Abstract

Background

The majority of South Africans rely on a resource-constrained public healthcare sector, where access to renal replacement therapy (RRT) is strictly rationed. The incidence of RRT in this sector is only 4.4 per million population (pmp), whereas it is 139 pmp in the private sector, which serves mainly the 16% of South Africans who have medical insurance. Data on the outcomes of RRT may influence policies and resource allocation. This study evaluated, for the first time, the survival of South African patients starting RRT based on data from the South African Renal Registry.

Methods

The cohort included patients with end-stage kidney disease who initiated RRT between January 2013 and September 2016. Data were collected on potential risk factors for mortality. Failure events included stopping treatment without recovery of renal function and death. Patients were censored at 1 year or upon recovery of renal function or loss to follow-up. The 1-year patient survival was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and the association of potential risk factors with survival was assessed using multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression.

Results

The cohort comprised 6187 patients. The median age was 52.5 years, 47.2% had diabetes, 10.2% were human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive and 82.2% had haemodialysis as their first RRT modality. A total of 542 patients died within 1 year of initiating RRT, and overall 1-year survival was 90.4% [95% confidence interval (CI) 89.6–91.2]. Survival was similar in patients treated in the private sector as compared with the public healthcare sector [hazard ratio 0.93 (95% CI 0.72–1.21)]. Higher mortality was associated with older age and a primary renal diagnosis of ‘Other’ or ‘Aetiology unknown’. When compared with those residing in the Western Cape, patients residing in the Northern Cape, Eastern Cape, Mpumalanga and Free State provinces had higher mortality. There was no difference in mortality based on ethnicity, diabetes or treatment modality. The 1-year survival was 95.9 and 94.2% in HIV-positive and -negative patients, respectively. One-fifth of the cohort had no data on HIV status and the survival in this group was considerably lower at 77.1% (P < 0.001).

Conclusions

The survival rates of South African patients accessing RRT are comparable to those in better-resourced countries. It is still unclear what effect, if any, HIV infection has on survival.

Keywords: dialysis, patient survival, renal replacement therapy, South Africa, transplantation

INTRODUCTION

The burden of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in Africa is growing, reflecting epidemiological transitions on the continent. In their systematic reviews, Stanifer et al. [1] and Kaze et al. [2] estimated the population prevalence at 13.9 and 15.8%, respectively, and report that the brunt of the CKD burden is borne by the sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) region. Some of the factors driving the CKD epidemic in Africa include the increasing prevalence of non-communicable diseases, such as hypertension and diabetes, together with a high burden of infectious diseases (such as HIV), pregnancy-related diseases, trauma-related complications and environmental toxins [3].

The incidence of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) in Africa is not known, but for those patients who progress to this stage, access to renal replacement therapy (RRT) with chronic dialysis or kidney transplantation is inequitable [4, 5]. Worldwide, it is estimated that 80% of dialysis patients reside in Europe, Japan and the USA [6]. This statistic is even more striking when considering that it is projected that 70% of patients reaching ESKD in 2030 will be residents of low-income countries [6].

As RRT programmes are developed and expanded around the world, it becomes increasingly important to monitor and report on the success of the treatment. A review by Anand et al. [5] described 1-year survival on dialysis for the various World Bank–defined regions using the most populous country from each region as a proxy. The lowest 1-year survival was found in Africa (63%), with Nigeria the representative country. This compares poorly with most other regions of the world, where 1-year survival rates are >85% [5]. Given the resource limitations faced by the governments of most African countries and the increasing growth of RRT programmes on the continent, it is vital that quality assurance programmes monitoring survival and other standards of care are put in place to protect patients and to justify the use of scarce health resources [7].

Renal registries are critical for quantifying the burden of ESKD and access to—and outcomes of—RRT, and their absence in most African countries results in many important knowledge gaps [8]. South Africa is among the few African countries that have a national renal registry; this registry covers all provinces and includes all RRT centres in the country. Since its re-establishment, annual reports have been published regularly, beginning with a report of 2012 data [9]. The latest report confirms that access to RRT is still very limited, as most South Africans do not have private medical insurance and must depend on underresourced public sector facilities for their health care [10, 11]. The overall incidence of RRT in South Africa was 25 per million population (pmp) in 2017, well below the incidence reported from better-resourced countries such as the USA (370 pmp) and the UK (121 pmp) [12, 13]. The incidence of RRT in the public sector is only 4.4 pmp, whereas it is 139 pmp in the private sector, which serves mainly the 16% of South Africans who have medical insurance. The prevalence of treated ESKD in the public sector is 66 pmp, less than one-tenth of the prevalence of 855 pmp in the private sector. In 1994, according to the last report of the previous national registry, most of the RRT was provided by public sector facilities and the overall prevalence was 70 pmp [9, 14]. There has therefore been no real growth in the access to RRT for most South Africans over the past 2.5 decades.

