Abstract

Introduction

Hispanic adolescents in the U.S. are disproportionately affected by overweight and obesity compared with their non-Hispanic white counterparts. This study examines the efficacy of an evidence-based family intervention adapted to target obesity-related outcomes among overweight/obese Hispanic adolescents compared with prevention as usual.

Study design

This study was an RCT.

Setting/participants

Participants were overweight/obese Hispanic adolescents (n=280, mean age=13.01 [SD=0.82] years) in the 7th/8th grade and their primary caregivers. Primary caregivers were majority female legal guardians (88% female, mean age=41.88 [SD=6.50] years).

Intervention

Participants were randomized into the family-level obesity-targeted intervention or referral to community services offered for overweight/obese adolescents and families (condition). Data collection began in 2015.

Main outcome measures

Primary outcomes included dietary intake (e.g., reduction of sweetened beverages) and past-month moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. Secondary outcomes were BMI and family functioning assessed among adolescents and primary caregivers.

Results

Study analyses (2019) indicated no significant intervention effects for adolescents’ primary outcomes. Intervention effects were found for parents’ intake of fresh fruit and vegetables (β=0.12, 95% CI=0.02, 0.23), added sugar (β= −0.11, 95% CI= −0.22, −0.004), and sweetened beverages (β= −0.12, 95% CI=−0.23, −0.02), and parents showed decreased BMI (β= −0.05, 95% CI= −0.11, −0.01) at 6 months post-baseline compared with usual prevention. Intervention effects were found for adolescent family communication (β=0.13, 95% CI=0.02, 0.24), peer monitoring (β=0.12, 95% CI=0.01, 0.23), and parental involvement (β=0.16, 95% CI=0.06, 0.26) at 6 months post-baseline compared with prevention as usual.

Conclusions

This intervention was not effective in improving overweight/obesity-related outcomes in adolescents. The intervention was effective in improving parents’ dietary intake and BMI; however, the effects were not sustained long term. Other intervention strategies (e.g., booster session, increased nutritional information) may be necessary to sustain beneficial effects and extend effects to adolescent participants.

Trial registration

This study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov NCT03943628.

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of overweight/obesity remains disproportionally high among the U.S. pediatric population. This is particularly true among Hispanic children and adolescents, whose prevalence rates are substantially higher than their non-Hispanic white and Asian counterparts, (38.2% vs 19.1% and 12.1%,) and similar to non-Hispanic black adolescents (35.0%).1,2 Hispanic youth diets often do not adhere to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.3 Moreover, only 26% of Hispanic youth report meeting the guidelines of 60 minutes of physical activity a day.4 Despite the fact that many Hispanic youth are overweight or obese, there is a dearth of evidence-based obesity prevention interventions for this population that include culturally competent strategies, such as ethnically relevant diet recommendations or Spanish-language intervention materials, to target healthful eating and physical activity practices.5,6

The critical role families play in healthy adolescent development, particularly in Hispanic families, has been well established in the literature.7 Positive family functioning is related to a healthy family system8; thus, it is not surprising that family functioning is also related to a number of health behaviors and conditions including physical activity, dietary intake, and BMI.9–12 Previous studies have highlighted the role that parents specifically have in influencing adolescent behaviors including providing healthy meals, reinforcing physical activity, and modeling healthy lifestyle behavioral habits that improve overweight and obesity outcomes.13–15 Therefore, the family, perhaps the most fundamental social system influencing human development,16,17 may be an influential source in impacting adolescent physical activity and dietary intake. Further, it is not surprising that there is emerging literature focusing on family-level interventions for childhood obesity prevention.18 Despite an increase in RCTs of family-based interventions that include healthy weight behaviors, there are still relatively few focused exclusively on Hispanic adolescents.18

Familias Unidas (United Families) is an evidence-based family intervention developed for the prevention of conduct problems, substance use, and sexual risk behaviors, and has been found to impact these same risk behaviors in multiple RCTs.9,19,20 Familias Unidas was designed for Hispanic families and is grounded in the ecodevelopmental framework, which suggests adolescent development is influenced through social ecosystems (i.e., microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem).21,22 The microsystem (the most proximal system influencing development) encompasses the family system. Further existing theories, such as the family systems theory, suggests that factors within the family system may have reciprocal relationships, in which they interact to influence parent-adolescent relationships and individual behaviors.23,24 As a result, the mechanistic impact of Familias Unidas on adolescent outcomes has been primarily through improvements in the family system and family functioning behaviors, including parental involvement and parent–adolescent communication,9 the same mechanisms that have been found to be related to physical activity and dietary intake in other studies.11,25 Further, Familias Unidas is shown to have crossover effects on internalizing symptoms and suicidal behaviors, which are not targeted outcomes of the intervention.26,27

Therefore, the aims of this RCT are to examine the relative efficacy of Familias Unidas, adapted to target obesity (Familias Unidas for Health and Wellness [FUHW]), compared with prevention as usual, in improving the quality of dietary intake and increasing physical activity among Hispanic adolescents who are overweight/obese and their parents. Secondarily, this study also examines changes in BMI and improving family functioning via FUHW, compared with prevention as usual, for Hispanic adolescents who are overweight/obese and their parents. It is hypothesized that FUHW is efficacious compared with the control condition at 6 months post-baseline and across 24-month trajectories in improving quality dietary intake (i.e., decreases in sugar-sweetened beverages and other added sugars, and increases in fruit and vegetable intake), increasing past-month moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, and decreasing BMI. Further, it is hypothesized that FUHW is efficacious compared with the control condition at 6 months post-baseline in improving family functioning behaviors (i.e., family communication, peer monitoring, parental involvement, and positive parenting) among Hispanic adolescents who are overweight/obese and their parents.

