Abstract

Purpose

Several high-profile organizations have mandated the delivery of survivorship care plans (SCPs) despite mixed evidence regarding the effectiveness of SCPs on key survivor-level outcomes. There is a need to understand the types of survivor-level outcomes the SCPs are likely to change. Informed by existing frameworks and the literature, the objective of this study was to understand the pathways linking the receipt of a SCP to key survivor-level outcomes including patient-centered communication (PCC), health self-efficacy, changes in health behaviors, and improvements in overall health.

Methods

We used structural equation modeling to test the direct and indirect pathways linking the receipt of an SCP to patient-centered communication (PCC), health self-efficacy, and latent measures of health behaviors and physical health in a nationally representative sample of breast and colorectal cancer survivors from the Health Information National Trends Survey.

Results

The receipt of an SCP did not have a significant effect on key survivor-level outcomes and was removed from the final structural model. The final structural model fit the data adequately well (Chi-square p value = 0.03, RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = .88, and WRMR = 0.73). PCC had a significant direct effect on physical health but not on health behaviors. Health self-efficacy had a significant direct effect on physical health and health behaviors.

Conclusion

The receipt of an SCP alone is unlikely to facilitate changes in PCC, health self-efficacy, health behaviors, or physical health.

Implication for Cancer Survivors

A SCP is a single component of a larger model of survivorship care and should be accompanied by ongoing efforts that promote PCC, health self-efficacy, and changes in health behaviors resulting in improvements to physical health.

Keywords: Cancer survivors, Patient care planning, Patient-provider communication, Patient relevant outcome, Structural equation modeling

Introduction

In the years following the release of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) landmark report From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition, several high-profile organizations, including the American College of Surgeons [1], the American Cancer Society [2], and others [3–5] have endorsed the routine delivery of survivorship care plans (SCPs) as a tool to support survivors transitioning from active treatment to survivorship [6]. SCPs are individually tailored documents that combine personalized treatment summaries with plans for follow-up care, surveillance, prevention, and supporting information around health-promoting behaviors and are intended to facilitate communication among survivors and clinical care teams [6, 7].

Despite widespread endorsement and growing adoption, evidence regarding the effectiveness of SCPs remains mixed with most of the evidence supporting the benefits of SCPs coming from observational studies [8]. Inconsistencies for the effectiveness of SCPs may be, in part, due to variation in outcomes measured resulting from limited knowledge around the types of outcomes that SCPs are likely to impact [8–10]. Research in this area has mainly focused on more distal outcomes such as survivors’ overall health status when it may be more appropriate to focus on proximal outcomes including patient-provider communication [11, 12].

Patient-provider communication is central to high quality cancer care [13]. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) monograph patient-centered communication (PCC) in cancer care recognized the importance of communication in cancer care and outlines six core functions essential for meeting the complex needs of cancer survivors: (1) fostering healing relationships, (2) exchanging information, (3) responding to emotions, (4) managing uncertainty, (5) making decisions, and (6) enabling patient self-management [14]. Studies have also established a direct and indirect pathways between PCC and patient health outcomes [14–17]. Thus, the receipt of an SCP may positively affect PCC, resulting in changes to subsequent outcomes and behaviors including increased confidence in one’s ability to manage care [18], changes in health behaviors, and improvements in overall health [19]. There is a need for more research to explore the pathways linking SCPs to outcomes at a survivor level; otherwise, inconsistencies in measured outcomes are likely to persist, limiting the extent to which definitive conclusions can be drawn around SCP effectiveness.

Few frameworks exist depicting the proposed pathways linking SCPs to outcomes at the survivor level. Parry et al. proposed a clinical framework for evaluating SCPs that include proximal and distal outcomes suggesting that SCPs facilitate communication that, in turn, influence distal outcomes, such as management of late effects, and long-term physiological and psychosocial outcomes [20]. However, the framework does not depict indirect pathways linking SCPs to proximal and distal outcomes. Models and frameworks depicting the direct and indirect pathways linking PCC to outcomes may enhance our understanding of the pathways linking SCPs to proximal and distal outcomes. Lafata et al. proposed a conceptual framework suggesting that PCC directly and, in most cases, indirectly affects overall health via affective-cognitive outcomes, such as health self-efficacy, and behavioral outcomes, such as exercise and nutrition [17, 21]. Although these frameworks may aid in the selection of outcomes at the survivor level, neither have been tested empirically in a sample of cancer survivors.

Frameworks in survivorship care planning and communication have been largely informed by observational studies testing direct pathways linking SCPs or PCC to various outcomes in a single cancer site controlling for sociodemographic, clinical, and cancer-related characteristics. As a result, no study has simultaneously tested the direct and indirect pathways linking SCPs to survivor-level outcomes [20, 22]. Therefore, the objective of this study was to test the direct and indirect pathways linking SCPs to proximal and distal outcomes among a nationally representative sample of breast and colorectal cancer survivors. Examining these proposed pathways simultaneously in a representative sample of cancer survivors addresses an important gap in the literature and offers a more comprehensive approach to understanding the impact of SCP receipt on appropriate survivor-level outcomes, in turn, helping to inform future models of survivorship care planning.

Methods

Survey design and sample

The Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) is a nationally representative cross-sectional probability survey administered in English and Spanish by the NCI to assess current access to and use of information about cancer across the cancer care continuum from cancer prevention through survivorship. We combined data from two iterations of HINTS: HINTS 4, cycle 4 (fielded August-November, 2014, response rate 34.4%), and HINTS 5, cycle 1 (fielded January–May, 2017, response rate 32.4%). These iterations were selected due to their proximity to the Commission on Cancer 2015 mandate for SCP delivery and are the only two surveys that include all outcomes of interest following the release of the IOM report. For this analysis, we restricted the sample to those who reported a personal history of breast or colorectal cancer and excluded those who indicated that they were still in active treatment—defined as still receiving chemotherapy, radiation, and/or surgery for their cancer—to align with the post-treatment phase of cancer survivorship [6]. We chose breast and colorectal cancer survivors because they comprise approximately 30% of the total cancer survivor population and represent two of the most prevalent cancers in males and females [23]. The final sample size for the analysis was 212 cancer survivors.

Survey items

Respondents reported sociodemographic, clinical, and cancer-related information, including gender, age, education, race, income, health insurance status, and cancer site. Appendix 1 provides a list of relevant HINTS survey items, responses for each item of interest, and analytic categories used in this analysis.

