Abstract

Background: Art therapy (AT) is frequently offered to children and adolescents with psychosocial problems. AT is an experiential form of treatment in which the use of art materials, the process of creation in the presence and guidance of an art therapist, and the resulting artwork are assumed to contribute to the reduction of psychosocial problems. Although previous research reports positive effects, there is a lack of knowledge on which (combination of) art therapeutic components contribute to the reduction of psychosocial problems in children and adolescents.

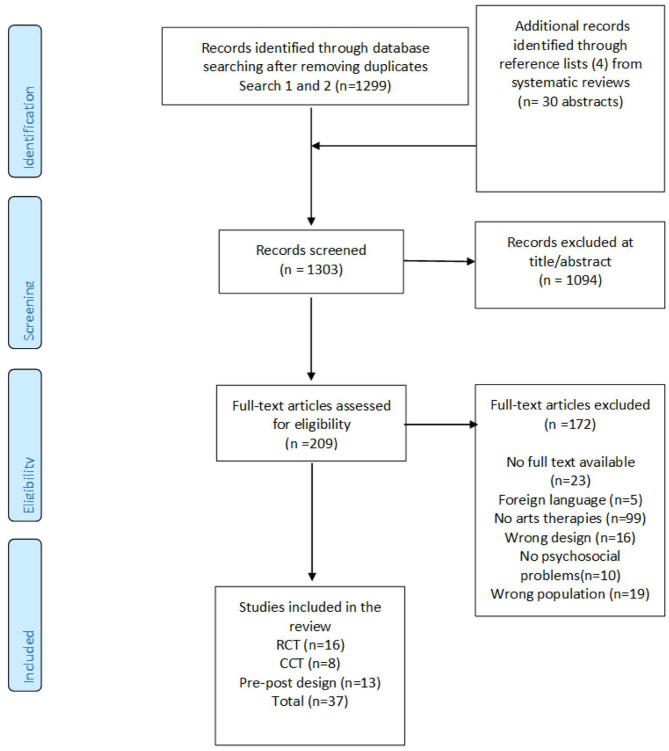

Method: A systematic narrative review was conducted to give an overview of AT interventions for children and adolescents with psychosocial problems. Fourteen databases and four electronic journals up to January 2020 were systematically searched. The applied means and forms of expression, therapist behavior, supposed mechanisms of change, and effects were extracted and coded.

Results: Thirty-seven studies out of 1,299 studies met the inclusion criteria. This concerned 16 randomized controlled trials, eight controlled trials, and 13 single-group pre–post design studies. AT interventions for children and adolescents are characterized by a variety of materials/techniques, forms of structure such as giving topics or assignments, and the use of language. Three forms of therapist behavior were seen: non-directive, directive, and eclectic. All three forms of therapist behavior, in combination with a variety of means and forms of expression, showed significant effects on psychosocial problems.

Conclusions: The results showed that the use of means and forms of expression and therapist behavior is applied flexibly. This suggests the responsiveness of AT, in which means and forms of expression and therapist behavior are applied to respond to the client's needs and circumstances, thereby giving positive results for psychosocial outcomes. For future studies, presenting detailed information on the potential beneficial effects of used therapeutic perspectives, means, art techniques, and therapist behavior is recommended to get a better insight into (un)successful art therapeutic elements.

Keywords: art therapy, psychosocial problems, children, adolescents, systematic narrative review

Introduction

Psychosocial problems are highly prevalent among children and adolescents with an estimated prevalence of 10%−20% worldwide (Kieling et al., 2011; World Health Organization, 2018). These problems can severely interfere with everyday functioning (Bhosale et al., 2015; Veldman et al., 2015) and increase the risk of poorer performance at school (Veldman et al., 2015). The term psychosocial problems is used to emphasize the close connection between psychological aspects of the human experience and the wider social experience (Soliman et al., 2020) and cover a wide range of problems, namely, emotional, behavioral, and social. Emotional problems are often referred to as internalizing problems, such as anxiety, depressive feelings, withdrawn behavior, and psychosomatic complaints. Behavioral problems are often considered as externalizing problems, such as hyperactivity, aggressive behavior, and conduct problems. Social problems are problems related to the ability of the child to initiate and maintain social contacts and interactions with others. Often, emotional, behavioral, and social problems occur jointly (Vogels, 2008; Jaspers et al., 2012; Ogundele, 2018). The etiology of psychosocial problems is complex and varies with regard to the problem(s) and/or the specific individual. A number of theories seek to explain the etiology of psychosocial problems. The most common theory in Western psychology and psychiatry is the biopsychosocial theory, which assumes that a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental stressors triggers the onset of psychosocial problems (Lehman et al., 2017). But also, attachment theories get renewed attention (Duschinsky et al., 2015). These theories focus on the role of the early caregiver–child relationships and assume that (a lack of) security of attachment affects the child's self-(emotion)regulatory capacity and therefore his or her emotional, behavioral, and social competence (Veríssimo et al., 2014; Brumariu, 2015; Groh et al., 2016). Research has identified a number of biological, psychological, and environmental factors that contribute to the development or progression of psychosocial problems (Arango et al., 2018), namely, trauma, adverse childhood experiences, genetic predisposition, and temperament (Boursnell, 2011; Sellers et al., 2013; Wright and Simms, 2015; Patrick et al., 2019).

Psychosocial problems in children and adolescents are a considerable expense to society and an important reason for using health care. But, most of all, psychosocial problems can have a major impact on the future of the child's life (Smith and Smith, 2010). Effective interventions for children and adolescents, aiming at psychosocial problems, could prevent or reduce the likelihood of long-term impairment and, therefore, the burden of mental health disorders on individuals and their families and the costs to health systems and communities (Cho and Shin, 2013).

The most common treatments of psychosocial problems in children and adolescents include combinations of child- and family-focused psychological strategies, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and social communication enhancement techniques and parenting skills training (Ogundele, 2018). These interventions are designed with the idea that cognitions affect the way that children and adolescents feel and behave (Fenn and Byrne, 2013). However, this starting point is considered not suitable for all youngsters, in particular, for children and adolescents who may find it difficult to formulate or express their experiences and feelings (Scheeringa et al., 2007; Teel, 2007). For such situations in clinical practice, additional therapies are often offered. Art therapy (AT) is such a form of therapy.

AT is an experiential form of treatment and has a special position in the treatment of children and adolescents because it is an easily accessible and non-threatening form of treatment. Traditionally, AT is (among others) used to improve self-esteem and self-awareness, cultivate emotional resilience, enhance social skills, and reduce distress (American Art Therapy Association, 2017), and research has increasingly identified factors, such as emotion regulation (Gratz et al., 2012) and self-esteem (Baumeister et al., 2003) as mechanisms underlying multiple forms of psychosocial problems.

Art therapists work from different orientations and theories, such as psychodynamic; humanistic (phenomenological, gestalt, person-centered); psychoeducational (behavioral, cognitive–behavioral, developmental); systemic (family and group therapy); as well as integrative and eclectic approaches. But also, there are various variations in individual preference and orientation by art therapists (Van Lith, 2016). In AT, the art therapist may facilitate positive change in psychosocial problems through both engagement with the therapist and art materials in a playful and safe environment. Fundamental principles in AT for children and adolescents are that visual image-making is an important aspect of the natural learning process and that the children and adolescents, in the presence of the art therapist, can get in touch with feelings that otherwise cannot easily be expressed in words (Waller, 2006). The ability to express themselves and practice skills can give a sense of control and self-efficacy and promotes self-discovery. It, therefore, may provide a way for children and clinicians to address psychosocial problems in another way than other types of therapy (Dye, 2018).

Substantial clinical research concerning the mechanisms of change in AT is lacking (Gerge et al., 2019), although it is an emerging field (Carolan and Backos, 2017). AT supposed mechanisms of change can be divided into working mechanisms specific for AT and overall psychotherapeutic mechanisms of change, such as the therapeutic relationship between client and therapist or the expectations or hope (Cuijpers et al., 2019). Specific mechanisms of change for AT include, for instance, the assumption that art can be an effective system for the communication of implicit information (Gerge, and Pedersen, 2017) or that art-making consists of creation, observation, reflecting, and meaning-making, which leads to change and insight (Malchiodi, 2007).

