-018-9487-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gattinoni L., Chiumello D., Rossi S. COVID-19 pneumonia: ARDS or not? Crit Care. 2020;24:154. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02880-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tobin M.J., Laghi F., Jubran A. Why COVID-19 silent hypoxemia is baffling to physicians. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:356–360. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202006-2157CP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Varga Z., Flammer A.J., Steiger P., et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1417–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehra M.R., Ruschitzka F.J.J.H.F. COVID-19 illness and heart failure: a missing link? JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8:512–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cunningham C. Systemic inflammation and delirium: important co-factors in the progression of dementia. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:945–953. doi: 10.1042/BST0390945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis D.H., Muniz-Terrera G., Keage H.A., et al. Association of delirium with cognitive decline in late life: a neuropathologic study of 3 population-based cohort studies. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:244–251. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsieh S.J., Soto G.J., Hope A.A., Ponea A., Gong M.N. The association between acute respiratory distress syndrome, delirium, and in-hospital mortality in intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:71–78. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201409-1690OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bein T., Grasso S., Moerer O., et al. The standard of care of patients with ARDS: ventilatory settings and rescue therapies for refractory hypoxemia. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:699–711. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4325-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee H.Y., Park J.H., Kim A.R., Park M., Kim T.-W. Neurobehavioral recovery in patients who emerged from prolonged disorder of consciousness: a retrospective study. BMC Neurol. 2020;20:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12883-020-01758-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]