Abstract

Background/Aim:

Biliary tree and pancreatic duct can appear in different variations whose proper understanding is obligatory for surgeons. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is considered a safe and accurate tool for evaluating biliary tree and pancreatic duct. Typical anatomy for right hepatic duct (RHD) and left hepatic duct (LHD) is reported as 57% and 63%, respectively. The most common (4-10%) pancreatic anomaly is divisum. In the present study, we evaluated and determined the prevalence of biliary tree and pancreatic duct variations among patients at a university hospital.

Materials and Methods:

The MRCP records of 370 patients from 2015 to 2017 were obtained for cross-sectional study. Images were retrospectively reviewed for variations by two independent senior radiologists. Demographic data were obtained for all the patients. Huang et al. classification was used for RHD and LHD variations. The cystic duct was reported based on its course and insertion pattern. The pancreatic duct was observed for the presence of divisum, its course, and configuration.

Results:

Three hundred and twenty-five patients were included in the final study. Most commonly observed variant for RHD were A1 (34.2%) and A2 (32.2%). For LHD, B1 (71.4%) was the most common variant. Cystic duct insertion was commonly seen as right lateral insertion (27.7%). Pancreatic divisum was observed in 0.6% of cases. Nationality, origin, and gender-specific variations were obtained.

Conclusion:

Variations in biliary anatomy and pancreatic duct are very diverse and extend from the intrahepatic biliary system down to the pancreas. Performing a similar study on a larger population is mandatory to illustrate the range of variations present within the community.

Keywords: Biliary tree, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, pancreatic duct, variations

INTRODUCTION

The biliary tree and pancreatic duct anatomy are widely variable.[1,2] The complexity of the biliary tree and pancreatic duct needs proper understanding.[1] Acknowledgment of such variations is necessary for pre-operative planning to avoid undesirable complications.[1,2,3] Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is considered to be a noninvasive, safe, and accurate modality for the evaluation of the biliary tree and pancreatic duct.[1,3] As described by Couinaud, the biliary system is formed by multiple hepatic ducts draining hepatic segments.[4] The common hepatic duct (CHD) is formed by the union of the right hepatic duct (RHD), which drains segments 5 to 8 and the left hepatic duct (LHD), which drains segments 1 to 4. Multiple classification systems were developed for variations in the RHD and LHD including Huang et al. classification.[4] As classified by Huang et al., the RHD is usually formed by the union of the right anterior segmental duct (RASD), which drains segments 5 and 8 and the right posterior segmental duct (RPSD), which drains segments 6 and 7. This type of anatomy is typical in 57% of the cases. Also, the typical LHD is formed by the union of ducts draining segments 2 and 3 and one or more ducts draining segment 4. This type of anatomy is usually represented by 82% of cases.[4] The cystic duct has its variations based on its length, course, and site of insertion with the CHD.[5]

The most common pancreatic duct congenital variation is pancreatic divisum, with a prevalence of 4-10%.[6] This anomaly occurs when the ventral and dorsal pancreatic ducts fail to fuse during embryologic development.[6,7] There is a spectrum of variations in the course of the pancreatic duct.[8,9] The most common course is a descending course that occurs in about 50% of cases.[8] Other types of possible anatomy include sigmoid, vertical, and loop configurations.[8,9] Ductal configuration is also subjected to variations. The most common configuration is a bifid duct with the dominant duct of Wirsung (major pancreatic duct), which occurs in 60% of cases.[8] Other less common variations in the configuration include an absent duct of Santorini and dominant duct of Santorini without divisum.[8,10]

Anatomical variations are best defined as anomalies that are asymptomatic.[11] However, some may predispose to pathologic conditions.[9,11,12] Hepatobiliary surgery includes transplant, tumor resection, and laparoscopic biliary surgery, which are all prone to complications.[10] Anatomical variations in the biliary tree are expected in 42% of the population.[9] Anatomical variation poses a challenge for the surgeon during the surgical procedure and consideration of these variations is of paramount importance to prevent unnecessary harm to the patients. Hence, in our present study, we aim to evaluate and determine the prevalence of anatomical variations in the biliary tree, cystic duct, and pancreatic duct.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional study was designed to analyze the patients who underwent MRCP for different reasons at our hospital from January 2015 to December 2017. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board of the hospital. A total of 370 MRCPs were extracted from the medical information system. Data for 45 patients were excluded due to poor image quality and grossly distorted anatomy related to different pathologies. Images were reviewed retrospectively by two senior abdominal radiologists. Electronic medical records were reviewed to collect the demographic data including age, gender, and origin (Middle Eastern and non-Middle Eastern).

