Abstract

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, medical schools needed to redirect students to alternative educational opportunities. The University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine addressed this issue by forming a partnership with rural counties in northern Nevada to create a multicounty COVID-19 hotline clinical experience. Medical students staffed the hotline and assisted the underserved rural populations of northern Nevada by providing counseling and education via telehealth. With the support of preceptors, students completed screening forms with patients, utilized audio-only physical exam skills and clinical decision making to triage potential patients to the appropriate level of care.

Methods

We utilized retrospective pre- and postassessments to assess medical students’ comfort level with several hotline tasks before and after their experience as a hotline volunteer.

Results

Results indicate significant improvements after hotline training and experience in students’ comfort level with answering questions about SARS-CoV-2 (P=.006); screening patients for SARS-CoV-2 (P=.0446); assessing exam findings using audio only format ( P=.0429); triaging patients (P=.0103); and addressing financial access to care barriers ( P=.0127).

Conclusion

Participation in the multicounty COVID-19 hotline improved students’ comfort levels in all areas, with significant improvement in answering questions about SARS-CoV-2, conducting audio-only exams, screening and triaging patients, and addressing financial barriers to care. Participation allowed students to further hone their clinical skills during a pandemic. This experience can serve as a model for similar projects for other academic institutions to train their medical students while providing outreach, particularly to underserved populations such as rural communities.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and resultant personal protective equipment shortage led to the displacement of medical students nationwide, from clinical rotations to nonclinical duties.1–3 The University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine (UNR Med) requires rural rotations for all medical students. Consequently, UNR Med needed rural experiences for their graduating fourth-year students in a setting that minimized risk of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 and offered educational opportunities. Rural northern Nevada counties were struggling to staff a hotline to address residents’ questions, provide information from reliable resources, reduce the burden on the local health care system, and triage patients to conserve test kits for appropriate patients.4,5 A partnership was formed between these counties and UNR Med. This evolved into a volunteer experience for students at all levels of training to staff the hotline under the supervision of the county health officers and UNR Med faculty physicians (see Table 1 for timeline). Participation in the hotline served as both a clinical and educational experience. Educational objectives included increasing familiarity with an audio-only telehealth model, developing audio-only exam skills and clinical decision making to triage patients, and providing exposure to rural population and barriers to care.

Table 1.

Timeline of Major Events and Key Training Sessions of the COVID-19 Hotline for Rural Nevada

| Date | Major Events Affecting Medical Student Education and/or Hotline Development | Detailsa |

|---|---|---|

| 3/12/2020 | First- and second-year students removed from clinical experiences and transitioned to online education | |

| 3/17/2020 | Risk Mitigation Initiative issued by Nevada state governor (“Stay Home for Nevada”)8 | |

| 3/17/2020 | AAMC issued guidance1 indicating their support for medical schools “pausing all student clinical rotations”; third- and fourth-year students pulled from clinical rotations | |

| 3/20–24/2020 | Hotline concept conceived by Elko County; hotline developed by county personnel and UNR Med; fourth-year medical students designated as target workforce | UNR Med recruitment of rural faculty to precept, recruitment of fourth-year medical students who need rural credit for graduation, development of triaging and testing algorithms |

| 3/25/2020 | First e-training meeting | Key discussion topics included: Introductions to clinical preceptors, technical training, triaging and testing algorithms, introduction to rural care and geography, nearest healthcare facilities |

| 3/26/2020 | Hotline launched by Elko County | Initial county served: Elko |

| 3/27/2020 | Additional student volunteers recruited | Students recruited from all years of training |

| 3/30/2020 | Hotline service area expansion | Addition of three more rural counties to service area |

| 4/2/2020 | Second e-training meeting | Review of SARS-CoV-2 symptoms, workflow and referral process |

| 4/6/2020 | Third e-training meeting and expansion of service area | Transition to weekly e-training meetings with all students; discussion of usage of clinical judgment; fifth county added to service area |

| 4/13/2020 | Fourth e-training meeting | Discuss sharing public health information; importance of complete epidemiologic data through the county screening form (similar to the Center for Disease Control’s phone triage form9); update security protocol for shared applications (HIPAA compliance); testing protocols; training for audio-only respiratory triage, pediatric respiratory distress signs; late vs early signs of distress; details for new counties being covered by hotline |

