Abstract

Background:

Behavioral markers for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are not included within the widely used amyloid-tau-neurodegeneration framework.

Objective:

To determine when falls occur among cognitively normal (CN) individuals with and without preclinical AD.

Methods:

This cross-sectional study recorded falls among CN participants (n = 83) over a 1-year period. Tailored calendar journals recorded falls. Biomarkers including amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) and structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging were acquired within 2 years of fall evaluations. CN participants were dichotomized by amyloid PET (using standard cutoffs). Differences in amyloid accumulation, global resting state functional connectivity (rs-fc) intra-network signature, and hippocampal volume were compared between individuals who did and did not fall using Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Among preclinical AD participants (amyloid-positive), the partial correlation between amyloid accumulation and global rs-fc intra-network signature was compared for those who did and did not fall.

Results:

Participants who fell had smaller hippocampal volumes (p = 0.04). Among preclinical AD participants, those who fell had a negative correlation between amyloid uptake and global rs-fc intra-network signature (R = −0.75, p = 0.012). A trend level positive correlation was observed between amyloid uptake and global rs-fc intra-network signature (R = 0.70, p = 0.081) for preclinical AD participants who did not fall.

Conclusion:

Falls in CN older adults correlate with neurodegeneration biomarkers. Participants without falls had lower amyloid deposition and preserved global rs-fc intra-network signature. Falls most strongly correlated with presence of amyloid and loss of brain connectivity and occurred in later stages of preclinical AD.

Keywords: Falls, Alzheimer’s disease, Biomarkers, Volumetrics, Resting State Functional Connectivity

INTRODUCTION

Falls are a leading cause of injury, premature placement into skilled nursing facilities, injury-related mortality, and long-term disability among older adults [1]. Individuals diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have more than twice the risk of serious falls compared to the general population [2, 3]. As more individuals are diagnosed with AD in the United States [4], the number of devastating falls will rise.

Preclinical AD is characterized by biomarkers including amyloid (A), tau (T), and neurodegeneration (N) [5, 6]. The progression to AD has been hypothesized to occur with amyloid, then tau, followed by neurodegenerative changes [6]. Changes in these biomarkers [5], [7] occur decades before cognitive symptoms develop [8]. Amyloid deposition can be measured by positron emission tomography (PET). Individuals can be categorized as either “amyloid-positive” or “amyloid-negative” [9]. Neurodegeneration can be identified by structural (volumetrics) or functional (resting state functional connectivity [rs-fc] intra-network) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) changes. Hippocampal volume loss [10] and decreases in rs-fc intra-network strength have been observed during the conversion to symptomatic AD [11, 12].

Individuals in the preclinical stages of AD have also demonstrated a higher risk of falls [13, 14], suggesting that falls could potentially serve as a behavioral marker. However, it remains unknown when falls occur in the AT(N) cascade of changes that are used to define individuals at risk for conversion to AD. To address this gap, we explored the relationship between PET amyloid accumulation, brain volumetrics, global rs-fc intra-network signature, and falls in cognitively normal (CN) individuals with and without preclinical AD.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were followed by the Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Washington University in St. Louis. These community-dwelling individuals participate in longitudinal studies of memory and aging. Individuals were invited to participate if they: (1) were 65 years or older, (2) had normal cognition as determined by a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) of 0 at the time of assessment, and (3) underwent an imaging study within 2 years of CDR assessment. Additional details of the study have been previously described [13]. All participants underwent amyloid PET and MRI (structural and functional) within 2 years of enrollment. Eighty-three participants met these criteria (Table 1). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Washington University in St. Louis. All procedures were done in accordance with the Washington University in St. Louis ethical standards committee for experiments using human subjects.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics do not differ when stratified by amyloid status and fall occurrence

| Fallers | Non- Fallers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amyloid-Positivea | Amyloid-Negative | Amyloid-Positivea | Amyloid-Negative | p | |

| N | 13 | 37 | 10 | 23 | |

| Age (years) (SD) | 73.6 (6.3) |

73.1 (5.4) |

73.3 (2.9) |

71.5 (4.6) |

0.56 |

| Gender (% female) | 69.2% 9/13 |

70.3% 26/37 |

50.0% 5/10 |

56.5% 13/23 |

0.53 |

| Education (years) (SD) | 15.4 (2.9) |

15.4 (2.9) |

16.7 (2.1) |

15.5 (2.7) |

0.61 |

| Race (% white) | 100% 13/13 |

97.3% 36/37 |

100% 10/10 |

95.7% 22/23 |

0.81 |

| APOE ε4+ | 53.8% 7/13 |

8.1% 3/37 |

30.0% 3/10 |

34.8% 8/23 |

0.01 |

Amyloid positivity defined by cutoff ≥1.42 for standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) 12

APOE = apolipoprotein E

SD = standard deviation

CDR Status

A licensed clinician administered a standard clinical and cognitive assessment to all individuals. The CDR was used to assess the level of cognitive impairment [15]. CDR scores range from 0 (cognitively normal) to 3 (severe dementia); CDR 0.5 indicates very mild dementia. All participants in this study were CDR 0 at the time of evaluation.

