Abstract

High expression of centrosomal protein CEP55 has been correlated with clinico-pathological parameters across multiple human cancers. Despite significant in vitro studies and association of aberrantly overexpressed CEP55 with worse prognosis, its causal role in vivo tumorigenesis remains elusive. Here, using a ubiquitously overexpressing transgenic mouse model, we show that Cep55 overexpression causes spontaneous tumorigenesis and accelerates Trp53+/− induced tumours in vivo. At the cellular level, using mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), we demonstrate that Cep55 overexpression induces proliferation advantage by modulating multiple cellular signalling networks including the hyperactivation of the Pi3k/Akt pathway. Notably, Cep55 overexpressing MEFs have a compromised Chk1-dependent S-phase checkpoint, causing increased replication speed and DNA damage, resulting in a prolonged aberrant mitotic division. Importantly, this phenotype was rescued by pharmacological inhibition of Pi3k/Akt or expression of mutant Chk1 (S280A) protein, which is insensitive to regulation by active Akt, in Cep55 overexpressing MEFs. Moreover, we report that Cep55 overexpression causes stabilized microtubules. Collectively, our data demonstrates causative effects of deregulated Cep55 on genome stability and tumorigenesis which have potential implications for tumour initiation and therapy development.

Subject terms: Oncogenes, Mechanisms of disease

Sinha et al. demonstrate that overexpression of centrosomal protein Cep55 in mice is sufficient to cause a wide-spectrum of cancer via multiple mechanisms including hyperactivation of the Pi3k/Akt pathway, stabilized microtubules and a defective replication checkpoint response. These findings are relevant to human cancers as high CEP55 expression is associated with worse prognosis across multiple cancer types.

Introduction

Genomic instability (GI) is a hallmark of almost all human cancers. Chromosomal instability (CIN) is a major form of GI, which refers to the acquisition of abnormal chromosome numbers or structures1. CIN in cancers primarily occurs due to defective mitosis, including biased chromosome segregation and failure to undergo cytokinesis. Both mitotic checkpoint weakness and/or hyperactivation can also lead to CIN, exploring its genetic basis has the potential to uncover major mechanism of GI in cancers and therapeutic modality2.

CEP55 is a coiled-coil centrosomal protein which plays a critical role in cytokinetic abscission during mitotic exit3. CEP55 is a cancer testis antigen expressed during embryogenesis and is silent in most adult tissues except testis; however, it is re-expressed in a wide variety of cancers4. Over the last decade, multiple studies have shown variable associations of overexpressed CEP55 with poor prognosis in human cancers (reviewed by Jeffery et al.4). On the other hand, loss-of-function mutations in CEP55 cause late gestation lethality and Meckel-like and MARCH syndromes5–8. Notably, increased CEP55 expression correlates with functional aneuploidy in multiple cancer types, as defined by the CIN70 gene signature9. It is also part of a 10-gene signature associated with drug resistance, CIN, and cell proliferation10. Moreover, as part of the 31-gene cell-cycle progression (CCP) signature, it strongly correlates with actively proliferating prostate cancer cells11. Likewise, we have shown that CEP55 is part of a 206 gene signature, representing genes enriched in promoting CIN, associated with aggressiveness of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)12.

Mechanistically, wild-type TP53 suppresses CEP55 through PLK1 downregulation and therefore, cancers with TP53 mutations often have elevated CEP55 levels13. In human cancers, CEP55-overexpression results in cell transformation, proliferation, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, invasion, and cell migration via upregulation of the PI3K/AKT pathway through direct interaction with the p110 catalytic subunit of PI3K14,15. Likewise, CEP55 interacts with JAK2 kinase and promotes its phosphorylation16. We have recently shown that Cep55 overexpression in mice causes male-specific sterility through the hyperactivation of Pi3k/Akt pathway in mice17. Furthermore, we showed that CEP55 is a determinant of aneuploid cell fate during perturbed mitosis in breast cancers and could be targeted through MEK1/2-PLK1 inhibition18. Moreover, recently Cep55 has been shown to regulate anaphase I of the meiotic oocytes19. Collectively, these studies highlight the association of CEP55 overexpression with various human malignancies in a context-dependent manner. Though these in vitro and clinical correlation studies have so far established the link between CEP55 overexpression and cancer, the underlying mechanism by which CEP55 promotes tumorigenesis in vivo remains elusive.

Here, we report that Cep55 overexpression in a mouse model causes high incidence of spontaneous tumorigenesis with a wide spectrum of highly proliferative and metastatic tumors. Notably, Cep55 overexpression accelerates Trp53+/−-induced tumorigenesis. Using mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), we show that Cep55 overexpression facilitates rapid proliferation by modulating multiple cell signaling networks, particularly hyperactivation of Pi3k/Akt pathway which consequently impacts on Chk1-dependent replication checkpoint. Moreover, we found that Cep55 overexpression causes both numerical and structural CIN due to stabilized microtubules. Collectively, our data demonstrate a causal link of overexpressed Cep55 with tumorigenesis, driven through its multiple cellular functions.

Results

Cep55 overexpression drives tumorigenesis in vivo

To characterize the pathophysiological role of CEP55 overexpression in vivo, we utilized our recently reported transgenic mouse model17. Since CEP55 is highly overexpressed in multiple human cancers irrespective of its role in cell division (Supplementary Fig. 1A–E), we asked if Cep55 overexpression causes spontaneous tumorigenesis in vivo. We monitored a cohort of wild type (herein referred to as Cep55wt/wt, n = 40), heterozygous transgenic (Cep55wt/Tg, n = 40), and homozygous transgenic (Cep55Tg/Tg, n = 50) Cep55 mice (both males and females) over a period of 2.5 years for spontaneous tumor formation. We observed that the Cep55Tg/Tg mice developed various types of tumors at relatively long latencies (median survival 15 months) (Table 1) compared to other well-known oncogenic tumor models (K-rasG12D 20, Pten+/− 21, and Trp53−/−22,23). However, homozygous-Cep55 overexpressing mice succumbed to cancer significantly earlier (p < 0.0001) than Cep55wt/Tg and Cep55wt/wt littermates (Fig. 1a). Notably, more than 50% of the Cep55Tg/Tg mice were culled between 13 and 15 months due to irreversible weight loss (>15%), reluctance to move and/or eat and showed development of tumors (Supplementary Fig. 2A).

Table 1.

Distribution of cancer spectrum in Cep55 transgenic mice.

| No. | Cancerous Lesions | Cep55wt/wt(n = 40) | Cep55wt/Tg(n = 40) | Cep55Tg/Tg(n = 50) | Cep55wt/wt vs Cep55Tg/Tg, Cep55wt/Tg vs Cep55Tg/Tg | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | # | % | p valuesa | |||

| 1 | Lymphoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 51.42 | 6.0 × 10−6 | 6.0 × 10−6 |

| B-Cell Lymphoma | – | – | 11 | 61.11 | 0.0010 | 0.0010 | |||

| T-Cell Lymphoma | – | – | 7 | 38.88 | 0.0159 | 0.0159 | |||

| 2 | Undifferentiated sarcoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 25.71 | 0.0039 | 0.0039 |

| Fibrosarcoma | – | – | 3 | 33.33 | 0.2509 | 0.2509 | |||

| Hemangiosarcoma | – | – | 6 | 66.67 | 0.0317 | 0.0317 | |||

| 3 | Bronchogenic adenocarcinoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 17.14 | 0.0317 | 0.0317 |

| 4 | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 8.57 | 0.2509 | 0.2509 |

| 5 | Gastric Carcinoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 14.28 | 0.0632 | 0.0632 |

| 6 | Intestinal Papillary Carcinoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 8.57 | 0.2509 | 0.2509 |

| 7 | Myelogenous Leukemia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 20 | 0.0159 | 0.0159 |

| 8 | Hepatic Hyperplasia (foci of cellular alteration) | 1 | 2.22 | 4 | 8.69 | 12 | 34.28 | 0.0051 | 0.1019 |

| 9 | Splenic follicular Hyperplasia | 1 | 2.22 | 4 | 8.69 | 8 | 66.66 | 0.0398 | 0.5373 |

| 10 | Endometrial Hyperplasia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 33.33 | 0.1259 | 0.1259 |

| 11 | Lipoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 12 | Alveolar-Bronchiolar Adenoma | 0 | 0 | 10 | 22.22 | 15 | 42.85 | 0.0001 | 0.6426 |

| 13 | Hepatoma | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4.34 | 2 | 5.7 | 0.5006 | 1.0 |

aP values: Fisher’s exact tests.

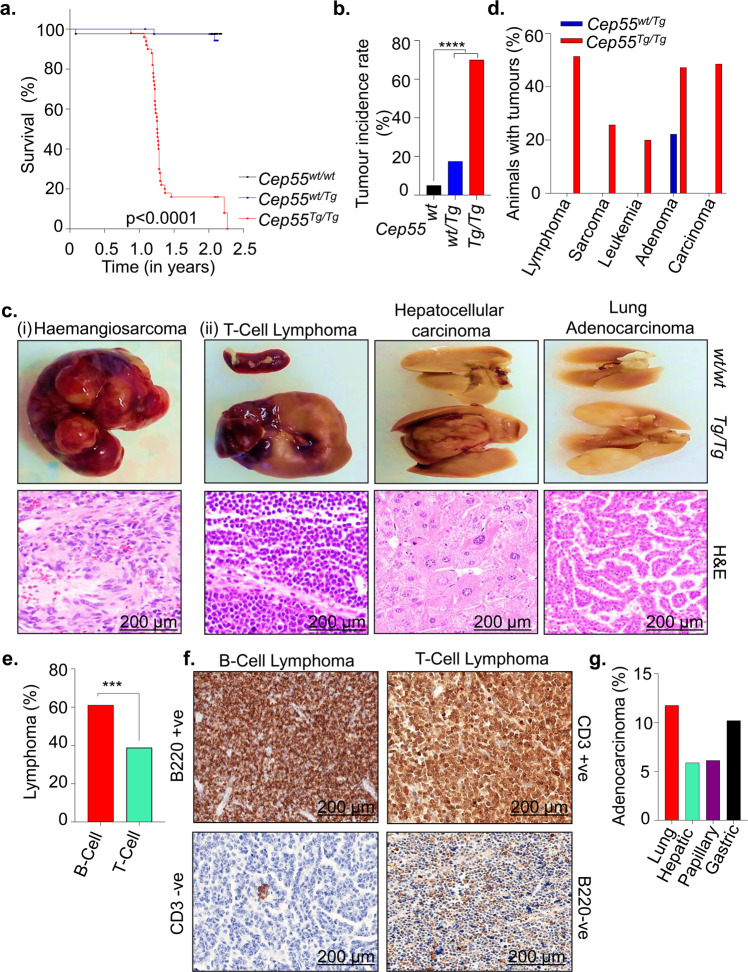

Fig. 1. Cep55 overexpression causes spontaneous tumorigenesis in vivo.

a Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of mice of indicated genotypes (n ≥ 40 per group) showing that Cep55Tg/Tg mice were more susceptible to form tumors compared to their control counterparts; Log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test was performed to determine P-value < 0.0001. b Percentage of cancer incidence rate among mice of indicated genotypes (n ≥ 40 per group); Fischer exact test was performed to determine P-value < 0.00001 (****). c Representation images of gross morphology (upper panels) and H&E stained microscopic images (lower panels) of selected sections of (i) haemangiosarcoma in liver of tumor-bearing Cep55Tg/Tg mice from which the tumor cell lines (TCL) were established (discussed later in Supplementary Fig. 4) (ii) other tumor lesions (T-cell lymphoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and Lung Adenocarcinoma) from different organs among Cep55Tg/Tg mice (scale bars, 200 µm). d Percentage of animals with respective cancer types observed in the transgenic cohorts. e Percentage of animal with types of lymphomas observed in the respective tumor-bearing Cep55Tg/Tg mice. Fischer exact test was performed to determine P-value < 0.0029 (***). f Representative images of B220 and CD3 immunostaining used to categorize the respective types of lymphomas. B220+ve and CD3-ve were classified as B-cell lymphoma while CD3+ve and B220-ve were classified as T-Cell lymphoma (scale bars, 200 µm). g Percentage of adenocarcinoma in the respective organs observed in the tumors bearing Cep55Tg/Tg mice.

We observed that 70% (35/50) of the Cep55Tg/Tg mice developed a wide spectrum of tumor lesions, including lymphoma, sarcoma, leukemia, and various adenocarcinomas (Fisher exact test p < 0.00001; Fig. 1b–d, Supplementary Fig. 2B and Table 1) compared to only 17.5% (7/40) in Cep55wt/Tg and 5% (2/40) in Cep55wt/wt littermates (Fig. 1b). Notably, the tumor burden observed in Cep55Tg/Tg mice varied between 1 and 3 tumors per animal (Supplementary Fig. 2C) with tumors originating in multiple tissue types (Supplementary Fig. 2D) in comparison to Cep55wt/Tg, which uniformly developed only adenomas in the lung. Likewise, the Cep55Tg/Tg mice also exhibited a higher incidence of lymphomas, in particular more B-cell lymphoma (1.5-fold) than the T-cell lymphoma (Fig. 1d, e, Table 1). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining using B220 (B-cell marker) and CD3 (T-cell marker) specified the incidence of B-cell and T-cell lymphomas, respectively (Fisher exact test p < 0.0029; Fig. 1e, f). Independently, we observed a higher incidence of sarcomas, particularly haemangiosarcoma than fibrosarcoma (in liver and spleen) (Supplementary Fig. 2D, E) and a higher incidence of lung and gastric adenocarcinomas compared to other carcinomas (Fig. 1g). We also observed a significant increase in hyperplastic lesions (in liver, spleen, and endometrium) in Cep55Tg/Tg mice compared to the cohort of other genotypes (Fisher exact test p < 0.0001; Supplementary Fig. 2F).

The primary cancers observed in the Cep55Tg/Tg mice were highly aggressive in nature with increased Ki67 positivity staining compared to adjacent tissues, as perceived by the gross morphology and mass of the organs in which these tumors originated (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 2G, H). In addition, we observed that ~16% of the mice developed metastases in the lungs and liver (Supplementary Fig. 2I). Collectively, these data highlight that Cep55 overexpression alone is sufficient to drive tumorigenesis in mice, causing a broad spectrum of cancers and associated with metastasis.

Cep55 overexpression accelerates Trp53+/− induced tumor development in mice

Our data suggest that Cep55 overexpression-induced tumorigenesis mimics the tumorigenesis pattern observed in Trp53−/− mice22,23, as it induces a significantly higher percentage of lymphomas (~51%) and sarcomas (~25%) (Fig. 1d). A previous report has shown that wild-type TP53 restrains CEP55 expression through PLK113. In addition, data mining suggests that CEP55 levels are significantly higher in lung and hepatocellular tumors that exhibit allelic TP53 copy number loss than in TP53 diploid tumors (both p < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U test) (Supplementary Fig. 3A). Consistent with this, we observed a high p53 protein level, which is most likely an indication of mutated Trp53, as well as reduced staining of its target p21 in representative Cep55Tg/Tg tumor tissues than normal adjacent tissues (Fig. 2a, b)

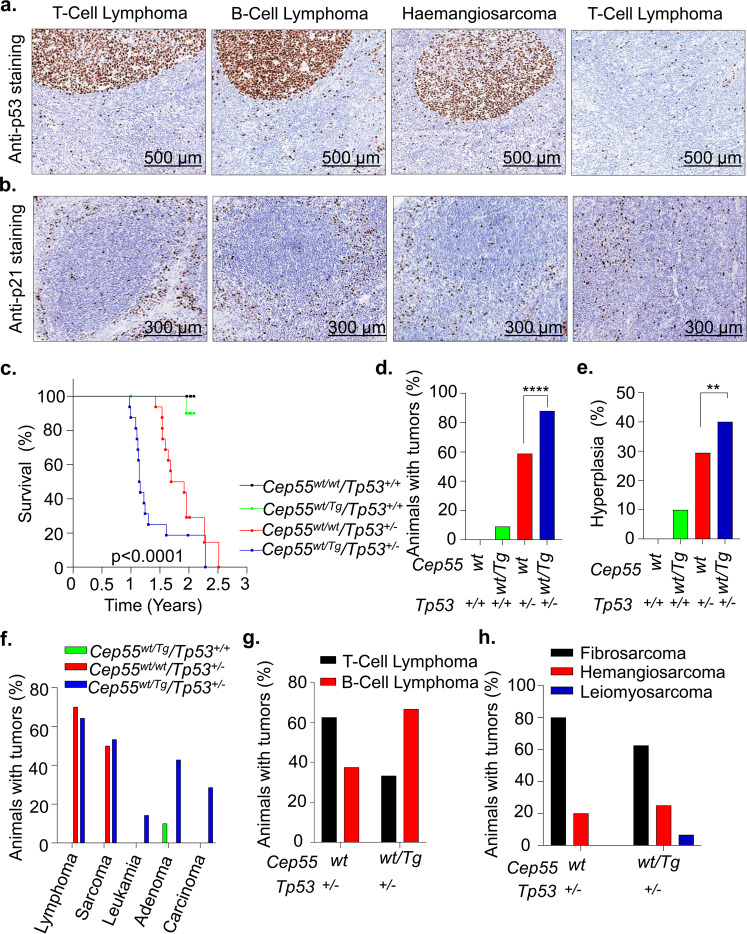

Fig. 2. Heterozygous Cep55 transgenic expression accelerates Trp53+/−-induced tumorigenesis in mice.

a Representative images of p53 immunohistochemical staining on tumor sections of respective subtypes observed in the Cep55Tg/Tg mice showing the presence of p53 positive cells in the tumor lesion compared to adjacent normal tissue from the same mice (scale bars, 500 µm). b Representative images of p21 immunohistochemical staining on tumor sections of respective subtypes observed in the Cep55Tg/Tg mice showing the presence of p21 negative cells in the tumor lesion compared to adjacent normal tissue from the same mice (scale bars, 300 µm). c Kaplan–Meier survival analysis highlighting the tumor-free survival of the mice of indicated genotypes (n ≥ 10 per group) demonstrating that Cep55wt/Tg; Trp53wt/− mice were more susceptible to form tumors with a shorter latency period (~14 months) compared to control littermates; Log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test was performed to determine P-value < 0.0001. d–h Percentages of overall cancer incidence (d), hyperplastic lesions (e), cancer spectrum (f), lymphoma (g) and sarcoma burden (h) among mice of indicated genotypes (n ≥ 10 per group). Fischer exact test was performed to calculate P-value < 0.01 (**) and <0.0001 (****).

Next, we inter-crossed Cep55Tg/Tg female mice with Trp53−/− male mice to establish bi-transgenic cohorts of Cep55wt/Tg;Trp53+/− (n = 15), Cep55wt/wt;Trp53+/− (n = 17), Cep55wt/Tg;Trp53+/+ (n = 11), and Cep55wt/wt;Trp53+/+ (n = 10) mice. These cohorts of mice were monitored regularly for a period of 2.5 years for spontaneous tumor development. Interestingly, we observed that the Cep55wt/Tg;Trp53+/− mice succumbed to a broad spectrum of cancer development (spleen, liver, and lung) with reduced latency (median survival of 13.8 months; p < 0.0001) when compared to the Cep55wt/wt;Trp53+/− cohort (median survival of 21.6 months) (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 3B–F, Supplementary Table 1). The histological features observed across these tumors are described in Supplementary Table 2. Notably, the entire cohort of Cep55wt/Tg;Trp53+/− mice exhibited a time frame of tumor development similar to that of Cep55Tg/Tg mice (Fig. 2c).

Further, the incidence of tumorigenesis observed in Cep55wt/Tg;Trp53+/− mice was also significantly higher (~85%; Fisher exact test p < 0.0001) in comparison to Cep55wt/wt;Trp53wt/− (~50%) with 1–3 tumors per animal (Fig. 2d). The Cep55wt/Tg;Trp53+/− mice also displayed a significantly higher incidence of hyperplastic lesions (Fisher exact test p < 0.01) (Fig. 2e), and a similar incidence to that observed in Cep55Tg/Tg mice (Supplementary Fig. 2F). Histopathological analysis indicated the presence of a number of neoplastic lesions (Fig. 2f, Supplementary Fig. 3B, Supplementary Table 1) that were similarly observed in Cep55Tg/Tg mice (Fig. 1c, d, and Table 1). Notably, though similar fractions of Cep55wt/wt; Trp53+/− and Cep55wt/Tg; Trp53+/− animals developed lymphomas and sarcomas (Fig. 2f); however, their lymphoma spectrums were different. There was a higher incidence of B-cell lymphomas than T-cell lymphomas in the Cep55wt/Tg;Trp53+/− mice compared to Cep55wt/wt;Trp53+/− mice (Fig. 2g). Further, the Cep55wt/Tg;Trp53+/− mice demonstrate a similar occurrence of fibrosarcoma and haemangiosarcoma (in liver and spleen), as observed in Cep55Tg/Tg mice (Fig. 2h). Taken together, this suggests that Cep55 overexpressing tissues have better tumor incidence when p53 protective effect is reduced in p53-heterozygous compared to p53-wild-type animals.

