Abstract

Scholars and policy-makers agree that cross-border and multi-sector cooperation are essential components of coordinated efforts to contain the spread of COVID-19 infections. This paper examines the responses of ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nation) member countries to the COVID-19 pandemic, including the limits of regional cooperation. ASEAN has pre-existing cooperative frameworks in place, including regional health security measures, which, at least theoretically, could assist the region's efforts to formulate cooperative responses to containing a global pandemic. With its overarching “One Vision, One Identity, One Community”, ASEAN cooperation has extended to include region-wide disaster responses, framed as “One Asean, One Response”. Using content analysis, this paper examines media statements and policies from ASEAN member states and the ASEAN Secretariat to assess the collective response to COVID-19 during the period from January to August 2020. By identifying gaps and opportunities in government responses to COVID-19 as the virus spread throughout Southeast Asia, this paper provides new insights as well as recommendations for the future.

Keywords: COVID-19, ASEAN, Pandemic, Policy, Disasters, Health, Regional cooperation, Health system resilience

1. Introduction

Since 11th March 2020, when the World Health Organization (WHO) defined the new coronavirus (COVID-19) as a global pandemic, the virus has infected 23.3 million people and killed 741,000 across 210 countries. In Southeast Asia, in October 17 ASEAN member countries have confirmed at least 869,515 cases and 21,076 deaths, although this figure is undoubtedly considerably higher due to the large number of unreported or undiagnosed cases, especially in developing countries with fragile medical systems. As of August 2020, Indonesia has the highest fatality ratio as a percentage of its population (4.56), while Singapore has the lowest death rate in the region (0.05) (ABVC 2020).

COVID-19 responses undertaken by individual member countries of ASEAN have been tremendously diverse and have ranged from strict lockdown conditions in the highly regulated city-state of Singapore to ‘business as usual’, especially in rural areas of developing countries with large informal economies such as Laos and Myanmar. Yet ASEAN member countries also have a long history of cross-border cooperation, forged through trade regionalization and economic integration. In the health sector, ASEAN cooperation has been infused into region-wide frameworks including the ASEAN Political-Security Community (APC), ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) and ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community (ASCC) [1]. Through these social-cultural pillars, ASEAN has developed a basic platform for health security cooperation since 1980 [2], as shown, for instance, through ASEAN-level responses to prior pandemics including SARS, H1N1 and MERS-CoV3.

Currently, the official ASEAN health cooperation platform that includes its pandemic response planning regime is governed by the ASCC Pillar entitled “A Healthy, Caring and Sustainable ASEAN Community”. This vision of the ASEAN Post-2015 Health Development Agenda was formulated in 2018 as one of the ASEAN agendas for pandemic preparedness [2]. It is articulated in the Joint Statement of 5th ASEAN Plus Three Health Ministers Meeting [2].

Table 1 provides an overview of existing ASEAN mechanisms concerning health security coordination and cooperation mechanisms ranging from SARS to H1N1, and, most recently, COVID-19. In formulating a coordinated COVID-19 response, four relevant mechanisms are in place under the ASCC framework [4]. Although these mechanisms could potentially serve as the basis for region-wide cooperation, they have not been enacted or operationalized in any meaningful way during the first five months of the Covid-19 as individual countries that were initially overwhelmed by the pace of viral transmission subsequently struggled to deal with its destructive social, economic and health consequences within their national borders. (See Fig. 1 .)

Table 1.

ASEAN Health Cooperation on Epidemic Preparedness: 2003–2020.

| Timeline | Forms of cooperation |

|---|---|

| 2003–2009 SARS and H1N1 |

|

| 2010–2019 Broader health risks |

|

| 2020 onwards |

|

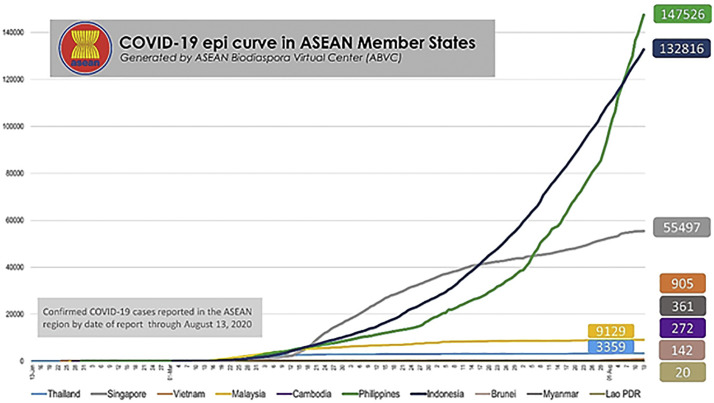

Fig. 1.

Covid-19 epi curve confirmed cases.

(Source: ASEAN Biodiaspora Virtual Center 2020, p. 10].

The aim of this article is to document and analyze individual and collective responses to COVID-19 by ASEAN member states in the period from January 2020 through to August 2020. We argue while pre-existing regional health cooperation forums and platforms have not been effectively mobilized during this intensely disruptive phase of the pandemic, they could potentially serve as a foundation for enacting more coordinated region-wide activities to deal with the cumulative impacts of COVID-19 and to navigate the ‘new normal’ for individual member countries and the region in the short to medium term. Drawing from secondary sources (policy reports, media content and journal articles), the overall objectives of the paper are threefold. First, it seeks to understand the impacts of COVID-19 at the ASEAN level and to analyze the potential for region-wide coordination through the mobilization of the existing health security cooperation framework. Second, the paper examines how existing frameworks facilitate or impede the adoption of a coordinated COVID-19 response. Third, we identify lessons and insights from ASEAN regional health systems for collaborative disaster response strategies in the context of COVID-19.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 1 examines the health and social impacts of Covid-19 on ASEAN member countries. Regional-level frameworks are analyzed in Section 2 to document key health-responses responses that are available and which could potentially be mobilized and coordinated by ASEAN. Section 3 identifies health, social and economic responses to the pandemic taken by the ten member countries of ASEAN. In Section 4, using policy matrix approach, we examine and compare these mechanisms and responses. We conclude by evaluating the relative resilience of ASEAN's health frameworks and where it could be strengthened to enhance the efficacy of region-wide responses to pandemics and other disasters in Section 5.

2. Impacts on ASEAN countries

Before Covid-19 ushered in a global recession in the second quarter of 2020, Southeast Asia ranked among the most rapidly developing, industrializing and urbanizing parts of the world. This context of unabated growth also created new spatial inequalities (for example, urban slums, unsafe planning and inequities in resource distribution systems) that incubated conditions of social vulnerability and economic precarity, which, in the Covid-19 pandemic, translated into heightened health risks [5]. Of Southeast Asia's total population of 649 million people, 218 million workers are in the informal sector and therefore lack access to health benefits, work visas and wage security [6].Under pandemic conditions of hardened national borders and various lockdown restrictions on movement within and between nation-states, these lived forms of socioeconomic precarity have translated into dwindling remittance economies and food and health insecurity for millions of people across Southeast Asia.

The full consequences of the pandemic recession on the national economies of Southeast Asia remain unknown and largely unanticipated. In the first half of 2020, regional growth contracted sharply to 0.5%, the lowest rate since 1967 [7]. At the time of writing in August 2020, regional outlooks for employment recovery remain bleak and prolonged periods of financial stress are predicted in most sectors, with notable exceptions in niche sectors such as e-commerce. Mounting national debt, trade restrictions and disrupted supply chains are also placing unprecedented burdens on already weak healthcare systems in developing countries across Southeast Asia. Under these conditions where national governments face mounting pressure to re-open economically, second waves of the pandemic are emerging as populations return to work. While highly regulated countries such as Singapore have been able to re-open businesses without a second outbreak, Indonesian and the Philippines are still on the brink of a first wave of Covid-19 and Laos and Myanmar conduct business as usual amidst sporadic testing and critically under-prepared health systems.