APOE Status

DNA samples were obtained and genotyped according to previously published methods [16]. Either an Illumina 610 or Omniexpress chip was used for genotyping. To include the effects of the Apolipoprotein ε4 (APOE) gene in this analysis, APOE status was converted from a genotype to a binary variable. Participants were deemed “APOE-positive” if they possessed at least one copy of the APOE ε4 allele, and “APOE-negative” otherwise.

Falls

A 12-month calendar journal was given to each participant to record whether or not a fall had occurred each day. The calendar journals were tailored for each participant, with birthdays and important personal dates serving as cues for accurately recalling when a fall occurred [17]. The calendar journal included pages to record additional details if a fall occurred. Participants underwent a telephone training session to learn how to use the calendar journal. A fall was defined as any unintentional movement to the floor, ground, or an object below knee level [18]. Monitoring of fall documents and gathering details of falls was performed monthly [18]. A gift card was mailed to each participant after they returned a completed calendar journal each month. If a fall was reported, a research team member interviewed the participant to verify that the fall met the operational definition.

Amyloid PET Acquisition and Processing

PET imaging was acquired within 2 years of MRI using previously described methods [19, 20]. Participants were injected with 12–15 mCI of [11C] Pittsburgh compound B (PiB), and dynamic scans were acquired. The post-injection time window for quantification was 30–60 minutes. A PET Unified Pipeline (github.com/ysu001/PUP) was implemented to process the data. Briefly, a region of interest (ROI) segmentation approach was used with FreeSurfer 5.3 (Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Charlestown, Massachusetts, USA). A tissue mask was created based on ROI segmentation, and partial volume correction was applied [19]. A standard uptake ratio (SUVR) was obtained for each ROI, with the cerebellar gray matter serving as a reference region. A summary value (mean cortical uptake ratio) of the partial-volume corrected SUVR was derived from cortical regions affected by AD [9].

Structural MRI Acquisition and Analysis

MRI was acquired using a 3T Siemens scanner (Erlangen, Germany) as previously described [10]. T1-weighted scans were acquired with 1-mm isotropic resolution, and T2-weighted images were acquired for registration. Segmented regional volumes were adjusted for intracranial volume using a linear regression. Left and right hippocampal volumes were converted to Z scores and averaged to generate a single hippocampal volume Z score [21–23].

Functional MRI Acquisition and Analysis

Rs-fc scans were obtained using 36 contiguous slices (approximately 4.0-mm isotropic voxels) [24]. During the rs-fc scans, participants were instructed to fixate on a small plus sign and to not fall asleep. Rs-fc preprocessing followed previously documented methods [24–26]. ROIs were specified in a seed-based manner [27]. A 298 functional ROI matrix was assembled into 13 resting state networks (RSNs). These RSNs included the auditory, visual, memory, ventral attention, dorsal attention, salience, default mode, sensorimotor, sensorimotor-lateral, cingulo-opercular, subcortical, cerebellum, and frontoparietal networks [28]. Thirteen composite scores from each RSN were generated by obtaining the average of the Pearson correlations between all ROIs within a network. These results were Fisher-Z transformed. Singular value decomposition was performed on the 13 RSN composite scores to acquire a global rs-fc intranetwork signature [29] . To obtain this single summary signature score for each individual, the eigenvector of the first principal component was multiplied by each individual’s intranetwork connections [30]. This global rs-fc intranetwork signature is a weighted combination of the 13 intranetwork connections, with a higher score indicating greater network specificity [31].