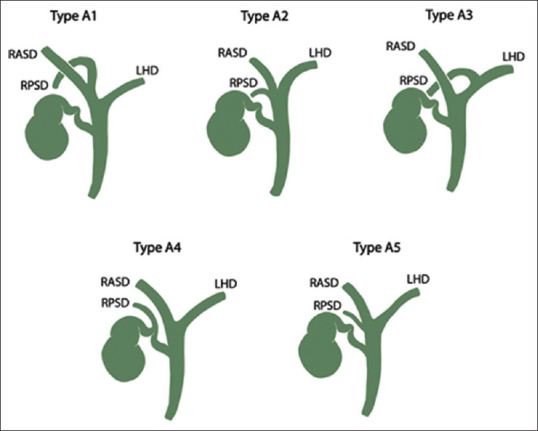

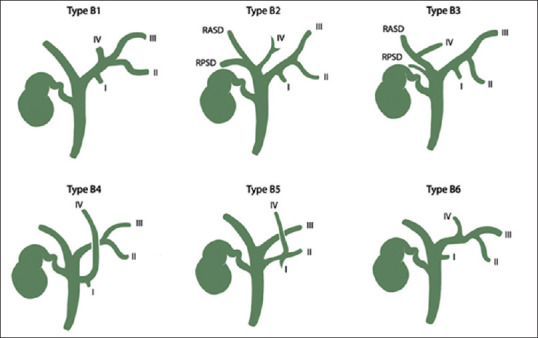

The RHD and LHD were reviewed and classified according to Huang et al. classification.[13] The RHD is classified into five types according to RASD and RPSD insertions: type A1 RPSD drains in the RASD, type 2 is a tri-confluence pattern of RASD, RPSD, and LHD insertion, type A3 RPSD drains in LHD, type A4 RPSD drains in CHD, and type A5 RPSD drains in the cystic duct [Figure 1].[13] The LHD is classified into 6 types according to segment 4 duct insertion: Type B1 segment 4 duct drains into LHD, type B2 segment 4 duct drains into CHD, separately of segments 2 and 3 ducts. Furthermore, type B3 segment 4 duct drains into RASD, type B4 segment 4 duct drains in CHD, type B5 segment 4 duct drains in segment 2 duct, type B6 ducts of segments 2 and 3 join, and segment 4 duct joins to form the LHD [Figure 2].[13]

Figure 1.

Illustration representing the classification of the right hepatic duct according to Huanget al.[4]

Figure 2.

Illustration representing the classification of the left hepatic duct according to Huanget al.[4]

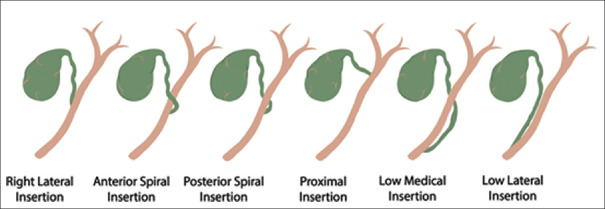

The cystic duct anatomy was classified according to its insertion point into CHD to right lateral insertion, anterior spiral insertion, posterior spiral insertion, high or proximal insertion, low medial insertion, and low lateral insertion.[5] The common bile duct diameter was also measured [Figure 3]. The pancreatic duct was classified according to its course and configuration into descending pancreatic duct, vertical pancreatic duct, sigmoid pancreatic duct, loop pancreatic duct, anomalous union of pancreatic duct and bile duct, persistent duct of Santorini with duct of Wirsung as major draining route, and persistent duct of Santorini with duct of Santorini as a major draining route.[8,10] Also, the presence or absence of divisum was observed. The pancreatic duct diameter was also measured [Figure 4].

Figure 3.

Illustration representing the variations of cystic duct insertion into the common bile duct

Figure 4.

Illustration representing the variations of the pancreatic duct

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). For categorical variables, data were represented as numbers and percentages. For continuous variables, data were presented as means, standard deviation, and range. The prevalence of variations was estimated for the total population. The population was further subdivided into Saudis and non-Saudis, and Middle Eastern and non-Middle Eastern.

