Abstract

Remediation of organic pollutant matrixes from wastewater by photodegradation using different heterojunctions is extensively studied to improve performance for potential application. Brilliant black (BB) and p-nitrophenol (PNP) have been detected in the environment and implicated as directly or indirectly carcinogenic to human health. This work analyzes their elimination from aqueous solutions under visible-light irradiation with composites of cobalt(II, III) oxide and bismuth oxyiodides (Co3O4/Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I). The synthesized nanomaterial properties were investigated using various techniques such as BET, SEM/EDS, TEM, XRD, FTIR, PL, and UV–vis. All the nanocomposites absorbed in the visible range of the solar spectrum with band gaps between 1.68 and 2.79 eV, and the specific surface area of the CB2 composite increased by 35.8% from that of Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I. There was an observed massive reduction in the rate of electron and hole recombination, and the band gaps of the composites decreased. The mineralization of PNP and BB was followed by determination of the total organic carbon with reductions of 93.6 and 83.7%, respectively. The main active species were the hydroxyl radicals, while the superoxide anion radical and generated holes were minor as confirmed by radical trapping experiments. The optimum pHs for degradation of PNP and BB were 9.6 and 5.3, respectively. The enhanced performance of the catalyst was due to C-scheme heterojunction formation that reduced the electron and hole recombination rate and was attributed to strong adsorption of the pollutants on the photocatalyst active surface. The nanocomposite is apposite for solar energy-driven remediation of organic pollutants from environmental aqueous samples.

1. Introduction

The adulteration triggered by carbon-based contaminants is still an irresistible global challenge due to the hasty evolution of industrialization and the spiraling of natural environments. Organic dyes and nitrophenols are among the major contributors to pollution due to their complex geometry and toxicological effects.1,2 Nitrophenols find applications in different fields such as in textile, pharmaceutical, agricultural sectors, etc. while the azo dyes like brilliant black are mostly used as food colorants and in textiles.3p-Nitrophenol is carcinogenic and toxic and has an endocrine disruption ability. Brilliant black like other azo dyes can be converted into carcinogenic aromatic amines by anaerobic microorganisms.4

Routine wastewater decontamination fails in removal of nitrophenol chemicals and organic dyes because of their biocompatibility and high stability, and their removal is among the most studied in recent years. Researchers investigated different methods among which semiconductor photocatalysis has fascinated different groups with a likelihood of widespread applicability, high competency, and elimination of secondary pollution.5,6 The principle of this technique requires external energy to drive photocatalytic reactions, which follows light absorption and generation of different reactive oxygen species (ROSs) on the surface of the catalyst, like hydroxyl radicals that are non-selective.6 TiO2 has been widely used since the discovery of its water splitting capability by Fujishima and Honda in 19717 because it has numerous advantages such as low costs and chemical stability.5 However, its practical applicability as a photocatalyst has been restricted by its large band gap, fast recombination of photoinduced charge carriers, and poor adsorption capacity for most organic chemicals.8,9 Numerous methods were employed to address all these problems like doping,10 co-doping,11 formation of heterojunctions with other semiconductors,12 surface sensitization,13 etc., which could hardly be corrected concurrently at optimum conditions. Different innovative applications were tried such as fabrication of light-harvesting perovskites,14 visible-light active metal oxide semiconductors,15 organic semiconductors,16 etc., which eventually were either doped or coupled with other semiconductors to form different heterojunctions such as p–n, Mott–Schottky, direct and indirect Z-schemes,17−19 etc. to enhance their possibility for large-scale applicability. The formation of heterojunctions stood out as the most prevalent and economical method for reduction of the rate of recombination of electron and hole pairs and high photocatalytic activity.20

Bismuth oxyhalide semiconductors, especially those of iodine generally referred to as bismuth oxyiodides (BixOyIz), have been confirmed to possess excellent photocatalytic activity under visible-light irradiation for applications such as CO2 reduction, mineralization of pollutants, and heavy-metal reduction.21 Bi4O5I2 and Bi5O7I are photocatalytic semiconductors for degradation of organic pollutants owing to their special electronic structures according to literature reports.22 Their conduction band bottom comprises 6p orbitals of Bi, and their valence band maxima is due to Bi 6s, O 2p, and I 5p orbitals resulting in a dispersed hybridized valence band, which favors the migration of photogenerated holes and the oxidation reaction.23 Moreover, the different bismuth oxyiodide formations depend on the annealing temperature or different solution pH values. Dai et al. synthesized Bi5O7I with high performance for elemental mercury removal by glacial acetic acid-assisted coprecipitation and pH tuning of synthesized BiOI microspheres.21 The high photocatalytic activity was attributed to their special optical properties and initiated by the activity of superoxide anion radicals and holes. Moreover, Cheng et al. reported a heterojunction of BiOI/Bi4O5I2 with high photocatalytic activity for removal of mercury under visible-light irradiation formed from in situ crystallized BiOI calcined at 390 °C for 2 h.24 Fabrication of different BixOyIz catalysts by thermal decomposition of BiOI was reported.25 Interestingly, a combination of oxygen vacancy, iodine deficiency, and phase engineering was reported to result in enhanced photocatalytic activity.26,27 However, a high concentration of iodine vacancies in the crystal lattice may lead to high band gaps.27 The heterostructures of BixOyIz composites can be enhanced by incorporation of other semiconductors that have different optical properties for improved performance.

The use of a cobalt(II, III) oxide spinel (Co3O4) is enticing and has been studied extensively in recent years due to different properties. The variance in oxygen holes, oxygen defects, and oxygen adsorbed in different states of cobalt are thought to be the reason for high activity and selectivity of these metal oxide catalysts.28,29 Moreover, cobalt(II, III) oxide is a p-type semiconductor with interesting properties such as high thermal and chemical stability, low solubility, interesting electronic, optical, magnetic, and catalytic properties,30 and a narrow band gap (approximately 1.2–2.1 eV) and also oxidation catalysis properties.31,32 Luo et al. fabricated a photostable composite of Co3O4-Mxene by employing a solvothermal method for degradation of methylene blue and rhodamine B.33 Moreover, composites of Co3O4 have been used for persulfate activation, photocatalytic degradation, and supercapacitators applications.34,35 Therefore, more work still needs to be done on applications of Co3O4 heterojunctions with Bi-based semiconductors to improve the literacy and explore the possibility of enhancing the photocatalytic activity of BixOyIz heterostructures.

In this work, the BiOI precursor was used to synthesize the Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I composite via thermal decomposition, which was fabricated into a C-Scheme heterojunction with Co3O4 via a solvothermal method, which, according to literature investigations, has never been reported. The main objective of this work was to design this novel heterojunction and evaluate its photocatalytic activity for the degradation of organic pollutants, and the novel C-scheme heterojunction and as-synthesized materials were investigated with different techniques to check the surface area, photogenerated carrier’s behavior, crystallinity and phase compositions, structural interaction, and optical properties that could result in enhanced photocatalytic activity. The performance of the nanocomposites was evaluated under visible-light illumination for degradation of p-nitrophenol (PNP) and brilliant black (BB). The degradation of each pollutant was determined to be pH-dependent when the optimum photocatalyst was used, and the charge transfer was proposed to follow the novel C-scheme heterojunction that was hypothesized for the first time.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. FTIR

Figure 1 gives the FTIR spectra of the prepared samples. Co3O4 has two characteristic peaks due to Co3+–O and Co2+–O bonds at around 570 and 671 cm–1, respectively,36 and the Co2+–O bond is clearly visible in all the composites. The OH peaks are observed in Co3O4 as well as the composites at around 1600 cm–1 and a broad weak peak at around 3500 cm–1. Interestingly, The Bi–O vibration bond is very broad in the Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I composite and the CB1, CB2, and CB3 composites. This broad peak could be attributed to the interaction between the respective Bi–O bonds in Bi4O5I2 and Bi5O7I and can be explained through the assumption that the interaction between these materials is very strong and occurs through the respective Bi–O bonds and is not affected by introduction of Co3O4.

Figure 1.

FTIR spectra of Co3O4, Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I, CB1, CB2, and CB5.