2.1. ASEAN health sector efforts to Covid-19

With the impacts of Covid-19 threatening human health and social security across the region, ASEAN as a regional body has a potentially important role to play in coordinating the responses of member states to contain the spread of the virus and to build awareness of the importance of treating Covid-19 as a transboundary problem that cannot be resolved by individual sectors, jurisdictions or groups of experts and requires collective forms of policy redress.

To the limited degree that Covid-19 has been treated as a collective problem, ASEAN-level responses have thus far been limited to communication exchanges and information-sharing among member states on infection statistics and response updates. Coordinated efforts and collective action are needed to prevent and eliminate the spread of subsequent waves of the pandemic and to provide financial and technical assistance to member states that lack adequate health facilities, services and expertise. Table 2 summarizes the timeline of key responses.

Table 2.

Key timeline of ASEAN responses to Covid-19 (Source: Authors, compiled from ASEAN, 2020b).

| Date | Responses |

|---|---|

| 31 Dec 2019 | First Covid-19 case was announced in Wuhan, China |

| 19 February 2020 | Joint statement of ASEAN Defense Ministers on Defense Cooperation against Disease Outbreak, from meeting in Viet Nam |

| 20 February 2020 | The ASEAN Coordinating Council (ACC) held a Special Meeting on 20 February 2020 in Vientiane, Lao PDR to discuss follow-up actions to the ASEAN Chairman's Statement on ASEAN collective response to the Covid-19 |

| 9 March 2020 | ASEAN health sector sustains cooperation in responding to Covid-19 |

| 10 March 2020 | Strengthening ASEAN'S Economic Resilience in Response to The Outbreak of The Coronavirus Disease |

| 13 March 2020 | ASEAN senior health officials enhance regional collective actions against Covid-19 pandemic |

| 7 April 2020 | Joint Statement Special Video Conference of ASEAN Plus Three Health Ministers in Enhancing Cooperation on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid-19) Response |

| 9 April 2020 | Joint Statement Special Video Conference of The ASEAN Health Ministers in Enhancing Cooperation on Covid-19 Response |

| 10 April 2020 | ASEAN Ministers Endorse New Covid-19 Response Fund Policy Brief on the Economic Impact of Covid-19 Outbreak on ASEAN released |

| 13 April 2020 | Joint Statement Special Video Conference of ASEAN Plus Three Health Ministers in Enhancing Cooperation on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid-19) Response |

| 14 April 2020 | Declaration of the special ASEAN summit on Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| A series of ASEAN and other countries activities | |

| 17 April 2020 | ASEAN, Italian health experts exchange experiences in combating Covid-19 |

| 21 April 2020 | China donates medical supplies to ASEAN Secretariat for Covid-19 prevention |

| 22 April 2020 | ASEAN – Japan Economic Ministers' Joint Statement on Initiatives on Economic Resilience in Response to the Corona Virus Disease (Covid-19) Outbreak |

| 23 April 2020 | Co-Chairs' Statement of the Special ASEAN-United States Foreign Ministers' Meeting on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid-19) |

| 24 April 2020 | ASEAN, China reaffirm commitment to forge closer cooperation |

| 29 July 2020 | ASEAN-Australia Health Experts' Meeting on Covid-19 |

ASEAN Vision 2025 on Disaster Management highlights the importance of communication exchanges in the form of information sharing and pooling resources between key stakeholders. Since the official outbreak of Covid-19 in China, ASEAN Emergency Operations Centre Network for public health emergencies (ASEAN EOC Network), led by Malaysia, has taken the initiative of sharing daily situational updates on disease spread and progression. The ASEAN EOC Network led by Malaysia's Ministry of Health provides a publicly available platform for use by ASEAN member countries working in crisis and disease prevention centers to communicate and share information in a timely manner. A WhatsApp mobile application has been established for this specific purpose. EOC network also produces and compiles data on National/local Hotline/Call Centers in ASEAN member countries for public dissemination and to raise social awareness of disease hotspots and best practices for prevention and containment. Complementing these efforts, the ASEAN Bio Diasporas Regional Virtual Centre (ABVC) for big data analytics and visualization has provided update reports on national risk assessments, readiness and response planning efforts. ASEAN publishes Risk assessment reports for international dissemination of Covid-19 information to highlight responses and provide an overview of cases and deaths in ASEAN countries.

Although individual countries have taken very different approaches to dealing with the pandemic, ASEAN officials have tried to coordinate communication exchanges in a series of international online meetings. For instance, in April 2020, the ASEAN Health Minister (AHHM) convened a video conference among member states (chaired by Indonesia's Health Minister) aimed at intensifying regional cooperation with various stakeholders and stepping up measures to mitigate the spread of infections between countries. At the meeting, national delegates reached agreement on the need to: (1) strengthen regional cooperation on risk communication to avert misinformation and the dissemination of fake news; (2) continue sharing information, research and studies in an open, real-time and transparent manner; (3) coordinate cross-border health responses by scaling-up the use of digital technology and artificial intelligence for efficient information exchanges; and (4) institutionalize preparedness, surveillance, prevention, detection and response mechanisms of ASEAN member countries with global partners.

The success of these efforts is impossible to gauge in the current context of rapidly changing conditions and closed national borders. The hardening of state boundaries and restricted movements has also made national-level responses more tangible and readily discernible than international diplomatic efforts. Moreover, further planned actions by ASEAN leaders have not had time to be properly implemented, assessed and documented, such as the establishment of a Covid-19 ASEAN Response Fund to boost emergency stockpiles for future outbreaks. Although ASEAN has invited ASEAN Plus 3 (Japan, South Korea and China) to contribute to this fund, disrupted supply chains and subdued capital flows have at least temporarily impeded the procurement of certain medical supplies and equipment for distribution in countries with fragile health care systems.

Nonetheless, efforts are ongoing to strengthen ASEAN's collaborative capacities. Ratified on 14 April 2020, the 2019 Declaration of the Special ASEAN summit on Coronavirus Disease outlined seven key measures that have been agreed upon by member countries as a basis for strengthening future forms of cross-border cooperation. These measures include: (1) further strengthening public health cooperation measures to contain the pandemic and protect the people; (2) preserving supply chain connectivity; (3) cultivating multi-stakeholder, multi-sectoral, and comprehensive approaches to effectively respond to Covid-19 and future public health emergencies; (4) collectively mitigating the socioeconomic impacts of the pandemic while safeguarding public well-being as a basis for (political) stability; (5) enhancing the transparent and public dissemination of important health and safety information via mixed media platforms; (6) providing appropriate assistance to support pandemic-affected nationals of ASEAN countries in third countries; and (7) reallocating existing available funds to support the establishment of the Covid-19 ASEAN Response Fund. By August 2020, however, a United Nations report found that poor internet connectivity (55% of Southeast Asia's population lacks regular internet access) and weak health systems remain critical obstacles to effectively dealing with Covid-19, with the World Health Organization ranking Southeast Asia's universal health coverage on a median index of just 61 out of 100 [8].

3. Country specific responses

This section maps the divergent government responses taken by individual ASEAN member countries. Not only is country-based mitigation vital as the first line of defense against Covid-19 [3], but in the context of border closures, travel restrictions and trade disruptions, states have been compelled to take a more proactive stance in public health and services, representing a reversal of the trend toward rolling back state power in the restructuring of governments along market lines. As such, pre-existing public health expenditure combined with the extent to which individual governments have undertaken contact tracing and testing and enforced quarantine measures have shaped highly differential health outcomes within and between countries.

