Abstract

Despite their ubiquity in academic and commercial research, evidence of the usefulness of consumer confidence indices is mixed. To contribute to this debate, we examine the psychological mechanisms through which consumer confidence does (and does not) affect consumer behavior. We develop a conceptual model, which we test via structural equation modelling and moderated mediation analysis, using data from a sample of US consumers (n = 1,090). Rather than conceptualize consumer confidence as a single construct, our study is the first to distinguish between national consumer confidence and personal consumer confidence. Consistent with cognitive appraisal theory, personal consumer confidence mediates the relationship between national consumer confidence and perceived financial vulnerability, which in turn leads to increased price conscious behavior. Drawing on attribution theory, we find that external locus of control enhances the effects of national consumer confidence. We provide practical advice to economic forecasters, business analysts, marketers, and financial educators.

Keywords: Consumer confidence, Financial vulnerability, Price conscious behavior, Locus of control, Attribution theory, Cognitive appraisal theory

1. Introduction

“Consumer confidence survey casts doubt on V-shaped recovery”

Amidst historically challenging economic conditions, markers of consumer financial vulnerability have heightened in 2020, notably unemployment (Financial Times, 2020), bad debts (The Times, 2020), and money-related stress (Colombia University Irving Medical Centre, 2020). Against this backdrop, there has been a significant rise in price conscious behavior (Deloitte, 2020). In the second quarter of 2020, household spending declined by 34.6% (Reuters, 2020) and the personal savings rate reached 32.2%, having been consistently below 10.0% since 2010 (Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2020). At the individual level, stricter financial management is prudent; from a macroeconomic perspective, its current magnitude is worrying given that consumer spending will be a key driver of economic recovery. As economists and business leaders look for the first offshoots of growth, increased attention has been paid to monthly consumer confidence surveys, which measure households’ subjective evaluations of the broad national economy and their personal finances (Ou, de Vries, Wiesel, & Verhoef 2014, p. 339). Headlines such as that above are commonplace in the current news cycle, reflecting a widely held belief that consumer confidence data help forecast consumer spending. But how confident should we be in consumer confidence indices?

Academic literature provides equivocal evidence (Table 1 ). Several researchers have demonstrated that consumer confidence explains changes in household expenditures (Benhabib and Spiegel, 2019, Dees and Brinca, 2013, Dragouni et al., 2016, Singal, 2012) as well as customer satisfaction (Ou et al., 2014), customer loyalty (Hunneman, Verhoef, & Sloot, 2015), and consumer ethnocentrism (Hampson, Ma, & Wang, 2018). However, the efficacy of consumer confidence data is not universally accepted. In a recent piece for the World Economic Forum, Alexander and Cuddy (2018) call consumer confidence, initiated by the University of Michigan in 1967, “a child of its time” that no longer serves a useful purpose. Their opinions have some support from the academic community, with several studies failing to find evidence of the predictive validity of consumer confidence (Cotsomitis and Kwan, 2006, Fan and Wong, 1998). In a seminal paper, Ludvigson (2004, p. 29) concludes that “the information provided by consumer confidence predicts a relatively modest amount of additional variation in future consumer spending”.

Table 1.

Summary of selected consumer confidence literature.

| Study | Context |

Model summary |

Major finding(s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variable | Mediator(s) | Dependent variable(s) | Moderator variable(s) | |||

| Benhabib & Spiegel (2019) | USA (2005 –2016) | Consumer confidence | – | PCE | – | Positive empirical relationship between CC and future economic activity as well as future consumption expenditures. |

| Hampson et al. (2018) | Brazil | Financial well-being | Ethnocentrism, value of global brands, norms | Domestic brand consumption | Consumer confidence | CC attenuates the indirect effects of reduced financial well-being on domestic brand consumption via consumer ethnocentrism and perceived value of global brands. |

| Dragouni et al. (2016) | USA (1996–2013) | Consumer confidence | – | Outbound tourism demand | – | There is a moderate to high interrelationship among consumer confidence and outbound tourism demand |

| Hunneman et al. (2015) | Netherlands(2009–2013) | Store attributes | Store satisfaction | Share of wallet | Consumer confidence | CC negatively affects the relationship between service evaluations and satisfaction. Contrary to hypotheses, CC does not moderate the effects of price or convenience on satisfaction. |

| Ou et al. (2014) | Netherlands | Customer equity drivers | – | Loyalty intentions (services) | Consumer confidence | The positive effects of value equity and brand equity on loyalty intentions is stronger for low (vs. high) CC customers. CC does not moderate the effects of relationship equity. |

| Dees & Brinca (2013) | USA & Eurozone (1985–2010) | Consumer confidence | – | PCE | – | CC is a good predictor of consumption, especially following large changes in CC. Evidence of ‘confidence channel’: changes in other countries predict CC in the euro area. |

| Singal (2012) | USA (1980–2009) | Consumer confidence | – | Hospitality expenditure/stock returns | – | Hospitality industry stock returns are correlated with changes in CC.CC predicts changes in consumer hospitality expenditures. |

| Cotsomitis & Kwan (2006) | 9 EU countries (1987–2002) | Consumer confidence | – | PCE | – | Overall, CC has limited ability to predict changes in household expenditure, although there is some variability across nations |

| Ludvigson (2004) | USA (1968–2002) | Consumer confidence | Expenditure on services, (non)durables | – | The independent information provided by CC predicts a relatively modest amount of additional variation in future consumer spending. | |

| Fan & Wong (1998) | Hong Kong (1985–1996) | Consumer confidence | – | PCE | – | Consumer confidence is unable to predict spending growth in durables, non-durables or services |

| Our study | USA | National consumer confidence | Personal consumer confidence | Financial vulnerability; price consciousness | Locus of control | There are distinct types of CC: personal CC mediates the relationship between national CC and perceived financial vulnerability. LOC moderates the influence of national CC |

Notes: PCE = personal consumption expenditure; CC = consumer confidence; LOC = locus of control.

Against this backdrop, the broad objective of our paper was to attempt to reconcile these differing perspectives on consumer confidence. Three observations about existing consumer confidence research shaped the direction of our study. The first was conceptual. Consumer confidence is typically conceptualized as a singular construct, operationalized as the average of answers to questions about respondents’ perceptions of the national economy broadly and their personal finances specifically (e.g., Hampson et al., 2018, Hunneman et al., 2015, Ou et al., 2014). Yet the implicit assumption that evaluations of the national economy and personal finances are the same thing is potentially flawed. To illustrate, in Fig. 1 we disaggregate UK consumer confidence (2000–2020) into two sub-indices (i.e., national consumer confidence and personal consumer confidence). During this period, personal consumer confidence tended to be higher and less volatile than national consumer confidence. Further, confidence in personal finances was less susceptible to the three major shocks during this timeframe (i.e., the 2008/09 recession, the 2016 Brexit vote, and Covid-19 in 2020). This indicates that there are distinct types of consumer confidence. A central tenet of our paper is that this conceptual distinction is crucial in understanding the mechanisms through which perceptions of the national economy ultimately lead to behavioral changes.

Fig. 1.

UK consumer confidence January 2004 -June 2020. Source:European Commission (2020). *Brexit period is from the initial vote to leave (June 2016) to the official withdrawal from the EU (January 2020). Notes: Personal consumer confidence calculated as the average of two questions (“How has the financial situation of your household changed over the last 12 months?” and “How do you expect the financial position of your household to change over the next 12 months?”); National consumer confidence calculated as the average of two questions (“How do you think the general economic situation in this country has changed over the past 12 months?” and “ How do you expect the general economic situation in this country to develop over the next 12 months?”; values about zero indicate confidence, values below zero indicate pessimism.

Second, as shown in Table 1, extant studies have not examined factors that mediate the relationship between consumer confidence and consumer spending. This gap is important because understanding the sequence of cognitive and affective responses to changes in consumer confidence might better help explain the nature of its relationship with behavioral adjustments and identify specific avenues for practitioner intervention. We make a first effort to resolve this research gap by exploring the mediating role of financial vulnerability, defined as the likelihood that an individual will experience financial hardship (i.e., a state of distress in which an individual is unable to maintain their standard of living) (O’Connor et al., 2019, p. 422). Given its various social and economic consequences, including low emotional and material well-being (Treanor, 2016) and long-term money management problems (He, Derfler-Rozin, & Pitesa, 2020), financial vulnerability is of practical interest to policymakers, healthcare providers, and businesses. Our work is timely given the prevailing gloomy economic forecasts and recent calls for research that examines how such conditions affect individuals’ experiences of financial vulnerability (O’Connor et al., 2019).