Other characteristic peaks of BixOyIz are observed between 1700 and 2990 cm–1. The intense peak of C=O at around 1760 cm–1 can be attributed to the adsorbed solvent (ethanol) that did not evaporate and could prove that the composites have high affinity for C=O in the organic structured materials hence even their adsorption can be estimated to occur through these functional groups. These materials can also be applied for CO2 conversion to CH4 and other valuable products, which alternatively would reduce global warming effects such as the numerous environmental problems of CO2 emission (due to energy from fossil fuels) having been labeled as the main contributor to greenhouse gases.37,38

2.2. XRD

The crystal structure and phase composition of the synthesized nanomaterials were analyzed by XRD and the obtained results are shown in Figure 2. The synthesized Co3O4 displayed diffraction peaks that matched well with the cubic phase of Co3O4 (space group Fd3m), which is consistent with the value given in the standard card (ASTM no. 01-073-1701) and literature. The peaks at 2θ of 19.15, 31.41, 37.02, 38.65, 42.39, 45.07, 55.82, 59.55, and 65.39° were due to 111, 200, 311, 222, 200, 400, 422, 511, and 440 planes. There were no other peaks of any form of impurities present. The XRD spectra of Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I proved the coexistence of these respective materials. There was a clear transformation from the peaks as observed from monoclinic BiOI in a mixture of Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I as confirmed by similar studies that successfully fabricated BiOI following the same synthesis method39 and as per our previous study.40 The diffraction peaks at 2θ of 28.14, 33.63, 46.24, 47.76, 53.48, 55.93, 57.45, and 59.32° can be assigned to 312, 204, 604, 224, 316, 912, 100 and 624, which are indexed to the orthorhombic phase of Bi5O7I (ICDD PDF no. 40-0548).16,18 Other peaks that are very minor are due to Bi4O5I2, and the angles are at 2θ of 27.91, 32.93, and 44.72° corresponding to 102, 200, and 041 planes according to the literature.18 All the diffraction peaks in the XRD pattern of the as-synthesized composites consist of Co3O4, Bi4O5I2, and Bi5O7I powders and proved the existence of these semiconductors in the composites. When increasing the Co3O4 ratio, the XRD peaks of both Co3O4 and Bi5O7I in the CB1, CB2, and CB5 nanocomposites are intensified as determined by other authors elsewhere36 when Co3O4 is added to form a heterojunctions with another metal oxide semiconductor (MOS).

Figure 2.

XRD spectra of (a) BiOI, Co3O4, and Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I and (b) CB1, CB2, and CB5.

The average crystallite sizes were determined from peak broadening using the Scherrer formula, and profile fitting was applied on the 312 peak for Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I, CB1, CB2, and CB3. The values of the average crystallite sizes were determined to be 25.146 and 30.396 for Co3O4 and all the synthesized composites, respectively. The values of the d spacing and the microstrain followed a similar trend with 0.2013 and 0.2627 and 0.000487 and 0.000295 for Co3O4 and the composites, respectively. There was no increase or decrease in the values of d spacing, microstrain, and average crystallite sizes from Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I to CB1, CB2, and CB3, which could be due to small quantities of Co3O4 added to form a heterojunction. The unchanging values imply that the interaction of Bi4O5I2 and Bi5O7I formed through calcination is so strong (as argued by FTIR results) that addition of Co3O4 hardly affects its crystallite size, crystallinity, dislocation density, or average diffusion time (τ) of charge carriers from bulk to the surface of a photocatalyst, which are all important in heterogeneous photocatalytic redox reactions. Compared to BiOI, there were observed changes in the crystallite sizes, crystallinity, and dislocation density as evidently there was a formation of defects and the crystallite size increased as well as the crystallinity of the Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I from those of BiOI (average crystallite size increased from 16.98 to 30.40, the d spacing increased from 0.2325 to 0.22627, and microstrain values decreased from 0.000606 to 0.0.000295). The decrease in the microstrain values implies that there was an increase in the crystallinity during the formation of Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I that is expected to result in increased photoactivity and this is further argued by the increase in the crystallite size and defects. The increase in the formation of defects has been reported41 to be enhanced by iodine deficiency that occurs in BiOI transformation as iodine gas is emitted. The decrease in the size from BiOI to Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I could be inferred to an increase in the average diffusion time of charge carriers. Interestingly, the large particle size formed during the formation of composites could enhance the decrease in the recombination of photogenerated charge carriers and increase photocatalytic activity. However, since no changes were observed as Co3O4 was added, the formed defects are stable, and it can be inferred that the changes in the photocatalytic activity of the fabricated composites are influenced by other factors. These factors may include the morphology, the absorption capacity of visible-light radiation (determined by band gap energies) and reduction in photogenerated electron and hole pair recombination. Despite the increasing intensities of the diffraction peaks with respect to increasing Co3O4 content, the crystallographic properties and phase compositions of the materials were not affected.

2.3. SEM/EDX

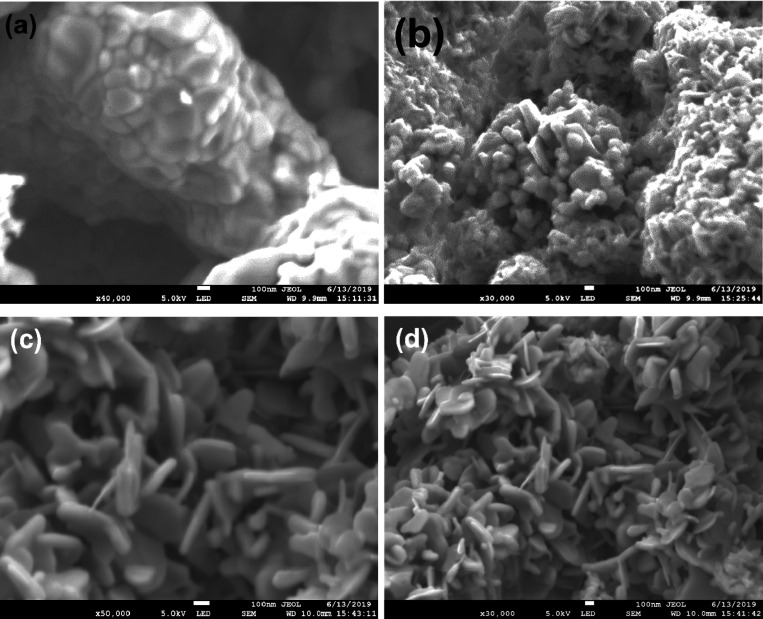

The morphologies of Co3O4, Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I, CB2, and CB5 were studied using FE-SEM as displayed by Figure 3a–d. The Co3O4 calcined at 450 °C gave disc-like semi-spherical particles in the range of 50–300 nm that are compactly aggregated into 3D stalks of an irregular shape (Figure 3a). Figure 3b shows the Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I heterogeneous particles that consist of mainly spherical and rod-shaped particles that are aggregated with obvious rough spongy surfaces with an average particle size of less than 150 nm. The addition of Co3O4 into Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I improves the shape of the particles to mainly rod shapes that are arranged in different directions (Figure 3c) with an average length between 100 and 400 nm and thickness of less than 50 nm. A further increase in the Co3O4 content decreases the particle sizes without affecting their shapes and arrangement but increases the thickness to less than 100 nm. This could result in reduction in the specific surface area for adsorption of pollutants as reported elsewhere.42 However, the aggregation in the nanomaterials slightly increases (Figure 3d). However, it is very difficult to obtain the interaction between Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I and Co3O4 as the composites had similar shapes and sizes that are difficult to index to any of them selectively.

Figure 3.

SEM images of (a) Co3O4, (b) Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I, (c) CB2, and (d) CB5.

The elemental composition of the nanocomposites was evaluated by EDS analysis to check the present elements (Figure 4). In all the synthesized semiconductors, carbon was present from the carbon coating and stabs. Figure 4a confirms the presence of peaks due to Co, O, and C observed with weight proportions of 62.0, 23.4, and 14.6%, respectively, in the synthesized Co3O4. The EDS spectrum of Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I showed peaks due to C, O, I, and Bi with weight percentages of 18.7, 6.2, 15.5, and 59.6%, respectively (Figure 4b). All the peaks due to individual atoms observed in the pristine materials were also observed in the composite confirming that indeed Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I and Co3O4 coexisted (Figure 4c,d). The weight compositions of C, O, Co, I, and Bi in the composites were 18.9, 12.6, 22.1, 7.2, and 39.2% and 9.0, 15.1, 26.4, 10.3, and 39.2% for CB2 and CB5, respectively.

Figure 4.

EDS images of (a) Co3O4, (b) Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I, (c) CB2, and (d) CB5.

The elemental weight compositions of the analyzed nanomaterials agreed with the precursor ratios used during synthesis.

2.4. TEM

The morphology of the synthesized CB2 was analyzed with TEM to better determine the arrangement of the nanomaterials that make up the photocatalyst in the composite. Figure 5a shows that the rod-shaped materials were indeed arranged in different directions with different sizes that are like particles spread on a sheet that are more broad toward the edges of the composite. The rod-shaped morphology of the CB2 composite aggregates into sheets as inspected carefully under high magnification (Figure 5b). This observed morphology, which is normally abundant in bismuth-based composites, was determined to be important in enhancing the adsorption of pollutants on the photocatalyst surface and structural stability, which are important for enhanced photocatalytic degradation activity.43 HR-TEM images of the composite in Figure 5c shows that the 511 exposed facets of the Co3O4 composite are scattered inside the exposed 411 facets of Bi4O5I2 and the Bi5O7I multiple 312 and 204 exposed facets. The exposure of multiple facets of Bi5O7I can result in synergistic photocatalytic activity as reported elsewhere in that the eminent boundaries among the lattice fringes of different components are evidently designated to the heterojunction formation that is expected to enhance photogenerated charge separation and improve photoactivity.18 Therefore, it can be inferred that a heterojunction was formed between Bi4O5I2, Bi5O7I, and Co3O4 as proposed.

Figure 5.

(a, b) TEM, (c) HR-TEM, (d) SAED images of CB2.

The SAED pattern of the synthesized composite proved that it is highly crystalline despite the addition of Co3O4 not having any influence on the general crystallographic structure of the synthesized Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I.

