Abstract

The neural circuits regulating motivation and movement include midbrain dopaminergic neurons and associated inhibitory GABAergic and excitatory glutamatergic neurons in the anterior brainstem. Differentiation of specific subtypes of GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons in the mouse embryonic brainstem is controlled by a transcription factor Tal1. This study characterizes the behavioral and neurochemical changes caused by the absence of Tal1 function. The Tal1cko mutant mice are hyperactive, impulsive, hypersensitive to reward, have learning deficits and a habituation defect in a novel environment. Only minor changes in their dopaminergic system were detected. Amphetamine induced striatal dopamine release and amphetamine induced place preference were normal in Tal1cko mice. Increased dopamine signaling failed to stimulate the locomotor activity of the Tal1cko mice, but instead alleviated their hyperactivity. Altogether, the Tal1cko mice recapitulate many features of the attention and hyperactivity disorders, suggesting a role for Tal1 regulated developmental pathways and neural structures in the control of motivation and movement.

Subject terms: ADHD, Molecular neuroscience

Introduction

Brain functions behind movement, motivated behavior, attention, impulse control, and learning are regulated by neurons in the anterior brainstem. Extensive research has shown the roles of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) and in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) in these behaviors1,2. Altered dopaminergic neurotransmission has also been implicated as one of the mechanisms of hyperactivity disorders, including attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)2. Furthermore, the symptoms of ADHD are alleviated by drugs that evoke dopamine release, such as amphetamine.

Dopamine neurons receive both excitatory and inhibitory input from diverse brain regions. These regulatory neurons include GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons in the dopaminergic nuclei or in their vicinity, in particular in the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNpr), ventral tegmental area (VTA), rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg), and laterodorsal tegmental nucleus (LDTg)3,4. Importantly, the inhibitory GABAergic and excitatory glutamatergic neurons in these nuclei not only regulate the dopaminergic neurons but also project to other brain structures. For example, the VTA GABAergic neuron projections to the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and the nucleus accumbens (NAc) are important for arousal and assessment of reward5,6, the SNpr GABAergic neuron projections to the superior colliculus and the thalamus provide the main output of the basal ganglia network regulating voluntary movement7, and the RMTg regulates both the dopaminergic and serotonergic systems, which have also been implicated in regulation of impulsivity8.

Most of the GABAergic neurons in the midbrain dopaminergic nuclei share developmental origins and regulatory mechanisms, which differ from the rest of the midbrain GABAergic neurons9,10. These neurons are born in a specific domain of the ventral rhombomere 1 of the hindbrain, where their differentiation depends on a transcription factor Tal110. In this region of the brain, Tal1 functions as a cell fate selector gene promoting GABAergic differentiation at the expense of the alternative glutamatergic neuron identities10. In conditional Tal1 mutant mice, where the Tal1 gene is inactivated in the midbrain and rhombomere 1 (En1Cre; Tal1flox/flox; Tal1cko), all GABAergic neurons in the RMTg, VTA and most of the neurons in the posterior part of the SNpr fail to develop. In contrast to the posterior SNpr, the anterior SNpr, not derived from the rhombomere 1, as well as other midbrain GABAergic neurons are intact in the Tal1cko mice. In addition to the GABAergic neurons associated with the dopaminergic nuclei in the ventral midbrain, the Tal1cko mice lack specific brainstem GABAergic neuron subgroups, including the neurons of the ventral tegmental nucleus (VTg)11,12. Interestingly, the VTg was recently implicated in regulation of diencephalic medial mammillary bodies and the memory function in rats13,14. On the contrary to GABAergic neurons, in the Tal1cko mice, the number of glutamatergic neurons is increased in the interpeduncular nucleus and the LDTg, which provides excitatory projections to the VTA10,15.

As the brainstem nuclei housing Tal1 dependent neurons have been implicated in the control of the dopamine neurons and in the regulation of movement, motivated behavior and learning, we studied how the altered development of the Tal1cko mice affects behavior and the function of the dopaminergic system. In these mice, we observed many behavioral features resembling clinical ADHD, including hyperactivity, increased motor impulsivity, altered response to reward, and impaired learning. Interestingly, the Tal1cko mice had no marked changes in their dopaminergic system but, similar to the ADHD patients, showed a paradoxical calming response to pharmacologically stimulated dopamine release.

Materials and methods

Methods are described briefly below, see Supplementary Information for detailed descriptions.

Mice

Mice carrying En1Cre16 and Tal1flox11 alleles were crossed to generate En1Cre/+; Tal1flox/flox (Tal1cko) mice. In the Tal1cko mice, the En1Cre allele drives recombination tissue-specifically both in the midbrain and rhombomere 1, but this results in a failure of brainstem GABAergic neurogenesis only in the embryonic rhombomere 110,17,18. Four cohorts of wild-type (total n = 74, females; n = 56, males) and Tal1cko (total n = 48 females; n = 38, males) mice were generated in outbred ICR background for behavioral analyses. The littermates of the Tal1cko mice, carrying different combinations of the Tal1flox and En1Cre alleles, were included in the wild-type group. The mice were analyzed at the age of 3–4 months. The body weight of the Tal1cko mice is lower than that of wild-type mice (males, WT, 35.7 g, Talcko, 27.4 g; females, WT, 27.0 g, Tal1cko, 21.1 g). Behavioral testing was approved by the National Animal Experiment Board of Finland (License numbers ESAVI/7548/04.10.07/2013, ESAVI/8132/04.10.07/2017) according to the EU legislation (Directive 2010/63/EU) harmonized with Finnish legislation.

Drugs

The following drugs were used: amphetamine (GlaxoSmithKline), GBR12909 dihydrochloride (Tocris), atomoxetine (Orion Pharma, capsule contents dissolved in saline followed by brief centrifugation), SCH23390 hydrochloride (Sigma), and raclopride tartrate (Sigma) were dissolved in sterile saline. All drug solutions were injected at the volume of 10 ml/kg.

Behavioral analyses

Following behavioral analyses were performed: Open field, Elevated zero maze, Light-dark box, Social approach, Novel object recognition, 3-compartment test for sociability, Rotarod, Multiple static rods, Hot-plate, Pre-pulse inhibition, Forced swim test, Fear conditioning, T-maze, Water maze, Circadian activity, Nest construction, Burrowing, Marble burying test, Grooming, Stress-induced hyperthermia, IntelliCage for flexible sequencing task, motor impulsivity, saccharin preference and delay discounting. For the order of the behavioral tests and used cohorts of animals, see Supplementary Information.

Amphetamine-conditioned place preference was used to assess the rewarding properties of amphetamine in wild-type and Tal1cko mice in an unbiased and counterbalanced manner as described19 with modifications20.

Immunohistochemistry and DA neurons counts

To analyze DA neuron number, the mouse brains were processed as previously described10.

Measurement of tissue dopamine by HPLC

For brain monoamine measurements the samples were obtained from the relevant dissected brain regions using a mouse brain matrix as previously described21. In addition, prefrontal cortex (PFC) was collected from in front of the striatal slice after removal of the olfactory bulbs. Dopamine and its metabolites were analyzed as described previously22 using HPLC with electrochemical detection.

Measurement of dopamine release by cyclic voltammetry

Acute striatal mouse brain slices were prepared, dopamine elicited from axon terminals, and transient dopamine signals (release and uptake) were detected using fast-scan cyclic voltammetry as previously described21. Amphetamine (5 µM, d-amphetamine hemi-sulfate, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added to the recording solution after a stable baseline of stimulated dopamine transients was reached, and the responses were recorded until the amphetamine-induced dopamine efflux through dopamine transporter was measured.

In vivo microdialysis of dopamine release

Mice were surgically implanted with indwelling guide cannuli targeted into the NAc or dorsal striatum. After a recovery period, amphetamine was injected at 3 mg/kg, i.p., and thereafter dialysate was collected for dopamine measurement by HPLC with electrochemical detection21.

Data analysis and statistics

The sample size was based on earlier experience on behavioral and other testing procedures. The experimental animals were subjected to the experimental groups in a random manner. Randomization was applied for the testing order in conventional tests (Random number calculators available at https://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/randMenu/). Blinding was applied at all steps during testing and analysis—experimenter was unaware of genotypes and treatments, the group codes were opened after collecting the data and running the analysis. Exclusion criteria for behavioral data were either sickness of the animal, verified measurement error, or technical failure. No data were excluded. Behavioral data were evaluated using an ANOVA model with genotype (wild-type, Tal1cko mice) and sex as between subject factors. Within subject factors were added as needed when exploring the dependence of genotype effects on place or time (e.g., open field activity, water maze, IntelliCage etc.). Significant interactions and where necessary significant main effects were further explored by post-hoc tests or by splitting the ANOVA model, as appropriate. The data are presented as mean +/− standard error of the mean, and n indicates the number of biological replicates. Data between sexes were pooled for figures unless otherwise stated.

