Abstract

The catabolic autophagy eliminates cytoplasmic components and organelles via lysosomes. Non‐selective bulk autophagy and selective autophagy (mitophagy) are linked in intracellular homeostasis both normal and cancer cells. Autophagy has complex and paradoxical dual role in cancers; it can play either tumour suppressor or tumour promoter depending on the tumour type, stage, microenvironment and genetic context. Cancer stem cells (CSCs) cause tumour recurrence and promote resistant to therapy for driving poor clinical consequences. Thus, new healing strategies are urgently needed to annihilate and eradicate CSCs. As chloroquine (CQ) analogues show positive clinical outcome in several clinical trials either standalone or combination with several chemotherapies. Moreover, CQ analogues are known to eliminate CSCs via altering DNA methylation. However, several obstacles such as higher concentrations and dose‐dependent toxicity are noticeable in the treatment of cancers. As tumour cells predominantly rely on mitochondrial actions, mitochondrial targeting FDA‐approved antibiotics are reported to effectively eradicate CSCs alone or combination with chemotherapy. However, antibiotics cause metabolic glycolytic shift in cancer cells for survival and repopulation. This review will provide a sketch of the inhibiting roles of current chloroquine analogues and antibiotic combination in CSC autophagy process and discuss the possibility that pre‐clinical and clinical potential therapeutic strategy for anticancer therapy.

Keywords: antibiotics, autophagy, chloroquine analogues, CSCs therapy, drug repurposing, mitochondrial target

Lists of main topics.

Autophagy is an emerging potential therapeutic target for multiple disorders including multiple malignant tumours. Autophagy has both suppression role in tumour initiation and promotion action in tumour progression, and this controversy role of autophagy has led to dilemma over whether or how targeting of autophagy therapeutically should be undertaken for efficient treatment of cancers.

Chloroquine analogues are established autophagy inhibitors from malaria treatment. When lysosomotropic action of chloroquine analogues is elucidated, these drugs have become popular for autophagy suppressors.

The clinical studies for chloroquine analogues are executed owing to their prior Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval and expanded indication in the treatment of inflammatory diseases.

Although pharmacokinetic parameters and safety profiles of chloroquine analogues are less favourable in cancer patients, combination treatment data are emerging.

Maintenance of cancer stem cells (CSCs) is associated with the endosome/lysosome pathway, and propagation and clonal expansion of CSCs are dependent on mitophagy. Thus, the pharmacological inhibition of lysosomal flux and mitochondrial biogenesis may effectively block CSCs.

1. INTRODUCTION

Cancer becomes the principal originator of morbidity and mortality rates in the next few years in both developed and transitioning economy countries. 1 , 2 , 3 The scientific society has given enormous struggles and endeavour to advance innovative strategies for cancer therapy to deal efficiently with this uprising and complicating issue. Although the advanced cancer therapies are progressing from the survival rate of patients, cancer still persists one of the most fatal epidemic maladies. Cancer recurrence and metastatic progression are frequent in patients receiving conventional chemotherapy or radiotherapy. 4 As contemporary chemotherapeutics are most efficient for eliminating very quickly propagating cells, the failure rate of conventional therapies is likely associated with a relatively rare slowly proliferating culture of cancer cells stay in tumour, called cancer stem cells (CSCs). 5 , 6 CSCs have been exhibited to be resistant to traditional chemotherapy as well as radiation. 7 Residual memory CSCs disappeared after clinical treatment are suggested responsible for the re‐survival of tumours and for their progressive metastasis. 8 It has also been suggested that the most metabolic active CSCs have heightened biogenetic rate of mitochondria as compared to normal cell correspondents. 9 , 10 Thus, a great attempt has been concerned to the new drug development that is capable to correctly target biogenesis of mitochondria‐associated CSCs.

The conventional drug discovery and development process are an indeed challenging field in terms of rising and unsustainable costs, and time‐exhausting tasks, with a high frequency of failure rate. 11 Thus, pharmaceutical companies have decided to decrease annual investment regarding classical drug discovery 12 and healthcare systems have faced the substantial challenge in their survival for commercial sustainability inflamed by paying of prescription drugs. 13 In this context, drug repurposing (new therapeutic uses or indications are found for existing drugs) appears as a new platform for the pharmaceutical industries, patients and healthcare payers. 14 , 15 Moreover, drug repositioning (also called drug repurposing) approach may conquer many tremendous obstacles involved in new drugs discovery because of having established pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and toxicity profiles, approval by several regulatory agencies FDA (US) and EMEA (Europe), and these recognitions accelerate the assessment of the agents in clinical trials. 16 , 17 Furthermore, drug repurposing may discover novel molecular regulatory pathways involved in cancer regrowth or admit new molecular targets for cancer therapy. 18 It has been exemplified that repurposing drugs chloroquine (CQ) analogues and antibiotics are known to accelerate the therapeutic capacity of chemotherapy by eliminating CSC traits of invasive progression in tumours. 19 , 20 Thus, repurposing drugs play an important role to eradicate CSC‐mediated tumorigenesis.

2. ROLE OF BULK AUTOPHAGY IN CANCER

Macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy) is an evolutionarily conserved, cellular homeostatic process that facilitates nutrient recycling via lysosomal degradation of potentially harmful cytoplasmic entities. 21 , 22 It has been widely established that the bipolar nature of autophagy exists in cancers. 23 , 24 Autophagy act as either tumour suppressor or tumour promoter depending on tumour type, stage of tumour development, tumour microenvironment and genetic context. 25 , 26 Although autophagy limits cancer development in the early stages of tumorigenesis, it can also have a pro‐tumoral role in more advanced cancers, promoting primary tumour growth and metastatic spread. 25 Under normal conditions, cells utilize basal levels of autophagy to aid in the maintenance of biological function, homeostasis, quality control of cell contents and elimination of old proteins and damaged organelles. 27 Additionally, autophagy in stem cells is related to the maintenance of their unique properties, including differentiation and self‐renewal. 28 , 29 However, many established malignant cells have high levels of basal autophagy even in fed conditions. 30 , 31 In contrast, autophagy in normal cells generally occurs at low levels and is only up‐regulated in response to stressful conditions such as starvation. Moreover, some anticancer drugs can regulate autophagy. Therefore, autophagy‐regulated chemotherapy can be involved in cancer‐cell survival or death. 32 Additionally, the regulation of autophagy contributes to the expression of tumour suppressor proteins or oncogenes. Tumour suppressor factors are negatively regulated by mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) resulting in the induction of autophagy and suppression of the cancer initiation. 33 In contrast, oncogenes may be activated by mTOR, class I PI3K (phosphoinositide 3‐kinases) and AKT (also known as protein kinase B), resulting in the suppression of autophagy and enhancement of cancer formation. 25 , 34 Although these dual‐complex mechanisms make autophagy a challenging target for anticancer therapeutics, a better understanding of the autophagic roles in different stages of tumorigenesis, specific cellular and extracellular context and the crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis should all be taken into consideration to better harness autophagy in cancer treatment. 35

