Abstract

The family is the principal source of socialization and protection against racism for many Blacks. Transmitting values, norms, morals, and beliefs (i.e., racial socialization) to successive generations is done to promote racial awareness and to prepare an individual to survive in racist environments. Further, developing a sense of security, resiliency, and cultural pride provides psychological protection against racial prejudice and discrimination. Protective socialization is even more critical when it becomes the difference between life and death at the hands of law enforcement—a fate faced by too many Black males as a result of racist policing practices, including the over-patrolling of Black communities. Because discriminatory surveillance and over-patrolling can incite a number of social, physical, and mental health issues, a holistic approach to understanding the interaction between Blacks and law enforcement is critical. This article reviews the Mundane Extreme Environmental Stress (MEES) model, racial socialization theory, and Family Stress Model in the development of a theoretical framework for understanding the patterns of interactions between Blacks and law enforcement, the immediate and long-term effects of unjustified shootings on Black families and communities, and the response of sociopolitical systems. The new theoretical framework will be used to inform the work of human service providers and practitioners by identifying targets for interventions to improve relations and trust between Black communities and law enforcement institutions.

Keywords: African American, bias, Black, crime, mental health, minority psychology, physical health, police, racial socialization, stress, surveillance

On March 4, 2015, the U.S. Department of Justice released its findings from an investigation of the Ferguson, Missouri, police department following the shooting of an unarmed Black teenager by a White police officer in Ferguson on August 9, 2014. The report revealed years of discriminatory conduct and violations of citizens’ constitutional rights by the police and municipal courts. According to the report, “the harms of Ferguson’s police and court practices are borne disproportionately by African Americans, and there is evidence that this is due in part to intentional discrimination on the basis of race” (DOJ, 2015, p. 4). Ferguson is now one of many cities publically fighting to eliminate discriminatory policing practices to repair trust between minority communities and police departments across the nation. Although the events in Ferguson have produced greater visibility of the issues related to the discriminatory policing of people of color, Blacks in America have long suffered from overt and covert forms of surveillance and over-patrolling. These forms of hyper-surveillance perpetuate strained and contentious relationships between law enforcement and the Black communities. Black males, as a result of hyper-surveillance and discrimination, suffer social, physical, and mental health challenges. Chronic environmental stressors have detrimental effects on the individual, family, and community. To gain a greater understanding of the myriad impacts that result from over-patrolling, this article explores the historical and contemporary issues related to Blacks’ law-enforcement interactions. An overview of hyper-surveillance in the Black community will analyze how the phenomenon contributes to the criminalization of an entire ethnic population. An overview of the Mundane Extreme Environmental Stress (MEES) model, racial socialization theory, and Family Stress Model are provided to inform a new theoretical framework. This innovative framework seeks to advance our understanding of the effects of interactions between Blacks and law enforcement on individuals, families, and communities. The proposed integrated theoretical framework aims to (1) explain the impact of negative police interactions and recognize the effects of the interactions extend past the individual, affecting families and communities, (2) describe how negative police interactions are stressors that cause psychological and physical challenges, and (3) describe the types of coping mechanisms that Black families employ as a result of negative police interactions. Providing greater insight regarding how police hyper-surveillance impacts the well-being of Black families and communities, the integrated theoretical framework has the potential to influence how human services professionals intervene to assist individuals and families within communities, and has implications for future research and practice.

A brief history of surveillance and the over-patrolling of Blacks

The relationship between Blacks and law enforcement has been contentious throughout America’s history. Dating back to slavery, law enforcement has kept Blacks subdued and subjugated by both formal and informal means of surveillance and criminalization (Jeffries, 2001; Murphy & Wood, 1984). Following Blacks’ emancipation from slavery in 1865, the role of the police in many states did not differ from the plantation overseer. Physical abuse as a means of oppression by police was not uncommon.

Blacks during the early- to mid-1900s were kept “in their place” through the enforcement of Jim Crow laws (Jeffries, 2001). Jim Crow used police and civilians to enforce coercive methods to maintain social segregation and racial hierarchies and promote White supremacy. For example, between 1920 and 1932 police were responsible for more than 50% of the deaths of Blacks, and White police were often present at their lynchings (Jeffries, 2001). Law enforcement deputized White citizens and asked that they monitor Blacks to enforce the Jim Crow laws (Packard, 2003).

The racist, terrorist, and White supremacist hate group the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) was founded in 1865 and served as an extension of law enforcement in many communities (Waldrep, 2008). The KKK beat, lynched, and tortured Black Americans from 1865 to the mid-1900s. At the height of its power, the KKK was responsible for the murder and assault of hundreds of Blacks, civil rights supporters, and those persons merely suspected of not supporting their cause (McVeigh & Cunningham, 2012). The KKK is still active, although widely regarded as a fringe group, with concentrations of members across the United States (Chalmers, 2015).

The contentious relationship between law enforcement and Blacks reached a crisis point at the height of the Civil Rights Era (1954–1968); federal policies to monitor the activity of social activists contributed to the hyper-surveillance of Black communities. J. Edgar Hoover, the first head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), targeted Black Power leaders and their followers. Operating under the guise of counterterrorism efforts (Greenberg, 2011), Hoover’s COunter INTelligence PROgram (COINTELPRO) was designed to monitor Black nationalists’ operations. FBI transcripts of COINTELPRO revealed that many Blacks, not only those in power movements, were targets of surveillance based on the criteria of race alone (Day & Whitehorn, 2001). FBI memos report that the purpose of COINTELPRO–Black Nationalist program was to use aggressive surveillance tactics to repress, dismantle, and discredit the Black Power movement’s Black leaders and to universally subjugate Black Americans (Day & Whitehorn, 2001). Hoover’s COINTELPRO anti–Black Nationalism program was a calculated effort to halt and reverse the economic, political, and social progress of millions of Black Americans (Cunningham, 2003; Day & Whitehorn, 2001).

Declared by President Richard Nixon in 1971, the “war on drugs” continued the use of federally supported law enforcement action against Black communities. More than a decade later, President Ronald Reagan passed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act in 1986. Direct and immediate effects of the act were mass arrest and incarceration of Black men (Nunn, 2002). The act also harshly criminalized the possession, sale, and use of controlled substances. Under both the Reagan and Bush administrations, the Anti-Drug Abuse Act cultivated federal and state laws reminiscent of Jim Crow because the laws strategically targeted low-income communities of color. Police officers had federal permission to “search and destroy” Black men (Jeffries, 2001; Nunn, 2002). The new federal policies sanctioned and encouraged police officers to over-patrol Black communities. Black men were disproportionately targeted for drug arrests, and the results of mass incarceration have had a devastating impact on Black communities (Goode, 2002).