Recently, it has been shown that AT results in beneficial outcomes for children and adolescents. Cohen-Yatziv and Regev (2019) published a review on AT for children and adolescents and found positive effects in children with trauma or medical conditions, in juvenile offenders, and in children in special education and with disabilities. While increasing insight into the effects of AT for different problem areas among children is collected, it remains unclear whether specific elements of AT interventions and mechanisms of change may be responsible for these effects. In clinical practice, art therapists base their therapy on rich experiential and intuitive knowledge. This knowledge is often implicit and difficult to verbalize, also known as tacit knowledge (Petri et al., 2020). Often, it is based on beliefs or common sense approaches, without a sound basis in empirical results (Haeyen et al., 2017). This intuitive knowledge and beliefs consist of (theoretical) principles, art therapeutic means and forms of expression, and therapist behavior [including interactions with the client(s) and handling of materials] that art therapists judge necessary to produce desired outcomes (Schweizer et al., 2014). Identifying the elements that support positive outcomes improves the interpretation and understanding of outcomes, provides clues which elements to use in clinical practice, and will give a sound base for initiating more empirical research on AT (Fixsen et al., 2005). The aim of this review is to provide an overview of the specific elements of art therapeutic interventions that were shown to be effective in reducing psychosocial problems in children and adolescents. In this review, we will focus on applied means and forms, therapist behavior, supposed mechanisms of change of art therapeutic interventions. As the research question was stated, i.e., which art therapeutic elements support positive outcomes in psychosocial problems of children and adolescents (4–20)?

Methods

Study Design

A systematic narrative review is performed according to the guidelines of the Cochrane Collaboration for study identification, selection, data extraction, and quality appraisal. Data analysis was performed, conforming narrative syntheses.

Eligibility Criteria

In this review, we included peer-reviewed published randomized controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomized clinical controlled trials (CCTs), and studies with group pre–posttest designs for AT of psychosocial problems in children and adolescents (4–20 years). Studies were included regardless of whether AT was present within the experimental or control condition. Qualitative data were included when data analysis methods specific for this kind of data were used. Only publications in English, Dutch, or German were included. Furthermore, only studies in which AT was provided by a certified art therapist to individuals or groups, without limitations on duration and number of sessions, were inserted. Excluded were studies in which AT was structurally combined with another non-verbal therapy, for instance, music therapy. Studies on (sand)play therapy were also excluded. Concerning the outcome, studies needed to evaluate AT interventions on psychosocial problems. Psychosocial problems were broadly defined as emotional, behavioral, and social problems. Considered emotional (internalizing) problems were, for instance, anxiety, withdrawal, depressive feelings, psychosomatic complaints, and posttraumatic stress problems/disorder. Externalizing problems were, for instance, aggressiveness, restlessness, delinquency, and attention/hyperactivity problems. Social problems were problems that the child has in making and maintaining contact with others. Also included were studies that evaluated AT interventions targeted at children/adolescents with psychosocial problems and showed results on supposed underlying mechanisms such as, for instance, self-esteem and emotion regulation.

Searches

Fourteen databases and four electronic journals were searched: PUBMED, Embase (Ovid), PsycINFO (EBSCO), The Cochrane Library (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials), Web of Science, Cinahl, Embase, Eric, Academic Search Premier, Google Scholar, Merkurstab, ArtheData, Relief, and Tijdschrift Voor Vaktherapie (Journal of Arts Therapies in the Netherlands). A search strategy was developed using keywords (art therapy in combination with a variety of terms regarding psychosocial problems) for the electronic databases according to their specific subject headings or structure. For each database, search terms were adapted according to the search capabilities of that database (Appendix 1). The search period had no limitation until the actual first search date: October 5, 2018. The search was repeated on January 30, 2020. If online versions of articles could not be traced, the authors were contacted with a request to send the article to the first author. The reference lists of systematic reviews, found in the search, were hand searched for supplementing titles to ensure that all possible eligible studies would be detected.

Study Selection

A single RefWorks file of all identified references was produced. Duplicates were removed. The following selection procedure was independent of each other carried out by four researchers (LB, SvH, MS, and KP). Titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility by three researchers (LB, SvH, and KP). The full texts were subsequently assessed by three researchers (LB, MS, and KP) according to the eligibility criteria. Any disagreement in study selection between a pair of reviewers was resolved through discussion or by consultation of the fourth reviewer (SvH).

Quality of the Studies

The quality of the studies was assessed by two researchers (LB and KP) applying the EPHPP “Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies” (Thomas et al., 2004). Independent of each other, they came to an opinion, after which consultation took place to reach an agreement. To assess the quality, the Quality Assessment Tool was used, which has eight categories: selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, withdrawal and dropouts, intervention integrity, and analysis. Once the assessment was completed, each examined study received a mark ranging between “strong,” “moderate,” and “weak.” The EPHPP tool has a solid methodological rating (Thomas et al., 2004).

Data Collection and Analysis

The following data were collected from the included studies: continent/country, type of publication of study, year of publication, language, impact factor of the journal published, study design, the primary outcome, measures, setting, type of clients, comorbidity, physical problems, total N, experimental N, control N, proportion male, mean age, age range, the content of the intervention, content control, co-intervention, theoretical framework AT, other theoretical frameworks, number of sessions, frequency sessions, length sessions, outcome domains and outcome measures, time points, outcomes, and statistics. An inductive content analysis (Erlingsson and Brysiewicz, 2017) was conducted on the characteristics of the employed ATs concerning the means and forms of expression, the associated therapist behavior, the described mechanisms of change, and whether there were significant effects of the AT interventions. A narrative analysis was performed.

Results

Study Selection

The first search (October 2018) yielded 1,285 unique studies. In January 2020, the search was repeated, resulting in 14 additional unique studies, making a total of 1,299. Four additional studies identified from manually searching the reference lists from 30 reviews were added, making a total of 1,303 studies screened on title and abstract. In the first search, 1,085 studies, and in the second search, nine studies were excluded, making a total of 1,094 studies being excluded on title and abstract. This resulted in 209 full-text articles to assess eligibility. In the full-text selection phase, from the first search, another 167 studies were excluded; in the second search, five studies were excluded. This makes a total of 172 studies being excluded in the full-text phase. Twenty-three studies were excluded because a full text was unavailable; five studies because the language was not English, Dutch, or German; 99 studies did not meet the AT definition; 16 studies had a wrong design; 10 studies did not treat psychosocial problems; and 19 studies concerned a wrong population. In total, 37 studies were included (see Figure 1 for an overview of the complete selection process).

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow chart.

Study Design

The final review included 16 RCTs, eight CCTs, and 13 single-group pre–post designs (total n = 37). Of the RCTs, a mixed-method design, involving both quantitative and qualitative data, was used in two studies. In one RCT, the control group received AT meeting our criteria, while the experimental group did not receive such a therapy (11). In another RCT, the experimental and the control group both received AT meeting our criteria (13). Also, two CCT studies used a mixed-method design, but these qualitative results were not included due to inappropriate analysis. Of the single-group pre–posttest designs, two studies had a mixed-method (quantitative and qualitative) design (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study characteristics/outcome.

