Abstract

Background:

There is an increasing demand to incorporate patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) such as quality of life (QOL) in decision-making when selecting a chronic dialysis modality.

Objective:

To compare the change in QOL over time among similar patients on different dialysis modalities to provide unique and novel insights on the impact of dialysis modality on PROMs.

Design:

Systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, and nonrandomized controlled trials were examined via a comprehensive search strategy incorporating multiple bibliographic databases.

Setting:

Data were extracted from relevant studies from January 1, 2000 to December 31, 2019 without limitations on country of study conduction.

Patients:

Eligible studies included adults (≥18 years) with end-stage kidney disease of any cause who were prescribed dialysis treatment (either as lifetime treatment or bridge to transplant).

Measurements:

The 5 comparisons were peritoneal dialysis (PD) vs in-center hemodialysis (ICHD), home hemodialysis (HHD) vs ICHD, HHD modalities compared with one another, HHD vs PD, and self-care ICHD vs traditional nurse-based ICHD.

Methods:

Included studies compared adults on different dialysis modalities with repeat measures within individuals to determine changes in QOL between dialysis modalities (in-center or home dialysis). Methodological quality was assessed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN 50) checklist. A narrative synthesis was conducted, synthesizing the direction and size of any observed effects across studies.

Results:

Two randomized controlled trials and 9 prospective cohort studies involving a combined total of 3711 participants were included. Comparing PD and ICHD, 5 out of 9 studies found significant differences (P < .05) favoring PD in the change of multiple QOL domains, including “physical component score,” “role of social component score,” “cognitive status,” “role limitation due to emotional function,” “role limitation due to physical function,” “bodily pain,” “burden of kidney disease,” “effects of kidney disease on daily life,” “symptoms/problems,” “sexual function,” “finance,” and “patient satisfaction.” Conversely, 3 of these studies demonstrated statistically significant differences (P < .05) favoring ICHD in the domains of “role limitation due to physical function,” “general health,” “support from staff,” “sleep quality,” “social support,” “health status,” “social interaction,” “body image,” and “overall health.” Comparing HHD and ICHD, significant differences (P < .05) favoring HHD for the QOL domains of “general health,” “burden of kidney disease,” and the visual analogue scale were reported.

Limitations:

Our study is constrained by the small sample sizes of included studies, as well as heterogeneity among both study populations and validated QOL scales, limiting inter-study comparison.

Conclusions:

We identified differences in specific QOL domains between dialysis modalities that may aid in patient decision-making based on individual priorities.

Trial registration:

PROSPERO Registration Number: CRD42016046980.

Primary funding source:

The original research for this study was derived from the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) 2017 optimal use report, titled “Dialysis Modalities for the Treatment of End-Stage Kidney Disease: A Health Technology Assessment.” The CADTH receives funding from Canada’s federal, provincial, and territorial governments, with the exception of Quebec.

Keywords: health-related quality of life, quality of life, dialysis choice, dialysis, peritoneal dialysis

Abrégé

Contexte:

On observe une demande croissante pour intégrer des mesures des résultats déclarées par les patients (MRDP) comme la qualité de vie (QDV) dans la prise de décision quant à la modalité de dialyse.

Objectif:

Comparer l’évolution de la QDV chez des patients de profils similaires, mais utilisant différentes modalités de dialyse, pour fournir un éclairage nouveau sur l’incidence de la modalité sur les MRDP.

Type d’étude:

Des revues systématiques et des essais contrôlés avec ou sans répartition aléatoire ont été examinés dans le cadre d’une stratégie de recherche globale incorporant plusieurs bases de données bibliographiques.

Conception:

Les données ont été extraites des études pertinentes entre le 1er janvier 2000 et le 31 décembre 2019 sans limitation relativement à l’origine (pays) de l’étude.

Sujets:

Les études admissibles portaient sur des adultes atteints d’insuffisance rénale terminale (toutes causes) auxquels un traitement de dialyse avait été prescrit, soit comme traitement à vie, soit en attendant une transplantation.

Mesures:

Ont été comparées 1) la dialyse péritonéale [DP] vs l’hémodialyse en centre [HDC]; 2) l’hémodialyse à domicile [HDD] vs l’HDC; 3) les modalités d’HDD les unes aux autres; 4) l’HDD vs la DP; et 5) l’HDC autogérée vs l’HDC traditionnelle sous supervision d’une infirmière.

Méthodologie:

Les études incluses comparaient des adultes sous différentes modalités de dialyse et comportaient des mesures répétées permettant d’observer des changements dans la QDV selon la modalité (en centre ou à domicile). La qualité méthodologique a été évaluée avec la grille d’évaluation du Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN 50). Une synthèse narrative a été réalisée pour résumer la direction et l’ampleur de tous les effets observés dans les différentes études.

Résultats:

Ont été inclus deux essais contrôlés à répartition aléatoire et neuf études de cohorte prospectives (3 711 patients au total). En comparant la DP à l’HDC, cinq des neufs études rapportaient des différences significatives (P<0,05) favorisant la DP dans plusieurs aspects de la QDV, notamment quant au « score de la composante physique », au « rôle du score de la composante sociale », à « l’état cognitif », à la « limitation dans les activités quotidiennes en raison des aspects émotionnels », à la « limitation dans les activités quotidiennes en raison des aspects physiques », à la « douleur physique », au « fardeau de la néphropathie », aux « conséquences de la néphropathie sur la QDV », aux « symptômes/problèmes », à la « fonction sexuelle », aux « conséquences financières » et à la « satisfaction du patient ». En revanche, trois de ces études montraient des différences statistiquement significatives (P<0,05) favorisant l’HDC dans les aspects suivants: « limitation dans les activités quotidiennes en raison des aspects physiques », « état de santé général », « soutien du personnel soignant », « qualité du sommeil », « soutien social », « état de santé », « interactions sociales », « image corporelle » et « état de santé global ». En comparant l’HDD et l’HDC, des différences significatives (P<0,05) favorisant l’HDD ont été rapportées en ce qui concerne « l’état de santé général », le « fardeau de la néphropathie » et l’échelle visuelle analogique.

Limites:

L’étude est limitée par la faible taille des échantillons des études incluses, ainsi que par l’hétérogénéité des populations et des échelles validées pour la mesure de la QDV, ce qui restreint les comparaisons entre les études.

Conclusion:

Des différences significatives touchant certains aspects propres à la qualité de vie ont été observées entre les différentes modalités de dialyse. Ces observations pourraient orienter une prise de décision en fonction des priorités individuelles des patients.

What was known before

Quality of life (QOL) measures are a key patient-reported outcome and may facilitate decision-making when choosing dialysis modalities. As direct comparisons of QOL between the different dialysis modalities are difficult due to inherent differences between the 2 groups, QOL changes over time may be more informative.

What this adds

In this systematic review, we synthesized the literature on QOL differences between the various dialysis modalities focusing on changes over time. Examining 11 studies with a total of 3711 patients, we identified a number of specific QOL domains that changed over time between the different dialysis modalities.

Impact

The identified differences in specific quality of life domains between dialysis modalities may aid in patient decision-making based on individual priorities.