Results

Development of anterior brainstem GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons, involved in the regulation of dopaminergic pathways and in the basal ganglia output, is altered in the Tal1cko mice10. Therefore, we analyzed basal ganglia regulated behaviors in these animals. The summary of the behavioral analyses is presented in Table 1 (Supplementary Material).

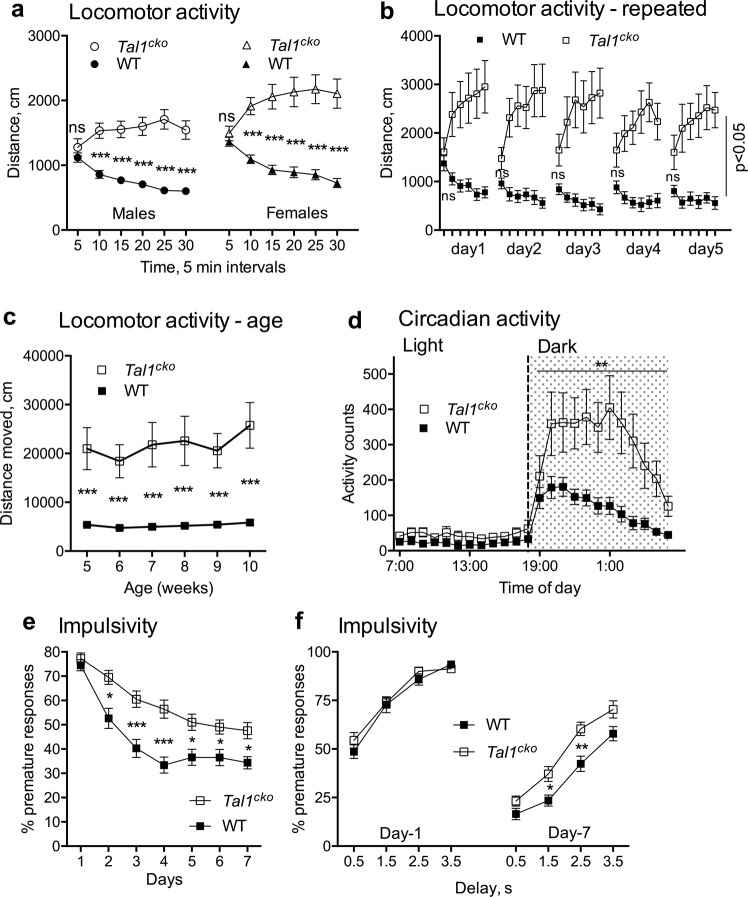

The Tal1cko mice display a distinct pattern of hyperactivity and motor impulsivity

To analyze activity and movement, we first recorded Tal1cko mice for both within-trial and between-trial locomotor activity in the open field test. In the beginning of the trial, Tal1cko mice had normal locomotor activity (Fig. 1a) but as wild-type mice decreased their activity over the course of the trial, the Tal1cko mice failed to habituate to the test environment and instead displayed within-trial hyperactive behavior (Fig. 1a). Repeated open field testing further revealed a between-trial deficiency in habituation (Fig. 1b). In a longitudinal testing of the activity, Tal1cko mice were hyperactive from juvenile age until adulthood (Fig. 1c). Consistent with the open field test, individually housed Tal1cko mice showed increased activity during long term monitoring in the home cage (Fig. 1d). However, and as seen in wild-type mice, their peak activity occurred in the dark cycle while the activity during the inactive light cycle remained unchanged suggesting no obvious change in the circadian rhythm (Fig. 1d). We tested impulsive behavior by training animals to suppress motor action (nosepoke) in the IntelliCage in order to get access to drinking water and found that Tal1cko mice made more premature nosepokes, which means that mice reacted before the intended time elapsed and suggests a failure to wait. Both groups improved over time, but Tal1cko mice performed worse throughout the experiment (Fig. 1e, f). Motor coordination of the Tal1cko mice was slightly better in the rotarod test (Fig S1a) while a subtle deficit appeared in the multiple rod test (Fig S1b). This difference might be explained by different demands of the tasks, as in the rotarod test the hyperactive phenotype may rescue the slight deficit in coordination.

Fig. 1. Hyperactivity and motor impulsivity in Tal1cko mice.

a In the open field test, the locomotor activity of the Tal1cko mice was normal in the beginning of the trial, but in contrast to normal within-trial habituation and decrease of activity in wild-type mice, the Tal1cko mice showed progressively increasing activity (RM ANOVA genotype × time interaction F5,850 = 57.7, p < 0.0001), leading to increased locomotor activity (distance traveled in 30 min) in Tal1cko mice (RM ANOVA genotype F1,170 = 107.5, p < 0.0001). N = 174 (54 WT M; 42 KO M; 43 WT F; 35 KO F). b Open field test repeated on 5 consecutive days showed persistent hyperactivity (RM ANOVA genotype F1,20 = 11.1, p = 0.0033) and no between-trial habituation of female Tal1cko mice (RM ANOVA days F4,40 = 1.3, p = 0.28). First timebin on all days, no genotype difference p > 0.05, other timebins p < 0.05, Bonferroni’s test. N = 23 (12 KO; 11 WT). c Longitudinal open field testing showed hyperactivity in Tal1cko mice from juvenile age through adulthood (RM ANOVA genotype F1,30 = 78.44, p < 0.001. N = 32 (6 KO F; 26 WT F). d Analysis of circadian activity in single housed mice showed higher activity of the Tal1cko mice in home cage setting during the dark cycle (RM ANOVA genotype F1,90 = 11.3, p = 0.0011). **p < 0.01, between genotypes, ANOVA. N = 104 (WT M 40; KO M 31; WT F 11; KO F 12). e Impulsivity as measured by suppression of motor action in the IntelliCage. The Tal1cko mice displayed more premature responses and inability to wait at longer delays along with delayed learning (RM ANOVA genotype F1,22 = 18.4, p = 0.0003, interaction genotype × days F6,132 = 3.9, p = 0.0012). N = 24 (13 WT F; 11 KO F). f Percentage premature responses at increasing delays on day 1 shows no difference between the genotypes (RM ANOVA genotype F1,22 = 0.523, p = 0.477). At day 7, the Tal1cko mice are impaired at delays of 1.5 s and 2.5 s in the impulsivity testing (RM ANOVA genotype F1,22 = 10.59, p = 0.0036). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, between genotypes, Bonferroni’s test. N = 24 (13 WT F; 11 KO F).

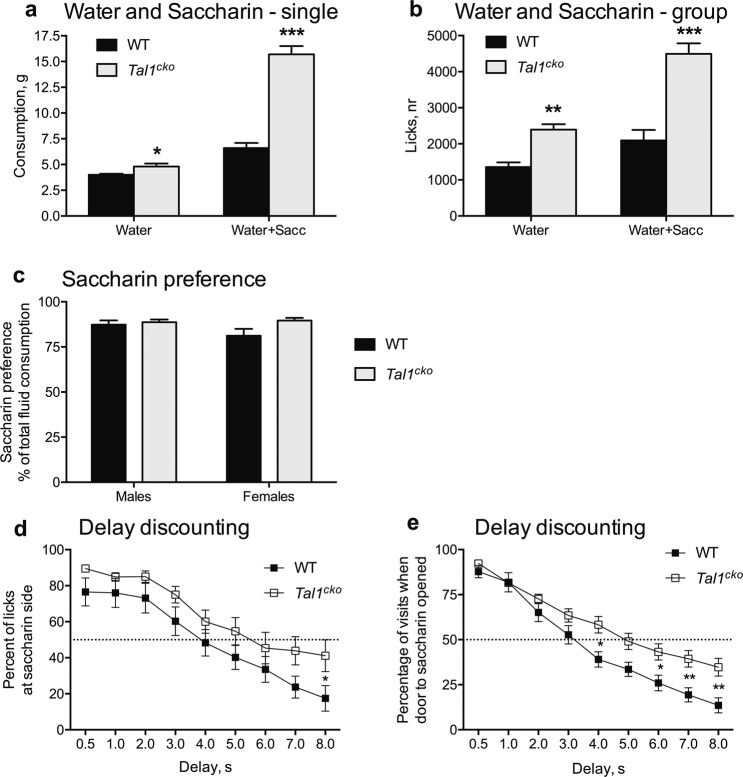

Changes in reward behavior in the Tal1cko mice

Next, we asked if reward processing and motivated behavior was altered in the Tal1cko mice. Water consumption of the Tal1cko mice was slightly increased at baseline (Fig. 2a). When given a choice between plain water and a palatable solution containing 0.5% saccharin in water, both the wild-type and the Tal1cko mice strongly preferred the saccharin solution (Fig. 2c), but the availability of saccharin provoked the Tal1cko mice to consume considerably greater amounts of the saccharin containing solution. This suggests that sensing reward is enhanced in the Tal1cko mice. To further study the reward behavior, we analyzed the response of female mice to saccharin in the Intellicage system. Similar to the males, the availability of saccharin strongly increased drinking of the female Tal1cko mice (Fig. 2b). When the access to saccharin was delayed, in comparison to immediate access to water, the Tal1cko mice showed reduced delay discounting as measured by enhanced saccharin preference (Fig. 2d), and persistence in waiting to get access to saccharin (Fig. 2e) at longer delays compared to the wild-type mice.