Interestingly, an intricate link between autophagy and cancer is established when Beclin 1 (BECN1), an essential autophagy gene, is found to suppress breast tumorigenesis. 36 , 37 In several cancer‐cell lines and mice models, the loss of BECN1 results in an inhibition of autophagy and an upsurge in cell proliferation. 36 , 38 , 39 In addition, the BECN1 gene is monoallellicaly deleted in 40%–75% of breast, ovarian and prostate cancers. 36 , 40 , 41 It is also found that the overexpression of Beclin 1 can inhibit the growth of colon cancer cells, 42 nasopharyngeal carcinoma 43 and CaSki cervical cancer cells. 44 Due to the genomic close proximity of the BRCA1 (breast cancer 1, early‐onset gene) and the BECN1 gene at the 17q21 chromosome, it was assumed that BECN1 deletions are rather a passenger event. 45 Tumour suppressor gene deletions require additional modulators to form cancer. In human breast and ovarian cancers, BECN1 is often co‐deleted with BRCA1. This led to the hypothesis that BECN1 loss is a passenger event and is only deleted due to its proximity to BRCA1. 45 , 46 BRCA1 is frequently mutated in familial cases of breast and ovarian cancer, being relatively rare in sporadic cancers, and it is a classical tumour suppressor, as only one copy is sufficient to maintain its function. By contrast, the loss of just one allele of BECN1 is sufficient to induce tumorigenesis, 38 , 39 and therefore, it is suggested as a haploinsufficient tumour suppressor. Furthermore, two survival analyses on the TCGA (Cancer Genome Atlas Project) and METABRIC (Molecular Taxonomy of Breast Cancer International Consortium) data set showed that a worse survival probability was associated with the lower BECN1 but not with the BRCA1 mRNA expression in all breast cancer types, 47 indicating that in sporadic breast cancers, BECN1 is a driver rather than a passenger event.

Autophagy also maintains cancer‐cell re‐survival during metabolic stressful conditions, and these mediate resistance to therapies such as chemotherapies or radiation. 48 , 49 Thus, induction of autophagy in cancer cells is associated with stress tolerance mechanism when these cells are experienced to nutrient starvation, hypoxic conditions or anticancer therapies. 50 , 51 , 52 In well‐established tumours, the stress‐induced autophagy allows tumour cell regrowth which in turn expedite tumour cell advancement and negotiate resistance to anticancer therapies. 53 As a result, inhibiting pro‐survival (cytoprotective) autophagy in cancer cells has been shown to augment the effectiveness of anticancer therapy by promoting apoptotic cell death. 54 , 55 Although these dual‐complex mechanisms make autophagy a challenging target for anticancer therapeutics, a better understanding of the autophagic roles in stages of tumorigenesis, specific cellular and extracellular context and the crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis should all be taken into consideration to better harness autophagy in cancer treatment. Although autophagy modulation has promised as an emerging therapeutic strategy for certain cancer types, major challenges remain unclear. For examples, higher chemotherapy doses may cause toxic side effects and it is contradiction whether autophagy‐modulating agents may significantly affect the tumour cells. Furthermore, there is doubt existence about an actual tissue‐derived autophagy measurement, especially inaccessible in solid tumours. 18 , 56 Therefore, a better intervention of chemotherapeutic combination is required for modulation of inherent autophagy properties. Thus, treatment strategies of cancers that modulate autophagy both inducing and inhibiting concomitantly emphasize a better understanding for improved therapeutic outcome.

2.1. Targeting lysosome in autophagy by chloroquine analogues

Chloroquine (CQ) analogues such as hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), quinacrine (QN), mefloquine (MQ), Lys05, verteporfin, clioquinol SAR405, spautin‐1 (specific and potent aut phagy inhibitor 1), ARN5187, VATG (Van Andel‐T‐Gen)‐027 and VATG‐032 and its other derivatives are well‐known repurposing success stories because these analogues are effective, inexpensive, well‐tolerated in humans. 57 , 58 CQ analogues, for example HCQ, MQ and verteporfin, are FDA‐approved agents generally applied for the treatment of malaria, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis and photodynamic therapy, but their potentials as anticancer agents have currently appeared. 57 As lysosomotropic agents, CQ analogues efficiently deacidify lysosomal lumens by changing permeability of lysosomal membrane potential (LMP). 59 Accumulating lines of evidence suggest that CQ analogues favourably induce apoptosis and necrosis in cancer cells such as breast cancer, colon cancer, glioma and glioblastoma compared with normal cells either in standalone or in combinations with chemotherapy. 53 , 60 In the context, it has been found that CQ analogues have direct actions on diverse kinds of cancers that influence chemotherapeutic actions, for example inhibition of both multidrug resistance pump and autophagy, intercalation in DNA and improving the penetration of chemotherapies in cancer cells or solid tumour tissues. 61 , 62 In these cases, the lysosome‐deacidifying property of CQ analogues seems the most vital parameter for improving efficacy and specificity for cancer therapies.

