Abstract

Background: Situs invesus totalis is a rare congenital anomaly characterized by the mirror-image transposition of abdominal and thoracic organs. Although feasible, operating on patients with situs inversus offers unique technical challenges to the surgeon because of its rarity and the contralateral disposition of the viscera. Urologists in particular need to be aware of the genitourinary abnormalities associated with situs inversus when planning to operate.

Case Presentation: We report the case of a 67-year-old man with invasive bladder cancer in the presence of situs inversus totalis (SIT) and associated bilateral duplicated ureters. This is only the second case of bladder cancer in the context of situs inversus reported in the literature and the first one managed with robot-assisted radical cystectomy and urinary diversion with an intracorporeal ileal conduit.

Conclusion: In this unique case, robot-assisted radical cystectomy with intracorporeal ileal conduit in a patient with muscle-invasive bladder cancer and SIT was safely performed and we suggest to others to consider our technique of “mirror-image port placement and surgical technique” if they encounter such a patient.

Keywords: robotic urinary diversion, intracorporeal ileal conduit, situs inversus, bladder cancer

Introduction and Background

Situs inversus totalis (SIT) has a reported incidence of 1 in 10,000 to 50,000.1 Thus, surgeons rarely encounter a patient with SIT. It is typically incidentally discovered on imaging and is associated with a normal life expectancy.2 There is no known evidence to suggest that situs inversus increases the risk of malignancy.3 Cancers reported in patients with SIT include pancreatic, hepatocellular, colorectal, and gastric cancers.1 From a urologic perspective, several renal cell and urothelial carcinomas have been reported in patients with SIT, but only one case before this has been reported of a patient with muscle-invasive bladder cancer and SIT to date. SIT may pose several technical difficulties during operative procedures, especially during laparoscopic operations because of the mirror image of the laparoscopic view. This requires constant reorientation of anatomy from surgeons, even when carrying out standard maneuvers. We discuss our approach as well as particular considerations that need to be taken into account when performing radical cystectomy with ileal conduit urinary diversion in patients with SIT.

Presentation of Case

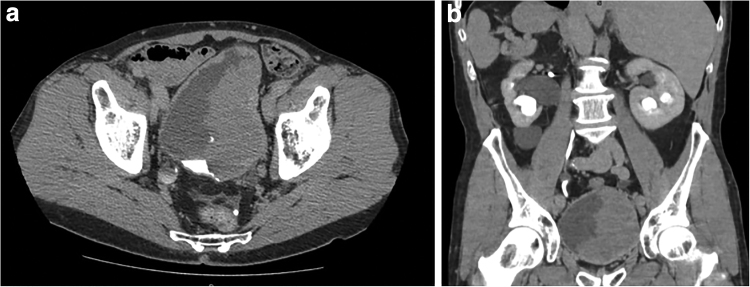

A 67-year-old Caucasian man with SIT and a bilateral duplicated urinary system presented with hematuria. He was identified to have a large bladder tumor on CT imaging (Fig. 1a, b). He was also identified to have bilateral duplicated systems with hydroureteronephrosis in both left renal moieties and the right lower moiety. At this point, the patient did not have any azotemia. The patient was taken to the operating room for an examination under anesthesia (EUA) and a transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT). We were unable to completely resect the tumor given the bulk of disease on TURBT, and EUA revealed a palpable nonfixed mass on bimanual examination. Pathology analysis from TURBT revealed low-grade noninvasive urothelial carcinoma without any variant histology.

FIG. 1.

Preoperative CT showing large bladder wall thickening suspicious for tumor: (a) axial image and (b) coronal image.

Given that the mass was too large to resect endoscopically and that the patient had bilateral duplicated systems with three of four moieties demonstrating hydronephrosis, the surgeon and patient elected to proceed with robot-assisted laparoscopic radical cystoprostatectomy (RALRC), bilateral extended pelvic lymph node dissection, and intracorporeal ileal conduit urinary diversion, and reconstruction of right duplicated ureter.

Intraoperatively, all robotic ports were placed in the mirror image of the standard locations for RALRC because of the patient's situs inversus. Instead of the traditional left-sided placement, the bedside assistant was placed on the right of the bed with a right-sided 12 mm robotic port for robotic stapling. Once pneumoperitoneum was achieved, the cystoprostatectomy and lymphadenectomy portions of the case were completed in an identical manner to patients without situs inversus. Next, the cecum was identified in the left lower quadrant (LLQ), and a 20 cm segment of terminal ileum was harvested 20 cm from the ileocecal junction. This segment was placed posteriorly, and a stapled side-to-side bowel–bowel anastomosis was performed anterior to the harvested ileal conduit segment without incident.