Cep55 overexpression confers a survival advantage through activation of signaling networks

In multiple human cancers, deregulated expression of CEP55 has been linked to enhanced proliferation, migration, invasion, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and tumorigenesis4. To analyze the impact of Cep55 overexpression in vitro, we use primary and spontaneously immortalized MEFs isolated from E13.5 embryos (Supplementary Fig. 4A). We observed significantly higher Cep55 transcript and protein levels in the primary Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs compared to MEFs from other genotypes (Fig. 3a, b). Next, to determine the growth potential and the senescence rate in the primary MEFs, we performed a 3T3 assay and observed that the Cep55Tg/Tg primary MEFs had a significantly higher growth rate along with more G2/M cells compared to Cep55wt/Tg and Cep55wt/wt MEFs (Fig. 3c, d). Likewise, the immortalized Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs also exhibited similar enhanced proliferative capacity and increased Ki67 staining over time (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 4C). To define if Cep55 overexpression alone could confer enhanced proliferative capacity independent of mitogenic signals, we serum-starved the immortalized MEFs of each genotypes and observed higher cell proliferation capacity in Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs (~60 h) compared to MEFs from other genotypes, highlighting a self-mitogen gaining capability to proliferate and survive in conditions of serum-starvation (Supplementary Fig. 4D).

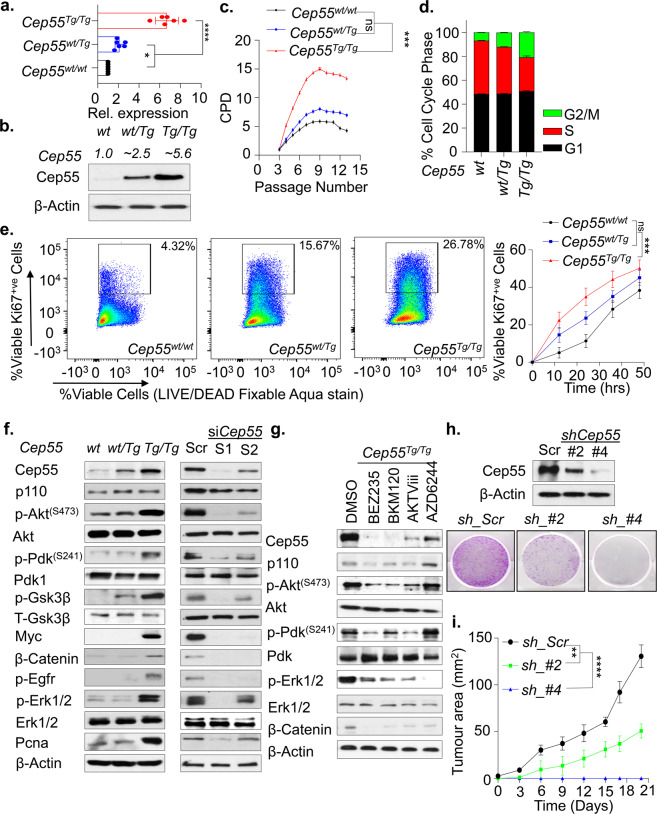

Fig. 3. Cep55 confers survival advantage through activation of signaling networks.

a Expression of Cep55 transcripts observed in the primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) of respective transgenic Cep55 genotypes. Three independent experiments with two technical replicates were performed. Error bars represent ± Standard Deviation (SD). One-way ANOVA test was performed to determine P-value < 0.05 (*) and < 0.0001 (****). b Immunoblot analysis of Cep55 expression in the whole cell lysates of the primary MEFs of each genotype. β-Actin was used as a loading control and relative fold difference in expression of Cep55, (indicated above calculated by densitometric analysis using ImageJ) observed among the MEFs of respective genotype (number of experimental representation, n = 2). c Proliferation measured as a function of passage number [indicated as CPD (cumulative population density)] using NIH-3T3 protocol in primary Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs in comparison to its littermates (n = 3 independent experiments with two technical replicates were performed. Error bars represent ± SD). One-way ANOVA test was performed to determine P-value < 0.0001 (****). d Cell-cycle profile of primary MEFs of indicated genotype measured post 24 h of culture by propidium iodide staining followed by FACS (n = 3 independent experiments with two technical replicates). Error bars represent ± SD). Two-way ANOVA test was performed to determine P-value is demonstrated in Supplementary Table 3. e FACS plot representing the percentage of Ki67 positive staining of viable cells from the respective genotype post 12 h of culture wherein 100,000 viable events were collected for each genotype (left). Quantification of the percentage of Ki67 positive viable cells of each genotype at the representative time points (right). Error bars represent the ± SD from three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA test was performed to determine P-value; <0.001 (***) and ns (not significant). f Immunoblot analysis of the whole cell lysates collected post 24 h culture from the immortalized MEF’s of indicated genotypes (left panel) and post 48 h from the respective siRNA treated Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs (right panel) indicating the impact of Cep55 overexpression on multiple cell signaling pathways. β-Actin was used as a loading control. g Immunoblot analysis of the whole cell lysates collected after 24 h of treatment of immortalized Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs with the respecting inhibitors such as BEZ235 (pan-PI3K/AKT inhibitor), BKM120 (pan-PI3K inhibitor), AKTVIII (AKT inhibitor), and AZD6244 (MEK1/2 inhibitor). β-Actin was used as a loading control. h Immunoblot analysis of the whole-cell lysates collected from the respective isogenic Cep55-depleted TCLs at 24 h validating the levels of Cep55 expression. β-Actin was used as a loading control (top panel). Representative images of colony formation at 14 days determined using crystal violet staining in control and Cep55-depleted TCLs (bottom panel). i Six-week-old female NOD/Scid cohorts of mice were injected subcutaneously with the control and Cep55-depleted clones. Growth rates (area, mm2) of the tumors were measured using a digital caliper. Differences in growth were determined using Student’s t test, P ≤ 0.0001 (****). Graph represents the mean tumor area ± SD, n = 5 mice/group.

CEP55 has been shown to upregulate AKT phosphorylation through direct interaction with p110 catalytic subunit of PI3 kinase (PI3K) and enhance cell proliferation in vitro14,15,17. Likewise, we have shown that MYC regulates CEP55 transcriptionally in breast cancer18. Thus, to characterize the molecular signaling involved in cell proliferation and survival, we investigated the impact of Cep55 overexpression on Pi3k/Akt - and Erk-dependent signaling networks. Interestingly, immunoblot analysis using whole cell lysates from the MEFs of each genotype demonstrated Cep55 dosage-dependent increase in phosphorylation of AktS473 and its upstream regulator Pdk1S241 in Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs compared to wild type and heterozygous MEFs (Fig. 3f). In addition, we also observed an upregulation of Mapk-dependent signaling molecules, including increased-phosphorylation of Egfr, Erk1/2, Myc, and β-catenin, along with increased Pcna, a proliferation marker, in Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs (Fig. 3f). Similar changes were observed in representative tissue lysates (Supplementary Fig. 4E). Notably, the effects on the signaling networks were specific to Cep55 overexpression as knockdown of Cep55 using two different siRNA oligonucleotides in Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs remarkably diminished Pi3k/Akt and Mapk-dependent signaling pathway activities (Fig. 3f). Reconstitution of Cep55 in siRNA knockdown MEFs rescued the signaling networks of Pi3k/Akt and Mapk (Supplementary Fig. 4F). Furthermore, to characterize the role of Cep55 overexpression in promoting cell proliferation and survival through activated signaling pathways, we used a wide range of Pi3k/Akt, mTor and Erk1/2 pathway-specific inhibitors. We observed that the Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs were significantly more sensitive to Akt, Pi3K and pan-Pi3k/Akt/mTor inhibitors, but not to mTor or Erk1/2 inhibitor treatments alone (Supplementary Fig. 4G). Blocking some of these signaling pathways but not others markedly reduced Cep55 levels suggesting positive feedback loops between Cep55 and these signaling pathways (Fig. 3g and Supplementary Fig. 4H)).

To further decipher the impact of overexpressed Cep55 on tumorigenesis, we established cell lines from some of the tumors that developed in Cep55 overexpressing mice (herein abbreviated as tumor cell lines (TCLs)), in particular haemangiosarcoma of the liver (Fig. 1ci). These cells exhibited a mixed population of aneuploidy (both bi- and multinucleated), implying a genomically unstable phenotype (Supplementary Fig. 5A). Similarly, upon transient Cep55 knockdown using siRNA in the TCL, these cells significantly grew slower than siscramble transfected cells with a concomitant reduction in signaling networks that were complemented after the restoration of Cep55 expression (Supplementary Fig. 5B, C). Likewise, constitutive Cep55 knockdown in this line using shRNAs reduced anchorage-independent colony formation, G2/M cell population along with reduced proliferation capacity and tumor formation dependent on the extent of reduction of Cep55 levels (Fig. 3h, i, Supplementary Fig. 5D–G). Consistently, Cep55 knockdown TCL was significantly refractory to Pi3k/Akt inhibitor sensitivity (Supplementary Fig. 5H), suggesting a dependency on Pi3k/Akt signaling. Taken together, these data highlight the crucial role of Cep55 in regulating proliferation and survival-associated signaling networks and its essential function in tumor formation.