The third issue relates to unit of analysis. None of the studies in Table 1 examined the heterogeneity of the effects of consumer confidence between different consumer segments. Instead, analyses have been conducted at an aggregate level, which potentially masks the efficacy of consumer confidence indices for certain types of consumers, while overplaying their importance for others. In an initial attempt to address this research gap, we focus on locus of control, an individual difference construct that reflects individuals' beliefs about the degree to which they can control the outcomes of events in their lives (Galvin et al., 2018, Rotter, 1954). Prior research demonstrates that locus of control moderates the effects of external stimuli on affective and behavioral responses (e.g., Jiang et al., 2020). Moreover, interventions targeting locus of control can be beneficial to individuals’ well-being (Li, Lepp, & Barkley, 2015). Therefore, locus of control offers promise in the context of understanding and managing consumer financial vulnerability.

Given the above, we set out to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: Are national consumer confidence and personal consumer confidence separate constructs?

RQ2: What mechanisms explain the relationships between consumer confidence, perceived financial vulnerability, and price conscious behavior?

RQ3: Does locus of control moderate the effects of consumer confidence on perceived financial vulnerability?

To answer these questions, we develop a conceptual model, which we test via structural equation modelling and moderated mediation analyses, using data collected from an online survey of U.S. consumers (n = 1,090). In so doing, we make three contributions to consumer confidence literature. The first contribution is conceptual. Ours is the first study to distinguish between national consumer confidence and personal consumer confidence and build a conceptual model examining their relationship and effects. Second, we identify the psychological mechanisms through which the two types of consumer confidence influence price conscious behavior. Consistent with cognitive appraisal theory, results demonstrate that a) personal consumer confidence fully mediates the relationship between national consumer confidence and perceived financial vulnerability, and b) perceived financial vulnerability mediates the relationship between personal consumer confidence and price conscious behavior. Third, drawing on attribution theory, we show that locus of control moderates the relationship between national consumer confidence and perceived financial vulnerability. For individuals high (vs. low) in external locus of control, national consumer confidence has a larger direct and indirect effect. We also make contributions to the financial vulnerability literature. Prior studies have revealed several antecedents, including cognitive ability and personality traits (e.g., Xu, Briley, Brown, & Roberts, 2017), compulsive and impulsive buying (Abrantes-Braga & Veludo-de-Oliveira, 2020), and social and institutional marginalization (Faber, 2019). Ours is the first to examine the mechanisms of consumer confidence and locus of control in the development of financial vulnerability, providing fresh insight into how policymakers and businesses might anticipate and minimize the extent of financial vulnerability.

2. Hypotheses development

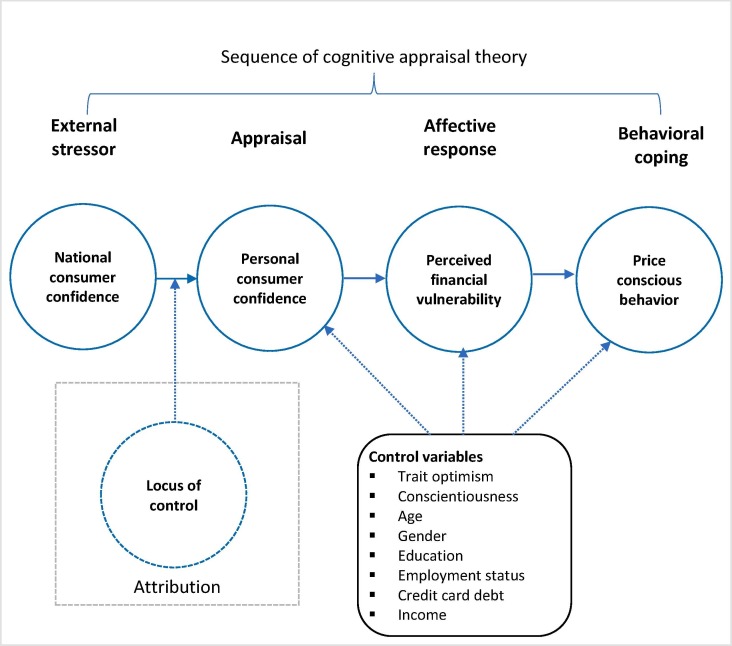

Our model is informed by two theories that are well established in the consumer literature. Cognitive appraisal theory is used to predict an indirect relationship between consumer confidence and price conscious behavior via perceived financial vulnerability. Attribution theory is used to identify locus of control as a boundary condition. We introduce each of these theories before formalizing the hypotheses in our model, which is displayed in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

Research model.

2.1. Theoretical foundations

Cognitive appraisal theory offers insight into the mechanisms through which stressors impact individuals’ emotions and behavior, where a stressor is defined as an internal or external stimulus that has the potential to bring a significant change in a person’s life (Moschis, 2007). According to cognitive appraisal theory, an individual's reaction to a stressor follows an appraisal-emotion-behavior sequence (Folkman & Lazarus, 1984). Individuals evaluate how and to what extent a stressor will affect them; this appraisal then evokes an emotional response that, depending on its magnitude, might require behavioral adaptations (Folkman & Lazarus, 1984).

Alone, cognitive appraisal theory does not explicate when an individual will (or will not) appraise a stressor as significant to their well-being. To address this limitation, we draw on attribution theory, a central tenet of which is that individuals have a need to identify the causal agents of significant aspects of their lives because doing so serves to defend or enhance self-esteem, public identity, and/or positive emotions (Shepperd, Malone, & Sweeny, 2008). Within attribution theory research, locus of control has emerged as an important moderator of individuals’ affective and behavioral responses to stressors (e.g., Debus et al., 2014, Jiang et al., 2020, Reknes et al., 2019). Consistent with these studies, our model incorporates locus of control as a moderator of the relationship between consumer confidence and perceived financial vulnerability.

2.2. National and personal consumer confidence

Consumer confidence is defined as “a psychological construct that measures customers’ perceptions about their recent and future financial situation and economic climate” (Ou et al., 2014, p. 339). Though this definition implicitly distinguishes between individuals’ personal finances and the national economy, consumer confidence is universally treated as singular construct, both conceptually and operationally (e.g., Hampson et al., 2018, Hunneman et al., 2015, Ou et al., 2014). In contrast, we propose a distinction between two types of consumer confidence. Drawing on the language of Ou et al. (2014), we define national consumer confidence (hereafter, NCC) as an individual’s perception about the recent and future macroeconomic climate. We define personal consumer confidence (hereafter, PCC) as an individual’s perception about changes in their recent and future personal financial situation.

Consistent with cognitive appraisal theory, we conceptualize NCC as an external stressor and we treat PCC as a cognitive evaluation of the self-relevance of NCC. In so doing, we treat PCC as the mediating mechanism between NCC and financial vulnerability.

2.3. Perceived financial vulnerability

Perceived financial vulnerability refers to individuals’ subjective feelings (e.g., of distress, fear, worry, and concern) about being susceptible to financial hardship (He et al., 2020, O'Connor et al., 2019). Typically, financially vulnerable consumers experience “month-to-month fragility” (Salisbury & Zhao, 2019, p. 8), reflected in struggles to meet even the most essential of expenses, including paying rent/mortgage, groceries, utilities and bills, and repaying debts (Anderloni et al., 2012, Brüggen et al., 2017).

