Many patients with the pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome (PMIS) associated with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) present without respiratory symptoms.1, 2, 3 We present a pediatric patient with COVID-19 who experienced rapid neurological deterioration, diffuse cerebral edema, and ultimately brain death secondary to PMIS.

A seven-year-old boy with no significant past medical history presented with three days of fever up to 102.4°F, headaches, abdominal pain, and intractable emesis. He denied neck stiffness, photophobia, diarrhea, rhinorrhea, cough, and dyspnea. His parents had tested positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) four weeks prior with subsequent symptom resolution. A nasopharyngeal swab tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA by polymerase chain reaction. His serum inflammatory laboratory test results showed a normal procalcitonin, ferritin, and white blood cell count, but an elevated C-reactive protein of 13 mg/dL (0.00 to 0.50 mg/dL), erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 38 mm/hr (0 to 15 mm/hr), and D-dimer of 6.54 mg/L (<0.59 mg/L). Electrocardiography was normal. A computed tomographic (CT) venogram of his head was negative for any intracranial pathology.

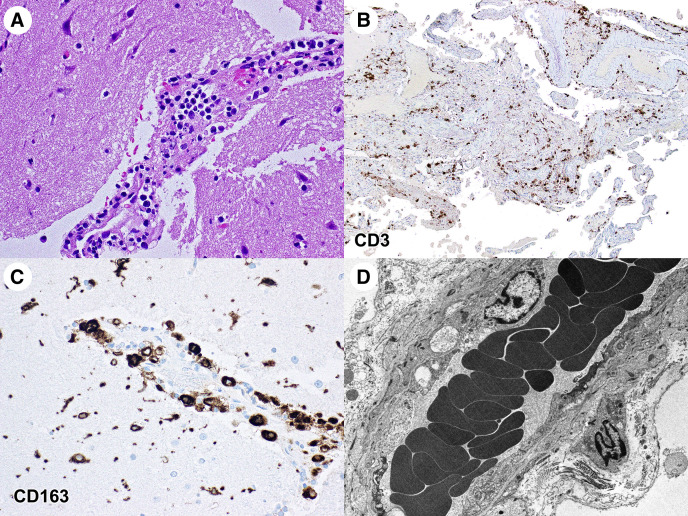

On his second day of admission, he developed severe neck pain and headache. He received one dose of hydroxychloroquine and soon after developed a facial rash, altered mental status, expressive aphasia, and pinpoint but reactive pupils. He then became unresponsive with left gaze deviation, a positive Brudzinski sign, and decreased neck range of motion. A non-contrast CT and CT angiography of the brain revealed no intracranial pathology. The patient received levetiracetam, lorazepam, vancomycin, and ceftriaxone. He was transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit and an electroencephalography (EEG) showed no evidence of paroxysmal activity. Over the following seven hours, the EEG developed intermittent polymorphic delta activity in the right temporal region, then loss of fast activity over the right hemisphere with increased delta activity in the left hemisphere, and then bilateral generalized voltage attenuation. He was found to be extensor posturing with fixed and dilated pupils and absent brainstem reflexes. He was intubated, and a CT scan of the head revealed new loss of gray-white differentiation with diffuse cerebral edema. Repeat laboratory results were consistent with severe inflammation, including procalcitonin 6.68 ng/mL (0.15 to 2.00 ng/mL), ferritin 1601.2 μg/L (18.0 to 370.0 μg/L), C-reactive protein 22 mg/dL, and D-dimer 17.65 mg/L. However, his erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 14 mm/hr and his white blood cell count was 6.5 k/mm3 (5.3 to 15.0 k/mm3). An intracranial pressure monitor was placed and revealed pressures greater than 76 mmHg, which remained refractory despite aggressive medical therapy. His neurological examination became consistent with brain death, and his family elected to withdraw life-sustaining treatment. Pathology slides showed diffuse cerebral edema in both the gray and white matter with perivascular mononuclear infiltrates, consistent with diffuse inflammation (Fig ). There were no microglial nodules or neuronophagia, which would have been suggestive of viral encephalitis. Cerebrospinal fluid and brain parenchyma did not have evidence of SARS-CoV-2 on polymerase chain reaction testing. There was no immunohistochemical, molecular, or electron microscopic evidence of SARS-CoV-2. No vasculitis was apparent.

FIGURE.

A hematoxylin and eosin pathology slide showing an infiltrate of mononuclear inflammatory cells around a cortical blood vessel (A). The surrounding cortex is edematous, and the neurons are hyperchromatic. Immunostains for CD 3, a T cell lymphocyte marker (B), and CD 163, a histiocyte marker (C), show a mixed inflammatory infiltrate consisting of T cells and histiocytes within both the meninges and cerebral cortex. An electron micrograph reveals vesiculo-vacuolar organelles within the cerebral endothelial cells with no evidence of virions (D). Immunostains for CD20, a B cell marker, showed only rare B cells.

The exact etiology of PMIS is unknown. Pediatric patients present with signs of inflammation in multiple organ systems causing features such as fatigue, neck pain, abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, kidney injury, rash, conjunctivitis, extremity edema, myocarditis, and cardiogenic shock. Laboratory biomarkers are consistent with inflammation, often similar to late-stage severe COVID-19 in adults with cytokine storms, hyperinflammation, and multiorgan damage.4 5 An overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines can cause vascular injury, cell death, and increased vascular permeability, which could account for the cerebral edema in our patient. It is unclear why PMIS presents in a delayed fashion in pediatric patients who otherwise did not manifest the early stages of COVID-19. Children with suspected PMIS and neurological symptoms should be closely monitored, and anti-inflammatory therapies should be considered.

Footnotes

Disclosures: This research did not receive specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Daskalakis D. 2020 Health Alert #13: Pediatric Multi-System Inflammatory Syndrome Potentially Associated with COVID-19. New York City Health Alert Network. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/han/alert/2020/covid-19-pediatric-multi-system-inflammatory-syndrome.pdf Available at:

- 2.Riphagen S., Gomez X., Gonzalez-Martinez C., Wilkinson N., Theocharis P. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395:1607–1608. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31094-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones V.G., Mills M., Suarez D. COVID-19 and Kawasaki disease: novel virus and novel case. Hosp Pediatr. 2020;10:537–540. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2020-0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shulman S.T. Pediatric COVID-associated multi-system inflammatory syndrome (PMIS) J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2020;9:285–286. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piaa062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldstein L.R., Rose E.B., Horwitz S.M. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:334–346. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]