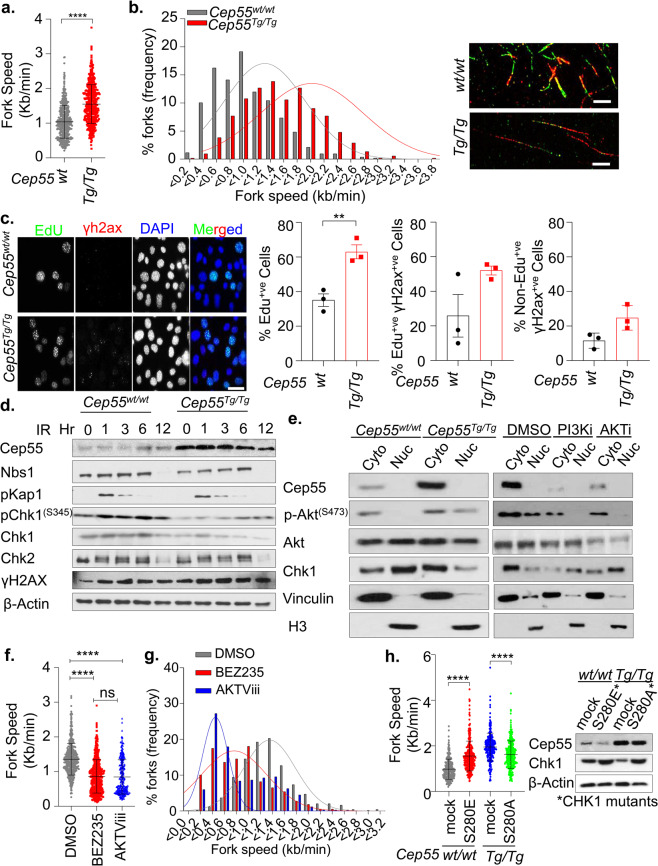

Cep55 overexpression leads to altered Chk1 distribution causing replication stress in an Akt-dependent manner

Overexpression and/or hyperactivation of AKT has previously been associated with cytoplasmic sequestration of CHK1, hence loss of its checkpoint activity that can ultimately lead to enhanced proliferation capacity with increased GI24. Since Cep55 overexpression increases Akt signaling, we investigated the impact of Cep55 overexpression on replication by examining the replication fork progression rate using DNA fiber assay. We found that the Cep55-overexpressing MEFs exhibited a significant increase in replication fork speed (median speed: 1.47 kb/min) compared to wild-type cells (median speed: 1.03 kb/min) (Fig. 4a, b). On the contrary, transient silencing of Cep55 in these cells significantly reduced replication fork speeds, suggesting that Cep55 overexpression increases proliferation by allowing cells to replicate faster than the Cep55wt/wt MEFs (Supplementary Fig. 6A, B). An increase in fork speed by 40% above the normal fork progression speed can induce DNA damage and genome instability25. Next, we investigated the impact of increased replication speed on DNA damage response in the Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs. Interestingly, we initially observed that the Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs exhibited a significantly higher percentage of γ-H2ax positive cells (>5 γ-H2ax foci per cell) when compared to the Cep55wt/wt MEFs (Supplementary Fig. 6C, D). Likewise, we found that Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs have a higher percentage of EdU-positive cells, compared to Cep55wt/wt MEFs (Fig. 4c). Notably, an increase in the percentage of γ-H2ax positive cells was seen in both Edu-positive and Edu-negative population of the Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs, suggesting that DNA damage is persistent (Fig. 4c). Despite this increase in baseline damage, no significant differences in DNA damage response signaling were apparent between these lines when these cells were challenged with 6-Gy γ-irradiation (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Fig. 6E). However, we noticed a marked reduction in total Chk1 levels in Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs (Fig. 4d). ATR-dependent CHK1 is a well-established effector of DNA damage and replication stress response which is also required for faithful chromosome segregation26. Since Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs have highly elevated Akt signaling (Fig. 3f), we initially investigated the subcellular Chk1 distribution in MEFs of different Cep55 genotypes. Compared to Cep55wt/wt MEFs, the Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs show relatively higher Chk1 levels in cytoplasmic but reduced levels in nuclear fraction (Fig. 4e, left). Notably, treatment of Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs either with Pi3k or Akt inhibitor markedly altered the localization of Chk1 from cytoplasmic to nuclear fraction, confirming that the activation of Akt signaling in Cep55-overexpressing cells sequesters Chk1 in the cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 4e, right). To further confirm the involvement of an Akt-mediated replication stress, we treated Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs with either BEZ235 or AKTVIII inhibitors and performed DNA fiber assay. Our data showed that treatment of Cep55-overexpressing cells with Akt inhibitors significantly reduced replication fork speeds compared to DMSO treated cells (Fig. 4f and g and Supplementary Fig. 6F). AKT phosphorylates CHK1 at serine 280 and impairs its nuclear localization and checkpoint activity independent of ATR24. To determine the crucial role of Cep55-Akt-dependent checkpoint deficiency, we transiently reconstituted Cep55Tg/Tg cells with S280A mutant (that cannot be phosphorylated by active-AKT), and Cep55wt/wt cells with S280E mutant (mimics constitutive AKT-dependent phosphorylation). Our data showed that while S280E mutant significantly increased replication fork speed in Cep55wt/wt cells, the S280A mutant reconstituted Cep55Tg/Tg cells on contrary show significantly decreased replication fork speed, suggesting that the checkpoint activity is impaired in Cep55-Akt-dependent manner in these cells (Fig. 4h, Supplementary Fig. 6G). Collectively, our data suggest that overexpression of Cep55 impairs Chk1-mediated checkpoint activation leading to faster replicating cells with persistent DNA damage in our model.

Fig. 4. Cep55 overexpression causes replication stress.

a, b Statistical representation of velocity of progressing forks (a) and frequency distribution of fork speeds (b) was determined using DNA fiber analysis. Indicated immortalized MEFs were pulsed labeled with CldU (green) and IdU (red) for 20 min each and the fibers were imaged and quantified. Representative images of respective genotypes are shown on the right-hand panel. More than 500 fibers from each genotype were analyzed from two independent experiments with error bars in A representing the ±SD. Unpaired t test with and without Welch’s correction between two groups was used to determine the statistical P-value; < 0.0001 (****). c Representative images of immunofluorescence of EdU (S-phase cells) positivity (green) allowed to label for an hour alongside double-stranded DNA breaks marker γ-H2ax (red) observed in the immortalized MEFs (n = 150 cells were counted per experiment) of indicated genotypes are shown on the left-hand panel. DNA was marked using DAPI (blue). The statistical representation of the percentages of EdU positive cells; γ-H2ax in EdU positive or negative cells are demonstrated in the right-hand side panel. Error bars represent the ± SD from three independent experiments. Unpaired t test was performed to determine P-value < 0.0067 (**). d Immunoblot analysis of DNA damage response proteins from indicated immortalized MEFs after challenged with 6-Gy irradiation. β-Actin was used as loading control. e Immunoblot analysis of cytoplasmic-nuclear fractionation was performed using the indicated immortalized MEFs to determined Chk1 protein distributions with and without inhibitor treatments. Cells were treated for 6 h with inhibitors prior to the assay. H3 and Vincullin were used as fractionation loading controls for nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, respectively. f Quantification of replication fork speed observed in the immortalized Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs after being challenged with BEZ235 (pan-PI3K/AKT signaling pathways inhibitor), and AKTViii (was used to inhibit Akt signaling). Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs were pretreated for 6 h with indicated inhibitors and forks speeds were determined. At least 300 fibers from each genotype were analyzed from two independent experiments with error bars representing ±SD. One-way ANOVA with Brown-Forsythe test was used to determine P-value; < 0.0001 (****) and ns (not significant). g Distributions of replication fork speeds frequency from panel f. h Statistical representation of velocity of progressing forks as indicated in (a). Both cell lines were transiently transfected with 1.5 µg of indicated mutant constructs (CHK1 mutants -S280A and S280E, respectively, shown by western blotting (right)) for 24 h and DNA fiber analysis was performed. At least 300 fibers from each genotype were analyzed from three independent experiments with error bars representing ±SD. One-way ANOVA with Brown–Forsythe test was used to determine P-value < 0.0001 (****). β-Actin was used as a loading control in the Western blot.

Cep55 overexpression promotes structural and numerical CIN

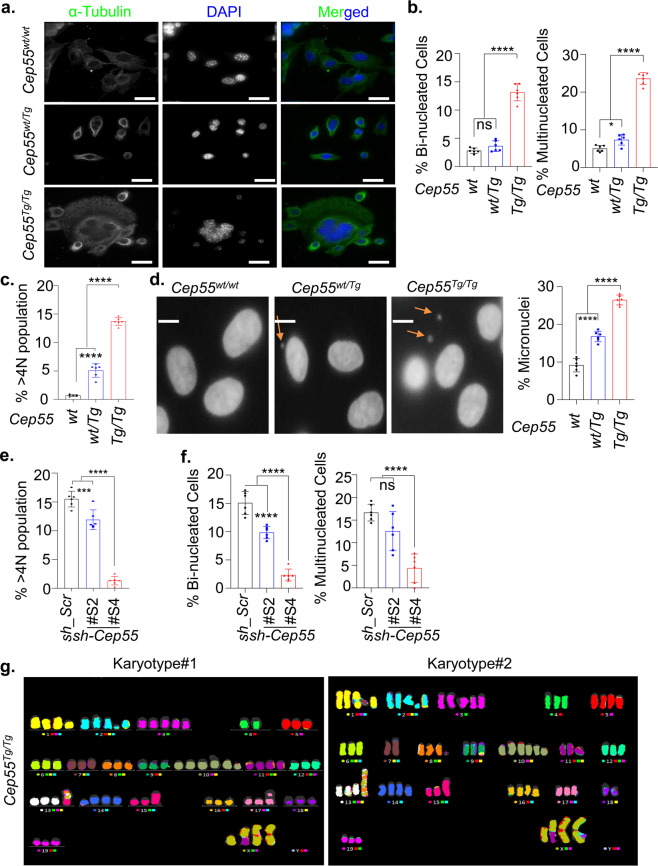

The well-known role of CEP55 as a regulator of CIN is through the regulation of cytokinesis3. Consistent with this, we found that whole-genome duplicated (WGD) tumors have significantly higher levels of CEP55 mRNA than diploid and near-diploid tumors (Supplementary Fig. 7A). Likewise, immortalized Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs exhibited a three-fold higher percentage (p < 0.0001) of binucleated and multinucleated cells (Fig. 5a, b). In addition, using FACS analysis, we found that both primary and immortalized Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs exhibited a significantly higher percentage of >4n subpopulation (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Fig. 7B). We also observed that compared to the primary Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs, the spontaneously immortalized Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs comprised significantly higher percentage (p < 0.01) of >4n subpopulation (Supplementary Fig. 7C). Similar results were observed in different organs isolated from Cep55Tg/Tg mice compared to their littermate counterparts (Supplementary Fig. 7D). Importantly, we found a significant increase in micronuclei in the Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs (p < 0.001) indicating the possible presence of CIN (Fig. 5d). Likewise, when Cep55 was constitutively knocked down in TCLs, we found a significant reduction in >4n subpopulations (Fig. 5e, f, Supplementary Fig. 7E), suggesting that Cep55 overexpression contributes to cancer cells ability to tolerate aneuploidy as reported previously by us for breast cancer cells18. Consistent with this, when we analyzed the level of aneuploidy across some of the human cancers using Genome-wide SNP6 array data from TCGA, we found that CEP55 overexpressing tumors show increased structural or numerical aneuploidy, including whole-chromosome aneuploidy and chromosome arm-level aneuploidy (Supplementary Fig. 8A–D). Additionally, spectral karyotyping of metaphase spreads from Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs demonstrated the presence of significantly higher levels of both numerical and structural chromosomal aberrations compared to other genotypes (Fig. 5g). Notably, these MEFs demonstrated complex chromosomal translocations and numerical abnormalities, whereas both Cep55wt/Tg and Cep55wt/wt MEFs showed a low level of structural and numerical chromosomal abnormalities (Table 2). In summary, these data highlight that Cep55 overexpression above a certain threshold is sufficient to promote structural and numerical CIN.