3.1. Brunei Darussalam

Brunei is a tiny country with the population around 436,647 has emerged as good example of a country that provides care, concern, and preparedness not only to its citizens but also to foreign and tourist. The handling of the pandemic by the Sultan Bolkiah has been argued as transparent and robust. The first case was declared on 9 March 2020. Brunei has successfully contained the virus in small number cases compared to the other ASEAN countries. It recorded 138 cases and on 6 April no new cases emerged. Brunei has taken necessary steps to contain the virus, including early massive testing since January 2020. travel bans for citizens to go abroad on March 15 [9]. All Bruneians returning to the country undergo mandatory isolation at quarantine facilities [9]. Brunei has entirely implemented lockdown and closed its access from sea, air on March 24 [10]. Restrictions of public gathering, work from home, mosque and other worship places has been closed. The government also took measures to ensure the welfare of its citizens. The Ministry has issued a directive to all employers to pay salaries during the quarantine to its employees. On April 1, it introduced economic stimulus for micro, small and medium enterprises for BND250 million (Star.com.2020). The success of Brunei in containing the virus is early action and implemented precautionary measures and deploy and mobilize all funding and resources to ease the impact of the pandemic. Brunei has started to ease stringent travel restriction on September 15. In addition, foreign nationals have allowed to enter Brunei since September 15 for essential travel.

3.2. Cambodia

The population of Cambodia is around 16 million people. The first confirmed cases of coronavirus in Cambodia has been reported on 27 January 2020 [11]. The country has confirmed 122 cases of Covid-19 so far and no deaths have been reported [12]. No new cases were reported in Cambodia for twelve consecutive days [12]. Despite this situation Cambodia Prime Minister urged people to remain vigilant as there is no medicine to cure this infectious disease [13]. Cambodia has lowest confirmed cases compared to other ASEAN countries despite criticism of lack testing [13]. Several measures that have been adopted by The Royal government of Cambodia include imposed quarantine, cancel the celebrations of the Khmer New Year, issued economic stimulus [14]. In addition, the government also passed state of emergency law on 10 April 2020 granting the country's autocratic leader, Hun Sen, vast new powers allowing the government to carry out unlimited surveillance of telecommunications and to control the press and social media [15]. Human rights experts argued that this law expected to weaken democracy right in the country. Cambodia has successfully contained the virus as an early August has zero deaths. In October Cambodia reported 2 new imported cases with total 280 since the outbreak [16].

3.3. Indonesia

Indonesia is the most populous country among ASEAN members with 272 million people. The risk in suffering most due to the coronavirus pandemic is amounting as the quality of health infrastructure has been inadequate. This is shown by the number cases continues to rise and second in the region after Singapore and the mortality rate of 8,9 to 9% is one of the highest in the Southeast Asia and the world [3,17]. Confirmed first cases of coronavirus in Indonesia has been announced by Jokowi in 2 of March 2020 after denied the study from Harvard Marc Lipstich about the possibility of Covid-19 should have been detected in Indonesia before this announcement. As of September 25, 2020, the number of confirmed Covid-19 positive cases has risen by 4823 from the previous day to 266,845 cases. In that same period, the number of deaths rose by 113 to 10,218, while the number of recovered patients rose by 4343 to 196,196 (Covid 19.go.id).

Detailed analysis on Covid-19 response in Indonesia have been recently published by Djalante et al.18. Several key measures have been issued to respond to the coronavirus cases in Indonesia include: The establishment of Task force for the acceleration of Covid-19 on 13 March 2020 [19,20]. Large scale social restriction for accelerating Covid-19 eradication on 30 March 2020. Recent suspension of travels between cities by air, land and water [18]. In addition, the government has decided to implement a travel ban for foreign visitors to Indonesia including transit since 2 April 2020 through the Ministry of Law and Human Rights No 11/2020 on temporary travel bans for foreigners who enter Indonesia territory. On 31 March 2020, 405 trillion Rupiah (USD 26,4 trillion) stimulus package was announced by government regulation in lieu of law (Perppu) No 1/2020 to legitimize much more state spending and financial relief efforts as Indonesia's Covid-19 [21]. On 24 April 2020 Indonesia issued domestic travel restriction during Ramadhan period until 3rd of June.

Despite a rising cases Indonesia has started new normal and put less restriction in public at the end of June 2020 by allowing mall, workplaces to open. In middle of September Jakarta as one of Covid hotspot in Indonesia start to go back to adopt large social restriction as the cases continue to rise while other local regions remain in new normal situation. In addition, the government has prepared regulations out of which penalties may be imposed on those who violate health protocols. The penalties may be in the form of fines or social work [22]. Schools in yellow risk zones have been allowed to reopen under a revised joint decree issued by The Ministry of Education, The Ministry of Religious Affairs, the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Domestic Affairs issued mid-June. The Ministry of Education also issued a decree allowing school to use special curriculums to allow student to adjust with the current Covid-19 pandemic situation [23].

The Indonesian government has budgeted Rp 126.2 trillion in additional financial incentives to accelerate the National Economic Recovery (PEN) program. These incentives include more cash assistances for healthcare workers and the non-health sector to be made available up to December 2020 under a budget of Rp 23.3 trillion. Additionally, Rp 81.1 trillion had also been budgeted toward utilizing sectoral programs from the government's various ministries, institutions, as well as regional governments in order to provide productive assistance for micro, small and medium-sized enterprises at a nominal value of Rp 2.4 million per recipient, among other programs [24].

Indonesia has been ramping up the production of PCR tests. The state-owned pharmaceutical company Bio Farma is already capable of producing 50,000 PCR test tools per week, and has been given the order to increase the production capacity to 2 million PCR test tools per month [25]. Indonesia is also moving closer toward releasing a potential vaccine for Covid-19, with officials expecting a widespread public availability in the first quarter of 2021. This comes following the arrival of the potential Covid-19 vaccine developed by a China-based pharmaceutical company Sinovac, in cooperation with state-owned pharmaceutical company Bio Farma, which had entered into advanced clinical testing in Indonesia on Sunday, July 19 [26]. Indonesia has further secured a commitment of a supply of up to 340 million Covid-19 vaccines that are currently being developed by various pharmaceutical companies up until the end of 2021. This includes the commitment of 30 million Covid-19 vaccines secured as of the end of 2020, as well as up to 130 million in the first quarter of 2021, and then another commitment of 210 million from the second to fourth quarter of 2021 [27].

3.4. Lao People Democratic Republic (Lao PDR)

Lao PDR with a population over 7 million people is the last country in ASEAN infected by coronavirus. The first two cases of coronavirus were confirmed on 24 March 2020. The number of confirmed cases is only 19 and it is reported there are no new cases for 9 consecutive days on April 21 [28]. Key measures have been taken include [29,30]: established National Taskforce Committee for Covid-19 Prevention and Control - a special taskforce established on February 3, 2020; On March 29, 2020, the Prime Minister of Laos issued Order No. 06/PM on the Reinforcement of Measures for the Containment, Prevention, and Full Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic [31]. These orders have issued following measures such as closing some provincial borders, prohibition of gathering more than 10 people, price control, residential lockdown, and work from home for government officials. These measures have been implemented from March 30 to April 19, 2020. The Lao PDR government has already allocated LAK10 billion (USD 1,3 billion) for implementing measures to prevent and control the spread of Covid-19 in the country and other key fiscal, monetary and macroeconomic measures. On August 31, Lao PDR will continue to suspend the issuing of tourist visa for anyone traveling or transiting via countries where Covid - 19 outbreak is taking place [16]. People entering Laos must be sent to quarantine for 14 days. In adopting new normal, the government advise people to wash their hand with soap, practice social distancing and wear mask in public.

3.5. Malaysia

Malaysia with a population of around 31 million people has joined the list of countries with coronavirus when the first case was confirmed on 25 January 2020 [32]. Malaysia can maintain the confirmed cases low before sudden outbreak due to mass religious gathering attended by 16,000 people at the end of February 2020 [33]. Malaysia's nationwide response and collaboration can be a model for other countries to help flatten the curve of the Covid-19 pandemic [33]. The key measures include: on 13 March 2020, the government has banned all gatherings, including international meetings, sporting events, social and religious assemblies until 30th of April 2020 [34]. On 18 March 2020, the government decided to implement the Movement Control Order (MCO) until March 31 to address the Covid-19 outbreak under the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases Act 1988 and the Police Act 1967. Malaysian government launched a series of economic stimulus measures to lessen the impacts of Covid-19 to the sectors and communities. The Malaysian government announced a stimulus package worth RM20bn ($4.56bn) to enable the tourism and other industries in the country to deal with the impact of the coronavirus pandemic [33].A second stimulus package worth RM250bn ($58bn) was announced, out of which RM25bn (US$6bn) will be provided to help families and business owners affected by the outbreak. On 10 June 2020, Malaysia had relaxed the lockdown and entered Recovery Movement Order which allowing all social, educational, religious, business activities as well as economic sector reopened in phases [35]. On August 1 it's mandatory to use face mask in public. Recovery Movement Order has extended until 31 December 2020 with tourists still not allowed to enter the country. Malaysia will impose partial lockdown in four districts of Sabah after reporting 1000 cases in September. There is a concern that state wide election also will exacerbate the outbreak.