Receipt of SCP.

The primary predictor variable in the model was receipt of an SCP. Respondents answered the following questions: “Did you ever receive a summary document from your doctor or other health care professional that listed all of the treatment you received for your cancer?” Response options were yes or no. This item has previously been used as a proxy for SCPs [24].

Patient-centered communication.

Survivors were asked about their communication experiences during the prior 12 months with doctors, nurses, or other health professionals. These items were grounded in the PCC framework originally proposed by Epstein and Street, corresponding to the six core functions of PCC and overlapping concepts that impact the communication exchange [14]. Response options were always, usually, sometimes, or never. Items were reverse scored prior to analysis and summed to create a continuous overall score for PCC, where higher scores indicate higher levels of PCC [25, 26].

Health self-efficacy

Respondents rated their confidence in their ability to take care of their health. Response options were completely confident, very confident, some-what confident, a little confident, and not confident at all. Items were reverse scored and treated as a continuous variable with higher scores indicating higher levels of self-efficacy to manage health [27].

Health behaviors

Respondents provided information on healthy lifestyle behaviors, including aerobic physical activity, fruit and vegetable intake, and tobacco use. Responses were categorized to align with the National Comprehensive Care Networks (NCCN) recommended guidelines and loaded onto a single latent variable [28]. Evidence supports combining health behaviors into a latent variable since there is a tendency for these behaviors to co-occur [29, 30].

Physical health

Respondents provided information about their physical health, including their perceived health status, body mass index (BMI), and number of chronic conditions in addition to cancer. The HINTS survey includes a variable calculating BMI for all respondents who self-reported height and weight. To calculate the number of chronic conditions, respondents indicated yes/no to ever being told if they had each of the following conditions: diabetes or high blood sugar, hypertension or high blood pressure, a heart condition, chronic lung disease, or arthritis or rheumatism. Responses were summed with higher scores indicating a higher number of chronic conditions. Finally, respondents were also asked to rate their perceived overall health with response options being excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor. Evidence supports the creation of a latent measure for physical health by combining BMI, number of comorbidities, and subjective self-ratings of health [31].

Data analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics on sociodemographic, clinical, and cancer-related information. We also reported the prevalence of receiving an SCP and calculated descriptive statistics for survey items corresponding to outcomes identified in previous frameworks and observational studies—PCC, health-self efficacy, minutes of physical activity, fruit/vegetable intake, smoking status, BMI, number of chronic conditions, and perceived health status.

We used structural equation modeling (SEM) to test direct and indirect pathways linking SCPs to proximal and distal outcomes and assess if the proposed model was supported by the HINTS data. SEM is a multivariate statistical analysis technique that combines factor analysis and multiple regression analysis to analyze the structural relationships between measured variables and latent constructs. First, we developed and tested a measurement model for two latent variables corresponding to health behaviors and physical health using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) as described by Brown [32]. To accommodate the use of categorical indicators and account for missing data, we estimated parameters using weighted least squares with robust standard errors (WLSMV). Parameters were therefore estimated in terms of linear regression coefficients for continuous indicators and by probit regression coefficients for categorical indicators [33]. After evaluating the fit and factor loadings of the measurement model, we specified an a priori structural model, as proposed in Fig. 1.

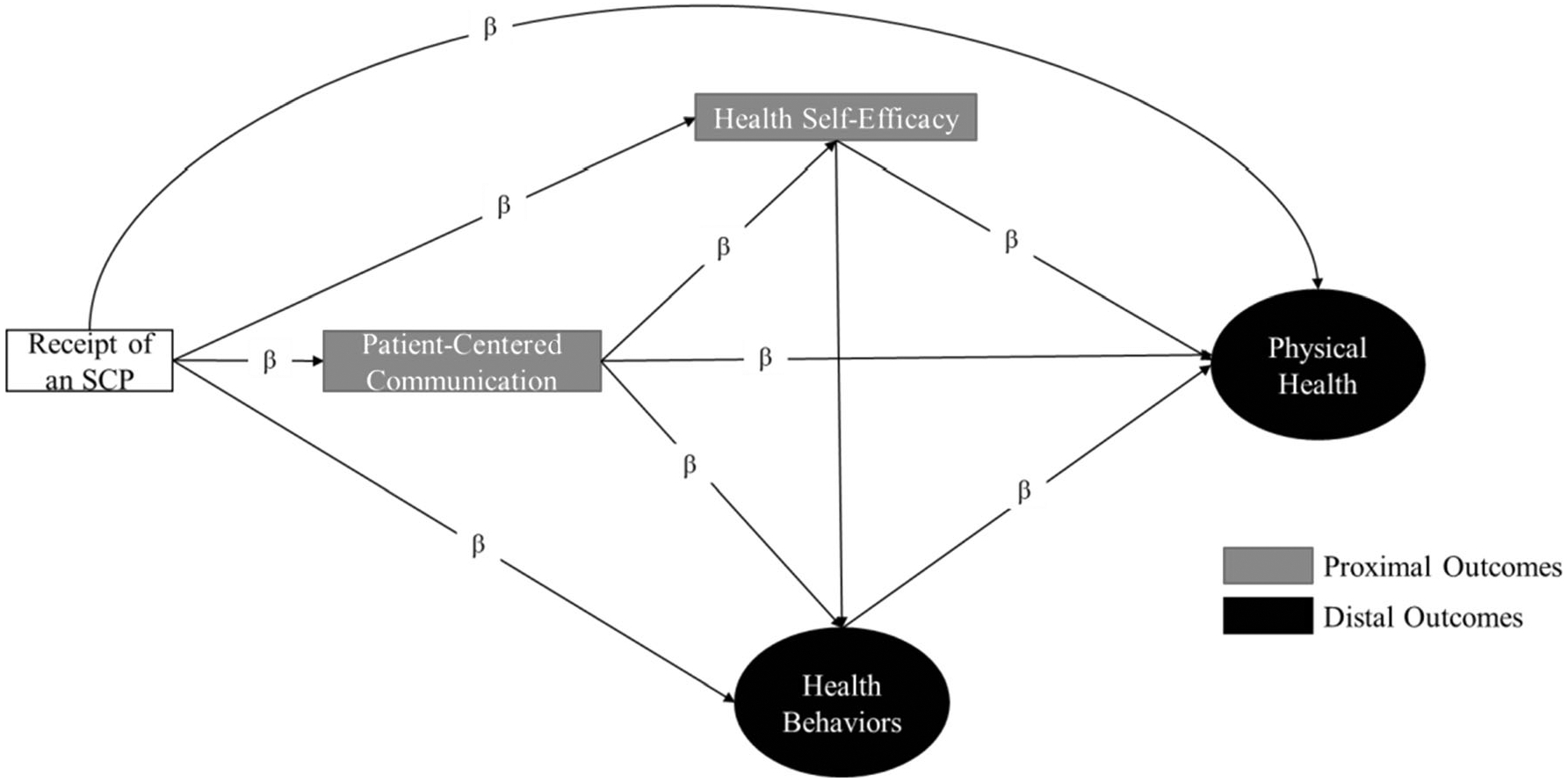

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized pathways linking SCPs to proximal and distal outcomes