Black men remain targets of draconian laws, whether they are guilty or not of committing any crime. “Stop and frisk” practices and arrests for nonviolent crimes, such as loitering, target Black men. Overwhelmingly, it is the myth of the deviant Black male that perpetuates the need for these laws. For example, U.S. Congressman Ron Paul stated, “I think we can safely assume that 95% of the Black males [in Washington, DC] are semi-criminal or entirely criminal” (Legum, 2011). This sentiment reflects the historical and contemporary beliefs about Blacks, in general, that fuel hyper-surveillance activities.

The prevalence of police hyper-surveillance and misconduct

National police misconduct data are often dependent upon voluntary state and local reporting. The data highlight significant differences in the treatment of Blacks while in police custody by law enforcement, as compared to persons of other racial and ethnic groups. The exact number of police assault and murder incidents involving Black victims is unknown, and this is due to the lack of any comprehensive federal program to track this information. At a local level, organizational culture, including professional integrity and attitudes about peer reporting, in addition to the circumstances of specific incidents, affects whether police will report police misconduct (Long, Cross, Shelley, Ivkovic, 2013). For example, in 2013 the FBI received 461 “justifiable homicide” reports deemed excusable by police officers nationwide. However, online crowdsourced campaigns revealed more than 300 additional police-involved fatalities (The Guardian, 2015). Significant discrepancies exist in the number of reported homicides by law enforcement to the government and larger population.

Missing and inaccurate information about police assault and homicide rates is common, and, due to this fact, independent organizations have begun tracking trends. Mapping Police Violence (MPV), a research collaborative, determined there were 1,149 known police killings (including 1,045 arrest-related deaths) in 2014 (Mapping Police Violence, 2015). MPV contends their database has accurately tracked the homicides of 88–96% of all Americans by culling information from three of the largest online crowdsourcing sites (Mapping Police Violence, 2015). A second organization using crowdsourcing information is named The Counted, developed by the Pulitzer Prize–winning media outlet The Guardian. The Counted claims that more than 500 people have been killed by law enforcement in the United States by mid-2015 (The Guardian, 2015).

Recent protests against police brutality and the murders of Blacks are the products of increased activism efforts, especially digital (online) activism. The protests bring attention to the frequency of homicides of unarmed Black men and women by police (Bonilla & Rosa, 2015) and highlight the lack of any comprehensive and systematic method of recording and analyzing law enforcement-caused injuries and deaths.

Black males are 21 times more likely to be fatally shot by police (Gabrielson, Jones, & Sagara, 2014). From 2010 to 2012, more Black males ages 15 to 19 were killed by police as compared to White males of the same age (31.17 versus 1.47 per million; Gabrielson et al., 2014). In cases where the cause of death by the police officer was “undetermined,” 77% of victims were Black (Gabrielson et al., 2014). In diverse cities such as Champaign, Illinois, where Blacks are a minority, discrimination by police still exists. For example, Blacks constituted 16% of the city’s population from 2007 to 2011 but accounted for 40% of all arrests (Cha-Jua, 2014). Similarly, in 2011 744 people were arrested for jaywalking, a nonviolent offense, in Champaign, and 88% of those arrested for jaywalking were Black (Cha-Jua, 2014). Oppressive, parasitic, and punitive social control generates revenue for the city; the jaywalking fine is $120 in Champaign (Cha-Jua, 2014). In New York City, where Blacks were 23% of the city’s population from 2008 to 2013, Blacks filed 55% of alleged police misconduct cases. During the same time period Whites, 34% of the city’s population, constituted only 9% of alleged police misconduct cases (CCRB, 2014).

Politicians and legislators decry police violence against all unarmed citizens, and many support increased law enforcement training and improving the problem of low reporting of police misconduct. U.S. Senators Barbara Boxer (D-California) and Cory Booker (D-New Jersey) proposed the Police Reporting of Information, Data and Evidence Act (PRIDE; S. 1476, 2015) in 2015. PRIDE would mandate that states report to the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) when law enforcement-involved injuries or deaths occur. Law enforcement would be required to record and report the age, race and ethnicity, number of victims, number of police, and armed/unarmed status of the victim to the DOJ.

Social effects of hyper-surveillance

The racial disparity in rates of arrest and police-involved homicide of Blacks negatively affects individuals and Black communities. The higher number of arrests and deaths by law enforcement are a direct consequence of the hyper-surveillance of Blacks in communities and more frequent rates of police interaction when compared to individuals of other ethnic groups. The Broken Windows theory, a framework for policing first explored by Kelling and Wilson (1982), assumes that “if a window is broken and is left unrepaired, all the rest of the windows will soon be broken” (Kelling & Wilson, 1982, p. 6). The analogy is meant to compare broken windows to minor criminal offenses, which, if left unrepaired or corrected, later contribute to the prevalence of more serious property and personal crimes. Broken Windows theory suggests, for example, that if police do not address minor offenses such as noise, open alcohol containers, and loitering, then more serious crimes such as burglary, assault, and murder are more likely to occur. However, researchers have disproven the Broken Windows theory in several longitudinal studies. In a study of 196 Chicago neighborhoods, Sampson and Raudenbush (1999) found that examples of community disorder (e.g., loitering, panhandling, prostitution, vandalism) were indirectly related to more serious property and personal crimes (e.g., burglary, robbery, and homicide). Community disorder, the analogous broken window, was not predictive of more serious crime.

Disorder does cause families to move out of neighborhoods and business investments to be directed to other areas. When families leave and community investments are diverted to other areas, these two actions destabilize neighborhoods and lead to an increase in the frequency and severity of crime (Sampson & Raudenbush, 1999). Similar to the study conducted in Chicago, Harcourt and Ludwig (2006) found policing practices in New York City that focused on reducing community disorder to reduce future crime were not an effective or efficient use of scarce government resources. New York City neighborhoods monitored in the study were those communities most affected by the 1980s crack epidemic, which caused an increase in the number of misdemeanor and felony crimes during the same period. Researchers argued that the nationwide drug epidemic was responsible for increases in serious crimes, not only unchecked minor crimes. Following the end of the nationwide epidemic, declines in serious crimes occurred, which further questioned the validity of the Broken Windows theory.

Over-policing practices are ineffective and inconsistent deterrents to crime. The social well-being of Black communities is greatly impacted by systematic mass arrest and incarceration. Blacks made up 12.5% of the total U.S. population in 2009 but accounted for 30% of all arrests (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010, 2012). Once arrested, Blacks are more likely to be charged and convicted of a felony offense, which results in jail or prison confinement. Access to public housing, food stamps, federal education grants and loans, employment, and the right to vote are placed in jeopardy or lost altogether (National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction, 2013). Penalties for incarceration extend to the families of the individuals who become involved in the criminal justice system.

More than 3 million Black adults are arrested each year (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). Blacks who go to jail and prison face longer sentences, stripping Black communities of human and financial capital—human capital that is responsible for combating poverty. When hundreds of individuals from a community are imprisoned, social networks that function as sources of emotional, financial, and social support are grossly impaired, or eliminated altogether. As a result socioeconomically disadvantaged families, in particular, face simultaneous losses of income, child care, and relationships (Roberts, 2004). Family members of incarcerated individuals must find money and allocate resources to pay for additional and unexpected costs, further straining families. Lawyer fees, court costs, collect calls, and funding commissary accounts place added financial burdens on the family of an incarcerated individual while trying to offset the loss of income in the household (Roberts, 2004). Hyper-surveillance with frequent arrest disrupts any community’s capacity to build wealth and develop human capital, and perpetuates generational poverty.