RESULTS

A total of 325 patients were enrolled in the study. The average age of patients was 45.92 ± 19.91 years (range: 1–93 years). Out of the total, 200 (61.5%) patients were women. Further, 177 (54.5%) patients were Saudi nationals. A total of 240 (73.8%) patients were of Middle Eastern descent. Demographics of the enrolled patients are shown in Table 1. The MRCP was conducted for various indications. It was done primarily to evaluate biliary stones and jaundice. Other indications for investigation were also included but not exclusively to evaluate biliary tree malignancies and postoperative biliary complications.

Table 1.

Demographics of the patients enrolled in the study

| Demographics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Total number of patients included | 325 |

| Mean age | 45.92±19.91 years (range: 1-93 years) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 122 (37.5%) |

| Female | 200 (61.5%) |

| NA | 3 (0.9%) |

| Nationality | |

| Saudi | 177 (54.5%) |

| Non-Saudi | 145 (44.6%) |

| NA | 3 (0.9%) |

| Origin | |

| Middle Eastern | 240 (73.8%) |

| Non-Middle Eastern | 82 (25.2%) |

| NA | 3 (0.9%) |

Right hepatic duct

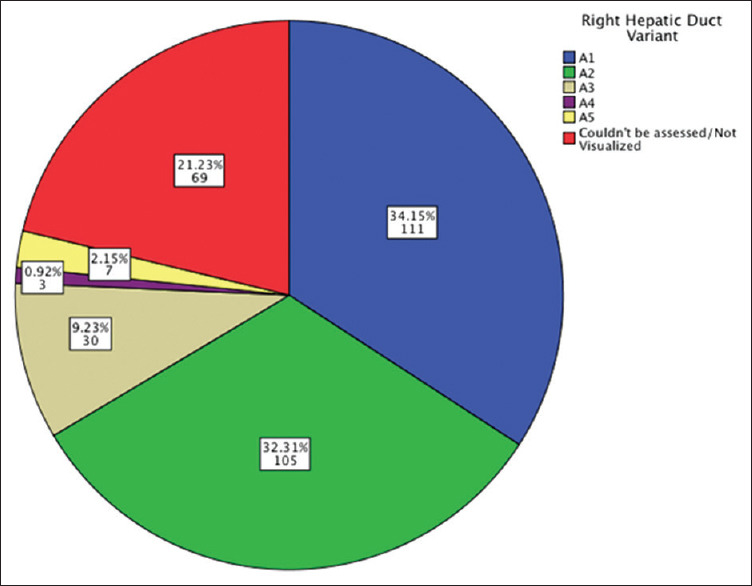

Most commonly observed variants were type A1 and A2 represented in 111 (34.2%) and 105 (32.3%) cases, respectively (Supplementary Figures S1 (157.3KB, tif) and S2 (166.3KB, tif) of MRCP showing Type A1 and A2 variation). It was followed by A3 in 30 (9.2%) cases [Figure 5]. A total of 69 (21.2%) cases could not be assessed/visualized. In the Middle Eastern individuals, the most common variants were A2 (34.6%) as compared to cases in the non-Middle Eastern group with A1 as the most common variants (39%) [Table 2]. Only 3 cases of right posterior hepatic duct insertion in the cystic duct (variant 4) were observed.

Figure 5.

Frequencies of right hepatic duct variants

Table 2.

Number of right hepatic duct variant

| Origin | Right Hepatic Duct Variant |

Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | Couldn’t be assessed/visualized | ||

| Middle Eastern n (%) | 78 (32.5%) | 83 (34.6%) | 22 (9.2%) | 2 (0.8%) | 5 (2.1%) | 50 (20.8%) | 240 |

| Non-Middle Eastern n (%) | 32 (39%) | 21 (25.6%) | 7 (8.5%) | 1 (1.2%) | 2 (2.4%) | 19 (23.2%) | 82 |

Left hepatic duct

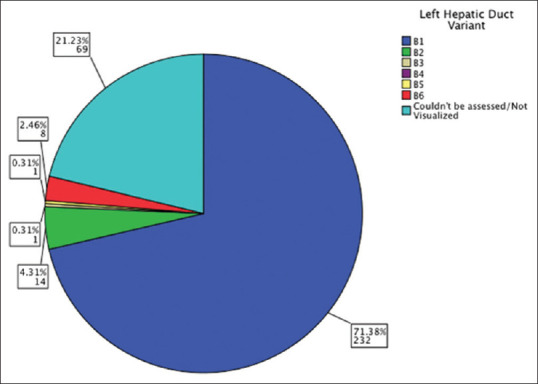

In the case of LDH, the most common variant observed was B1, which was represented by 232 (71.4%) cases followed by B2 in 14 (2.5%) cases [Figure 6]. The origin of specific variants are displayed in Table 3.