Background

There are an increasing number of patients globally requiring chronic dialysis for the treatment of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), with in-center hemodialysis (ICHD), and peritoneal dialysis (PD) remaining the most common modalities. Despite the discordant uptake of ICHD over home dialysis modalities, limited empirical evidence to date suggests that clinical outcomes, such as survival, are comparable between groups.1,2 Clinical studies examining outcomes have proven to be difficult as autonomous patients often have a preference among offered dialysis modalities and so are reluctant to consent to being randomized. As a consequence, most of the evidence is based on observational data with its inherent limitations, the most prominent being confounding by treatment indication (patients who choose home dialysis modalities are healthier, on average).3 As high-quality evidence guiding the selection of the optimal dialysis modality is lacking, decision-making regarding dialysis modality should incorporate other metrics, particularly patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) such as quality of life (QOL) and patient satisfaction.4,5 Of concern, it has been suggested that dialysis modality selection process may not accurately reflect patient choice.4 Recent policy changes in the United States (The Advancing American Kidney Health Executive Order) have acknowledged existing barriers to home dialysis utilization and employed a series of incentives to reduce ICHD. From a health provider perspective, there are clear cost-related differences in the dialysis modalities, with home modalities being more cost effective than in-center dialysis delivery.6,7

As patients on the various dialysis modalities often differ significantly in terms of demographics, comorbidities, motivation, and functional status, direct comparisons in QOL outcomes between patient groups become problematic. However, comparisons of the change in QOL over time among similar patients on different dialysis modalities may provide unique and novel insights on the impact of dialysis modality on PROMs. We updated a systematic review originally conducted by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH)8,9 as a broader health technology assessment focusing specifically on within individual changes in QOL between the various dialysis modalities.

Methods

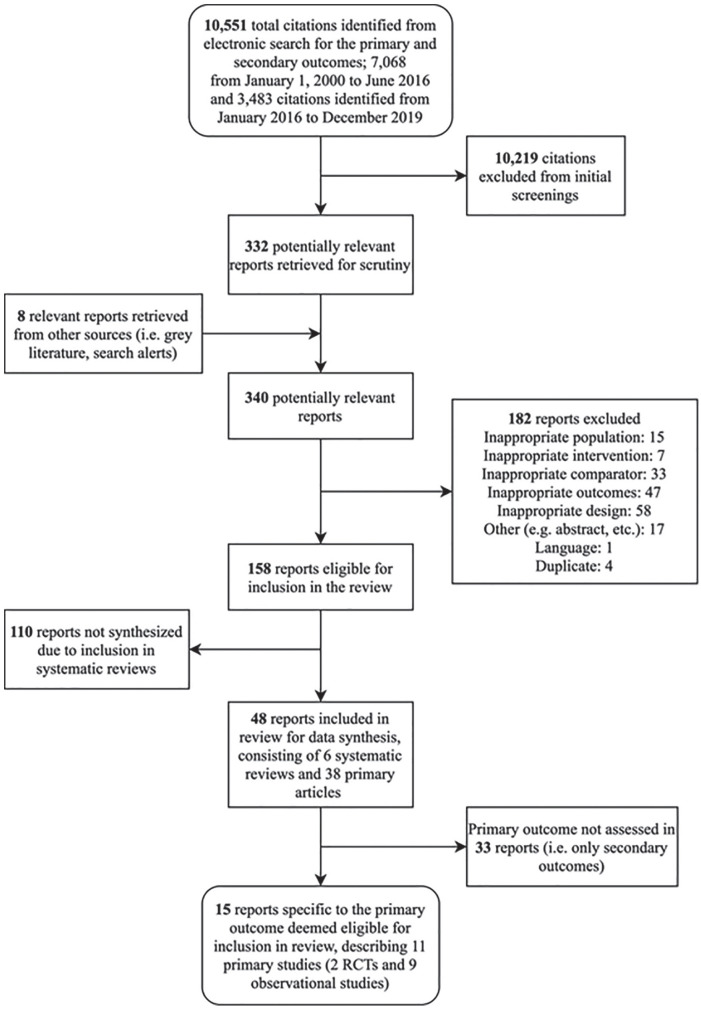

We conducted a systematic review update in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) statement. A flow chart reflecting the study selection for the primary outcome (ie, QOL-related research questions) is outlined in Figure 1. This study is an updated systematic review focusing on a specific objective of an original broader CADTH health technology assessment on dialysis modalities that included evidence synthesis of clinical outcomes, economic analysis, and patient perspectives.8,9

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing selection of studies.

Data Sources and Searches

In brief, the original CADTH report searched the following bibliographic databases: MEDLINE via Ovid; Embase via Ovid; the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials via Ovid; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) via EBSCO; and PubMed for relevant studies.8,9 The search strategy used both MeSH terms and keywords (for full details see the published protocol9). The original search was limited to documents published since January 1, 2000 and the updated search was limited to additional publications from January 1, 2016 to December 31, 2019. The main search concepts were home dialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and self-care in-center dialysis. The search was limited to English- or French-language publications and excluded conference abstracts.

Study Selection Criteria and Research Questions

We included comparative studies that included adults (≥18 years) with ESKD of any cause who were prescribed dialysis treatment (either as lifetime treatment or bridge to transplant) and that included the comparison of interest with respect to the primary outcome, that is, within individual repeat measures of QOL using a standardized tool (generic or dialysis-specific). We performed 5 comparisons in total as follows: (1) PD vs ICHD; (2) home hemodialysis (HHD) vs ICHD; (3) HHD modalities compared with one another, including nocturnal, short-daily, and conventional home hemodialysis (CHHD); (4) HHD vs PD; and (5) self-care ICHD vs traditional nurse-based ICHD.

Included studies were required to report the primary outcome of within individual repeat measures of QOL. Minimal clinically important differences (MCID) were extracted and reported as defined by the original study authors. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts of all citations retrieved from the literature search relevant to Research Questions, followed by an independent review of the full-text articles with subsequent discussion and consensus of excluded and included studies. A single reviewer extracted data from each paper, and a second reviewer checked the extracts for accuracy. Disagreements between extractor and reviewer were resolved through discussion, involving a third reviewer, if necessary.

Data Extraction and Quality Appraisal

A priori, it was planned to treat the different prescriptions of HD (ICHD, short-daily HD, and nocturnal HD) as distinct. When studies did not specify the HD modality used, it was assumed to be ICHD. In the absence of other forms of heterogeneity, it was planned to pool continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) and automated peritoneal dialysis (APD) as a single group receiving PD. The following data were extracted by a single reviewer from the original CADTH report and any articles identified in the updated search: study design; inclusion and exclusion criteria for patients; method of assigning patients to treatment groups; details of intervention and control; setting and type of assistance with dialysis; number of patients in each group; demographic and clinical information for patients; relationship and demographics for carers; QOL measures, QOL measurement, scale and domain, and minimally clinical important difference, if reported. No formal assessment of inter-rater agreement was used. The methodological quality of included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and nonrandomized studies was evaluated using the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN 50) checklist for controlled trials for internal validity and overall assessment. For all study types, an overall rating of “High Quality” (++), “Acceptable” (+), “Low Quality” (−), and “Unacceptable—reject” was assigned to the study as recommended by SIGN and based on the reviewers’ confidence regarding the attempt to minimize bias, accompanied by an overall evaluation of the methodology used, the statistical power of the study, and level of certainty that the overall effect observed is because of the study intervention.8 Primary studies were not excluded on the basis of quality appraisal, though quality was considered in formulating conclusions regarding strength of evidence and risk of bias.8,9

Data Synthesis and Analysis

A narrative synthesis was conducted, presenting findings within summary tables and texts, and describing study and clinical characteristics believed to contribute to heterogeneity, as determined during our exploration of the data. The aim was to synthesize the direction and size of any observed effects across studies in the absence of a meta-analysis.