Given the steady improvements in data quality and recent opportunities to link to national records for validation of vital status, the aim of this study was to evaluate, for the first time, the survival of incident patients receiving RRT based on data from the South African Renal Registry (SARR).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data collection

This cohort study used data collected by the SARR to determine 1-year survival in South African patients receiving RRT. The details of methods and definitions used by the registry are described in the SARR annual reports [11]. In brief, the SARR collects country-wide data on all patients with ESKD who are treated with RRT. The data collection includes adults and children, covers all provinces and covers patients treated in the public as well as the private healthcare sectors. The list of treatment centres is included in each annual registry report [11]. Centres submit data to the registry upon registration of new patients and then annually, to provide follow-up information for December each year. In addition, transfers of treatment modalities or treatment centres are recorded, and any deaths or end of treatment events are also recorded. Regarding loss to follow-up, the SARR assumes that a functioning transplant is maintained unless there is evidence of a ‘transplant failure’ or death. A dialysis modality is assumed to continue for 1 year from the date of the last registry entry and thereafter the patient is considered lost to follow-up.

The cohort included patients with ESKD who initiated RRT between 1 January 2013 and 30 September 2016 and survived for at least 90 days. A cohort of prevalent patients who were alive on chronic dialysis or had a functioning kidney transplant on 31 December 2015 is described in Supplementary data, Appendix 1.

Data were exported on 5 November 2018 from the SARR database into Excel files (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and imported into Stata version 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) and Enterprise Guide version 5.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Prior to analysis, the data were subjected to an extensive cleaning process that is detailed in Supplementary data, Appendix 2. Validation of vital status against the database of the Department of Home Affairs was an important part of this process. It required the submission of valid South African identity numbers, which were available for 85% of the patients. Statistical analysis was conducted with the assistance of the UK Renal Registry statistics team.

Outcome definitions

The primary outcome was 1-year patient survival after 90 days of RRT. To study the association of potential risk factors with patient mortality, demographic and other clinical data were also used, including ethnicity, the primary renal diagnosis, the first RRT modality, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status, healthcare sector (public or private) and province of residence. In South Africa’s healthcare system, the public sector refers to government-funded medical facilities and services, while the private sector refers to medical services offered by private practitioners and institutions. Access to the latter depends on an individual’s ability to pay for these services, usually via private medical insurance. Failure events were defined as patient death or discontinuation of RRT without recovery of renal function. Patients were censored at the date of stopping treatment if they recovered renal function, emigrated or were lost to follow-up. Patients on dialysis were categorized as lost to follow-up 1 year after their last registry entry or other evidence of activity, such as a laboratory test result. Transplant patients were considered lost to follow-up 1 year after a ‘transplant failure’ entry if there were no subsequent entries recorded [11].

Statistical analysis

One-year patient survival was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Evidence of a difference in survival was assessed using the log rank test. The association of potential risk factors with 1-year patient survival was assessed using multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression. The statistical significance of the main effect of each risk factor was assessed by the maximum likelihood ratio test and Wald statistics. Age group, ethnicity, diabetes, primary renal diagnosis, first RRT modality, healthcare sector (public/private), province of residence and sex were all modelled individually and adjusted by different suites of confounders, determined by prior knowledge of whether they met the criteria for confounding (see Table 2) [15]. To assess whether the proportional hazard assumption holds, Schoenfeld residuals from the Cox regression model were examined by the rank test, Pearson’s correlation coefficients and by modelling them as time-dependent effects. There was no significant violation of the proportional hazards assumption in the survival model.

Table 2.

HRs for risk factors of interest by univariable and multivariable Cox regression

| Variable | Univariable model |

Multivariable model |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted for confoundera | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age group (years) | |||||

| <18 | 1.61 (0.78–3.35) | <0.01 | Healthcare sector, ethnicity | 1.57 (0.75–3.28) | <0.01 |

| 18–40 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 40–64 | 1.33 (1.03–1.73) | 1.33 (1.01–1.74) | |||

| 65–74 | 1.65 (1.22–2.24) | 1.68 (1.22–2.32) | |||

| ≥75 | 3.02 (2.2–4.14) | 3.10 (2.21–4.35) | |||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 1 | 0.08 | Age, healthcare sector | 1 | 0.40 |

| Black | 0.83 (0.66–1.03) | 1.00 (0.80–1.26) | |||

| Mixed ancestry | 0.68 (0.5–0.92) | 0.79 (0.58–1.09) | |||

| Indian/Asian | 0.91 (0.68–1.22) | 0.97 (0.73–1.3) | |||

| Diabetes | |||||

| Non-diabetic | 1 | 0.01 | Age, ethnicity and healthcare sector | 1 | 0.21 |

| Diabetic | 1.28 (1.07–1.53) | 1.13 (0.93–1.38) | |||

| Primary diagnosis | |||||

| Cystic kidney disease | 0.40 (0.15–1.09) | <0.01 | Age, ethnicity and healthcare sector | 0.43 (0.16–1.15) | <0.01 |

