Abstract

Acute limb ischemia (ALI) is a vascular emergency associated with a high risk for limb loss and death. Most cases result from in situ thrombosis in patients with preexisting peripheral arterial disease or those who have undergone vascular procedures including stenting and bypass grafts. The other common source is cardioembolic. The incidence has decreased in recent times due to better anticoagulation strategies. Patients with suspected ALI should be evaluated promptly by a vascular specialist and consideration should be given for transfer to a higher level of care if such expertise is not available locally. Initial assessment should focus on staging severity of ischemic injury and potential for limb salvage. Neurological deficits can occur early and are an important poor prognostic sign. Duplex ultrasound and computed tomography angiography help plan intervention in patients with a still-viable limb and prompt catheter-based angiography is mandated in patients with an immediately threatened limb. Further investigations need to be pursued to differentiate embolic from thrombotic cause for acute occlusion as this can change management. Options include intravascular interventions, surgical bypass, or a hybrid approach. In this article, the authors discuss the common etiologies, clinical evaluation, and management of patients presenting with acute limb ischemia.

Keywords: acute limb ischemia, limb viability, etiology, thromboembolism, thrombolysis, thrombectomy, amputation.

Acute limb ischemia (ALI) results from an acute (<2 weeks), abrupt decrease in arterial perfusion of the limb, and can lead to tissue loss and threaten limb viability. Unlike critical limb ischemia (CLI), there is usually not enough time for the limb to generate collaterals and tissue loss results from unmet metabolic needs at rest. ALI is a vascular emergency and requires quick revascularization by endovascular, surgical, or a hybrid approach to avoid limb loss. About 8 to 10 million Americans suffer from peripheral arterial disease (PAD) with an overall prevalence rate of around 12% in the adult population. 1 Incidence of ALI is rare with 1 to 2 cases per 10,000 persons per year in the general population with higher incidence rates (∼1.7%) noted in patients with preexisting advanced PAD. 2 However, prognosis is uniformly poor despite early revascularization with amputation rates around 10 to 15%. 3

Patients with ALI are usually younger at presentation compared with patients with chronic limb ischemia. However, they share similar comorbid conditions that are associated with chronic PAD such as smoking, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease. Additionally, patients with ALI also tend to have advanced atherosclerotic disease involving other vascular beds such as the coronary and cerebral circulation. This is likely responsible for the high event rates both in the short-term and at 1-year follow-up (∼20% mortality rate). 1 3 4 A substudy of the EUCLID (examining use of ticagrelor in peripheral artery disease) trial examined outcomes in 13,885 PAD patients hospitalized with ALI. This study reported a 1.4-fold greater risk of a major adverse cardiac event, 3.3-fold greater risk of all-cause mortality, and 14.2-fold greater risk of major amputation. 2 This finding underlines the burden of ALI both on the patient as an individual, as well as on the health care system.

Etiology

Etiologies for nontraumatic ALI can be broadly classified into embolic and thrombotic events. 5 6 7 The most common etiology is acute thrombosis of a previous bypass graft or stent followed by plaque rupture/disease progression in native vessels. Rarely, thrombosis of arterial aneurysms (usually the popliteal artery) and aortic dissections can also cause ALI. Embolic events result from thrombus in the cardiac chambers or on valves, or from atherosclerosis of native arteries. This can occur as a sequela of atrial fibrillation, recent myocardial infarction, severe left ventricular dysfunction, endocarditis, or prosthetic valve leaflet thrombosis from suboptimal anticoagulation. Iatrogenic causes include access trauma to the vessels, use of vasopressor agents, and institution of venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for cardiopulmonary support. Other less common etiologies include venous obstruction (phlegmasia cerulea dolens), paradoxical emboli (across cardiac septal defects), vasculitidis, such as Raynaud's disease for the upper extremity and Buerger's disease (thromboangiitis obliterans) for the lower extremities, and hypercoagulable states (antiphospholipid syndrome, factor-V leiden mutation, and protein C/S deficiencies). A comprehensive list of commonly reported etiologies for ALI is listed in Table 1 .