Disenfranchisement of Blacks in the criminal justice system has also had significant social and political effects. In her critically acclaimed book The New Jim Crow (2011)—a work that has been widely cited for bringing the issue of racial disparities in the criminal justice system to the forefront of current policy reform—Michelle Alexander writes that in the 2004 presidential election more than 600,000 individuals were excluded from the voting polls in Florida alone. If individuals in this single state could have voted, the 2004 presidential election may have ended very differently, sharply changing the course of history.

Similar to the rates of arrest among adults, repeat arrests of Black adolescents and young adults is largely due to police hyper-surveillance. The racialization of crime yields considerable societal costs: Black youth account for more than 10 times the costs imposed by White offenders on the public taxpayer (Cohen, Piquero, & Jennings, 2010). Black youth interact with police at a higher rate than Whites, and the costs of these interactions is high due to the frequency of arrests of Black youths.

In Philadelphia, Blacks from birth to age 26 on average had 18 law enforcement contacts before the age of 18; by age 24, these same young adults had nearly nine times the number of encounters with law enforcement and the criminal justice system as their White counterparts (Cohen et al., 2010). Criminal penalties result in higher court costs and room and board expenses and necessitate that local and state taxes are used to employ higher numbers of law enforcement and criminal justice employees (Cohen et al., 2010). In the Philadelphia study, Black youth with “low” police contact (i.e., low frequency of contacts over time) cost taxpayers $413,000 each, totaling $777 million for all participants by young adulthood (Cohen et al., 2010). Costs to the public were even more staggering for Black youth with “high” police contact: $1.6 million per Black youth before the age of 27 (Cohen et al., 2010).

Microlevel effects of hyper-surveillance

Blacks who experience interpersonal racism, including negative interactions with police officers, have generally lower levels of psychological and physical health (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999; Harrell, 2000; Landrine & Klonoff, 1996; Utsey & Payne, 2000; Utsey, 1999). There is a relationship between self-reported exposure to interpersonal racism and poor mental health (Brondolo, Ver Halen, Pencille, Beatty, & Contrada, 2009); anxiety disorders, clinical depression, personality disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) result from race-based discrimination (Carter, 2007). Anxiety and worry, in particular, are frequently occurring reactions to racism that prompt individuals to rehearse aggressive and defensive responses as a way to cope and adapt to these incidents (Carter, 2007; Harrell, Hall, & Taliaferro, 2003).

Environmental stressors change physiological functioning (Grzywacz & Fuqua, 2000) and interpersonal racism (Carter, 2007; Harrell et al., 2003) can increase the risk of developing diseases such as hypertension (HTN) and coronary artery disease (CAD; Brondolo et al., 2009). Measures of cardiovascular reactivity (CVR) may act as markers for processes that lead to the development of HTN and CAD (Brondolo et al., 2009). Racial identity is positively correlated with systolic blood pressure (SBP) reactivity to race and non-race-related stressors (Brondolo et al., 2009; Torres & Bowens, 2000); however, the effects of racial identity on psychological and physical health are complex, and this identity alone will not buffer the effects of racism on depressive symptoms or hypertension (Brondolo et al., 2009) for most Blacks.

Mesolevel effects of surveillance

Despite the cultural differences among different Black ethnic groups (e.g., African Americans, West Indians, European Blacks, Africans) within the Black diaspora structural racism has a cumulative effect in many Black communities, particularly in low-income neighborhoods where reduced employment opportunities, low wages, and inconsistent funding of public education exist. Neighborhood effects due to segregation (Sampson, Sharkey, & Raudenbush, 2008) impede navigation in the larger society, despite the fact that many Americans think causes of poverty lie mostly with the individual and their culture (Wilson, 2010).

Frequent discriminatory acts experienced by Blacks that are systemic over time, such as “stop and frisk” by police, can generate common psychological states and behavior patterns (Wilson, 2010). Parents living in segregated communities, for example, teach children a set of beliefs about what to expect and how to respond when police stop them on the street. This may lead to an interpretation of how to navigate the world and the belief that they are treated differently because they are Black; the beliefs become crystallized in cultural practices (Wilson, 2010).

The psychological effects of stress are persistent and cumulative (Carter, 2007). Black people fare poorly when faced with stress regardless of economic resources (Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2003). Blacks constitute 12.8% of individuals who meet criteria for any current depression, the highest rates for depression when compared to Whites, Latinos, and other groups (DHHS, 2010). Historical marginalization may account for psychological functioning in ways not well captured by individual-level measures (Norris, Friedman, & Watson, 2002).

Stress due to racism is a likely factor in higher rates of PTSD and reactions to stress; people of color experience PTSD after exposure to traumatic events at higher rates than the rest of the population (20–40% versus 5–10%; Carter, 2007). Being stopped by the police because of race produces traumatic reactions, and it is also a form of harassment. Racial harassment is a type or class of experiences characterized by hostile racism that involves feelings, thoughts, actions, strategies, behaviors, or policies that are intended to communicate the target’s subordinate or inferior status because of his or her membership in a nondominant racial group (Carter, 2007). This type of harassment perpetuates institutional racist practices and forces targets to “fall into line” as a condition of continued social participation; individuals may fear repercussions for reporting acts of racism (Carter, 2007).

Overview of an integrated theoretical framework

The economic, psychological, and social effects of discriminatory police practices call for closer examinations of the ways Blacks can avoid, adapt, and manage the deleterious effects of hyper-surveillance, an environmental stressor that increases the likelihood of interactions between Blacks and police, when compared to other racial and ethnic groups. The innovative framework presented in this article incorporates aspects of the Mundane Extreme Environmental Stress (MEES) model, racial socialization theory, and Family Stress Model to explain how racial socialization, a parenting practice that promotes racial and ethnic pride, helps Black youth develop effective coping mechanisms for dealing with hyper-surveillance. We assume that, through racial socialization, Blacks become aware of the historical and current treatment of their racial group by law enforcement and other groups, and adopt feelings of fear and mistrust toward law enforcement. However, because Blacks are also taught how to identify and prepare for racial bias, racial socialization may help to mitigate the harmful consequences of hyper-surveillance. The integrated theoretical framework (Figure 1) can offer contributions to the literature on reducing the effects of hyper-surveillance through adaptive parenting practices. It can also be used to explore relationships among hyper-surveillance and well-being outcomes of members of racial and ethnic minority groups, while considering mediating influences. Mediators include available resources, perceptions of law enforcement, degree of racial and ethnic identity, and preparation for racial bias and may act to support or change the direction of these relationships.

Figure 1.