CQ analogues also sensitize triple‐negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells, categorized by a plenty of chemotherapy‐resistant breast cancer stem cells (CSCs) as well as chemotherapy‐resistant pancreatic CSCs to where CQ analogues efficiently prevent autophagy. 62 , 63 , 64 Thus, CQ analogues need to be more discovered in the scientific background as their victory may benefit to further quickly progress the poor diagnosis of patients with TNBC or pancreatic cancer. Interestingly, recent evidence suggests that HCQ in combination treatment with mTOR inhibitors such as temsirolimus significantly suppresses tumour growth in vitro and in vivo. 65 , 66 Here the period of treatment and acceptable dose of HCQ differentially affect medical profits (best outcome achieved with 1200 mg HCQ twice daily). Another clinical trial (phase 1 study) HCQ (600 mg) in blending with temozolomide (TMZ) indicates suppression of autophagy in humans. However, an increased dose of HCQ is indispensable for noticeable clinical outcome. 67 Moreover, CQ also potentiates the cytotoxic effect of TMZ by inhibiting mitophagy in glioma cells. 68 These reports strongly suggest that CQ analogue in combination with other autophagy‐modulating agents may significantly improve cancer treatment regimen if robust and rapid treatment strategies are necessary. More importantly, there are numerous concurrent clinical trials assessing CQ analogues in combination with chemotherapies in patients with multiple cancers. 53 However, there are many highly debatable questions remaining as these analogues denote the most efficient agents for suppressing autophagy. For example, (a) the analogues may be required higher concentrations (µM levels) to attain adequate inhibition of autophagy in vitro and in vivo which is inconsistently achievable in humans than conventionally used for malaria and rheumatic disorders. 69 Accordingly, HCQ combination with chemotherapeutic agents, proteasomal inhibitors, mTOR inhibitors and/ or radiation therapy has been revealed to outcome in little response rates in the initial clinical trials. Furthermore, the higher doses of HCQ used in clinical trials produce significant interpatient variability of autophagy inhibition. In addition, the half‐lives of the analogues account for long times (eg 22.4 days for HCQ), which account for the chronic side effects, including retinopathy. 59 As sustained autophagy induction and autophagy addiction are inimitable to cancer cells, supposedly long‐term autophagy inhibition can provide a healing window to favourably affect cancer cells. However, higher maintenance of HCQ dose in a cancer patient will unavoidably affect normal cells too; (b) CQ analogue unable to suppress autophagy in acidic extracellular microenvironment (pH 6.5) in solid tumour due to reduced cellular uptake of the agents 70 ; (c) some clinical trials have revealed dose‐dependent toxicities such as neutropaenia, thrombocytopaenia and sepsis when HCQ is given in combination therapy 71 ; and (d) finally, CQ‐associated chemo‐sensitization to chemotherapy seems to be an autophagy‐independent occurrence. 72 These data strongly support a necessity to investigate better therapeutic strategy with specific molecular mechanism in modulating of autophagy in cancers. Further research will be required to identify and develop for additional effective and acceptable CQ analogues as autophagy suppressors, as well as outline the prime dose and dose interval that leads to highest the therapeutic activity during cancer therapy. However, the successful drug repositioning approach has primarily been by serendipitous discovery or clinical observation, such as the rich history and serendipitous indications for chloroquine 59 (Table 1 and Figure 1 ). Thus, scientists from the repurposing drugs in oncology (ReDO) project highlighted the potentiality of CQ analogues for cancer treatment by acting on both the cancer cellular level and the tumour niches and suggested that these analogues could propose important clinical advantages for cancer patients, particularly in combination with conventional anticancer treatments.

Table 1.

Key serendipitous events in the history of CQ analogue development that led to the successful targeting of autophagy in cancer

| Year | Major discovery/events |

|---|---|

| Before 1532 | Quina‐quina bark is indigenously used in South America to treat febrile illness |

| 1632 | Quina‐quina bark is used to treat for 'tertian fever' in Peru; Jesuit priest Bernabe’ de Cobo transported from Peru to Europe (Spain) |

| 1629‐1633 | The Romantic legend of Countess of Chinchon cured with quina‐quina bark |

| 1600‐1700 | Quina‐quina bark powder is well‐spreading throughout Europe and Asia for febrile illness |

| 1742 | Quina‐quina tree is renamed as Cinchona tree by the botanist Carolus Linnaeus |

| 1818 | Quinine isolated from cinchona tree bark; found to be useful for the treatment of malaria |

| 1894 | Dr JF Payne's first description of the use of high doses of quinine to treat lupus. |

| 1908 | Quinoline nuclear structure is essential for antimalarial activity. |

| 1920 | Pamaquine is the first synthetic antimalarial drug |

| 1930 | Quinacrine is developed as an alternative to quinine to treat malaria |

| 1931 | Quinacrine is synthesized Ehrlich group and clinical trial |

| 1934 | Hans Andersag at Bayers Lab, synthesized Resochin by replacing the acridine ring of quinacrine with a quinoline ring |

| 1939 | Resochin is renamed as chloroquine; CQ is seemed too toxic for human use |

| 1940 | Quinacrine is used in Russia for lupus |

| World War II | British physicians noted soldiers who had inflammatory diseases improved on quinacrine |

| 1945 | HCQ is synthesized, less toxic than CQ in animal models. Clinical trials in USA approved for human use |

| 1946 | FDA‐approved CQ for treatment of malaria |

| 1951 | Remarkable effects of quinacrine in the treatment of lupus |

| 1955 | Plaquenil (hydroxychloroquine sulphate) is FDA‐approved to treat SLE and CLE lupus. |

| 1956 | CQ improves inflammation in RA |

| 1959 | Triquin (HCQ, chloroquine and quinacrine combination) is FDA‐approved to treat lupus |

| 1960 | CQ shows anticancer properties |

| 1970 | As a lysosomotropic agent, CQ is first shown to inhibit cell growth of tumour in vitro, as indicated by the accumulation of autophagic vacuoles. |

| The early 1970s | Banned clioquinol in response to controversy association with subacute myelo‐optic neuropathy (SMON) in Japan |

| 1972 | FDA‐approved for Triquin withdrawn and is pulled off the market |

| 1974 | CQ withdrawn from Japanese market because of mistaken claim as subacute myelo‐optico‐neuropathy (SMON) and retinopathy due to improper use with poor safety management |

| 1980‐90 | CQ analogs are investigated as autophagy inhibitors in vitro |

| 1989 | The first observation that CQ has an anticancer effect in Burkitt's lymphoma when CQ was given as prophylaxis against malaria in Tanzania |

| 1998 | The first study to observe CQ as autophagy inhibitor; the link between accumulation of cellular proteins and the inhibition of lysosomal degradation |

| 2000 | HCQ shows anticancer properties |

| 2003 | First clinical trial to evaluate the antitumour effects of CQ and found that CQ improved clinical outcome with autophagy inhibition in glioblastoma. |

| 2007 | In combination with anticancer drugs, CQ has a synergistic effect with other anticancer drugs |

| 2009 | HCQ is launching in Japan for clinical care |

| 2010‐ | CQ analogs and current research: bone diseases, cancers, hyperglycaemia, emerging viral infectious diseases (AIDS, SARS, dengue) |

| 2014‐ | HCQ in clinical trials: Multiple groups published results from phase I/II clinical trials using HCQ to selectively target autophagy in cancer patients |

| 2017‐ | CQ overcome resistance: Autophagy inhibition can overcome resistance to kinase inhibitors in tumour cells and in patients |

| 2018‐2020 | Microencapsulated CQ analogues for targeting CSCs 50 , 66 |

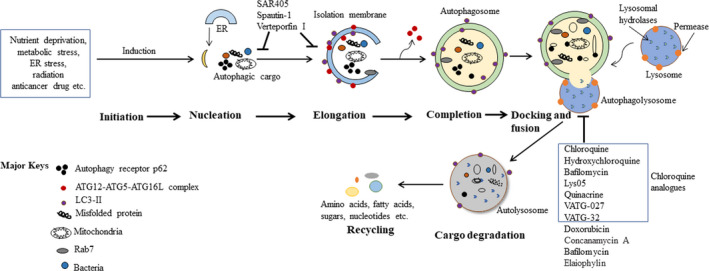

Figure 1.