Fig. 2. Reward behavior.

a. Liquid consumption in single housed male mice The Tal1cko mice showed increased drinking when only water was available and the difference was even larger when saccharin was available (ANOVA genotype F1,45 = 94.6, p < 0.001; ANOVA condition F1,45 = 314.0, p < 0.001; interaction F1,45 = 117.2, p < 0.001; *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, between genotypes, t-test) N = 47 (29 WT M; 18 KO M). b. Liquid consumption (lick number) of female mice, housed in social groups in the IntelliCage, was increased in the Tal1cko mice (F1,77 = 26.7, p < 0.0001 with water only; F1,77 = 27.5, p < 0.0001 with water and saccharin), N = 79 (43 WT F; 36 KO F). c Preference for sweet taste (0.5% saccharin), as calculated from total consumption of liquid, was not different between the Tal1cko and wild-type mice in either sex (F1,77 = 0.002, p = 0.96, p < 0.05) (F1,77 = 0.002, p = 0.96, p < 0.05). d Delay discounting in the IntelliCage—preference for saccharin expressed as percentage of licks at increasing delays to opening the door to saccharin side (RM ANOVA genotype F1,22 = 3.0, p = 0.097). In the wild-type mice, saccharin preference was significantly lower than 50% already at a delay of 6 s (p = 0.04, one sample t-test), whereas it remained close to 50% in the Tal1cko mice mice even at 8 s delay (p = 0.33, one-sample t-test). The difference was also detected between the genotypes (p = 0.047, t-test) at 8 s delay, *p < 0.05, between genotypes, N = 24 (13 WT F; 11 KO F). e Delay discounting—percentage of visits with door to saccharin opened at increasing delays (RM ANOVA genotype F1,22 = 6.4, p = 0.019), N = 24 (13 WT F; 11 KO F).

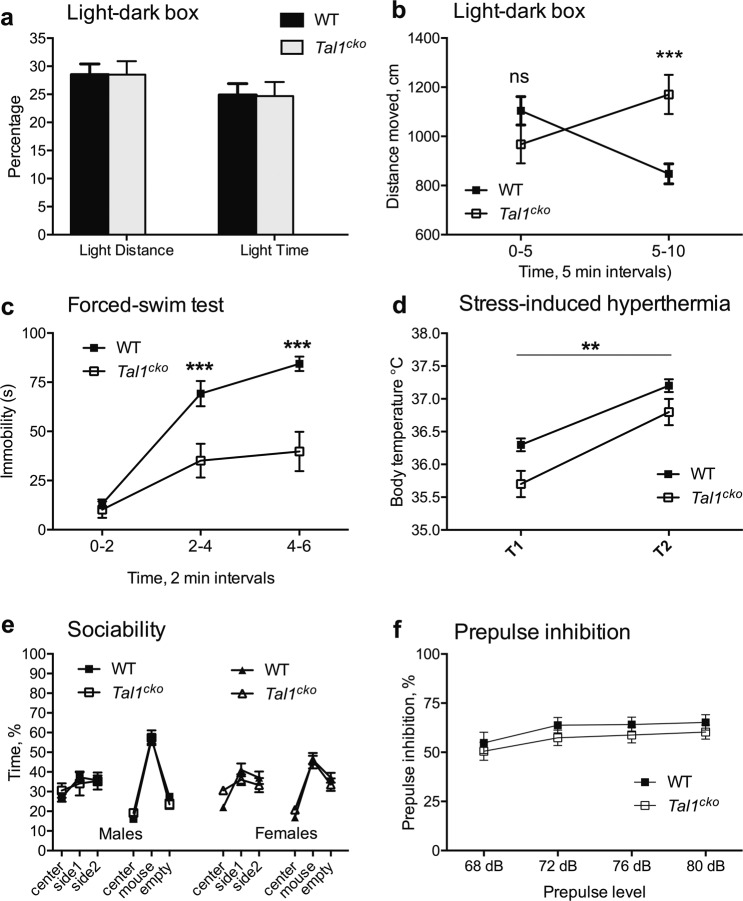

No changes in stress and anxiety-like behavior in the Tal1cko mice

As the anterior brainstem contains nuclei regulating the behavioral state associated with stress and anxiety, we tested the Tal1cko mice for changes in anxiety behavior. In the light-dark box, the proportion of distance moved and time spent in the light compartment was similar between the wild-type and the Tal1cko mice, suggesting no change in the levels of anxiety (Fig. 3a), a hypothesis also supported by normal behavior in the elevated zero-maze test (Table 1, Supplementary Material). As in the open-field test, at the beginning of the light-dark test the Tal1cko mice had normal locomotor activity, which later developed into hyperactivity (Fig. 3b). We found similar outcome in the forced swim test (Fig. 3c), a test widely used to assess despair behavior, in which the Tal1cko mice were more active after displaying normal activity in the beginning of the test. This appears consistent with the increased saccharin consumption (see above) suggesting reduced depressive behavior. However, it is also possible that the reduced immobility of Tal1cko mice is simply caused by their hyperactivity. We observed unaltered behavior of the Tal1cko mice in tests of stress-induced hyperthermia and social behavior (Fig. 3d, e). In addition, we found prepulse inhibition, a translatable measure of sensorimotor gating, to be unaltered in the Tal1cko mice (Fig. 3f).

Fig. 3. Anxiety and mood.

a The Light-dark box test revealed no difference between the wild-type and the Tal1cko mice in anxiety-like behavior. Both groups displayed similar avoidance of brightly illuminated compartment as shown by the percentage of time and distance moved in light compartment (time, F1,84 = 0.002, p = 0.96; distance, F1,84 = 0.0004, p = 0.98), N = 88 (27 M WT; 19 M KO; 24 F WT; 18 F KO). b Activity of the Tal1cko mice (total distance traveled) increased significantly during the second half of the testing period in the light-dark box (RM ANOVA genotype x time interaction F1,84 = 53.2, p < 0.0001). ***p < 0.001, between genotypes, Bonferroni’s test, N = 88 (27 M WT; 19 M KO; 24 F WT; 18 F KO). c In the forced swim test, the time of immobility in 2 min intervals was significantly reduced in the Tal1cko mice (RM ANOVA genotype F1,28 = 39.3, p < 0.0001, interaction genotype x time F2,56 = 29.1, p < 0.0001), ***p < 0.001, between genotypes, Bonferroni’s test, N = 30 (18 M WT; 12 M KO). d Stress-induced hyperthermia. The Tal1cko mice had lower basal body temperature (F1,22 = 8.5, p = 0.0081), and stress induced equal hyperthermic effect in both Tal1cko and wild-type mice (F1,22 = 0.5, p = 0.49). **p < 0.01, between genotypes, ANOVA. N = 24 (14 M WT; 10 M KO). e Sociability test. Time with the stimulus mouse was not altered between the genotypes (F1,32 = 0.007, p = 0.94). N = 36 (9 M WT; 7 M KO; 13 F WT; 7 F KO). f Prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle reflex was not different between the groups (RM ANOVA genotype F1,28 = 1.4, p = 0.25), but increased with the increasing sound pressure level of pre-pulse (RM ANOVA pre-pulse level F3,84 = 9.3, p < 0.001; genotype x pre-pulse level interaction F3,84 = 0.2, p = 0.9), N = 30 (18 M WT; 12 M KO).

