Abstract

This study analyzes real experiences of culture management to better understand how ethics permeates organizations. In addition to reviewing the literature, we used an action-research methodology and conducted semistructured interviews in Spain and in the U.S. to approach the complexity and challenges of fostering a culture in which ethical considerations are a regular part of business discussions and decision making. The consistency of findings suggests patterns of organizational conditions, cultural elements, and opportunities that influence the management of organizational cultures centered on core ethical values. The ethical competencies of leaders and of the workforce also emerged as key factors. We identify three conditions—a sense of responsibility to society, conditions for ethical deliberation, and respect for moral autonomy—coupled with a diverse set of cultural elements that cause ethics to take root in culture when the opportunity arises. Leaders can use this knowledge of the mechanisms by which organizational factors influence ethical pervasiveness to better manage organizational ethics.

KEYWORDS: Business ethics, Ethical culture, Culture management, Ethical decision-making, Cultural change

1. Business ethics and culture management

In the last 40 years, globalization, accelerated by technological development, has transformed the context in which companies work and compete (Dolan & Raich, 2009). Technology amplifies the influence of a broad group of social and political actors that have no financial stakes in companies (Kennedy, 2013). Managers have to deal with this complex and dynamic framework of social, organizational, and individual drivers of socially responsible performance. Instances of these drivers include policies, laws, and regulations (social factors); organizational ethics and tone at the top (organizational factors); and individual preferences of customers, employees, and investors. Moreover, these drivers are evolving dynamically at all three levels in response to the consequences of globalization (Aguinis & Glavas, 2012). Environmental degradation, growing inequality, the 2007-2009 financial crisis, and the global COVID-19 pandemic have revived the debate on ethics in the business realm.

As a result, researchers and managers have shown renewed interest in managing organizational ethics. Companies began incorporating new values and goals beyond economic profit in their organizational cultures as a strategy to deal with the dynamic and uncertain context in which they are operating (Garriga & Melé, 2004). Thus companies’ social roles and ways of doing business have evolved (Freeman, 2017). In August 2019, the Business Roundtable redefined the purpose of a corporation as promoting an economy for the benefit of all stakeholders; not just shareholders but also customers, employees, suppliers, and communities (Business Roundtable, 2019). They did not, however, explain how companies would achieve this new purpose. Many companies are adopting culture management, including ethics, as a strategy for meeting social demands (Treviño et al., 2014). But neither the traditional triple bottom line nor the culture underpinning decisions have fully encompassed ethics (Burford et al., 2016). One of the main causes of the 2007–09 financial crisis was the lack of ethics in management. Ethics has received more attention since then owing to high-profile ethical dilemmas in the technology sector, long considered an economic bellwether. Governance is also now focused on ethical culture. In 2017, the NACD Blue Ribbon Commission recommended that boards should monitor their organizations’ culture and integrate it into ongoing discussions with management about strategy, risk, and performance (NACD, 2017). Although companies linked to the financial crisis and companies in the technology industry had strong reputations for corporate social responsibility and appeared to embrace ethics, the behavior of some managers in these companies was clearly unethical (Sims & Brinkmann, 2009).

The predominant approach to culture management has focused on the alignment of values between the individual employee and the organization (DiStaso, 2017). As a consequence, research has focused primarily on individual factors—age, behavior, personal values, or organizational commitment—more often than on organizational factors, such as culture, policies, rewards, or training (Lehnert et al., 2015).

But everyday business practices have challenged the idea of a direct link between values and behavior that underlies this familiar paradigm. When inconsistencies or conflicts are perceived to threaten cognitive frameworks, individuals (Lord & Brown, 2001; Watson et al., 2004) and groups (List & Pettit, 2011) adjust their values to preserve integrity, affirm a positive self-image, or support contextual pressures that orient their behaviors. Therefore, behaviors may be most effectively influenced if management shifts its focus from defining values to creating a learning process that builds and activates a shared ethical culture (Appelbaum et al., 2007; Watson et al., 2004). Caterina Bulgarella used the appealing metaphor of an “architect of culture” to describe this new paradigm, offering fresh insights for facing the complexity of managing culture and ethics (Ethical Systems, 2018).