Figure 6.

Frequencies of left hepatic duct variants

Table 3.

Number of left hepatic duct variant

| Origin | Left Hepatic Duct Variant |

Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | B2 | B3 | B5 | B6 | Couldn’t be assessed/visualized | ||

| Middle Eastern n (%) | 174 (72.5%) | 10 (4.2%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 | 6 (2.5%) | 49 (20.4%) | 240 |

| Non-Middle Eastern n (%) | 56 (68.3%) | 4 (4.9%) | 0 | 1 (1.2%) | 2 (2.4%) | 19 (23.2%) | 82 |

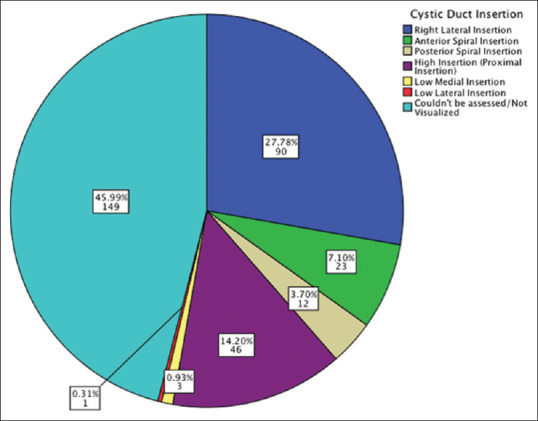

Cystic duct

Right lateral insertion of the cystic duct was the most common insertion variant as seen in 90 (27.7%) cases. The high insertion (proximal insertion) was seen in 46 (14.2%) cases [Figure 7 and Table 4].

Figure 7.

Frequencies of cystic duct insertion variations

Table 4.

Number of cystic duct insertion

| Origin | Cystic Duct Insertion |

Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right Lateral Insertion | Anterior Spiral Insertion | Posterior Spiral Insertion | High Insertion | Low Medial Insertion | Low Lateral Insertion | Couldn’t be assessed/visualized | ||

| Middle Eastern n (%) | 69 (28.9%) | 16 (6.7%) | 8 (3.3%) | 33 (13.8%) | 2 (0.8%) | 1 (0.4%) | 110 (46%) | 177 |

| Non-Middle Eastern n (%) | 19 (23.2%) | 7 (8.5%) | 4 (4.9%) | 12 (14.6%) | 1 (1.2%) | 0 | 39 (47.6%) | 145 |

Pancreatic duct and common hepatic duct

Pancreatic divisum was observed in two (0.6%) cases only. The most common pancreatic duct course was a descending duct as observed in 126 (38.8%) cases. In the evaluated cases, an average diameter of the pancreatic duct was 2.22 ± 1.5 mm (range: 0.5–13 mm) and the average diameter of the CBD was 7.57 ± 4.66 mm (range: 1.5–36 mm).

DISCUSSION

Hepatobiliary and pancreatic anatomy could be challenging for any surgeon.[14] Knowledge of the possible variations could provide the surgeon with better control to prevent any unwanted outcomes.[14,15] Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a common and accepted procedure worldwide.[15] However, like any procedure, undesirable complications may occur, such as injuries to CBD or hepatic bile ducts, which impose a burden on the patients.[14,15] These complications could occur while clipping or transecting a duct other than the cystic duct.[14,15] Along with other procedures such as liver resection or transplantation (which has their own complications), it requires proper anatomical awareness and perception of possible different hepatic duct insertions and cystic duct course and length to minimize complications.[4,5,14,15] By far, pancreatic divisum is considered as the most common anomaly of the pancreas, which is caused by the failure of fusion between normal ventral and dorsal pancreatic duct.[7,8,10,16] Pancreatic divisum, in some studies, was implicated as a cause of chronic pancreatitis.[17,18] A recently published systemic review has dismissed pancreatic divisum as a cause for chronic pancreatitis.[10]

