Abstract

Background: CT has become the gold standard for radiographic evaluation of urolithiasis. CT is highly sensitive for detecting kidney stones and provides valuable information regarding stone size, composition, location, and overall stone burden. Although CT can provide reliable estimations of stone size, we have encountered an instance in which it can be deceiving. Motion artifact in CT images can cause a warping distortion effect that makes renal stones appear larger than they actually are.

Case Presentation: We describe a case of a 37-year-old woman with a history of kidney stones and obesity presenting with intermittent flank pain and gross hematuria, found to have a large lower pole renal calculus that appeared deceptively large on CT imaging. Given the apparent size and location of the stone, the patient was counseled and consented for a percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL). Although the stone was initially suspected to be >2 cm based on the preoperative CT scan, intraoperative pyelography revealed a much smaller than expected radio-dense stone. The patient was stone free after PCNL without any immediate postoperative complications. However, her course was later complicated by delayed bleeding causing significant clot hematuria, perinephric hematoma, and reactive pleural effusion.

Conclusion: Although CT is especially valuable in preparing for surgery based on its ability to outline collecting system anatomy, it is important to remember that it can be deceiving. Correlation with kidney, ureter, and bladder radiograph and ultrasound is critical to understanding the clinical case and planning the optimal surgical approach.

Keywords: percutaneous nephrolithotomy, urolithiasis, CT imaging

Introduction and Background

CT has become the gold standard for radiographic evaluation of urolithiasis. CT provides valuable information regarding stone size, composition, location, and overall stone burden. Compared with kidney, ureter, and bladder radiograph (KUB), CT more clearly delineates renal anatomy and is, therefore, useful in planning surgical approaches to stone removal. CT is also more sensitive for detecting kidney stones, with sensitivity nearing 100%. Because of respiratory motion that occurs while the patient is in the scanner, the resulting motion artifact in CT images can cause a warping distortion effect that makes renal stones appear larger than they actually are. American Urological Association guidelines state that stones <2 cm are amenable to ureteroscopy, whereas stones >2 cm should be treated with percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL). This is especially true of lower pole stones. In this study, we discuss the management of a large lower pole renal calculus that appeared deceptively large on CT imaging leading to a change in operative approach.

Case Presentation

Clinical history

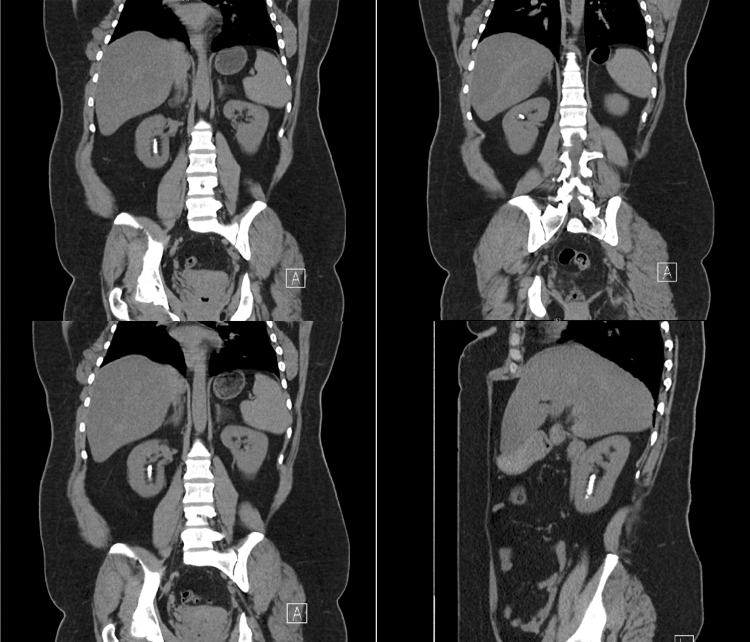

A 37-year-old woman with a medical history notable for kidney stones and obesity initially presented with intermittent right flank pain and gross hematuria. She reported a history of a single episode of kidney stones in 2009, which did not require any intervention. A noncontrast CT scan (Fig. 1) revealed two nonobstructing right renal stones: a 2.57 cm lower pole stone (640 ± 102 HU) and a 9.4 mm mid-caliceal stone. The patient's body mass index was 38.4 and the skin to stone distance measured on CT was 11.5 cm. Based upon the apparent size and location of the stones, she was counseled and consented for a PCNL.