The hypothesized structural model is based on Parry et al. clinical framework of survivorship care planning in which SCPs facilitate communication, in turn, resulting in improved health outcomes [20]. We adapted the Parry et al. framework to emphasize PCC by incorporating Lafata et al. conceptual framework in which the communication exchange between the patient and the provider itself can directly lead to improved health outcomes during and after cancer and, in most cases, affects health indirectly through health self-efficacy and health behaviors [17, 21]. We obtained standardized parameter estimates representing direct and indirect effects with the significance level set to 0.05 using the WLSMV estimator.

Overall model fit was assessed using chi-square, comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and weighted root mean square residual (WRMR) [34–36]. Examination of RMSEA values below 0.10, CFI values above 0.95, and WRMR values below 1.0 suggest approximate model fit. Modification indices, standardized factor loadings, and residuals were used to assess localized areas of ill fit. Missing data were handled by pairwise deletion, which treats missingness as a function of the observed covariates but not of the observed outcomes [33, 37]. We used MPlus Editor 7 [38] for all modeling and SAS 9.4 [39] for all data cleaning, recodes, and descriptive analysis. To reduce the risk of a type 1 error, HINTS-supplied survey weights using jackknife variance estimation techniques were incorporated into analyses to account for the complex HINTS sampling design and to calculate nationally representative estimates [40]. We did this by using the TYPE = COMPLEX option in the ANALYSIS command of Mplus and specified the weight and replicate weight variables in the data.

Results

Table 1 displays the sociodemographic, clinical, and cancer-related characteristics of the sample and is representative of the US population of breast and colorectal cancer survivors.

Table 1.

Respondent sociodemographic, clinical, and cancer-related characteristics

| N (weighted %a) | |

|---|---|

| Cancer type | |

| Breast | 158 (73.8) |

| Colorectal | 54 (26.2) |

| Time since completing treatment | |

| < 1 year | 19 (10.0) |

| 1–5 years | 57 (23.1) |

| 5–10 years | 59 (26.2) |

| >10 years | 77 (40.7) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 24 (8.7) |

| Female | 184 (91.3) |

| Age group | |

| 18–49 | 8 (3.1) |

| 50–64 | 70 (37.9) |

| 65–74 | 69 (27.2) |

| 75+ | 60 (31.8) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 25 (14.8) |

| High school graduate | 57 (27.6) |

| Some college | 61 (28.7) |

| College graduate or more | 66 (28.8) |

| Race | |

| NH White | 132 (82.1) |

| NH Black | 32 (2.8) |

| Hispanic | 15 (1.1) |

| NH other | 11 (1.4) |

| Income | |

| Less than $20,000 | 54 (25.1) |

| $20,000 to < $35,000 | 37 (17.4) |

| $35,000 to < $50,000 | 24 (8.7) |

| $50,000 to < $75,000 | 28 (19.3) |

| $75,000 or More | 43 (29.5) |

| Health insurance | |

| Yes | 199 (95.0) |

| No | 10 (5.0) |

Sample and replicate weights were applied to account for the complex survey design and to ensure estimates are representative of the US population. Some values may not equal 100

The majority of the sample was non-Hispanic white, breast cancer survivors, over the age of 50, with a high school degree or higher. Nearly the entire sample reported having health insurance, and more than half had an income less than $50,000.

Table 2 characterizes the prevalence of survivors receiving an SCP and descriptive statistics for outcomes of SCP delivery identified in our conceptual framework.

Table 2.

Description of HINTS variables

| Mean (SE) or frequency (weighted %a) | |

|---|---|

| Receipt of SCP | |

| Yes | 86 (38.1) |

| No | 123 (61.9) |

| Patient-centered communicationb | 20.7 (0.3) |

| Health self-efficacyc | 3.7 (0.1) |

| Lifestyle behaviors | |

| Aerobic physical activity | |

| 0 min/week | 84 (39.6) |

| 0–149 min/week | 76 (32.7) |

| >150 mins/week | 51 (27.7) |

| Fruit/vegetable intake | |

| < 3–5 servings/day | 84 (33.1) |

| > 3–5 servings/day | 128 (66.9) |

| Tobacco use | |

| Never | 128 (62.0) |

| Former or current | 82 (38.0) |

| Physical health (PH) | |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 28.7 (0.9) |

| Number of chronic conditions | 1.7 (0.1) |

| Self-reported physical healthc | 3.1 (0.1) |

SD, standard deviation

Sample and replicate weights were applied to account for the complex survey design and to ensure estimates are representative of the US population

Overall score of the sum of six items on a 4-point Likert scale with higher scores indicate higher values on construct (range of scores 9–24)

5-point Likert scale with higher scores indicating higher values on construct (range of scores 1–5)

Almost a third of respondents indicated that they did not receive an SCP from their provider although they reported high levels of PCC and felt confident in their ability to manage their health. Nearly 72.3% of breast and colorectal cancer survivors were not meeting the recommended NCCN guidelines for physical activity but 66.9% were meeting guidelines for fruit and vegetable intake and 62.0% report never smoking. Despite the sample reporting an average of two chronic conditions in addition to cancer and BMIs within the overweight range, breast and colorectal survivors reported their perceived overall health to be good at 3.1.

Confirmatory factor analysis

Our CFA assessed the adequacy of the hypothesized measurement model consisting of two latent variables and six manifest variables. The proposed measurement model fit the data adequately well (Table 3). The standardized factor loadings for physical activity and fruit/vegetable intake were significant and above 0.45. Smoking status did not load significantly onto health behaviors but was retained based on empirical support and to identify the latent structure. The standardized factor loadings for the items loading onto physical health were statistically significant and above 0.45, suggesting that all indicators were moderately correlated with the latent factor with which they were hypothesized to be related. Next, we examined the intercorrelations between the latent constructs and found there to be a significant correlation between physical health and health behaviors (b = 0.63, p value < 0.01) suggesting that the constructs hypothesized to represent distinct phenomena are closely related and may not be distinct. As a result, health behaviors and physical health both served as the final outcomes of the hypothesized structural model.