2.5. BET

The specific surface area is an important parameter in heterogeneous photocatalysts as it can directly affect their activity. Therefore, the BET surface areas of the synthesized Co3O4, Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I, and CB2 were investigated by nitrogen adsorption–desorption. Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I and CB2 displayed type II isotherms with hysteresis loops that started from a relative pressure of approximately 0.6, and the weak adsorption–desorption hysteresis designated a monolayer absorption (Figure 6a). The hysteresis loops are classified as type H3 according to IUPAC, which are a result of pores between analogous sheets in agreement with their morphology as investigated by FE-SEM and TEM. On the contrary, Co3O4 displayed a type II isotherm that is a result of a nonporous or macroporous material as confirmed by its pore size distribution (Figure 6b). The BET surface areas of Co3O4, Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I, and CB2 are 18.63, 24.08, and 32.7 m2 g–1, respectively. The average pore sizes of Co3O4, Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I, and CB2 are between 20 and 80 nm with an average pore size distribution of approximately 47 nm (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

(a) Nitrogen adsorption–desorption and (b) pore size distribution of Co3O4, Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I, and CB2.

Co3O4 can be classified as a non-porous material with pores of approximately 80 nm believed to be due to spaces between compact and stacked irregular shapes between aggregates. A 35.8% increase in the surface area of CB2 compared to Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I could be attributed to the less aggregation that was observed, which also increased the pore volume. This increased surface area can hardly be the only driving force for removal of the pollutants, and other contributions are a result of other properties such as the optical properties and morphology, which impact photocatalytic degradation of pollutants. The pore volumes of Co3O4, Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I, and CB2 are 0.0163, 0.0487, and 0.0572 cm3 g–1, respectively. The increase in the pore volume of CB2 compared to Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I was directly proportional to the increase in the surface area.

2.6. Optical Properties

Irradiation conditions (photon energy and flux) and optical absorption properties of the photocatalyst (band gap, size, and surface area) affect the electron–hole pair (EHP) regeneration rate, and the fate of the EHPs control the catalytic reactions on the surface or within the photocatalyst.44 EHP recombination occurs if the carrier diffusion time to the surface is longer than the electron–hole recombination time.45,46 Therefore, photoluminescence spectra of materials are important to understand the EHP recombination rate. Figure 7a shows the PL spectra of selected composites. There are two bands that are distinctive on the PL spectra of Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I showing that this material emits different energies that can be a result of degenerate transitions that occur during excitation and it has the highest intensity. Ultraviolet emission peaks in bismuth (Bi) photocatalysts were reported to occur due to recombination of excited electrons in the conduction band to a crystal defect-induced surface and interface states or energy levels of deep traps while the corresponding visible region emissions were attributed to electrovalency arising from different intra s–p transitions of Bi ions.47 Therefore, it can be concluded that the Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I heterojunction was formed with crystal defects that could not be changed by addition of Co3O4 to form the C-scheme heterojunction. The addition of 10 mg of Co3O4 to form CB1 reduced the intensity of both peaks, and the addition of 20 mg of Co3O4 to form CB2 results in the lowest intensity. However, the PL intensity of CB5 when the amount of Co3O4 was increased to 50 mg surpassed that of the other composites. In all the composites with different amounts of Co3O4, the PL intensity peaks were quenched due to the occurrence of an effective photo-induced charge separation or energy transmission on the interface between Co3O4 and Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I. The efficiency of the interface energy transfer (E) can be estimated from eq 1.48

| 1 |

where FD is the PL intensity of Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I without Co3O4 and FDA is the PL intensity of Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I in the presence of different ratios of Co3O4. The values of E for CB1, CB2, and CB3 were 73.47, 86.65, and 69.18%, respectively. Therefore, the energy transfer at the interface reaches a maximum in the CB2 composite. The intensity in a PL spectrum is fundamental in two ways as it shows reduction in electron–hole pairs, which can suggest the formation of a heterojunction for a mixture of semiconductors and doping when ions are added to a semiconductor.47 The decrease in intensities of CB1, CB2, and CB5 confirms the reduction in the recombination rate of charge carriers, which could affirm that a heterojunction formed with the effect optimum in CB2 as confirmed by the interface energy transfer.

Figure 7.

(a) PL, (b) UV–vis, and (c, d) band gaps of Co3O4, Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I, CB1, CB2, and CB5.

The efficiency of a photocatalyst is determined by the number of reactions initiated by captivation of a photon.49 Meanwhile, photon absorption depends on properties related to photo-excited EHPs like their regeneration rates, energy levels, and rates of migration.50−53 UV–vis DRS of the materials was performed to understand the energy requirement of each material and obtain their band gaps. The absorption edge of the Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I composite, which is around 470.1 nm was shifted more to the visible range of the solar spectrum by addition of Co3O4, which had two distinctive absorption maxima wavelengths around 350 and 650 nm due to transitions from the highest occupied molecular p orbitals of oxygen to the empty d orbitals of Co2+ or Co3+ in the spinel structure. Interestingly, all the synthesized composites (CB1, CB2, and CB5) followed a similar trend to Co3O4 suggesting that they have a strong absorption coefficient throughout the solar spectrum in the analyzed range (200–800 nm). The optical band gap energy (Eg) of semiconductors is important to quantify the amount of energy required and determine whether they can be activated by UV, vis, or NIR energy. The band gap energies are estimated by eq 2.54

| 2 |

where A, ν, α, and Eg are a constant based on the properties of the semiconductor, the light frequency, the absorption coefficient, and the band gap, respectively. The absorption coefficient α is a measure of the substantial energy that is necessary to generate EHPs, and its inverse (α–1) is important in estimation of the distance traveled by a photon before it gets absorbed; the value of α–1 for CB2 is 0.7359 nm/m2. However, n is governed by the characteristic transitions that occur in a semiconductor, i.e., direct transition (n = 1) or indirect transition (n = 4). The n value for all the synthesized nanomaterials fitted both direct and indirect transitions, and the indirect transitions’ band gap energy values are displayed (Figure 7c,d). When extrapolating to x = 0 from a plot of (αhν)2 versus photon energy (hν), the estimated band gap energies are 1.68, 2.64, 1.78, 1.91, and 1.98 eV for Co3O4, Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I, CB1, CB2, and CB5, respectively. The band gap of Co3O4 is similar to what is already reported in the literature.55 There was an observed decrease in the band gap energies of the nanocomposites compared to Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I upon addition of Co3O4 that increased directly with an increasing amount of Co3O4 from CB1 to CB5. Therefore, from the optical properties’ analysis, it can be concluded that the high photocatalytic activity of the CB2 composite (compared to CB1 and CB5) was a combination of morphology and improved photoexcited EHP separation and there was no direct relationship to the band gap energies.

2.7. Degradation

The photocatalytic activity of the fabricated Co3O4/Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I C-scheme heterostructure was explored for the degradation of p-nitrophenol (PNP) and brilliant black dye (BB) under visible light irradiation. The UV–vis spectra of the degradation processes are displayed in Figure 8. Degradation efficiencies of 99.3 and 91.6% were achieved for PNP in 120 min and BB in 180 min when using CB2 composite under optimum conditions, respectively. The characteristic absorbance peak of PNP at 319 nm decreased with increasing illumination time as expected (Figure 8a), while the BB peak at 573 nm was quenched as time progressed to 180 min under visible light (Figure 8b). Therefore, the synthesized heterostructure accomplished high degradation efficiencies for the photocatalytic degradation of PNP and BB, which were attributed to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROSs) that break down the chromophores of the corresponding organic pollutants into smaller molecules.

Figure 8.

UV–vis absorption for degradation of (a) p-nitrophenol at pH 9.6 (catalyst dosage of 40 mg, degrading 25 ppm of 50 mL solution) after 120 min and (b) brilliant black at pH 5.3 (catalyst dosage of 40 mg, degrading 15 ppm of 50 mL solution) for 180 min.

The optimum conditions toward degradation of PNP and BB were different, and optimizations were performed for each pollutant to achieve high photoactivity. Figure 9a–f shows the results obtained during degradation of PNP. Different amounts of the CB2 photocatalyst were used to degrade 25 ppm of the pollutant to obtain the optimum amount necessary for degradation of PNP. The efficiencies of 10, 20, 30 and 40 mg were determined to be 46.19, 75.34, 90.83, and 56.68%, respectively (Figure 9a). The efficiency increased with the increasing catalyst amount due to an increased generation of reactive species, increased specific surface area for the catalyst and PNP interaction, and increased available photoactive sites to an optimum value of 30 mg, and a further increase to 40 mg resulted in reduced photocatalytic activity due to light shielding effects. Different concentrations of PNP were tested, and the photocatalytic activity increased with decreasing concentration such that 40, 25, and 10 ppm gave efficiencies of 63.12, 90.83, and 97.99%, respectively (Figure 9b). The increase is inversely proportional to the molecules that are present in the solution during the photodegradation process. All the composites were used together with photolysis experiments using the optimum amount and concentration of 25 ppm, and the respective efficiencies for photolysis, Co3O4, Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I, CB1, CB2 and CB5 were 13.97, 28.97, 55.96, 73.17, 90.83, and 41.11% (Figure 9c). The low efficiency of photolysis can be ignored, and the efficiency of Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I was higher than that of CB5 suggesting that the optimum value of the composite is obtained at 20 mg of Co3O4 to form CB2. The photolysis efficiency is low as PNP has two peaks and the source of light used could only be absorbed due to the presence of the peak with a maximum intensity around 425 nm. The photocatalytic degradation of PNP was assessed with the Langmuir–Hinshelwood first-order kinetics model (ln(C0/Ct) = Kappt)56 where the slope of a plot of ln(C0/Ct) versus time (t) gives the apparent rate of constant Kapp. The corresponding rate constants for photolysis, Co3O4, Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I, CB1, CB2, and CB5 were 0.00126, 0.00276, 0.00686, 0.01112, 0.0199, and 0.00425 min–1 (Figure 9e). The synergy factor (R), which determines the beneficial effect of Co3O4 on Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I, can be deduced from the respective rate constants of the photocatalysts by eq 3.48

| 3 |

Figure 9.