Brüggen et al. (2017) identify individuals’ evaluation of economic indicators such as the unemployment and economic growth rates, captured in our study by NCC, as direct predictors of their perceived financial well-being. We reason that PCC represents a mediating mechanism of this relationship, reflecting the various ways in which macroeconomic factors (captured by NCC) can influence household finances (captured by PCC) and how PCC determines levels of vulnerability. Gloomy economic conditions affect labor markets via heightened unemployment and job insecurity, threatening the primary income source for many individuals (Lowe, 2018). Real wages are pro-cyclical, meaning that during economic contractions, even those employees that keep their jobs have less purchasing power than before (Elsby, Shin, & Solon, 2016). Likewise, during economic downswings, retirees’ pension resources become less secure (Argento, Bryant, & Sabelhaus, 2015). Even if people retain some sense of financial security, the fact that other people are struggling financially might hurt them indirectly, for example via stagnant property values and unstable pension schemes (Munnell & Rutledge, 2013). A nation’s economic health influences the relative strength of its currency, an important consideration for individuals who vacation or invest overseas. In turn, we expect PCC to be negatively associated with perceived financial vulnerability. Low PCC entails expected declines in people’s financial resources. As resources become scarcer, the opportunity to invest and/or build precautionary levels becomes compromised (Halbesleben, Neveu, Paustian-Underdahl, & Westman, 2014). Instead, many households might have to (or anticipate having to) use existing precautionary savings in order to maintain a certain standard of living (Bayer, Lütticke, Pham‐Dao, & Tjaden, 2019). Consequently, their ability to buffer unexpected financial shocks diminishes, leaving them more financially vulnerable.

In sum, we reason that NCC affects perceived financial vulnerability by influencing consumers’ optimism (or pessimism) in their present and near-term personal financial prospects (i.e., PCC). Therefore,

H1: The negative relationship between national consumer confidence and perceived financial vulnerability is mediated by personal consumer confidence.

2.4. Price conscious behavior

Price conscious behavior is defined as the extent to which consumers focus exclusively on low prices when making purchase decisions (Lichtenstein, Ridgway, & Netemeyer, 1993) and is associated with buying private label brands (Sinha & Batra, 1999) and low levels of brand and store loyalty (Koschate-Fischer, Hoyer, Stokburger-Sauer, & Engling, 2018). Because they derive utilitarian and hedonic value from saving money, price conscious shoppers are highly involved in the search, acquisition, and processing of price information (Farías, 2019).

Previous research suggests that positive evaluations of one’s personal financial situation (captured in our study by PCC) is negatively related to price consciousness; when consumers have more financial resources at their disposal, their decisions are not constrained exclusively by price considerations (Koschate-Fischer et al., 2018). We propose that perceived financial vulnerability plays a mediating role in the relationship between PCC and price conscious behavior. Prior research has shown that price conscious behavior is an adaptive response for people experiencing money-related negative affect. For example, in the context of the Great Recession of the late 2000s, price consciousness emerged as a principle coping strategy through which UK consumers sought to mitigate heightened feelings of financial fear and guilt (Hampson & McGoldrick, 2017). Perceived financial vulnerability associates with a range of sub-optimal outcomes, including material deprivation, reduced vitality of social relationships, and physical and mental health problems (O’Loughlin et al., 2017). As such, negative affect such as the feelings of distress associated with financial vulnerability can be psychologically uncomfortable, often devastating. Price conscious behavior is an adaptive behavioral coping strategy because it enables consumers to better conserve financial resources and reduce financial outlays, thus mitigating (at least to some extent) the consequences of lowered PCC (Hampson & McGoldrick, 2017). Therefore, we hypothesize:

H2: The relationship between personal consumer confidence and price conscious behavior is mediated by perceived financial vulnerability.

2.5. The moderating role of locus of control

People with an internal locus of control, ‘internals’, believe that positive outcomes are earned and deserved based upon effort and skill (Twenge, Zhang, & Im, 2004). In contrast, those with an external locus of control, ‘externals’, believe that self-relevant outcomes are beyond their personal control (Rotter, 1954). Scholars have distinguished between two types of external locus of control: chance control, whereby events are due to unordered agents (e.g., luck, fate, and chance); and, control by powerful others, whereby individuals feel that self-relevant events or states are the result of interventions by ordered agents (Fong et al., 2017, Levenson, 1981).

Evidence points to a stronger influence of stressors on the emotional well-being of externals relative to internals. In business contexts specifically, external locus of control has been found to positively enhance the effects of exposure to bullying on employee psychological strain (Reknes et al., 2019) and of contract-type on feelings of job insecurity (Debus et al., 2014). Externals are especially susceptible to the self-serving bias, the tendency to blame external factors when things go wrong (Campbell and Sedikides, 1999). Instead of accepting blame for undesirable states such as vulnerability, externals are more likely to consider themselves as victims (Ng, Sorensen, & Eby, 2006). For externals, this “victim mentality” is self-protective because attributing negative events to outside forces frees themselves from blame and associated feelings of guilt, shame, and regret (Twenge et al., 2004, p. 310). However, this self-serving bias might prevent externals from avoiding the negative consequences of stressors. Relative to internals, externals are more passive in trying to engineer positive outcomes because their perceived victimhood leads them to believe that they cannot cope (Ng et al., 2006). Applied to our research context, we expect that consumers with a high external locus of control (vs. those with a low level) experience higher levels of financial vulnerability when NCC is low because they lack the belief that they can respond proactively in order to mitigate the effects of low NCC. Thus, we hypothesize:

H3a: External locus of control (chance control) moderates the indirect relationship between national consumer confidence and perceived financial vulnerability via personal consumer confidence. The indirect effect is stronger at high (vs. low) levels of chance control.

H3b: External locus of control (control by powerful others) moderates the indirect relationship between national consumer confidence and perceived financial vulnerability via personal consumer confidence. The indirect effect is stronger at high (vs. low) levels of external control by powerful others.

3. Method

3.1. Participants

A questionnaire was distributed online among U.S. consumers using Qualtrics and participants received $5 compensation. We employed quota sampling to ensure that data came from a wide range of ages (no less than 10% in each age category) and both genders (approximately 50% female). We initially received 1,150 responses but deleted 60 cases (5.2%) based on concerns over data quality (see Section 3.2). The final sample (n = 1,090) is 52.1% female and is comprised of respondents from the following age categories: 18–24 (10.2%), 25–34 (15.9%), 35–44 (16.2%), 45–54 (20.3%), 55–64 (17.6%), and 65–75 (19.8%).

3.2. Measures and control variables

We used existing scales to measure the constructs in our model. Four items each measured NCC and PPC (Hampson et al., 2018, Ou et al., 2014) on a nine-point scale (1 = “much worse”, 5 = “no change”, 9 = “much better”). Perceived financial vulnerability was measured with four items adapted from the scale of Anderloni et al. (2012). We measured price conscious behavior with four items from Lichtenstein et al. (1993). We used the original scale of Levenson (1981) to measure the two types of external locus of control, namely ‘chance control’ (three items) and ‘control by powerful others’ (three items). The perceived financial vulnerability, price conscious behaviour, and locus of control items were measured on 7-point scales (1 = “strongly disagree”, 7 = “strongly agree”).

We incorporated eight control variables, covering relevant aspects of personality, demographics, socio-economic status, and financial behavior. To isolate the specific effects of NCC and PCC, which are considered domain-specific measures of optimism (Hampson et al., 2018), we measured trait optimism, a personality trait that measures individual differences in “the extent to which people hold generalized favorable expectancies for their future” (Carver, Scheier, & Segerstrom, 2010, p. 879), with three items from Scheier, Carver, and Bridges (1994). Conscientiousness is a personality trait that describes “impulse control that facilitates task- and goal-directed behavior” (Benet-Martínez & John, 1998, p. 730). Given that “highly conscientious individuals manage their money more because they have positive financial attitudes” (Donnelly, Iyer, & Howell, 2012, p. 1129), we expected conscientiousness to be positively related to PCC and price conscious behavior but negatively associated with perceived financial vulnerability. We measured conscientiousness with four items from Benet-Martínez and John (1998).

Further, we expected gender (0 = male, 1 = female) and employment status (0 = not unemployed, 1 = unemployed) to negatively relate to PCC and positively relate to perceived financial vulnerability and price conscious behavior; the opposite effects were predicted for age, income, and education (0 = no college degree, 1 = college degree) (Netemeyer, Warmath, Fernandes, & Lynch, 2018). Finally, we included a single-item measure of individual’s current level of credit card debt, expecting a negative effect on PCC and a positive effect on perceived financial vulnerability and price conscious behavior (Anderloni et al., 2012).

All multi-item scales are presented in Table 2 along with their factor loadings, construct reliability, and average variance extracted information. Descriptive statistics, inter-construct correlations, and square root of average variance extracted are provided in Table 3 .

