Abstract

The genetic background of childhood body mass index (BMI), and the extent to which the well-known associations of childhood BMI with adult diseases are explained by shared genetic factors, are largely unknown. We performed a genome-wide association study meta-analysis of BMI in 61,111 children aged between 2 and 10 years. Twenty-five independent loci reached genome-wide significance in the combined discovery and replication analyses. Two of these, located near NEDD4L and SLC45A3, have not previously been reported in relation to either childhood or adult BMI. Positive genetic correlations of childhood BMI with birth weight and adult BMI, waist-to-hip ratio, diastolic blood pressure and type 2 diabetes were detected (Rg ranging from 0.11 to 0.76, P-values <0.002). A negative genetic correlation of childhood BMI with age at menarche was observed. Our results suggest that the biological processes underlying childhood BMI largely, but not completely, overlap with those underlying adult BMI. The well-known observational associations of BMI in childhood with cardio-metabolic diseases in adulthood may reflect partial genetic overlap, but in light of previous evidence, it is also likely that they are explained through phenotypic continuity of BMI from childhood into adulthood.

Author summary

Although twin studies have shown that body mass index (BMI) is highly heritable, many common genetic variants involved in the development of BMI have not yet been identified, especially in children. We studied associations of more than 40 million genetic variants with childhood BMI in 61,111 children aged between 2 and 10 years. We identified 25 genetic variants that were associated with childhood BMI. Two of these have not been implicated for BMI previously, located close to the genes NEDD4L and SLC45A3. We also show that the genetic background of childhood BMI overlaps with that of birth weight, adult BMI, waist-to-hip-ratio, diastolic blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and age at menarche. Our results suggest that the biological processes underlying childhood BMI largely overlap with those underlying adult BMI. However, the overlap is not complete. Additionally, the genetic backgrounds of childhood BMI and other cardio-metabolic phenotypes are overlapping. This may mean that the associations of childhood BMI and later cardio-metabolic outcomes are partially explained by shared genetics, but it could also be explained by the strong association of childhood BMI with adult BMI.

Introduction

Childhood obesity is a major public health problem with impact on health in both the short and the long term [1]. Besides the well-established lifestyle and behavioral factors, genetics influence the risk of obesity, with reported heritability estimates from twin studies for body mass index (BMI) ranging from 40 to 70% [2,3]. An estimated 17 to 27% seems to be explained by common variants [4–6]. Large genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified 941 loci associated with adult BMI, accounting for 5% of the phenotypic variation [7]. Less is known about the genetic background of childhood BMI. A previous GWAS of BMI among 35,668 children identified 15 associated loci, accounting for 2% of the phenotypic variance [8]. Of these loci, 12 were also associated with adult BMI [9,10]. The remaining 3 identified genetic loci, specifically associated with childhood BMI, suggest possible age-specific differences between the two stages of life or could indicate stronger effects for these genetic loci in childhood BMI than in adult BMI [11–13]. Thus far, most common variants explaining the genetic variability of childhood BMI remain undetected. It is well known that obesity in early-life tends to track into later life [14]. Furthermore, childhood obesity has been associated with a lower age at menarche and with non-communicable diseases in later life, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes, neurodegenerative disease and asthma [15–19]. Findings from recent studies suggest a shared genetic background for BMI in childhood and adulthood [8,20,21]. To which extent the associations of childhood BMI with common adult diseases are genetically explained, has not been explored in detail.

We aimed to study the genetic background of childhood BMI by performing a two-stage GWAS meta-analysis consisting of 41 studies with a total sample size of 61,111 children of European ancestry. We also examined the genetic correlations of childhood BMI with anthropometric, cardio-metabolic, respiratory, neurocognitive and endocrinological traits in adults, using GWAS summary statistics from various consortia.

Results

Identification of genome-wide significant loci for childhood BMI

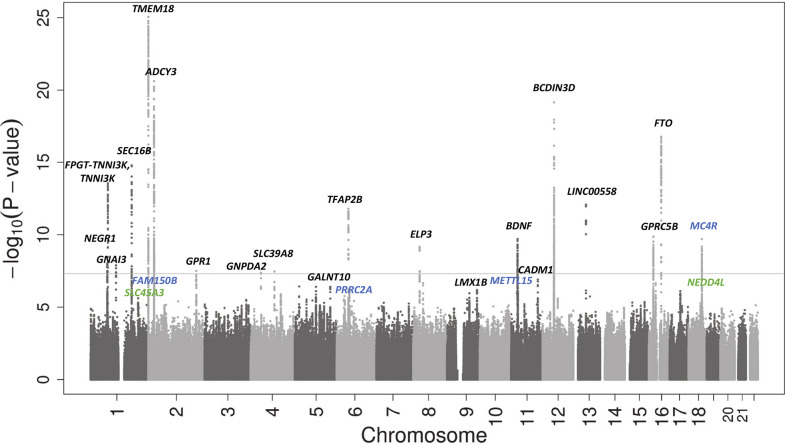

Sex- and age-adjusted Standard Deviation Scores (SDS) were created for BMI at the latest time point (oldest age, if multiple measurements were available) between 2 and 10 years using the same software and external reference across all studies (LMS growth; Pan H, Cole TJ, 2012; http://www.healthforallchildren.co.uk). Individual study characteristics are shown in S1 Table. The discovery meta-analysis included data from 26 studies (Ndiscovery = 39,620) with data imputed to the 1000 Genomes Project or The Haplotype Reference Consortium (HRC). We performed a fixed-effects inverse variance-weighted meta-analysis and performed conditional analyses based on summary-level statistics and Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) estimation between SNPs in Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis (GCTA) to select independently associated SNPs at each locus on the basis of conditional P-values [22]. Seventeen independent SNPs reached genome-wide significance (P-values <5 × 10−8) and thirty SNPs showed suggestive association with childhood BMI (P-values >5 × 10−8 and <5 × 10−6). A Manhattan plot of the discovery meta-analysis is shown in Fig 1. No evidence of inflation due to population stratification or cryptic relatedness or other confounders was observed (genomic inflation factor (lambda) = 1.05; LD-score regression intercept = 1.0) (S1 Fig) [23]. All 47 independent SNPs identified in the discovery meta-analysis were taken forward for analysis in 15 replication cohorts (Nreplication = 21,491) and results of the two stages were then combined. Results of the discovery, replication and combined meta-analyses are shown in Table 1 and S2 Table and S3 Table. Results of the discovery analysis for SNPs with P-values <5 × 10−6 are shown in S4 Table. As the replication stage might lack power to replicate SNPs from the discovery analysis, we consider the joint analysis as the primary analysis.

Fig 1. Manhattan plot of results of the discovery meta-analysis of 26 single study GWAS.

On the x-axis the chromosomes are shown. On the y-axis the–log 10 of the P-value is shown. Novel SNPs are shown in green. Independent SNPs are shown in blue. Known SNPs are shown in black. The genome wide significance cutoff of 5 × 10−8 is represented by the grey dotted line.

Table 1. Results of the discovery, replication and combined analyses for the 47 loci with P-values <5 x 10−6 in the discovery phase.

| SNP | CHR | Position | Nearest gene | EA/non_EA | P-value discovery | P-value replication | EAFa | Beta combined | SE combined | P-value combined |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs11676272b,c | 2 | 25141538 | ADCY3 | G/A | 2.37 x 10−21 | 1.88 x 10−10 | 0.46 | 0.071 | 0.006 | 3.79 x 10−30 |

| rs7138803b,c | 12 | 50247468 | BCDIN3D | A/G | 7.12 x 10−20 | 7.39 x 10−12 | 0.37 | 0.072 | 0.006 | 4.23 x 10−30 |

| rs939584b,c,d | 2 | 621558 | TMEM18 | T/C | 8.85 x10-26 | 2.52 x 10−6 | 0.83 | 0.092 | 0.008 | 3.73 x 10−29 |

| rs17817449b,c | 16 | 53813367 | FTO | G/T | 1.69 x 10−17 | 3.21 x 10−11 | 0.40 | 0.069 | 0.006 | 2.98 x 10−27 |

| rs12042908b,c | 1 | 74997762 | FPGT-TNNI3K, TNNI3K | A/G | 2.77 x 10−14 | 2.01 x 10−12 | 0.46 | 0.064 | 0.006 | 6.37 x 10−25 |

| rs543874b,c | 1 | 177889480 | SEC16B | G/A | 1.61 x 10−15 | 6.96 x 10−8 | 0.19 | 0.075 | 0.008 | 6.02 x 10−22 |

| rs56133711b | 11 | 27723334 | BDNF | A/G | 2.00 x 10−10 | 3.69 x 10−6 | 0.24 | 0.056 | 0.007 | 3.75 x 10−15 |

| rs2076308b,c | 6 | 50791640 | TFAP2B | C/G | 1.59 x 10−12 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.058 | 0.008 | 3.07 x 10−13 |

| rs4477562b,c,e | 13 | 54104968 | LINC00558 | T/C | 8.29 x 10−13 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.065 | 0.009 | 5.81 x 10−13 |

| rs571312b,c | 18 | 57839769 | MC4R | A/C | 2.00 x 10−10 | 4.84 x 10−4 | 0.23 | 0.052 | 0.007 | 8.80 x 10−13 |