Optimization of the (a) catalyst amount and (b) concentration of p-nitrophenol using the CB2 composite, (c) optimization of the catalyst composition, (d) pH of the solution, and (e) corresponding reaction rates for different catalyst compositions, and (f) TOC results at pH 9.6 (catalyst dosage of 40 mg, degrading 25 ppm of 50 mL PNP solution) after 120 min.

The synergy factor for CB2 was determined to be 2.0686 for p-nitrophenol degradation, which proved that indeed the synergistic interaction between the composites occurred, which enhanced photodegradation activity. The synergy factor was higher than some previously reported values48 and could also be proposed to be the key factor for the mineralization efficiency of the composites and their corresponding rate constants under visible-light irradiation. However, it is difficult to independently and solely conduct comparisons of results from different studies with the synergy factor because the kinetic parameters are obtained in relation to specific experimental conditions such as the area of the irradiated photocatalyst, reaction volume, design of the used reactor, type and intensity of light, and catalyst weight.57 For example, similar photocatalysts of RGO-ZnTe yielded different synergy factors but accomplished degradation in 35 min (using different pollutants) with the synergy high where the conditions did not allow for evaluation of RGO degradation efficiency.58,59 Therefore, the approach used to evaluate synergy factors should be examined carefully and appropriately to minimize errors.

The pH of a solution is an important aspect of photocatalytic reactions in aqueous media, and changes in the pH result in increased, decreased, or unchanged photoactivity. pH values of 3.7, 5.8, 7.5, 9.6, and 11.2 gave efficiencies of 38.91, 61.55, 90.83, 99.27, and 80.01% respectively (Figure 9d). Therefore, the optimum pH was determined to be pH 9.6 for PNP degradation as it resulted in rapid photoactivity. The degradation of PNP under different pH conditions can be understood from its pKa value of 7.15 (Figure 11c) such that, below 7.15, the PNP molecule is neutral and interacts poorly with the catalyst, and the low pH value of 5.8 and 3.7 gave less photoactivity. However, at pH 7.5, PNP has dissociated to its corresponding Lewis base and there is a strong electrostatic interaction with the positively charged catalyst surface resulting in high photocatalytic activity.

Figure 11.

(a) Adsorption of brilliant black and p-nitrophenol, (b) the corresponding pseudo-second-order rate constants, (c) formation of the conjugate Lewis base of PNP, and (d) determination of point of zero charge of CB2.

Further addition of OH– ions to increase the pH to 9.6 enhances the formation of OH radicals and improves the photocatalytic degradation of PNP. However, as the pH increased to 11.2, the efficiency was retarded, and it could be suggested that two factors are responsible for the decrease in efficiency. First, the negatively charged OH– anions could be competing with the negatively charged PNP Lewis base on the photocatalytic active sites. In addition, there is a high possibility as determined by Xiong et al.60 that the OH anion, which is expected to form H2O2 that can be transformed to OH radicals under irradiation (eqs 4 and 5), scavenges the generated OH radicals as generalized in eqs 6 and 7.61,62

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

The degradation of PNP was performed under optimum conditions to determine the degree of carbon mineralization using the total organic carbon (TOC), and the efficiency obtained was 93.63% (Figure 9f). Therefore, the C-scheme heterojunction of BC2 resulted in high mineralization of p-nitrophenol that could be indexed to ring opening of the benzyl skeleton and subsequent mineralization into organic acids, water, and carbon dioxide.

Using the same amount of the catalyst, 30 mg, different concentrations of brilliant black dye (BB) were degraded, and their efficiency increased with a decrease in concentration like in PNP degradation. The increase could be attributed to the little molecules available in solution that would be adsorbed and degraded at a faster rate than when there are more molecules. The efficiencies for 20, 15, and 10 ppm were determined to be 63.21, 91.57, and 98.68%, respectively (Figure 10a). The obtained efficiencies were very high, and pH optimization was conducted with a 20 ppm concentration with efficiencies of 91.57, 61.29, and 45.2% at pH 5.3, 7.5, and 10.2 (Figure 10b), respectively. Therefore, the optimum pH was determined to be 5.3 for BB. This could be due to the presence of the sulfonic auxochromes that are on the edges of BB to increase its reactivity in that it would get easily protonated and result in an enhanced interaction between the dye and positively charged photocatalyst surface to result in high photocatalytic activity. The corresponding rates were determined to be 0.00328, 0.00535, and 0.01318 min–1 at pH 10.2, 7.5, and 5.3 (Figure 10c). Despite the rate constants being determined after optimum conditions for BB, the photodegradation rate was slow compared to PNP, which could also be seen from the respective times taken to reach complete degradation (120 and 180 for PNP and BB, respectively). This could result from the complex structure of BB compared to PNP as it consists of numerous characteristic bonds and a network of benzyl skeletons. Figure 10d shows the TOC removal obtained during degradation of brilliant black. There was an 83.7% removal efficiency, which suggested that there was residual carbon content left after degradation of brilliant black as it got converted to aliphatic compounds, water, and carbon dioxide.

Figure 10.

Optimization of the (a) concentration of brilliant black, (b) pH of the solution, and (c) corresponding rate constants at different pH values and (d) TOC removal of brilliant black dye at pH 5.3 (catalyst dosage of 40 mg, degrading 15 ppm of 50 mL BB solution) for 180 min.

The other parameter that affects photoactivity is the adsorption of pollutants. The adsorption of pollutants on photocatalytic active sites is important to pioneer degradation such that a poor interaction between the photocatalyst surface and the pollutant can retard photoactivity. However, it is undesirable for adsorption to be the main mechanism involved in removal of the pollutant such that its effect surpasses that of photocatalysis due to the high surface area. The adsorption of PNP and BB were evaluated for 1 h (Figure 11a). The quantity of PNP and BB adsorbed (qt) by a unit mass of the catalyst (W) was estimated from the mass balance equation of qt = (C0 – Ct)V/W] where C0 and Ct are the initial and residual concentrations of pollutants and V is the solution volume.63 It can be seen that adsorption of PNP was more than that of BB but they both reached adsorption–desorption equilibrium after 30 min. It could be quantified that adsorption of PNP and BB contributed between 10 and 15% of the overall pollutant removal efficiency. Therefore, it could be inferred that the main mechanism for removal of the selected organic pollutants was photodegradation from reactive oxygen species (ROSs) generated by the CB2 nanocatalyst. The obtained data was evaluated with pseudo-first-order (ln(Qe – Qt) = lnQe – K1t) and pseudo-second-order (t/Qt = 1/K2Qe + t/Qe) kinetic models64 where Qt and Qe is the amount of pollutant adsorbed at a specific time and at equilibrium with the corresponding rate constants K1 (min–1) for pseudo first order and K2 (min–1) for pseudo second order. The obtained respective values of the correlation coefficient for PNP and BB for first-order and second-order reactions were R2 = 0.3084 and R2 = 0.5622 and R2 = 0.97528 and R2 = 0.98921, respectively, signifying that their adsorption followed the pseudo second-order kinetics model experimentally (Figure 11b). The obtained results agreed with some theoretical outcomes on degradation of organic pollutants.65,66

Thermodynamic parameters that were evaluated include the changes in enthalpy (ΔH*), Arrhenius activation energy (EA), changes in entropy (ΔS*), and Gibbs free energy (ΔG*) to understand the thermodynamic behavior of the pollutant adsorption on the CB2 composite at temperatures of 29.7 ± 0.1 and 50.1 ± 0.1 °C. The thermodynamics adsorption of PNP and BB on CB2 was studied to elucidate the involved mechanism for 25 and 20 ppm, respectively. The values of EA for BB and PNP were 19.86 and 11.93 kJ mol–1, which explicitly demonstrated that their adsorption was chemisorption in nature instead of physisorption, which normally has a magnitude below 4.184 kJ mol–1.63 These results further support the FTIR results where the interaction is proposed to be pioneered by the presence of the C=O functional groups on the composite. ΔH* values (9.67 and 16.99 kJ mol–1) were positive and suggested that adsorption of PNP and BB was endothermic while the negative ΔS* values (−0.048 and – 0.08 kJ mol–1 K–1) supported the hypothesized interaction between the adsorbant and pollutants that occurred. Moreover, the fact of positively charged catalytic active sites having high affinity toward the pollutants at pH values above a point of zero charge of 4.5 (Figure 11d) was confirmed and it could also be inferred that no significant changes occurred to the internal structure of the adsorbing catalyst during adsorption as reported elsewhere.67−69 The point of zero charge shows that, below pH 4.5, the catalytic surface is negatively charged and becomes positively charged when the pH of pollutant solution is above 4.5. The isoelectric point of zero charge has been used successfully to predict the charges of different catalysts with respect to pH changes.70−72 Lastly, the positive ΔG* (27.68 kJ mol–1) obtained demonstrated the non-spontaneous nature of the adsorption process that could be pioneered by external energy sources such as (mechanical stirring) to enhance the efficiency of the process as it has been proven that ΔG* = 0, ΔG* < 0, and ΔG* > 0 for equilibrium, exergonic, and endergonic processes, respectively.68 Despite the thermodynamic properties of the adsorption process, the main mechanism involved in the removal of pollutants was photodegradation as adsorption was responsible for removal of less than 16% of the pollutant molecules.