Statistical Analysis

We used a previously established amyloid PET cutoff level of 1.42 [9, 19], derived from cortical regions to define amyloid positivity. Participants were classified as having low global rs-fc intra-network connectivity if their global rs-fc signature value was below the median, and they were classified for amyloid on the basis of amyloid positivity. To compare the cohort on the basis of amyloid status and whether the individual had a history of falls, we performed t-tests for continuous variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables. We performed a non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test to test for differences in amyloid level, global rs-fc intra-network signature, and hippocampal volume between individuals who documented a fall and individuals who did not have a fall. Individuals were further separated by amyloid status. Finally, we calculated the partial correlation between cortical amyloid accumulation and global rs-fc intra-network signature, correcting for differences in age, sex, and education. Rather than computing a single partial correlation, we separated the cohort into four groups: amyloid positive-individuals who fell, amyloid-negative individuals who fell, amyloid-positive individuals with no recorded falls, and amyloid-negative individuals with no recorded falls. We also calculated the partial correlation between hippocampal volume and global rs-fc intra-network signature, correcting for differences in age, sex, and education. We then performed maximum likelihood model selection to test for differences between individuals who fell and those who did not fall with respect to their relative hippocampal volumes and global rs-fc intra-network signatures. To assess whether participants who fell were more likely to have high amyloid and low global rs-fc intra-network connectivity, we performed a test for equal proportions. All analyses were conducted in R [32]. Partial correlation calculations used ppcor [33]. Figures were generated with ggplot [34] and ggpubr [35].

RESULTS

Within the CN cohort, there were no significant differences in demographic variables, except for APOE ε4 status, between those with or without preclinical AD (amyloid-positive) and those who did or did not have a recorded fall (Table 1). There was no difference in amyloid PET positivity between participants who fell and those who did not (p = 0.45).