| Glomerular disease | 0.91 (0.63–1.32) | 1.08 (0.74–1.58) | |||

| Hypertensive renal disease | 1 | 1 | |||

| Diabetic nephropathy | 1.10 (0.86–1.4) | 1.03 (0.81–1.32) | |||

| Aetiology unknown | 1.40 (1.14–1.71) | 1.47 (1.19–1.82) | |||

| Other | 1.79 (1.24–2.59) | 1.80 (1.24–2.62) | |||

| First modality | |||||

| TX | 0.82 (0.26–2.56) | 0.11 | Age, ethnicity, diabetes, primary diagnosis and healthcare sector | 0.63 (0.15–2.6) | 0.24 |

| PD | 0.77 (0.60–0.98) | 0.78 (0.57–1.06) | |||

| HD | 1 | 1 | |||

| Healthcare sector | |||||

| Private | 1.19 (0.94–1.50) | 0.16 | Age, ethnicity | 0.93 (0.72–1.21) | 0.61 |

| Public | 1 | 1 | |||

| Province | |||||

| North West | 0.78 (0.46–1.35) | <0.01 | Ethnicity and healthcare sector | 0.78 (0.45–1.38) | <0.01 |

| Western Cape | 1 | 1 | |||

| Limpopo | 1.20 (0.75–1.92) | 1.22 (0.74–2.01) | |||

| KwaZulu-Natal | 1.37 (1.03–1.82) | 1.33 (0.94–1.86) | |||

| Gauteng | 1.46 (1.11–1.93) | 1.38 (1.01–1.90) | |||

| Eastern Cape | 1.52 (1.09–2.13) | 1.54 (1.07–2.22) | |||

| Free State | 1.84 (1.26–2.68) | 1.83 (1.21–2.76) | |||

| Mpumalanga | 1.83 (1.16–2.88) | 1.75 (1.08–2.85) | |||

| Northern Cape | 2.51 (1.46–4.31) | 2.45 (1.38–4.35) | |||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 1 | 0.84 | Age | 1 | 0.99 |

| Female | 0.98 (0.83–1.17) | 1.00 (0.84–1.19) | |||

The confounders are selected based on the prior knowledge that they have an association with mortality and are associated with the variable of interest but not an effect of the variable of interest nor a factor in the causal pathway of mortality.

Missing data were excluded from the statistical analysis. The percentage of missingness for demographic/clinical factors is described in Table 1. In the multivariable regression analysis, 92.1–99.8% of complete case data were used depending on which variables were involved in the models.

Table 1.

Baseline variables for the study cohort by healthcare sector

| Variable | All patients (N = 6187), n (%) | Public sector ( N= 1042), n (%) | Private sector ( N= 5145), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 52.5 (41.2–62.5) | 38.0 (28.7–46.3) | 55.0 (45.2–64.3) |

| Age group (years) | |||

| <18 | 82 (1.3) | 56 (5.4) | 26 (0.5) |

| 18–39 | 1143 (18.5) | 451 (43.3) | 692 (13.5) |

| 40–64 | 3469 (56.1) | 501 (48.1) | 2968 (57.7) |

| 65–74 | 1010 (16.3) | 26 (2.5) | 984 (19.1) |

| ≥75 | 483 (7.8) | 8 (0.8) | 475 (9.2) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 2516 (40.7) | 499 (47.9) | 2017 (39.2) |

| Male | 3671 (59.3) | 543 (52.1) | 3128 (60.8) |

| First RRT modality | |||

| HD | 5088 (82.2) | 430 (41.3) | 4658 (90.5) |

| PD | 1049 (17.0) | 591 (56.7) | 458 (8.9) |

| Transplant | 50 (0.8) | 21 (2.0) | 29 (0.6) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Black | 3338 (53.9) | 689 (66.1) | 2649 (51.5) |

| White | 1086 (17.6) | 52 (5.0) | 1034 (20.1) |

| Mixed ancestry | 865 (14.0) | 224 (21.5) | 641 (12.5) |

| Indian/Asian | 805 (13.0) | 57 (5.5) | 748 (14.5) |

| Other/Unknown | 93 (1.5) | 20 (1.9) | 73 (1.4) |

| Diabetes | |||

| Diabetes present | 2879 (46.5) | 199 (19.1) | 2680 (52.1) |

| No diabetes | 2923 (47.2) | 796 (76.4) | 2127 (41.3) |

| No data | 385 (6.2) | 47 (4.5) | 338 (6.6) |

| Primary diagnosis | |||

| Hypertensive renal disease | 2246 (36.3) | 212 (20.4) | 2034 (39.5) |

| Aetiology unknown | 1824 (29.4) | 544 (52.2) | 1280 (24.9) |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 1252 (20.2) | 41 (3.9) | 1211 (23.5) |