| References | Design/Time points | Quality assess-ment rate | Study population | Number of participants (treated/control) | Type (group or individual or both), frequency, duration | Control intervention/sare as usual | Outcome domain/Measure | Results | Qualitative results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bazargan and Pakdaman (2016) | RCT, pre–posttest | Strong | Age: 14–18 with internalizing and externalizing problems | 60 (30/30) | Group, six sessions, 60 min | Not described | Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA) (2001): internalizing and externalizing problems | Art therapy significantly reduced internalizing problems; effect in reducing externalizing problems was not significant. | - |

| Beebe et al. (2010) | RCT, pre–posttest, follow-up: 6 months | Weak | Age: 7–14 with persistent asthma | 22 (11/11) | Group, seven sessions, 60 min, once a week | Care as usual | Beck Youth Inventories Second Edition: self-reported adaptive and maladaptive behaviors and emotions; the Pediatric Quality of Life (Peds QL) Asthma Module and the Peds QL Asthma Module Parent Report for Children: impact of asthma on the quality of life; Draw a Person Picking an Apple from a Tree: evaluation part from the Formal Elements of Art Therapy Scale (FEATS): coping abilities and resourcefulness | Statistically improved Beck anxiety and self-concept scores from the child-reported Beck Inventories. Disruptive behavior, anger, and depression did not change statistically. Improved problem-solving and affect drawing scores on the FEATS. Statistically improved parent and child worry, communication, and parent and child total quality of life scores. At 6 months, the active group maintained (affect drawing scores, worry, and quality of life); Bec[6mm]k Anxiety score Frequency of asthma exacerbations did not differ between the two groups. | - |

| Beh-Pajooh et al. (2018) | RCT, pre–posttest | Moderate | Mean age:12, male children with ID and externalizing behaviors | 60 (30/30) | Group, 12 sessions two times a week, 45 min | The control group did not receive any intervention program | Conditional Reasoning Problems: externalizing behaviors; Bender Visual-Motor Gestalt Test (BVMGT): emotional problems | The mean levels of externalizing behaviors between the intervention group and the control group were significantly different. No significance for emotional problems. | - |

| Chapman et al. (2001) | RCT, measures at 1-week, 1-month, and 6-months intervals | Moderate | Age: 7–17, mean age: 10.7, 70.6% male admitted to a Level I trauma center for traumatic injuries | 58 (31/27) | Individual, once | Care as usual, including child life services, art therapy, social work and psychiatric consults | PTSD-I: self-report measure that asks the individuals to respond to a 20-item inventory of symptoms based primarily on the diagnostic PTSD criteria in the DSM-IV | No statistically significant differences in the reduction of PTSD symptoms between the experimental and control groups. Children receiving the art therapy intervention showed a reduction in acute stress symptoms but not significantly. | - |

| Freilich and Shechtman (2010) | RCT, baseline, after, follow-up (3 months later) Process measures five times throughout the intervention Critical incidents: following each session | Moderate | Age: 7–15, learning disabilities, 70 % male | 93 (42/51) | Group, 22 weeks, 60 min | Three hours of teaching | Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)/The Teacher Evaluation Form (TRF): adjustment; Working Alliance Inventory: bonding with group members | Significant reduction in internalizing and externalizing problems. Control group scored higher on process variables (bonding and impression of therapy); bonding was associated with outcomes only in the therapy condition (not significant). | - |

| Hashemian and Jarahi (2014) | RCT, pre–posttest | Moderate | Age: 8–15, educable ID students, IQ 50 to 70, boys and girls | 20 (10/10) | Group, 12 sessions, 75 min 2 times a week within 2 months | Care as usual: routine education and activity of their programs in school | Rutter Behavior Questions (form for teachers): aggression, hyperactivity, social conflict, antisocial behaviors, attention deficits; Good enough draw a person test: aggression behavior | Painting therapy was effective. The mean scores of aggression in the intervention group and the control group were significantly different. | - |

| Kymissis et al. (1996) | RCT, pre–posttest | Moderate | Age: 13–17, variety of diagnoses: Conduct Disorder (CD), Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), Depressive Disorder, Bipolar Disorder and Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) | 37 (18/19) | Group, eight sessions, four sessions per week for 2 weeks | Discussion group with same co-therapists as treatment group: free discussion with minimal directions | Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS): general functioning; Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP): distress from interpersonal sources | Both groups significant improvement in general functioning, SCIT members the highest degree (however not significant). No significance in either group on interpersonal variables of Assertiveness, Sociability, or Responsibility. | - |

| Liu (2017) | RCT, pre–posttest | Strong | Age: 6–13, one or more traumatic experiences and self-reported or parent-reported sleep-related problems | 41 (21/20) | Group, eight sessions of 50 min in 2 weeks | Care as usual: counseling/ medications and same group activities except the experimental SF-AT treatment, regular group activities: art, music, sports, computer games and dance | The Connecticut Trauma Screen (CTS) and Child Reaction to Traumatic Events Scale-Revised (CRTES): PTSD; Sleep Self-Report (SSR): sleep (trauma-related) | Findings indicated that the SF-AT significantly alleviated PTSD and sleep symptoms. | - |

| Lyshak-Stelzer et al. (2007) | RCT, pre–posttest | Weak | Age: 13–17, 55,2% male, chronic child post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | 29 (14/15) | Individual approach in group, 16 sessions once a week | Care as usual: standard arts- and craft-making activity group | The UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-IV Child Version: PTSD symptoms in children ages 7–12 | Significant treatment-by-condition interaction indicating the TF-ART condition had a greater reduction in PTSD symptoms. | - |

| Ramin et al. (2014) | RCT, pre–posttest | Moderate | Age: 7–11, intense aggressive behaviors, boys and girls | 30 (15/15) | Group, 10-week intervention, participants had the choice of attending weekly 2-h art therapy sessions, a minimum of 7 sessions were included in the study | Not described | Children's Inventory of anger (ChIA): anger; Coppersmith Self-esteem Inventory: self-esteem | The art therapy group showed a significant reduction of anger and significant improvement of self-esteem compared with the control group. The educational self-esteem subscale did not show a significant reduction in comparison with the control group. | - |

| Regev and Guttmann (2005) | RCT, pre–posttest, four groups: 1 experimental, three control | Moderate | Age: 8–13, Male: 63.2%, primary-school children with learning disorders | 104 (25/25/29/25) | Group, 25 weeks, 45 min | Three control groups: control group A (games group) various in-class games, control group B (art therapy group) art projects in an art-therapy fashion by art therapist, group C: no intervention | LSDQ The Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Questionnaire: socially lonely and dissatisfaction; CSCS The Piers-Harris Children's Self-Concept Scale: self-esteem; IARQ The Intellectual Achievement Responsibility Questionnaire: responsibility for successes/failures at school; CS The Children's Sense of Coherence Scale: a sense of empowerment | Children in the art therapy group did not score better than those in any other group on any of the dependent variables. | - |

| Richard et al. (2015) | RCT, pre–posttest | Moderate | Age: 8–14, ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder) | 19 (10/9) | Individual, once 60 min | Magneatos, a three-dimensional construction set for building three-dimensional designs | The Diagnostic Analysis of Non-verbal Accuracy 2-Child Facial Expressions (DANVA 2-CF): measuring the accurate sending and receiving of non-verbal social information | No significant difference between the treatment and control group on the accurate sending and receiving of non-verbal social information; however, the treatment group had more considerable improvement than the control. | - |

| Rosal (1993) | RCT, pre–posttest, mixed-method | Moderate | Mean age: 10.2, moderate to severe behavior problems | 36 (12/12/12) | Group, 20 times, two times a week, 50 min | Cognitive-behavioral art therapy | The TRS: problem behavior; The Children's Nowicki-Strickland Internal-External Locus of Control (CNS-IE): locus of control; a personal construct drawing interview (PCDI) (qualitative); two case examples are described | No significant results for LOC. Both cognitive-behavioral art therapy and the art as therapy group showed significant results for problem behavior, although art as therapy marginal. | Two children improved in LOC and behavior (case examples) |

| Schreier et al. (2005) | RCT, pre–posttest within 24 h of hospital admission, repeated at 1 month, 6 months, and 18 months | Moderate | Mean age: 10, children hospitalized for a minimum of 24 h after physical trauma | 57 (27/30) | Individual, once for approximately an hour | Care as usual: standard hospital services | UCLA Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index (UCLA PTSD-RI): PTSD | The art therapy intervention showed no sustained effects on the reduction of PTSD symptoms. | |