METHODS

Study Sample

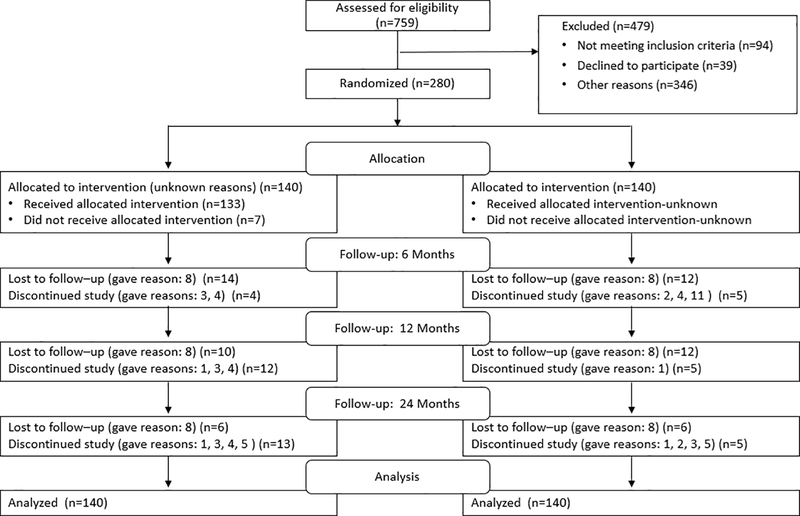

This study used an RCT design to evaluate the relative efficacy of FUHW among a sample of 280 Hispanic overweight and obese adolescents and their primary caregivers compared with prevention as usual.28 Study staff recruited participants beginning in 2015. Adolescents and their primary caregiver were eligible to participate in the study if the Hispanic adolescent: (1) was a student in the 7th/8th grade, (2) had a BMI ≥85th percentile adjusted for age and sex, (3) lived with an adult primary caregiver willing to participate in the 2-year study, and (4) had plans to remain a resident of the geographic study catchment area (i.e., South Florida) during the study period. Participants were excluded from the study if: (1) adolescents had a BMI <85th percentile adjusted for age and sex and (2) parent responses on a physical activity readiness questionnaire indicated a serious health issue (e.g., a heart condition that requires physician approval before engaging in physical activity, general chest pain, dizziness or loss of consciousness, bone or joint issues) for either parents or adolescents. If a serious health issue was reported, physician approval was needed to participate. After eligibility was established, and families were consented/assented, participants were randomized, single-blinded, to FUHW (experimental condition) or prevention as usual (comparison condition) using urn randomization29 and concealment of allocation procedures (i.e., participants chose a sealed, opaque envelope from a box at random determining their condition assignment) (Figure 1). Families in the prevention as usual control condition were referred to their local health department’s health initiative Internet page and the usual programs they offer to reflect the typical services that overweight and obese adolescents may receive in their own community. Parents received $50, $75, $80, and $85 for completing baseline and 6-, 12-, and 24-month post-baseline assessments, respectively. Adolescents received one movie ticket at each assessment. All measures were translated and back-translated and were offered to participants in either English or Spanish. This study was approved by the University of Miami and Miami Dade County Public School System IRBs.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flowchart.

Note: The reasons participants were lost to follow-up or discontinued the study were (1) work issues, (2) time issues, (3) moved out of Miami, (4) declined to continue in the study, (5) health issues, (6) adolescent dropped out of school, (7) did not want to do assessment, (8) unable to reach the family, (9) out of country, (10) did not like the study, (11) adolescent declined to continue in the study.

Intervention

The process of adapting Familias Unidas, an intervention targeted toward reducing substance use and sexual risk behaviors, to target obesogenic behaviors has been described in detail elsewhere.28 The adapted intervention, FUHW, was developed with the input from experts in pediatric obesity, exercise physiology, dietetics, and nutrition, such that these experts provided intervention modifications aligned with existing evidence-based physical activity curriculums. The research team also adapted the intervention through an iterative process based on input from Hispanic adolescents and parents who participated in a series of focus groups conducted before, during, and after an initial pilot test of the adapted intervention. Participants in the focus groups responded to questions such as: Have you ever tried to make changes in the way you or your family eats or exercises? The final version of the adapted intervention was based on findings from the focus groups, with focus group participants stating they would enjoy interactive nutrition sessions and increased parental involvement in physical activity. FUHW maintained fidelity to Familias Unidas’ core intervention components and overall structure, including following the ecodevelopmental framework to organize and address the risk and protective factors associated with adolescent overweight and obesity from the microsystem (e.g., family) to the macrosystem (e.g., Hispanic cultural values and norms). FUHW also followed the mechanisms of change developed in the original Familias Unidas intervention as a means of supporting improvements in adolescent outcomes through Hispanic culturally relevant constructs, such as parental involvement and family cohesion. Apart from the original Familias Unidas intervention content, FUHW included additional content focused on physical activity and nutrition for parents, adolescent participation in a physical activity facilitated by bilingual park coaches and fitness instructors, and joint parent–adolescent participation in physical activity and nutrition education and skill-building activities.28