Results

Selection and Description of Studies

We identified 10 551 studies prior to initial full-text screening. Of these, 15 papers describing 11 primary studies, assessing a total of 3711 patients, were included (see Figure 1) for the primary outcome (ie, QOL) of the 5 research questions. The original CADTH report included 7 studies with the literature update adding 4 studies.10-13 Of the included 8 primary studies, 2 were RCTs (described by 6 articles)14-19 and 9 were nonrandomized studies of prospective cohorts10-13,20-24 (see Table 1). Nine of the studies compared PD with ICHD,10-13,20-24 1 compared nocturnal home hemodialysis (NHHD) with ICHD,18,19 and 1 compared NHHD with CHHD.14-17 The mean patient ages between studies ranged from 51.6 to 77 (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Study Characteristics of Included Studies.

| Study Country Study design |

Stated study objective | Name of trial/registry Years of recruitment Length of follow-up |

Funding source Author conflicts |

Dialysis modalities Total no. of patients (N) Incident or prevalent patients |

Inclusion/exclusion criteria | Primary/secondary outcomes of interest | Analytic model Model covariates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culleton et al18 and Manns et al19

Canada RCT |

Comparison of frequent nocturnal HD vs conventional HD on changes in left ventricular mass and HRQOL over 6 mo | Trial name NR 2004-2006 Follow-up to Dec 2006 |

Funded by the Kidney Foundation of Canada Authors declare no conflict of interest |

Nocturnal HHD, conventional HD N = 52 Prevalent patients |

Inclusion: patients age ≥18 y, receiving in-center, self-care, or home conventional HD 3 times weekly, and interested in training for nocturnal HHD Exclusion: patients lacking the mental or physical capacity to train for nocturnal HHD |

Primary: Cognitive functioning | Intent-to-treat with last value carried forward approach; sensitivity analysis of using covariance (ANCOVA) Covariates: ANCOVA model: 6-mo value was the dependent variable, and baseline value was the covariate |

| de Abreu et al23

Brazil Prospective cohort |

Comparison of the QOL in patients on HD or PD in Brazil | Trial name NR 2007-2009 12 mo follow-up |

Funded by Baxter Healthcare Corp One author employed by Baxter |

PD, HD N = 350 Prevalent patients |

Inclusion: Patients at one of 6 dialysis centers, aged ≥18 y who had been on the same dialysis modality for at least 1 mo Exclusion: hospitalized patients and those who planned to change modality within 6 mo |

Primary: HRQOL Secondary: NR |

Multivariate regression to compare influence of dialysis modality on QOL for the 3 time periods and from baseline to 12 mo Covariates: included demographics, comorbidities, lab values, time receiving dialysis, type of health insurance (public or private) |

| Frimat et al21

France Prospective cohort |

Comparison of in patients contra-indicated for kidney transplant, who were only on HD and those given PD as a first RRT | Epidémiologie de l’insuffisance renale chronique terminale en Lorraine (EPIREL) 1997-1999 13-24 mo follow-up |

Govt funding Author declare no conflict of interest NR |

PD, ICHD N = 387 (321 for QOL analysis) Incident patients |

Inclusion: Patients with kidney failure, living in Lorraine France for ≥3 mo, and began RRT between June 1997 and June 1999 Exclusion: patients with acute reversible renal failure or those returning to dialysis following kidney graft failure; age <15 y |

Primary: mortality Secondary: HRQOL, hospitalization |

Multivariate analysis for analysis of variance and covariance Covariates: age, sex, comorbidity index, first dialysis session (planned vs unplanned) |

| Harris et al24

UK Prospective cohort |

Comparison of the effect of dialysis modality on in elderly patients on PD vs HD | North Thames Dialysis Study (NTDS) 1995-1996 12 mo follow-up |

Govt funding Author no conflict of interest NR |

PD, ICHD N = 174 Incident and prevalent patients |

Inclusion: patients aged ≥70 y, with 90 days of uninterrupted chronic dialysis Exclusion: patients with terminal illness with life expectancy of <6 mo; diagnosis of psychosis; cognitive impairment |

Primary: survival, hospitalization, QOL Secondary: NR |

Cox proportional hazards models, Poisson regression models, multiple linear regression analyses Covariates: study cohort, time on dialysis, age, sex, social class (manual or nonmanual occupation), and comorbidity |

| Manns et al22

Canada Prospective cohort |

Comparison of HRQOL in patients receiving HD or PD | Name of trial NR 1999-1999 12-mo follow-up |

Govt funding Various authors work for university or the Institute of Health Economics (Alberta) |

PD (continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis and cyclic PD), HD (ICHD, satellite, home or self-care; 71.5% ICHD) N = 192 Prevalent patients (>6 mo) |

Inclusion: patients on HD or PD for >6 mo Exclusion: dementia, inability to speak English, unwilling or unable to complete HRQOL questionnaires |

Primary: HRQOL Secondary: NR |

Multiple linear regression Covariates: NR |

| Rocco et al15

Rocco et al14 Unruh et al17 Unruh et al16 Canada and USA RCT with prospective cohort extension study |

Comparison of frequent nocturnal HHD 6 times per week with conventional 3 times per week HD | Frequent Hemodialysis Network (FHN) Nocturnal Trial 2006-2009 Follow-up to May 2010, with extension to Jul 2011 |

Funded by National Institute of Health, National Institutes Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), Center for Medicare and Medical Services (CMS) Several authors have affiliations with industry |

Conventional HHD (3 times/wk; <5 h/session), nocturnal HHD (6 times/wk; ≥6 h/session) N = 87 (extension study N = 83 at 1 y and N = 70 at 2 y) Prevalent patients |

Inclusion: Patients age ≥18 y with kidney failure, who achieved mean dialysis adequacy measurement of ≥1.0 for last 2 baseline HD sessions Exclusion: current requirement for HD more than 3 times/wk; GFR >10 mL/1.73 m2, <3 mo since kidney transplant failure, life expectancy <6 mo |

Primary: all-cause mortality/survival Secondary: hospitalization, self-reported depression, transplant, adverse events, technical adverse events |

Log-rank test, Cox proportional hazards regression Covariates: diabetes, age and baseline GFR (for time to death, first nonaccess hospitalization/death, and first access intervention) |

| Wu et al20

USA Prospective cohort |

Comparison of self-reported HRQOL and overall health status for HD and PD patients at the initiation of dialysis therapy and after 1 y | Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for kidney failure (CHOICE) 1995-1998 12-mo follow-up |

Funded by govt agencies One author is supported by one of the govt agencies |

PD, ICHD N = 928 (585 completed 12-mo questionnaire) Incident patients |

Inclusion: age ≥18 y, initiating dialysis Exclusion: HHD patients |

Primary: HRQOL Secondary: NR |

Intention-to-treat; difference in modalities compared using t tests (unadjusted) or Wald test (adjusted) Covariates: age, sex, race, education, albumin, creatinine, hematocrit, and Index of Co-existent Disease (ICED) score |

| Hiramatsu et al10

Japan Prospective cohort study |

Comparison of HRQOL over time for HD and PD patients at time of initiation, 12 mo, and 24 mo | Name of trial NR October 2013—December 2016 2-y follow-up |

No conflict of interest to disclose | PD, ICHD N = 75 (56 completed 24-mo questionnaire) Incident patients |

Inclusion: Patients with kidney failure referred for RRT who independently chose PD or HD. Exclusion: Patients unable to answer the questionnaire themselves |

Primary: HRQOL Secondary: Depressive state, grip strength, cognitive impairment 24-hour urine volume |

Data between groups analyzed with Student t test, Mann-Whitney U test or χ2 square test. Treatment and times were included as main effects for repeated measured variables with treatment × time used as an interaction and analyzed with the linear mixed model using compound symmetry covariance pattern. Covariates: Age, sex, comorbidities, lab values |

| Neumann et al11

Germany Prospective cohort study |

Comparison of KDQOL domain of cognitive functioning over time for HD and PD patients at time of initiation and 12 mo | Choice of Renal Replacement Therapy (CORETH) Project May 2014—May 2015 12-mo follow-up |

CORETH project funded by German Federal Ministry of Education and Research | PD, ICHD N = 271 Prevalent patients |

Inclusion: Patients ≥18 y among 55 dialysis units in Germany, initiated on dialysis 6 to 24 mo prior to baseline evaluation Exclusion: Patients unable to understand or answer the questionnaire themselves, and patients with acute psychiatric symptoms |