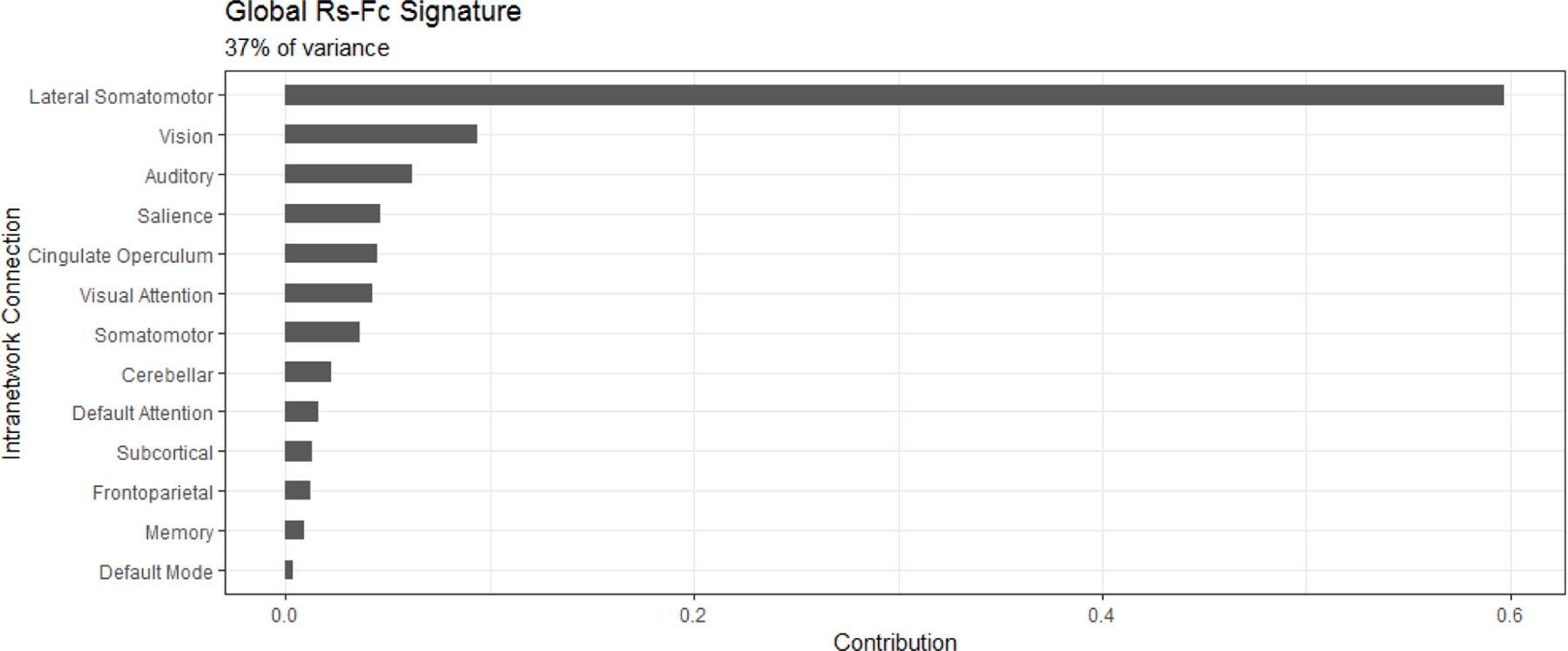

After applying singular value decomposition, the first principal component of the global rs-fc intra-network signature explained 37% of the variance in the data. This component was primarily composed of the lateral somatomotor network, which accounted for nearly 60% of the signature. The other significant networks included primary sensory networks (Figure 1). Notably, the memory and default mode networks, typically associated with AD [36], had relatively small contributions to the global rs-fc intra-network signature. There was no difference in global rs-fc intra-network signature between participants who fell and those who did not (p = 0.52).

Figure 1.

The global resting state functional connectivity (rs-fc) intra-network signature is dominated by the lateral somatomotor network, followed by other primary sensory networks.