As a selective and indicated preventive intervention, FUHW is a 12-week intervention with 2.5-hour group sessions (8 total) and 1-hour family sessions (4 total), each taking place once a week (Appendix Table 1).28 The first 1.5 hours of the group sessions involved facilitators who initiated discussions between groups of parents and encouraged role-playing related to adolescent healthy lifestyle behaviors (e.g., nutrition), risky behaviors (e.g., drug use), and positive parenting behaviors (e.g., open family communication), without the adolescents present in the group session. Sessions were led by two bilingual facilitators who had training in using problem-posing, participatory learning, which includes encouraging parents’ active discussion in group sessions. Group session discussions, in turn, help parents understand how and why they must be active in protecting adolescents from participating in risky behaviors.28 While parents participated in the 1.5 hours of the group sessions, adolescents participated in outdoor physical activities led by local park coaches trained in an evidence-based physical activity afterschool program, named Sports, Play, and Active Recreation.30 Family engagement in healthy activities was emphasized during the second hour of group sessions, where both parents and adolescents were included. Activities such as hands-on nutrition education and training (i.e., cooking, recipe preparation) were facilitated by a local non-profit organization with experience serving the local Hispanic community and fitness classes (e.g., yoga, Zumba) taught by certified instructors. Group activities were designed to provide parents with an opportunity to practice the skills learned during the parent group sessions with their adolescents and to demonstrate entertaining and healthy activities that parents and adolescents can participate in as a family. During the four family sessions, facilitators met individually with each family to practice the skills the parent had learned during the group sessions with their adolescent. For example, parents and adolescents were guided through discussion topics and participated in role-playing activities related to adolescents’ lifestyle and risk behaviors. Regarding attendance, 71% of families attended all 12 group and family sessions, with 5% of families not attending any intervention session.31

Measures

The dietary intake of parents and adolescents was assessed using the Dietary Screener Questionnaire of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.32 The questionnaire asks participants how much of 22 specific foods or beverage items they consumed in the past month. There were eight response choices: never, 1 time last month, 2–3 times last month, 1 time per week, 2 times per week, 3–4 times per week, 5–6 times per week, 1 time per day, 2 or more times per day. Items reflect both high-quality (fruit, vegetable, whole grains) and low-quality (doughnuts, candy) dietary choices. The added sugars dietary factor consists of soda, fruit drinks, cookies, cake and pie, doughnuts, ice cream, sugar/honey in coffee/tea, candy, and cereal and cereal type. The fruit and vegetable dietary factor consists of fruit, fruit juice, salad, fried potatoes, other potatoes, dried beans, other vegetables, tomato sauce, salsa, and pizza. The sweetened beverages factor consists of soda, fruit drinks, and sugar/honey in coffee/tea.

For the current analyses, algorithms developed by the National Cancer Institute for use with the Dietary Screener Questionnaire (available at https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/nhanes/dietscreen/scoring/current/#scoring) were used to calculate daily added sugar consumption (unit=a teaspoon), daily fruit and vegetable consumption (unit=a cup), and daily sweetened beverages (unit=a teaspoon). Following George and Mallery,33 daily added sugar consumption and sweetened beverages were positively skewed and were log-transformed for analyses. Development and evaluation of the Dietary Screener Questionnaire has been described elsewhere.32

Physical activity for parents and adolescents was measured using WHO’s34 Global Physical Activity Questionnaire, previously used in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.35 The Global Physical Activity Questionnaire assesses the adolescents’ self-report of physical activity in regards to its duration (i.e., days, hours, minutes), intensity (i.e., moderate, vigorous), type of physical activity (e.g., brisk walking, bicycling, swimming), and sedentary behaviors (e.g., watching TV). Using adolescents’ self-report on the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire34 and the WHO analysis guide, work (i.e., paid or unpaid work, household chores, yard work) and recreational activities were assessed to determine levels of physical activity. A summed score of the total minutes of PA levels during a typical week was used to determine a moderate-to-vigorous physical activity score. To avoid an issue of convergence, physical activity was divided by 100 to reduce the variance of the outcome as suggested by Muthén & Muthén.

Trained research staff (who were also blind to condition assignment) took anthropometric measures using a SECA 217 mobile stadiometer and a SECA 869 digital scale for parents and adolescents. Participants’ height and weight measures were taken with clothes but without shoes. Age- and sex-specific BMI was computed using SAS, version 9.4, available for free download from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. For adolescents, a BMI percentile for sex and age was calculated using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts.36 For parents, the raw score for BMI was used.

Parents and adolescents self-reported on four indicators of family functioning. Subscales from the Parenting Practices Scale were used to assess positive parenting (9 items) and parental involvement (16 items).37 The positive parenting subscale measures parents’ response to good behaviors (adolescent report, α=0.79; parent report, α=0.68). The parental involvement subscale assesses the degree to which a parent is involved in a child’s life (adolescent report, α=0.84; parent report, α=0.73). The Family Relations Scale (3 items) was used to assess family communication (adolescent report, α=0.68; parent report, α=0.79).38 Finally, the Parent Relationship With Peer Group Scale (5 items) was used to assess parental monitoring of peers (adolescent report, α=0.84; parent report, α=0.80) (H Pantin, University of Miami School of Medicine, unpublished observations, 1996).

Statistical Analysis

Using G*power, version 3.1.3,39 a power analysis was conducted to detect the intervention effect at 6 months post-baseline using an ANCOVA model framework. With a sample size of 280 and the α level at 0.05, the analyses had >80% power to uncover a significant intervention effect when the size of effect is small to medium (F=0.15). In addition, using Mplus, version 8.0, Monte Carlo simulation was conducted to calculate power with a latent growth curve model framework.40 With four time points (baseline and 6, 12, and 24 months after baseline), a sample size of 280 at baseline, and assuming that the expected mean trajectories were 0.2 for all targeted outcomes with a 10% attrition rate at each assessment, the study had >80% power to detect a regression coefficient equal to 0.15 in the regression of the slope growth factor on intervention condition. This study expected a moderate effect size (d=0.41).

All longitudinal analyses were conducted after completion of 24-month post-intervention assessments. The authors started performing these longitudinal analyses in March 2019. To examine two aims, two separate analyses were conducted. First, to examine the intervention effects on the two primary outcomes (dietary intake and past month moderate-to-vigorous physical activity) and the two secondary outcomes (BMI and family functioning behaviors) at 6 and 24 months, post-baseline regression analyses were conducted. In the regression analyses, all intervention effects were adjusted after taking into account the effects of same primary and secondary baseline outcomes.