Primary: HRQOL Secondary: NR |

Treatment and times were included as main effects for repeated measured variables with treatment × time used as an interaction and analyzed with the linear mixed modeling with maximum likelihood estimation Covariates: Age, education level, employment status, comorbidities |

| Jung et al12

South Korea Prospective cohort study |

Comparison of HRQOL over time for HD and PD patients at time of initiation, 3-, 12- and 24 mo, and 24 mo | Comprehensive Prospective Study for Mode of Dialysis Therapy and Outcomes in ESRD July 2009 to September 2018 2-y follow-up |

Grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute | PD, ICHD N = 989 (who completed 3-mo questionnaire, 2492 completed 12-mo questionnaire, and 262 completed 24-mo questionnaire) Incident patients |

Inclusion: Patients ≥19 y with ESRD able to give informed consent who are initiating dialysis in South Korea Exclusion: Patients scheduled for kidney transplant or emigration to foreign country within 3 mo. Patients with acute renal failure |

Primary: HRQOL Secondary: Associated factors related to persistently impaired HRQOL |

Baseline markers were compared using Pearson χ2 square test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables and using the Student t test for continuous variables. Differences in questionnaire scores at each time point between dialysis modality were analyzed from adjusted regression analyses. Effects of dialysis modality, time, and their interaction required repeated measures ANOVA Covariates: Age, sex, body mass index, education, employment, marital status, lab values, primary cause of renal disease |

| Iyasere et al13

United Kingdom Prospective cohort study |

Comparison of HRQOL over time for HD and PD patients at time of initiation and every 3 mo for 2 y | Name of trial NR September 2011 to December 2013 2-y follow-up |

One author received speaking honoraria and research funding from Baxter Healthcare | PD, ICHD N = 206 Prevalent patients |

Inclusion: Patients ≥60 y who had been on dialysis >3 mo and free of hospital admission >30 d Exclusion: Patients with life expectancy <6 mo, dementia, inability to understand English, or lack of informed consent |

Primary: HRQOL Secondary: NR |

Categorical variables were compared between the HD and PD cohorts using Fisher exact tests. Continuous variables were compared at baseline, using the Mann-Whitney test. A linear mixed model approach was used to evaluate the marginal effects of risk factors or covariates for each outcome measure. Covariates: Age, sex, ethnicity, comorbidities |

Note. RCT = randomized controlled trial; HD = hemodialysis; HRQOL = health-related quality of life; HHD = home hemodialysis; QOL = quality of life; PD = peritoneal dialysis; NR = not reported; ICHD = in-center hemodialysis; RRT = renal replacement therapy; govt = government; GFR = glomerular filtration rate; ESRD = end-stage renal disease.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics of Included Studies.

| Study | Dialysis modality | Number of patients | Age, mean (±SD) | Male, No. % | Frequency and no. of h of dialysis | Vascular access | Comorbidities, No. % | Duration of dialysis at start of study; RRF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culleton et al18

Manns et al19 |

Frequent nocturnal HHD | 26 | 55.1 (12.4) | 18 (69%) | 5-6 sessions/wk; minimum 6 h/night | Arteriovenous fistula: 15 (58%); tunneled dialysis catheter: 7 (27%); AV graft: 4 (15%) | CVA 5 (19%); IHD 10 (38%); CHF 6 (23%); PVD 4 (15%); diabetes 10 (38%) | Duration at start of study: mean 5.5 y RRF NR |

| Conventional HD | 25 | 53.1 (13.4) | 14 (56%) | 3 sessions/wk | AV fistula: 14 (56%); tunneled dialysis catheter: 6 (24%); AV graft: 5 (20%) | CVA 3 (12%); IHD 10 (40%); CHF 5 (20%); PVD 4 (16%); diabetes 11 (44%) | Duration at start of study: mean 4.8 y RRF NR |

|

| de Abreu et al23 | PD | 161 | 59.6 (13.8) | 48.4% | NR | NR | CHD 83 (51.6%); cardiac arrhythmias 28 (17.4%); hypertension 147 (91.9%); CHF 28 (17.4%); PVD 18 (11.2%); stroke 19 (11.8%); cancer 5 (3.1%); diabetes 110 (68.3%) | Duration at start of study: mean 3.28 (SD ±1.78) y RRF NR |

| HD | 189 | 55.6 (14.8) | 50.3% | NR | NR | CHD 106 (56.1%); cardiac arrhythmias 21 (11.6%); hypertension 159 (84.4%); CHF 28 (15.3%); PVD 20 (10.6%); stroke 14 (7.4%); cancer 5 (2.7%); diabetes 109 (57.7%) | Duration at start of study: mean 3.95 (SD ±2.18) y RRF NR |

|

| Frimat et al21 | PD | 184 | 70.8 (11.4) | 58 (56.3%) | NR | NR | CHD 45 (43.7%); CHF 33 (32.0%); CVA 23 (22.3%); PVD 31 (30.1%); diabetes 38 (36.9%) | Duration NR (incident patients) RRF NR |

| HD | 284 | 67.6 (11.3) | 170 (59.9%) | At 6 mo: 13.6/wk ±3.1 h; At 12 mo: 13.9/wk ± 3.8 h |

NR | CHD 101 (35.6%); CHF 106 (37.3%); CVA 45 (15.9%); PVD 110 (38.7%); diabetes 111 (39.1%) | Duration NR (incident patients) RRF NR |

|

| Harris et al24 | PD | 78 (36 incident) | 76.8 (4.0); range 70-91 | 55 (70%) | NR (majority of patients received continuous ambulatory PD) | NR | Reported as conditions (presence of diabetes, IHD, PVD, CVA, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or cancer) None: 19 (24%); 1 condition: 29 (37%); 2 or more conditions: 30 (39%) |

Duration NR RRF NR |

| ICHD | 96 (42 incident) | 77.0 (4.4); range 70-93 | 60 (62%) | NR | NR | None: 20 (21%); 1 condition: 32 (33%); 2 or more conditions: 44 (46%) | Duration NR RRF NR |

|

| Manns et al22 | PD | 41 | 56.1 (95% CI 48.8-63.4) | 20 (48.7%) | NR | NR | Diabetes 15 (36.6%) | Duration at start of study: median 23 mo (IQR: 10-42) RRF NR |

| HD | 151 | 62.2 (95% CI 59.2-65.3) | 87 (57.6%) | 3 sessions/wk for ≥4 h | NR | Diabetes 36 (23.8%) | Duration at start of study: median 22 mo (IQR: 9-44) RRF NR |

|

| Intensive HHD | 375 | 49.8 (15.7) | 291 (78%) | ≥5 sessions/wk; any h/session | NR | PVD 82 (22%); CVA 31 (8%); lung disease 56 (15%); coronary artery disease 116 (31%); type 1 diabetes 11 (3%); type 2 diabetes 120 (32%) | Duration NR RRF: estimated glomerular filtration rate (mL/min/1.73 m²), median 5.3 (IQR: 3.5) |

|

| Rocco et al15

Rocco et al14 Unruh et al17 Unruh et al16 |

Nocturnal HHD | 45 | 51.7 (14.4) | 29 (64%) | Mean 5.06 (SD ±0.80) sessions/wk; session time mean 379 (SD ±62) min; total time mean 30.8 (SD ±9.1) h/wk | Fistula 49%; synthetic graft 7%; catheter 44% | PVD 8 (18%); chronic pulmonary disease 2 (4%); stroke/CVA 1 (2%); heart failure 5 (11%); MI 5 (11%); hypertension 41 (91%); diabetes 19 (42%) | Duration NR RRF (urea clearance in mL/min): Anuric = 29%; >0-1 =16%; >1-3 = 36%; >3 +20% |

| Conventional HHD | 42 | 54.0 (12.9) | 28 (67%) | Mean 2.91 (SD ±0.21) sessions/wk; session time mean 256 (SD ±65) min; total time mean 12.6 (SD ±3.9) h/wk | Fistula 41%; synthetic graft 10%; catheter 50% | PVD 7 (17%); chronic pulmonary disease 2 (5%); stroke/CVA 1 (2%); heart failure 7 (17%); MI 4 (10%); hypertension 39 (93%); diabetes 18 (43%) | Duration NR RRF (urea clearance in mL/min): Anuric = 26%; >0-1 = 21%; >1-3 = 33%; >3 = 19% |

|

| Wu et al20

reporting baseline data of total cohort, as this study was ITT. There is also data for 1-y cohort |