An Integrated Theoretical Model of the Effects of Discriminatory Policing Practices on Black Families.

Environmental stressor: Hyper-surveillance of black communities by law enforcement

Peters and Massey’s (1983) Mundane Extreme Environmental Stress (MEES) model posits that Black families are encumbered by the constant threat and occurrences of intimidation, discrimination, and denial because of race. Factors of American life are particularly stressful to Black Americans due, in large part, to race. Higher than average unemployment and unequal educational opportunities, for example, causes Blacks to need to adapt to manifestations of racism (Peters & Massey, 1983) in everyday life. The MEES model includes two additional stress factors for Black families, as compared to a traditional stress and coping framework: extreme but mundane stress of omnipresent racism, and chronic and unpredictable racially caused stressful events throughout the life cycle (Peters & Massey, 1983).

Black families can attenuate or exacerbate frustration and tension experienced outside of the family. Attitudes, behavior patterns, and practices help these families to maintain family life and survive the American “system” of racism and racial discrimination (Peters & Massey, 1983). The MEES model employs an A-B-C-D-X-Y formula, where A (the event(s)), B (crisis-meeting resources; each family member’s ability and interaction effects), C (definition of the event by each individual), D (mundane extreme environmental stress), X (the product of the crisis), and Y (the action-no action response to the crisis) explain how experiences with real or perceived racism can facilitate the analysis of stress or crisis within Black families (Peters & Massey, 1983).

The MEES model can offer a unique framework for understanding the relationship between Blacks and police at both individual and family levels. While many studies of resisting racism among Blacks focus on individual coping responses and internal resources (Szymanski, 2012), experiences of real and perceived racial discrimination require that group-level interactions may serve as a better resource for coping with racism (Szymanski, 2012); validation by the group, counteracting devaluation, contextualizing versus internalizing oppression, developing resources to help with racialized stressors, and achieving ethnic group survival (Mattis et al., 2004) are components of pro-social, group-level coping strategies within the Black family.

A unique application of the MEES model in the integrated theoretical framework acknowledges that racial bias, or the beliefs in negative stereotypes about Blacks (Black males in particular), and acts of discriminatory policing practices by police officers act as contributing factors to the hyper-surveillance of Black communities. Individuals within Black families learn how to cope with racist police policies and practices based on cumulative event experiences, family members’ ability to manage the crisis individually and as a group, individual definitions of the event, perceived degree of racism experienced in the environment, the result(s) of the police activity, and the action of the person(s) involved in the event.

The influence of racial socialization on perceptions of law enforcement

Microlevel approaches for understanding race-specific interactions with law enforcement can shed light on the protective and adaptive practices Black families use to navigate an oppressive society. Through the process of racial socialization, Black children are taught the values and rules of society, and what to expect when rules are adhered to or violated. Thornton, Chatters, Taylor, and Allen (1990), states that individuals are taught different roles, statuses, and behaviors to learn how to “locate themselves” and others in the social structure. Thus, minority families use racial socialization to promote minority children’s self-esteem, ethnic identity, and cultural and racial pride and teach skills to cope with racial discrimination (Neblett et al., 2008). Black youth receive positive messages about their heritage and culture, history, important Black historical figures, and culturally relevant books, music, and holidays. Racial socialization is positively correlated with higher self-esteem (Stevenson, Reed, Bodison, & Bishop, 1997), academic achievement (Anglin & Wade, 2007; Smith, Walker, Fields, Brookins, & Seay, 1999), and fewer externalizing and internalizing problems (Bynum, Burton, & Best, 2007; Caughy, O’Campo, Randolph, & Nickerson, 2002).

The frequency and content of racial socialization may vary depending on parents’ racial socialization and experiences with racial discrimination. Therefore, Black youth have different beliefs about their culture and society (Hughes et al., 2006) and different coping styles when faced with racial discrimination. According to Burt and colleagues (2012), preparing children for explicit racial bias and discrimination necessitates that Black parents translate direct and indirect social experiences for their children to increase the capacity to appraise and cope with racism. Racial discrimination is consistently linked to poor psychological functioning in Blacks (Berger & Sarnyai, 2015; Broman, Mavaddat, & Hsu, 2000; Sellers & Shelton, 2003; Sellers, Copeland-Linder, Martin, & Lewis, 2006). However, preparation for future racial bias and fostering positive beliefs about one’s racial group can serve as a buffer against the harmful psychological effects of racial discrimination. Research on racial socialization suggests that Black children who report receiving early messages about other groups’ racial biases toward Blacks tend to have more positive psychological (e.g., Fischer & Shaw, 1999; Neblett, Banks, Cooper, & Smalls-Glover, 2013; Sellers et al., 2006) and physiological outcomes (Neblett & Carter, 2012) and fewer negative behavioral responses (Burt et al., 2012; Neblett, Terzian, Harriott, 2010).

Racial socialization theory offers a lens to examine how Blacks and police interact. To further explain the macrolevel structural processes that lead to the disproportionate number of Black Americans who experience racial profiling, police brutality, arrests, and sentencing, racial socialization theory posits that, at the microlevel (interpersonally), Blacks receive messages about police officers and the legal system. These messages shape their perceptions of and behaviors toward police. For example, Black youth at an early age learn that people believe that they are criminals and expect negative police treatment (Brunson & Miller, 2006; Carr, Napolitano, & Keating, 2007; Fine et al., 2003; Hinds, 2007). Different racial and ethnic groups vary on their perceptions of law enforcement (Huebner, Schafer, & Bynum, 2004). Blacks view police more negatively when compared to other groups (Reitzel & Piquero, 2006; Weitzer & Tuch, 2004). For example, after controlling for demographic, neighborhood, and policing variables, Weitzer and Tuch (2004) found that Blacks and Latinos were significantly more likely to believe police engage in misconduct. Lee and colleagues (2011) found that those who were more likely to identify with their ethnic or racial group had more positive perceptions of the role law enforcement plays in society. Complex views about law enforcement suggests that, on one hand Blacks realize police are necessary for controlling and reducing crime, and on the other hand, they are simultaneously distrustful of police because of previous misconduct and murder.

Racial socialization and prior experiences with police determine how individuals act toward police, either passively or aggressively. Even if fully cooperative, Black Americans are more likely to become the victims of police misconduct. Police officers’ fears, biases, or discriminatory practices are often directed at Blacks with or without any criminal history. Future research should consider how racial socialization impacts Blacks’ perceptions of and interactions with law enforcement, and additional studies should assess individuals’ levels of racial and ethnic pride, racial identity, and beliefs about police treatment toward members of particular ethnic or racial groups.