An overview of mammalian autophagy process. Starvation, growth factor deprivation, low energy and hypoxia are well‐established autophagy (specifically, macroautophagy) inducers. These culminate in mTORC1 inhibition and AMPK (5' AMP‐activated protein kinase) activation, which, in turn, positively regulate the UNC51‐like kinase 1 (ULK1) complex through a series of phosphorylation events. Induction of the ULK1 complex subsequently activates the class III PI3K complex, which leads to PI3P (phosphatidylinositol 3‐phosphate) synthesis in isolation membranes (IMs) and initiates autophagy. Numerous molecular events are subsequently activated in the autophagy pathway, including initiation, nucleation, elongation, autophagosome maturation and cargo degradation. The IMs appear to have several sources, such as the ER membrane, Golgi apparatus and trans‐Golgi network, plasma membrane, endosomal compartment and mitochondria. The two ubiquitin‐like conjugation systems AuTophaGy‐related 12 (ATG12)‐ATG5‐ATG16L1 complex and LC3 (microtubule‐associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3B)‐II participate after their activation in the expansion of the double membrane and the closure of the isolation membrane. Once it is completed, the structure is called an autophagosome. After elongation and closure, the newly formed autophagosome may fuse with a late endosome to form an amphisome, or it may fuse directly with a lysosome to form an autolysosome, allowing the degradation of autophagic substrates. Once the cargos are degraded, the product macromolecules are exported to the cytosol to be recycled by the cell for ATP production and biosynthesis

3. ROLE OF MITOPHAGY IN CANCER

Mitophagy (mitochondrial autophagy) is the selective identification, degradation and removal of spoiled mitochondria at the autophagolysosome. 73 Mitophagy definitely varies from non‐selective bulk autophagy due to its selectivity and regulation of the autophagic cargo. 74 Mitochondrial autophagy is co‐ordinately related to cellular homeostasis that responds to extracellular deviations (eg stress, energy, nutrients). On the one hand, autophagosome formation occurs at the junction of mitochondria with endoplasmic reticulum upon the stimulation of autophagy initiation. In this process, mitochondria participate from the outer mitochondrial membrane lipids to nascent isolation membrane of autophagosomes. 75 , 76 On the other hand, autophagy donates mitochondria maintenance by regulation of mitochondrial integrity, which may also be related to regulatory higher living processes. 77

Mitophagy is triggered by stresses, DNA damage, inflammation, etc, and is an important mechanism for quality control of cellular bioenergetics and homeostasis by preserving mitochondrial integrity and actions. 78 Any imperfections in mitophagy lead to mitochondrial dysregulation that changes metabolic pathways and alters cell fate which in turn initiates the incidence and aetiology of diseases, including cancer. 79 , 80 , 81 Thus, both non‐selective bulk autophagy and selective mitophagy are impacted during tumorigenesis. Based on the type and stage context of the tumour, mitophagy may act either tumour‐promoting or tumour‐suppressive action. 80 , 82 Knockout of the vital regulatory mitophagy gene PARK2 has been associated with several dissimilar human tumours, for example, TNBC. 83 In addition, spontaneous hepatic tumour develops in mitophagy gene Parkin knockout mice which support mitophagy as a tumour‐suppressive mechanism. 82 On the other hand, established tumours have been anticipated to employ mitophagy for supporting tumour growth under stress conditions. 80

During initiation of tumour, mitochondria perform a main role in supplying nutrients essential for boosted cell propagation and angiogenesis. 74 In addition, mitochondria contribute several events of cancers such as apoptosis resistance, oncogene‐associated transformation, reprogramming of metabolism, translation of protein, stemness of cancer, malicious repopulation and drug resistance. 84 , 85 , 86 These solid foundation and proof‐of‐concept results strongly support the fact that mitochondria act as a fundamental metabolic centre vital for tumorigenesis. Thus, mitophagy mechanisms such as bioenergetics, biogenesis and cellular transductions of tumorigenesis have drawn the great attention for designing superb anticancer therapeutics.

3.1. Targeting mitophagy by antibiotics

Recent evidence suggests that CSCs are reliant on mitophagy pathways for their proliferation and clonal development, and pharmacological inhibition of mitochondrial biogenesis may effectively block CSCs. 9 , 10 , 87 , 88 , 89 It is evident that various FDA‐approved agents particularly antibiotics modulate mitochondrial protein synthesis in mammalian cells as off‐target effects from its original antimicrobial use. 90 , 91 , 92

Based on in vitro substitute CSC assays, numerous classes of FDA‐approved antibiotics including erythromycins (azithromycin), glycylcycline (tigecycline), tetracyclines (doxycycline), fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin) and atovaquone (chloroquine analogues) have been found to markedly reduce tumorsphere development in several cancer cells including breast, lung, prostate and PDAC. 92 , 93 For instance, tigecycline selectively kills CSCs of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) by suppression of mitochondrial translation. 94

Azithromycin in combination with chemotherapy (paclitaxel and cisplatin) shows a positive response of one‐year survival of stage III/IV non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. 95 Salinomycin selectively inhibits CSCs by impairing mitochondrial bioenergetic performance. 96 Atovaquone performs as an oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) inhibitor and significantly inhibits sphere formation in breast and colorectal CSCs without affecting normal fibroblasts. 97 Pyrvinium pamoate, an anti‐parasitic agent, behaves as an OXPHOS inhibitor aiming mitochondrial complex II and competently stops mammosphere production. 98 Doxycycline binds preferentially to the small subunit 28S ribosomes in mitochondria and erythromycin metabolites or chloramphenicol specifically fix to the mitochondrial ribosome large subunit 39S, thereby blocking biogenesis of mitochondria and thereby preventing protein translation as well as sufficient reduction in mammosphere production and bonafide CSC markers. 98 Thus, it is interesting that FDA‐approved antibiotic‐mediated mitochondria targeting may contribute to eradicate cancer cells particularly CSCs and the anticancer efficacies of the antibiotics (Table 2).

Table 2.

Major drugs targeting the lysosome in autophagy and mitophagy in cancer

| Agent | Derivative | Water solubility | BBB permeability | Autophagy‐related mechanism of action | Target stage of autophagy | Therapeutic uses | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fusion and cargo degradation stages of autophagy | |||||||

| Chloroquine | Aminoquinolines | Soluble | Permeant | Inhibition of lysosomal acidification | Fusion and degradation | Approved for malaria | Non‐specific inhibition of lysosomal functions |

| Hydroxychloroquine | Aminoquinolines | Soluble | Permeant | Inhibition of lysosomal acidification | Fusion and degradation | Approved for malaria, SLE and RA | Non‐specific inhibition of lysosomal functions |

| Quinacrine | Acridine | Soluble | Permeant | Inhibition of lysosomal acidification | Fusion and degradation | Accepted not established female sterility | Non‐specific inhibition of lysosomal functions |

| Mefloquine | Quinoline | Soluble | Permeant | Inhibition of lysosomal acidification | Fusion and degradation | Approved for malaria | Non‐specific inhibition of lysosomal functions |

| Quinine | Quinoline | Soluble | Permeant | Inhibition of lysosomal acidification; K+ ATP channel blockers | Fusion and degradation | Approved for malaria | Non‐specific inhibition of lysosomal functions |

| Lys05 | Aminoquinolines | Soluble | Unknown | Inhibition of lysosomal acidification | Fusion and degradation | Pre‐clinical, cancer | Non‐specific inhibition of lysosomal functions |

| ARN16090 | ARN5187 analog | Insoluble | Unknown | Inhibition of lysosomal acidification | Fusion and degradation |