| Siegel et al. (2016) | RCT, pre–posttest, mixed-method | Moderate | Age: 4–16, mean age: 8.3, pediatric patients with a wide range of serious medical diagnoses | 25 (13/12) | Individual, once 90 min | Control group: the same assessments as the treatment group but did not receive therapy until after all of the assessments were collected | Question asked: how are you feeling right now about your stay in the hospital? Children could choose a series of faces expressing emotions (mood) Complemented at posttest with: a qualitative interview with two questions: Is there anything you want to tell us about how are you feeling right now? | No significant improvements in mood for children following therapy sessions. Compared to the children in the wait-list control group, there was a trend of improvement in mood reported by the children immediately following the therapy. | - |

| Tibbetts and Stone (1990) | RCT, pre–posttest | Strong | Mean age: 14.6, seriously emotionally disturbed (SED) | 16 (8/8) | Group, once a week, 6 weeks, 45 min | Weekly socialization sessions by the same professional with individual sessions lasting 45 min, activities: playing board games, talking about weekend activities, taking walks on the school grounds | The Burks Behavior Rating Scales (BBRS): behavioral and emotional functioning; the Roberts Apperception Test (RATC): personality | Overall, no significant differences were found on the BBRS, but both groups demonstrated overall positive changes across almost all measured categories of behavioral and emotional functioning. The experimental group demonstrated statistically significant improvement in attention span and sense of identity (BBRS). RATC: significant improvement overall. The experimental group demonstrated significant score reductions in Reliance Upon Others, degree of perceived support available from others in the environment (Support/Other), and their positive expressed feelings about themselves (Support/Child). At the same time, significant reductions were also found in levels of Depression, Rejection, and Anxiety. | - |

| Jang and Choi (2012) | CCT, pre–posttest, follow-up after 3 months | Weak | Age: 13–15, boys and girls in an educational welfare program needing emotional and psychological help | 16 (8/8) | Group, 18 times, weekly 80 min | Not described | Shin's (2004) ego resilience scale: ego resilience | A significant increase in ego resilience between pre-, post-, and follow-up. There was a positive effect on the regulation and release of emotions (not significant). | - |

| Khadar et al. (2013) | CCT, pre–posttest, 1 month follow-up | Weak | Age: 7–11, boys with symptoms of separation anxiety disorder | 30 (15/15) | Group, 12 times twice a week, 40 min | Not described | The Child Symptom Inventory-4 (CSI-4): emotional and behavioral disorders | The experimental group had a significant decrease in the symptoms of Separation Anxiety Disorder, while the control group showed no significant difference. | - |

| Khodabakhshi Koolaee et al. (2016) | CCT, pre–posttest, follow-up after 1 month | Weak | Age: 8–12, boys and girls with leukemia cancer who had one score above the mean scores of anxiety and anger | 30 (15/15) | Group, 11 sessions, twice a week, 60 min | The control group did not receive any intervention | Spence Children's Anxiety Scale: anxiety; Children's Inventory of Anger (ChIA): anger | A significant difference between the pretest and post-test scores in aggression and anxiety. | - |

| Pretorius and Pfeifer (2010) | CCT, pre–posttest control group design and posttest only control group design | Weak | Age: 8–11, girls with a history of sexual abuse | 25 (6/6/6/7) | Group, eight times | The control group did not receive any intervention | The Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children (TSCC): depression, anxiety, and sexual trauma; The Human Figure Drawing (HFD): self-esteem | The experimental groups improved significantly compared to the control groups concerning anxiety and depression. No significance in sexual trauma and low self-esteem. | - |

| Ramirez (2013) | CCT, pre–posttest, mixed-method | Weak | Male high school freshmen students living in poverty | 156 Exp.: 80 (29/26/25) Contr.: 76 (24/26/26) |

Group, 12 sessions once a week | Academic work | The Behavior Assessment System for Children Second Edition (BASC-2): behavioral and emotional problems; qualitative questionnaire for responses to open-ended prompts | Three groups: (1) Honors track: art therapy group improved significantly on inattention/hyperactivity more than those in the control group, but not on anxiety, depression, self-esteem, internalizing problems, emotional symptoms, and personal adjustment; (2) Average track: personal adjustment and self-esteem improved significantly more for art therapy participants than for those in the control group, but not on anxiety, depression, inattention/hyperactivity problems, internalizing problems and emotional symptoms. No statistically significant differences were found for participants in the (3) At-risk track. | Participant responses: through the creative process, peer interactions increased, ventilation of uncomfortable feelings occurred, and outlets for alleviating stress were provided. |

| Steiert (2015) | CCT, design with control sample | Moderate | Age: 10–16, seven with a life-threatening illness and two brothers/sisters | Exp.: 9 (control sample 780) | Individual, six sessions, 90 min, varying from one to three times a week | Control sample Feel K-J | Feel-KJ: emotion regulation | Significant deviations from the control group for emotion regulation. From a sample of nine participants, two children differed significantly, and five children very significantly from the value of the standard sample. Maladaptive strategies: highly significant for three of the children. | - |

| Wallace et al. (2014) | CCT, 1 week after the procedure, 1 month post, 3 months post | Strong | Age: 6–18, siblings of pediatric patients who had undergone pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant | 30 (20/10) | Individual, three times, session's duration varied from 90 min to 2 h | No treatment | The Revised Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale Second Edition (RCMAS−2: anxiety; Second Edition UCLA PTSD Index for DSM-IV: PTSS; the Piers-Harris Children's Self-Concept Scale: self-concept | Compared to the control group, the intervention group showed significantly lower levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms at the final session. Improvements in sibling psychosocial functioning associated with participation in the art therapy interventions. No intervention vs. control group difference for self-concept and anxiety. | - |

| Walsh (1993) | CCT, pre–posttest time-series design, follow up after a month, mixed-method | Strong | Age: 13–17, hospitalized suicidal boys and girls | 39 (21/18) | Group, two times 90 min | Three hours of informal recreational activities (gymnasium free time) | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI): depression; the Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory (SEI): self-esteem | Both groups improved on all measures during and after hospitalization but not significantly. | - |

| Chaves (2011) | Single group pre–posttest, mixed-method | Moderate | Age: 12–20, eating disorder patients, one boy, seven girls | 8 | Group, four times once a week, 240 min | No control | The Subjective Units of Distress (SUDS) scale and visual analog scale (VAS): four negative mood states commonly found in individuals with eating disorders; the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale and the Hartz Art Therapy Self-Esteem Scale: global self-esteem and art therapy-related self-esteem | Global self-esteem did not change. Self-esteem related to art therapy trended upward, though still did not show significant change. The SUDS (distress) and VAS (negative mood) showed the most considerable change after the first group session, but not significantly. | - |

| D'Amico and Lalonde (2017) | Single group pre–posttest, mixed-method | Weak | Age:10–12, 5 boys and one girl with ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder) who required varying degrees of substantial support | 6 | Group, once a week for 21 weeks, 75 min | No control | The Parent and Student Forms of the Social Skills Improvement System Rating Scales (SSIS–RS): social skills and problem behaviors; Observations of the children's progress recorded by the art therapists in their clinical notes (qualitative) | Significant reduction of hyperactivity/inattention. No significant changes in mean, standard scores for social skills. No statistically significant mean changes in the standard scores for problem behaviors. Art therapy enhanced the ability of children with ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder) to engage and assert themselves in their social interactions, while reducing hyperactivity and inattention. | The children demonstrated a shift in self-image, were more confident and assured of their skills. Capable of expressing their ideas, thoughts, and feelings and sharing these. The children enjoyed providing and receiving feedback about their artwork. They appeared to initiate social exchanges independently. Increased capacity to reflect on their behaviors and display self-awareness. |

| Devidas and Mendonca (2017) | Single group pre–posttest | Weak | 47.61% age: 11–12, 9.52% age: 13–14, orphans with low self-esteem | 42 | Group, 10 times once a week | No control | Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale: self-esteem | Art therapy was significantly effective in improving the level of self-esteem. | - |

| Epp (2008) | Single group pre–posttest | Moderate | Age: 6–12, students on the autism spectrum | 66 | Group, once a week 60 min | No control | The SSRS: social behavior problems | Significant improvement in assertion scores, internalizing behaviors, hyperactivity scores, and problem behavior scores. No significant change for responsibility. | - |