Table 1. Common etiologies and clinical clues to differentiate embolic and in situ thrombosis.

| Embolism | In situ thrombosis | |

|---|---|---|

| Etiology | Arrhythmia (atrial fibrillation) | Atherosclerosis and arterial plaque rupture (aorta/iliac vessels) |

| Acute myocardial infarction, LV dysfunction/aneurysm | Low-flow states, congestive heart failure, circulatory shock, hypercoagulable states (malignancy, thrombophilias) | |

| Valvular heart disease: Rheumatic, degenerative, native or prosthetic endocarditis | Bypass graft disease | |

| Arterial causes: Aneurysm (aortic/popliteal), atherosclerotic plaque from aorta/iliac vessels | Trauma | |

| Iatrogenic: Peripheral interventions, TAVI, CABG, ECMO | Aortic dissection | |

| Venous causes: Paradoxical embolus with venous thrombosis, phlegmasia cerulea dolens | External compression (popliteal entrapment or adventitial cyst with thrombosis) | |

| Trauma | Iatrogenic | |

| Idiopathic | Ergotism | |

| Other: Air, amniotic fluid, fat, tumor, drug abuse | Large/medium vessel arteritis | |

| History | Acute onset, severe pain | Insidious onset of pain, less severe |

| Cardiac history of arrhythmias/MI | No recent cardiac events | |

| No peripheral vascular disease | History of peripheral vascular disease with/without prior interventions | |

| Physical exam | Arrhythmia | No arrhythmia |

| Severe signs of ischemia | Less severe signs of ischemia | |

| Cold and mottled foot | Cool and cyanotic foot | |

| Usually normal contralateral limb | Abnormal contralateral limb pulses often with signs of chronic limb ischemia (hair loss, shiny skin, thickened nails) | |

| Clear demarcation | No distinct demarcation | |

| Affected artery soft and tender to palpation. Bruit is usually absent. | Affected artery hard and calcified on palpation. Bruit may be audible. | |

| Severity of ischemia on presentation | Immediately threatened (IIb) most commonly | Marginally threatened (IIa) most commonly |

| Angiographic findings | Embolic lesions tend to favor arterial bifurcation sites (common femoral, distal popliteal) | Thrombotic lesions are usually accompanied by significant proximal vessel disease along with evidence for collaterals. |

| Proximal vessels appear clean with arterial cut-off (meniscus sign) and no evidence for collaterals | – |

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; LV, left ventricle; MI, myocardial Infarction; TAVI, trans-catheter aortic valve implantation.

Clinical Presentation

A focused history and physical exam by a vascular specialist are vital in the early assessment and triage of patients presenting with ALI and is a class-1 AHA/ACC (American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology) recommendation. 8 Most patients will have risk factors for both thrombotic and embolic etiologies, and the aim of the initial evaluation should be to differentiate and investigate for the underlying etiology apart from assessing the degree of limb ischemia. Table 1 lists important clinical clues to differentiate thrombotic from embolic causes for ALI. This should include a comprehensive cardiovascular evaluation for risk factors including history of prior myocardial infarction (MI) and PAD including prior interventions, cardiomyopathies, tachyarrhythmias, valvular disease, history of tobacco use, family history, and prior bleeding/clotting disorders. Once the limb is revascularized, further testing for cardiac etiology with an electrocardiogram or additional heart rhythm monitoring (such as event monitor for occult atrial fibrillation) and an echocardiogram is recommended. 8 Other nonvascular causes for foot pain include severe peripheral neuropathy, arthritidis such as acute gout, traumatic soft tissue injury, deep vein thrombosis, cellulitis/fasciitis, and spontaneous venous hemorrhage.