Pre‐clinical cancer |

Also inhibition of NR1D2/REV‐ERBβ |

| VATG‐027 | 1,2,3,4tetrahydroacridine | Insoluble | Unknown | Inhibition of lysosomal acidification | Fusion and degradation |

Pre‐clinical cancer |

More potent autophagy inhibition than CQ |

| Clioquinol ionophore | 8‐hydroxyquinoline | Insoluble | Unknown | Inhibition of lysosomal acidification | Fusion and degradation | Approved skin and urinary infections | Autophagy induction by disruption catalytic activity of mTOR |

| Bafilomycin A1 | Macrolide antibiotic | Insoluble | Permeant | Lysosomal V‐ATPase inhibition | Fusion and degradation | Experimental agent | Universal V‐ATPase inhibitor (eg osteoclast, cancers) |

| Concanamycin A | Plecomacrolide antibiotics | Insoluble | Permeant | Lysosomal V‐ATPase inhibition | Fusion and degradation | Pre‐clinical for cancer | Universal inhibitor (eg osteoclast) |

| Archazolid | ‐ | Soluble | Unknown | Lysosomal V‐ATPase inhibition | Fusion and degradation | In vitro studies; a myxobacterial agent | Reduction in cathepsin B activity |

| Doxorubicin (Adriamycin) | Anthracycline antibiotic | Soluble | Impermeable | Lysosomal V‐ATPase suppression | Fusion and degradation | Approved for leukaemias, Hodgkin's lymphoma | Universal V‐ATPase inhibitor |

| Manzamine A | Manzamine alkaloid | Soluble | Unknown | Lysosomal V‐ATPase inhibition | Fusion and degradation | Pre‐clinical | v‐ATPase inhibition is similar to bafilomycin A |

| Cleistanthin‐A | Diphyllin glycoside | Soluble | Unknown | Lysosomal V‐ATPase inhibition | Fusion and degradation | In vitro studies | ‐ |

| Pepstatin A | Hexapeptide metabolite | Insoluble | Unknown | Lysosomal Aspartyl protease inhibitor |

Partial Degradation (lysosomal proteolysis) |

Not registered | A reversible non‐specific inhibitor |

| Leupeptin | Peptide antibiotic | Soluble | Permeant | Lysosomal protease and Ca2+‐dependent calpain inhibitor |

Partial degradation (lysosomal proteolysis) |

Not registered | A reversible non‐specific inhibitor |

| E64d | Fungal metabolite | Insoluble | Unknown | Lysosomal cysteine protease inhibitor |

Partial degradation (lysosomal proteolysis) |

Not registered | An irreversible non‐specific inhibitor |

| Elaiophylin | Macrodiolide antibiotic | Poorly soluble | Unknown | Abrogation of maturation of cathepsin B and D. | Degradation | Antibacterial and anthelminthic activities | Promotion of autophagosome accumulation |

| Nucleation and elongation stages of autophagy | |||||||

| Spautin‐1 | MBCQ | Insoluble | Unknown | Inhibition of USP10 and USP13 that target deubiquitination of Beclin 1 | Nucleation |

Pre‐clinical cancers |

Inhibition of autophagy in a Beclin‐1‐independent manner |

| SAR405 | ‐ | Insoluble | Unknown | Inhibition of Vps34 | Nucleation |

Pre‐clinical cancer |

High protein and lipid kinase selectivity profile |

| Verteporfin | Benzoporphyrin | Insoluble | Permeant | Inhibition of LC3 lipidation | Elongation | Approved as PDT for macular degeneration and histoplasmosis | Autophagy inhibition independently of light |

4. TARGETING LYSOSOME IN AUTOPHAGY AND MITOPHAGY BY CHLOROQUINE ANALOGUE AND ANTIBIOTICS

It has been found that CQ analogues at low concentration suppress bone resorptive activity of osteoclasts without affecting bone‐forming cells, 99 and subtherapeutic antibiotic treatment (STAT) causes an increase in bone mineral density. 100 Thus, combination of chloroquine analogues and mitochondrial‐targeted agents in subtherapeutic level (at low concentration) would be more therapeutic potentials against CSC‐related cancers and revolutionize the cancer research field without affecting normal cells.

5. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVE

According to the vast evidence on in vitro and mammalian/ animal models, it is expected to find positive impacts of the combination as a cancer therapy by manipulating the capacity of lysosome in autophagy‐mitophagy process in CSCs. Also, it is expected to discover the molecular mechanisms of therapeutic pathways in inhibition of CSCs without affecting severely in vital organs. Further studies are required at the subcellular levels of cancers for saving global people. At present, several non‐selective bulk autophagy inhibitors and selective mitophagy suppressors undertake in clinical trials (phases I and II) in which these agents are exploited together with a diversity of chemotherapeutic drugs in cancer treatments (Table 3). It is predicted that such type of combinatory autophagy inhibitors with understanding of the molecular regulatory mechanism of the autophagy will direct to certain revolution in the treatment of multiple human diseases including cancer in the near future.

Table 3.

Ongoing clinical studies using the autophagy inhibitors CQ analogs in cancer treatment

| Treatment strategy | Disease |

Trial phase/ Status |

Primary end‐point | Identifier | Sponsor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor | Other agents | |||||

|

CQ (Aralen) |

None | Lung cancer | 1/C | Safety | NCT00969306 | Maastricht Radiation Oncology |

| Breast cancer | 2/R | Safety | NCT02333890 | Ottawa Hospital Research Institute | ||

| Carboplatin + gemcitabine | Malignant neoplasm | 1/R | Safety | NCT02071537 | University of Cincinnati | |

| Taxane | Breast neoplasms | 2/R | Safety | NCT01446016 | The Methodist Hospital System | |

|

HCQ (Plaquenil) |

‐ |

Solid tumour | 1/R | Safety | NCT03015324 | University of Kentucky |

| Solid tumour | 1/R | Safety | NCT02232243 | University of Kentucky | ||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 1 /2/R | Safety | NCT02013778 | University of Pennsylvania | ||

| Itraconazole | Ovarian cancer | 1/2/R | Safety | NCT03081702 | University Health Network | |

| Mitoxantrone + etoposide | Leukaemia, acute myelogenous | 1/R | Safety | NCT02631252 | University of Pittsburgh | |