| Hartz and Thick (2005) | Two intervention group pre–posttest design | Moderate | Age: 13–18, female juvenile offenders | 27 (12/15) | Group, 10 times during 12 weeks, 90 min | No control | The Harter Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents (SPPA): self- esteem; The Hartz Art Therapy Self Esteem Questionnaire (Hartz AT-SEQ): development of mastery, social connection, and self-approval | No significant differences on the Hartz AT-SEQ: self-esteem. Both groups (a/b) reported increased feelings of mastery, connection, and self-approval (not significant). The art psychotherapy (b) group showed a significant increase in domains of close friendship and behavioral conduct, whereas the art as therapy group (a) did in the domain of social acceptance. | - |

| Higenbottam (2004) | Single group pre–posttest | Weak | Age: 13–14, eighth-grade students, reasons for referral varied: eating disorders, suspected eating disorders, substance abuse, low self-esteem, negative body image, and relational aggression | 7 | Group, eight times once a week, 90 min | No control | Questionnaires: student's feelings around body image and self-esteem adapted from Daley and Lecroy's Go Grrrls Questionnaire | Significant improvements in body image and self-esteem. Participation in the art therapy group may significantly contribute to improved body image and self-esteem and hence the academic and psychological adjustment of adolescent girls. | - |

| Jo et al. (2018) | Single group pre–posttest | Moderate | Age: 7–10, siblings of children with cancer, boys and girls | 17 | Group, 12 times once a week, 60 min | No control | Revised Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale, adapted by Choi and Cho to fit a Korean context: anxiety; DAS test by Silver: Depression; K-CBCL standardized into Korean from the original CBCL: problem behavior; self-esteem: scale developed by Choi and Chun | Significant improvement for self-esteem. Significant decrease in somatic symptoms, aggressiveness, externalizing problems, total behavior problem scale, and emotional instability. No significant results for withdrawal, anxiety/depression, social immaturity, thought problems, and attention problems. |

- |

| Pifalo (2002) | Single group pre–posttest | Moderate | Age: 8–17, girls victims of sexual abuse | 13 | Group, 10 times once a week, 90 min | No control | The Briere Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children (TSCC): trauma symptoms | Significantly reduced anxiety, post-traumatic stress, and dissociative symptomatology scores. Participants showed a decrease in depression, anger, and sexual concerns, although these decreases were not large enough to be statistically significant. | - |

| Pifalo (2006) | Single group pre–posttest | Moderate | Age: 8–10, 11–13, and 14–16, children with histories of sexual abuse | 41 | Group, eight times once a week, 60 min | No control | The Briere Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children (TSCC): trauma symptoms | A statistically significant reduction of Anxiety, Depression, Anger, Posttraumatic Stress, Dissociation, Dissociation-Overt, Sexual Concerns, Sexual Preoccupation, and Sexual Distress. No significant change for Hyper-response, Dissociation-Fantasy. | - |

| Rowe et al. (2016) | Pre–posttest, mixed-method | Moderate | Age:11–20, refugees | 30 | 60% individual, 40 % group | No control | Hopkins Symptoms Checklist (HSC): symptoms of anxiety and depression; The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): behavior and performance in school; Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ): previous experience of trauma; Piers-Harris Self-Concept Scale (PHSCS): self-concept | Improvements in anxiety and self-concept but not significantly. | - |

| Saunders and Saunders (2000) | Pre–posttest, multiyear evaluation | Weak | Age: 2–16, problems: hyperactivity, poor concentration, poor communication, defiant behavior, lying/blaming, poor motivation, change in sleep routine, manipulation and fighting | 94 | Individual, between 2 and 96 sessions | No control | Rating on 24 behaviors typically identified as symptomatic of individual and family dysfunction | Significant positive impact on the lives of clients/families. Clients showed a significant decrease in frequency and severity ratings of problematic behaviors. | - |

| Sitzer and Stockwell (2015) | Single group pre–posttest within-subjects, mixed-method | Weak | Elementary school students with a variety of concerns: emotional dysregulation, lack of social skills, depression, anxiety, lack of focus and concentration, many a history of trauma | 43 | Group, 14 sessions, once a week 60 min | No control | The Wellness Inventory: school functioning attributes: emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and social problems and resilience. Teachers observed students throughout the day for relevant changes in mood and behavior (qualitative) | Results indicated significant increases in resilience, social and emotional functioning. No significant change for behavioral problems. | Overall functioning improves. Improvements in emotional expression, cognition, behavioral interaction, and resilience. |

| Stafstrom et al. (2012) | Pre–posttest | Moderate | Age: 7–18, epilepsy (any type) for at least 6 months | 17 | Group, four sessions 90 min | No control | Childhood Attitude Toward Illness Scale | No significant change in pre- vs. post-group CATIS scores. | - |

ASD, Autism Spectrum Disorder; CATIS, Childhood Attitude Toward Illness Scale; CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist; CCT, Clinical Controlled Trial; DAS, Draw a Story; DSM, Diagnostic Statistic Manuel of Mental Disorders; ID, Intellectual Disability; RCT, Randomized Controlled Trial; LOC, Locus of Control; PTSD, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder; SCIT, Synallactic Collective Image Therapy; SF-AT, Solution Focused Art Therapy; SSRS, Social Skills Rating System; TF-ART, Trauma Focused Expressive Art Therapy; TRS, Teacher Rating Scales; UCLA, University of California at Los Angeles Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index.

Quality of the Studies

Of the 16 RCTs, two studies were evaluated as weak, 11 studies received a moderate score, and three studies were labeled as strong. Concerning the CCTs, five studies were evaluated as weak, one study as moderate, and two studies as strong. Of the 13 pre–posttest designs, five studies were assessed as weak and eight studies as moderate (Table 1).

Study Population

The studies in this review included children and adolescents (ages 2–20) with a wide range of psychosocial problems and diagnoses. Most of the studies included children from the age of 6 years onward, with children's groups ranging from 6 to 15, adolescent groups ranging from 11 to 20, and mixed groups with an age range of 6–20 years. In 13 studies, both boys and girls were included, three studies only included boys, three studies only included girls, and 18 studies did not report the gender of the participants. Psychiatric diagnoses were reported, such as depression, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), conduct disorder (CD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and mild intellectual disability (MID). However, also more specific problems were reported, such as children with suicidal thoughts and behavior, children having a brother/sister with a life-threatening disease, boys and girls in an educational welfare program needing emotional and psychological help, and orphans with a low self-esteem. Another group of children that were reported had medical concerns, such as persistent asthma, traumatic injuries, or serious medical diagnoses such as cancer, often combined with anxiety problems and/or trauma-related problems (Table 1).

Number of Participants

The sample sizes of the RCTs ranged from 16 to 109. The total number of children of all RCTs was 707, of which 317 were allocated to an experimental condition and 390 to a control condition (Table 1). The sample sizes of the CCTs ranged from 15 to 780, and the total number of participants was 1,115. The total number of participants who received an AT treatment was 186; the total number of the control groups was 929. Notice that the sample size for the CCTs was influenced by one study in which a control sample database of 780 was used. The sample size of the included pre–posttest designs ranged from 8 to 94 participants, with a total number of 411 participants (Table 1).

Type of Intervention, Frequency, and Treatment Duration

In the 37 studies, a total of 39 AT interventions were studied. In two studies, two AT interventions were studied. Of the 39 interventions, 30 studies evaluated group interventions, seven studies evaluated an individually offered intervention, one study evaluated an individual approach within a group setting, and in one study, the intervention was alternately offered as a group intervention or as an individual intervention. The number of sessions of the AT interventions varied from once to 25 times. The frequency of the AT interventions varied from once a week (n = 14) or twice a week (n = 5) and variations such as four times a week in 2 weeks (n = 1); six sessions were varying from one to three times a week (n = 1), 10 sessions during 12 weeks (n = 1), and eight sessions in 2 weeks (n = 1). The frequency of sessions has not been reported in nine studies. In five studies, the intervention was offered once (Table 1).