This study focuses on the organizational level. Using a model developed by Gutiérrez Díez (1996) proved remarkably effective to connect elements of culture to conditions and opportunities to build shared ethical culture. It revealed patterns between the types of cultural elements in use, the conditions present in the company, and the organization’s ability to take advantage of opportunities for promoting ethics in the company. Companies can use these findings to establish mechanisms to build individual and organizational ethical abilities and successfully manage their organizational ethics.

2. Managing culture to manage ethics

Culture relates to a unique shared purpose and set of values articulated in a system that internally provides a shared mindset for employees. It shapes how a company interacts with its context, orients its decision-making processes, and performs its functions (Flamholtz & Randle, 2011; Schein, 1990). Therefore, culture influences the degree to which ethics becomes embedded within an organization. It makes sense that intentionally managing culture is an appropriate strategy to promote ethics (Treviño et al., 2014).

Gutiérrez Díez (1996) proposed four groups of cultural elements after studying previous approaches based on Schein’s (1990) culture framework of basic assumptions, espoused values, and cultural artifacts. Gutiérrez Díez’s model helps to further define the visible and invisible aspects of culture, a relevant topic in contemporary business literature (Rick, 2015). The types of elements, from minor to major visibility, are normative, symbolic, declarative and structural.

-

•

Normative elements constitute a framework to explain reality, to understand how it is and how it should be. Examples of these elements are beliefs, implicit values or standards, sanctions, or taboos.

-

•

Symbolic elements include rites, ceremonies, the physical appearance of facilities, attire, logos, exemplary people or heroes, organizational codes, stories, and myths, and group jargon that create feelings of unity among employees.

-

•

Declarative elements are statements and formal declarations of mission, vision and values statements, codes, industry pledges, public messages, or internal messages to employees.

-

•

Structural elements involve organizational structures and visible procedures using the previous elements, including organizational charts and hierarchies, communication and dialogue channels, internal participation mechanisms, and human resource management (Gutiérrez Díez, 1996).

Literature and practice identified three main steps in the process of designing and managing organizational culture. The first step is the definition or redefinition of shared values that the company declares and communicates. The second step is using those values in decision making, inculcating them into organizational life and practices. Finally, the alignment of policies and procedures with the values affirms and consolidates culture in signs and observable behaviors in the company (Arthur W. Page Society, 2012; Treviño et al., 2014). As a result, the different elements of culture develop as the company evolves; thus more evolved, mature companies present a greater variety of cultural elements.

Still, the incorporation of ethics cannot be taken for granted in the complex process of culture management. All too often, companies do not use ethical principles in culture management or in establishing a hierarchy of organizational values. For ethics to permeate the organization, the steps of culture management should incorporate ethical values in order to build ethical cultures (Grandy & Sliwa, 2017).

Cultures are ethically sound when the shared set of values is ethically conceivable and credible both inside and outside of the company. Employees must perceive decisions as ethically consistent with their personal values, so that they and the groups they participate in are committed to acting according to this common ethical framework and to revisiting it as new obligations arise (Haski-Leventhal et al., 2015; Rothschild, 2016). At the same time, political and social agents outside of the company must see the business culture in this same way for ethics to take hold over time.

But even when managers are committed to orienting organizational culture ethically, they may not know how to effectively integrate ethics. Moreover, two companies with similar conditions can also differ in the way and extent to which they incorporate ethics (Eccles et al., 2014). So how does ethics permeate organizations to create ethical cultures and encourage moral behavior? What are the cultural elements influencing ethics to take root in culture?