| IL‐2 | Metastatic renal cell carcinoma | 1/2/R | Safety | NCT01550367 | University of Pittsburgh | |

| Vorinostat | Malignant solid tumour | 1/R | Safety | NCT01023737 | Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. | |

| Vorinostat + regorafenib | Colorectal cancer | 2/R | Safety | NCT02316340 | The University of Texas Health Science | |

| Gemcitabine + Nab‐paclitaxel | Pancreatic cancer resectable | 2/R | Safety | NCT03344172 | Pfizer, NCI | |

| Gemcitabine | Metastatic adenocarcinoma | 1/2/R | Safety | NCT01506973 | University of Pennsylvania | |

| Trametinib | Advanced BRAF mutant melanoma | 1/2/R | Safety | NCT02257424 | University of Pennsylvania | |

| Everolimus | Breast cancer stage IIB | 2/R | Safety | NCT03032406 | University of Pennsylvania | |

| Gemcitabine + carboplatin+ +etoposide | Small cell lung cancer | 2/R | Safety | NCT02722369 | University College, London | |

| QC | Capecitabine | Colorectal adenocarcinoma |

1 /2 ANT |

Safety | NCT01844076 | Milton S. Hershey Medical Center |

| ‐ | Prostatic cancer | 2/C | Safety | NCT00417274 | Cleveland BioLabs | |

| Erlotinib | Recurrent NSCLC | 1/C | Safety | NCT01839955 | Case Comprehensive Cancer Center | |

| VP | ‐ | Recurrent prostate cancer | 1/R | Safety | NCT03067051 | Princess Margaret Cancer Centre |

| ‐ | Breast neoplasms | I/II/R | Safety | NCT02872064 | University College, London | |

| ‐ | Pancreatic cancer | 2/R | Safety | NCT03033225 | Mayo Clinic | |

| Cisplatin | Pleural effusion, malignant | 1/R | Safety | NCT02702700 | Centre Hospitalier Universitaire | |

| CLQ | ‐ | Leukaemia lymphoma, myeloma | 1/T | Safety | NCT00963495 | University Health Network |

| CM | Docetaxel, cabazitaxel | Prostate cancer | 1/R | NCT03043989 | Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center | |

| Lenalidomide | Lymphoma | 2/R | NCT03031483 | IELSG | ||

| Dexamethasone + ixazomib +pomalidomide | Myeloma | 1/2/R | Safety | NCT02542657 | University of California | |

| Lenalidomide + dexamethasone | Relapse multiple myeloma | 2/R | Safety | NCT02986451 | Sun Yat‐sen University | |

| Thalidomide + cyclophosphamide +dexamethasone | Multiple myeloma | 3/R | Safety | NCT02248428 | Jinling Hospital, China | |

| Pioglitazone nivolumab treosulfan | Lung cancer, NSCLC | 2/R | Safety | NCT02852083 | University Hospital Regensburg | |

| Lenalidomide dexamethasone | Multiple myeloma | 3/R | Safety | NCT02516696 | Weill Medical College of Cornell University | |

| CF | Neupogen | Early‐stage breast cancer | 4/R | Safety | NCT02816112 | Ottawa Hospital Research Institute |

| Col | ‐ | Hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis invasion | 2/R | NCT01935700 | Kaohsiung Medical University Chung‐Ho Memorial Hospital | |

ANT, Active, not recruiting; C, completed; CF, ciprofloxacin; CF, ciprofloxacin; CLQ, clioquinol; CM, clarithromycin; CM, clarithromycin; Col, colchicine; CQ, chloroquine; Dox, doxorubicin; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; LT, lucanthone; MBCQ, [4‐((3,4‐methylenedioxybenzyl)amino)‐6‐chloroquinazoline]; NCI, national cancer institute; NSCLC, non‐small cell lung cancer; QC, quinacrine; R, recruitment; S, suspended; T, terminated; VP, verteporfin.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares that there are no known competing financial interests or personal relationship that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Md. Abdul Alim Al‐Bari: Writing‐review & editing (equal).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Professor Dr Paul A Townsend, University of Manchester, for technical support of this manuscript.

Al‐Bari MAA. Co‐targeting of lysosome and mitophagy in cancer stem cells with chloroquine analogues and antibiotics. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:11667–11679. 10.1111/jcmm.15879

REFERENCES

- 1. Fidler MM, Soerjomataram I, Bray F. A global view on cancer incidence and national levels of the human development index. Int J Cancer. 2016;139:2436‐2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fidler MM, Gupta S, Soerjomataram I, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality among young adults aged 20–39 years worldwide in 2012: A population‐based study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1579‐1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bray F, Jemal A, Grey N, et al. Global cancer transitions according to the human development index (2008–2030): A population‐based study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:790‐801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Janku F, McConkey DJ, Hong DS, et al. Autophagy as a target for anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:528‐539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Duggal R, Minev B, Geissinger U, et al. Biotherapeutic approaches to target cancer stem cells. J Stem Cells. 2014;8:135‐149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brooks MD, Burness ML, Wicha MS. Therapeutic implications of cellular heterogeneity and plasticity in breast cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:260‐271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vlashi E, Pajonk F. Cancer stem cells, cancer cell plasticity and radiation therapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2014;31:28‐35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dawood S, Austin L, Cristofanilli M. Cancer stem cells: Implications for cancer therapy. Oncology (Williston Park). 2014;28(1101–1107):1110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lamb R, Harrison H, Hulit J, et al. Mitochondria as new therapeutic targets for eradicating cancer stem cells: Quantitative proteomics and functional validation via mct1/2 inhibition. Oncotarget. 2014;5:11029‐11037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. De Luca A, Fiorillo M, Peiris‐Pages M, et al. Mitochondrial biogenesis is required for the anchorage‐independent survival and propagation of stem‐like cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:14777‐14795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. DiMasi JA, Grabowski HG, Hansen RW. Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: New estimates of r&d costs. J Health Econ. 2016;47:20‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. The Pharmaceutical Journal . Return on investment falls for pharmaceutical industry. 2017. 10.1211/PJ.2017.20202146 [DOI]