Control Interventions

In six RCTs, care, as usual, was given to the control groups. In study four, this also concerned AT, but it was offered in a program that consisted of different forms of treatment as child life services, social work, and psychiatric consults and therefore did not meet our criteria for inclusion. The control groups receiving “care as usual” received routine education and activities of their programs in school (6); counseling/medications and group activities as art, music, sports, computer games, and dance (8); standard arts- and craft-making activities in a group (9); and standard hospital services (14). One study did not specify what happened as care as usual (2). In five RCTs, a specific intervention of activity was offered in the control condition. These control interventions involved 3 h of teaching (5), a discussion group (7), offering play material (magneatos) (12), and a range of games (11), and one study offered weekly socialization sessions, these sessions were offered by the same professionals as the experimental group, and activities were playing board games, talking about weekend activities, and taking walks on the school grounds (16). Two RCT studies did not mention the condition in the control group (1, 10). Two studies mentioned that the control group did not receive any intervention program (3, 11). One study mentioned that the control group had the same assessments as the treatment group but did not receive therapy until all of the assessments were collected (15).

Regarding the eight CCTs, two studies described the control condition in more detail, consisting of academic work (21) or 3 h of informal recreational activities (24). No intervention was offered to the control group in four studies (19, 20, 22, 23). The control intervention was not described within two studies (17, 18) (Table 1).

Applied Means and Forms of Expression

The applied means and forms of expression in the AT interventions could be classified into three categories: art materials/techniques, topics/assignments given, and language as a form of verbal expression accompanying the use of art materials. Results will be shown for 39 AT interventions in total, coming from 37 studies (Table 2). Two studies applied two different types of AT interventions. These two types of AT will be referred to as 13 a/b and 29 a/b.

Table 2.

Characteristics AT interventions.

| References | Applied means and forms of expression | Art materials | Therapist behavior | Supposed mechanism(s) of change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bazargan and Pakdaman (2016) | Painting sessions. Subjects had 45 min to 1 h to draw. In the end, subjects had 15 min to talk with the therapist and other members about works, feelings, interests, and events. Topics: warm-up activities using painting and coloring, learning about art media, general topics, first childhood memory/family relations, and the directed mental image, visualization, dream and meditation, anger releasing. | Cardboard and acrylic paint and drawing materials | No information given | Reveal what they have inside; leads to new activities and enhances experiences; provides an individual with opportunities through which they can freely express their feelings, affections, needs, and knowledge; achieving a feeling of security toward unpleasant memories of a traumatic event; emotions and thoughts are influenced by conflicts, fears, and desires, and painting allows patients to express them symbolically; offering opportunities to regain a sense of personal agency; explore existential concerns; reconnect to the physical body |

| Beebe et al. (2010) | Opening activity, discussing the weekly topic and art intervention related to chronic illness, art-making, opportunity for the patients to share their feelings related to the art they created, and closing activity. Inclusion of specific art therapy tasks designed to encourage expressions, discussion, and problem-solving in response to the emotional burden of chronic illness. | A variety of materials/techniques were offered, including clay, papier-mâché masks, paint, paper decoration forms, and markers. | Patients are encouraged by the art therapist to express their thoughts and feelings through art materials and interventions. | Helps to cope with troubling feelings and to master a difficult experience; experiences and feelings can be expressed and understood; being able to establish distance between themselves and their medical concerns; processing emotions through art, understanding that their problems are separate from themselves and that the children have an identity outside of their illness |

| Beh-Pajooh et al. (2018) | The subjects had a white sheet of paper to paint freely. At the end of each session, the students explained their painting briefly in the group. | Painting equipment: marker, color pencil, crayon, gouache, and water; white piece of paper | No information given | Effective because it is enjoyable for children; able to express their emotions (e.g., grief, fear and anxiety), feelings (e.g., whishes), and thoughts through projection, which leads them to achieve social adjustment |

| Chapman et al. (2001) | The CATTI (Chapman Art Therapy Treatment Intervention) begins with a graphic kinesthetic activity, followed by a series of carefully worded directives to elicit a series of drawings designed to complete a coherent narrative about the event (trauma). After completing the drawing and verbal narrative, the child is engaged in a retelling of the event using the drawings to illustrate the narrative. | Minimal art media | Children's emotional expressions are validated by the therapist as normal responses to the traumatic event to universalize their experience and reduce anxiety. During the retelling, numerous issues are addressed, including but not limited to misperceptions, rescue and revenge fantasies, blame, shame and guilt, coping strategies, treatment and follow-up plans, traumatic reminders, and reintegration strategies. | Facilitation of the integration of the experience into one's larger, autobiographical life narrative; facilitating the expression and exploration of traumatic imagery as it emerges from memory and finds form; utilizing the integrative capacity of the brain by accessing the traumatic sensations and memories in a manner that is consistent with the current understanding of the transmission of experience to language |

| Freilich and Shechtman (2010) | The child undergoing the therapy selects a topic, and the materials, for a project of interest. When necessary, conducting role-playing and guided discussions are used to increase efficacy. | Materials needed for art projects, such as paper, paints, pictures, journals. | The therapist assists and supports the youngster in carrying the project out. The therapist's role is to help the child identify a meaningful experience, a difficulty, or a conflict. In the process of working on the art piece, the therapist encourages the child to express related feelings and concerns, to explore them, and to reflect on them. | The subject(s) selected in art therapy is a reflection of important issues in the child's life that cannot be expressed directly; reflection leads to the development of insight the selection of goals for change; focusing on emotional exploration of difficulties; identifying problems; sharing problems with the therapist; cathartic experiences that lead to an increase in self-awareness and insight; focusing on an exploration of emotions and reflecting on them |

| Hashemian and Jarahi (2014) | Painting therapy (not further described) | Not described | Not described | Adjustment to their surroundings and therefore changing their inappropriate behavioral patterns; indirect communication with children |

| Kymissis et al. (1996) | Synallactic Collective Image Therapy (SCIT): drawing of a picture. Afterward, a brief presentation and voting one for discussion. The originator gives a title, offers association to it, and says how he/she felt before and after drawing. Other members give their associations. The resulting overlapping of the patient association was the collective image, which represented the basic theme of the session. | Drawing on 12 by 18 inches construction paper with pencils and colored markers. | The therapist takes an active role, directing and encouraging group members in the art activity. The therapists made sure group rules for orderly behavior were maintained. | The opportunity to freely present thoughts and feelings in a non-verbal way, within the structure of the group; the availability of the drawing as a non-verbal channel of communication helping regulation of the level of anxiety, enjoying the group; using artwork facilitated the group process |

| Liu (2017) | All sessions contain two domains: externalizing the problem and finding solutions. The experience associated with stress is drawn on small white paper. The future solution contents will be drawn on colorful, larger paper. All artworks were gathered and reviewed at the end of the intervention (last session) together with the parents. | Small white paper and large colorful paper; a variety of materials/techniques was offered, including drawing, painting, stress ball making, paper cutting, and paper folding | The therapist asks for what is better. The clients “stated needs for today” are related to overall goal(s) for therapy. The client is complimented for his strengths/resources. The therapist askes exception/difference questions. Scaling questions are being asked. Coping questions related to the client's abilities that emerged are being asked. Feedback on the helpfulness of the session is asked. The miracle question is being asked. The client is asked, “what else” was better in today's session. The families are given compliments about their contributions as the session ended. The client is asked to draw what they wish to draw/make but related to their problems. The therapist elicits the client to talk about the drawing and express their feeling. The therapist embeds most of the solution-focused questions and skills in the art-making process and guides the conversation. The therapist monitors that the drawings or the handcrafting are related to the intervention goal and that the session's drawing is focused on future, positive, and brightness. | SF-AT is a combination of Solution Focused Brief Therapy with Art Therapy. SF-AT group therapy in this study adopts a synthesized version of the constructivism theory and psychodynamic theory. This study also uses systems theory to frame the design of SF-AT and elucidate the mechanism of change. SF-AT addressed anger, stress, and emotional issues; non-judgmental acceptance and unconditional care to build rapport and facilitate change; therapeutic alliance; a practice promoting strength-based and positive perspective; empowerment by the strength-based treatment; positively construct information and experience; through positive cognitive construction and social construction, clients can build a new way of problem viewing and solving; this can help with negative thoughts and social impairments |