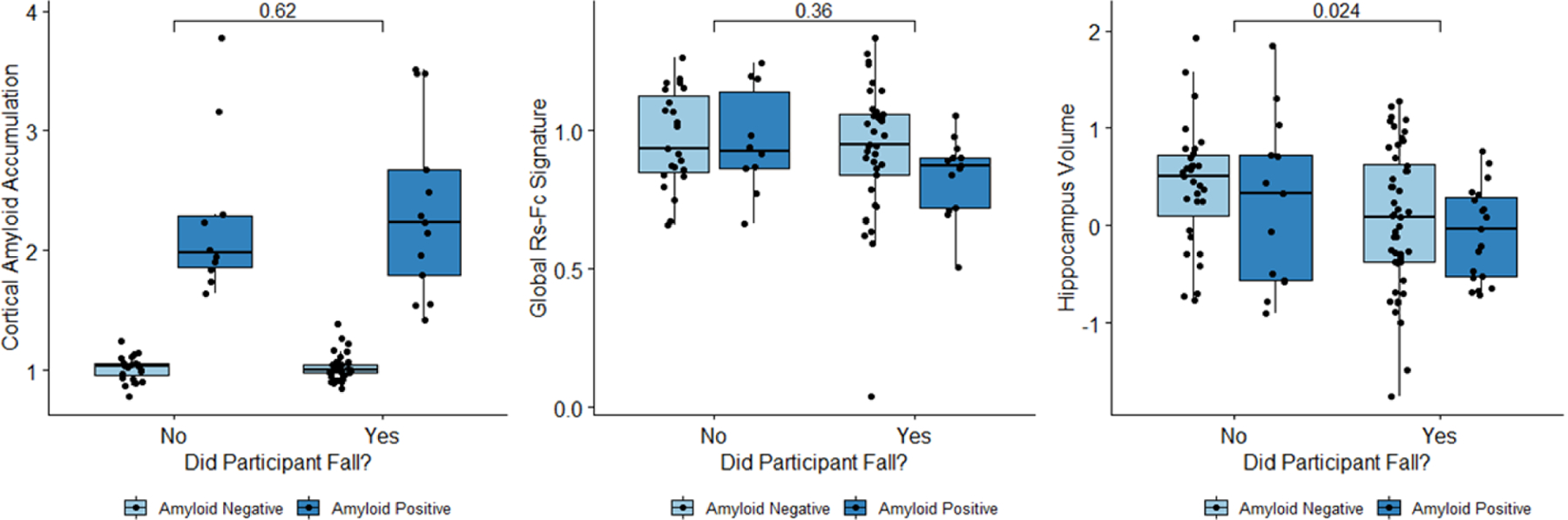

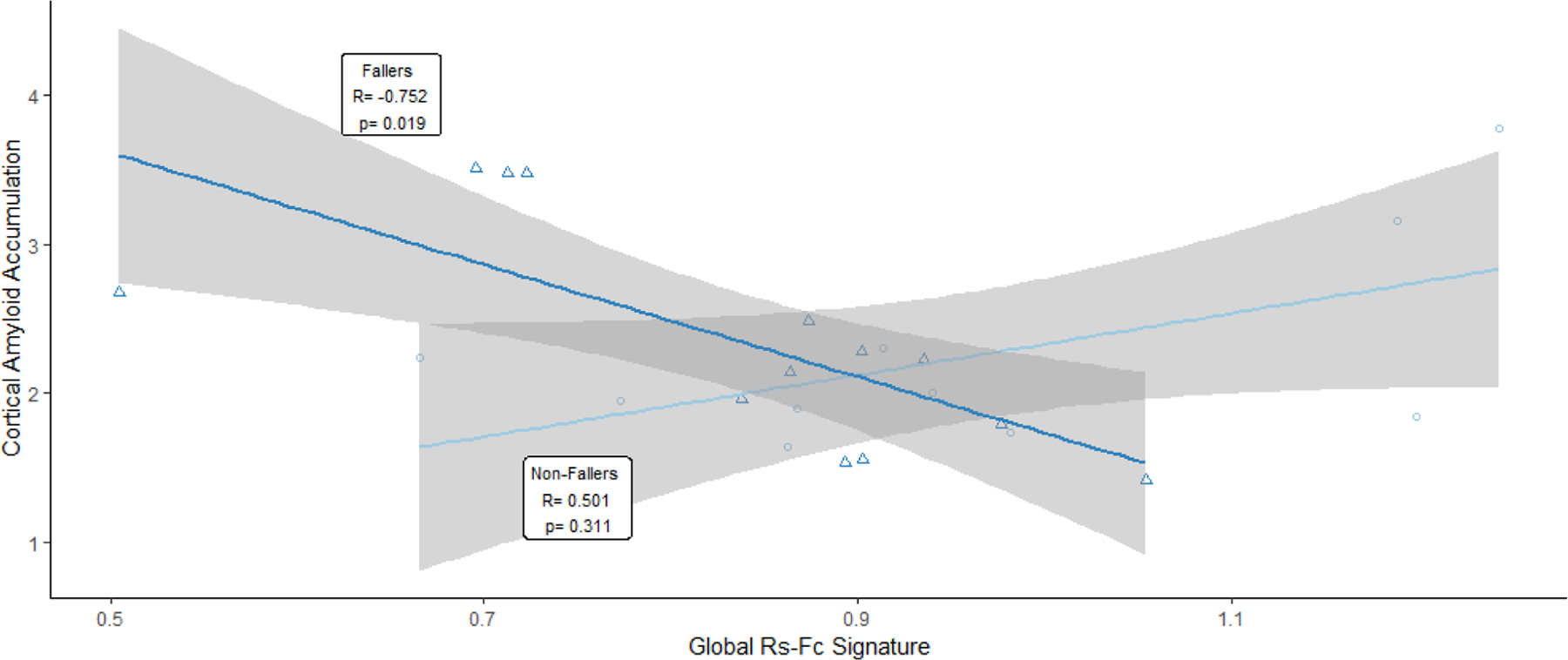

There was a significant difference in hippocampal volume, which is a marker of neurodegeneration, between participants who fell and those who did not fall (p = 0.02) (Figure 2). When amyloid-positive and amyloid-negative CN participants were analyzed together, no significant interactions were found with amyloid PET accumulation and global rs-fc intra-network signature between individuals who had a recorded fall and those who did not have a fall. After isolating amyloid-positive participants for analysis (n = 23), amyloid-positive individuals who fell had a significant negative correlation between amyloid level and global rs-fc intra-network signature (R = −0.75, p = 0.012). In contrast, amyloid-positive individuals who did not have a recorded fall had a trend-level positive correlation between amyloid level and global rs-fc intra-network signature (R = 0.70, p = 0.081) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Whether or not a participant falls is correlated with hippocampus volume, but not with amyloid accumulation or global rs-fc intra-network signature strength.

Figure 3.

Participants with falls vs. those without a fall show inverse correlations between amyloid accumulation and global rs-fc intra-network signature.

In both individuals who fell and those who did not fall, there was a positive correlation between global rs-fc intra-network signature and hippocampal volume (Supplementary Figure 1). Among participants who had a fall, a trend-level association was seen, with these individuals more likely to have both low global rs-fc intra-network signature and high amyloid PET (p = 0.0558, chi-squared = 3.66).

Discussion

This study provides preliminary evidence that falls in CN older adults correlate with markers of neurodegeneration, including hippocampal volume. It also suggests that amyloid alone does not lead to falls, but a combination of amyloid and impaired rs-fc increases the risk of falling.

Our estimation of global rs-fc intra-network signature was primarily composed of the lateral somatomotor network and primary sensory networks. As the somatomotor network is related to motor planning, motor function, and balance, and the primary sensory networks are related to obtaining and using information from our sensory systems, this may explain why individuals with deficits in these networks are at increased risk of falling. This is consistent with a known progression: a decline in motor and sensory function tends to precede cognitive impairment [37–39].