Table 2.

Items, loadings, average variance extracted, and scale reliabilities.

| λ | AVE | C.R | |

|---|---|---|---|

| National consumer confidence(1 = “much worse”, 5 = “no change”, 9 = “much better”) | |||

| NCC1: What is your view of the economic situation in the US over the last 12 months? | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.94 |

| NCC2: What is your view of the employment situation in the US over the last 12 months? | 0.84 | ||

| NCC3: What is your expectation of the economic situation in the US in 12 months’ time? | 0.95 | ||

| NCC4: What is your expectation of the employment situation in the US in 12 months’ time? | 0.93 | ||

| Personal consumer confidence(1 = “much worse”, 5 = “no change”, 9 = “much better”) | |||

| PCC1: Compared with 12 months ago, how would you describe your present household financial situation? | 0.85 | 0.60 | 0.88 |

| PCC2: Compared with 12 months ago, how would you describe your present household employment situation? | 0.77 | ||

| PCC3: What are your expectations of your household financial situation in 12 months’ time? | 0.77 | ||

| PCC4: What is your expectation of your employment situation in 12 months’ time? | 0.82 | ||

| Perceived financial vulnerability(1 = strongly disagree”, 7 = “strongly agree”) | |||

| PFV1: My household’s monthly income currently prevents us from making ends meet | 0.84 | 0.74 | 0.93 |

| PFV2 I fear that household would struggle to pay an unexpected expense of $500 today | 0.92 | ||

| PFV3: I’m concerned about my household’s ability to pay for basic expenses (e.g., food, rent, utilities) | 0.94 | ||

| PFV4: Thinking about my household’s finances is stressful for me | 0.68 | ||

| Price conscious behavior(1 = strongly disagree”, 7 = “strongly agree”) | |||

| PC1: I go to extra effort to find lower prices | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.94 |

| PC2: I shop at more than one store to take advantage of low prices | 0.93 | ||

| PC3: The money saved by finding low prices is worth the time and effort | 0.95 | ||

| PC4: I compare prices of at least a few brands before I choose one | 0.85 | ||

| External locus of control - Chance control(1 = strongly disagree”, 7 = “strongly agree”) | |||

| ELOCL1: To a great extent, my life is controlled by accidental happenings | 0.81 | 0.55 | 0.78 |

| ELOCL2: Often there is no change of protecting my personal interest from bad luck happening | 0.70 | ||

| ELOCL3: When I get what I want, it's usually because I'm lucky | 0.71 | ||

| External locus of control - Control by powerful others(1 = strongly disagree”, 7 = “strongly agree”) | |||

| ELOCO1: People like myself have very little chance of protecting our personal interests where they conflict with those of strong pressure groups | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.90 |

| ELOCO2: My life is chiefly controlled by powerful others | 0.93 | ||

| ELOCO3: I feel like what happens in my life is mostly determined by powerful people | 0.91 | ||

| Trait optimism(1 = strongly disagree”, 7 = “strongly agree”) | |||

| TO1: I’m always optimistic about my future | 0.77 | ||

| TO2: In uncertain times, I usually expect the best | 0.89 | 0.67 | 0.76 |

| TO3: Overall, I expect more good things to happen to me than bad | 0.80 | ||

| ConscientiousnessI see myself as someone who… (1 = strongly disagree”, 7 = “strongly agree”) | |||

| C1: Does a thorough job | 0.84 | ||

| C2: Tends to be well organized | 0.83 | 0.67 | 0.89 |

| C3: Makes plans and follows through with them | 0.87 | ||

| C4: Does things efficiently | 0.72 | ||

Notes: λ = standardized factor loadings; AVE = average variance extracted; C.R. = construct reliability.

Table 3.

Means, standard deviations, square root of AVE, and correlations.

| Mean | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. National consumer confidence | 4.72 | 2.05 | 0.90 | ||||||||||||

| 2. Personal consumer confidence | 5.64 | 1.50 | 0.54** | 0.77 | |||||||||||

| 3. Perceived financial vulnerability | 3.85 | 2.15 | −0.26** | −0.41** | 0.86 | ||||||||||

| 4. Price conscious behavior | 4.23 | 1.63 | −0.16** | −0.20** | 0.37** | 0.89 | |||||||||

| 5. ELOC – Chance control | 3.50 | 1.40 | −0.13** | 0.05 | 0.21** | 0.39** | 0.74 | ||||||||

| 6. ELOC – Control by powerful others | 3.20 | 1.60 | 0.07* | 0.02 | 0.13** | 0.34** | 0.73** | 0.86 | |||||||

| 7. Trait optimism | 5.10 | 1.27 | 0.34** | 0.41** | −0.40** | −0.15** | −0.15** | −0.15** | 0.82 | ||||||

| 8. Conscientiousness | 5.53 | 1.20 | 0.05 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.18** | 0.10* | 0.08* | 0.25** | 0.82 | |||||

| 9. Age | 47.70 | 15.96 | −0.17** | −0.25** | −0.18** | −0.12** | −0.31** | −0.18** | 0.02 | −0.09** | – | ||||

| 10. Gender | 0.52 | 0.50 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.13** | 0.08** | 0.06 | −0.06* | 0.00 | 0.06* | 0.24** | – | |||

| 11. Education | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.12** | 0.07* | −0.18** | −0.09** | 0.02 | 0.06* | 0.01 | −0.07* | 0.06* | 0.06* | – | ||

| 12. Employment status | 0.11 | 0.31 | −0.02 | −0.10** | 0.27** | 0.09** | 0.10** | 0.01 | −0.11** | 0.03 | −0.14** | 0.09** | −0.15** | – | |

| 13. Credit card debt | $2,199 | $4,555 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.06* | 0.13** | 0.10** | 0.13** | −0.02 | −0.06* | 0.07* | −0.02 | 0.06* | −0.02 | – |

| 14. Income | $58,674 | $38,421 | 0.10** | 0.11** | −0.25** | −0.19** | −0.04 | −0.02 | 0.11** | −0.08* | 0.06* | −0.09** | 0.26** | −0.12** | 0.07* |

Notes: Square root of average variance extracted on the diagonal; inter-construct correlations below diagonal; * p < .05, ** p < .001; ELOC = external locus of control.

3.3. Common method variance (CMV)

Ex ante, we incorporated multiple measures to minimize CMV, including attention filter questions and alternative response formats (e.g., text entry questions unrelated to study constructs) (Podsakoff, Mackenzie, & Podsakoff, 2012). Ex post, we used the marker variable method to statistically test for CMV. We used the following question, theoretically unrelated to our study variables, as the marker variable: “Do you disagree or agree with the statement that there is too much sport on TV?” (1 = “strongly disagree”, 7 = “strongly agree”). The smallest correlation between the marker variable and other model variables was with PCC (r = 0.02). The remaining correlations remain similar in strength and significance after partialling out the smallest correlation, showing that CMV was not a threat (Lindell & Whitney, 2001).

3.4. Validity assessment

Confirmatory factor analysis (AMOS 22) demonstrated adequate fit: Ratio of chi-square to degrees of freedom (χ2/d.f. = 3.11); NFI = 0.94; CFI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.04; SRMR = 0.04). Table 2 shows that all measures exhibit adequate internal validity: composite reliability for each scale exceeds 0.70 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Average variance extracted for each construct exceeds 0.50, suggesting convergent validity. The square root of the average variance extracted for all scales exceeds all inter-construct correlations, indicating discriminant validity.