3.6. Myanmar

Myanmar's population currently stood around 54,336,457. Myanmar's first confirmed case was on 24 March 2020 [36]. Despite the confirmed cases being relatively small compared to other ASEAN countries, there is a fear of a major outbreak due to slow widespread testing in the country [37]. The United Nations has announced a plan to donate 50,000 testing kits to Myanmar, supplementing previous donations of 3000 from Singapore and 5000 from South Korea. The country is vulnerable, the public health system in Myanmar is woefully unsuited in response for a pandemic scale [38]. In addition, there is no safety net in Myanmar which causes the poor to be the most vulnerable groups in times of health and economic crisis as an impact of pandemic. The lockdown will hurt the livelihood and food security of the country [38]. Yangon imposed lockdown measures in seven townships from 6 PM on 18 April 2020 through Ministry of Health and Sport Order No. 38/2020 the Prevention and Control of Communicable Diseases Law [38]. To ease the impact of the pandemic the government announced an initial stimulus package including 100 billion kyats (nearly US $ 70 million worth of loan). The Covid-19 fund will be used to assist garment and manufacturing, hotel and tourism business as well as small and medium size enterprises owned by local people [39]. Myanmar has eased the restrictions in early of June with bars and restaurants have reopened. However, the cases are beginning to surge again in September with total 41,000 cases and 1000 deaths and now back to strict lockdown and ban of international commercial flight has been extended until the end of October [40].

3.7. The Philippines

The Philippines is the second-most populous country in ASEAN and home to more than 100 million people. The government reported the first imported Covid-19 case in January 2020 and confirmed the first case of local transmission by early March. By April, Luzon, the largest and most populous island in the country placed under enhanced community quarantine (ECQ), accounted for around 91% of the 6710 confirmed cases and 87% of reported deaths (WHO). As of 22 September, Luzon remains the most Covid-19 affected area, making up about 75% of the 291,789 confirmed cases and 62% of reported deaths (WHO). The Philippines' official Covid-19 response has three core elements: (i) granting “special temporary power” to the President by Congress, (ii) imposing a lockdown on the entire island of Luzon, (iii) employing the military and police to enforce the President's orders and lockdown measures [41].

Early gains in government response benefitted from previously established structures and mechanisms for responding to epidemics nationwide. The Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF-EID), already in place since 2014, worked alongside a National Task Force in charge of commanding operations. A National Action Plan and nationwide Covid-19 tracking process were the main tools used to support evidence-based decision-making processes and to decentralize the management of responses across the archipelago [42].

Signing into law Republic Act No.11469 or “Bayanihan to Heal as One Act” initiated an economic stimulus to provide relief to affected populations [42]. This included a $3.9 billion social protection program to aid poor families, earners in the informal sector, health workers who contracted Covid-19, and families of health workers who died from the disease [43]. A $610 million “Bayanihan Grant to Cities and Municipalities” to assist local government units in responding to the health crisis was approved [43]. Finally, a $1 billion wage subsidy package to support social security and workers of small businesses was allotted. The country was also placed under a “State of Calamity’ so the government can access disaster financing tools like Calamity and “Quick Response Funds”. And the Office of Civil Defense, the implementing arm of the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council, is supporting the National Task Force in coordinating operations in regions outside the capital through their field offices.

The government, however, faced several challenges early on that constrained its Covid-19 response. Due to the strong influence of the defense and security sector, initial efforts prioritized national security (eliminating the threat) approaches over public health (containing infectious disease) and disaster management (minimizing collateral damage). This led to negative perceptions that the government is “militarizing the pandemic response” causing unwanted fear and panic among the public during the lockdown. The national public health system also struggled to cope with the continuous increase in cases largely due to a shortage of medical professionals and underfinanced health infrastructure. This limited the government's capacity to conduct mass testing and systematic tracking, thereby preventing quick identification and neutralization of emerging disease hot spots. Covid-19 cases continue to increase in the Philippines to this date. This prompted the President to extend the declaration of a “State of Calamity” throughout the country for another year.

3.8. Singapore

Singapore, with a population 5.7 million people, confirmed its first imported case from Wuhan, China, on 23rd January 2020 [44]. In the early months of the pandemic, Singapore was hailed globally as a model of best practice in “flattening the curve” through its extensive testing, contact tracing and strict quarantining of infected cases. Even on 24th March 2020, when Singapore took the unprecedented step of closing its international borders to stem the spike in imported Covid-19 cases [45]- including from many ASEAN countries where limited testing masked the spread of infections across the region [46]- local transmissions remained relatively low and were linked mainly to known clusters identified through contact tracing.

This changed in early April 2020, however, when a major outbreak of infections occurred among Singapore's 43 migrant worker dormitories that house 200,000 South and Southeast Asian male migrant workers. Media coverage of the migrant dormitory outbreak focused on the socioeconomic vulnerability of these workers who faced strict restrictions of movement while residing in conditions of close proximity, impeding their capacity to practice safe social distancing [47]. Unlike migrant workers elsewhere in Southeast Asia, however, who lost their jobs and incomes through the pandemic, in Singapore the government continued to pay the basic salaries, housing and medical costs of all migrant workers in dormitories [48].

To contain the outbreak, Singapore's Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong announced nation-wide circuit breaker measures to enforce social distancing from 7th April until 4th May, which were subsequently extended until 1st June 2020 [49]. The relative success of these strict lockdown measures has been evidenced in Singapore's relative containment of Covid-19 as of August 2020 and its limited death toll of 27 fatalities, the lowest among all the ASEAN countries as reported by Worldometer in August 2020.

3.9. Thailand

Thailand with the population of almost 70 million is the first country in ASEAN and outside china infected by Covid-19 on 13 January 2020. Thai government has announced partial lock down to contain the spread of the virus. The situation in Thailand is improving as the number of new cases falls, with no new imported cases due a near total ban on incoming flights since early April. There is a criticism of lack of testing and suspicious low number cases reported. Thailand confirmed cases approximately 2000. The measures to contain the virus include: The country was placed under a state of emergency on 26 March until 30 April. The government has announced the cancellation of the Thai New Year celebrations called Songkran. The island of Phuket has been placed under lock-down from 30 March to contain the spread of coronavirus. Thailand's prime minister announced a nationwide 10 p.m. to 4 a.m. curfew starting April 22,020 to combat further spread. As for the economic stimulus, the first package valued at 100 billion baht (USD 3.2 billion) aimed supporting businesses in the form of low-interest loans, deductions in withholding tax, and VAT refunds (Asean briefing, 2020). On March 24, 2020, the Thai government issued its second stimulus worth 117 billion baht (US$3.56 billion). Thailand plan to new borrowing of 1 trillion baht (US $30,6 billion) for its latest stimulus package for economy impact of Covid-19. Thailand had eased restrictions to attract tourist in October 21. In October Thailand confirmed 3 new cases with total 3727 cases and 59 deaths.