| rs12641981b,c | 4 | 45179883 | GNPDA2 | T/C | 4.19 x 10−8 | 7.12 x 10−6 | 0.44 | 0.045 | 0.006 | 1.29 x 10−12 |

| rs62107261f | 2 | 422144 | FAM150B | T/C | 3.17 x 10−7 | 6.64 x 10−6 | 0.95 | 0.121 | 0.018 | 9.93 x 10−12 |

| rs114285994b | 16 | 19935763 | GPRC5B | G/A | 1.41 x 10−10 | 5.98 x 10−3 | 0.87 | 0.063 | 0.009 | 1.11 x 10−11 |

| rs144376234b,c | 1 | 110114504 | GNAI3 | T/C | 1.35 x 10−8 | 2.21 x 10−3 | 0.04 | 0.111 | 0.017 | 1.38 x 10−10 |

| rs1094647 | 1 | 205655378 | SLC45A3 | G/A | 2.46 x 10−6 | 7.45 x 10−5 | 0.55 | 0.038 | 0.006 | 7.20 x 10−10 |

| rs76227980f | 18 | 58036384 | MC4R | C/T | 1.71 x 10−6 | 1.19 x 10−4 | 0.98 | 0.140 | 0.023 | 8.68 x 10−10 |

| rs13107325b | 4 | 103188709 | SLC39A8 | T/C | 3.51 x 10−8 | 4.84 x 10−3 | 0.07 | 0.082 | 0.014 | 1.38 x 10−9 |

| rs62500888c | 8 | 28061823 | ELP3 | A/G | 6.91 x 10−10 | 0.09 | 0.57 | 0.037 | 0.006 | 1.81 x 10−9 |

| rs114670539c | 2 | 207064335 | GPR1 | T/C | 3.16 x 10−8 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.088 | 0.015 | 1.92 x 10−9 |

| rs61765651b | 1 | 72754314 | NEGR1 | C/T | 9.50 x 10−9 | 0.03 | 0.83 | 0.047 | 0.008 | 4.99 x 10−9 |

| rs7719067b | 5 | 153538241 | GALNT10 | A/G | 3.96 x 10−7 | 4.36 x 10−3 | 0.43 | 0.036 | 0.006 | 6.54 x 10−9 |

| rs11030391f | 11 | 28644626 | METTL15 | A/G | 4.73 x 10−7 | 6.49 x 10−3 | 0.63 | 0.036 | 0.006 | 1.51 x 10−8 |

| rs184566112 | 18 | 55943926 | NEDD4L | A/T | 4.40 x 10−6 | 1.24 x 10−3 | 0.84 | 0.057 | 0.011 | 4.24 x 10−8 |

| rs116664060 | 6 | 31592524 | PRRC2A | C/G | 3.03 x 10−6 | 3.28 x 10−3 | 0.18 | 0.049 | 0.009 | 4.63 x 10−8 |

| rs11215427c | 11 | 115093438 | CADM1 | G/C | 1.25 x 10−7 | 0.05 | 0.74 | 0.039 | 0.007 | 4.64 x 10−8 |

| rs1336980c | 9 | 129377855 | LMX1B | C/G | 6.61 x 10−7 | 0.03 | 0.36 | 0.033 | 0.006 | 1.17 x 10−7 |

| rs146823532f | 1 | 74979126 | FPGT-TNNI3K, TNNI3K | A/G | 4.09 x 10−7 | 0.03 | 0.97 | 0.114 | 0.022 | 1.33 x 10−7 |

| rs79386556 | 13 | 71229046 | LINC00348 | A/G | 1.84 x 10−6 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.095 | 0.019 | 4.83 x 10−7 |

| rs9942489 | 6 | 35323709 | PPARD | A/T | 3.62 x 10−6 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.081 | 0.016 | 5.56 x 10−7 |

| rs17086809 | 9 | 86708695 | RMI1 | C/T | 3.06 x 10−6 | 0.05 | 0.33 | 0.038 | 0.007 | 9.30 x 10−7 |

| rs80332495 | 5 | 19191677 | CDH18 | A/G | 3.78 x 10−7 | 0.26 | 0.94 | 0.090 | 0.019 | 1.14 x 10−6 |

| rs4594227 | 15 | 84497207 | ADAMTSL3 | A/G | 4.46 x 10−6 | 0.07 | 0.56 | 0.030 | 0.006 | 1.75 x 10−6 |

| rs2457463 | 10 | 70315687 | TET1 | G/T | 1.79x 10−7 | 0.43 | 0.04 | 0.159 | 0.034 | 2.69 x 10−6 |

| rs11865086b | 16 | 30130493 | MAPK3 | C/A | 2.23 x 10−7 | 0.47 | 0.53 | 0.029 | 0.006 | 3.31 x 10−6 |

| rs1565356 | 6 | 34046065 | GRM4 | C/A | 1.76 x 10−6 | 0.25 | 0.92 | 0.057 | 0.012 | 4.01 x 10−6 |

| rs2952863b | 4 | 130759647 | C4orf33 | T/G | 3.10 x 10−6 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.031 | 0.007 | 4.27 x 10−6 |

| rs2358954 | 12 | 66379504 | HMGA2 | T/G | 3.07 x 10−6 | 0.17 | 0.68 | 0.031 | 0.007 | 4.77 x 10−6 |

| rs7652876 | 3 | 179831733 | PEX5L | A/C | 3.22 x 10−6 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.033 | 0.007 | 6.93 x 10−6 |

| rs4923207 | 11 | 24757325 | LUZP2 | T/G | 1.07 x 10−6 | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.040 | 0.009 | 7.05 x 10−6 |

| rs7757288 | 6 | 55205502 | GFRAL | G/A | 6.64 x 10−7 | 0.47 | 0.39 | 0.028 | 0.006 | 1.03 x 10−5 |

| rs6876477 | 5 | 50878621 | ISL1 | A/T | 3.03 x 10−6 | 0.35 | 0.76 | 0.032 | 0.007 | 1.31 x 10−5 |

| rs28599560 | 5 | 91791853 | FLJ42709 | A/G | 3.99 x 10−7 | 0.85 | 0.61 | 0.027 | 0.006 | 3.48 x 10−5 |

| rs117281273 | 8 | 42981400 | SGK196 | C/G | 2.17 x 10−7 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.081 | 0.020 | 3.48 x 10−5 |

| rs9695734 | 9 | 96407983 | PHF2 | C/T | 1.12 x 10−6 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.035 | 0.009 | 4.99 x 10−5 |

| rs72833479 | 17 | 45960449 | SP2 | A/G | 7.96 x 10−7 | 0.99 | 0.25 | 0.029 | 0.007 | 6.54 x 10−5 |

| rs142367753 | 2 | 128938956 | UGGT1 | C/G | 4.03 x 10−6 | 0.24 | 0.98 | 0.088 | 0.027 | 1.34 x 10−3 |

| rs6896578 | 5 | 76423090 | ZBED3-AS1 | C/T | 3.52 x 10−6 | 0.17 | 0.84 | 0.025 | 0.009 | 4.1 x 10−3 |

CHR, chromosome; EA, effect allele; EAF, effect allele frequency; SE, standard error.

Bolded P-values indicate genome-wide significance in the combined analysis.

Detailed information on beta and SE of the discovery and replication stage separately can be found in S2 Table