Table 3.

Standardized factor loadings for latent structure for lifestyle behaviors and physical health

| Parameters | 17 |

|---|---|

| Fit indices | |

| Chi-square p value | 0.23 |

| RMSEA | .04 |

| CFI | 0.96 |

| WRMR | 0.49 |

| Standardized item loadings | b (SE) |

| Health behaviors (HB) | |

| PA | 0.96 (0.18)*** |

| Smoke | 0.12(0.16) |

| FV | 0.45 (0.13)*** |

| Physical health (PH) | |

| Self-reported health | 0.59 (0.10)*** |

| BMI | −0.47 (0.12)*** |

| # of chronic conditions | −0.65 (0.08)*** |

| PH with HB | 0.63 (0.15)*** |

p value < 0.05

p value < 0.01

Final structural model

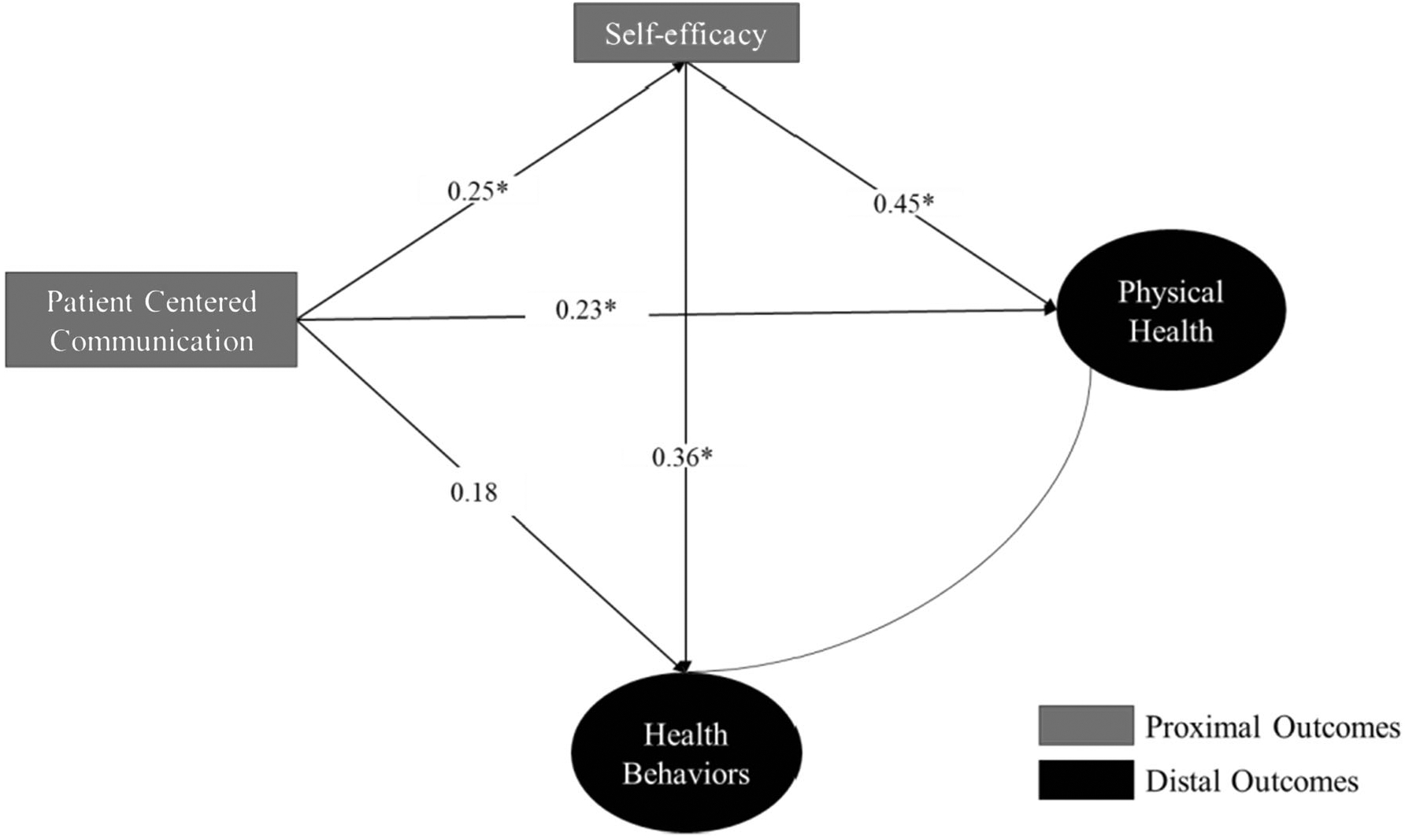

We tested the full a priori hypothesized structural model (Fig. 1) and found that the model did not fit our sample of breast and colorectal cancer survivors well and that the total and direct effects of SCPs to hypothesized outcomes was not significant. As a result, SCP receipt was removed from the final structural model and PCC served as the primary predictor. The results of the final structural model with the standardized regression coefficients are presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Standardized results for the final structural model. A single asterisk indicates significance at p < 0.05

After removing SCP receipt, the overall model fit improved with a chi-square of 28.379 (df = 16, p value = 0.03), RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = .88, and WRMR = 0.73. Table 4 provides the overall fit statistics with the standardized direct, indirect, and total effects of the final model. PCC had a significant direct effect on health self-efficacy and physical health but not on health behaviors. Health self-efficacy had a significant direct effect on physical health and health behaviors, but we did not find any significant indirect effects via health self-efficacy.

Table 4.