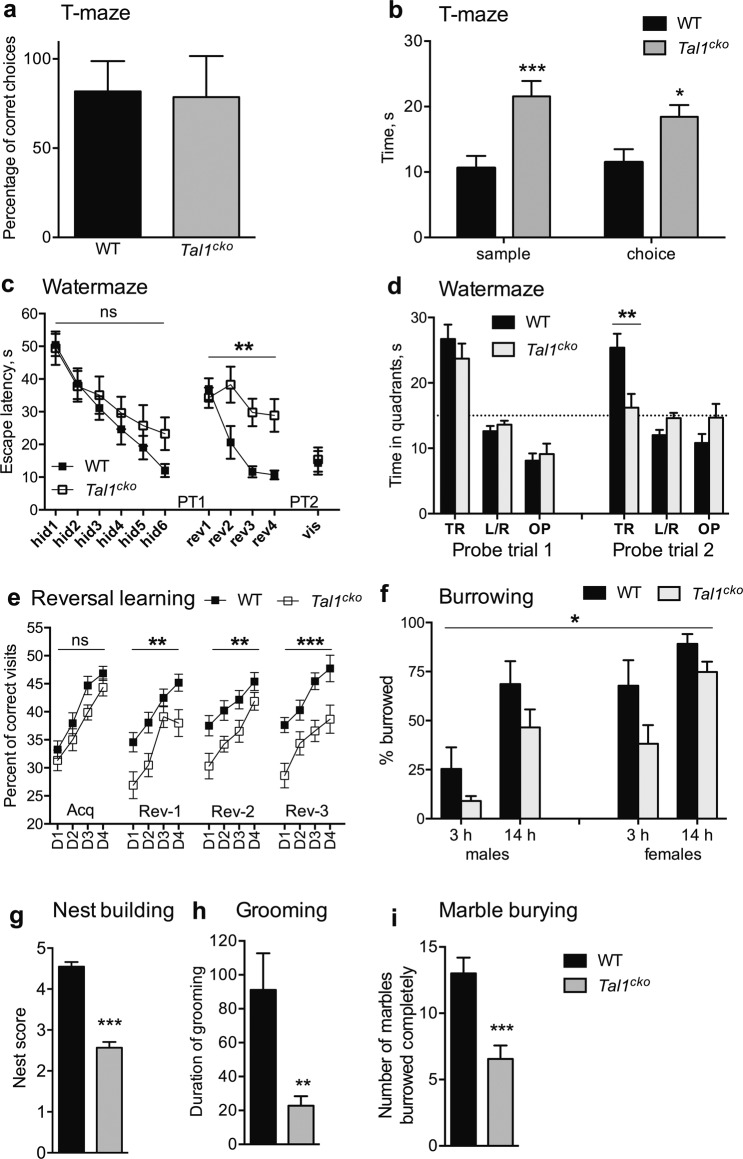

Defects of learning and complex behaviors in the Tal1cko mice

Next, we analyzed learning and complex species-specific behavior of the Tal1cko mice. In the T-maze test for working memory, the spontaneous alternation of the Tal1cko mice was not affected (Fig. 4a). However, it took longer for the Tal1cko mice to complete the trial (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4. Cognitive functions, learning and memory, and innate behaviors.

a Spontaneous alternation (working memory) in T-maze test was not altered in the Tal1cko mice (ANOVA genotype F1,32 = 0.32, p = 0.58), N = 36 (9 M WT; 7 M KO; 13 F WT; 7 F KO). b Time for completing the trials in T-maze was longer in the Tal1cko mice (RM ANOVA F1,32 = 12.6, p = 0.0012), N = 36 (9 M WT; 7 M KO; 13 F WT; 7 F KO). c Spatial learning (latency to find the platform) in water maze-test. There was no difference between the wild-type and Tal1cko mice in learning to find escape platform in acquisition phase (RM ANOVA genotype F1,20 = 1.0, p = 0.33, trial block F5,100 = 19.9, p < 0.0001, no interaction between genotype and trial blocks). However, the Tal1cko mice were unable to improve their performance in reversal learning when platform was moved to the opposite quadrant (RM ANOVA genotype F1,20 = 14.2, p = 0.0012, trial block F3,60 = 9.6, p < 0.0001, interaction genotype x trial block F3,60 = 4.5, p = 0.0064). Navigation to visible platform was not different between the groups, N = 22 (12 M WT; 10 M KO). d Search bias (preference to quadrant) in probe trials without escape platform available confirmed no difference between the groups after initial acquisition (in probe trial 1 where both groups spent similar amount of time in trained quadrant (F1,20 = 0.9, p = 0.35). However, in probe trial 2, after reversal learning sessions, the Tal1cko mice did not show any preference neither to new nor old quadrant, and spent significantly less time in correct quadrant as compared to the wild-type (F1,20 = 9.2, p = 0.066). PT = probe trial. N = 22 (12 M WT; 10 M KO). e. Flexible sequencing task in IntelliCage. The Tal1cko mice acquired the task in the first phase with no difference to wild-type mice (RM ANOVA genotype F1,42 = 3.1, p = 0.09). However, learning of the Tal1cko mice remained significantly worse in each of the following reversal phases, suggesting reduced behavioral flexibility (RM ANOVA genotype F1,42 > 8.8, p > 0.005), N = 44 (24 F WT; 20 F KO). f Burrowing was reduced in Tal1cko mice (RM ANOVA genotype F1,36 = 7.0, p = 0.0118), N = 40 (10 M WT; 10 M KO; 10 F WT; 10 F KO). g Nest building was impaired in the Tal1cko mice (F1,112 = 111.2, p < 0.0001), N = 116 (40 M WT; 31 M KO; 23 F WT; 22 F KO). h Tal1cko mice engaged significantly less time in grooming during 10 min test (F1,20 = 9.4, p = 0.0061), N = 22 (11 F WT; 11 F KO). i Marble burying test. The Tal1cko mice buried less marbles than wild-type group (F1,31 = 19.1, p = 0.0001), *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, between genotypes, t-test, Bonferroni’s test, or ANOVA, N = 35 (6 M WT; 7 M KO; 11 F WT; 11 F KO).

In the Morris water maze test, the Tal1cko mice were able to learn to find the hidden platform (Fig. 4c). The Tal1cko mice also showed preference to the trained quadrant in the following probe trial (Probe trial 1, Fig. 4d). However, when the platform was moved to the opposite quadrant, the Tal1cko mice were severely impaired in learning the new location (Fig. 4c) and showed a completely random search strategy after training (Probe trial 2, Fig. 4c, d). This finding of reduced behavioral flexibility was further corroborated by impaired reversal learning of the Tal1cko mice in the Intellicage flexible sequencing task (Fig. 4e).

In the novel object recognition test, the Tal1cko mice showed again the inverse pattern of locomotor habituation, but this did not significantly change their relative preference for the novel object (Fig S2a, b). Interestingly, contextual fear conditioning was impaired in Tal1cko mice (Fig S2c).

We then analyzed mouse species-specific behaviors, such as grooming, nest construction, burrowing and marble burying, likely requiring animals to focus and concentrate their efforts on specific tasks. In the Tal1cko mice, all of these behaviors were significantly reduced (Fig. 4f–i).