| 4/20/2020 | Fifth e-training meeting and expansion of service area | Address importance of handoffs between shifts; 6th county added |

| 4/27/2020 | Hotline e-training | Education regarding public health contact tracing efforts |

| 5/4/2020 | Hotline e-training | Education regarding public health role of mass testing; reinforce usage of 911 for emergency situations |

| 5/11/2020 | Hotline e-training and expansion of service area | Newest research and tools including self-diagnostic apps; role of hotline as state prepared for reopening including personal accountability and resources for business owners; Ely Shoshone Tribe added to our service |

| 5/18/2020 | Hotline e-training | Hotline to help register participants for mass testing event |

| 6/1/2020 | Hotline e-training | Disseminating lab results from mass testing |

Abbreviations: AAMC, Association of American Medical Colleges; UNR, University of Nevada, Reno; HIPPA, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

The following were discussed in every e-training meeting and therefore, after their first presentation in the table, are not indicated in the “Details” column: review technical training, updates regarding CDC guidelines, triaging protocol or workflow changes, discuss local epidemiological data.

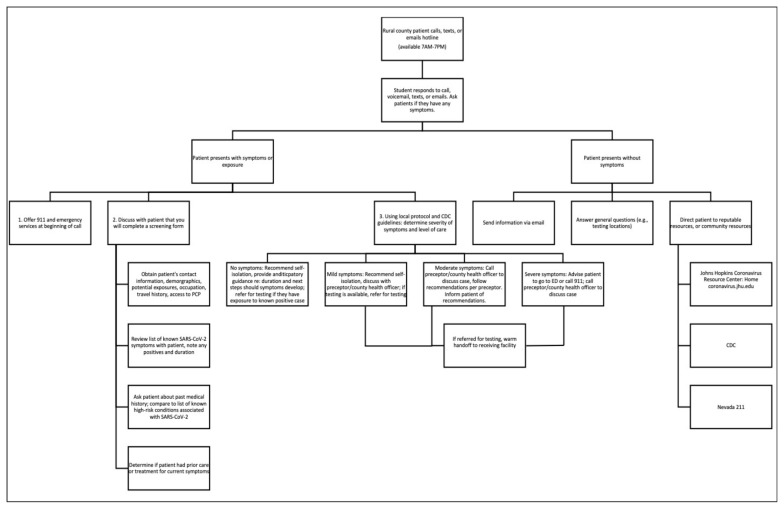

Challenges for the hotline included rapidly evolving information about SARS-CoV-2 and the varying levels of clinical experience amongst the volunteers. Preceptors developed regular weekly e-trainings and an online database of resources to address these educational topics (Table 1), lists of rural providers and resources, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines, patient handouts, and the “Script.” The Script is a continuously updated document containing technical training, clinical information about SARS-CoV-2, county-specific protocols for patient evaluation and testing, and algorithms for addressing patient symptoms and concerns. Figure 1 details a summarized workflow for a patient call. Students precepted and provided completed screening forms to the county health officers and/or UNR Med faculty physicians for review. If they referred patients for medical evaluation or testing, they also discussed the case with the providers at the receiving facility. This setup is similar to in-person preceptorships during nonpandemic medical education.

Figure 1.

Workflow for Medical Students Answering Calls on COVID-19 Hotline

We completed a literature review for guidance when developing the hotline and educational goals. We found minimal literature on medical students’ participation in hotline and audio-only clinical experiences.6,7 This necessitated a program evaluation to assess effectiveness of the virtual teaching modality, students’ rural experiences, students’ comfort with hotline tasks, and audio-only triage. We hypothesized that involvement in the hotline e-training, as well as experience assisting patients in real time, would improve students’ comfort level with these tasks.

Methods

After 3 months of hotline implementation, students were asked to complete an anonymous retrospective survey to assess program outcomes and how well the experience met educational objectives. The assessment was designed to assess the effectiveness of the educational methods used to teach the students. Since this research project used that existing data, institutional review board oversight was not necessary for this study because the original intent was to review an educational program. Data were collected at the beginning and end of an e-training during the twelfth week. Students were asked about their rural experiences and comfort level with hotline tasks before working any shifts, and after several shifts. We conducted a paired t test to evaluate for significant changes in students’ responses.