The typical clinical presentation of acute limb ischemia is encompassed by “the rule of P's”: pain, pulselessness, pallor, poikilothermia (cool extremity), paresthesia, and finally, onset of paralysis. 7 9 10

Pain: ischemic pain in ALI tends to be abrupt onset and severe especially in embolic causes. In the case of worsening of chronic PAD, the onset of pain is more insidious and patients can report progression from intermittent claudication to acute rest pain. Symptoms are usually unilateral except in rare circumstances where patients can present with bilateral lower extremity ischemia. Occasionally, pain may be absent in case of complete ischemia or in the presence of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. It is important to assess location, intensity, and progression of pain (usually ascending from foot) to assess severity and duration of ischemia. Muscle tenderness on palpation of the calf is an ominous physical sign for irreversible tissue necrosis.

Pulselessness: typically, there is a bounding pulse one arterial level above the occlusion with loss of pulse at the level of occlusion. If pulses are normal in the contralateral limb, this is a clue for an embolic etiology as thrombotic disease tends to be symmetrical and affects both extremities. However, palpation can be unreliable and the Doppler examination of the pulses can help identify the site of occlusion. Presence of a normal triphasic signal in the distal vessels rules out ALI. Soft monophasic signals indicate obstruction more proximally. Absent arterial Doppler signal confirms the diagnosis and site of occlusion and absent Doppler venous signal (usually popliteal vein in the popliteal fossa) is a sign of advanced ischemia and poor prognosis overall. If flow is audible on the Doppler study only, then measurement of the perfusion pressure proximal to Doppler probe of <50 mm Hg, is indicative of severe limb ischemia.

Pallor: in the early stages of complete occlusion, the limb will appear pale due to intense arterial spasm in the distal bed. As the spasm decreases over the next 1 to 2 hours, the skin appears purple with a fine, reticular pattern, and will blanch on applying pressure (livedo reticularis). This is indicative of a still viable limb. As time progresses, the stagnant blood clots giving the skin a dusky mottled appearance with a coarse pattern that will not blanch with applying pressure. In the late stages of ischemia, there will be areas of fixed staining which is indicative of vessel disruption and blood extravasation and may progress to blistering and liquefaction. The limb is usually not salvageable at this stage.

Poikilothermia: due to intense vasospasm and reduced/absent distal flow, the affected limb will appear cool to touch. The proximal extent of this is usually one level below the level of occlusion and serial assessment helps to monitor progression of ischemia.

Paresthesia: onset of neurological signs is a hallmark of a threatened limb. The severity of symptoms can help differentiate a threatened limb from a nonviable limb. This helps decide on timing 11 and choice of revascularization strategy. Symptoms can vary from loss of fine touch and proprioception (over the dorsum of the foot) in the initial hours to complete anesthesia of the affected extremity with limb-threatening ischemia.

Paralysis: paralysis (loss of motor function) usually occurs approximately 6 to 8 hours after onset of ischemia and, if severe, indicates low likelihood for limb salvage with urgent interventions. Inability to dorsiflex and plantar flex the foot is suggestive of a more proximal site of occlusion as compared with one's inability to move the toes. As stated earlier, irreversible muscle necrosis sets in 4 to 6 hours after abrupt occlusion and usually denotes nonsalvageable limb.