MRCP is a valuable tool, which became more widely available in recent years.[3,19,20] It provides a noninvasive and accurate depiction of the hepatobiliary and pancreatic anatomy.[3,5,8,20,21] It could be used to assess biliary tree variations and pancreatic anomalies.[3,5,8] Other modalities available such as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography could achieve the same results, however, it is considered as an invasive method with a risk of developing procedure-related complications.[4] In our present study, the most common variation for RHD was A1 (34.2%) followed by A2 (32.3%). Table 5 shows the common variations of RHD in our study compared with previous studies. The most common variation for LHD was B1 (71.4%) followed by B2 (4%). Our results are consistent with what has been reported in the previous studies performed in different populations and regions.[1,4,13] According to a study published in 2014, standard RHD anatomy was reported in 52.9 - 58% of the population and standard LHD anatomy was reported in 63% of the cases.[4] In another study published in 2016, it was revealed that 55.3% of the subjects had normal biliary anatomy and the most common variant was RPSD draining into the LHD, which was present in 27.6% of the subjects.[13] In a study done in 2016, which focused on the cystic duct of 198 patients who underwent MRCP, 51% of the subjects had normal lateral cystic duct insertion at the middle third of CHD.[5]

Table 5.

Right hepatic duct variations as compared to other studies in the literature

| Anatomic variation | Our study (n=325) | Sarawagi R et al.[5] 2016 (n=224) | Abueldahab M et al.[23] 2012 (n=106) | Bageacu S et al.[24] 2011 (n=124) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 34.15% | 55.3% | 63.2% | 50.8% |

| A2 | 32.31% | 9.3% | 10.4% | 9.6% |

| A3 | 9.23% | 27.6% | 17% | 15.3% |

| A4 | 0.9% | 4.0% | 7.5% | 0% |

| A5 | 2.15% | 0.8% | 1.9% | 0% |

| Others/Not visualized | 21.2% | 0% | 0% | 24.19% |

Our study represents data on a multi-ethnic level, representative of the population demographic of the country. In Saudi patients, A2 was the most common variant as seen in 35.2% of cases followed by A1 variant (32.2%). The LHD pattern in Saudis was similar to what has been shown in previous studies.[4,13] Non-Saudis followed a similar pattern in RHD and LHD as compared to other studies.[1,4,13] The people of Middle Eastern origin had comparable patterns as Saudis. Non-Middle Eastern individuals had a comparable pattern as for Non-Saudis. In general, the abundance of A2 variation was higher in our study as compared to other studies.[1,4,13] Pancreatic divisum frequency was lower in our study (0.6%), as compared to what was reported in the previous studies, i.e., 4–14%.[6,8,17]

Our study was limited in that we were not able to obtain the reason for performing MRCP. Also, our study included 325 patients over the span of 2 years. Other studies that followed a similar study design included a range of 100–500 patients.[1,5,13,14,22] Thus, it is recommended to further perform this study on a multicenter basis from different regions of the country to incorporate a larger population and get more demographically representative results.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

MRCP showing type A1 variation. The arrow indicates the union of RASD and RPSD. The symbol ‘star’ indicates the right lateral insertion of the cystic duct

MRCP showing type A2 variation. The figure shows the union of RASD, RPSD, and LHD forming a trifurcation