Dopaminergic system in the Tal1cko mice

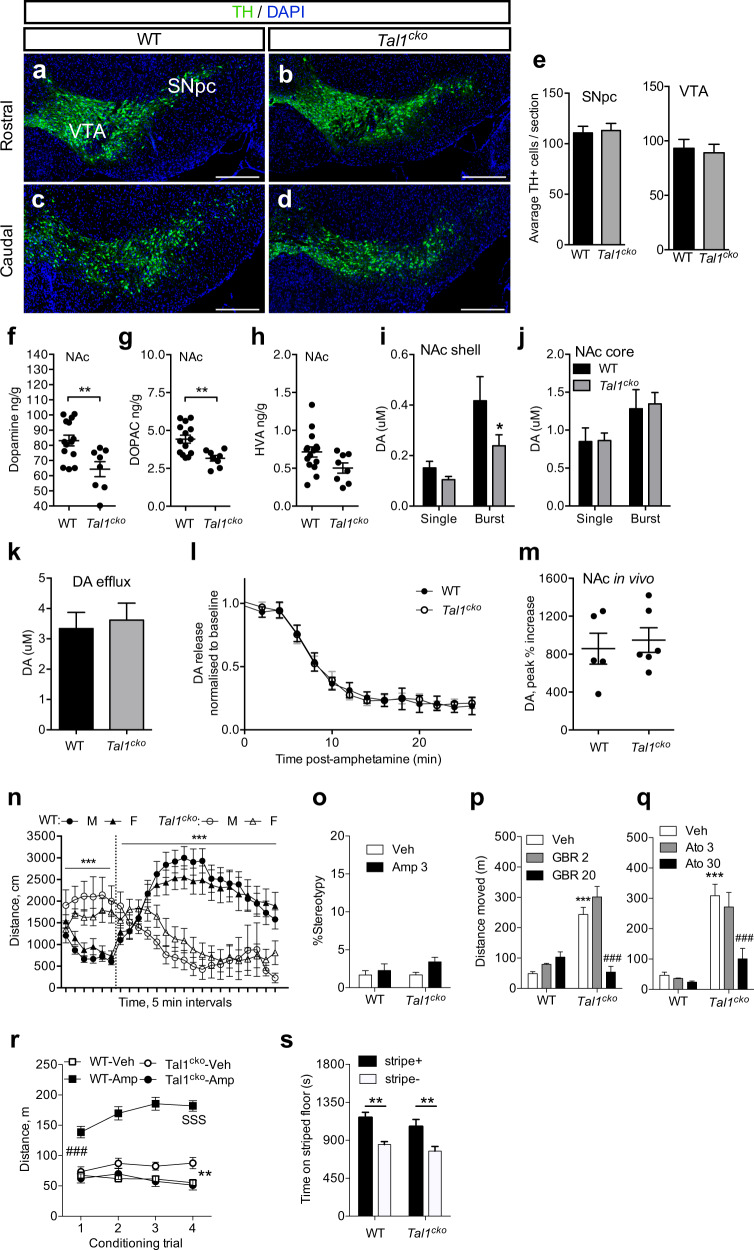

We next asked whether a change in the GABAergic and glutamatergic components of the dopaminergic circuitry, due to the inactivation of Tal1, could affect the dopamine neuron numbers. Quantification of dopamine neurons in the ventral midbrain revealed no change in their numbers in the Tal1cko mice (Fig. 5a–e). We then addressed the functionality of the dopamine system. Analysis of the neurotransmitter levels in the tissue of the dorsal striatum, nucleus accumbens (NAc), and prefrontal cortex, revealed a decrease in the levels of dopamine and its metabolites in the Tal1cko mice (Fig. 5f–h, Fig S3b–g). All the target tissues of the dopaminergic system showed the same trend, but the difference was most pronounced in the NAc. Serotonin and its metabolite 5-HIAA levels in the dorsal striatum, nucleus accumbens, and prefrontal cortex were unaltered in the Tal1cko mice (Fig S4). Noradrenaline content was also not changed in the prefrontal cortex of the Tal1cko mice (Fig S4).

Fig. 5. Dopaminergic system in Tal1cko mice.

a–d Immunohistochemical analysis of midbrain TH+ neurons in the wild-type and Tal1cko mice. Representative images of TH-labeled coronal sections through the VTA and the SNpc at rostral and caudal level in wild-type and Tal1cko brains. e Normal number of TH+ neurons in in the Tal1cko mice, both in the substantia nigra pars compacta and the ventral tegmental area (for SNpc, N = 3, p = 0.84; for VTA, N = 3, p = 0.77, t-test). Scale bar: 100 µm. SNpc: substantia nigra pars compacta; SNpr: substantia nigra pars reticulata; TH: tyrosine hydroxylase; VTA: ventral tegmental area. f–h Dopamine and metabolite levels in the nucleus accumbens measured in histological samples of the Tal1cko and wild-type mice, **p < 0.01, t-test, N = 14 WT, 8, KO). i–j Dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens subregions. Burst stimulation revealed a dampened dopamine release in the NAc shell of the Tal1cko mice analyzed by cyclic voltammetric measurement (ANOVA, genotype, for shell F1,26 = 4.06, p = 0.041; for core, F1,44 = 0.051, p > 0.05). Burst stimulation protocol evoked larger dopamine release than single pulse both in shell and core subregions (ANOVA, stimulus type, for shell, F1,26 = 14.59, p < 0.001; for core, F1,44 = 7.09, p = 0.011). *p < 0.05, the Tal1cko mice versus wild-type mice, Bonferroni’s test, N = 14 WT, 16 KO, for shell; N = 22 WT, 26 KO, for core). k Amphetamine-induced non-stimulated dopamine release in the dorsal striatum. No difference in cyclic voltammetry-measured dopamine efflux between the Tal1cko and wild-type mice (p > 0.05, t-test). N = 17 WT, 14 KO. l Stimulated dopamine release under amphetamine perfusion in the dorsal striatum. No differences were detected between the Tal1cko and wild-type mice (ANOVA F1,266 = 0.07, p > 0.05). N = 13 WT, 11 KO. m In vivo dopamine microdialysis in the nucleus accumbens. Amphetamine (3 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered to freely-moving Tal1cko and wild-type mice followed by microdialysis analysis of extracellular dopamine. No difference was found between the mouse lines (p > 0.05, t-test). N = 5 WT, 6 KO. n Acute effect of intraperitoneal amphetamine (timing of injection indicated by a vertical dashed line, 3 mg/kg) after 30 min of habituation in the open field. Both male and female wild-type mice responded with increased locomotion after the injection of amphetamine, whereas amphetamine rescued the hyperactive phenotype in the Tal1cko mice of both sexes (RM ANOVA genotype F1,68 = 9.6, p = 0.0028, time F23,1564 = 11.8, p < 0.0001, genotype × time interaction F23,1564 = 3.3, p < 0.0001). ***p < 0.001, genotype × amphetamine interaction, ANOVA. N = 72 (Amphetamine–6 WT M; 8 KO M; 13 WT F; 12 KO F; Saline–7 WT M; 5 KO M; 12 WT F; 9 KO F). o Amphetamine-induced stereotypy was not detected in the wild-type and Tal1cko mice (ANOVA drug F1,16 = 3.3, p = 0.09, genotype F1,16 = 0.8, p = 0.37), N = 10 WT, 10 KO. p Dopamine transporter inhibition by GBR12909 decreased hyperactivity in the Tal1cko mice (ANOVA dose F2,42 = 15.5, p < 0.001; genotype F1,42 = 55.0, p < 0.001; interaction F2,42 = 27.2, p < 0.001). ***p < 0.001, between the genotypes, Bonferroni’s test; ###p < 0.001, between vehicle and GBR12909-treated groups, Bonferroni’s test. N = 24 WT, 24 KO. q Noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor atomoxetine reduced hyperactivity in the Tal1cko mice (ANOVA dose F2,39 = 6.5, p = 0.004; genotype F1,39 = 49.8, p < 0.001; interaction F2,39 = 4.4, p = 0.02). ***p < 0.001, between the genotypes, Bonferroni’s test; ###p < 0.001, between vehicle and atomoxetine-treated groups, Bonferroni’s test. N = 20 WT, 25 KO. r Amphetamine-conditioned place preference. Locomotor activity during the conditioning trials with vehicle (CS-trials) and amphetamine (CS + trials). Amphetamine acutely increased locomotor activity of the wild-type mice, but not that of the Tal1cko mice (ANOVA genotype × drug interaction F1,60 = 75.66, p < 0.001), ###p < 0.001, between vehicle and amphetamine-treated wild-type mice, t-test. Amphetamine caused locomotor sensitization in the wild-type mice but decreased locomotor activity in the Tal1cko mice to the level of vehicle-treated wild-type mice (ANOVA genotype × drug × conditioning trial interaction F3,180 = 23.36, p < 0.001). SSSp < 0.001 wild-type mice, between 1st and 4th conditioning trial, Bonferroni’s test; **p < 0.01, between vehicle and amphetamine-treated Tal1cko mice, t-test. N = 16 WT, 16 KO. s In the conditioned place preference test trial, both the wild-type and the Tal1cko mice expressed amphetamine-induced conditioned place preference (ANOVA conditioning subgroup F1,28 = 24.27, p < 0.001) equally (ANOVA genotype F1,28 = 2.22, p = 0.15; ANOVA genotype × conditioning subgroup interaction F1,28 = 0.06, p = 0.81). **p < 0.01 between stripe+ and stripe− conditioning subgroups, Bonferroni’s test, N = 16 WT, 16 KO. Mice in the stripe+ conditioning subgroup had received amphetamine paired with the striped floor and vehicle paired with the dot floor, while the mice in the stripe− conditioning subgroup had received amphetamine paired with the dot floor and vehicle paired with the striped floor. Data is expressed as time spent in seconds on the striped floor type.

We then used cyclic voltammetry to measure the electrically stimulated dopamine release in brain slices containing the NAc shell, the NAc core, and the dorsal striatum. While the single pulse-evoked dopamine release was normal in the Tal1cko tissue, burst stimulation protocol revealed a deficit in the release in the Tal1cko tissue, specifically in NAc shell (Fig. 5i, j, Fig S3h). Clearance of dopamine was unaltered in the Tal1cko striatal tissue (Fig S3i–k). In amphetamine-induced dopamine efflux in the dorsal striatum, we observed no difference in the magnitude or kinetics of dopamine release between the wild-type or Tal1cko tissue (Fig. 5k, l). Because of the high variability in the occurrence and levels of amphetamine-induced dopamine efflux in the NAc area, we were not able to perform similar experiments there. Finally, we studied the effect of amphetamine on dopamine release in vivo. Using microdialysis in the NAc and dorsal striatum, we observed unaltered levels of extracellular dopamine and normal amphetamine-induced dopamine release in the Tal1cko mice (Fig. 5m, Fig S3l).