Clinical Classification

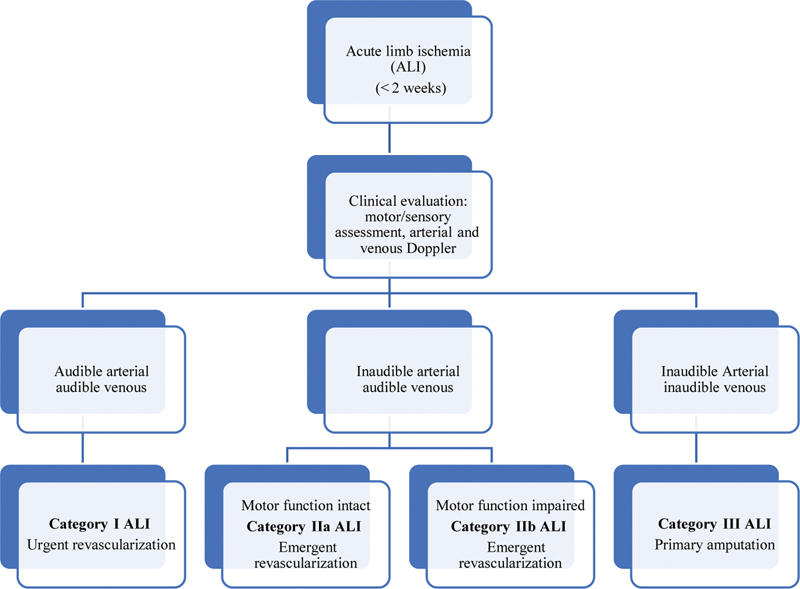

The clinical classification for ALI as proposed by Rutherford et al 12 and subsequently adopted by the Society of Vascular Surgery and International Society of Cardiovascular Surgery, takes into consideration the clinical findings such as sensory and muscle weakness and the Doppler indices of the arterial and venous systems. This classification helps to determine urgency, prognosticate success of limb salvage and guide decision making in terms of therapy ( Table 2 ). Broadly, category I refers to viable limbs that are not immediately threatened. Category II refers to threatened limbs and is further subclassified into category IIa, “marginally” threatened and salvageable limbs, if promptly treated and category IIb, “immediately” threatened limbs that require immediate revascularization if salvage is to be accomplished. Category III is irreversibly damaged limbs in which case resulting in major tissue loss or permanent nerve damage is inevitable.

Table 2. Rutherford clinical classification of severity of acute limb ischemia.

| Category | Description | Clinical findings | Doppler signals | Prognosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensory loss | Muscle weakness | Arterial | Venous | |||

| I | Viable | None | None | Audible | Audible | Not immediately threatened, can attempt revascularization |

| II | Threatened | |||||

| IIa | Marginally threatened | Minimal (toes) or none | None | Often inaudible | Audible | Salvageable with prompt revascularization |

| IIb | Immediately threatened | More than toes, associated with rest pain | Mild or moderate | Usually inaudible | Audible | Salvage with immediate revascularization |

| III | Irreversible | Profound, anesthetic | Profound, paralysis (rigor) | Inaudible | Inaudible | Major tissue loss or permanent nerve damage inevitable, consider amputation |

Diagnosis

Clinical evaluation trumps diagnostic imaging in the setting of ALI and vascular imaging should be sought only in cases where limb viability is not immediately threatened. 9 10

Diagnostic Exams

Duplex ultrasound : this is usually the first-choice imaging modality given its ease of use, ready availability, absence of radiation risk, and almost 100% sensitivity to detect vessel occlusion. It helps to identify the level, severity (incomplete vs. complete occlusion), and chronicity of occlusion (loss of echogenicity and continuous systolic/diastolic downstream flow are noted in older lesions with collaterals). It can also provide clues to underlying etiology with embolic phenomena appearing as a discrete, rounded lesion in the lumen of a nondiseased artery versus thrombosis which would show evidence for atherosclerosis in the vessel wall. Additionally, venous duplex helps to stage the severity of ischemic limb injury. Despite its advantages in evaluating distal outflow vessels, they may be less accurate in evaluating inflow disease (aortic and iliac vessels) and imaging can be generally limited by body habitus.

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) : CTA can provide high-quality images in a time-sensitive manner. Particularly, it has excellent sensitivity (91–100%) and specificity (93–96%) 10 to detect significant aortoiliac lesions. Advantages are ability to obtain three-dimensional reconstructed images that can reliably identify length, location, and anatomy of the lesions and assess collateral circulation. CTA can also identify prior stents, bypass grafts, and presence of calcified segments which can aid in deciding on site of anastomosis during surgical planning. Disadvantages include use of iodinated contrast which might be an issue in patients with iodine allergy and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) : although gadolinium-enhanced MRA has sensitivity and specificity of 93 to 100% 9 when compared with invasive angiography, this is less preferred especially in the setting of ALI due to longer acquisition times, poor availability and lower image quality compared with CTA. MRA cannot help detect the presence of calcification in the vessels. Further disadvantages include tendency to induce claustrophobia in some patients and contraindications in patients with pacemakers and advanced CKD (Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) < 30 mg/kg/min).

Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) : although invasive and requires operators with vascular expertise, catheter-based DSA is considered as the “gold standard” modality and offers the advantage of simultaneous revascularization in the form of thrombolysis or angioplasty. This is the modality of choice in patients with immediately threatened limb and should not be delayed by pursuing noninvasive techniques first. The risk for radiation is higher when compared with CTA and it also carries a significant iatrogenic risk for vascular complications.

Complementary Tests

Laboratory tests: complete blood counts, blood type and screen, arterial blood gases (to detect systemic acidosis), markers of muscle injury (lactate dehydrogenase, creatinine phosphokinase and aminotransferases), electrolytes, and renal function.

Electrocardiogram: it helps to detect occult arrhythmias such as undiagnosed atrial fibrillation.

Echocardiogram: this is to evaluate for other cardiac sources of emboli in suspected thromboembolism.

Management

As soon as diagnosis of ALI is established, systemic heparin for anticoagulation and pain management should be initiated. Standard precautions and dosing regimen for systemic anticoagulation with heparin should be followed. If heparin-induced thrombocytopenia is suspected then direct thrombin inhibitors may be used. The therapeutic strategy will depend on type of occlusion (thrombus or embolus), location, type of conduit (artery of graft), Rutherford's class, duration of ischemia, comorbidities, and therapy-related risks and outcomes. 9 Fig. 1 outlines initial assessment and recommended revascularization strategies as endorsed by professional societies. In general, recommended treatment strategies based on viability are as listed as follows:

Fig. 1.

Diagnosis and management of acute limb ischemia.

Category-I ALI: goal is to revascularize urgently, that is, in 6 to 24 hours. In this situation, generally it is possible to obtain vascular imaging with ultrasound (US), CT, or digital subtraction angiography (DSA). Since no neurological deficit is present in these cases, catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT) is an attractive option.

Category-IIa and -IIb ALI: goal is to revascularize emergently, that is, in less than 6 hours. Surgical thrombectomy and bypass are generally considered; however, CDT remains a less-invasive option particularly in category IIa if local expertise is available and/or in the setting of a recent occlusion, thrombosis of synthetic grafts, and stent thrombosis. 13

Category-III ALI: amputation is required. Delayed attempts at revascularizing a nonviable limb can run the risk of reperfusion injury, compartment syndrome, and multiorgan failure.

Techniques

Catheter Directed Thrombolysis

Standard precautions and contraindications for thrombolytics are to be considered prior to initiation. Ultrasound guided arterial access should be obtained to minimize vessel trauma. Using a catheter with multiple side holes, a bolus dose of 2 to 4 mg tPA is generally given in the cath laboratory followed by a continuous infusion of 0.5 to 1 mg/hour. Concurrent systemic heparin is given at 500 U/hour at a fixed dose. Serial assessment of complete blood counts and fibrinogen should be obtained in every 6 hours. Patients should be closely monitored in the intensive care unit by trained staff looking out for worsening ischemia or any bleeding complications. Patients should be reassessed in the cath laboratory in 18 to 36 hours to determine the need for additional endovascular or open surgical treatment. It is important to note that systemic thrombolysis has no role in ALI.

Open Embolectomy

An open embolectomy offers simple, rapid removal of soft, fresh emboli, and thrombi from the arterial system. A single arteriotomy followed by use of Fogarty's balloon catheter 14 can be performed under local anesthesia as well. For extracting thrombus that is too resistant for an elastomeric balloon, there are corkscrew design catheters that increase the surface area for entrapping fibrous material. The over-the-wire Fogarty Thru-Lumen embolectomy catheter offers expanded capabilities that can be applied to traditional techniques.