Second, to examine intervention effects on primary and secondary outcomes over 2 years, a series of latent growth curve analyses were conducted.30 In order to take into account non-normal distribution of two count variables (drug and alcohol use), a Poisson distribution was used. The intervention effects on trajectories of the family functioning outcomes over 2 years were not examined because previous research has shown that levels of family functioning behaviors remain relatively stable after initial improvements in family functioning as a result of completing the intervention.41

Intervention effect sizes were reported by dividing the absolute values of regression coefficients (unstandardized b) by the SD of the residuals of outcomes.42 In addition, the pooled incidence rate ratio was used as intervention effects for count variables and was calculated by taking the exponent of the regression coefficient (unstandardized b).43

All other analyses were based on intent to treat. Missing data were addressed by using full information maximum likelihood.44 All analyses were estimated by using Mplus, version 8.0.

RESULTS

Figure 1 shows the CONSORT flow diagram for this trial. There were no differences in attrition rates between the two study conditions across time (χ2=6.05, p=0.11). Demographic characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. Analyses indicated no significant differences at baseline by condition on demographic characteristics and primary and secondary outcomes at baseline. In addition, means and SDs of primary and secondary outcomes are shown in Table 2. The average overall intervention attendance, including parent groups and family sessions, was 8.46 (SD=3.90) sessions of a possible 12 sessions; 5% of participants did not attend any sessions.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics at Baseline

| Characteristic | Total (n=280), mean (SD) or N (%) | Familias Unidas (n=140), mean (SD) or n (%) | Control (n=140), mean (SD) or n (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 13.01 (0.827) | 13.04 (0.868) | 12.99 (0.786) | 0.613 |

| Gender | 0.370 | |||

| Female, n (%) | 146 (52.3) | 69 (49.3) | 77 (55.0) | |

| Country of origin | 0.196 | |||

| Foreign born, n (%) | 100 (35.7) | 55 (39.3) | 45 (32.1) | |

| U.S. born, n (%) | 180 (64.3) | 85 (60.7) | 95 (67.9) | |

| Number of years in U.S. | 0.619 | |||

| <1 year, n (%) | 24 (8.6) | 11 (7.9) | 13 (9.3) | |

| 1–9 years, n (%) | 69 (24.6) | 38 (27.1) | 31 (22.1) | |

| >9 years, n (%) | 185 (66.1) | 91 (65.0) | 94 (67.1) | |

| No response, n (%) | 2 (0.07) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.5) | |

| Parent | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 41.88 (6.50) | 42.09 (6.30) | 41.66 (6.70) | 0.576 |

| Gender | 0.578 | |||

| Female, n (%) | 247 (88.2) | 122 (87.1) | 125 (89.3) | |

| Country of origin | ||||

| Foreign born, n (%) | 255 (91.1) | 126 (90.0) | 129 (92.1) | 0.530 |

| U.S. born, n (%) | 25 (8.9) | 14 (10.0) | 11 (7.9) | |

| Annual income | 0.597 | |||

| <$30,000, n (%) | 174 (62.1) | 84 (60.0) | 90 (64.3) | |

| $30,000–$49,999, n (%) | 55 (19.6) | 29 (20.7) | 26 (18.6) | |

| >$50,000, n (%) | 37 (13.2) | 21 (15.0) | 16 (11.4) | |

| No response, n (%) | 14 (5.0) | 6 (4.3) | 8 (5.7) | |

| Marital status | 0.468 | |||

| Married, n (%) | 162 (57.9) | 80 (57.1) | 82 (58.6) | |

| Living with someone, n (%) | 28 (10.0) | 14 (10.0) | 14 (10.0) | |

| Separated, n (%) | 28 (10.0) | 18 (12.9) | 10 (7.1) | |

| Divorced, n (%) | 36 (12.9) | 17 (12.1) | 19 (13.6) | |

| Widowed, n (%) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | |

| Never married & not living with someone, n (%) | 24 (8.6) | 11 (7.9) | 13 (9.3) |

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of Primary and Secondary Outcomes at Baseline

| Variables | Overall sample (n=280) | Familias Unidas (n=140) | Control (n=140) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or % | Min–max | Mean (SD) or % | Min–max | Mean (SD) or % | Min–max | |

| Primary outcomes | ||||||

| Adolescent | ||||||

| Added sugar intake, teaspoons | 12.65 (12.82) | 0.64–117.60 | 12.33 (13.41) | 1.78–117.60 | 12.90 (13.00) | 0.64–117.60 |

| Fruit/vegetable intake, cups | 2.50 (2.38) | 0.41–14.06 | 2.49 (2.43) | 0.61–14.06 | 2.49 (2.27) | 0.41–14.06 |

| Sweetened beverages, teaspoons | 4.58 (8.69) | 0.00–121.98 | 4.21 (9.14) | 0.00–121.98 | 4.75 (8.49) | 0.00–121.98 |

| Month MVPA,a minutes | 360.00 (690.00) | 10.00–5,600.00 | 360.00 (665.00) | 10.00–5,600.00 | 360.00 (827.50) | 20.00–4,828.00 |

| Parent | ||||||

| Added sugar intake, teaspoons | 11.52 (10.00) | 1.00–115.00 | 11.82 (9.00) | 2.00–84.00 | 11.16 (11.00) | 1.00–115.00 |

| Fruit/vegetable intake, cups | 2.42 (2.00) | 0.00–9.00 | 2.34 (1.00) | 1.00–8.00 | 2.43 (2.00) | 0.00–9.00 |

| Sweetened beverages, teaspoons | 4.79 (9.00) | 0.00–162.00 | 5.23 (8.00) | 0.00–111.00 | 4.38 (9.00) | 0.00–162.00 |