The degradation of both BB and PNP was performed with the reused catalyst to conduct repeatability tests and characteristics of the used composites for PNP degradation were characterized with XRD and FE-SEM (Figure 12). The degradation of BB was performed with stability up to 4 cycles with efficiencies of 91.57, 89.97, 85.03, and 80.02% (Figure 12b), while the efficiencies for degradation of PNP were 99.3, 98.9, 94.5, 89.9, 86.3, and 79.8% (Figure 12a) in 7 cycles. The photostability of semiconductors is important toward their commercialization and efforts should be made to understand their behavior after use. Many different spectroscopic and analytical or surface techniques are normally employed such as FTIR, TEM, TGA, and XPS to mention a few.73−75

Figure 12.

Repeatability tests of (a) PNP and (b) BB degradation, (c) XRD comparison before and after degradation of PNP, and (d) SEM image of the recycled CB2 composite.

Crystallographic and phase composition changes are normally evaluated with XRD and the comparison of the spectra of CB2 before and after 7 photocatalytic cycles of PNP degradation is presented (Figure 12c). The peak positions did not change, which suggested that the phase was not changed as also there is no emergence of new peaks and the materials maintained their crystalline structure with a major decrease in the intensity of the peaks after reuse. The absence of the new peaks appearing after catalyst reuse (especially for carbon-based materials) is important to confirm the desorption of the pollutant and intermediates on the catalyst surface. The decrease in the XRD peak intensity can be understood by evaluation of the surface morphology of the materials, which proved that the photocatalyst morphology changed after reuse with more changes observed along the edges (Figure 12d). The shapes and sizes of the CB2 nanocatalyst changed after reuse, which could be attributed to photocatalyst fouling that was reported to retard photocatalytic activity by blocking surface active sites.73,76 Moreover, understanding the mechanisms that are necessary for photocatalyst regeneration is very important, but such processes were outside the scope of this work and have been explained in detail elsewhere.73

2.8. Radical Trapping Experiments

The mechanisms involved in semiconductor photodegradation of organic pollutants have been generalized into photolysis, dye photosensitization, and photocatalysis.77,77 In photolysis and dye sensitization, the formation of a single oxygen atom that acts as an oxidant of the pollutant is initiated by absorption of a photon by an electron of the pollutant. As observed during photolysis experiments conducted during degradation of PNP and BB, the effect of photolysis was negligible signaling the structural stability of the investigated pollutants under visible light.

The carrier type is an important parameter in the design and understanding of photocatalytic properties of heterojunctions, and it is studied using scavengers of holes, hydroxyl radicals, and superoxide anion radicals. Different scavengers have been employed for numerous applications.16,78 Interestingly, the role of the active species determined during the different investigations has proved that the involved reactive species during photocatalytic activities differ with respect to different parameters irrespective of whether the pollutant is the same; hence, their evaluation is important in every system. For example, Salimi et al. demonstrated that the superoxide radical played a major role and holes and hydroxyl radicals played a minor role as active species,77 while Serpone et al. determined that the superoxide radical is the major active species whereas the OH radical and 1O2 are the minor ones79 both in the degradation of crystal violet (CV). Benzoquinone (BQ, 3 mmol), ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA, 2 mmol), and tert-butanol (t-BuOH, 2 mmol) were employed in this study as scavengers for superoxide, holes, and hydroxyl radicals, respectively (Figure 13). OH radicals were determined to be the main reactive species for degradation of both PNP and BB followed by h+ and the O2– radical. This order can be attributed to the high generation of OH radicals from the selected semiconductors and is consistent with results determined elsewhere for main species involved in heterojunctions of bismuth oxyiodides.,2477 Moreover, even if the quantity of generated OH radicals is low compared to other ROSs, their robustness and capability to non-selectively mineralize several pollutants may have resulted in them being the main reactive species as reported elsewhere.79

Figure 13.

Radical scavenger experiments for (a) p-nitrophenol and (b) brilliant black.

The reported efficiencies of reduction when using BQ, EDTA, and t-BuOH are 78.7, 57.9, and 32.3% and 67.5, 48.9, and 33.1% for PNP (Figure 13a) and BB (Figure 13b) respectively.

2.9. Deduction of the Photocatalytic Mechanism

Band positions are important in indicating the thermodynamic restrictions of the photoreactions that can be induced by charge carriers when evaluating heterojunctions formed by photocatalysts.80,81 Different strategies that have been employed to determine the valence band maximum and the conduction band minimum energy levels of semiconductors range from evaluations with analytical techniques (UPS, etc.)82,83 and estimations based on already proved theories and valuations such as density functional theory (DFT).84−86 Based on studies16,77 and the results obtained in this report, the photocatalytic degradation mechanism involved in degradation of PNP and BB was evaluated with estimations that involve the Mulliken electronegativity theory, which gives the geometric mean of individual atom electronegativities in a semiconductor.84 Visible-light irradiation of the CB2 nanocomposite will cause photoexcited electrons and holes in Bi4O5I2, Bi5O7I, and Co3O4 since they can absorb light in the visible range of the solar spectrum due to their low band gaps. The Bi4O5I2 and Co3O4 p-type semiconductors have their Fermi level energy close to the valence band, while that of n-type Bi5O7I is close to its conduction band. The valence band edge potential of the semiconductors can be estimated from their band gaps (Eg), the electronegativity (X), and the energy of free electrons versus a normal hydrogen electrode (NHE) (Ee = 4.5 eV) by eqs 8 and 9.85

| 8 |

| 9 |

The electronegativity of a semiconductor with a number of a and b compounds of A and B, respectively, can be obtained from eq 10.31,85

| 10 |

The values of X were 5.06, 6.175, and 6.06 eV, while the Eg values for Bi4O5I2, Bi5O7I, and Co3O4 were determined to be 2.28, 2.79, and 1.68 eV, respectively. The energies of valence bands are +1.7, +3.07, and + 2.4 eV, and the conduction band potentials were −0.54, +0.28, and +0.54 eV for Bi4O5I2, Bi5O7I, and Co3O4, respectively.

Bi4O5I2, Bi5O7I, and Co3O4 would align such that their Fermi level energies reach equilibrium, and when at equilibrium, if a standard type II heterojunction was formed (Figure 14a), electrons will migrate from the conduction band of Bi4O5I2 to that of Bi5O7I and eventually concentrate on the conduction band of Co3O4.

Figure 14.

(a) Type II heterojunction and (b) hybrid type II and Z-scheme heterojunction formation between Co3O4, Bi4O5I2, and Bi5O7I.

This is unlikely to occur as the electrons on the conduction band of Co3O4 with a band edge potential of +0.5 eV (as per the synthesized materials) would not result in the generation of superoxide anion radicals. Moreover, holes would also move from the valence band of Bi5O7I to that of Co3O4 and concentrate on the valence band of Bi4O5I2. If this happened, there would be no generation of hydroxyl radicals as the valence band edge potential of +1.7 eV would possess a less positive potential versus an NHE than the required minimum of +1.99 eV for generation of this ROS,85,86 as also confirmed in a study by Li et al. with a p–n–p heterojunction involving bismuth oxyiodides.86 However, the superoxide anion radicals and hydroxyl radicals are formed as proven by radical quenching experiments, which nullified the possibility of a standard p–n–p heterojunction formation in this study. The other possibility would be for a hybrid Z-scheme heterojunction formation that would result in the electrons from excited-state Bi4O5I2 being left as they are since they possess enough negative conduction band-edge potential that can trigger the formation of ·O2– from O2. If this were to happen, in order to result in the observed reduction in recombination of photoexcited electrons and holes in the composite compared to the formed Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I, the electrons in the conduction band of Co3O4 would recombine with holes in the conduction band of Bi4O5I2. This would mean that electrons in the conduction band of Bi5O7I migrated to the conduction band of Co3O4 and recombined with holes in the conduction band such that a hybrid type-II and Z-scheme heterojunction is formed (Figure 14b). If this happened, it would be difficult to explain the involvement of the OH radicals as the main reactive species toward the degradation of the selected pollutants. This stems from the fact that the holes will concentrate on the valence band of Co3O4 with a potential of (+2.4 eV) as illustrated in Figure 14 b to convert OH– to OH radicals as detailed in other studies.87 However, the existence of the C-scheme heterojunction should be confirmed with other techniques as the formation of one ROS often leads to the existence of others as reported elsewhere during fabrication of bismuth oxyiodide-containing composites.40 Interestingly, as with the proposed C-scheme heterojunctions, other heterojunctions that are novel and yet to be completely understood have been reported by other authors.88 The proposed charge transfer in the p–n–p heterojunction of Bi4O5I2, Bi5O7I, and Co3O4 in the CB2 nanocomposite is generalized in Figure 15, and it is proposed to be called the C-scheme heterojunction. The reactions that are involved in the formation of the generated ROS due to photoexcited charge carriers are summarized in eqs 11–16.