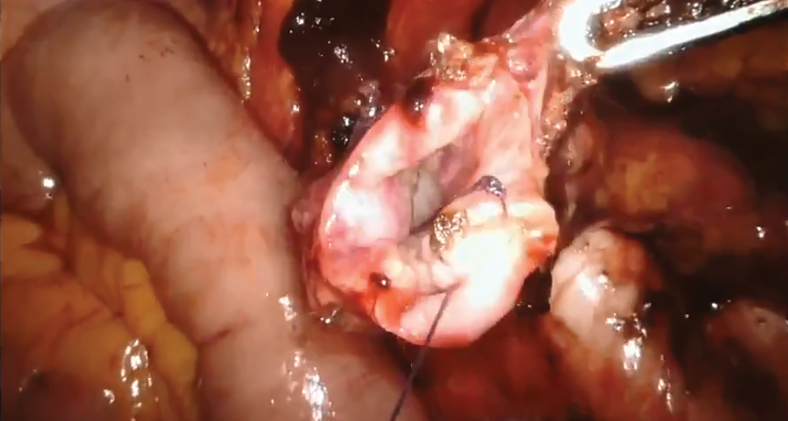

A common sheath ureter on the right side was transposed underneath the sigmoid to the left side. The common wall was spatulated together and oversewn using 4-0 Vicryl suture, similar to a Wallace type of anastomosis (Fig. 2). This was then attached to the butt end of the ileal conduit. The smaller ureter of the complete duplication on the right side was stented. The left ureter was then isolated, and Bricker end-to-side anastomosis onto the proximal end of the conduit was completed. Because the ileum was located on the patient's LLQ, and the desire to provide the patient with an isoperistaltic ileal conduit, the stoma was matured on the left side of the patient's abdominal wall (Fig. 3). The patient's operative and postoperative course were uneventful. His hospital stay was 5 days, stents were removed at 2 weeks and the patient did not have any significant complications. The final pathology analysis revealed high-grade Ta urothelial carcinoma, 12 cm in largest dimension with negative margins and 0 of 15 lymph nodes involved. CT imaging done 3 months post-RALRC revealed resolution of hydronephrosis without evidence of disease (Fig. 4).

FIG. 2.

Wallace type anastomosis of right duplicated ureter.

FIG. 3.

Stoma of ileal conduit on patient's left lower abdomen.

FIG. 4.

Postoperative CT, coronal image.

Discussion and Literature Review

SIT is a congenital anatomic anomaly inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. One suggested mechanism is that immobility of nodal cilia inhibits the flow of extraembryonic fluid during embryogenesis.4 Many laparoscopic procedures have been reported to be performed safely and effectively in patients with SIT despite the presence of technical difficulties because of mirror image of the anatomy.5 In urology, patients with SIT have undergone complete and partial laparoscopic nephrectomies.2,6,7 In 1998, Rodrigues and colleagues described the management of invasive bladder cancer in the presence of SIT by the formation of a urinary diversion after radical cystectomy.8 Their patient also had a complete left ureteral duplication, whereas our patient has bilateral ureteral duplication. Although they performed an open radical cystectomy after abdominal exploration, our patient underwent a robot-assisted laparoscopic radical cystectomy with intracorporeal ileal conduit.

There are several considerations that need to be taken when undergoing a robot-assisted laparoscopic radical cystectomy with urinary diversion in patients with SIT. In addition to having patients undergo a complete cardiopulmonary evaluation, special attention is needed in identifying possible genitourinary anomalies when performing urologic procedures in patients with SIT. Renal anomalies including horseshoe kidney, renal agenesis, hypoplasia, ectopia, polycystic kidneys, and ureteral duplication have been described in patients with SIT.8 Preoperative imaging with CT and CT angiography can be a beneficial preparatory step in surgical planning.

For the operating urologist, patients with SIT offer unique surgical challenges including a greater mental exertion from constantly having to reorient anatomical knowledge and landmarks. Simulation has emerged as a tool that, if appropriately integrated into surgical training, might provide a time-efficient, cost-effective, and safe method of training, particularly in situations with anatomical anomalies such as situs inversus. Makiyama et al. report the first case of preoperative training using a patient-specific laparoscopic simulator for a patient with SIT and right renal pelvic cancer who underwent laparoscopic right nephroureterectomy through a retroperitoneal approach.6 They developed a simulator that utilized the patient's CT data to reproduce the retroperitoneal space. This operating surgeon trained with this simulator to increase familiarity with the patient's SIT anatomy. Utilization of such simulators in the setting of patients with SIT may be of benefit in reducing risk for potential error by less experienced urologists or residents in training.