PD | 230 | 54 | 125 (54%) | NR geographical location data also available (ie, urban or rural) |

NR | ICED 1-2: 111 (48%) 2: 60 (26%) 3: 59 (26%) |

Duration NR RRF NR |

| ICHD | 698 | 59 | 366 (52%) | NR | NR | ICED 1-2: 217 (31%) 2: 270 (39%) 3: 210 (30%) |

Duration NR RRF NR |

|

| Hiramatsu et al10 | ICHD | 22 | 66.6 (8.4) | 13 (59%) | NR | NR | Diabetes 8 (36%) | Duration NR (incident patients) RRF (mean urine volume mL/d): Baseline: 820.0 12 mo: 275.0 24 mo: 85.0 |

| PD | 34 | 63.1 (11.0) | 23 (68%) | NR | NR | Diabetes 11 (32%) | Duration NR (incident patients) RRF (mean urine volume mL/d): Baseline: 800.0 12 mo: 500.0 24 mo: 352.0 |

|

| Neumann et al11 | ICHD | 163 | 57.0 (15.0) | 118 (72%) | NR | NR | Neurological/CVA disease 6 (4%) Psychotropic drug intake 31 (19%) |

Duration at start of study, mean 14.8 mo RRF NR |

| PD | 108 | 56.0 (14.7) | 71 (66%) | NR | NR | Neurological/CVA disease 7 (6%) Psychotropic drug intake 14 (13%) |

Duration at start of study, mean 14.8 mo RRF NR |

|

| Jung et al12 | ICHD | 652 | 56.6 (13.5) | 409 (63%) | NR | NR | Diabetes 407 (62%) | Duration NR (incident patients) RRF (mL/min/1.73 m2) 3 mo: 10.7 12 mo: 5.7 24 mo: 4.2 |

| PD | 337 | 51.6 (12.8) | 201 (59.4%) | NR | NR | Diabetes 165 (49%) | Duration NR (incident patients) RRF (mL/min/1.73 m2) 3 mo: 11.1 12 mo: 5.8 24 mo: 4.2 |

|

| Iyasere et al13 | ICHD | 100 | 75 (IQR 69-80) | 57 (57%) | NR | NR | Diabetes 47 (47%); IHD 58 (58%); LVD 20 (20%); PAD 23 (23%); Malignancy 23 (23%); systemic collagen vascular disease 5 (5%) | Duration at start of study, median 29 mo RRF NR |

| PD | 106 | 76 (IQR 69-81) | 41 (39%) | NR | NR | Diabetes 56 (53%); IHD 45 (42%); LVD 23 (22%); PAD 29 (28%); Malignancy 13 (12%); systemic collagen vascular disease 4 (4%) | Duration at start of study, median 24 mo RRF NR |

Note. RRF = residual renal function; HHD = home hemodialysis; AV = arteriovenous; IHD = ischemic heart disease; CHF = congestive heart failure; PVD = peripheral vascular disease; NR = not reported; HD = hemodialysis; PD = peritoneal dialysis; CHD = coronary heart disease; CI = confidence interval; IQR = interquartile range; CVA = cerebrovascular accident; MI = myocardial infarction; ICED = Index of Co-existent Disease; ICHD = in-center hemodialysis; LVD = left ventricular dysfunction; PAD = peripheral artery disease.

PD vs ICHD

Nine nonrandomized studies were retrieved that compared PD and ICHD for QOL and met eligibility criteria, with sample sizes ranging from 75 to 1041 patients.10-13,20-24 These studies reported on various patient scales, including Short-Form 36 (SF-36) which incorporates the Short-Form 12 (SF-12), Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KDQOL), CHOICE Health Experience Questionnaire (CHEQ), EuroQOL-5D-3L, visual analogue scale (VAS), Index Score (IND), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Symptoms score, Barthel score, the Illness Intrusive Rating Scale (IIRS), and the Renal Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (RTSQ). The QOL measurements, measurement technique, and statistical significant domains are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of Quality of Life Changes Comparing PD With In-Center Hemodialysis (ICHD) With Measures of Statistical (P Value).

| Study | QOL scale | QOL measurement | QOL domain | ICHD value | PD value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| de Abreu et al23 | KDQOL | Percentage of patients reporting “better” or “worse” from baseline to 12 mo | Encouragement/support from staff | 21.3% better | 13.0% better | P = .0416 favoring ICHD |

| Sleep quality | 39.6% better | 28.6% better | P = .0360 favoring ICHD | |||

| Social support | 24.3% better | 13.8% better | P = .0134 favoring ICHD | |||

| Health status | 36.2% better | 23.8% better | P = .0120 favoring ICHD | |||

| Cognitive status | 54.3% worse | 39.1% worse | P = .0045 favoring PD | |||

| Overall improvement (stated in study) | P = .004 favoring ICHD | |||||

| Multivariate regression analysis from baseline to 12 mo | Social interaction (stated in study) | ICHD-PD = 4.86 | P = .0275 favoring ICHD | |||

| Patient satisfaction (stated in study) | PD-ICHD = 4.85 | P = .0285 favoring PD | ||||

| Frimat et al21 | SF-36 | Improvement in score from baseline | Role limitation due to physical function | +12.1 at 6 mo +9.2 at 12 mo |

+22.8 at 6 mo +21.2 at 12 mo |

P < .05, favoring PD |

| Role limitation due to emotional function | +7.4 at 6 mo +8.5 at 12 mo |

+27.3 at 6 mo +31.0 at 12 mo |

P < .05, favoring PD | |||

| Bodily pain | +6.7 at 6 mo +3.1 at 12 mo |

+14.7 at 6 mo +10.7 at 12 mo |

P < .05, favoring PD | |||

| KDQOL | Improvement in score from baseline | Burden of Kidney Disease | −3.0 at 6 mo −3.7 at 12 mo |

+13.7 at 6 mo, +10.8 at 12 mo | P < .01, favoring PD | |

| Effects of kidney disease on daily life | −3.8 at 6 mo −5.1 at 12 mo |

+7.8 at 6 mo +5.5 at 12 mo |

P < .05, favoring PD | |||

| Symptoms/ problems | +3.1 at 6 mo +1.2 at 12 mo |

+6.8 at 6 mo +7.0 at 12 mo |

P < .01, favoring PD | |||

| Sexual function | −7.8 at 6 mo −10.2 at 12 mo |

+2.7 at 6 mo, +17.0 at 12 mo | P < .05, favoring PD | |||

| Harris et al24 | KDQOL, SF-36 | Calculated mean differences (95% CI) for PD-ICHD | No significant differences after 12 mo | |||

| Manns et al22 | KDQOL, SF-36, EuroQOL | Improvement in score from baseline | No significant differences after 12 mo | |||

| Wu et al20 | SF-36 | Adjusted mean change from baseline to 1 y | Physical function | +0.4 | −4.5 | P < .05, favoring ICHD |

| General health | +2.8 | −1.0 | P < .05, favoring ICHD | |||

| Choice Health Equality Questionnaire dialysis domains | Adjusted mean change from baseline to 1 y | Sleep | +1.8 | −5.6 | P < .05, favoring ICHD | |

| Finance | −0.4 | +6.2 | P < .05, favoring PD | |||

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) on PD vs HD | Body image | 0.57 (0.33 to 0.99) | P < .05, favoring ICHD | |||

| Hiramatsu et al10 | SF-36 | Mean improvement in score from baseline | Physical component summary | −1.4 at 12 mo, −3.1 at 24 mo | +6.1 at 12 mo, +3.4 at 24 mo | P< .05, favoring PD |