| Month MVPA,a minutes | 390.00 (625.00) | 10.00–6,480.00 | 360.00 (667.50) | 30.00–6,480.00 | 412.50 (586.25) | 10.00–4,650.00 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Adolescent’s BMI (%) | 94.55 (4.15) | 85.77–100.00 | 95.13 (3.75) | 85.77–99.62 | 93.96 (4.43) | 85.18–100.00 |

| Overweight (85th % to <95th %) | 37.9% | 30.9% | 44.9% | |||

| Obese (≥95th %) | 62.1% | 69.1% | 55.1% | |||

| Parent’s BMI | 30.62 (5.67) | 20.38–62.91 | 31.00 (6.11) | 20.38–62.91 | 20.23 (5.20) | 21.13–50.54 |

| Normal (<25) | 12.6% | 12.9% | 12.2% | |||

| Overweight (25–30) | 39.9% | 35.3% | 44.6% | |||

| Obese (≥30) | 47.5% | 51.8% | 43.2% | |||

| Family functioning Parent | ||||||

| Family communication | 7.29 (1.65) | 0.00–9.00 | 7.23 (1.81) | 0.00–9.00 | 7.36 (1.48) | 3.00–9.00 |

| Peer monitoring of peer | 10.57 (4.70) | 0.00–20.00 | 10.96 (4.58) | 0.00–20.00 | 10.19 (4.80) | 0.00–20.00 |

| Parental involvement | 40.28 (6.38) | 15.08–52.00 | 40.69 (6.21) | 22.00–52.00 | 39.87 (6.55) | 15.08–52.00 |

| Positive parenting | 23.71 (4.23) | 12.00–33.00 | 24.05 (4.29) | 12.00–33.00 | 23.37 (4.18) | 13.00–33.00 |

| Adolescent | ||||||

| Family communication | 6.53 (1.68) | 0.00–9.00 | 6.55 (1.68) | 1.00–9.00 | 6.51 (1.68) | 3.00–9.00 |

| Peer monitoring of peer | 9.42 (4.87) | 0.00–20.00 | 9.43 (4.42) | 0.00–19.00 | 9.42 (5.30) | 0.00–20.00 |

| Parental involvement | 37.86 (8.90) | 8.00–54.00 | 38.45 (7.53) | 17.00–53.00 | 37.26 (10.08) | 8.00–54.00 |

| Positive parenting | 20.84 (5.95) | 0.00–32.00 | 21.03 (5.22) | 4.00–32.00 | 20.64 (6.61) | 0.00–32.00 |

Notes: No significant differences in primary outcomes by conditions were found across all outcomes.

Median and IQR are shown.

Summed scores of four drug uses (marijuana, inhalant, cocaine, and other drug uses).

Min, minimum score; max, maximum score; MVPA, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity.

There were no significant differences on adolescent intake of: (1) added sugars, (2) fresh fruits and vegetables, or (3) sweetened beverages between conditions at 6 months post-baseline or over time (from baseline to 24 months post-baseline) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Intervention Effects Across FUHW and Control Condition for Primary and Secondary Outcomes

| Timepoint |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1–T2 | T1–T4 | |||||

| Outcomes | β | 95% CI | p-value | β | 95% CI | p-value |

| Primary outcomes | ||||||

| Adolescent | ||||||

| Added sugars | 0.1 | −0.1, 0.2 | 0.44 | 0.3 | −0.3, 0.9 | 0.38 |

| Fruit and vegetables | 0.05 | −0.1, 0.2 | 0.50 | 0.2 | −0.4, 0.8 | 0.50 |

| Sweetened beverages | 0.1 | −0.1, 0.2 | 0.21 | 0.4 | −0.1, 0.8 | 0.13 |

| Past month MVPA | 0.1 | −0.03, 0.3 | 0.12 | −0.04 | −0.3, 0.2 | 0.76 |

| Parent | ||||||

| Added sugars | −0.1 | −0.2, −0.004 | <0.05 | −0.1 | −0.3, 0.1 | 0.33 |

| Fruit and vegetables | 0.1 | 0.02, 0.2 | <0.05 | −0.1 | −0.6, 0.4 | 0.77 |

| Sweetened beverages | −0.1 | −0.2, −0.02 | <0.05 | −0.2 | −0.4, 0.1 | 0.17 |

| Past month MVPA | 0.04 | −0.1, 0.2 | 0.67 | 0.1 | −0.2, 0.3 | 0.66 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Adolescent | ||||||

| BMI | −0.1 | −0.9, 0.8 | 0.86 | −0.3 | −0.7, 0.1 | 0.15 |

| Family communication | 0.1 | 0.02, 0.2 | <0.05 | — | — | — |

| Peer monitoring | 0.1 | 0.01, 0.2 | <0.05 | — | — | — |

| Parental involvement | 0.2 | 0.1, 0.3 | 0.001 | — | — | — |

| Positive parenting | 0.1 | −0.02, 0.2 | 0.120 | — | — | — |

| Parent | ||||||

| BMI | −0.1 | −0.1, −0.001 | <0.05 | −0.02 | −0.2, 0.1 | 0.84 |

| Family communication | 0.1 | −0.1, 0.2 | 0.24 | — | — | — |

| Peer monitoring | 0.04 | −0.1, 0.1 | 0.39 | — | — | — |

| Parental involvement | 0.1 | −0.04, 0.2 | 0.26 | — | — | — |

| Positive parenting | 0.04 | −0.1, 0.2 | 0.43 | — | — | — |

Notes: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05).

T1, Timepoint 1; T2, Timepoint 2; T4, Timepoint 4; β, standardized coefficient; MVPA, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity.