a From combined analysis

b Locus previously reported for adult BMI

c Locus previously reported for childhood BMI

d Locus previously reported for adult body fat

e Locus previously reported for childhood obesity

f Independent SNP at the same locus selected by conditional analysis

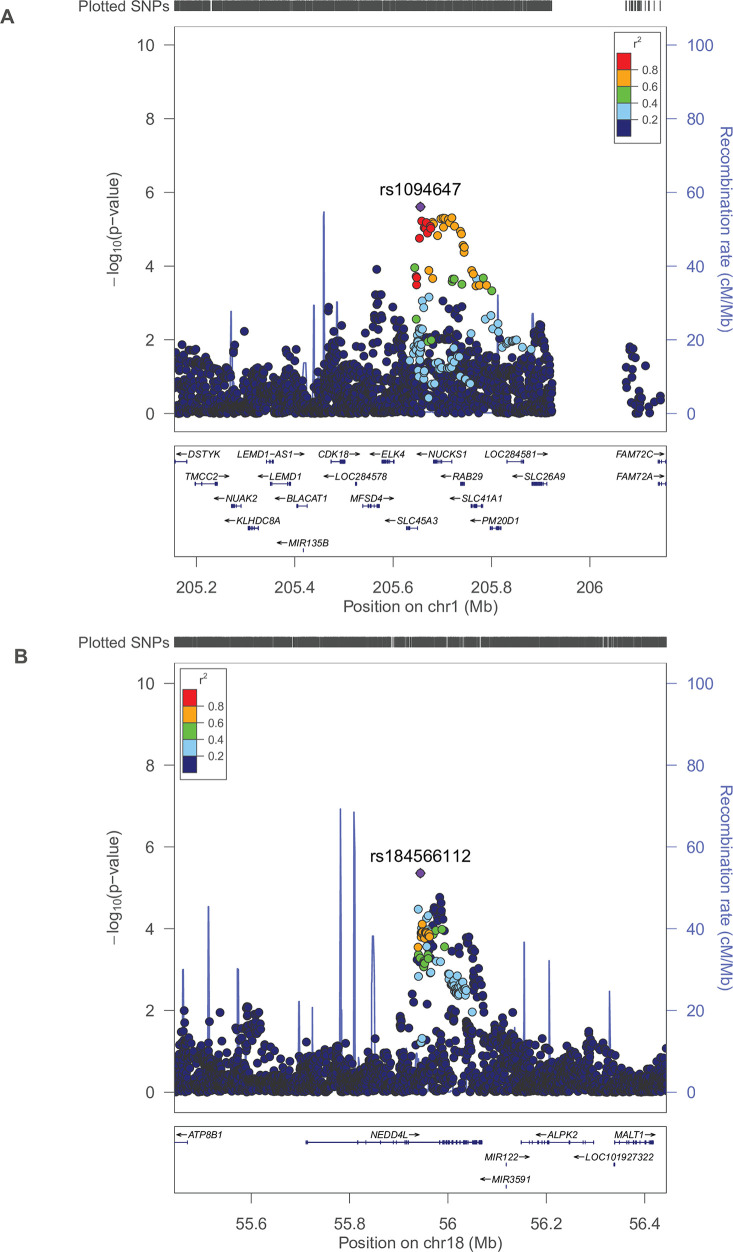

In total, 25 loci achieved genome-wide significance in the combined meta-analysis. We defined a SNP as representing a known BMI-locus if it was within 500 kb of and in LD (r2 ≥ 0.2) with a previously reported BMI-associated signal. Of the 25 SNPs, two were novel and had not been previously associated with BMI in either adults or children: rs1094647 near SLC45A3 and rs184566112 near NEDD4L. Per additional risk allele (G, allele frequency = 0.55) of rs1094647 (SLC45A3), childhood BMI increased by 0.04 SDS (Standard Error (SE) = 0.01, P-value = 7.20 × 10−10), equal to 0.09 kg/m2. Per additional risk allele (A, allele frequency = 0.84) of rs184566112 (NEDD4L), childhood BMI increased by 0.06 SDS (SE = 0.01; P-value = 4.24 × 10−8), equal to 0.11 kg/m2. Regional plots of the 2 novel SNPs are shown in Fig 2.

Fig 2. Locus zoom plots of the 2 novel SNPs Regional association plot of the 2 novel SNPs in the 26 childhood BMI discovery studies.

SNPs are plotted with their P-values (as–log10; left y-axis) as a function of genomic position (x-axis). Estimated recombination rates (right y-axis) taken from 1000 Genomes, March 2012 release are plotted to reflect the local LD-structure around the top associated SNP (indicated with purple color) and the correlated proxies (indicated in colors). A. rs1094647 B. rs184566112.

Despite the fact that these novel SNPs were not associated with either childhood or adult BMI previously, they have been reported to be associated with other anthropometric phenotypes. Rs1094647 (SLC45A3) has been associated with both height and whole-body fat-free mass in adulthood [24–26]. Additionally, rs708724, which is in high LD with rs1094647 (r2 = 0.70) was associated with adult weight [24–26]. Rs184566112 (NEDD4L) is located in the same region as rs6567160 (distance = 448 kb, r2 <0.2), previously associated with adult body fat [27]. In the current study, we did not observe evidence for association between rs184566112 (NEDD4L, effect allele = G, allele frequency = 0.84) and body fat percentage measured by Dual energy X-ray Absorptiometry (age range 24 to 120 months) in 2,698 children from 4 cohorts (0.03 SDS (SE = 0.04, P-value = 0.51)). Individual study characteristics of studies with data on body fat percentage are shown in S5 Table. No evidence of association with childhood obesity was found for the two novel SNPs (P-values >0.11) [28].

We additionally identified 2 independent SNPs (METTL15 and PRRC2A) within 500 kb of previously reported SNPs associated with adult BMI, but only in weak LD with prior reported signals (r2 <0.2). Similarly, we found 2 independent SNPs in regions that are known for both childhood and adult BMI (FAM150B and MC4R) [7,8,10]. Regional plots of the 4 independent SNPs at known loci are shown in S2 Fig. Of the remaining 19 SNPs, 6 mapped to loci previously associated with adult BMI (BDNF, GPRC5B, SLC39A8, NEGR1, GALNT10, and CADM1), 2 mapped to loci previously associated with childhood BMI only (ELP3 and GPR1) and 11 SNPs mapped to loci known to be associated with both adult and childhood BMI (ADCY3, BCDIN3D, TMEM18, FTO, FPGT-TNNI3K/TNNI3K, SEC16B, TFAP2B, LINC00558, MC4R, GNPDA2, and GNAI3) [7,8,10].

Overall, there was low heterogeneity between studies for the 25 SNPs, except for FTO (S2 Table) [29]. The broad age range included in the discovery meta-analysis of this study may conceal age-specific effects. Therefore, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding studies of children aged <6 years (remaining Nsensitvity analysis = 55,354), which showed similar results (S6 Table) [30]. Additionally, we ran a sensitivity analysis excluding case-control studies and one excluding studies with a sample size <n = 500, showing similar results (S7 Table).

Functional characterization

We used several strategies to gain insight into the functional characterization of the 25 SNPs leading the association signals with childhood BMI. A summary of relevant information from all strategies can be found in S8 Table.

First, we examined gene expression profiles of the nearest genes to the 25 SNPs from the combined meta-analysis with GTEx v7 in 53 tissues, using the tool FUMA [3,31]. We found differential expression of the 25 nearest genes in brain and salivary gland. In a second analysis of gene expression profiles in GTEx, we considered all genes in a region of 500 kb to either side of the 25 SNPs. Using this strategy, we additionally found differential expression in liver, heart, kidney, pancreas, muscle, skin and adipose tissue [31].

Second, we assessed whether the 25 SNPs were associated with gene expression in whole adipose tissue, isolated adipocytes, and isolated stroma-vascular cells from the Leipzig Adipose Tissue Childhood Cohort [32]. Full results can be found in S9 Table. We observed differential gene expression associated with multiple SNPs. Rs1094647 (nearest gene: SLC45A3) was associated with gene expression of PM20D1 (PFDR <0.05) in whole adipose tissue. We additionally found associations of rs114285994 (nearest gene: GPRC5B) with expression of C16orf88 in isolated adipocytes. Rs115181845, which is in moderate LD (r2 = 0.47) with rs144376234 (nearest gene: GNAI3), was associated with expression of GSTM1 and GSTM2 in whole adipose tissue, isolated adipocytes and isolated stroma-vascular cells (S8 Table and S9 Table). No associations with gene expression were observed for any of the other 22 SNPs.

Third, we used Bayesian colocalization analysis to examine evidence for colocalization between GWAs and eQTL signals and to identify additional candidate genes for the 25 SNPs (GTEx v7). Briefly, GWAS summary statistics were extracted for each eQTL for all SNPs that were present in the meta-analysis and that were in common to both GWAS and eQTL studies. In most pairs, no evidence for association was found with either trait. To define colocalization we used restriction to pairs of childhood BMI and eQTL signals with a high posterior probability for colocalization (See Methods and Materials for details) [33]. We found significant colocalizations at 6 loci (ADCY3, DNAJC27-AS1, CENPO, ADAM23, LIN7C, TFAP2B) across a range of tissues (S8 Table and S10A and S10B Table) [8].

Fourth, to explore biological processes, we used DAVID, with the 25 nearest genes as input, using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database [34,35]. Pathway analysis revealed one enriched biological process, cAMP signaling (P-value = 0.03).

Fifth, we performed a look-up in mouse-knockout data of the 25 nearest genes and, additionally, the genes that were indicated by colocalization and gene expression analysis. Mice in which NEDD4L was knocked out displayed neuronal abnormalities [36]. No related phenotypes were shown for SLC45A3 or any of the 4 independent loci (METTL1, PRRC2A, FAM150B, and MC4R). Of the 19 known loci, ADCY3 showed an association with increased total body fat in female heterozygous knockout mice, whereas NEGR1 was associated with decreased lean body mass in male and female homozygous knockout mice (S8 Table). Full results can be found in S8 Table.

Sixth, among the 25 top SNPs, combined annotation-dependent depletion (CADD) scores >12.37, indicating potential pathogenicity of a SNP, were observed for rs13107325 (SLC39A8), rs56133711 (BDNF) and rs17817449 (FTO) (CADD scores of 34, 15.3 and 15.3, respectively) (S8 Table) [3,37].