Figure 15.

Proposed charge transfer and reaction mechanism.–

| 11 |

| 12 |

| 13 |

| 14 |

If the proposed C-scheme heterojunction forms (Figure 15), the excited electrons in the conduction band of Bi5O7I transfer to the conduction band of Co3O4. It was proved that, for a standard p–n heterojunction establishment, the shift in the Fermi level energies to reach equilibrium results in shifts in the band edge positions from their positions to a visual staggered band alignment.89−91 This alignment is expected to result in a more negative conduction band edge position in Bi4O5I2 and a more positive valence band maxima in Bi5O7I increasing their ability to reduce oxygen to superoxide anion radicals and to oxidize OH– to OH radicals, respectively. The proximity of the conduction band of Bi5O7I to that of Co3O4 favors the electron transfer kinetics from a higher energy level (Bi5O7I) to a low energy level (Co3O4). The electrons concentrate on the conduction band of Co3O4, reduce adsorbed H2O to form OH radicals, and increase the rate of formation of non-selective OH· toward mineralization of adsorbed pollutants. The results were further confirmed by the radical trapping experiments where OH· was determined as the main reactive oxygen species. The holes on the valence band of Bi5O7I can convert OH– into OH· such that the recombination of photoexcited electrons and holes is reduced. This finding would be similar to a study determined by Dong et al.16 in that Bi5O7I has the capability to generate OH·. Alternatively, the holes on the valence band of Co3O4 will migrate and concentrate on the valence band of Bi4O5I2 where they will directly oxidize the pollutants. When electrons in Bi4O5I2 reach its conduction band minimum, they have enough negative potential (−0.54 eV) to convert adsorbed oxygen to a superoxide anion radical (O2/*O2– = −0.33 eV) enhancing separation of photogenerated charge carriers. This ability can be enhanced by the staggered band alignment, which is proposed to increase the conduction band energy level of Bi4O5I2.

The novel C-Scheme Co3O4/Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I nano-heterojunction exhibits excellent photocatalytic degradation under visible light with a new direction proposed for enhancement in separation of photoexcited electron and hole recombination. This heterostructure was named C-scheme as the transfer of photoexcited charges made a C-like motion for enhanced separation and high photoactivity. The thermodynamics of the proposed C-scheme was closely related to that of Z-scheme and R-scheme heterojunctions that have been confirmed. Therefore, it is important to understand that, since Co3O4 has oxidative capabilities, it will increase the generation of the non-selective hydroxyl radicals toward degradation of the selected pollutants. Bi5O7I would also contribute toward the generation of more non-selective hydroxyl radicals, while Bi4O5I2 would result in an enhanced generation of superoxide anion radicals. The overall result of their combination is a successful generation of different ROSs that synergistically contributes to rapid degradation of organic pollutants.

The proposed C-scheme heterojunction would add in advancement of knowledge in the formation of heterojunctions to the numerous obtained heterojunctions such as p–n, direct, and indirect Z-schemes that were unveiled and proposed as evaluations were performed to deliberate on the mechanisms involved in combination of two or more semiconductors to enhance the probability of large-scale applications of advanced oxidation processes using photocatalytic materials.

3. Conclusions

Novel nanocomposites of Co3O4, Bi4O5I2, and Bi5O7I with high photocatalytic activity for degradation of p-nitrophenol and brilliant black were fabricated. The formed heterojunction was proven with PL analysis and HR-TEM images where the former also confirmed reduction in charge recombination and the latter also confirmed Bi5O7I multi-facet exposure in CB2. The highest photocatalytic activity was observed from the CB2 composite with an efficiency of 99.3% in 120 min for degradation of p-nitrophenol at pH 9.6 and 91.57% within 180 min for degradation of brilliant black at pH 5.3. The enhanced photoactivity was attributed to facet engineering, high specific surface areas, strong absorption of visible light, and a pH-induced strong interaction between pollutants and positive catalytic active sites. The C-scheme heterojunction photocatalyst can be employed for mineralization of different classes of organic pollutants under suitable pH conditions to enhance water re-use for different applications. Moreover, it can be applied for CO2 conversion to minimize global warming effects.

4. Methodology

4.1. Materials and Synthesis

All materials used in this study were of analytical grade and used as purchased without purification. Benzoquinone (BQ, ≥98%), bismuth nitrate hexahydrate (Bi(NO3)2·5H2O, 99%), brilliant black (BB, 45%), cobalt(II) acetate dihydrate (Co(AOC)2·2H2O, 99%), ethylene glycol (98%), ethanol (EtOH, 98.9%), methanol (CH3CH2OH, 99%), p-nitrophenol (PNP, 97.6%), potassium iodide (KI, 98%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 99.8%), sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 98%), and tert-butanol (t-BuOH, 99.9%) were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich, (South Africa). Ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid sodium salt (EDTA, 98.5%) was procured from SAARCHEM (South Africa). Distilled water was used to prepare all solutions.

Co3O4 nanoparticles were obtained by thermal decomposition of cobalt acetate dihydride. A qualitative amount of cobalt acetate was placed in a crucible without a lid, and the heating rate was set at 5 °C min–1 to a maximum temperature of 450 °C where it was calcined for 4 h. The obtained dark gray solid was washed three times with ethanol followed by deionized water to remove unreacted ions by centrifugation. The solid was then dried in an oven at 90 °C for 12 h and stored for further use.

4.1.1. Synthesis of Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I

A composite of Bi4O4I2/Bi5O7I was synthesized through the microwave-assisted precipitation method by first synthesizing bismuth oxyiodide. Then, 8 mmol of bismuth nitrate hexahydrate was dissolved in 40 mL of ethylene glycol to a clear solution (A), and 8 mmol of potassium iodide was dissolved in an equivalent amount of ethylene glycol (40 mL) to form solution B that was added (dropwise) under magnetic agitation at room temperature and allowed to react for 24 h. The solution was placed in a microwave chemical reactor (SynthWAVE single-reaction chamber microwave synthesis system with magnetic stirrer and water-cooled condenser) for 20 min (temperature = 160 °C, power = 1000 W, and pressure = 170 bar). The solution was cooled to room temperature and centrifuged to obtain a yellowish precipitate of BiOI. The obtained BiOI was rinsed successively with deionized water and ethanol then dried at 90 °C for 8 h before it was calcined at 450 °C for 1 h at a heating rate of 10 °C per min to obtain a mixture of Bi4O5I2 and Bi5O7I. This calcination temperature was selected based on the synthesis of Bi4O5I2 from BiOI through controlling the calcination temperature where it was determined that, at around 410 °C, all BiOI is converted to Bi4O5I2.24,41 Here, it is determined that, as the temperature increases to 450 °C, a mixture of both Bi4O5I2 and Bi5O7I exists with the major component being Bi5O7I. The transformations are generalized by eqs 15 and 16:

| 15 |

| 16 |

As the calcination temperature progressed from 410 to 450 °C, eqs 15 and 16 occurred simultaneously such that, at 450 °C, both Bi4O5I2 and Bi5O7I exist. Moreover, all these transformations are catalyzed by external heat energy and some reports where BiOI transformed into Bi5O7I ((5/2)BiOI + (1/2)O2 → Bi5O7I + I2) at 500 °C exist.25 Therefore, it is important to carefully select the different parameters toward the formation of the expected products as reactions occur differently based on different parameters during synthesis. The importance of the calcination method (over a pH-controlled method) is the prospect for preparation of pure nanoparticles provided that the precursor BiOI is pure.

4.1.2. Synthesis of Ternary Composite

The Co3O4/Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I ternary composite was synthesized by mixing 0.5064 g of Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I and different amounts of Co3O4 (10, 20, and 50 mg) in a 250 mL solution of 30% (v/v) methanol at room temperature for 8 h. The solution was centrifuged to collect the solid that was washed three times with deionized water then ethanol before being dried in an oven at 80 °C for 6 h. The obtained composite was calcined at 350 °C for 2 h. The synthesis method is generalized in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Co3O4, Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I and Co3O4/Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I.

The composites were labeled as CB1, CB2, and CB5 for 10, 20, and 50 mg of Co3O4, respectively.