Fig. 5. Cep55 overexpression promotes chromosomal instability in vivo.

a Representative images of immunofluorescence demonstrating genomic instability observed in immortalized Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs, as indicated by the presence of multiple nuclei (marked by DAPI staining) compared to other counterparts. The cell cytoplasm is marked by α-tubulin (green) (Scale bar, 100 μm). b Quantification of the percentage of binucleated (left panel) and multinucleated cells (right panel) observed in the indicated immortalized MEFs (n = 100 cells were counted of each genotype). Error bars represent the ± SD from three independent experiments with two replicates each. One-way ANOVA test was performed to determine P-value; < 0.0001 (****) and ns (not significant). c Quantification of percentage of polyploidy cells (>4 N DNA content) determined using FACS analysis in the indicated immortalized MEFs. Error bars represent the ± SD from three independent experiments with two replicates each. One-way ANOVA test was performed to determine P-value; < 0.0001 (****). d Representative images showing the presence of micronuclei (marked by DAPI) in the indicated immortalized MEFs (left panel) (Scale bar, 100 μm). The micronuclei were counted manually per field of view/per nuclei, n = 300 cell were counted per experiment and the percentage of micronuclei observed in the indicated immortalized MEFs is shown in (right panel). Error bars represent the ± SD from three independent experiments with two replicates each. One-way ANOVA test was performed to determine P-value; < 0.0001 (****). e Percentage of polyploidy population (>4N DNA content) determined using FACS in the respective shCep55 depleted isogenic clones. Error bars represent the ± SD from three independent experiments with two replicates each. One-way ANOVA test was performed to determine P-value; < 0.001 (***) and < 0.0001 (****). f Quantification of the percentage of binucleated (left panel) and multinucleated cells (right panel) observed in the respective shCep55 depleted isogenic clones. Error bars represent the ± SD from three independent experiments with two replicates each (n = 100 cells per clone were counted). One-way ANOVA test was performed to determine P-value; < 0.0001 (****) and ns (not significant). g Representative metaphases from spectral karyotyping (SKY) in the Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs (passage 25) wherein #1 and #2 denotes biologically independent metaphase representation of immortalized Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs.

Table 2.

Changes in chromosomal alterations in Cep55 transgenic MEFs.

| Genotype | Karyotype | Phenotype |

|---|---|---|

| Cep55wt/wt | 77,XXXX,-6,-7,-18[17] | Hypotetraploid with numerical abnormalities. |

| Cep55wt/Tg | 80,XXXX[6]/77,idem,-6,-7,-18[11]/40,XX[4] | Four normal female metaphases. Six tetraploid metaphases and eleven hypotetraploid metaphases with the same numerical abnormalities that were seen in the WT cell line. |

| Cep55Tg/Tg | 72~74,X,der(X)t(X;11)(F?1;A?2),i(X)(A1)x2,del(1)(A?E?),del(2)(?B?H), + 3,-4,-6,-7,del(8)(A?2),-9,der(9)(9pter->9?F::2??2?F::1?H > 1qter)[3],der(9)t(9;17)(F?;E?1)[2],+10,+10,del(10)(A2B4)x3,-11,-12,der(13)(13pter->13?::8?->8?::13?->13?:: 8?->8?:: 13?->13qter)[12],der(13) (13pter->13?::8?->8?::13?->13?:: 8?->8?:: 13?->13?::5?->5qter)[2], | Hypotetraploid with complex numerical and structural abnormalities. |

| der(13) (13pter->13?::8?->8?::13?->13?:: 8?->8?:: 13?->13?::15?-> | ||

| 5qter)[3],der(13)t(13;14)(A?;B?)[2],-15,dup(15)(ED?2),-17,der(17) | ||

| t(9;17)(?F1;?B)[3],i(17)(A1),-18,-19[cp17] |

? = questionable identification of chromosome or chromosome structure.

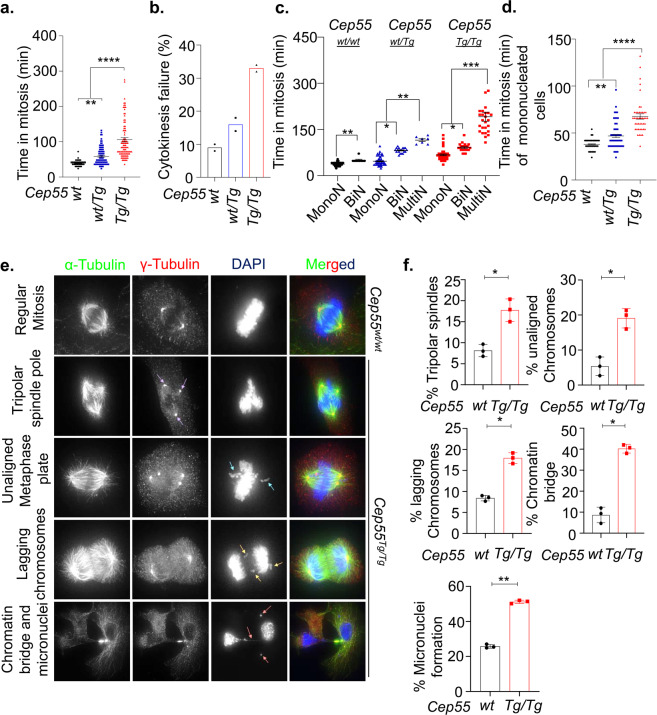

Cep55 overexpression delays mitotic exit

CIN in cancers primarily occurs due to defective mitosis including unequal chromosome segregation and failure to undergo cytokinesis. Our initial analysis of percentage of cells undergoing mitosis revealed that Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs had a significantly increased mitotic index compared to other genotypes (Supplementary Fig. 9A, B; p < 0.001) and Cep55-depleted TCLs showed a reduction in the number of mitotic cells (Supplementary Fig. 9C). We next asked how Cep55 overexpression might promote both structural and numerical CIN in these cells during normal and perturbed mitosis. To decipher this, we collected double-thymidine synchronized MEFs for DNA content and time-lapse live-cell imaging analyses. Notably, we observed that the Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs progressed faster through interphase and entered mitosis more rapidly compared to Cep55wt/wt MEFs (Supplementary Fig. 9D). However, the Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs spent a relatively longer time in mitosis with a higher percentage of cells exhibiting cytokinesis failure compared to wild-type and heterozygous MEFs (Fig. 6a, b). Likewise, the Cep55wt/Tg MEFs also spent significantly more time in mitosis compared to wild-type MEFs, indicating a dosage-dependent impact of Cep55 overexpression on mitotic duration (Fig. 6a). Multinucleated cells usually take more time to complete mitosis due to high DNA content and the Cep55wt/Tg and Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs exhibited mixed subpopulations of mononucleated, binucleated, and multinucleated cells (Fig. 5b, c and Supplementary Fig. 9E). We therefore performed analysis of individual subpopulations to determine the duration of mitosis (Fig. 6c). Surprisingly, along with the bi- and multinucleated Cep55Tg/Tg cells, the mononucleated cells also spent more time in mitosis, indicating that Cep55 overexpression prolonged mitotic duration independently of DNA content (Fig. 6d). Chromosome segregation errors are a major source for CIN27. Next, we investigated the impact of Cep55 overexpression on chromosome segregation using cells synchronized in mitosis. We observed a significantly higher frequency (p < 0.05) of multipolar spindle poles along with unaligned and lagging chromosomes in Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs compared to Cep55wt/wt MEFs (Fig. 6e, f, Supplementary Fig. 10A, B). In addition, using both fluorescence and live-cell time-lapse microscopy, we also observed that the Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs showed a significantly higher frequency of anaphase cells with chromatin bridges (anaphase bridges). The presence of anaphase bridges during mitosis indicates the presence of incompletely segregated DNA in Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs which in turn result in chromosomal breakage and micronuclei formation (Fig. 6f). Consistent with this, we observed that the Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs exhibited an increased proportion (p < 0.001) of micronuclei, a morphological characteristic of CIN, when compared to control MEFs (Fig. 6f).

Fig. 6. Impact of Cep55 overexpression on mitosis.

a Quantification of the average time spent in mitosis by the immortalized MEFs of indicated genotypes. MEFs were synchronized using double‐thymidine and released into regular media. Individual cells were tracked using bright-field Olympus Xcellence IX81 time-lapse microscopy for overall time taken to complete mitosis from nuclear envelope breakdown up to daughter cell formation18. At least 50 cells were counted per experiment. Error bars represent the ± SD from two independent experiments with three replicates each. One-way ANOVA test was performed to determine P-value; < 0.01 (**) and < 0.0001 (****). b Boxplots showing the percentage of cytokinesis failure observed in the immortalized MEFs of indicated genotypes. Data derived from experiment (a). Percentage was derived from 50 cells per experiment. c Quantification of average time spent in mitosis by different cell populations observed among the immortalized MEFs of indicated genotypes. At least 100 cells were counted. Error bars represent the ± SD from two independent experiments with three replicates each. Two-way ANOVA test was performed to determine P-value < 0.05 (*), < 0.01 (**) and < 0.001 (***). d Quantification of average time spent in mitosis by immortalized mononucleated MEFs of indicated genotypes. Error bars represent the ± SD from two independent experiments as described above. One-way ANOVA test was performed to determine P-value < 0.01 (**) and < 0.0001 (****). e Representative images of immunofluorescence (Scale bar, 100 μm) and (f) statistical analyses of the mitotic defects observed in the immortalized Cep55wt/wt and Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs as indicated by the presence of tripolar spindle poles, unaligned metaphase plates, lagging chromosomes, as well as chromatin bridges and micronuclei. The arrows represent the different mitotic phenotype observed across immortalized Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs. The blue arrow represents unaligned chromosomes, the yellow arrows represent presence of lagging chromosomes, the purple arrows represent tripolar spindle and orange arrows represent the presence of chromatin bridge and micronuclei. Error bars represent the ± SD from two independent experiments with three replicates each. n = 50 mitotic cells were counted per experiment. Student’s t test was performed to determine P-value; < 0.05 (*) and < 0.01 (**).