4. Results

4.1. Mediation effect

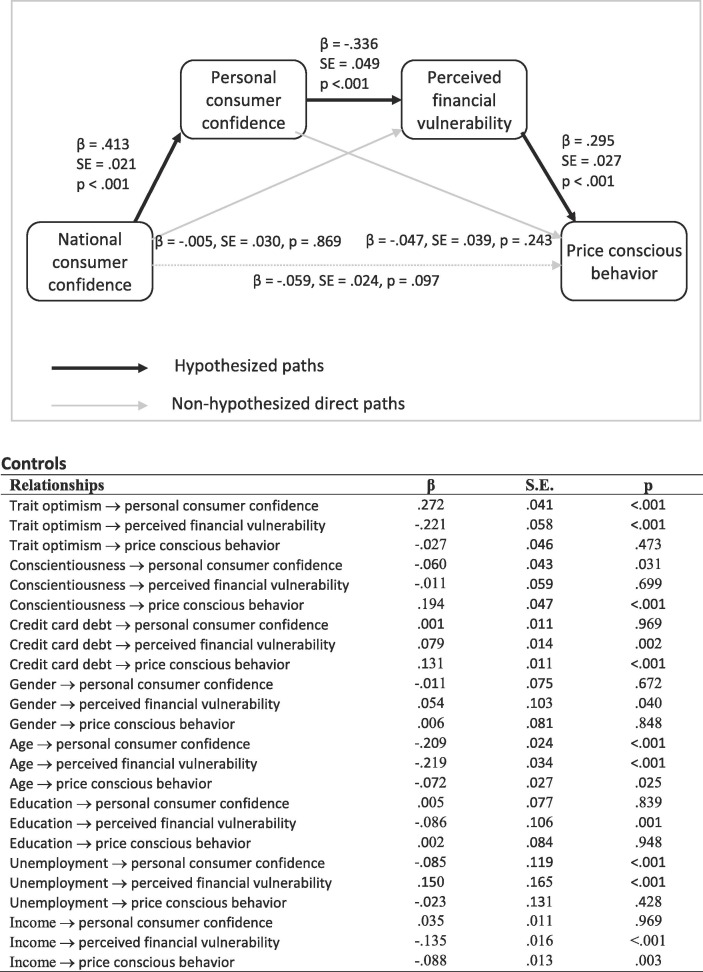

We used structural equation modelling (AMOS 22) to assess the direct and indirect paths in our model. Direct path coefficients are displayed in Fig. 3 . To assess the strength of the hypothesized mediation effects, we performed indirect effect tests with 2,000 bootstrap samples. We specified three user-defined standardized path estimates in AMOS visual basic scripts representing the following indirect paths: (1) the effect of NCC on perceived financial vulnerability via PCC, (2) the effect of PCC on price conscious behavior via perceived financial vulnerability, and (3) the effect of NCC on price conscious behavior via PCC and perceived financial vulnerability. The results of the mediation analyses are presented in Table 4 , which includes the standardized estimates of the indirect effects, their p-values, and the lower-level confidence interval (LLCI) and upper-level confidence interval (ULCI).

Fig. 3.

Standardized path co-efficients.

Table 4.

Indirect effects (2000 bootstrap samples).

| Path | Estimate | p-value | 95% Confidence interval |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower level | Upper level | |||

| H1: NCC → PCC → PFV | −0.129 | 0.001 | −0.175 | −0.095 |

| H2: PCC → PFV → PCB | −0.095 | 0.001 | −0.136 | −0.064 |

| NCC → PCC → PFV → PCB | −0.027 | 0.001 | −0.040 | −0.018 |

Notes: NCC = national consumer confidence, PCC = personal consumer confidence, PFV = perceived financial vulnerability, PCB = price conscious behavior.

H1 predicted a negative indirect relationship between NCC and perceived financial vulnerability via PCC. Results show that NCC is positively and significantly associated with PCC (β = 0.41, p < .001) and that PCC is negatively and significantly associated with perceived financial vulnerability (β = −0.34, p < .001). These coefficients produced a significant indirect effect (β = −0.13, p = .001), with the bias correct confidence interval of this effect excluding zero (LLCI = −0.18, ULCI = −0.10). Thus, H1 is supported. H2 predicted an indirect relationship between PCC and price conscious behavior via perceived financial vulnerability. Results show that PCC is negatively and significantly associated with perceived financial vulnerability (β = −0.34, p < .001) and that perceived financial vulnerability is positively and significantly associated with price conscious behavior (β = 0.30, p < .001). These coefficients produced a positive indirect effect (β = −0.10, p = .001), with the bias correct confidence interval of this effect excluding zero (LLCI = -0.14, ULCI = -0.06). Thus, H2 is supported.

4.2. Moderated mediation effects

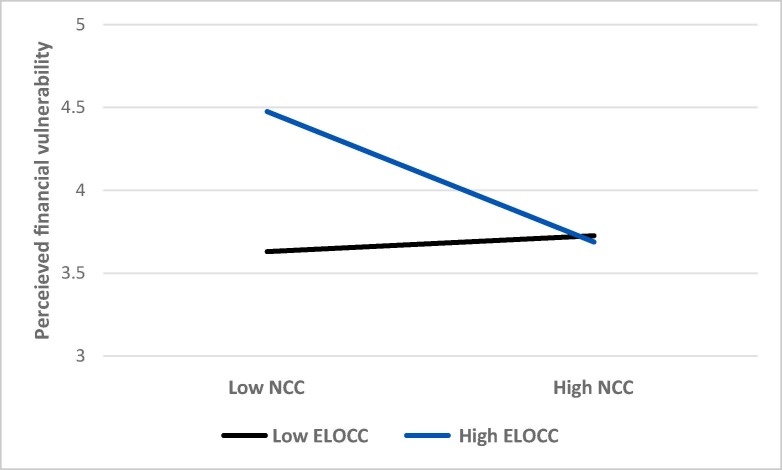

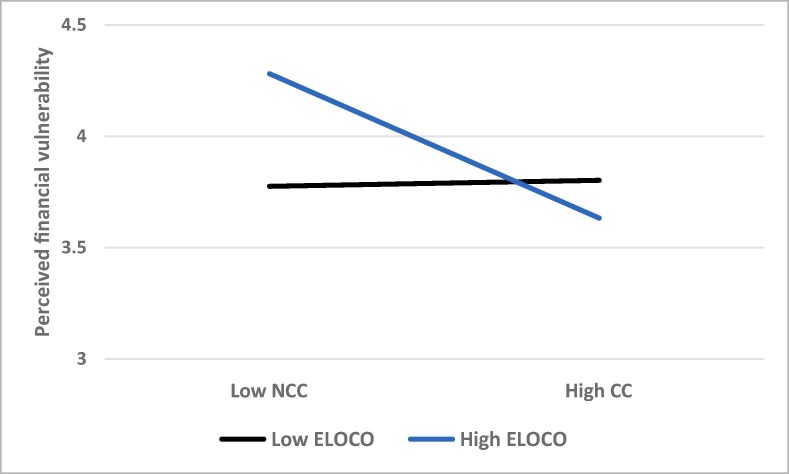

To examine the moderation effects of the two types of external locus of control, we ran moderated mediation analyses (Hayes, 2013) using the SPSS macro PROCESS (model 8, 2,000 bootstrap samples). Results in Table 5 show that the indirect effect of NCC on perceived financial vulnerability via PCC is stronger at higher (vs. lower) levels of chance control (index of moderated mediation: β = −0.02) and the confidence interval for the index of moderated mediation did not include zero (LLCI = −0.02, ULCI = −0.05). Therefore, H3a is supported. Results in Table 6 show that indirect effect of NCC on perceived financial vulnerability via PCC is stronger at higher (vs. lower) levels of control by powerful others (index of moderated mediation: β = −0.02) and the confidence interval for the index of moderated mediation did not include zero (LLCI = −0.02: ULCI = −0.01). Thus, H3b is supported.

Table 5.

Moderating role of external locus of control (chance control) (PROCESS Model 8).

| β | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditional direct effects of NCC on perceived financial vulnerability | ||||

| Chance control: Mean – 1 SD | 0.023 ns | 0.037 | −0.051 | 0.095 |

| Chance control: Mean | −0.085* | 0.030 | −0.144 | −0.025 |

| Chance control: Mean + 1 SD | −0.192** | 0.038 | −0.267 | −0.117 |

| Interaction effect | −0.077** | 0.016 | −0.134 | −0.071 |

| Conditional indirect effects of NCC on perceived financial vulnerability via PCC | ||||

| Chance control: Mean – 1 SD | −0.102 | 0.017 | −0.138 | −0.071 |

| Chance control: Mean | −0.121 | 0.017 | −0.156 | −0.089 |

| Chance control: Mean + 1 SD | −0.140 | 0.019 | −0.180 | −0.103 |

| Index of moderated mediation | −0.015 | 0.005 | −0.024 | −0.045 |

Notes: * p < .01, ** p < .001, ns = not significant, SD = standard deviation, SE = standard error, LLCI = lower level (2.5%) confidence interval, ULCI = upper level (2.5%) confidence interval.