3.10. Vietnam

Although Vietnam shares the long and bustling border with China, the pandemic is still under the government's control by applying various rapid responses. With the total population of 97,338,597 people, the first Covid-19 case was confirmed on January 23rd, 2020. As of September 27, the Vietnam government confirmed a total of 1069 cases [50]. Of which, 999 cases had recovered and 35 deaths from the pandemic [50]. The Vietnamese government demonstrated their prompt and aggressive response in the fight with such unprecedented diseases. In early February, Vietnam was the first nation after China to put a large residential area into the isolation zone to curb the negative impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. By isolating infected people and tracking down their contacts, the communities or villages, where were at risk of this pandemic since having close relation with the infected person, could be completely sealed off [51]. Together with stopping issuing visas for foreigners from infected nations, all international flights coming to or departing from the pandemic areas were suspended as soon as the first case was confirmed. Vietnam temporarily cleared from the pandemic at the end of April 2020. Vietnam required all Vietnamese and international visitors who returned from abroad to quarantine at centralized facilities for 14 days, followed by the implementation of nationwide quarantine on April 1st, 2020 [52]. To further prevent the spread of this pandemic, border crossings between Vietnam and Cambodia and Laos were temporarily closed.

After a 99-day streak without any community-transmitted cases and routine lives gradually backed to normal, on July 25, Vietnam suddenly faced with the second wave of Covid-19 pandemic by confirming the 417th case in Da Nang city, a tourism hotpot in the Middle of Vietnam, with an undetectable source of transmission. Even though a number of actions were quickly enacted focusing on this area to control the new wave including provincial quarantine, tracing suspected cases, or even lockdown some hospital had confirmed case, however, because of a quite high traveler visited this area during this time (more than 450,000 visitors in June) [53], the confirmed cases were double to 962 at the mid of August. Further, as of 31 July, Vietnam recorded the first death in Da Nang and this number sharply rose to 35 deaths till now. To deal with such situations, a temporary field hospital had been built within a week in this city, and hundreds of health care professionals voluntarily mobilized to fight with this unprecedented pandemic in this epicenter province. After that, the originate of this second wave could enter from outside of Vietnam - the unauthorized immigration, which strongly confirmed by hundreds of foreigners from China, Laos, and Cambodia illegally entered Da Nang, Ho Chi Minh, or other parts of Vietnam during this time. Immediately, numerous emergency restrictions were promulgated to prevent this unlawful activity like the Official dispatch No.3961/CV-BCĐ of imposing tighter border controls to crack down on illegal immigrants from neighboring countries on 25 July [54,55]. This policy came to reality by establishing more than 1600 border checkpoints throughout Vietnam which detected nearly 16,000 illegal immigrants within only six months [56]. Until now, this second wave has been well controlled with no more new detected case in the community during the last 26 days, however, this situation still need to firmly maintain as mentioned in the telegram of Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc (No. 1300 / CD-TTg) to remind and request all Ministry, Department and localities to continuously prevent and fight with the pandemic in order to promote normal activities for economic restoration and development, and protection of people's health [57].

All of the above discussion is summarized in Table 3, Table 4 below.

Table 3.

Summary of country responses to Covid-19 (Source: Authors, compiled from different sources).

| Country | Key regulations / New structure formed | Overall status (As of April 2020) | National responses to the Covid − 19 pandemic |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closing of border crossings | Travel restrictions or entry prohibitions | Closing of non-essential businesses, schools, and other public places | Quarantine or lockdown | Provision of Economic stimulus | |||

| 1. Brunei | Ministry of Health as the coordinating agency | Almost all of the confirmed cases were found to be linked with a wide-reach religious event in Malaysia at the end of February. | Closed by Malaysia. | All travels in and out of Brunei are banned from March 24 and March 16, respectively. | Prohibit mass gatherings from April 6. Online classes are still open until mid of May. Malls are recommended to limit their customer number per serve and provide takeout orders for restaurants. |

A two-week quarantine is applied for all citizens and visitors beginning of April 6. | Special aiding for healthcare workers and individuals affected by the pandemic. |

| 2.Cambodia | State of Emergency Law 10 April 2020 |

Underestimate the risk of COVID-19 and initially refused to apply strict action because of maintaining the close relationship with China | Closed by neighboring countries. | March 17, ban on travelers come from several high-risk nations March 30, temporarily suspending all visas types April 10, travel within the nation including district and provincial borders is prohibited |

April 1, closing casinos and schools. March 31, “sharing information” is prohibited |

On April 8, imposed a quarantine on all visitors entering Cambodia | Fiscal resources for the health sector and only “legally registered and formally verified” businesses, meaning that 95% will be excluded. |

| 3.Indonesia | Health Emergency Law 31 March 2020 Special Task Force on COVID-19 |

A rapid increase in cases are observed together with the highest mortality rate in ASEAN. | Land borders with Timor-Leste and in Papua province are closed. | All visitors are prohibited starting April 2 | Large Scale Social Restriction is implemented with domestic intercity air land and sea is suspended to prevent mass people movement as Ramadhan approaches | Not yet | Indonesia's third stimulus package was introduced on March 31 |

| 4.Laos | Prime Minister Order 29 March 2020 |

The last country in ASEAN to report infections together with the non-existent health care system and weak governance. | Closed the road border with Myanmar and China on March 30. Other parts are closed by the neighbor nations (Thailand and Vietnam) |

All traveling in and out of Laos event document holders are prohibited together with the suspending of all visa types | On March 19, schools, bars, entertainment venues, and major shopping centers were ordered to shut down. Prohibition for over 10 people gatherings Closed private hospitals and clinics nationwide. |

National stay-at-home order including closing provincial borders was issued on March 30. A 14-day self-quarantine is required for citizen returned back from the outside. |

On March 20, a preliminary 13-part stimulus package was approved during the cabinet's monthly meeting |

| 5.Malaysia | Movement Control Order 16 March 2020 |

The first country to report cases because of large religious gatherings. | Seal off borders on March 16 (the first country shut its borders in the region) | Ban all visitors and bar their citizen to travel overseas on March 16 | The restriction is set for the daily essentials list of fewer than 10 items and within 10 km from citizens' homes. | Placed under quarantine beginning on March 18. | Three economic stimulus packages have been revealed to aid society. |

| 6.Myanmar | COVID-19 Control and Emergency Responses Committee 31 March 2020 |

Lack of testing led to delay of reported cases (the first cases was detected on March 23) | Land borders with China are closed excluding goods and crew. India has closed its border with Myanmar. | All international flights and visas (except to diplomats) are suspended from March 30. | All economy sectors which did not directly serve for the fight of the pandemic have been closed from April 7. Bars are closed and malls are opened for limit periods. |

A lockdown was set up for Yangon only. 14-day quarantine is compulsory for workers returning from outside and those with “potentially infected” |

A financial aid was established for affected business and health sectors. |

| 7.Philippines | The Bayanihan to Heal as One Act 23 March 2020 |

Ranked the first in terms of the incidence cases daily. | No border sharing | All flights have been canceled until April 14. Foreigners are banned from entry, excluding Filipinos citizens and special officials. |

Worshipers have asked to stay at home and follow online celebrations during Holy Week | Close islands step-by-step starting from the main island of Luzon (including Manila) on March 16 | Financial supports were allocated for local authorities and social protection program |

| 8.Singapore | (Temporary Measures) COVID-19 Act 7 April 2020 |

A global leader in its early and aggressive response to COVID-19 but currently experiencing a second wave of cases from pockets of migrant workers | Closed by Malaysia. | On January 31, prohibited all China visitors and expanded to all short-term visitors on March 22. | April 3, schools and all non-essential businesses are closed. Banned all non- household members gatherings of any size. April 9, parks and sports stadiums will be closed if people continuously gather outdoors. |

All dormitories of more than 20,000 migrant workers were put into quarantine from April 5 | On April 6, the third round of support measures was announced |

| 9.Thailand | Emergency Decree 26 March 2020 |

Inconsistent policies over travel and quarantine, poor communication, and supply shortages | All borders were closed on March 22. | Foreign visitors are banned starting on March 22. | Alcohol sale points were prohibited from April 10. Schools remain closed till July 1. |

A national curfew was set from 10 p.m. to 4 a.m. starting April 3 | On April 7, the third stimulus measure was issued by the cabinet. Lending rates will cut as a statement of the six largest banks. |

| 10.Vietnam | National Steering Committee for for COVID-19 Prevention and Control 31 January 2020 |

The pandemic management is relatively well even with limited resources and sharing bustling borders with China. | Border sharing with Cambodia and Laos was closed from March 31. | Banned all flights to and from China from February 1. | Banning on public gatherings of over 20 people and suspending non-essential public services from April 1. | The quarantine was completely placed in several high-risk areas from mid- February. A 15-day national lockdown began April 1. |

The fiscal package was focused on the most affected by the pandemic in early April |

Table 4.