Existing resources and strategies for coping with the stress of police hyper-surveillance

American families in recent years have navigated turbulent economic, political, and social landscapes. Economically, stagnant or lower net income, high rates of unemployment, costs of living, and fewer social welfare programs pervade the economic landscape. Formerly middle-class families experience difficulty “making ends meet,” while low-income families have suffered the most, falling deeper into poverty (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010). Simultaneously, families contend with mental health challenges, domestic violence, poor physical health, and general family instability (Donnellan, Martin, Conger, & Conger, 2013). The economic and social effects of the recessions have had a profound effect on Black communities. These communities, in particular, face higher levels of socioeconomic disadvantage, which was the case prior to economic recessions (Pfeffer, Danziger, & Schoeni, 2013), and this disadvantage has worsened over time.

Black households, generally, earn lower annual incomes, have higher rates of unemployment, and are more likely to lose their homes in the housing crisis (Pfeffer et al., 2013). For each dollar of wealth of White families, Black families, in comparison, have only eight cents (Pfeffer et al., 2013). Without employment opportunities to generate income, Black male youths, in particular, are at significantly greater risk of engaging in criminal activity (Cox, 2010). The confluence of the lack of employment, criminal activity, and hyper-surveillance increases the risk of being arrested, placing immense stress on families (Cox, 2010; Roberts, 2004).

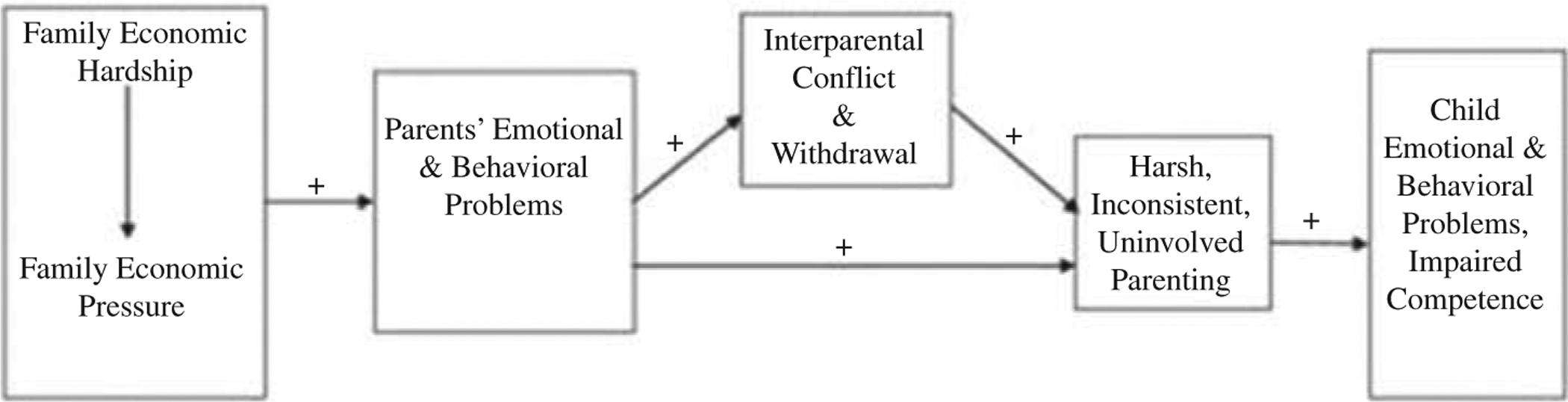

The Family Stress Model, developed by Conger and colleagues (2010), allows us to explore how families’ experiences of economic distress contribute to coping strategies among and within family members (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Family Stress Model (Conger et al., 2010).

The main assumption of the Family Stress Model is that economic hardships are the predominant influencing factor of children’s development through the lives of parents (Conger et al., 2010). As depicted in Figure 2, family economic hardships contribute to family economic pressure and define the “psychological meaning of the economic hardship for families” (Donnellan et al., 2013, p. 343). Parents’ economic pressures lead to emotional and behavioral problems, such as poor parenting styles, which may be the direct or indirect spillover of interparental conflict, which contributes to disrupted parent-child interactions. Children in poor parenting households, characterized by harsh punishments, inconsistent discipline, and lower levels of responsiveness, are at greater risk for the development of emotional and behavioral problems and compromised cognitive development (Conger et al., 2010; Donnellan et al., 2013).

Although the Family Stress Model has been primarily employed to examine the influence of socioeconomic disadvantage on family dynamics (Conger et al., 2010; Donnellan et al., 2013), the model can also be used to explore how other stressors, such as police hyper-surveillance, may influence family functioning and coping. Discriminatory policing practices impact family social pressure, or the beliefs, attitudes, and perceptions families hold about how one functions and interacts with the social environment. In turn, families seek to reduce perceived police suspicion to avoid criminal justice (Brayne, 2014) involvement. Overall, social pressures affect how parents socialize and parent their children. For example, after the shooting death of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in 2013, many Black parents increased protection of their children by instilling racial pride and educated their children on how to be observant, vigilant, and cautious of people and their environment. These parents taught their children how to adapt their behavior to increase the likelihood they could survive dangerous situations and as a way to cope with racial profiling (Thomas & Blackmon, 2015).

The Family Stress model contributes to a new integrative theoretical framework because it illustrates how resources, or the lack thereof, influence how police hyper-surveillance affects Blacks’ perceptions of the police. Family outcomes and racial socialization strategies of Black parents can mitigate the effects of surveillance and teach family members how to cope. Future research is needed to explore how the types of existing resources (e.g., legal, neighborhood, and social), combined with racial socialization strategies, may vary based on the degree of surveillance. For example, families who live in neighborhoods with a high police presence may incorporate more “strict” racial socialization strategies into their parenting practices due to a greater threat of police interaction and poorer perceptions of police. The frequency and depth of parents’ racial socialization messages to children may also depend on families’ history of interactions with the criminal justice system.

Discussion and conclusions

Patterns of interaction between Blacks and law enforcement are volatile. This is due to many factors: individual perceptions of police, discriminatory policing practices, and long-term structural inequalities. Blacks have had to contend with unequal treatment for generations. The intersection of lack of access to quality education, and the hallmarks of middle-class status such as regular employment and standard housing, leads to generational poverty. In low-income neighborhoods, residents are disproportionately targeted for illegal activity by law enforcement. Surveillance, search, seizure, and arrest, whether it is warranted or not, are frequent occurrences.

Hyper-surveillance directly impacts how Black individuals perceive law enforcement and influences the coping behaviors of Black families. The threat of arrest and actual incarceration have immediate and long-term effects on individuals and their families and perpetuates the breakdown of social cohesion and trust between law enforcement and the citizens they serve.

Resources and coping strategies (i.e., social support, racial socialization, degree of identity, social position, socioeconomic status, and physical health) impact how law enforcement is perceived by Blacks—either as a threat, ally, or combination of both. Resources also affect the ability of the family to maintain homeostasis; family outcomes are dependent on the family’s ability to interact with law enforcement and deal with the subsequent results of the interaction. Coping is complex and dynamic; the success of navigating stressful events depends on the adaptation of coping strategies, such as racial socialization, that will help alleviate psychological and physical distress, or avoidance of the stressor altogether.