Table 6.

Moderating role of external locus of control (control by powerful others) (PROCESS Model 8).

| β | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditional direct effects of NCC on perceived financial vulnerability | ||||

| CPO: Mean – 1 SD | 0.013 ns | 0.038 | −0.062 | 0.087 |

| CPO: Mean | −0.073* | 0.030 | −0.132 | −0.013 |

| CPO: Mean + 1 SD | −0.158** | 0.038 | −0.232 | −0.084 |

| Interaction effect | −0.053** | 0.014 | −0.081 | −0.026 |

| Conditional indirect effects of NCC on perceived financial vulnerability via PCC | ||||

| CPO: Mean – 1 SD | −0.096 | 0.017 | -0.132 | -0.065 |

| CPO: Mean | −0.120 | 0.017 | −0.155 | −0.089 |

| CPO: Mean + 1 SD | −0.147 | 0.020 | −0.182 | −0.105 |

| Index of moderated mediation | −0.015 | 0.004 | −0.023 | −0.007 |

Notes: * p < .001, ns = not significant, CPO = control by powerful others, SD = standard deviation, SE = standard error, LLCI = lower level (2.5%) confidence interval, ULCI = upper level (2.5%) confidence interval.

Beyond our hypotheses, results of the moderated mediation analyses also reveal direct interaction effects of NCC and both external locus of control dimensions on perceived financial vulnerability: NCC × chance control (Table 5: β = −0.08, p < .001); NCC × control by powerful others (Table 6: β = −0.05, p < .001). At higher levels of both external locus of control dimensions, NCC exerts negative direct impacts on perceived financial vulnerability; at lower levels of external locus of control, there is no significant effect (see Fig. 4 and Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 4.

Moderation effect of national consumer confidence and external locus of control (chance control) on perceived financial vulnerability. Notes: NCC = national consumer confidence, ELOCC = External locus of control (chance control).

Fig. 5.

Moderation effect of national consumer confidence and external locus of control (control by powerful others) on perceived financial vulnerability. Notes: NCC = national consumer confidence, ELOCO = External locus of control (powerful others).

4.3. Rival model

In conceptualizing the influences of NCC, PCC, and perceived financial vulnerability on price conscious behavior, it is plausible to propose relationships other than those in our hypothesized model. We tested a rival model in which the personal-level financial constructs – PCC and perceived financial vulnerability – were treated as antecedents of NCC, which in turn predicts price conscious behavior. Several theories from the psychology literature, notably mental heuristics and cognitive biases (Epley, Keysar, Van Boven, & Gilovich, 2004), suggest that sometimes people make sense of the social world (e.g., the economy) through personal experience. Hypothetically, an individual’s experience of job loss or other markers of financial vulnerability, might lead them to infer that the entire economy is suffering. Although the model demonstrates adequate fit (χ2/d.f. = 3.66; NFI = 0.95; CFI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.05; SRMR = 0.05), a χ2 comparison test shows that the original model has significantly superior fit (χ2 diff. 129.02, p < .001), thus enhancing our confidence in the proposed model.

5. Discussion and implications

Through this research, we attempted to answer three questions about consumer confidence. Is consumer confidence a singular construct, as implied by previous research? We find converging evidence from secondary data and our survey that there are distinct types of consumer confidence, national consumer confidence (NCC) and personal consumer confidence (PCC). This distinction is key to understanding consumers’ affective and behavioral responses. Next, we asked about the psychological mechanisms through which consumer confidence leads to changes in price conscious behavior. Results show that the relationship comprises cognitive and affective components: PCC (a cognitive appraisal) mediates the relationship between NCC and perceived financial vulnerability (an affective construct); in turn, perceived financial vulnerability mediates the relationship between PCC and price conscious behavior. Finally, we were interested in whether or not consumer-level factors influence the effects of consumer confidence. Our findings indicate that the influence of NCC is significantly stronger for consumers with high (vs. low) external locus of control.

5.1. Theoretical contributions

Our model demonstrates that the relationship between consumer confidence and consumer spending is more complex than has previously been understood. Most prior studies examine a direct relationship between consumer confidence and consumer behavior, with mixed empirical results. We identify cognitive and affective mediators of this relationship, showing that whether or not subjective evaluations of the national economy lead to behavioral changes depends on whether a) individuals feel personally financially affected and b) if their level of personal financial affectedness is strong enough to evoke emotional feelings of financial vulnerability. Drawing on cognitive appraisal theory, ours is the first study to distinguish between two types of consumer confidence: NCC and PCC. The distinction helps to address an important mechanism: that consumers’ perception of the national economy affects their perception of vulnerability due to their evaluation of personal affectedness. This finding reveals a potential limitation of conflating measures of national and personal consumer confidence into a single index because this masks the more central role of personal consumer confidence.

Further, our results suggest that the modest effects of consumer confidence observed in prior empirical studies might be attributed to their aggregate level of analysis. That is, we are not aware of any previous study that compares the relative effects of consumer confidence on different segments of consumers. Drawing on attribution theory, our results demonstrate that the effects of consumer confidence depend on individuals’ locus of control. Our finding that those with a high (vs. low) external locus of control have higher financial vulnerability conforms with prior studies that show externals are more susceptible to lowered well-being in response to stressors (Campbell and Sedikides, 1999, Debus et al., 2014).

Our work contributes to understanding of financial vulnerability, a construct of interest to academics and practitioners in as diverse fields as marketing (O’Connor et al., 2019), clinical psychology (Rios & Zautra, 2011), and sociology (O’Loughlin et al., 2017). Scholars have identified a range of individual-level factors that account for experiences of financial vulnerability, including lower cognitive abilities, shorter time horizons, and less experience with financial systems (O’Connor et al., 2019). We introduce a new mechanism, based on attribution theory, that accounts for varying levels of vulnerability between different consumer segments in response to perceptions of macroeconomic gloom. Therefore, we shed more light on the interplay of external and internal factors that evoke perceived financial vulnerability.

5.2. Practical implications

Consumer confidence data are collected in more than 60 countries by governmental institutions and commercial market research agencies such as Nielsen, GfK, and Ipsos. Our results support the use of consumer confidence indices as a means to predict changes in consumer behavior, with caveats. Evidence of distinct types of consumer confidence leads us to recommend providers of consumer confidence data to present both the NCC and PCC sub-indices, in addition to (preferably instead of) the typical average of the two. If such disaggregation is not provided, users of the data, including economic forecasters, business analysts, and marketers, can access item-level consumer confidence data and create their own sub-indices (for example, as we did for Fig. 1). In particular, our evidence suggests that while the NCC sub-index provides some insight, it is the PCC sub-index that will give a clearer indication of future changes in spending behavior.

In relation to financial vulnerability, our results point to specific pathways to educate people about how to make more financially sound decisions. Financial education aims to improve financial literacy and decision-making among various audiences, including people with money-related health problems, high-school students, and consumers. Typically, financial literacy tests ask questions related to quantitative skills, such as the ability to interpret interest rates (e.g., Carpena, Cole, Shapiro, & Zia, 2019). There is an absence of content on how to educate individuals to understand the effects of macroeconomic conditions on personal finances. Our results suggest that it is imperative that individuals are taught how to recognize their own attribution biases and how these might impact their perceived vulnerability to macroeconomic conditions. Specifically, those with high external locus of control would especially benefit from education that explains the direct and indirect ways through which objective economic indicators influence their personal finances, something that their attribution bias might cloud. Indeed, externals might be oversensitive to changes in economic conditions. Their heightened sense of financial vulnerability is potentially dangerous if that perceived vulnerability leads to other psychological problems, such as low self-esteem and depression (O’Loughlin et al., 2017). Education and counselling that allows consumers to make more objective appraisals might free them from the deleterious consequences of such bias.

6. Limitations and future research

From a methodology perspective, our cross-sectional research design does not allow us to establish causality. Future work might therefore adopt experimental research to ascertain the effects of consumer confidence. Our one country sample might also be considered a limitation. Are the findings of our study generalizable across different cultural and socio-economic contexts? Our data are from an individualistic culture (U.S.). Does NCC have a more direct impact on the behavior of consumers in more collectivist societies in which consumers tend to more strongly assimilate societal and community issues in their decision-making? Addressing such research questions would help to establish the generalizability of our model and identify its boundary conditions.