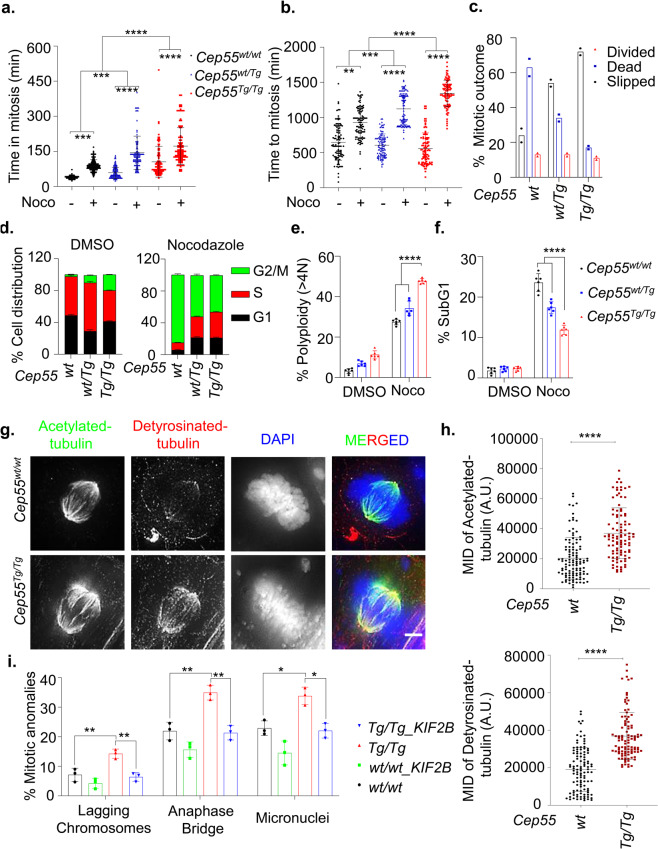

Cep55 overexpression stabilizes microtubules

We recently reported that CEP55 overexpression causes premature exit during perturbed mitosis and is determinant of aneuploid breast cancer cell survival18. Consistent with our previous observation, Cep55 overexpression significantly impacted the duration of time to- and time spent in mitosis upon nocodazole treatment (Fig. 7a, b). In particular, the Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs largely prematurely exited mitosis during nocodazole arrest but the Cep55wt/wt MEFs predominately died in mitosis, despite an increase in expression of components of spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) proteins, Bubr1 and Mad2 levels in Cep55Tg/Tg compared to Cep55wt/wt MEFs (Fig. 7c–f, Supplementary Fig. 11A). Additionally, we found that SAC activity was not impaired after nocodazole treatment (4 h), as assessed by assembly of SAC protein complex (Cdc20. Bubr1 and Mad2) (Supplementary Fig. 11B). In contrast, the Cep55-depleted TCL showed sensitivity towards nocodazole treatment with a significant reduction in premature exit and increase in apoptosis (Supplementary Fig. 11C–E). Therefore, these data indicate that Cep55 overexpression facilitates mitotic slippage rather than death in response to anti-mitotic poisons irrespective of normal activation of SAC. This is consistent with our previous study wherein we showed that CEP55 overexpression confers resistance to anti-mitotic poisons despite prolonged activation of SAC through the inability of cells to breach apoptotic threshold18.

Fig. 7. Association of CEP55 with microtubule stability.

a, b Comparison of average time spent in mitosis (a) and average time taken to complete mitosis (b) determined using time-lapse microscopy of the immortalized MEFs of indicated genotypes in the presence and absence of nocodazole (0.5 μM). Error bars represent the ± SD from two independent experiments (fate of n = 50 cell were counted per experiment). Student’s t test was performed to determine P-value < 0.05 (*), < 0.01 (**), < 0.001 (***) and < 0.0001 (****). c Percentage of mitotic outcome of the immortalized MEFs of indicated genotypes in presence of nocodazole (0.5 μM) as shown in panel A and B. Mitotic slippage was defined by premature mitotic exit during nocodazole-induced mitotic arrest, while death was determined through membrane blebbing. Mean derived from two independent experiments (fate of n = 50 cell were counted per experiment). d Cell-cycle profiles of immortalized MEFs of indicated genotype in the presence or absence of nocodazole (0.5 μM) determined using FACS. Error bars represent the ± SD from three independent experiments. Two-way ANOVA test was performed to determine P-value as demonstrated in Supplementary Table 3. e, f Polyploidy (>4N DNA content) (e) and percentage of SubG1 populations (f) determined using FACS in the indicated immortalized MEFs in the presence or absence of nocodazole (0.5 μM). Error bars represent the ± SD from three independent experiments with two replicates each. One-way ANOVA test was performed to determine P-value < 0.0001 (****). g Representative images of detryosinated (red) and acetylated tubulin (green) of metaphase stages of immortalized Cep55wt/wt and Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs showing the microtubule networks (Scale bar, 100 μm). h Quantification of the mean integrated density (MID) of Acetylated (Upper panel) and detyrosinated (lower panel) tubulin observed among immortalized Cep55wt/wt and Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs. The intensity was calculated using Image J software wherein n = 50 metaphase cells were calculated per genotype. Error bars represent the ± SD from two independent experiments. Student’s t test was performed to determine P-value < 0.0001 (****). i Percentage of mitotic defects (described previously in Fig. 6f upon KIF2B overexpression in the immortalized MEFs (n = 100 cell per experiment were counted) of indicated genotypes. Error bars represent the ± SD from three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA test was performed to determine P-value < 0.05 (*) and < 0.01 (**).

Increased kinetochore-microtubule (k-MT) stability causes incomplete segregation of DNA, including lagging chromosomes during anaphase28,29. As CEP55 is recruited to spindle microtubules during mitosis3 and efficiently bundles microtubules30, we asked if Cep55 overexpression stabilizes microtubules, and hence increasing segregation errors during mitosis. To analyze spindle microtubule stability, mitotic cells were stained with antibodies that recognize stable detyrosinated- and acetylated-microtubules. Cep55Tg/Tg mitotic cells exhibited enhanced detyrosinated- and acetylated- microtubule staining compared to mitotic Cep55wt/wt cells, indicating these cells have stabilized microtubules in metaphase or midbodies (Fig. 7g, h, Supplementary Fig. 11F). Next, to confirm that increased chromosome segregation errors, including lagging chromosomes, in response to Cep55 overexpression are due to stabilized microtubules, we expressed GFP-tagged KIF2B, microtubule depolymerizing kinesin-13 protein, in both Cep55Tg/Tg and Cep55wt/wt MEFs. In particular, exogenous expression of KIF2B in Cep55Tg/Tg cells significantly reduced the frequencies of lagging chromosomes, anaphase bridges, and micronuclei (Fig. 7i), Likewise, treatment of these cells with low concentration of nocodazole at 10 nM significantly reduced percentage of lagging and unaligned chromosomes with increase in normal mitosis (Supplementary Fig. 11F, G). Collectively, our data suggest that overexpression of Cep55 stabilizes microtubules that in part lead to the mitotic defects observed in these MEFs.

Discussion

We have previously reported a Cep55-overexpression mouse model that exhibits male-specific sterility by suppressing Foxo1 nuclear retention through hyperactivation of Pi3k/Akt signaling17. In this study, using the same mouse model, to the best of our knowledge we demonstrate for the first time that Cep55 overexpression causes spontaneous tumorigenesis. Our data highlight the dosage-dependent impact of Cep55 overexpression on cell proliferation and tumorigenesis in vivo. The homozygous Cep55Tg/Tg mice are prone to develop a wide spectrum of tumors (both solid and hematological origin) with a high incidence rate and high metastatic potential. Interestingly, heterozygous Cep55wt/Tg mice developed a lower percentage of adenomas (~20%) and hyperplasia (~8%), suggesting that single copy overexpression of Cep55 is sufficient to initiate tumorigenesis, although the latency significantly differs between Cep55Tg/Tg and Cep55wt/Tg mice. Notably, the Cep55Tg/Tg mice demonstrated a higher incidence of lymphomas and sarcomas compared to other types of malignancies, mimicking the phenotype observed in Trp53−/− mice. As p53 negatively controls CEP55 expression13, using a bi-transgenic mouse model, we also demonstrated that single copy loss of p53 (Trp53+/−) accelerates heterozygous Cep55wt/Tg -induced tumorigenesis. Interestingly, these data also illustrate that either loss or mutation of Trp53 might be an early event and a critical secondary hit is required for tumor initiation observed in the homozygous Cep55Tg/Tg mice. Consistent with this, we observed high p53 protein levels, which are most likely an indication of mutated Trp53, in representative Cep55Tg/Tg tumor tissues than normal adjacent tissues. Notably, partial depletion of Cep55 (50%) in TCLs significantly delayed tumor initiation and progression, while near-complete depletion (90%) totally impaired tumor initiation in a xenograft model.

As Cep55 has been linked with GI and its overexpression causes a wide range of tumors in vivo, we further characterized GI in Cep55-overexpressing cells. Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs exhibited a high level of cytokinesis failure accompanied by genome doubling. Importantly the Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs showed high level of numerical and structural CIN compared to MEFs of other genotypes. Importantly, in this study, we showed that Cep55 overexpression causes mitotic defects including a high frequency of chromatin bridge and micronuclei formation during anaphase. As CEP55 is a microtubule-bundling protein30, missegregation of chromosomes upon Cep55 overexpression might be indicative of kinetochore-microtubule (k-MT) hyper-stability. Consistent with this notion, we found that overexpression of Cep55 stabilized microtubules and predisposed cells to CIN. Notably, reducing microtubule stability by forced expression of KIF2B in Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs significantly reduced lagging chromosomes. The influence of Cep55 overexpression on sister chromatid segregation errors accompanied by cytokinesis failure explains the delayed mitotic exit observed in the Cep55-overexpressing cells. Taken together, our data suggest that hyperstabilised microtubules and defective cytokinesis in Cep55-overexpressing cells might be major source of chromosome segregation errors and tetraploidization that can predispose these cells to GI which over time might facilitate tumor development.

Consistent with previous reports (reviewed by Jeffery et al.4.), Cep55 overexpression led to rapid proliferation. We observed that the Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs displayed hyper-phosphorylated Akt and deregulated downstream Pi3k/ Akt signaling such as Gsk-3β, Myc, and β-Catenin which might be a further source of GI in these cells. Akt hyperactivation is known to result in cytoplasmic sequestration of Chk1, this might result in a compromised S-phase checkpoint that increases replication fork progression in Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs to allow uncontrolled cell cycle progression and consequently promote GI. Consistent with this, overexpression of CHK1 mutant (S280A), that cannot be phosphorylated by overactive AKT, in Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs or their treatment with Pi3k/Akt pathway inhibitors resulted in reduced fork progression. Furthermore, loss of Chk1 function has also been shown to induce chromosomal segregation errors and chromatin bridges during anaphase resulting in CIN26,31, resembling the phenotype we observe.