Nine of the indicators of government policies recorded on ordinal scale (Source: Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, www.covidtracker.bsg.ox.ac.uk).

| Countries | Responses⁎ |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closure of School closinga | Closure of Workplace closinga | Cancellation of public eventsb | Closure of Public transport closinga | Public info campaignc | Restrictions on internal movementd | International travel controle | Testing frameworkf | Contact tracingg | |

| Brunei Darussalam | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Cambodia | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Indonesia | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Lao PDR | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | NA |

| Malaysia | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Myanmar | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Philippines | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Singapore | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Thailand | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Vietnam | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

Updated to 13/04/2020.

0 - No measures; 1 - Recommend closing; 2 - Require closing.

0- No measures; 1 - Recommend cancelling; 2 - Require cancelling.

0 —No COVID-19 public information campaign; 1 - COVID-19 public information campaign.

0 - No measures; 1 - recommend movement restriction; 2 - restrict movement.

0 - No measures; 1 - Screening; 2 - Quarantine on high-risk regions; 3 - Ban on high-risk regions.

0 - No testing policy; 1 - only testing those who both (a) have symptoms, and (b) meet specific criteria (eg key workers, admitted to hospital, came into contact with a known case, returned from overseas); 2 - testing of anyone showing COVID19 symptoms; 3 - open public testing (eg “drive through” testing available to asymptomatic people).

0 - no contact tracing; 1 - limited contact tracing – not done for all cases; 2 - comprehensive contact tracing – done for all cases.

NA: Not available.

4. Comparative analysis of ASEAN country responses

The policy sciences framework first proposed by Lasswell (1956) is useful to understanding government responses to Covid-19 as it prompts critical examination of different contextual conditions and changing policy environments that shape decision-making processes and policy outcomes. Building on this foundational framework, Weible et al. (2020) propose ten categories for examining the efficacy of governance strategies related to: (1) national policy-making; (2) crisis response and management; (3) global policy-making; (4) transnational administration; (5) policy networks; (6) implementation and administration; (7) scientific and technical expertise; (8) emotions, narratives and messaging; (9) learning; and (10) policy success and failures (Table 5 ). To assess the efficacy of governance responses to Covid-19, we further disaggregate these groupings into: a) policy and decision making; b) communication and perceptions; and c) science and learning. Taken together, we utilize these as components of a framework for analysis to compare ASEAN and member country pandemic responses.

Table 5.

Policy sciences (Sources: Modified from Weible et al. (2020) based on Lasswell (1956).

| Policy Sciences perspectives | Issues to consider |

|---|---|

| Policy and decision making | |

| 1. Policy making (within country) | Policy making (within the country) Uncertainties exist regarding the duration and termination of policy decisions Government non-decisions become just as important as decisions |

| 2. Crisis response and management | Responses occur at strategic and operational levels Mitigating value conflicts spark public controversies and blame-games Transboundary crises can both spur and challenge collaboration |

| 3. Global policymaking and transnational administration | Inequalities drive differential impacts of policy responses, which, in turn, exacerbate inequalities Destabilization and reinforcement of global policy processes Uncertainty about the locus of authority and influence of global professionals |

| 4. Policy networks | Policy networks react and contribute to the shifting of attention to policy issues and changing of government agendas Prior policy networks condition policy and societal responses Changes in importance of policy networks' people and organizations, relations, and resources |

| 5. Implementation and administration | Administrative fragmentation and decentralization complicate implementation Front-line workers exercise discretion and self-regulation Co-production requires overcoming collective action challenges |

| Communication and perception | |

| 6.Emotions and public policy | Governments appeal to emotions to help legitimize policy responses and steer public reactions Emotionally charged language can recall cultural and historical contexts Policy responses force a reevaluation of the emotional spheres in societies |

| 7. Narratives and messaging | Governments attempt to provide sufficient information in a timely manner to the public Governments attempt to provide information that is accurate and non-contradictory to the public Governments can spawn controversies by engaging in speculations |

| Science and learning | |

| 8. Scientific and technical expertise | Scientific and technical experts become more central in policy responses to uncertain problems Governments invoke scientific and technical expertise to inform and legitimize problems, responses, and evaluations Scientific and technical expertise can obscure accountability of decisions |

| 9. Learning | Urgency triggers learning from others' experiences Learning manifests in different ways Different barriers inhibit learning |

| 10. Policy success and failure | Who is affected and to what extent influence frames of success or failure Success or failure judged as part of decisions, processes, and politics It is possible to conceive of a spectrum from success to failure Lenses and narratives shape perceptions of success and failure |

4.1. Policy and decision making

4.1.1. Policy perspectives

Governments adopt public policies through different pathways. Because COVID-19 is a novel coronavirus, there is a high degree of knowledge uncertainty and misinformation around it. One reference point that is taken as reliable among ASEAN countries is the World Health Organizations' (WHO) information on COVID-19, which is benchmarked around what other countries have been doing to contain and treat it. For example, WHO's advice on tracking and tracing cases has been actively and consistently implemented by ASEAN member states such as Singapore and Malaysia. In developing countries with weak healthcare systems, however, testing and contact tracing has been restricted to small pockets of urban centers as national governments have prioritized economic recovery from the pandemic recession over public health expenditure.

At the ASEAN level, efforts to negotiate coordinated actions between countries have been organized around the concept of “inclusive regionalism” to combine resources and energies into the resolution of collective challenges (Ho, 2020b). One manifestation of this inclusive regionalism has taken the form of stimulus packages in every ASEAN country. Agreement was also reached in April 2020 to establish an ASEAN COVID-19 Response fund, which has included efforts to diffuse and transfer ideas between national governments within the limits of ASEAN's mandate of non-interference with respect to national values and cultures. As a key node in global supply chains, ASEAN countries have also begun to explore opportunities to recover from the pandemic recession by relocating production centers away from China and back to countries in Southeast Asia.

4.1.2. Crisis response and management

ASEAN member country responses to the pandemic have covered the entire policy spectrum, ranging from aggressive contact tracing, lockdowns and social distancing measures through to business as usual. These responses have varied over time and continue to change as different countries in the region experience second waves of viral outbreaks or recover from major bouts of infection. Even within the same country, responses to the pandemic diverge between jurisdictions and along rural-urban and socioeconomic lines (for instance, densely populated slums and informal urban settlements are more vulnerable to the spread of infection but are less likely to receive adequate healthcare).

The organization of Covid-19 responses also differs markedly between countries, ranging from ministerial level centralized responses (for example, Brunei, Vietnam, Singapore and Malaysia) through to decentralized task forces (such as Indonesia and Lao DPR) that comprise public-private, private-societal and co-governance partnerships between medical service providers, government agencies, private and corporate financiers and civil society organizations. Many response efforts have been mired in public controversies, power asymmetries and blame games. Mirroring the global dilemma, ASEAN countries with mounting national debts and unprecedented economic contractions continue to struggle internally with questions of whether public health or economic recovery should take precedence. This dilemma becomes more pronounced the longer national borders remain closed and supply chains remain disrupted. Political instability is also a growing risk across the region due to protracted levels of high unemployment, restrictions on movement and food insecurity, especially in Southeast Asia's large informal sector. In this context of accumulating political and economic pressure, communication failures, political values and identities, and weak mandates can further undermine efforts to achieve a collective crisis response (Bond and Hart, 2010).