| Lyshak-Stelzer et al. (2007) | Trauma-focused art therapy (TF-ART). Scripted trauma-specific art activities (directives) for each session. Each participant completed at least 13 collages or drawings compiled in a handmade book format to express a narrative of his or her “life story.” The activities sought to support the youth in reflecting on several questions: What is the difference between feeling safe and unsafe with (a) your peers in the hospital; (b)peers on the street; (c) a staff member; (d) adults in your community; (e) peers at home; and (f) adults at home? When are feelings of fear and anger helpful, and how can they lead to increasing safety? What makes a place safe or dangerous? Can you contrast dangerous activities that you have engaged in during the past with safe activities? What made them safe or dangerous? A second phase of the protocol focused on sharing trauma-related experiences and describing coping responses. On the last session, each presented the book in its entirety to his or her peers. | Collage technique, drawing; making a book | Each adolescent was asked at the beginning of the session to do a “feelings check-in” describing how he or she was feeling in the moment using a single word or sentence, and a “feelings check-out” at the end of the session. After the art-making period, during which minimal discussion took place, the youth were encouraged to display their artwork to peers. They were encouraged but not required to discuss dreams, memories, and feelings related to their trauma history and symptoms. A second phase of the protocol focused on sharing trauma-related experiences and describing coping responses. For example, they were asked to share “some of the words that others have used to hurt you or help you in the past”; to describe nightmares, bad dreams, distressing memories, and flashbacks, as well as strategies used to cope with them; and to discuss traumatic “triggers” that served as reminders of trauma memories or feelings, along with coping strategies. | Exploring fundamental experiences associated with safety and threat; creating an opportunity for ways of orienting to safe and dangerous situations using non-verbal representations; imaginal representations used as the basis for verbalizing the associated experiences in a supportive social context; art products as a starting point for sharing traumatic experiences reduces threat inherent in sharing experiences of trauma by permitting a constructive use of displacement via the production of imagistic representations |

| Ramin et al. (2014) | A diversity of topics and means. Including: Image-making and imaginary drawing. Children started to image-making then draw whatever they prefer in their imaginary area; Children play-act and draw simple bad/good feelings in the group setting; Overall, drawing and discussing/exploring the result. At the ninth session, all the children worked on a group project to bring closure by drawing a ceremony on a large paper together with comments. At the end, a small exhibition of artwork was made. | Drawing on large paper, not further described. | An active role of the art therapist, for instance, recognizing dysfunctional ideas and beliefs children hold about themselves, their relations or interactions with the environment, and helping children identifying and restructuring them by using self-monitoring, problem-solving strategies, and learning coping responses and new skills. | A cognitive-behavioral approach. Non-verbal expression that is possible in art therapy is a safe way; imagination in combination with art-making; in art therapy, children can manage difficult emotions such as anger; art therapy can improve emotional understanding and anger management; in art therapy interventions children can learn coping responses, new skills or problem-solving techniques, increasing sense of belonging, to offer a non-threatening way and to communicate complex feelings and experiences. |

| Regev and Guttmann (2005) | The participants in control group B (art therapy group) created art projects, which were handled in an art-therapy fashion. Each meeting was divided into two parts. In the first 20 min, the children could freely choose to work with any of the available art-project materials and create (or continue to create) whatever they wanted. Then the work would stop, and the children would gather in a circle to discuss a child's (in turn) project. | A variety of materials | The art therapist supervised the group. Led by the art therapist, the discussion focused on questions such as: “how was the project done,” what it reminded the creator of, if it was similar to or different from other projects that he/she had made, if it reflected the way he/she felt that day, if it reflected anything that was happening in his/her life, and what he/she could learn from the project about himself/herself. | Artwork as a medium for self-understanding; artwork as a defense mechanism; artwork helps to ease personal difficulties; artwork helps to achieve emotional relief; artwork helps to achieve positive self-concept |

| Richard et al. (2015) | The intervention includes four sets of facial features (eyes, noses, mouths, and brows) representing four different emotions (happiness, sadness, anger, and fear), as well as a mannequin head. The participant was asked to create four different faces, representing happiness, sadness, anger, and fear. The participant was directed to choose a mouth, nose, eyes, and brows (in that order) that represented the correct emotion. | Four sets of facial features (eyes, noses, mouths, and brows); a mannequin head. Facial features were molded with Super Sculpey. Scotch, Adhesive Putty was used to attach the facial features to the Styro Full Blank Head. On the head paint was applied. | The participant was directed to choose a mouth, nose, eyes, and brows (in that order) that represented the correct emotion. For example, the researcher asked: which one of these mouths do you think would be a happy mouth? The participant received two attempts at choosing the correct feature. If the correct feature was chosen, the researcher responded: yes, that is a happy mouth! If an incorrect feature was selected, the participant was redirected with a statement such as: I do not think that is a happy mouth. A happy mouth has ends that turn upward. Then the participant made a second attempt at selecting the correct feature. If this attempt also failed, the therapist directed the participant to the correct feature. | By using three-dimensional materials to recreate emotions with facial features first the Kinesthetic /Sensory level is engaged through touch, next the Perceptual/Affective level is activated as the face is directly constructed with the materials, and possibly the Cognitive/Symbolic level can be mobilized to reinforce the identification of emotions; art activities involving tactile experiences help dissociative children connect through the ability to touch and create; information processing occurs at each of the first three levels on the ETC: Kinesthetic/Sensory, Perceptual/Affective, and Cognitive/Symbolic |

| Rosal (1993) | Two forms of art therapy: Art as therapy group (a) (experimental): unstructured, the children were encouraged to use the media and be creative with them. Cognitive-behavioral art therapy (b) (Control): use of specific objectives, a stated theme, specific media, and discussion topics. Basic structure: muscle relaxation, imaginary activity, clean up, discussion. Use of cognitive-behavioral principles: behavior contingencies, imagery, modified desensitization, problem-solving techniques, relaxation, stress inoculation, verbal self-instruction. | In both groups, the materials ranged from paint, drawing pencils and pens to clay, collage and construction parts. | Art as therapy group (a): The therapist was active, yet nondirective, by controlling the environment through manipulations of ambiguity and anxiety. Therefore, if tensions in the group were brought to a dangerous level, the therapist intervened through clarifying issues and helping the group find alternatives to the problem. The therapist also assisted any child who was having difficulty with a specific medium. Cognitive-behavioral art therapy group (b): delineated verbal instructions, directions for art media. | The intervention art as therapy could change LOC perceptions through the process of creating art and the experience with the art as a vehicle for discussion and feedback from others. The type of group therapist behavior was based on Whitaker and Lieberman's interpersonal interaction approach to group therapy. Intervention concerning cognitive-behavioral art therapy. The act of producing art may reinforce or enhance internal LOC (Locus of Control) perceptions; each line placed on a paper is the direct result of the child's behavior; A child's movement is reinforced visually by the mark that is produced; there is a direct link between behavior and outcome; drawings are derived from inner experiences The inner experiences may be perceptual, emotional or cognitive processes that are transformed into visual display Without even examining the content, a drawing is a tangible record of internally controlled behaviors; in art therapy, these tangible records are discussed, further reinforcing a child's inner experience. |

| Schreier et al. (2005) | Chapman Art Therapy Treatment Intervention (CATTI): one-to-one session at the child's bedside, completion 1 h. Starting: drawing activity. Drawings are used, creating a narrative about the event; the child can discuss each drawing. Then a retelling of the event, using the drawings to illustrate the narrative. | Minimal art media for drawing. | The child is encouraged to discuss each drawing. During the retelling, numerous issues are addressed, including misperceptions, rescue and revenge fantasies, blame, shame and guilt, coping strategies, treatment and follow-up plans, traumatic reminders, and reintegration strategies. | The art intervention offers an opportunity for the child to sequentially relate and comprehend the traumatic event, transport to the hospital, emergency care, hospitalization, and treatment regimens, and post-hospitalization care and adjustment; the drawing activity is designed to stimulate the formation of images by activating the cerebellum. |