Hyper-surveillance is an environmental stressor, and it has an effect on the psychological and physical health of Blacks. Race-based discriminatory practices lead to higher rates of anxiety, depression, and stress, in addition to higher rates of hypertension and heart disease in the population (Brondolo, Love, Pencille, Schoenthaler, & Ogedegbe, 2011; Brondolo et al., 2009; Williams & Mohammed, 2009). Aggressive policing creates feelings of “hopelessness” and being “dehumanized” (Brunson & Weitzer, 2009). Blacks who report more police contact tend to show higher levels of anxiety and PTSD symptoms associated with their experiences (Geller, Fagan, Tyler, & Link, 2014). Because costs outweigh benefits, hyper-surveillance is a public health concern for individuals and communities targeted by police.

Racial socialization is known to promote a range of positive outcomes and protect Blacks from the harmful effects of racial discrimination (Anglin & Wade, 2007; Burt et al., 2012; Caughy et al., 2002). However, less known about the nature of the adaptive parenting practice commonly used in Black families to cope with the consequences of hyper-surveillance. Using the integrated conceptual framework presented in this article, future research should examine what types and frequency of messages Blacks receive to avoid involuntary contact with police, such as the specific mannerisms they should have, styles of dress, and places and people to avoid. For example, parents may refrain their children from wearing hooded sweatshirts (“hoodies”), a type of clothing often deemed emblematic of criminal behavior and deviance (Bonilla & Rosa, 2015). Additionally, future studies should explore how these messages may vary by different racial and ethnic groups, gender, age, peer group, neighborhood context, and socioeconomic status (Hughes & Chen, 1999). In addition, with the growing use of digital activism and social media campaigns to display and protest instances of police misconduct, investigations should take into account other nonfamilial sources that shape how Blacks perceive or interact with law enforcement.

Regardless of income or neighborhood, Blacks are the frequent targets of surveillance and distrust by law enforcement. Implicit bias is evident when Blacks are assumed to be “guilty” of an offense, even when none has been committed. Erasing the pall of the supposition of guilt is rooted in eradicating individual bias and racism. This can be achieved only through increased familiarity and positive experiences with “the other,” continued earnest conversations about the roles that racial profiling and racialization of crime play in law enforcement, changes in policing practices that limit the undue burden on communities of color from the threats associated with police surveillance, and limiting the frequency of opportunistic and punitive sanctions for minor offenses, particularly among persons living in low-income communities. Social justice necessitates that each and every person deserves equal economic, political, and social rights and opportunities.

Limitations

The new integrated theoretical framework is a starting point for understanding how Black families cope with disproportionate rates of surveillance and interactions with law enforcement. Because the impact of hyper-surveillance on the psychological well-being and coping behaviors of Black families is understudied, there are some limitations to the framework. These limitations include uncertainty about which family outcomes are most likely to be affected, paucity of mediators to explain the relationship between increased police contact and negative family outcomes, and characteristics of the family (e.g., family composition, resources, socioeconomic status) and their environment (e.g., neighborhood crime, community support) that may affect the strength and direction of the relationship. Well-established theories that have not been applied to this topic were used to construct the framework. Thus, constructs from theories, existing in the gray or unpublished literature, could further develop the integrated framework. Despite these limitations, the integrated theoretical framework is a foundation for exploring the underlying mechanisms affecting how Blacks perceive and cope with the hyper-surveillance of their communities by law enforcement and illuminates how these phenomena impact Blacks at the individual, family, and community levels.

Implications for human service professionals

To improve relations and trust between Blacks and law enforcement at the interpersonal level, human service providers play an important role. At the microlevel, targets for intervention include increased training and education of police officers in the areas of bias and cultural sensitivity. By becoming more aware of the role that race, racialization of crime, and supposition of guilt play in hyper-surveillance, law enforcement professionals have an opportunity to change policy and practices that perpetuate these activities. Reducing instances of unjust surveillance in “hot spots,” and improved communication with individuals living in the communities they serve will help to attenuate the negative effects of the long-term patterns of unequal treatment between Blacks and law enforcement.

Additionally, human service professionals must continue to provide consultation and training in the identification of psychiatric disorders to law enforcement professionals. Approaching and detaining persons with serious mental illnesses is not consistent within departments, across precincts, and nationwide. Persons living with mental illness are more likely to be assaulted or killed than those not living with mental illness when approached by police. This is unnecessary; by employing trained mental health professionals to work with members of law enforcement, the number and frequency of encounters resulting in serious injury or death can be reduced.

Human service professionals should be aware of the role that environmental stress plays on the psychological and physical well-being of all people. However, culturally relevant practice includes knowing that Blacks may present psychological distress differently from the majority population; depression, as an example, may present as increased hostility, agitation, or anger as opposed to sadness, hypersomnia (excessive sleepiness), or changes in appetite (Wohl, Lesser, & Smith, 1997). Awareness of these signs allows human service professionals to screen for depression, provide appropriate referrals, or offer treatment.

On the macrolevel, working toward more equitable treatment of Blacks by law enforcement necessitates that human service professionals recommend policies and practices that serve all people fairly. Advocating for just treatment of persons who are under threat of detention or incarceration is necessary; when Black men are largely targeted for arrest, it becomes less of an individual issue and more of a systemic miscarriage of justice. By acknowledging the inequity of the criminal justice system, human service professionals must work to advocate changes to policies that determine who is incarcerated and for what length of time. To do this, collaboration with community leaders, advocacy groups, policymakers, lawyers, and law enforcement are necessary.

Proponents of improving relationships between Blacks and law enforcement argue that it is necessary to increase the number of Black police officers and change the racial and ethnic composition of law enforcement (Brunson & Gau, 2015). The challenge of this, however, is that Blacks with a criminal history may become ineligible to serve due to the nature of their convictions. Second, in areas where the predominance of law enforcement is Black—like Washington, DC—the rate of arrest and conviction is comparable, or greater, than in areas where the police force is majority non-Black. Thus, the racial or ethnic composition of law enforcement does not guarantee less surveillance, arrest, and detention.

Instead of only arguing that Blacks need more roles within law enforcement, human service professionals should advocate that a less adversarial and more collaborative relationship be achieved. This can be done successfully in the form of more citizen-led neighborhood watches, increasing the number of referrals to social services versus arrest, and offering opportunities for civic engagement through liaison building between community leaders and law enforcement personnel. Earnest evaluation of hyper-surveillance and mistreatment of Blacks by law enforcement over time shows the detrimental effects of these practices. Improving trust and relations between these groups requires the promotion of interventions to correct and repair damage caused by harassment and disenfranchisement over multiple generations.