Whether or not a participant fell was correlated with hippocampal volume but not with amyloid accumulation or global rs-fc intra-network signature strength. This finding suggests that falls may occur later along the continuum of the AT(N) framework. We observed that the presence of falls was associated with neurodegeneration and was closer to the onset of cognitive changes (see Supplementary Figure 1). Although the sample was relatively small, interesting preliminary findings suggest a relationship between amyloid positivity and neurodegeneration. CN individuals who were amyloid-positive and who had a reduced global rs-fc intra-network signature had a greater risk of falls. It is possible that these individuals could compensate for amyloid accumulation if functional connections remain intact. This compensation ceases with the onset of neurodegeneration, and fall risk subsequently increases. In our cohort, participants who did not fall had either high amyloid and relatively preserved global rs-fc intra-network signature or low amyloid and low global rs-fc intra-network connectivity. Our findings suggest that falls are likely to occur during the neurodegeneration phase of preclinical AD, approximately 0–5 years before symptom onset.

These preliminary findings suggest that additional studies to understand falls among individuals with preclinical AD should occur to elucidate the relationship between current molecular biomarkers and behavioral biomarkers (such as falls). Network connections, hippocampal volume, and level of amyloid accumulation appear to be related to fall risk. A better understanding of when an increased risk of falls occurs in the progression of the AT(N) model is important for our understanding of the progression of the disease and for classification purposes. Understanding whether and when falls occur during preclinical AD is important for several reasons. First, if falls are occurring because of amyloid accumulation or neurodegeneration, it is possible that current fall prevention treatments will not be effective for this population. Second, if falls are a behavioral biomarker of AD, understanding when they occur during the preclinical phase of the disease will provide new insight into AD.

Advantages of this study include a well-characterized cohort who had rs-fc imaging. We used a new method of examining intra-network connections by calculating a global rs-fc intra-network signature for each individual [29]. However, findings should be interpreted with caution. The small cohort was predominantly female and white. The analysis of the relationship between amyloid accumulation and global rs-fc intra-network signature included a relatively small number of individuals who had falls (n = 23). Another limitation of this study was our lack of access to tau-related data (both cerebrospinal fluid and tau PET) for these participants. Although we see associations between falls and later, but not earlier, stages of the AT(N) framework, we were unable to evaluate falls during the middle stage (tau). The findings may only apply to this population and cannot be generalized to other populations, and the small sample size may not have enough power to generalize results. Despite limitations, these preliminary data add to our growing understanding of the relationship between observable behaviors (such as falls) and molecular biomarkers of AD. Further longitudinal studies from a larger cohort are needed.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the NIH, National Institute of Aging (R01AG057680; R01AG052550), NIH Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (P50AG005681); Healthy Aging Senile Dementia (P01AG003991); Antecedent Biomarkers for AD: The Adult Children Study (P01AG026276); National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Center Core for Brain Imaging (P30NS04805609); and generous support from the Paula C. and Rodger O. Riney Fund and the Daniel J. Brennan MD Fund.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST/DISCLOSURES