| Glomerular diseasea | 479a (7.7) | 176 (16.9) | 303 (5.9) |

| Cystic kidney disease | 124 (2.0) | 17 (1.6) | 107 (2.1) |

| Otherb | 262 (4.2) | 52 (5.0) | 210 (4.1) |

| Province | |||

| Eastern Cape | 647 (10.5) | 119 (11.4) | 528 (10.3) |

| Free State | 361 (5.8) | 102 (9.8) | 259 (5.0) |

| Gauteng | 1596 (25.8) | 134 (12.9) | 1462 (28.4) |

| KwaZulu-Natal | 1532 (24.8) | 250 (24.0) | 1282 (24.9) |

| Limpopo | 293 (4.7) | 62 (6.0) | 231 (4.5) |

| Mpumalanga | 214 (3.5) | 3 (0.3) | 211 (4.1) |

| North West | 307 (5.0) | 59 (5.7) | 248 (4.8) |

| Northern Cape | 102 (1.7) | 31 (3.0) | 71 (1.4) |

| Western Cape | 1135 (18.3) | 282 (27.1) | 853 (16.6) |

| Hepatitis B status | |||

| Carrier | 102 (1.7) | 13 (1.3) | 89 (1.7) |

| Immune | 440 (7.1) | 229 (22.0) | 211 (4.1) |

| Negative | 4586 (74.1) | 595 (57.1) | 3991 (77.6) |

| No data | 1059 (17.1) | 205 (19.7) | 854 (16.6) |

| Hepatitis C status | |||

| Positive | 31 (0.5) | 5 (0.5) | 26 (0.5) |

| Negative | 4817 (77.9) | 739 (70.9) | 4078 (79.3) |

| No data | 1339 (21.6) | 298 (28.6) | 1041 (20.2) |

| HIV status | |||

| Positive | 633 (10.2) | 104 (10.0) | 529 (10.3) |

| Negative | 4324 (69.9) | 681 (65.4) | 3643 (70.8) |

| No data | 1230 (19.9) | 257 (24.7) | 973 (18.9) |

Includes 94 patients with nephropathy related to HIV.

Includes all other primary renal diagnoses, comprising 4.2% of the cohort.

Ethical considerations

Approval for the study was granted by the Health Research Ethics Committee of Stellenbosch University (reference no. N11/01/028).

RESULTS

The cohort comprised 6187 patients. Baseline variables are summarized in Table 1. The median age at the start of RRT was 52.5 years [interquartile range (IQR) 41.2-62.5 years] and the majority (56.1%) were in the 40- to 64-year age group. More than half (53.9%) were Black and most (83.1%) received their treatment in the private sector. Haemodialysis (HD) was the predominant first treatment modality (82.2%).

Nearly half of all patients had diabetes. Hypertensive nephropathy was the most common primary renal diagnosis, followed by ESKD of unknown cause and diabetic nephropathy.