4.1.3. Global policymaking and transnational administration

Growing socioeconomic inequality across the ASEAN region has affected the spread of COVID-19 and divergent responses to its containment. Poverty is one reason some ASEAN countries could not implement strict lockdown such as in Indonesia and Philippines. In addition, vulnerable groups such as migrant workers continue to benefit less from development in ASEAN. It showed that they are proven vulnerable to get more infections of COVID-19 than any other groups or society for example the cases of infection in Singapore surged in migrant workers clusters. While in ASEAN the response of COVID-19 is more emphasis on extensive measures of member states in the first place. Regional cooperation is emerging in later stages with exchange information and information sharing among member states and ASEAN Respond Fund COVID-19 to assist member states that need funding. COVID-19 is disrupting tourism and travel, supply chains and labor supply. Among ASEAN countries, Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand are heavily integrated in regional supply chains and will be the most affected by a reduction in demand for the goods produced within them. Indonesia and the Philippines have been increasing supply chain engagement and will also not be immune. Vietnam is the only new ASEAN member integrated into supply chains with China and is already suffering severe supply disruptions.

4.1.4. Policy networks

ASEAN policy approach to past epidemics has been grounded on its unique and pragmatic networks in what is so-called as the ASEAN Plus Three (APT) (including China, Japan and South Korea) for regional disease surveillance mechanisms has developed a Protocol for Communication and Information Sharing on Emerging Infectious Diseases, with a standardized Protocol for Communication and Information Sharing on Emerging Infectious Diseases that encourages member states to report all cases of diseases that are categorized as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). For example, Past programmes include the cooperation of Disaster Safety of Health Facilities and the ASEAN +3 Field Epidemiology Training Network as well as the ASEAN Regional Public Health Laboratories Network (RPHL) through the Global Health Security Agenda platform. However, it is not clear how such networks contribute to effective policy making during the storm of COVID-19.

4.1.5. Implementation and administration

Response of COVID-19 needs inter-agency collaboration across fragmented and sectoral bureaucracy. Some of ASEAN countries had difficulties to have interagency collaboration due to sectoral ego. Hierarchical coordination, power struggle between levels of government such as in Indonesia decentralization complicate the effective response of COVID-19. The pandemic has disrupted the daily lives routine in all ten ASEAN countries. In slowing down the spread of COVID-19 behavior changes are needed. People were forced to stay at home for months or more to prevent the further spread of the virus. Work, study and even prayer activities have been affected and should do these activities at home instead and conducted online. The effort of social distancing has been applied to all ten Member countries. Malaysia for example has implemented a Movement Control Order (MCO) since 18 March 2020. This MCO has extended to April 28, 2020. Similarly, in Indonesia Indonesian President Jokowi appeals to citizens to work, study and pray at home on 15 of March 2020. This social distancing has been continued with the order of large-scale social restriction in major cities in Indonesia in Jakarta for example adopted until 23 April 2020 and this has been extended. In Singapore, closure of the workplace has to be implemented for 28 days “circuit breakers” from April 3, 2020. The Philippines also implemented community quarantine in metro Manila on 13 of March 2020 and in other parts of its region. The community needs to comply with strict measures. Social distancing was also adopted in 12 cities in Vietnam.

4.2. Communication and perception

4.2.1. Emotions and public policy

Succeed in changing behavior during COVID-19 include establishing trust in health authorities, recommendation and information. Citizen willingness to cooperate to social distancing and understanding the threat with maintaining good hygiene and immune systems have been the key to cope with pandemic. However, for many social distancing is not an option. For example, in Philippine as they struggle to meet daily needs, they fear death from hunger and anxiety rather than from infection. Similarly with Indonesia when fulfilling the daily needs are more important than staying at home. In addition, wearing a mask in some countries has become mandatory as recently in Indonesia Jokowi appealed to citizens to wear masks in the public. Fear of the virus spread also created some unacceptable discriminatory behaviors such as in Cambodia where member of the public posted hateful Facebook comments in reaction to the Health Ministry's original statement, blaming Cambodia's Muslim communities of or the spread of the virus in the country. Similarly in Indonesia, people in some local region has rejected the death because of victims were going to be buried in their areas because of infection fear. They need more education and awareness of the community on the threat, to massively campaign particularly what should do and not do at local community level.

4.2.2. Narratives and messaging

Governments that communicate sufficient and accurate information in a timely and transparent manner can gain public trust during the pandemic. Governments that provide unclear rules end up creating opportunities for abuse and cause unwanted public fear and panic. In general, governments want to project force and model good governance to their constituents by showing them that ‘the government is taking action’. However, when poorly communicated it can threaten that public and drive them to unwanted behaviors. For instance, when the confirmed cases of COVID-19 were first announced in ASEAN, many reacted by engaging in mass panic buying. This occurred in several countries including Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia. The first time the Philippine President addressed the public, he was flanked by top-ranking military and police officials, which gave the impression that the government is ‘militarizing’ the government's response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Public perceptions and sentiments need to be managed carefully. Greater compliance to government directives such as wearing masks in public requires building and maintaining public trust. Narratives and messaging play a key role in shaping and influencing public trust. Singapore's Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and Vietnam's Deputy Prime Minister Vu Duc Dam have been models of effective communication and transparency. While Indonesia has been accused of providing too little information and lack of transparency in handling the pandemic.

4.3. Science and learning

4.3.1. Scientific and technical experts and information

Scientific, medical and public health experts are evidently central in policy responses to COVID 19. Indonesia proposed the establishment of ASEAN-China Ad-Hoc Health Ministers Joint Task Force during the Special Meeting of the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of ASEAN and People's Republic of China (PRC) on February 20, 2020. The Task Force is expected to focus on the exchange of information and data, especially in handling the COVID-19 outbreak, organizing expert team meetings, and encouraging joint research and production for virus detection and vaccine. More recently, during the ASEAN Plus Three (APT) Summit, April 14, 2020, the Indonesian President called for leaders to provide guidance to the Health Ministers to strengthen research collaboration to create anti viruses and vaccines. In anticipation of a pandemic going forward, Indonesia also proposed the establishment of an APT country special task force for a pandemic whose task would be to provide comprehensive steps to strengthen the resilience of the APT Region in the face of a future pandemic. The pandemic however actually has exposed disparity in terms of capacity, role and influence of communities of scientific and technical experts across ASEAN countries. Across the region, governments who made decisions based on medical and scientific evidence — relying on public health and medical officials — have come out on top. Governments who have made their decisions based on short-term economic and political calculations have not been able to get ahead of the situation. In ASEAN countries where the pandemic responses have been more effective, scientific, medical and public health experts have played important roles in decision-making processes.

4.3.2. Learning

Lessons learned from their own nations and other neighbors when dealing with the previous epidemic could provide valuable insight into the combat with this current pandemic. In parallel with SARS and MERS, COVID-19 was found to share a similar characteristic of origin, symptoms and host immune response (5). Thus, it creates a change to boost the national responses to combat the infection and prepares for an outbreak of similar coronavirus in the future. Several triggers need to be urgently improved including surge healthcare capacity, infection prevention and control and update information for the whole public. To improve healthcare capacities, various supports were allocated from their own national budget or even sent from international organizations and nearby nations. Singapore, Indonesia, Myanmar, and Philippines activated their economic stimulus package for healthcare spending. Besides, the World Bank, Asian Development Bank also supported Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos to the purchase of medical supplies. Whereas, Singapore, Vietnam and other nations (China, South Korea, Japan, USA) also aid their neighboring ASEAN countries by training medical workers, medical supplies or even sending medical experts. Further, the COVID-19 public information campaign existed in all nations as assessed from the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker. This brings the benefits of the digital evolution to broaden and daily update information for the whole population.