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- [1].Tinetti ME, Williams CS (1997) Falls, injuries due to falls, and the risk of admission to a nursing home. New Engl J Med 337, 1279–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF (1988) Risk-factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. New Engl J Med 319, 1701–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Anstey KJ, von Sanden C, Luszcz MA (2006) An 8-year prospective study of the relationship between cognitive performance and falling in very old adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 54, 1169–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DA (2013) Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology 80, 1778–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jack CR, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Aisen PS, Shaw LM, Vemuri P, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Lesnick TG, Pankratz VS, Donohue MC, Trojanowski JQ (2013) Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol 12, 207–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Jack CR Jr., Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, Holtzman DM, Jagust W, Jessen F, Karlawish J, Liu E, Molinuevo JL, Montine T, Phelps C, Rankin KP, Rowe CC, Scheltens P, Siemers E, Snyder HM, Sperling R, Contributors (2018) NIA-AA Research Framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 14, 535–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Blennow K, Dubois B, Fagan AM, Lewczuk P, de Leon MJ, Hampel H (2015) Clinical utility of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in the diagnosis of early Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 11, 58–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Johnson SC, Christian BT, Okonkwo OC, Oh JM, Harding S, Xu GF, Hillmer AT, Wooten DW, Murali D, Barnhart TE, Hall LT, Racine AM, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Bendlin BB, Gallagher CL, Carlsson CM, Rowley HA, Hermann BP, Dowling NM, Asthana S, Sager MA (2014) Amyloid burden and neural function in people at risk for Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol Aging 35, 576–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mintun MA, Larossa GN, Sheline YI, Dence CS, Lee SY, Mach RH, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, DeKosky ST, Morris JC (2006) [11C]PIB in a nondemented population: potential antecedent marker of Alzheimer disease. Neurology 67, 446–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gordon BA, Blazey T, Su Y, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Benzinger TL (2016) Longitudinal beta-amyloid deposition and hippocampal volume in preclinical alzheimer disease and suspected non-alzheimer disease pathophysiology. JAMA Neurol 73, 1192–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Badhwar A, Tam A, Dansereau C, Orban P, Hoffstaedter F, Bellec P (2017) Resting-state network dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 8, 73–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chhatwal JP, Schultz AP, Johnson K, Benzinger TL, Jack C, Jr., Ances BM, Sullivan CA, Salloway SP, Ringman JM, Koeppe RA, Marcus DS, Thompson P, Saykin AJ, Correia S, Schofield PR, Rowe CC, Fox NC, Brickman AM, Mayeux R, McDade E, Bateman R, Fagan AM, Goate AM, Xiong C, Buckles VD, Morris JC, Sperling RA (2013) Impaired default network functional connectivity in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease. Neurology 81, 736–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Stark SL, Roe CM, Grant EA, Hollingsworth H, Benzinger TL, Fagan AM, Buckles VD, Morris JC (2013) Preclinical Alzheimer disease and risk of falls. Neurology 81, 437–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Stark S, Roe C, Grant E, Morris J (2011) Risk of falls among older adults with preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7, S176. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Morris JC (1997) Clinical dementia rating: a reliable and valid diagnostic and staging measure for dementia of the Alzheimer type. Int Psychogeriatr 9 Suppl 1, 173–176; discussion 177–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cruchaga C, Kauwe JS, Harari O, Jin SC, Cai Y, Karch CM, Benitez BA, Jeng AT, Skorupa T, Carrell D, Bertelsen S, Bailey M, McKean D, Shulman JM, De Jager PL, Chibnik L, Bennett DA, Arnold SE, Harold D, Sims R, Gerrish A, Williams J, Van Deerlin VM, Lee VM, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Haines JL, Mayeux R, Pericak-Vance MA, Farrer LA, Schellenberg GD, Peskind ER, Galasko D, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM, Morris JC, GERAD Consortium G, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), Alzheimer Disease Genetic Consortium (ADGC), Goate AM (2013) GWAS of cerebrospinal fluid tau levels identifies risk variants for Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 78, 256–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Stark SL, Silianoff TJ, Kim HL, Conte JW, Morris JC (2015) Tailored calendar journals to ascertain falls among older adults. OTJR 35, 53–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lamb SE, Jorstad-Stein EC, Hauer K, Becker C (2005) Development of a common outcome data set for fall injury prevention trials: the Prevention of Falls Network Europe consensus. J Am Geriatr Soc 53, 1618–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Su Y, D’Angelo GM, Vlassenko AG, Zhou G, Snyder AZ, Marcus DS, Blazey TM, Christensen JJ, Vora S, Morris JC, Mintun MA, Benzinger TL (2013) Quantitative analysis of PiB-PET with FreeSurfer ROIs. PLoS One 8, e73377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Su Y, Blazey TM, Snyder AZ, Raichle ME, Marcus DS, Ances BM, Bateman RJ, Cairns NJ, Aldea P, Cash L, Christensen JJ, Friedrichsen K, Hornbeck RC, Farrar AM, Owen CJ, Mayeux R, Brickman AM, Klunk W, Price JC, Thompson PM, Ghetti B, Saykin AJ, Sperling RA, Johnson KA, Schofield PR, Buckles V, Morris JC, Benzinger TLS, Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (2015) Partial volume correction in quantitative amyloid imaging. Neuroimage 107, 55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jack CR Jr., Petersen RC, Xu YC, Waring SC, O’Brien PC, Tangalos EG, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Kokmen E (1997) Medial temporal atrophy on MRI in normal aging and very mild Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 49, 786–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jack CR Jr., Dickson DW, Parisi JE, Xu YC, Cha RH, O’Brien PC, Edland SD, Smith GE, Boeve BF, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E, Petersen RC (2002) Antemortem MRI findings correlate with hippocampal neuropathology in typical aging and dementia. Neurology 58, 750–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ossenkoppele R, Cohn-Sheehy BI, La Joie R, Vogel JW, Moller C, Lehmann M, van Berckel BN, Seeley WW, Pijnenburg YA, Gorno-Tempini ML, Kramer JH, Barkhof F, Rosen HJ, van der Flier WM, Jagust WJ, Miller BL, Scheltens P, Rabinovici GD (2015) Atrophy patterns in early clinical stages across distinct phenotypes of Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp 36, 4421–4437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Thomas JB, Brier MR, Bateman RJ, Snyder AZ, Benzinger TL, Xiong C, Raichle M, Holtzman DM, Sperling RA, Mayeux R, Ghetti B, Ringman JM, Salloway S, McDade E, Rossor MN, Ourselin S, Schofield PR, Masters CL, Martins RN, Weiner MW, Thompson PM, Fox NC, Koeppe RA, Jack CR Jr., Mathis CA, Oliver A, Blazey TM, Moulder K, Buckles V, Hornbeck R, Chhatwal J, Schultz AP, Goate AM, Fagan AM, Cairns NJ, Marcus DS, Morris JC, Ances BM (2014) Functional connectivity in autosomal dominant and late-onset Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol 71, 1111–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Brier MR, Gordon B, Friedrichsen K, McCarthy J, Stern A, Christensen J, Owen C, Aldea P, Su Y, Hassenstab J, Cairns NJ, Holtzman DM, Fagan AM, Morris JC, Benzinger TL, Ances BM (2016) Tau and Abeta imaging, CSF measures, and cognition in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Transl Med 8, 338ra366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Brier MR, Thomas JB, Snyder AZ, Benzinger TL, Zhang D, Raichle ME, Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Ances BM (2012) Loss of intranetwork and internetwork resting state functional connections with Alzheimer’s disease progression. J Neurosci 32, 8890–8899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Power JD, Cohen AL, Nelson SM, Wig GS, Barnes KA, Church JA, Vogel AC, Laumann TO, Miezin FM, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE (2011) Functional network organization of the human brain. Neuron 72, 665–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Rousset OG, Collins DL, Rahmim A, Wong DF (2008) Design and implementation of an automated partial volume correction in PET: application to dopamine receptor quantification in the normal human striatum. J Nucl Med 49, 1097–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wisch JKRC, Babulal GM, et al. (2019) Longitudinal changes in functional connectivity in conversion to symptomatic AD. Poster presented at Human Amyloid Imaging Conference, Miami, FL. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Smith RX, Tanenbaum A, Strain JF, Gordon BA, Fagan AM, Hassenstab J, McDade E, Xiong C, Chhatwal JP, Morris JC, Benzinger TLS, Bateman RJ, Ances BM (2018) Resting-state functional connectivity is associated with pathological biomarkers in autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 14, P1480. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Goh JO (2011) Functional dedifferentiation and altered connectivity in older adults: neural accounts of cognitive aging. Aging Dis 2, 30–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].R Core Team (2018) R: A Language And Environment For Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kim S (2015) ppcor: partial and semi-partial (part) correlation. In R Package Version 1.1.