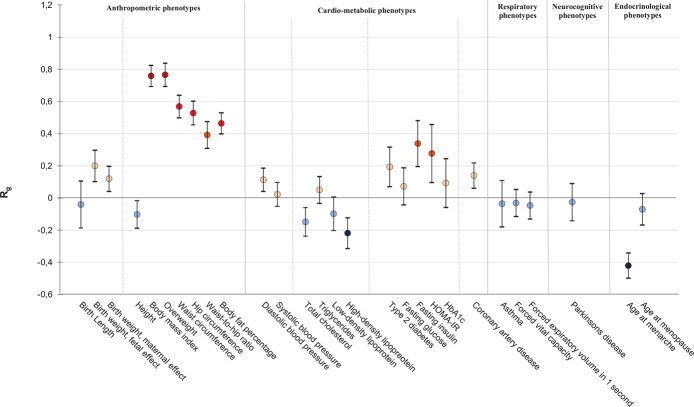

Genetic correlations of childhood BMI with adult phenotypes

First, to estimate the SNP heritability and the genetic correlations between childhood BMI and other traits from external GWAS meta-analysis data, we used LD-score regression [20]. SNP heritability was 0.23. There were positive genetic correlations of childhood BMI with several anthropometric and cardio-metabolic traits, including adult BMI (Rg = 0.76, P-value = 1.45 × 10−112), waist-to-hip ratio (Rg = 0.39, P-value = 1.57 × 10−20), body fat percentage (Rg = 0.46, P-value = 7.99 × 10−44), diastolic blood pressure (Rg = 0.11, P-value = 0.002), type 2 diabetes (Rg = 0.19, P-value = 0.002), and coronary artery disease (Rg = 0.14, P-value = 0.001) (Fig 3 and S11 Table). For birth weight, there were positive genetic correlations with childhood BMI, both when using fetal genetic effects on birth weight and when using maternal genetic effects on birth weight (Rg = 0.20, P-value = 3.19 x 10−5 and Rg = 0.12, P-value = 0.002 for fetal and maternal effects, respectively). Negative genetic correlations were observed between childhood BMI and total cholesterol (Rg = -0.15, P-value = 0.001), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) (Rg = -0.22, P-value = 8.65 x 10−6), and age at menarche (Rg = -0.42, P-value = 1.03 x 10−32). We did not find genetic correlations with any of the respiratory and neurocognitive phenotypes. Genetic correlations of childhood BMI with a selection of phenotypes that show evidence of association in observational studies are shown in Fig 3. Full results can be found in S11 Table.

Fig 3. Genome-wide genetic correlations between childhood BMI and adult traits and diseases.

On the x-axis the traits and diseases are shown. On the y-axis the genetic correlations (Rg) and corresponding standard errors, indicated by error bars, between childhood BMI and each trait were shown, estimated by LD score regression. The genetic correlation estimates (Rg) are colored according to their intensity and direction. Red indicates positive correlation, blue indicates negative correlation. References can be found in S11 Table.

Second, we did a look-up of the 25 SNPs in the adult BMI GWAS [7]. In total, 12 SNPs and 8 proxy SNPs (r2 ≥ 0.87) were available in the adult BMI study comprising ~700,000 individuals. No information was available on five loci, FAM150B, GPR1, NEGR1, NEDD4L, and PRRC2A. The directions of effect of all 20 SNPs were the same in adults as in children. Of these, 18 were genome-wide significantly associated with adult BMI (P-value <5 x 10−8) and the other 2 SNPs, SLC45A3 and METTL15, showed suggestive evidence of association (P-values < 2.1 × 10−6) (S12 Table). Effect sizes of these 20 SNPs for adult BMI were highly correlated with those for childhood BMI (r2 = 0.86).

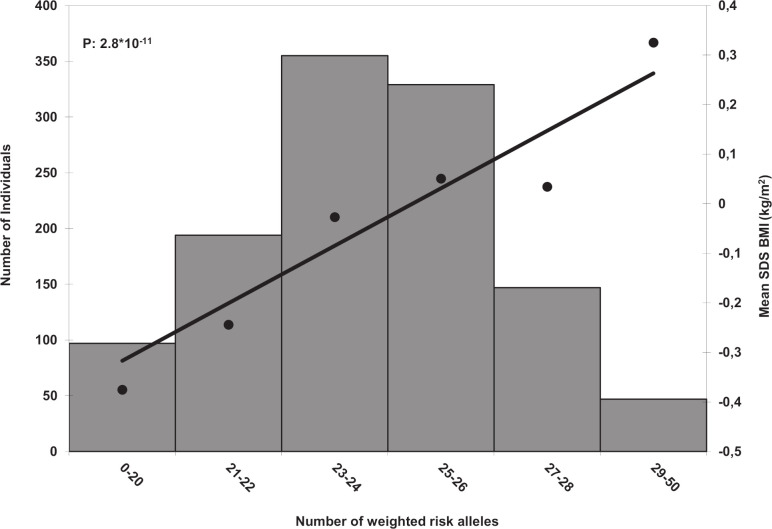

Third, we calculated a combined childhood BMI genetic risk score (GRS) of the 25 genome-wide significant SNPs, summing the number of BMI-increasing alleles weighted by their effect sizes from the combined meta-analysis. The GRS was associated with childhood BMI (P-value = 2.84 × 10−11) in 1,169 children from the Tracking Adolescents’ Individual Lives Survey (TRAILS) Cohort, aged 7 years, one of the largest replication cohorts (Fig 4). For each additional average risk allele in the GRS, childhood BMI increased by 0.06 SDS (SE = 0.009). This GRS explained 3.6% of the variance in childhood BMI. When calculating the risk score for the TRAILS cohort, effect estimates from the combined meta-analysis were used after excluding TRAILS from the meta-analysis. We additionally tested the GRS for association with adult BMI in the three sub-cohorts of the Rotterdam Study [38] (RS-I-1; n = 5,957, RS-II-1; n = 2,147 and RS-III-1; n = 2,998). We found the GRS to be associated with adult BMI in all study samples (P-values = 5.09 × 10−9, 0.02, and 1.49 × 10−10, respectively). Per additional average risk allele, adult BMI increased by 0.03 SDS (SE = 0.005), 0.02 SDS (SE = 0.009) and 0.04 SDS (SE = 0.007), explaining 0.6%, 0.2%, and 1.3% of the variance in adult BMI, respectively. No association was found of the GRS with birth weight and cardio-metabolic phenotypes, including insulin, triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein, HDL, total cholesterol, diastolic blood pressure and systolic blood pressure in 2,831 children aged 6 years from the Generation R Study if considering a Bonferroni corrected P-value of 0.00625 (S13 Table).

Fig 4. Associations of the weighted risk score with childhood BMI.

Along the x-axis, categories of the risk score are shown together with the mean SDS BMI on the y-axis on the right and a line representing the regression of the mean SDS childhood BMI values for each category of the risk score. Along the y-axis on the left a histogram represents the number of individuals in each risk-score category. P-value is based on the continuous risk score. Analysis was performed in the TRAILS cohort (N = 1,169).

Discussion

In this large GWAS meta-analysis of childhood BMI among >60,000 children aged 2–10 years, we identified 25 genome-wide significant loci. Two of these loci, rs1094647 near SLC45A3 and rs184566112 near NEDD4L had not been associated with BMI before. We observed moderate to strong genetic correlations of childhood BMI with several anthropometric, cardio-metabolic, and endocrinological traits in adulthood, suggesting a shared genetic background.

The closest genes to the two novel loci, SLC45A3 and NEDDL4, have not been strongly linked to obesity in previous studies and databases, indicating that functional studies are needed to identify possible biological pathways. SLC45A3, encoding the solute carrier family 45, member 3 protein, also known as prostate cancer-associated protein 6, has been related to prostate-specific antigen serum concentrations and prostate cancer [39–42]. NEDD4L, ubiquitin protein ligase Nedd4-like, known for its role in the regulation of ion channel internalization and turnover, is suggested to play a role in the regulation of respiratory, cardiovascular, renal, and neuronal functions [36,43–45]. The independent SNPs identified at loci known from previous studies on adult or childhood BMI may represent fully independent signals, although due to the low LD, these SNPs might still tag the same causal variant as the previously identified SNPs.

Since there is no strong previous evidence supporting the closest genes to the 25 SNPs as the causal genes, we took multiple approaches for further functional characterization. As many different tissues have been implicated to play a role in body composition we chose to include all available tissues in the gene expression analysis. Using GTEx, we found differential expression of the 25 nearest genes in brain. This may be of interest as appetite regulation might play a role in the development of obesity [46–48]. Gene expression data revealed an association between one of the novel SNPs, rs1094647 (nearest gene: SLC45A3), and expression of PM20D1 in whole adipose tissue. PM20D1, Peptidase M20 domain-containing 1, previously identified as a factor secreted by thermogenic adipose cells, is known for its association with insulin resistance, glucose intolerance and enhanced defense of body temperature in cold when knocked out in mice. Furthermore, increased circulating PM20D1, together with adeno-associated virus-mediated transduction, leads to a higher energy expenditure and reduced adiposity in mice [49,50]. We used colocalization analysis to further identify candidate causal genes. This did not identify specific potential causal genes for rs1094647 (SLC45A3) and rs184566112 (NEDD4L). However, we identified ADCY3, DNAJC27-AS1, CENPO, ADAM23, LIN7C, TFAP2B as candidate genes for known loci across different tissues, including tibial nerve tissue, tibial artery tissue and the skin. No candidate genes were detected in biologically more relevant tissues, including subcutaneous or visceral adipose tissue.

