Abstract

Worldwide, there is a continued rise in malnutrition and noncommunicable disease, along with rapidly changing dietary patterns, demographics, and climate and persistent economic inequality and instability. These trends have led to a national and global focus on nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions to improve population health. A well-trained public health and community nutrition workforce is critical to manage and contribute to these efforts. The study describes the current public health and community nutrition workforce and factors influencing registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs) to work in these settings and characterizes RDN preparedness, training, and competency in public health and community nutrition. The study was comprised of a cross-sectional, online survey of mostly US RDNs working in public health/community nutrition and semistructured telephone interviews with US-based and global public health and community nutrition experts. RStudio version 1.1.442 was used to manage and descriptively analyze survey data. Thematic analysis was conducted to evaluate expert interviews. Survey participants (n = 316) were primarily women (98%) and White (84%) with the RDN credential (91%) and advanced degrees (65%). Most reported that non-RDNs are performing nutrition-related duties at their organizations. Respondents generally rated themselves as better prepared to perform community nutrition vs public health functions. Interviews were conducted with 7 US-based experts and 5 international experts. Experts reported that non-RDNs often fill nutrition-related positions in public health, and RDNs should more actively pursue emerging public health opportunities. Experts suggested that RDNs are more desirable job candidates if they have advanced public health degrees or prior experience in public health or community nutrition and that dietetic training programs need to more rigorously incorporate public health training and experience. Significant opportunity exists to improve the preparedness and training of the current dietetic workforce to increase capacity and meet emerging needs in public health and community nutrition.

Supplementary materials: Figures 1 and 2 are available at www.jandonline.org.

The field of public health nutrition aims to promote optimal health of populations through the combined application of public health and nutrition principles and methods at the program, system, policy, or environment levels, and community nutrition uses individual- and interpersonal-level interventions focused on knowledge, attitudes, and behavior to improve health outcomes in individuals or small groups in the community setting.1 , 2 Worldwide, the public health and community nutrition workforce must address primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention for a wide range of prevalent, complex health concerns linked to both under- and overnutrition, such as poor maternal and child health, micronutrient deficiencies, obesity, type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases.3, 4, 5

Management of these public health concerns is complicated by rapidly shifting context. Much of the world is experiencing a significant nutrition transition, defined as shifts in diet and physical activity patterns toward those associated with noncommunicable diseases.6 Demographic trends indicate that the proportion of the world population over the age of 60 will double from 11% now to 22% by 2050.7 There is substantial global instability with forced displacement, environmental degradation, climate change, and persistent economic disparities within and across countries threatening to reverse recent public health gains.8 , 9 Health care worker shortages are widespread, especially in rural and underresourced areas.10 The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has highlighted numerous existing challenges related to capacity and preparedness in public health and health care systems worldwide.11 In the United States, it has focused attention on stark racial and ethnic health disparities that are the result of persistent social marginalization, weathering, institutional racism, disproportionate exposure to environmental hazards and economic inequality, disproportionate burden of chronic disease, and barriers to accessing health care.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 The COVID-19 pandemic has also catalyzed an economic crisis that may have catastrophic implications for food security in many parts of the world.18, 19, 20, 21 All of these trends will likely result in increased need for nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions across sectors.22 , 23

Recognition of the need to increase the focus on nutrition is reflected in recent national and global health goals and strategies. For example, the US Agency for International Development launched its Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Strategy for 2014-2025, aiming to increase utilization of high-quality nutrition services and improve country capacity and commitment to nutrition.24 The 2020 Global Nutrition Report emphasized the importance of nutrition as a key component of primary health care.25 The US Healthy People 2020 goals26 and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals27 also emphasize nutrition-related objectives.

A well-trained public health and community nutrition workforce is critical to effectively manage and deliver nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions that address population health goals and objectives. However, little is known about the current capacity and preparedness of registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs) in the public health and community nutrition workforces, in the United States and globally. This study aimed to describe the current workforce in public health and community nutrition settings and factors influencing RDNs to work in these settings and to characterize RDN preparedness, training, and competency in public health and community nutrition. Another objective of this study was to summarize global perspectives on workforce capacity in public health and community nutrition. To that end, the Academy’s Nutrition Research Network worked with a panel of Academy experts and stakeholders to develop and conduct a survey and interviews.

Survey

Study Design

This study used a cross-sectional, anonymous, online survey of primarily US RDNs working in public health nutrition or community nutrition and semistructured telephone interviews with US and global public health and community nutrition experts. The study protocol was approved by the American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided informed consent.