3. Finding patterns in how companies encourage ethics

To answer these questions, we have studied the real experiences companies have had incorporating ethics in their cultures. We analyzed experiences of 18 businesspeople diverse in terms of age, seniority, and leadership positions. Their companies varied in size and type of industry, and they operated in two countries with different cultural, political, and regulatory frameworks on two different continents. All participants interviewed were engaged in ethical forums promoted by university centers of applied ethics. These executives have been participating, some for many years, in a group that meets regularly to discuss ethics in a confidential setting, allowing a learning community to form over time. They are a sample of motivated, ethically aware leaders in high- and medium-level positions who are willing to share information about their companies based on relationships they held with each of the ethics centers over time. We felt it likely that we would be able to study the ethical evolution of culture in their companies in enough detail to truly examine decision making and other actions taken in these companies in the context of promoting ethics in organizational cultures.

We started the study at the Centre for Applied Ethics at Spain’s University of Deusto, with nine men and three women. In three half-day sessions, this learning community analyzed two real cases of cultural change and discussed them with experts to identify patterns of ethics pervasiveness. In the U.S., we posed the same questions answered in Spain to another six businessmen from the learning community at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. Individual semistructured interviews with participants at their companies helped us reconstruct the ways ethics had been introduced. The analysis of data confirmed and enriched the patterns identified in Spain. As a final step, we presented our conclusions to the learning community in Spain for further discussion and validation.

Our study, although its sample is small, meets conditions for the validity of findings (Guest et al., 2006). But some characteristics of participants may introduce bias, so further studies, with a wider group of companies and incorporating greater participant diversity, are required to confirm and complete the patterns identified here.

3.1. Getting ethics into organizations

From the data we collected, patterns emerged around three aspects. First, we identified some consistent situations with similar characteristics that companies used to embed ethical principles in corporate culture. We named the three types of situations opportunities. These opportunities correlate well with the main stages of building organizational culture, so we used them to classify our findings. Second, we identified three conditions present in companies successful at promoting ethics in their cultures. Finally, we found that a mix of cultural elements, rather than overreliance on one or two types, contributed to ethics in the culture. More mature companies used a greater array of elements and had more and better developed practices for promoting ethics.

Opportunities of the first type, which we refer to as turning points, are challenging situations rife with difficulty, uncertainty, or complexity. These situations are opportunities to introduce and incorporate ethics. A second type of opportunity emerged around decision-making processes, which can be informed by ethics. Finally, transmission of ethics in culture, resulting in the broader dissemination and further strengthening of the norms shared throughout the company, is another opportunity to affirm culture. In some stories, participants described companies’ abilities to leverage one situation for more than one type of opportunity. For example, they leveraged staff turnover—a turning point—not only for introducing but also for affirming ethics; or they used development of ethical skills—an example of transmission— to both affirm and use values (Table 1 ). This suggests a cyclical dynamic in the process of introducing, using, and affirming ethical values (Lozano, 2009; Treviño et al., 2014).

Table 1.

Examples of opportunities

| Examples of opportunities | Leveraged for |

|---|---|

|

Turning points: Challenging situations rife with difficulty, uncertainty, or complexity that buck current culture or practices. | |

| External | |

|

Introducing values |

|

Introducing values |

|

Introducing values |

|

Introducing (in one case, also using) values |

| Internal | |

|

Introducing values |

|

Introducing values |

|

Introducing values |

|

Introducing (in a few cases, also affirming) values |

|

Introducing (in one case, also using) values |

|

Decision-making processes in which realities test existing norms and policies. | |

| Decisions about policies, products, or services | Using values |

| Operational decisions | Using values |

| Decisions about procedures |

Using (in one case, also affirming) values |

|

Transmission of culture: Communication and transmission of ethical practices and norms. | |

| Deployment, standards of services, or cultural norms in individual behavior | Affirming values |

| Training of new employees | Affirming values |

| Some individuals’ lack of ethical motivation | Affirming values |

| Measuring and developing ethical skills | Affirming (in one case, also using) values |

