To the Editor:

There has been significant re-organisation of Ophthalmology services worldwide to adapt to the COVID-19 pandemic, for instance in glaucoma care [1], acute ophthalmology services [2], as well as uveitis [3], medical retina [4] and oculoplastic care [5].

Elective cataract surgery postponed during the pandemic invariably led to longer wait and possible anxiety among patients [6]. Patients’ apprehension about having cataract surgery during the easing of COVID-19 lockdown should not be ignored. During these unprecedented times, it is therefore important to keep patients informed, particularly about the potential risk of contracting COVID-19 infection during restoration of cataract surgery services [7]. Despite significant changes made within the plethora of Ophthalmology services during this time, there is scarcity of research centred on patients’ perspectives during the restructuring of these services. The aim of this survey is to determine patients’ perceptions while waiting for cataract surgery during the pandemic and their willingness to have their operation following the easing of lockdown.

The survey was carried out using structured questionnaire over the telephone (Appendix 1A) from 14th to 30th June 2020. Patients were recruited from the waiting lists in two hospitals within the UK. Patients who had been given a date for cataract surgery, who could not be contacted after three separate attempts, and who had problems hearing or understanding interview questions were excluded. Vision related quality of life (VRQoL) was assessed by asking patients to grade their level of difficulty in carrying out activities due to their vision. The survey’s composite outcome measures were patients’ concern regarding cataract surgery delay, their willingness to attend hospital for cataract surgery during easing of the COVID-19 lockdown, and their maximum acceptable waiting time (MAWT) for cataract surgery [8, 9].

Additional demographic data including visual acuity and ocular comorbidities were collected from clinic letters and the electronic medical records. Statistical analysis was carried out using Pearson’s chi-square test. As this survey lied outside the scope of the UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Research, the need for independent ethical review was waived by the local research ethics committee.

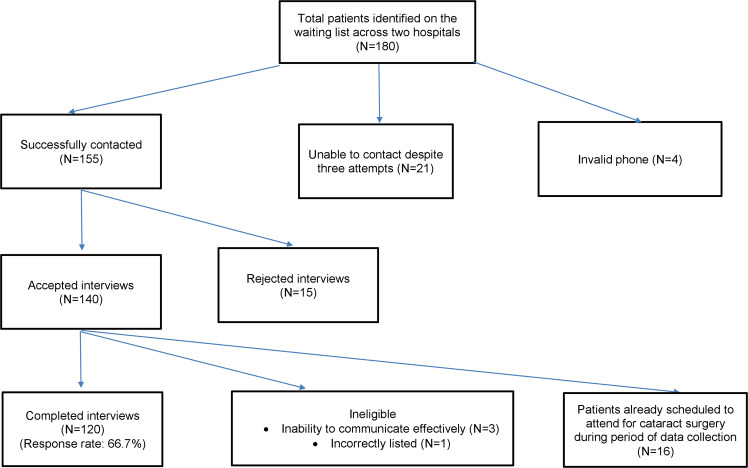

There were 180 patients on the waiting list. 120 eligible patients completed the interview (Fig. 1). Demographic information and results of patients’ responses to the questionnaire are shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart showing the recruitment of patients according to eligibility criteria.

Table 1.

Table showing demographic information of patients recruited and their responses to items on the questionnaire.

| Type of demographic information | Number of respondents N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 50 (41.7) |