Standardized total, direct, and indirect effects

| b (SE) | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-centered communication to physical health | ||

| Total effect | 0.34 (0.11) | < 0.01 |

| Indirect effect | 0.11 (0.06) | 0.06 |

| Direct effect | 0.23 (0.12) | 0.05 |

| Patient-centered communication to health behaviors | ||

| Total effect | 0.27 (0.12) | 0.02 |

| Indirect effect | 0.09 (0.07) | 0.21 |

| Direct effect | 0.18 (0.13) | 0.14 |

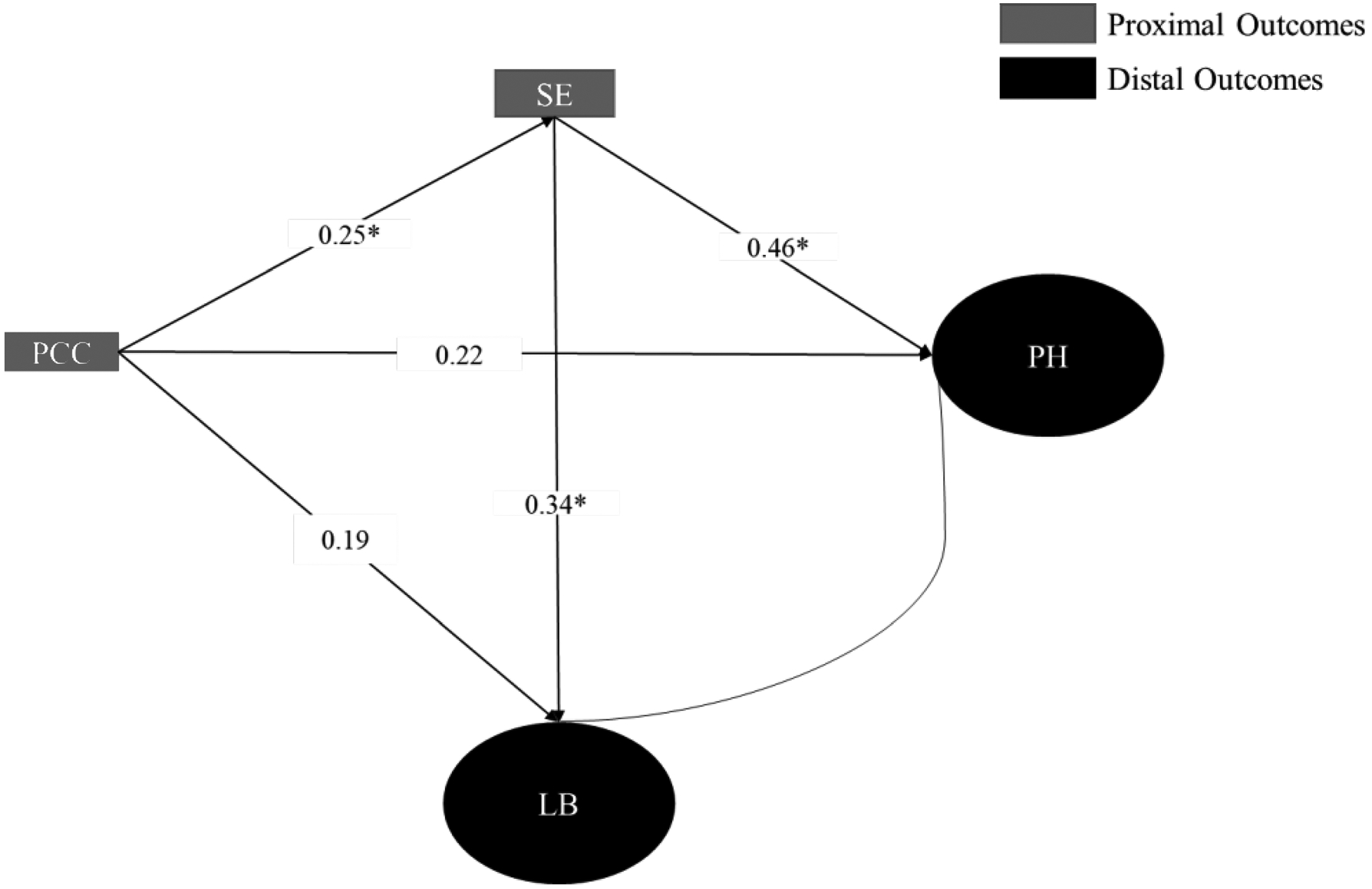

Since the indirect effect of PCC on physical health via health self-efficacy was approaching significance and the significant direct effect of PCC on physical health was borderline, we tested the structural model in a larger sample of breast and colorectal cancer without restricting for completion of active treatment (Appendix 2). The point estimates in both models were similar but the direct effect of PCC on physical health was no longer significant while the indirect effect of PCC on physical health via health self-efficacy was significant. This finding suggests that the effect of PCC on physical health may be completely mediated by health self-efficacy.

Discussion

To our knowledge, these analyses are the first attempt to simultaneously test hypothesized pathways linking the receipt of an SCP to key survivor-level outcomes using a nationally representative sample of breast and colorectal cancer survivors. Overall, we found that our hypothesize model—informed by existing frameworks and evidence from observational studies—adequately fit a sample of breast and colorectal cancer survivors after removing the receipt of an SCP from the model. Our findings also emphasize the role of PCC in survivorship care and build upon the evidence regarding the mechanisms through which PCC affects survivor-level outcomes [17, 21]. These findings support that receiving an SCP alone is unlikely to influence survivor-level outcomes and the need to establish comprehensive models of survivorship care that focus on improving communication between the survivors and care teams [8, 10].

Engaging survivors and clinical care teams in PCC is particularly important to the quality of the care experiences of survivors, who face challenges relating to the management of late and long-term effects [14, 17, 21, 41]. In fact, medical payment programs consider care team communication as an indicator of patient-centered care [17, 42, 43]. We found that PCC had a significant direct effect on health self-efficacy and physical health and secondary analyses suggest that health self-efficacy may mediate the effect of PCC on physical health [17, 21, 44–46]. Health self-efficacy is central to survivors managing the consequences of cancer and its treatment, understanding how and when to seek support, recognizing, and reporting signs and symptoms, and adhering to lifestyle and clinical recommendations that promote survival [45, 47, 48]. Indeed, our findings support the effect of health self-efficacy on lifestyle behaviors and physical health [44–46]. Yet, few interventions promoting self-management are facilitated by care teams and survivors becoming increasingly responsible for self-managing their health and for adopting behaviors that can facilitate recovery and to minimize late effect risks [45, 49, 50]. Future research should explore ways to integrate PCC and self-management interventions into the survivorship care models to promote improvements in distal outcomes.