| Role of social component summary | −5.6 at 12 mo, −7.1 at 24 mo | +9.5 at 12 mo, +9.1 at 24 mo | P < .05, favoring PD | |||

| Neumann et al11 | KDQOL | Mean improvement in score from baseline within dialysis modality | Cognitive function | No significant differences after 12 mo | ||

| Jung et al12 | KDQOL | Mean improvement in score from baseline to 24 mo within dialysis modality | Sexual function | −9.6 | P = .005 | |

| Sleep | −2.7 | P = .04, significantly worsened in ICHD | ||||

| Patient satisfaction | −3.5 | P = .04, significantly worsened in ICHD | ||||

| Burden of kidney disease | −5.3 | P = .009, significantly worsened in PD | ||||

| Work status | −6.8 | P = .03, significantly worsened in PD | ||||

| Changes in HRQOL over time between dialysis modalities from baseline to 24 mo | All components of KDQOL | No significant differences after 12- and 24 mos | ||||

| SF-36 | Mean improvement in score from baseline to 24 mo within single dialysis modality | General health | −3.8 | P = .02, significantly worsened in PD | ||

| Emotional well-being | −3.4 | P = .02, significantly worsened in PD | ||||

| Energy/fatigue | −3.1 | P = .04, significantly worsened in PD | ||||

| Role-physical | 10.4 | P = .002, significantly improved in ICHD | ||||

| Changes in HRQOL over time between dialysis modalities from baseline to 24 mo | All components of SF-36 | No significant differences after 12 and 24 mo | ||||

| Beck Depression Index | Changes in HRQOL over time between dialysis modalities from baseline to 24 mo | No significant differences after 12 and 24 mo | ||||

| Iyasere et al13 | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | Changes in HRQOL over time between dialysis modalities from 3 to 24 mo | No significant differences between dialysis modalities in any scoring system after 2 y | |||

| Short-Form 12 | ||||||

| Symptom score | ||||||

| Illness Intrusiveness Rating Scale | ||||||

| Barthel score | ||||||

| Renal Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire | ||||||

Note. PD = peritoneal dialysis; ICHD = in-center hemodialysis; QOL = quality of life; KDQOL = Kidney Disease Quality of Life; SF-36 = Short-Form 36; CI = confidence interval; HRQOL = health-related quality of life.

Eight studies employed SF-36 at multiple time points between baseline and 24 months with absolute mean scores at various time points10,12,13,20-22,24 described in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. Data are also presented as “same/better/worse” from baseline to 12 months,20,23 as seen in Supplementary Table 3. When comparing ICHD and PD for specific SF-36 QOL domains over time, significant differences emerged. Using the SF-36, 2 studies demonstrated significant differences (P < .05) favoring PD over time, with one study reporting improvements in emotional functioning, physical functioning, and bodily pain,21 and the other reporting improvements in the physical component score and the role of social component score.10 Conversely, one study significantly (P < .05) favored ICHD over time in the domains of physical functioning and general health20 (Table 3). One study noted significant domain-specific differences over time within a specific dialysis modality (ie, PD or ICHD), but these differences were no longer significant when comparing the changes in QOL between the 2 modalities.12

Six studies employed the KDQOL scale at multiple time points between baseline and 24 months with absolute mean scores at various time points,11,12,21,22,24 described in Supplementary Table 4. Data are also presented as “same/better/worse” from baseline to 12 months23 (Supplementary Table 5). Certain QOL domains in the KDQOL demonstrated statistical significance (P < .05) favoring PD over time, including cognitive status and patient satisfaction in one study,23 and burden of kidney disease, effects of kidney disease on daily life, symptoms, and sexual function in another.21 Conversely, other QOL domains statistically (P < .05) favored ICHD over time, including the following domains as reported by one study: support from staff, sleep quality, social support, health status, and social interaction23 (Table 3).

One study used the EuroQOL-5D-3L standardized instrument—incorporating the VAS and the IND—to study changes from baseline to 6 and 12 months (Supplementary Table 6).22 Using this scale, no significant differences were identified in either dialysis group.

One study used the CHEQ to examine mean domain scores from baseline to 12 months as an absolute score, as well as via changes in domains scores as reported by percentage of patients that were “same,” “better,” or “worse” (Supplementary Table 7).18 Using this questionnaire, significant differences over time favoring PD were present in the domain of finance, while domains significantly favoring ICHD included sleep and body image (Table 3).

Finally, one study employed multiple scores to evaluate QOL over time between ICHD and PD from 3 to 24 months over 3-month intervals (Supplementary Table 8), including the HADS, Symptoms score, Barthel score, IIRS, and the RTSQ.13 None of these QOL scales demonstrated consistently statistically significance at 3-month intervals up to 24 months.

HDD vs ICHD

Comparing HDD and ICHD, one small RCT (n = 52) met eligibility criteria, comparing NHHD with ICHD from baseline and prerandomization to 6 months18,19 (Table 4). This study demonstrated no significant differences between groups using the EQ-5D-3L version questionnaire (mean difference = 0.05, 95% CI = −0.07 to 0.17) score after 6 months, where higher scores in the scale reflect better QOL (summarized in Supplementary Tables 9 and 10). However, using the VAS of the EQ-5D-3L, a clinically significant difference favoring NHHD was an MCID as defined by a >10-point change. Using the SF-36 and KDQOL scales, no significant differences at baseline in any QOL domains were found. However, after 6 months, there were significant improvements favoring NHHD over ICHD in the domains of “general health” per the SF-36 (mean difference = 12.82, 95% CI = 2.88-22.77) and “burden of kidney disease” per the KDQOL (mean difference = 10.70, 95% CI = 2.42-18.99) scales.

Table 4.

Summary of Quality of Life Changes Over 6 Months Comparing NHHD to ICHD With Measures of Statistical (P Value) and MCID.

| Study | QOL scale | QOL measurement | QOL domain | NHHD value | ICHD value | P value | MCID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culleton et al18 and Manns et al19 | EuroQOL | Between-group mean difference (NHHD-ICHD) comparing baseline and 6 mo | Visual Analogue Score | NA | P = .03, favoring NHHD | >10-point change favoring NHHD | |

| Kidney Disease Quality of Life | Difference in QOL (NHHD-ICHD) comparing prerandomization and 6 mo (95% CI) | Burden of Kidney Disease | NHHD-ICHD = 10.70 (2.42, 18.99) | P = .01, favoring NHHD | |||

| Short-Form 36 | Difference in QOL (NHHD-ICHD) comparing prerandomization and 6 mo (95% CI) | General Health | NHHD-ICHD = 12.82 (2.88, 22.77) | P = .01, favoring NHHD | |||

Note. NHHD = nocturnal home hemodialysis; ICHD = in-center hemodialysis; MCID = minimally clinical important difference; QOL = quality of life; CI = confidence interval.

CHDD vs NHDD

One RCT (n = 87)—the Frequent Hemodialysis Network (FHN) Nocturnal Trial—compared QOL between NHHD (6 times per week, ≥6 hours per session) and CHHD (3 times per week, <5 hours per session) from baseline to 12 months (Table 5).14-17 Using the SF-36 scale, the Beck Depression Inventory, and the Sleep Problems Index, there were no significant improvements in any of the component scores after 12 months in either the NHHD or CHHD groups (summarized in Supplementary Table 11). Calculated mean differences between groups demonstrated no significant differences when compared with each other, with the greatest nonsignificant difference in “energy/fatigue” favoring NHHD (mean difference = 7.2, 95% CI = −3.1 to 17.5). Notably, the NHHD group saw relatively better outcomes in all 5 measured SF-36 domains as compared with CHHD, but relatively worse outcomes in the “Sleep Problems Index” and “Beck Depression Inventory.”

Table 5.