Information on rs184566112 near NEDD4L was available in 24 out of 26 discovery cohorts that primarily used 1000 Genomes phase 1 imputed data (N = 37,104), thus clearly surviving our pre-set filter of having information in at least 50% of the number of studies and at least 50% of the total sample size in the discovery analysis. However, it was available in only less than half of the replication studies, mainly using 1000 Genomes phase 3 or HRC imputed data (N = 5,518) as this SNP was not included in these more recent reference panels. No other SNPs in high LD were available as proxy for this SNP in the replication analysis. Therefore, this signal needs to be interpreted with caution. However, no heterogeneity of this SNP between the discovery stage studies (I2 = 0; P-value for heterogeneity = 0.98), a high imputation quality (weighted mean R2 = 0.89) and the known association of another locus in the same region with adult body fat percentage might lends credibility to this signal, although further work is needed to unravel the details [27]. Previous studies have shown that variants might have strong age-dependent effects across childhood [15,51]. We performed a sensitivity analyses excluding children aged <6 years, as the approximate age of the adiposity rebound [30]. However, no difference in main results with the full meta-analysis were observed.

Observational studies suggest that childhood obesity is not only related to several anthropometric and cardio-metabolic phenotypes in later life, such as type 2 diabetes, but also to respiratory and neurocognitive traits, including asthma and Parkinson’s disease and to a lower age at menarche [14–18,52–58]. In observational studies, effect estimates may be influenced by confounding factors and reverse causation, potentially evoking spurious associations [59,60]. Genetic studies can provide more insight into the etiology of complex diseases. We observed a strong positive genetic correlation of childhood BMI with adult BMI. This is in line with previous studies [8,20,21]. We additionally observed positive genetic correlations between childhood BMI and several cardio-metabolic phenotypes in later life, including waist-to-hip ratio, diastolic blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and coronary artery disease. Negative genetic correlations were found between childhood BMI and HDL-C and age at menarche. These results may suggest that the associations reported in observational studies are partly explained by genetic factors [15–17,58,61]. However, there is also evidence from previous work to support that the associations of childhood BMI with cardiometabolic phenotypes in adulthood are explained by the continuity of a high BMI from childhood until later ages, rather than by an independent effect of childhood BMI on adult cardiometabolic phenotypes [15,62]. From our data, we are not able to distinguish this. Childhood BMI was not genetically correlated with asthma and Parkinson’s disease. This may indicate that the observational associations between childhood BMI and these phenotypes are not strongly explained by shared genetics [18,56,57,63].

The GRS combining the 25 top SNPs was not associated with cardiometabolic phenotypes in children aged 6 years. This may indicate that there is no shared genetic basis between childhood BMI and these phenotypes in childhood. However, the GRS analyses in children had a much lower sample size than the LD score regression analyses in adults and phenotypic variation in these phenotypes is more limited in children, leading to a much lower power to detect associations in these analyses. Additionally, the GRS was composed of the top-associated SNPs, whereas the genetic correlation estimated from the LDSR examined variation genome-wide.

We observed a SNP heritability of 0.23 which is consistent with previous findings [4–6].

Secular trends in obesity across populations and age groups can influence the heritability estimates across distinct population settings, requiring careful interpretation. This contention is also relevant for the interpretation of the genetic correlations estimated between traits. Environmental influences like those giving rise to the increase obesity in the last decades, can influence heritability estimates and hence, the power to identify significant genetic correlations. Before concluding unequivocal absence of some degree of “shared heritability” between childhood BMI and some of the adult traits, genetic correlations should be interpreted in the context of power limitations. Increasingly larger environmental influences along the life-course can result in lower heritability, but recent work has also shown that the increase in phenotypic variance accompanying increasing prevalence of obesity occurs alongside an increase in genetic variance [64–67]. This results in relatively stable (broad sense) heritability estimates across measurement years, as recently shown by a large-scale meta-analysis of adult twin data.

The 25-SNP GRS was positively associated with both childhood and adult BMI, showing slightly larger effect estimates in children suggesting that these specific genetic variants affect BMI in both childhood and adulthood, but with stronger effects at younger ages. A recent study, using genome-wide polygenic scores of 2.1 million common variants, found that the overall effect of those variants on weight starts in early childhood and increases over time [4]. Two previous studies also describe specific genetic variants associated with BMI in infancy only, and overlapping patterns of genetic variants with those in adults emerging from childhood onwards. Three SNPs associated with infant BMI from these studies were not genome-wide significantly associated with childhood BMI in our data (P-values >0.02), which supports their infancy-specific effects [68,69].

Although many of the associated variants from the current study overlap between children and adults, the relative order of the signals differs. Additionally, SLC45A3, one of the novel loci did not show genome-wide association in adult data [7]. However, suggestive association of this locus with adult BMI was observed (P-value = 2.7 x 10−5). Overall, the effect estimates of the 25 SNPs in childhood were highly correlated with those in adulthood (r2 = 0.86). Taken together, evidence from the current and previous studies suggests that biological processes underlying BMI are similar from childhood onwards, but their relative influence may differ depending on the life stage.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we identified 25 loci for childhood BMI, together explaining 3.6% of the variance in childhood BMI. Two of these are novel and four represent independent SNPs at loci known to be associated with adult or childhood BMI. A strong positive genetic correlation of childhood BMI with adult BMI and related cardio-metabolic phenotypes was observed. Our results suggest that the biological processes underlying childhood BMI largely, but not completely, overlap with those underlying adult BMI. The well-known observational associations of BMI in childhood with cardio-metabolic diseases in adulthood may reflect partial genetic overlap, but in light of previous evidence, it is also likely that they are explained through phenotypic continuity of BMI from childhood into adulthood.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

All individual studies got approval by their medical ethics review committees. All participants gave written informed consent. Study-specific ethics statements are given in S1 Text.

Study design

We conducted a two-stage meta-analysis in children of European ancestry to identify genetic loci associated with childhood BMI. Sex- and age-adjusted standard deviation scores were created for BMI at the latest time point (oldest age, if multiple measurements were available) between 2 and 10 years using the same software and external reference across all studies (LMS growth; Pan H, Cole TJ, 2012; http://www.healthforallchildren.co.uk). In the case of twin pairs and siblings, only one of each twin or sibling pair was included, either randomly or based on genotyping or imputation quality.

In the discovery stage, we performed a meta-analysis of 26 studies (N = 39,620), including the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC, N = 6790), the Bone Mineral Density in Childhood Study (BMDCS, N = 543), BRain dEvelopment and Air polluTion ultrafine particles in scHool childrEn (BREATHE, N = 1633), the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP, N = 5488), the Copenhagen Prospective Studies on Asthma in Childhood 2000 (COPSAC2000, N = 327), the Copenhagen Prospective Studies on Asthma in Childhood 2010 (COPSAC2010, N = 571), the Danish National Birth Cohort- preterm birth study (DNBC-PTB, N = 1007), the French Young Study (French young, N = 304 cases and N = 144 controls), the Generation R Study (GenerationR, N = 2071), the Genetics of Overweight Young Adults (GOYA Male, N = 319), the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study (HBCS, N = 1575), the INfancia y Medio Ambiente [Environment and Childhood] Project, with two subcohorts that were entered into the meta-analysis seperately (INMA-Sabadell and Valencia subcohort, N = 650, and INMA-Menorca subcohort, N = 300), German Infant Study on the influence of Nutrition Intervention PLUS environmental and genetic influences on allergy development & Influence of life-style factors on the development of the immune system and allergies in East and West Germany (GINIplus&LISA, N = 1471), the Manchester Asthma and Allergy Study (MAAS, N = 784), the Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort (MoBa, N = 522), the Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 (NFBC 1966, N = 3949), the Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1986 (NFBC 1986, N = 1056), the Netherlands Twin Register (NTR, N = 1767), the Physical Activity and Nutrition in Children Study (PANIC, N = 374), The Danish Childhood Obesity Data and Biobank (TDCOB, N = 158 controls), the Raine Study (the Raine Study (Generation 2), N = 1458), the Special Turku Coronary Risk factor Intervention Project (STRIP, N = 551), the Young Finns Study (YFS, N = 1134), the TEENs of Attica: Genes and Environment (TEENAGE, N = 252), and the British 1958 Birth Cohort Study (1958BC-T1DGC, N = 2081 and 1958BC-WTCCC, N = 2341).

In the replication stage, we included 14 studies (n = 21,491), which did not have genome-wide association data available at the time of the discovery analysis: 888 additional children from the Danish National Birth Cohort- Goya offspring (N = 407 offspring from obese mothers, N = 481 offspring from randomly selected mothers), 294 additional children from the INfancia y Medio Ambiente [Environment and Childhood] (INMA) Project (INMA- Gipuzkoa subcohort, N = 314), 6,828 additional children from the Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort (MoBa, N = 6828), 753 additional children from TDCOB (N = 344 controls and N = 409 cases), the Amsterdam Born Children and their Development- Genetic Enrichment (ABCD, N = 1154), The European Childhood Obesity Project (CHOP Study, N = 369), the Family Atherosclerosis Monitoring In earLY life (FAMILY) study (the FAMILY study, N = 543), the Etude des Déterminants pré- et postnatals précoces du développement et de la santé de l'Enfant (EDEN) mother-child cohort (EDEN, N = 821), the Exeter Family Study of Childhood Health (EFSOCH, N = 542), the Leipzig Research Center for Civilization Diseases—Child study (LIFE-Child, N = 1318), the Prevention and Incidence of Asthma and Mite Allergy study (PIAMA, N = 1958), the Screening of older women for prevention of fracture Study (SCOOP, N = 685), the Småbørns Kost Og Trivsel study (SKOT1, N = 236), the Twin Early Development Study (TEDS, N = 3933), the Tracking Adolescents’ Individual Lives Survey cohort (TRAILS-population cohort, N = 1169). In the EDEN mother-child cohort, information was available about three SNPs only (rs7138803, rs13107325, and rs987237). Characteristics of discovery and replication studies can be found in S1 Table and S1 Text.