Percutaneous Mechanical Thrombectomy

Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy (PMT) may provide stand-alone therapy for ALI or, more commonly, is used in combination with thrombolytic therapy. 15 It may also be indicated in patients with contraindications to thrombolysis and with high surgical risk. It is accomplished with the introduction of a pressurized saline jet stream through the directed orifices in the catheter distal tip. The jets generate a localized low-pressure zone via the Bernoulli effect which entrains and macerates thrombus. The saline and clot particles are then sucked back into the exhaust lumen of the catheter and out of the body for disposal.

Other Endovascular Techniques

Techniques such as site-specific (isolated) pharmacomechanical thrombolysis–thrombectomy can be used due to its site‐specific nature and limited thrombolysis exposure time. 16 Ultrasound accelerated thrombolysis has been proposed to reduce the thrombolysis time. 17 Mechanical thromboaspiration using the Penumbra system offers a rapid, effective approach to address intraprocedural foot embolization and avoid possible grave clinical sequelae. 18

Surgical Bypass

Thrombotic occlusion usually occurs in patients with a chronically diseased vascular segment. In such cases, correction of the underlying arterial abnormality is critical. After removal of the clot, intraoperative angiography is performed to confirm that the thrombectomy is complete and to guide subsequent treatment if there is persistent inflow or outflow obstruction. 19 If thrombectomy is not successful or if there is residual significant disease, then a bypass grafting or adjuncts, such as endarterectomy, patch angioplasty, and intraoperative thrombolysis, may become necessary. The surgical approach is also preferred in patients with ischemic symptoms for over 2 weeks.

Postprocedure Follow-up

Reperfusion of acutely ischemic lower extremity can result in cellular edema and swelling of lower extremity muscle compartments. A compartment pressure of >30 mm Hg is diagnostic of compartment syndrome and warrants fasciotomy. Fasciotomy could be considered in patients with category-IIb ischemia if time to revascularization is more than 4 hours. 8

Patients with underlying atherosclerotic risk markers should be placed on aspirin and statins if there are no contraindications. Long-term anticoagulation should be considered in patients with hypercoagulable states including atrial fibrillation.

Literature Review

Ouriel et al, Rochester trial 1994

Patients with ALI less than 7 days' duration were randomly assigned to intra-arterial catheter-directed urokinase therapy or operative intervention. Intra-arterial thrombolytic therapy was associated with a reduction in the incidence of in-hospital cardiopulmonary complications and a corresponding increase in patient survival rates. 20

The STILE trial 1994

In this prospective randomized trial, authors compared either optimal surgical procedure or intra-arterial, catheter-directed thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) or urokinase (UK). Patients with acute ischemia (0–14 days) who were treated with thrombolysis had improved amputation-free survival and shorter hospital stays. However, for patients with chronic ischemia (> 14 days), surgical revascularization was more effective and safer than thrombolysis. There was no difference in efficacy or safety between rt-PA and UK. 21

Comerota et al 1996

In this randomized trial, authors compared surgical revascularization ( n = 46) with catheter-directed thrombolysis ( n = 78) in patients with occluded lower extremity bypass grafts. In patients with acute limb ischemia (<14 days), successful thrombolysis of occluded lower extremity bypass grafts improved limb salvage and reduced the magnitude of the planned surgical procedure. 13

TOPAS Trial 1998

In this randomized, multicenter trial, authors compared vascular surgery (e.g., thrombectomy or bypass surgery) with thrombolysis by catheter-directed intra-arterial recombinant urokinase (272 per group) in patients with ALI of <2 weeks in duration. Despite its association with a higher frequency of hemorrhagic complications, intra-arterial infusion of urokinase reduced the need for open surgical procedures, with no significantly increased risk of amputation or death. 22

NATALI Database 2004

This was a retrospective review of 1,133 ALI episodes treated with CDT. At 30 days, amputation-free survival was 75.2%, amputation rate was 12.4%, and mortality was 12.4%. 23