For parents, there was a significant difference between FUHW and prevention as usual at 6 months post-baseline. Compared with parents in prevention as usual, parents in the FUHW intervention reported reduced intake of added sugars (β= −0.11, 95% CI= −0.22, −0.01, p=0.04, effect size=0.26) and sweetened beverages (β= −0.12, 95% CI= −0.23, −0.02, p= 0.02, effect size=0.28), and increased intake of fresh fruits and vegetables (β=0.12, 95% CI=0.02, 0.23, p=0.02, effect size=0.29). However, these effects were not sustained through the 24-month follow-up (Table 3).

There were no significant differences in adolescents’ past-month moderate-to-vigorous physical activity between FUHW and prevention as usual at 6 months post-baseline or over time (Table 3). Similarly, there were no significant differences in parents’ past-month moderate-to-vigorous activity between FUHW and prevention as usual at 6 months post-baseline and across trajectories (Table 3).

There were no significant differences in adolescents’ BMI between conditions at 6 months post-baseline or over time (Table 3). At 6 months post-baseline, there was a significant reduction in BMI for parents in FUHW compared with parents in prevention as usual (β= −0.05, 95% CI= −0.11, −0.01, p<0.05, effect size=0.31). However, this difference was not sustained over time (Table 3).

At 6 months post-baseline, there were significant improvements on adolescent reported family communication (β=0.13, 95% CI=0.02, 0.24, p=0.02, effect size=0.31), peer monitoring (β=0.12, 95% CI=0.01, 0.23, p=0.03, effect size=0.28), and parental involvement (β=0.16, 95% CI=0.06, 0.26, p<0.001, effect size=0.41) for adolescents in FUHW compared with adolescents in prevention as usual. There were no significant differences between conditions on adolescent-reported positive parenting (Table 3). For parents, there were no significant differences between FUHW and prevention as usual at 6 months post-baseline on family communication, parental involvement, or positive parenting (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Hispanic families are disproportionately affected by overweight and obesity, with Hispanic adolescents having higher prevalence rates of obesity when compared with their non-Hispanic white, Asian, and black counterparts.45 This study evaluated the relative efficacy of FUHW, an adaptation of Familias Unidas, an evidenced-based family intervention compared with prevention as usual. FUHW did not have a significant effect on physical activity, dietary intake, or BMI outcomes for adolescents. However, short-term effects were observed on improving dietary intake and BMI for parents compared with prevention as usual. Additionally, there were significant intervention effects on family functioning outcomes for adolescents. These findings support how family-based interventions can have an effect on multiple outcomes and multiple family members, simultaneously.46

Findings showed that parents participating in FUHW reported lower intake levels of added sugar and sweetened beverages, increased intake of fresh fruits and vegetables, and lower BMI at 6 months post-baseline, compared with the control group; however, the effects were not sustained at 24 months post-baseline. Improvements in parent outcomes are consistent with other healthy lifestyle family-based interventions.47 Further, this study findings suggest that “booster” sessions may be helpful in sustaining the effects of the intervention on long-term physical activity and dietary intake outcomes. Previous studies show that boosters sessions that offer follow-up support can possibly strengthen the habits formed during an intervention.48–50 For example, a study examining the effectiveness of booster sessions on an exercise intervention showed that booster sessions buffered the decline in behaviors and exercise habit strength through a computer-assisted telephone interview. In the future, post-FUHW intervention booster sessions may include content (similar to family sessions) that focuses on problem-solving barriers to maintaining a healthy diet and recommended levels of physical activity. Further, future research should examine whether booster sessions for FUHW may help parents maintain positive intervention effects over time.

There were no effects for adolescents on dietary and physical activity outcomes. It could be possible that the contact adolescents had with the 12-week, 1 session per week, FUHW intervention was inadequate to significantly affect adolescents’ physical activity, dietary intake, and BMI.51,52 Results from a meta-analysis examining the effects of lifestyle interventions (i.e., exercise and dietary behaviors) on overweight and obesity outcomes among children and adolescents indicated that studies with intervention periods lasting longer than 6 months showed greater weight loss than short-term interventions.53 Further, the same meta-analysis indicated that reductions in BMI from a relatively short intervention (i.e., 2 months) included increased session frequencies (i.e., 4 times per week) and dietary restrictions. Aligned with previous research, adolescents may need a more frequent version of the obesity-adapted intervention relative to adults, versus once a week, to implement behaviors learned through the intervention.54 In fact, it should be noted that a significant proportion of adolescent participants were obese when they entered the study and the U.S. Task Force recommends ≥26 hours of intervention contact dedicated to healthy weight management for weight loss interventions to be successful.52 In the future, FUHW may help improve intervention effects for adolescents by including nutritional information (e.g. healthy meal preparation, deciphering food labels, healthier fast food and beverage options) in addition to adolescent physical activity during group session weeks.

Limitations

This study has its limitations. First, study participants are Hispanics from one geographical location (Miami, Florida). Whereas the Hispanic population from this geographical location is heterogeneous (e.g., representing numerous Latin American countries), the generalizability of study findings may still be limited. Second, some measures, including dietary intake and physical activity, were self-reported by adolescents and parents. The use of self-report for study variables may introduce shared method variance, which may contribute to biased significant findings. Further, self-report measures may also contribute to markedly high levels of physical activity at baseline for adolescents. It is possible that self-reported high levels of physical activity at baseline for adolescents made it difficult to detect improvements in physical activity behaviors as a result of the intervention. Future, studies could corroborate adolescent self-reported measures with accelerometer or movement monitor data55 to limit self-reported bias, for example. It is also possible that the design of the control condition could affect physical activity, dietary intake, and BMI outcomes and perhaps made it difficult to detect intervention effects. Third, sexual maturation effects were not accounted for during analyses. Previous research show that sexual maturation, such as breast development, is significantly associated with anthropometric and body composition measures (i.e., waist circumference, BMI, lean mass, fat mass, and body fat percentage); therefore, not accounting for maturation effects may have influenced findings.56 Finally, investigators did not collect information regarding how income could have restricted availability to healthy food options for families. Future research should account for the role of income, as it may have an effect on improved dietary intake.