Summary of Quality of Life Changes Comparing NHHD to CHHD Over 12 Months With Measures of Statistical (P Value) and MCID.

| Study | QOL scale | QOL measurement | QOL domain | (F)NHHD value | CHHD value | P value | MCID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unruh et al17 and Unruh et al16 | RAND-36 emotional subscale | Mean change in QOL scores from baseline to 12 mo (±SE) | Mental health composite | +3.0 ± 1.6 | −0.7 ± 1.6 | P > .05 for all 5 domains | Unspecified clinical significance—all 5 domains favor NHHD |

| Emotional well-being | +3.3 ± 2.7 | −2.0 ± 2.7 | |||||

| Role limitation due to emotional problems | +6.6 ± 5.4 | +1.7 ± 5.5 | |||||

| Energy/fatigue | +3.1 ± 3.3 | +0.1 ± 3.3 | |||||

| Social functioning | +7.5 ± 3.9 | +0.3 ± 3.9 | |||||

| Sleep Problems Index | Mean change in QOL scores from baseline to 12 mo (±SE) | −2.0 ± 1.2 | −0.4 ± 1.2 | P > .05 for both domains | Unspecified clinical significance—both domains favor CHHD | ||

| Beck Depression Index | Mean change in QOL scores from baseline to 12 mo (±SE) | −3.3 ± 2.8 | +1.2 ± 2.8 |

Note. NHHD = nocturnal home hemodialysis; ICHD = in-center hemodialysis; MCID = minimally clinical important difference; QOL = quality of life.

PD vs HHD, Self-Care ICHD vs Traditional ICHD

No primary studies comparing PD with HHD or self-care ICHD with traditional ICHD for the endpoint of quality of life were found that met eligibility criteria.

Quality of Studies

The 2 RCTs and 9 observational studies were, on majority, of adequate quality. The RCTs were generalizable and well conducted with the following limitations noted: both included less than 100 patients and the intervention was unable to be blinded to patients or caregivers. Dialysis modality assessment for individual patients would be reliable, and for the outcome of interest, standardized QOL scales were used. The time between repeat QOL measures was variable and not all covariates of interest may have been captured; therefore, residual confounding could not be excluded. Finally, no correction for multiple testing was performed and some of the detected differences in individuals’ QOL domains may arise by chance.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we synthesized the results of published studies that used validated PROMs with a specific emphasis on changes in QOL over time to aid in clinical decision-making regarding optimal dialysis modality. We found no consistent differences in QOL measures comparing home dialysis modalities (ie, HHD or PD) with ICHD; however, differences in distinct QOL domains emerged when comparing these groups over time. Comparing ICHD with PD using multiple validated QOL scales, ICHD was associated with significantly improved outcomes in the domains of “role limitation due to physical function,” “general health,” “support from staff,” “sleep quality,” “social support,” “health status,” “social interaction,” “body image,” and “overall health.” However, PD was associated with significantly better outcomes in “physical component score,” “role of social component score,” “cognitive status,” “role limitation due to emotional function,” “role limitation due to physical function,” “bodily pain,” “burden of kidney disease,” “effects of kidney disease on daily life,” “symptoms/problems,” “sexual function,” “finance,” and “patient satisfaction.” Comparing ICHD with HHD, HHD was associated with statistically significant improvements in “burden of kidney disease,” “general health,” and these differences achieved a minimally clinically important difference threshold compared with ICHD after 6 months. No significant differences were found comparing the specific HHD prescriptions over time. Finally, no studies were available comparing HHD with PD or conventional ICHD with “self-care” ICHD identifying areas of future investigation.

Between the 9 primary studies included in our systematic review comparing PD with ICHD, there were no consistent statistically significant differences in global QOL reported up to 24 months in either the PD or ICHD groups. However, there were significant differences isolated in specific QOL domains when comparing the 2 dialysis prescriptions over time. It is important to recognize that this does not reflect the absolute scores in QOL domains at baseline and each time points, many of which favored PD over ICHD. This highlights the innovation of the present study: our systematic review compares changes in QOL over time between dialysis modalities rather than absolute measures, to circumvent the baseline variations of patient populations that undergo various dialysis treatments.

In the comparison of HHD modalities with ICHD, over 2 decades of slowly growing evidence supports the notion that there may be some benefit to NHHD in the context of health-related quality of life (HRQOL)14,25-28 using various QOL scales, though many of these studies lacked common reporting methods, sufficient sample sizes, and/or adequate statistical analyses. Furthermore, recent literature has suggested that the increased frequency and duration of dialysis inherent to NHHD—which is often more intensive than ICHD—is what correlates with significant improvements in QOL.29 This has been echoed in previous studies, with frequency of dialysis often cited as a major advantage of HHD modalities with respect to QOL.14,28-33 In addition, recent RCTs have demonstrated that these significant QOL benefits occur independent of dialysis location (ie, home or in-center).32,33 Increased frequency of dialysis has also been linked with improved solute clearance, volume control, nutrition, less pill burden, and reduced left ventricular hypertrophy.14,31

Two shortcomings in the present literature were consistent regarding home dialysis modalities: small sample sizes and paucity of studies. This notion is supported by the lack of primary articles to examine further modality comparisons of interest such as PD vs HHD or self-care ICHD vs conventional ICHD. Our updated systematic review is the first to recognize changes in QOL over time as a primary end point, as it is often underappreciated in the literature relative to its importance as a guiding variable in choice of dialysis modality. Our findings clearly underline the importance of advancing research in the field of QOL over time as it relates to home and in-center dialysis modalities, especially with PROMs holding a larger stake in dialysis choice than ever before. Fortunately, several larger studies have begun to investigate this question in recent years. The China Q study by Yu et al (NCT02378350, pending publication) is comparing QOL between 668 patients on either PD or ICHD over 1 year. In addition, a recent large retrospective cohort analysis34 posed a similar question to the present study, comparing health-related QOL over time between patients (n = 5114) who initiated ICHD or home dialysis (PD or HHD) at multiple time points via the KDQOL scale. Despite the relatively large sample size, the study demonstrated no significant differences in QOL over time between groups after 485 days. Unfortunately, this study could not be included in our systematic review owing to the lack of subgroup analysis in the “home dialysis” population (which combined PD and HHD, thereby not meeting our predefined research questions), albeit the large majority consisted of PD patients (93.1%). Despite nonsignificant results, this study demonstrates the movement toward evaluating changes in QOL over time, rather than absolute values.

Our study has several limitations. First, the limited and indeterminate data for the primary end point (ie, QOL), particularly for HHD modalities given the relative infrequency of QOL measures and small sample sizes. Second, of the studies that did fit inclusion criteria, there was considerable heterogeneity among the QOL scales used (eg, CHEQ, SF-36, KDQOL), limiting inter-study comparisons. More recent literature supports only the utility of specific PROMs in dialysis-specific QOL analyses, namely KDQOL-36 and KDQOL-SF.35 Third, from a pragmatic perspective, other clinically relevant variables involved in the decision for dialysis modality were omitted including socioeconomic factors, accessibility, familiarity with dialysis modality (both for physician and patient), ability to change dialysis modalities, caregiver burden, frequency of dialysis, and duration of dialysis session. We also recognize that our study does not compare all combinations of dialysis prescriptions; thus, certain important comparisons are not included (eg, nocturnal ICHD vs NHDD36 or CAPD vs APD).37 Finally, study populations were drawn from different countries and health care systems introducing unavoidable heterogeneity.