Results

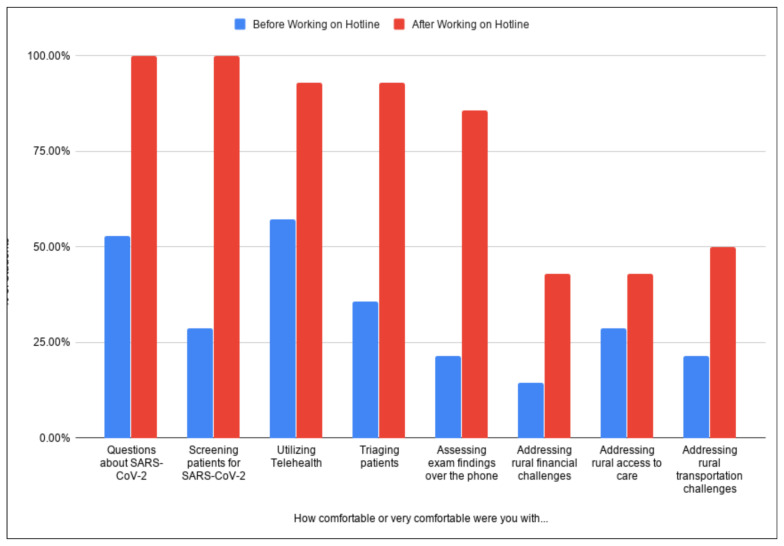

A total of 17 students out of 35 who worked on the hotline responded to the survey. Five survey questions addressed students’ comfort level with telehealth, SARS-CoV-2 knowledge, screening and triaging, and clinical skills; three survey questions assessed students’ comfort level with addressing these barriers before and after participation (Figure 2). Three questions surveyed the frequency patients disclosed access to care barriers (Table 2). Eighty-eight percent of the students triaged and referred a patient who lived 60 or more minutes from the nearest health care facility; this occurred at least four times for 41% of the students. We conducted a paired-sample t test to compare students’ pre- and postexperience comfort levels with hotline tasks (Table 3). The most notable changes in comfort level were with screening patients and assessing exam findings over the phone.

Figure 2.

Medical Students’ Pre- and Posthotline Experience Comfort Level

Table 2.

Frequency Patients Disclosed Access to Care Barriers

| Response | When you were completing a screening form with a caller, how often did they indicate that they didn’t have a PCP? | When working a shift, how frequently did you hear about financial barriers to receiving adequate medical care? | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Percent | n | Percent | |

| Very frequently | 6 | 35.29 | 3 | 17.65 |

| Frequently | 6 | 35.29 | 3 | 17.65 |

| Occasionally | 3 | 17.65 | 5 | 29.41 |

| Rarely | 1 | 5.88 | 3 | 17.65 |

| Very rarely | 1 | 5.88 | 3 | 17.65 |

| Never | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Total | 17 | 17 | ||

Abbreviation: PCP, primary care physician.

Table 3.

Paired t test Results of Student Comfort Level With Various Hotline Tasks

| Question | How comfortable or very comfortable were you with… | % Change |

t Test P Value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | |||||||

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | |||

| Questions about SARS-CoV-2 | 9 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 16 | 4.83 | 0.37 | 77.78% | .0060* |

| Screening patients for SARS-CoV-2 | 4 | 3.17 | 1.21 | 16 | 4.67 | 0.47 | 300.00% | .0446* |

| Utilizing telehealth | 8 | 3.67 | 0.94 | 15 | 4.67 | 0.47 | 87.50% | .0756 |

| Triaging patients | 5 | 2.83 | 0.90 | 14 | 4.17 | 0.69 | 180.00% | .0103* |

| Assessing exam findings over the phone | 3 | 2.83 | 1.34 | 14 | 4.17 | 0.69 | 366.67% | .0429* |

| Addressing rural financial challenges | 2 | 2.17 | 1.34 | 7 | 3.33 | 0.94 | 250.00% | .0127* |

| Addressing rural access to care | 4 | 2.67 | 1.49 | 7 | 3.50 | 0.76 | 75.00% | .2242 |

| Addressing rural transportation challenges | 3 | 2.33 | 1.37 | 8 | 3.00 | 1.41 | 166.67% | .2354 |