As previously mentioned, our patient had bilateral ureteral duplication, which needed to be accounted for during ureteral reconstruction and attachment to the ileal conduit. In addition, mesenteric abnormalities such as short mesentery with an abnormal vascular supply have been described in the literature. For these patients, orthotopic neobladder urinary diversion may not be feasible.8

Typically, the left ureter is transposed and brought under the sigmoid colon in ileal conduit urinary diversions with right-sided stomas. In our patient with SIT, we transposed the right ureter, and the ileal conduit was planned such that the stoma was formed on the left side of the patient. If we had maintained the ileal conduit on the same side as non-SIT patients, counter-peristalsis could potentially contribute to longer urinary transit times and worsening renal function. Hence, to maintain an isoperistaltic orientation, a left ileal conduit stoma location was selected and created.

Postoperative considerations include communication with appropriate follow-up care personnel to inform them of the atypical location of the stoma because of the inverted location of the cecum and terminal ileum in the LLQ. Another consideration related to the day-to-day management of the stoma is that most patients, including ours, are right-handed, and the typical location is in the right lower quadrant. This allows for the easier handling and care of the stoma. However, patients with situs inversus who have an LLQ stoma but are right-handed may have difficulty in handling the stoma with their nondominant hand and may need additional training.

Conclusion

Although the incidence of intra-abdominal urologic malignancies in a patient with SIT is rare, the surgeon must anticipate the complexity of the surgical procedure in cancer patients with SIT. Advanced surgical skill is required to perform a precise radical cystectomy with lymphadenectomy and intracorporeal ileal conduit urinary diversion in a patient with SIT by observing the exact mirror image of the anatomy throughout the entirety of the operation. Preoperative recognition of the anatomic variations might be needed when operating on a patient with SIT, and also three-dimensional CT angiography reconstruction and training with a surgical simulator before the operation can augment the surgeon's preparedness for operating. In conclusion, robot-assisted radical cystectomy with intracorporeal ileal conduit in our patient with muscle-invasive bladder cancer and SIT was safely performed and we suggest to others to consider our technique of “mirror-image port placement and surgical technique” in the event such a patient is encountered.

Abbreviations Used

- CT

computed tomography

- EUA

examination under anesthesia

- LLQ

left lower quadrant

- RALRC

robot-assisted laparoscopic radical cystoprostatectomy

- SIT

situs inversus totalis

- TURBT

transurethral resection of bladder tumor

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

No funding was received for this article.

Cite this article as: Munshi FI, Polotti CF, Elsamra SE (2020) Robot-assisted radical cystectomy with intracorporeal ileal conduit in a patient with situs inversus totalis, Journal of Endourology Case Reports 6:3, 135–138, DOI: 10.1089/cren.2019.0137.

References

- 1. Suh BJ. A case of gastric cancer with situs inversus totalis. Case Rep Oncol 2017;10:130–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gokcen K, Celik H, Kobaner M, Karazindiyanoglu S. Laparoscopic transperitoneoscopic nephroureterectomy in a patient with situs inversus totalis. Indian J Surg 2015;77:147–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oake J, Drachenberg D. A case of renal cell carcinoma in a patient with situs inversus: Operative considerations and a review of the literature. Can Urol Assoc J 2017;11:E233–E236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nonaka S, Tanaka Y, Okada Y, et al. Randomization of left-right asymmetry due to loss of nodal cilia generating leftward flow of extraembryonic fluid in mice lacking KIF3B motor protein. Cell 1998;95:829–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fujiwara Y, Fukunaga Y, Higashino M, et al. Laparoscopic hemicolectomy in a patient with situs inversus totalis. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:5035–5037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Makiyama K, Sakata R, Yamanaka H, Tatenuma T, Sano F, Kubota Y. Laparoscopic nephroureterectomy in renal pelvic urothelial carcinoma with situs inversus totalis: Preoperative training using a patient-specific simulator. Urology 2012;80:1375–1378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang LH, Liu B, Wu Z, et al. Left transperitoneal laparoscopic partial nephrectomy in the presence of a left-sided inferior vena cava. Urology 2011;78:469–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rodrigues GP, Gheiler EL, Tefilli MV, Da Silva EA, Tiguert R, Pontes JE. Urinary diversion following cystectomy in a patient with situs inversus totalis. Urol Int 1999;62:55–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]