| Female | 70 (58.3) |

| Age | |

| Mean ± SD (Range) | 76.92 ± 8.65 (39–96) |

| Number of days since listed | |

| Mean (Range) | 134.4 (51–401) |

| Vision in listed eye | |

| Mean (Range) | 0.59 (0.04–1.66) |

| Vision in other eye | |

| Mean (Range) | 0.35 (−0.12–1.66) |

| First/second eye | |

| First eye | 82 (68.3) |

| Second eye | 38 (31.7) |

| Other ocular comorbidities | |

| Yes | 74 (61.7) |

| No | 46 (38.3) |

| Responses to questionnaire items* | |

| *Driving status | |

| Yes | 66 (55) |

| No | 54 (45) |

| *Profession | |

| Unemployed | 2 (1.7) |

| Employed | 7 (5.8) |

| Retired | 111 (92.5) |

| *Living alone | |

| Yes | 62 (51.7) |

| No | 58 (48.3) |

| *Main carer | |

| Yes | 12 (10) |

| No | 108 (90) |

| *Patient reported health status score | |

| 1 being worst and 5 being best general health | |

| Mean (Range) | 3.5 (1–5) |

| *Shielding | |

| Yes | 55 (45.5) |

| No | 65 (54.5) |

| *Vision related quality of life (VRQOL) | |

| No difficulty | 16 (13.3) |

| Slight difficulty | 48 (40) |

| Moderate difficulty | 35 (29.2) |

| Severe difficulty | 21 (17.5) |

| *Stability of symptoms during wait | |

| Stable | 45 (37.5) |

| Gotten worse | 75 (62.5) |

| *Has COVID-19 affected willingness to attend hospital for surgery | |

| Yes | 20 (16.7) |

| No | 100 (83.3) |

| *Concern with delay | |

| Not concerned at all | 25 (20.8) |

| Slightly concerned | 40 (33.3) |

| Moderately concerned | 34 (28.3) |

| Very concerned | 21 (17.6) |

| *Maximum acceptable wait time (MAWT) for surgery | |

| <3 months | 95 (79.2) |

| 3–6 months | 18 (15) |

| 6–12 months | 7 (5.8) |

| *Factors affecting decision | |

| Public health advice | 16 (13.3) |

| Visual needs | 48 (40) |

| Both | 35 (29.2) |

| Neither | 21 (17.5) |

| *Communication about waiting time | |

| Yes | 111 (92.5) |

| No | 9 (7.5) |

Our survey showed that the current pandemic did not affect patients’ decision to attend hospital for cataract surgery as 83.3% indicated their willingness to come for cataract surgery. Our survey showed that patients who reported worse VRQoL and higher level of concern regarding delay were more likely to have a MAWT <3 months, which is statistically significant (p < 0.05) (Appendix 1B). However, those with ocular comorbidities other than cataract were more likely to have a MAWT >3 months (p < 0.05). Predictors for those prioritising vision needs over official public health advice include male gender (p = 0.022), younger age (p = 0.002) and those who normally drive (p = 0.014).

Our survey results could not be generalised to other hospital trusts within the UK due to the small sample size. Furthermore, confounding factors were not accounted for during data analysis. However, we found that VRQoL, independent of visual acuity is an important factor to be taken into consideration when listing patients for cataract surgery [9, 10]. Communication about waiting time to manage expectations is essential to dampen patient anxiety whilst waiting for cataract surgery.

Patient prioritisation for cataract surgery during the restoration of cataract surgery services may need to take account patients’ visual needs and their willingness to come rather than waiting time criteria or referral to treatment targets.

Supplementary information

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41433-020-01229-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Jayaram H, Strouthidis NG, Gazzard G. The COVID-19 pandemic will redefine the future delivery of glaucoma care. Eye. 2020;34:1203–5. doi: 10.1038/s41433-020-0958-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wickham L, Hay G, Hamilton R, Wooding J, Tossounis H, da Cruz L, et al. The impact of COVID policies on acute ophthalmology services—experiences from Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. Eye. 2020;34:1189–92. doi: 10.1038/s41433-020-0957-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hung JC, Li KK. Implications of COVID-19 for uveitis patients: perspectives from Hong Kong. Eye. 2020;34:1163–4. doi: 10.1038/s41433-020-0905-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shmueli O, Chowers I, Levy J. Current safety preferences for intravitreal injection during COVID-19 pandemic. Eye. 2020;34:1165–7. doi: 10.1038/s41433-020-0925-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang S, Thomas PB, Sim DA, Parker RT, Daniel C, Uddin JM, et al. Oculoplastic video-based telemedicine consultations: Covid-19 and beyond. Eye. 2020;34:1193–4. doi: 10.1038/s41433-020-0953-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown TS, Bedard NA, Rojas EO, Anthony CA, Schwarzkopf R, Barnes CL, et al. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on electively scheduled hip and knee arthroplasty patients in the United States. J Arthroplast. 2020;35:S49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloom P Cataract surgery guidelines for Post COVID-19 pandemic: Recommendations V 1.5 [Internet]. RCOphth COVID-19 REVIEW TEAM and UKISCRS; May 2020 [cited 14 July 2020]. https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/RCOphth-UKISCRS-COVID-cataract-surgery-restoring-services-070520.pdf.

- 8.Chan FW, Fan AH, Wong FY, Lam PT, Yeoh EK, Yam CH, et al. Waiting time for cataract surgery and its influence on patient attitudes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:3636–42. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conner-Spady BL, Sanmugasunderam S, Courtright P, Mildon D, McGurran JJ, Noseworthy TW, Steering Committee of the Western Canada Waiting List Project. Patient and physician perspectives of maximum acceptable waiting times for cataract surgery. Can J Ophthalmol. 2005;40:439–47. doi: 10.1016/S0008-4182(05)80003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weingessel B, Richter-Mueksch S, Vécsei-Marlovits PV. Which factors influence patients’ maximum acceptable waiting time for cataract surgery? - a questionnaire survey. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89:e231–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2010.01938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.