4.2. Equipment

Absorption properties of the synthesized nanomaterials were obtained from a PerkinElmer UV/Vis spectrometer Lambda 650 (South, Africa) to calculate their band gap energies using a reference of BaSO4. The photoluminescence results were attained from a HORIBA Flourolog 3 (FL-1057, South Africa) that uses a 450 W xenon lamp for excitation, and the signals were detected on an S1-PMT detector. The excitation wavelength was 320 nm, and the scanning range selected was between 350 and 600 nm. XRD was done with a Rigaku SmartLab X-ray diffractometer (South Africa) that is equipped with a Cu Kα X-ray wavelength radiation of 1.5418 Å and a current and voltage of 200 mA and 45 kV, respectively. The patterns were recorded from 2θ of 5 to 90°. TOC measurements were performed with a TOC-VWP total organic carbon analyzer (SHIMADZU, Japan). The nanocomposite morphology and elemental analyses were performed using FE-SEM and SEM machines, JEOL (JSM-7800F and JSM-IT300) (China), respectively. TEM images of the CB2 composite were obtained with a high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM, FEI Tecnai G220) (Netherlands). BET surface area analysis was achieved by means of a micromeritics Trista II surface area and porosity analyzer (U.S.A.) on samples that were degassed at 160 °C for 8 h with a micromeritics VacPrep 061 degas system (U.S.A.). FTIR investigations were done on sample pellets with a PerkinElmer Frontier FTIR spectrometer (South Africa) using potassium iodide as reference.

4.3. Photocatalytic Measurements

The photocatalytic measurements were performed in triplicate with a batch reactor setup, and the source of light was a 60 W LED lamp with a wavelength cutoff of λ ≥ 420 nm. The samples were filtered with 0.45 μm syringe filters, and the decrease in concentration was determined with a PerkinElmer UV–vis spectrometer Lambda 650 from 250 to 500 nm and from 350 to 750 nm after standards were prepared to determine the wavelengths of maximum absorption (319 and 573 nm) of p-nitrophenol (PNP) and brilliant black dye (BB), respectively. Different amounts of the catalyst (10, 20, 30, and 40 mg) were added to 50 mL of the pollutant solution, and the reaction was stirred in the dark for 30 min to allow the catalyst and pollutant to attain adsorption–desorption equilibrium; samples were taken at denoted time intervals for analysis. The efficiency of the synthesized catalysts was evaluated by %efficiency = (1 – A/A0) × 100 from the initial (A0) and final absorbance (A). The adjustment of pH was done with sulfuric acid and sodium hydroxide. For stability tests, the used catalyst was collected through centrifugation, washed with water and ethanol, and dried at 80 °C for 6 h. The subsequent test was performed by weighing the catalyst and adjusting the initial volume of the pollutant to cater for the catalyst loss.

Acknowledgments

This work was financed by the University of South Africa Nanotechnology and Water Sustainability Research Unit. Other UNISA departments (Physics and Chemical Engineering) are acknowledged for analysis of materials.

The author declares no competing financial interest.