REFERENCES

- 1.Gupta A, Rai P, Singh V, Gupta RK, Saraswat VA. Intrahepatic biliary duct branching patterns, cystic duct anomalies, and pancreas divisum in a tertiary referral center: A magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticographic study. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2016;35:379–84. doi: 10.1007/s12664-016-0693-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mariolis-Sapsakos T, Kalles V, Papatheodorou K, Goutas N, Papapanagiotou I, Flessas I, et al. Anatomic variations of the right hepatic duct: Results and surgical implications from a cadaveric study. Anat Res Int. 2012;2012:838179. doi: 10.1155/2012/838179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu YB, Bai YL, Min ZG, Qin SY. Magnetic resonance cholangiography in assessing biliary anatomy in living donors: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:8427–34. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i45.8427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaib E, Kanas AF, Galvao FH, D'Albuquerque LA. Bile duct confluence: Anatomic variations and its classification. Surg Radiol Anat. 2014;36:105–9. doi: 10.1007/s00276-013-1157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarawagi R, Sundar S, Gupta SK, Raghuwanshi S. Anatomical variations of cystic ducts in magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and clinical implications. Radiol Res Pract. 2016;2016:3021484. doi: 10.1155/2016/3021484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adibelli ZH, Adatepe M, Isayeva L, Esen OS, Yildirim M. Pancreas divisum: A risk factor for pancreaticobiliarytumors - an analysis of 1628 MR cholangiography examinations. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2017;98:141–7. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adibelli ZH, Adatepe M, Imamoglu C, Esen OS, Erkan N, Yildirim M. Anatomic variations of the pancreatic duct and their relevance with the Cambridge classification system: MRCP findings of 1158 consecutive patients. Radiol Oncol. 2016;50:370–7. doi: 10.1515/raon-2016-0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turkvatan A, Erden A, Turkoglu MA, Yener O. Congenital variants and anomalies of the pancreas and pancreatic duct: Imaging by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography and multidetector computed tomography. Korean J Radiol. 2013;14:905–13. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2013.14.6.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gursoy Coruh A, Gulpinar B, Bas H, Erden A. Frequency of bile duct confluence variations in subjects with pancreas divisum: An analysis of MRCP findings. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2018;24:72–6. doi: 10.5152/dir.2018.17200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dimitriou I, Katsourakis A, Nikolaidou E, Noussios G. The main anatomical variations of the pancreatic duct system: Review of the literature and its importance in surgical practice. J Clin Med Res. 2018;10:370–5. doi: 10.14740/jocmr3344w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pandey A, Mandal R, Lakhey PJ. Rare anomaly of common bile duct in association with distal cholangiocarcinoma. Case Rep Surg. 2018;2018:8351913. doi: 10.1155/2018/8351913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertin C, Pelletier AL, Vullierme MP, Bienvenu T, Rebours V, Hentic O, et al. Pancreas divisum is not a cause of pancreatitis by itself but acts as a partner of genetic mutations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:311–7. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarawagi R, Sundar S, Raghuvanshi S, Gupta SK, Jayaraman G. Common and uncommon anatomical variants of intrahepatic bile ducts in magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and its clinical implication. Pol J Radiol. 2016;81:250–5. doi: 10.12659/PJR.895827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tawab MA, Ali TF. Anatomic variations of intrahepatic bile ducts in the general adult Egyptian population: 3.0-T MR cholangiography and clinical importance. Egypt J Radiol and Nucl Med. 2012;43:111–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Srivastava VP, Agarwal S, Agarwal A, Sharan J. Managing bile duct injuries sustained during cholecystectomies. Int Surg J. 2017;5:148–52. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayashi TY, Gonoi W, Yoshikawa T, Hayashi N, Ohtomo K. Ansapancreatica as a predisposing factor for recurrent acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:8940–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i40.8940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonoi W, Akai H, Hagiwara K, Akahane M, Hayashi N, Maeda E, et al. Pancreas divisum as a predisposing factor for chronic and recurrent idiopathic pancreatitis: Initial in vivo survey. Gut. 2011;60:1103–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.230011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel HG, Cavanagh Y, Shaikh SN. Pancreaticoureteral fistula: A rare complication of chronic pancreatitis. N Am J Med Sci. 2016;8:163–6. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.179134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandrasegaran K, Tahir B, Barad U, Fogel E, Akisik F, Tirkes T, et al. The value of secretin-enhanced MRCP in patients with recurrent acute pancreatitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;208:315–21. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.16566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hyodo T, Kumano S, Kushihata F, Okada M, Hirata M, Tsuda T, et al. CT and MR cholangiography: Advantages and pitfalls in perioperative evaluation of biliary tree. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:887–96. doi: 10.1259/bjr/21209407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitami M, Takase K, Murakami G, Ko S, Tsuboi M, Saito H, et al. Types and frequencies of biliary tract variations associated with a major portal venous anomaly: Analysis with multi-detector row CT cholangiography. Radiol. 2006;238:156–66. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2381041783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Filippo M, Calabrese M, Quinto S, Rastelli A, Bertellini A, Martora R, et al. Congenital anomalies and variations of the bile and pancreatic ducts: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography findings, epidemiology and clinical significance. Radiol Med. 2008;113:841–59. doi: 10.1007/s11547-008-0298-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abueldahab M, Ali T. Anatomic variations of intrahepatic bile ducts in the general adult Egyptian population: 3.0-T MR cholangiography and clinical importance. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med. 2012;43:111–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bageacu S, Abdelaal A, Ficarelli S, ElMeteini M, Boillot O. Anatomy of the right liver lobe: A surgical analysis in 124 consecutive living donors. Clin Transplant. 2011;25:E447–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2011.01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

MRCP showing type A1 variation. The arrow indicates the union of RASD and RPSD. The symbol ‘star’ indicates the right lateral insertion of the cystic duct

MRCP showing type A2 variation. The figure shows the union of RASD, RPSD, and LHD forming a trifurcation