This study is not without limitations. The cross-sectional nature of the study limited our ability to make causal inferences from our findings or account for the timing of the exposure, mediators, and outcome variables. We assumed all variables were stable moving in a single direction, although the relationship among some variables may be bidirectional. The HINTS survey is also self-report, potentially resulting in over-reporting and recall bias. Our sample size also limited our ability to test meaningful differences in the structural model by key subgroups such as underserved populations, race/ethnic minorities, and cancer site. Future studies should measure outcomes identified in this study and assess differences in the structural model by cancer site and within underrepresented populations who bear a disproportionate burden of cancer and challenges following active treatment.

The variables and responses coded in the HINTS dataset may not capture the complexity of outcomes or the relationship among variables. First, the item serving as a proxy of SCP receipt asked about the receipt of treatment summaries—one component of an SCP but the most dominant. In addition, we were unable to measure immediate outcomes of SCP receipt such as knowledge in survivorship care that may be antecedent to and inform subsequent communication exchanges. There may also be variability in the timing between the receipt of an SCP and the completion of treatment. Given that the majority of the sample completed treatment over 5 years ago, it is possible that the survivors either did not receive or recall receiving an SCP contributing to null findings. Furthermore, the impact of SCPs may be lost as part of the information exchange captured by the PCC items. Therefore, future studies should assess proximal or process outcomes of SCP delivery in survivors who recently completed active treatment such as an increase in knowledge and the number of patients receiving an SCP. Our measure of health self-efficacy consisted of a single item that was broadly applicable to one’s overall health and the PCC items utilized in this study may not comprehensively capture the complexity of the six core functions of PCC in cancer survivorship and do not distinguish between types of providers (oncologists vs. primary care). There is a need for prospective studies with robust measures of outcomes to account for the complexities of these relationships and further delineate potential causal pathways. Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that SCPs, by itself, may not be related to better PCC or to more distal health outcomes. Rather, they support the NCI’s revised call to focus more on a comprehensive survivorship care model that includes SCPs that are integrated with care delivery, effective PCC, and better coordination between health care teams [8, 20].

Conclusion

A better understanding of the complex relationships between SCPs and survivor-level outcomes is critical as we continue to improve survivorship care and has implications for how health care systems allocate time and money to the development and receipt of SCPs. To this end, it may be time to move beyond studies that look at SCPs in isolation and instead conduct research in which SCPs are embedded in evaluating the effectiveness of different models of survivorship care [8, 20]. More research is also needed to explore the underlying mechanisms linking the process of survivorship care planning to survivor-level outcomes, in samples that reflect the diversity in survivor populations and clinical settings.

Fig. 3.

HINTS Sample 1 Model

Funding information

This study was supported by the UTHealth School of Public Health Cancer Education and Career Development Program (NCI Grant T32 CA057712).

Appendix 1:

HINTS survey items and analytic categories

| Domain | Item(s) | Response scale(s) | Analysis categories |

|---|---|---|---|

| Receipt of care plan | “Did you ever receive a summary document from your doctor or other health care professional that listed all of the treatment you received for your cancer?” | Yes No |

|

| Patient-centered communication | How often did the doctors, nurses, or other health care professionals you saw during the past 12 months do each of the following: (1) Give you a chance to ask all the health-related questions you had? (Fostering Healing Relationships) (2) Give the attention you needed to your feelings and emotions? (responding to emotions) (3) Involve you in decisions about your health care as much as you wanted? making decisions) (4) Make sure you understood the things you needed to do to take care of your health? (enabling self-management) (5) Explain things in a way you could understand? (exchanging Information) (6) Help you deal with feelings of uncertainty about your health or healthcare? (managing uncertainty). | Always Usually Sometimes Never |

Continuous overall score (range 9–24) with higher scores indicating higher levels of PCC. |

| Health self-efficacy | “Overall, how confident are you about your ability to take good care of your health?” | Completely confident Very confident Somewhat confident A little confident Not confident at all |

Continuous overall score (range 1–5) with higher scores indicating higher levels of self-efficacy. |

| Aerobic physical activity | “In a typical week, how many days do you do any physical activity or exercise of at least moderate intensity, such as brisk walking, bicycling at a regular pace, and swimming at a regular pace?”; “On the days that you do any physical activity or exercise of at least moderate intensity, how long do you typically do these activities?” |

0–7 days a week; Free response |

|

| Fruit consumption | “About how many cups of fruit (including 100% pure fruit juice) do you eat or drink each day? 1 cup of fruit could be: 1. small apple; 1 large banana; 1 large orange; 8 large strawberries; 1 medium pear; 2 large plums; 32 seedless grapes; 1 cup (8 oz.) fruit juice; ½ cup dried fruit; 1 inch-thick wedge of watermelon” |

None ½ cup or less ½ cup to 1 cup 1 cup 1 to 2 cups 2 to 3 cups 3 to 4 cups 4 or more cups |

(Fruit and vegetable consumption combined to create one variable)

|

| Vegetable consumption | “About how many cups of vegetables (including 100% pure vegetable juice) do you eat or drink each day? 1 cup of vegetables could be: 3 broccoli spears; 1 cup cooked leafy greens; 2 cups lettuce or raw greens; 12 baby carrots; 1 medium potato; 1 large sweet potato; 1 large ear of corn; 1 large raw tomato; 2 large celery sticks; 1 cup of cooked beans” |

None, ½ cup or less ½ cup to 1 cup 1 to 2 cups 2 to 3 cups 3 to 4 cups 4 or more cups |

|

| Tobacco use | “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” “How often do you smoke cigarettes now?’ |

Yes No Every day Some days Not at all |

|

| Self-reported health | “In general, would you say your health is…” | Excellent Very good Good Fair Poor |

Continuous overall score (range 1–5) with higher scores indicating higher level of self-reported health |

| BMI | Self-reported height and weight | Free response | Derived continuous measure from HINTS |

| Number of chronic conditions | Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you had any of the following medical conditions: Diabetes or high blood sugar Hypertension or high blood pressure A heart condition Chronic lung disease Arthritis or rheumatism. |

Yes No |

Items summed to create a continuous measure |

Appendix 2: Secondary analyses

Sample characteristics and SEM in those diagnosed with breast and colorectal cancer compared to breast and colorectal cancer survivors who completed active treatment.

HINTS Sample 1:

Includes respondents diagnosed with breast and/or colorectal cancer. Defines survivors as those diagnosed with cancer.