Study-level analyses

Genome-wide association analyses were first run in all discovery cohorts separately. Studies used high-density Illumina or Affymetrix SNP arrays, followed by imputation to the 1000 Genomes Project or HRC. Before imputation, studies applied study specific quality filters on sample and SNP call rate, minor allele frequency and Hardy–Weinberg disequilibrium (see S1 Table for details). Linear regression models assuming an additive genetic model were run in each study to assess the association of each SNP with BMI SDS, adjusting for principal components if this was deemed needed in the individual studies. As BMI SDS is age and sex specific, no further adjustments were made. Before the meta-analysis, we applied quality filters to each study, filtering out SNPs with a minor allele frequency (MAF) below 1% and SNPs with poor imputation quality (MACH r2_hat ≤0.3, IMPUTE proper_info ≤0.4 or info ≤0.4).

Meta-analysis

We performed fixed-effects inverse-variance weighted meta-analysis of all discovery samples using Metal [70]. Genomic control was applied to every study before the meta-analysis. Individual study lambdas before genomic control ranged from 0.993 to 1.036 (S1 Table). The lambda of the discovery meta-analysis is shown in S1 Fig. After the meta-analysis, we excluded SNPs for which information was available in less than 50% of the studies and less than 50% of the total sample size. We report I2 and p-value for heterogeneity for all findings.

The final dataset consisted of 8,228,795 autosomal SNPs. Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis (GCTA) was used to select the independent SNPs for each locus [22]. We performed conditional analyses based on summary-level statistics and LD estimation between SNPs from the Generation R Study as a reference sample to select independently associated SNPs based on conditional P-values [22]. Forty-seven genome-wide significant or suggestive loci (P-values <5 × 10−8 and <5 × 10−6, respectively) were taken forward for replication in 14 replication cohorts. Fixed-effects inverse variance meta-analysis was performed for these 47 SNPs combining the discovery samples and all replication samples, giving a combined analysis beta, standard error and P-value (Table 1). SNPs that reached genome-wide significance in the combined analysis were considered to be genome-wide significant.

Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations (FUMA)

To obtain predicted functional consequences for our 25 SNPs, we used SNP2FUNC in FUMA, a web-based platform to facilitate and visualize functional annotation of GWAS results (http://fuma.ctglab.nl) [3]. By matching chromosome, position, and reference and alternative alleles, combined annotation-dependent depletion (CADD) scores were annotated, indicating the deleteriousness of a SNP [37].

To annotate the nearest genes of the 25 SNPs in biological context, we used the GENE2FUNC option in FUMA, which provides hypergeometric tests of enrichment of a list of genes in 53 GTEx tissue-specific gene expression sets (GTEx v 7) [3,31]. We used GENE2FUNC for two sets of genes: 1. Nearest genes of 25 SNPs; 2. Genes located in a region of 500 kb to either side of the 25 SNPs.

Look-up of the 25 SNPs in expression data

We studied the associations of the 25 SNPs associated with childhood BMI with gene expression levels in adipose tissue samples from the Leipzig Adipose Tissue Childhood Cohort [32]. These associations were examined in the following tissues: whole adipose tissue, isolated adipocytes and isolated stroma-vascular cells using genome- wide expression analysis (Illumina HumanHT-12 v4 arrays). Gene expression raw data of all 47,231 probes was extracted by Illumina GenomeStudio without additional background correction. Data was further processed within R / Bioconductor. Expression values were log2-transformed and quantile-normalised [71,72]. Batch effects of expression BeadChips were corrected using an empirical Bayes method [73].Within pre-processing, gene-expression probes detected by Illumina GenomeStudio as expressed in less than 5% of the samples were excluded as well as probes still found to be significantly associated with batch effects after Bonferroni-correction. Furthermore, gene-expression probes with poor mapping on the human trancriptome [74] were also excluded. In summary, these filters resulted in 23354, 21258, and 22637 valid gene-expression probes from which 20672, 18956, and 20230 probes corresponded to 14455, 13518, and 14256 genes mapping to a unique position in the human genome (hg19) for whole adipose tissue, adipocytes, and stroma/vascular cells, respectively. Three criteria were used to remove samples of low quality: First, the number of detected gene-expression probes of a sample was required to be within ± 3 interquartile ranges (IQR) from the median. Second, the Mahalanobis distance of several quality characteristics of each sample had to be lower than median + 4 x IQR. Third, Euclidean distances of expression values as described [71] had to be lower than median + 4 x IQR. Overall, of the assayed samples, 2, 4, and 2 samples were excluded for quality reasons leaving 203, 63 and 69 unique individuals having also valid data for eQTL analysis for whole adipose tissue, adipocytes, and stroma/vascular cells, respectively. Associations between the genotype and gene expression of genes in cis (respective gene area +/- 1 Mb regarding transcription start and transcription end) were analyzed using a gene-dose based linear regression model adjusted for age and sex as implemented in MatrixEQTL [75]. Analysis of variants within one haplotype were done through analyses of linkage-disequilibrium using 1000 Genomes Phase 1 Version 3 and HapMap r28 hg19 CEU as references.

Colocalization analysis

We used Bayesian colocalization analysis to examine evidence for colocalization between childhood BMI and eQTL signals (GTEx v7).Colocalization analyses were conducted using the R package coloc, hht://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/coloc, as described previously [33]. Briefly, in each of the GTEx v7 tissues, all cis-eQTLs at FDR <5% were identified. For each eQTL, GWAS summary statistics were extracted for all SNPs that were present in >50% of the studies and >50% of the total sample size and that were in common to both GWAS and eQTL studies, within 1 MB of the transcription start site of the gene. For each such locus, colocalization analyses were done with default parameters, testing the following hypotheses [33]:

H0: No association with either trait;

H1: Association with childhood BMI only;

H2: Association with gene expression only;

H3: Association with childhood BMI and gene expression, two distinct causal variants;

H4: Association with childhood BMI and gene expression, one shared causal variant.

Support for each hypothesis was quantified in terms of posterior probabilities, defined at SNP level and indicated by PP0, PP1, PP2, PP3 or PP4, corresponding to the five hypotheses and measuring how likely these hypotheses were. S10B Table shows the above-mentioned posterior probabilities for all pairs. In most pairs, no evidence for association was found with either trait. In case association was observed, it was mostly with a single trait. To define colocalization we used restriction to pairs of childhood BMI and eQTL signals with a high posterior probability for colocalization, indicated by a PP4/(PP3+PP4) >0.9 (S10A Table).

DAVID

To explore biological processes, we used DAVID, with the 25 nearest genes as input, using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database [34,35].

Linkage-disequilibrium score regression

The use of LD score regression to estimate genetic correlations between two phenotypes has been described in detail previously [20]. Briefly, LD score is a measure of how much a genetic variation is tagged by each variant. A high LD score indicates that a variant is in high LD with many nearby polymorphisms. Variants with high LD scores are more likely to contain true signals and have a higher chance of overlap with genuine signals between GWAS. To estimate LD scores, summary statistics from GWAS meta-analysis are used to calculate the cross-product of test statistics per SNP, which is regressed on the LD score. The slope of the regression is a function of the genetic covariance between traits [20]:

where Ni is the sample size of study i, ρg is the genetic covariance, M is the number of SNPs in the reference panel with a MAF between 5% and 50%, lj is the LD score for SNP j, Ns quantifies the number of individuals that overlap both studies, and ρ is the phenotypic correlation amongst the Ns of overlapping samples. A sample overlap or cryptic relatedness between samples will only affect the intercept from the regression but not the slope. Estimates of genetic covariance will therefore not be biased by overlapping samples. Similarly, in case of population stratification, the intercept will be affected but it will have only minimal impact on the slope since population stratification does not correlate with LD between variants.

Because of the correlation between the imputation quality and LD score, imputation quality is a confounder for LD score regression. Therefore, SNPs were excluded for the following reasons: MAF <0.01 and INFO ≤0.9. The filtered GWAS results were uploaded on http://ldsc.broadinstitute.org/ldhub/, a website with many GWAS meta-analyses available on which LD score regression has been implemented by the developers of the LD score regression method. In case multiple GWAS meta-analyses were available for the same phenotype, the genetic correlation with childhood BMI was estimated using the most recent meta-analysis. Genetic correlations are shown in Fig 2 and S11 Table.

Genetic risk score and percentage of variance explained

We combined the 25 genome-wide significant SNPs from the combined meta-analysis into a GRS by summing up the number of BMI SDS-increasing alleles, weighted by the effect sizes from the combined meta-analysis. The GRS was rescaled to a range from 0 to 50, which is the maximum number of BMI SDS increasing alleles and rounded to the nearest integer. Linear regression analysis was used to examine the associations of the risk score with childhood and adult BMI. For these analyses data from the TRAILS cohort (N = 1169), one of the largest replication cohorts, and data from the Rotterdam Study (RS-I-1; n = 5,957, RS-II-1; n = 2,147 and RS-III-1; n = 2,998) were used. Additionally, linear regression analysis was used to examine the associations of the GRS with birth weight and childhood metabolic phenotypes in Generation R in which detailed information on these phenotypes was available. When calculating the risk score for the TRAILS cohort and Generation R, effect estimates from the combined meta-analysis were used after excluding TRAILS and Generation R, respectively, from the meta-analysis. The variance explained was estimated by the adjusted R2 of the models.