- [34].Wickham H (2016) ggplot2: Elegant Graphics For Data Analysis, Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kassambara A (2018) ggpubr: ‘ggplot2’ based publication ready plots in R Package Version 0.2.

- [36].Greicius MD, Srivastava G, Reiss AL, Menon V (2004) Default-mode network activity distinguishes Alzheimer’s disease from healthy aging: evidence from functional MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 4637–4642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Camicioli R, Howieson D, Oken B, Sexton G, Kaye J (1998) Motor slowing precedes cognitive impairment in the oldest old. Neurology 50, 1496–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Fitzpatrick AL, Buchanan CK, Nahin RL, Dekosky ST, Atkinson HH, Carlson MC, Williamson JD (2007) Associations of gait speed and other measures of physical function with cognition in a healthy cohort of elderly persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 62, 1244–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Albers MW, Gilmore GC, Kaye J, Murphy C, Wingfield A, Bennett DA, Boxer AL, Buchman AS, Cruickshanks KJ, Devanand DP, Duffy CJ, Gall CM, Gates GA, Granholm AC, Hensch T, Holtzer R, Hyman BT, Lin FR, McKee AC, Morris JC, Petersen RC, Silbert LC, Struble RG, Trojanowski JQ, Verghese J, Wilson DA, Xu S, Zhang LI (2015) At the interface of sensory and motor dysfunctions and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 11, 70–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.