Theoretical lenses other than cognitive appraisal theory and attribution theory might help to shed more light on the influence of consumer confidence on financial vulnerability. From an economic psychology perspective, what role does financial literacy play in explaining the relationship? In addition to locus of control, are there any other personality and individual difference constructs that reveal further heterogeneity in how people respond to changes in NCC? Which situational factors might also moderate the effects of NCC on perceived financial vulnerability?

From a conceptual perspective, a limitation of our paper is an exclusive focus on the subjective “feelings” dimension of financial vulnerability (O’Connor et al., 2019). Financial vulnerability also has an objective dimension, which includes the value of capital resources a consumer has at their disposal to prevent them from risk of financial hardship (e.g., a lack of credit, high debt, and low emergency savings) (O’Connor et al., 2019). Although recent research demonstrates that subjective financial indicators have a stronger influence on consumer spending (Netemeyer et al., 2018), aligning consumers’ objective and subjective financial vulnerability estimates is key to optimal financial health because it will eradicate overconfidence and unforeseen issues. Therefore, future research might examine the relationships between consumer confidence and objective and subjective measures of financial vulnerability.

Our research contributes to literature on the effects of NCC (Table 1). Given the important downstream consequences of NCC, more research is required on its antecedents. To date, studies have identified contextual predictors of consumer confidence, including objective economic indicators (e.g., inflation rate) and media “spin” (Soroka, Stecula, & Wlezien, 2015) but say little about individual-level predictors. Research from the broader psychology literature suggests that mental heuristics and cognitive biases can dictate how people form evaluations of macroenvironmental issues (Epley and Gilovich, 2006, Epley et al., 2004, Mase et al., 2015). To what extent do such cognitive mechanisms influence consumer confidence? Such information would be useful from a financial counselling and education perspective because they might reveal reasons that prevent people making sound evaluations, which might ultimately lead to inaccurate judgements of their own levels of financial vulnerability. Therefore, knowledge of the antecedents of NCC might provide diagnostics that inform the development of more precisely targeted financial literacy interventions.

Finally, we encourage research on the effects of consumer confidence on other types of consumer behavior and the mechanisms of these effects. Our paper focused on one affective variable (perceived financial vulnerability) and one behavioral variable (price conscious behavior). What are the other affective and behavioral consequences of consumer confidence? For example, examination of publicly visible consumption (e.g., conspicuous consumption) would be interesting. Prior research suggests that such consumption patterns are subject to social scrutiny during economic contractions because it is deemed improper to display wealth when many people are struggling financially (Nunes, Drèze, & Han, 2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant numbers: 71972040, 71602033, 71972038, 71832015] and the Young Scholar Grant of University of International Business and Economics [grant number: 18YQ05]. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers, and the editors for their constructive comments on this paper.

Biographies

Dr. Daniel P Hampson. Daniel Hampson is an Assistant Professor in Marketing at the University of International Business and Economics, Beijing. His research, broadly in the areas of consumer and salespeople psychology and behaviour, has been published in the Journal of Business Research, Journal of Business Ethics, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, and Journal of Knowledge Management, among others. Prior to his academic career, Daniel was a business analyst for Bombardier Transportation.

Dr. Shiyang Gong. Shiyang Gong is an Associate Professor in Marketing at the University of International Business and Economics, Beijing. He studies marketing strategies and marketing models in today’s dynamic marketing context. His research has been published in premier academic journals (e.g., Journal of Marketing Research, Psychological Science), and featured in major media outlets (e.g., Yahoo!, Marketing Science Institute). He received his PhD from Tsinghua University and his BA from Beijing Normal University.

Dr. Yi Xie. Yi Xie is a Professor in Marketing at the University of International Business and Economics, Beijing. Her research focuses on brand management and consumer psychology. Her research has been published Journal of Consumer Research, Journal of International Marketing, Journal of Advertising, Industrial Marketing Management, and Journal of Brand Management, among others. She received her PhD from Peking University.

References

- Abrantes-Braga F.D.M., Veludo-de-Oliveira T. Help me, I can’t afford it! Antecedents and consequence of risky indebtedness behavior. European Journal of Marketing. 2020 doi: 10.1108/EJM-06-2019-0455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, J. & Cuddy, J.C. (2018). Measuring consumer confidence isn’t useful anymore. Here’s what we should do instead. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/08/measuring-consumer-confidence-isn-t-useful-anymore-here-s-what-we-should-do-instead/.

- Anderloni L., Bacchiocchi E., Vandone D. Household financial vulnerability: An empirical analysis. Research in Economics. 2012;66(3):284–296. doi: 10.1016/j.rie.2012.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Argento R., Bryant V.L., Sabelhaus J. Early withdrawals from retirement accounts during the Great Recession. Contemporary Economic Policy. 2015;33(1):1–16. doi: 10.1111/coep.12064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer C., Lütticke R., Pham-Dao L., Tjaden V. Precautionary savings, illiquid assets, and the aggregate consequences of shocks to household income risk. Econometrica. 2019;87(1):255–290. doi: 10.3982/ECTA13601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benet-Martínez V., John O.P. Los Cinco Grandes across cultures and ethnic groups: Multitrait-multimethod analyses of the Big Five in Spanish and English. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75(3):729–750. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.3.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benhabib J., Spiegel M.M. Sentiments and economic activity: Evidence from US states. The Economic Journal. 2019;129(618):715–733. doi: 10.1111/ecoj.12605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brüggen E., Hogreve J., Holmlund M., Kabadayi S., Löfgren M. Financial well-being: A conceptualization and research agenda. Journal of Business Research. 2017;79:228–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.03.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Economic Analysis (2020). Personal savings rate. https://www.bea.gov/data/income-saving/personal-saving-rate.

- Campbell W.K., Sedikides C. Self-threat magnifies the self-serving bias: A meta-analytic integration. Review of General Psychology. 1999;3(1):23–43. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.3.1.23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carpena F., Cole S., Shapiro J., Zia B. The ABCs of financial education: Experimental evidence on attitudes, behavior, and cognitive biases. Management Science. 2019;65(1):346–369. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.2017.2819. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carver C.S., Scheier M.F., Segerstrom S.C. Optimism. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(7):879–889. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombia University Irving Medical Centre (2020). Google searches during pandemic hint at future increase in suicide. https://www.cuimc.columbia.edu/news/google-searches-during-pandemic-hint-future-increase-suicide-0.

- Cotsomitis J.A., Kwan A.C. Can consumer confidence forecast household spending? Evidence from the European Commission business and consumer surveys. Southern Economic Journal. 2006;72(3):597–610. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20111835 [Google Scholar]

- Debus M.E., Konig C.J., Kleinmann M. The building blocks of job insecurity: The impact of environmental and person-related variables on job insecurity perceptions. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2014;87(2):329–351. doi: 10.1111/joop.12049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte (2020). COVID-19 drives lasting changes in global consumer behavior and businesses operations. https://www2.deloitte.com/global/en/blog/responsible-business-blog/2020/covid-19-drives-lasting-changes-in-global-consumer-behavior-and-businesses-operations.html#.

- Dees S., Brinca P.S. Consumer confidence as a predictor of consumption spending: Evidence for the United States and the Euro area. International Economics. 2013;134:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.inteco.2013.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly G., Iyer R., Howell R.T. The Big Five personality traits, material values, and financial well-being of self-described money managers. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2012;33(6):1129–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2012.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dragouni M., Filis G., Gavriilidis K., Santamaria D. Sentiment, mood and outbound tourism demand. Annals of Tourism Research. 2016;60:80–96. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2016.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elsby M.W., Shin D., Solon G. Wage adjustment in the Great Recession and other downturns: Evidence from the United States and Great Britain. Journal of Labor Economics. 2016;34(S1):S249–S291. doi: 10.1086/682407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Epley N., Gilovich T. The anchoring-and-adjustment heuristic: Why the adjustments are insufficient. Psychological Science. 2006;17(4):311–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epley N., Keysar B., Van Boven L., Gilovich T. Perspective taking as egocentric anchoring and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;87(3):327–339. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (2020). Time series: Business and consumer survey database files. https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/indicators-statistics/economic-databases/business-and-consumer-surveys/download-business-and-consumer-survey-data/time-series_en.