We found three conditions that, when present in companies, made it easier for them to leverage opportunities to promote ethics in the organization. The first condition was a responsibility to society, implying awareness and acceptance of the company’s role in society beyond economic transactions. When this existed, participants confirmed that the company engaged with social agents, assumed its social duties, and held itself accountable (Aßländer & Curbach, 2014; Dembinski, 2011). The second condition is the respect of moral autonomy and a climate of mutual trust, which is when the moral arguments or ethical concerns of all individuals are heard in situations that affect them or in which they have expertise. The final condition is ethical deliberation, the main principles of which are (List & Pettit, 2011; Stansbury, 2009):

-

•

The use of information to clarify the ethical dilemma;

-

•

The respect of individuals’ moral autonomy that allows a deliberative process to reach a consensus based on moral arguments;

-

•

The consideration of downstream effects of the decision; and

-

•

Sharing the motivations behind that decision in a transparent way throughout the company.

3.2. Patterns of conditions and cultural elements that support ethics

Participants described the evolution of ethical culture in their companies, and we identified significant coincidences in sets of conditions coupled with specific cultural elements put in place to leverage opportunities (Table 2 ). Although we asked about successful experiences, participants also discussed inhibitors working against the pervasiveness of ethics in culture that also supported the patterns. For example, participants reported that if organizational conditions were not present, cultural elements identified as enablers of leveraging opportunities to promote ethics would not be influential.

Table 2.

Patterns of opportunities, conditions, and cultural elements

| Opportunities | Conditions | Specific elements of culturea |

|---|---|---|

| Turning points |

Sense of responsibility to society | Enablers of ethical leadership |

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Respect for moral autonomy/climate of trust |

Attention to social or individual values | |

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Decision-making |

Ethical deliberation conditions | Frameworks for decision-making |

| ||

| ||

| Sense of responsibility to society | Structures for responsibility, authority, and accountability | |

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Respect for moral autonomy/climate of trust |

Consolidation of ethical deliberation conditions | |

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Development of ethical motivation and competence | ||

| ||

| ||

| Transmission of culture | Respect for moral autonomy/climate of trust | Description of culture |

| ||

| Means of transmitting culture | ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Enablers of consistency in implementation | ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

|

N. Normative elements of culture, D. Declarative, Sy. Symbolic, St. Structural

While the study focused on organizational factors, an unprompted, recurring reference to individual capabilities emerged, indicating their essential role in the success of iterative learning in culture management. All participants mentioned the importance of individual ethical attitudes and competencies. For example, participants cited reflection and learning capabilities (Treviño et al., 2014). The specific individual factors emerged largely in the six interviews conducted in the U.S., which could be due to the different methodologies used in the two locations. Therefore, our observations about leadership skills and competencies from this study are only a promising starting point; more research may discern whether there are indeed patterns of individual moral capabilities that also contribute to promoting ethics in workplaces.

The patterns shed light on the mechanisms by which conditions and cultural elements influence the pervasiveness of ethics in the company. The Markkula Center for Applied Ethics used the patterns in the design of a World Economic Forum survey about creating ethical culture conducted among 99 respondents, confirming their ability to shed light on the organizational processes (Skeet & Guszcza, 2020). The next subsections explain the mechanisms in each type of opportunity that we were able to identify (Table 2).

3.2.1. Mechanisms to introduce ethics

When companies find themselves at turning points opportune for introducing ethics, they should decide whether to incorporate new principles or values to reinforce their organizational ethics. These turning points may be external or market-based, such as pressure from major stakeholders, unfavorable economic conditions, or legal or regulatory changes, or they may be internal, such as changes in leadership, staff turnover, conflict resolution, or poor economic performance (Aguinis & Glavas, 2012). Indeed, large companies in both the U.S. and the EU have had to address issues of ethics and corporate culture due to the Federal Sentencing Guidelines (U.S.) and the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation. We even observed some companies intentionally creating turning-point opportunities by rotating employees through different assignments so someone in a new role could introduce ethics from a fresh perspective. Several companies used outside consultants as a mechanism for generating turning-point opportunities that would promote ethics.

When the first condition, the sense of responsibility to society, was present, it allowed leaders to take advantage of all these turning points, including changes in procedures, to meet sociological and cultural diversity or to reinforce social responsibility as the company grew. We also observed evidence of the second condition, the respect for individual moral autonomy, especially when individuals were willing to identify issues without fear of retaliation. Several examples highlighted how staff were motivated to uncover ethical problems or conflicts of interest and how people were empowered to make recommendations even to reverse prior decisions, thus creating turning points.

The most commonly mentioned cultural elements during turning points were those enabling formal or informal ethical leadership or bringing attention to social or individual ethical values (Table 2). Spanish participants were more likely to mention normative elements in turning points, while North Americans referred more often to declarative elements, which may be due to cultural differences. Some of the specific symbolic elements mentioned in both locations included exemplary people as promoters of ethics, attention to legacy by founders, and ceremonies observing volunteer work outside the company, suggesting that role models can be highly influential in moral engagement (Appelbaum et al., 2007). One company developed country profiles—a structural element—to improve cultural sensitivity in preparation for future turning-point opportunities in different settings around the globe.

3.2.2. Mechanisms fostering ethical decision-making

We found that opportunities to use ethics arise in decisions about policies, products or services, and procedures, as well as in operational decisions. Ethical decision-making is critical in managing ethics in organizations (Bowen, 2004; Lehnert et al., 2015). Our respondents described decisions that led to changes in policies, codes, or internal messages, favoring the spread of values throughout the company and showing the ability of the company to leverage the connection between two of the steps of culture management: the use of and the affirmation of values.

Although three conditions were present in the decision-making examples, two of them seem to be most relevant. Participants mentioned specific examples of ethical deliberation in decision-making situations entailing individual accountability and involving people in the creation of certain standards for which they were going to be held responsible. Participants, especially in the U.S., mentioned a sense of responsibility to the society in which the company operates when making decisions related to policies or procedures affecting stakeholders in diverse cultural or social contexts. Moreover, in the absence of either a sense of responsibility to society or of conditions conducive to moral deliberation, companies were less likely to use ethics when making decisions. In one example, the company was more interested in appearing neutral, in terms of its impact on society, than in making any value judgment about what the right thing to do would be in certain circumstances. The company did not expect to be held accountable for the downstream implications of its decisions.

The cultural elements drawn upon in the use of ethics included normative and declarative elements that shaped decision-making frameworks, and structural elements allowing companies to establish or clarify responsibility and accountability, to support the conditions for ethical deliberation, and to develop ethical motivations and abilities. These elements aim to clarify rather than to impose how ethics can be used (Bowen, 2004; List & Pettit, 2011) (Table 2). Interviewees in startups mentioned normative elements more, while people in more established companies mentioned declarative and structural elements, reinforcing how critical these implicit elements are when a company is in its earliest days and has not yet developed declarative and structural elements.

Ethical decision-making can be inhibited by a lack of certain conditions or by a mix of cultural elements. In one case, the interviewee assured us that all employees were free to confront management, which sounded admirable in principle. But he went on to say there were no mechanisms in place to consult people affected by decisions or to share the reasons behind them. In other words, even when there is a will to respect moral autonomy, it is hard for decision-making to follow ethical principles if the conditions for ethical deliberation are absent. Additionally, a lack of policies that spell out responses for employees in specific situations, both when dealing with management and with customers, created voids for ethical decision-making.

3.2.3. Mechanisms involved in affirming ethics

Companies that successfully leverage ethics find a way to lock it into their culture, promoting and demonstrating coherency between values and behavior. Examples of these opportunities are processes for deploying standards or cultural norms, or for developing and measuring ethical motivation and skills. As we saw with turning points, companies also intentionally create opportunities for transmission of culture (Table 1). For instance, some companies approached renewals of policies or codes—opportunities to introduce ethics—as training processes to strengthen the transmission of ethical standards throughout the organization.

Respect for individual moral autonomy seemed especially important in building a shared ethical mindset and values. Awareness and acceptance of social reality helped companies deal with the diversity and pluralism of their employees. Elements useful in affirming culture allow for shared comprehension of corporate culture and for awareness of the consistency in the application of values across the company (Table 2).

Declarative elements describing culture were used early and often as enablers of transmitting culture in companies. And structural elements, such as formal training procedures, “tone at the top” programs, internal communication channels, and deployment of compliance and ethics responsibilities, were means for transmitting the culture and promoting shared values. These elements were correlated with enhanced awareness and moral capabilities in employees (Warren et al., 2014) and with the development of ethical behavior and practices in organizations (Treviño et al., 2014). Other examples of ways to bolster company values included drawing up organizational charts that reflect values and setting up a foundation to reinforce local community engagement.

Finally, symbolic and structural elements enabled coherency within the companies we examined. Structural elements such as measurement, assessment, reporting, and reward systems to operationalize declarative elements were cited by several companies as influencing awareness of and motivation to practice ethics (Burford et al., 2016; Griffiths et al., 2018) and also in creating an environment that inhibits deviant behavior. Two companies described using “culture buddies” as an orientation method to transfer culture to newer employees, suggesting this could be an example of ethical “contagion”—the idea that exposure to ethical behavior encourages more ethical behavior (Appelbaum et al., 2007).

In cases where ethics failed to take hold, the lack of exemplary leaders—that is, when leadership talked the talk but didn’t walk the walk—inhibited development of a culture of ethics. A lack of balance in the types of cultural elements identified as enablers was another inhibitor for transmitting culture effectively. One company relied heavily on declarative elements and normative elements—mission statements and related slogans, and the beliefs of founders—but did not deploy a balance of structural or symbolic elements to ensure their implementation. The company did not promote a collective learning process to achieve a shared hierarchy of values, and it has suffered from a disconnect similar to Enron (Sims & Brinkmann, 2009). This company is now known for having a strong mission and culture, but not one that encourages ethical behavior.

In startups, survey participants cited as inhibitors pragmatic normative elements—a focus on legal, not ethical considerations—and the influence of having a poor array of cultural elements. For example, they mentioned a lack of formal declarative cultural elements (e.g., mission and values, policies and decision-making criteria); scant symbolic elements (e.g., a lack of ethical sensibility and moral competency in leaders, or few sanctions for behavior that went against stated norms or values); or an absence of structural elements (e.g., channels for participation beyond informal meetings). To test these tendencies would require further studies focusing on a larger number of startups. When affirming values, conditions and cultural elements interact, reinforcing the culture and the consistency with which it is implemented, and thus strengthening the procedures and practices that engender individual and organizational accountability.

4. Toward a culture of ethics: A roadmap

More and more companies are intentionally managing culture as a strategy for organizational ethics. But there are currently few practical tools and approaches to deal with the complexity of fostering cultures in which ethical considerations are a regular part of business discussions and decision-making. The patterns identified in this study show a dynamic relationship among opportunities, conditions, and specific sets of cultural elements, thereby uncovering some of the mechanisms of ethics pervasiveness. Further, these patterns show the importance of using different types of cultural elements to leverage opportunities when conditions are present. An old framework (Gutiérrez Díez, 1996) used for the analysis of cultural elements offered new insights to uncover mechanisms by which ethics is instilled in companies.