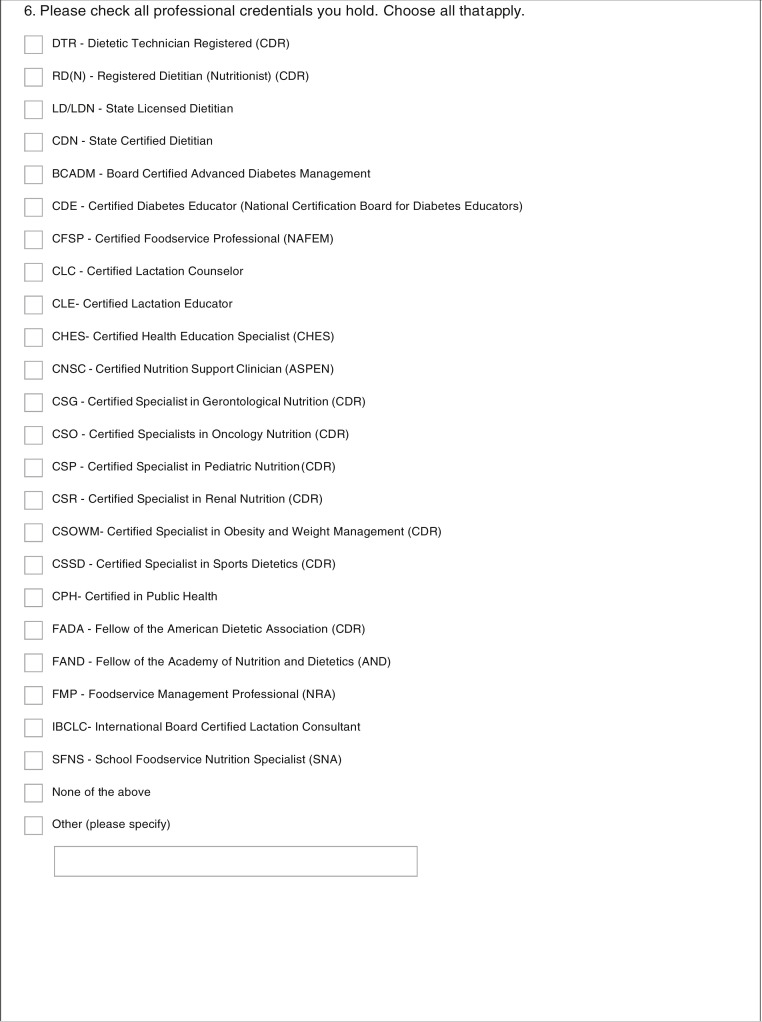

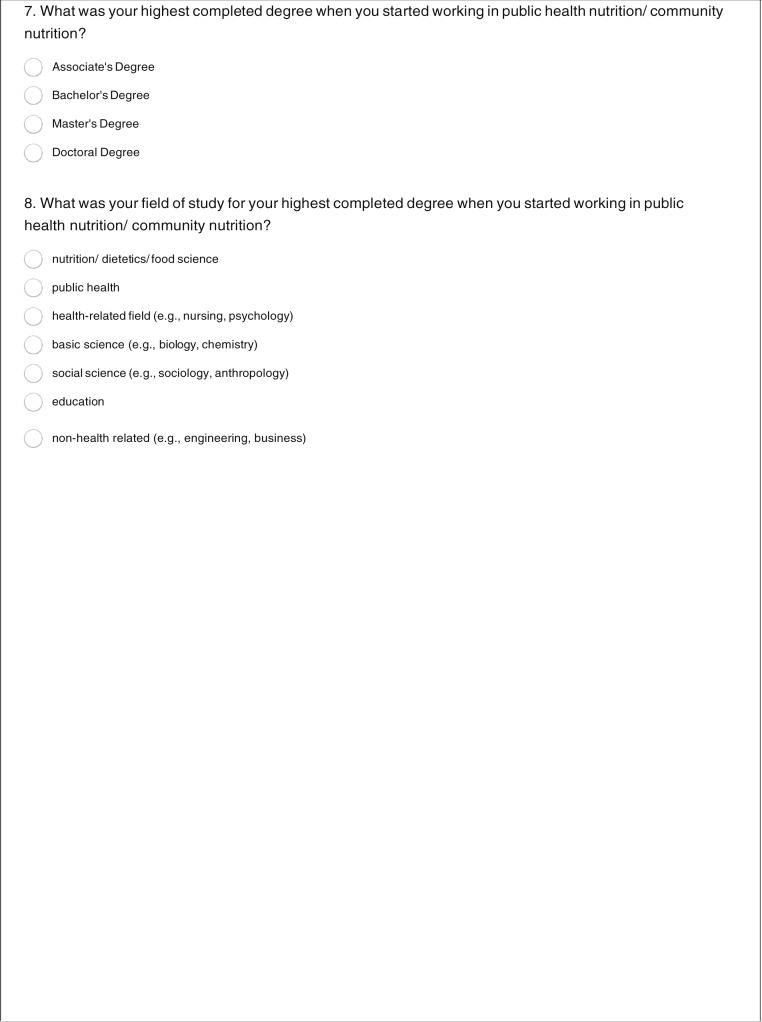

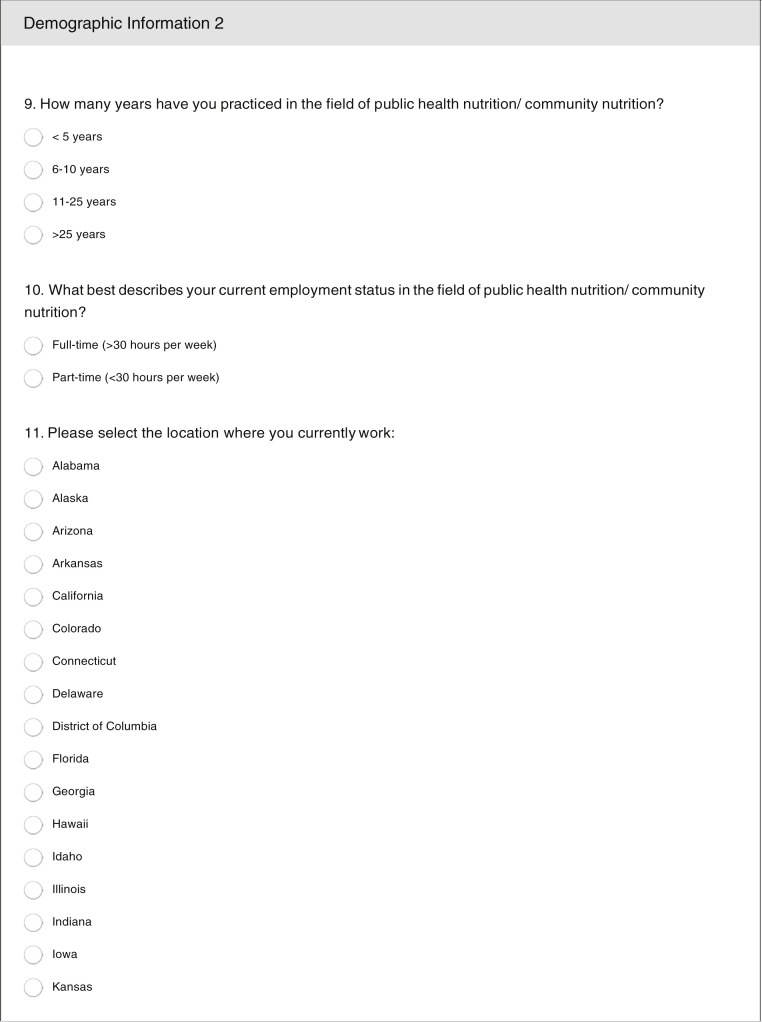

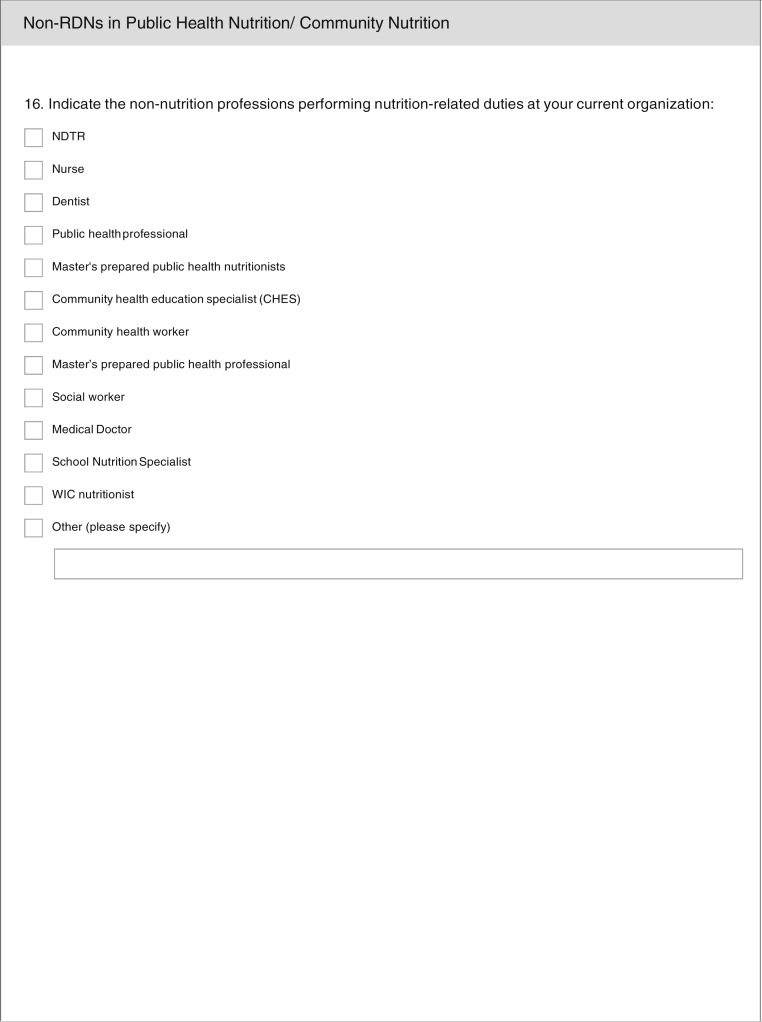

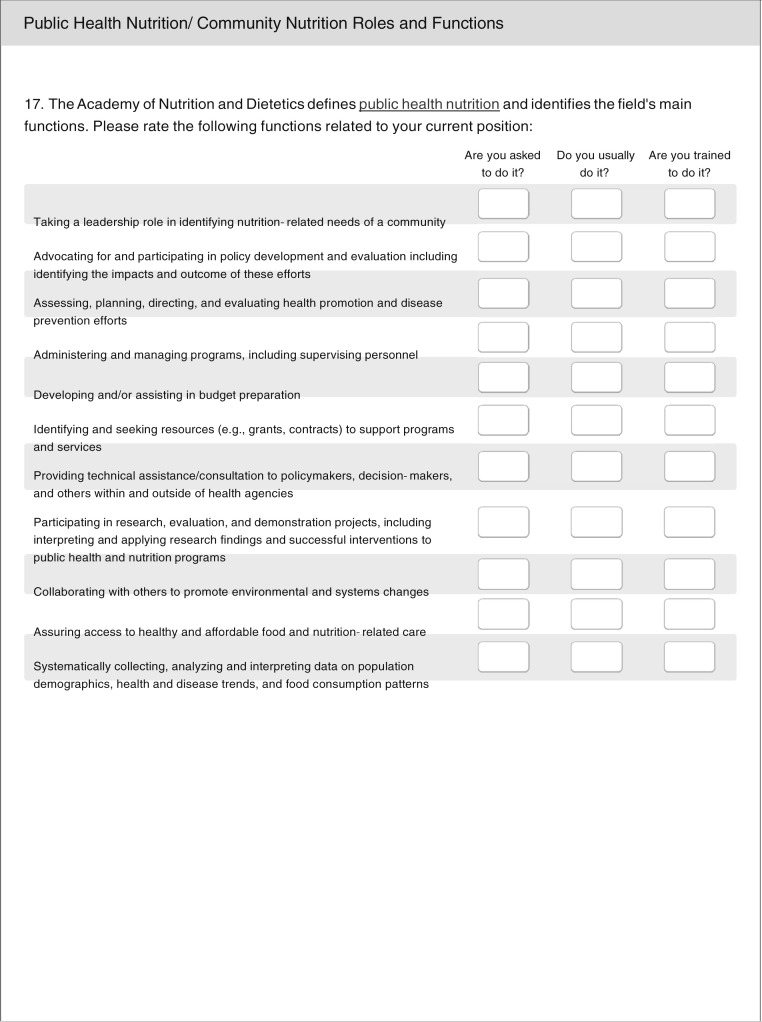

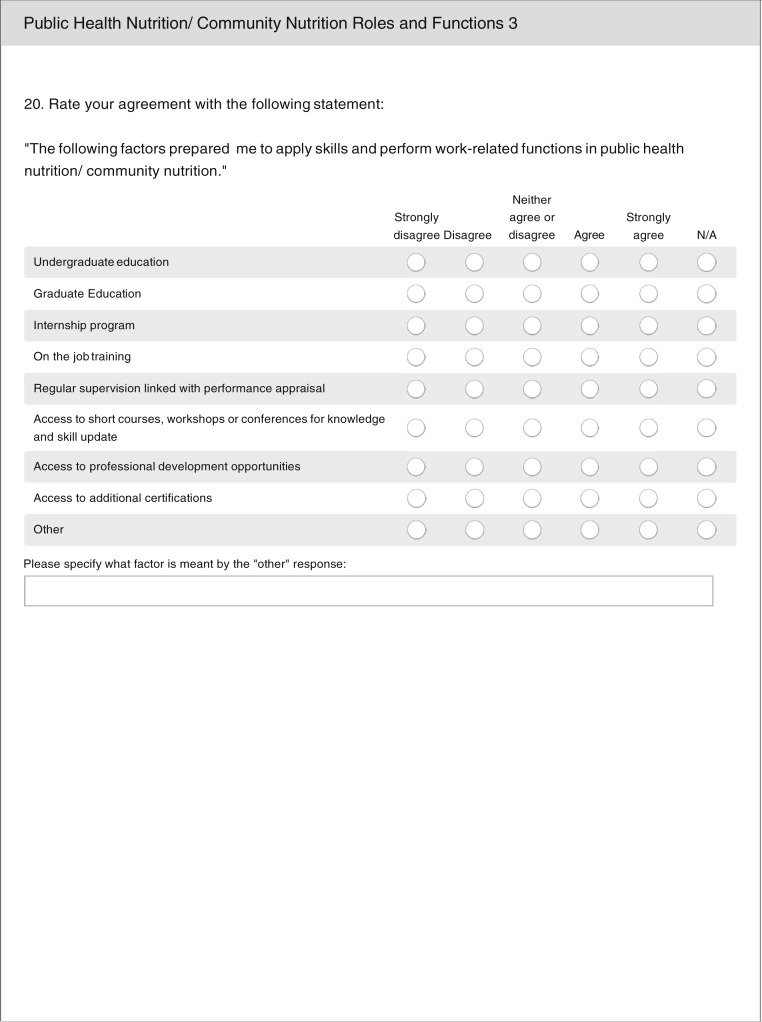

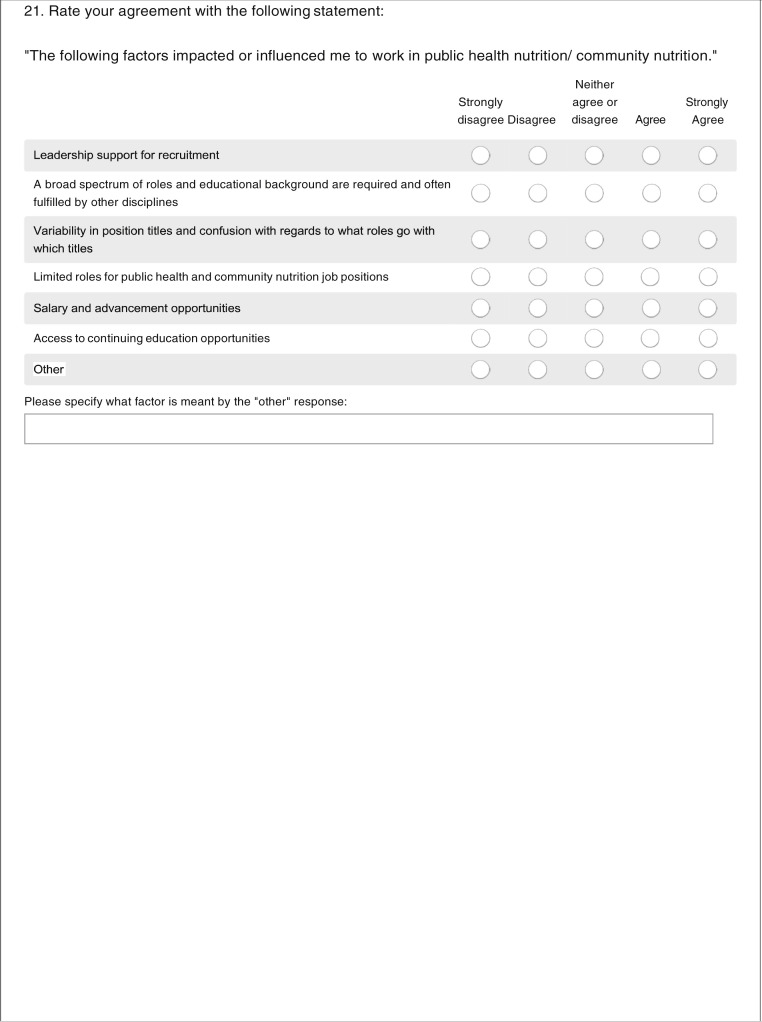

Online Survey Design

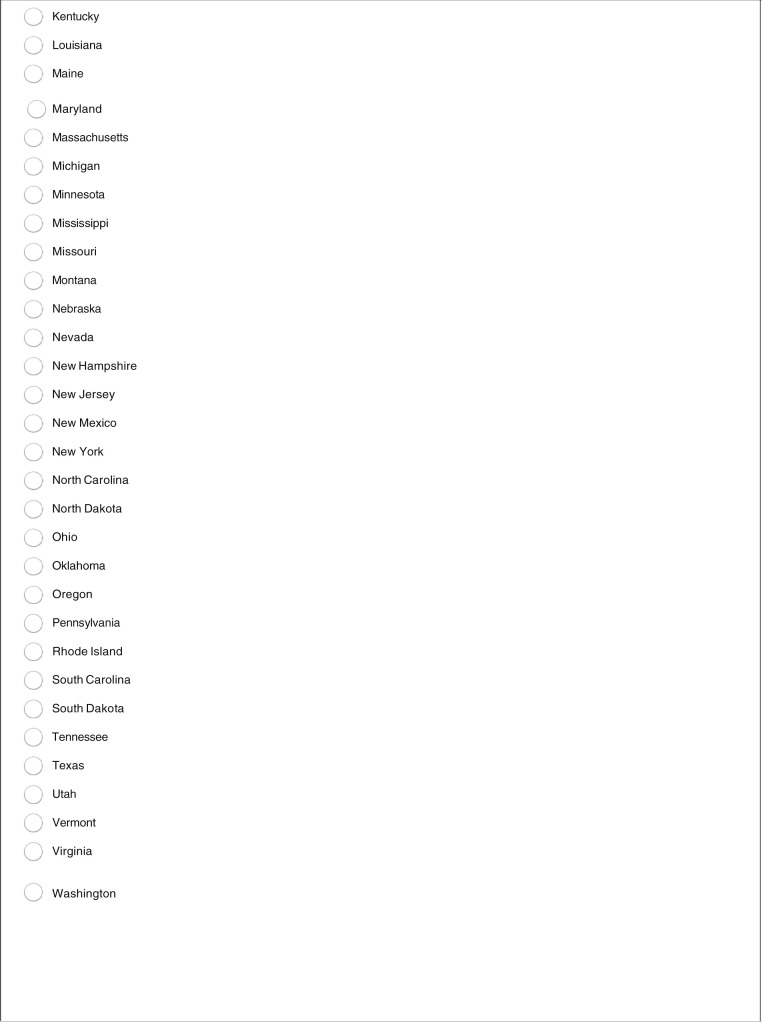

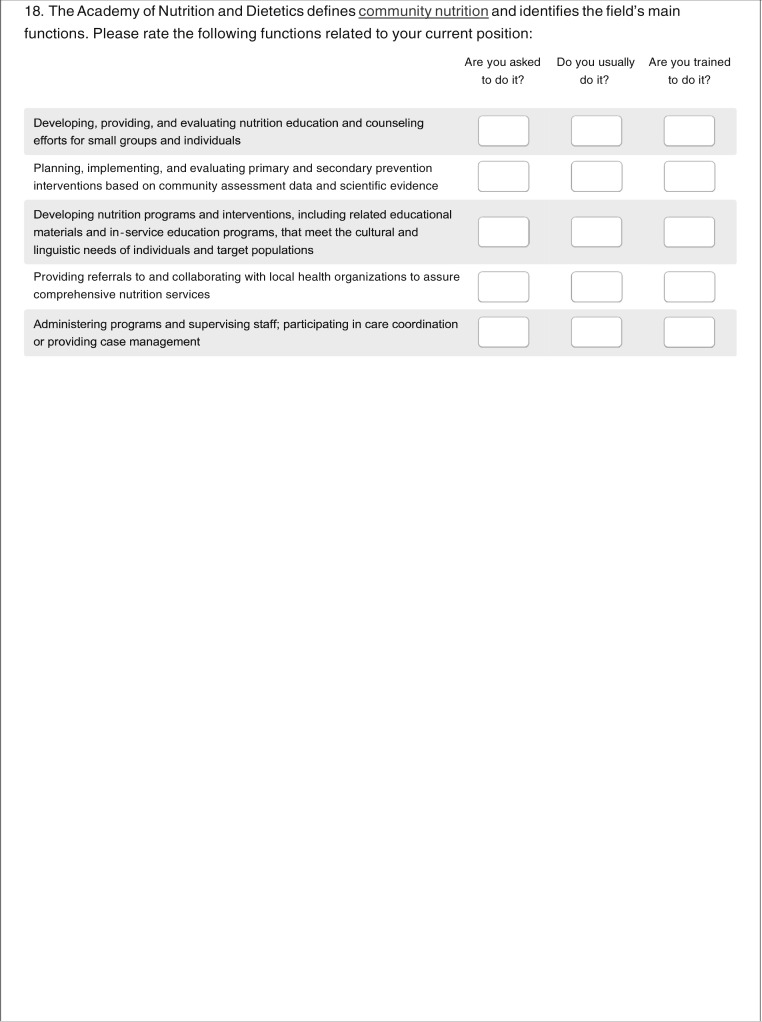

Twenty-two survey questions were developed based on the primary aims of the study by the principal investigator (T.Y.E.-K.) and then jointly reviewed and revised by an advisory panel (including M.B., S.R., J.V., J.Y., and E.Y.J.). The panel included Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (Academy) Dietetic Practice Group and committee leaders with expertise in public health and community nutrition. The survey was written in English and included demographic questions, such as highest completed degree, number of years of experience in the public health or community nutrition field, and educational background and credentials of those performing nutrition-related duties in their employment settings. The survey then asked respondents to rate whether specific factors influenced them to work in the field. These factors included both barriers (ie, a broad spectrum of roles and education background are required and often fulfilled by other disciplines) and facilitators (ie, salary and advancement opportunities). Participants were also asked the extent to which their education and experience prepared them for their current roles. Specifically, they were asked about the contributions of undergraduate education; graduate education; internship programs; on-the-job training; regular supervision and performance appraisal; short courses, workshops, and conferences; professional development opportunities; and additional certifications in preparing them for their current public health or community nutrition position. Participants were also asked to report on public health and community nutrition functions (as defined by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics1) that they are asked to perform, usually perform, or are trained to perform in their