Taha et al 2015

A more contemporary retrospective review in which 147 consecutive patients with ALI treated with endovascular revascularization (ER) were compared with 296 patients with open revascularization (OR). In patients with class-II ALI, ER, or surgical OR resulted in comparable limb salvage rates. Overall mortality rates were significantly higher at 30 days and 1 year in the OR group. 24

Outcomes/Prognosis

ALI is a malignant disease with a high morbidity and mortality rate. The limb will tolerate 4 to 6 hours of ischemia. The earlier the diagnosis is made and promptly treated, the higher the chance of limb salvage. The 30-day amputation free survival stratified by severity of ischemia is 100% for the viable limb, 79.5% for threatened, and 4.8% for irreversible ischemia. 25 The 5-year amputation free survival is 36.7% and overall survival is 55.9%.

Future Directions

The cellular effects of thrombin are mediated via the protease activated receptors (PAR) that are present on platelets and endothelium. Thrombin signaling in platelets contributes to thrombosis and hemostasis. Endothelial PARs participate in the regulation of vascular tone and permeability. Vorapaxar, a thrombin receptor (PAR1) antagonist, reduced first ALI events by 41%. 26 A novel hydrogen sulfide prodrug has been shown to promote peripheral revascularization in a miniswine model of ALI. 27 Further research is needed in this field to mitigate the morbid events associated with ALI.

Conclusion

ALI is a potentially catastrophic condition that can proceed rapidly to limb loss, if not diagnosed and treated promptly. Sensory and motor findings coupled with arterial and venous Doppler signals determine the clinical viability of the involved limb. Early intervention leads to higher success in limb salvage. Initial treatment of ALI with endovascular therapy should be considered, if it is not contraindicated because of its equivalence in short-term outcomes, such as limb salvage and amputation-free survival, and lower morbidity and mortality rates, although there may be a higher need for future interventions. 28 Using CDT, complete or partial thrombus resolution, with a satisfactory clinical result, occurs in 75 to 92% of ALI patients with occluded native vessel, stent, or graft. 22 Definitive surgical revascularization could be considered once patients are clinically optimized. Public campaigns to raise awareness of the need for early revascularization may be the key to more limb salvage.

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Disclosures

None of the authors have any disclosures relevant to the content of this manuscript.

Both authors contributed equally to the manuscript.

References

- 1.Lau J F, Weinberg M D, Olin J W. Peripheral artery disease. Part 1: clinical evaluation and noninvasive diagnosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8(07):405–418. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hess C N, Huang Z, Patel M R. Acute limb ischemia in peripheral artery disease. Circulation. 2019;140(07):556–565. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.039773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Creager M A, Kaufman J A, Conte M S. Clinical practice. Acute limb ischemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(23):2198–2206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1006054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hess C N, Rogers R K, Wang T Y. Major adverse limb events and 1-year outcomes after peripheral artery revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(09):999–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Connell J B, Quiñones-Baldrich W J. Proper evaluation and management of acute embolic versus thrombotic limb ischemia. Semin Vasc Surg. 2009;22(01):10–16. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santistevan J R. Acute limb ischemia: an emergency medicine approach. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2017;35(04):889–909. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callum K, Bradbury A.ABC of arterial and venous disease: Acute limb ischaemia BMJ 2000320(7237):764–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerhard-Herman M D, Gornik H L, Barrett C. 2016 AHA/ACC Guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135(12):e686–e725. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olinic D-M, Stanek A, Tătaru D-A, Homorodean C, Olinic M. Acute Limb Ischemia: An Update on Diagnosis and Management. J Clin Med. 2019;8(08):1215. doi: 10.3390/jcm8081215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dieter R, Dieter R A, III, Dieter R A, III, Nanjundappa A. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017. Critical Limb Ischemia Acute and Chronic. [Google Scholar]

- 11.ESC Scientific Document Group . Aboyans V, Ricco J-B, Bartelink M EL. 2017 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial diseases, in collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS): document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteries endorsed by: the European Stroke Organization (ESO)The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) Eur Heart J. 2018;39(09):763–816. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rutherford R B, Baker J D, Ernst C. Recommended standards for reports dealing with lower extremity ischemia: revised version. J Vasc Surg. 1997;26(03):517–538. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(97)70045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Comerota A J, Weaver F A, Hosking J D. Results of a prospective, randomized trial of surgery versus thrombolysis for occluded lower extremity bypass grafts. Am J Surg. 1996;172(02):105–112. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(96)00129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fogarty T J, Cranley J J, Krause R J, Strasser E S, Hafner C D. A method for extraction of arterial emboli and thrombi. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1963;116:241–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ansel G M, Botti C F, Jr, Silver M J. Treatment of acute limb ischemia with a percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy-based endovascular approach: 5-year limb salvage and survival results from a single center series. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;72(03):325–330. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta R, Hennebry T A. Percutaneous isolated pharmaco-mechanical thrombolysis-thrombectomy system for the management of acute arterial limb ischemia: 30-day results from a single-center experience. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;80(04):636–643. doi: 10.1002/ccd.24283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schrijver A M, van Leersum M, Fioole B. Dutch randomized trial comparing standard catheter-directed thrombolysis and ultrasound-accelerated thrombolysis for arterial thromboembolic infrainguinal disease (DUET) J Endovasc Ther. 2015;22(01):87–95. doi: 10.1177/1526602814566578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gandini R, Merolla S, Chegai F, Del Giudice C, Stefanini M, Pampana E. Foot embolization during limb salvage procedures in critical limb ischemia patients successfully managed with mechanical thromboaspiration: a technical note. J Endovasc Ther. 2015;22(04):558–563. doi: 10.1177/1526602815589955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Acar R D, Sahin M, Kirma C. One of the most urgent vascular circumstances: Acute limb ischemia. SAGE Open Med. 2013;1:2.05031211351611E15. doi: 10.1177/2050312113516110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ouriel K, Shortell C K, DeWeese J A. A comparison of thrombolytic therapy with operative revascularization in the initial treatment of acute peripheral arterial ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 1994;19(06):1021–1030. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(94)70214-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Results of a prospective randomized trial evaluating surgery versus thrombolysis for ischemia of the lower extremity. The STILE trial Ann Surg 199422003251–266., discussion 266–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thrombolysis or Peripheral Arterial Surgery (TOPAS) Investigators . Ouriel K, Veith F J, Sasahara A A. A comparison of recombinant urokinase with vascular surgery as initial treatment for acute arterial occlusion of the legs. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(16):1105–1111. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804163381603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Earnshaw J J, Whitman B, Foy C. National Audit of Thrombolysis for Acute Leg Ischemia (NATALI): clinical factors associated with early outcome. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39(05):1018–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taha A G, Byrne R M, Avgerinos E D, Marone L K, Makaroun M S, Chaer R A. Comparative effectiveness of endovascular versus surgical revascularization for acute lower extremity ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61(01):147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.06.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oxford Vascular Study . Howard D P, Banerjee A, Fairhead J F, Hands L, Silver L E, Rothwell P M. Population-based study of incidence, risk factors, outcome, and prognosis of ischemic peripheral arterial events: implications for prevention. Circulation. 2015;132(19):1805–1815. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonaca M P, Gutierrez J A, Creager M A. Acute limb ischemia and outcomes with vorapaxar in patients with peripheral artery disease: results from the trial to assess the effects of vorapaxar in preventing heart attack and stroke in patients with atherosclerosis-thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 50 (TRA2°P-TIMI 50) Circulation. 2016;133(10):997–1005. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rushing A M, Donnarumma E, Polhemus D J. Effects of a novel hydrogen sulfide prodrug in a porcine model of acute limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2019;69(06):1924–1935. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2018.08.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J C, Kim A H, Kashyap V S. Open surgical or endovascular revascularization for acute limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2016;63(01):270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]