- Faber J.W. Segregation and the cost of money: Race, poverty, and the prevalence of alternative financial institutions. Social Forces. 2019;98(2):819–848. doi: 10.1093/sf/soy129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan C.S., Wong P. Does consumer sentiment forecast household spending? The Hong Kong case. Economics Letters. 1998;58(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1765(97)00247-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farías P. Determinants of knowledge of personal loans' total costs: How price consciousness, financial literacy, purchase recency and frequency work together. Journal of Business Research. 2019;102:212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.01.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Financial Times (2020). US economy in peril as unemployment payments expire https://www.ft.com/content/636a74fa-b95a-42af-b49a-91c147cfab28.

- Folkman S., Lazarus R.S. Springer Publishing Company; New York: 1984. Stress, appraisal, and coping. [Google Scholar]

- Fong L.H.N., Lam L.W., Law R. How locus of control shapes intention to reuse mobile apps for making hotel reservations: Evidence from Chinese consumers. Tourism Management. 2017;61:331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2017.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fornell C., Larcker D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research. 1981;18(3):382–388. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galvin B.M., Randel A.E., Collins B.J., Johnson R.E. Changing the focus of locus (of control): A targeted review of the locus of control literature and agenda for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2018;39(7):820–833. doi: 10.1002/job.2275. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben J.R., Neveu J.P., Paustian-Underdahl S.C., Westman M. Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management. 2014;40(5):1334–1364. doi: 10.1177/0149206314527130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson D.P., Ma S.S., Wang Y. Perceived financial well-being and its effect on domestic product purchases. International Marketing Review. 2018;35(6):914–935. doi: 10.1108/IMR-12-2017-0248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson D.P., McGoldrick P.J. Antecedents of consumer price consciousness in a turbulent economy. International Journal of Consumer Studies. 2017;41(4):404–414. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A.F. Guilford; New York, NY: 2013. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. [Google Scholar]

- He T., Derfler-Rozin R., Pitesa M. Financial vulnerability and the reproduction of disadvantage in economic exchanges. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2020;105(1):80–96. doi: 10.1037/apl0000427. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/apl0000427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunneman A., Verhoef P.C., Sloot L.M. The impact of consumer confidence on store satisfaction and share of wallet formation. Journal of Retailing. 2015;91(3):516–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jretai.2015.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Hu X., Liu Z., Sun X., Xue G. Greed as an adaptation to anomie: The mediating role of belief in a zero-sum game and the buffering effect of internal locus of control. Personality and Individual Differences. 2020;152 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2019.109566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koschate-Fischer N., Hoyer W.D., Stokburger-Sauer N.E., Engling J. Do life events always lead to change in purchase? The mediating role of change in consumer innovativeness, the variety seeking tendency, and price consciousness. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 2018;46(3):516–536. doi: 10.1007/s11747-017-0548-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson H. In: Lefcourt H.M., editor. Vol. 1. Academic Press; New York, NY: 1981. Differentiating among internality, powerful others, and chance; pp. 15–63. (Research with the locus of control construct). [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Lepp A., Barkley J.E. Locus of control and cell phone use: Implications for sleep quality, academic performance, and subjective well-being. Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;52:450–457. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.06.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein D.R., Ridgway N.M., Netemeyer R.G. Price perceptions and consumer shopping behavior. Journal of Marketing Research. 1993;30(2):234–245. doi: 10.1177/002224379303000208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindell M.K., Whitney D.J. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2001;86(1):114–121. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.114. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe T.S. Perceived job and labor market insecurity in the United States: An assessment of workers’ attitudes from 2002 to 2014. Work and Occupations. 2018;45(3):313–345. doi: 10.1177/0730888418758381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ludvigson S.C. Consumer confidence and consumer spending. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2004;18(2):29–50. doi: 10.1257/0895330041371222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mase A.S., Cho H., Prokopy L.S. Enhancing the Social Amplification of Risk Framework (SARF) by exploring trust, the availability heuristic, and agricultural advisors' belief in climate change. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2015;41:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moschis G.P. Stress and consumer behavior. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 2007;35(3):430–444. doi: 10.1007/s11747-007-0035-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Munnell A.H., Rutledge M.S. The effects of the Great Recession on the retirement security of older workers. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2013;650(1):124–142. doi: 10.1177/0002716213499535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Netemeyer R.G., Warmath D., Fernandes D., Lynch J.G., Jr How am I doing? Perceived financial well-being, its potential antecedents, and its relation to overall well-being. Journal of Consumer Research. 2018;45(1):68–89. doi: 10.1093/jcr/ucx109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ng T.W.H., Sorensen K.L., Eby L.T. Locus of control at work: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2006;27(8):1057–1087. doi: 10.1002/job.416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes J.C., Drèze X., Han Y.J. Conspicuous consumption in a recession: Toning it down or turning it up? Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2011;21(2):199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2010.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor G.E., Newmeyer C.E., Wong N.Y.C., Bayuk J.B., Cook L.A., Komarova Y.…Warmath D. Conceptualizing the multiple dimensions of consumer financial vulnerability. Journal of Business Research. 2019;100:421–430. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.12.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Loughlin D.M., Szmigin I., McEachern M.G., Barbosa B., Karantinou K., Fernández-Moya M.E. Man thou art dust: Rites of passage in austere times. Sociology. 2017;51(5):1050–1066. doi: 10.1177/0038038516633037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou Y.C., de Vries L., Wiesel T., Verhoef P.C. The role of consumer confidence in creating customer loyalty. Journal of Service Research. 2014;17(3):339–354. doi: 10.1177/1094670513513925. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff P.M., MacKenzie S.B., Podsakoff N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology. 2012;63(1):539–569. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reknes I., Visockaite G., Liefooghe A., Lovakov A., Einarsen S.V. Locus of control moderates the relationship between exposure to bullying behaviors and psychological strain. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019;10 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuters (2020). U.S. consumer spending presses ahead; declining income poses challenge https://uk.reuters.com/article/us-usa-economy/u-s-consumer-spending-presses-ahead-declining-income-poses-challenge-idUKKCN24W1YW.

- Rios R., Zautra A.J. Socioeconomic disparities in pain: The role of economic hardship and daily financial worry. Health Psychology. 2011;30(1):58–66. doi: 10.1037/a0022025. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0022025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotter J.B. Prentice Hall; New York, NY: 1954. Social learning and clinical psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury L.C., Zhao M. Active choice format and minimum payment warnings in credit card repayment decisions. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing. 2019;39(3):284–304. doi: 10.1177/0743915619868691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier M.F., Carver C.S., Bridges M.W. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67(6):1063–1078. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepperd J., Malone W., Sweeny K. Exploring causes of the self-serving bias. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2008;2(2):895–908. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00078.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singal M. Effect of consumer sentiment on hospitality expenditures and stock returns. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2012;31(2):511–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.07.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha I., Batra R. The effect of consumer price consciousness on private label purchase. International Journal of Research in Marketing. 1999;16(3):237–251. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8116(99)00013-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soroka S.N., Stecula D.A., Wlezien C. It's (change in) the (future) economy, stupid: Economic indicators, the media, and public opinion. American Journal of Political Science. 2015;59(2):457–474. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Guardian (2020). Consumer confidence survey casts doubt on v-shaped recovery. https://www.theguardian.com/money/2020/jul/24/consumer-confidence-survey-casts-doubt-on-v-shaped-recovery.

- The Times (2020). Lloyds predicts £4bn hit from bad debts as income slumps https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/lloyds-predicts-4bn-hit-from-bad-debts-as-income-slumps-mql9879pk.

- Treanor M. The effects of financial vulnerability and mothers’ emotional distress on child social, emotional and behavioral well-being: A structural equation model. Sociology. 2016;50(4):673–694. doi: 10.1177/0038038515570144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge J.M., Zhang L., Im C. It's beyond my control: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of increasing externality in locus of control, 1960–2002. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2004;8(3):308–319. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0803_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Briley D.A., Brown J.R., Roberts B.W. Genetic and environmental influences on household financial distress. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 2017;142:404–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]