References

- Alexander M (2011). The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York, NY: New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anglin DM, & Wade JC (2007). Racial socialization, racial identity, and Black students’ adjustment to college. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13(3), 207–215. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.3.207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M, & Sarnyai Z (2015). “More than skin deep”: Stress neurobiology and mental health consequences of racial discrimination. Stress, 18(1), 1–10. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2014.989204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla Y, & Rosa J (2015). #Ferguson: Digital protest, hashtag ethnography, and the racial politics of social media in the United States. American Ethnologist, 42(1), 4–17. doi: 10.1111/amet.12112 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brayne S (2014). Surveillance and system avoidance: Criminal justice contact and institutional attachment. American Sociological Review, 79(3), 367–391. doi: 10.1177/0003122414530398 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Broman CL, Mavaddat R, & Hsu SY (2000). The experience and consequences of perceived racial discrimination: A study of African Americans. Journal of Black Psychology, 26(2), 165–180. doi: 10.1177/0095798400026002003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, Love EE, Pencille M, Schoenthaler A, & Ogedegbe G (2011). Racism and hypertension: A review of the empirical evidence and implications for clinical practice. American Journal of Hypertension, 24(5), 518–529. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, ver Halen NB, Pencille M, Beatty D, & Contrada RJ (2009). Coping with racism: A selective review of the literature and a theoretical and methodological critique. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32(1), 64–88. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9193-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunson RK, & Gau JM (2015). Officer race versus macro-level context: A test of competing hypotheses about black citizens’ experiences with and perceptions of black police officers. Crime & Delinquency, 61(2), 213–242. doi: 10.1177/0011128711398027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brunson RK, & Miller J (2006). Young black men and urban policing in the United States. British Journal of Criminology, 46(4), 613–640. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azi093 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brunson RK, & Weitzer R (2009). Police relations with black and white youths in different urban neighborhoods. Urban Affairs Review, 44(8), 858–885. doi: 10.1177/1078087408326973 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burt CH, Simons RL, & Gibbons FX (2012). Racial discrimination, ethnic-racial socialization, and crime: A micro-sociological model of risk and resilience. American Sociological Review, 77(4), 648–677. doi: 10.1177/0003122412448648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bynum MS, Burton ET, & Best C (2007). Racism experiences and psychological functioning in African American college freshmen: Is racial socialization a buffer? Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13(1), 64–71. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr PJ, Napolitano L, & Keating J (2007). We never call the cops and here is why: A qualitative examination of legal cynicism in three Philadelphia neighborhoods. Criminology, 45(2), 445–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2007.00084.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RT (2007). Racism and psychological and emotional injury: Recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. Counseling Psychologist, 35(1), 13–105. doi: 10.1177/0011000006292033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caughy MOB, O’Campo PJ, Randolph SM, & Nickerson K (2002). The influence of racial socialization practices on the cognitive and behavioral competence of African American preschoolers. Child Development, 73(5), 1611–1625. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha-Jua SK (2014). “We believe it was murder:” Mobilizing black resistance to police brutality in Champaign, Illinois. Black Scholar, 44(1), 58–85. doi: 10.1080/00064246.2014.11641212 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers D (2015). Essay: The Ku Klux Klan. Retrieved from http://www.splcenter.org/get-informed/intelligence-files/ideology/ku-klux-klan/the-ku-klux-klan-0

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, & Williams DR (1999). Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist, 54(10), 805–816. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.54.10.805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MA, Piquero AR, & Jennings WG (2010). Monetary costs of gender and ethnicity disaggregated group-based offending. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 35(3), 159–172. doi: 10.1007/s12103-010-9071-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conger KJ, Conger RD, & Martin MJ (2010). Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 685–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox R (2010). Crime, incarceration, and employment in light of the great recession. Review of Black Political Economy, 37(3), 283–294. doi: 10.1007/s12114-010-9079-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham D (2003). The patterning of repression: FBI counterintelligence and the New Left. Social Forces, 82(1), 209–240. doi: 10.1353/sof.2003.0079 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Day S, & Whitehorn L (2001). Human rights in the United States: The unfinished story of political prisoners and COINTELPRO. New Political Science, 23(2), 285–297. doi: 10.1080/07393140120056009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). (2010). Current depression among adults—United States, 2006 and 2008. Centers for Disease Control of Prevention Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 59(38), 1229–1234. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5938a2.htm?s_cid=mm5938a2_w [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Justice Civil Rights Division (DOJ). (2015). Investigation of the Ferguson police department. Retrieved from http://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/opa/press-releases/attachments/2015/03/04/ferguson_police_department_report_1.pdf

- Donnellan MB, Martin MJ, Conger KJ, & Conger RD (2013). Economic distress and poverty in families In Fine MA & Fincham FD (Eds.), Handbook of family theories: A content based approach (pp. 338–355). New York, NY: Routledge (Taylor & Francis). [Google Scholar]

- Fine M, Freudenberg N, Payne Y, Perkins T, Smith K, & Wanzer K (2003). “Anything can happen with police around”: Urban youth evaluate strategies of surveillance in public places. Journal of Social Issues, 59(1), 141–158. doi: 10.1111/1540-4560.t01-1-00009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AR, & Shaw CM (1999). African Americans’ mental health and perceptions of racist discrimination: The moderating effects of racial socialization experiences and self-esteem. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 46(3), 395–407. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.46.3.395 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielson R, Jones RG, & Sagara E (2014). Deadly force, in black and white. Propublica; Retrieved from http://www.propublica.org/article/deadly-force-in-black-and-white [Google Scholar]

- Geller A, Fagan J, Tyler T, & Link BG (2014). Aggressive policing and the mental health of young urban men. American Journal of Public Health, 104(12), 2321–2327. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode E (2002). Drug arrests at the millennium. Society, 39(5), 41–45. doi: 10.1007/BF02717543 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg I (2011). The FBI and the making of the terrorist threat. Radical History Review, 2011(111), 35–50. doi: 10.1215/01636545-1268686 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz JG, & Fuqua J (2000). The social ecology of health: Leverage points and linkages. Behavioral Medicine, 26 (3), 101–115. doi: 10.1080/08964280009595758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harcourt BE, & Ludwig J (2006). Broken windows: New evidence from New York City and a five-city social experiment. University of Chicago Law Review, 73(1), 271–320. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell JP, Hall S, & Taliaferro J (2003). Physiological responses to racism and discrimination: An assessment of the evidence. American Journal of Public Health, 93(2), 243–248. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.2.243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP (2000). A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70(1), 42–57. doi: 10.1037/h0087722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds L (2007). Building police-youth relationships: The importance of procedural justice. Youth Justice, 7(3), 195–209. doi: 10.1177/1473225407082510 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner BM, Schafer JA, & Bynum TS (2004). African American and White perceptions of police services: Within- and between-group variation. Journal of Criminal Justice, 32(2), 123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2003.12.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, & Chen L (1999). The nature of parents’ race-related communications to children: A developmental perspective In Balter L & Tamis-LeMonda CS (Eds.), Child psychology: A handbook of contemporary issues (pp. 467–490). Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, & Spicer P (2006). Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42(5), 747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries JL (2001). Police brutality of black men and the destruction of the African-American community. Negro Educational Review, 52(4), 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Kelling GL, & Wilson JQ (1982). Broken windows: The police and neighborhood safety. The Atlantic, 29(38), Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1982/03/broken-windows/304465/ [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, & Klonoff EA (1996). The schedule of racist events: A measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology, 22(2), 144–168. doi: 10.1177/00957984960222002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JM, Steinberg L, Piquero AR, & Knight GP (2011). Identity-linked perceptions of the police among African American juvenile offenders: A developmental perspective. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(1), 23–37. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9553-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legum J (2011). Fact check: Ron Paul personally defended racist newsletters. Retrieved from http://thinkprogress.org/politics/2011/12/27/395391/fact-check-ron-paul-personally-defended-racist-newsletters/