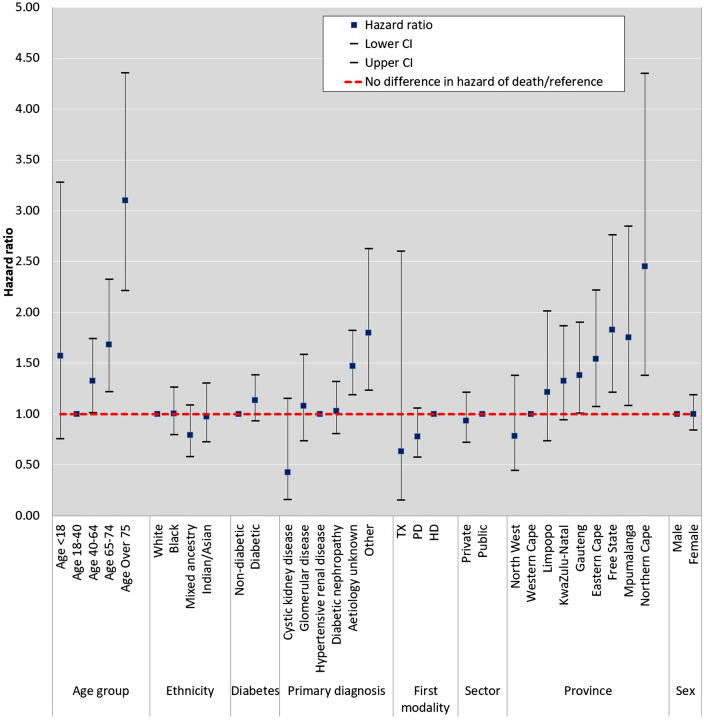

A total of 542 patients died within 1 year of initiating RRT. Overall, 1-year survival was 90.4% [95% confidence interval (CI) 89.6–91.2] (Supplementary data, Figure S2). Multivariable analysis of risk factors revealed that lower survival was associated with older age, a primary renal diagnosis of ‘Other’ or ‘Unknown’ and residence in specific provinces (Figure 1 and Table 2). Compared with patients in the 18- to 40-year age group, older patients were found to have higher adjusted mortality. Those in the 40- to 64-year age group had a 42% higher chance of dying [hazard ratio (HR) 1.42 (95% CI 1.05–1.93)] and the highest mortality was found in patients >75 years of age [HR 3.40 (95% CI 2.33–4.97)]. Compared with patients with a primary renal diagnosis of hypertensive renal disease, the adjusted mortality was higher in patients with ESKD of unknown aetiology [HR 1.47 (95% CI 1.16–1.86)] and those categorized as ‘Other’ [HR 1.74 (95% CI 1.16–2.63)]. Patients with diabetes did not have a significant difference in survival compared with patients without diabetes. Patients residing in the provinces of the Eastern Cape, Free State, Mpumalanga and Northern Cape had worse 1-year survival compared with those residing in the Western Cape. Those residing in the Northern Cape had the highest adjusted mortality [HR 2.53 (95% CI 1.38–4.63)]. Neither ethnicity, first RRT modality nor health sector (private/public) were independently associated with 1-year survival.

FIGURE 1.

HRs by multivariable Cox regression for each of the potential risk factors for 1-year survival in incident patients on RRT. Age group, ethnicity, diabetes, primary renal diagnosis, first treatment modality, healthcare sector (public/private), province of residence and sex are all modelled individually and adjusted by a different suite of confounders. The confounders are selected based on the prior knowledge that they have an association with mortality and are associated with the variable of interest but not an effect of the variable of interest nor a factor in the causal pathway of mortality. Age group was adjusted for healthcare sector and ethnicity; ethnicity was adjusted for age and healthcare sector; diabetes was adjusted for age, ethnicity and healthcare sector; primary renal diagnosis was adjusted for age, ethnicity and healthcare sector; first modality was adjusted for age, ethnicity, diabetes, primary diagnosis and healthcare sector; healthcare sector was adjusted for age and ethnicity; province was adjusted for ethnicity and healthcare sector and sex was adjusted for age.

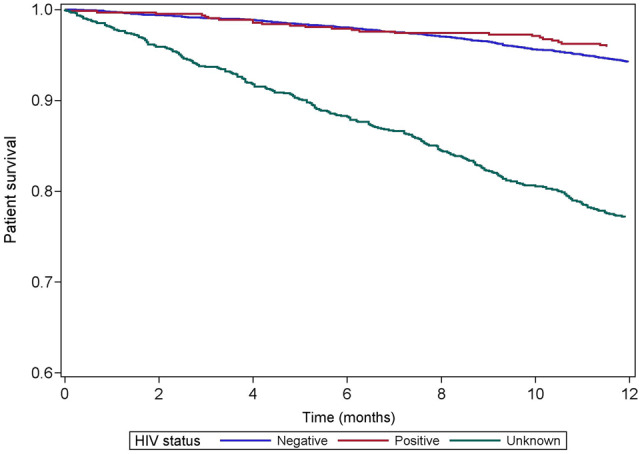

The baseline characteristics of the cohort by HIV status are summarized in Table 3. Approximately 10% of the patients were HIV positive. Crude 1-year survival was 95.9% and 94.2% in HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients, respectively (Figure 2). One-fifth of the cohort had no data on HIV status and the survival in this group was considerably lower at 77.1% (P < 0.001). There were similar proportions of missing data on hepatitis B and C serological status, with similar survival plots (Supplementary data, Appendix 3).

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics by HIV status

| Variable | HIV negative (N = 4324), n (%) | HIV positive (N = 633), n (%) | HIV unknown (N = 1230), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 54.0 (42.1–63.9) | 45.3 (38.1–52.6) | 52.4 (40.3–61.9) |

| Age group (years) | |||

| <18 | 63 (1.5) | 5 (0.8) | 14 (1.1) |

| 18–39 | 751 (17.4) | 144 (22.8) | 248 (20.2) |

| 40–64 | 2337 (54.1) | 455 (71.9) | 677 (55.0) |

| 65–74 | 799 (18.5) | 24 (3.8) | 187 (15.2) |

| ≥75 | 374 (8.7) | 5 (0.8) | 104 (8.5) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1766 (40.8) | 258 (40.8) | 492 (40.0) |

| Male | 2558 (59.2) | 375 (59.2) | 738 (60.0) |

| First RRT modality | |||

| HD | 3543 (81.9) | 548 (86.6) | 997 (81.1) |

| PD | 746 (17.3) | 82 (13.0) | 221 (18.0) |

| Transplant | 35 (0.8) | 3 (0.5) | 12 (1.0) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Black | 1985 (45.9) | 598 (94.5) | 755 (61.4) |

| White | 890 (20.6) | 6 (1.0) | 190 (15.5) |

| Mixed ancestry | 762 (17.6) | 15 (2.4) | 88 (7.2) |

| Indian/Asian | 617 (14.3) | 9 (1.4) | 179 (14.6) |

| Other/Unknown | 70 (1.6) | 5 (0.8) | 18 (1.5) |

| Diabetes | |||

| Diabetes present | 2124 (49.1) | 218 (34.4) | 537 (43.7) |

| No diabetes | 2056 (47.6) | 386 (61.0) | 481 (39.1) |

| No data | 144 (3.3) | 29 (4.6) | 212 (17.2) |

| Primary diagnosis | |||

| Hypertensive renal disease | 1659 (38.4) | 232 (36.7) | 355 (28.9) |

| Aetiology uncertain | 1048 (24.2) | 195 (30.8) | 581 (47.2) |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 999 (23.1) | 80 (12.6) | 173 (14.1) |