Supporting information

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

GWAS summary data are available at ftp://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/databases/gwas/summary_statistics/GCST90002409 and has been deposited at the EGG Consortium website (https://egg-consortium.org/). Access to individual study-level data may be subject to local rules and regulations.

Funding Statement

CP received funding from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust and University College London. MMcC is a Wellcome Senior Investigator and an NIHR Senior Investigator. MMcC received funding from Wellcome (090532, 106130, 098381, 203141, 212259), NIDDK (U01-DK105535), and NIHR (NF-SI-0617-10090). TGMV was supported by ZonMW (TOP 40–00812–98–11010). DLC was supported by the American Diabetes Association Grant 1-17-PDF-077. SFAG is supported by the Daniel B. Burke Chair for Diabetes Research and NIH Grant R01 HD058886. NVT is funded by a pre-doctoral grant from the Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (2017 FI_B 00636), Generalitat de Catalunya – Fons Social Europeu. BK received personal funding from the European Research Council Advanced Grant META-GROWTH (ERC-2012-AdG – no. 322605). BF was supported by an Oak Foundation Fellowship. RMF and RNB are supported by Sir Henry Dale Fellowship (Wellcome Trust and Royal Society grant: WT104150). ATH is supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator award (grant number 098395/Z/12/Z). DM is supported by a Canada Research Chair. DLC was supported by the American Diabetes Association Grant 1-17-PDF-077. JTL was supported by the Finnish Cultural Foundation. DIB received a KNAW Academy Professor Award (PAH/6635). MH received PhD scholarship funding from TARGET (http://target.ku.dk), The Danish Diabetes Academy (http://danishdiabetesacademy.dk) and the Copenhagen Graduate School of Health and Medical Sciences. VWVJ received funding from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (VIDI 016.136.361) and the European Research Council (ERC-2014-CoG-648916). ISF was supported by the European Research Council, Wellcome Trust (098497/Z/12/Z), Medical Research Council (MRC_MC_UU_12012/5), the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, the Botnar Foundation, the Bernard Wolfe Health Neuroscience Endowment and the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) project Beta-JUDO n°279153. IB acknowledges funding from Wellcome (WT206194). ES works in a unit that receives funding from the University of Bristol and the UK Medical Research Council (MC_UU_00011/1, MC_UU_00011/3). GDS works in the Medical Research Council Integrative Epidemiology Unit at the University of Bristol, which is supported by the Medical Research Council (MC_UU_00011/1). KC received funds from the French National Agency of Research, F-CRIN/FORCE. All funding for the studies that provided the underlying data for this manuscript can be found in S1 Text. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, data interpretation, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2627–42. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silventoinen K, Jelenkovic A, Sund R, Hur YM, Yokoyama Y, Honda C, et al. Genetic and environmental effects on body mass index from infancy to the onset of adulthood: an individual-based pooled analysis of 45 twin cohorts participating in the COllaborative project of Development of Anthropometrical measures in Twins (CODATwins) study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104(2):371–9. 10.3945/ajcn.116.130252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silventoinen K, Jelenkovic A, Sund R, Yokoyama Y, Hur YM, Cozen W, et al. Differences in genetic and environmental variation in adult BMI by sex, age, time period, and region: an individual-based pooled analysis of 40 twin cohorts. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(2):457–66. 10.3945/ajcn.117.153643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khera AV, Chaffin M, Wade KH, Zahid S, Brancale J, Xia R, et al. Polygenic Prediction of Weight and Obesity Trajectories from Birth to Adulthood. Cell. 2019;177(3):587–96 e9. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.03.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang J, Bakshi A, Zhu Z, Hemani G, Vinkhuyzen AA, Lee SH, et al. Genetic variance estimation with imputed variants finds negligible missing heritability for human height and body mass index. Nat Genet. 2015;47(10):1114–20. 10.1038/ng.3390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang J, Manolio TA, Pasquale LR, Boerwinkle E, Caporaso N, Cunningham JM, et al. Genome partitioning of genetic variation for complex traits using common SNPs. Nat Genet. 2011;43(6):519–25. 10.1038/ng.823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yengo L, Sidorenko J, Kemper KE, Zheng Z, Wood AR, Weedon MN, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for height and body mass index in approximately 700000 individuals of European ancestry. Hum Mol Genet. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felix JF, Bradfield JP, Monnereau C, van der Valk RJ, Stergiakouli E, Chesi A, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies three new susceptibility loci for childhood body mass index. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25(2):389–403. 10.1093/hmg/ddv472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berndt SI, Gustafsson S, Magi R, Ganna A, Wheeler E, Feitosa MF, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 11 new loci for anthropometric traits and provides insights into genetic architecture. Nat Genet. 2013;45(5):501–12. 10.1038/ng.2606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, Justice AE, Pers TH, Day FR, et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature. 2015;518(7538):197–206. 10.1038/nature14177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winkler TW, Justice AE, Graff M, Barata L, Feitosa MF, Chu S, et al. Correction: The Influence of Age and Sex on Genetic Associations with Adult Body Size and Shape: A Large-Scale Genome-Wide Interaction Study. PLoS Genet. 2016;12(6):e1006166 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haworth S, Shapland CY, Hayward C, Prins BP, Felix JF, Medina-Gomez C, et al. Low-frequency variation in TP53 has large effects on head circumference and intracranial volume. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):357 10.1038/s41467-018-07863-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graff M, Ngwa JS, Workalemahu T, Homuth G, Schipf S, Teumer A, et al. Genome-wide analysis of BMI in adolescents and young adults reveals additional insight into the effects of genetic loci over the life course. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(17):3597–607. 10.1093/hmg/ddt205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JW, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2008;9(5):474–88. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00475.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bjerregaard LG, Jensen BW, Angquist L, Osler M, Sorensen TIA, Baker JL. Change in Overweight from Childhood to Early Adulthood and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(14):1302–12. 10.1056/NEJMoa1713231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang T, Zhang H, Li Y, Sun D, Li S, Fernandez C, et al. Temporal Relationship Between Childhood Body Mass Index and Insulin and Its Impact on Adult Hypertension: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Hypertension. 2016;68(3):818–23. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sinaiko AR, Donahue RP, Jacobs DR Jr., Prineas RJ. Relation of weight and rate of increase in weight during childhood and adolescence to body size, blood pressure, fasting insulin, and lipids in young adults. The Minneapolis Children's Blood Pressure Study. Circulation. 1999;99(11):1471–6. 10.1161/01.cir.99.11.1471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mamun AA, Lawlor DA, Alati R, O'Callaghan MJ, Williams GM, Najman JM. Increasing body mass index from age 5 to 14 years predicts asthma among adolescents: evidence from a birth cohort study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007;31(4):578–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimmermann E, Bjerregaard LG, Gamborg M, Vaag AA, Sorensen TIA, Baker JL. Childhood body mass index and development of type 2 diabetes throughout adult life-A large-scale danish cohort study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25(5):965–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bulik-Sullivan B, Finucane HK, Anttila V, Gusev A, Day FR, Loh PR, et al. An atlas of genetic correlations across human diseases and traits. Nat Genet. 2015;47(11):1236–41. 10.1038/ng.3406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pickrell JK, Berisa T, Liu JZ, Segurel L, Tung JY, Hinds DA. Detection and interpretation of shared genetic influences on 42 human traits. Nat Genet. 2016;48(7):709–17. 10.1038/ng.3570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang J, Ferreira T, Morris AP, Medland SE, Genetic Investigation of ATC, Replication DIG, et al. Conditional and joint multiple-SNP analysis of GWAS summary statistics identifies additional variants influencing complex traits. Nat Genet. 2012;44(4):369–75, S1-3. 10.1038/ng.2213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bulik-Sullivan BK, Loh PR, Finucane HK, Ripke S, Yang J, Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics C, et al. LD Score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2015;47(3):291–5. 10.1038/ng.3211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Staley JR, Blackshaw J, Kamat MA, Ellis S, Surendran P, Sun BB, et al. PhenoScanner: a database of human genotype-phenotype associations. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(20):3207–9. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, Beral V, Burton P, Danesh J, et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12(3):e1001779 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bycroft C, Freeman C, Petkova D, Band G, Elliott LT, Sharp K, et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018;562(7726):203–9. 10.1038/s41586-018-0579-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu Y, Day FR, Gustafsson S, Buchkovich ML, Na J, Bataille V, et al. New loci for body fat percentage reveal link between adiposity and cardiometabolic disease risk. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10495 10.1038/ncomms10495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradfield JP. Personal communication, June 20, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rolland-Cachera MF, Deheeger M, Bellisle F, Sempe M, Guilloud-Bataille M, Patois E. Adiposity rebound in children: a simple indicator for predicting obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 1984;39(1):129–35. 10.1093/ajcn/39.1.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Consortium GTEx. Human genomics. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science. 2015;348(6235):648–60. 10.1126/science.1262110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landgraf K, Rockstroh D, Wagner IV, Weise S, Tauscher R, Schwartze JT, et al. Evidence of early alterations in adipose tissue biology and function and its association with obesity-related inflammation and insulin resistance in children. Diabetes. 2015;64(4):1249–61. 