| Siegel et al. (2016) | Patients selected buttons, threads, and words with which they constructed their Healing Sock Creature. The imaginary creatures were sewn and stuffed with magic bean, sand, or fiberfill. Children placed wishes inside the Healing Sock Creature to express their feelings. | Unused hospital socks and small kidney dishes to place buttons and threads. Sewing materials, magic beans, sand, fiberfill. | The therapist becomes the co-creator under the direction of the child by forming a bond of trust as the child shares their design ideas, which may include conversations about symbolic meanings of buttons or colors or threads. | The creative process, exploring deeper meanings in a patients experiences; integrating psychotherapy with multi-arts, the intermodal approach can help children access, process, and integrate traumatic feelings in a manner that allows for appropriate resolution, to reduce stress; this therapy uses imagination, rituals, and the creative process; a symbol can hold a paradox that the rational mind cannot fully explain; choosing a special button or writing a wish mirror, characterizes the child's psyche at this crucial moment; it enables the child to visualize and let go of troubling and unanswerable questions, thus relieving suffering |

| Tibbetts and Stone (1990) | Individual artwork (not further described). | - | The central focus of the art therapist was to assist the subjects to increase in the present their sense of personal power and responsibility by becoming aware of how they blocked their feelings and experiences anger. The approach was non-interpretive, with the participants creating their direct statements and finding their meanings in the individual artwork they created. | Non-interpretive. The art therapy approach utilized in the present study was consistent with the principles of gestalt. The primary role of the therapist as listening, accepting, and validating; art therapy is an integrative approach utilizing cognitive, motor, and sensory experiences on both a conscious and preconscious level; it initially appears less threatening to the client. |

| Jang and Choi (2012) | Each session had the following phases: introduction, activity, and closing. In the introduction phase, the participants greeted one another, did some warm-up clay activities, and were introduced to theme-related clay techniques. In the activity phase, they did individual or group-based activities making shapes using clay. In the closing phase, feedback about their performance was exchanged. | Clay | The art therapist asks questions. No further information provided. | To shed a sense of helplessness or depression with their physical movement of patting or throwing clay pieces in the activities; the continued and repeated experience of pottery-making throughout the sessions contributed to bringing about a positive change in the regulation and expression of emotions; the plasticity of clay made it easy for the participants to finish their clay work successfully; curiosity, toward the process through which a clay piece was transformed into glassy pottery and molding techniques or kiln firing that were learned in each session were factors that contributed to the positive changes; the plasticity of clay also enabled the participants to get a sense of control over the material because they could change the shape as they wished, which contributed to a positive evaluation of their own performance; witnessing the transformation of a piece of clay to complete, glassy pottery, combined with the positive feedback given to the participants, caused a sense of achievement and optimistic outlook on the future. |

| Khadar et al. (2013) | Painting therapy | Not described | The art therapist is present and does not impose interpretations on the images made by the individual or group but works with the individual to discover what the artwork means to the client. | The child makes art in the presence of his or her peers and the therapist, this exposes each child to the images made by other group members on both a conscious and an unconscious level; to learn from their peers and to become aware that other children may be feeling just like them; make meaning of events, emotions or experiences in her life, in the presence of a therapist; the process of drawing, painting, or constructing is a complex one in which children bring together diverse elements of their experience to make a new and meaningful whole; through the group, they learn to interact and share, to broaden their range of problem solving strategies, to tolerate difference, to become aware of similarities and to look at memories and feelings that may have been previously unavailable to them; the image, picture or enactment in the art therapy session may take many forms (imagination, dreams, thoughts, beliefs, memories, feelings); the images hold multiple meanings and may be interpreted in many different ways. |

| Khodabakhshi Koolaee et al. (2016) | First session: Initial introduction, declare short objective of sessions. Second session: Collaborative painting among therapist and child: make a closer contact with children. Third session: Technique of children's scribble: reduce resistance and anxiety in children. Fourth session: Photo collage: Increase cooperation during the treatment process. Fifth session: Drawing with free issue: emotional discharge. Sixth session: Drawing the atmosphere of the hospital and the inpatient portion: express anxiety of children related to atmosphere hospital. Seventh session: Drawing family as animal: evaluate the attitude and relationship of children with family. Eighth session: Anger collage for expressing children's anger and aggressiveness. Ninth session: Drawing with free issue: express emotion. Tenth session: Evaluate the effectiveness of drawing on aggressiveness and anxiety. Eleventh session: Follow-up session. |

Photo collage, drawing. Not further described. | Not described | Painting provides opportunities to communication and non-verbal expression; it can serve as a tool to express the emotions, thoughts, feelings, and conflicts; anxiety symptoms of children emerge in metaphorical symbols such as play and painting; drawing permits the children to convey their thoughts and dissatisfaction with environment-related to the hospital, they can express their emotion in safe atmosphere: drawing improves anger management and emotional perception with learning the accurate coping response, the techniques and problem-solving skills, and provides the non-invasive way to communicate in a complex emotional situation. |

| Pretorius and Pfeifer (2010) | Four themes: (1) Establishing group cohesion, and fostering trust by group painting, guided fantasy with clay, and story-making through a doll. (2) Exploration of feelings associated with the abuse by drawing feelings, drawing perpetrators, placing of these in boxes. (3) Sexual behavior and prevention of revictimization by role-playing and mutual storytelling (4) Group separation by painting, drawing, or sculpting feelings associated with leaving the group | Paint and drawing materials, not further specified, and clay. | Therapeutic behavior based on the existential-humanistic perspective, and incorporated principles from Gestalt therapy, the Client-centered approach, and the Abuse-focused approach | Group psychotherapy can ameliorate difficulties encountered in the use of individual therapies with sexually abused children, including an inherent distrust of adults, fear of intimacy with and disclosure to adults, secrecy and defensive behavior; group therapy also offers children the opportunity to realize that they are not alone in their experiences and that other children have had similar experiences, this realization may be a great source of relief that helps reduce the sense of isolation; art therapy involves a holistic approach in that it not only addresses emotional and cognitive issues but also enhances social, physical and developmental growth; art therapy appears to help with the immediate discharge of tension and simultaneously minimize anxiety levels; the act of external expression provides a means for dealing with difficult and negative life experiences; art therapy, therefore, not only assists with tension reduction but also with working through issues, thereby leading to greater understanding; Group art therapy acknowledges the concrete thinking style of latency-aged children and accordingly provides an opportunity for non-verbal communication; contact with group members may also decrease sexual and abusive behaviors toward others. |

| Ramirez (2013) | Six interventions were repeated twice: (1) Predesigned mandala template/complete design. (2) Create self-portraits (3) Design a collage. (4). Mold clay into a pleasing form, which could be an animal, a person, an object, or an abstract form. (5) Visualize a landscape from imagination and paint it. (6) Arrange a variety of objects in a pleasing orientation and draft the still life with a pencil | Color pencils, markers, crayons, and oil pastels; charcoal, ink, or mixed media, clay; acrylic paints or watercolors | The therapist facilitates the creation of the artistic product and is supportive. The art therapist suggests expressive tasks in a manner that shows respect for their way of reinventing meaning and involves subject matter that is of interest to the teen. | The creative process involved in artistic self-expression helps people to become more physically, mentally, and emotionally healthy and functional, resolve conflicts and problems, develop interpersonal skills, manage behavior, reduce stress, handle life adjustments, and achieve insight. |

| Steiert (2015) | The given theme was Heroes; no further information provided | An extensive range of different materials was available. There was wood, stone, plaster, and a comprehensive selection of paint and drawing materials, also felt and other textiles. | Decisions on what to do, which materials to use were discussed with the patients. The shaping of the heroes was supported by talking about this, viewing comics, searching images, watching videos. For dealing more intensely with the heroes, suggestions from the therapist were given. | The processing on a symbolic, playful and imperious level, gives the child the opportunity for a gradual approach for their conflicts, without defense mechanisms undermining it; heroes and heroic stories support children and adolescents not just in their childhood development but have potentially also a positive influence on processing disease; in the children and adolescents can find their emotional reality and find solution options for the handling of these conflicts' themes. |