CONCLUSIONS

The FUHW intervention did not have an effect on any adolescent health behaviors (physical activity and dietary intake) and BMI outcomes. However, FUHW did have positive short-term effects on dietary intake and BMI for parents, yet other intervention strategies (e.g., booster session for families, increased nutritional information for adolescents) may be needed to sustain effects for parents. Finally, it may be that future studies of family interventions for adolescent obesity have to have greater dosage and follow-up for a longer period.15,52

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (grant R01MD007724) to Guillermo Prado, PhD and Sarah Messiah, PhD, MPH and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grant DK116533) to Cynthia Lebron, PhD. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH. The funding agencies played no role in study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit for publication. The authors declare no conflict of interest or financial disclosures.

This study is dedicated to Jorge Prado (April 18, 1938–October 14, 2013) and Mercedes Prado (June 25, 1941–February 9, 2015) who inspired the commitment and dedication to improving lifelong health for all Hispanics.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Hales CM, Carroll MD, Aoki Y, Freedman DS. Differences in obesity prevalence by demographics and urbanization in U.S. children and adolescents, 2013–2016. JAMA. 2018;319(23):2410–2418. 10.1001/jama.2018.5158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skinner AC, Ravanbakht SN, Skelton JA, Perrin EM, Armstrong SC. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity in U.S. children, 1999–2016. Pediatrics. 2018;141(3):e20173459 10.1542/peds.2018-1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson TA, Adolph AL, Butte NF. Nutrient adequacy and diet quality in non-overweight and overweight Hispanic children of low socioeconomic status: the Viva la Familia Study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(6):1012–1021. 10.1016/j.jada.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance – United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67(8):1–114. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Branscum P, Sharma M. A systematic analysis of childhood obesity prevention interventions targeting Hispanic children: lessons learned from the previous decade. Obes Rev. 2011;12(5):e151–e158. 10.1111/j.1467-789x.2010.00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tovar A, Renzaho AM, Guerrero AD, Mena N, Ayala GX. A systematic review of obesity prevention intervention studies among immigrant populations in the U.S. Curr Obes Rep. 2014;3(2):206–222. 10.1007/s13679-014-0101-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, et al. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1641–1652. 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cordova D, Heinze J, Mistry R, et al. Family functioning and parent support trajectories and substance use and misuse among minority urban adolescents: a latent class growth analysis. Subst Use Misuse. 2014;49(14):1908–1919. 10.3109/10826084.2014.935792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prado G, Pantin H, Briones E, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a parent-centered intervention in preventing substance use and HIV risk behaviors in Hispanic adolescents. J Consult Clin Psych. 2007;75(6):914–926. 10.1037/0022-006x.75.6.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berge JM, Wall M, Larson N, Loth KA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Family functioning: associations with weight status, eating behaviors, and physical activity in adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(3):351–357. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haines J, Rifas-Shiman SL, Horton NJ, et al. Family functioning and quality of parent-adolescent relationship: cross-sectional associations with adolescent weight-related behaviors and weight status. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13(1):68 10.1186/s12966-016-0393-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warnick JL, Stromberg SE, Krietsch KM, Janicke DM. Family functioning mediates the relationship between child behavior problems and parent feeding practices in youth with overweight or obesity. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9(3):431–439. 10.1093/tbm/ibz050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loprinzi PD, Trost SG. Parental influences on physical activity behavior in preschool children. Prev Med. 2010;50(3):129–133. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sleddens SF, Gerards SM, Thijs C, De Vries NK, Kremers SP. General parenting, childhood overweight and obesity-inducing behaviors: a review. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6(Suppl 3):e12–e27. 10.3109/17477166.2011.566339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith JD, Montaño Z, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Wilson MN. Preventing weight gain and obesity: indirect effects of the family check-up in early childhood. Prev Sci. 2015;16(3):408–419. 10.1007/s11121-014-0505-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bronfenbrenner U The Ecology of Human Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bronfenbrenner U Ecology of the family as a context for human development: research perspectives. Dev Psychol. 1986;22(6):723–742. 10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ash T, Agaronov A, Young T, Aftosmes-Tobio A, Davison KK. Family-based childhood obesity prevention interventions: a systematic review and quantitative content analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):113 10.1186/s12966-017-0571-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prado G, Cordova D, Huang S, et al. The efficacy of Familias Unidas on drug and alcohol outcomes for Hispanic delinquent youth: main effects and interaction effects by parental stress and social support. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125(Suppl 1):S18–S25. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prado G, Pantin H, Huang S, et al. Effects of a family intervention in reducing HIV risk behaviors among high-risk Hispanic adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediat Adol Med. 2012;166(2):127–133. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prado G, Pantin H. Reducing substance use and HIV health disparities among Hispanic youth in the USA: the Familias Unidas program of research. Interv Psicosoc. 2011;20(1):63–73. 10.5093/in2011v20n1a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szapocznik J, Coatsworth JD. Drug Abuse: Origins & Interventions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999:331–366. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saltzman JA, Fiese BH, Bost KK, McBride BA. Development of appetite self-regulation: integrating perspectives from attachment and family systems theory. Child Dev Perspect. 2018;12(1):51–57. 10.1111/cdep.12254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowen M Family Therapy in Clinical Practice. Lanham, MD: Jason Aronson; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lebron CN, Lee TK, Park SE, St George SM, Messiah SE, Prado G. Effects of parent-adolescent reported family functioning discrepancy on physical activity and diet among Hispanic youth. J Fam Psychol. 2018;32(3):333–342. 10.1037/fam0000386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vidot DC, Huang S, Poma S, Estrada Y, Lee TK, Prado G. Familias Unidas’ crossover effects on suicidal behaviors among Hispanic adolescents: results from an effectiveness trial. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2016;46(Suppl 1):S8–S14. 10.1111/sltb.12253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perrino T, Pantin H, Prado G, et al. Preventing internalizing symptoms among Hispanic adolescents: a synthesis across Familias Unidas trials. Prev Sci. 2014;15(6):917–928. 10.1007/s11121-013-0448-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.St. George SM, Messiah SE, Sardinas KM, et al. Familias Unidas for health & wellness: adapting an evidence-based substance use and sexual risk behavior intervention for obesity prevention in Hispanic adolescents. J Prim Prev. 2018;39(6):529–553. 10.1007/s10935-018-0524-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei L, Lachin JM. Properties of the urn randomization in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1988;9(4):345–364. 10.1016/0197-2456(88)90048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sallis JF, McKenzie TL, Alcaraz JE, Kolody B, Faucette N, Hovell MF. The effects of a 2-year physical education program (SPARK) on physical activity and fitness in elementary school students. Sports, Play and Active Recreation for Kids. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(8):1328–1334. 10.2105/ajph.87.8.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.St George SM, Petrova M, Kyoung Lee T, et al. Predictors of participant attendance patterns in a family-based Intervention for overweight and obese Hispanic adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(7):1482 10.3390/ijerph15071482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson FE, Midthune D, Kahle L, Dodd KW. Development and evaluation of the National Cancer Institute’s dietary screener questionnaire scoring algorithms. J Nutr. 2017;147(6):1226–1233. 10.3945/jn.116.246058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.George D, Mallery M. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 17.0 Update. 10th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armstrong S, Wong CA, Perrin E, Page S, Sibley L, Skinner A. Association of physical activity with income, race/ethnicity, and sex among adolescents and young adults in the United States: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007–2016. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(8):732–740. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu F, Cohen S, Greaney M, Greene G. The association between U.S. adolescents’ weight status, weight perception, weight satisfaction, and their physical activity and dietary behaviors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(9):1931 10.3390/ijerph15091931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, et al. 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat 11. 2002;246:1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Zelli A, Huesman LR. The relation of family functioning to violence among inner-city minority youths. J Fam Psychol. 1996;10(2):115–129. 10.1037/0893-3200.10.2.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Huesmann LR, Zelli A. Assessment of family relationship characteristics: a measure to explain risk for antisocial behavior and depression among urban youth. Psychol Assess. 1997;9(3):212–223. 10.1037/1040-3590.9.3.212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang A-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41(4):1149–1160. 10.3758/brm.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. How to use a Monte Carlo study to decide on sample size and determine power. Struct Equ Modeling. 2002;9(4):599–620. 10.1207/s15328007sem0904_8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morrill MI, Hawrilenko M, Córdova JV. A longitudinal examination of positive parenting following an acceptance-based couple intervention. J Fam Psychol. 2016;30(1):104–113. 10.1037/fam0000162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meredith W, Tisak J. Latent curve analysis. Psychometrika. 1990;55(1):107–122. 10.1007/bf02294746. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spittal MJ, Pirkis J, Gurrin LC. Meta-analysis of incidence rate data in the presence of zero events. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15(42):1–16. 10.1186/s12874-015-0031-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Enders CK. Analyzing longitudinal data with missing values. Rehabil Psychol. 2011;56(4):267–288. 10.1037/a0025579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;288:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huidobro D, Mendenhall T. Family oriented care: opportunities for health promotion and disease prevention. J Fam Med Dis Prev. 2015;1(2):1–6. 10.23937/2469-5793/1510009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.St George SM, Wilson DK, Van Horn ML. Project SHINE: effects of a randomized family-based health promotion program on the physical activity of African American parents. J Behav Med. 2018;41(4):537–549. 10.1007/s10865-018-9926-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fleig L, Pomp S, Schwarzer R, Lippke S. Promoting exercise maintenance: how interventions with booster sessions improve long-term rehabilitation outcomes. Rehab Psychol. 2013;58(4):323–333. 10.1037/a0033885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stark LJ, Clifford LM, Towner EK, et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial of a behavioral family-based intervention with and without home visits to decrease obesity in preschoolers. J Pediatr Psychol. 2014;39(9):1001–1012. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsu059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vos RC, Wit JM, Pijl H, Houdijk EC. Long-term effect of lifestyle intervention on adiposity, metabolic parameters, inflammation and physical fitness in obese children: a randomized controlled trial. Nutr Diabetes. 2011;1:e9 10.1038/nutd.2011.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Janicke DM, Steele RG, Gayes LA, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of comprehensive behavioral family lifestyle interventions addressing pediatric obesity. J Pediatr Psychol. 2014;39(8):809–825. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsu023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Connor EA, Evans CV, Burda BU, Walsh ES, Eder M, Lozano P. Screening for obesity and intervention for weight management in children and adolescents: evidence report and systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2017;317(23):2427–2444. 10.1001/jama.2017.0332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ho M, Garnett SP, Baur L, et al. Effectiveness of lifestyle interventions in child obesity: systematic review with meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):e1647–e1671. 10.1542/peds.2012-1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cliff DP, Okely AD, Morgan PJ, et al. Movement skills and physical activity in obese children: randomized controlled trial. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(1):90–100. 10.1249/mss.0b013e3181e741e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rääsk T, Mäestu J, Lätt E, et al. Comparison of IPAQ-SF and two other physical activity questionnaires with accelerometer in adolescent boys. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169527 10.1371/journal.pone.0169527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Himes JH, Obarzanek E, Baranowski T, Wilson DM, Rochon J, McClanahan BS. Early sexual maturation, body composition, and obesity in African‐American girls. Obes Res. 2004;12(S9):64S–72S. 10.1038/oby.2004.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.