Conclusions

In this systematic review examining within patients changes in QOL across the various dialysis modalities, we found no consistent differences in the overall QOL outcomes between home dialysis modalities (including PD and HHD) and ICHD as a change from baseline; however, important differences are present in specific QOL domains. Although there are significant limitations in the ability to compare clinical outcomes between groups, with the improved cost-effectiveness of home dialysis prescriptions, and a growing emphasis on patient-centered dialysis choice, our findings imply that certain patients may benefit from home dialysis modalities depending on their individual preferences and acceptable trade-offs. In light of this, the current underutilization of home dialysis modalities may reflect other variables, including lack of high-quality research, governmental policy, and physician familiarity, all of which may be susceptible to intervention and improved education. Future large-scale research comparing QOL over time between dialysis modalities is critical, especially with the current landscape of dialysis shifting toward patient-centered outcomes.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, CADTH_Supplementary_Tables for A Comparison of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures of Quality of Life By Dialysis Modality in the Treatment of Kidney Failure: A Systematic Review by Brandon Budhram, Alison Sinclair, Paul Komenda, Melissa Severn and Manish M. Sood in Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Karen Cimon from CADTH.

Footnotes

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: Not applicable.

Consent for Publication: Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: P.K. is the CMO—Quanta Dialysis Technologies.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: M.M.S. has received CME speaker fees from Astrazeneca. M.M.S. is supported by the Jindal Research Chair for the Prevention of Kidney Disease.

ORCID iD: Manish M. Sood  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9146-2344

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9146-2344

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Couchoud C, Bolignano D, Nistor I, et al. Dialysis modality choice in diabetic patients with end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review of the available evidence. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(2):310-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pike E, Hamidi V, Ringerike T, et al. Health technology assessment of the different dialysis modalities in Norway. Oslo, Norway: Knowledge Centre for the Health Services at The Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH), NIPH Systematic Reviews, The Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH); 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jiwakanon S, Chiu YW, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Mehrotra R. Peritoneal dialysis: an underutilized modality. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2010;19(6):573-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Morton RL, Tong A, Howard K, Snelling P, Webster AC. The views of patients and carers in treatment decision making for chronic kidney disease: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ. 2010;340:c112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Harwood L, Clark AM. Understanding pre-dialysis modality decision-making: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(1):109-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Walker R, Marshall MR, Morton RL, McFarlane P, Howard K. The cost-effectiveness of contemporary home haemodialysis modalities compared with facility haemodialysis: a systematic review of full economic evaluations. Nephrology (Carlton). 2014;19(8):459-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pike E, Hamidi V, Ringerike T, Wisloff T, Klemp M. More use of peritoneal dialysis gives significant savings: a systematic review and health economic decision model. J Clin Med Res. 2017;9(2):104-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Canada. Dialysis modalities for the treatment of end-stage kidney disease (CADTH Optimal Use Report, Vol.6, No. 2b). Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Dialysis modalities for the treatment of end-stage kidney disease: a health technology assessment—project protocol (CADTH optimal use report; Vol.6, No. 2a). Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hiramatsu T, Okumura S, Asano Y, Mabuchi M, Iguchi D, Furuta S. Quality of life and emotional distress in peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis patients. Ther Apher Dial. 2020;24:366-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Neumann D, Mau W, Wienke A, Girndt M. Peritoneal dialysis is associated with better cognitive function than hemodialysis over a one-year course. Kidney Int. 2018;93(2):430-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jung H-Y, Jeon Y, Park Y, et al. Better quality of life of peritoneal dialysis compared to hemodialysis over a two-year period after dialysis initiation. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):10266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Iyasere O, Brown E, Gordon F, et al. Longitudinal trends in quality of life and physical function in frail older dialysis patients: a comparison of assisted peritoneal dialysis and in-center hemodialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2019;39(2):112-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rocco MV, Lockridge RS, Jr, Beck GJ, et al. The effects of frequent nocturnal home hemodialysis: the Frequent Hemodialysis Network Nocturnal Trial. Kidney Int. 2011;80(10):1080-1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rocco MV, Daugirdas JT, Greene T, et al. Long-term effects of frequent nocturnal hemodialysis on mortality: the Frequent Hemodialysis Network (FHN) Nocturnal Trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(3):459-468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Unruh ML, Larive B, Eggers PW, et al. The effect of frequent hemodialysis on self-reported sleep quality: Frequent Hemodialysis Network Trials. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31(6):984-991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Unruh ML, Larive B, Chertow GM, et al. Effects of 6-times-weekly versus 3-times-weekly hemodialysis on depressive symptoms and self-reported mental health: Frequent Hemo-dialysis Network (FHN) Trials. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(5):748-758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Culleton BF, Walsh M, Klarenbach SW, et al. Effect of frequent nocturnal hemodialysis vs conventional hemodialysis on left ventricular mass and quality of life: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(11):1291-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Manns BJ, Walsh MW, Culleton BF, et al. Nocturnal hemodialysis does not improve overall measures of quality of life compared to conventional hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2009;75(5):542-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wu AW, Fink NE, Marsh-Manzi JVR, et al. Changes in quality of life during hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis treatment: generic and disease specific measures. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(3):743-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Frimat L, Durand P-Y, Loos-Ayav C, et al. Impact of first dialysis modality on outcome of patients contraindicated for kidney transplant. Perit Dial Int. 2006;26(2):231-239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Manns B, Johnson JA, Taub K, Mortis G, Ghali WA, Donaldson C. Quality of life in patients treated with hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis: what are the important determinants? Clin Nephrol. 2003;60(5):341-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. de Abreu MM, Walker DR, Sesso RC, Ferraz MB. Health-related quality of life of patients receiving hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis in Sao Paulo, Brazil: a longitudinal study. Value Heal J Int Soc Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2011;14(5 suppl 1):S119-S121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Harris SAC, Lamping DL, Brown EA, Constantinovici N. Clinical outcomes and quality of life in elderly patients on peritoneal dialysis versus hemodialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2002;22(4):463-470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lockridge RS, Albert J, Anderson H, et al. Nightly home hemodialysis: fifteen months of experience in Lynchburg, Virginia. Home Hemodial Int. 1999;3(1):23-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McPhatter LL, Lockridge RS, Jr, Albert J, et al. Nightly home hemodialysis: improvement in nutrition and quality of life. Adv Ren Replace Ther. 1999;6(4):358-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McFarlane PA, Bayoumi AM, Pierratos A, Redelmeier DA. The quality of life and cost utility of home nocturnal and conventional in-center hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2003;64(3):1004-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heidenheim AP, Muirhead N, Moist L, Lindsay RM. Patient quality of life on quotidian hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(1 suppl):36-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Garg AX, Suri RS, Eggers P, et al. Patients receiving frequent hemodialysis have better health-related quality of life compared to patients receiving conventional hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2017;91(3):746-754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Finkelstein FO, Finkelstein SH, Wuerth D, Shirani S, Troidle L. Effects of home hemodialysis on health-related quality of life measures. Semin Dial. 2007;20(3):265-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chertow GM, Levin NW, Beck GJ, et al. In-center hemodialysis six times per week versus three times per week. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(24):2287-2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Smyth B, van den Broek-Best O, Hong D, et al. Varying association of extended hours dialysis with quality of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(12):1751-1762. https://cjasn.asnjournals.org/content/14/12/1751. Accessed August 26, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jardine MJ, Zuo L, Gray NA, et al. A trial of extending hemodialysis hours and quality of life. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(6):1898-1911. https://jasn.asnjournals.org/content/28/6/1898. Accessed August 26, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Eneanya ND, Maddux DW, Reviriego-Mendoza MM, et al. Longitudinal patterns of health-related quality of life and dialysis modality: a national cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Aiyegbusi OL, Kyte D, Cockwell P, et al. Measurement properties of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) used in adult patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(6):e0179733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bugeja A, Dacouris N, Thomas A, et al. In-center nocturnal hemodialysis: another option in the management of chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(4):778-783. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19339410. Accessed August 26, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Michels WM, van Dijk S, Verduijn M, et al. Quality of life in automated and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int J Int Soc Perit Dial. 2011;31(2):138-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, CADTH_Supplementary_Tables for A Comparison of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures of Quality of Life By Dialysis Modality in the Treatment of Kidney Failure: A Systematic Review by Brandon Budhram, Alison Sinclair, Paul Komenda, Melissa Severn and Manish M. Sood in Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease