Abstract

This study evaluates the risk of preoperative opioid exposure on all-cause mortality after outpatient surgery.

Among older patients, opioid analgesics are associated with falls, fractures, and respiratory complications.1 Although the effect of preoperative opioid exposure on postoperative events has been described,2 little is known about its effect on mortality. As the proportion of older individuals undergoing surgery is rising, we sought to evaluate the risk of preoperative opioid exposure on all-cause mortality after outpatient surgery.

Methods

Using a 20% national sample of Medicare beneficiaries, we examined individuals 65 years or older who underwent outpatient surgical procedures between January 1, 2009, and September 30, 2015, with continuous enrollment in Medicare Parts A, B, and D at least 12 months prior to and 3 days after their discharge date. This study was deemed exempt by the institutional review board at the University of Michigan.

Our primary outcome was 90-day mortality after surgery. We defined preoperative opioid use as pharmaceutical fills in the year prior to surgery including dose, duration, proximity to surgical date, and continuity of fills. We classified preoperative opioid use as naive, low, medium, and high (Table).3 We used logistic regression to examine all-cause mortality and preoperative opioid use adjusting for medical comorbidities, surgery type, and frailty.4 Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp), SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute), and R version 4.0.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Statistical significance was set at 2-tailed P value less than .05. Analysis began September 2019 and ended March 2020.

Table. Clusters by Preoperative Opioid Use.

| Group | No. (%) | Median (IQR) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total OME filled preoperatively | Duration, mo | Continuity, mo | Recency, mo | ||

| Low | 10 412 (30) | 270 (450) | 1 (1) | 1 (0) | 8 (3) |

| Medium | 18 341 (53) | 675 (1665) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| High | 5607 (16) | 9900 (13 800) | 10 (2) | 9 (5) | 1 (1) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; OME, oral morphine equivalent.

Results

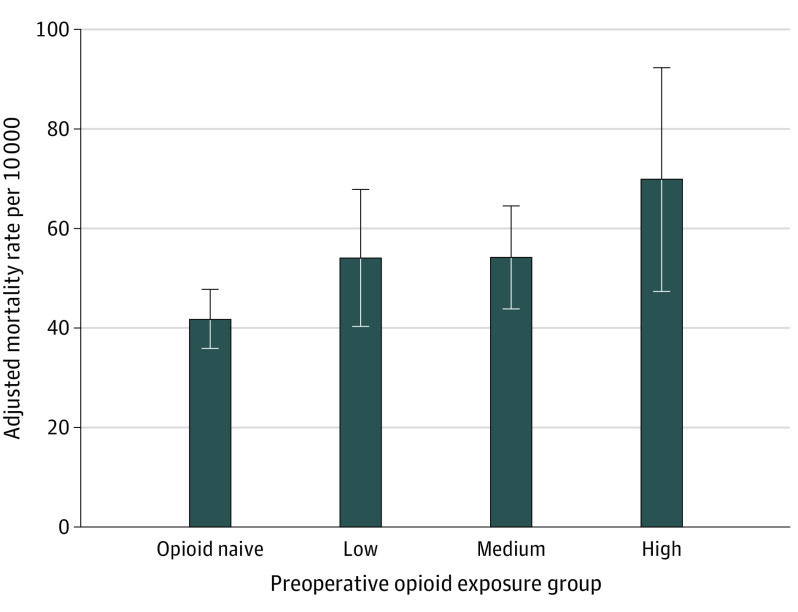

In total, there were 99 125 patients included for analysis. Of these, 54 582 (55.06%) were male. Overall 90-day postoperative mortality was 0.48% (471 of 99 125). Preoperative opioid use was correlated with an increased mortality within 90 days after surgery (Figure), and patients with high preoperative opioid exposure were more likely to die within 90 days after outpatient surgery compared with opioid-naive patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.16-2.44), even after controlling for type of surgery. Medium preoperative opioid users also had higher rates of 90-day mortality compared with opioid-naive patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.01-1.67). Mortality did not differ between opioid-naive patients and patients with low preoperative opioid exposure.

Figure. Adjusted 90-Day Mortality by Preoperative Opioid Use.

Procedures included varicose vein removal, hemorrhoidectomy, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, transurethral prostate surgery, thyroidectomy, parathyroidectomy, carpal tunnel release, umbilical hernia repair, and inguinal hernia repair. Mortality was adjusted for age, sex, race, Medicaid eligibility, type of surgery, Charlson Comorbidity Index, history of tobacco use, mental health disorders, pain disorders, hospitalization in prior year, stay in skilled nursing facility in prior year, concurrent fill of benzodiazepine, and frailty index.

Discussion

Opioid analgesics are effective in managing acute pain but are associated with important risks, particularly among older adults.5 Among Medicare beneficiaries, we observed higher mortality among individuals undergoing outpatient surgery who had greater preoperative exposure.

While guidelines exist for long-term opioid therapy, guidelines for the management of acute pain have only recently emerged, and few consider the potential risks of preoperative opioid exposure. Postoperative prescribing guidelines for common surgical procedures released by professional societies have largely focused on pain management among opioid-naive patients, with less direction regarding preoperative opioid exposures. Nonetheless, current opioid use is correlated with higher perioperative risk,6 and future studies that examine the mechanisms by which opioids mediate postoperative outcomes are necessary to tailor preoperative screening.

Our study is limited, and we cannot capture opioid use outside of claims. Furthermore, there are likely unmeasured factors that contribute to mortality that we cannot account for. However, our findings highlight the need to address preoperative opioid exposure to ensure a safe postoperative recovery. Patients who use opioids preoperatively may not only require higher doses of opioids for postoperative pain control because of tolerance, but are also more vulnerable to opioid-related adverse events, such as respiratory complications, readmissions, and mortality.2 Going forward, for patients with high opioid exposure, opioid weaning prior to surgery could optimize postoperative care. Other strategies to mitigate opioid-related risk could include coprescribing with naloxone, avoidance of benzodiazepines, delaying discretionary procedures, and encouraging the use of opioid alternatives for pain management. Implementation of these strategies could help reduce the risk of mortality after outpatient surgery, improving the safety of surgical care.

References

- 1.Yoshikawa A, Ramirez G, Smith ML, et al. . Opioid use and the risk of falls, fall injuries and fractures among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. Published online February 4, 2020. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glaa038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang R, Santosa KB, Vu JV, et al. . Preoperative opioid use and readmissions following surgery. Ann Surg. Published online March 13, 2020. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vu JV, Cron DC, Lee JS, et al. . Classifying preoperative opioid use for surgical care. Ann Surg. 2020;271(6):1080-1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orkaby AR, Nussbaum L, Ho YL, et al. . The burden of frailty among U.S. veterans and its association with mortality, 2002-2012. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(8):1257-1264. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gly232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, Hall K, Stein CM. Prescription of long-acting opioids and mortality in patients with chronic noncancer pain. JAMA. 2016;315(22):2415-2423. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hilliard PE, Waljee J, Moser S, et al. . Prevalence of preoperative opioid use and characteristics associated with opioid use among patients presenting for surgery. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(10):929-937. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]