References

- Patra S. K.; Rahut S.; Basu J. K. Enhanced Z-scheme photocatalytic activity of a π-conjugated heterojunction: MIL-53(Fe)/Ag/g-C3N4. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 18598–18607. 10.1039/C8NJ04080J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qi H. P.; Wang H. L.; Zhao D. Y.; Jiang W. F. Preparation and photocatalytic activity of Ag-modified GO-TiO2 mesocrystals under visible light irradiation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 480, 105–114. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.02.194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan P.; Xu L.; Cheng X.; et al. Photoelectrochemical monitoring of phenol by metallic Bi self-doping BiOI composites with enhanced photoelectrochemical performance. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2017, 804, 64–71. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2017.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhoi Y. P.; Majhi D.; Das K.; Mishra B. G. Visible-Light-Assisted Photocatalytic Degradation of Phenolic Compounds Using Bi2S3/Bi2W2O9 Heterostructure Materials as Photocatalyst. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 3423–3431. 10.1002/slct.201900450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bera S.; Won D.-I.; Rawal S. B.; Kang H. J.; Lee W. I. Design of visible-light photocatalysts by coupling of inorganic semiconductors. Catal. Today 2019, 335, 3–19. 10.1016/j.cattod.2018.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tahir M. B.; Kiran H.; Iqbal T. The detoxification of heavy metals from aqueous environment using nano-photocatalysis approach: a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 10515–10528. 10.1007/s11356-019-04547-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalanoor B. S.; Seo H.; Kalanur S. S. Recent developments in photoelectrochemical water-splitting using WO3/BiVO4 heterojunction photoanode: A review. Mater Sci Energy Technol. 2018, 1, 49–62. 10.1016/j.mset.2018.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y.-C.; Huang X.-H.; Yu H.-Q.; Tang L.-H. Nitrogen-Doped TiO2 Photocatalyst Prepared by Mechanochemical Method : Doping Mechanisms and Visible Photoactivity of Pollutant Degradation. Int J Photoenergy. 2012, 2012, 1–10. 10.1155/2012/960726. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata K.; Fujishima A. TiO2 photocatalysis : Design and applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C. 2012, 13, 169–189. 10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2012.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grujić-Brojčin M.; Armaković S.; Tomić N.; et al. Surface modification of sol-gel synthesized TiO2 nanoparticles induced by La-doping. Mater. Charact. 2014, 88, 30–41. 10.1016/j.matchar.2013.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Wang X.; Zhao J.; et al. Efficient Visible Light-Driven: In situ Photocatalytic Destruction of Harmful Alga by Worm-Like N,P co-Doped TiO2 Expanded Graphite Carbon Layer (NPT-EGC) Floating Composites. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2017, 7, 2335–2346. 10.1039/C7CY00133A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X.; Wang Z.; Wang G.; et al. Highly dispersed TiO2 nanocrystals and WO3 nanorods on reduced graphene oxide: Z-scheme photocatalysis system for accelerated photocatalytic water disinfection. Appl Catal B Environ. 2017, 218, 163–173. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.06.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Zhang L.; Li X.; Kang S.-Z.; Mu J. Visible Light Photocatalytic Activity of Porphyrin Tin(IV) Sensitized TiO2 Nanoparticles for the Degradation of 4-Nitrophenol and Methyl Orange. J. Dispersion Sci. Technol. 2011, 32, 943–947. 10.1080/01932691.2010.488500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hailili R.; Wang Z.-Q.; Gong X.-Q.; Wang C. Octahedral-shaped perovskite CaCu3Ti4O12 with dual defects and coexposed {(001), (111)} facets for visible-light photocatalysis. Appl Catal B Environ. 2019, 254, 86–97. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.03.086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.; Tan G.; Zhang D.; et al. Defect-mediated Z-scheme BiO2-x/Bi2O2.75 photocatalyst for full spectrum solar-driven organic dyes degradation. Appl Catal B Environ. 2019, 254, 98–112. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.04.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z.; Pan J.; Wang B.; et al. The p-n-type Bi5O7I-modified porous C3N4 nano-heterojunction for enhanced visible light photocatalysis. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 747, 788–795. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.03.112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Q.; Xie X.; Liu Y.; et al. Constructing a new Z-scheme multi-heterojunction photocataslyts Ag-AgI/BiOI-Bi2O3 with enhanced photocatalytic activity. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 371, 304–315. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Zhu G.; Hojamberdiev M.; et al. Three-dimensional Ag2O/Bi5O7I p–n heterojunction photocatalyst harnessing UV – vis – NIR broad spectrum for photodegradation of organic pollutants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 42–54. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q.; Yao J.; Arif M.; Huang T.; Liu X.; Duan G.; Yang X. Facile fabrication and photocatalytic performance of WO3 nanoplates in situ decorated with Ag/β-Ag2WO4 nanoparticles. J Environ Chem Eng. 2018, 6, 1969–1978. 10.1016/j.jece.2018.02.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kar P.; Jain P.; Kumar V.; Gupta R. K. Interfacial engineering of Fe2O3@BOC heterojunction for efficient detoxification of toxic metal and dye under visible light illumination. J Environ Chem Eng. 2019, 7, 102843–102852. 10.1016/j.jece.2018.102843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai B.; Zhang A.; Zhang D.; et al. Effect of preparation method on the structure and photocatalytic performance of BiOI and Bi5O7I for Hg0 removal. Atmos Pollut Res. 2019, 10, 355–362. 10.1016/j.apr.2018.08.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zarezadeh S.; Habibi-yangjeh A.; Mousavi M.; Ghosh S. Synthesis of novel p-n-p BiOBr/ZnO/BiOI heterostructures and their efficient photocatalytic performances in removals of dye pollutants under visible light. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2020, 389, 112247. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2019.112247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu G.; Hojamberdiev M.; Zhang S.; Din S. T. U.; Yang W. Enhancing visible-light-induced photocatalytic activity of BiOI microspheres for NO removal by synchronous coupling with Bi metal and graphene. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 467-468, 968–978. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.10.246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H.; Wu J.; Tian F.; et al. In-situ crystallization for fabrication of BiOI/Bi4O5I2 heterojunction for enhanced visible-light photocatalytic performance. Mater. Lett. 2018, 232, 191–195. 10.1016/j.matlet.2018.08.119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.; Xu L.; Liu C.; Xie T. Preparation and photocatalytic activity of porous Bi5O7I nanosheets. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 319, 265–271. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.07.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.; Wu J.; Li Q.; et al. Fabrication of BiOIO3 with induced oxygen vacancies for efficient separation of the electron-hole pairs. Appl Catal B, Environ. 2017, 218, 80–90. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.06.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long M.; Hu P.; Wu H.; Chen Y.; Tan B.; Cai W. Understanding the composition and electronic structure dependent photocatalytic performance of bismuth oxyiodides. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 5592–5598. 10.1039/C4TA06134A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L.; Zhang G.; Liu M.; Wang Q.; Dong S.; Wang P. Application of nickel foam-supported Co3O4-Bi2O3 as a heterogeneous catalyst for BPA removal by peroxymonosulfate activation. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 647, 352–361. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L.; Zhang G.; Wang Q.; Sun Y.; Liu M.; Wang P. Facile synthesis of novel Co3O4 -Bi2O3 catalysts and their catalytic activity on bisphenol A by peroxymonosulfate activation. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 326, 1095–1104. 10.1016/j.cej.2017.05.168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bao S.; Yan N.; Shi X.; Li R.; Chen Q. High and stable catalytic activity of porous Ag/Co3O4 nanocomposites derived from MOFs for CO oxidation. Appl Catal A Gen. 2014, 487, 189–194. 10.1016/j.apcata.2014.09.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C.; Liu E.; Wan J.; Hu X.; Fan J. Co3O4 nanoparticles decorated Ag3PO4 tetrapods as an efficient visible-light-driven heterojunction photocatalyst. Appl Catal B Environ. 2016, 181, 707–715. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2015.08.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asif S. A.; Khan S.; Asiri A. M. Efficient solar photocatalyst based on cobalt oxide/iron oxide composite nanofibers for the detoxification of organic pollutants. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 910–908. 10.1186/1556-276X-9-510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S.; Wang R.; Yin J.; et al. Preparation and dye degradation performances of self-assembled MXene-Co3O4 nanocomposites synthesized via solvothermal approach. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 3946–3953. 10.1021/acsomega.9b00231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z.; Fan J.; Deng X.; Liu J. One-step synthesis of phosphorus-doped g-C3N4/Co3O4 quantum dots from vitamin B12 with enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity for metronidazole degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 360, 1517–1529. 10.1016/j.cej.2018.10.239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M.; Wang W.-K.; Rong Q.; Jiang J.; Zhang Y.-J.; Yu H.-Q. Porous ZnO-Coated Co3O4 Nanorod as a High-Energy-Density Supercapacitor Material. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 23163–23173. 10.1021/acsami.8b07082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Z.; Lan L.; Li Y.; et al. Co3O4/TiO2 Nanocomposite Formation Leads to Improvement in Ultraviolet-Visible-Infrared-Driven Thermocatalytic Activity Due to Photoactivation and Photocatalysis-Thermocatalysis Synergetic Effect. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 16503–16514. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b03602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whang H. S.; Lim J.; Choi M. S.; Lee J.; Lee H. Heterogeneous catalysts for catalytic CO2 conversion into value-added chemicals. BMC Chem Eng. 2019, 1, 1–19. 10.1186/s42480-019-0007-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Wang Z.; Kawi S. Sintering and Coke Resistant Core/Yolk Shell Catalyst for Hydrocarbon Reforming. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 202–224. 10.1002/cctc.201801266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mafa P. J.; Kuvarega A. T.; Mamba B. B.; Ntsendwana B. Photoelectrocatalytic degradation of sulfamethoxazole on g-C3N4 /BiOI/EG p-n heterojunction photoanode under visible light irradiation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 483, 506–520. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.03.281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malefane M. E.; Feleni U.; Mafa P. J.; Kuvarega A. T. Fabrication of direct Z-scheme Co3O4/BiOI for ibuprofen and trimethoprim degradation under visible light irradiation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 514, 145940. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.145940. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.; Xiao K.; Zhang T.; Dong F.; Zhang Y. Rational design on 3D hierarchical bismuth oxyiodides via in situ self-template phase transformation and phase-junction construction for optimizing photocatalysis against diverse contaminants. Appl Catal B Environ. 2017, 203, 879–888. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.10.082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tahir M. B.; Sagir M. Separation and Purification Technology Carbon nanodots and rare metals (RM=La, Gd, Er) doped tungsten oxide nanostructures for photocatalytic dyes degradation and hydrogen production. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 209, 94–102. 10.1016/j.seppur.2018.07.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X.; Xing C.; He G.; Zuo X.; Nan J.; Wang L. Solvothermal synthesis of novel hierarchical Bi4O5I2 nanoflakes with highly visible light photocatalytic performance for the degradation of 4-tert-butylphenol. Appl Catal B Environ. 2014, 148-149, 154–163. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2013.10.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X.; Xu P.; Gong H.; Yin G. Synthesis and Characterization of WO3/Graphene Nanocomposites for Enhanced Ehotocatalytic Activities by One-Step In-Situ Hydrothermal Reaction. Materials 2018, 11, 147–155. 10.3390/ma11010147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou J.; Li X.; Zhang H.; et al. Synthesis of Silver/Silver Chloride/Exfoliated Graphite Nano-Photocatalyst and its Enhanced Visible Light Photocatalytic Mechanism for Degradation of Organic Pollutants. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2018, 59, 99–107. 10.1016/j.jiec.2017.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan K.; Avnir D.; Modestov A.; Lev O. Sol-Gel Derived Ormosil-Exfoliated Graphite-TiO2 Composite Floating Catalyst: Photodeposition of Copper. Chem. Mater. 1997, 9, 2533–2540. 10.1021/cm960637a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Labib S. Preparation, characterization and photocatalytic properties of doped and undoped Bi2O3. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2017, 21, 664–672. 10.1016/j.jscs.2015.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim S.; Pal T.; Ghosh S. The sonochemical functionalization of MoS2 by zinc phthalocyanine and its visible light-induced photocatalytic activity. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 10118–10125. 10.1039/C8NJ05976D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khairy M.; Zakaria W. Effect of metal-doping of TiO2 nanoparticles on their photocatalytic activities toward removal of organic dyes. Egypt J Pet. 2014, 23, 419–426. 10.1016/j.ejpe.2014.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. G.; Tan P.; Wang H.; Song M.; Pan J.; Kuang G. C. BODIPY modified g-C3N4 as a highly efficient photocatalyst for degradation of Rhodamine B under visible light irradiation. J. Solid State Chem. 2018, 267, 22–27. 10.1016/j.jssc.2018.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xue H.; Wang F.; Bai Q.; et al. Controllable synthesis of self-doped truncated bipyramidal Bi2O2CO3 with high visible light photocatalytic activity. Mater. Lett. 2018, 219, 148–151. 10.1016/j.matlet.2018.02.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malathi A.; Arunachalam P.; Grace A. N.; Madhavan J.; Al-mayouf A. M. A robust visible-light driven BiFeWO6/BiOI nanohybrid with efficient photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical performance. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 412, 85–95. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.03.199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushi D.; Sasaki A.; Hirabayashi H.; Kitano M. Effect of oxygen vacancy in tungsten oxide on the photocatalytic activity for decomposition of organic materials in the gas phase. Microelectron Reliab. 2017, 79, 1–4. 10.1016/j.microrel.2017.09.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bárdos E.; Kovács G.; Gyulavári T.; et al. Novel synthesis approaches for WO3-TiO2/MWCNT composite photocatalysts- problematic issues of photoactivity enhancement factors. Catal. Today 2018, 300, 28–38. 10.1016/j.cattod.2017.03.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi A.; Golsefidi M. A.; Beigi M. M.; Sadri N.; Abroudi M. Facile Fabrication of Co3O4 Nanostructures as an Effective Photocatalyst for Degradation and Removal of Organic Contaminants. J Nanostruct. 2018, 8, 89–96. 10.22052/JNS.2018.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ntsendwana B.; Peleyeju M. G.; Arotiba O. A. The application of exfoliated graphite electrode in the electrochemical degradation of p -nitrophenol in water. J Environ Sci Heal Part A. 2016, 51, 571–578. 10.1080/10934529.2016.1141623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary R.; Westwood A. Carbonaceous nanomaterials for the enhancement of TiO2 photocatalysis. cabon. 2011, 49, 741–772. 10.1016/j.carbon.2010.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty K.; Pal T.; Ghosh S. RGO-ZnTe: A Graphene Based Composite for Tetracycline Degradation and Their Synergistic Effect. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2018, 1, 3137–3144. 10.1021/acsanm.8b00295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty K.; Ghosh S.; Pal T. Reduced-Graphene-Oxide Zinc-Telluride Composite: Towards Large-Area Optoelectronic and Photocatalytic Applications. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 8637–8643. 10.1002/slct.201801519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X.; Zhang X.; Liu S.; Zhao J.; Xu Y. Sustained production of H2O2 in alkaline water solution using borate and phosphate-modified Au/TiO2 photocatalysts. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2018, 17, 1018–1022. 10.1039/C8PP00177D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W.; Zhang G.; Zheng T.; Wang P. Degradation of p -nitrophenol using CuO/Al2O3 as a Fenton-like catalyst under microwave irradiation. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 27043–27051. 10.1039/C4RA14516J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]