4.3.3. Policy success and failure

During COVID-19 onset during January–February 2020, ASEAN's “One ASEAN - One Response” (OAOR) framework was put to the test. Despite OAOR's main focus on natural hazards, however, some of the ASEAN Committee on Disaster Management (ACDM) members have been the leading agencies responding to COVID-19 such as BNPB in Indonesia. In addition, despite being proven relatively successful in the past, the ASEAN coordinated response to COVID-19 seems less visible in the first quarter of 2020. COVID-19 impact on ASEAN economy will be tremendous. Unfortunately, ASEAN did not discuss quite meaningfully to protect its interest in the integrity of ASEAN Economic Communities including its Blueprint 2025 that would offer US$2.6 trillion for over 622 million people (https://asean.org/asean-economic-community/) that have been implemented since 2016.

The “One Vision, One Identity, One Community” seems to be a utopia as each ASEAN member state treats their borders as their absolute sovereignty while lacks the collective vision of “greater good” for all. Therefore, fuller understanding ASEAN's response to COVID-19 should be based on individual analysis of each member. Most ASEAN countries have implemented measures to contain the virus by closing borders, travel restrictions, closure of schools, working place, lockdown or quarantine. The existing principle of non-interference and the reliance on action of individual member states in the first place contained the virus could be blamed as the slow join and collective action from regional ASEAN to address the pandemic. The meeting on 20 February of ASEAN-China foreign ministers meeting in Vientiane, Laos was a watershed in bringing together China and ASEAN member states to combat the COVID-19 epidemic. Driven by security and economic interests, ASEAN and China decided to expand.

5. Conclusion: Toward broader ASEAN health system resilience?

This paper has argued that ASEAN potentially has a constructive role to play in formulating a coordinated pandemic response, but this has not been fully realized in the unfolding context of Covid-19. The unprecedented pace and scale of the viral disaster has unraveled many socio-economic connections forged through decades of trade regionalization and economic integration. National border closures have revealed the internal weaknesses of (often underfunded) national health systems and the varying capacities of governments to cope with extreme conditions of economic and social precarity. These diverging capacities are reflected in the variegated responses of ASEAN member countries to the pandemic during different phases of its circulation that have ranged from aggressive contact tracing, testing and quarantine measures through to denial of the severity and spread of the virus in efforts to re-open economies. The pandemic has also exposed deep socioeconomic inequalities within countries through the outbreak of infections in migrant worker dormitories, slums, informal settlements and low-income housing areas.

In this regional context of the hardening of nation-state boundaries, ASEAN has endeavored to use its existing cooperative frameworks as a basis for coordinating a pandemic response among national governments. At the time of writing, as the virus and pandemic-induced recession continue to generate cascading health and socioeconomic impacts across the region, ASEAN's response has been largely confined to sharing and disseminating information via online platforms. To reconnect and rebuild this fragmented region, multi-sector and multi-stakeholder partnerships are needed to work across borders in strategic ways. With border closures preventing freedom of movement and face-to-face collaborations, online meetings are now the primary means by which recovery assistance and capacity-building must be negotiated for the short to medium term.

This paper has documented and analyzed ASEAN both as a regional organization and as the sum of its member state responses to COVID-19. Our main finding has been that at the regional level, there has been a lack of cohesiveness in utilizing existing regional health frameworks to develop a coherent response to the pandemic. Within member countries, new outbreaks of second waves of the virus show that temporary success in containing the virus cannot be taken for granted as complacency can result in fresh outbreaks that can quickly jump organizational scales of governance to overwhelm national health systems. Coordination at national level has worked really well and regional coordination, amid slightly late, allows for refocusing of efforts. Communication has worked particularly well, especially in terms of provision of regularly updated data on impacts of Covid-29 at the regional level, which enable comparison between countries and input to the global database. Resource and funding, particularly through existing mechanisms and collaboration with other countries.

Finally, we are entering the super year of sustainability through accelerated implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), along with other global frameworks such as the Paris Agreement on Climate change, the Sendai Framework for Disaster risk Reduction and the New Urban Agenda. Health is the cross-cutting issue within these global frameworks. To meet these commitments, ASEAN and its whole communities will need to set clear policy goals for implementation that are supported by fiscal commitments to build health system resilience that is specific and sustainable in each country.

Credit author statement

All authors contributed equalliy to the conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis and writing of the paper.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

Riyanti Djalante joins the Asean Secretariat since 1 October 2020. The original and final version of the paper was submitted prior to the date. The opinion expressed is of her own and does not reflect nor represent the Asean Secretariat.

References

- 1.ASEAN Secretariat . 2017. Celebrating ASEAN: 50 years of evolution and progress. Association of Southeast Asian nations. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Association of Southeast Asean Nations (ASEAN) 2018. ASEAN Post-2015 Health Development Agenda 2016-2020. Jakarta. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Association of Southeast Asian nations ASEAN Health Sector responds to 2019 Novel Coronavirus threat. https://asean.org/asean-health-sector-responds-2019-novel-coronavirus-threat/ Published 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

- 4.Association of Southeast Asean Nations (ASEAN) ASEAN Health Sector Efforts in the Prevention, Detection and Response to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) https://asean.org/?static_post=updates-asean-health-sector-efforts-combat-novel-coronavirus-covid-19 Published 2020. Accessed April 29, 2020.

- 5.Douglass, Mike, Michelle Ann Miller. Disaster justice in Asia’s urbanising Anthropocene. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space. 2018;1(3):271–287. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Association of Southeast Asean Nations (ASEAN) ASEAN Economic Community. https://asean.org/asean-economic-community/ Published 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020.

- 7.VASHAKMADZE E.T. The outlook for East Asia and Pacific in eight charts. https://blogs.worldbank.org/eastasiapacific/outlook-east-asia-and-pacific-eight-charts-coronavirus-covid19 Published 2020. Accessed.

- 8.World Health Organization TWB . 2015. Tracking universal health coverage: First global monitoring report. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowie Nile. Devout at a distance in contagion-hit Brunei. Asia Time April. 2020;2 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan Asif Ullah. Brunei's Response To COVID-19. The Asian Post. 2020;(18 April) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Worldometers Cambodia. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/cambodia/ Published 2020. Accessed April 28, 2020.

- 12.New Straits Times Eight days, and no new Covid-19 cases for Cambodia. New Straits Times. 2020;(April 21) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Star M.Y. Cambodian PM urges people to remain vigilant despite no new Covid-19 cases for 12 straight days. The Star. 2020;(25 Apr) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ratcliffe Rebecca. Fears as Cambodia grants PM vast powers under Covid-19 pretext. The guardian. 2020;(10 Apr) [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Guardian . 2020. Fears as Cambodia grants PM vast powers under Covid-19 pretext. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xinhua . 2020. Laos to continue suspension of tourist visas for people from COVID-19-hit countries. [Google Scholar]

- 17.KPMG Economic stimulus measures. https://home.kpmg/xx/en/home/insights/2020/04/cambodia-government-and-institution-measures-in-response-to-covid.html Published 15 April, 2020. Accessed.

- 18.Djalante, Riyanti, Jonatan Lassa, Davin Setiamarga, Choirul Mahfud, Aruminingsih Sudjatma, Mochamad Indrawan, Budi Haryanto, et al. Review and analysis of current responses to COVID-19 in Indonesia: Period of January to March 2020. Progress in Disaster Science. 2020:100091. doi: 10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barker Anne, Souisa Hellena. 2020. Coronavirus COVID-19 death rate in Indonesia is the highest in the world. Experts say it's because reported case numbers are too low. 23 MarMarch. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Assian Development Bank . 2020. The Economic Impact of the COVID-19 Outbreak on Developing Asia. [Google Scholar]

- 21.International Science Council Indonesia COVID-19 Policy-Making Tracker. https://www.ingsa.org/covid/policymaking-tracker/asia/indonesia/ Published 2020. Accessed April 29, 2020.

- 22.Humas . 2020. Presiden: Pemerintah Sedang Persiapkan Regulasi Sanksi Pelanggaran Protokol Kesehatan. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kompas . 2020. Minister of Education and Culture: Face-to-Face Learning Allowed in the Yellow Zone, PJJ Use Emergency Curriculum. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santoso Y.I. 2020. There are four new programs to restore the economy, suction budget of Rp. 126.2 trillion. [Google Scholar]