HINTS Sample 2:

Includes respondents diagnosed with breast and/or colorectal cancer who have received and completed treatment for cancer.

| Participant characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| HINTS sample 1 (N = 273) N (weighted %a) |

HINTS sample 2 (N = 212) | |

| Cancer type | ||

| Breast | 200 (70.9) | 158 (73.8) |

| Colorectal | 71 (29.1) | 54 (26.2) |

| Time since completing Tx | ||

| < 1 year | 19 (8.3) | 19 (10.0) |

| 1–5 years | 57 (19.1) | 57 (23.1) |

| 5–10 years | 59 (21.7) | 59 (26.2) |

| >10 years | 77 (33.7) | 77 (40.7) |

| Still receiving treatment | 30 (17.3) | - |

| Missing | 31 | - |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 32 (15.4) | 24 (8.7) |

| Female | 230 (84.6) | 184 (91.3) |

| Missing | 9 | 4 |

| Age group | ||

| 18–49 | 12 (4.5) | 8 (3.1) |

| 50–64 | 92 (40.9) | 70 (37.9) |

| 65–74 | 77 (25.1) | 69 (27.2) |

| 75+ | 80 (29.4) | 60 (31.8) |

| Missing | 10 | 5 |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 33 (16.2) | 25 (14.8) |

| High school graduate | 73 (28.1) | 57 (27.6) |

| Some college | 74 (27.0) | 61 (28.7) |

| College graduate or more | 84 (28.7) | 66 (28.8) |

| Missing | 7 | 3 |

| Race | ||

| NH White | 155 (74.9) | 132 (82.1) |

| NH Black | 40 (14.3) | 32 (2.8) |

| Hispanic | 24 (6.7) | 15(1.1) |

| NH other | 15 (4.2) | 11 (1.4) |

| Missing | 37 | 22 |

| Income | ||

| Less than $20,000 | 65 (24.0) | 54 (25.1) |

| $20,000 to < $35,000 | 50 (19.6) | 37 (17.4) |

| $35,000 to < $50,000 | 31 (10.2) | 24 (8.7) |

| $50,000 to < $75,000 | 35 (16.9) | 28 (19.3) |

| $75,000 or more | 52 (29.3) | 43 (29.5) |

| Missing | 38 | 26 |

| Health insurance | ||

| Yes | 253 (94.6) | 199 (95.0) |

| No | 13 (5.4) | 10 (5.0) |

| Missing | 5 | 3 |

Sample and replicate weights were applied to account for the complex survey design and to ensure estimates are representative of the US population. Some values may not equal 100

| Description of HINTS variables | ||

|---|---|---|

| HINTS sample 1 (N = 273) Mean (SD) or N (weighted %a) |

HINTS sample 2 (N = 212) | |

| Receipt of SCP | ||

| Yes | 90 (37.7) | 86 (38.1) |

| No | 131 (62.3) | 123 (61.9) |

| Patient-centered communicationb | 20.8 (0.3) | 20.7 (0.3) |

| Health self-efficacyc | 3.7 (0.1) | 3.7 (0.1) |

| Aerobic physical activity | ||

| 0 min/week | 117 (45.1) | 84 (39.6) |

| 0–149 min/week | 94 (32.1) | 76 (32.7) |

| >150 min/week | 59 (22.8) | 51 (27.7) |

| Fruit/vegetable intake | ||

| < 3–5 servings/day | 112 (32.5) | 84 (33.1) |

| > 3–5 servings/day | 161 (67.5) | 128 (66.9) |

| Tobacco use | ||

| Never | 164 (60.0) | 128 (62.0) |

| Former or current | 104 (40.0) | 82 (38.0) |

| BMI | 29.0 (0.7) | 28.7 (0.9) |

| Number of chronic conditions | 1.6 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) |

| Self-reported physical healthc | 2.9 (0.1) | 3.1 (0.1) |

SD, standard deviation

Sample and replicate weights were applied to account for the complex survey design and to ensure estimates are representative of the US population.

Overall score of the sum of six items on a 4-point Likert scale with higher scores indicate higher values on construct (max score 24)

5-point Likert scale with higher scores indicating higher values on construct

| Standardized factor loadings for latent structure for lifestyle behaviors and physical health | ||

|---|---|---|

| HINTS sample 1 (N = 273) | HINTS sample 2 (N = 212) | |

| Parameters | 17 | 17 |

| Fit indices | ||

| Chi-square p value | 0.29 | 0.23 |

| RMSEA | 0.03 | .04 |

| CFI | 0.98 | 0.96 |

| WRMR | 0.49 | 0.49 |

| Standardized item loadings | b (SE) | |

| Health behaviors | ||

| PA | 0.98 (0.18)*** | 0.96 (0.18)*** |

| Smoke | 0.19 (0.14) | 0.12 (0.16) |

| FV | 0.41 (0.14)*** | 0.45 (0.13)*** |

| Physical health | ||

| Self-reported health | 0.55 (0.08)*** | 0.59 (0.10)*** |

| BMI | − 0.53 (0.11)*** | − 0.47 (0.12)*** |

| # of chronic conditions | − 0.48 (0.08)*** | − 0.65 (0.08)*** |

| PH with HB | 0.69 (0.14)*** | 0.63 (0.15)*** |

p value < 0.05

p value < 0.01

| Standardized total, direct, and indirect effects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HINTS sample 1 (N = 273) | HINTS sample 2 (N = 212) | |||

| b (SE) | p value | b (SE) | p value | |

| Patient-centered communication to physical health | ||||

| Total effect | 0.33 (0.12) | 0.01 | 0.34 (0.11) | < 0.01 |

| Indirect effect | 0.12 (0.05) | 0.02 | 0.11 (0.06) | 0.06 |

| Direct effect | 0.22 (0.12) | 0.08 | 0.23 (0.12) | 0.05 |

| Patient-centered communication to health behaviors | ||||

| Total effect | 0.27 (0.12) | 0.02 | 0.27 (0.12) | 0.02 |

| Indirect effect | 0.09 (0.06) | 0.16 | 0.09 (0.07) | 0.21 |

| Direct effect | 0.19 (0.11) | 0.12 | 0.18 (0.13) | 0.14 |

HINTS sample 1 model

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.American College of Surgeons. Cancer program standards 2012: ensuring patient-centered care. In:2012.