Deregulation of mitotic proteins has long been known to contribute to early cellular transformation and tumorigenesis32 though they are rarely mutated in cancer33,34, but rather prone to amplification. Abnormal expression (loss or gain) of critical mitotic proteins, especially those included in the CIN70 gene signature, such as MAD235, BUB136, AURKA37, EMI138, PLK139,40, TTK141 and many more, at the genetic level have been shown to induce spontaneous tumorigenesis. The major phenotype observed in these mouse models was defective chromosomal segregation during anaphase which led to CIN and genomically unstable malignancies, similar to the phenotype observed in our model. Thus, the interplay of these mitotic genes with Cep55 overexpression needs further evaluation. Importantly, in our previous study in breast cancer, we have shown that CEP55 overexpression protects aneuploid cells during perturbed mitosis17. We have demonstrated that high level of CEP55 significantly induced mitotic slippage in TNBCs as loss of CEP55 enables mitotic cell death by enabling premature mitotic entry upon being challenged with anti-mitotic drugs. Consistently, herein we have demonstrated that Cep55 is a protector of aneuploidy during aberrant mitosis as the aneuploid Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs underwent mitotic slippage in response to anti-mitotic drugs and survived mitotic cell death. It also explains the ability of the highly polyploid Cep55Tg/Tg MEFs to re-enter mitosis and continue proliferation as CEP55 overexpression allows high tolerance and better survival of these cell populations.

A recent report has suggested that cells procure specific genomic alterations, mainly impacting the regular function of mitotic genes prior to malignant transformation42. CEP55 overexpression has been linked with tumorigenesis for a wide variety of cancers. However, this is the first report to our knowledge demonstrating that overexpression of Cep55 has a causative role in tumorigenesis. Our data clearly demonstrate that Cep55 overexpression beyond a critical level is self-sufficient to induce a wide spectrum of spontaneous tumors. Importantly, we have shown that Cep55 overexpression leads to the induction of pleotropic events such as Pi3k/Akt pathway activation, Chk1 sequestration compromising the replication checkpoint, and stabilized microtubules along with chromosomal segregation anomalies which all together cause CIN. Accumulation of these anomalies over time might induce tumourigenesis. In summary, our mouse model could be a valuable tool in studying the mechanism of CIN-associated tumorigenesis and development of CIN-targeting therapies.

Methods

Reagents

Nocodozole, BEZ235, BKM120, AZD6244 and AKTViii were purchased from Selleck Chemicals LCC. Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were from Shanghai Gene Pharma. Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Media (DMEM), Click-iT Alexa Fluor 488 EdU (5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine) imaging kit and Lipofectamine RNAiMAX was purchased from Life Technologies. Foetal Bovine Serum (FBS) was purchased from SAFC Biosciences™, Lenexa, USA. CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay and Dual-Glo® Luciferase Assay were purchased from Promega Corporation.

Animal husbandry and ethics statement

All animal work was approved by the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, Animal Ethics Committee (number A0707-606M) and was performed in strict accordance with the Australian code for the care and use of animals for scientific purposes. The animals were maintained as per the guidelines17.

Histopathological analysis and immunohistochemistry

For histologic examination, tissues were collected and fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS as per the standard protocol described by Sinha et al.17. Briefly, the tissues were embedded in paraffin blocks, and 5-μm-thick sections prepared for respective stains after being fixed in 4% formaldehyde. Immunostaining was performed with the following primary antibodies: Ki67 1:500 (anti-rabbit, Novacastra #NCL-ki67p), B220 1:500 (anti-rat, ThermoFischer Scientific #14-0452-82), CD3 1:250 (anti-rabbit, Abcam #ab5690), p21 1:500 (anti-rabbit, Abcam #ab188224), p53 1:400 (anti-rabbit, Abcam #ab131442).

Cell culture and synchronization

To generate the MEFs, mice pregnancy was accessed on the basis of a copulation plug on the following morning post-mating date, designated as embryonic day. Such assessment was done for isolating MEFs on E13.5 and single-cell isolation was performed using the standard protocol43. Continuous passaging every 48 h in culture immortalized the MEFs of each genotype. To generate the primary tumor lines (TCLs), tumor was surgically removed followed by mechanical disaggregation using a sterile scalpel blade and then incubation in 0.1% collagenase (Sigma Aldrich) in 10 mL of DMEM containing 20% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (100 U/mL), 1% L-glutamine and cultured in a 25 cm2 tissue flasks. After 24 h, the cells were trypsinized and cultured in a new 25 cm2 tissue flask with media supplemented with 100 µL (100 µg/mL) of EGF, 500 µL (10 mg/mL) of insulin and 1% Sodium pyruvate (Life TechnologyTM. The culture of the murine cell lines was maintained by incubating at 37 °C with 20% oxygen levels and 5% CO2. Cells were synchronized at G1/S by double-thymidine block44.

Genotype analysis and quantitative real-time PCR

Genotyping, RNA extraction, and quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the primer sets used in these assays were used as per standard protocol17. Briefly, total RNA from respective cells of each genotype was isolated using an RNeasy plus mini kit (Qiagen). 2 μg of RNA was used for first-stand cDNA synthesis using random primers (Life Technologies) and Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies). qRT-PCR was performed using Light Cycler 480 Sybr green mastermix (Roche Applied Science) on a Light Cycler 480 real-time PCR cycler (Roche Applied Science).

Immunoblotting and Immunoprecipitation

The protein extraction from cell lysate or tissue lysate was prepared in urea lysis buffer (8 M urea, 1% SDS, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and incubated for 30 min on ice after which the samples were sonicated for 10 seconds. Western blotting was performed as per the standard protocol and some of the antibodies used for immunoblotting17. The following are additional antibodies used in this study: Cell Signaling antibodies: PARP (#9542), pAKTS473 (#4060), AKT (#9272), pPdk1S241 (#3061), Pdk1(#3062) Chk1 (2G1D5) (#2360), p-GSK-3β(Ser9) (#9336), GSK-3β (#9315), p-Histone H3 (#9706) (1:1000 dilution); Millipore antibody: Chk2 (1:500 dilution) (Clone 7) (05-649), γ-H2ax (1:1000 dilution) S139 (05-636); BD Pharmingen antibody: β-actin (1:2000 dilution) (612656); Bethyl antibody: pKap1(S824) (1:1000 dilution) (A300-767A). Immunoprecipitation was performed as per our previous publication45. Immunodetections were performed using Bubr1 (ab4637), Mad2 (CST4636S) and CDC20 (CST14866A).

Cell proliferation assay

The cell proliferation assay using The IncuCyte® S3 Live-Cell Analysis system (Essen BioSciences Inc, USA), as described by Kalimutho et al.18. Doubling time was analyzed at every 12 h interval by counting the overall cell population compared to the originally seeded population using the Countess® automated cell counter (Life TechnologiesTM). The NIH-3T3 proliferation assay was performed by using the standard protocol43.

Colony formation assays

Five hundred to one thousand cells were seeded on 12 well plates and incubated for additional 14 days to determine colony viability. The colonies were fixed with 0.05% crystal violet for 30 min18.

Flow cytometry and cell cycle analysis

Cell-cycle perturbations and the subG1 apoptotic fractions were determined using flow cytometry analysis of cells stained with propidium iodide and analyzed using the ModFit LT 4.0 software18.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were seeded and incubated overnight on coverslips and were fixed for 15 min in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, permeabilized in 0.5% Triton X-100-PBS for 15 min and blocked in 3% filtered bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS. Coverslips with primary antibodies were diluted in blocking solution and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Alexafluor conjugated secondary antibodies were diluted 1:300 and DAPI (diluted 1:500 in blocking buffer, stock 1 mg/ml), in blocking solution and stained for 45 min at 37 oC in humidifier chamber. Slides were washed thrice with 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS and mounted in Prolong Gold. Slides were imaged using GE DeltaVision Deconvolution microscope and analyzed using Image J. Antibodies used for immunofluorescence were: γ-H2ax S139 (05-636; Millipore), p-Histone H3 (#9706; CST), α-Tubulin (T9026), γ-Tubulin (T5192), Acetylated tubulin (T7451; Sigma) and detyrosinated tubulin (ab48389; Abcam).

DNA combing assay

The DNA fiber protocol was followed as described previously by us and others46,47. Briefly, cells were pulse-labeled with CldU and IdU for 20 min each. Progressive replication fork speed was calculated based on the length of the IdU (red) tracks measured using ImageJ software. At least 300 replication tracks were analyzed for each sample in two independent experiments. The fork speed was calculated based on conversion factor 1 µm = 2.59 kb48.

Gene silencing

Transient gene silencing was performed by reverse transfection using 10 nM of respective small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). The sequences involved Cep55_Scr (5′CAAUGUUGAUUUGGUGUCUGCA3′); Cep55_SEQ1 (5′ CCAUCACAGAGCAGCCAUUCCCACT 3′) and Cep55_SEQ2-targeting UTR (5′ AGCUACUGAGCAGUAAGCAAACAUU). The siRNAs were manufactured by Shanghai Gene Pharma. The transfection was performed using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Life TechnologiesTM). Mouse small hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) for Cep55 (pLKO plasmids, (Sigma Aldrich®, St Louis, USA)) clones were established using lentiviral packaging using PEI (Poly -ethyleneimine) solution (Sigma Aldrich®, St Louis, USA).

Cep55_Scr

(5′CCGGCGCTGTTCTAATGACTAGCATCTCGAGATGCTAGTCATTAGAACAGCGTTTTTT′3);

Cep55_sh#1: TRCN0000366894 CDS

(5′CCGGCCGTGACTCAGTTGCGTTTAGCTCGAGCTAAACGCAACTGAGTCACGGTTTTTG);

Cep55_sh#2 TRCN0000366948 CDS

(5′CCGGCAGCGAGAGGCCTACGTTAAACTCGAGTTTAACGTAGGCCTCTCGCTGTTTTTG3′);

Cep55_sh#3 TRCN0000183083 CDS

(5′CCGGCGTTTAGAACTCGATGAATTTCTCGAGAAATTCATCGAGTTCTAAACGTTTTTTG3′);

Cep55_sh#4 TRCN0000183560 CDS

(5′CCGGGAAGATTGAATCAGAAGGTTACTCGAGTAACCTTCTGATTCAATCTTCTTTTTTG3′).

Live cell imaging

Live cell imaging for double thymidine releases was performed on an Olympus IX81 microscope using excellence rt v2.0 software. Images were analyzed using analySIS LS Research, version 2.2 (Applied Precision)49. Live cell imaging for tracking mitotic defects was performed in H2B Cherry transfected MEFs of each genotype using 20X Andor Revolution WD - Spinning Disk microscope.

In vivo xenografts

All mice were housed in standard condition with a 12 h light/dark cycle and free access to food and water. 2.5 × 106 TLC were prepared in 50% matrigel (BD, Biosciences, Bedford, USA)/PBS and injected subcutaneously injected into the right flank of 6-week-old NOD/SCID mice18.