| Glomerular diseasea | 317 (7.3) | 110 (17.4) | 52 (4.2) |

| Cystic kidney disease | 110 (2.5) | 4 (0.6) | 10 (0.8) |

| Otherb | 191 (4.4) | 12 (1.9) | 59 (4.8) |

| Healthcare sector | |||

| Public | 681 (15.8) | 104 (16.4) | 257 (20.9) |

| Private | 3643 (84.3) | 529 (83.6) | 973 (79.1) |

| Province | |||

| Eastern Cape | 449 (10.4) | 76 (12.0) | 122 (9.9) |

| Free State | 255 (5.9) | 55 (8.7) | 51 (4.2) |

| Gauteng | 1065 (24.6) | 153 (24.2) | 378 (30.7) |

| KwaZulu-Natal | 962 (22.3) | 202 (31.9) | 368 (29.9) |

| Limpopo | 201 (4.7) | 33 (5.2) | 59 (4.8) |

| Mpumalanga | 125 (2.9) | 42 (6.6) | 47 (3.8) |

| North West | 156 (3.6) | 28 (4.4) | 123 (10.0) |

| Northern Cape | 76 (1.8) | 3 (0.5) | 23 (1.9) |

| Western Cape | 1035 (23.9) | 41 (6.5) | 59 (4.8) |

| Hepatitis B status | |||

| Carrier | 65 (1.5) | 30 (4.7) | 7 (0.6) |

| Immune | 374 (8.7) | 33 (5.2) | 33 (2.7) |

| Negative | 3797 (87.8) | 525 (82.9) | 264 (21.5) |

| No data | 88 (2.0) | 45 (7.1) | 926 (75.3) |

| Hepatitis C status | |||

| Positive | 27 (0.6) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) |

| Negative | 4024 (93.1) | 547 (86.4) | 246 (20.0) |

| No data | 273 (6.3) | 84 (13.3) | 982 (79.8) |

Includes nephropathy related to HIV.

bIncludes all other primary renal diagnoses.

FIGURE 2.

One‐year survival by HIV status in incident patients.

DISCUSSION

This study revealed several novel findings. First, South Africans on RRT have good 1-year survival rates of ~90%, with no difference between patients treated in the public and private healthcare sectors, even after adjustment for case mix. We found older age, a primary renal diagnosis of ‘Unknown’ or ‘Other’ and residence in the provinces of the Northern Cape, Eastern Cape, Mpumalanga or Free State to be associated with higher mortality. Furthermore, in those patients with data on HIV status, we observed similar survival rates between HIV-positive and -negative patients.

The higher mortality among older patients is a finding consistent with registry data from the USA, Europe, Australia and New Zealand [16–18]. A multicentre study of 538 incident HD cases at South Africa’s largest private dialysis provider also found age to be associated with poorer survival [19]. The Dialysis Outcomes Practice Patterns Study, which included HD patients from the USA, Japan and Europe, found diabetes mellitus to be associated with higher mortality [20]. Several studies have described inferior survival in patients with diabetic nephropathy, including a study based on data from the European Renal Association–European Dialysis and Transplant Association registry [21]. In our study, diabetes was not independently associated with 1-year mortality.

In this study, mortality was higher in incident patients with ESKD of unknown aetiology. This is a large group, mainly comprising patients who present to the health system with advanced CKD and small kidneys and in whom it is difficult to make a specific renal diagnosis. The proportion of South African patients on RRT with an unknown primary renal diagnosis (29.4% of the cohort) is much higher than is reported from countries such as the UK (14.6%) [22] and the USA (3.5%) [16] but is similar to that seen in African countries such as Sudan (42.6%), Tunisia (29.2%) and Morocco (37.9%) [23–25]. This group may have poorer outcomes because it likely includes many late presenters who have not had the benefit of pre-ESKD specialist care, a problem more common in resource-constrained settings such as South Africa.

Although we have previously reported [11] marked differences in RRT prevalence rates between provinces in South Africa, in this article we report, for the first time, significant differences in survival on RRT between provinces. The explanation for these differences is likely to be complex and include factors such as the distribution of treatment centres and nephrology human resources, remoteness or rural dwelling, access to public sector RRT programmes and access to kidney transplantation. The impact of remoteness and rural dwelling is well documented in developed countries. A study based on US Renal Data System data found higher mortality to be associated with remoteness rather than ruralness [26]. A similar study from the Canadian Organ Replacement Registry reported higher overall mortality and deaths from infectious causes among HD patients who lived farther from their attending nephrologist [27]. Developing countries such as South Africa are likely to have a greater proportion of remote or rural patients requiring RRT [28]. A recent study comparing rural and urban South African CKD patients attending a tertiary hospital in the province of KwaZulu-Natal found that rural patients presented with more advanced renal disease and had higher rates of HIV infection [28]. Another South African study, at a private–public dialysis centre in Limpopo, found rural dwelling to be associated with higher all-cause mortality in patients treated with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis [29].