FIG. 1.

CT images demonstrating the warp effect caused by respiratory motion elongating a stone that is actually 6 mm. The official read of this stone was a right partial staghorn calculus measuring 25.7 mm.

Intervention

The patient was taken to the operating room for a prone PCNL on a split leg table following our standard protocol. Retrograde pyelography revealed normal anatomy with a smaller than expected radio-dense lower pole stone along with a mid-caliceal stone. Ultrasound-guided access was performed into the lower pole of the kidney followed by balloon dilation, placement of a 24F access sheath, and fragmentation and extraction of what on nephroscopy was confirmed to be a smaller than expected stone. Antegrade flexible nephroscopy was performed to ensure the patient was stone free. Because of edema at the right ureteropelvic junction, a ureteral stent was placed, and because of bleeding from the tract upon withdrawal of the sheath, a 16F nephrostomy was placed into the lower pole calix. There were no immediate complications and on postoperative day 1, the Foley catheter and nephrostomy tube were removed, the patient voided spontaneously and she was discharged home with analgesics.

Follow-up

On postoperative day 10, the patient presented to the emergency department with flank pain associated with suprapubic pressure and bright red gross hematuria and clots. The patient was afebrile and vital signs were stable. CT showed the patient was stone free but had a perinephric hematoma without active hemorrhage, likely indicating a spontaneous closed pseudoaneurysm. A Foley catheter was placed and the patient was monitored with bed rest and serial complete blood counts. Hemoglobin remained stable and repeat imaging showed that the hematoma was resolving. The patient had a small right pleural effusion on CT, most likely reactive in the setting of the perinephric hematoma. Interventional radiology was consulted but did not believe it was amenable to drainage. On postoperative day 14, the hematuria resolved and she passed a trial of void, and was discharged the next day with the stent in place.

At follow-up visit on postoperative day 24, the patient reported that she was voiding well and complained only of mild discomfort caused by the stent. Cystoscopy was performed with stent removal. On stone analysis, composition was found to be 80% calcium oxalate monohydrate and 20% calcium oxalate dihydrate. Stone culture had no growth. On 24-hour urine study, the patient was found to have hyperoxaluria and low urine volume. She was subsequently randomized into a low oxalate diet per our institutional study protocol and continues to do well without stone recurrence.

Discussion and Literature Review

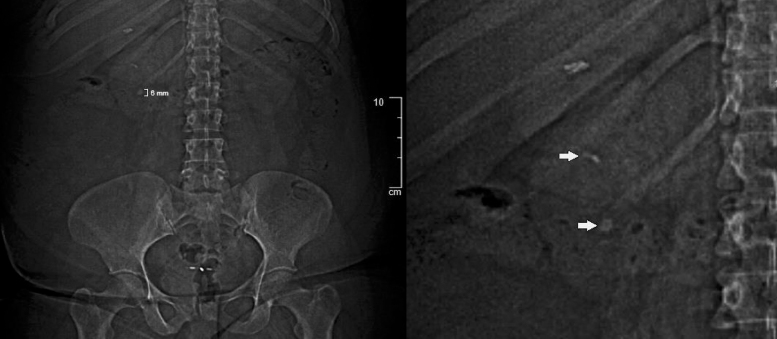

Although the patient was stone free after PCNL, the discrepancy between the intraoperative findings and the preoperative imaging highlights one of the limitations of CT imaging. The patient's lower pole stone was initially suspected to be 25.7 mm based on the reconstructed coronal and sagittal CT images taken preoperatively. The CT, however, had a warping distortion caused by breathing artifact that elongated the size of the stone to this incorrect measurement. It is worth noting that in retrospect, the two stones, although with difficulty, could be seen on the scout film of the CT to actually measure closer to 4 and 6 mm (Fig. 2). Although the immediate postoperative period was uncomplicated, her course was later complicated by delayed bleeding causing significant clot hematuria, perinephric hematoma, and reactive pleural effusion. This case provides an important example of how CT can be deceiving, despite being widely accepted as the gold standard for urolithiasis.