- 13. Aitken M, Kleinrock M. Global medicines use in 2020: outlook and implications. IMS Institute for healthcare informatics. 2020;2015:1‐4. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hernandez JJ, Pryszlak M, Smith L, et al. Giving drugs a second chance: Overcoming regulatory and financial hurdles in repurposing approved drugs as cancer therapeutics. Front Oncol. 2017;7:273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abbruzzese C, Matteoni S, Signore M, et al. Drug repurposing for the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36:169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Galluzzi L, Bravo‐San Pedro JM, Blomgren K, et al. Autophagy in acute brain injury. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17:467‐484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ashburn TT, Thor KB. Drug repositioning: Identifying and developing new uses for existing drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:673‐683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vazquez‐Martin A, Lopez‐Bonetc E, Cufi S, et al. Repositioning chloroquine and metformin to eliminate cancer stem cell traits in pre‐malignant lesions. Drug Resist Updat. 2011;14:212‐223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Galluzzi L, Bravo‐San Pedro JM, Levine B, et al. Pharmacological modulation of autophagy: Therapeutic potential and persisting obstacles. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:487‐511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Varisli L, Cen O, Vlahopoulos S. Dissecting pharmacological effects of chloroquine in cancer treatment: interference with inflammatory signaling pathways. Immunology. 2020;159(3):257‐278. 10.1111/imm.13160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Al‐Bari MAA, Xu P. Molecular regulation of autophagy machinery by mTOR‐dependent and ‐independent pathways. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2020;1467(1):3‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Al‐Bari MAA. A current view of molecular dissection in autophagy machinery. J Physiol Biochem. 2020;76(3):357‐372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self‐digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell. 2004;6:463‐477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Baehrecke EH. Autophagy: dual roles in life and death? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:505‐510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yun CW, Lee SH. The roles of autophagy in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(11):3466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yazdani HO, Huang H, Tsung A. Autophagy: dual response in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cells. 2019;8(2):91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Levine B, Kroemer G. Biological functions of autophagy genes: a disease perspective. Cell. 2019;176(1–2):11‐42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen X, He Y, Lu F. Autophagy in stem cell biology: a perspective on stem cell self‐renewal and differentiation. Stem Cells Int. 2018;2018:9131397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chang NC. Autophagy and stem cells: self‐eating for self‐renewal. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. White E. The role for autophagy in cancer. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(1):42‐46. 10.1172/JCI73941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gewirtz DA. The four faces of autophagy: implications for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2014;74:647‐651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sui X, Chen R, Wang Z, et al. Autophagy and chemotherapy resistance: a promising therapeutic target for cancer treatment. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4(10):e838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ávalos Y, Canales J, Bravo‐Sagua R, et al. Tumor suppression and promotion by autophagy. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:603980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kung C‐P, Budina A, Balaburski G, et al. Autophagy in tumor suppression and cancer therapy. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2011;21(1):71‐100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rubinsztein DC, Codogno P, Levine B. Autophagy modulation as a potential therapeutic target for diverse diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11(9):709‐730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liang XH, Jackson S, Seaman M, et al. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature. 1999;402(6762):672‐676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vega‐Rubín‐de‐Celis S. The role of Beclin 1‐dependent autophagy in cancer. Biology (Basel). 2019;9(1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Qu X, Yu J, Bhagat G, et al. Promotion of tumorigenesis by heterozygous disruption of the beclin 1 autophagy gene. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(12):1809‐1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yue Z, Jin S, Yang C, et al. Beclin 1, an autophagy gene essential for early embryonic development, is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(25):15077‐15082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Aita VM, Liang XH, Murty VV, et al. Cloning and genomic organization of beclin 1, a candidate tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 17q21. Genomics. 1999;59(1):59‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li Z, Chen B, Wu Y, et al. Genetic and epigenetic silencing of the beclin 1 gene in sporadic breast tumors. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhang M‐Y, Wang L‐Y, Zhao S, et al. Effects of Beclin 1 overexpression on aggressive phenotypes of colon cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 2019;17(2):2441‐2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wan XB, Fan XJ, Chen MY, et al. Elevated Beclin1 expression is correlated with HIF‐1alpha in predicting poor prognosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Autophagy. 2010;6:395‐404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sun Y, Liu J‐H, Jin L, et al. Over‐expression of the Beclin1 gene upregulates chemosensitivity to anti‐cancer drugs by enhancing therapy‐induced apoptosis in cervix squamous carcinoma CaSki cells. Cancer Lett. 2010;294(2):204‐210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Laddha SV, Ganesan S, Chan CS, et al. Mutational landscape of the essential autophagy gene BECN1 in human cancers. Mol Cancer Res. 2014;12(4):485‐490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Delaney JR, Patel CB, Bapat J, et al. Autophagy gene haploinsufficiency drives chromosome instability, increases migration, and promotes early ovarian tumors. PLoS Genet. 2020;16(1):e1008558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tang H, Sebti S, Titone R, et al. Decreased BECN1 mRNA expression in human breast cancer is associated with estrogen receptor‐negative subtypes and poor prognosis. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(3):255‐263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Degenhardt K, Mathew R, Beaudoin B, et al. Autophagy promotes tumor cell survival and restricts necrosis, inflammation, and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:51‐64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Katayama M, Kawaguchi T, Berger MS, et al. DNA damaging agent‐induced autophagy produces a cytoprotective adenosine triphosphate surge in malignant glioma cells. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:548‐558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lu L, Shen X, Tao B, et al. The nanoparticle‐facilitated autophagy inhibition of cancer stem cells for improved chemotherapeutic effects on glioblastomas. J Mater Chem B. 2019;7(12):2054‐2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Qadir MA, Kwok B, Dragowska WH, et al. Macroautophagy inhibition sensitizes tamoxifen‐resistant breast cancer cells and enhances mitochondrial depolarization. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;112:389‐403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Vazquez‐Martin A, Oliveras‐Ferraros C, Menendez JA. Autophagy facilitates the development of breast cancer resistance to the anti‐her2 monoclonal antibody trastuzumab. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lorente J, Velandia C, Leal JA, et al. The interplay between autophagy and tumorigenesis: Exploiting autophagy as a means of anticancer therapy. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2017;93:152‐165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Levy JMM, Towers CG, Thorburn A. Targeting autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:528‐542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Towers CG, Thorburn A. Therapeutic targeting of autophagy. EBioMedicine. 2016;14:15‐23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rebecca VW, Amaravadi RK. Emerging strategies to effectively target autophagy in cancer. Oncogene. 2015;35:1‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang Y, Liao Z, Zhang LJ, et al. The utility of chloroquine in cancer therapy. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31:1009‐1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. DeVorkin L, Hattersley M, Kim P, et al. Autophagy inhibition enhances sunitinib efficacy in clear cell ovarian carcinoma. Mol Cancer Res. 2017;15:250‐258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Al‐Bari MAA. Chloroquine analogs in drug discovery: new directions of uses, mechanisms of actions and toxic manifestations from malaria to multifarious diseases. J Antimicrobial Chemother. 2015;70:1608‐1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kroemer G. Autophagy: a druggable process that is deregulated in aging and human disease. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:1‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ehsanian R, Van Waes C, Feller SM. Beyond DNA binding ‐ a review of the potential mechanisms mediating quinacrine's therapeutic activities in parasitic infections, inflammation, and cancers. Cell Commun Signal. 2011;9:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Liang DH, Choi DS, Ensor JE, et al. The autophagy inhibitor chloroquine targets cancer stem cells in triple negative breast cancer by inducing mitochondrial damage and impairing DNA break repair. Cancer Lett. 2016;376:249‐258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Choi DS, Blanco E, Kim YS, et al. Chloroquine eliminates cancer stem cells through deregulation of jak2 and dnmt1. Stem Cells. 2014;32:2309‐2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Balic A, Sorensen MD, Trabulo SM, et al. Chloroquine targets pancreatic cancer stem cells via inhibition of cxcr4 and hedgehog signaling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:1758‐1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rangwala R, Chang YC, Hu J, et al. Combined mtor and autophagy inhibition: Phase i trial of hydroxychloroquine and temsirolimus in patients with advanced solid tumors and melanoma. Autophagy. 2014;10:1391‐1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Stagni V, Kaminari A, Sideratou Z, et al. Targeting breast cancer stem‐like cells using chloroquine encapsulated by a triphenylphosphonium‐functionalized hyperbranched polymer. Int J Pharm. 2020;585:119465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Poklepovic A, Gewirtz DA. Outcome of early clinical trials of the combination of hydroxychloroquine with chemotherapy in cancer. Autophagy. 2014;10:1478‐1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hori YS, Hosoda R, Akiyama Y, et al. Chloroquine potentiates temozolomide cytotoxicity by inhibiting mitochondrial autophagy in glioma cells. J Neurooncol. 2014;122:11‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pascolo S. Time to use a dose of chloroquine as an adjuvant to anti‐cancer chemotherapies. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;771:139‐144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Jensen PB, Sorensen BS, Sehested M, et al. Targeting the cytotoxicity of topoisomerase ii‐directed epipodophyllotoxins to tumor cells in acidic environments. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2959‐2963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Rosenfeld MR, Ye X, Supko JG, et al. A phase i/ii trial of hydroxychloroquine in conjunction with radiation therapy and concurrent and adjuvant temozolomide in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. Autophagy. 2014;10:1359‐1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Maes H, Kuchnio A, Carmeliet P, Agostinis P. Chloroquine anticancer activity is mediated by autophagy‐independent effects on the tumor vasculature. Mol Cell Oncol. 2016;3:e970097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kim I, Rodriguez‐Enriquez S, Lemasters JJ. Selective degradation of mitochondria by mitophagy. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;462:245‐253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Dickerson T, Jauregui CE, Teng Y. Friend or foe? Mitochondria as a pharmacological target in cancer treatment. Future Med Chem. 2017;9:2197‐2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gao L, Jauregui CE, Teng Y. Targeting autophagy as a strategy for drug discovery and therapeutic modulation. Future Med Chem. 2017;9:335‐345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Hailey DW, Rambold AS, Satpute‐Krishnan P, et al. Mitochondria supply membranes for autophagosome biogenesis during starvation. Cell. 2010;141:656‐667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Okamoto K, Kondo‐Okamoto N. Mitochondria and autophagy: Critical interplay between the two homeostats. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1820:595‐600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zong WX, Rabinowitz JD, White E. Mitochondria and cancer. Mol Cell. 2016;61:667‐676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Biel TG, Rao VA. Mitochondrial dysfunction activates lysosomal‐dependent mitophagy selectively in cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2018;9:995‐1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. White E, Mehnert JM, Chan CS. Autophagy, metabolism, and cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:5037‐5046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Drake LE, Springer MZ, Poole LP, et al. Expanding perspectives on the significance of mitophagy in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2017;47:110‐124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Fujiwara M, Marusawa H, Wang HQ, et al. Parkin as a tumor suppressor gene for hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2008;27:6002‐6011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Shah SP, Roth A, Goya R, et al. The clonal and mutational evolution spectrum of primary triple‐negative breast cancers. Nature. 2012;486:395‐399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lee J, Liu K, Stiles B, Ou JJ. Mitophagy and hepatic cancer stem cells. Autophagy. 2018;14:715‐716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Yan B, Dong L, Neuzil J. Mitochondria: An intriguing target for killing tumour‐initiating cells. Mitochondrion. 2015;26:86‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Yan C, Li TS. Dual role of mitophagy in cancer drug resistance. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:617‐621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Lamb R, Ozsvari B, Lisanti CL, et al. Antibiotics that target mitochondria effectively eradicate cancer stem cells, across multiple tumor types: Treating cancer like an infectious disease. Oncotarget. 2015;6:4569‐4584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Sancho P, Burgos‐Ramos E, Tavera A, et al. Myc/pgc‐1alpha balance determines the metabolic phenotype and plasticity of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cell Metab. 2015;22:590‐605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Manago A, Leanza L, Carraretto L, et al. Early effects of the antineoplastic agent salinomycin on mitochondrial function. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Kalghatgi S, Spina CS, Costello JC, et al. Bactericidal antibiotics induce mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in mammalian cells. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(192):192ra85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Fiorillo M, Lamb R, Tanowitz HB, et al. Bedaquiline, an fda‐approved antibiotic, inhibits mitochondrial function and potently blocks the proliferative expansion of stem‐like cancer cells (cscs). Aging (Albany NY). 2016;8:1593‐1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Esner M, Graifer D, Lleonart ME, et al. Targeting cancer cells through antibiotics‐induced mitochondrial dysfunction requires autophagy inhibition. Cancer Lett. 2016;384:60‐69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Renz BW, D'Haese JG, Werner J, et al. Repurposing established compounds to target pancreatic cancer stem cells (cscs). Med Sci (Basel). 2017;5:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Skrtic M, Sriskanthadevan S, Jhas B, et al. Inhibition of mitochondrial translation as a therapeutic strategy for human acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:674‐688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Chu DJ, Yao DE, Zhuang YF, et al. Azithromycin enhances the favorable results of paclitaxel and cisplatin in patients with advanced non‐small cell lung cancer. Genet Mol Res. 2014;13:2796‐2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Najumudeen AK, Jaiswal A, Lectez B, et al. Cancer stem cell drugs target k‐ras signaling in a stemness context. Oncogene. 2016;35:5248‐5262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Ashton TM, Fokas E, Kunz‐Schughart LA, et al. The anti‐malarial atovaquone increases radiosensitivity by alleviating tumour hypoxia. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Lamb R, Bonuccelli G, Ozsvari B, et al. Mitochondrial mass, a new metabolic biomarker for stem‐like cancer cells: Understanding wnt/fgf‐driven anabolic signaling. Oncotarget. 2015;6:30453‐30471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Al‐Bari MAA, Shinohara M, Nagai Y, et al. Inhibitory effect of chloroquine on bone resorption reveals the key role of lysosomes in osteoclast differentiation and function. Inflam Regener. 2012;32:222‐231. [Google Scholar]

- 100. Cho I, Yamanishi S, Cox L, et al. Antibiotics in early life alter the murine colonic microbiome and adiposity. Nature. 2012;488:621‐626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]