We studied incident patients who were alive for at least 90 days following the initiation of RRT. High mortality in the first 90 days following the start of RRT has been highlighted in studies conducted in other African countries [30–32]. The survival rates reported here are in line with the findings of two other South African studies that included the first 90 days following the initiation of treatment [19, 33].

The survival rates of South Africans on RRT are comparable to those of better-resourced countries such as the UK (90.4%) and USA (81.1%) and higher than those of the few African countries with survival data, including Cameroon (73.2%) and Ethiopia (42.1%) [13, 16, 30, 34]. Our cohort differed from those of the USA and UK with regards to age, in that our patients were younger, with a lower proportion of patients ≥65 years of age. This may be at least partly explained by the strict rationing of RRT in the South African public healthcare sector.

In the light of South Africa’s HIV epidemic, it is important to consider the survival of HIV-positive patients on RRT who, prior to 2007, were largely excluded from public sector RRT programmes [35, 36]. A recent study at a large public sector hospital in the province of KwaZulu-Natal reported 1-year survival of 81.5% for HIV-positive patients receiving RRT and suggested that even those patients with low CD4 cell counts or who are not yet established on antiretroviral therapy should be able to access RRT [37]. We found that patients with missing data for HIV have worse survival compared with patients with HIV data, and even worse than that of patients who tested positive for HIV. We observed a very similar picture when analysing the impact of hepatitis B and C status; survival was lower among patients in whom both hepatitis B and C status were unknown (Supplementary data, Appendix 3). The submission of data on viral serology to the SARR is currently optional and we speculate that patients who survive longer are more likely to have these optional elements entered on one of the annual rounds of data submission. It is also possible that there may be underreporting of HIV in the group with missing HIV data. Nearly one-quarter of our patients had missing data on HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C status and this limits our ability to draw any firm conclusions about their impact on survival.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first report of survival on RRT at a national level in an SSA country using data collected as part of a national renal registry. With the SARR now providing the platform for five sub-Saharan countries as part of the African Renal Registry, this represents a significant evolution of quality assurance in RRT in Africa [8]. The use of linkage to a national death register to validate mortality status is state of the art and addresses many historical concerns about outcomes on RRT in Africa. Our study had several limitations, however. South African identity numbers were not available for ~15% of our patients and we could not cross-check their vital status with the database of the Department of Home Affairs. For these patients, we relied on data from the treatment centres and dialysis provider companies. The observational nature of the study meant that we could only determine associations and not causality. Furthermore, despite concerted efforts to clean the data (as detailed in Supplementary data, Appendix 2), there were residual missing data, particularly with regards to HIV, hepatitis B and hapatitis C serological status. We excluded patients who died within the first 90 days of initiating RRT and will need to analyse these early deaths in a subsequent study.

CONCLUSIONS

The 1-year survival of South African patients on RRT is favourable and compares well with survival rates reported from better-resourced countries. There are marked differences in survival rates between provinces, however, and these will need to be presented to health policymakers in South Africa and investigated in the future through quality assurance and research. It is still unclear what impact, if any, HIV status has on patient survival. There is no difference in 1-year survival between the public and private healthcare sectors. The findings of this study should encourage policymakers to increase access to life-sustaining RRT in the public sector.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1. Stanifer JW, Jing B, Tolan S. et al. The epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Global Health 2014; 2: e174–e181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaze AD, Ilori T, Jaar BG. et al. Burden of chronic kidney disease on the African continent: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol 2018; 19: 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stanifer JW, Muiru A, Jafar TH. et al. Chronic kidney disease in low- and middle-income countries. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016; 31: 868–874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Luyckx VA, Naicker S, McKee M.. Equity and economics of kidney disease in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet 2013; 382: 103–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Anand S, Bitton A, Gaziano T.. The gap between estimated incidence of end-stage renal disease and use of therapy. PLoS One 2013; 8: e72860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liyanage T, Ninomiya T, Jha V. et al. Worldwide access to treatment for end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review. Lancet 2015; 385: 1975–1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moosa MR, Meyers AM, Gottlich E. et al. An effective approach to chronic kidney disease in South Africa. S Afr Med J 2016; 106: 156–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Davids MR, Eastwood JB, Selwood NH. et al. A renal registry for Africa: first steps. Clin Kidney J 2016; 9: 162–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davids MR, Marais N, Jacobs JC.. South African Renal Registry Annual Report 2012. Cape Town, South Africa: South African Renal Society, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Council for Medical Schemes Annual Report 2015/16. Pretoria, South Africa: Council for Medical Schemes, 2016

- 11. Davids MR, Jardine T, Marais N. et al. South African Renal Registry Annual Report 2017. Afr J Nephrol 2019; 22: 60–71 [Google Scholar]