Bioinformatics analysis

Whole-chromosome (WC) and chromosome arm-level (CAL) somatic copy number aberrations (SCNAs) were inferred from TCGA processed (Level 3) Affymetrix Genome Wide SNP6.0 Array data for the indicated cancer types, as previously described50. Using the same datasets, ASCAT2.451 was used to compute the ploidy level for each sample. Samples with ploidy between 1.9 and 2.1 were considered diploid, samples with ploidy lower than 1.9 or between 2.1 and 2.5 were called near-diploid aneuploid and samples with ploidy>2.5 were considered aneuploid and having undergone at least one whole-genome doubling (WGD)52,53.

Statistics and reproducibility

Student’s t test; one-way or two-way ANOVA; RPKM and RSEM with Bonferoni post hoc or Mann-Whitney U test testing (specified in figure legend) and Fisher exact test was performed using GRAPHPAD PRISM v6.0 (GraphPAd Software, LaJolla, CA, USA) and the p-values were calculated as indicated in figure legends. Asterisks indicate significant difference (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001), ns = not significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the members of the Khanna laboratory for technical assistance, Stephen Miles for maintaining cell lines, QIMR Berghofer Flow Cytometry and Animal facility staff, Nigel Waterhouse and Tam Hong Nguyen from ACRF Imaging Centre for microscopic assistance, and Paul Collins for STR profiling and Mycoplasma testing. We thank Dr. Hiroyuki Niida from Hamamatsu University School of Medicine for providing mutant CHK1 constructs. We thank Griffith University as DS was supported by Griffith University International Postgraduate Research Scholarship (GUIPRS) and Griffith University Postgraduate Research Scholarship (GUPRS). KK lab is supported by National Health & Medical Research Council (NH&MRC) Program Grant [ID 1017028].

Author contributions

Conceptualization, D.S., M.K., and K.K.K.; Investigation and data analysis, D.S., P.N. D.N., A.B., P.R., V.A.J.S., A.L.B., G.S., M.W., J.W.F., and M.K.; Bioinformatics, P.H.G.D.; Writing–Original Draft, D.S., M.K., and K.K.K.; Writing–Review & Editing, all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files) and all the raw data available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Source data can be found in Supplementary Data 1.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Murugan Kalimutho, Kum Kum Khanna.

Contributor Information

Murugan Kalimutho, Email: Murugan.Kalimutho@qimrberghofer.edu.au.

Kum Kum Khanna, Email: KumKum.Khanna@qimrberghofer.edu.au.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s42003-020-01304-6.

References

- 1.Zahreddine H, Borden KL. Mechanisms and insights into drug resistance in cancer. Front Pharm. 2013;4:28. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perez de Castro I, de Carcer G, Malumbres M. A census of mitotic cancer genes: new insights into tumor cell biology and cancer therapy. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:899–912. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fabbro M, et al. Cdk1/Erk2- and Plk1-dependent phosphorylation of a centrosome protein, Cep55, is required for its recruitment to midbody and cytokinesis. Dev. Cell. 2005;9:477–488. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeffery J, Sinha D, Srihari S, Kalimutho M, Khanna KK. Beyond cytokinesis: the emerging roles of CEP55 in tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2016;35:683–690. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frosk P, et al. A truncating mutation in CEP55 is the likely cause of MARCH, a novel syndrome affecting neuronal mitosis. J. Med. Genet. 2017;54:490–501. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-104296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bondeson ML, et al. A nonsense mutation in CEP55 defines a new locus for a Meckel-like syndrome, an autosomal recessive lethal fetal ciliopathy. Clin. Genet. 2017;92:510–516. doi: 10.1111/cge.13012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rawlins, L. E. et al. An Amish founder variant consolidates disruption of CEP55 as a cause of hydranencephaly and renal dysplasia. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Jeffery J, et al. Cep55 regulates embryonic growth and development by promoting Akt stability in zebrafish. FASEB J. 2015;29:1999–2009. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-265090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter SL, Eklund AC, Kohane IS, Harris LN, Szallasi Z. A signature of chromosomal instability inferred from gene expression profiles predicts clinical outcome in multiple human cancers. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:1043–1048. doi: 10.1038/ng1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou W, et al. NEK2 induces drug resistance mainly through activation of efflux drug pumps and is associated with poor prognosis in myeloma and other cancers. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:48–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuzick J, et al. Prognostic value of an RNA expression signature derived from cell cycle proliferation genes in patients with prostate cancer: a retrospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:245–255. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70295-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Ejeh F, et al. Meta-analysis of the global gene expression profile of triple-negative breast cancer identifies genes for the prognostication and treatment of aggressive breast cancer. Oncogenesis. 2014;3:e100. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2014.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang YC, Wu CH, Yen TC, Ouyang P. Centrosomal protein 55 (Cep55) stability is negatively regulated by p53 protein through Polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:4376–4385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.289108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen CH, et al. FLJ10540-elicited cell transformation is through the activation of PI3-kinase/AKT pathway. Oncogene. 2007;26:4272–4283. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen CH, et al. VEGFA upregulates FLJ10540 and modulates migration and invasion of lung cancer via PI3K/AKT pathway. PloS ONE. 2009;4:e5052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li, M., Gao, J., Li, D. & Yin, Y. CEP55 Promotes Cell Motility via JAK2(-)STAT3(-)MMPs Cascade in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cells7, 99 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Sinha D, et al. Cep55 overexpression causes male-specific sterility in mice by suppressing Foxo1 nuclear retention through sustained activation of PI3K/Akt signaling. FASEB J. 2018;32:4984–4999. doi: 10.1096/fj.201701096RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalimutho, M. et al. CEP55 is a determinant of cell fate during perturbed mitosis in breast cancer. EMBO Mol. Med.10, e8566 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Zhou, C., Hancock, J. L., Khanna, K. K. & Homer, H. A. First meiotic anaphase requires Cep55-dependent inhibitory cyclin-dependent kinase 1 phosphorylation. J. Cell Sci. 132 jcs233379 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Jackson EL, et al. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3243–3248. doi: 10.1101/gad.943001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Podsypanina K, et al. Mutation of Pten/Mmac1 in mice causes neoplasia in multiple organ systems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:1563–1568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donehower LA, et al. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature. 1992;356:215–221. doi: 10.1038/356215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olive KP, et al. Mutant p53 gain of function in two mouse models of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Cell. 2004;119:847–860. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puc J, et al. Lack of PTEN sequesters CHK1 and initiates genetic instability. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:193–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maya-Mendoza A, et al. High speed of fork progression induces DNA replication stress and genomic instability. Nature. 2018;559:279–284. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kabeche L, Nguyen HD, Buisson R, Zou L. A mitosis-specific and R loop-driven ATR pathway promotes faithful chromosome segregation. Science. 2018;359:108–114. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JK, Choi YL, Kwon M, Park PJ. Mechanisms and Consequences of Cancer Genome Instability: Lessons from Genome Sequencing Studies. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2016;11:283–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012615-044446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bakhoum SF, Kabeche L, Murnane JP, Zaki BI, Compton DA. DNA-damage response during mitosis induces whole-chromosome missegregation. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:1281–1289. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson SL, Compton DA. Chromosome missegregation in human cells arises through specific types of kinetochore-microtubule attachment errors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:17974–17978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109720108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao WM, Seki A, Fang G. Cep55, a microtubule-bundling protein, associates with centralspindlin to control the midbody integrity and cell abscission during cytokinesis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:3881–3896. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e06-01-0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petermann E, Woodcock M, Helleday T. Chk1 promotes replication fork progression by controlling replication initiation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:16090–16095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005031107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kops GJ, Weaver BA, Cleveland DW. On the road to cancer: aneuploidy and the mitotic checkpoint. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:773–785. doi: 10.1038/nrc1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cahill DP, et al. Characterization of MAD2B and other mitotic spindle checkpoint genes. Genomics. 1999;58:181–187. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hernando E, et al. Molecular analyses of the mitotic checkpoint components hsMAD2, hBUB1 and hBUB3 in human cancer. Int J. Cancer. 2001;95:223–227. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20010720)95:4<223::AID-IJC1038>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sotillo R, et al. Mad2 overexpression promotes aneuploidy and tumorigenesis in mice. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:9–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ricke RM, Jeganathan KB, van Deursen JM. Bub1 overexpression induces aneuploidy and tumor formation through Aurora B kinase hyperactivation. J. Cell Biol. 2011;193:1049–1064. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201012035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fu J, Bian M, Jiang Q, Zhang C. Roles of Aurora kinases in mitosis and tumorigenesis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2007;5:1–10. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaidyanathan S, et al. In vivo overexpression of Emi1 promotes chromosome instability and tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2016;35:5446–5455. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weichert W, et al. Overexpression of Polo-like kinase 1 is a common and early event in pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology. 2005;5:259–265. doi: 10.1159/000085280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ito Y, et al. Polo-like kinase 1 overexpression is an early event in the progression of papillary carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer. 2004;90:414–418. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foijer F, et al. Chromosome instability induced by Mps1 and p53 mutation generates aggressive lymphomas exhibiting aneuploidy-induced stress. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:13427–13432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400892111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manning AL, Benes C, Dyson NJ. Whole chromosome instability resulting from the synergistic effects of pRB and p53 inactivation. Oncogene. 2014;33:2487–2494. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi W, et al. Essential developmental, genomic stability, and tumour suppressor functions of the mouse orthologue of hSSB1/NABP2. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jeffery JM, Urquhart AJ, Subramaniam VN, Parton RG, Khanna KK. Centrobin regulates the assembly of functional mitotic spindles. Oncogene. 2010;29:2649–2658. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kalimutho M, et al. Blockade of PDGFRbeta circumvents resistance to MEK-JAK inhibition via intratumoral CD8(+) T-cells infiltration in triple-negative breast cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;38:85. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1075-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwab, R. A. & Niedzwiedz, W. Visualization of DNA replication in the vertebrate model system DT40 using the DNA fiber technique. J. Vis. Exp.56, e3255 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Kalimutho M, et al. Enhanced dependency of KRAS-mutant colorectal cancer cells on RAD51-dependent homologous recombination repair identified from genetic interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Oncol. 2017;11:470–490. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Henry-Mowatt J, et al. XRCC3 and Rad51 modulate replication fork progression on damaged vertebrate chromosomes. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:1109–1117. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jeffery JM, et al. Centrobin regulates centrosome function in interphase cells by limiting pericentriolar matrix recruitment. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:899–906. doi: 10.4161/cc.23879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]