FIG. 2.

Left to right: KUB demonstrating 6.0 mm stone in the lower pole of the right kidney and the same KUB at higher magnification demonstrating the 6.0 mm lower pole stone and additional 4.0 mm stone (indicated by arrows). KUB, kidney, ureter, and bladder radiograph.

Stone diameter can be measured to the nearest millimeter with unenhanced CT in a magnified bone window either transversely in the axial plane or in the coronal plane. However, coronal and sagittal measurements are reconstructions that are subject to respiratory artifact. The measurement of maximum craniocaudal length is, therefore, imperfect and may be over- or underestimated.1 The reliability of determining renal stone size using various imaging modalities has been widely described in the literature. In a study by Tisdale et al.,2 researchers compared transverse and craniocaudal stone measurements of stones <1 cm in diameter using CT and KUB. They found that although the transverse dimension of stones measured by the two imaging modalities were similar, the craniocaudal dimensions differed significantly, with CT measuring 1.4 mm larger on average.

One explanation for the misleading estimations of stone size on CT is the motion that occurs as the patient breaths during image acquisition. Helical scanning of moving organs can lead to distortions of the object's shape. In addition to affecting size measurement, respiratory motion can also make it difficult to differentiate stone composition on CT. Grosjean et al.3 have shown that even slight motion applied to renal stones during CT image acquisition can alter attenuation values. They suggest that a perfect breath-hold must be performed to use dual-energy CT attenuation values to accurately predict the chemical composition of stones. As this case demonstrates, it behooves a urologist to become highly suspect of stones that appear to be linear in the craniocaudal dimension and to carefully compare these with the scout film taken before CT. This respiratory motion artifact may occur in the axial plane as well, and a urologist must have a high degree of suspicion to recognize this artifact preoperatively.

In this case, clinical decision making was heavily guided by the stone size estimated based on CT imaging. Alternative interventions to PCNL for large staghorn calculi include extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (SWL) and ureteroscopic laser lithotripsy (URSLL). For lower pole stones, the Lower Pole Study Group has demonstrated that calculi >1.0 cm have a success rate <50% with SWL.4 URSLL was preoperatively considered a more difficult but viable alternative to PCNL for this patient, but was considered less likely to render her stone free, given the apparent size of her stone and the steep infundibulopelvic angle. Although CT is especially valuable in preparing for surgery based on its ability to outline collecting system anatomy, it is important to remember that it can be deceiving. Urologists should also use other information, such as KUB or ultrasound, and communicate with radiology colleagues to get a better sense of size before planning their approach.

Abbreviations Used

- CT

computed tomography

- SWL

extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy

- HU

Hounsfield units

- KUB

kidney, ureter, and bladder radiograph

- PCNL

percutaneous nephrolithotomy

- URSLL

ureteroscopic laser lithotripsy

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

No funding was received for this article.

Cite this article as: Rosenbluth E, Chandhoke R, Rosen DC, Bamberger JN, Gupta M (2020) Deceived by a CT scan: the case of the misrepresented stone size, Journal of Endourology Case Reports 6:3, 114–117, DOI: 10.1089/cren.2019.0127.

References

- 1. Renard-Penna R, Martin A, Conort P, et al. Kidney stones and imaging: What can your radiologist do for you? World J Urol 2015;33:193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tisdale BE, Siemens DR, Lysack J, Nolan RL, Wilson JW. Correlation of CT scan versus plain radiography for measuring urinary stone dimensions. Can J Urol 2007;14:3489–3492 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grosjean R, Sauer B, Guerra RM, Daudon M, Blum A, Felblinger J, Hubert J. Characterization of human renal stones with MDCT: Advantage of dual energy and limitations due to respiratory motion. Am J Roentgenol 2008;190:720–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Albala DM, Assimos DG, Clayman RV, et al. Lower pole I: A prospective randomized trial of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy and percutaneous nephrostolithotomy for lower pole nephrolithiasis-initial results. J Urol 2001;166:2072–2080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]