current positions and the extent to which they can apply foundational public health skills based on the domains of the Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals28 in performing job functions, self-rating as proficient (highest level of expertise), knowledgeable, aware, or having little to no knowledge (lowest level of expertise). Final survey questions are available in Figure 1 (available at www.jandonline.org).

Figure 1.

Self-rated ability of registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs) working in a paid position in public health nutrition or community nutrition that responded to a cross-sectional, anonymous, online survey to apply the Public Health Core Competencies.

Survey Recruitment

The survey was delivered using SurveyMonkey (SurveyMonkey Inc, San Mateo, CA), an online survey platform. An invitation to participate in the survey was e-mailed to a convenience sample that included members of the Academy’s Hunger and Environmental Nutrition Dietetic Practice Group , Nutrition Education for the Public Dietetic Practice Group, Public Health/Community Nutrition Dietetic Practice Group, and Dietetics Practice Based Research Network (now the Nutrition Research Network), and a 10% random sample of all Academy members, totaling approximately 11,600 potential recipients after duplicates were removed. The DPGs selected for sampling were those that were likely to capture individuals working in public health. The survey was open for 3 weeks from April 21, 2017, to May 12, 2017. A reminder e-mail was sent to all potential participants 2 weeks after the initial invitation.

The survey had a 6% response rate (691 of 11,600 potential respondents). Of the 691 responses, 511 participants were eligible because they indicated that they worked in a paid position in public health nutrition or community nutrition, and 316 completed all survey questions and were included in analyses. All but 3 of the respondents were from the United States. Eligible participants had the option to enter a raffle to receive 1 of 3 $100 American Express gift cards. Raffle entries were kept separate from survey responses to ensure participants’ anonymity.

Survey Analysis

Survey data were managed and descriptively analyzed in RStudio version 1.1.442 (RStudio Team, 2016; http://www.rstudio.com/) and Stata 15 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). Response frequencies were calculated for Likert scale questions. For some analysis, types of education or experience that could prepare individuals for public health nutrition and community nutrition work were recoded to helpful (“strongly agree” and “agree” responses) or not helpful (“neither agree nor disagree,” “disagree,” or “strongly disagree” responses), and self-rated ability to apply foundational public health skills were recoded to group “proficient” and “knowledgeable” ratings compared with “aware” or “having little to no knowledge ratings.” Relationships between whether types of education or experience that could prepare individuals for public health nutrition and community nutrition work were helpful and self-reported perception of being trained to perform public health nutrition and community nutrition functions, and self-rated proficiency in public health competencies, were assessed using χ2 and Fisher exact tests, as appropriate.

Expert Interviews

Semistructured Interview Question Development

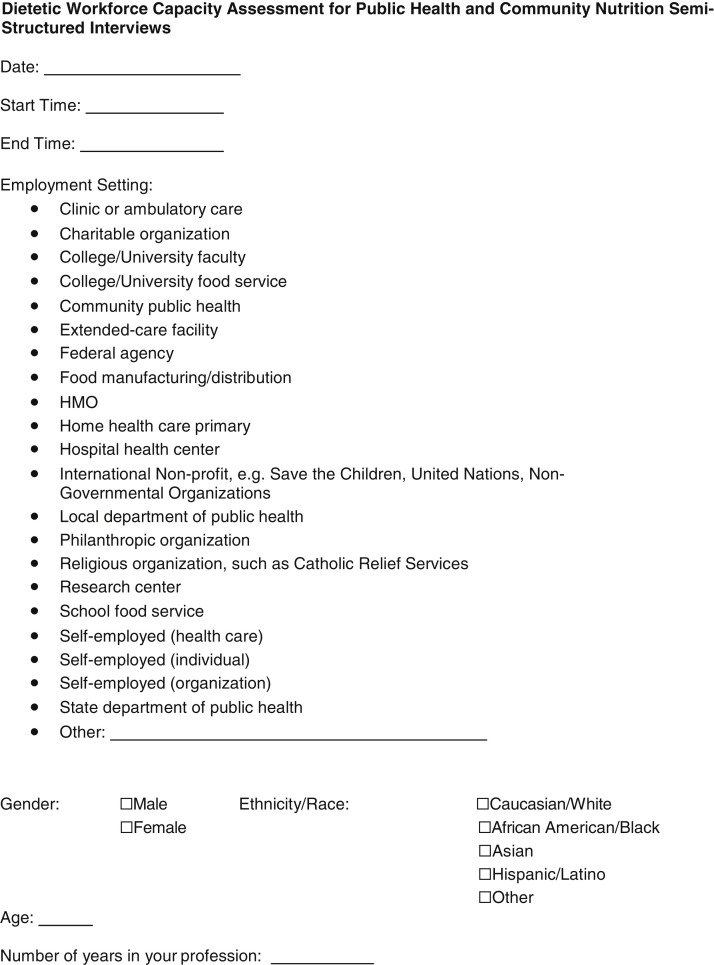

Ten interview questions were developed based upon the primary aims of the study by the principal investigator (T.Y.E.-K.), then jointly reviewed and revised by the advisory panel (including M.B., S.R., J.V., J.Y., and E.Y.J.). The final semistructured interview guide is shown in Figure 2 (available at www.jandonline.org).

Figure 2.

Description of the seven themes and corresponding example quotations from semi-structured phone interviews with U.S. and global public health and community nutrition experts.

Interview Recruitment

Experts are defined as nutrition and dietetics professionals with the highest degree of skill and knowledge in nutrition and dietetics.29 For the purposes of this study, experts were defined as those with a mastery of public health nutrition and/or community nutrition skills or knowledge, which included individuals with or without the RDN credential. Non-RDNs were included in the US context because senior public health and community nutrition positions may be held by non-RDNs. Non-RDNs were included in a global context due to variation in professional credentialing by region. The expert panel identified 28 US-based and 22 global experts in a variety of employment settings. Next, purposive sampling was used to select 10 US-based and 10 global RDNs representing various employment settings. They were recruited for interview participation via e-mail from May 1, 2017, to August 31, 2017. Within 3 weeks of the initial e-mail, reminder e-mails were sent to those who did not respond to the initial invitation. If the recruited RDN did not wish to participate, an alternate RDN was chosen from the equivalent employment setting grouping and asked to participate in the study. Of the 31 experts in public health nutrition or community nutrition contacted, 12 (39%) agreed to participate. Nineteen did not respond.

All interviews were completed by T.Y.E.-K. and K.K. using a standardized script, which was written and administered in English. Approximately 24 hours in advance of the interview, the interviewer e-mailed the interview guide to the participant. Interviews were conducted via telephone for approximately 30 to 60 minutes. Participants were asked the 10 scripted questions. Follow-up probing or clarifying questions were asked as needed. Interviews were audio-recorded and manually transcribed by K.K. and T.Y.E.-K. US-based experts who completed the interview received $50 in compensation and experts outside the United States received an electronic Academy Evidence Analysis Library Toolkit on a topic of their choice.

Thematic Analysis

Thematic analysis was conducted to identify patterns, similarities, and differences between expert experiences and opinions. T.Y.E.-K. and K.K. manually coded US and global interview transcripts independently, identified emergent themes, and then collaborated to create a finalized codebook and themes. Themes were reviewed by E.Y.J.

Findings

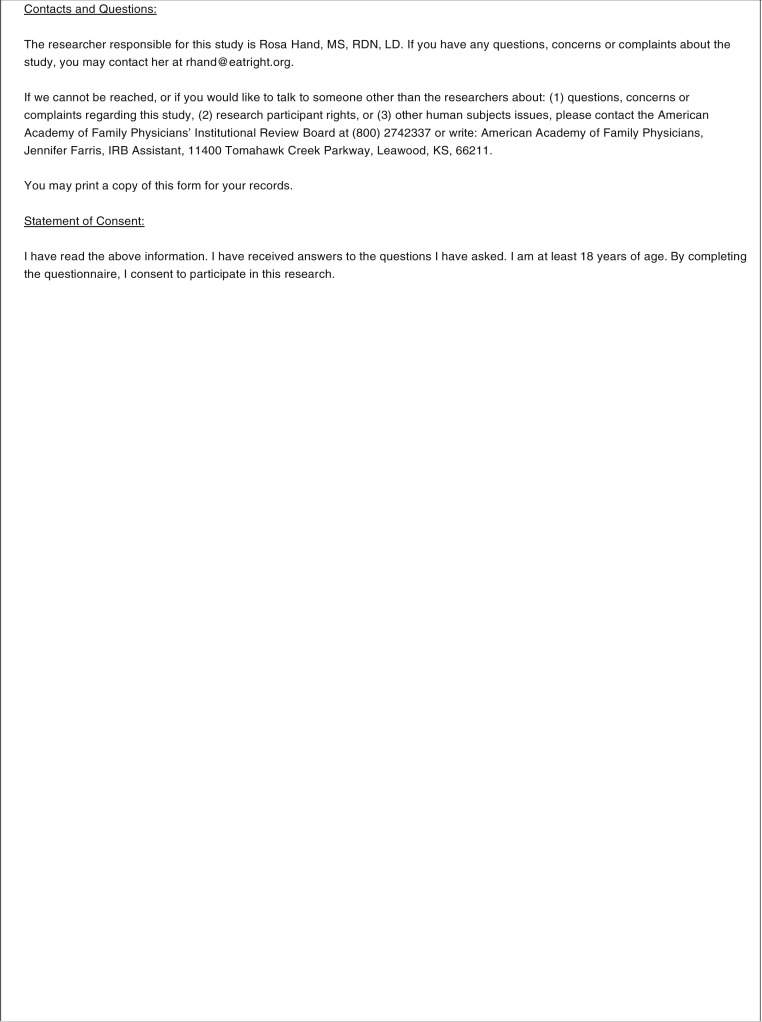

Survey Participant Characteristics

Most survey respondents (n = 316) were women (98%), White (84%), RDNs (91%) working full-time (81%) in public health or community nutrition. Close to two-thirds (65%) of participants had a master’s degree or higher level of education and 56% had 6 or more years of experience in public health or community nutrition. Additional participant characteristics are provided in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs) that responded to a cross-sectional, anonymous, online survey of individuals working in a paid position in public health and community nutrition (n = 316) and U.S. and global public health and community nutrition experts that participated in semi-structured interviews (n = 12)

| Characteristics | Online survey participants, n (%) | Interview participants, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| ←n (%)→ | ||

| Sex | ||

| Female | 308 (97.5) | 11 (91.7) |

| Male | 8 (2.5) | 1 (8.3) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 265 (83.9) | 7 (58.3) |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 16 (5.1) | 2 (16.7) |

| Black or African American | 13 (4.1) | 1 (8.3) |

| Asian | 12 (3.8) | 0 |

| Multiple | 8 (2.5) | 0 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Choose not to answer | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Other | 0 | 2 (16.7) |

| Highest degree completed | ||

| Currently a student | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Associate’s | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Baccalaureate | 110 (34.8) | 0 |

| Master’s | 183 (57.9) | 7 (58.3) |

| Doctorate | 20 (6.3) | 4 (33.3) |

| Professional (eg, MD, JD) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (8.3) |

| Employment status | ||

| Full-time (≥30 h/wk) | 256 (81.0) | 12 (100.0) |

| Part-time (<30 h/wk) | 60 (19.0) | 0 |

| Years of practice in public health nutrition/community nutrition | ||

| <5 | 140 (44.3) | 0 |

| 6-10 | 58 (18.4) | 1 (8.3) |

| 11-25 | 72 (22.8) | 6 (50.0) |

| >25 | 46 (14.6) | 5 (41.7) |

| Academy membership status | ||

| Member | 305 (96.5) | 7 (58.3) |

| Nonmember | 11 (3.5) | 5 (41.7) |

| RDNacredential status | ||

| Has RDN credential | 288 (91.1) | 7 (58.3) |

| Does not have RDN credential | 28 (8.9) | 5 (41.7) |

| Employment setting | ||

| Community public health | 42 (13.3) | 0 |

| Local department of public health | 37 (11.7) | 0 |

| State department of public health | 31 (9.8) | 0 |

| College/university faculty | 26 (8.2) | 5 (41.7) |

| Clinic or ambulatory care | 21 (6.6) | 0 |

| Hospital health center | 19 (6.0) | 0 |

| Charitable organization | 16 (5.1) | 0 |

| School food service | 16 (5.1) | 0 |

| Self-employed (individual) | 11 (3.5) | 4 (33.3) |

| Federal agency | 9 (2.8) | 1 (8.3) |

| Otherb | 88 (27.8) | 4 (33.3) |

RDN = registered dietitian nutritionist.

Other employment settings include government settings (outside of public health departments), domestic nonprofits, extended-care facilities, research centers, self-employed (organizations), college/university food service, health maintenance organizations, home health care primaries, international nonprofits, religious organizations, and self-employed (health care).

Survey Results

Most participants (62%) reported that the RDN credential was a required qualification for their current positions. However, about the same percentage of respondents (64%) also reported that non-RDNs, such as public health professionals (34%), Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children nutritionists (29%), nurses (26%), and community health workers (21%), are performing nutrition-related duties in their employment settings. Many participants also reported that colleagues with bachelor’s degrees in nutrition, dietetics, or other health-related fields are performing nutrition-related duties in public health and community nutrition employment settings. Several participants commented in a final, free-text question that many individuals working in public health and community nutrition do not pursue the RDN credential because it is too expensive, time-intensive, and/or clinically focused.

Participants were asked to self-report the degree to which 6 factors impacted their decision to work in public health nutrition or community nutrition (Table 2 ). The barrier with the highest reported impact was that a broad spectrum of roles and educational backgrounds are required and often fulfilled by other disciplines. Many participants also reported that an “other” factor positively impacted their decision to work in the field; most often, this “other” factor was a passion for public health or community nutrition. Additional factors cited in the “other” category included an interest in helping underserved populations, an ability to have an impact on health at the population level, and an interest in prevention. A few participants mentioned that job flexibility positively impacted them to work in the field. Many commented that salaries in the public health and community nutrition field are generally low, but this was not a strong deterrent.

Table 2.

Self-reported agreement with factorsthat impacted registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs) that responded to a cross-sectional, anonymous, online survey to work in the public health and community nutrition field

| Factors | n | Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ←n (%)→ | ||||||

| Barriers | ||||||

| Limited roles for public health and community nutrition job positions | 316 | 22 (6.9) | 66 (20.8) | 93 (29.3) | 94 (29.7) | 41 (12.9) |

| Variability in position titles and confusion with regards to what roles go with which titles | 316 | 19 (6.0) | 59 (18.6) | 126 (39.8) | 73 (23.0) | 39 (12.3) |

| A broad spectrum of roles and educational background required and often fulfilled by other disciplines | 316 | 45 (14.2) | 122 (38.5) | 86 (27.1) | 45 (14.2) | 18 (5.7) |

| Facilitators | ||||||

| Salary and advancement opportunities | 316 | 25 (7.9) | 71 (22.4) | 98 (30.9) | 92 (29.0) | 30 (9.5) |

| Leadership support for recruitment | 316 | 26 (8.2) | 83 (26.2) | 123 (38.8) | 58 (18.3) | 26 (8.2) |

| Access to continuing education opportunities | 316 | 30 (9.5) | 111 (35.0) | 93 (29.3) | 64 (20.2) | 18 (5.7) |

aSome respondents (n = 111) wrote in free-text responses to describe other factors that were not listed. These responses most commonly included a passion for public health and community nutrition as a facilitator affecting their decision to work in the field.

Respondents were asked to assess the extent to which 8 factors related to education or experience prepared them to apply skills and perform work-related functions in public health nutrition and/or community nutrition. The majority of participants agreed or strongly agreed that all of the 8 factors prepared them: on-the-job training (92% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed); graduate education (among those with graduate degrees; 88%); access to professional development opportunities (88%); access to short courses, workshops, and conferences (88%); internship programs (80%); undergraduate education (73%); regular supervision linked with performance appraisal (62%), and access to additional certifications (61%). Thirty-nine participants reported that other factors prepared them, including past work experience as an RDN, networking with others in the field, and mentorship (being a mentor or a mentee).

Participants were asked to indicate if they are asked to perform or usually perform or are trained to perform 11 public health nutrition functions (Table 3 ) and 5 community nutrition functions (Table 4 ) in their current positions. On average, a higher percentage of respondents reported that they are trained to perform the 5 community nutrition functions (77%) than the 11 public health nutrition functions (63%). Correspondingly, on average, more respondents usually perform community nutrition functions (64%) than public health nutrition functions (57%) in their current positions.

Table 3.

Public health nutrition functions that registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs) that responded to a cross-sectional, anonymous, online survey are asked to perform, usually perform, or are trained to perform in their current public health nutrition or community nutrition positions (n = 316)

| Public health nutrition function | Are you asked to do it? | Do you usually do it? | Are you trained to do it? |

|---|---|---|---|

| ←n (%)→ | |||

|

216 (68.4) | 229 (72.4) | 241 (76.3) |

|

212 (67.1) | 223 (70.6) | 241 (76.3) |

|

207 (65.5) | 218 (69.0) | 233 (73.7) |

|

213 (67.4) | 217 (68.6) | 220 (69.6) |

|

193 (61.1) | 197 (62.3) | 210 (66.5) |

|

168 (53.2) | 187 (59.2) | 188 (59.5) |

|

142 (44.9) | 155 (49.1) | 196 (62.0) |

|

128 (40.5) | 141 (44.6) | 196 (62.0) |

|

145 (45.9) | 147 (46.5) | 167 (52.8) |

|

153 (48.4) | 140 (44.3) | 146 (46.2) |

|

116 (36.7) | 133 (42.1) | 136 (43.0) |

Table 4.

Community nutrition functions that registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs) that responded to a cross-sectional, anonymous, online survey are asked to perform, usually perform, or are trained to perform in their current public health nutrition or community nutrition positions (n = 316)

| Community nutrition function | Are you asked to do it? | Do you usually do it? | Are you trained to do it? |

|---|---|---|---|

| ←n (%)→ | |||

|

248 (78.5) | 240 (75.9) | 286 (90.5) |

|

181 (57.3) | 182 (57.6) | 234 (74.1) |

|

241 (76.3) | 243 (76.9) | 271 (85.8) |

|

193 (61.1) | 200 (63.3) | 244 (77.2) |

|

141 (44.6) | 140 (44.3) | 183 (57.9) |

Some relationships between respondents indicated that a factor related to education or experience was helpful in preparing them to work in public health or community nutrition, and respondents indicated that they were trained to perform some community nutrition or public health nutrition functions. This was most frequently observed for graduate education, with individuals that reported that their graduate education helped to prepare them more likely to report that they were trained in several public health nutrition functions related to food and nutrition care access (82% trained if graduate education prepared them vs 48% trained if graduate education did not prepare them; P < .001); taking on leadership roles (86% vs 44%; P < .001); policy development and evaluation (70% vs 30%; P < .001); health promotion and disease prevention (81% vs 63%; P = .03); program management and administration (71% vs 48%; P = .02); research, evaluation, and demonstration projects (76% vs 42%; P = .002); using population-level data (71% vs 37%; P < .001); and the community nutrition function related to prevention interventions (83% vs 59%; P = .004). Respondents who indicated that their internship helped to prepare them were more likely to report that they were trained in public health nutrition functions related to taking on a leadership role (79% vs 63%; P = .008), food and nutrition care access (78% vs 61%; P = .007), and using population-level data (66% vs 48%; P = .02), and the community nutrition function related to referral and collaboration with local health organizations (80% vs 64%; P = .01).

Individuals that reported that their undergraduate education helped to prepare them were more likely to report that they were trained in the public health nutrition function related to food and nutrition care access (79% vs 67%; P = .03) and the community nutrition functions related to nutrition education and counseling (93% vs 84%; P = .01) and referral and collaboration with local health organizations (80% vs 70%; P = .05). Individuals who felt that on-the-job training prepared them were more likely to report that they were trained in the public health function of taking on a leadership role (78% vs 58%; P = .03). Those who felt that short courses, workshops and conferences were helpful were more likely to report that they were trained in the public health function of budget preparation (62% vs 45%; P = .05). Those who felt access to additional certifications were helpful were more likely to report that they were trained in the community nutrition functions of nutrition education and counseling (93% vs 85%; P = .04) and referral and collaboration with local health organizations (82% vs 71%; P = .03). There were no significant relationships between other types of preparation and self-perceptions of being trained for specific public health nutrition and community nutrition functions.

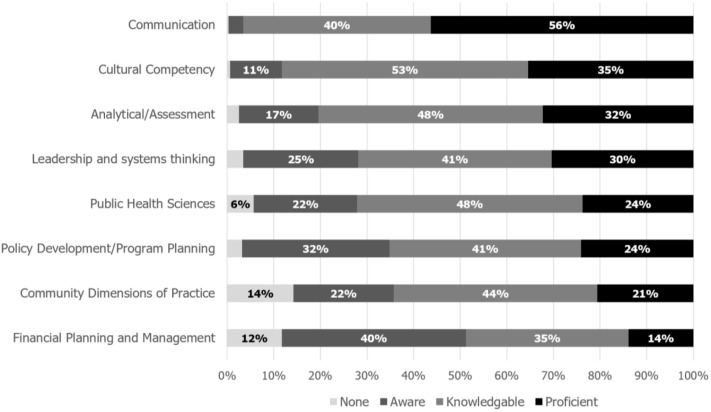

Regarding application of foundational public health skills in their current job functions (Figure 3 ), participants rated their ability to apply communication skills the strongest, with almost everyone rating themselves as either proficient (56%) or knowledgeable (40%). The majority also rated themselves as proficient or knowledgeable in cultural competency (35% proficient and 53% knowledgeable) and analytical/assessment skills (32% proficient and 48% knowledgeable). Participants reported that they were the least knowledgeable in financial planning and management, with 52% stating that they had either limited or no knowledge of the skill. There were some relationships between reporting that a factor related to education or experience had prepared them and their self-reported ability to apply public health skills. Respondents were more likely to report that they were knowledgeable or proficient in leadership and systems thinking if regular supervision linked with performance appraisal had prepared them (78% knowledgeable or proficient) vs not prepared them (66%; P = .02). Similar associations were noted between graduate education and policy development and program planning skills (75% knowledgeable or proficient if it was a factor vs 56% if it was not, respectively; P = .05) and public health sciences (79% vs 63%; P = .04). Almost all (98%) of respondents that felt the internship had prepared them indicated that they were knowledgeable or proficient in communication, compared with 88% of those that did not feel prepared by the internship (P = .002). There were no significant relationships between other types of preparation and levels of self-reported proficiency in public health skills.

Figure 3.

Survey participants’ self-rated ability to apply the Public Health Core Competencies.28

Expert Interview Participant Characteristics

Semistructured interviews were conducted with 7 US-based experts and 5 global experts. Of the 7 US-based experts, 2 were college/university faculty, 2 worked for nonprofit organizations, 1 was self-employed as a consultant, 1 was employed by a federal agency, and 1 was employed by a nonprofit organization and self-employed as a consultant. Among the global experts, 2 were employed by colleges/universities as well as international nongovernmental organizations, 1 was college/university faculty, 1 was employed by a nonprofit organization, and 1 was self-employed as a consultant. Global experts had public health and/or community nutrition experience in countries including Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Venezuela, Ethiopia, and Senegal. Additional details about interview participant characteristics are provided in Table 1.

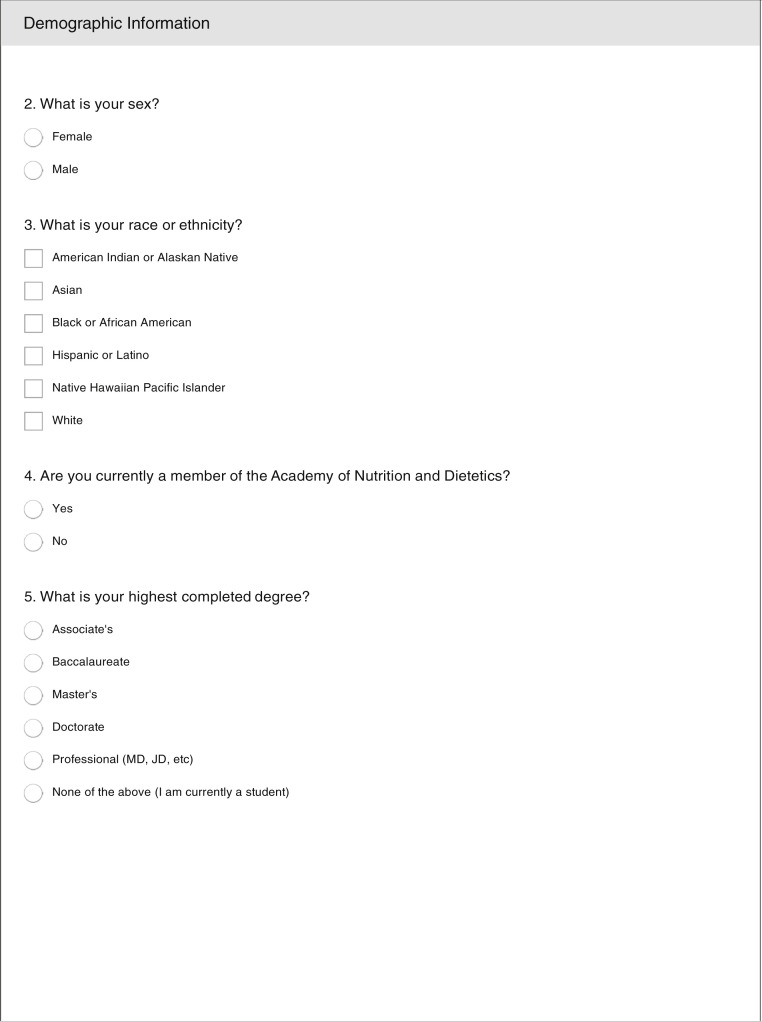

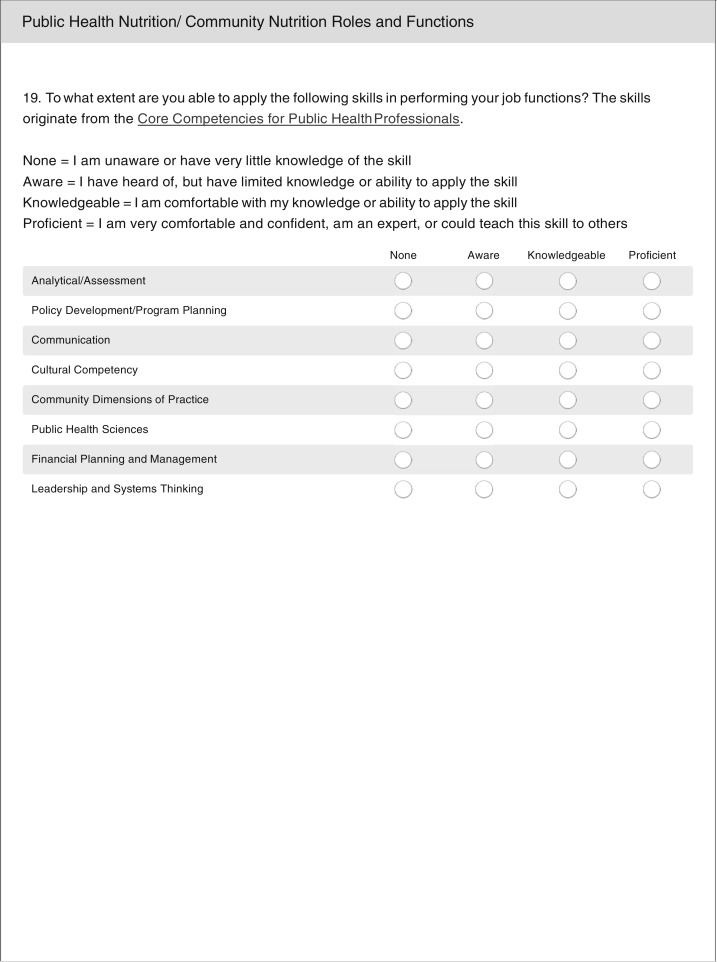

Expert Interview Results

Thematic analysis of the interviews revealed several themes that applied to both global and US-based interviews. Themes and example quotes are listed in Figure 4 .

Figure 4.

Description of the 7 themes and corresponding example quotations from global and US-based expert interviews.

| Theme description | Theme summary | Example quotation(s) |

|---|---|---|

| RDNs have significant capacity to have roles in public health and community nutrition fields. | RDNs should have roles in both clinical and public health and community nutrition settings. | “When there’s so much nutrition information out there and so many people who [aren’t] experts, RD(N)s can cut through the clutter and really . . . bring a very credible voice to the [public health nutrition] space.” (US-based expert) “We need to address public health in a multidisciplinary way. . . . For having that holistic view, you have to include several professionals and definitely dietitians should be one of those.” (Global expert) |

| The skill sets required to work in public health nutrition and/or community nutrition extend beyond current RDN training and education. | Many of the skills required to succeed in public health and community nutrition extend, in some cases, beyond those typically acquired in current RDN education and training. Specifically, participants mentioned these additional skills: knowledge of biostatistics and epidemiology, data analysis, awareness of social determinants of health, understanding community needs, grant writing, budget and resource management, personnel management, and in some cases, speaking multiple languages. Currently, public health professionals are generally more prepared to perform this broad range of skills than the RDN. | “We would rather hire somebody without the RDN that has population-based skills than hire somebody with the RDN that doesn’t understand population health.” (US-based expert) “We are living in a very difficult time in [my country], and . . . how to make decisions of what to do with those resources, it’s very hard sometimes.” (Global expert) |

| The current education model for RDNs needs increased emphasis on public health and community nutrition for RDNs to enter this area of practice. | Nutrition and dietetics programs should increase emphasis on public health and community nutrition. US-based experts suggested that the Academy has a role in catalyzing this change in several ways: by developing relationships with public health nutrition organizations and by rethinking the current RDN education and training model in terms of the public health experience. One participant believed that the existing dietetics programs in the United States adequately prepare dietitians to work in community nutrition by fostering individual and small-group counseling skills but noted that public health nutrition skills are not rigorously cultivated. | “In terms of public health nutrition—that’s the field I know best—health departments really struggle to get people with the combination of the strong nutrition training and the public health training.” (US-based expert) “In our public health nutrition graduate program, probably about a quarter to maybe a third of our faculty are RDNs. That is a preference, but it’s hard to find people with public health nutrition-specific training and the RDN [credential] at the doctoral level.” (US-based expert) |

| Advanced degrees, and specifically the MPH degree, are desirable qualifications for public health and community nutrition positions. | Many experts, both in the United States and globally, emphasized the value of advanced degrees in obtaining their current roles in their organizations and preparing them for their work in public health nutrition. Several experts commented that their organizations hire for public health nutrition positions based on public health degrees and not the RDN credential. One participant commented that she had no formal training in public health nutrition; instead, she fostered her public health skills by learning from colleagues on the job. However, this experience was the exception rather than the rule among the interviewed experts. | “We would only hire an RDN . . . if they already had an MPH degree. We generally don’t hire people with an MS degree because we don’t need the science; we need the population-specific skills.” (US-based expert) |

| Field experience, public health internships, and diverse prior work experience prepare experts to work in public health and community nutrition. | Experts stated that their field experience and public health internships prepared them for their current positions in public health nutrition or community nutrition. Pursuing internship opportunities related to public health nutrition allowed them to foster public health skills, and these opportunities even encouraged some participants to pursue additional education related to public health. | “I obtained my master’s and then my PhD, but I did do a couple of internships. Even in my undergraduate years, I worked as a research assistant in Lebanon, and then during my master’s I did [an] internship in Senegal. I also worked for a couple of months here in Washington for a global nutrition consultancy. . . . If I didn’t have those experiences, I don’t know if I would’ve been such an attractive candidate for my current position [at an international nonprofit organization].” (Global expert) |

| Employers and RDNs currently working in public health and community nutrition should come together to identify ways to recruit more RDNs into these settings. | Several experts suggested that collaboration among RDNs and key players in public health and community nutrition will support more RDNs moving into these settings. For example, one expert suggested that federal agencies in the United States need to convene around this issue. Another suggested that RDNs in public health nutrition could advocate for other RDNs entering the field. | “I wonder if there’s some strength in bringing together [RDNs] that are already in public health . . . to dialogue about what they can do in their jobs and helping. Maybe there’s some tools they need, some education, some mentoring, to feel like they can do more promotion of that in their workplaces.” (US-based expert) |

| Non-RDNs, specifically, public health professionals, are filling nutrition-related positions in public health and community nutrition, and RDNs need to actively seek out emerging and high-profile opportunities in these fields. | RDNs need to seek out positions in public health nutrition and community nutrition, and especially in emerging and high-profile areas, more assertively. | “I see a lot of people that are passionate about food, passionate about gardening, passionate about good eating and stuff like that, that are in schools or in communities, none of [whom] have a background in nutrition. They’re great communicators, they’re great promoters . . . but they’re not [RDNs]. And it’s not because those jobs are reserved, it’s just that I don’t think [RDNs] think out of the box.” (US-based expert) “Currently, we know that people—not necessarily with nutrition degrees—are making decisions about nutrition in ministries, agriculture . . . UNICEF, or public health offices.” (Global expert) “We have a lot of opportunities to impact the public’s health through different types of public health and community-based programs, especially with the trend in wellness. So, we need to be aggressive in positioning ourselves in some of these places, in doing the work, in doing it well, and in being highly visible.” (US-based expert) |

MPH = Master of Public Health; RDN = registered dietitian nutritionist; UNICEF = The United Nations Children’s Fund.

Implications

RDNs have significant capacity to bring valuable expertise and transferable skills to multidisciplinary teams addressing public health nutrition and community nutrition issues,30 but based on the opinions of the experts that were interviewed for this study, public health nutrition education and training programs for RDNs are currently perceived to be inadequate in the United States and globally, with disparities in geographic capacity, preparedness, and leadership. Based on the survey conducted as part of this study, US RDNs who are currently working in the field reported that their skill sets were primarily gained through on-the-job training, graduate degrees, and professional development. In some cases, when a wider variety of education and experience options were rated by the RDN as helpful, they were associated with more frequently feeling trained and proficient in certain public health and community nutrition skills and competencies, indicating that in some cases the relevance of the content is likely as important as modality and timing. Overall, US RDNs that participated in the survey are most comfortable with utilizing skills that overlap substantially with current dietetics training (eg, communication, cultural competency, and assessment), and less comfortable with skills that are potentially integral to taking on leadership roles in public health (eg, policy development/program planning, community dimension of practice, and financial planning and management). As a result of addressable gaps in education and training, too few nutrition professionals with the appropriate public health skill set are likely available to respond to increasing public health and community nutrition market needs, domestically and globally.31 Based on the results of both the survey and the interviews, public health and community nutrition positions are currently being filled by other professionals, and particularly by public health professionals. This reflects findings from other assessments of the dietetic workforce in the United States, with just 9% of RDNs responding to the Academy’s 2019 Compensation and Benefits Survey report that the practice area of their primary position is community nutrition, encompassing RDNs working in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children, public health, cooperative extension, and school, childcare, and food bank and assistance program settings.32

Implications for Practice

Capacity-building education and training must be implemented with institutional support to be effectively sustained.33 Therefore, the Academy has an important role in advocating for RDNs to enter the public health nutrition and community nutrition workforce. Although public health nutrition workforce competency expectations vary by employment setting,34 public health and community nutrition workforce capacity development should begin with dietetics training and education. Although several individual academic programs in the United States offer domestic and overseas internship experiences and programs in the areas of public health and community nutrition, the Academy can consider adjusting educational and internship requirements to promote a comprehensive focus on important aspects of domestic and global public health and community nutrition for all programs. The Didactic Program in Dietetics curricula should be reviewed and updated to increase focus on building RDN competency in key public health skills and exposing RDNs to important domestic and global public health nutrition concepts, such as social determinants of health, institutionalized racism and related health inequities, population-level prevention and interventions, protracted crises, and emergency nutrition. Recently, the Academy released population-level nutrition intervention terms as a part of the electronic Nutrition Care Process Terminology. In addition to providing standardized terminology to practitioners, this can facilitate exposure to population-level concepts during dietetics education.35 The Commission on Dietetic Registration may consider reviewing and increasing the proportion of RDN examination questions related to public health nutrition and community nutrition to drive more focus in this area of practice. Employers’ perception of the value of RDNs in public health settings may improve if population-level skills are introduced as a standard, substantive component of curricula for prospective RDNs.

The new initiative to increase the minimum degree requirement for RDN registration eligibility from a baccalaureate to a graduate degree in January 202436 may have a positive impact on workforce capacity in public health and community nutrition due to an expected increase in practitioners with more advanced skill sets. However, some online survey respondents reported that the existing requirements to become an RDN are already too time-intensive and costly without the addition of the graduate degree requirement, necessitating careful monitoring of the impact that the new requirement has on the percentage of RDNs working in public health and community nutrition and on the racial and ethnic diversity of the RDN workforce, as this has important implications for providing and promoting equitable care37 and health outcomes. If the new minimum degree requirement has adverse effects, the Academy needs to actively consider increasing access to the profession via alternative pathways.

The Academy can also offer additional opportunities for RDNs to expand their public health and community nutrition skill set through professional development, particularly for emerging areas. One initiative in this area is the Academy Foundation’s efforts to offer fellowship opportunities that aim to improve fellow expertise and networking opportunities while addressing domestic and global public health and community nutrition challenges. The Academy’s Foundation provides details about the fellowship model, as well as current and past fellows’ projects via their website: https://eatrightfoundation.org/scholarships-funding/fellowships/.

Another role for the Academy is continued support of the Public Health/Community Nutrition Practice Group, which develops professional development tools and resources for current RDNs, such as the Public Health Nutrition Certificate of Training program and the Guide for Developing and Enhancing Skills in Public Health and Community Nutrition, which was developed in collaboration with the Association of State Public Health Nutritionists and is available in 3 different versions for practitioners, employers and administrators, and educators and preceptors.38 RDNs can also utilize the Academy’s Standards of Practice and Standards of Professional Practice, which aim to help public health and community nutrition RDNs assess their skills and identify opportunities for professional development.3 Member engagement in the Academy’s mentoring program with professionals working in public health and community settings is essential to support public health nutrition competency and workforce development.39 The Academy’s continued support of leadership development opportunities for RDNs in public health and community nutrition is also important,40 as leaders and agents of change were identified as a key enabler of public health workforce development in a qualitative study conducted across 7 European countries.41 Additionally, fostering active collaborations with Academy Member Interest Groups and organizations such as Diversify Dietetics42 is important to strengthen Academy resources and initiatives related to health equity, racial and ethnic diversity of the RDN workforce in all practice settings, and cultural competence and humility.43 Interviewees also suggested that the Academy work to establish or expand relationships with other key organizations in public health, such as the American Public Health Association, the Association of State Public Health Nutritionists, the World Health Organization, and the World Federation of Public Health Associations, and consider public health nutrition perspectives and complexity when establishing policy positions and making public statements.

Finally, it is necessary for the Academy to support efforts to estimate the supply and demand for public health and community nutrition professionals within public health and other related sectors, to create the business case for improving the capacity to train more individuals in this practice area, domestically and globally, and to identify key areas where additional training options and capacity building are necessary. Additional data are needed to establish robust profiles of the public health and community nutrition workforces in the United States at the national and state levels and at the country level worldwide. Global estimates that do exist are in some cases outdated and have been conducted for very few countries, such as Indonesia44 and Canada.45 Ideally, these types of data about public health and community nutrition workforce capacity would be captured through routine surveillance via established data collection efforts to allow for careful, ongoing monitoring of the need for capacity-building efforts.

Strengths and Limitations

A major strength of this study is the use of expert interviews in addition to the online survey, which allowed for a more comprehensive perspective than either method used alone. The inclusion of perspectives of both United States and global experts is also a strength. The scope of the interview component of the study was a limiting factor, because it did not allow for comprehensive analysis of public health and community nutrition workforce capacity across all countries. Another limitation is that the survey was not validated. In addition, participants’ ability to apply skills was self-rated and may be subject to respondents’ perceptions and social desirability bias. Additionally, the respondents who volunteered to participate in the study do not represent all RDNs or nutrition professionals who work in public health nutrition/community nutrition, given the low response rates for the survey and interviews, the recruitment methods, and the fact that most survey respondents were White, female Academy members. Finally, as these surveys and interviews were conducted a few years ago, it is possible that the public health and community nutrition workforce landscape has shifted in the interim; regular monitoring of the need for capacity building efforts is necessary.

Conclusion

Significant opportunity exists among key players in community and public health nutrition, including the Academy, to advocate for RDNs in the field and to improve training of the current dietetic workforce to increase capacity and support scaling up effective nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions to improve population health.46 , 47 Specifically, the Academy can consider adjusting education and internship requirements to support a more comprehensive focus on public health and community nutrition topics and skills; monitoring the impact of the new graduate degree requirement on the racial and ethnic diversity of the dietetic workforce and the percentage of RDNs that pursue public health and community nutrition careers; continuing to support fellowship and professional development opportunities in public health and community nutrition; partnering with DPGs, Member Interest Groups, and external public health organizations to strengthen capacity, resources, and actions around important public health and community nutrition topics; and supporting accurate and ongoing estimates of RDN workforce supply and demand in public health and community nutrition, which are urgently needed to guide and justify capacity building efforts, including information about workforce training opportunities and challenges, workforce demographics, remuneration, skill mix and emerging opportunities.47

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of the survey and interview participants and are grateful to the following former Academy staff members for their contributions to the initial design of this project and the distribution of the survey: Rosa Hand, PhD, RDN, LD, FAND; Cecily Byrne, MS, RDN, LDN; and William Murphy, MS, RDN.

Author Contributions

T. Y. El-Kour, M. Bruening, S. Robson, J. Vogelzang, J. Yang, and E. Y. Jimenez contributed to the development of the survey and interview questions. T. Y. El-Kour and K. Kelley conducted and coded interviews. T. Y. El-Kour, K. Kelley, and E. Y. Jimenez completed the data analysis and drafted the initial manuscript. All authors contributed to the data interpretation and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Biographies

T. Y. El-Kour is a global health and nutrition consultant and independent researcher, Amman, Jordan.

K. Kelley is a nutrition researcher, Nutrition Research Network, Research, International, and Scientific Affairs, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Chicago, IL.

M. Bruening is an associate professor, College of Health Solutions, Arizona State University, Phoenix.

S. Robson is an assistant professor, Department of Behavioral Health and Nutrition, University of Delaware, Newark.

J. Vogelzang is an associate professor, Grand Valley State University, Grand Rapids, MI.

J. Yang is an associate professor, Health Informatics Institute, University of South Florida, Tampa.

E. Y. Jimenez is director, Nutrition Research Network, Research, International, and Scientific Affairs, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Chicago, IL, and research associate professor, Departments of Pediatrics and Internal Medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM.

Footnotes

Supplementary materials:Figures 1 and 2 are available at www.jandonline.org.

STATEMENT OF POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

FUNDING/SUPPORT The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics provided staff support for the conduct of the study via the Nutrition Research Network.

Supplementary Materials

References

- 1.Public Health/Community Nutrition Practice Group Definitions Related to Public Health and Community Nutrition. https://www.phcnpg.org/docs/Public%20Health%20Nutrition%20Taskforce/Definitions%20final%207-24-12.pdf Updated July 2012. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 2.Definition of Terms Workgroup, Quality Management Committee Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Definition of Terms List. Definition of Terms Workgroup, Quality Management Committee. https://www.eatrightpro.org/-/media/eatrightpro-files/practice/scope-standards-of-practice/20190910-academy-definition-of-terms-list.pdf Updated June 2017. Accessed February 23, 2020.

- 3.Bruening M., Udarbe A., Yakes Jimenez E., Stell Crowley P., Fredericks D., Edwards Hall L. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Standards of professional practice and standards of professional performance for registered dietitian nutritionists (competent, proficient and expert) in public health and community nutrition. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(10):1699–1709. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.06.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition Malnutrition Mapping Project. http://globalalliance.s3-website-us-east-1.amazonaws.com/#v=map&b=topo&x=16.39&y=12.16&l=3&m=1&a=0

- 5.World Health Organization Global Health Estimates. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/en/

- 6.Popkin B. Global nutrition dynamics: The world is shifting rapidly toward a diet linked with noncommunicable diseases. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(2):289–298. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuster V. Changing demographics: A new approach to global health care due to the aging population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(24):3002–3005. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith N., Fraser M. Straining the system: Novel coronavirus (COVID-19) and preparedness for concomitant disasters. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(5):648–649. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.UN General Assembly Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development, A/RES/70/1. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf Published October 21, 2015. Accessed March 25, 2020.

- 10.World Health Organization Global health workforce shortage to reach 12.9 million in coming decades. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2013/health-workforce-shortage/en/ Published November 11, 2013. Accessed February 23, 2020.

- 11.Sheehan M., Fox M. Early warnings: The lessons of COVID-19 for public health climate preparedness. Int J Health Serv. 2020;50(3):264–270. doi: 10.1177/0020731420928971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azar K., Shen Z., Romanelli R. Disparities in outcomes among COVID-19 patients in a large health care system in California. Health Aff (Millwood) 2020;39(7):1253–1262. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim E.J., Marrast L., Conigliaro J. COVID-19: Magnifying the Effect of Health Disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(8):2441–2442. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05881-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Dorn A., Cooney R., Sabin M. COVID-19 exacerbating inequalities in the US. Lancet. 2020;395(10232):1243–1244. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30893-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fortuna L.R., Tolou-Shams M., Robles-Ramamurthy B., Porche M.V. Inequity and the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color in the United States: The need for a trauma-informed social justice response. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(5):443–445. doi: 10.1037/tra0000889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okonkwo NE, Aguwa UT, Jang M, et al. COVID-19 and the US response: accelerating health inequities [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 3]. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2020;bmjebm-2020-111426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Chowkwanyun M., Reed AL J.r. Racial Health Disparities and Covid-19 - Caution and Context. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(3):201–203. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2012910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Food in a time of COVID-19. Nat. Plants 6, 429 (2020). 10.1038/s41477-020-0682-7. Accessed September 30, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.United Nations World Food Programme. COVID-19 will double number of people facing food crises unless swift action is taken [press release]. Rome: United Nations World Food Programme; April 21, 2020.

- 20.Headey D., Heidkamp R., Osendarp S. et al. Impacts of COVID-19 on childhood malnutrition and nutrition-related mortality. Lancet. 2020;396(10250):519–521. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31647-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fore H.H., Dongyu Q., Beasley D.M., Ghebreyesus T.A. Child malnutrition and COVID-19: the time to act is now. Lancet. 2020;396(10250):517–518. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31648-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Lancet Maternal and child undernutrition. https://www.thelancet.com/series/maternal-and-child-nutrition Published June 6, 2013. Accessed October 30, 2019.

- 23.World Health Organization Essential nutrition actions: Improving maternal, newborn, infant and young child health and nutrition. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/84409 Published 2013. Accessed October 30, 2019. [PubMed]

- 24.United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Multi-sectoral nutrition strategy 2014-2025. http://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1867/USAID_Nutrition_Strategy_5-09_508.pdf Published May 2014. Accessed March 15, 2019.

- 25.Development Initiatives . Development Initiatives; Bristol, UK: 2020. Global Nutrition Report: Action on Equity to End Malnutrition. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Healthy People 2030. https://www.healthypeople.gov/ Updated March 13, 2020. Accessed March 15, 2020.

- 27.17 Goals to Transform Our World https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/

- 28.Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice Core competencies for public health professionals. http://www.phf.org/resourcestools/Documents/Core_Competencies_for_Public_Health_Professionals_2014June.pdf Updated June 26, 2014. Accessed March 15, 2020.

- 29.Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Revised 2017 Scope of Practice for the Registered Dietitian Nutritionist. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118(1):141–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jortberg B., Fleming M. Registered dietitian nutritionists bring value to emerging health care delivery models. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(12):2017–2022. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis A.M., Affenito S.G. Nutrition and public health: preparing registered dietitian nutritionists for marketplace demands. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(5):695–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griswold K., Rogers D. Compensation and benefits survey. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2019;120(3):448–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2019.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fanzo J., Graziose M., Kraemer K. Educating and training a workforce for nutrition in a post-2015 world. Adv Nutr. 2015;6(6):1639–1647. doi: 10.3945/an.115.010041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hughes R., Begley A., Yeatman H. Consensus on the core functions of the public health nutrition workforce in Australia. Public Health Nutr. 2015;73(1):103–111. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Population level nutrition intervention terminology. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Electronic Nutrition Care Process Terminology, https://www.ncpro.org/faqs-5. Accessed September 30, 2020.

- 36.Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Visioning report and recommendations. https://www.cdrnet.org/vault/2459/web/files/10369.pdf Published 2012. Accessed July 1, 2019.

- 37.Jackson C., Gracia J. Addressing health and health-care disparities: The role of a diverse workforce and the social determinants of health. Public Health Rep. 2014;129:57–61. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Public Health/Community Nutrition Practice Group and the Association of State Public Health Nutritionists Guide for Developing and Enhancing Skills in Public Health and Community Nutrition. https://www.phcnpg.org/docs/Resources/2018%20The%20Guide/PHCN%20Guide%20FINAL%20FULL.pdf Published 2018. Accessed March 15, 2020.

- 39.Palermo C., Hughes R., McCall L. An evaluation of a public health nutrition workforce development intervention for the nutrition and dietetics workforce. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2010;23(3):244–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2010.01069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Championing nutrition and dietetics practitioners in roles of leadership in public health. HOD fact sheet. https://www.eatrightpro.org/-/media/eatrightpro-files/leadership/hod/about-hod-meetings/fall2017/factsheetchampioningnuritionanddietetics.pdf?la=en&hash=D6120DA00F2F45641149279556F5E970E9F48C2B Published Fall 2017. Accessed March 15, 2020.

- 41.Kugelberg S., Jonsdottir S., Faxelid E. Public health nutrition workforce development in seven European countries: Constraining and enabling factors. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(11):1989–1998. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012003874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diversify Dietetics. Diversify Dietetics Inc. Published 2020, https://www.diversifydietetics.org/. Accessed July 19, 2020.

- 43.Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Member interest groups. https://www.eatrightpro.org/membership/academy-groups/member-interest-groups [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.UNICEF Indonesia Nutrition capacity assessment in Indonesia. https://www.unicef.org/indonesia/reports/nutrition-capacity-assessment-indonesia Published January 2018. Accessed March 15, 2020.

- 45.Fox A., Chenhall C., Traynor M. Public health nutrition practice in Canada: A situational assessment. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(8):773–781. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007001516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shrimpton R., du Plessis L., Delisle H. Public health nutrition capacity: Assuring the quality of workforce preparation for scaling up nutrition programmes. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(11):2090–2100. doi: 10.1017/S136898001500378X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haughton B., Stang J. Population risk factors and trends in health care and public policy. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:S35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]