Amphetamine ameliorates hyperactivity in the Tal1cko mice

In order to test the behavioral consequences of pharmacologically induced dopamine signaling in the Tal1cko mice, we first treated them with amphetamine. Strikingly, in contrast to the wild-type mice, whose locomotor activity was markedly enhanced, the activity of the Tal1cko mice was decreased by amphetamine (Fig. 5n, r). No amphetamine-induced stereotypy was detected with the dose used (3 mg/kg, Fig. 5o).

Since amphetamine is known to act through multiple targets, we screened the pharmacological mechanisms of the hyperactivity-lowering amphetamine effect in the Tal1cko mice by using various ligands. Inhibition of the dopamine transporter by GBR12909 increased locomotor activity in the wild-type mice, but decreased hyperactivity of the Tal1cko mice (Fig. 5p). The noradrenaline transporter inhibitor atomoxetine also decreased hyperactivity in the Tal1cko mice without an effect on wild-type animals (Fig. 5q). Dopamine D1 and D2 receptor antagonists had no effect on the Tal1cko mice locomotor activity, but decreased wild-type activity with the highest doses (Fig S3m, n).

Amphetamine is rewarding in the Tal1cko mice

To analyze amphetamine-induced reward in the Tal1cko mice, we carried out an amphetamine conditioned place preference test. We found that amphetamine equally elicited place preference in the wild-type and the Tal1cko mice (Fig. 5r, s). When we analyzed the effect of amphetamine on locomotor activity during the conditioning, we observed that whereas amphetamine caused a typical locomotor sensitization in the wild-type mice, it decreased the locomotor activity in the Tal1cko mice to the level of vehicle treated wild-type mice (Fig. 5r).

Discussion

GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons in the anterior brainstem have been implicated in the regulation of mood, motivation and movement. These neurons are developmentally and anatomically highly complex, and some of their subtypes control the brainstem neuromodulatory systems. We show that the Tal1cko mice, with changes in specific neuronal subgroups in the anterior brainstem, have alterations in their activity, impulsivity and reward behavior, that recapitulate many endophenotypes of ADHD. Although some of the Tal1 dependent neurons are thought to control the dopaminergic system, the levels of dopamine and its release were only modestly affected in the Tal1cko mice. Strikingly, the behavioral response of the Tal1cko mice to amphetamine resembled that of ADHD patients. Our studies suggest Tal1 dependent anterior brainstem GABAergic and glutamatergic neuron subgroups as an important new focus for understanding the neurobiology of this common behavioral disorder.

Behavioral defects in the Tal1cko mice: comparison with ADHD

An earlier study of mice with a global neuronal inactivation of the Tal1 gene (Nestin-Cre; Tal1flox) suggested a hyperactivity phenotype, but the analysis was complicated by defects in locomotion, circling behavior and premature lethality11. Our approach to use the Tal1cko mice allowed a detailed behavioral characterization of mice, in which the neuronal defects due to Tal1 deficiency are restricted to specific regions in the anterior brainstem. The behavioral changes in the Tal1cko mice include hyperactivity, enhanced motor impulsivity, altered reward processing, deficits in learning, behavioral flexibility and task completion—all cardinal features of ADHD.

The Tal1cko mice display a specific hyperactive phenotype comprising initial normoactivity in a novel environment that rapidly develops into hyperactivity23. The hyperactive phenotype is present already in a juvenile age, and persists into adulthood. Remarkably, the Tal1cko mice exhibit normal spontaneous locomotor activity during the light period of their circadian cycle, consistent with normal night-time activity by actigraphy observation in patients with ADHD24. This suggests that the observed hyperactivity in Tal1cko mice is not generalized, but instead shows specificity in tasks that require exploration and attention. Interestingly, different forms of impaired habituation have been reported in ADHD patients25,26 in addition to some other psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia27. The prepulse inhibition of the startle response, used to measure defective sensorimotor gating in schizophrenia28, appears normal in ADHD patients28,29 (but see29 and30), and also was unchanged in the Tal1cko mice. In the analyses of habituation of the Tal1cko mice, we were able to distinguish deficiencies both in intra-session and inter-session habituation, which may provide means for refinement of the habituation deficit as an endophenotype in ADHD31,32. As with hyperactivity, initially normal impulsive behavior in ADHD patients manifests as motor impulsiveness as the test session progresses23. This pattern is also phenocopied in the Tal1cko mice. The Tal1cko mice are hypersensitive to rewarding effect of saccharin, which is of interest as ADHD and substance use disorder share comorbidity33. Normal social interaction was observed in the Tal1cko mice, unlike ADHD patients that have been reported to show changes in their social interaction34.

Putative relationships between the neuroanatomical and behavioral changes in the Tal1cko mice

Tal1 dependent GABAergic neurons in the VTA, RMTg and SNpr regulate the adjacent dopaminergic neurons, but also have projections to other brainstem nuclei and more anterior regions of the brain, participating in the control of both motivated behavior and movement. For example, the targets of the VTA GABAergic neurons include the PFC, implicated in the control of impulsive behavior6, and the nucleus accumbens, which has been implicated in reward behavior4. PFC also receives neuromodulatory afferents from the brainstem nuclei which are innervated by the Tal1 dependent GABAergic neurons35. Of these, locus coeruleus noradrenergic and dorsal raphe serotonergic systems have been linked to impulsivity8. The RMTg controls avoidance behavior3,36, but a lesion or inhibition of the RMTg also results in increased locomotor activity in the rat37–40. The SNpr GABAergic neurons provide output from the basal ganglia inhibiting the motor nuclei in the thalamus. Therefore, loss of SNpr neurons may contribute to the hyperactivity of the Tal1cko mice. The neurons of the SNpr fall into two broad categories, the anterior SNpr and the posterior SNpr neurons, which differ by their embryonic origins and gene expression10. In the Tal1cko mice, only the posterior-type SNpr neurons are affected. Future studies should address the projection patterns and functions of the distinct SNpr subgroups, including projections to the thalamic nuclei. In addition to GABAergic neurons associated with the dopaminergic nuclei, Tal1 dependent GABAergic neurons are located in the ventral tegmental nucleus of Gudden (VTg)11,12. These neurons project to the medial mammillary bodies, regulate hippocampal theta waves, and are important for memory13. Interestingly, lesions of the VTg in rodents also cause hyperactivity41,42.

Whereas brainstem GABAergic nuclei are defective in the Tal1cko mice, glutamatergic neurons in specific brainstem nuclei, including the interpeduncular nucleus, LDTg and SNpc, are increased in their numbers10. In contrast to the inhibitory RMTg projections, the LDTg sends excitatory glutamatergic projection to the VTA to regulate reward behavior15. The increased numbers of the glutamatergic neurons may enhance excitatory drive to their target structures. However, although changes in excitation-inhibition balance have been associated with hyperactivity and ADHD43–46, it remains unclear how the imbalance in the brainstem GABAergic and glutamatergic neuron differentiation is reflected in the synaptic control of the multiple target cell types of the GABAergic and glutamatergic brainstem neurons in the Tal1cko mice.

It is unclear if the development or function of these tegmental nuclei is altered in the human ADHD patients. Very interestingly, however, a reduction in the anterior brainstem size has been shown to distinguish the ADHD patients from the controls47,48. Further studies should address if this reduction is due to changes in the local tegmental nuclei, axonal tracts, or both.

Dopamine signaling in the Tal1cko mice

Many of the Tal1 dependent anterior brainstem neurons are thought to regulate the dopaminergic neurons and basal ganglia circuits, whereas altered basal ganglia activity and dopaminergic signaling has been associated with ADHD. However, the exact roles of these pathways have remained elusive and it has been debated whether ADHD is a hypodopaminergic or hyperdopaminergic defect2.

Based on the neuroanatomical defects in the Tal1cko mice, an increase in the dopamine neuron activity could be predicted. However, our neurochemical analyses of the Tal1cko mice suggest only minor changes in the dopaminergic neurotransmission. Moreover, in the target tissues, the dopamine and dopamine metabolite levels are decreased rather than increased. Our results are consistent with the conclusion that ADHD-like symptoms can correlate with apparently reduced dopaminergic signaling. It is possible that the dampening of dopamine signaling in the Tal1cko mice is due to developmental feedback regulation or functional compensation.