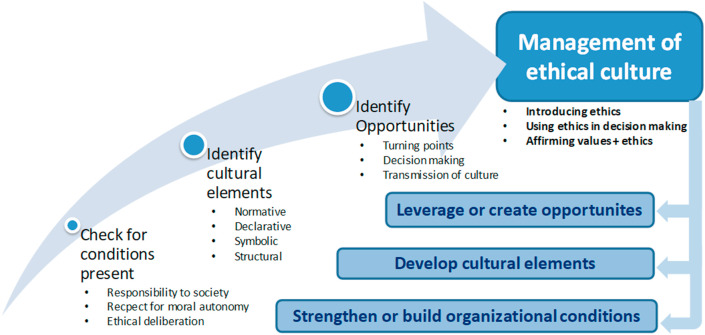

Our evidence-based patterns can help managers encourage ethics in their organizational culture by leveraging foreseeable or even intentionally created opportunities to incorporate ethics (Figure 1 ). The starting point for ethical development within a company is to explore and reflect upon its current culture. The patterns observed in this study support regular culture assessments that include reviewing cultural elements and assessing the presence or absence of conditions that can lead to the introduction, use, and affirmation of ethics. Through these types of assessments, companies can identify conditions and cultural elements worth promoting to encourage ethics. Once the company has acted on its findings to drive cultural change, a reassessment starts the process anew. In this way, culture management becomes a practical, technical skill, measuring outcomes and developing an organization that can learn about itself.

Figure 1.

Manager’s actions using patterns

Ethical aspects

All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and research committees in each location of the study, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study has received no external funds.

Declaration of competing interest

Cecilia Martinez Arellano declares that she has no conflicts of interest. Pedro M. Sasia Santos declares that he has no conflicts of interest. Ann G. Skeet has the following conflicts of interest:

-

•

During the time the research was conducted, a relative of Ann Skeet's worked at one of the companies where the interviews for this study were conducted. The company is a multinational enterprise with over 80,000 employees, and there is no direct connection between him and the people who were interviewed as part of this study.

-

•

The Center for Applied Ethics where Ann Skeet works receives general marketing sponsorship support for business ethics programming that includes events and business ethics internships from some of the companies interviewed, but not support specific to this study. Interns participating in the center’s business internship program worked at one of the companies where the research was conducted.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge the members of the learning community of academics and practitioners focused on business ethics training and research at Directica, the Centre for Applied Ethics at the University of Deusto, and also the companies and businesspeople of the Markkula Center’s business ethics partnership at Santa Clara University that have taken part in this study.

References

- Aguinis H., Glavas A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management. 2012;38(4):932–968. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum S.H., Iaconi G.D., Matousek A. Positive and negative deviant workplace behaviors: Causes, impacts, and solutions. Corporate Governance. 2007;7(5):586–598. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur W. Page Society . 2012. Building belief: A new model for activating corporate character and authentic advocacy.https://knowledge.page.org/report/building-belief-a-new-model-for-activating-corporate-character-and-authentic-advocacy/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Aßländer M., Curbach J. The corporation as citizen? Towards a new understanding of corporate citizenship. Journal of Business Ethics. 2014;120(4):541–554. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen S. Organizational factors encouraging ethical decision making: An exploration into the case of an exemplar. Journal of Business Ethics. 2004;52(4):311–324. [Google Scholar]

- Burford G., Hoover E., Stapleton L., Harder M. An unexpected means of embedding ethics in organizations: Preliminary findings from values-based evaluations. Sustainability. 2016;8(7) [Google Scholar]

- Business Roundtable . 2019, August 19. Business Roundtable redefines the purpose of a corporation to promote ‘an economy that serves all Americans’.https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Dembinski P. The incompleteness of the economy and business: A forceful reminder. Journal of Business Ethics. 2011;100(1):29–40. [Google Scholar]

- DiStaso M. Arthur W. Page Society; 2017, May 22. CCOs on building corporate character: More work to be done.https://page.org/blog/ccos-on-building-corporate-character-more-work-to-be-done Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Dolan S.L., Raich M. The great transformation in business and society: Reflections on current culture and extrapolation for the future. Cross Cultural Management: International Journal. 2009;16(2):121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles R.G., Ioannou I., Serafeim G. The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Management Science. 2014;60(11):2835–2857. [Google Scholar]