- 12.United States Renal Data System. US Renal Data System 2019 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 13. UK Renal Registry 21st Annual Report – Data to 31/12/2017. Bristol, UK: UK Renal Registry, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Du Toit ED, Pascoe M, MacGregor K. et al. SADTR Report 1994. Combined Report on Maintenance Dialysis and Transplantation in the Republic of South Africa. Cape Town, South Africa: South African Dialysis and Transplantation Registry, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jager K, Zoccali C, Macleod A. et al. Confounding: what it is and how to deal with it. Kidney Int 2008; 73: 256–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.United States Renal Data System. 2018 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 17. ERA-EDTA Registry 2016 Annual Report. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: ERA-EDTA Registry, Amsterdam University Medical Center, Department of Medical Informatics, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 18. ANZDATA Registry 42nd Report, Chapter 3: Mortality in End Stage Kidney Disease. Adelaide, Australia: Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fabian J, Van Jaarsveld K, Maher HA. et al. Early survival on maintenance dialysis therapy in South Africa: evaluation of a pre-dialysis education programme. Clin Exp Nephrol 2016; 20: 118–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goodkin DA, Bragg-Gresham JL, Koenig KG. et al. Association of comorbid conditions and mortality in hemodialysis patients in Europe, Japan, and the United States: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). J Am Soc Nephrol 2003; 14: 3270–3277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Van Dijk PCW, Jager KJ, Stengel B. et al. Renal replacement therapy for diabetic end-stage renal disease: data from 10 registries in Europe (1991–2000). Kidney Int 2005; 67: 1489–1499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hole B, Gilg J, Casula A. et al. UK renal replacement therapy adult incidence in 2016: national and centre-specific analyses. Nephron 2018; 139(Suppl 1): 13–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Elamin S, Obeid W, Abu-Aisha H.. Renal replacement therapy in Sudan, 2009. Arab J Nephrol Transplant 2010; 3: 31–36 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rapport D’Activite Des Centres et Unites D’Hemodialyse, Annee 2010 Tunis, Tunisia: Ministere de la Sante Publique, 2011

- 25. Insuffisance Rénale Chronique Terminale Rabat, Morocco: Moroccan Society of Nephrology and Moroccan Ministry of Health, 2013

- 26. Thompson S, Gill J, Wang X. et al. Higher mortality among remote compared to rural or urban dwelling hemodialysis patients in the United States. Kidney Int 2012; 82: 352–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tonelli M, Manns B, Culleton B. et al. ; for the Alberta Kidney Disease Network. Association between proximity to the attending nephrologist and mortality among patients receiving hemodialysis. Can Med Assoc J 2007; 177: 1039–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Singh M, Magula NP, Hariparshad S. et al. A comparison of urban and rural patients with chronic kidney disease referred to Inkosi Albert Luthuli Central Hospital in Durban, South Africa. Afr J Nephrol 2017; 20: 34–38 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Isla RAT, Ameh OI, Mapiye D. et al. Baseline predictors of mortality among predominantly rural-dwelling end-stage renal disease patients on chronic dialysis therapies in Limpopo, South Africa. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0156642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shibiru T, Gudina EK, Habte B. et al. Survival patterns of patients on maintenance hemodialysis for end stage renal disease in Ethiopia: summary of 91 cases. BMC Nephrol 2013; 14: 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Eghan BA, Amoako-Atta K, Kankam CA. et al. Survival pattern of hemodialysis patients in Kumasi, Ghana: a summary of forty patients initiated on hemodialysis at a new hemodialysis unit. Hemodial Int 2009; 13: 467–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Alasia DD, Emem-Chioma P, Wokoma FS.. A single-center 7-year experience with end-stage renal disease care in Nigeria—a surrogate for the poor state of ESRD care in Nigeria and other sub-Saharan African countries: advocacy for a global fund for ESRD care program in sub-Saharan African countries. Int J Nephrol 2012; 2012:639653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kapembwa KC, Bapoo NA, Tannor EK, Davids MR.. Peritoneal dialysis technique survival at Tygerberg Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa. Afr J Nephrol 2017; 20: 25–33 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Halle MP, Ashuntantang G, Kaze FF. et al. Fatal outcomes among patients on maintenance haemodialysis in sub-Saharan Africa: a 10-year audit from the Douala General Hospital in Cameroon. BMC Nephrol 2016; 17: 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Guidelines for renal replacement therapy in HIV-infected individuals in South Africa. South Afr J HIV Med 2008; 9: a655 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wearne N. Morbidity and mortality of black HIV-positive patients with end-stage kidney disease receiving chronic haemodialysis in South Africa. S Afr Med J 2015; 105: 105–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Somaroo H, Hariparshad S, Assounga A. et al. Favourable prognosis with renal replacement therapy, among South African public health sector patients with end-stage renal disease and HIV-infection, and baseline CD4-cell counts between 50 and 200 cells/mm3. Afr J Nephrol 2016; 19: 17–18 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.