Statistically significant at α=.05

Discussion

The pre- and postassessment demonstrates that students met educational objectives in learning to utilize telehealth, address rural challenges, and develop audio-only exam and triage skills. Participation in the multicounty COVID-19 hotline improved students’ comfort levels in all areas, with significant changes noted for answering questions, screening and triaging patients, conducting audio-only exam, and addressing rural financial challenges (Table 3). Nonsignificant improvements were seen for utilizing telehealth, addressing rural access to care, and rural transportation challenges. The most significant changes reported were with answering questions about SARS-CoV-2 and triaging patients. The reported increase in students’ comfort with these tasks indicates their improvement in clinical skills and decision-making via a telehealth model. In addition, students had exposure to rural access to care barriers and developed comfort addressing these issues, but additional education on these topics is an area for improvement. Results show this remote clinical experience utilizing telehealth and weekly e-trainings is a viable and effective educational model to develop students’ clinical exam and decision-making skills.

Limitations include the small sample size and the delay in administration of the survey. Future students will receive a survey prior to starting their first hotline shift to reduce recall bias. When developing the hotline and associated curriculum, there was limited literature available for reference on similar audio-only trainings for students in a triage capacity.6,7 This research is presented as a prototype for other institutions to implement telehealth as a form of rural outreach and medical student education. Through early exposure to telehealth, students can develop comfort and familiarity with this method of delivering health care that they can incorporate into their future practice. If future public health crises place similar limitations on students’ clinical experiences, this is an effective model to develop students’ clinical skills and decision making in a supervised setting with established protocols.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge T. Brian Callister, MD, Professor of Medicine and Director, Rural Medical Education, University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine; Bryce Putnam, DMD, Elko County Health Officer; and Fellow Medical Student Volunteers.

References

- 1.Prescott JE. Important Guidance for Medical Students on Clinical Rotations During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Outbreak. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; Jun 5, 2020. [Accessed June 5, 2020]. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/important-guidance-medical-students-clinical-rotations-during-coronavirus-covid-19-outbreak. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khamees D, Brown CA, Arribas M, Murphey AC, Haas MRC, House JB. In crisis: medical students in the COVID-19 pandemic. AEM Education and Training. 2020 Mar;:1–7. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiner S. Bright lights in a dark time: medical students step up to help out. Association of American Medical Studnets; [Accessed June 5, 2020]. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/bright-lights-dark-time-medical-students-step-help-out. Published April 2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.County launches coronavirus hotline. [Accessed September 11, 2020];Elko Daily Free Press. 2020 Mar 26; https://elkodaily.com/news/local/county-launches-coronavirus-hotline/article_9158dd0a-1fd5-585a-82a4-b2bdb2bf6e92.html.

- 5.Milano T. COVID-19 hotline serves five rural Nevada counties. Elko Daily Free Press; Apr 14, 2020. [Accessed September 11, 2020]. https://elkodaily.com/news/local/covid-19-hotline-serves-five-rural-nevada-counties/article_b16a8eac-ec34-59b2-aad0-9a0e093f6b00.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schaufelberger M, Harris M, Frey P. Emergency telephone consultations: a new course for medical students. Clin Teach. 2012;9(6):373–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-498X.2012.00590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seale J, Ragbourne SC, Purkiss Bejarano N, et al. Training final year medical students in telephone communication and prioritization skills: an evaluation in the simulated environment. Med Teach. 2019;41(9):1023–1028. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2019.1610559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sisolak S. [Accessed June 5, 2020];NV Health Response COVID19 Risk Management Initiative. 2020 http://gov.nv.gov/uploadedFiles/govnewnvgov/Content/News/Emergency_Orders/2020_attachments/2020-03-17-NV-Health-Reponse-COVID19-Risk-Management-Initiative-2.pdf.

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Telephone Response Guide for Clinics. [Accessed August 17, 2020];Phone Advice Line Tool for Possible COVID-19 Patients. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/phone-guide/index.html. Published May 22, 2020.