- Ethical Systems . 2018. Featured ethics expert and culture architect: Caterina Bulgarella.http://ethicalsystems.org/content/featured-ethics-expert-and-culture-architect-catarina-bulgarella Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Flamholtz E., Randle Y. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 2011. Corporate culture: The ultimate strategic asset. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman R.E. The new story of business: Towards a more responsible capitalism. Business and Society Review. 2017;122(3):449–465. [Google Scholar]

- Garriga E., Melé D. Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. Journal of Business Ethics. 2004;53(1):51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Grandy G., Sliwa M. Contemplative leadership: The possibilities for the ethics of leadership theory and practice. Journal of Business Ethics. 2017;143(3):423–440. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths K., Boyle C., Henning T.F. Beyond the certification badge: How infrastructure sustainability rating tools impact on individual, organizational, and industry practice. Sustainability. 2018;10(4) [Google Scholar]

- Guest G., Bunce A., Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez Díez E.J. Universidade Compultense de Madrid; Madrid, Spain: 1996. Evaluación de la cultura en la organización de instituciones de educación social. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- Haski-Leventhal D., Roza L., Meijs L.C. Congruence in corporate social responsibility: Connecting the identity and behavior of employers and employees. Journal of Business Ethics. 2015;143(1):35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lehnert K., Park Y., Singh N. Research note and review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature: Boundary conditions and extensions. Journal of Business Ethics. 2015;129(1):195–219. [Google Scholar]

- List C., Pettit P. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2011. Group agency: The possibility, design, and status of corporate agents. [Google Scholar]

- Lord R.G., Brown D.J. Leadership, values, and subordinate self-concepts. The Leadership Quarterly. 2001;12(2):133–152. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano J.M. Trotta; Madrid, Spain: 2009. La empresa ciudadana como empresa responsable y sostenible. [Google Scholar]

- NACD . 2017. Culture as a corporate asset.https://www.nacdonline.org/insights/publications.cfm?ItemNumber=48252 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Rick T. Ameliorate; 2015, August 28. Organizational culture is largely invisible.http://www.torbenrick.eu/blog/culture/organizational-culture-is-largely-invisible/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild J. The logic of a cooperative economy and democracy 2.0: Recovering the possibilities for autonomy, creativity, solidarity, and common purpose. The Sociological Quarterly. 2016;57(1):7–35. [Google Scholar]

- Schein E.H. Organizational culture. American Psychologist. 1990;45(2):109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Sims R.R., Brinkmann J. Thoughts and second thoughts about Enron ethics. In: Garsten C., Hernes T., editors. Ethical dilemmas in management. Routledge; Abingdon, UK: 2009. pp. 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Skeet A.G., Guszcza J. 2020, January 7. How business can create an ethical culture in the age of tech. The European Sting.https://europeansting.com/2020/01/07/how-businesses-can-create-an-ethical-culture-in-the-age-of-tech/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Stansbury J. Reasoned moral agreement applying discourse ethics within organizations. Business Ethics Quarterly. 2009;19(1):33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Treviño L.K., Den Nieuwenboer N.A., Kish-Gephart J.J. (Un)ethical behavior in organizations. Annual Review of Psychology. 2014;65:635–660. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren D.E., Gaspar J.P., Laufer W.S. Is formal ethics training merely cosmetic? A study of ethics training and ethical organizational culture. Business Ethics Quarterly. 2014;24(1):85–117. [Google Scholar]

- Watson G.W., Papamarcos S.D., Teague B.T., Bean C. Exploring the dynamics of business values: A self-affirmation perspective. Journal of Business Ethics. 2004;49(4):337–346. [Google Scholar]