- Long MA, Cross JE, Shelley TOC, & Ivković SK (2013). The normative order of reporting police misconduct examining the roles of offense seriousness, legitimacy, and fairness. Social Psychology Quarterly, 76(3), 242–267. doi: 10.1177/0190272513493094 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mattis JS, Beckham WP, Saunders BA, Williams JE, Myers V, Knight D, … Dixon C (2004). Who will volunteer? Religiosity, everyday racism, and social participation among African American men. Journal of Adult Development, 11(4), 261–272. [Google Scholar]

- Mapping police violence. (2015). 2015 Police violence report. Retrieved from http://mappingpoliceviolence.org

- McVeigh R, & Cunningham D (2012). Enduring consequences of right-wing extremism: Klan mobilization and homicides in southern counties. Social Forces, 90(3), 843–862. doi: 10.1093/sf/sor007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy W, & Wood B (1984). Slavery in colonial Georgia. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. [Google Scholar]

- National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction. (2013). Federal. Retrieved from http://www.abacollateralconsequences.org/search/?jurisdiction=1000

- Neblett EW Jr, Banks KH, Cooper SM, & Smalls-Glover C (2013). Racial identity mediates the association between ethnic-racial socialization and depressive symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 19 (2), 200–207. doi: 10.1037/a0032205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW Jr, & Carter SE (2012). The protective role of racial identity and Africentric worldview in the association between racial discrimination and blood pressure. Psychosomatic Medicine, 74(5), 509–516. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182583a50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, White RL, Ford KR, Philip CL, Nguyên HX, & Sellers RM (2008). Patterns of racial socialization and psychological adjustment: Can parental communications about race reduce the impact of racial discrimination? Journal of Research on Adolescence, 18(3), 477–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2008.00568.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW Jr, Terzian M, & Harriott V (2010). From racial discrimination to substance use: The buffering effects of racial socialization. Child Development Perspectives, 4(2), 131–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2010.00131.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York City Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB). (2014). 2013 report. Retrieved from www.nyc.gov/ccrb

- Norris FH, Friedman MJ, & Watson PJ (2002). 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part II. Summary and implications of the disaster mental health research. Psychiatry, 65(3), 240–260. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.240.20169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunn KB (2002). Race, crime and the pool of surplus criminality: Or why the war on drugs was a war on blacks. Journal of Gender, Race, and Justice, 6(2), 381–445. [Google Scholar]

- Packard JM (2003). American nightmare: The history of Jim Crow. New York, NY: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Peters MF, & Massey G (1983). Mundane extreme environmental stress in family stress theories: The case of Black families in White America. Social Stress and the Family, 6(1), 193–218. doi: 10.1300/J002v06n01_10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer FT, Danziger S, & Schoeni RF (2013). Wealth disparities before and after the Great Recession. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 650(1), 98–123. doi: 10.1177/0002716213497452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Police Reporting Information, Data, and Evidence Act (PRIDE) of 2015, S. 1476, 114th Cong. (2015). Retrieved from https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/114/s1476/text

- Reitzel J, & Piquero AR (2006). Does it exist? Studying citizens’ attitudes of racial profiling. Police Quarterly, 9(2), 161–183. doi: 10.1177/1098611104264743 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DE (2004). The social and moral cost of mass incarceration in African American communities. Stanford Law Review, 56(5), 1271–1305. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, & Raudenbush SW (1999). Systematic social observation of public spaces: A new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. American Journal of Sociology, 105(3), 603–651. doi: 10.1086/210356 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Sharkey P, & Raudenbush SW (2008). Durable effects of concentrated disadvantage on verbal ability among African-American children. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(3), 845–852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710189104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Copeland-Linder N, Martin PP, & Lewis RH (2006). Racial identity matters: The relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16(2), 187–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00128.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, & Shelton JN (2003). The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrimination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(5), 1079–1092. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, & Nelson AR (Eds.). (2003). Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EP, Walker K, Fields L, Brookins CC, & Seay RC (1999). Ethnic identity and its relationship to self-esteem, perceived efficacy and prosocial attitudes in early adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 22(6), 867–880. doi: 10.1006/jado.1999.0281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC, Reed J, Bodison P, & Bishop A (1997). Racism stress management racial socialization beliefs and the experience of depression and anger in African American youth. Youth & Society, 29(2), 197–222. doi: 10.1177/0044118X97029002003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DM (2012). Racist events and individual coping styles as predictors of African American activism. Journal of Black Psychology, 38(3), 342–367. doi: 10.1177/0095798411424744 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Guardian. (2015). The counted: People killed by police in the US. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2015/jun/01/the-counted-police-killings-us-database

- Thomas AJ, & Blackmon SM (2015). The influence of the Trayvon Martin shooting on racial socialization practices of African American parents. Journal of Black Psychology, 41(1), 75–89. doi: 10.1177/0095798414563610 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton MC, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, & Allen WR (1990). Sociodemographic and environmental correlates of racial socialization by Black parents. Child Development, 61(2), 401–409. doi: 10.2307/1131101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres A, & Bowens L (2000). Correlation between the internalization theme of Racial Identity Attitude Survey-B and systolic blood pressure. Ethnicity & Disease, 10(3), 375–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). American Community Survey (ACS) demographic and housing estimates. Retrieved from http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2012). Table 325. Arrests by race: 2009. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2012/tables/12s0325.pdf

- Utsey SO (1999). Development and validation of a short form of the index of race-related stress (IRRS)—brief version. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 32(3), 149–167. [Google Scholar]

- Utsey SO, & Payne Y (2000). Psychological impacts of racism in a clinical versus normal sample of African American men. Journal of African American Men, 5(3), 57–72. doi: 10.1007/s12111-000-1004-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrep C (2008). National policing, lynching, and constitutional change. Journal of Southern History, 74(3), 589–626. doi: 10.2307/27650230 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzer R, & Tuch SA (2004). Race and perceptions of police misconduct. Social Problems, 51(3), 305–325. doi: 10.1525/sp.2004.51.3.305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, & Mohammed SA (2009). Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32(1), 20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ (2010). Why both social structure and culture matter in a holistic analysis of inner-city poverty. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 629(1), 200–219. doi: 10.1177/0002716209357403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wohl M, Lesser I, & Smith M (1997). Clinical presentations of depression in African American and White outpatients. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health, 3(4), 279–284. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.3.4.279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]