Stimulant drugs such as amphetamine provide the mainstay of the ADHD pharmacotherapy49. Hyperactivity in the Tal1cko mice was rescued by amphetamine treatment, a finding that further supports the putative ADHD-like phenotype. Amphetamine did not induce stereotypy by the moderately low dose used, which is in line with earlier reports50,51. Striatal dopamine system may be underactive in the ADHD patients, and stimulant medication restores the deficit52. Similarly, amphetamine increases extracellular dopamine in the striatum, and at the behavioral level normalizes the hyperactive state in the Tal1cko mice. The release mechanisms for dopamine also remain functional in the Tal1cko mice both in vitro and in vivo, as shown by voltammetry and microdialysis data, respectively.

The mechanism of action of amphetamine in relieving ADHD symptoms remains elusive, partly because the pathophysiological basis of ADHD has not been confirmed, and partly because amphetamine’s effects are mediated by multiple molecular targets. Our data using more selective pharmacology suggests that, at least in the Tal1cko mice, amphetamine may act through increasing both dopamine and noradrenaline tone. Dopaminergic tone can be increased directly by stimulants both in prefrontal and striatal regions52. However, noradrenaline very sparsely innervates striatum, but instead the brainstem noradrenergic neurons send projections to the prefrontal regions53, and consequently prefrontal cortex has been suggested as a target for the atomoxetine effect54. Dopamine receptor antagonists failed to rescue the hyperactivity of the Tal1cko mice, which supports a conclusion that Tal1cko mice have a hypofunctional dopamine system. Taken together, stimulant-sensitive hypodopaminergia of the Tal1cko mice points towards a view of co-existence of an ADHD-like phenotype with attenuated dopamine signaling.

Our observation that amphetamine can have dramatically different effect on the locomotor activity and its sensitization in the wild-type and Tal1cko mice, yet is reward-inducing for both of them, further suggests that the hyperactivity and reward are independent of each other and mediated by distinct circuits. Interestingly, it has been proposed that tonic and phasic dopamine signaling are differentially affected in the ADHD patients55.

Comparison with other animal models of ADHD

ADHD is likely a heterogeneous deficit with different neurobiological bases. Similarly, clinical symptoms of ADHD have been observed in a variety of gene-modified animal strains, which have been adopted as animal models of ADHD2. Dopamine transporter deficient mouse line, coloboma mutant mice, and spontaneously hypertensive rats show behavioral hyperactivity similar to the Tal1cko mice, but there are also specific differences between these models56. In Tal1cko mice the task-related hyperactivity develops over time, which is similar in spontaneously hypertensive rats, but this is not seen in dopamine transporter deficient mouse line which are highly hyperactive from the beginning of the task. Coloboma mutant mice harbor a selection of neurological and other symptoms, which downplay their utilization as an animal model of ADHD56. The hyperactivity of Tal1cko mice shows sensitivity to stimulants, which is similar to dopamine transporter deficient mouse model and coloboma mouse model57,58, but spontaneously hypertensive rats have shown variable responses59–62. Atomoxetine reduces hyperactivity in Tal1cko mice and in spontaneously hypertensive rats, but not in dopamine transporter deficient mouse line63,64. Differences between the models exist in prepulse inhibition, which is deficient in spontaneously hypertensive rats65 and in the dopamine transporter deficient mouse line66, while Tal1cko mice are normal in this aspect. Social interaction was found to be normal in Tal1cko mice, while dopamine transporter deficient mice show decreased social investigation and increased reactivity in response to social investigation67. In spontaneously hypertensive rats, an unchanged68, reduced61,68, or increased69 social interaction has been reported. Impulsiveness is a shared phenotypic property in Tal1cko mice and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Both of these animal models have hypodopaminergic neurochemical phenotype70. It is not clear how well any of these animal models satisfy the construct validity of human ADHD. Multiple preclinical models may be needed to fully understand this behavioral disorder.

Conclusion

ADHD is a highly heritable neurodevelopmental disorder, but its genetic components remain poorly understood. Although work with genetically modified mice has demonstrated the causal relationship between the altered dopaminergic neurotransmission and hyperactivity, the candidate gene studies have failed to reveal a substantial role for variation in genes involved in dopaminergic neurotransmission as the genetic basis for ADHD2. Therefore, it is possible that defects in the other components of the basal ganglia circuitry are behind the etiology of this disorder. Although Tal1 gene variants have not been associated with the etiology of ADHD, our results show that a defect in a specific developmental event dependent on a single transcription factor, namely balanced differentiation of GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons in the developing anterior brainstem, leads to several endophenotypes of ADHD. Studies of these neurons, and the circuits they participate in, can lead to better understanding of the normal and abnormal control of activity, attention and reward.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Academy of Finland (J.P., T.R.), Sigrid Juselius Foundation (T.A.), University of Helsinki (T.A.), Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation (J.P, V.V., A.P.), and Biocenter Finland (V.V.).

Author contributions

The studies were planned by F.M., V.V., A.P., P.Pi., A.M., T.A., and J.P. The experiments were conducted by F.M., V.V., P.Pa., A.P., M.R., P.Pi., A.M., and T.A. The data analysis was performed by F.M., V.V., A.P., P.Pi., A.M., and T.A. J.P. and T.A. collected funding. The study was supervised by T.A. and J.P. J.P. and T.A. wrote the manuscript. All authors commented and accepted the manuscript

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Francesca Morello, Vootele Voikar

These authors jointly supervised this work: Teemu Aitta-aho, Juha Partanen

Contributor Information

Teemu Aitta-aho, Email: Teemu.Aitta-aho@Helsinki.Fi.

Juha Partanen, Email: Juha.M.Partanen@Helsinki.Fi.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41398-020-01033-8).