10.2337/db14-0744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giambartolomei C, Vukcevic D, Schadt EE, Franke L, Hingorani AD, Wallace C, et al. Bayesian test for colocalisation between pairs of genetic association studies using summary statistics. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(5):e1004383 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.UniProt C. UniProt: a hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D204–12. 10.1093/nar/gku989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(1):1–13. 10.1093/nar/gkn923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dickinson ME, Flenniken AM, Ji X, Teboul L, Wong MD, White JK, et al. High-throughput discovery of novel developmental phenotypes. Nature. 2016;537(7621):508–14. 10.1038/nature19356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kircher M, Witten DM, Jain P, O'Roak BJ, Cooper GM, Shendure J. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat Genet. 2014;46(3):310–5. 10.1038/ng.2892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ikram MA, Brusselle GGO, Murad SD, van Duijn CM, Franco OH, Goedegebure A, et al. The Rotterdam Study: 2018 update on objectives, design and main results. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32(9):807–50. 10.1007/s10654-017-0321-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walker MG, Volkmuth W, Sprinzak E, Hodgson D, Klingler T. Prediction of gene function by genome-scale expression analysis: prostate cancer-associated genes. Genome Res. 1999;9(12):1198–203. 10.1101/gr.9.12.1198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun J, Tao S, Gao Y, Peng T, Tan A, Zhang H, et al. Genome-wide association study identified novel genetic variant on SLC45A3 gene associated with serum levels prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in a Chinese population. Hum Genet. 2013;132(4):423–9. 10.1007/s00439-012-1254-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pin E, Henjes F, Hong MG, Wiklund F, Magnusson P, Bjartell A, et al. Identification of a Novel Autoimmune Peptide Epitope of Prostein in Prostate Cancer. J Proteome Res. 2017;16(1):204–16. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim S, Shin C, Jee SH. Genetic variants at 1q32.1, 10q11.2 and 19q13.41 are associated with prostate-specific antigen for prostate cancer screening in two Korean population-based cohort studies. Gene. 2015;556(2):199–205. 10.1016/j.gene.2014.11.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yanpallewar S, Wang T, Koh DC, Quarta E, Fulgenzi G, Tessarollo L. Nedd4-2 haploinsufficiency causes hyperactivity and increased sensitivity to inflammatory stimuli. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32957 10.1038/srep32957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goel P, Manning JA, Kumar S. NEDD4-2 (NEDD4L): the ubiquitin ligase for multiple membrane proteins. Gene. 2015;557(1):1–10. 10.1016/j.gene.2014.11.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Donovan P, Poronnik P. Nedd4 and Nedd4-2: ubiquitin ligases at work in the neuron. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45(3):706–10. 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Llewellyn CH, Trzaskowski M, van Jaarsveld CHM, Plomin R, Wardle J. Satiety mechanisms in genetic risk of obesity. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(4):338–44. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wardle J, Carnell S, Haworth CM, Farooqi IS, O'Rahilly S, Plomin R. Obesity associated genetic variation in FTO is associated with diminished satiety. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(9):3640–3. 10.1210/jc.2008-0472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Magno F, Guarana HC, Fonseca ACP, Cabello GMK, Carneiro JRI, Pedrosa AP, et al. Influence of FTO rs9939609 polymorphism on appetite, ghrelin, leptin, IL6, TNFalpha levels, and food intake of women with morbid obesity. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2018;11:199–207. 10.2147/DMSO.S154978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Long JZ, Roche AM, Berdan CA, Louie SM, Roberts AJ, Svensson KJ, et al. Ablation of PM20D1 reveals N-acyl amino acid control of metabolism and nociception. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(29):E6937–E45. 10.1073/pnas.1803389115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Long JZ, Svensson KJ, Bateman LA, Lin H, Kamenecka T, Lokurkar IA, et al. The Secreted Enzyme PM20D1 Regulates Lipidated Amino Acid Uncouplers of Mitochondria. Cell. 2016;166(2):424–35. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sovio U, Mook-Kanamori DO, Warrington NM, Lawrence R, Briollais L, Palmer CN, et al. Association between common variation at the FTO locus and changes in body mass index from infancy to late childhood: the complex nature of genetic association through growth and development. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(2):e1001307 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baker JL, Olsen LW, Sorensen TI. Childhood body-mass index and the risk of coronary heart disease in adulthood. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(23):2329–37. 10.1056/NEJMoa072515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tirosh A, Shai I, Afek A, Dubnov-Raz G, Ayalon N, Gordon B, et al. Adolescent BMI trajectory and risk of diabetes versus coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(14):1315–25. 10.1056/NEJMoa1006992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raitakari OT, Juonala M, Kahonen M, Taittonen L, Laitinen T, Maki-Torkko N, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in childhood and carotid artery intima-media thickness in adulthood: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Jama. 2003;290(17):2277–83. 10.1001/jama.290.17.2277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Juonala M, Magnussen CG, Berenson GS, Venn A, Burns TL, Sabin MA, et al. Childhood adiposity, adult adiposity, and cardiovascular risk factors. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(20):1876–85. 10.1056/NEJMoa1010112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Burgess JA, Walters EH, Byrnes GB, Giles GG, Jenkins MA, Abramson MJ, et al. Childhood adiposity predicts adult-onset current asthma in females: a 25-yr prospective study. Eur Respir J. 2007;29(4):668–75. 10.1183/09031936.00080906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang YL, Wang YT, Li JF, Zhang YZ, Yin HL, Han B. Body Mass Index and Risk of Parkinson's Disease: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0131778 10.1371/journal.pone.0131778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Umer A, Kelley GA, Cottrell LE, Giacobbi P Jr, Innes KE, Lilly CL. Childhood obesity and adult cardiovascular disease risk factors: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):683 10.1186/s12889-017-4691-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith GD, Ebrahim S. 'Mendelian randomization': can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32(1):1–22. 10.1093/ije/dyg070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davey Smith G, Hemani G. Mendelian randomization: genetic anchors for causal inference in epidemiological studies. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(R1):R89–98. 10.1093/hmg/ddu328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Currie C, Ahluwalia N, Godeau E, Nic Gabhainn S, Due P, Currie DB. Is obesity at individual and national level associated with lower age at menarche? Evidence from 34 countries in the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children Study. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50(6):621–6. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.10.254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Richardson TG, Sanderson E, Elsworth B, Tilling K, Davey Smith G. Can the impact of childhood adiposity on disease risk be reversed? A Mendelian randomization study. medRxiv. 2019. 10.1101/19008011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roos E, Grotta A, Yang F, Bellocco R, Ye W, Adami HO, et al. Body mass index, sitting time, and risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2018;90(16):e1413–e7. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rokholm B, Silventoinen K, Angquist L, Skytthe A, Kyvik KO, Sorensen TI. Increased genetic variance of BMI with a higher prevalence of obesity. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20816 10.1371/journal.pone.0020816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rokholm B, Silventoinen K, Tynelius P, Gamborg M, Sorensen TI, Rasmussen F. Increasing genetic variance of body mass index during the Swedish obesity epidemic. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27135 10.1371/journal.pone.0027135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ajslev TA, Angquist L, Silventoinen K, Baker JL, Sorensen TI. Trends in parent-child correlations of childhood body mass index during the development of the obesity epidemic. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109932 10.1371/journal.pone.0109932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ajslev TA, Angquist L, Silventoinen K, Baker JL, Sorensen TI. Stable intergenerational associations of childhood overweight during the development of the obesity epidemic. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23(6):1279–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alves AC, De Silva NMG, Karhunen V, Sovio U, Das S, Taal HR, et al. GWAS on longitudinal growth traits reveal different genetic factors influencing infant, child and adult BMI. Science Advances, 2019. September 4;5(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Helgeland Ø, Vaudel M, Juliusson PB, Holmen OL, Juodakis J, Johansson S, et al. Genome-wide association study reveals a dynamic role of common genetic variation in infant and early childhood growth. Nature Communications, 10, 4448 (2019). 10.1038/s41467-019-12308-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(17):2190–1. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Du P, Kibbe WA, Lin SM. lumi: a pipeline for processing Illumina microarray. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(13):1547–8. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schmid R, Baum P, Ittrich C, Fundel-Clemens K, Huber W, Brors B, et al. Comparison of normalization methods for Illumina BeadChip HumanHT-12 v3. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:349 10.1186/1471-2164-11-349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Johnson WE, Li C, Rabinovic A. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics. 2007;8(1):118–27. 10.1093/biostatistics/kxj037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barbosa-Morais NL, Dunning MJ, Samarajiwa SA, Darot JF, Ritchie ME, Lynch AG, et al. A re-annotation pipeline for Illumina BeadArrays: improving the interpretation of gene expression data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(3):e17 10.1093/nar/gkp942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shabalin AA. Matrix eQTL: ultra fast eQTL analysis via large matrix operations. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(10):1353–8. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

GWAS summary data are available at ftp://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/databases/gwas/summary_statistics/GCST90002409 and has been deposited at the EGG Consortium website (https://egg-consortium.org/). Access to individual study-level data may be subject to local rules and regulations.