- 2.American Cancer Society. National Cancer Survivorship Resource Center systems policy and practice: Clinical Survivorship care overview. Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayer DK, Shapiro CL, Jacobson P, McCabe MS. Assuring quality cancer survivorship care: we’ve only just begun. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book Am Soc Clin Oncol Meeting. 2015:e583–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganz PA. Institute of Medicine report on delivery of high-quality cancer care. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(3):193–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cowens-Alvarado R, Sharpe K, Pratt-Chapman M, Willis A, Gansler T, Ganz PA, et al. Advancing survivorship care through the National Cancer Survivorship Resource Center. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(3):147–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. Committee on cancer survivorship: improving care and quality of life, institute of medicine and national research council. In: Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hewitt ME, Bamundo A, Day R, Harvey C. Perspectives on post-treatment cancer care: qualitative research with survivors, nurses, and physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(16):2270–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobsen PB, DeRosa AP, Henderson TO, et al. Systematic review of the impact of cancer survivorship care plans on health outcomes and health care delivery. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(20):2088–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salz T, Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS, Layne TM, Bach PB. Survivorship care plans in research and practice. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(2):101–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayer DK, Birken SA, Check DK, Chen RC. Summing it up: an integrative review of studies of cancer survivorship care plans (2006–2013). Cancer. 2015;121(7):978–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blinder VS, Norris VW, Peacock NW, Griggs JJ, Harrington DP, Moore A, et al. Patient perspectives on breast cancer treatment plan and summary documents in community oncology care: a pilot program. Cancer. 2013;119(1):164–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill-Kayser CE, Vachani C, Hampshire MK, Metz JM. High level use and satisfaction with internet-based breast cancer survivorship care plans. Breast J. 2012;18(1):97–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolfe A Institute of Medicine Report: Crossing the quality chasm: a new health care system for the 21st century. Policy, Politics Nursing Pract. 2001;2(3):233–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epstein R, Street RL. Patient-centered communication in cancer care: promoting healing and reducing suffering. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; NIH Publication No. 07–6225; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arora NK. Interacting with cancer patients: the significance of physicians’ communication behavior. Soc Sci Med (1982). 2003;57(5): 791–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ : Canadian Med Assoc J. 1995;152(9): 1423–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Street RL Jr, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(3):295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casillas J, Syrjala KL, Ganz PA, Hammond E, Marcus AC, Moss KM, et al. How confident are young adult cancer survivors in managing their survivorship care? A report from the LIVESTRONG™ Survivorship Center of Excellence Network. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(4):371–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill-Kayser C, Vachani C, Hampshire M, Di Lullo G, Metz J. Positive impact of internet-based survivorship care plans on healthcare and lifestyle behaviors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84(3):S211–2. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parry C, Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Alfano CM, Rowland JH. Can’t see the forest for the care plan: a call to revisit the context of care planning. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(21):2651–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lafata JE, Shay LA, Winship JM. Understanding the influences and impact of patient-clinician communication in cancer care. Health Expect. 2017;20(6):1385–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Street RL Jr, Mazor KM, Arora NK. Assessing patient-centered communication in cancer care: measures for surveillance of communication outcomes. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(12):1198–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Kramer JL, Rowland JH, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(4):271–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blanch-Hartigan D, Chawla N, Beckjord EI, Forsythe LP, de Moor JS, Hesse BW, et al. Cancer survivors’ receipt of treatment summaries and implications for patient-centered communication and quality of care. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(10):1274–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arora NK, Reeve BB, Hays RD, Clauser SB, Oakley-Girvan I. Assessment of quality of cancer-related follow-up care from the cancer survivor’s perspective. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(10):1280–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blanch-Hartigan D, Chawla N, Moser RP, Rutten LJF, Hesse BW, Arora NK. Trends in cancer survivors’ experience of patient-centered communication: results from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(6): 1067–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rutten LJF, Hesse BW, Sauver JLS, et al. Health self-efficacy among populations with multiple chronic conditions: the value of patient-centered communication. Adv Ther. 2016;33(8):1440–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denlinger CS, Ligibel JA, Are M, Baker KS, Demark-Wahnefried W, Dizon D, et al. Survivorship: healthy lifestyles, version 2.2014. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2014;12(9):1222–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ufholz KE, Harlow LL. Modeling multiple health behaviors and general health. Prev Med. 2017;105:127–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de la Haye K, D’Amico EJ, Miles JNV, Ewing B, Tucker JS. Covariance among multiple health risk behaviors in adolescents. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e98141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yanuar F, Ibrahim K, Jemain AA. On the application of structural equation modeling for the construction of a health index. Environ Health Prev Med. 2010;15(5):285–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muthén L, Muthén B. Statistical analysis with latent variables using Mplus. Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schreiber JB. Core reporting practices in structural equation modeling. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2008;4(2):83–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schreiber JB, Nora A, Stage FK, Barlow EA, King J. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: a review. J Educ Res. 2006;99(6):323–38. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muthén B, Kaplan D, Hollis M. On structural equation modeling with data that are not missing completely at random. Psychometrika. 1987;52(3):431–62. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mplus User’s Guide [computer program]. Los Angeles, CA: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inc SI. SAS 9.4 [Computer software]. In: Author; Cary, NC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moser RP, Naveed S, Cantor D, et al. Integrative analytic methods using population-level cross-sectional data. National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Austin JD, Robertson MC, Shay LA, Balasubramanian BA. Implications for patient-provider communication and health self-efficacy among cancer survivors with multiple chronic conditions: results from the Health Information National Trends Survey. J Cancer Survivorship : Res Pract. 2019;13(5):663–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levinson W, Lesser CS, Epstein RM. Developing physician communication skills for patient-centered care. Health Affairs (Project Hope). 2010;29(7):1310–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McFarland DC, Johnson Shen M, Holcombe RF. Predictors of satisfaction with doctor and nurse communication: a national study. Health Commun. 2017;32(10):1217–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stacey FG, James EL, Chapman K, Courneya KS, Lubans DR. A systematic review and meta-analysis of social cognitive theory-based physical activity and/or nutrition behavior change interventions for cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(2):305–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Foster C, Breckons M, Cotterell P, Barbosa D, Calman L, Corner J, et al. Cancer survivors’ self-efficacy to self-manage in the year following primary treatment. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(1):11–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCorkle R, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, Schulman-Green D, Schilling LS, Lorig K, et al. Self-management: enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(1):50–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. Jama. 2002;288(19):2469–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bandura A Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1986;1986. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Foster C, Fenlon D. Recovery and self-management support following primary cancer treatment. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(1):S21–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boland L, Bennett K, Connolly D. Self-management interventions for cancer survivors: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(5):1585–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]