References

- 1.Bromberg-Martin ES, Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O. Dopamine in motivational control: rewarding, aversive, and alerting. Neuron. 2010;68:815–834. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallo EF, Posner J. Moving towards causality in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: overview of neural and genetic mechanisms. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:555–567. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00096-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrot M, et al. Braking dopamine systems: a new GABA master structure for mesolimbic and nigrostriatal functions. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:14094–14101. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3370-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morales M, Margolis EB. Ventral tegmental area: cellular heterogeneity, connectivity and behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017;18:73–85. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen JY, Haesler S, Vong L, Lowell BB, Uchida N. Neuron-type-specific signals for reward and punishment in the ventral tegmental area. Nature. 2012;482:85–88. doi: 10.1038/nature10754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown RE, McKenna JT. Turning a negative into a positive: ascending GABAergic control of cortical activation and arousal. Front. Neurol. 2015;6:135. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dudman JT, Krakauer JW. The basal ganglia: from motor commands to the control of vigor. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2016;37:158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalley JW, Robbins TW. Fractionating impulsivity: neuropsychiatric implications. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017;18:158–171. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2017.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kala K, et al. Gata2 is a tissue-specific post-mitotic selector gene for midbrain GABAergic neurons. Development. 2009;136:253–262. doi: 10.1242/dev.029900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lahti L, et al. Differentiation and molecular heterogeneity of inhibitory and excitatory neurons associated with midbrain dopaminergic nuclei. Development. 2016;143:516–529. doi: 10.1242/dev.129957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradley CK, et al. The essential haematopoietic transcription factor Scl is also critical for neuronal development. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006;23:1677–1689. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morello et al. Molecular fingerprint and developmental regulation of the tegmental gabaergic and glutamatergic neurons derived from the anterior hindbrain. Cell Reports33, 108268 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Dillingham CM, Frizzati A, Nelson AJ, Vann SD. How do mammillary body inputs contribute to anterior thalamic function? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015;54:108–119. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vann SD. Dismantling the Papez circuit for memory in rats. Elife. 2013;2:e00736. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lammel S, et al. Input-specific control of reward and aversion in the ventral tegmental area. Nature. 2012;491:212–217. doi: 10.1038/nature11527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimmel RA, et al. Two lineage boundaries coordinate vertebrate apical ectodermal ridge formation. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1377–1389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trokovic R, et al. FGFR1 is independently required in both developing mid- and hindbrain for sustained response to isthmic signals. EMBO J. 2003;22:1811–1823. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Achim K, et al. The role of Tal2 and Tal1 in the differentiation of midbrain GABAergic neuron precursors. Biol. Open. 2013;2:990–997. doi: 10.1242/bio.20135041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunningham CL, Gremel CM, Groblewski PA. Drug-induced conditioned place preference and aversion in mice. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:1662–1670. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiiskinen, T., Korpi, E. R. & Aitta-aho, T. Normal extinction and reinstatement of morphine-induced conditioned place preference in the GluA1-KO mouse line. Behav. Pharmacol.30, 405–411 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Kopra J, et al. Dampened amphetamine-stimulated behavior and altered dopamine transporter function in the absence of brain GDNF. J. Neurosci. 2017;37:1581–1590. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1673-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valros A, et al. Evidence for a link between tail biting and central monoamine metabolism in pigs (Sus scrofa domestica) Physiol. Behav. 2015;143:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sagvolden T, Aase H, Zeiner P, Berger D. Altered reinforcement mechanisms in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Behav. Brain Res. 1998;94:61–71. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(97)00170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boonstra AM, et al. Hyperactive night and day? Actigraphy studies in adult ADHD: a baseline comparison and the effect of methylphenidate. Sleep. 2007;30:433–442. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jansiewicz EM, Newschaffer CJ, Denckla MB, Mostofsky SH. Impaired habituation in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Cogn. Behav. Neurol. 2004;17:1–8. doi: 10.1097/00146965-200403000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Massa J, O’Desky IH. Impaired visual habituation in adults with ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2012;16:553–561. doi: 10.1177/1087054711423621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geyer MA, Braff DL. Habituation of the Blink reflex in normals and schizophrenic patients. Psychophysiology. 1982;19:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1982.tb02589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kohl S, Heekeren K, Klosterkotter J, Kuhn J. Prepulse inhibition in psychiatric disorders-apart from schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013;47:445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braff DL, Geyer MA, Swerdlow NR. Human studies of prepulse inhibition of startle: normal subjects, patient groups, and pharmacological studies. Psychopharmacology. 2001;156:234–258. doi: 10.1007/s002130100810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geyer MA. The family of sensorimotor gating disorders: comorbidities or diagnostic overlaps? Neurotox. Res. 2006;10:211–220. doi: 10.1007/BF03033358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leussis MP, Bolivar VJ. Habituation in rodents: a review of behavior, neurobiology, and genetics. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2006;30:1045–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDiarmid TA, Bernardos AC, Rankin CH. Habituation is altered in neuropsychiatric disorders-A comprehensive review with recommendations for experimental design and analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017;80:286–305. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Groenman AP, Janssen TWP, Oosterlaan J. Childhood psychiatric disorders as risk factor for subsequent substance abuse: a meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2017;56:556–569. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walcott CM, Landau S. The relation between disinhibition and emotion regulation in boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2004;33:772–782. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3304_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lavezzi HN, Zahm DS. The mesopontine rostromedial tegmental nucleus: an integrative modulator of the reward system. Basal Ganglia. 2011;1:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.baga.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lammel S, Lim BK, Malenka RC. Reward and aversion in a heterogeneous midbrain dopamine system. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76:351–359. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lavezzi HN, Parsley KP, Zahm DS. Modulation of locomotor activation by the rostromedial tegmental nucleus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:676–687. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vento PJ, Burnham NW, Rowley CS, Jhou TC. Learning from one’s mistakes: a dual role for the rostromedial tegmental nucleus in the encoding and expression of punished reward seeking. Biol. Psychiatry. 2017;81:1041–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bourdy R, et al. Control of the nigrostriatal dopamine neuron activity and motor function by the tail of the ventral tegmental area. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:2788–2798. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown PL, et al. Habenula-induced inhibition of midbrain dopamine neurons is diminished by lesions of the rostromedial tegmental nucleus. J. Neurosci. 2017;37:217–225. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1353-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lorens SA, Kohler C, Guldberg HC. Lesions in Guddesn’s tegmental nuclei produce behavioral and 5-HT effects similar to those after raphe lesions. Pharm. Biochem. Behav. 1975;3:653–659. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(75)90187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vann SD. Gudden’s ventral tegmental nucleus is vital for memory: re-evaluating diencephalic inputs for amnesia. Brain. 2009;132:2372–2384. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Won H, et al. GIT1 is associated with ADHD in humans and ADHD-like behaviors in mice. Nat. Med. 2011;17:566–572. doi: 10.1038/nm.2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luo SX, et al. TGF-beta signaling in dopaminergic neurons regulates dendritic growth, excitatory-inhibitory synaptic balance, and reversal learning. Cell Rep. 2016;17:3233–3245. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richter MM, Ehlis AC, Jacob CP, Fallgatter AJ. Cortical excitability in adult patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Neurosci. Lett. 2007;419:137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moll GH, Heinrich H, Trott G, Wirth S, Rothenberger A. Deficient intracortical inhibition in drug-naive children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder is enhanced by methylphenidate. Neurosci. Lett. 2000;284:121–125. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(00)00980-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hermann B, et al. The frequency, complications and aetiology of ADHD in new onset paediatric epilepsy. Brain. 2007;130:3135–3148. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnston BA, et al. Brainstem abnormalities in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder support high accuracy individual diagnostic classification. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2014;35:5179–5189. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caye, A., Swanson, J. M., Coghill, D. & Rohde, L. A. Treatment strategies for ADHD: an evidence-based guide to select optimal treatment. Mol. Psychiatry24, 390–408 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Bedingfield JB, Calder LD, Karler R. Comparative behavioral sensitization to stereotypy by direct and indirect dopamine agonists in CF-1 mice. Psychopharmacology. 1996;124:219–225. doi: 10.1007/BF02246660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McNamara RK, et al. Dose-response analysis of locomotor activity and stereotypy in dopamine D3 receptor mutant mice following acute amphetamine. Synapse. 2006;60:399–405. doi: 10.1002/syn.20315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Del Campo N, Chamberlain SR, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW. The roles of dopamine and noradrenaline in the pathophysiology and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2011;69:145–157. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robbins TW, Arnsten AF. The neuropsychopharmacology of fronto-executive function: monoaminergic modulation. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2009;32:267–287. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bymaster FP, et al. Atomoxetine increases extracellular levels of norepinephrine and dopamine in prefrontal cortex of rat: a potential mechanism for efficacy in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:699–711. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Badgaiyan RD, Sinha S, Sajjad M, Wack DS. Attenuated tonic and enhanced phasic release of dopamine in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0137326. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sagvolden T, Russell VA, Aase H, Johansen EB, Farshbaf M. Rodent models of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;57:1239–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gainetdinov RR. Strengths and limitations of genetic models of ADHD. Atten. Defic. Hyperact. Disord. 2010;2:21–30. doi: 10.1007/s12402-010-0021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hess EJ, Collins KA, Wilson MC. Mouse model of hyperkinesis implicates SNAP-25 in behavioral regulation. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:3104–3111. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-09-03104.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Myers MM, Musty RE, Hendley ED. Attenuation of hyperactivity in the spontaneously hypertensive rat by amphetamine. Behav. Neural Biol. 1982;34:42–54. doi: 10.1016/S0163-1047(82)91397-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van den Bergh FS, et al. Spontaneously hypertensive rats do not predict symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Pharm. Biochem. Behav. 2006;83:380–390. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Calzavara MB, et al. Effects of antipsychotics and amphetamine on social behaviors in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2011;225:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bizot JC, et al. Methylphenidate reduces impulsive behaviour in juvenile Wistar rats, but not in adult Wistar, SHR and WKY rats. Psychopharmacology. 2007;193:215–223. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0781-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Del’Guidice T, et al. Dissociations between cognitive and motor effects of psychostimulants and atomoxetine in hyperactive DAT-KO mice. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231:109–122. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3212-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moon SJ, et al. Effect of atomoxetine on hyperactivity in an animal model of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e108918. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Levin R, et al. Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats (SHR) present deficits in prepulse inhibition of startle specifically reverted by clozapine. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2011;35:1748–1752. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ralph RJ, Paulus MP, Fumagalli F, Caron MG, Geyer MA. Prepulse inhibition deficits and perseverative motor patterns in dopamine transporter knock-out mice: differential effects of D1 and D2 receptor antagonists. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:305–313. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00305.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rodriguiz RM, Chu R, Caron MG, Wetsel WC. Aberrant responses in social interaction of dopamine transporter knockout mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2004;148:185–198. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(03)00187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ramos A, et al. Evaluation of Lewis and SHR rat strains as a genetic model for the study of anxiety and pain. Behav. Brain Res. 2002;129:113–123. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(01)00337-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goto SH, Conceicao IM, Ribeiro RA, Frussa-Filho R. Comparison of anxiety measured in the elevated plus-maze, open-field and social interaction tests between spontaneously hypertensive rats and Wistar EPM-1 rats. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 1993;26:965–969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Russell VA, Sagvolden T, Johansen EB. Animal models of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Behav. Brain Funct. 2005;1:9. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.